Abstract

Thermal boundary resistance (TBR) is a key property for the thermal management of high power micro- and opto-electronic devices and for the development of high efficiency thermal barrier coatings and thermoelectric materials. Prediction of TBR is important for guiding the discovery of interfaces with very low or very high TBR. In this study, we report the prediction of TBR by the machine learning method. We trained machine learning models using the collected experimental TBR data as training data and materials properties that might affect TBR as descriptors. We found that the machine learning models have much better predictive accuracy than the commonly used acoustic mismatch model and diffuse mismatch model. Among the trained models, the Gaussian process regression and the support vector regression models have better predictive accuracy. Also, by comparing the prediction results using different descriptor sets, we found that the film thickness is an important descriptor in the prediction of TBR. These results indicate that machine learning is an accurate and cost-effective method for the prediction of TBR.

Introduction

Tailoring the thermal resistance of materials is vital for the thermal management of high power micro- and opto-electronic devices and for the development of high efficiency thermal barrier coatings and thermoelectric materials1–3. The overall thermal resistance of a material system is composed of the thermal resistance of the constituent materials and the thermal boundary resistance (TBR) between those materials. Heat in dielectric materials and semiconductors is transported predominantly by phonons, which undergo scattering in materials by interacting with defects, other phonons, boundaries, isotope, etc4. These processes cause the thermal resistance of the constituent materials. When heat passes through an interface between two materials, a temperature discontinuity occurs at the interface. TBR is defined as the ratio of the temperature discontinuity at an interface to the heat flux flowing across that interface. Typically, the characteristic length scales of the nanostructured materials are from several to hundreds of nanometers. By comparison, the phonon mean free paths (MFPs) in crystalline materials can be micrometers long5. When the characteristic length scales of nanostructured materials are shorter than the phonon MFPs, phonon transport is ballistic instead of diffusive. Furthermore, the number of interfaces increases greatly with decreasing characteristic length scales in nanostructured materials, such as superlattices. Thus, TBR can dominate the thermal resistance of the constituent materials and become a major component of the overall thermal resistance in nanostructured materials1–3. TBR is attributed to the mismatch between the phonon spectra of the materials on both sides of the interface5; interfacial properties, such as interfacial roughness, interdiffusion, bonding strength, and interface chemistry, also have a considerable effect1–3. Finding interfaces with very low or very high TBR experimentally is a high cost and time-consuming approach. Therefore, in order to guide the discovery of such interfaces, a reliable method for the prediction of TBR is necessary.

Several methods have been used for predicting TBR. The most common methods are the acoustic mismatch model (AMM) and the diffuse mismatch model (DMM)6. In the AMM, phonons is treated as plane waves, and the materials in which the phonons propagate are treated as continua. The transmission probabilities of phonons are calculated from the acoustic impedances on each side of the interface. A crucial assumption made in the AMM is that no scattering occurs at the interface. The assumptions of wave nature of phonon transport and specular scattering at the interface make the AMM valid when predicting TBR at low temperatures and at ideal interfaces. By comparison, in the DMM, completely diffuse scattering at the interface is assumed: a scattered phonon has no memory of its modes (longitudinal or transverse) and where it came from. The transmission probabilities of phonons are determined by the mismatch of the phonon density of states (DOS) on each side of the interface. Another crucial assumption made in the DMM is that phonons are elastically scattered: the transmitted phonons have the same frequencies with the incident phonons. These assumptions make the DMM invalid for an interface where inelastic phonon scattering occurs. In recent years, the molecular dynamics (MD) simulation method has emerged as a method for predicting TBR7, 8. In MD simulations, no assumptions concerning the nature of phonon scattering are required; the only required input to an MD simulation is the description of the atomic interactions. However, MD simulations also have limitations. The specification of the atomic interactions is typically done using empirical interatomic potential functions, and the results of MD simulations are realistic only when the specified atomic interactions mimic the forces experienced by the ‘real’ atoms9. Specifying an adequate description of atomic interactions that is applicable to various systems is a challenging task. Furthermore, MD simulations are computationally expensive and time-consuming, especially for simulation cells containing a large number of atoms. Thus, it is imperative to develop an accurate and cost-effective method to guide the discovery of interfaces with very low or very high TBR. In this work, we demonstrate a machine learning method for predicting TBR with much better predictive accuracy than the commonly used AMM and DMM.

Methods

Machine learning is a subfield of computer science that allows computers to improve their performance through experience10. When using machine learning to make predictions, one should consider three key ingredients: training data, descriptors, and machine learning algorithms. In this work, the training data include a large amount of experimental TBR data collected from 62 published papers1–3, 11–69. The data consist of a total of 876 TBRs measured for 368 interfaces as a function of measurement temperature and other conditions. The 368 interfaces comprise 45 different materials. The descriptors are measurement temperature, film thickness, heat capacity, thermal conductivity, Debye temperature, melting point, density, speed of sound (longitudinal and transverse), elastic modulus, bulk modulus, thermal expansion coefficient, and unit cell volume; collectively, these form the set which we define as “all collected descriptors”. We chose these descriptors from two points of view. Firstly, the descriptors are the measurement conditions and the properties of the materials constituting the interfaces that might affect TBR. Secondly, the descriptors should be easily collected. Namely, the values of the descriptors are clearly given in the references. The data of the descriptors are collected from references including the Internet, published papers1–3, 11–69, and databases, such as Atom Work in the NIMS MatNavi database70 and the TPRC data series71. The descriptor data for all the materials and their origins are shown in the supplementary files. The machine learning algorithms used in this work and the model fitting process are briefly introduced in the following paragraphs.

Generalized linear regression (GLR)

Linear regression is a method describing a linear relationship between a response and one or more descriptors72. The simple linear regression model can be described as

| 1.1 |

GLR extends simple linear regression. Unlike the simple linear regression, whose response has a normal distribution, the GLR response could be normal, binomial, Poisson, or something else. In GLR, a link function f is applied to the linear description, so the GLR model becomes

| 1.2 |

In our TBR prediction analysis, we choose the logarithm as the link function, , and the response has a Poisson distribution.

Least-absolute shrinkage and selection operator regularization (LASSO-GLR)

LASSO regularization is a shrinkage method that imposes a penalty term to limit a model’s complexity73. It can identify important descriptors, select descriptors among redundant descriptors, and produce fewer coefficients in the model formula. Moreover, it can address descriptor multicollinearity. LASSO regularization in GLR is an extension of simple LASSO regularization. It is defined by

| 1.3 |

where the second term with coefficient λ is a penalty term to balance model accuracy and complexity, and Deviance is the deviance between the response and the model fit by β 0 and β coefficients. In this study, the response has a Poisson distribution, and the link function is logarithm. The model is first given with all collected descriptors. After training, the number of coefficients in model is reduced due to the LASSO screening.

Gaussian process regression (GPR)

The GPR model is a nonparametric probabilistic model74. The goal of the GPR is to find a probabilistic distribution of new output given the training data and new input data, . Given that a latent variable f(x i) is a Gaussian process, then the joint distribution of a finite number of latent variables is also a Gaussian process, defined normally by , where is the kernel (covariance) function. In GPR, for known prior distributions of f and y, the posterior distribution of f new can be computed. In our study, the kernel function k(x i, x i) is a radial basis functio which is

| 1.4 |

The predicted mean is given by

| 1.5 |

where σ 2 is the noise variance.

Support vector regression (SVR)

SVR is an effective method of machine learning for regression problems75. The aim of SVR is to find a function to map a non-linear input space into a high dimensional feature space, so linear regression can be applied in this space. In SVR, the ε-insensitive loss function is commonly used, and a penalty factor C is chosen to control the balance between the model complexity and training errors. Like GPR, a kernel function is used to transform the data. The SVR optimization problem can be solved by quadratic programing algorithms, and the function to predict new data can be made by

| 1.6 |

where α, α* are Lagrange multipliers, and K (kernel function) is a radial basis function, which in this study is

| 1.7 |

We next introduce the model fitting process. For the GLR model, we use all the data to fit the model. The β coefficients are calculated by the least squares approach. For the LASSO-GLR, the GPR and the SVR models, model fitting is performed by finding optimal parameters λ (LASSO-GLR), σ f and σ l (GPR), C, ε, and γ (SVR). In this study, 5- and 10-fold cross-validations are performed to find these parameters. Since the results of the two cross-validations show very slight difference (<1%), only the results of the 10-fold cross-validation are shown in this study. The overall data are randomly partitioned into ten folds. Model training is done with nine folds and validation is done with the remaining one. This process is repeated ten times with each fold used exactly once as the validation data. Furthermore, to investigate the effect of random partition on the predictive accuracy, we try four different random partitions to split data by assigning different seeds to random generator. The calculated predictive accuracies of the four partitions show slight differences (<1%). Therefore, we consider the model’s predictive accuracy difference caused by the random data choice is very small. In this study, the average predictive accuracies of the four random partitions are used.

In our study, the model fitting is performed with MATLAB statistical software76 under different initial settings based on the machine learning algorithm, training data and descriptor set.

Results and Discussion

We have trained four models to predict TBR, which correspond to the four machine learning algorithms described above. We first predict the TBR of all the interfaces using the AMM and DMM. The details of the AMM and DMM predictions are described in ref. 5. For the AMM and DMM, the TBR can be written as

| 21 |

where R is the TBR, c i, j is the phonon propagation velocity in side i for phonons with mode j (longitudinal or transverse); α i, j is the transmission probability of phonons from side i with mode j; θ is the angle between the wave vector of the incident phonon and the normal to the interface; and ω is the phonon frequency. is the density of phonons with energy on side i with mode j at temperature T. The Debye cutoff frequency is given by

| 22 |

where N atom/V is the atom number density of the crystal. For frequencies below

| 2.3 |

where k B is the Boltzmann constant.

In the AMM, i = 1 in Eqs (2.1), (2.2), and (2.3), and the transmission probabilities of phonons are calculated from the acoustic impedances.

| 2.4 |

where is the acoustic impedance on each side of the interface, which equals to the product of the mass density and the phonon velocity.

In the DMM, the transmission probability of phonons are calculated by

| 2.5 |

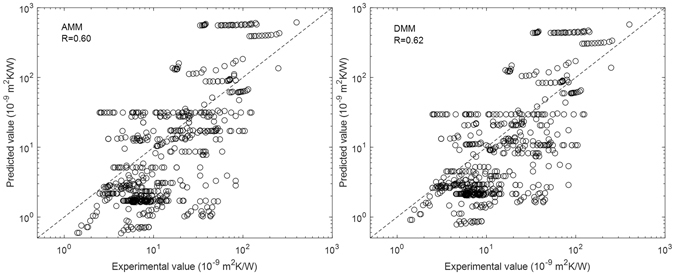

The descriptors used for the AMM and DMM predictions are temperature, density, speed of sound (longitudinal and transverse), and unit cell volume, which we define as “AMM and DMM descriptors”. Figure 1 shows the correlation between the experimental values and the values predicted by the AMM and DMM. Two parameters, the correlation coefficient (R) and root-mean-square error (RMSE), are used to evaluate the predictive accuracy of the models. For the AMM, R and RMSE are 0.60 and 121.3, respectively. For the DMM, R and RMSE are 0.62 and 91.4, respectively. Thus both the AMM and DMM have low predictive accuracy, although the DMM is slightly better.

Figure 1.

Correlation between the experimental values and the values predicted by the AMM and DMM.

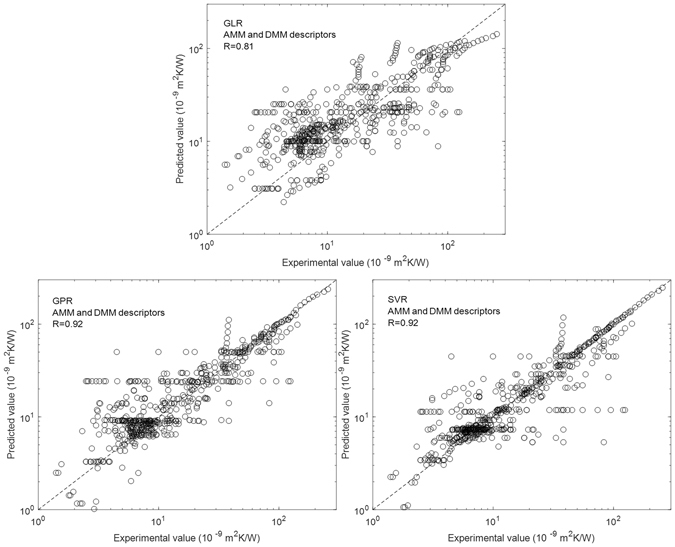

We next predict the TBR of all the interfaces using the machine learning models. It is known that the predictive accuracy of machine learning algorithms is strongly dependent on the selected descriptor sets77. In order to compare their predictions with those of the AMM and DMM, we have initially used the AMM and DMM descriptors. Figure 2 shows the correlation between the experimental and predicted values for the GLR, GPR, and SVR models. We next study the effects of descriptor set choice on the predictive accuracy of the machine learning models. First, we predict the TBR using all collected descriptors, because all collected measurement conditions and material properties may affect TBR. The values of R and RMSE for the GLR model and the average values of R and RMSE for the GPR and the SVM models are shown in Table 1. The results for the LASSO-GLR model are not given in Fig. 2 and Table 1, because the descriptors are different. As a result of model fitting, the LASSO-GLR model automatically selected 12 descriptors from the given 24, which are film thickness, film heat capacity, film melting point, film speed of sound (longitudinal), film thermal expansion, film unit cell volume, substrate thermal conductivity, substrate density, substrate speed of sound (longitudinal), substrate elastic modulus, substrate thermal expansion coefficient and substrate unit cell volume. We do not use this descriptor set in the following work because some important descriptors such as measurement temperature are missing, which is not reasonable from a physical point of view. The R and RMSE for the LASSO-GLR model are 0.89 and 15.8, respectively. For the GPR model, the average optimal σf and σl of the four random partitions are 176.22 and 5.56. For the SVR model, the average optimal C, ε, and γ are 987.15, 0.21 and 3.23. It is clear that all the machine learning models have much higher R and much lower RMSE than the AMM and DMM, indicating that all the machine learning models have a better predictive accuracy than the AMM and DMM. Among the machine learning models, the GPR and the SVR models have better performance than the GLR and the LASSO-GLR models.

Figure 2.

Correlation between the experimental values and the values predicted by the GLR, GPR, and SVR models using the AMM and DMM descriptors.

Table 1.

Comparison of R and RMSE predicted by different models using different sets of descriptors.

| AMM and DMM descriptors | All collected descriptors | “Reliable” descriptors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | RMSE | R | RMSE | R | RMSE | |

| AMM | 0.60 | 121.3 | N/A | N/A | ||

| DMM | 0.62 | 91.4 | N/A | N/A | ||

| GLR | 0.81 | 20.3 | 0.9 | 15.4 | 0.81 | 20.1 |

| GPR | 0.92 | 13.2 | 0.96 | 9.6 | 0.96 | 9.4 |

| SVR | 0.92 | 13.9 | 0.95 | 10.4 | 0.96 | 9.9 |

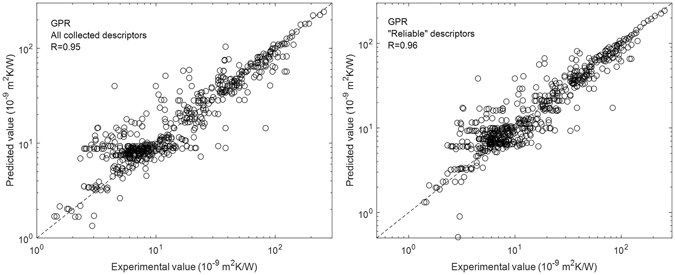

However, model fitting using all collected descriptors is difficult because it is difficult to collect some of the descriptors, such as thermal conductivity, Debye temperature, speed of sound (longitudinal and transverse), elastic modulus, and bulk modulus, for all the materials from references. Also, different references usually give very different values for these material properties. For example, the measured thermal conductivity of crystalline AlN ceramics ranges from 17 Wm−1K−1 to 285 Wm−1K−1 78. The measured thermal conductivity of nanoscale AlN thin films could be as low as 1.4 Wm−1K−1 79. Such large difference may significantly affect the predictive accuracy. Therefore, we predict TBR using only “reliable” descriptors: measurement temperature, film thickness, heat capacity, melting point, density, and unit cell volume. These material properties are called “reliable” because they are easily collected from references and different references usually give similar values. With the “reliable” descriptors, we fit the GLR, GPR and the SVR models. The average optimal σ f and σ l are 106.68 and 2.59 for the GPR model. The average optimal C, ε, and γ are 916.51, 0.88 and 1.71 for the SVR model. Like the use of all collected descriptors, it can also be found that the GPR and the SVR models have better predictive accuracies than the GLR model.

Figure 3 shows the correlation between the experimental values and the values predicted by GPR model using the “reliable” descriptors and all collected descriptors. It is clear that the predictions using the “reliable” descriptors and all collected descriptors have better predictive accuracy than using the AMM and DMM descriptors. This indicates that other descriptors, in addition to those that are used in the AMM and DMM, also affect TBR. If we compare the AMM and DMM descriptors and the “reliable” descriptors, we find that measurement temperature, density, and unit cell volume are in both descriptor sets. However, film thickness, heat capacity, and melting point are included in the “reliable” descriptors instead of speed of sound. This indicates film thickness, heat capacity, and melting point descriptors improved the predictive accuracy. In order to know which one plays the most important role, we added film thickness, heat capacity, or melting point to the AMM and DMM descriptor set and predicted TBR using the GPR model. The predictions had R values of 0.96, 0.92, and 0.92, respectively. This indicates that of these three descriptors, film thickness plays the most important role. To further test our suggestion, we predicted TBR using the GPR model and replacing film thickness in the “reliable” descriptor set with thermal conductivity, Debye temperature, elastic modulus, bulk modulus, or thermal expansion. All the predictions without film thickness as descriptor show an R value of ~0.92, which is similar to that for the AMM and DMM descriptors and lower than the value of R when film thickness is included. These results indicate that film thickness is an important descriptor in the prediction of TBR. The dependence of TBR on film thickness has been found in our previous study of MD simulations on Si/Ge interface80. In that work, we used two different cell sizes, corresponding to film thickness of 50 and 100 nm, respectively. As a result, the 100 nm film has a lower TBR than the 50 nm one. The thickness dependence of TBR has also been observed in our experimental study on Au/sapphire interface26, where the TBR increases obviously when the grain size of Au decreases. The effect of film or grain size on TBR can be explained as that the phonon modes in the films are thickness or grain size dependent. Therefore, change in film thickness will change the phonon transmission probability at the interface as well as the TBR.

Figure 3.

Correlation between the experimental values and the values predicted by the GPR model using the “reliable” descriptors and all collected descriptors.

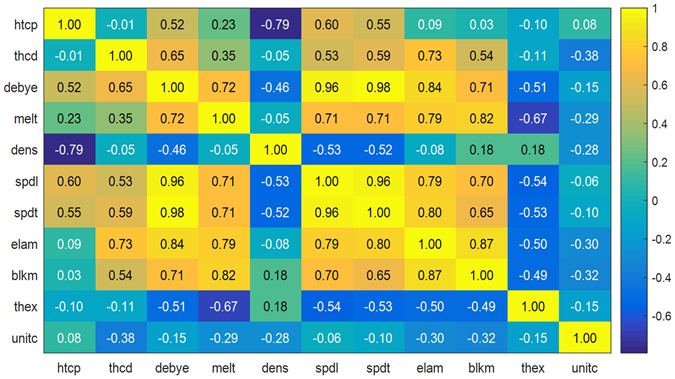

Furthermore, the predictions using the “reliable” descriptors and all collected descriptors have similar predictive accuracy. This indicates that the use of more material properties as descriptors does not necessarily improve predictive accuracy. It is known that many material properties, including heat capacity, thermal conductivity, Debye temperature, melting point, density, speed of sound, elastic modulus, bulk modulus, and thermal expansion coefficient, are physically-correlated. Using the collected materials property data, we drew a Pearson correlation coefficient map between different materials properties (see Fig. 4). For example, the correlation coefficients between Debye temperature and speed of sound are higher than 0.96, which is in good agreement with the physical-correlation of the two descriptors. We, therefore, attribute the similar predictive accuracy of the two descriptor sets to the physical-correlation of these descriptors; it is thus unnecessary to use all collected descriptors simultaneously in the prediction of TBR.

Figure 4.

Pearson correlation coefficient map between different materials properties. htcp (heat capacity), thcd (thermal conductivity), debye (Debye temperature), melt (melting point), dens (density), spdl (speed of sound longitudinal), spdt (speed of sound transverse), elam (elastic modulus), blkm (bulk modulus), thex (thermal expansion coefficient), and unitc (unit cell volume).

Conclusions

In summary, we have demonstrated a machine learning method for predicting TBR. We found that machine learning models have better predictive accuracy than the commonly used AMM and DMM. Among the trained models, the GPR and the SVR models have better predictive accuracy. Also, by comparing the prediction results using different descriptor sets, we found that film thickness is an important descriptor in the prediction of TBR. These results indicate that machine learning is a simple, accurate, and cost-effective method for the prediction of TBR. It can, therefore, be used to guide the discovery of interfaces with very low or very high TBR for the thermal management of high power micro- and opto-electronic devices and for the development of high efficiency thermal barrier coatings and thermoelectric materials.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the “Materials research by Information Integration” Initiative (MI2I) project of the Support Program for Starting Up Innovation Hub from Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST).

Author Contributions

Y.X. designed and supervised the study. T.Z. conducted the data collection. L.F. conducted the analysis. T.Z. and L.F. wrote the manuscript text.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-07150-7

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pernot G, et al. Precise control of thermal conductivity at the nanoscale through individual phonon-scattering barriers. Nat. Mater. 2010;9:491–495. doi: 10.1038/nmat2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Brien PJ, et al. Bonding-induced thermal conductance enhancement at inorganic heterointerfaces using nanomolecular monolayers. Nat. Mater. 2013;12:118–122. doi: 10.1038/nmat3465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Losego MD, Grady ME, Sottos NR, Cahill DG, Braun PV. Effects of chemical bonding on heat transport across interfaces. Nat. Mater. 2012;11:502–506. doi: 10.1038/nmat3303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holland MG. Phonon scattering in semiconductors from thermal conductivity studies. Phys. Rev. 1964;134:A471–A480. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.134.A471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Regner KT. Broadband phonon mean free path contributions to thermal conductivity measured using frequency domain thermoreflectance. Nat. Commun. 2013;1640:1–7. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swartz ET, Pohl RO. Thermal boundary resistance. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1989;65:605–668. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.61.605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landry ES, McGaughey AJH. Thermal boundary resistance predictions from molecular dynamics simulations and theoretical calculations. Phys. Rev. B. 2009;80:165304. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.80.165304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevens RJ, Zhigilei LV, Norris PM. Effects of temperature and disorder on thermal boundary conductance at solid–solid interfaces: Nonequilibrium molecular dynamics simulations. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer. 2007;50:3977–3989. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2007.01.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meller, J. Encyclopedia of Life Sciences, Nature Publishing Group (2001).

- 10.Langley P, Simon HA. Applications of machine learning and rule induction. Commun ACM. 1995;38:1. doi: 10.1145/219717.219768. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hopkins PE, Duda JC, Petz CW, Floro JA. Controlling thermal conductance through quantum dot roughening at interfaces. Phys. Rev. B. 2011;84:035438. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.84.035438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopkins PE, Phinney LM, Serrano JR, Beechem TE. Effects of surface roughness and oxide layer on the thermal boundary conductance at aluminum/silicon interfaces. Phys. Rev. B. 2010;82:085307. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.82.085307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costescu RM, Wall MA, Cahill DG. Thermal conductance of epitaxial interfaces. Phys. Rev. B. 2003;67:054302. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.67.054302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lyeo H-K, Cahill DG. Thermal conductance of interfaces between highly dissimilar materials. Phys. Rev. B. 2006;73:144301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.73.144301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakata M, et al. Thermal conductance of silicon interfaces directly bonded by room-temperature surface activation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015;106:081603. doi: 10.1063/1.4913675. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stevens RJ, Smith AN, Norris PM. Measurement of thermal boundary conductance of a series of metal-dielectric interfaces by the transient thermoreflectance technique. J. Heat Transfer. 2005;127(3):315–322. doi: 10.1115/1.1857944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koh YK, Bae M-H, Cahill DG, Pop E. Heat conduction across monolayer and few-layer graphenes. Nano Lett. 2010;10(11):4363–4368. doi: 10.1021/nl101790k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Z, Jang W, Bao W, Lau CN, Dames C. Thermal contact resistance between graphene and silicon dioxide. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009;95:161910. doi: 10.1063/1.3245315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hopkins PE, Norris PM. Thermal boundary conductance response to a change in Cr/Si interfacial properties. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006;89:131909. doi: 10.1063/1.2357585. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hopkins PE, et al. Effect of dislocation density on thermal boundary conductance across GaSb/GaAs interfaces. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011;98:161913. doi: 10.1063/1.3581041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collins KC, Chen S, Chen G. Effects of surface chemistry on thermal conductance at aluminum–diamond interfaces. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010;97:083102. doi: 10.1063/1.3480413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stoner RJ, Maris HJ. Kapitza conductance and heat flow between solids at temperatures from 50 to 300 K. Phys. Rev. B. 1993;48:16373. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.48.16373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang RY, Segalman RA, Majumdar A. Room temperature thermal conductance of alkanedithiol self-assembled monolayers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006;89:173113. doi: 10.1063/1.2358856. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ge Z, Cahill DG, Braun PV. Thermal Conductance of Hydrophilic and Hydrophobic Interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;96:186101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.186101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shenogina N, Godawat R, Keblinski P, Garde S. How wetting and adhesion affect thermal conductance of a range of hydrophobic to hydrophilic aqueous interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009;102:156101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.156101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu Y, Kato R, Goto M. Effect of microstructure on Au/sapphire interfacial thermal resistance. J. Appl. Phys. 2010;108:104317. doi: 10.1063/1.3514563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu Y, Wang H, Tanaka Y, Shimono M, Yamazaki M. Measurement of interfacial thermal resistance by periodic heating and a thermo-reflectance technique. Mater. Trans. 2007;48:148–150. doi: 10.2320/matertrans.48.148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhan T, et al. Thermal boundary resistance at Au/Ge/Ge and Au/Si/Ge interfaces. RSC Adv. 2015;5:49703–49707. doi: 10.1039/C5RA04412J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhan T, et al. Phonons with long mean free paths in a-Si and a-Ge. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014;104:071911. doi: 10.1063/1.4866799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu Y, Goto M, Kato R, Tanaka Y, Kagawa Y. Thermal conductivity of ZnO thin film produced by reactive sputtering. J. Appl. Phys. 2012;111:084320. doi: 10.1063/1.4706569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kato R, Xu Y, Goto M. Development of a frequency-domain method using completely optical techniques for measuring the interfacial thermal resistance between the metal film and the substrate. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2011;50:106602. doi: 10.7567/JJAP.50.106602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kato R, Hatta I. Thermal conductivity and interfacial thermal resistance: measurements of thermally oxidized SiO2 films on a silicon wafer using a thermo-reflectance technique. Int. J. Thermophys. 2008;29:2062–2071. doi: 10.1007/s10765-008-0536-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hopkins PE, et al. Manipulating thermal conductance at metal–graphene contacts via chemical functionalization. Nano Lett. 2012;12:590–595. doi: 10.1021/nl203060j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsieh WP, Lyons AS, Pop E, Keblinski P, Cahill DG. Pressure tuning of the thermal conductance of weak interfaces. Phys. Rev. B. 2011;84:184107. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.84.184107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cai W, et al. Thermal transport in suspended and supported monolayer graphene grown by chemical vapor deposition. Nano Lett. 2010;10:1645–1651. doi: 10.1021/nl9041966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmidt AJ, Collins KC, Minnich AJ, Chen G. Thermal conductance and phonon transmissivity of metal-graphite interfaces. J. Appl. Phys. 2010;107:104907. doi: 10.1063/1.3428464. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huxtable ST, et al. Interfacial heat flow in carbon nanotube suspensions. Nat. Mater. 2003;2:731–734. doi: 10.1038/nmat996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim E-K, Kwun S-I, Lee S-M, Seo H, Yoon J-G. Phonon and electron transport through Ge2Sb2Te5 films and interfaces bounded by metals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2000;76:3864. doi: 10.1063/1.126852. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hopkins PE, Norris PM, Stevens RJ. Influence of inelastic scattering at metal-dielectric interfaces. J. Heat Transfer. 2008;130(2):022401. doi: 10.1115/1.2787025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hopkins PE, Norris PM, Stevens RJ, Beechem TE, Graham S. Influence of interfacial mixing on thermal boundary conductance across a chromium/silicon interface. J. Heat Transfer. 2008;130(6):062402. doi: 10.1115/1.2897344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng H, Jaganandham K. Thermal conductivity and interface thermal conductance in composites of titanium with graphene platelet. J. Heat Transfer. 2014;136(6):061301. doi: 10.1115/1.4026488. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hu C, Kiene M, Ho PS. Thermal conductivity and interfacial thermal resistance of polymeric low k films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2001;79:4121. doi: 10.1063/1.1419239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minnich AJ, et al. Thermal conductivity spectroscopy technique to measure phonon mean free paths. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011;107:095901. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.095901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hopkins PE, et al. Reduction in thermal boundary conductance due to proton implantation in silicon and sapphire. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011;98:231901. doi: 10.1063/1.3592822. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Monachon C, Hojeij M, Weber L. Influence of sample processing parameters on thermal boundary conductance value in an Al/AlN system. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011;98:091905. doi: 10.1063/1.3560469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gorham CS, et al. Ion irradiation of the native oxide/silicon surface increases the thermal boundary conductance across aluminum/silicon interfaces. Phys. Rev. B. 2014;90:024301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.90.024301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gengler JJ, et al. Limited thermal conductance of metal-carbon interfaces. J. Appl. Phys. 2012;112:094904. doi: 10.1063/1.4764006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Freedman JP, Yu X, Davis RF, Gellman AJ, Malen JA. Thermal interface conductance across metal alloy–dielectric interfaces. Phys. Rev. B. 2016;93:035309. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.93.035309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jeong M, et al. Enhancement of thermal conductance at metal-dielectric interfaces using subnanometer metal adhesion layers. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2016;5:014009. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevApplied.5.014009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Donovan BF, et al. Thermal boundary conductance across metal-gallium nitride interfaces from 80 to 450 K. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014;105:203502. doi: 10.1063/1.4902233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cho J, et al. Phonon scattering in strained transition layers for GaN heteroepitaxy. Phys. Rev. B. 2014;89:115301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.89.115301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gaskins JT, et al. Thermal conductance across phosphonic acid molecules and interfaces: ballistic versus diffusive vibrational transport in molecular monolayers. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2015;119(36):20931. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b05462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hopkins PE, et al. Influence of anisotropy on thermal boundary conductance at solid interfaces. Phys. Rev. B. 2011;84:125408. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.84.125408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chow PK, et al. Gold-titania interface toughening and thermal conductance enhancement using an organophosphonate nanolayer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013;102:201605. doi: 10.1063/1.4807436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Norris PM, Smoyer JL, Duda JC, Hopkins PE. Prediction and measurement of thermal transport across interfaces between isotropic solids and graphitic materials. J. Heat Transfer. 2011;134(2):020910. doi: 10.1115/1.4004932. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koh YK, Cao Y, Cahill DG, Jena D. Heat-transport mechanisms in superlattices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009;19:610–615. doi: 10.1002/adfm.200800984. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Costescu RM, Cahill DG, Fabreguette FH, Sechrist ZA, George SM. Ultra-low thermal conductivity in W/Al2O3 nanolaminates. Science. 2004;303:989. doi: 10.1126/science.1093711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cheaito R, et al. Thermal boundary conductance accumulation and interfacial phonon transmission: Measurements and theory. Phys. Rev. B. 2015;91:035432. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.91.035432. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shukla NC, et al. Thermal conductivity and interface thermal conductance of amorphous and crystalline Zr47Cu31Al13Ni9 alloys with a Y2O3 coating. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009;94:081912. doi: 10.1063/1.3090487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ma Y. Hotspot size-dependent thermal boundary conductance in nondiffusive heat conduction. J. Heat Transfer. 2015;137(8):082401. doi: 10.1115/1.4030170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Losego MD, Moh L, Arpin KA, Cahill DG, Braun PV. Interfacial thermal conductance in spun-cast polymer films and polymer brushes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010;97:011908. doi: 10.1063/1.3458802. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Putnam SA, Cahill DG, Ash BJ, Schadler LS. High-precision thermal conductivity measurements as a probe of polymer/nanoparticle interfaces. J. Appl. Phys. 2003;94:6785. doi: 10.1063/1.1619202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jin Y, Shao C, Kieffer J, Pipe KP, Shtein M. Origins of thermal boundary conductance of interfaces involving organic semiconductors. J. Appl. Phys. 2012;112:093503. doi: 10.1063/1.4759286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee S-M, Cahill DG. Heat transport in thin dielectric films. J. Appl. Phys. 1997;81:2590. doi: 10.1063/1.363923. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Szwejkowski CJ, et al. Size effects in the thermal conductivity of gallium oxide (β-Ga2O3) films grown via open-atmosphere annealing of gallium nitride. J. Appl. Phys. 2015;117:084308. doi: 10.1063/1.4913601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Clark SPR, et al. Growth and thermal conductivity analysis of polycrystalline GaAs on chemical vapor deposition diamond for use in thermal management of high-power semiconductor lasers. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B. 2011;29:03C130. doi: 10.1116/1.3565054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Foley BM, et al. Modifying surface energy of graphene via plasma-based chemical functionalization to tune thermal and electrical transport at metal interfaces. Nano Lett. 2015;15(8):4876–4882. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b00381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Duda JC, et al. Influence of interfacial properties on thermal transport at gold:silicon contacts. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013;102:081902. doi: 10.1063/1.4793431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Duda JC, Hopkins PE. Systematically controlling Kapitza conductance via chemical etching. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012;100:111602. doi: 10.1063/1.3695058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Inorganic Material Database (AtomWork), NIMS Materials Database (MatNavi).

- 71.Touloukian, Y. S. Thermophysical properties of matter, the TPRC data series, Plenum Publishing Corporation (1970).

- 72.Dobson, A. J. & Barnett, A. An introduction to generalized linear models, Third Edition, Chapman and Hall/CRC (2008).

- 73.Tibshirani R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J. R. Stat. Soc. B. 1996;58:267–288. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rasmussen, C. E. & Williams, C. K. I. Gaussian processes for machine learning. MIT Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts (2006).

- 75.Lu WC, et al. Using support vector machine for materials design. Adv. Manuf. 2013;1:151–159. doi: 10.1007/s40436-013-0025-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.The Mathworks, Inc. Statistics and machine learning toolbox, MATLAB, R2016a.

- 77.Hansen K, et al. Machine learning predictions of molecular properties: Accurate many-body potentials and non-locality in chemical space. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015;6:2326. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b00831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Júnoir AF. Thermal conductivity of polycrystalline aluminum nitride (AlN) ceramics. Cerâmica. 2004;50:247–253. doi: 10.1590/S0366-69132004000300012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhao Y, et al. Pulsed photothermal reflectance measurement of the thermal conductivity of sputtered aluminum nitride thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 2004;96:4563–4568. doi: 10.1063/1.1785850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhan T, Minamoto S, Xu Y, Tanaka Y, Kagawa Y. Thermal boundary resistance at Si/Ge interfaces by molecular dynamics simulation. AIP Advances. 2015;5:047102. doi: 10.1063/1.4916974. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.