Abstract

Butyrate and niacin are produced by gut microbiota, however butyrate has received most attention for its effects on colonic health. The present study aimed at exploring the effect of niacin on experimental colitis as well as throwing some light on the ability of niacin to modulate angiogenesis which plays a crucial role of in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Rats were given niacin for 2 weeks. On day 8, colitis was induced by intrarectal administration of iodoacetamide. Rats were sacrificed on day 15 and colonic damage was assessed macroscopically and histologically. Colonic myeloperoxidase (MPO), tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-10, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), angiostatin and endostatin levels were determined. Niacin attenuated the severity of colitis as demonstrated by a decrease in weight loss, colonic wet weight and MPO activity. Iodoacetamide-induced rise in the colonic levels of TNF-α, VEGF, angiostatin and endostatin was reversed by niacin. Moreover, niacin normalized IL-10 level in colon. Mepenzolate bromide, a GPR109A receptor blocker, abolished the beneficial effects of niacin on body weight, colon wet weight as well as colonic levels of MPO and VEGF. Therefore, niacin was effective against iodoacetamide-induced colitis through ameliorating pathologic angiogenesis and inflammatory changes in a GPR109A-dependent manner.

Introduction

Commensal microbiota in the gut have profound effects on human health1, 2. They promote colonic health through production of the short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) by fermentation of dietary fiber. Among SCFAs, butyrate has received most attention for its effects on colonic health3. Previous studies proved that butyrate attenuated colonic inflammation and stimulated colonic repair4–6. Moreover, it improved the efficacy of mesalazine in experimental colitis models and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients7–9. The cell-surface receptors identified for butyrate are GPR43 and GPR109A which is also known as hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2 (HCA2 or HCAR2) or niacin receptor 1 (NIACR1). These receptors are G-protein-coupled and are expressed in colonic epithelium, adipose tissue and immune cells10, 11. Singh et al. revealed that GPR109A signaling imposed anti-inflammatory properties in colonic antigen-presenting cells, which in turn induced differentiation of Treg cells and interleukin (IL)-10 producing T cells. GPR109A was also essential for the expression of IL-18 in colonic epithelium. Niacr1 −/− mice showed enhanced susceptibility to colitis and colon cancer12.

Moreover, high intake of dietary fibre protected against dextran sulphate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis, an effect that was found to be a GPR109A dependent13.

The pharmacologic agonist for GPR109A is niacin (nicotinic acid) which is also produced by gut microbiota10, 11. Niacin, when taken in pharmacological doses, modifies lipid profile in circulation by acting as a GPR109A agonist in adipocytes. At these high doses, niacin is likely to reach the colon at concentrations high enough to exert GPR109A-dependent effects12. Niacin deficiency in humans results in pellagra, characterized by intestinal inflammation, diarrhea, dermatitis and dementia14. Singh and his colleagues demonstrated that niacin protected antibiotic-treated mice from weight loss, diarrhea, bleeding and colon cancer induced by administration of azoxymethane (AOM) and DSS12. However, the effect of niacin on experimental colitis model is no longer studied. The present study was, therefore, conducted to explore the effect of niacin on iodoacetamide-induced colitis and to throw some light on the ability of niacin to modulate angiogenesis which plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of IBD15–17. The effect of niacin on the levels of both angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors was investigated in this study. Moreover, the role of GPR109A in mediating such beneficial effects of niacin was examined.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Niacin was provided from Nice chemicals Pvt. Ltd. (Kochi, Kerala, India). Iodoacetamide and mepenzolate bromide (MPN) were obtained from Sigma Chemicals Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Rat TNF-α ELISA kit was purchased from R&D Systems (GmbH, Wiesbaden, Germany). Rat IL-10 ELISA kit was from Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Wuhan, Hubei, China). Rat angiostatin ELISA kit was from LifeSpan BioSciences, Inc. (Seattle, WA 98121, United States). Rat specific VEGF and endostatin ELISA kits were from Cusabio Biotech Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, Hubei, China).

Animals

Adult male Wistar rats, weighing 150–200 g each, were obtained from the Modern Veterinary Office for Laboratory Animals (Giza, Egypt) and were left to acclimatize for one week before subjecting them to experimentation. They were provided with a standard pellet diet and given water ad libitum. The animals were kept at a temperature of 22 ± 3 °C and a 12-hour light/dark cycle as well as a constant relative humidity throughout the experimental period. The investigation complies with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication no. 85–23, revised 2011) and was approved by the Ethical Committee for Animal Experimentation at Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University (Permit Number: PT 1835).

Iodoacetamide-induced colitis

The rats that had been fasted for 24 hours but had free access to drinking tap water were lightly anesthetized with ether. Colitis was then induced by instillation of 0.1 ml of 4% iodoacetamide dissolved in 1% methylcellulose into the colon via a catheter placed 8 cm proximal to the anus.

Experimental design

Rats were randomly assigned to four groups of eight animals each as follows: two control group; normal and colitis controls, and two niacin-treated groups (80 and 320 mg/kg). The drug/vehicle was administered orally once per day for 2 weeks. On day 8, colitis was induced in all groups except normal control which received 1% methylcellulose intrarectally. Animals were weighed just before iodoacetamide administration and just before autopsy.

Twenty-four hours after the last dose of treatment, the rats were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. The distal 10 cm of colon was excised, opened longitudinally, rinsed in ice-cold normal saline, cleaned of fat and mesentery, blotted on filter paper, and weighed. Colon wet weight (mg/g body weight) was calculated as a reflection of the severity of colitis. The colon segment was then cut longitudinally into two parts: one specimen was fixed in 10% formalin and preserved for histological examination, and the other was homogenized in ice-cold normal saline to obtain a 10% homogenate for assessment of the chosen biochemical parameters.

Determination of biochemical parameters

The colon homogenate was divided into two aliquots. One aliquot was mixed with an equal volume of 100 mmol/L phosphate buffer pH 6 containing 1% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide. The mixture was freeze-thawed, sonicated for 10 seconds and centrifuged at 10000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4 °C. The supernatant was used for spectrophotometric estimation of myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity18. The second aliquot was used for assaying tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-10, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), angiostatin and endostatin using specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits.

Histopathological assessment

Transverse sections, 4–6 μm in size, were prepared from paraffin-embedded colon segments from each animal. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and examined under a light microscope. They were graded individually by a pathologist blinded to the treatment regimen. Each section was assigned a damage score between 0 and 3 for each of five parameters, namely; mucosal necrosis, mucosal inflammatory cells infiltration, sub-mucosal inflammatory cells infiltration, fibrosis and sub-mucosal oedema. The scores for the five parameters measured for each rat were summed to obtain the “total histology score”, being maximally 15 (three as the maximum for the five parameters examined). The data were then represented using a box plot.

Role of GPR109A

To further characterize the role of the GPR109A receptor, animals were allocated into 6 groups, 5 rats each, and were treated as follows: normal and colitis controls (received the vehicle), two niacin-treated groups (80 and 320 mg/kg/day), and two niacin-treated groups (80 and 320 mg/kg/day) that were also given MPN, a GPR109A inhibitor, by intraperitoneal injection in a dose of 5 mg/kg/day19, 20. Same experimental design was repeated and the obtained colon samples were used for the biochemical assessment of both MPO and VEGF.

Statistical analysis

All data obtained, except for histological scores, were expressed as means ± SEM and analyzed using one-way-analysis of variance test (one-way ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s Kramer multiple comparison test. Histological scores were presented as median and analyzed using Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software, version 6.01 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). For all the statistical tests, the level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Body weight

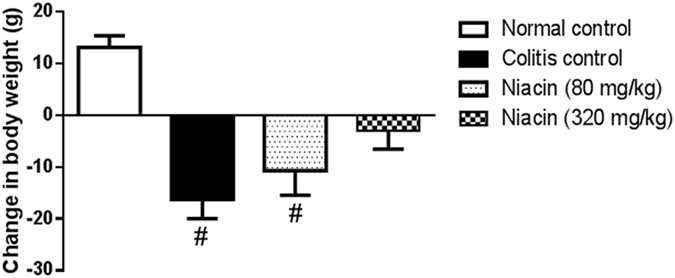

Iodoacetamide-induced colitis led to a decrease in body weight of rats (p < 0.0001). Pretreatment with niacin, especially, at the high dose level (320 mg/kg) tended to protect against such a decease in body weight (p = 0.1318) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of pretreatment with niacin on the increase in body weight of animals with iodoacetamide-induced colitis measured from the time of induction of colitis until sacrifice. Data are expressed as means ± SEM of 8 animals. # P ≤ 0.05 vs. normal control.

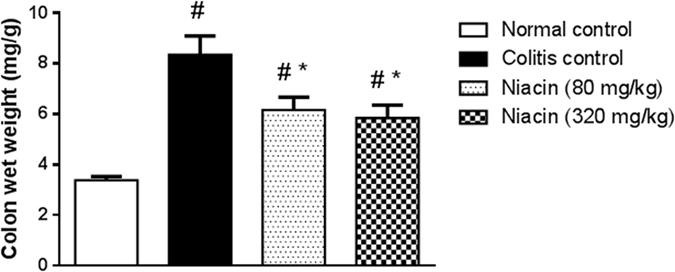

Colon wet weight

Intrarectal administration of iodoacetamide resulted in a 1.5-fold increase in colon wet weight as compared to the normal control group (3.39 ± 0.14 vs. 8.36 ± 0.73 mg/g). This obvious increase was prevented by pretreatment with niacin in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of niacin on colon wet weight in rats with iodoacetamide-induced colitis. Data are expressed as means ± SEM of 8 animals. # P ≤ 0.05 vs. normal control, *P ≤ 0.05 vs. colitis control.

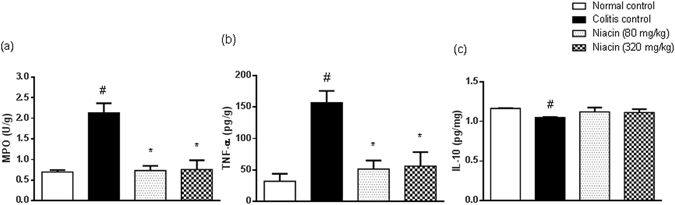

MPO, TNF-α and IL-10

Iodoacetamide caused spike increase in colonic MPO activity and TNF-α level. These derangements were largely prevented by pretreatment with niacin (Fig. 3a,b).

Figure 3.

Effect of niacin on inflammatory and anti-inflammatory parameters in colonic tissues of rats with iodoacetamide-induced colitis. (a) Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity, (b) tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α levels, (c) IL-10 levels. Data are expressed as means ± SEM of 8 animals. # P ≤ 0.05 vs. normal control, *P ≤ 0.05 vs. colitis control.

The colonic level of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 was, however, reduced in colitis rats, an effect that tended to be prevented by niacin (Fig. 3c).

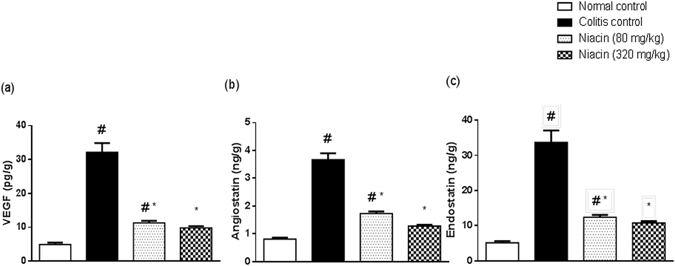

VEGF, angiostatin and endostatin

Induction of colitis was associated with a distinct increase in the colonic levels of both angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors as compared to normal control. There were 6.5-fold increases in the levels of VEGF and endostatin as well as 4.5-fold increases in angiostatin levels. Niacin was effective in protecting against such rise in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of niacin on proangiogenic and antiangiogenic factors in colonic tissues of rats with iodoacetamide-induced colitis. (a) Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), (b) angiostatin, (c) endostatin. Data are expressed as means ± SEM of 8 animals. # P ≤ 0.05 vs. normal control, *P ≤ 0.05 vs. colitis control.

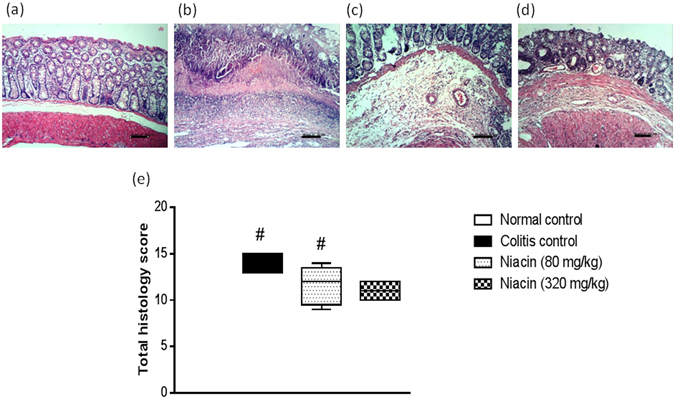

Histological examination

Representative histological images of H&E-stained colon sections from each group are shown in Fig. 5. In contrast to normal control animals (Fig. 5a), iodoacetamide-treated animals (Fig. 5b) showed marked necrosis of the epithelium and submucosal edema. These changes were associated with massive inflammatory cell infiltration in the lamina propria and submucosa. The infiltrated inflammatory cells included neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages. The total histology score was markedly increased in iodoacetamide-treated rats (Fig. 5e). Pretreatment with niacin tended to protect against the histological changes induced by iodoacetamide as evidenced by the lesser severity of the above parameters. The inflammatory infiltration in the mucosa and submucosa was only mild to moderate (Fig. 5c,d) and the total histology score was markedly decreased (Fig. 5e). The higher the dose of the drug, the greater was its protective effect.

Figure 5.

Effect of niacin on histopathological changes of rat colon in iodoacetamide model of colitis. (a) Normal control rat: normal histological structure of mucosa, (b) Colitis control rat showing necrosis of epithelium, inflammatory infiltrate in mucosa and submucosa as well as submucosal oedema, (c) Niacin (80 mg/kg) pretreated rat showing moderate inflammatory infiltrate in lamina propria and submucosa, (d) Rat pretreated with niacin (320 mg/kg) showing minimal changes. (H&E staining, ×100 original magnification). (e) Total histology score, data are expressed as box plots of the median of at least six animals. # P ≤ 0.05 vs. normal control.

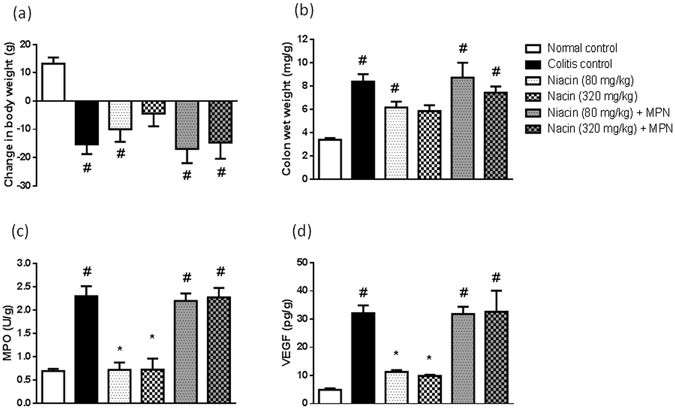

Role of GPR109A

In the presence of MPN, niacin failed to prevent iodoacetamide-induced loss in the body weight of animals. Moreover, MPN abolished the protective effect of niacin against iodoacetamide-induced rise in colon wet weight as well as the colonic levels of both MPO and VEGF (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Role of GPR109A in the protective effect of niacin against iodoacetamide-induced colitis in rats. (a) increase in body weight of animals measured from the time of induction of colitis until sacrifice, (b) colon wet weight, (c) Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity, (d) vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Data are expressed as means ± SEM of 5 animals. # P ≤ 0.05 vs. normal control, *P ≤ 0.05 vs. colitis control.

Discussion

The current study revealed that niacin protected against experimental colitis induced by iodoacetamide in rats by ameliorating colonic inflammation and pathologic angiogenesis. This was demonstrated in the prevention of iodoacetamide-induced weight loss especially with the high dose level of niacin. Consistently, niacin was previously shown to ameliorate (AOM + DSS)-induced weight loss12. Improvement was also demonstrated in both macroscopic and microscopic indices of damage, where niacin pretreated rats showed marked decrease in colon wet weight and total histology score as compared to control colitis rats. The protective effect of niacin was reflected on the biochemical measurement. Niacin obviously lessened the colonic MPO activity in GPR109A-dependent manner. MPO activity, a hallmark of colonic inflammation, was up-regulated in colons of rats with colitis indicating massive leukocyte infiltration into the colon as verified by the histological examination. This increase in leukocyte infiltration is a characteristic feature of IBD and experimental colitis contributing to disease initiation and subsequent tissue damage21, 22. Infiltrated leukocytes produce cytokines (such as TNF-α), angiogenic growth factors (such as VEGF), proteolytic enzymes (such as matrix metalloproteinases; MMP-2 and -9), and oxidants23–28. Thus, it is very likely that leukocyte infiltration facilitates the inflammatory and angiogenic changes observed in IBD. Niacin, by decreasing colonic MPO activities, was expected to possess beneficial effects against both inflammatory responses and pathologic angiogenesis.

The anti-inflammatory activity of niacin was previously recorded in several in vivo and in vitro studies in which niacin was shown to decrease TNF-α expression and production via down-regulating nuclear factor (NF)-κB activation signaling pathway. The inhibitory effect of niacin on TNF-α production was found to be mediated by GPR109A29–32. Although several studies addressed the anti-inflammatory effect of niacin, only one study, to our knowledge, investigated this effect on colonic inflammation12. This study, however, was done in experimental colon cancer model. In the current study, niacin was found, for the first time, to inhibit TNF-α production in iodoacetamide-induced colitis model. TNF-α plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of IBD, most likely because it disrupts the epithelial barrier, induces apoptosis of the villous epithelial cells, and stimulates the secretion of chemokines from the intestinal epithelial cells33. It also activates the adaptive immune system of the bowel by recruiting and activating neutrophils and macrophages34, 35. Moreover, inflammatory signaling via TNF-α up-regulates VEGF36, 37, a fundamental regulator of angiogenesis38, 39. TNF-α also increased the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 and its co-receptor neuropilin-1 in human vascular endothelial cells40. These findings support the existence of a direct link between inflammation and angiogenesis in IBD. Treating IBD patients with anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibody, infliximab, showed a rapid and sustained reduction in serum levels of VEGF41. Therefore, we expected that niacin, by reducing TNF-α and MPO, could affect angiogenesis that represents a critical component in IBD pathogenesis.

Clinical studies and animal models of experimental colitis showed increased microvascular density in the mucosal and submucosal tissue15, 16, 42 and up-regulation of VEGF43–48. Moreover, there was a strong causal association between increased VEGF expression and progression of experimental colitis. VEGF mRNA and protein expressions were increased as early as 0.5 hour after iodoacetamide enema and remained elevated in the active phase of colitis48. Consistently, the present findings revealed that colonic level of VEGF was markedly elevated in rats with idoacetamide-induced colitis. Up-regulated VEGF increases the expression of adhesion molecules, accelerates inflammatory cells adhesions49, 50, increases vascular permeability in colonic mucosa; thus, it facilitates inflammatory cell infiltration at the site of injury38, 42, 48. The infiltrated inflammatory cells up-regulated VEGF mRNA expression and increased VEGF protein levels. There was strong positive staining for VEGF in leukocytes in inflamed colonic tissue, whereas in normal tissue, VEGF was mostly localized to the endothelial cells48. Activated monocytes and/or macrophages alone are sufficient to induce angiogenesis51. This observed association between VEGF production and leukocytic infiltration in inflamed colonic tissues was consistent with the present findings, where colitis induction resulted in increased VEGF level and MPO activity indicating pathologic angiogenesis and increased neutrophilic infiltration. Neutralization of VEGF by anti-VEGF antibody was found to reduce leukocyte infiltration, inhibit angiogenesis and ameliorate colitis48. Consistently, pretreatment with niacin prevented the iodoacetamide-induced rise in VEGF level as well as MPO activity, an effect that was mediated through its anti-inflammatory properties. The ability of niacin to reduce VEGF was previously recorded when supplemented along with tamoxifen in breast cancer patients52. Butyrate was also found to repress angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo and reduce expression of proangiogenesis factors, including VEGF53–56. Moreover, Gambhir et al.57 revealed that the anti-inflammatory receptor GPR109A regulated the pathologic angiogenesis in diabetic retina. Up-regulation of GPR109A was associated with decreased expression of angiopoietin-like-4 (ANGPTL4), a gene that has received much attention as a critical regulator of pathologic angiogenesis and vascular permeability in retina. Additionally, absence of GPR109A (GPR109A−/−) was associated with upregulation of ANGPTL4. This association between GPR109A and regulation of pathologic angiogeniesis was also confirmed in the present study, where niacin’s protective effect against iodoacetamide-induced elevation in VEGF was abolished in the presence of MPN, an inhibitor of GPR109A. Niacin did not alter the colonic levels of VEGF in colitic rats treated with both niacin and MPN suggesting the essential role of GPR109A in mediating the niacin’s antiangiogenic properties in iodoacetamide model of colitis.

Angiogenesis is governed by a balance between pro- and antiangiogenic factors58. In the present study, we found that both angiogenic factor (VEGF) and antiangiogenic factors (endostatin and angiostatin) were significantly increased in the rat colon with experimental colitis. This was in agreement with the previous studies which showed concomitant upregulation of VEGF and anti-angiogenic factors endostatin and/or angiostatin in both rat and mouse models of colitis47, 59, 60. Moreover, Tolstanova et al. found a positive correlation between the levels of endostatin or VEGF and the sizes of colonic lesions in iodoacetamide-induced colitis60. The authors considered this concomitant increase in endostatin level to be a defensive response to the increased VEGF in colitis. Since niacin reduced the elevated VEGF, niacin was expected to protect against the rise in the anti-angiogenic factors in experimental colitis. In fact, the increased levels of VEGF, endostatin and angiostatin were reversed significantly by niacin in a dose-dependent manner. Previous study of Deng et al. demonstrated that mesalamine decreased endostatin and angiostatin as a result of reduced TNF-α expression that restore the balance between MMP2 and MMP9 in iodoacetamide-induced colitis model59. It is relevant to a clinical study that showed that therapy with infliximab increases MMP2 and decreases MMP9 in patients with Crohn’s disease61. Therefore, the ability of niacin pretreatment to reduce endostatin and angiostatin levels could be as a result of its anti-inflammatory activity and decrease in TNF-α as well as concomitantly to a reduction in VEGF levels.

Because GPR109A regulated the expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-1012, it is of interest to examine the effect of niacin on IL-10 production in colonic inflammation. IL-10 deficiency leads to spontaneous colitis62–64. Polymorphisms in the genes that encode IL-10 or IL-10 receptor are linked to increased incidence of IBD65, 66. Conflicting reports have been published on the effect of experimental colitis on IL-10 levels. In some studies a rise of IL-10 was observed67–69, while others showed no significant change in its levels70. The present findings revealed that the intra-colonic administration of iodoacetamide resulted in a decrease of colon levels of IL-10. This reduction in IL-10 levels was previously observed in several studies71–73. Pretreatment with niacin normalize IL-10 level in the colon of rats with iodoacetamide-induced colitis. This was consistent with the previous study of Singh et al. who showed that both butyrate and niacin induced the expression of IL-10 by splenic dendritic cells and macrophages12.

In conclusion, the present study revealed that niacin protected against colitis through its anti-inflammatory and anti-angiogenic effects in a GPR109A-dependent manner. These findings could have important implications for prevention as well as treatment of IBD and suggest that under conditions of reduced dietary fiber intake and/or decreased butyrate production in colon, pharmacological doses of niacin might be effective to protect colon against inflammation and pathogenic angiogenesis.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Prof. Dr. Kawkab Abd El Aziz Ahmed, Department of Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Cairo University, for her assistance in carrying out the histological examinations.

Author Contributions

H.A.S. conceived the conception, participated in the experimental part, and analyzed the results. W.W. conceived the design, carried out the experimental part and the acquisition of data, and interpreted the results. All authors participate in writing the draft and the revision of the final manuscript the revision of the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Hesham Aly Salem and Walaa Wadie contributed equally to this work.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Backhed F, Ley RE, Sonnenburg JL, Peterson DA, Gordon JI. Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science. 2005;307:1915–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1104816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Honda K, Littman DR. The microbiome in infectious disease and inflammation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012;30:759–795. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamer HM, et al. Review article: the role of butyrate on colonic function. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008;27:104–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butzner JD, Parmar R, Bell CJ, Dalal V. Butyrate enema therapy stimulates mucosal repair in experimental colitis in the rat. Gut. 1996;38:568–573. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.4.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Segain JP, et al. Butyrate inhibits inflammatory responses through NFκB inhibition: implications for Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2000;47:397–403. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.3.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vieiraa ELM, et al. Oral administration of sodium butyrate attenuates inflammation and mucosal lesion in experimental acute ulcerative colitis. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012;23:430–436. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vernia P, Cittadini M, Caprilli R, Torsoli A. Topical treatment of refractory distal ulcerative colitis with 5-ASA and sodium butyrate. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1995;40:305–307. doi: 10.1007/BF02065414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vernia P, et al. Combined oral sodium butyrate and mesalazine treatment compared to oral mesalazine alone in ulcerative colitis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2000;45:976–981. doi: 10.1023/A:1005537411244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song M, Xia B, Li J. Effects of topical treatment of sodium butyrate and 5-aminosalicylic acid on expression of trefoil factor 3, interleukin 1β, and nuclear factor κB in trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid induced colitis in rats. Postgrad. Med. J. 2006;82:130–135. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2005.037945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blad CC, Tang C, Offermanns S. G protein-coupled receptors for energy metabolites as new therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012;11:603–619. doi: 10.1038/nrd3777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganapathy V, Thangaraju M, Prasad PD, Martin PM, Singh N. Transporters and receptors for short-chain fatty acids as the molecular link between colonic bacteria and the host. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2013;13:869–874. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh N, et al. Activation of the receptor (Gpr109a) for niacin and the commensal metabolite butyrate suppresses colonic inflammation and carcinogenesis. Immunity. 2014;40:128–139. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macia L, et al. Metabolite-sensing receptors GPR43 and GPR109A facilitate dietary fibre-induced gut homeostasis through regulation of the inflammasome. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6734. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hegyi J, Schwartz RA, Hegyi V. Pellagra: dermatitis, dementia, and diarrhea. Int. J. Dermatol. 2004;43:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.01959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spalinger J, et al. Doppler US in patients with Crohn disease: vessel density in the diseased bowel reflects disease activity. Radiology. 2000;217:787–791. doi: 10.1148/radiology.217.3.r00dc19787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Danese S, et al. Angiogenesis as a novel component of inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis. Gastroeneterology. 2006;130:2060–2073. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koutroubakis IE, Tsiolakidou G, Karmiris K, Kouroumalis EA. Role of angiogenesis in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2006;12:515–523. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200606000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krawisz JE, Sharon P, Stenson WF. Quantitative assay for acute intestinal inflammation based on myeloperoxidase activity. Assessment of inflammation in rat and hamster models. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:1344–1350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh V, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis-driven targeted recalibration of macrophage lipid homeostasis promotes the foamy phenotype. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:669–681. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tran MT, et al. PGC1α-dependent NAD biosynthesis links oxidative metabolism to renal protection. Nature. 2016;531:528–532. doi: 10.1038/nature17184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toms C, Powrie F. Control of intestinal inflammation by regulatory T cells. Microbes Infect. 2001;3:929–935. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01454-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abreu MT. The pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease: translational implications for clinicians. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2002;4:481–489. doi: 10.1007/s11894-002-0024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sunderkötter C, Steinbrink K, Goebeler M, Bhardwaj R, Sorg C. Macrophages and angiogenesis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1994;55:410–422. doi: 10.1002/jlb.55.3.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polverini PJ. Role of the macrophage in angiogenesis-dependent diseases. EXS. 1997;79:11–28. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-9006-9_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shamamian P, et al. Activation of progelatinase A (MMP-2) by neutrophils elastase, cathepsin G, and proteinase-3: a role for inflammatory cells in tumor invasion and angiogenesis. J. Cell Physiol. 2001;189:197–206. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benelli R, Albini A, Noonan D. Neutrophils and angiogenesis: potential initiators of the angiogenic cascade. Chem. Immunol. Allergy. 2003;83:167–181. doi: 10.1159/000071560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benelli R, Lorusso G, Albini A, Noonan DM. Cytokines and chemokines as regulators of angiogenesis in health and disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2006;12:3101–3115. doi: 10.2174/138161206777947461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kusumanto YH, Dam WA, Hospers GA, Meijer C, Mulder NH. Platelets and granulocytes, in particular the neutrophils, form important compartments for circulating vascular endothelial growth factor. Angiogenesis. 2003;6:283–287. doi: 10.1023/B:AGEN.0000029415.62384.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwon WY, Suh GJ, Kim KS, Kwak YH. Niacin attenuates lung inflammation and improves survival during sepsis by downregulating the nuclear factor-kappaB pathway. Crit. Care Med. 2011;39:328–334. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181feeae4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Digby JE, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of nicotinic acid in human monocytes are mediated by GPR109A dependent mechanisms. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012;32:669–676. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.241836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zandi-Nejad K, et al. The role of HCA2 (GPR109A) in regulating macrophage function. FASEB J. 2013;27:4366–4374. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-223933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Si Y, et al. Niacin Inhibits Vascular Inflammation via Downregulating Nuclear Transcription Factor-κB Signaling Pathway. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:263786. doi: 10.1155/2014/263786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ardizzone S, Bianchi Porro G. Biologic therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Drugs. 2005;65:2253–2286. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Papadakis KA, Targan SR. Role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Annu. Rev. Med. 2000;51:289–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shih DQ, Targan SR. Insights into IBD pathogenesis. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2009;11:473–480. doi: 10.1007/s11894-009-0072-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Danese S. VEGF in inflammatory bowel disease: a master regulator of mucosal immune-driven angiogenesis. Dig. Liver Dis. 2008;40:680–683. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2008.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scaldaferri F, et al. VEGF-A links angiogenesis and inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:585–595.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carmeliet P, et al. Abnormal blood vessel development and lethality in embryos lacking a single VEGF allele. Nature. 1996;380:435–439. doi: 10.1038/380435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carmeliet P, Collen D. Molecular analysis of blood vessel formation and disease. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:H2091–H2104. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.5.H2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giraudo E, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha regulates expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 and of its co-receptor neuropilin-1 in human vascular endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:22128–22135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.22128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Di Sabatino A, Ciccocioppo R, Benazzato L, Sturniolo GC, Corazza GR. Infliximab downregulates basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor in Crohn’s disease patients. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004;19:1019–1024. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chidlow JH, Jr., et al. Differential angiogenic regulation of experimental colitis. Am. J. Pathol. 2006;169:2014–2030. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Griga T, Tromm A, Spranger J, May B. Increased serum level of vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1998;33:504–508. doi: 10.1080/00365529850172070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Griga T, Voigt E, Gretzer B, Brasch F, May B. Increased production of vascular endothelial growth factor by intestinal mucosa of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:920–923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Griga T, May B, Pfisterer O, Müller KM, Brasch F. Immunohistochemical localization of vascular endothelial growth factor in colonic mucosa of patients with IBD. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:116–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kanazawa S, et al. VEGF, basic-FGF, and TGF-beta in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: a novel mechanism of chronic intestinal inflammation. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2001;96:822–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sandor Z, Deng XM, Khomenko T, Tarnawski AS, Szabo S. Altered angiogenic balance in ulcerative colitis: a key to impaired healing. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;350:147–150. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tolstanova G, et al. Neutralizing Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) Antibody Reduces Severity of Experimental Ulcerative Colitis in Rats: Direct Evidence for the Pathogenic Role of VEGF. JPET. 2009;328:749–757. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.145128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barleon B, Sozzani S, Zhou D, Weich HA, Mantovani A. & Marme’, D. Migration of human monocytes in response to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is mediated via the VEGF receptor flt-1. Blood. 1996;87:3336–3343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goebel S, et al. VEGF-A stimulation of leukocyte adhesion to colonic microvascular endothelium: implications for inflammatory bowel disease. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G648–G654. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00466.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koch AE, Polverini PJ, Leibovich JL. Induction of neovascularization by activated human monocytes. J. Leukocyt. Biol. 1986;39:233–238. doi: 10.1002/jlb.39.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Premkumar VG, Yuvaraj S, Vijayasarathy K, Gangadaran SG, Sachdanandam P. Serum cytokine levels of interleukin-1beta, -6, -8, tumour necrosis factor-alpha and vascular endothelial growth factor in breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen and supplemented with co-enzyme Q(10), riboflavin and niacin. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007;100:387–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2007.00065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deroanne CF, et al. Histone deacetylases inhibitors as anti-angiogenic agents altering vascular endothelial growth factor signaling. Oncogene. 2002;21:427–436. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ogawa H, et al. Sodium butyrate inhibits angiogenesis of human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells through COX-2 inhibition. FEBS Letters. 2003;554:88–94. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)01110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bolden JE, Peart MJ, Johnstone RW. Anticancer activities of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006;5:769–784. doi: 10.1038/nrd2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liang D, Kong X, Sang N. Effects of histone deacetylase inhibitors on HIF-1. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2430–2435. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.21.3409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gambhir D, et al. The Anti-inflammatory Receptor GPR109A Regulates Angiopoeitin-like-4 (ANGPTL4) Expression in Retina: Potential New Link Between Regulation of Inflammatory and Angiogenic Signaling Mechanisms in Diabetic Retina. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012;53:5777. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pandya NM, Dhalla NS, Santani DD. Angiogenesis—a new target for future therapy. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2006;44:265–274. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deng X, et al. Mesalamine restores angiogenic balance in experimental ulcerative colitis by reducing expression of endostatin and angiostatin: novel molecular mechanism for therapeutic action of mesalamine. JPET. 2009;331:1071–1078. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.158022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tolstanova G, et al. Role of anti-angiogenic factor endostatin in the pathogenesis of experimental ulcerative colitis. Life Sci. 2011;88:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gao Q, et al. Infliximab treatment influences the serological expression of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and -9 in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2007;13:693–702. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huber S, et al. Th17 cells express interleukin-10 receptor and are controlled by Foxp3(−) and Foxp3+ regulatory CD4+ T cells in an interleukin-10-dependent manner. Immunity. 2011;34:554–565. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Izcue A, Coombes JL, Powrie F. Regulatory lymphocytes and intestinal inflammation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2009;27:313–338. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rubtsov YP, et al. Regulatory T cell-derived interleukin-10 limits inflammation at environmental interfaces. Immunity. 2008;28:546–558. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Franke A, et al. Sequence variants in IL10, ARPC2 and multiple other loci contribute to ulcerative colitis susceptibility. Nat. genet. 2008;40:1319–1323. doi: 10.1038/ng.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Glocker EO, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease and mutations affecting the interleukin-10 receptor. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:2033–2045. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tomoyose M, Mitsuyama K, Ishida H, Toyonaga A, Tanikawa K. Role of interleukin-10 in a murine model of dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1998;33:435–440. doi: 10.1080/00365529850171080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fiorucci S, et al. NCX-1015, a nitric-oxide derivative of prednisolone, enhances regulatory T cells in the lamina propria and protects against 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:15770–15775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232583599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Barada KA, et al. Up-regulation of nerve growth factor and interleukin-10 in inflamed and non-inflamed intestinal segments in rats with experimental colitis. Cytokine. 2007;37:236–245. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Togawa J, et al. Lactoferrin reduces colitis in rats via modulation of the immune system and correction of cytokine imbalance. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G187–G195. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00331.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu SP, Dong WG, Wu DF, Luo HS, Yu JP. Protective effect of angelica sinensis polysaccharide on experimental immunological colon injury in rats. World J. Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2786–2790. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i12.2786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Camacho-Barquero L, et al. Curcumin, a Curcuma longa constituent, acts on MAPK p38 pathway modulating COX-2 and iNOS expression in chronic experimental colitis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2007;7:333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fan H, et al. Oxymatrine improves TNBS-induced colitis in rats by inhibiting the expression of NF-kappaB p65. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technolog Med. Sci. 2008;28:415–420. doi: 10.1007/s11596-008-0409-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]