ABSTRACT

Iron and heme play very important roles in various metabolic functions in bacteria, and their intracellular homeostasis is maintained because high concentrations of free forms of these molecules greatly facilitate the Fenton reaction-mediated production of large amounts of reactive oxygen species that severely damage various biomolecules. The ferric uptake regulator (Fur) from Burkholderia multivorans ATCC 17616 is an iron-responsive global transcriptional regulator, and its fur deletant exhibits pleiotropic phenotypes. In this study, we found that the phenotypes of the fur deletant were suppressed by an additional mutation in hemP. The transcription of hemP was negatively regulated by Fur under iron-replete conditions and was constitutive in the fur deletant. Growth of a hemP deletant was severely impaired in a medium containing hemin as the sole iron source, demonstrating the important role of HemP in hemin utilization. HemP was required as a transcriptional activator that specifically binds the promoter-containing region upstream of a Fur-repressive hmuRSTUV operon, which encodes the proteins for hemin uptake. A hmuR deletant was still able to grow using hemin as the sole iron source, albeit at a rate clearly lower than that of the wild-type strain. These results strongly suggested (i) the involvement of HmuR in hemin uptake and (ii) the presence in ATCC 17616 of at least part of other unknown hemin uptake systems whose expression depends on the HemP function. Our in vitro analysis also indicated high-affinity binding of HemP to hemin, and such a property might modulate transcriptional activation of the hmu operon.

IMPORTANCE Although the hmuRSTUV genes for the utilization of hemin as a sole iron source have been identified in a few Burkholderia strains, the regulatory expression of these genes has remained unknown. Our analysis in this study using B. multivorans ATCC 17616 showed that its HemP protein is required for expression of the hmuRSTUV operon, and the role of HemP in betaproteobacterial species was elucidated for the first time, to our knowledge, in this study. The HemP protein was also found to have two additional properties that have not been reported for functional homologues in other species; one is that HemP is able to bind to the promoter-containing region of the hmu operon to directly activate its transcription, and the other is that HemP is also required for the expression of an unknown hemin uptake system.

KEYWORDS: Burkholderia, HemP, hemin, iron, regulator

INTRODUCTION

Although iron is an essential nutrient that is used as a cofactor for many enzymes in almost all bacteria, available iron is very limited because of its low solubility in eukaryotic hosts and natural aerobic environments (1–3). Therefore, bacteria usually have multiple systems for the acquisition and metabolism of external iron. One representative and well-studied system is siderophore-mediated sequestration of external ferric ion and its subsequent transport into the cytoplasm and reduction to ferrous ion (4–6). However, high concentrations of intracellular ferrous ion under aerobic conditions are toxic and, for example, induce the Fenton reaction, by which metabolically produced hydrogen peroxide (a toxic reactive oxygen species [ROS]) is converted to hydroxyl radical, another ROS with a greater degree of toxicity (Fe2+ + H2O2 → Fe3+ + HO− + OH·) (7). Hydroxyl radical then reacts with a toxic reactive nitrogen species (RNS) (e.g., nitric oxide [NO], which is spontaneously generated in cells and natural environments) to generate more toxic RNS (8). ROS and RNS also react with various biomolecules to impair their functions severely, and they significantly facilitate the release of iron from the biomolecules (9). To avoid the extremely undesirable circumstance of high concentrations of free intracellular iron, bacteria have sophisticated systems to maintain iron homeostasis. One such system is mediated by Fur (ferric uptake regulator) or its functional homologue (7, 10, 11). Under iron-replete conditions, the Fur-Fe2+ complex interacts with a specific sequence (Fur box), usually leading to the transcriptional repression of genes that are located downstream of the Fur box. Fur is a global transcriptional regulator and regulates, either directly or indirectly, the transcription of a number of genes that are related to the acquisition and utilization of iron sources; Fur has also been indicated to regulate many genes that are not related to these functions (6, 12). A number of bacterial species possess, in addition to the siderophore-mediated iron uptake systems, other systems for the uptake of external heme as a sole iron source, and TonB-dependent ABC-type heme transport systems are usually involved in the uptake of heme into the cytoplasm, where ferrous ion is released from heme (13–19). Although heme is very important for various metabolic functions in bacteria (20), free intracellular heme is also very toxic, most likely due to the generation of hydroxyl radical by the heme-mediated Fenton reaction (21). Several regulatory mechanisms for the expression of genes for heme uptake have been clarified (16–19).

The species belonging to the genus Burkholderia in Betaproteobacteria are widely distributed in diverse natural environments (22). Some species are pathogenic to plants, animals, and humans, and other species are potentially useful for the biological suppression of plant diseases and the bioremediation of chemical pollutants. Burkholderia multivorans ATCC 17616 was isolated from a soil sample and is well known for its extraordinary metabolic versatility (12). We previously isolated a fur deletion mutant of ATCC 17616 (DF1) and showed that it exhibited pleiotropic phenotypes, i.e., constitutive secretion of siderophores, enhanced intracellular accumulation of free iron, increased sensitivity to ROS and RNS, drastically reduced assimilation of various carbon sources (including citrate and succinate), and reduced growth fitness in soil (12, 23). We also identified 13 ATCC 17616 loci to which the Fur protein can bind directly. Transcription of all of the loci was repressed under iron-replete conditions, through binding of the active Fur-Fe2+ complex to the Fur boxes that are located close to the promoter regions, and several such loci were suggested to be involved in production and/or secretion of siderophores, uptake of the siderophore-Fe3+ complex, and transcriptional regulation of the genes for these functions (12). To clarify the genetic mechanisms governing the pleiotropic phenotypes of DF1, we isolated spontaneous suppressor mutants of DF1 that restored tolerance to NO, and we found that they exhibited phenotypes very similar to those of the wild-type strain, except for constitutive siderophore secretion (24). The suppressor mutations were located within oxyR, whose product is a transcriptional regulator for H2O2 stress. A DF1 derivative with an oxyR deletion mutation constitutively overproduces enzymes (e.g., KatG, AhpC1, and AhpD) for the detoxification of ROS, thus reducing the amounts of ROS and RNS that are generated abundantly by DF1.

As described above, our previous study indicated the advantages of a genetic approach using suppressor mutations (e.g., those in oxyR) to elucidate the pleiotropic phenotypes of DF1. Accordingly, in this study we isolated suppressor mutants of DF1 that were able to efficiently use succinate as a sole source of carbon. The relevant mutation in one such mutant was mapped within hemP, whose product was found to be a transcriptional regulator for the genes involved in the uptake system of hemin (i.e., b-type heme with a chlorinated ligand). We also show two unique properties of the ATCC 17616 hemP gene product that are not associated with the functional homologues in other heme-utilizing genera.

RESULTS

Identification of spontaneous suppressor mutations of DF1 that restored the ability to use carbon sources efficiently.

The colony-forming ability of DF1 on M9 citrate or succinate minimal agar plates is drastically reduced, by more than 104-fold, compared with the wild-type strain (12). DF1 spontaneously formed large-colony derivatives on such plates, and our investigation of those derivatives revealed that the DF1-associated pleiotropic phenotypes were restored to those of the wild-type strain, except for siderophore secretion (Fig. 1A to E). Subsequent determination of the draft genome sequences of several such derivatives and their comparison with the DF1 sequence indicated that the derivatives had point mutations in oxyR or a 1-base insertion mutation at the 56th codon within a 243-bp gene, bmulj02186. Since bmulj02186 is annotated to encode the probable hemin transporter HemP in the NCBI database, this gene was designated hemP (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). To clarify whether the hemP mutation in one DF1 derivative (designated SUC5) was indeed responsible for the suppression of the DF1-associated phenotypes, a hemP deletion mutation was introduced into DF1. The resulting strain, DFP1, exhibited phenotypes very similar to those of SUC5, and a DFP1 derivative carrying a hemP-containing plasmid (pCP1) exhibited phenotypes indistinguishable from those of DF1 (Fig. 1), confirming the involvement of the hemP mutation in the phenotypes of SUC5. Overproduction of the OxyR-regulated KatG, AhpC1, and AhpD proteins in the DF1 derivatives with oxyR mutations (24) was not observed in SUC5 or DFP1 (Fig. 1F).

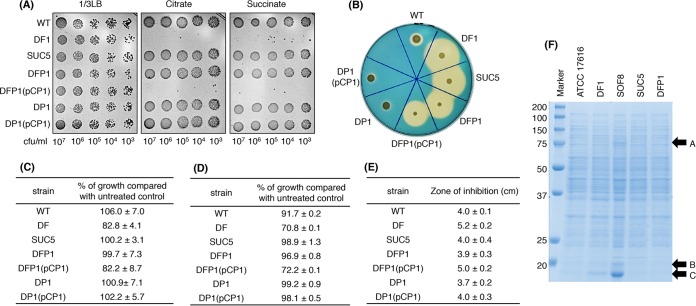

FIG 1.

Phenotypes of ATCC 17616 and its derivatives. (A) Carbon assimilation assay. Aliquots of cell suspensions (5 μl) containing 103 to 107 CFU/ml were spotted on a 1/3LB agar plate (left) and M9 minimal agar plates supplemented with 0.2% citrate (middle) or succinate (right) as the sole carbon source. These plates were incubated at 30°C for 4 days. (B) Secretion of siderophores. The cell suspension used for carbon assimilation was adjusted to a concentration of 107 CFU/ml, and 5 μl of the suspension was spotted on a CAS agar plate containing 30 μM FeCl3. The plate was incubated at 30°C for 4 days. The change of color from blue to orange around the colony indicates the secretion of siderophores. (C) Comparison of intracellular free iron levels with the streptonigrin sensitivity assay. This assay was used to estimate intracellular free iron levels (9). A cell suspension was diluted 100-fold in fresh 1/3LB medium supplemented with 1 mg/ml streptonigrin. The OD660 value of this culture was measured after incubation at 30°C for 16 h, and the sensitivity to streptonigrin was expressed as a percentage of the value for the control culture without the addition of streptonigrin. Mean ± standard deviation (SD) values from three independent experiments are shown. (D) Cellular sensitivity to acidified nitrite. A cell suspension was diluted 100-fold in fresh 1/3LB medium supplemented with 1 mM acidified nitrite (a NO producer). The OD660 value of this culture was measured after incubation at 30°C for 16 h, and the sensitivity to acidified nitrite was expressed as a percentage of the value for the control culture without the addition of acidified nitrite. Mean ± SD values from three independent experiments are shown. (E) Cellular sensitivity to H2O2. A cell suspension was diluted with 1/3LB to a concentration of 107 CFU/ml, and 100 μl of the suspension was spread on a 1/3LB agar plate. A sterilized filter paper disc was placed on the plate, and 10 μl of 30% H2O2 was spotted on each disc. After incubation of the plate at 30°C for 2 days, the diameter of the growth inhibition zone around the disc was measured. Mean ± SD values for the diameters of the inhibition zones from three independent experiments are shown. (F) SDS-PAGE analysis of crude cell extracts. Twenty milligrams of protein from crude extracts of ATCC 17616, DF1, SOF8 (an oxyR mutant of DF1) (24), SUC5, and DFP1 cells at mid-exponential phase was loaded in each lane of a 15% SDS-PAGE gel. Bands A, B, and C correspond to KatG, AhpC1, and AhpD, respectively. WT, wild type.

Genetic analysis of ATCC 17616 hemP and hmuR genes for hemin utilization.

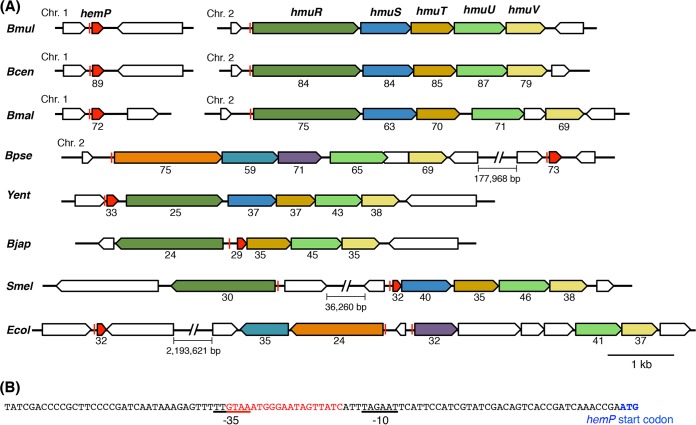

The hemP gene of B. multivorans ATCC 17616 was located on its main chromosome (chromosome 1), and the gene is conserved in many other Burkholderia species (Fig. 2A). Some strains in these species have been shown to utilize extracellular hemin as a sole source of iron (15). Kvitko et al. (25) experimentally identified the Burkholderia pseudomallei hmuRSTUV cluster that encodes a TonB-dependent ABC transporter system for the uptake and utilization of hemin, and in the present study we found a similar gene cluster on chromosome 2 in ATCC 17616 (Fig. 2A). Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis using the primer sets for detection of transcriptional read-through between two neighboring genes within the ATCC 17616 hmuRSTUV cluster supported the structure of the hmu operon, whose transcriptional start site is located upstream of hmuR (data not shown). Our previous ATCC 17616 study (12) showed that (i) the promoter-containing fragments of both the hemP gene (which was designated a gene for a conserved hypothetical protein at the time of publication) and the hmuR gene carry functional Fur boxes (Fig. 2) and (ii) the two genes are transcriptionally repressed and derepressed under iron-replete and iron-poor conditions, respectively. Such transcriptional regulation of two genes was confirmed in this study with the use of M9 minimal liquid medium supplemented with ferric ion or its chelator, 2,2-dipyridyl (Dpr) (Fig. S2). To clarify the involvement of the ATCC 17616 HemP product in the utilization of hemin, the hemP deletant DP1 was constructed. The growth of DP1 was impaired severely in M9 minimal liquid medium supplemented with hemin as the sole iron source but was normal in medium supplemented with FeCl3 (Fig. 3A to C), indicating a crucial role of HemP in hemin utilization.

FIG 2.

Organizations of hemP and hmu genes in B. multivorans ATCC 17616 and comparison with those in other species. (A) Comparison of the ATCC 17616 genes with those in other bacterial species. Genes are color-coded and are annotated as follows: hemP, regulator of hmu operon; hmuR, TonB-dependent outer membrane heme receptor; hmuS, cytoplasmic heme-binding protein/heme oxygenase; hmuT, periplasmic heme-binding protein; hmuU, permease subunit of inner membrane heme transporter; hmuV, ATP-binding cassette subunit of inner membrane heme transporter. Chr. 1 and Chr. 2, chromosomes 1 and 2, respectively. The red lines indicate the binding sites of Fur or its functional homologue. Abbreviations of strain names are as follows: Bmul, Burkholderia multivorans ATCC 17616; Bcen, Burkholderia cenocepacia J2315; Bmal, Burkholderia mallei ATCC 23344; Bpse, Burkholderia pseudomallei 1710b; Yent, Yersinia enterocolitica 0:8; Bjap, Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA110; Smel, Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021; Ecol, Escherichia coli O157:H7. The hemP homologues from B. japonicum and S. meliloti are designated hmuP. Numbers under the maps show the percent identity of amino acid sequences, compared with that encoded by ATCC 17616. (B) Sequence upstream of hemP in the ATCC 17616 genome. The putative Fur box is shown in red.

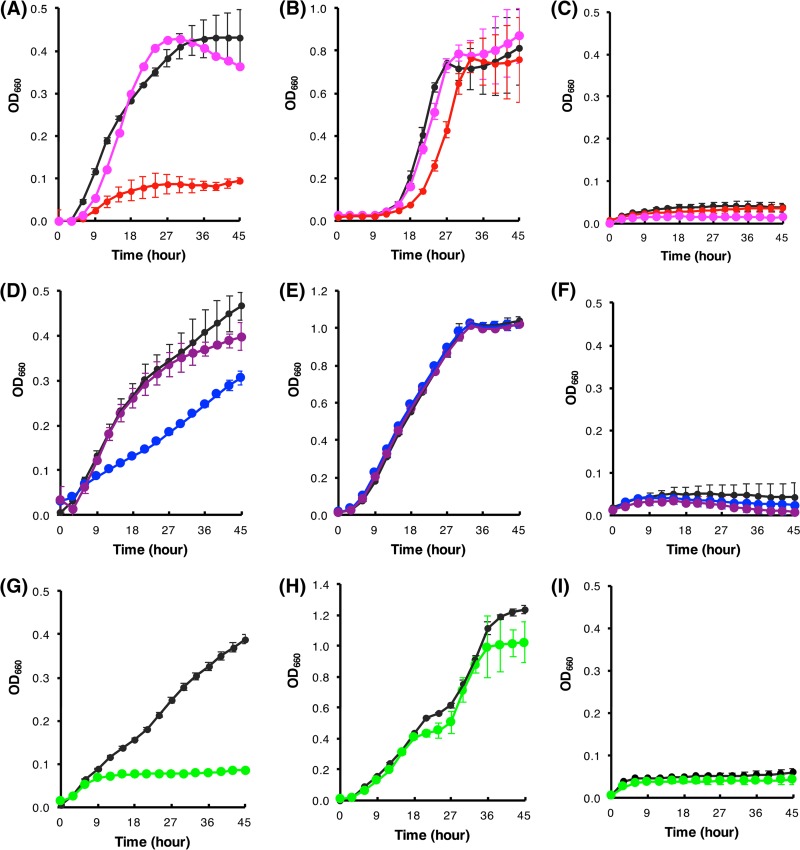

FIG 3.

Growth of ATCC 17616 and its derivatives in liquid media with different iron sources. The strains inoculated were ATCC 17616 (black), DP1 (red), DP1(pCP1) (pink), DR1 (blue), DR1(pCR1) (purple), and DPR1 (green). Growth media were M9 glucose minimal liquid medium supplemented with Dpr and hemin in panels A, D, and G, with FeCl3 in panels B, E, and H, and with Dpr in panels C, F, and I. See Materials and Methods for details. Each OD660 value with a SD (vertical bar) was obtained in at least three independent experiments.

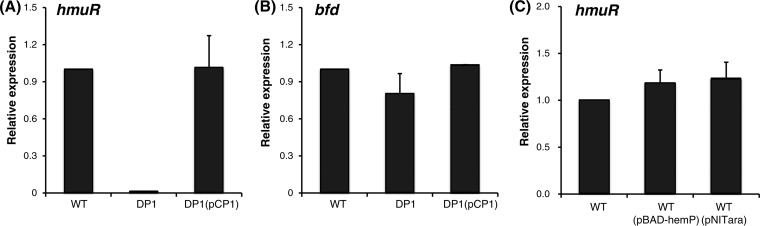

The HmuP proteins from Bradyrhizobium japonicum and Sinorhizobium meliloti are transcriptional activators for the genes encoding outer membrane heme receptors in the heme uptake system (26, 27). Although the overall amino acid sequence similarity of the two proteins with the ATCC 17616 HemP protein is approximately 30% (Fig. 2A), much greater similarity is conserved among the C-terminal portions of the three proteins (Fig. S1B). Taking these facts into consideration, the regulatory role of the HemP protein in the expression of the ATCC 17616 hmu operon was investigated by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis. DP1 cells that were exposed to the Dpr-supplemented M9 minimal medium exhibited no detectable transcription of hmuR but showed normal transcription of bfd (12), a Fur-regulated gene for bacterioferritin-associated ferredoxin (Fig. 4A and B; also see Fig. S1B). DR1 (ATCC 17616 ΔhmuR) was still able to grow using hemin as the sole iron source, albeit at a rate clearly lower than that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 3A and D to F), whereas the growth of DPR1 (ATCC 17616 ΔhemP ΔhmuR) in the same medium was severely impaired, similar to that of DP1 (Fig. 3G to I). These results suggested (i) the involvement of HmuR in hemin utilization and (ii) the presence in ATCC 17616 of at least a part of one or more unknown efficient hemin utilization systems whose expression depends on the HemP function.

FIG 4.

Effects of HemP on the expression of hmuR and bfd genes. (A and B) qRT-PCR analysis of the ATCC 17616 hmuR (A) and bfd (B) genes, which are both transcriptionally repressed by the Fur-Fe2+ complex (12). The cells were cultivated in 1/3LB, washed with M9 minimal medium, and suspended in the same medium. The suspension was exposed to Dpr at 30°C for 30 min and was used to prepare RNA for qRT-PCR analysis. Transcriptional levels are expressed as relative values, compared with the wild-type strain. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of hmuR under conditions of constitutive expression of the hemP gene. A cell suspension, prepared as described above, was exposed to FeCl3 alone or FeCl3 and 0.2 mM arabinose and was used for qRT-PCR analysis. Each value with a SD (vertical bar) was obtained in at least three independent experiments. WT, wild type.

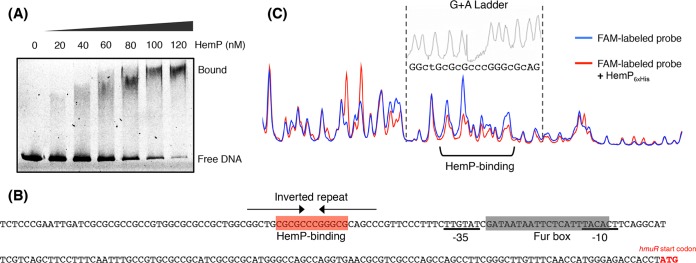

DNA-binding ability of HemP.

The possibility that HemP binds to the promoter-containing region of hmuR was investigated with an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) (Fig. 5A). The 81-amino-acid HemP protein (8.5 kDa in size) was tagged with six histidine residues at the C terminus (HemP6×His) and purified (Fig. S3); it was found to be specifically bound to a 221-bp promoter-containing region (Fig. 5B). Subsequent DNase I footprinting analysis of this region using HemP6×His (Fig. 5C) revealed its protection of a 12-bp tract within an inverted repeat sequence whose center was located 22 bp upstream of the −35 box for hmuR.

FIG 5.

Binding of HemP6×His to the fragment upstream of hmuR. (A) EMSA for HemP6×His binding to the FAM-labeled 221-bp fragment. The mobility shift was not affected by the addition of a 100-fold excess of salmon sperm DNA and was almost completely abolished by the addition of a 100-fold excess of the nonlabeled fragment (data not shown). (B) Sequence of the 221-bp fragment used for this analysis. The protected region (HemP binding) is shown by red shading and an inverted repeat by arrows. (C) DNase I footprinting analysis. The FAM-labeled 221-bp fragment was digested by DNase I in a reaction mixture supplemented with (red) or without (blue) the purified HemP6×His protein. The data obtained were analyzed with TraceViewer software. See Materials and Methods for details.

The in vitro experimental results presented above strongly suggested that the HemP-binding site in the hmuR-upstream region is followed, in order, by the −35 box, the Fur box, and the −10 box (Fig. 5B). It was of interest to determine whether the binding of HemP at its cognate site overcomes the Fur-mediated transcriptional repression of the hmuR gene under iron-replete conditions. To investigate this plausible event, we constructed a plasmid, pBAD-hemP, whose hemP transcription is designed to be induced, resulting in protein overproduction, in the presence of arabinose in the medium. Transcriptional levels of hmuR in ATCC 17616 and ATCC 17616(pBAD-hemP) under iron-replete conditions were measured in the presence of arabinose. As shown in Fig. 4C, the hmuR transcriptional levels were similar in the two strains, and there was no apparent increase in hmuR transcription in the latter strain. This result strongly suggested that the Fur-Fe2+ complex that binds to the Fur box in the hmuR promoter region does not allow HemP-mediated transcriptional activation of the hmuR operon.

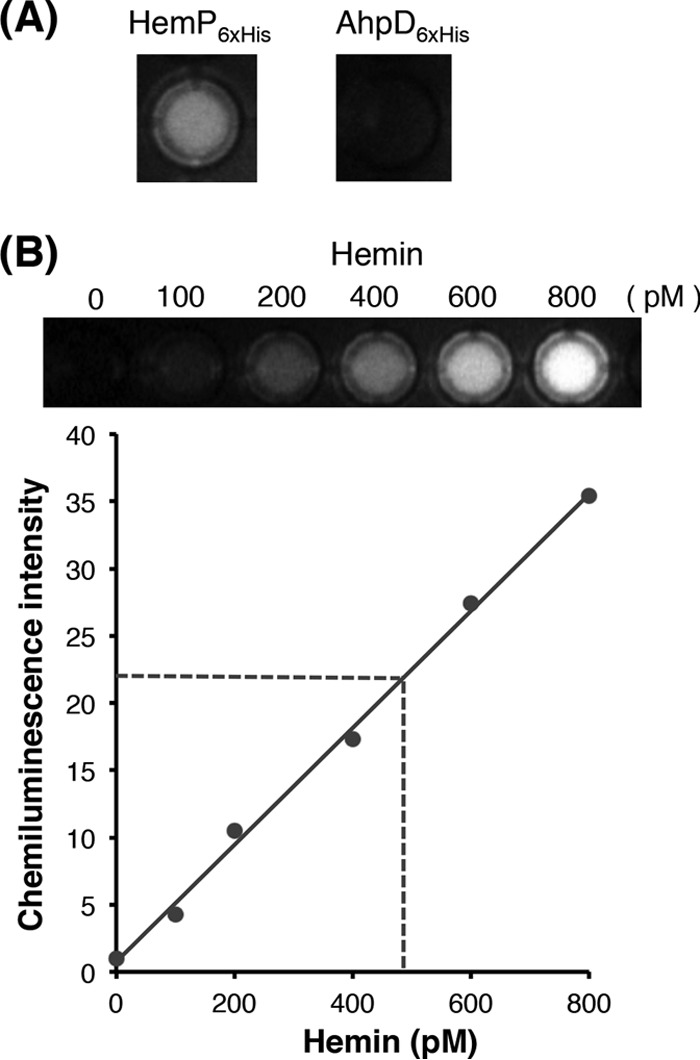

Hemin-binding ability of HemP.

The C-terminal histidine and tyrosine residues of the heme-binding protein HasA from Pseudomonas aeruginosa have been shown to participate in the binding to heme (28, 29), and the two residues are conserved among the HemP superfamily proteins (Fig. S1B). Our three-dimensional structure analysis of another heme-binding protein, i.e., YdiE from Escherichia coli (30), which exhibits 43% amino acid sequence similarity with ATCC 17616 HemP, showed that the two residues are located in close proximity to each other. Homology modeling using SWISS-MODEL (https://swissmodel.expasy.org) was applied to HemP and YdiE. The results predicted close localization of the two residues in the three-dimensional structure of HemP, suggesting the possible binding of HemP to heme. This possibility was investigated in vitro using a quantitative horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-based heme assay system in which a protein possessing heme-binding ability generates chemiluminescence (see Materials and Methods for details) (31). After the incubation of HemP6×His with hemin and subsequent removal of free hemin, the amount of hemin bound to HemP6×His was measured. The results indicated that much stronger chemiluminescence was detected with the HemP6×His protein than with the AhpD6×His protein (an AhpD derivative with six histidine residues at the C terminus), which is not be expected to bind hemin (Fig. 6A). Based on a calibration curve of chemiluminescence intensities determined using various known concentrations of hemin, 1 μM HemP6×His was calculated to bind 460 pM hemin (Fig. 6B). Taking into account the hemin extraction efficiency in this study, the calculated value suggested stoichiometric binding of HemP6×His to hemin.

FIG 6.

Binding of HemP6×His to hemin. The HemP6×His protein incubated with hemin was repurified, and bound hemin was extracted with acidified acetone. Apo-HRP and HRP substrates were added to the extract, and chemiluminescence was measured. See Materials and Methods for details. (A) Well images of reactions with the extract using 1 μM HemP6×His (left) or AhpD6×His (right). (B) Calibration curve prepared by using different concentrations of hemin (0, 100, 200, 400, 600, and 800 pM). Each value with a SD (vertical bar) was obtained from at least three independent experiments. The intensity value measured with 1 μM HemP6×His in panel A is depicted as a horizontal dashed line.

DISCUSSION

The transcriptional regulation of gene clusters for heme uptake systems in various Gram-negative bacterial species has been investigated, and the transcription of such genes in most species (except for alphaproteobacterial species) was found to be commonly repressed under iron-replete conditions, through the involvement of the active form of Fur. The transcription of heme uptake gene clusters is also positively regulated by various mechanisms in the presence of heme. Such mechanisms are exemplified by (i) the system consisting of an inner membrane-spanning heme-sensor protein with anti-sigma-factor activity and an extracytoplasmic sigma factor (ECF) protein in P. aeruginosa and Serratia marcescens (19), (ii) the two-component heme-responsive sensor-regulator system in Neisseria meningitidis (17), (iii) the LysR-type activator system in Vibrio spp. (18), and (iv) the HmuP activator (belonging to the HemP superfamily) system (Fig. S1) in B. japonicum and S. meliloti, which belong to the alphaproteobacterial genera (16). The genes encoding such regulatory systems have been shown to be almost always located adjacent to the structural gene clusters for heme uptake.

Although analysis of the genomes of various Burkholderia species has suggested their use of hemin as a sole source of iron, only a few Burkholderia cenocepacia and B. pseudomallei strains have been experimentally confirmed to utilize external hemin (6, 25, 32). However, the mechanisms for transcriptional regulation of the genes for heme uptake systems in these strains have remained unknown. In our previous study, B. multivorans ATCC 17616 was suggested to use hemin as an iron source, and the putative gene cluster for hemin uptake (hmu operon) and the hemP gene (which was uncharacterized at that time) were both shown to be transcriptionally repressed by the Fur-Fe2+ complex under iron-replete conditions. Our investigation of ATCC 17616 in this study clearly showed (i) its ability to use hemin as a sole source of iron and (ii) the requirement for HemP for transcription of the hmu operon. The ATCC 17616 hemP gene was found to be located far from its hmu operon. This distant localization of the regulator gene from the structural hmu gene cluster is apparently conserved in various other Burkholderia species, which is not generally the case in other bacterial genera that encode HemP superfamily proteins (Fig. 2A).

The HemP superfamily proteins show very high levels of similarity in their C-terminal 20 amino acid residues, with the conserved KLILXK motif at their C termini (Fig. S1B) (26, 27). Despite of the high level of conservation of these proteins among various proteobacteria, their experimental characterization has been limited to the HmuP proteins from S. meliloti and B. japonicum, and both proteins are required for heme uptake (26, 27). Each HumP protein is a transcriptional activator for the gene encoding the outer membrane receptor protein for heme uptake but not for the hmuP-containing operon that encodes the remaining proteins for the heme uptake system (Fig. 2A). The KLILXK motif in the former HmuP protein has been shown to be important for transcriptional activity (26). Expression of the two hmu transcriptional units in each species is also transcriptionally regulated by the concentrations of external iron; expression is repressed in the former species by RirA, a pleiotropic regulator that is active under iron-replete conditions, and is activated in the latter species by Irr (iron response regulator), a pleiotropic regulator that is produced abundantly under iron-depleted conditions. It should be noted that the two species do not encode Fur for transcriptional regulation of the iron regulon (16). The mechanism for transcriptional regulation of genes for heme uptake in B. multivorans ATCC 17616 resembles that in these two species, in that (i) each HemP homologue is a transcriptional activator for the heme receptor-encoding gene, and (ii) transcription of each hemP homologue is regulated by a pleiotropic regulator (Fur, RirA, or Irr) whose activity or abundance depends on the external iron concentration. However, the three pleiotropic regulators differ significantly in their amino acid sequences. One feature associated only with ATCC 17616 is that its HemP protein activates the transcription of a whole set of structural genes required for hemin uptake, which reflects the operon structure of the hmuRSTUV cluster. Considering our findings that the hemP and hmuR deletants of ATCC 17616 exhibited nearly complete and partial deficiencies, respectively, of growth in the hemin-containing M9 minimal medium (Fig. 3), the HemP protein most likely regulates at least the expression of other, currently unidentified genes (other than the hmu operon) for alternative hemin uptake systems. The presence of such predicted alternative systems is unlikely in the two alphaproteobacterial species and B. pseudomallei, because their derivatives lacking the identified heme-receptor-encoding genes demonstrated the loss of heme-utilizing ability (25–27). To our knowledge, the predicted multiple regulatory roles of HemP in ATCC 17616 represent a novel property that is not observed for the other HemP superfamily proteins.

There have been no experimental results clearly showing the direct binding of HmuP to its target DNA sequences in the two alphaproteobacterial species (16). However, our EMSA and DNase I footprinting analysis in this study revealed the specific binding of the ATCC 17616 HemPHisx6 protein to the sequence upstream of the Fur-box-containing promoter region of the hmu operon (Fig. 5). Since transcriptional activation of the ATCC 17616 hmu operon was similarly observed when the gene encoding HemP6×His was supplied instead of the wild type (data not shown), it is quite unlikely that the addition of six histidine residues to the C terminus of HemP drastically affects the binding affinity of HemP6×His for the target sequence. The relative positions of the HemP- and Fur-Fe2+-binding sites in the humR-upstream region are suitable to explain our observation that the Fur-mediated repression of the hmu operon is epistatic to the HemP-mediated activation (Fig. 4C); binding of the Fur-Fe2+ complex to the Fur box within the hmu promoter region hinders RNA polymerase from binding to the promoter even in the situation in which HemP is allowed to bind to its biding site for activation of transcription of the hmu operon. Our in vitro analysis showed strong binding affinity of HemP for hemin (Fig. 6). If this is also the case in vivo, then the HemP-heme complex might contribute to modulating its interaction with the hmuR-upstream region so as to more effectively regulate transcription of the hmu operon. In spite of the ability of HemP to bind to its target DNA sequence, no canonical DNA-binding helix-turn-helix motifs were predicted in HemP, and this was also the case with other HemP superfamily proteins, including the HmuP proteins from the two alphaproteobacterial species (26, 27). Three-dimensional structure modeling of the S. meliloti HmuP protein has predicted that it consists of three β-sheets and one small α-helix, probably with a dimer form, and that the KLILXK motif is located within the C-terminal β-sheet (26). It is presently not known which amino acid residues in the ATCC 17616 HemP protein and which nucleotide residues in the HemP-binding site are critical for binding. Our future detailed mutational analysis of HemP and its binding site will help to clarify the mechanisms for HemP-mediated transcriptional activation.

The mechanism by which almost all of the pleiotropic phenotypes observed in the ATCC 17616 Δfur mutant (DF1) are suppressed by the additional introduction of the hemP mutation remains unclear. However, this mechanism is quite likely to differ from the mechanism by which the oxyR mutation suppresses the pleiotropic phenotypes of the Δfur mutant, since the constitutive overproduction of KatG and AhpC1D proteins in the Δfur ΔoxyR mutant (21) was not detected in the Δfur ΔhemP mutant (DFP1) (Fig. 1F). Our present study showed a constitutive and high level of hemP transcription in DF1. When we further consider that HemP is suggested to positively regulate at least the expression of unidentified hemin-utilizing genes (Fig. 3 and 4), it is plausible that HemP also regulates the expression of other genes. As a transcriptional regulator, HemP might function either directly or indirectly (i) to positively regulate the expression of unknown genes for the enhanced generation of ROS or (ii) to negatively regulate the expression of unknown genes for the detoxification of ROS. Such a mechanism might account for the phenotypes of DFP1 in which ROS are not overproduced. Constitutive and high-level production of HemP in DF1 would be expected to lead to overproduction of HmuS. Some HmuS homologues from other genera have been reported to function as heme oxygenases that degrade heme to release free iron (15, 17). If the ATCC 17616 HmuS protein has such an activity, then the overproduced HmuS protein in DF1 would result in drastic increases in the levels of free iron produced from intracellular heme, and the increased levels of free iron would in turn generate large amounts of ROS. Introduction of the hemP mutation into DF1 might be able to block the release of iron from intracellular heme, thereby reducing the generation of ROS. This alternative possibility will be clarified by investigating the heme oxygenase activity of HmuS and the amounts of free heme in DF1 and DFP1. For investigation of the latter point, it is necessary to establish an assay system to measure the amounts of free intracellular heme in bacteria. Use of such an experimental system in our future work will greatly contribute to our understanding of the detailed role of HemP in heme uptake.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

Table 1 lists the bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study. B. multivorans and E. coli cells were cultivated at 30°C and 37°C, respectively. The liquid media used were LB broth, 1/3LB broth, and M9 minimal medium supplemented with an appropriate carbon source (glucose, citrate, or succinate) at a concentration of 0.2% (24). Solid media were prepared by the addition of 1.5% agar. Chrome azurol S (CAS) agar plates (33) were used to monitor the secretion of siderophores. When required, FeCl3, hemin (Sigma-Aldrich Japan, Tokyo, Japan), and Dpr (Sigma-Aldrich) were added to the media at final concentrations of 30, 30, and 200 μM, respectively. The antibiotics added to media were as follows: ampicillin (Ap) at 100 μg/ml, kanamycin (Km) at 50 μg/ml, and tetracycline (Tc) at 10 μg/ml for E. coli and chloramphenicol (Cm) at 100 μg/ml, Km at 100 μg/ml, and Tc at 50 μg/ml for B. multivorans.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 Δ(lac)U169 (ϕ80dlacZΔM15) | 39 |

| JM109 | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 relA1 Δ(lac-pro) [F′ traD36 proAB+ lacIqZΔM15] | 40 |

| BL21Star(DE3) | ompT hsdB (rB− mB−) gal dcm λ (DE3) | Thermo Fisher Scientific |

| B. multivorans | ||

| ATCC 17616 | Soil isolate; type strain | ATCC |

| DF1 | Cmr; ATCC 17616 fur deletion mutant | 12 |

| SOF8 | Spontaneous suppressor mutant of DF1 that restored tolerance to NO | 24 |

| SUC5 | Spontaneous suppressor mutant of DF1 that restored ability to use succinate as carbon source | This study |

| DP1 | ATCC 17616 hemP deletion mutant | This study |

| DFP1 | Cmr; ATCC 17616 fur and hemP deletion mutant | This study |

| DR1 | ATCC 17616 hmuR deletion mutant | This study |

| DPR1 | ATCC 17616 hemP and hmuR deletion mutant | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pEX18Tc | Tcr, sacB oriT; suicide vector for gene replacement, carrying pUC18-derived MCS | 41 |

| pBBR1MCS-3 | Tcr; shuttle vector able to replicate in E. coli and B. multivorans | 42 |

| pCF1 | Kmr; pME6041 (shuttle vector able to replicate in E. coli and B. multivorans) derivative carrying fur gene | 12 |

| pCP1 | Tcr; pBBR1MCS-3 carrying hemP gene with its authentic promoter | This study |

| pCR1 | Tcr; pBBR1MCS-3 carrying hmuR gene with its authentic promoter | This study |

| pNIT6012 | Tcr; shuttle vector able to replicate in E. coli and B. multivorans | 43 |

| pNIT6012dS | Tcr; SmaI site-added derivative of pNIT6012 | 36 |

| pKD46 | Apr, oriR101(repA101ts); λRed recombinase expression plasmid | 35 |

| pNITara | pNIT6012dS carrying araC gene and pBAD promoter from pKD46 | This study |

| pBAD-hemP | Tcr; pNITara carrying hemP gene without its authentic promoter; arabinose-inducible expression of hemP | This study |

| pET22b(+) | Apr; C-terminal 6×His tag | Novagen |

| pEThemP | Apr; pET22b(+) derivative for overexpression of C-terminal His-tagged HemP protein | This study |

| pETahpD | Apr; pET22b(+) derivative for overexpression of C-terminal His-tagged AhpD protein | This study |

r, resistant.

Bacterial growth in liquid medium was monitored using the Infinite M200 microplate reader system (Tecan Japan, Kawasaki, Japan). Bacterial cells cultivated overnight in 1/3LB broth were washed three times with M9 minimal medium and suspended in the same medium so that the optical density at 600 nm (OD660) value was adjusted to 1.0. A 0.1% aliquot of such suspension was inoculated in 200 μl of appropriate liquid medium in each well of a 96-well microtiter plate and used for measurements of OD660 values at different time points during the incubation.

Basic DNA and RNA manipulations.

Established procedures were employed for the preparation of genomic and plasmid DNA, DNA digestion with restriction enzymes, ligation, agarose gel electrophoresis, and transformation of E. coli and B. multivorans (12, 24). PCR amplification of DNA fragments was carried out using Ex Taq DNA polymerase (TaKaRa, Otsu, Japan) or KOD-plus DNA polymerase (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan), and the primers used in this study are listed in Table 2. PCR products were cloned into multiple cloning sites (MCS) on vector plasmids using restriction enzymes followed by ligation mix (TaKaRa) or a Gibson assembly cloning kit (New England BioLabs, Beverly, MA).

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Purpose and primer name | Sequence (5′ to 3′)a | Use |

|---|---|---|

| Allelic exchange mutagenesis | ||

| hemP_UP_FW | CGACTCTAGAGGATCTACCGAAGAAGAGATTCGG | Upstream region of hemP |

| hemP_UP_RV | GCCCAACACCTCTCAGTCGATAGCTTGAAGCAAAC | |

| hemP_DOWN_FW | TGAGAGGTGTTGGGCATTA | Downstream region of hemP |

| hemP_DOWN_RV | CGGTACCCGGGGATCGCAGATCAAGCAGTGGCT | |

| hmuR_UP_FW | TAAAACGACGGCCAGTGCCATTCAACGAACGCGGCGTGACC | Upstream region of hmuR |

| hmuR_UP_RV | CTTGAGCTTCAGGGAACGGGCTGCGCCC | |

| hmuR_DOWN_FW | CCCGTTCCCTGAAGCTCAAGCGCGAGCG | Downstream region of hmuR |

| hmuR_DOWN_RV | CAGCTATGACCATGATTACGCCGGATCGAGCACGTTGATC | |

| Complementation analysis | ||

| pBBR_hemP_FW | CCACCGCGGTGGCGGCCGCTTACGGTGCGCCTGATTCGC | Construction of pCP1 |

| pBBR_hemP_RV | GCTGGGTACCGGGCCCCCCCGCGAGCGAATGGAGGCGC | |

| pBBR_hmuR_FW | CCACCGCGGTGGCGGCCGCTCCGGGCGCAGCCCGTTCC | Construction of pCR1 |

| pBBR_hmuR_RV | GCTGGGTACCGGGCCCCCCCACGAACGCGTCGCGCAGC | |

| XhoI_paraBC | CCCCTCGAGCCAAAAAAACGGGTATGGAG | Construction of pNITara |

| paraBC_NheI | CCCGCTAGCTTTATTATGACAACTTGACG | |

| pNITara_hemP_EcoRI | GGGGAATTCATTCATTCCATCGTATCGACAGT | Construction of pBAD-hemP |

| pNITara_hemP_HindIII | GGGAAGCTTCGAATGGAGGCGCACAAATAA | |

| qRT-PCR | ||

| dnaA_F | GGCGTTCGACGATTTCAAGC | Transcription of dnaA |

| dnaA_R | CGAACGCGTAGAAGAATTCC | |

| hemP_F | CAAGGTCACAGCCATATCAG | Transcription of hemP |

| hemP_R | CTTCGTCAGGATCAGCTTGC | |

| hmuR_F | GTATCTGCAGTACGCACATG | Transcription of hmuR |

| hmuR_R | GATTGCCGATCGAGGTATAG | |

| bfd_F | GTTTCCGATCGGAAGATTCG | Transcription of bfd |

| bfd_R | GTACCGACTCCTCGCATTTG | |

| Protein purification | ||

| NdeI_hemP | GGGCATATGACCGACACCATGCGCCC | Construction of pEThemP |

| XhoI_hemP | GGGCTCGAGCTTCGTCAGGATCAGC | |

| NdeI_ahpD | GGGCATATGGAATTCATCGATTCGATTAAGG | Construction of pETahpD |

| XhoI_ahpD | GGGCTCGAGTTCGCCTTCGGCGG | |

| EMSA | ||

| pNIT_hmuR_pro_NheI | GGGGCTAGCGTCTCCCGAATTGATCGCGCG | Upstream region of hmuR |

| pNIT_hmuR_pro_HindIII | GGGAAGCTTAGGTGGTCTCCCATGGTTGA | |

| pNIT_5041 | CTGACACCCTCATCAGTGCCAA | Construction of probe |

| pNIT_5548 | GTGAGAAATCACCATGAGTGACG |

Restriction sites are underlined.

Sequence determination was performed using an ABI Prism model 3130xl sequencer and an ABI Prism BigDye termination kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Draft genome sequencing was carried out using the HiSeq 1000 sequencing system (Illumina, San Diego, CA) and the 454 GS FLX titanium system (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), and mutation sites were identified by using ShortReadManager software (34). An RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was used to prepare total cellular RNA from B. multivorans cells cultivated in liquid medium. RT-PCR was carried out with Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or a ReverTra Ace kit (Toyobo), and the resulting cDNA samples were employed for qRT-PCR analysis using the Opticon 2 system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and a SYBR Premix Ex Taq kit (TaKaRa). The mRNA levels were normalized to those of a housekeeping gene, dnaA.

Construction of plasmids and strains.

E. coli strain DH5α or JM109 was used for construction of plasmids. To delete the hemP gene from the ATCC 17616 genome, ∼800-bp fragments upstream and downstream of hemP were PCR amplified using the ATCC 17616 genome as a template and the primer pairs of hemP_UP_FW/hemP_UP_RV and hemP_DOWN_FW/hemP_DOWN_RV, respectively. A Gibson assembly cloning kit was used to insert the two amplicons into the EcoRI and HindIII sites on pEX18Tc so that they were arranged in the same order as in the genome. The resulting plasmid was introduced into ATCC 17616 or its derivatives by transformation to select Tc-resistant clones, in which the plasmid was integrated into the genome by single crossover-mediated homologous recombination between the fragment shared by the genome and the introduced plasmid. Subsequent exposure of the transformants to 10% sucrose led to the formation of Tc-sensitive segregants, and some of them were confirmed by PCR to lack the hemP gene, with concomitant loss of the pEX18Tc portion through a second single crossover-mediated homologous recombination event. The hemP deletants of ATCC 17616 and DF1 were designated DP1 and DFP1, respectively. A similar procedure was employed to delete the hmuR gene from the ATCC 17616 genome. In this case, the primer pairs hmuR_UP_FW/hmuR_UP_RV and hmuR_DOWN_FW/hmuR_DOWN_RV were used to PCR amplify the DNA fragments upstream and downstream of hmuR, respectively. The hmuR deletants of ATCC 17616 and DP1 were designated DR1 and DPR1, respectively.

The primer pairs pBBR_hemP_FW/pBBR_hemP_RV and pBBR_hmuR_FW/pBBR_hmuR_RV were used to PCR amplify the ATCC 17616 hemP and hmuR genes, respectively, with their authentic promoter-containing fragments. A Gibson assembly cloning kit was used to insert the two amplicons into the XbaI and XhoI sites on pBBR1MCS-3 to obtain pCP1 and pCR1, respectively. To construct pNITara, a DNA fragment containing the araC gene and pBAD promoter on pKD46 (35) was amplified by PCR using the primer set of XhoI_paraBC and paraBC_NheI, and the resulting amplicon was inserted into the MCS on pNIT6012dS, after treatment with XhoI and NheI (36). The ATCC 17616 hemP gene without its promoter-containing fragment was PCR amplified using the primer set of pNITara_hemP_EcoRI and pNITara_hemP_HindIII, and the EcoRI- and HindIII-treated amplicon was inserted into the corresponding sites of pNIT6012dS so that the hemP gene was just downstream of the pBAD promoter. The resulting plasmid was designated pBAD-hemP. The primer pairs NdeI_hemP/XhoI_hemP and NdeI_ahpC/XhoI_ahpC were used to PCR amplify the ATCC 17616 hemP and ahpD genes, respectively. After treatment with NdeI and XhoI, the amplicons were inserted into the corresponding sites on pET22b(+) to obtain pEThemP and pETahpD, respectively.

Phenotype analysis.

ATCC 17616 and its derivatives were analyzed for their carbon assimilation ability, secretion of siderophores, levels of free intracellular iron, and sensitivity to RNS and ROS, as in our previous studies (12, 24). Cells grown to late-exponential phase in 1/3LB broth were used for the phenotype analysis. Cells were washed three times with M9 minimal medium and suspended in the same medium to yield suspensions with OD660 values of 1.0, which corresponded to CFU values of approximately 109 CFU/ml. These suspensions were serially diluted 100-fold to obtain suspensions with CFU values of 103 CFU/ml to 107 CFU/ml. A 5-μl portion of each cell suspension was spotted on an M9 minimal agar plate supplemented with 0.2% citrate or succinate as the sole carbon source for the carbon assimilation assay or on a CAS agar plate containing 30 μM FeCl3 for assessment of siderophore secretion. Cells cultivated in 1/3LB broth (see above) were washed three times with 1/3LB broth, and cell suspensions in fresh 1/3LB broth were used for determination of cellular free iron levels and sensitivities to RNS and ROS.

Preparation of crude cell extracts.

Cells grown to mid-exponential phase in 1/3LB broth were disrupted by sonication. The lysates were recovered by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 15 min, and proteins were separated by using SDS-PAGE. The protein bands were stained using Coomassie brilliant blue.

Purification of His-tagged derivatives of HemP and AhpD and their biochemical analysis.

When LB cultures of E. coli BL21Star(DE3) cells carrying pEThemP or pETahpD reached mid-log phase, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added at a final concentration of 0.5 mM. After additional incubation for 8 h at 25°C, the cells were collected and disrupted using CelLytic B reagent (Sigma-Aldrich). The IPTG-induced HemP or AhpD derivative tagged with six histidine residues at the C terminus was purified using Talon metal affinity resins (TaKaRa), according to the manufacture's protocol.

For EMSA of the HemP6×His-binding DNA sequence, a 221-bp DNA fragment upstream of hmuR was amplified by PCR using the primers pNIT_hmuR_pro_NheI and pNIT_hmuR_pro_HindIII, and the amplicon was digested with NheI and HindIII and then inserted into the MCS on pNIT6012. The hmuR-upstream region of the resulting plasmid, pNITupR, was amplified by PCR using the primers pNIT_5041 and pNIT_5548, each 5′ end of which was labeled with 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM) (Eurofins Genomics, Tokyo, Japan). A reaction mixture containing 2 μg/μl of the PCR-amplified and FAM-labeled DNA fragment and the HemP6×His protein at final concentrations ranging from 0 to 120 nM, in 20 μl of binding buffer (10% glycerol in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]), was incubated for 3 min at 30°C. The reaction mixture was loaded onto a 12.5% (wt/vol) nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel in PBS. After electrophoresis for 1 h at 80 mA, the gel was exposed to an imaging plate, and the gel image was analyzed using the BAS-1000 system (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

For DNase I footprinting analysis, pNITupR was used as a template to PCR amplify the 221-bp upstream fragment of hmuR using the primer set of pNIT_5548 and 5′-FAM-labeled pNIT_5041. A 20-μl aliquot of a reaction mixture containing 200 nM HemP6×His, 400 ng of labeled DNA, 10% glycerol in PBS, and 0.0014 unit of DNase I (TaKaRa) was kept at 30°C for 3 min and then at 95°C for 10 min. The DNase I-digested fragments were purified by phenol-chloroform/isoamyl alcohol extraction and ethanol precipitation. The purified fragments and GeneScan-500 LIZ size standard (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were dissolved in HiDi formamide. A Maxam-Gilbert G+A sequencing ladder was prepared as described previously (37), using the same DNA fragment as used for detection of the HemPHisx6-binding site. The samples were analyzed using a 3130xl genetic analyzer, a G5 dye set, the POP-7 polymer, and 50-cm capillaries. The data were analyzed by using TraceViewer software (http://www.ige.tohoku.ac.jp/joho/gmProject/gmdownload.html) (38), and the LIZ bands were used for calibration.

In vitro hemin-binding assay.

The HemP6×His or AhpD6×His (negative control) protein was mixed with 100 μM hemin in 100 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.0) for 30 min at 25°C; the protein was subsequently affinity purified as described above and resolved in 100 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.0). Four hundred microliters of acidified acetone was added to 100 μl of solution with 5 μM protein, and the mixture was incubated overnight at 4°C. The solution was then centrifuged to precipitate the protein, 1 μl of the supernatant was added to a well of a 96-well microtiter plate containing 100 μl of 100 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.0) and 2.5 nM apoHPR (Funakoshi, Tokyo, Japan), and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at 25°C. One hundred microliters of an HRP substrate, the Immobilon Western chemiluminescent HRP substrate (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany), was then added to the well, and the chemiluminescence intensity was measured using the ChemiDoc XRS system (Bio-Rad).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a Noda Institute for Scientific Research grant and in part by a grant from the Institute for Fermentation, Osaka, and a grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (17H03781).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00479-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Omidvari M, Sharifi RA, Ahmadzadeh M, Dahaji PA. 2010. Role of fluorescent pseudomonads siderophore to increase bean growth factors. J Agric Sci 2:242–247. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oppenheimer SJ. 2001. Iron and its relation to immunity and infectious disease. J Nutr 131:616S–635S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker KW, Skaar EP. 2014. Metal limitation and toxicity at the interface between host and pathogen. FEMS Microbiol Rev 38:1235–1249. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li K, Chen WH, Bruner SD. 2016. Microbial siderophore-based iron assimilation and therapeutic applications. Biometals 29:377–388. doi: 10.1007/s10534-016-9935-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schalk IJ, Hannauer M, Braud A. 2011. New roles for bacterial siderophores in metal transport and tolerance. Environ Microbiol 13:2844–2854. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas MS. 2007. Iron acquisition mechanisms of the Burkholderia cepacia complex. Biometals 20:431–452. doi: 10.1007/s10534-006-9065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornelis P, Wei Q, Andrews SC, Vinckx T. 2011. Iron homeostasis and management of oxidative stress response in bacteria. Metallomics 3:540–549. doi: 10.1039/c1mt00022e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reiter TA, Pang B, Dedon P, Demple B. 2006. Resistance to nitric oxide-induced necrosis in heme oxygenase-1 overexpressing pulmonary epithelial cells associated with decreased lipid peroxidation. J Biol Chem 281:36603–36612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602634200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Justino MC, Almeida CC, Teixeira M, Saraiva LM. 2007. Escherichia coli di-iron YtfE protein is necessary for the repair of stress-damaged iron-sulfur clusters. J Biol Chem 282:10352–10359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610656200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Troxell B, Hassan HM. 2013. Transcriptional regulation by ferric uptake regulator (Fur) in pathogenic bacteria. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 3:59. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu C, Genco CA. 2012. Fur-mediated activation of gene transcription in the human pathogen Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Bacteriol 194:1730–1742. doi: 10.1128/JB.06176-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuhara S, Komatsu H, Goto H, Ohtsubo Y, Nagata Y, Tsuda M. 2008. Pleiotropic roles of iron-responsive transcriptional regulator Fur in Burkholderia multivorans. Microbiology 154:1763–1774. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/015537-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stojiljkovic I, Hantke K. 1992. Hemin uptake system of Yersinia enterocolitica: similarities with other TonB-dependent systems in Gram-negative bacteria. EMBO J 11:4359–4367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tong Y, Guo M. 2009. Bacterial heme-transport proteins and their heme-coordination modes. Arch Biochem Biophys 481:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Runyen-Janecky LJ. 2013. Role and regulation of heme iron acquisition in Gram-negative pathogens. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 3:55. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Brian MR. 2015. Perception and homeostatic control of iron in the rhizobia and related bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 69:229–245. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choby JE, Skaar EP. 2016. Heme synthesis and acquisition in bacterial pathogens. J Mol Biol 428:3408–3428. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Payne SM, Mey AR, Wyckoff EE. 2016. Vibrio iron transport: evolutionary adaptation to life in multiple environments. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 80:69–90. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00046-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheldon JR, Laakso HA, Heinrichs DE. 2016. Iron acquisition strategies of bacterial pathogens. Microbiol Spectr 4:VMBF-0010-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brewitz HH, Hagelueken G, Imhof D. 2017. Structural and functional diversity of transient heme binding to bacterial proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 1861:683–697. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anzaldi LL, Skaar EP. 2010. Overcoming the heme paradox: heme toxicity and tolerance in bacterial pathogens. Infect Immun 78:4977–4989. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00613-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiarini L, Bevivino A, Dalmastri C, Tabacchioni S, Visca P. 2006. Burkholderia cepacia complex species: health hazards and biotechnological potential. Trends Microbiol 14:277–286. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagata Y, Senbongi J, Ishibashi Y, Sudo R, Miyakoshi M, Ohtsubo Y, Tsuda M. 2014. Identification of Burkholderia multivorans ATCC 17616 genetic determinants for fitness in soil by using signature-tagged mutagenesis. Microbiology 160:883–891. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.077057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimura A, Yuhara S, Ohtsubo Y, Nagata Y, Tsuda M. 2012. Suppression of pleiotropic phenotypes of a Burkholderia multivorans fur mutant by oxyR mutation. Microbiology 158:1284–1293. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.057372-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kvitko BH, Goodyear A, Propst KL, Dow SW, Schweizer HP. 2012. Burkholderia pseudomallei known siderophores and hemin uptake are dispensable for lethal murine melioidosis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 6:e1715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amarelle V, Koziol U, Rosconi F, Noya F, O'Brian MR, Fabiano E. 2010. A new small regulatory protein, HmuP, modulates haemin acquisition in Sinorhizobium meliloti. Microbiology 156:1873–1882. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.037713-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Escamilla-Hernandez R, O'Brian MR. 2012. HmuP is a coactivator of Irr-dependent expression of heme utilization genes in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J Bacteriol 194:3137–3143. doi: 10.1128/JB.00071-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith AD, Wilks A. 2015. Differential contributions of the outer membrane receptors PhuR and HasR to heme acquisition in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biol Chem 290:7756–7766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.633495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shirataki C, Shoji O, Terada M, Ozaki SI, Sugimoto H, Shiro Y, Watanabe Y. 2014. Inhibition of heme uptake in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by its hemophore (HasAp) bound to synthetic metal complexes. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 53:2862–2866. doi: 10.1002/anie.201307889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishimura K, Addy C, Shrestha R, Voet ARD, Zhang KYJ, Ito Y, Tame JRH. 2015. The crystal and solution structure of YdiE from Escherichia coli. Acta Crystallogr F Struct Biol Commun 71:919–924. doi: 10.1107/S2053230X15009140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Espinas NA, Kobayashi K, Takahashi S, Mochizuki N, Masuda T. 2012. Evaluation of unbound free heme in plant cells by differential acetone extraction. Plant Cell Physiol 53:1344–1354. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcs067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tyrrell J, Whelan N, Wright C, Sá-Correia I, McClean S, Thomas M, Callaghan M. 2015. Investigation of the multifaceted iron acquisition strategies of Burkholderia cenocepacia. Biometals 28:367–380. doi: 10.1007/s10534-015-9840-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwyn B, Neilands J. 1987. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal Biochem 160:47–56. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90612-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohtsubo Y, Maruyama F, Mitsui H, Nagata Y, Tsuda M. 2012. Complete genome sequence of Acidovorax sp. strain KKS102, a polychlorinated-biphenyl degrader. J Bacteriol 194:6970–6971. doi: 10.1128/JB.01848-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Datsenko K, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagayama H, Sugawara T, Endo R, Ono A, Kato H, Ohtsubo Y, Nagata Y, Tsuda M. 2015. Isolation of oxygenase genes for indigo-forming activity from an artificially polluted soil metagenome by functional screening using Pseudomonas putida strains as hosts. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 99:4453–4470. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-6322-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kishida K, Inoue K, Ohtsubo Y, Nagata Y, Tsuda M. 2017. Host range of the conjugative transfer system of IncP-9 naphthalene-catabolic plasmid NAH7 and characterization of its oriT region and relaxase. Appl Environ Microbiol 83:e02359-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohtsubo Y, Nagata Y, Tsuda M. 2017. Efficient N-tailing of blunt DNA ends by Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase. Sci Rep 7:41769. doi: 10.1038/srep41769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Green MR, Sambrook J. 2012. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 4th ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoang TT, Karkhoff-Schweizer RR, Kutchma AJ, Schweizer HP. 1998. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene 212:77–86. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kovach ME, Elzer PH, Hill DS, Robertson GT, Farris MA, Roop RM, Peterson KM. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad host range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heeb S, Itoh Y, Nishijyo T, Schnider U, Keel C, Wade J, Walsh U, O'Gara F, Haas D. 2000. Small, stable shuttle vectors based on the minimal pVS1 replicon for use in Gram-negative, plant-associated bacteria. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 13:232–237. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.2.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.