ABSTRACT

In this work we found that the bfr gene of the rhizobial species Ensifer meliloti, encoding a bacterioferritin iron storage protein, is involved in iron homeostasis and the oxidative stress response. This gene is located downstream of and overlapping the smc03787 open reading frame (ORF). No well-predicted RirA or Irr boxes were found in the region immediately upstream of the bfr gene although two presumptive RirA boxes and one presumptive Irr box were present in the putative promoter of smc03787. We demonstrate that bfr gene expression is enhanced under iron-sufficient conditions and that Irr and RirA modulate this expression. The pattern of bfr gene expression as well as the response to Irr and RirA is inversely correlated to that of smc03787. Moreover, our results suggest that the small RNA SmelC759 participates in RirA- and Irr-mediated regulation of bfr expression and that additional unknown factors are involved in iron-dependent regulation.

IMPORTANCE E. meliloti belongs to the Alphaproteobacteria, a group of bacteria that includes several species able to associate with eukaryotic hosts, from mammals to plants, in a symbiotic or pathogenic manner. Regulation of iron homeostasis in this group of bacteria differs from that found in the well-studied Gammaproteobacteria. In this work we analyzed the effect of rirA and irr mutations on bfr gene expression. We demonstrate the effect of an irr mutation on iron homeostasis in this bacterial genus. Moreover, results obtained indicate a complex regulatory circuit where multiple regulators, including RirA, Irr, the small RNA SmelC759, and still unknown factors, act in concert to balance bfr gene expression.

KEYWORDS: Sinorhizobium, bacterioferritin, iron metabolism, iron regulation

INTRODUCTION

Ensifer meliloti (formerly Sinorhizobium meliloti) 1021 is an alphaproteobacterium able to establish a symbiotic association with the leguminous plant Medicago sativa and to fix nitrogen as bacteroids within root nodules. Iron is a pivotal component in the symbiotic nitrogen fixation process as it forms part of the catalytic sites of the nitrogenase and the plant-synthesized leghemoglobin (1). Additionally, iron is an essential nutrient, and appropriate levels should be adjusted in cells in order to sustain cell life and avoid iron toxicity. To maintain iron homeostasis, bacteria have evolved a plethora of high-affinity iron acquisition, utilization, export, and storage systems. Iron storage proteins are ubiquitous factors able to sequester intracellular ferrous ions and store them in a nonreactive form. This allows cells to be protected from iron-induced formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and provides a nutritional iron source in case of starvation (2, 3).

Three types of iron storage proteins have been identified in bacteria: (i) the nonheme classical ferritin, composed of 24 subunits; (ii) the DNA binding protein from starved cells (Dps) and Dps-like proteins, which are present only in prokaryotes and are composed of 12 subunits; and (iii) the heme-containing bacterioferritin, consisting of 24 subunits and 12 Fe-protoporphyrin IX groups (4–6). Iron homeostasis is mainly achieved by strict regulation of the dedicated systems.

Expression of iron storage proteins has been found to be positively regulated by iron in Escherichia coli (7, 8), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (9), and Bradyrhizobium japonicum (10) but not in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis (11, 12). In E. coli and Pseudomonas, Fur (ferric uptake regulator) is the major iron response regulator and is involved in the regulation of iron storage protein expression (8, 9, 13). In some Alphaproteobacteria the Fur homologue has been described mainly as a manganese-responsive regulator and has been renamed Mur (14–16). In this bacterial group, iron homeostasis is handled mainly by RirA and/or Irr regulatory proteins (1). RirA (rhizobial iron regulator) is an Fe-S protein that belongs to the Rrf2 family of putative regulators. It has been identified in Rhizobium leguminosarum, but homologues have also been found in other bacterial genera belonging to the Rhizobiales order, such as Ensifer, Mesorhizobium, Agrobacterium, Brucella, and Bartonella (17). The mechanism of action of RirA has not been entirely elucidated although an iron-responsive operator (IRO) motif (TGA-N9-TCA) has been described as a putative DNA binding site for RirA (18, 19). In Bradyrhizobium and some Alphaproteobacteria, Irr has been identified as the major regulatory protein responsible for iron homeostasis. The Irr iron-responsive regulator belongs to the Fur family of proteins; however, Irr and Fur mechanisms of action are different. While Fur directly perceives intracellular Fe2+ levels, in the Bradyrhizobium genus, Irr senses iron through heme biosynthetic levels by means of a heme regulatory motif (17). Even though an irr homologue and putative Irr boxes have been identified in the E. meliloti genome, the role of Irr has not yet been determined in this bacterium.

In this study, we analyzed the role of Bfr in iron homeostasis and the oxidative stress response in E. meliloti 1021, and we provide evidence that Bfr affects the rhizobium infectivity of alfalfa plants. To gain insight into the regulation of bfr gene expression, we studied its transcriptional pattern under iron-limiting and -sufficient conditions. Moreover, we analyzed the effect that RirA, Irr, and the small RNA (sRNA) SmelC759 have on bfr expression. Results obtained lead us to propose a hypothetical model of bfr regulation in E. meliloti that is discussed further in this paper.

RESULTS

E. meliloti bacterioferritin participates in iron homeostasis.

In order to determine the role of bacterioferritin in E. meliloti 1021, total iron content was assessed by atomic absorption spectroscopy in the parental and the bfr mutant strains under iron-sufficient conditions. Iron content in the parental strain was 4.82 ± 0.06 μg Fe/mg of total cell protein, while in the bfr mutant strain the content was 4.09 ± 0.05 μg of Fe/mg total cell protein. Considering that according to our results 1 ml of an E. meliloti culture at an optical density at 620 nm (OD620) of 1 contains about 109 cells, then E. meliloti 1021 contains about 0.9 × 107 iron atoms per cell. Provided that a Bfr mutation results in a 15% decrease of total iron cell content, such a difference represents a reduction of ca. 1.3 × 106 iron atoms per cell. When cells were grown in medium supplemented with 100 μM EDDHA (ethylenediamine-di-o-hydroxyphenylacetic acid), cellular iron content was reduced more than 10 times, but no significant differences were found between the parental and the mutant strains (data not shown).

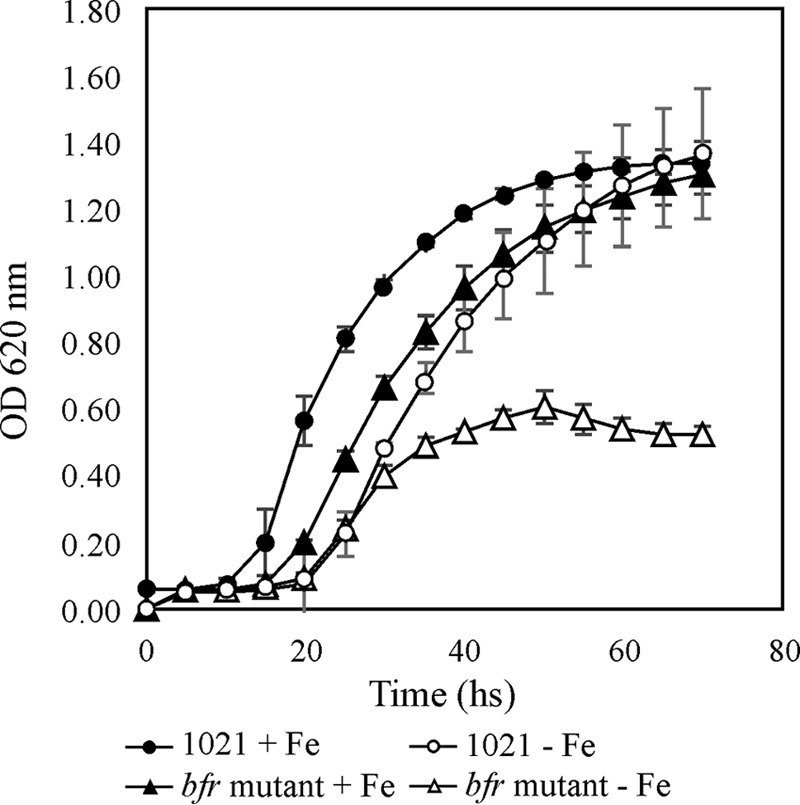

To determine if iron-loaded bacterioferritin could be used as a nutritional iron source under iron-depleted conditions, cells of E. meliloti 1021 parental and bfr mutant strains grown under iron sufficiency were transferred to either iron-limited or iron-sufficient medium, and their growth was evaluated. As shown in Fig. 1 (see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), the growth of the bfr mutant was slightly impaired under iron-sufficient conditions compared to that of the parental strain, but under iron-depleted conditions the bfr mutant growth was severely affected. To assess if growth impairment was a consequence of reduced production of rhizobactin 1021, we quantified siderophore accumulation in supernatants of the parental and the bfr mutant strains grown under iron-depleted conditions. No significant differences in production of rhizobactin 1021 were detected among strains (data not shown).

FIG 1.

Growth of the bfr mutant strain was severely impaired under iron-limited conditions. E. meliloti 1021 and the bfr::lacZ-accC1 mutant strain were grown in M9 medium supplemented with 37 μM FeCl3 (+Fe) or 100 μM EDDHA (−Fe). Error bars on each point indicate standard error for a set of 3 to 5 replicates.

Bfr is not involved in protection against iron or hemin toxicity but affects the oxidative stress response against H2O2.

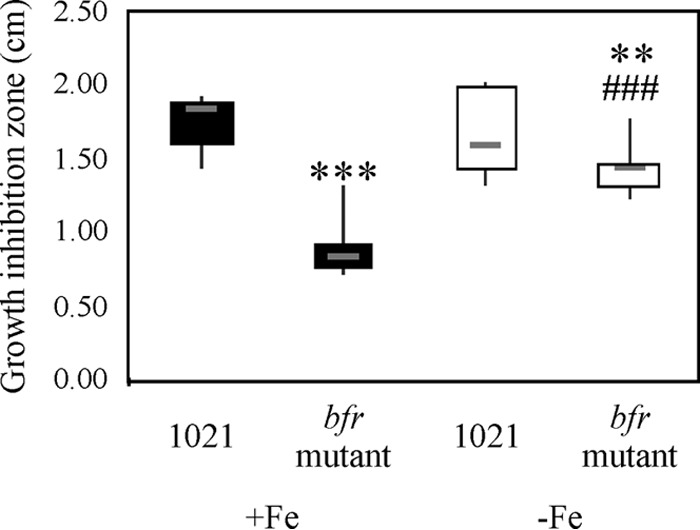

As previously mentioned, some iron storage proteins not only are involved in providing iron as a nutritional source but also may participate in protection against oxidative stress. In order to test the role of Bfr in the response to iron/hemin toxicity, the growth levels of the parental and bfr mutant strains were compared in medium containing 1 to 5 mM FeCl3 and 25 mM or 50 mM hemin. Colony sizes were significantly reduced with 5 mM FeCl3 or 50 mM hemin, but no significant differences were observed between the parental and the bfr mutant strains, suggesting that Bfr is not relevant for the iron/hemin toxicity response (data not shown). We cannot rule out the possibility that systems responsible for maintaining iron homeostasis are robust enough to prevent the intracellular iron concentration from reaching lethal levels. When the bacterial response to exogenous H2O2 was evaluated, the data obtained showed that the bfr mutant was more tolerant to H2O2 than the parental strain (Fig. 2). Moreover, differences were more striking under iron-sufficient conditions.

FIG 2.

Bfr affects the oxidative stress response against H2O2. A disc diffusion assay was performed on M3 solid medium with either 37 μM FeCl3 or 100 μM EDDHA and inoculated with E. meliloti 1021 or the bfr mutant strain. Zone of growth inhibition around paper disks containing 10 μl of 0.892 M H2O2 was determined by measuring the diameter of the clear zone around the disc. Gray hyphens correspond to medians of 18 replicates per strain per condition. A nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was applied. Significant differences are indicated as follows: ***, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.05 (both, for the difference between results with E. meliloti 1021 and the bfr mutant strain grown in iron-sufficient medium); and ###, P < 0.01, for the difference between results with E. meliloti 1021 and the bfr mutant strain grown under different iron conditions.

Symbiotic phenotype of the bfr mutant.

Alfalfa plants inoculated with the parental or the bfr mutant strain developed effective nodules, and no detectable differences in aerial plant dry weights were obtained between plants inoculated with each strain (Fig. S2). However, when the nodulation kinetics of alfalfa plants were compared, nodule formation was induced earlier in plants inoculated with the bfr mutant strain than in those inoculated with the parental strain (Fig. S3). These results indicate that the absence of Bfr affects positively the early events of E. meliloti 1021 plant infection.

The bfr gene expression is positively regulated by iron.

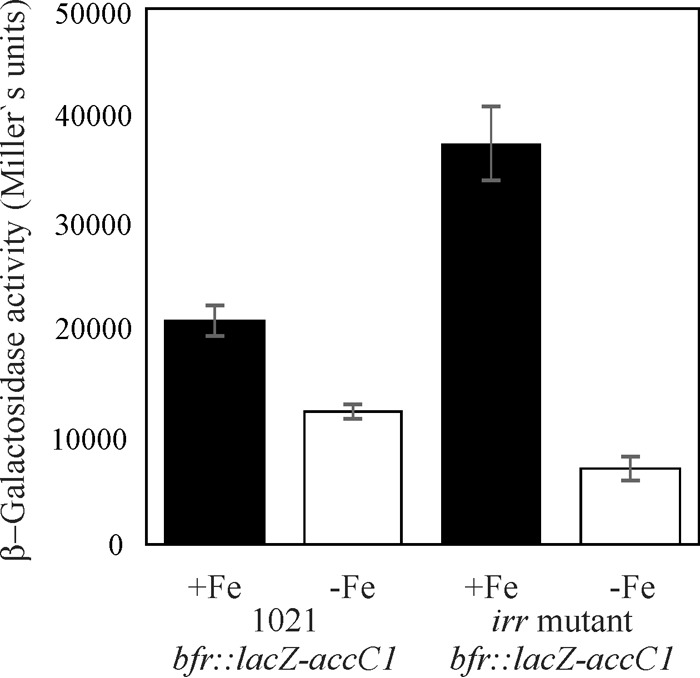

To assess iron responsiveness of bfr gene expression, a chromosomally integrated bfr::lacZ-accC1 transcriptional fusion was evaluated in E. meliloti cells grown under iron-sufficient and iron-limited conditions. As shown in Fig. 3, expression of the bfr::lacZ-accC1 fusion was detected under both conditions of iron availability; nevertheless, the activity was almost 2-fold higher in cultures grown in medium supplemented with 37 μM FeCl3, indicating that bfr gene expression is positively regulated by iron.

FIG 3.

In vivo effect of irr mutation on bfr::lacZ-accC1 activity. β-Galactosidase activity was determined in the E. meliloti 1021 bfr::lacZ-accC1 strain and in the E. meliloti irr bfr::lacZ mutant. Cultures were grown in TY medium supplemented with 37 μM FeCl3 (+Fe) or 100 μM EDDHA (−Fe). β-Galactosidase activity is expressed as Miller units. Error bars represent one standard deviation. In both strains, β-galactosidase activity was significantly higher under iron-sufficient conditions. A clear effect of irr deletion was detected, indicating an Irr role in bfr gene expression.

Irr is involved in the regulation of bfr gene expression.

In silico analysis indicates that the promoter region of smc03787, the gene upstream of bfr, contains an Irr box. Therefore, we tested whether Irr is involved in bfr expression. As shown in Fig. 3, bfr expression was upregulated in the irr-defective mutant under iron-sufficient conditions, whereas the opposite was observed under iron-depleted conditions, pointing to a role of Irr in bfr gene regulation. Data obtained by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) under iron-sufficient conditions are consistent with these results as bfr transcript levels were significantly higher in the irr mutant (Fig. 4A). According to these results, it could be hypothesized that Irr acts as a repressor of the bfr gene under iron-sufficient conditions and as an activator under iron-depleted conditions. These findings provide experimental evidence for a role of Irr in the modulation of E. meliloti gene expression. Irr seems not to be the only factor involved in regulation, as bfr gene expression still responded to iron in the irr mutant harboring the bfr::lacZ-accC1 construction (Fig. 3).

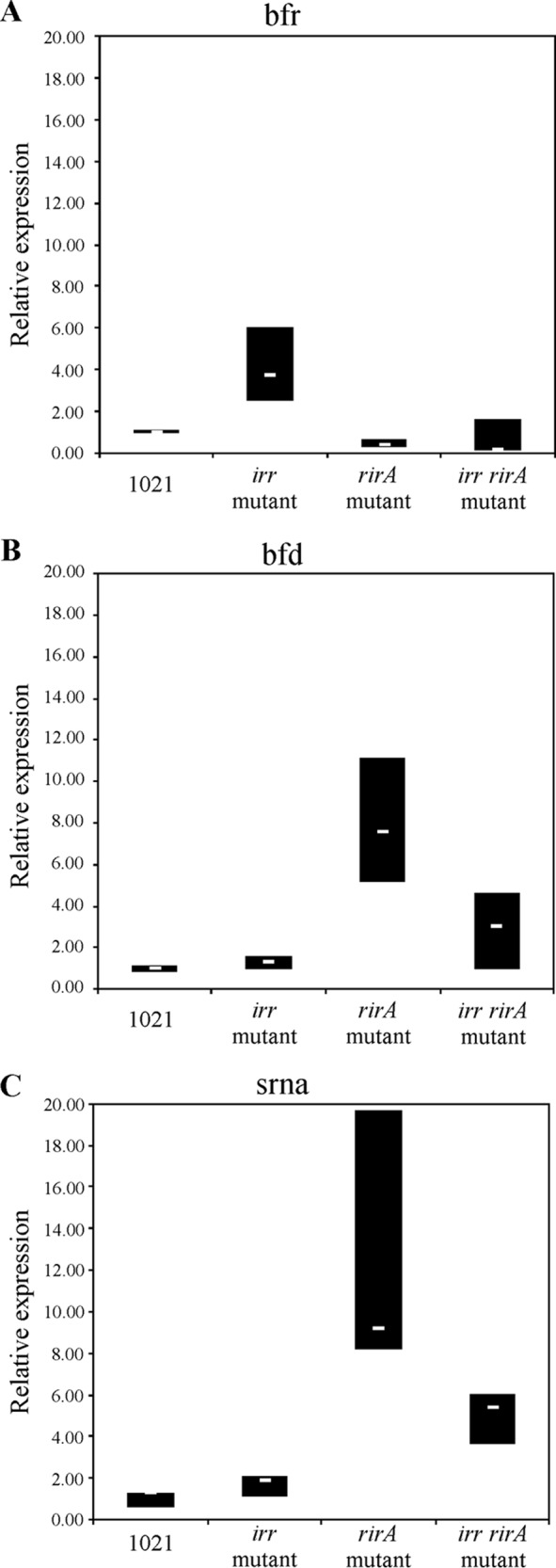

FIG 4.

Transcription of bfr and of smc03787 and smelC759 responds to Irr and RirA. Relative transcript levels, determined by qRT-PCR, under iron-sufficient conditions of bfr (A), gene smc03787, a putative bacterioferritin-associated ferredoxin gene (bfd) (B), or the sRNA gene smelC759 (C) (Fig. 5) were determined in different genomic contexts, as follows: parental strain, irr mutant, rirA mutant, and irr rirA double mutant. White hyphens inside boxes correspond to the medians, while the upper and lower limits of the boxes represent first and third quartiles, respectively.

RirA is involved in regulation of bfr gene expression.

The RirA protein has been described in E. meliloti as a repressor of iron-regulated genes under iron-sufficient conditions (15, 20). To test if this is also the case for the bfr gene, we evaluated bfr expression by qRT-PCR in an rirA knockout mutant. Contrary to our expectations, the bfr transcript level was slightly lower in the rirA mutant than in the parental strain (Fig. 4A), suggesting that RirA activates bfr expression in either a direct or an indirect manner.

These findings prompted us to determine whether the observed RirA activation is a consequence of alleviating the repressive effect of Irr under iron sufficiency. If this is the case, we would expect that in the absence of both proteins in the irr rirA double mutant, bfr gene expression would be similar to that of the irr mutant. As shown in Fig. 4A, no significant increase in bfr transcript levels could be detected in the irr rirA double mutant compared to levels in the irr mutant, indicating that the observed RirA-mediated activation of bfr gene expression is not through the alleviation of Irr repression or, at least, that this is not the only mechanism involved.

Regulation of smc03787 gene expression is inversely correlated to that of bfr.

In silico studies revealed a presumptive bfr promoter sequence upstream of the smc03787-bfr gene cluster, suggesting that smc03787 and bfr could be part of an operon. Moreover, Rodionov et al. (18) described putative RirA and Irr boxes in a region upstream of smc03787. More recently, Schlüter et al. (21) identified the location of smc03787 and bfr transcription start sites by using whole-transcriptome shotgun sequencing (RNA-seq). To assess if the region immediately upstream of bfr could contain a promoter, a 160-bp region (Fig. 5, PBfr) was cloned into the pOT1 vector upstream of a promoterless green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene, and expression was evaluated under low- and high-iron conditions. However, GFP expression could not be detected, indicating that this region has no promoter activity under the assayed conditions (data not shown).

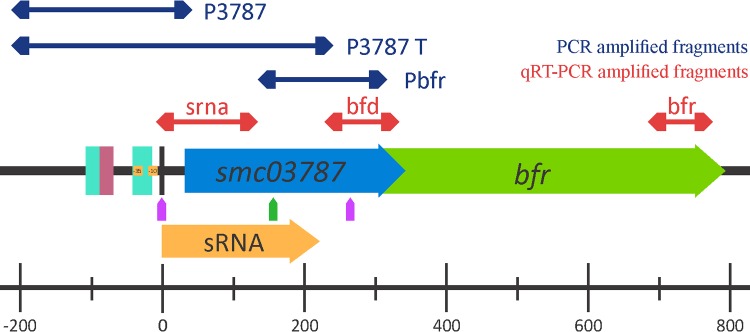

FIG 5.

Physical map of the smc03787-bfr region. The bfr gene is located on the minus strand of the E. meliloti 1021 chromosome, from position 3451466 to 3451951, partially overlapping smc03787, a gene that codifies a hypothetical conserved protein. The small RNA smelC759 was identified by Schlüter et al. (21) as partially overlapping smc03787. Positions of RirA boxes are shown in blue, and the Irr box is shown in pink. The position of transcriptional start sites identified by Schlüter et al. (21) are indicated as purple arrows. Double-headed arrows indicate the positions of the amplified fragments P3787, P3787T, PBfr, srna, bfd, and bfr and their positions are indicated under the arrows. Numbers of positions refer to the smc03787 transcriptional start site.

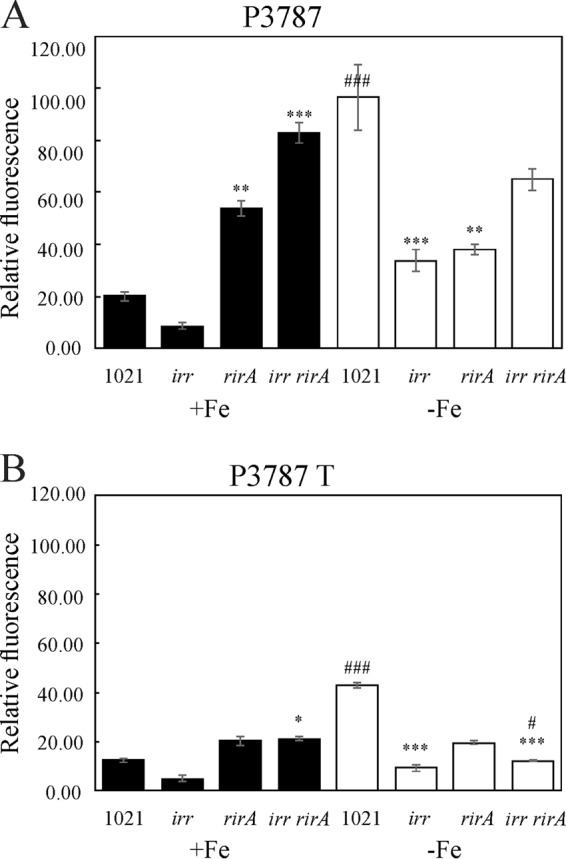

Based on these results, a 230-bp region upstream of the smc03787-bfr gene cluster (Fig. 5, P3787) was cloned into the pOT1 vector, and GFP production was assessed. As expected, negligible mean values of relative fluorescence (RF) were obtained for the E. meliloti 1021 control strain carrying the empty vector pOT1 (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 6A, E. meliloti 1021(p3787) cells grown in iron-sufficient medium showed a 5-fold reduction of promoter activity compared with that of cells grown under iron-deficient conditions, indicating that smc03787 is repressed by iron. This response was opposite to that obtained for bfr gene expression (Fig. 3 versus 6A). Moreover, when we examined the effect of single or combined irr and rirA deletions by qRT-PCR, we observed that the general response of smc03787 expression was opposite to that obtained for bfr expression (Fig. 4A versus B). A similar pattern was observed when we compared P3787 promoter activity data (Fig. 6A and S4) and bfr gene expression (Fig. 3) or bfr transcript levels (Fig. 4A). These findings strongly indicate that under iron-sufficient conditions, Irr is not a repressor of smc03787 gene expression, while rirA deletion enhances transcript levels of this gene, as expected for its classical role as an iron-responsive repressor. Interestingly, when both regulators were absent, smc03787 gene expression was still observed but to less extent than in the rirA mutant, indicating that the Irr activity occurs not only through the alleviation of RirA repression (Fig. 4B).

FIG 6.

Effect of Irr, RirA, and SmelC759 on promoter activity of smc03787 and smelC759. The relative GFP fluorescence levels in cells carrying plasmid pP3787 (A) or cells carrying plasmid pP3787T (B) are shown. The Ensifer meliloti 1021 (1021), irr mutant, rirA mutant, or irr rirA double mutant were grown in M9 medium supplemented with either 37 μM FeCl3 (solid bars) or 100 μM EDDHA (open bars). Relative fluorescence (RF) was expressed as fluorescence emission at 509 nm normalized to the OD620 in cultures at early stationary phase (ca. 48 h). Measurements were done in cultures grown in 96-well plates, and fluorescence emission and OD620 values were determined simultaneously with Varioskan equipment. Error bars indicate standard errors for five replicates. The asterisks above bars indicate a statistically significant differences relative to results with the parental strain under similar conditions of iron sufficiency, while the hash symbol (#) indicates a significant difference relative to results with the same strain under different iron conditions, according to a Kruskal-Wallis test. The number of symbols above each bar indicate the P value of the differences as follows: three symbols, P ≤ 0.01; two symbols, 0.01 ≤ P < 0.05; one symbol, 0.05 ≤ P < 0.10.

When smc03787 gene expression was evaluated in the irr rirA double mutant by qRT-PCR, values obtained were lower than expected according to the analysis of promoter activity in the E. meliloti 1021(p3787) strain (Fig. 6A), suggesting the existence of additional regulatory factors not properly reflected using the GFP reporter fusion approach.

The small RNA SmelC759 participates in the regulation of smc03787 gene expression.

Schlüter et al. (21) had previously reported the presence of a putative 224-bp cis-encoded mRNA leader, named SmelC759, partially overlapping the smc03787 gene (Fig. 5). To explore whether this noncoding RNA is linked to the expression of smc03787 and bfr genes, we evaluated the smelC759 and smc03787 transcript levels under iron-sufficient conditions (when bfr gene expression is activated). For this purpose, specific primers able to amplify the region of bp −23 to bp +72 relative to the smc03787 ORF were designed (Fig. 5). As shown in Fig. 4C, the relative expression levels of smc03787 and smelC759 were similar, as expected if they are part of the same transcriptional unit. Moreover, we found that the regulatory patterns of the smc03787 and smelC759 transcripts were alike and opposite to the pattern obtained for bfr. Subsequently, we analyzed the promoter activity of an extended 428-bp region (Fig. 5, P3787T) covering the 230-bp region of the presumptive smc03787 promoter plus the entire SmelC759 sRNA sequence. With this construction, we wanted to evaluate the effect of additional copies of the small RNA. As shown in Fig. 6B, the presence of an extended promoter region (P3787T) results in an overall reduction of promoter activity compared to that displayed by the P3787 region (Fig. 6A). This could mean either that the length of the promoter region affects RNA polymerase processivity or that there is posttranscriptional regulation that negatively affects the smc03787 transcripts. Interestingly, when promoter activity was analyzed in the irr rirA(p3787T) double mutant, containing extra copies of the SmelC759 noncoding RNA, the expression level was significantly reduced compared to that obtained with cells harboring only the P3787 region. This observation suggests that the presence of SmelC759 is required for the concerted action of RirA and Irr.

DISCUSSION

In this work we demonstrate that the E. meliloti 1021 bacterioferritin modulates cell iron content under iron-sufficient conditions and that it can be used as a nutritional iron source when iron becomes scarce. Although bacterioferritins are iron storage proteins, their role is not the same for all bacteria. For instance, in E. coli, iron content was found to be altered in the ferritin ftn mutant, where it is less abundant than in the parental strain (3). Meanwhile, cellular iron levels were not affected in a bfr mutant in this bacterium (22). In Brucella abortus, for which bacterioferritin represents the main protein responsive to iron storage, Bfr accounts for 70% of the intracellular iron pool (23). As the E. meliloti 1021 genome reveals no other genes with homology to iron storage proteins, it was conceivable that a defect in Bfr would cause a defect in the iron intracellular pool. Our data demonstrate that the bfr mutant has impaired growth compared with that of the parental strain, mainly when iron becomes scarce (Fig. 1; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), and that bfr gene expression is upregulated under iron sufficiency (Fig. 3). These results are consistent with the following model: when cells are faced with a surplus of iron, bacterioferritin abundance increases in order to store the metal in an intracellular form that can be available when the cell is required to cope with iron starvation.

According to the Fenton chemistry, in the presence of iron, H2O2 is able to produce reactive oxygen species, which is highly deleterious to cells, and it could be expected that the iron storage protein Bfr may confer protection against oxidative stress (23–25). Nonetheless, our results show that the bfr mutant is more resistant to H2O2 than the parental strain. A similar, unusual phenotype was reported for Helicobacter pylori, in which the iron storage ferritin Pfr does not protect the cell from the superoxide radical generator paraquat (26). We speculate that in the bfr mutant a reduced iron cellular content together with a putative functional iron export system cooperates to protect the cell against ROS. During the first events of the rhizobial infection process, it has been demonstrated that the leguminous plant responds by releasing H2O2 and ROS (27). In this work, we found that the bfr mutant displayed an early nodulation phenotype in M. sativa plants compared to the phenotype of the parental strain. These results reinforce the observation that the absence of bacterioferritin protects the cell, probably indirectly, against H2O2 toxicity.

Bacteria have developed multiple regulatory systems and mechanisms to sense iron and adapt to environments with changing iron availability conditions. In this regard, the RirA iron-responsive repressor (20), as well as the HmuP and RhrA transcriptional activators (28), has been identified as being involved in regulation of high-affinity iron acquisition systems in E. meliloti 1021. Here, we aimed to determine bfr gene expression and the regulatory factors involved in this strain. Our results indicate that bfr gene expression is positively regulated by iron (Fig. 3). According to Rodionov et al. (18) the smc03787 and bfr genes seem to be part of the same transcriptional unit, designated bfd-bfr, which comprises a promoter region upstream of smc03787 containing the canonical −10 and −35 promoter sequences plus two RirA boxes and one Irr box (Fig. 5). Nonetheless, Schlüter et al. (21) reported the presence of four transcriptional start sites associated with mRNAs for this region: two of them (SMc_TSS09935 and SMc_TSS09936) located upstream of smc03787 and the other two (SMc_TSS09932 and SMc_TSS09933) located immediately upstream of the bfr ORF. With this information in mind, we analyzed the promoter activity of the P3787 and the Pbfr regions (Fig. 5). Under the assayed conditions, no promoter activity was detected in the E. meliloti 1021 strain containing the plasmid construction harboring the Pbfr region. Moreover, although we demonstrated participation of Irr and RirA proteins in bfr gene regulation, no well-predicted RirA or Irr boxes were found in the region immediately upstream of the bfr gene or inside the bfr coding sequence. Currently, we do not have data to explain this behavior, but our working model is that transcription from SMc_TSS09932 or SMc_TSS09933 requires additional factors, as will be discussed further.

We demonstrated that Irr is involved in bfr gene regulation in E. meliloti, thus offering experimental proof of a biological role for the Irr protein in this bacterium. According to our results in E. meliloti under iron-sufficient conditions, Irr represses bfr gene expression whereas it activates smc03787 (Fig. 4A versus B). Concerning the role of RirA, we found that RirA activates bfr gene expression under iron-sufficient conditions but that it has a classical role as an iron-responsive repressor for smc03787 and smelC759 expression (Fig. 4B and 6A). This result agrees with the enhanced expression of smc03787 under iron-sufficient conditions in an E. meliloti rirA mutant reported by Chao et al. (15). Two RirA boxes were found in the promoter region of smc03787 and smelC759. One RirA box covers the region of bp −108 to bp −88 relative to SMc_TSS09936, immediately upstream of the Irr box, suggesting that RirA could interfere with Irr binding and vice versa. The second RirA box is located between bp −41 and bp −14 relative to SMc_TSS09936 and overlapping the region of −35 to −10 bp, thus suggesting that RirA may interfere with RNA polymerase binding and therefore with smc03787 and smelC759 transcription initiation from this transcription start site.

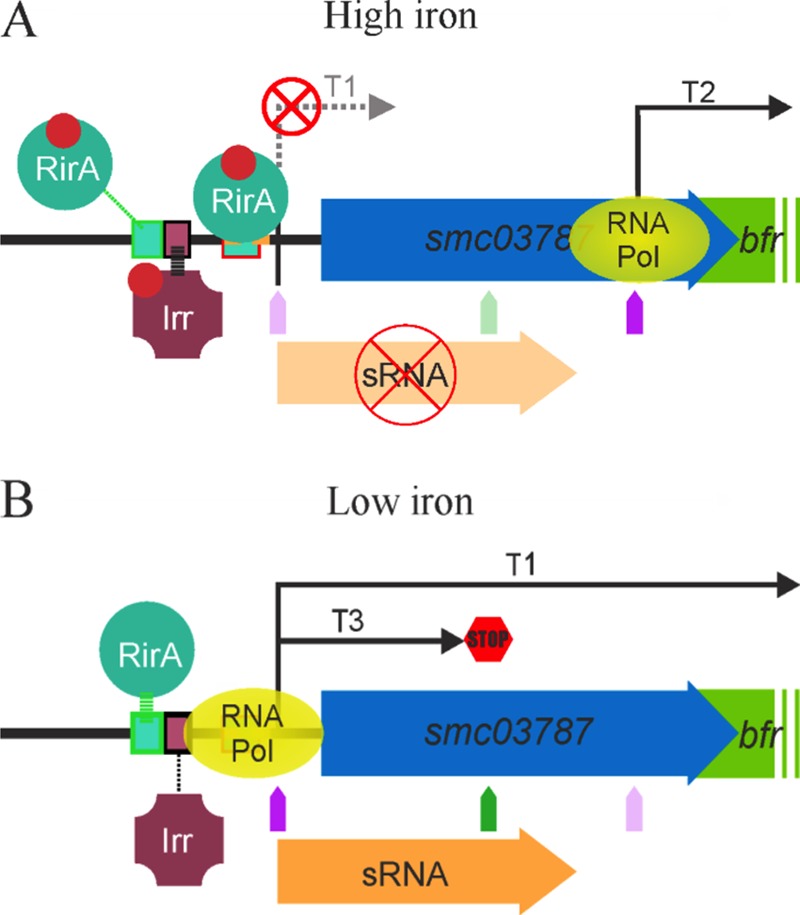

According to the data obtained through the different approaches used in this work and to previously reported results (18, 21), we propose a hypothetical model for the regulation of smc03787 and bfr gene expression (Fig. 7). We suggest the presence of at least three different transcripts. Transcript T1 starts at SMc_TSS09935 or SMc_TSS09936, giving rise to the bicistronic smc03787- or smelC759-bfr mRNA, allowing bfr gene expression. Based on our in silico analysis, we expect the presence of a “leaky terminator” (5′-GCGGCCGTTGCTGC-3′) located at +156 downstream of SMc_TSS09936. Therefore, the bfr gene could be transcribed when this leaky terminator allows transcription to proceed. Transcript T2 starts at SMc_TSS09932 or SMc_TSS09933 and allows bfr gene expression but not expression of smc03787 and smelC579. Finally, we can also expect a third transcript (T3) which also starts at SMc_TSS09935 or SMc_TSS09936, but unlike T1 it does not allow expression of either smc03787 and smelC759 or the bfr gene. According to our hypothetical model of regulation, the occupancy of the RirA box located between bp −41 and −14 relative to SMc_TSS099362 prevents smc03787 and smelC759 expression. The absence of the noncoding SmelC759 transcript allows the expression of an unknown factor facilitating T2 transcription and consequently bfr gene expression. This hypothesis is based on data showing that expression of smelC759 is inversely correlated with bfr expression (Fig. 4A versus B and C). Moreover, differences observed when we compared expression levels in cells harboring p3787T or p3787 (the former with extra copies of SmelC759 provided from the plasmid) let us speculate that this small RNA would be involved in this regulation (Fig. 6A versus B; also S4A versus S4B). In this scenario Irr would be an indirect iron-responsive repressor, and RirA would be an indirect iron-responsive activator of bfr gene expression. It is worth noting that the participation of the RNA chaperone Hfq, a major factor involved in the activity and stability of sRNAs and mRNAs (29), has been previously reported as involved in bfr gene expression in E. meliloti (30–32). Intriguingly, bfr expression is upregulated by Hfq in E. meliloti 1021 (30), while the opposite was found in the E. meliloti 2011 derivative strain (31). The reasons for this discrepancy are still unknown. Moreover, Torres-Quesada et al. (32) found that Hfq could bind, directly or indirectly, to the bfr transcript. However, to our knowledge, SmelC759 has not been identified as an Hfq-dependent sRNA. Altogether, these observations indicate that in addition to RirA, Irr, Hfq, and the small RNA SmelC759, other factors may be involved in the regulation of bfr gene expression. Under iron limitation, bfr expression is not completely repressed. Therefore, we presume that in this situation the T1 transcript is present and also that the small RNA smelC759 is present, thus allowing repression, probably indirectly, of bfr expression from T2 (Fig. 7). Certainly more information is required to validate our hypothetical model of regulation; for instance, site-directed mutagenesis over the putative Irr and RirA binding sites of the smc03787-bfr promoter could provide evidence for the molecular bases of smc03787-bfr regulation.

FIG 7.

Hypothetical model of the regulation of bfr gene expression when E. meliloti 1021 cells are grown under iron-sufficient (A) or iron-depleted (B) conditions. We postulate that under iron-sufficient conditions, transcript T2 is produced from TSS09932 or TSS09933 (A) while under iron-depleted conditions, transcript T1 is produced from TSS09935 or TSS09936. According our results, we propose that under iron-sufficient conditions, iron-loaded RirA is able to bind to the RirA box located between bp −41 and bp −14 relative to SMc_TSS099362 and repress transcription of smelC759 of smc03787 while Irr interacts with the Irr box activating the expression. A balance between RirA-mediated repression and Irr-mediated activation led to a decrease in smelC759 cellular concentration, which results in the production of T2 (A). Under iron-depleted conditions, iron-unloaded RirA is not able to bind the RirA box located between bp −41 and bp −14 relative to SMc_TSS099362, but it is able to interact with the RirA box located between bp −108 and bp −88 relative to SMc_TSS09936. Under this condition RNA polymerase is able to bind to the promoter of smelC759 or smc03787, allowing T1 or T3 production according to the effect of the leaky terminator located at the +156 position from SMc_TSS09936. Pol, polymerase.

In conclusion, in this study we demonstrated that in E. meliloti 1021, Bfr influences cellular iron content and that Bfr could be used as a nutritional iron source when iron becomes scarce. Results presented here provide novel data on the regulation of bfr expression and enabled us to propose a comprehensive hypothetical model of regulation. We demonstrate the following: (i) that regulation of the bfr gene is inversely correlated with that of smc03787 and smelC759, (ii) that bfr gene expression responds to a complex mechanism of regulation, and (iii) that at least RirA, Irr, and the small RNA SmelC759 are involved in the regulation. Moreover, our data indicate the existence of still unknown actors involved in controlling bfr gene expression in E. meliloti.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria, plasmids, and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (35). E. meliloti strains were grown at 30°C in tryptone-yeast extract (TY) medium (34), defined minimal medium M9 (35) plus 6 mM glutamate, 200 μM methionine, and 1 μM biotin (M9S), or M3 medium (36). Low-iron conditions were obtained by supplementation with 150 μM or 300 μM ethylendiamine-di-o-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (EDDHA), whereas iron-sufficient conditions were obtained by addition of 37 μM FeCl3. When required, 50 μg ml/liter kanamycin (Km), 100 μg ml/liter neomycin (Nm), 100 μg ml/liter streptomycin (Str), or 5 μg ml/liter gentamicin (Gm) was added to the medium.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strain or plasmid | Remarkable characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α | λ− ϕ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK−) supE44 thi-1 gyrA relA1 | 49 |

| Ensifer meliloti strains | ||

| 1021 | Streptomycin derivative of wild-type strain SU47 (Strr) | 50 |

| irr strain | 1021 irr::Ω (Strr Spcr) | This work |

| rirA strain | 1021 ΔrirA (Strr) | 15 |

| irr rirA strain | 1021 ΔrirA irr::Ω (Strr Spcr) | This work |

| bfr strain | 1021 bfr::lacZ-accC1 (Strr Gmr) | This work |

| bfr irr strain | 1021 bfr::lacZ-accC1 irr::Ω (Strr Gmr Spcr) | This work |

| 1021(pOT) | 1021 containing plasmid pOT1 | 51 |

| irr(pOT) strain | 1021 irr mutant containing plasmid pOT1 (Strr Gmr) | This work |

| rirA(pOT) strain | 1021 rirA mutant containing plasmid pOT1 (Strr Gmr) | This work |

| irr rirA(pOT) strain | 1021 irr rirA double mutant containing plasmid pOT1 (Strr Gmr) | This work |

| 1021(pBfr) | 1021 containing plasmid pBfr (Strr Gmr) | This work |

| 1021(p3787) | 1021 containing plasmid p3787 (Strr Gmr) | This work |

| irr(p3787) strain | 1021 irr mutant containing plasmid p3787 (Strr Gmr) | This work |

| rirA(p3787) strain | 1021 rirA mutant containing plasmid p3787 (Strr Gmr) | This work |

| irr rirA(p3787) strain | 1021 irr rirA double mutant containing plasmid p3787 (Strr Gmr) | This work |

| 1021(p3787T) | 1021 containing plasmid p3787T (Strr Gmr) | This work |

| irr(p3787T) strain | 1021 irr mutant containing plasmid p3787T (Strr Gmr) | This work |

| rirA(p3787T) strain | 1021 rirA mutant containing plasmid p3787T (Strr Gmr) | This work |

| irr rirA(p3787T) strain | 1021 irr rirA double mutant containing plasmid p3787T (Strr Gmr) | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBlueScript SK | Cloning vector (Apr) | Stratagene |

| pAB2001 | Carrying lacZ-Gmr promoter-probe cassette (Gmr Apr) | 37 |

| pΩ45 | Plasmid containing Ω Spr Strr cassette | 43 |

| pRK2013 | ColE1 replicon with RK2 tra genes; used for mobilizing incP and incQ plasmids (Kmr) | 39 |

| pOT1 | Wide-host-range GFP-UV promoter-probe plasmid, derivative of pBBR1 (Gmr) | This work |

| pBfr | pOT1 containing a putative Bfr promoter | This work |

| p3787 | pOT1 containing the P3787 promoter region | This work |

| p3787T | pOT1 containing the P3787T promoter region | This work |

Construction of a bfr mutant strain.

In order to generate a bfr mutant containing a transcriptional reporter fusion, almost the entire bfr gene was replaced by lacZ-accC. For this purpose, a 2,560-bp DNA fragment containing the bfr gene and flanking regions was amplified from the E. meliloti 1021 genome using primers 5′-GGCGCACCCCGTTTCCTTC-3′ and 5′-AGCCGCAATGCCGTCCTG-3′. The amplicon was digested with EcoRV and cloned into pBlueScriptSK (pBSK) (Stratagene) to generate plasmid pBSKbfr12. A subsequent amplification was performed using pBSKbfr12 DNA as the template and primers 5′-CAGAGCGTTGCGTATGATGGACAC-3′ and 5′-CAAGGCAGAGCGGCGTGT-3′. The 890-bp amplicon was digested using EcoRV and cloned into pBSK, obtaining pBSKbfr34. By an inverse amplification using the Pfu enzyme, a region containing 220 bp (from +66 to +286) of the bfr coding region was deleted from pBSKbfr34. The PCR product was ligated with the lacZ-accC1 cassette obtained from pAB2001 (37) and cloned in the +66 position of the bfr ORF, generating pBSK-bfr::lacZ-accC1. The bfr::lacZ-accC1 fragment was subcloned as a BamHI/HindIII insert into pK18-mob-sacB (pK18) (38) to obtain the plasmid pK18-bfr::lacZ-accC1, which was then mobilized into E. meliloti 1021 by triparental mating using E. coli DH5α(pRK2013) (39) as a helper strain. Strr and Gmr colonies able to grow in 15% (wt/vol) sucrose (Sac) were selected, and the mutation was confirmed by Southern blotting hybridization.

Cellular iron content.

Cultures grown in M3 (36) minimal medium supplemented with 37 μM FeCl3 were washed three times with 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7, and cells were freeze-dried. Iron content was determined by flame atomic absorption spectrometry in the Analytical Chemistry Laboratory of the School of Chemistry at the University of the Republic, Montevideo, Uruguay. Total protein content was evaluated with a bicinchoninic acid assay according the specifications of a Sigmas kit.

Cellular growth under different conditions of iron availability.

In order to determine the effect of iron availability on cell growth, E. meliloti 1021 and bfr mutant strains were grown in iron-sufficient minimal medium until stationary phase, washed, and subsequently subcultured in M3 or TY medium supplemented with 37 μM FeCl3, 150 μM EDDHA, or 300 μM EDDHA. The OD620 values of cultures grown in M3, M9S, or TY medium supplemented with either EDDHA or FeCl3 were monitored with a Varioskan Flash (Thermo Scientific).

Rhizobactin production.

The presence of the rhizobactin 1021 siderophore in supernatants of E. meliloti 1021 and the bfr mutant grown in M3 minimal medium supplemented with 150 μM EDDHA was evaluated with the iron perchlorate method according to Carson et al. (40).

Iron and hemin sensitivity assay.

E. meliloti 1021 and bfr mutant strains were grown in M3 medium supplemented with 37 μM FeCl3 until stationary phase. Subsequently, cells were washed, and M3 medium was added until a cell suspension at an OD620 of 1 was obtained. Afterwards, serial dilutions were performed, and 10 μM droplets were placed onto M3 solid medium supplemented with 1 mM, 2 mM, 4 mM, or 5 mM FeCl3 and on medium supplemented with 25 mM or 50 mM hemin. Cells were incubated at 30°C until colonies were visible.

Hydrogen peroxide sensitivity assay.

E. meliloti 1021 and bfr mutant strains were grown in M3 minimal medium supplemented with 37 μM FeCl3 until stationary phase. Subsequently, cells were washed and resuspended in M3 medium. In order to obtain confluent growth, 1 × 105 CFU was plated on top of M3 solid medium supplemented with either 37 μM FeCl3 or 100 μM EDDHA. Sterile filter paper disks were placed onto the solid medium, and 10-μl droplets of 0.9 M H2O2 were added to the paper disks. After 72 h of incubation at 30°C, inhibition zones around the disks were measured.

Plant growth promotion assays.

To determine the Bfr role in the establishment of plant-rhizobium symbiosis, nodule kinetics and plant growth promotion assays were performed. Medicago sativa seeds were surface sterilized with 0.2 M HgCl2 in 0.5% (vol/vol) HCl, as described by Battistoni et al. (41). The sterilized seeds were incubated for 1 h in sterile water at 30°C with shaking, and germinated on agar–0.8% (wt/vol) water in petri dishes. Seedlings were transferred aseptically to plant tubes containing 20 ml of semisolid Jensen medium (42) plus 0.8% (wt/vol) agar, without nitrogen supplementation. Seven days later, plants were inoculated with about 1 × 106 CFU of the E. meliloti parental or bfr mutant strain. Nitrogen fertilization positive controls with 1 ml of 1% (wt/vol) KNO3 and negative controls with 1 ml of sterile water were performed. A total of 10 tubes per treatment, with two plants per tube, were used. Plants were grown at 21 ± 4°C with a 16-h light period. For nodulation kinetics assays, emergence of the first nodule in each plant was registered along with time. For plant growth promotion assays, approximately 3 months after inoculation, plants were harvested, and the aerial part of each plant was heat dried for 72 h at 60°C and weighed. Dry weights of plants were compared by Tukey analysis with a P value of 0.05.

Construction of the irr mutant, the irr rirA double mutant, and the irr bfr::lacZ-accC1 double mutant.

The irr mutant strain was obtained using a strategy similar to that used for the construction of the fur mutant (14). Almost the entire irr gene, except for 20 and 40 bp at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively, was replaced by an Ω45 cassette obtained from digestion of plasmid pΩ45 (43) with SmaI. Genomic DNAs of mutants were isolated to check gene replacement by PCR. In order to obtain the irr rirA double mutant, deletion of the irr gene was transduced with the phage ϕM12 (44) to the rirA mutant strain (15). Transduction was done as previously described (44, 45). The irr bfr::lacZ-accC1 double mutant was constructed similarly to the bfr::lacZ-accC mutant but using the irr simple mutant as a parental strain.

β-Galactosidase assays.

The E. meliloti 1021 bfr::lacZ-accC1 strain and the irr bfr::lacZ-accC1 double mutant were grown for 48 h in TY medium supplemented with 37 μM FeCl3 or with 100 μM EDDHA. β-Galactosidase assays were performed according to Miller (46) with modifications described by Poole et al. (47). β-Galactosidase activity was recorded as Miller units.

Promoter transcriptional fusions.

A 230-bp fragment (Fig. 5, P3787) containing the presumptive promoter of the smc03787-bfr genes was obtained by PCR amplification using primers P3787F (5′-TTGAAGCTTGGGCGCCCCTGTGTA-3′) and P3787R (5′-TCCTCTAGATCGTCGTGTCCATCATACG-3′). An extended 428-bp-long region (P3787T) containing the presumptive promoter plus the putative smelC759 gene (Fig. 5) was obtained using primers P3787F and P3787TradR (5′-TACTCTAGACGGGCGTGATATTGC-3′). A presumptive promoter immediately upstream of the bfr gene was obtained by using primers PbfrF (5′-GTCAAGCTTATGGAAAAACGCGGCC-3′) and PbfrR (5′-ATCTCTAGACGCCCTCCGGTTTTCTTCA-3′). Recognition sequences for restriction enzymes added in each primer are underlined. DNA fragments were purified, digested with HindIII/XbaI, and cloned in the HindIII/XbaI-digested pOT1 vector (48), generating plasmids pBfr, p3787, and p3787T. Cloning was confirmed by restriction mapping and sequencing. Plasmids obtained were subsequently mobilized to the E. meliloti 1021 strain and the isogenic irr, rirA, and irr rirA mutants by triparental mating using E. coli DH5α(pRK2013) as a helper strain. The presence of transcriptional fusions in the transconjugant strains was confirmed by PCR using pOT-forward and pOT-reverse primers (48).

Expression of smc03787 and bfr.

Two different approaches were used to study regulation of bfr expression: (i) quantification of transcriptional promoter fusions to a GFP-UV reporter gene and (ii) quantitative real-time PCR assessment of transcript abundance.

For the GFP-UV reporter fusions, the promoter activity was determined by measuring emitted GFP fluorescence by spectrofluorometry or by flow cytometry in M9 broth under iron-sufficient and iron-starved conditions. Briefly, cultures of the E. meliloti 1021 strain and irr, rirA, and irr rirA mutants harboring either a pOT, p3787, p3787T, or pBfr plasmid were grown under iron-sufficient conditions until early stationary phase, washed, and diluted 100-fold in M9 medium supplemented with either 37 μM FeCl3 or 100 μM EDDHA.

For spectrofluorometric determinations, expression levels of green fluorescence (excitation wavelength [λexc], 395 nm; emission wavelength [λem], 509 nm) and the OD620 value were evaluated during cell growth in liquid medium in a Varioskan Flash (Thermo Scientific). Relative fluorescence (RF) was determined according to the method of Allaway et al. (48) and expressed as fluorescence emission at 509 nm normalized to OD620 in cultures at early stationary phase (ca. 48 h). RF produced by strains harboring fusion plasmids in each genomic context was normalized with the RF of pOT plasmid in the same genomic context. A nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis statistical test was applied in order to compare the different groups of samples.

For flow cytometry fluorescence determinations, freshly harvested cells were washed with 0.1 M sterile sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7. Cell suspensions containing about 1 × 106 cells per ml were injected in a FACSVantage (BD, USA) flow cytometer, set to emit at 488 nm and 100 mW. For quantitative real-time PCR, the E. meliloti 1021 parental strain, the irr and rirA mutants, and the irr rirA double mutant were grown in M3 medium supplemented with 37 μM FeCl3. RNA was purified using a PureLink RNA minikit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The remaining DNA was digested using 2 units of DNase I (Ambion) per μg of extracted RNA. RNA concentration was determined with a NanoDrop instrument (Thermo Scientific). A total of 100 ng of RNA was used for cDNA synthesis using an iScript Select cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) and random primers, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Expression of different regions inside the smc03787-bfr operon was quantified by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using iQ SYBR green Supermix (Bio-Rad) on a CFX96 Touch real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). Expression of an internal smelC759 region was quantified using primers srnaF (5′-TTGCGTATGATGGACACGAC-3′) and srnaR (5′-ACGATCAACTGCCAACAGTC-3′), expression of an internal region of the smc03787 gene was quantified using bfdF (5′-GGACGCCGATATATTTGATTTC-3′) and bfdR (5′-CGTCGCCTTTCAAGATCC-3′), and expression of an internal region of the bfr gene was quantified using bfrF (5′-CGATTACGTCTCGATGAAGC-3′) and bfrR (5′-CTGGCCGTATTTTTCCTCAC-3′). PCR conditions were 5 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 10 s at 95°C and 30 s at 60°C. A dissociation curve (65 to 95°C in 0.5°C increments) was carried out for all reactions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are very grateful to F. Santiñaque (flow cytometry platform of IIBCE, MEC) and A. Mallo (AA Unit, Facultad de Química, University of the Republic, Uruguay) for their helpful assistance. This work was partially supported by ANII (POS_NAC_2012_1_8635) and PEDECIBA-Química y Biología.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00895-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.O'Brian MR, Fabiano E. 2010. Mechanisms and regulation of iron homeostasis in the rhizobia. In Cornelis P, Andrews SC (ed), Iron uptake and homeostasis in microorganisms. Caister Academic Press, Poole, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison PM, Arosio P. 1996. The ferritins: molecular properties, iron storage function and cellular regulation. Biochim Biophys Acta 1275:161–203. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(96)00022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrews SC, Robinson AK, Rodríguez-Quiñones F. 2003. Bacterial iron homeostasis. FEMS Microbiol Rev 27:215–237. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00055-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrews SC. 1998. Iron storage in bacteria. Adv Microb Physiol 40:281–351. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2911(08)60134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrondo MA. 2003. Ferritins, iron uptake and storage from the bacterioferritin viewpoint. EMBO J 22:1959–1968. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yasmin S, Andrews SC, Moore GR, Le Brun NE. 2011. A new role for heme, facilitating release of iron from the bacterioferritin iron biomineral. J Biol Chem 286:3473–3483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.175034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matzanke BF, Muller GI, Bill E, Trautwein AX. 1989. Iron metabolism of Escherichia coli studied by Mossbauer spectroscopy and biochemical methods. Eur J Biochem 183:371–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb14938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massé E, Gottesman S. 2002. A small RNA regulates the expression of genes involved in iron metabolism in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:4620–4625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032066599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen S, Bleam WF, Hickey WJ. 2010. Molecular analysis of two bacterioferritin genes, bfrα and bfrβ, in the model rhizobacterium Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:5335–5343. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00215-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sankari S, O'Brian MR. 2016. Synthetic lethality of the bfr and mbfA genes reveals a functional relationship between iron storage and iron export in managing stress responses in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. PLoS One 11:e0157250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laulhère JP, Labouré AM, Van Wuytswinkel O, Gagnon J, Briat JF. 1992. Purification, characterization and function of bacterioferritin from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis P.C.C. 6803. Biochem J 281:785–793. doi: 10.1042/bj2810785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shcolnick S, Summerfield TC, Reytman L, Sherman LA, Keren N. 2009. The mechanism of iron homeostasis in the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 and its relationship to oxidative stress. Plant Physiol 150:2045–2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nandal A, Huggins CC, Woodhall MR, McHugh J, Rodriguez-Quinones F, Quail MA, Guest JR, Andrews SC. 2010. Induction of the ferritin gene (ftnA) of Escherichia coli by Fe2+-Fur is mediated by reversal of H-NS silencing and is RyhB independent. Mol Microbiol 75:637–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Platero R, Peixoto L, O'Brian MR, Fabiano E. 2004. Fur is involved in manganese-dependent regulation of mntA (sitA) expression in Sinorhizobium meliloti. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:4349–4355. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.7.4349-4355.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chao TC, Buhrmester J, Hansmeier N, Puhler A, Weidner S. 2005. Role of the regulatory gene rirA in the transcriptional response of Sinorhizobium meliloti to iron limitation. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:5969–5982. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.10.5969-5982.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diaz-Mireles E, Wexler M, Sawers G, Bellini D, Todd JD, Johnston AW. 2004. The Fur-like protein Mur of Rhizobium leguminosarum is a Mn2+-responsive transcriptional regulator. Microbiology 150:1447–1456. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26961-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Brian MR. 2015. Perception and homeostatic control of iron in the rhizobia and related bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 69:229–245. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodionov DA, Gelfand MS, Todd JD, Curson AR, Johnston AW. 2006. Computational reconstruction of iron- and manganese-responsive transcriptional networks in α-proteobacteria. PLoS Comput Biol 2:e163. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ngok-Ngam P, Ruangkiattikul N, Mahavihakanont A, Virgem SS, Sukchawalit R, Mongkolsuk S. 2009. Roles of Agrobacterium tumefaciens RirA in iron regulation, oxidative stress response, and virulence. J Bacteriol 191:2083–2090. doi: 10.1128/JB.01380-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Viguier C, O Cuiv P, Clarke P, O'Connell M. 2005. RirA is the iron response regulator of the rhizobactin 1021 biosynthesis and transport genes in Sinorhizobium meliloti 2011. FEMS Microbiol Lett 246:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schlüter JP, Reinkensmeier J, Barnett MJ, Lang C, Krol E, Giegerich R, Long SR, Becker A. 2013. Global mapping of transcription start sites and promoter motifs in the symbiotic alpha-proteobacterium Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021. BMC Genomics 14:156. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdul-Tehrani H, Hudson AJ, Chang YS, Timms AR, Hawkins C, Williams JM, Harrison PM, Guest JR, Andrews SC. 1999. Ferritin mutants of Escherichia coli are iron deficient and growth impaired, and fur mutants are iron deficient. J Bacteriol 181:1415–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Almiron MA, Ugalde RA. 2010. Iron homeostasis in Brucella abortus: the role of bacterioferritin. J Microbiol 48:668–673. doi: 10.1007/s12275-010-0145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reddy PV, Puri RV, Khera A, Tyagi AK. 2012. Iron storage proteins are essential for the survival and pathogenesis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in THP-1 macrophages and the guinea pig model of infection. J Bacteriol 194:567–575. doi: 10.1128/JB.05553-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen CY, Morse SA. 1999. Neisseria gonorrhoeae bacterioferritin: structural heterogeneity, involvement in iron storage and protection against oxidative stress. Microbiology 145:2967–2975. doi: 10.1099/00221287-145-10-2967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waidner B, Greiner S, Odenbreit S, Kavermann H, Velayudhan J, Stahler F, Guhl J, Bisse E, van Vliet AH, Andrews SC, Kusters JG, Kelly DJ, Haas R, Kist M, Bereswill S. 2002. Essential role of ferritin Pfr in Helicobacter pylori iron metabolism and gastric colonization. Infect Immun 70:3923–3929. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.7.3923-3929.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Damiani I, Pauly N, Puppo A, Brouquisse R, Boscari A. 2016. Reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide control early steps of the legume-rhizobium symbiotic interaction. Front Plant Sci 7:454. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lynch D, O'Brien J, Welch T, Clarke P, Cuiv PO, Crosa JH, O'Connell M. 2001. Genetic organization of the region encoding regulation, biosynthesis, and transport of rhizobactin 1021, a siderophore produced by Sinorhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol 183:2576–2585. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.8.2576-2585.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vogel J, Luisi BF. 2011. Hfq and its constellation of RNA. Nat Rev Microbiol 9:578–589. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barra-Bily L, Fontenelle C, Jan G, Flechard M, Trautwetter A, Pandey SP, Walker GC, Blanco C. 2010. Proteomic alterations explain phenotypic changes in Sinorhizobium meliloti lacking the RNA chaperone Hfq. J Bacteriol 192:1719–1729. doi: 10.1128/JB.01429-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sobrero P, Schluter JP, Lanner U, Schlosser A, Becker A, Valverde C. 2012. Quantitative proteomic analysis of the Hfq-regulon in Sinorhizobium meliloti 2011. PLoS One 7:e48494. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torres-Quesada O, Reinkensmeier J, Schluter JP, Robledo M, Peregrina A, Giegerich R, Toro N, Becker A, Jimenez-Zurdo JI. 2014. Genome-wide profiling of Hfq-binding RNAs uncovers extensive posttranscriptional rewiring of major stress response and symbiotic regulons in Sinorhizobium meliloti. RNA Biol 11:563–579. doi: 10.4161/rna.28239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reference deleted.

- 34.Beringer JE. 1974. R factor transfer in Rhizobium leguminosarum. J Gen Microbiol 84:188–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Battistoni F, Platero R, Duran R, Cervenansky C, Battistoni J, Arias A, Fabiano E. 2002. Identification of an iron-regulated, hemin-binding outer membrane protein in Sinorhizobium meliloti. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:5877–5881. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.12.5877-5881.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Becker A, Schmidt M, Jager W, Puhler A. 1995. New gentamicin-resistance and lacZ promoter-probe cassettes suitable for insertion mutagenesis and generation of transcriptional fusions. Gene 162:37–39. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00313-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schafer A, Tauch A, Jager W, Kalinowski J, Thierback G, Puhler A. 1994. Small mobilizable mult-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145:69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ditta G, Stanfield S, Corbin D, Helinski DR. 1980. Broad host range DNA cloning system for gram-negative bacteria: construction of a gene bank of Rhizobium meliloti. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 77:7347–7351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carson KC, Meyer J-M, Dilworth MJ. 2000. Hydroxamate siderophores of root nodule bacteria. Soil Biol Biochem 32:11–21. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(99)00107-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Battistoni F, Platero R, Noya F, Arias A, Fabiano E. 2002. Intracellular Fe content influences nodulation competitiveness of Sinorhizobium meliloti strains as inocula of alfalfa. Soil Biol Biochem 34:593–597. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(01)00215-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vincent J. 1970. A manual for the practical study of root-nodule bacteria. Blackwell, Oxford, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prentki P, Krisch HM. 1984. In vitro insertional mutagenesis with a selectable DNA fragment. Gene 29:303–313. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Finan TM, Hartweig E, LeMieux K, Bergman K, Walker GC, Signer ER. 1984. General transduction in Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol 159:120–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amarelle V, Koziol U, Rosconi F, Noya F, O'Brian MR, Fabiano E. 2010. A new small regulatory protein, HmuP, modulates haemin acquisition in Sinorhizobium meliloti. Microbiology 156:1873–1882. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.037713-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller JH. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Poole PS, Blyth A, Reid CJ, Walters K. 1994. Myo-inositol catabolism and catabolite regulation in Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae. Microbiology 140:2787–2795. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-10-2787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Allaway D, Schofield NA, Leonard ME, Gilardoni L, Finan TM, Poole PS. 2001. Use of differential fluorescence induction and optical trapping to isolate environmentally induced genes. Environ Microbiol 3:397–406. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2001.00205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hanahan D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol 166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meade HM, Long SR, Ruvkun GB, Brown SE, Ausubel FM. 1982. Physical and genetic characterization of symbiotic and auxotrophic mutants of Rhizobium meliloti induced by transposon Tn5 mutagenesis. J Bacteriol 149:114–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Platero RA, Jaureguy M, Battistoni FJ, Fabiano ER. 2003. Mutations in sitB and sitD genes affect manganese-growth requirements in Sinorhizobium meliloti. FEMS Microbiol Lett 218:65–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2003.tb11499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.