Abstract

Background

Housing instability has been associated with poor health outcomes among people who inject drugs (PWID). This study investigates the associations of local-level housing and economic conditions with homelessness among a large sample of PWID, which is an underexplored topic to date.

Methods

PWID in this cross-sectional study were recruited from 19 large cities in the USA as part of National HIV Behavioral Surveillance. PWID provided self-reported information on demographics, behaviours and life events. Homelessness was defined as residing on the street, in a shelter, in a single room occupancy hotel, or in a car or temporarily residing with friends or relatives any time in the past year. Data on county-level rental housing unaffordability and demand for assisted housing units, and ZIP code-level gentrification (eg, index of percent increases in non-Hispanic white residents, household income, gross rent from 1990 to 2009) and economic deprivation were collected from the US Census Bureau and Department of Housing and Urban Development. Multilevel models evaluated the associations of local economic and housing characteristics with homelessness.

Results

Sixty percent (5394/8992) of the participants reported homelessness in the past year. The multivariable model demonstrated that PWID living in ZIP codes with higher levels of gentrification had higher odds of homelessness in the past year (gentrification: adjusted OR=1.11, 95% CI=1.04 to 1.17).

Conclusions

Additional research is needed to determine the mechanisms through which gentrification increases homelessness among PWID to develop appropriate community-level interventions.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, EPIDEMIOLOGY, HIV & AIDS, Substance misuse

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This multilevel study addresses gaps in previous literature by investigating the relationships of ZIP code-level economic deprivation and gentrification, and county-level unaffordable rental housing and demand for assisted housing, to homelessness.

The cross-sectional design and targeted sampling strategy should be considered when interpreting the results from this study.

This is among the first empirical studies to document an association between gentrification and homelessness among a large nationwide sample of people who inject drugs.

Introduction

Safe and stable housing has been deemed a key social determinant of health by public health bodies, including the WHO and the US Department of Health and Human Services.1 2 As described by Aidala and Sumartojo, ‘unsafe and unstable housing conditions serve as the intermediary by which inequities in social and economic conditions and policies influence health’.3 Consistent with this perspective, housing remains a key structural factor targeted by global Health in All Policies approaches and domestic structural interventions (eg, Housing Opportunity for Persons with AIDS).1 4

Despite a decline in the percentage of unsheltered homeless people in the USA from 40% to 31% between 2007 and 2014, a recent study by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) reported that on a single night in 2014, more than 578 000 people experienced homelessness.5 This suggests that the USA is far from attaining its goal of ending homelessness.

People who inject drugs (PWID) are particularly vulnerable to homelessness.6–14 Homelessness among PWID has dire consequences for their health. Homelessness has been associated with relapse among former injectors,8 15 16 and among former and active injectors, homelessness has been associated with injection and sexual risk behaviours8 10 14 17–20; the transmission of infectious diseases;13 opiate overdose21 and lower rates of drug treatment enrollment and retention,18 22–24 drug cessation15 16 25 and antiretroviral adherence among those who are HIV positive.26

Evaluations of ‘Housing First’ interventions further support the importance of stable housing among PWID.17 27 28 These interventions provide housing to unstably housed individuals without requiring the participants to first engage in drug abuse or mental health treatment. Although most of these evaluations have not been conducted exclusively among PWID, those conducted among individuals with co-occurring disorders (eg, mental illness and substance use) suggest that Housing First interventions improve housing stability, drug abuse treatment retention,27 health behaviours and health outcomes.17 28

The determinants of homelessness that have been identified among PWID and other populations in previous literature have largely been individual-level characteristics, including sociodemographic factors, mental health status, history of substance use and HIV status, and social network characteristics.9 17 29 30 With the exception of qualitative research,18 31 most research has not explored the potential influence of local place-based factors on homelessness.

Homelessness has been hypothesised to result from several place-based factors, including unaffordable housing and economic deprivation. Homelessness has also been hypothesised to be a consequence of urban redevelopment and gentrification processes that may cause landlords to intentionally disinvest in maintenance and repair of properties that ultimately get repurposed or demolished and thereby reduce available affordable housing stock.32–36 Similarly, the demolition of public housing complexes that occurred under the Housing Opportunities for People Everywhere policy in several US cities may have contributed to the loss of affordable housing stock. Urban redevelopment and gentrification may also reduce affordable housing stock by increasing rent and housing market value, increasing demand for supportive housing and housing subsidies (eg, Section-8 vouchers) and potentially causing the needs of marginalised groups to go unmet.32–35 37–42

Empirical data are lacking, however, on the extent to which place-based factors relate to homelessness. A study conducted among shelter residents in Philadelphia and New York City is one of the few studies that have explored this line of research. It demonstrated that the majority of shelter residents reported prior addresses that were located in economically deprived neighbourhoods.43

The current study provides a rare opportunity to further advance knowledge about the possible impacts of place-based factors on homelessness among PWID, by linking individual-level data on homelessness among a large community-based sample of PWID to administrative data on economic and housing conditions at ZIP code and county geographical levels. Increasing empirical evidence of the potential role of place-based factors on homelessness—above and beyond individual-level factors—may suggest potential structural interventions that should be implemented and reduce social stigma.44

Methods

National HIV Behavioral Surveillance study sample

PWID were recruited by respondent-driven sampling (RDS) for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2009 National HIV Behavioral Surveillance (NHBS). NHBS sampling procedures have been described elsewhere.45 Briefly, its 2009 PWID surveillance cycle was implemented in 20 metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) with high AIDS prevalence in 2006.46 Eligible participants included those who had not already participated in the 2009 cycle of NHBS, were ≥18 years, reported injection drug use in the past year, demonstrated evidence of injection (eg, track marks); resided in an NHBS-eligible MSA and provided oral consent. Participants enrolled at the San Juan–Bayamon site were excluded because administrative data on several place-based characteristics were not available for this MSA. A total of 9882 participants met the eligibility criteria in the remaining 19 MSAs.

Analysis was restricted to 9702 PWID who self-identified as Hispanic/Latino, non-Hispanic/Latino black and non-Hispanic/Latino white.47 Participants were excluded from the analytic sample if they had invalid/incomplete surveys (n=26), had invalid or missing ZIP code information (n=499), were transgender individuals who comprise too small a category to be analysed (n=51) or were missing information on key covariates (n=134). The final analytic sample included 8992 participants. Those excluded from the analysis were more likely to be white (>10% difference) and live in the Western region of the USA and less likely to live in the Midwestern region than those included in the analytic sample. Other characteristics measured in this study were not substantially different (>10%) between those included and excluded from the analysis.

Data collection and measures

Trained interviewers collected self-reported individual-level data on PWID, including demographics, behaviours, life events and ZIP codes and counties where they resided using standardised questionnaires. Participants were assigned to MSAs and regions based on interview site. When possible, participants who reported homelessness at the time of their interview were assigned to the ZIP code where they reported they frequently slept. When participants lived in ZIP codes that crossed county lines, they were assigned to the county where most participants living in that ZIP code reported residing (n=341).

Individual-level homelessness was defined as self-reported homelessness; residing on the street, in a shelter, in a single room occupancy hotel or in a car or temporarily residing with friends or relatives at any time in the past 12 months.

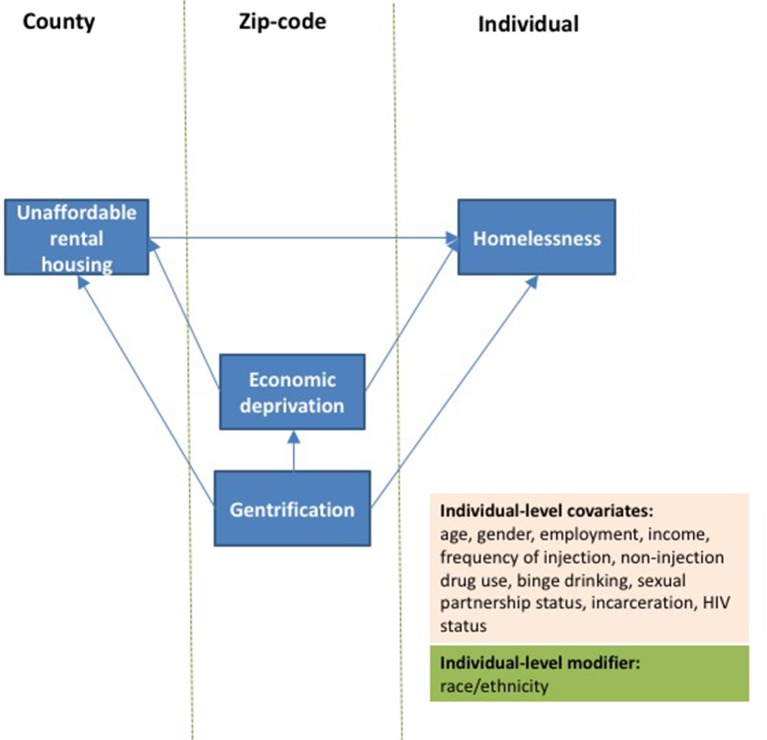

ZIP code-level and county-level factors were selected based on the conceptual framework presented (figure 1).8 9 17 29 30 33 37–41 43 48 Definitions and sources of these factors are detailed in table 1. Factors were created using data from the 2009 HUD Picture of Subsidized Households and US Census Bureau’s 1990 Decennial Census and 2007–2011 American Community Survey (ACS). County-level factors were percent unaffordable rental units49 among low-income households and average number of months that applicants were on waiting lists for assisted housing. ZIP code-level factors were economic deprivation50 51 and gentrification38 40 52 53 between 1990 and 2009.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework linking local economic and housing factors to homelessness among people who inject drugs.8 9 17 29 30 33 37–41 43 48

Table 1.

Definition and sources of place-based exposures

| Place-based exposures | Measure | Source |

| County | ||

| Percent unaffordable rental units among low- income households | Among households earning <US$10 000 annually, the number of occupied rental units* where residents spent ≥35% of their annual household income on rent, divided by the total number of occupied rental units | 2007–2011 American Community Survey |

| Average number of months that applicants were on waiting lists for assisted housing | Average months on waiting lists among new admissions for housing programs assisted by the Department of Housing and Urban Development | 2009 Picture of Subsidised Households, Department of Housing and Urban Development |

| ZIP code | ||

| Economic deprivation† | Index of % residents employed in low-wage occupations (eg, service, sales, construction, manufacturing, transportation), % households in poverty, % female-headed households with dependent children <18 years, % households on public assistance, % low-income households, % without high school diploma/General Educational Development Diploma (GED) and % unemployed | 2007–2011 American Community Survey |

| Gentrification‡ | Index of percent change in the following indicators between 1990 and 2009: % poverty, % college or more among adults aged ≥25, % White, median household income and median monthly rent. Economic factors were adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index. | Geolytics 1990 Long Form in 2010 Boundaries; 2007–2011 American Community Survey |

*The US Census Bureau defines housing units to be a house, an apartment, a mobile home or trailer, a group of rooms or a single room that is occupied. Group quarters (eg, treatment centres, correctional facilities and homeless shelters) are not defined as housing units.49.

†The economic deprivation index was informed by50 51: Principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted to confirm the dimensionality of the items across ZIP codes of all metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs). Once confirmed through PCA, the items were standardised by z-score, weighted by factor loadings and summed to create the index.

‡The gentrification measure was informed by38 40 52 53; PCA was conducted to confirm the dimensionality of the items across ZIP codes of all MSAs. Once confirmed through PCA, the items were standardised by z-score, weighted by factor loadings and summed to create the index.

Individual-level covariates were also selected based on previous research8 9 17 29 30 33 37–41 43 48and included age, gender, race and ethnicity, full-time employment and self-reported HIV status (ie, indeterminate/unknown, negative, positive) at the time of the interview, personal annual income dichotomized at the median (>US$5000 vs ≤US$5000), daily injection, binge drinking, non-injection drug use, having a main or casual sexual partner in the past year, and incarceration (ie, held in a jail or prison for at least 1 day in the past year). Measures of poor mental health status, which are well-established predictors of homelessness, were not collected as part of NHBS.

Statistical analysis

The distributions of all characteristics were determined using descriptive statistics (ie, frequencies and percentages and means and SD). To prevent possible multicollinearity, the correlations between place-based characteristics were assessed. Univariate and multivariable multilevel logistic regression models were used to assess relationships of place-based factors to the odds of homelessness. Random intercepts were included for ZIP codes, counties and MSAs. A multivariable model assessed the relationships of place-based factors significant at p<0.20 in univariate models to homelessness, controlling for individual-level covariates. We also explored whether the relationships of place-based factors to homelessness differed among Latino, black and white participants through stratified analysis using Stata V.13 (StataCorp).

Results

Place characteristics

On average, participants resided in counties where 85.18% (SD=6.15) of rental units among low-income households were unaffordable, and the average number of months that applicants were on waiting lists for assisted housing was 30.03 months (SD=17.65; table 2). The mean gentrification score was 0.41 (SD=1.45) among the ZIP codes where participants lived. On average, ZIP codes that scored above the mean were characterised by a 53% increase in percent of non-Hispanic white residents between 1990 and 2009 and a 20% increase in median gross rent and median household income (adjusted for inflation) between 1990 and 2009.

Table 2.

Distributions of ZIP code, county and participant characteristics among 8992 people who inject drugs living in 19 US metro areas in 2009

| Characteristics |

Total

n (%) or mean (SD) |

| n=8992 | |

| Region* | |

| Northeast | 2116 (23.53) |

| South | 3598 (40.01) |

| Midwest | 938 (10.43) |

| West | 2340 (26.02) |

| MSA (n=19) | |

| County (n=51) | |

| Percent unaffordable rental units among low-income households | 85.18 (6.87) |

| Average number of months that applicants were on waiting lists for assisted housing | 30.03 (17.65) |

| ZIP code (n=939) | |

| Economic deprivation | 2.28 (2.23) |

| Gentrification | 0.41 (1.45) |

| Participant characteristics | |

| Current age | 45.76 (10.54) |

| Male | 6450 (71.73) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Latino | 1622 (18.04) |

| Black | 4662 (51.85) |

| White | 2708 (30.12) |

| Annual income (≤US$5000) | 5488 (61.03) |

| Full-time employment | 394 (4.38) |

| Incarceration | 3281 (36.50) |

| Homelessness | 5394 (59.99) |

| Daily injection | 2310 (25.69) |

| Binge drinking | 4939 (54.93) |

| Type of sexual partner in the past 12 months | |

| Main | 4454 (49.53) |

| Casual | 4370 (48.60) |

| Non-injection drug use | 6765 (75.23) |

| Recent HIV test result | |

| Negative result on most recent HIV test | 6986 (77.69) |

| Positive result on most recent HIV test | 495 (5.50) |

*The Northeast region includes the metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) of Boston, Massachusetts; Nassau-Suffolk, New York; New York, New York; Newark, New Jersey; and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Southern region includes Atlanta, Georgia; Baltimore, Maryland; Dallas, Texas; Houston, Texas; Miami, Florida; New Orleans, Louisiana; and District of Columbia. Midwest region includes Chicago, Illinois and Detroit, Michigan. Western region includes Denver, Colorado; Los Angeles, California; San Diego, California; San Francisco, California; and Seattle, Washington.

Participant characteristics

The majority of participants were black (52%) and men (72%;- table 2). The mean age of the participants was 45.76 years (SD=10.54). Less than 5% of participants reported current full-time employment at the time of the interview and 61% earned an annual personal income of US$5000 or less. Sixty percent of the participants reported experiencing homelessness at some point during the last year.

Associations of place characteristics with homelessness among PWID

In univariate models (table 3), PWID who lived in ZIP codes with higher levels of gentrification had a significantly higher odds of homelessness in the past year (OR=1.13; 95% CI=1.07 to 1.18). PWID who lived in counties with greater percentages of unaffordable rental housing units among low-income households were less likely to report homelessness in the past year; this association was marginally significant (OR=0.97; 95% CI=0.94 to 1.01; p=0.110). These associations did not substantially differ in magnitude and significance across different racial/ethnic groups of PWID (data not shown).

Table 3.

Association of ZIP code, county and participant characteristics with recent homelessness among people who inject drugs from 19 US metro areas in 2009

| Univariate model OR (95% CI) |

Multivariable model adjusted OR (95% CI)* |

|

| Intercept | 19.58 (1.13 to 339.80) | |

| Region | ||

| Northeast (reference) | 1.00 | |

| South | 1.19 (0.73 to 1.93) | — |

| Midwest | 0.71 (0.33 to 1.55) | — |

| West | 1.33 (0.77 to 2.28) | — |

| Metropolitan statistical area (n=19) | ||

| Random intercept variance | 0.06 (0 to 2.61) | 0.06 (0 to 2.00) |

| County (n=51) | ||

| Random intercept variance | 0.26 (0.10 to 0.70) | 0.21 (0.07 to 0.69) |

| Percent unaffordable rental units among low-income households | 0.97 (0.94 to 1.01) | 0.99 (0.96 to 1.02) |

| Average number of months that applicants were on waiting lists for assisted housing | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.01) | — |

| ZIP code (n=937) | ||

| Random intercept variance | 0.31 (0.23 to 0.43) | 0.17 (0.11 to 0.26) |

| Economic deprivation | 0.98 (0.95 to 1.02) | |

| Gentrification | 1.13 (1.07 to 1.18) | 1.11 (1.04 to 1.17) |

| Participant characteristics |

||

| Current age | 0.97 (0.96 to 0.97) | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.98) |

| Sex (1=male) | 0.88 (0.80 to 0.98) | 0.81 (0.73 to 0.91) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Black | 0.66 (0.58 to 0.75) | 0.76 (0.66 to 0.87) |

| Latino | 0.87 (0.75 to 1.01) | 0.83 (0.71 to 0.97) |

| Annual income (US$5000 vs more) | 0.48 (0.44 to 0.53) | 0.48 (0.44 to 0.53) |

| Full-time employment | 0.34 (0.27 to 0.42) | 0.38 (0.30 to 0.49) |

| Incarceration | 2.19 (1.98 to 2.42) | 1.84 (1.65 to 2.05) |

| Daily injection (vs less than daily) | 1.23 (1.10 to 1.37) | 1.18 (1.04 to 1.32) |

| Binge drinking | 1.51 (1.38 to 1.66) | 1.30 (1.18 to 1.44) |

| Non-injection drug use | 1.41 (1.27 to 1.57) | 1.23 (1.10 to 1.37) |

| Type of sexual partner in the past 12 months | ||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Main | 1.15 (0.82 to 1.60) | 1.14 (0.81 to 1.60) |

| Casual | 2.10 (1.91 to 2.31) | 1.76 (1.60 to 1.95) |

| Recent self-reported HIV test result | ||

| Indeterminate result/or did not receive result (reference) |

1.00 | 1.00 |

| Negative result | 0.78 (0.69 to 0.88) | 0.86 (0.76 to 0.99) |

| Positive result | 0.49 (0.39 to 0.62) | 0.63 (0.50 to 0.80) |

*The multivariable model assessed the relationships of place-based factors significant at p<0.20 in univariate models to homelessness, controlling for individual-level confounders.

In the multivariable model, ZIP code-level gentrification remained significantly associated with homelessness (table 3: adjusted OR=1.11; 95% CI=1.04 to 1.17). Specifically, the odds of homelessness increased by 17% with each SD increase in ZIP code-level gentrification. The association between percentages of unaffordable rental housing units among low-income households and homelessness was no longer marginally significant (adjusted OR=0.99; CI=0.96 to 1.02).

Discussion

A high level of homelessness (60% in last year) was reported among this large sample of PWID, which not only highlights PWID’s vulnerability to poor health outcomes but also raises concerns about the potential high societal costs that may result from homelessness, including increased healthcare costs.54 To our knowledge, this is among the first studies to empirically reveal relationships of local economic and housing stock characteristics to homelessness among PWID. Specifically, this study discovered a significant association between ZIP code-level gentrification from 1990 to 2009 and homelessness among PWID; this relationship did not vary across racial/ethnic groups. Because empirical investigations of the potential role of local economic and housing conditions on homelessness among the general population have been limited,43 this paper also makes a new contribution to the larger body of research focused on homelessness and health.

The relationship between gentrification and homelessness in this analysis is supported by previous qualitative studies with predominantly low-income and racial/ethnic minority residents, which suggests that living in gentrifying areas can increase housing instability.31 33 38–41 These studies report a combination of pathways through which gentrification can increase housing instability. Gentrification is a change in the socioeconomic character of a community that is largely accompanied by stark inflations of rental costs and property taxes.33 38 39 Housing markets of gentrifying areas may further be changed by direct demolition or repurposing of low-income and affordable housing units into mixed-income and mixed-use development,31–33 38–41 55 56 a process that was widely implemented by federally funded public housing demolitions in several US cities (eg, Housing Opportunities for People Everywhere).31 57

Abrupt changes to the housing market in these ways can increase the demand for affordable housing, shelters and other safety-net services among low- to moderate-income residents who cannot afford inflated costs of living in gentrifying areas. As a result, the needs of the most marginalized and low-income groups, including PWID, may go unmet.31 42 55 56 This is particularly concerning, given increasing rates of gentrification in several cities across the USA,58 including those sampled in this study.

Contrary to previous conceptual frameworks and hypotheses, we did not observe a statistically significant association between unaffordable housing and homelessness in this study. These findings, however, may not challenge the importance of increasing access to affordable housing and the potential positive health consequences that may result from such efforts. Because the US Census Bureau’s ACS does not provide publicly available data on low-income households spending more than 35% of their income on housing, we could not explore the potential impact of a higher threshold of affordability. Higher thresholds of 50% or more of income allocated to housing costs have been proposed by housing policy researchers to better measure the burden of housing-related costs among predominantly low-income populations.59 The measure of assisted housing units that we used in this study is also limited and may not accurately reflect demand for subsidised housing. In many cities, waiting lists for subsidized housing are closed to applicants at specific thresholds and thus exclude the waiting times of those who could not apply.

It is plausible that factors not measured in this study may partly contribute to the relationship between gentrification and homelessness. Previous research demonstrates that gentrification and its common antecedent—urban redevelopment—are associated with reductions in crime.33 60 61 These reductions may result from increases in law enforcement strategies that aim to prevent drug-related offences and other ‘public nuisances’ that might slow redevelopment and gentrification processes.32–34 42 Perceived crime and political capital among new residents may further increase law enforcement activities in gentrifying areas. Previous studies suggest that (more affluent) residents moving into gentrifying areas often have greater political power than (predominantly low-income and racial/ethnic minority) long-term residents and are thereby more empowered in advocating for increased law enforcement52 62 63 Together, these circumstances can increase arrests of people who possess and use substances, including PWID, and thereby increase their vulnerability to homelessness.8 64

Limitations

This study is cross-sectional, so temporal associations that might be observed in longitudinal analysis may go undetected, and causal interpretations cannot be made. The cross-sectional design also limits exploration of potential displacement of homeless participants as a result of gentrification. Previous studies have revealed links between gentrification, crime reduction efforts and the displacement of homeless people and homeless services.31 32 Additionally, findings may not be generalizable to PWID living outside of the MSAs captured by NHBS, and the extent to which RDS generated a representative sample in this study cannot be confirmed.65

We did not account for clustering of observations within RDS chains because of the large number of intercepts required for cross-classified multilevel modelling. We adjusted for place and sociodemographic factors, however, which may have partially controlled for intra-chain clustering.66 67 Additionally, we could not distinguish different types or durations of homelessness among participants in this study because these characteristics are not collected by NHBS.

Lastly, ZIP codes were the smallest geographic unit used to describe areas where participants resided. ZIP codes may not adequately capture smaller boundaries within which housing and economic factors are most relevant to housing stability among PWID.

Conclusion

Homelessness has been associated with the transmission of HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C (HCV) and lower levels of drug cessation among PWID and high societal costs. Identifying place-level predictors of homelessness can suggest changes in policy that can prevent these negative consequences. This study demonstrated a relationship between gentrification and homelessness among PWID. Future longitudinal studies should explore whether these associations are causal and identify potential mediators. Because this area of research has been underexplored among the general population, future research should include broader samples of residents. Growth in this line of research can inform urban planning strategies and community mobilisation campaigns that are designed to curb the potential negative effects of gentrification by strengthening access to stable and permanent housing among low-income and marginalised populations.

bmjopen-2016-013823supp001.doc (85KB, doc)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Ceners for Disease Control and Prevention and the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System Study Group—Atlanta, Georgia: Jennifer Taussig, Shacara Johnson and Jeff Todd; Baltimore, Maryland: Colin Flynn and Danielle German; Boston, Massachusetts: Debbie Isenberg, Maura Driscoll and Elizabeth Hurwitz; Chicago, Illinois: Nikhil Prachand and Nanette Benbow; Dallas, Texas: Sharon Melville, Richard Yeager, Jim Dyer and Alicia Novoa; Denver, Colorado: Mark Thrun and Alia Al-Tayyib; Detroit, Michigan: Emily Higgins, Eve Mokotoff and Vivian Griffin; Houston, Texas: Aaron Sayegh, Jan Risser and Hafeez Rehman; Los Angeles, California: Trista Bingham and Ekow Kwa Sey; Miami, Florida: Lisa Metsch, David Forrest, Dano Beck and Gabriel Cardenas; Nassau-Suffolk, New York: Chris Nemeth, Lou Smith and Carol-Ann Watson; New Orleans, Louisiana: William T Robinson, DeAnn Gruber and Narquis Barak; New York City, New York: Alan Neaigus, Samuel Jenness, Travis Wendel, Camila Gelpi-Acosta and Holly Hagan; Newark, New Jersey: Henry Godette, Barbara Bolden and Sally D’Errico; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Kathleen A Brady, Althea Kirkland and Mark Shpaner; San Diego, California: Vanessa Miguelino-Keasling and Al Velasco; San Francisco, California: H Fisher Raymond; San Juan, Puerto Rico: Sandra Miranda De Leo´n and Yadira Rolo´n-Colo´n; Seattle, Washington: Maria Courogen, Hanne Thiede and Richard Burt; St Louis, Missouri: Michael Herbert, Yelena Friedberg, Dale Wrigley and Jacob Fisher; Washington, DC: Marie Sansone, Tiffany West-Ojo, Manya Magnus and Irene Kuo; and Behavioral Surveillance Team. We also thank the men and women who participated in NHBS and the staff at all NHBS sites.

Footnotes

Contributors: SLL and HLFC conceptualized this analysis. SLL constructed and compiled place-level data, designed and conducted the analysis, and interpreted the analysis and results. MEK and HLFC provided input on the analytic plan. MEK, CCK, ZR and MEW contributed to interpreting the geographical data, and SS, ED, CS, CW and GP-B planned, designed and oversaw data collection for NHBS in collaboration with project site directors. SLL, HLFC, MEK, CCK, ZR, MEW, SRF, DDJ, SS, BT, CS, ED, CW, GP-B contributed to revising and finalizing the manuscript.

Funding: This research was supported by two grants from the National Institutes of Health: “Place Characteristics & Disparities in HIV in IDUS: A Multilevel Analysis of NHBS” (R01DA035101; Cooper, PI) and the Emory Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI050409;Curran, PI).

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description/these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Ethics approval: The Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) of Emory University and each NHBS site and the CDC approved study protocols.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System data are available from the CDC. Due to ethical restrictions regarding potentially identifiable information, place-based data are available upon request. Requests for all data may be sent to Gabriela Paz-Bailey, MD, PhD, MSc (Team Lead for the Behavioral Surveillance Team, BCSB/DHAP/NCHHSTP/CDC) at gmb5@cdc.gov.

References

- 1. Housing: shared interests in health and development. Social Determinants of Health Sectoral Briefing Series 1. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives for 2020. Healthy People 2020: An Opportunity to Address the Societal Determinants of Health in the United States. 2010. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2010/hp2020/advisory/SocietalDeterminantsHealth.htm (accessed 14 Apr 2016).

- 3. Aidala AA, Sumartojo E. Why housing? AIDS Behav 2007;11:1–6. 10.1007/s10461-007-9302-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD?src=/program_offices/comm_planning/aidshousing (accessed 14 Apr 2016).

- 5. The 2014 annual homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. Washington, DC: U.S: U.S: Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mizuno Y, Purcell D, Borkowski TM, et al. The life priorities of HIV-seropositive injection drug users: findings from a community-based sample. AIDS Behav 2003;7:395–403. 10.1023/B:AIBE.0000004731.94734.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aidala AA, Lee G, Abramson DM, et al. Housing need, housing assistance, and connection to HIV medical care. AIDS Behav 2007;11:101–15. 10.1007/s10461-007-9276-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Linton SL, Celentano DD, Kirk GD, et al. The longitudinal association between homelessness, injection drug use, and injection-related risk behavior among persons with a history of injection drug use in Baltimore, MD. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;132:457–65. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Song JY, Safaeian M, Strathdee SA, et al. The prevalence of homelessness among injection drug users with and without HIV infection. J Urban Health 2000;77:678–87. 10.1007/BF02344031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. DeBeck K, Small W, Wood E, et al. Public injecting among a cohort of injecting drug users in Vancouver, Canada. J Epidemiol Community Health 2009;63:81–6. 10.1136/jech.2007.069013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Krüsi A, Fast D, Small W, et al. Social and structural barriers to housing among street-involved youth who use illicit drugs. Health Soc Care Community 2010;18:282–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2009.00901.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Palepu A, Marshall BD, Lai C, et al. Addiction treatment and stable housing among a cohort of injection drug users. PLoS One 2010;5:e11697 10.1371/journal.pone.0011697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim C, Kerr T, Li K, et al. Unstable housing and hepatitis C incidence among injection drug users in a canadian setting. BMC Public Health 2009;9:270 10.1186/1471-2458-9-270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bluthenthal RN, Do DP, Finch B, et al. Community characteristics associated with HIV risk among injection drug users in the San Francisco Bay Area: a multilevel analysis. J Urban Health 2007;84:653–66. 10.1007/s11524-007-9213-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shah NG, Galai N, Celentano DD, et al. Longitudinal predictors of injection cessation and subsequent relapse among a cohort of injection drug users in Baltimore, MD, 1988-2000. Drug Alcohol Depend 2006;83:147–56. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mehta SH, Sudarshi D, Srikrishnan AK, et al. Factors associated with injection cessation, relapse and initiation in a community-based cohort of injection drug users in Chennai, India. Addiction 2012;107:349–58. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03602.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aidala A, Cross JE, Stall R, et al. Housing status and HIV risk behaviors: implications for prevention and policy. AIDS Behav 2005;9:251–65. 10.1007/s10461-005-9000-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dickson-Gomez J, Hilario H, Convey M, et al. The relationship between housing status and HIV risk among active drug users: a qualitative analysis. Subst Use Misuse 2009;44:139–62. 10.1080/10826080802344823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bourgois P. The moral economies of homeless heroin addicts: confronting ethnography, HIV risk, and everyday violence in San Francisco shooting encampments. Subst Use Misuse 1998;33:2323–51. 10.3109/10826089809056260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rhodes T, Singer M, Bourgois P, et al. The social structural production of HIV risk among injecting drug users. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:1026–44. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sherman SG, Cheng Y, Kral AH. Prevalence and correlates of opiate overdose among young injection drug users in a large U.S. city. Drug Alcohol Depend 2007;88:182–7. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shah NG, Celentano DD, Vlahov D, et al. Correlates of enrollment in methadone maintenance treatment programs differ by HIV-serostatus. AIDS 2000;14:2035–43. 10.1097/00002030-200009080-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Appel PW, Ellison AA, Jansky HK, et al. Barriers to enrollment in drug abuse treatment and suggestions for reducing them: opinions of drug injecting street outreach clients and other system stakeholders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2004;30:129–53. 10.1081/ADA-120029870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Havens JR, Latkin CA, Pu M, et al. Predictors of opiate agonist treatment retention among injection drug users referred from a needle exchange program. J Subst Abuse Treat 2009;36:306–12. 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Genberg BL, Gange SJ, Go VF, Vf G, et al. The effect of neighborhood deprivation and residential relocation on long-term injection cessation among injection drug users (IDUs) in Baltimore, Maryland. Addiction 2011;106:1966–74. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03501.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Berg KM, Demas PA, Howard AA, et al. Gender differences in factors associated with adherence to antiretroviral therapy. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:1111–7. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30445.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Appel PW, Tsemberis S, Joseph H, et al. Housing First for severely mentally ill homeless methadone patients. J Addict Dis 2012;31:270–7. 10.1080/10550887.2012.694602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hawk M, Davis D. The effects of a harm reduction housing program on the viral loads of homeless individuals living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care 2012;24:577–82. 10.1080/09540121.2011.630352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Davey-Rothwell MA, Latimore A, Hulbert A, et al. Sexual networks and housing stability. J Urban Health 2011;88:759–66. 10.1007/s11524-011-9570-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mizuno Y, Purcell DW, Zhang J, et al. Predictors of current housing status among HIV-seropositive injection drug users (IDUs): results from a 1-year study. AIDS Behav 2009;13:165–72. 10.1007/s10461-008-9364-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kasinitz P. Gentrification and Homelessness: The Single Room Occupant and the Inner City Revival. The Urban And Social Change Review 1984;17:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reese E, DeVerteuil G, Thach L. ‘Weak-Center’ Gentrification and the Contradictions of Containment: deconcentrating poverty in downtown Los Angeles. Int J Urban Reg Res 2010;34:310–27. 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00900.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Linton SL, Kennedy CE, Latkin CA, et al. ‘Everything that looks good ain’t good!’: perspectives on urban redevelopment among persons with a history of injection drug use in Baltimore, Maryland. Int J Drug Policy 2013;24:605–13. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Crack CR. ‘Cocaine and Heroin: drug Eras in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, 1960-2000’ . Add Res & Theory 2003;11:47–63. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Race GMB. Class, power, and organizing in East Baltimore: rebuilding abandoned communities in America. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gomez MB, Muntaner C. Urban redevelopment and neighborhood health in East Baltimore, Maryland: the role of communitarian and institutional social capital. Crit Public Health 2005;15:83–102. 10.1080/09581590500183817 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Johnson RA. African Americans and homelessness: moving through history. J Black Stud 2010;40:583–605. 10.1177/0021934708315487 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Freeman L, Braconi F. Gentrification and displacement New York City in the 1990s. J Am Plann Assoc 2004;70:39–52. 10.1080/01944360408976337 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Davila A. Dreams of place: housing, gentrification, and the marketing of space in El Barrio. Centro Journal 2003;15:112–37. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Marcuse P. Gentrification, abandonment, and displacement:connections, Causes, and Policy responses in New York City. J Urb Contemp L 1985;28:195–240. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fullilove MT. Root shock: how tearing up city neighborhoods hurts merican and what we can do about it. First Edition New York, NY: The Random House Publishing Group, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Whittle HJ, Palar K, Hufstedler LL, et al. Food insecurity, chronic illness, and gentrification in the San Francisco Bay Area: an example of structural violence in United States public policy. Soc Sci Med 2015;143:154–61. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Culhane DP, Lee Chang‐Moo, Wachter SM. Where the homeless come from: a study of the prior address distribution of families admitted to public shelters in New York City and Philadelphia. Hous Policy Debate 1996;7:327–65. 10.1080/10511482.1996.9521224 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Belcher JR, DeForge BR, Stigma S. Social stigma and homelessness: the limits of Social Change. J Hum Behav Soc Environ 2012;22:929–46. 10.1080/10911359.2012.707941 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gallagher KM, Sullivan PS, Lansky A, et al. Behavioral surveillance among people at risk for HIV infection in the U.S.: the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System. Public Health Rep 2007;122:32–8. 10.1177/00333549071220S106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. CDC. HIV/AIDS surveillance Report, 2006. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 47. OMB. Provisional guidance on the implementation of the 1997 standards for federal data on race and ethnicity, Executive Office of the President, December 15. U.S: Office of Management and Budget, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Carter G. From Exclusion to Destitution: race, affordable housing, and homelessness Cityscape . J Policy Develop Res 2011;13:33–70. [Google Scholar]

- 49. American Community Survey and Puerto Rico Community survey : 2011 subject definitions. Washington, DC: United States Census Bureau, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Messer LC, Laraia BA, Kaufman JS, et al. The development of a standardized neighborhood deprivation index. J Urban Health 2006;83:1041–62. 10.1007/s11524-006-9094-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Krieger N, Barbeau EM, Soobader MJ, et al. Class matters: U.S. versus U.K. measures of occupational disparities in access to health services and health status in the 2000 U.S. National Health Interview Survey. Int J Health Serv 2005;35:213–36. 10.2190/JKRE-AH92-EDV8-VHYC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Freeman L. There goes the 'hood: views of gentrification from the ground up. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Huynh M, Maroko AR. Gentrification and preterm birth in New York City, 2008–2010. J Urban Health 2014;91:211–20. 10.1007/s11524-013-9823-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sturtevant L, Viveiros J. How investing in housing can save on health care: a research review and comment on future directions for integrating housing and health services. Washington, DC: Center for Housing Policy, National Housing Conference, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Vitale AS. The Safer Cities Initiative and the removal of the homeless. Criminol Public Policy 2010;9:867–73. 10.1111/j.1745-9133.2010.00677.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Culhane DP. Tackling homelessness in Los Angeles' Skid row. Criminol Public Policy 2010;9:851–7. 10.1111/j.1745-9133.2010.00675.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Popkin S, Katz B, Cunningham K, et al. A decade of HOPE VI: research findings and policy challenges. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hartley D. Gentrification and financial health. Cleveland, OH: Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Belsky ES, Goodman J, Drew R. Measuring the nation's rental housing affordability problems. Cambridge, MA: Joint Center for Housing Studies, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kreager DA, Lyons CJ, Hays ZR. Urban revitalization and seattle crime, 1982-2000. Soc Probl 2011;58:615–39. 10.1525/sp.2011.58.4.615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Linton SL, Jennings JM, Latkin CA, et al. Application of space-time scan statistics to describe geographic and temporal clustering of visible drug activity. J Urban Health 2014;91:940–56. 10.1007/s11524-014-9890-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hyra D. The back-to-the-city movement: neighbourhood redevelopment and processes of political and cultural displacement. Urban Stud 2015;52:1753–73. 10.1177/0042098014539403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gibbs Knotts H, Haspel M. The impact of gentrification on Voter Turnout*. Soc Sci Q 2006;87:110–21. 10.1111/j.0038-4941.2006.00371.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Cheng T, Wood E, Feng C, et al. Transitions into and out of homelessness among street-involved youth in a canadian setting. Health Place 2013;23:122–7. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. McCreesh N, Frost SD, Seeley J, et al. Evaluation of respondent-driven sampling. Epidemiology 2012;23:138–47. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31823ac17c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Abdul-Quader AS, Heckathorn DD, McKnight C, et al. Effectiveness of respondent-driven sampling for recruiting drug users in New York City: findings from a pilot study. J Urban Health 2006;83:459–76. 10.1007/s11524-006-9052-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Burt RD, Hagan H, Sabin K, et al. Evaluating respondent-driven sampling in a Major metropolitan area: comparing injection drug users in the 2005 Seattle area national HIV behavioral surveillance system survey with participants in the RAVEN and Kiwi studies. Ann Epidemiol 2010;20:159–67. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013823supp001.doc (85KB, doc)