Abstract

Objectives

Thromboembolic events are the major factor affecting the prognosis of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Haemostatic alterations are possible causes of these complications, but their roles remain poorly characterised. In the prospective observational study, we investigated the entire coagulation process in patients with CKD to elucidate the mechanisms of their high thromboembolic risk.

Methods

A total of 95 patients with CKD and 20 healthy controls who met the inclusion criteria were consecutively recruited from September 2015 to March 2016. The platelet count, platelet aggregation, von Willebrand factor antigen (vWF:Ag), vWF ristocetin cofactor activity (vWF:RCo), fibrinogen, factor V (FV), FVII, FVIII, antithrombin III, protein C, protein S, D-dimer, standard coagulation tests and thromboelastography were measured in patients with CKD and controls. Associations between the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and haemostatic biomarkers were tested using multivariable linear regression.

Results

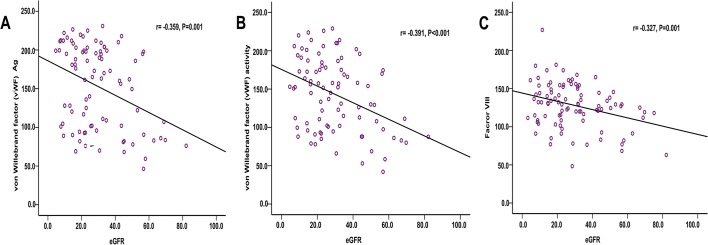

The adjusted and unadjusted levels of vWF:Ag, vWF:RCo, fibrinogen, FVII, FVIII and D-dimer were significantly higher in patients with CKD than that in the healthy controls, and were elevated with CKD progression. However, after adjustment for baseline differences, platelet aggregation and thromboelastography parameters showed no significant differences between patients with CKD and healthy controls. In the correlation analysis, vWF:Ag, vWF:RCo and FVIII were inversely associated with eGFR (r=−0.359, p<0.001; r=−0.391, p<0.001; r=−0.327, p<0.001, respectively). During the 1-year of follow-up, one cardiovascular event occurred in patients with CKD 5 stage, whereas no thromboembolic event occurred in the CKD 3 and 4 and control groups.

Conclusions

Patients with CKD are characterised by endothelial dysfunction and increased coagulation, especially FVIII activity. The abnormal haemostatic profiles may contribute to the elevated risk of thrombotic events but further longer-term study with large samples is still required to more precisely determine the relationship between the elevation of procoagulant factors and clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Chronic kidney disease, Coagulation, Thrombotic events, HypercoaguIable state

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Existing studies on the mechanism of coagulation in chronic kidney disease (CKD) are mostly limited to patients with end-stage renal disease requiring haemodialysis. The changes in the coagulation function of non-dialysis patients with moderate to severe CKD have not been completely clarified. In our research article, we investigated the entire coagulation process in non-dialysis patients with CKD.

We found that patients with CKD are characterised by endothelial dysfunction and increased coagulation, especially factor VIII activity. Besides, we also performed thromboelastography for dynamic observation of the entire coagulation process in patients with CKD but detected no changes in the coagulation function.

Due to the limited sample size and short term of follow-up, we might underestimate the risk of thromboembolic events in patients with CKD, which were not well linked the observations with clinical outcomes.

Introduction

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) commonly have blood coagulation disorders. The resulting thrombotic complications have become the most common cause of death and one of the difficulties in renal replacement therapy among patients with CKD.1–4 Existing studies on the mechanism of coagulation in CKD are mostly limited to haemodialysis patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD).5–7 The changes in the coagulation function of non-dialysis patients with moderate to severe CKD have not been completely clarified.

The coagulation process involves the participation of the platelets, vascular endothelium, coagulation system, anticoagulant system and fibrinolytic system. Most coagulation test methods reflect changes in a particular blood coagulation step but have difficulty completely verifying the entire coagulation process in patients with CKD. In the present study, several coagulation test methods were used to measure markers of platelet (platelet counts, platelet aggregability), endothelial function (von Willebrand factor antigen (vWF:Ag) and vWF ristocetin cofactor activity (vWF:RCo)), the major blood coagulation pathways (fibrinogen, factor V (FV), FVII and FVIII), and natural coagulation inhibitors (antithrombin III, protein S and protein C). Additionally, standard coagulation tests and thromboelastography (TEG) were adopted for dynamic observation of the entire coagulation process. The purpose of the study was to investigate the entire coagulation process in non-dialysis patients at different CKD stages to elucidate the mechanisms of their high thromboembolic risk and guide antithrombotic treatment.

Methods

Study design and subjects

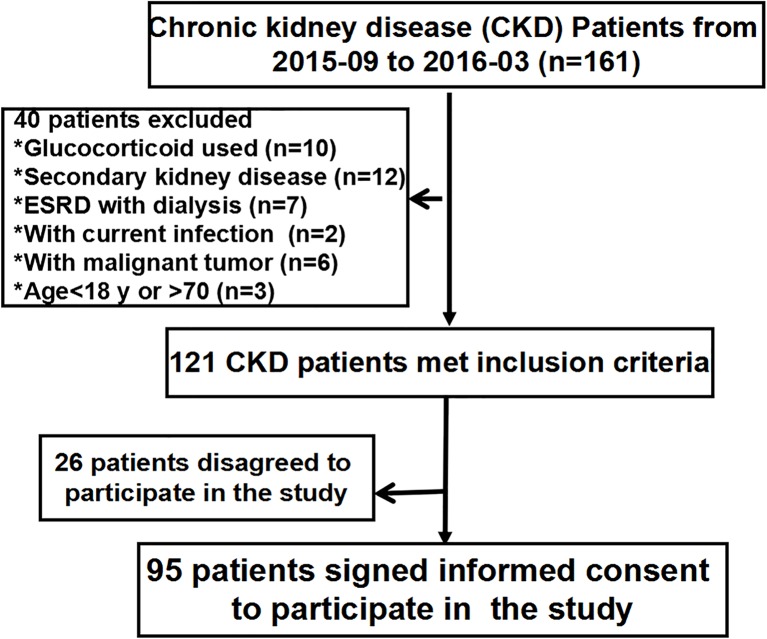

This prospective observational study was performed at the Department of Nephrology, Chinese PLA General Hospital. Between September 2015 and March 2016, consecutive patients 18–70 years of age with stage 3–5 non-dialysis-dependent CKD were included in this study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with secondary renal disease (diabetic nephropathy, lupus nephritis or antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-associated vasculitis); (2) patients with nephrotic syndrome; (3) patients with signs of acute infection, liver failure, trauma, surgery, cancer or pregnancy; (4) patients on glucocorticoids, immunosuppressive medication and anticoagulant medication within the past 1 month; and (5) patients with a history of previous thromboembolic or haemorrhagic events within 12 months. Finally, 95 patients with CKD met the exclusion criteria and agreed to participate in the study. Additionally, 20 age-matched and gender-matched healthy controls with no history of kidney disease who met the same exclusion criteria were recruited. Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study and the research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the General Hospital of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army. A flow chart is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

The flow chart of this study. ESRD, end-stage renal disease.

General data collection

We recorded the subjects’ general conditions (age, gender, height, weight, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure and smoking history), underlying diseases (coronary heart disease (CHD) and diabetes mellitus) and laboratory parameters (haemoglobin, white blood cell count, platelet count, serum albumin, serum creatinine, cholesterol, triglycerides and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR)).

We also calculated the body mass index (BMI) and mean arterial pressure (MAP) as follows: BMI=weight (kg)/[height (m)]2 and MAP=(systolic blood pressure +2·diastolic blood pressure)/3.

The Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation was used to estimate the glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).8 The CKD stage was defined according to the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative guidelines.9

Procoagulant and anticoagulant factors

Fasting cubital venous blood specimens were collected in the morning and mixed with 109 mmol/L sodium citrate for anticoagulation (sodium citrate:blood=1:9). The blood samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min within 1 hour of collection to obtain platelet-poor plasma. FV, FVII and FVIII activities as well as the anticoagulant factors protein C and protein S were analysed by clotting assays. vWF:Ag and vWF:RCo were measured by immunoturbidimetric assay. All instruments (ACL TOP700) and reagents were purchased from USA Instrumentation Laboratory Company.

Platelet aggregation tests

Platelet aggregation was measured by light transmittance aggregometry. Citrate-anticoagulated whole blood was centrifuged at 800 rpm for 5 min to obtain platelet-rich plasma. Platelet-poor plasma was obtained from the remaining specimen by further centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 min. Platelet-rich plasma was adjusted to reach a platelet count of 250×109/L. Platelet aggregability was assessed at 37°C with an AggRam aggregometer (Helena Laboratories, Beaumont, Texas, USA). Platelets were stimulated by 10 µmol/L ADP. Aggregation was expressed as the maximum per cent change in light transmittance from baseline, with platelet-poor plasma as a reference.

Standard coagulation tests

The activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), prothrombin time (PT) and fibrinogen were analysed by the magnetic bead assay. Antithrombin III was analysed by the chromogenic substrate assay. The D-dimer content was measured by immunoturbidimetry using a device and reagents purchased from Stago (France).

Thromboelastography

The coagulation status was assessed via TEG using citrated whole blood samples. For each TEG assay, citrated whole blood (1 mL) was pipetted into a phial containing 1% kaolin and inverted five times to ensure mixing of kaolin with the blood. Then, 340 µl of kaolin-activated citrated whole blood was transferred to a TEG cup to which 20 µl of 0.2 mol/L CaCl2 had been preloaded for recalcification. The TEG analyser was stopped 40–60 min after reaching the maximum amplitude (MA) at 37°C. The parameters included (1) reaction time (R)—time from the start of the test to a TEG amplitude of 2 mm, reflecting the combined effect of the coagulation factors involved in the initiation of haemostasis; (2) K-time (K)—the period from the TEG amplitude of 2 mm to when the curve reached an amplitude of 20 mm, which measured the rate of clot formation (fibrin cross linking); (3) α-angle—the angle between the tangent line (drawn from the split point to the curve) and the horizontal base line, representing the acceleration of fibrin build-up and cross linking; and (4) MA—indicative of the strength of the clot that reflected the cross interaction between platelet functions and coagulation.

Thromboembolic events

The incidence of thromboembolic events in patients with CKD and healthy controls was recorded during the 1 year of follow-up. Evidence suggests that patients with suspected thromboembolic events should be managed with a diagnostic strategy that includes clinical pretest probability in the form of prediction scores, D-dimer test and appropriate clinical imaging results.10

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS software, V.19.0. The results are expressed as the mean ± SD or the median (range) for continuous data and as a frequency or percentage for categorical data. We initially compared baseline characteristics among patients with CKD and healthy controls using analysis of variance, Kruskal-Wallis test or χ2 test as appropriate. A generalised linear model estimating procedure was used to obtain adjusted mean levels of procoagulant biomarkers within renal function categories. Using multivariable linear regression, we examined the association of eGFR with haemostatic biomarkers. eGFR and other baseline characteristics were the independent variables and the biomarkers were the dependent variables in these analyses. p Values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

Baseline characteristics of patients with CKD and healthy controls are shown in table 1. No significant differences were detected in age, gender ratio, BMI, white blood cell or cholesterol between patients with CKD and healthy controls. Subjects with CKD stage 5 (CKD 5) had higher MAP, triglyceride and UACR but lower haemoglobin and serum albumin levels than the healthy controls. Given the small number of subjects with concomitant CHD, diabetes mellitus and smoking in the CKD and healthy control groups, we combined patients with CKD stages 3–5 for comparison with the healthy controls. However, no significant differences were found between patients with CKD and healthy controls regarding CHD, diabetes mellitus or smoking ratio.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with CKD and healthy controls

| Variables | Healthy control | CKD 3 | CKD 4 | CKD 5 | p |

| No. of patients | 20 | 32 | 38 | 25 | |

| Gender, M, n (%) | 9 (47%) | 22 (69%) | 25 (66%) | 13 (52%) | 0.225 |

| Age (year) | 39.7±16.7 | 40.3±11.3 | 44.5±14.4 | 44.0±13.7 | 0.443 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.3±4.3 | 24.4±4.2 | 24.7±3.6 | 23.8±4.2 | 0.582 |

| MAP (mm Hg) | 89.5±9.3* | 95.0±9.4* | 97.5±8.5** | 103.8±17.2* | <0.001 |

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 136.3±17.4* | 131.2±20.2* | 118.9±18.1** | 98.5±14.2* | <0.001 |

| White blood cell (109/L) | 6.1±1.6 | 7.1±2.1 | 7.1±1.5 | 6.9±2.2 | 0.398 |

| Serum albumin (g/L) | 43.2±2.9* | 41.1±3.4 | 40.7±3.4 | 39.1±3.6* | 0.004 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L) | 69.4±13.5* | 155.5±31.5** | 265.7±63.4** | 542.1±237.1* | <0.001 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2 | 101.4±21.9* | 48.9±13.9** | 24.7±6.3** | 10.9±4.1* | <0.001 |

| Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.2±0.9 | 4.2±1.2 | 4.2±0.8 | 4.0±0.9 | 0.959 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 1.2±0.6 | 1.9±0.9* | 2.3±1.1** | 1.7±0.8 | 0.003 |

| UACR (mg/g) | 7.3±2.7* | 201.9±142.7** | 313.8±139.5** | 472.2±224.1* | <0.001 |

| CHD, n (%) | 2 (10%) | 1 (3%) | 3 (8%) | 1 (4%) | 0.753 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 1 (5%) | 2 (6%) | 3 (8%) | 3 (11%) | 0.523 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 2 (10%) | 7 (21%) | 6 (15%) | 1 (4%) | 0.457 |

Data are expressed as mean±SD or median (IQR) as appropriate.

*p<0.05 versus CKD 5 group, **p<0.05 versus control group.

BMI, body mass index; CHD, coronary heart disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; MAP, mean arterial pressure; UACR, urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio.

Procoagulant biomarkers according to CKD

Table 2 shows the procoagulant biomarkers by CKD status. Levels of FVII, FVIII, vWF:Ag, vWF:RCo, fibrinogen and D-dimer were significantly higher in patients with CKD than the levels in the controls before and after adjustment for age, gender, history of diabetes, history of CHD, smoking status, MAP, BMI, haemoglobin, serum albumin, cholesterol, triglyceride and UACR (adjusted values shown in online supplementary table 1). The magnitude of elevation of the given parameters was proportional to severity of CKD. Prior to adjustment, platelet aggregability was significantly higher and protein C was lower in patients with CKD 5 than that in the controls; however, no significant differences were found after adjustment (p=0.736 and p=0.267, respectively). Irrespective of the adjustment, platelet count, FV, antithrombin III, APTT and PT showed no significant differences among patients with CKD 3–5 and the healthy controls.

Table 2.

Procoagulant biomarkers by chronic kidney disease status.

| Variables | Healthy control | CKD 3 | CKD 4 | CKD 5 | p | p† |

| Platelet (109/L) | 237.2±47.4 | 214.8±65.0 | 214.0±52.8 | 195.8±58.6 | 0.156 | 0.284 |

| ADPLTA (%)& | 64.6±4.8♦ | 67.3±8.6♦ | 70.1±8.6 | 74.7±8.2* | 0.041 | 0.738 |

| Factor V (%) | 113.6±26.1 | 98.4±31.9 | 106.7±36.9 | 103.4±33.3 | 0.533 | 0.640 |

| Factor VII (%) | 74.2±14.3♦ | 94.5±18.0*♦ | 104.2±17.9* | 108.4±27.2* | <0.001 | 0.050 |

| Factor VIII (%) | 86.5±22.3♦ | 115.3±25.1*♦ | 130.5±27.6* | 139.9±33.0* | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| VWF:Ag (%) | 103.1±42.4♦ | 124.7±51.4♦ | 158.9±49.9* | 181.8±45.6* | <0.001 | 0.011 |

| vWF:RCo (%) | 99.8±29.9♦ | 115.5±43.2♦ | 150.2±45.1* | 168.2±41.5* | <0.001 | 0.004 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 3.0±0.8♦ | 3.1±0.7♦ | 3.8±0.8*♦ | 4.5±1.1* | <0.001 | 0.006 |

| Protein C (%) | 105.3±17.0♦ | 99.4±18.6♦ | 93.5±17.9 | 86.6±15.2* | 0.024 | 0.736 |

| Protein S (%) | 76.8±23.2 | 88.2±24.6 | 94.5±20.7 | 99.5±25.5 | 0.076 | 0.584 |

| AT III (%) | 99.5±9.3 | 103.8±12.2 | 103.8±11.7 | 103.1±11.8 | 0.658 | 0.189 |

| D-dimer (ng/ml) | 257±116♦ | 425±277♦ | 505±320*♦ | 842±496* | <0.001 | 0.039 |

| APTT (s) | 39.0±4.5 | 37.7±3.2 | 37.5±3.7 | 39.0±4.2 | 0.286 | 0.187 |

| PT (s) | 13.4±0.6 | 13.5±0.6 | 13.5±0.6 | 13.7±0.6 | 0.320 | 0.192 |

ADPLTA (%): platelet aggregation records were available in 49 CKD cases (15 cases in CKD 3 stage; 21 cases in CKD 4 stage; 13 cases in CKD 5 stage) and 9 healthy controls.

*p<0.05 versus control group;♦p<0.05 versus CKD 5 group.

†p Values for the adjusted model. Data are adjusted for age, sex, history of diabetes, history of coronary heart disease, smoking status, mean arterial pressure, body mass index, haemoglobin, serum albumin, cholesterol, triglyceride and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio.

APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; AT III, antithrombin III; CKD, chronic kidney disease; LTA, light transmittance aggregometry; PT, prothrombin time; vWF:Ag, von Willebrand factor antigen; vWF:RCo, vWF ristocetin cofactor activity.

bmjopen-2016-014294supp001.pdf (245.7KB, pdf)

In order to make our research more accurate, we further excluded smokers as well as patients with diabetes mellitus and uncontrolled hypertension, and then compared the haemostatic profiles among these patients by CKD status. The results showed that the positive associations of renal insufficiency with these procoagulant biomarkers were similar in participants with or without the above-mentioned comorbidities (online supplementary table 2).

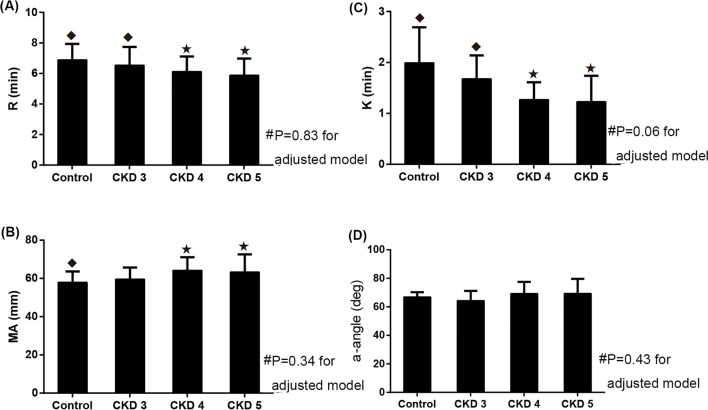

Thromboelastography

Figure 2 compares the TEG parameters between patients with CKD and the healthy controls. The results showed that the R time and K time in the unadjusted cohort were hypercoagulable in patients with CKD 4 and 5 compared with patients with CKD 3 and the healthy controls (p<0.05). The MA values in the CKD 5 group were significantly higher than the values in the control group (63.3±9.3 mm vs 57.9±5.7 mm, p=0.046). However, after adjustment for relevant factors, no significant differences were found in the R, K, MA and α-angle values between patients with CKD and the healthy controls.

Figure 2.

TEG parameters in healthy controls and patients with CKD. (A) R value. (B) K value. (C) MA value. (D) α-angle value. #p Values for the adjusted model. Data are adjusted for age, sex, history of diabetes, history of CHD, smoking status, MAP, BMI, haemoglobin, serum albumin, cholesterol, triglyceride and UACR. *p<0.05 versus control group for unadjusted values; ◆p<0.05 versus CKD 5 group for unadjusted values. BMI, body mass index; CHD, coronary heart disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; MA, maximum amplitude; MAP, mean arterial pressure; TEG, thromboelastography; UACR, urinary albumin to creatinine ratio.

Associations between renal function and haemostatic biomarkers

As shown in figure 3, vWF:Ag, vWF:RCo and FVIII were inversely correlated with eGFR (r=−0.359, p=0.001; r=−0.391, p<0.001; r=−0.327, p=0.001). Besides, we also used multivariable linear regression to analyse the associations between eGFR and haemostatic biomarkers. Adjustment for age, sex, history of diabetes, history of CHD, smoking status, MAP, BMI, haemoglobin, serum albumin, eGFR, cholesterol, triglyceride, and UACR, higher vWF:Ag, vWF:RCo and FVIII were significantly associated with a decreased eGFR (regression coefficients: −0.92 (−1.33, –0.40); −0.82 (−1.19, −0.45); and −0.50 (−0.69, –0.31), respectively).

Figure 3.

Correlation of vWF:Ag, vWF:RCo and FVIII levels with eGFR. (A) Correlation of vWF:Ag with eGFR. (B) Correlation of vWF:RCo with eGFR. (C) Correlation of FVIII with eGFR. Regression lines: (A) vWF:Ag=186.3−1.12×eGFR. (B) vWF:RCo=174.2−1.05×eGFR. (C) FVIII=143.2−0.52×eGFR. eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FVIII, factor VIII; vWF:Ag, von Willebrand factor antigen; vWF:RCo, vWF ristocetin cofactor activity.

Thromboembolic events

One cardiovascular event (acute myocardial syndrome) occurred in patients with CKD 5 stage, whereas no thromboembolic event occurred in the CKD 3 and 4 and control groups during the 1 year of follow-up.

Discussion

We evaluated the coagulation profiles in patients with CKD who were not receiving dialysis using multiple laboratory methods, including the vascular endothelium, coagulation factor, anticoagulation system, conventional blood test, standard coagulation tests and TEG.

vWF, which is a large molecular weight glycoprotein synthesised and secreted by endothelial cells and megakaryocytes, exerts a procoagulant effect through platelet adhesion and aggregation and FVIII stabilisation.11 The increased vWF is a sign of endothelial injury and a risk for thromboembolic events.12 13 Fibrinogen, FVII and FVIII are important coagulation factors in the coagulation pathway, whereas D-dimer reflects the activation of the coagulation system and the formation of blood clots in the body. Fibrinogen, FVII, FVIII and D-dimer have also been shown to be associated with an increased prevalence of thromboembolic events.14–17

In our study, we observed elevated D-dimer, fibrinogen, FVII, and especially FVIII and vWF levels in patients with CKD. And the coagulation was increased with the aggravation of renal injury. Patients with CKD often present higher levels of traditional risk factors for thromboembolic events, such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity and dyslipidaemia18; these factors also affect the coagulation system. In our attempt to explain haemostatic alterations in CKD, we adjusted for the above influencing factors. The results showed that procoagulant factors were still significantly elevated in patients with CKD, indicating that kidney dysfunction affected the activation of coagulation function in addition to traditional risk factors.

Possible mechanisms to explain the association of lower eGFR and higher levels of haemostatic factors are as follows. (1) With CKD progression, renal impairment is aggravated and a large number of renal units are damaged, resulting in the loss of normal excretory function and a reduction in the removal of procoagulant substances. A few studies found that the metabolism and elimination of fibrinogen and D-dimer were decreased in CKD and ESRD.19–21 (2) The increase in the FVII level may be due to vascular endothelial damage in patients with CKD, resulting in tissue factor expression.22 (3) Moreover, extensive research has found that vWF, fibrinogen and FVIII are associated with the inflammatory response.23 Patients with CKD are commonly associated with changes in the levels of various inflammatory cytokines.24 Proinflammatory substances can activate procoagulant factors and result in elevated levels of particular haemostatic factors.

TEG displays blood clot formation dynamics from initial thrombin generation to fibrinolysis.25 In the current study, we also performed TEG for dynamic observation of the entire coagulation process in patients with CKD. Prior to adjustment for confounding factors, the TEG data suggested that all aspects of coagulation were increased in patients with CKD, including initial fibrin formation, fibrin–platelet interactions and qualitative platelet functions. However, after adjustment for relevant influencing factors, we found no significant differences in the TEG parameters (R, K, MA and α-angle) between patients with CKD and the healthy controls, which is in contrast to previous TEG studies in haemodialysis patients with ESRD.26 27 Haemodialysis patients are influenced by haemodynamic factors and coagulant use and thus present more complicated changes in coagulation functions, which are different from those in non-dialysis patients with CKD.5 Thus, whether TEG can be used to effectively evaluate the integrated coagulation function in non-dialysis patients with CKD requires further validation.

In this study, the cardiovascular event occurred in one patient with CKD 5 stage during the 1 year of follow-up. This clinical outcome may not be consistent with previous Heart Outcomes and Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) study which includes 980 subjects and shows 22.2% cumulative incidence of cardiovascular events.28 However, it should be noted that patients in HOPE study are older (at least 55 years of age) and have higher cardiovascular risk compared with our participants. Besides, the follow-up time (3.5–5.5 years) is much longer than that of our current study. The small sample size and short-term follow-up in our study might underestimate the risk of thromboembolic events and make it difficult to link the observations with clinical outcomes. Further longer-term study with large samples is still required to more precisely determine the relationship between the elevation of procoagulant factors and clinical outcomes.

The present study has certain limitations. One limitation of this study is the limited number of individuals in the different patient groups and the short term of follow-up. We could not fully evaluate the thromboembolic events. Thus, it limited the applicability of the conclusion of this study. Second, the CKD groups were heterogeneous with a number of factors and complications interfering with the delicate system of haemostasis, even though we had adjusted the related factors and also assessed the haemostatic profiles in small number of participants without the comorbidities.

Conclusions

In conclusion, patients with CKD are characterised by endothelial dysfunction and increased coagulation, especially FVIII activity. The abnormal haemostatic profiles may contribute to the elevated risk of thrombotic events and further longer-term study with large samples is still required to more precisely determine the relationship between the elevation of procoagulant factors and clinical outcomes. TEG detected no changes in the coagulation function among patients with CKD. Whether TEG can effectively evaluate the integrated coagulation function in patients with CKD needs to be verified using larger samples. Future studies are required to target the role of coagulation management for patients with CKD to reduce comorbidities.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: HMJ, WRB and CXM created and designed this study. HMJ, WY, STY, LQP and YX collected and analysed the data. HMJ, WRB, DP and LP contributed to the preparation and editing of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Sciences Foundation of China (grant numbers 81471027, 81273968, and 81072914); the ministerial projects of the National Working Commission on Aging (grant number QLB2014W002); and The Four Hundred Project of 301 (grant number YS201408).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Ethics Committee of the General Hospital of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Reference

- 1. Liang CC, Wang SM, Kuo HL, et al. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2014;9:1354–9. 10.2215/CJN.09260913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wattanakit K, Cushman M, Stehman-Breen C, et al. Chronic kidney disease increases risk for venous thromboembolism. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008;19:135–40. 10.1681/ASN.2007030308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bos MJ, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, et al. Decreased glomerular filtration rate is a risk factor for hemorrhagic but not for ischemic stroke: the Rotterdam Study. Stroke 2007;38:3127–32. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.489807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Sarnak MJ. Clinical epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis 1998;32:S112–S119. 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9820470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Darlington A, Ferreiro JL, Ueno M, et al. Haemostatic profiles assessed by thromboelastography in patients with end-stage renal disease. Thromb Haemost 2011;106:67–74. 10.1160/TH10-12-0785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Molino D, De Lucia D, Gaspare De Santo N. Coagulation disorders in Uremia. Semin Nephrol 2006;26:46–51. 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2005.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vaziri ND, Gonzales EC, Wang J, et al. Blood coagulation, fibrinolytic, and inhibitory proteins in end-stage renal disease: effect of hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 1994;23:828–35. 10.1016/S0272-6386(12)80136-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:604–12. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 2002;39:S1–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hogg K, Wells PS, Gandara E. The diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. Semin Thromb Hemost 2012;38:691–701. 10.1055/s-0032-1327770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Béguin S, Kumar R, Keularts I, et al. Fibrin-dependent platelet procoagulant activity requires GPIb receptors and von willebrand factor. Blood 1999;93:564–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Danesh J, Wheeler JG, Hirschfield GM, et al. C-reactive protein and other circulating markers of inflammation in the prediction of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1387–97. 10.1056/NEJMoa032804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rumley A, Lowe GD, Sweetnam PM, et al. Factor VIII, Von Willebrand factor and the risk of Major ischaemic heart disease in the Caerphilly Heart Study. Br J Haematol 1999;105:110–6. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1999.01317.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kirmizis D, Tsiandoulas A, Pangalou M, et al. Validity of plasma fibrinogen, D-dimer, and the von willebrand factor as markers of cardiovascular morbidity in patients on chronic hemodialysis. Med Sci Monit 2006;12:89–62. 10.1016/S1567-5688(06)80328-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bash LD, Erlinger TP, Coresh J, et al. Inflammation, hemostasis, and the risk of kidney function decline in the Atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) Study. Am J Kidney Dis 2009;53:596–605. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.10.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Folsom AR, Delaney JA, Lutsey PL, et al. Associations of factor VIIIc, D-dimer, and plasmin-antiplasmin with incident cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. Am J Hematol 2009;84:349–53. 10.1002/ajh.21429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Folsom AR, Cushman M, Heckbert SR, et al. Factor VII coagulant activity, factor VII -670A/C and -402G/A polymorphisms, and risk of venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost 2007;5:1674–8. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02620.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rucker D, Tonelli M. Cardiovascular risk and management in chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2009;5:287–96. 10.1038/nrneph.2009.42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gordge MP, Faint RW, Rylance PB, et al. Plasma D dimer: a useful marker of fibrin breakdown in renal failure. Thromb Haemost 1989;61:522–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shibata T, Magari Y, Kamberi P, et al. Significance of urinary fibrin/fibrinogen degradation products (FDP) D-dimer measured by a highly sensitive ELISA method with a new monoclonal antibody (D-D E72) in various renal diseases. Clin Nephrol 1995;44:91–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lane DA, Ireland H, Knight I, et al. The significance of fibrinogen derivatives in plasma in human renal failure. Br J Haematol 1984;56:251–60. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1984.tb03953.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kario K, Matsuo T, Matsuo M, et al. Marked increase of activated factor VII in uremic patients. Thromb Haemost 1995;73:763–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Levi M, Keller TT, van Gorp E, et al. Infection and inflammation and the coagulation system. Cardiovasc Res 2003;60:26–39. 10.1016/S0008-6363(02)00857-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kaysen GA. The microinflammatory state in Uremia: causes and potential consequences. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001;12:1549–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Karon BS. Why is everyone so excited about thromboelastrography (TEG)? Clin Chim Acta 2014;436:143–8. 10.1016/j.cca.2014.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Holloway DS, Vagher JP, Caprini JA, et al. Thrombelastography of blood from subjects with chronic renal failure. Thromb Res 1987;45:817–25. 10.1016/0049-3848(87)90091-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pivalizza EG, Abramson DC, Harvey A. Perioperative hypercoagulability in uremic patients: a viscoelastic study. J Clin Anesth 1997;9:442–5. 10.1016/S0952-8180(97)00097-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mann JF, Gerstein HC, Pogue J, et al. Renal insufficiency as a predictor of cardiovascular outcomes and the impact of ramipril: the HOPE randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:629–36. 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014294supp001.pdf (245.7KB, pdf)