Abstract

At a certain point in development, axons in the mammalian CNS undergo a profound loss of intrinsic growth capacity, which leads to poor regeneration after injury. Overexpression of Bcl-2 prevents this loss, but the molecular basis of this effect remains unclear. Here, we report that Bcl-2 supports axonal growth by enhancing intracellular Ca2+ signaling and activating cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) and extracellular-regulated kinase (Erk), which stimulate the regenerative response and neuritogenesis. Expression of Bcl-2 decreases endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ uptake and storage, and thereby leads to a larger intracellular Ca2+ response induced by Ca2+ influx or axotomy in Bcl-2-expressing neurons than in control neurons. Bcl-xL, an antiapoptotic member of the Bcl-2 family that does not affect ER Ca2+ uptake, supports neuronal survival but cannot activate CREB and Erk or promote axon regeneration. These results suggest a novel role for ER Ca2+ in the regulation of neuronal response to injury and define a dedicated signaling event through which Bcl-2 supports CNS regeneration.

Keywords: axon growth potential, Bcl-2, calcium, CREB, Erk

Introduction

In the mammalian CNS, the exuberant growth of axons during development is markedly reduced as neurons mature losing their intrinsic capacity for axon elongation (Chen et al, 1995; Goldberg et al, 2002). For decades, the intracellular events controlling this transition remained obscure. Surprisingly, recent studies have suggested a pivotal role of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 in supporting the intrinsic regenerative capacity of severed CNS axons (Chen et al, 1997; Cho et al, 2005). Expression of Bcl-2 in CNS neurons correlates with axon elongation in the developing brain (Merry et al, 1994), and deletion of the Bcl-2 gene reduces the ability of embryonic neurons to extend neurites in culture (Chen et al, 1997; Hilton et al, 1997). In contrast, constitutive expression of Bcl-2 in postnatal CNS neurons reverses the loss of intrinsic growth capacity by CNS axons and leads to robust optic nerve regeneration in postnatal mice (Chen et al, 1997; Cho et al, 2005). However, the mechanism by which Bcl-2 promotes axon regeneration remains unknown.

A critical question is whether Bcl-2 directly stimulates axon growth signals inside neurons to promote regeneration or merely supports cell survival, allowing surviving neurons to extend axons automatically. Bcl-xL is a member of the Bcl-2 family that is thought to be redundant with Bcl-2 in its capacity to protect cells from apoptosis (Gonzalez-Garcia et al, 1995). However, Bcl-2 expression correlates with axonal growth, whereas Bcl-xL is expressed at high levels in the mature CNS, where neurons have lost their intrinsic axonal growth capacity (Levin et al, 1997), suggesting that Bcl-xL cannot support axonal growth. Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL also differ in their subcellular localization. Bcl-2 is found in the mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and nuclear envelope—organelles with key roles in intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis—while Bcl-xL is targeted to the mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM) (Kaufmann et al, 2003). Thus, Bcl-xL and Bcl-2 may have distinct roles in regulating axon growth and intracellular Ca2+ dynamics.

Neural injury induces an intracellular Ca2+ response that reflects Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane or Ca2+-inducd Ca2+ release from the smooth ER. Localized, transient elevation of intracellular Ca2+ after injury has been reported to be necessary for membrane sealing, growth cone formation, and reinitiation of neuritogenesis in lower vertebrates, whose axons regenerate automatically (Ziv and Spira, 1997; Spira et al, 2001). In addition, an optimal range of intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) is required for proper axon elongation during development (Gu and Spitzer, 1995, 1997). Bcl-2 regulates ER Ca2+ content by decreasing ER Ca2+ uptake (Foyouzi-Youssefi et al, 2000; Pinton et al, 2001; Ferrari et al, 2002; Rudner et al, 2002). Bcl-xL is associated primarily with the mitochondria and has no known role in regulating ER Ca2+ content. Unlike Bcl-xL, Bcl-2 decreases the expression of calreticulin and ER Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA), two key proteins controlling ER Ca2+ influx and content (Pinton et al, 2001; Dremina et al, 2004). An emerging hypothesis suggests that Bcl-2 resides in the ER and mediates intracellular Ca2+ signaling induced by neural injury to support CNS regeneration.

Elevation of [Ca2+]i activates cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) and p44/p42 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/extracellular-regulated kinase (Erk) (Dolmetsch et al, 2001), both of which stimulate genes essential for neurite growth and plasticity. Activation of CREB by injury-induced influx of intracellular Ca2+ is critical for axon regeneration in neurons of lower vertebrates (Dash et al, 1998). In mammals, CREB expression is developmentally regulated (Lonze and Ginty, 2002). Neurons from mice harboring a null mutation in CREB display impaired axonal growth in development (Lonze et al, 2002). The MAPK/Erk pathway, which is also activated by intracellular Ca2+ and regulates neurite extension during development, can activate CREB, which in turn further supports neurite elongation (Adams and Sweatt, 2002).

In this study, to elucidate the molecular basis for CNS regeneration, we compared Ca2+ dynamics and subsequent signaling events in Bcl-2- and Bcl-xL-expressing retinal ganglion cells (RGCs)—a standard model of CNS neurons—and PC12 cells. Our findings define a new role for ER Ca2+ stores and Bcl-2 in regulating the intrinsic growth potential of CNS axons and initiating the dedicated signaling and transcriptional programs required for axon regeneration.

Results

Distinctive roles of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL

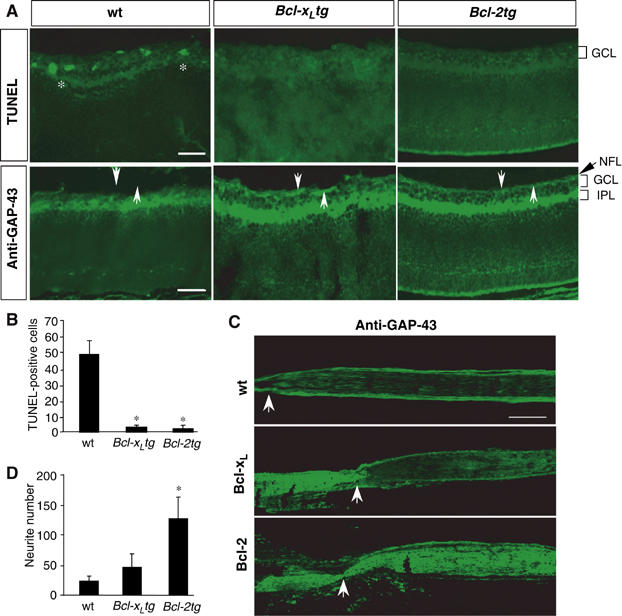

First, we determined if overexpression of Bcl-xL prevents injury-induced RGC loss and supports axonal regrowth as effectively as Bcl-2. Mice carrying a Bcl-2 (Bcl-2tg) (Martinou et al, 1994) or a Bcl-xL (Bcl-xLtg) (Parsadanian et al, 1998) transgene under the control of neuron-specific promoters were subjected to optic nerve crush on postnatal day 3 (P3), when RGCs of Bcl-2tg mice regenerate axons automatically in vivo (Chen et al, 1997; Cho et al, 2005). At 1 day after injury, TUNEL-positive apoptotic cells were 10-fold more abundant in retinal sections of wild-type (wt) controls than in Bcl-2tg or Bcl-xLtg mice (Figure 1A and B). Within 24 h, RGC axons in the nerve fiber layer and optic nerve degenerated rapidly in wt mice but not in Bcl-2tg and Bcl-xLtg mice (Figure 1A and C). Thus, overexpression of Bcl-xL was as effective as Bcl-2 expression in preventing axotomy-induced RGC death and axon degeneration.

Figure 1.

Bcl-xL supports survival but not axon regeneration of postnatal RGCs. (A) Transverse retinal sections from wt, Bcl-xLtg, and Bcl-2tg mice were stained with TUNEL and GAP-43 antibody on day 1 after optic nerve injury. Asterisks indicate TUNEL-positive cells; arrows indicate the nerve fiber layer (NFL). TUNEL-positive cells are present and the NFL is absent in the retinal sections of wt mice but not Bcl-xLtg or Bcl-2tg mice. GCL, ganglion cell layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Number of TUNEL-positive cells in retinal sections of wt, Bcl-xLtg and Bcl-2tg mice (n=4/group). (C) Longitudinal optic nerve sections from wt, Bcl-xLtg, and Bcl-2tg mice labeled with GAP-43 antibody 1–2 days after optic nerve injury. Arrows point to the crush site. Labeled axons in Bcl-xLtg mice remain anterior to the crush site, while those in Bcl-2tg mice grew robustly past the lesion site. Scale bar, 250 μm. (D) Retinal axon regrowth in retina–brain slice cocultures prepared from wt, Bcl-xLtg, and Bcl-2tg mice. Values are mean±s.d. *P<0.01 versus wt, two-tailed t-test.

To determine if overexpression of Bcl-xL promotes axon regeneration in vivo, we labeled RGC axons by injecting an anterograde tracer, cholera toxin B-subunit conjugated with rhodamine (CTB), into the eye immediately after the injury. CTB labeling and immunostaining with anti-GAP-43 revealed a failure of axon regeneration in Bcl-xLtg mice (n=9). Labeled RGC axons appeared healthy but stopped proximal to the crush site, with no sign of regeneration (Figure 1C). On day 4, RGC axons remained proximal to the injury in four of five Bcl-xLtg mice examined (Figure 1C); in one mouse, some labeled axons extended 200 μm distal to the lesion site (not shown). This finding is in sharp contrast to the robust optic nerve regeneration in Bcl-2tg mice (Figure 1C) (Chen et al, 1997; Cho et al, 2005) and suggests that overexpression of Bcl-xL does not support axon regeneration as effectively as Bcl-2. This finding was confirmed by measuring axonal regrowth in retina–brain slice cocultures (Chen et al, 1995) prepared from P2 mice. After 4 days, few neurites from wt or Bcl-xLtg retinal explants had grown into the brain slices, but neurite growth from the Bcl-2tg explants was extensive (Figure 1D).

These data demonstrate that axon regeneration does not occur as a default mechanism of neurons that survive injury. Although Bcl-xL protects neurons from injury-induced apoptosis, it cannot support axon regeneration.

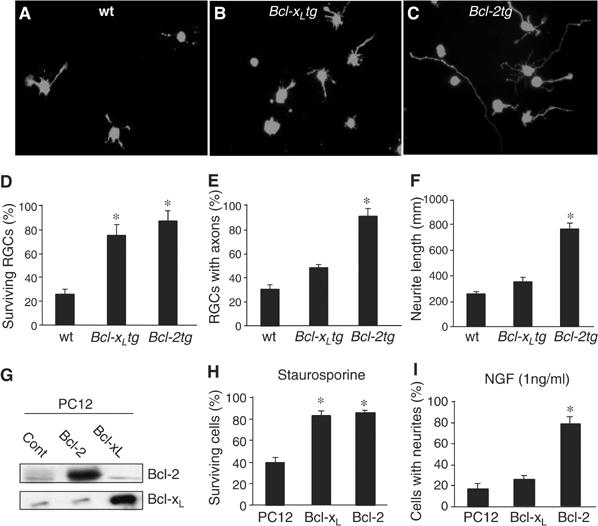

Bcl-2 acts cell-autonomously to support axon regeneration or neurite outgrowth

We next asked whether Bcl-2 acts intrinsically to support axon regeneration. RGCs were isolated from P2 wt, Bcl-xLtg, and Bcl-2tg mice and cultured in serum-free medium supplemented with neurotrophic factors (Figure 2A–C). Surviving RGCs were detected by staining with the vital dye calcein, and axons were identified by immunostaining with antibodies against tau or βIII-tubulin. RGCs from Bcl-xLtg and Bcl-2tg mice survived at comparable rates, which were significantly higher than the rate in wt cultures (Figure 2D). However, only one-third of surviving RGCs from wt and Bcl-xLtg mice extended axons, compared with >90% of those from Bcl-2tg mice (Figure 2E). Moreover, the RGCs of Bcl-2tg mice extended significantly longer neurites (Figure 2F). Thus, Bcl-2 acts intrinsically in RGCs to promote axonal regrowth, which functions independently of its support for neuronal survival.

Figure 2.

Bcl-2 acts intrinsically in neurons to support neuritogenesis and axon regeneration. (A–C) RGCs were isolated from wt (A), Bcl-xLtg (B), and Bcl-2tg (C) mice, incubated for 5 days, and stained with calcein. Surviving RGCs from Bcl-2tg mice extended longer axons than those from wt or Bcl-xLtg mice. (D–F) Percentage of surviving RGCs (D), percentage of surviving RGCs with axons longer than 3 body lengths (E), and average length of the longest axon from each RGC (F) (n=5 cultures/group). RGCs in Bcl-xLtg and Bcl-2tg mice had similar survival rates, but Bcl-xLtg RGCs had shorter neurites. (G) Western blot analysis of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL expression in stably transfected PC12 cells. (H, I) Percentage of surviving cells (H) and percentage of cells bearing neurites (I) (n=5 cultures/group). Bcl-xL- and Bcl-2-expressing PC12 cells had similar survival rates, but significantly fewer Bcl-xL-expressing cells had neurites. *P<0.01 versus wt, two-tailed t-test.

To determine if Bcl-2 has a general effect on neurite outgrowth, we generated PC12 cell lines stably transfected with Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL. PC12 cells differentiate and extend neurites upon stimulation with nerve growth factor (NGF) (50 ng/ml). Overexpression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL was confirmed by immunoblot analysis (Figure 2G). After treatment with staurosporine (Figure 2H) or serum withdrawal (not shown), the survival rate was significantly higher in cells expressing Bcl-xL or Bcl-2 than in control cells (Figure 2H). As in RGC cultures, however, expression of Bcl-xL did not enhance the ability of cells to extend neurites. At a subthreshold concentration of 1 ng/ml, NGF failed to stimulate neurite formation in control or Bcl-xL-expressing PC12 cells but induced robust neurite outgrowth in those expressing Bcl-2 (Figure 2I). Thus, Bcl-2 promotes neuritogenesis in the presence of growth-stimulating signals, although it does not itself stimulate neurite outgrowth. This effect is not a direct consequence of its antiapoptotic function, as expression of Bcl-xL supported neuronal survival without promoting the neuritogenic response.

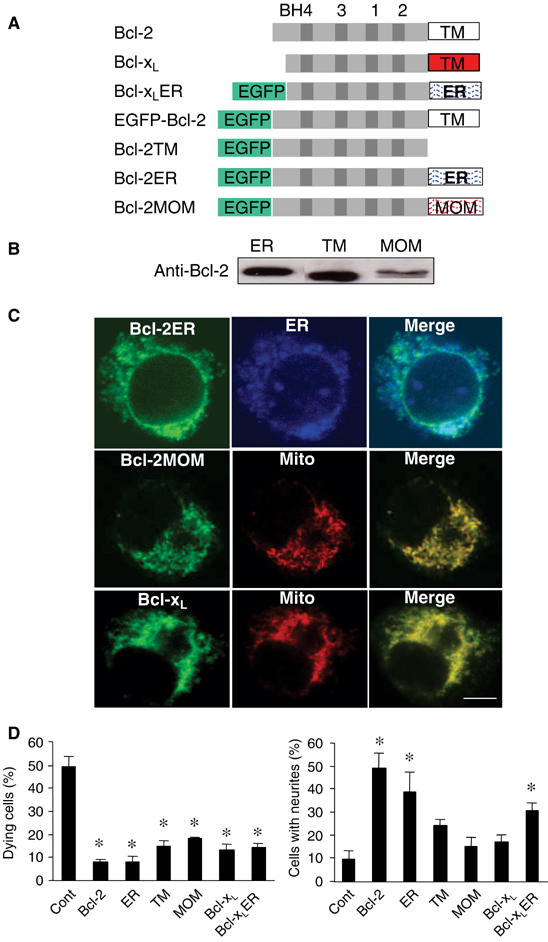

Bcl-2-mediated growth is ER-dependent

To define the molecular pathways by which Bcl-2 promotes the neuritogenic response, we took advantage of the distinct structures of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL. Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL share all four Bcl-2 homology domains (BH) but contain a distinct C-terminal, transmembrane (TM) hydrophobic helix that targets the proteins to specific subcellular locations. To determine if the subcellular localization of Bcl-2 is crucial for its neurite growth-promoting function, we generated Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL mutants or chimeric proteins. The TM domain of Bcl-2 was deleted (Bcl-2TM) or replaced with a membrane-anchoring domain containing either the mitochondrial outer member (MOM) (Bcl-2MOM) or ER (Bcl-2ER) targeting signal (Wang et al, 2001) (Figure 3A). Bcl-xL chimeric, in which its TM domain was replaced with ER targeting signal (Bcl-xLER), was also generated. These proteins were fused to the C-terminal end of enhanced green fluorescence protein (EGFP).

Figure 3.

The growth-promoting effect of Bcl-2 is ER-dependent. (A) Schematic of DNA structures of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Bcl-2 mutants. (B) Western blot analysis of PC12 cell lines stably transfected with Bcl-2ER, Bcl-2TM, and Bcl-2MOM. (C) Subcellular location of Bcl-2ER, Bcl-2MOM, and Bcl-xL shown by confocal microscopy. EGFP-Bcl-2ER (green) colocalizes with the ER marker calnexin (blue); EGFP-Bcl-2MOM and EGFP-Bcl-xL colocalize with the mitochondrial marker (Mito) cytochrome c (red). Scale bar, 4 μm. (D) Percentage of dying cells after treatment with staurosporine (left) and percentage that extended neurites (n=4 cultures/group). ER, Bcl-2ER; TM, Bcl-2TM; MOM, Bcl-2MOM. *P<0.05 versus wt, two-tailed t-test.

To compare the survival and growth effects of Bcl-2 targeted to different subcellular localizations, we generated PC12 cell lines stably transfected with constructs encoding the Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL mutants or chimeras. Protein expression was confirmed by immunoblot analysis (Figure 3B). As shown by confocal microscopy, normal Bcl-2 protein was found primarily in the ER (Kaufmann et al, 2003), while Bcl-2TM exhibited a diffused cytoplasmic cellular localization (Usuda et al, 2003) (not shown). Bcl-2ER colocalized specifically with an ER marker, and Bcl-2MOM and Bcl-xL with a mitochondrial marker (Figure 3C).

Treatment with staurosporine induced massive apoptosis in control PC12 cells, but not in cells expressing Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Bcl-xLER, or any of the Bcl-2 mutants (Figure 3D). However, cells expressing the Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL mutants differed in their ability to extend neurites. NGF (1 ng/ml) induced vigorous neurite outgrowth only in cells expressing Bcl-2 or Bcl-2ER (Figure 3D). Because a major difference between Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL is their subcellular localization, we then targeted Bcl-xL to the ER and compared its survival and growth effect with Bcl-2. Interestingly, Bcl-xLER exhibited similar growth-promoting activity as expression of Bcl-2 (Figure 3D). EGFP-Bcl-2 fusion protein displayed similar survival and neuritogenic activity as normal Bcl-2 (not shown). Thus, the ER localization is critical for the neurite growth activity of Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL.

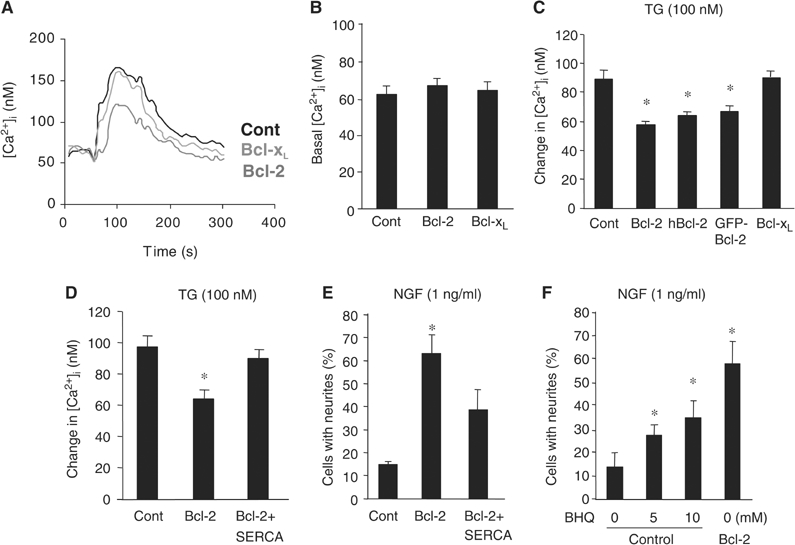

Bcl-2 regulates ER Ca2+ to promote neuritogenic response

To determine if Bcl-2 promotes neuritogenesis by regulating the Ca2+ content of the ER ([Ca2+]er), we used thapsigargin (TG), an inhibitor of the ER Ca2+-ATPase, to stimulate ER Ca2+ depletion. The peak level of [Ca2+]i reached upon TG addition was used as an indirect measure of the ER Ca2+ content. Control, Bcl-2-, and Bcl-xL-expressing PC12 cells had similar resting levels of [Ca2+]i (Figure 4A and B). TG resulted in a net release of ER Ca2+ and increased [Ca2+]i (Figure 4A and C). However, the increase in [Ca2+]i was markedly lower in Bcl-2-expressing cells than in control cells or cells expressing Bcl-xL, which resides in the mitochondria (Kaufmann et al, 2003). We corroborated this result in three different clones that were stably transfected with mouse, human, and EGFP fusion Bcl-2 genes (Figure 4B and C). This finding suggests that expression of Bcl-2, but not Bcl-xL, decreases the ER Ca2+ content of neurons.

Figure 4.

Bcl-2-, but not Bcl-xL-, expressing neurons display reduced ER Ca2+ content. (A–C) Representative trace (A) and quantitative analysis of basal (B) and TG-induced [Ca2+]i (C), measured by Fura-2, in PC12 cells expressing a control (Cont), Bcl-2, or Bcl-xL plasmid. Measurement of TG-induced Ca2+ change was carried out in the absence of extracellular Ca2+. (D, E) TG-induced [Ca2+]i (D) and NGF-induced neurite outgrowth (E) in control (Cont), Bcl-2-, or Bcl-2+SERCA2b-expressing PC12 cells (n=4 cultures/group). (F) NGF-induced neurite outgrowth in control and Bcl-2-expressing PC12 cells treated with 0–10 mM BHQ (n=4/group). *P<0.01 versus control, two-tailed t-test.

Bcl-2 has been proposed to decrease [Ca2+]er by downregulating the expression of the ER Ca2+ pump (SERCA) and thereby suppressing ER Ca2+ uptake (Dremina et al, 2004). We transfected Bcl-2-expressing cells with constructs encoding SERCA2b. While Bcl-2 expression alone reduced TG-induced [Ca2+]i (or [Ca2+]er) relative to that of control cells, expression of SERCA2b attenuated that reduction (Figure 4D) as well as neurite outgrowth from Bcl-2-expressing cells stimulated with 1 ng/ml NGF (Figure 4E). In contrast, blocking ER Ca2+ uptake mimicked the growth-promoting effect of Bcl-2. Decreasing ER Ca2+ uptake in control PC12 cells with 2,5′-di(terbutyl)-1,4,-benzohydroquinone (BHQ), an inhibitor of SERCA (Dolor et al, 1992), increased neurite outgrowth in the presence of 1 ng/ml NGF (Figure 4F), an effect similar to that achieved by overexpressing Bcl-2. These data suggest that reduction of ER Ca2+ uptake is essential and sufficient for Bcl-2-mediated neurite growth-promoting activity.

Bcl-2 regulates [Ca2+]er to enhance intracellular Ca2+ signaling

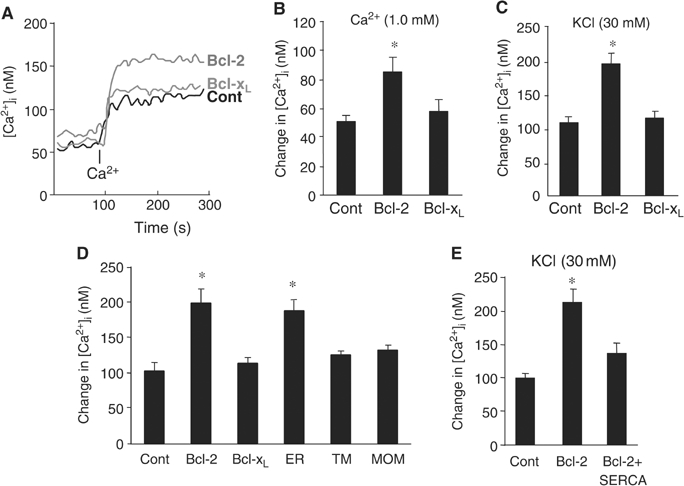

Neural injury often leads to an increase of extracellular Ca2+ and subsequently a surge of intracellular Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane. This injury-induced intracellular Ca2+ signaling is critical in the regulation of neurite outgrowth and nerve regeneration in lower vertebrates (Ziv and Spira, 1997). We hypothesized that, by reducing ER Ca2+ uptake, Bcl-2 enhances the injury- or stimuli-induced intracellular Ca2+ signaling and promotes neuritogenesis. To test this hypothesis, we added Ca2+ to cells maintained in a Ca2+-free medium to mimic the injury-induced increase of extracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]o) and the surge of [Ca2+]i or used KCl depolarization to induce intracellular Ca2+ influx. Addition of extracellular Ca2+ (Figure 5A) or KCl (not shown) triggered a transient increase of [Ca2+]i, followed by a sustained plateau. When stimulated with extracellular Ca2+ (Figure 5A and B) or KCl (Figure 5C), PC12 cells expressing Bcl-2 had a significantly larger elevation of [Ca2+]i than control or Bcl-xL-expressing cells, which correlated inversely with their ER Ca2+ content. These results suggest that expression of Bcl-2, but not Bcl-xL, enhances the intracellular Ca2+ response of neurons to nerve stimulation or injury.

Figure 5.

Bcl-2 expression enhances intracellular Ca2+ signaling by reducing ER Ca2+ uptake. (A–C) Representative trace (A) and quantitative analysis of extracellular Ca2+- (B) and KCl-induced changes in [Ca2+]i (C), measured by Fura-2 (n=4/group). PC12 cells stably transfected with control (Cont), Bcl-2, or Bcl-xL plasmids were incubated in Ca2+-free medium for over an hour; where indicated, Ca2+ (1.0 mM free extracellular Ca2+ final concentration) was added. Changes in [Ca2+]i were measured from its baseline to when the elevation of [Ca2+]i reached its peak. (D) Comparison of KCl-induced [Ca2+]i in cells expressing control (Cont), Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Bcl-2ER (ER), Bcl-2TM (TM), and Bcl-2MOM (MOM) genes (n⩾3/group). (E) Measurement of KCl-induced changes in [Ca2+]i in cells expressing a control, Bcl-2, or Bcl-2+SERCA2b plasmid. *P<0.01 versus control, two-tailed t-test.

Next, we compared the changes in [Ca2+]i after KCl depolarization in PC12 cells expressing Bcl-2 mutants or chimeras. KCl-induced elevation of [Ca2+]i in PC12 cells expressing Bcl-2 or Bcl-2ER was significantly larger than in control PC12 cells (Figure 5D). KCl-induced [Ca2+]i levels in cells expressing mutated Bcl-2 targeted to the cytoplasm (Bcl-2ΔTM) or mitochondria (Bcl-2MOM) were similar to that of control cells (Figure 5D). In addition, blocking ER Ca2+ uptake in Bcl-2-expressing cells by overexpressing SERCA2b prevented the decrease of [Ca2+]er and led to a KCl-induced elevation of [Ca2+]i comparable to that in control cells (Figure 5E). These results indicate that Bcl-2 resides in the ER and enhances the intracellular Ca2+ response of neurons to injury or stimuli by reducing ER Ca2+ uptake.

Bcl-2 activates CREB and Erk to stimulate neuritogenetic response

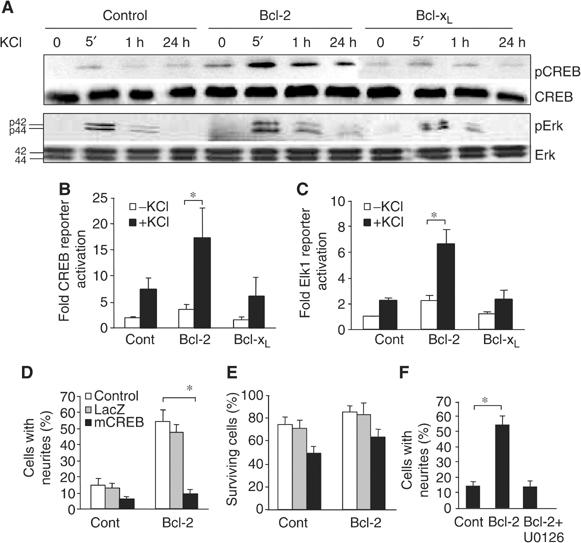

An emerging hypothesis suggests that Bcl-2 enhances the intracellular Ca2+ response to nerve injury and activates Ca2+-mediated signaling proteins, such as CREB and Erk, whose prolonged activation stimulates genes essential for neurite outgrowth (Ghosh and Greenberg, 1995; Dash et al, 1998; Lonze and Ginty, 2002). Thus, expression of Bcl-2, but not Bcl-xL, might promote a neuritogenic response by potentiating CREB and Erk activation after KCl depolarization or Ca2+ influx. In the absence of stimulation, phosphorylated CREB (pCREB) or pErk was not detected in PC12 cells (Figure 6A). KCl depolarization induced transient, low-level phosphorylation of CREB and Erk in control and Bcl-xL-expressing cells, but in Bcl-2-expressing cells, it induced pronounced and sustained activation of CREB and Erk that persisted for 24 h (Figure 6A). To confirm this, we assessed the transcriptional activities of CREB and Erk by measuring the expression of CREB- and Erk-dependent luciferase reporter genes. In the absence of stimulation, reporter gene expression was low in control, Bcl-2-, and Bcl-xL-expressing cells. Stimulation with KCl significantly upregulated the expression of CREB- and Erk-dependent reporter genes in Bcl-2-expressing cells but not in control or Bcl-xL-expressing cells (Figure 6B and C). Thus, Bcl-2 expression promotes and prolongs the activation of CREB and Erk induced by KCl depolarization or Ca2+ influx.

Figure 6.

Bcl-2 activates CREB and Erk to promote neuritogenic response. (A) Western blot analysis of time-dependent phosphorylation of CREB and Erk in PC12 cells expressing control, Bcl-2, or Bcl-xL plasmids treated with KCl (30 mM). Antibodies recognizing the unphosphorylated forms of CREB and Erk served as controls. (B, C) CREB-dependent (B) and Erk-dependent (C) reporter gene activities in stably transfected PC12 cells in the presence or absence of KCl (30 mM) (n⩾4/group). (D–F) Neurite outgrowth (D, F) and neuronal survival (E) in control (Cont) and Bcl-2-expressing cells (Bcl-2) incubated with 1 ng/ml NGF (n=4/group). Cultures were incubated in the absence (control) or presence of either a viral vector carrying a LacZ reporter gene or dominant-negative CREB (mCREB) (D, E) or the MEK inhibitor U0126 (100 nM) (F). *P<0.01, two-tailed t-test.

To determine if CREB plays a causal role in Bcl-2-mediated neuritogenic response, we blocked CREB activation by infecting cells with herpes simplex virus expressing a dominant-negative CREB (Dolor et al, 1992). Dominant-negative CREB prevented neurite outgrowth from Bcl-2-expressing cells in the presence of 1 ng/ml NGF without inducing significant cell death; infection with a control LacZ viral vector had no effect on neurite outgrowth or survival (Figure 6D and E). Similarly, suppressing the activity of Erk with the MAPK-specific inhibitor U0126 in Bcl-2-expressing cells blocked neurite outgrowth induced by 1 ng/ml NGF (Figure 6F). We conclude that Bcl-2 enhances intracellular Ca2+ signaling induced by an increase of intracellular Ca2+ influx and potentiates CREB and Erk activation to stimulate a neuritogenic response.

Bcl-2 activates CREB and Erk in vivo to support RGC axon regeneration

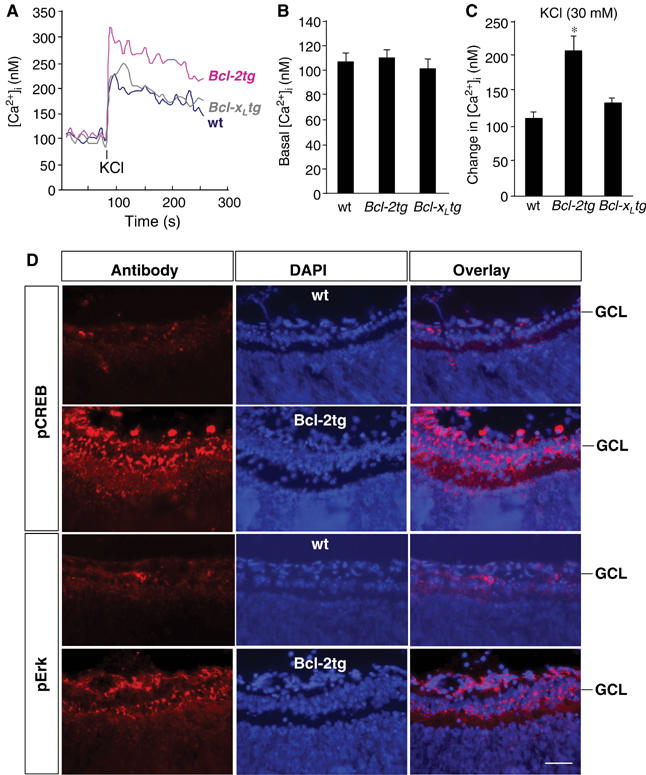

To determine if Bcl-2 supports RGC axon regeneration by a mechanism similar to that which promotes the neuritogenic response of PC12 cells, we examined KCl-induced intracellular Ca2+ responses in RGCs purified from wt, Bcl-2tg, and Bcl-xLtg mice. As in PC12 cells, overexpression of Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL in RGCs did not alter the basal [Ca2+]i (Figure 7A and B). However, only in Bcl-2tg RGCs was the KCl-induced increase in [Ca2+]i significantly greater than in wt controls (Figure 7A and C), correlating with the reduction in TG-induced [Ca2+]i (or [Ca2+]er) in Bcl-2-expressing RGCs (not shown). Thus, as in PC12 cells, overexpression of Bcl-2 in RGCs enhances the intracellular Ca2+ response after Ca2+ influx.

Figure 7.

Optic nerve injury in Bcl-2tg mice increases the intracellular Ca2+ response and activates CREB and Erk in RGCs. (A–C) Representative trace (A) and quantitative analysis of basal (B) and KCl-induced changes in [Ca2+]i (C), measured by Fura-2, in RGCs of wt, Bcl-2tg, and Bcl-xLtg mice (n⩾3/group). Changes in [Ca2+]i were measured from its baseline to when the elevation of [Ca2+]i reached its peak. Values are means±s.d. *P<0.01 versus wt, two-tailed t test. (D) Immunofluorescence staining for pCREB and pErk in retinal sections from adult wt and Bcl-2tg mice at day 1 after optic nerve crush. Scale bar, 50 μm.

To determine if the increased Ca2+ influx after axotomy in Bcl-2-expressing neurons leads to the activation of CREB and Erk in vivo, we assessed CREB and Erk phosphorylation in RGCs in P3 wt and Bcl-2tg mice. Before optic nerve injury, neither wt nor Bcl-2tg RGCs expressed pCREB or pErk (Herdegen et al, 1993) (not shown). At 24 h after injury, however, immunostaining demonstrated high levels of pCREB and pErk in RGCs only in Bcl-2tg mice (Figure 7D). Thus, overexpression of Bcl-2 in RGCs activates a signaling event similar to that which promotes neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells.

Discussion

This study shows that Bcl-2 reduced ER Ca2+ uptake in neurons, thereby increasing the intracellular Ca2+ response evoked by nerve injury or stimulation and activating CREB and Erk transcriptional programs that stimulate neuritogenesis and axon regeneration. Expression of Bcl-xL, a protein localized primarily to the mitochondria, did not affect the intracellular Ca2+ response or activate CREB and Erk. Thus, although it supports neuronal survival, Bcl-xL does not promote axon regeneration. This study uncovers an important mechanism by which neurons control the growth response toward injury and stimulation. These findings indicate that Bcl-2 and ER Ca2+ contents regulate not only cell survival but also intrinsic growth mechanisms of CNS axons.

Ca2+ signaling is essential for many cellular functions, including neurite outgrowth. The notion that transient intracellular Ca2+ response can regulate biological processes occurring at a much slower rate, such as neuritogenesis, is not without precedent. It has been reported that transient elevation of intracellular Ca2+ in neurons, induced by K+-depolarization or Ca2+ influx, is sufficient to activate CREB and Erk, and thus regulates synaptic plasticity and dendritic growth (Dolmetsch et al, 2001; Redmond et al, 2002). In lower vertebrates, localized and transient elevation of intracellular Ca2+ induced after neural injury is essential for the activation of signaling cascades that reinitiate nerve elongation and regeneration (Ziv and Spira, 1997; Spira et al, 2001). In the present study, we demonstrate that activation of CREB and Erk, which stimulates genes essential for neurite outgrowth and regeneration, is detected within 5 min of Ca2+ influx induced by K+-depolarization. Neurons use both extracellular and intracellular sources of Ca2+ to regulate Ca2+ signaling, but little has been reported about the mechanism and role of ER Ca2+ stores in neuronal function. Neurons have extensive ER networks that can contribute critically to Ca2+ dynamics by acting either as a source or as a sink of Ca2+ (Berridge, 1998). Emerging evidence suggests that neuronal ER Ca2+ stores have a profound influence in shaping the spatio-temporal complexity of Ca2+ signaling (Paschen, 2001; Rizzuto, 2001).

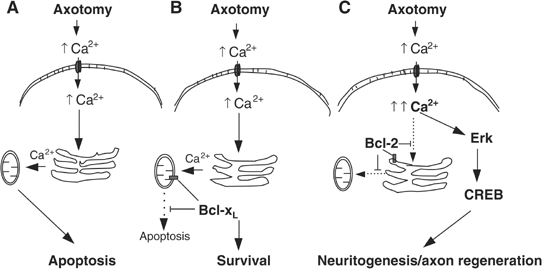

Our findings indicate that the ER Ca2+ store is a key player in the regulation of intracellular Ca2+ signaling in neurons after injury or stimulation and that Bcl-2 resides in the ER, controlling ER Ca2+ content and Ca2+ signaling. When neural injury induces a surge of [Ca2+]o and Ca2+ influx in wt mice, the Ca2+ is taken up by the neuronal ER via Ca2+ ATPase and is transferred to the mitochondria, where it initiates apoptosis (Goldberg and Barres, 2000) (Figure 8A). Expression of Bcl-xL in the mitochondria prevents mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and subsequent activation of the apoptotic signal, thereby supporting neuronal survival (Figure 8B). In contrast, Bcl-2 residing in the ER reduces ER Ca2+ uptake and storage, leading to an enhanced elevation of [Ca2+]i, which activates signaling cascades essential for neurite outgrowth and axon regeneration. Bcl-2 also supports the survival of neurons by preventing Ca2+ transfer from the ER to mitochondria (Figure 8C).

Figure 8.

Model of intracellular Ca2+ responses and subsequent signaling events in RGCs of wt, Bcl-xLtg, and Bcl-2tg mice. (A) Neural injury or axotomy results in an increase of extracellular Ca2+, a surge of Ca2+ influx, and elevation of [Ca2+]i. In neurons of wt mice, the excess intracellular Ca2+ is absorbed by the ER and translocated to the mitochondria, where it initiates apoptosis. (B) Bcl-xL expression, which is targeted to the mitochondria, prevents Ca2+-induced activation of the apoptotic signal and supports neuronal survival but does not affect ER Ca2+ uptake or the intracellular Ca2+ response to injury. (C) Expression of Bcl-2, however, is targeted primarily to the ER, where it reduces ER Ca2+ uptake and Ca2+ translocation to the mitochondria after axotomy, thereby preventing neuronal apoptosis. In addition, Bcl-2 reduces ER Ca2+ uptake, leading to greater elevation of [Ca2+]i after injury, thereby activating CREB and Erk and stimulating a neuritogenic response and axon regeneration.

The exact mechanism by which Bcl-2 regulates ER Ca2+ content remains unclear. Expression of Bcl-2 may decrease ER Ca2+ content by downregulating the expression of SERCA, thereby decreasing ER Ca2+ uptake, and by increasing ER Ca2+ permeability and release (Foyouzi-Youssefi et al, 2000). In any case, this study defines a new role for Bcl-2 and the ER Ca2+ store in regulating intrinsic mechanisms that influence the neuritogenic response of neurons.

It is well established that an increase in intracellular Ca2+ can activate CREB and Erk transcriptional programs that are essential for the regulation of neurite extension (Ghosh and Greenberg, 1995; Lonze and Ginty, 2002; Waltereit and Weller, 2003). CREB can be activated not only by an increase of [Ca2+]i (Ghosh and Greenberg, 1995; Lonze and Ginty, 2002), which stimulates Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinases to phosphorylate CREB (Waltereit and Weller, 2003), but also by cAMP and the MAPK/Erk pathway (Adams and Sweatt, 2002). Interestingly, increased levels of cAMP, which signals directly to CREB, enhance the intrinsic growth potential of CNS axons (Spencer and Filbin, 2004). In contrast, pCREB is not detected in postnatal RGCs of wt mice that lack the ability to regenerate axons, but is upregulated in RGCs of Bcl-2tg mice after injury. These results support the notion that CREB and Erk are dedicated signaling events required for axonal regeneration in the postnatal mammalian CNS.

Our study revealed an intriguing difference in the actions of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL and shows that neuronal survival and neurite outgrowth are independent neuronal activities. Overexpression of Bcl-xL supported only neuronal survival. Overexpression of Bcl-2, however, enhanced intracellular Ca2+ signaling, activated CREB and Erk, and supported both survival and axon/neurite growth. These dissimilarities can be explained, at least in part, by the differences in subcellular localization. Bcl-2 is found in the ER and Bcl-xL in the mitochondria (Kaufmann et al, 2003). Targeting Bcl-2 to the cytoplasm or the mitochondria prevented the effect of Bcl-2 on [Ca2+]er and reduced the intracellular Ca2+ response to injury or Ca2+ influx. As a result, CREB and Erk activation was reduced, and potentiation of the neuritogenic response was attenuated. Our studies therefore demonstrate that Bcl-2, but not Bcl-xL, serves a dual role by supporting both neuronal survival and axon elongation.

In summary, Bcl-2 resides in the ER, functioning through intracellular Ca2+ signaling and CREB- and Erk-mediated transcriptional programs, to regulate the intrinsic growth response of CNS neurons. Bcl-xL supports neuronal survival but does not play a major role in the growth of neurites. These observations suggest a novel mechanism through which neurons control their responses to extracellular signals. It may also provide new drug targets for CNS regeneration and repair.

Materials and methods

Animals

P2–P3 mouse pups resulting from the mating of C57Bl/6J wt females with Bcl-2tg or Bcl-xLtg males were used in this study. All experimental procedures and use and care of animals followed a protocol approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Schepens Eye Research Institute and Harvard Medical School.

Optic nerve surgery and anterograde labeling of axons

P3 mouse pups were anesthetized by hypothermia. The left optic nerve was exposed intraorbitally and crushed with fine surgical forceps for 5 s. The crush was performed about 1 mm from the posterior pole of the eyeball to avoid damaging the ophthalmic artery. To enable visualization of axons shortly after injury, the anterograde tracer CTB conjugated with rhodamine (2.5 μg/μl; List Biological Lab, Campbell, CA) was injected into the vitreous cavity immediately after injury. Mice were allowed to recover for 1–30 days before axon tracing.

Retina–brain slice coculture

Retina–brain slice cocultures were prepared as described (Chen et al, 1995). Briefly, mouse brains and retinas were dissected, and coronal brain slices containing the superior colliculus were prepared. Each retinal explant was placed to abut a brain slice on a six-well cell culture insert and cultured in neurobasal medium supplemented with B27 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After 4 days, the cultures were fixed, and crystals of 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbo-cyanine perchlorate (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) were placed onto each explant. The dye was allowed to diffuse for 2 weeks, and retinal axons that had grown into the brain slices were counted under a fluorescence microscope.

RGC isolation and culturing

RGCs were isolated with magnetic bead-conjugated Thy1.2 antibody and maintained in culture as described (Huang et al, 2003). Briefly, isolated RGCs were seeded in 24-well plates coated with poly-D-lysine (10 μg/ml; Sigma) and laminin (10 μg/ml; Sigma) and cultured in neurobasal medium supplemented with B27 and 100 U/ml penicillin–streptomycin (Invitrogen), as well as glutamine (2 mM), glutamate (25 μM), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (50 ng/ml), ciliary neurotrophic factor (10 ng/ml), forskolin (5ng/ml), and insulin (20 ng/ml) (all from Sigma).

Cell viability was determined with a live/dead assay (Molecular Probes). Cells were incubated with PBS containing calcein (10μg/ml) and ethidium D (5 μg/ml). In live cells, calcein is cleaved, yielding cytoplasmic green fluorescence. In dead cells, nucleic acids are labeled with ethidium D, yielding red fluorescence. Green cells (live), red (dead) cells, and cells bearing neurites were counted with a Nikon TE300 inverted fluorescence microscope equipped with fluorescence illumination.

Cell culture and transfections

The control PC12 cell line was purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Sigma) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 5% horse serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (all from Invitrogen). Stable transfection was performed with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocols. Plasmids pSSV-Bcl-2 and pSSV-Bcl-xL were gifts from Dr Stanley J Korsmeyer (Dana-Farbar Cancer Institute, Boston, MA). GFP-Bcl-2TM, GFP-Bcl-2MOM, and GFP-Bcl-2ER were provided by Dr Clark W Distelhorst (Comprehensive Cancer Center, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH) and SERCA2b was from Dr Marisa Brini (University of Padova, Padova, Italy). The reporter plasmids, MAPK-luciferase and CREB-luciferase, were from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). After transfection, cells were grown in 0.5 mg/ml geneticin (Invitrogen). For differentiation assays, cells were switched to a 1ow-serum (1%) culture medium and cultured in the presence or absence of NGF (1 ng/ml; Sigma). Cell processes longer than one cell body diameter were counted as neurites. BHQ was from Sigma, BAPTA from Molecular Probes, and U0126 from Calbiochem. For luciferase assays, cells were transfected with pFR-Luc (Stratagene) and pFA-ELK1 (Stratagene) or pFA-CREB (Stratagene) and pSV-β-Gal. After 24 h, cells were treated with 1 ng/ml NGF for 6 h and lysed, and luciferase activity was determined with a luciferase assay kit (Promega) and a tube luminometer according to standard protocols (Strack, 2002).

Fura-2/AM measurements of [Ca2+]i

For measurement of [Ca2+]i, cells (1 × 107/ml) were suspended in a standard buffer (25 mM HEPES, 1 mM Na2HPO4, 125 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 5 mM glucose) containing 4 μM Fura-2/AM (Molecular Probes) and 250 μM sulfinpyrazone (Sigma) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min in the presence or absence of extracellular Ca2+. The cells were then washed with standard buffer, and [Ca2+]i was measured with a fluorescence spectrometer (LS-5B, Perkin-Elmer, Beaconfield, UK), using an excitation ratio of 340/380 and an emission wavelength of 492 nm. [Ca2+]i was calculated according to the following equation: [Ca2+]i=Kd(Sf2/Sb2)[(R−Rmin)/(Rmax−R)]. The apparent dissociation constant (Kd) for Fura-2 used in all calibrations was 224 nM. Rmax was obtained in the presence of 10 μm ionomycin and 20 mM CaCl2, while Rmin was obtained in the presence of 10 μm ionomycin and 20 mM EGTA. Sf2 and Sb2 were fluorescence intensities measured at 380 nm in Ca2+-free and Ca2+-saturated solutions, respectively.

Western blot

Cells were collected and lysed, and 60 μg of protein of each lysate was separated by SDS–PAGE (12%). The protein was electrophoretically blotted onto nitrocellulose membrane, incubated with primary antibody (1:1000) and then with peroxidase-conjugated second antibody (1:10 000), and detected by chemiluminescence (probes) assay. Antibodies against Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibodies against Erk1/2, pErk1/2, CREB, and pCREB were from Cell Signaling Technologies (Beverly, MA).

Immunofluorescence stain and histology

Mice were anesthetized and perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The eyeballs were removed, cut into14 μm sections with a cryostat, and reacted with primary antibodies against pErk or pCREB and then with fluorescein- or rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibodies. After staining with 4′,6-diamindino-2-phenyindole (2 mg/ml; Sigma) to reveal cell nuclei, retinal sections were examined by fluorescence and confocal (Leica) microscopy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Korsmeyer for pSSV-Bcl-2 and pSSV-Bcl-xL plasmids, Dr Distelhorst for GFF-Bcl-2, GFP-Bcl-2TM, GFP-Bcl-2MOM, and GFP-Bcl-2ER plasmids, and Dr Brini for SERCA2b plasmid. This work was supported by grants from NIH/NEI EY012983 and Department of Army to DFC.

References

- Adams JP, Sweatt JD (2002) Molecular psychology: roles for the ERK MAP kinase cascade in memory. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 42: 135–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ (1998) Neuronal calcium signaling. Neuron 21: 13–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen DF, Jhaveri S, Schneider GE (1995) Intrinsic changes in developing retinal neurons result in regenerative failure of their axons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 7287–7291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen DF, Schneider GE, Martinou JC, Tonegawa S (1997) Bcl-2 promotes regeneration of severed axons in mammalian CNS. Nature 385: 434–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho K-S, Yang L, Lu B, Ma HF, Huang X, Pekny M, Chen DF (2005) Re-establishing the regenerative potential of central nervous system axons in postnatal mice. J Cell Sci (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dash PK, Tian LM, Moore AN (1998) Sequestration of cAMP response element-binding proteins by transcription factor decoys causes collateral elaboration of regenerating Aplysia motor neuron axons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 8339–8344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolmetsch RE, Pajvani U, Fife K, Spotts JM, Greenberg ME (2001) Signaling to the nucleus by an L-type calcium channel–calmodulin complex through the MAP kinase pathway. Science 294: 333–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolor RJ, Hurwitz LM, Mirza Z, Strauss HC, Whorton AR (1992) Regulation of extracellular calcium entry in endothelial cells: role of intracellular calcium pool. Am J Physiol 262: C171–C181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dremina ES, Sharov VS, Kumar K, Zaidi A, Michaelis EK, Schoneich C (2004) Anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 interacts with and destabilizes the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA). Biochem J 383: 361–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari D, Pinton P, Szabadkai G, Chami M, Campanella M, Pozzan T, Rizzuto R (2002) Endoplasmic reticulum, Bcl-2 and Ca2+ handling in apoptosis. Cell Calcium 32: 413–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foyouzi-Youssefi R, Arnaudeau S, Borner C, Kelley WL, Tschopp J, Lew DP, Demaurex N, Krause KH (2000) Bcl-2 decreases the free Ca2+ concentration within the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 5723–5728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Greenberg ME (1995) Calcium signaling in neurons: molecular mechanisms and cellular consequences. Science 268: 239–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JL, Barres BA (2000) The relationship between neuronal survival and regeneration. Annu Rev Neurosci 23: 579–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JL, Klassen MP, Hua Y, Barres BA (2002) Amacrine-signaled loss of intrinsic axon growth ability by retinal ganglion cells. Science 296: 1860–1864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Garcia M, Garcia I, Ding L, O'Shea S, Boise LH, Thompson CB, Nunez G (1995) Bcl-x is expressed in embryonic and postnatal neural tissues and functions to prevent neuronal cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 4304–4308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X, Spitzer NC (1995) Distinct aspects of neuronal differentiation encoded by frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ transients. Nature 375: 784–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X, Spitzer NC (1997) Breaking the code: regulation of neuronal differentiation by spontaneous calcium transients. Dev Neurosci 19: 33–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdegen T, Bastmeyer M, Bahr M, Stuermer C, Bravo R, Zimmermann M (1993) Expression of JUN, KROX, and CREB transcription factors in goldfish and rat retinal ganglion cells following optic nerve lesion is related to axonal sprouting. J Neurobiol 24: 528–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton M, Middleton G, Davies AM (1997) Bcl-2 influences axonal growth rate in embryonic sensory neurons. Curr Biol 7: 798–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Wu DY, Chen G, Manji H, Chen DF (2003) Support of retinal ganglion cell survival and axon regeneration by lithium through a Bcl-2-dependent mechanism. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 44: 347–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann T, Schlipf S, Sanz J, Neubert K, Stein R, Borner C (2003) Characterization of the signal that directs Bcl-x(L), but not Bcl-2, to the mitochondrial outer membrane. J Cell Biol 160: 53–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin LA, Schlamp CL, Spieldoch RL, Geszvain KM, Nickells RW (1997) Identification of the bcl-2 family of genes in the rat retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 38: 2545–2553 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonze BE, Ginty DD (2002) Function and regulation of CREB family transcription factors in the nervous system. Neuron 35: 605–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonze BE, Riccio A, Cohen S, Ginty DD (2002) Apoptosis, axonal growth defects, and degeneration of peripheral neurons in mice lacking CREB. Neuron 34: 371–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinou JC, Dubois-Dauphin M, Staple JK, Rodriguez I, Frankowski H, Missotten M, Albertini P, Talabot D, Catsicas S, Pietra C, Huarte J (1994) Overexpression of BCL-2 in transgenic mice protects neurons from naturally occurring cell death and experimental ischemia. Neuron 13: 1017–1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merry DE, Veis DJ, Hickey WF, Korsmeyer SJ (1994) bcl-2 protein expression is widespread in the developing nervous system and retained in the adult PNS. Development 120: 301–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsadanian AS, Cheng Y, Keller-Peck CR, Holtzman DM, Snider WD (1998) Bcl-xL is an antiapoptotic regulator for postnatal CNS neurons. J Neurosci 18: 1009–1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschen W (2001) Dependence of vital cell function on endoplasmic reticulum calcium levels: implications for the mechanisms underlying neuronal cell injury in different pathological states. Cell Calcium 29: 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinton P, Ferrari D, Rapizzi E, Di Virgilio F, Pozzan T, Rizzuto R (2001) The Ca2+ concentration of the endoplasmic reticulum is a key determinant of ceramide-induced apoptosis: significance for the molecular mechanism of Bcl-2 action. EMBO J 20: 2690–2701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond L, Kashani AH, Ghosh A (2002) Calcium regulation of dendritic growth via CaM kinase IV and CREB-mediated transcription. Neuron 34: 999–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuto R (2001) Intracellular Ca(2+) pools in neuronal signalling. Curr Opin Neurobiol 11: 306–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudner J, Jendrossek V, Belka C (2002) New insights in the role of Bcl-2 and the endoplasmic reticulum. Apoptosis 7: 441–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer T, Filbin MT (2004) A role for cAMP in regeneration of the adult mammalian CNS. J Anat 204: 49–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spira ME, Oren R, Dormann A, Ilouz N, Lev S (2001) Calcium, protease activation, and cytoskeleton remodeling underlie growth cone formation and neuronal regeneration. Cell Mol Neurobiol 21: 591–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strack S (2002) Overexpression of the protein phosphatase 2A regulatory subunit Bgamma promotes neuronal differentiation by activating the MAP kinase (MAPK) cascade. J Biol Chem 277: 41525–41532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usuda J, Chiu SM, Murphy ES, Lam M, Nieminen AL, Oleinick NL (2003) Domain-dependent photodamage to Bcl-2. A membrane anchorage region is needed to form the target of phthalocyanine photosensitization. J Biol Chem 278: 2021–2029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltereit R, Weller M (2003) Signaling from cAMP/PKA to MAPK and synaptic plasticity. Mol Neurobiol 27: 99–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang NS, Unkila MT, Reineks EZ, Distelhorst CW (2001) Transient expression of wild-type or mitochondrially targeted Bcl-2 induces apoptosis, whereas transient expression of endoplasmic reticulum-targeted Bcl-2 is protective against Bax-induced cell death. J Biol Chem 276: 44117–44128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziv NE, Spira ME (1997) Localized and transient elevations of intracellular Ca2+ induce the dedifferentiation of axonal segments into growth cones. J Neurosci 17: 3568–3579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]