Abstract

Introduction

The most common classification of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is based on electrocardiographic findings and distinguishes ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). Both types of AMI differ concerning their epidemiology, clinical approach and early outcomes. Ticagrelor is a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor, constituting the first-line treatment for STEMI and NSTEMI. According to available data, STEMI may be associated with lower plasma concentration of ticagrelor in the first hours of AMI, but currently there are no studies directly comparing ticagrelor pharmacokinetics or antiplatelet effect in patients with STEMI versus NSTEMI.

Methods and analysis

The PINPOINT study is a phase IV, single-centre, investigator-initiated, prospective, observational study designed to compare the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ticagrelor in patients with STEMI and NSTEMI assigned to the invasive strategy of treatment. Based on an internal pilot study, the trial is expected to include at least 23 patients with each AMI type. All subjects will receive a 180 mg loading dose of ticagrelor. The primary end point of the study is the area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC(0–6)) for ticagrelor during the first 6 hours after the loading dose. Secondary end points include various pharmacokinetic features of ticagrelor and its active metabolite (AR-C124910XX), and evaluation of platelet reactivity by the vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein assay and multiple electrode aggregometry. Blood samples for the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic assessment will be obtained at pretreatment, 30 min, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 12 hours post-ticagrelor loading dose.

Ethics and dissemination

The study received approval from the Local Ethics Committee (Komisja Bioetyczna Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika w Toruniu przy Collegium Medicum im. Ludwika Rydygiera w Bydgoszczy; approval reference number KB 617/2015). The study results will be disseminated through conference presentations and peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

NCT02602444; Pre-results.

Keywords: NSTEMI, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, STEMI, ticagrelor

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to provide prospective head-to-head comparison of ticagrelor pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in patients with STEMI versus NSTEMI assigned to the invasive strategy.

Plasma concentrations of ticagrelor and its active metabolite will be assessed with liquid chromatography mass spectrometry coupled with tandem mass spectrometry.

The antiplatelet effect of ticagrelor will be evaluated with two commonly recognised methods: the vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein assay and multiple electrode aggregometry.

As this is a purely pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic study, it is likely that the anticipated trial population will not be sufficient to evaluate clinical end points or perform subgroup analyses.

Patients receiving morphine are not excluded from the study, which may result in differences in the baseline characteristics between the examined groups, but this will enable us to obtain data in a real-world setting and will not create an artificially selected population.

Introduction

Background

The routine classification of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) applied in everyday practice to facilitate the choice of treatment strategy is based on electrocardiographic findings, and distinguishes ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI).1

In STEMI, usually caused by acute total occlusion of a coronary artery, immediate primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the mainstay of treatment.2 In contrast to STEMI, the therapeutic strategy for NSTEMI and its timing depend on the risk stratification.3 Complementary to coronary revascularisation, dual antiplatelet therapy, consisting of aspirin on top of a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor, remains the cornerstone of pharmacological treatment in both forms of AMI.4 5 Inadequate platelet inhibition during treatment with P2Y12 receptor inhibitors, defined as high platelet reactivity (HPR), is an important risk factor for stent thrombosis and may be associated with increased mortality.6 7 Therefore, effective and rapid suppression of platelet activation is pivotal in patients with AMI treated with PCI.

Ticagrelor is a reversible, oral P2Y12 receptor inhibitor, recommended as the first-line treatment for STEMI and NSTEMI.8 9 It is characterised by linear pharmacokinetics and does not require hepatic metabolism to exert its antiplatelet action. Nevertheless, it is extensively metabolised by hepatic CYP3A enzymes.10 AR-C124910XX is the major active metabolite of ticagrelor and it produces similar antiplatelet effect as the parent drug. After oral ingestion of ticagrelor, AR-C124910XX quickly appears in the circulation and reaches approximately one-third of ticagrelor plasma concentration.10 The remaining nine of identified ticagrelor metabolites appear to be clinically insignificant. Ticagrelor-induced and AR-C124910XX-induced platelet inhibition is proportional to their plasma concentrations.11

Rationale

Impact of numerous clinical features on plasma concentration and pharmacodynamics of ticagrelor has been inspected. Genetic effects, gender, age, concomitant food intake or preloading with clopidogrel have at most minimal influence on the pharmacokinetics of ticagrelor and no clinically significant differences in the degree of platelet inhibition have been reported regarding these factors.12–15 On the other hand, morphine administration has been shown to affect ticagrelor pharmacokinetic profile, as well as its antiplatelet effect, in healthy volunteers and in patients with AMI.16–18 The negative impact of morphine on the intestinal absorption has been proposed as an explanation for the observed interactions, while no evidence was found in support of the influence of morphine on conversion of ticagrelor into its active metabolite.18 19 Importantly, STEMI, as opposed to NSTEMI, has also been postulated to affect ticagrelor pharmacokinetics. Franchi et al20 reported that ticagrelor exposure is attenuated and delayed in patients with STEMI receiving morphine and opioid-naive STEMI subjects. This may indicate that morphine is not exclusively responsible for the lower concentration of ticagrelor observed in patients with STEMI when compared with healthy volunteers or patients with stable coronary artery disease.15 20 21 Moreover, subanalyses of two pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic trials suggest that STEMI in comparison with NSTEMI is independently associated with lower plasma concentration of ticagrelor.18 22

Although mechanistic studies are lacking, diminished plasma concentration of ticagrelor after the loading dose (LD) observed in patients with STEMI is most likely related to impaired bioavailability of ticagrelor in this setting. Adrenergic activation, decreased cardiac output, haemodynamic instability and vasoconstriction of peripheral arteries, more frequently observed in patients with STEMI, lead to selective shunting of blood flow to maintain sufficient perfusion of vital organs.23 24 This chain of events eventually may cause intestinal hypoperfusion, which together with emesis could potentially explain the poorer absorption of oral agents, including ticagrelor, seen in patients with STEMI. The course of NSTEMI is usually less dramatic, but it remains unknown whether significant impairment of ticagrelor absorption occurs in these patients.

Even though ticagrelor shows potent and prompt platelet inhibition, it still fails to provide a desired antiplatelet effect during the first hours after the LD in all patients with STEMI. At 2 hours after ticagrelor LD up to 60% of patients with STEMI may still suffer from inadequate platelet inhibition.18 20 25 Data on the proportion of patients with NSTEMI loaded with ticagrelor who remain at risk of HPR during the peri-PCI period are sparse.

The Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) study has shown a remarkable reduction in cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality among acute coronary syndrome patients treated with ticagrelor compared with those receiving clopidogrel. This superiority was demonstrated in most of the analysed subgroups, including patients with STEMI and NSTEMI.26 Nevertheless, epidemiology, clinical approach and early outcomes differ between patients with these two types of AMI, while recommended dosing regimens of ticagrelor are identical in both clinical settings.2 3 27–30

Currently, there are no data directly comparing ticagrelor pharmacokinetics in the mentioned types of AMI, while patients with STEMI may be at risk of having lower ticagrelor plasma concentration in the most crucial time during the early hours of AMI treatment.18 22 Similarly, potential differences in ticagrelor antiplatelet action between STEMI and NSTEMI have not been defined yet. Therefore, we decided to explore whether the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ticagrelor differ between patients with STEMI and NSTEMI. The Comparison of Ticagrelor Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics in STEMI and NSTEMI Patients (PINPOINT) study is expected to provide a valuable insight into our knowledge regarding the modern treatment of patients with AMI.

Methods and analysis

Study objectives

The PINPOINT study is designed to compare the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ticagrelor and its active metabolite (AR-C124910XX) in patients with STEMI and NSTEMI assigned to the invasive treatment.

Study design

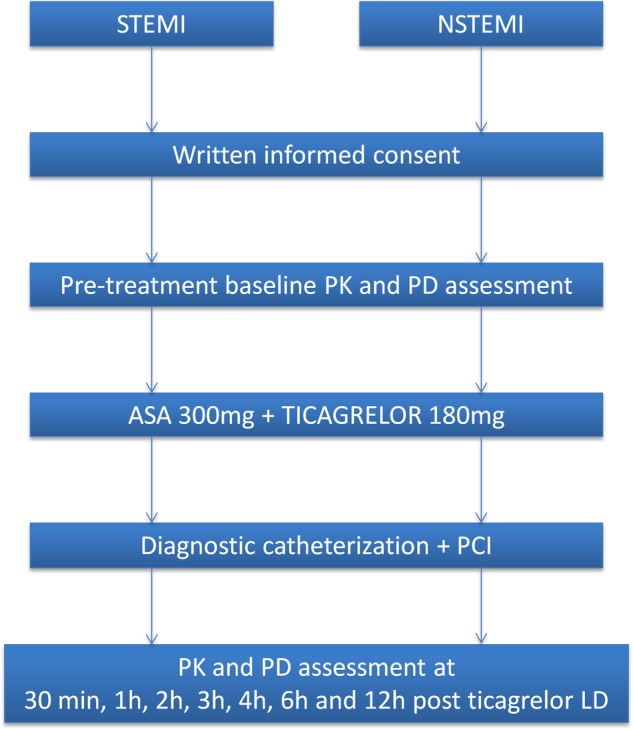

The PINPOINT study is a phase IV, single-centre, investigator-initiated, prospective, observational, pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic study. After admission to the study centre (Cardiology Clinic, Dr A. Jurasz University Hospital, Bydgoszcz, Poland) and confirmation of STEMI or NSTEMI diagnosis according to the Third Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction,1 patients will be screened for eligibility for the study. Before any study-specific procedure, each patient will provide a written informed consent to participate in the trial. All included patients will immediately receive orally a 300 mg LD of plain aspirin in integral tablets and a 180 mg LD of ticagrelor in integral tablets with 250 mL of tap water. Subsequently, all patients will promptly undergo coronary angiography followed by PCI, if required. Blood samples for pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic assessment will be drawn at eight predefined time points according to the blood sampling schedule already used at our site in a previous study (pretreatment baseline, 30 min, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 12 hours post-ticagrelor LD—as shown in figure 1).31

Figure 1.

The PINPOINT study schema. ASA, aspirin; LD, loading dose; NSTEMI, non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PD, pharmacodynamics; PK, pharmacokinetics; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

All enrolled patients with finally unconfirmed initial diagnosis of AMI will be excluded from the primary analysis. Patients qualified for urgent coronary artery bypass surgery within the blood sampling period also will not be included in the analysis. All study participants not receiving PCI will be reported.

Study population

The study population will include consecutive men or non-pregnant women, P2Y12 receptor inhibitor-naive patients with STEMI and NSTEMI, assigned to the invasive strategy. Full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria is presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria of the PINPOINT study

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

NSTEMI, non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

Blood sample processing

Blood samples for the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluation will be obtained using a venous catheter (18G) inserted into a forearm vein at eight prespecified time points (before ticagrelor LD, 30 min, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 12 hours post-ticagrelor LD—figure 1). Venous blood for the pharmacokinetic evaluation will be collected into lithium-heparin vacuum test tubes. Immediately after collection each sample will be placed on dry ice and transferred to the central laboratory. Subsequently, within 20 min from collection, blood specimens will be centrifuged at 1500 g for 12 min at 4°C. Within 10 min postcentrifugation, obtained plasma samples will be stored at temperature below −60°C until analysed.

Venous blood for the assessment of pharmacodynamics with the vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) assay and multiple electrode aggregometry (MEA) will be collected into trisodium citrate and hirudin vacuum test tubes, respectively. The first 3–5 mL of blood will be discarded to avoid spontaneous platelet activation. The pharmacodynamic analysis will be performed for each sample within 24 hours and 60 min from blood collection for VASP and MEA, respectively.

Assessment of pharmacokinetics

Plasma concentration of ticagrelor and AR-C124910XX in samples obtained at all eight predefined time points (figure 1) will be evaluated using liquid chromatography mass spectrometry coupled with tandem mass spectrometry, as previously described.18 32

Briefly, ticagrelor and AR-C124910XX will be extracted using 4°C methanol solution containing [2H7]ticagrelor internal standard (TM-ALS-13–226-P1, ALSACHIM, France), while calibration curves will be obtained using ticagrelor (SVI-ALS-13-146, ALSACHIM, France) and AR-C124910XX (TM-ALS-13-193-P1, ALSACHIM, France) standards. Analysis will be performed using the Shimadzu UPLC Nexera X2 system consisting of LC-30AD pumps, SIL-30AC Autosampler, CTO-20AC column oven, FCV-20-AH2 valve unit, and DGU-20A5R degasser coupled with Shimadzu 8030 ESI-QqQ mass spectrometer. Lower limits of quantification are 4.69 ng/mL for ticagrelor and AR-C124910XX.

Assessment of pharmacodynamics

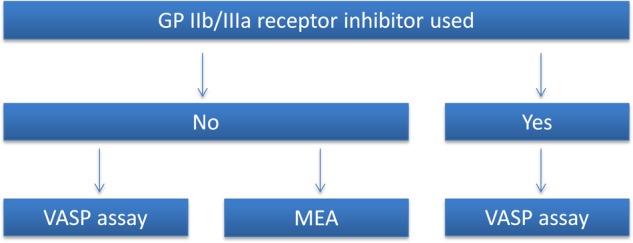

Platelet VASP assay (Biocytex, Marseille, France) will be applied to all study participants at all predefined time points. MEA (Roche Diagnostics International, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) will be used at all predefined time points (figure 1) for all study participants with the exception of those treated with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (GP IIb/IIIa) receptor inhibitors as this therapy may affect the results of platelet reactivity assessment performed with MEA (figure 2). Pharmacodynamic assessment with VASP and MEA will be performed according to the manufacturers' instructions, as previously described.33 34 HPR will be defined as platelet reactivity index (PRI) >50% and area under the aggregation curve >46 units, when evaluated with VASP and MEA, respectively.35

Figure 2.

Platelet reactivity evaluation schedule for the PINPOINT study. GP IIb/IIIa, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa; MEA, multiple electrode aggregometry; VASP, vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein.

Treatment

All patients included in the trial will be treated according to the current European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines.2 3 36 Standard therapy will include aspirin, ticagrelor, β-blockers, statins and ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers, if not contraindicated. Morphine will be used at the discretion of the ambulance staff and the attending physician. The type of implanted stent and choice of the access site for coronary invasive procedure (radial or femoral) will be at the discretion of the operator. During the periprocedural period, all study participants will receive unfractionated heparin in body weight adjusted dose according to the ESC recommendations.2 3 36 Administration of GP IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors will be restricted only to bailout situations. Interventional cardiologists will be encouraged to use manual thrombectomy in case of visible thrombus.

Study end points

The primary end point of the study is area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC(0–6)) for ticagrelor during the first 6 hours after the LD of ticagrelor. Secondary end points include AUC(0–6) for AR-C124910XX, area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC(0–12)) for ticagrelor during the first 12 hours after the LD of ticagrelor, AUC(0–12) for AR-C124910XX, maximum concentration (Cmax) of ticagrelor and AR-C124910XX, time to maximum concentration (tmax) for ticagrelor and AR-C124910XX, PRI assessed by the VASP assay, platelet reactivity assessed by MEA, percentage of patients with HPR after ticagrelor LD assessed with the VASP assay and MEA, time to reach platelet reactivity below the cut-off value for HPR evaluated with the VASP assay and MEA.

Statistical analysis

The continuous variables in both study groups will be compared using the t-test for normally distributed values as assessed by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Otherwise, the Mann-Whitney U test will be used. Proportions will be compared using the χ2 test when appropriate. A single linear regression analysis will be performed and will be followed by a multiple regression analysis if any variables are found to significantly affect the study primary end point. Pharmacokinetic calculations and plots will be made using dedicated software.

Determination of sample size

Since there is no reference study comparing the pharmacokinetics of ticagrelor in patients with STEMI and NSTEMI, we decided to perform an internal pilot study of at least 15 patients with each type of AMI for estimating the final sample size. Eventually, the pilot study population comprised of 45 patients (15 with NSTEMI and 30 with STEMI). It included all participants consecutively entering the trial until the number of patients in the smaller group (NSTEMI) reached the prespecified minimal threshold.

The means and SDs of AUC(0–6) for ticagrelor in the first 30 patients with STEMI and 15 patients with NSTEMI were 2382±2282 and 6406±4082 ng*h/mL, respectively. Based on these results and assuming a two-sided α value of 0.05, we calculated, using the t-test for independent variables, that enrolment of at least 23 patients in each study arm would provide a 95% power to demonstrate a significant difference in AUC(0–6) for ticagrelor between patients with different types of myocardial infarction.

Study limitations

Several limitations of our study have to be acknowledged. First, it is likely that the anticipated trial population will not be sufficient to evaluate clinical end points or perform subgroup analyses. Second, patients receiving morphine are not excluded from the study, which may result in differences in the baseline characteristics between the examined groups. Third, morphine is used at the discretion of the paramedics or the attending physicians, although we encourage the medical staff to administer a standardised dose of 5 mg intravenously, if required in any potential or actual study participant. On the other hand, even though it may be perceived as a limitation, this will enable us to obtain data in a real-world setting and will not create an artificially selected population.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics

The study will be conducted in accordance with the principles contained in the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Each patient will provide a written informed consent for participation in the study.

Safety

The following safety end points will be recorded during the blood sampling period: all-cause death, recurrent myocardial infarction according to the Third Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction, stroke, and transient ischaemic attack according to definitions used in the PLATO trial, definite or probable stent thrombosis according to the Academic Research Consortium criteria, minor and major bleedings according to the Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) criteria, dyspnoea adverse events according to criteria used in the PLATO trial, bradyarrhythmic events according to criteria used in the PLATO trial.

Present status

The approval of the Local Ethics Committee was obtained on 29 September 2015. On 9 November 2015 the PINPOINT study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02602444). The first patient was enrolled in November 2015. The baseline characteristics of patients included in the pilot study are presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients included in the internal pilot study

| STEMI (n=30) | NSTEMI (n=15) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 62.3±8.8 | 63.9±9.7 | 0.51 |

| Age ≥70 years | 6 (20.0%) | 4 (26.7%) | 0.89 |

| Female | 6 (20.0%) | 5 (33.3%) | 0.53 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.6±4.1 | 27.8±4.2 | 0.76 |

| Hypertension | 10 (33.3%) | 10 (66.7%) | 0.036 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (20.0%) | 2 (13.3%) | 0.89 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 27 (90.0%) | 14 (93.3%) | 0.85 |

| Current smoker | 13 (43.3%) | 5 (33.3%) | 0.52 |

| Prior MI | 0 | 2 (13.3%) | n/a |

| Prior PCI | 2 (6.7%) | 3 (20.0%) | 0.4 |

| Prior CABG | 0 | 0 | n/a |

| Congestive heart failure | 0 | 0 | n/a |

| Non-haemorrhagic stroke | 0 | 0 | n/a |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 1 (3.3%) | 2 (13.3%) | 0.21 |

| Chronic renal disease | 0 | 0 | n/a |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 0 | 0 | n/a |

| Gout | 1 (3.3%) | 1 (6.7%) | n/a |

| Morphine use during current MI | 17 (56.7%) | 6 (40.0%) | 0.29 |

Data are presented as mean±SD or number (%).

BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass surgery; MI, myocardial infarction; n/a, not available; NSTEMI, non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

Dissemination of results

Results of the PINPOINT study will be disseminated through conference presentations and peer-reviewed journals. The results will also be available through the study record website at ClinicalTrials.gov.

Summary

It is unknown whether ticagrelor pharmacokinetic profile and its antiplatelet effect are uniform in patients with STEMI and NSTEMI, who are regarded in number of aspects as two distinct populations. The PINPOINT trial is expected to be the first study to elucidate whether STEMI is associated with poorer absorption and subsequently weaker antiplatelet action of ticagrelor in comparison with NSTEMI.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JK and PA conceived the study. JK and PA wrote the study protocol with consultation from MO, JS, KO, KB, MKr, GS, MM and MKo. Subsequently JK, PA, MO, JS, KO, KB, MKr, GS, MM and MKo revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The study is funded by Collegium Medicum of Nicolaus Copernicus University and did not receive any external funding.

Competing interests: JK received a consulting fee from AstraZeneca. MK received honoraria for lectures from AstraZeneca. All other authors have reported no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper.

Ethics approval: The study received ethics approval by the Local Ethics Committee: Komisja Bioetyczna Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika w Toruniu przy Collegium Medicum im. Ludwika Rydygiera w Bydgoszczy (study approval reference number: KB 617/2015).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: As the PINPOINT study is still ongoing and data are still being collected, currently no additional data are available besides given in the submitted study protocol.

References

- 1.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2551–67. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, et al. ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2569–619. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2016;37:267–315. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adamski P, Adamska U, Ostrowska M, et al. New directions for pharmacotherapy in the treatment of acute coronary syndrome. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2016;17:2291–306. 10.1080/14656566.2016.1241234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kubica J. The optimal antiplatelet treatment in an emergency setting. Folia Med Copernicana 2014;2:73–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aradi D, Kirtane A, Bonello L, et al. Bleeding and stent thrombosis on P2Y12-inhibitors: collaborative analysis on the role of platelet reactivity for risk stratification after percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur Heart J 2015;36:1762–71. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winter MP, Koziński M, Kubica J, et al. Personalized antiplatelet therapy with P2Y12 receptor inhibitors: benefits and pitfalls. Postepy Kardiol Interwencyjnej 2015;11:259–80. 10.5114/pwki.2015.55596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Navarese EP, Buffon A, Kozinski M, et al. A critical overview on ticagrelor in acute coronary syndromes. QJM 2013;106:105–15. 10.1093/qjmed/hcs187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adamski P, Koziński M, Ostrowska M, et al. Overview of pleiotropic effects of platelet P2Y12 receptor inhibitors. Thromb Haemost 2014;112:224–42. 10.1160/TH13-11-0915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teng R, Oliver S, Hayes MA, et al. Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of ticagrelor in healthy subjects. Drug Metab Dispos 2010;38:1514–21. 10.1124/dmd.110.032250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Husted S, Emanuelsson H, Heptinstall S, et al. Pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, and safety of the oral reversible P2Y12 antagonist AZD6140 with aspirin in patients with atherosclerosis: a double-blind comparison to clopidogrel with aspirin. Eur Heart J 2006;27:1038–47. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varenhorst C, Eriksson N, Johansson Å, et al. Effect of genetic variations on ticagrelor plasma levels and clinical outcomes. Eur Heart J 2015;36:1901–12. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teng R, Mitchell P, Butler K. Effect of age and gender on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a single ticagrelor dose in healthy individuals. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2012;68:1175–82. 10.1007/s00228-012-1227-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teng R, Mitchell PD, Butler K. Lack of significant food effect on the pharmacokinetics of ticagrelor in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharm Ther 2012;37:464–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2011.01307.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Husted SE, Storey RF, Bliden K, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ticagrelor in patients with stable coronary artery disease: results from the ONSET-OFFSET and RESPOND studies. Clin Pharmacokinet 2012;51:397–409. 10.2165/11599830-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hobl EL, Reiter B, Schoergenhofer C, et al. Morphine decreases ticagrelor concentrations but not its antiplatelet effects: a randomized trial in healthy volunteers. Eur J Clin Invest 2016;46:7–14. 10.1111/eci.12550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kubica J, Kubica A, Jilma B, et al. Impact of morphine on antiplatelet effects of oral P2Y12 receptor inhibitors. Int J Cardiol 2016;215:201–8. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.04.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kubica J, Adamski P, Ostrowska M, et al. Morphine delays and attenuates ticagrelor exposure and action in patients with myocardial infarction: the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled IMPRESSION trial. Eur Heart J 2016;37:245–52. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adamski P, Ostrowska M, Sroka WD, et al. Does morphine administration affect ticagrelor conversion to its active metabolite in patients with acute myocardial infarction? A sub-analysis of the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled IMPRESSION trial. Folia Med Copernicana 2015;3:100–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franchi F, Rollini F, Cho JR, et al. Impact of escalating loading dose regimens of ticagrelor in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention: results of a prospective randomized pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic investigation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2015;8:1457–67. 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teng R, Butler K. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, tolerability and safety of single ascending doses of ticagrelor, a reversibly binding oral P2Y(12) receptor antagonist, in healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2010;66:487–96. 10.1007/s00228-009-0778-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koziński M, Ostrowska M, Adamski P, et al. Which platelet function test best reflects the in vivo plasma concentrations of ticagrelor and its active metabolite? The HARMONIC study. Thromb Haemost 2016;116:1140–9. 10.1160/TH16-07-0535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heestermans AA, van Werkum JW, Taubert D, et al. Impaired bioavailability of clopidogrel in patients with a ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Thromb Res 2008;122:776–81. 10.1016/j.thromres.2008.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kubica J, Kozinski M, Navarese EP, et al. Cangrelor: an emerging therapeutic option for patients with coronary artery disease. Curr Med Res Opin 2014;30:813–28. 10.1185/03007995.2014.880050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parodi G, Valenti R, Bellandi B, et al. Comparison of prasugrel and ticagrelor loading doses in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients: RAPID (Rapid Activity of Platelet Inhibitor Drugs) primary PCI study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:1601–6. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1045–57. 10.1056/NEJMoa0904327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McManus DD, Gore J, Yarzebski J, et al. Recent trends in the incidence, treatment, and outcomes of patients with STEMI and NSTEMI. Am J Med 2011;124:40–7. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.07.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gierlotka M, Zdrojewski T, Wojtyniak B, et al. Incidence, treatment, in-hospital mortality and one-year outcomes of acute myocardial infarction in Poland in 2009–2012-nationwide AMI-PL database. Kardiol Pol 2015;73:142–58. 10.5603/KP.a2014.0213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mandelzweig L, Battler A, Boyko V, et al. The second Euro Heart Survey on acute coronary syndromes: characteristics, treatment, and outcome of patients with ACS in Europe and the Mediterranean basin in 2004. Eur Heart J 2006;27:2285–93. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terkelsen CJ, Lassen JF, Norgaard BL, et al. Mortality rates in patients with ST-elevation vs. non-ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction: observations from an unselected cohort. Eur Heart J 2005;26:18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kubica J, Adamski P, Ostrowska M, et al. Influence of Morphine on Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Ticagrelor in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction (IMPRESSION): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2015;16:198 10.1186/s13063-015-0724-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sillén H, Cook M, Davis P. Determination of ticagrelor and two metabolites in plasma samples by liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2010;878:2299–306. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2010.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kubica A, Kasprzak M, Siller-Matula J, et al. Time-related changes in determinants of antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel in patients after myocardial infarction. Eur J Pharmacol 2014;742:47–54. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koziński M, Obońska K, Stankowska K, et al. Prasugrel overcomes high on-clopidogrel platelet reactivity in the acute phase of acute coronary syndrome and maintains its antiplatelet potency at 30-day follow-up. Cardiol J 2014;21:547–56. 10.5603/CJ.a2014.0026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aradi D, Storey RF, Komócsi A, et al. Expert position paper on the role of platelet function testing in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur Heart J 2014;35: 209–15. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, et al. , Authors/Task Force members. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J 2014;35:2541–619. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.