Abstract

Introduction

Restaurant food is widely consumed by children and is associated with poor diet quality. Although many restaurants have made voluntary commitments to improve the nutritional quality of children's menus, it is unclear whether this has led to meaningful changes.

Methods

Nutrients in children's menu items (n=4,016) from 45 chain restaurants were extracted from the nutrition information database MenuStat. Bootstrapped mixed linear models estimated changes in mean calories, saturated fat, and sodium in children's menu items between 2012 and 2013, 2014, and 2015. Changes in nutrient content of these items over time were compared among restaurants participating in the Kids LiveWell initiative and non-participating restaurants. Types of available children's beverages were also examined. Data were analyzed in 2016.

Results

There was a significant increase in mean beverage calories from 2012 to 2013 (6, 95% CI=0.8, 10.6) and from 2012 to 2014 (11, 95% CI=3.7, 18.3), but no change between 2012 and 2015, and no differences in nutrient content of other items over time. Restaurants participating in Kids LiveWell reduced entrée calories between 2012 and 2013 (−24, 95% CI= −40.4, −7.2) and between 2012 and 2014 (−40, 95% CI= −68.1, −11.4) and increased side dish calories between 2012 and 2015 (49, 95% CI=4.6, 92.7) versus non-participating restaurants. Sugar-sweetened beverages consistently constituted 80% of children's beverages, with soda declining and flavored milks increasing between 2012 and 2015.

Conclusions

Results suggest little progress toward improving nutrition in children's menu items. Efforts are needed to engage restaurants in offering healthful children's meals.

Introduction

From 1977 to 2006, energy from restaurant sources increased from 3% to 18% of energy intake among children aged 2–18 years.1 In 2011–2012, more than one third of children and adolescents consumed fast food each day.2 Among children, greater consumption of restaurant food is associated with higher intake of calories from added sugar and solid fats, as well as poorer diet quality.3,4 National data indicate that 35% of added sugars and solid fats consumed by children aged >2 years come from fast-food restaurants. Sugar-sweetened beverages, dairy-based desserts, French fries, and pizza contribute the bulk of these sugars and solid fats.3 Among children aged 2–11 years, eating at fast-food and full-service restaurants is associated with higher daily energy, saturated fat, sugar, regular soda, and sugar-sweetened beverage intake.4

Although there are currently no mandatory nutrition requirements for children's meals in chain restaurants, the restaurant industry has made voluntary commitments to improve the dietary quality of children's menus. In July 2011, the National Restaurant Association launched a voluntary program called Kids LiveWell, which aimed to increase the number of nutritious menu items available to children. By 2015, more than 150 restaurant chains with 42,000 locations were participating.5 Additionally, individual restaurant chains have made voluntary commitments to improving kids' meals outside of the scope of Kids LiveWell. Between 2011 and 2013, McDonald's replaced French fries and soda in Happy Meals with fruit and low-fat milk.6 Between 2013 and 2015, large national chains, including Applebee's, Subway, Chipotle, Arby's, Panera Bread, Wendy's, and Burger King, announced they would remove soda as the default choice on children's menus.7,8

Although these voluntary steps to improve children's meals are promising, cross-sectional studies of children's menus in restaurants have found that few options meet guidelines for a healthful diet, such as those put forth by the National School Lunch Program9 or the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.10,11 A recent study of children's entrées and side dishes in 29 chain restaurants found that in 2014, one third of main dishes at fast-food restaurants and half of main dishes at full-service restaurants exceeded levels of calories, fat, saturated fat, and sodium recommended by the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.12 The nutrient content of children's beverages and desserts—two of the four largest contributors to added sugars and solid fats in children's restaurant food—were not assessed. Further, no recent studies have assessed whether changes in nutritional quality of restaurant menu items have occurred since the start of programs like Kids LiveWell and other voluntary restaurant commitments.

To address gaps in the research, this study examined trends in nutrient content of 4,016 beverages, entrées, side dishes, and desserts offered on children's menus in a sample of 45 of the nation's top 100 fast-food, fast-casual, and full-service restaurant chains between 2012 and 2015 to assess whether the nutritional quality of children's restaurant meals has improved during a time when several voluntary restaurant initiatives were implemented. This study also assessed whether these changes differed between restaurants participating in the National Restaurant Association's Kids LiveWell Initiative and non-participating restaurants.

Methods

Data Sample

Data were obtained from MenuStat (menustat.org)—a census of nutrition data from websites of the nation's largest restaurant chains, identified by U.S. sales.13 Several published studies have used this database to examine trends in nutritional quality of menu items at restaurants over time.14–16 A description of MenuStat methods is published.17 The sample of restaurant chains used in this study is a balanced panel; all chains offering children's items in each year from 2012 to 2015 were included (n=45), with children's items designated as any item with “kid,” “child,” or “children” appearing in the menu item or its description. Characteristics of restaurants were extracted from restaurants websites.14 Restaurant chains were “national” if they were located in all U.S. census regions (n=26); otherwise, they were “regional” (n=19). Chains were “full service” if they offered table service (n=16; e.g., Applebee's); “fast casual” if they offered at least two of the following: non-disposable utensils, onsite food preparation, no table service, or commitment to higher-quality or fresh ingredients or sustainability (n=6; e.g., Chipotle); and, otherwise, were “fast food” (n=23; e.g., Burger King).

Children's menu items from these 45 chains were the sample included in this study. Calories (kcal), sodium (mg), and saturated fat (g), were available for most items from 2012 to 2015. Some items could not be included because of limited information. Fountain beverages or items listing a range of nutrient data for various combinations (e.g., tacos with a choice of toppings) were added as separate items if descriptions could be matched to nutrient data from MenuStat or archived restaurant websites; otherwise, these items were excluded (n=50). After exclusions, 152 (3.7%) items were missing information about calories (n=68), sodium (n=33), or saturated fat (n=119). Missing data were imputed based on the following order of preference:

obtaining nutrient data directly from restaurants (n=46);

searching product or restaurant website archives from the same month and year as MenuStat data collection (n=44);

calculating nutrient data from an alternate portion size of the same product description (n=3);

searching the U.S. Department of Agriculture Standard Reference Database18 (n=12); or

using the last observation carried forward (n=20).

Menu items missing data for any nutrient that could not be imputed (n=27) were excluded. Additionally, if an item was the sole item in its menu category within a restaurant (e.g., if a restaurant offered only one dessert), a variance could not be calculated and the item was excluded (n=43).

The final data set included 4,016 beverages (n=1,886), entrées (n=1,378), side dishes (n=531), and desserts (n=221) (mutually exclusive categories created by MenuStat staff) available in 45 U.S. chain restaurants between 2012 and 2015 (Appendix Table 1, available online).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed in 2016. A linear model with random intercepts to allow for correlation between items within restaurant chains was used to calculate:

predicted mean calories in children's beverages and predicted mean calories, saturated fat, and sodium in children's entrées, side dishes, and desserts in 2012; and

difference in mean calories in children's beverages and in mean calories, saturated fat, and sodium in children's entrées, side dishes, and desserts between 2012 and 2013, 2014, and 2015.

The main independent variable was a year indicator (2012, 2013, 2014, or 2015), and covariates included indicators for whether a restaurant was national, fast food, fast casual, or full service. Even after log transformation, the distribution of beverage calories did not follow a standard normal distribution. Therefore, linear models were cluster bootstrapped with 500 repetitions to compute the SEs of the regression coefficient estimates from their empirical distributions. The cluster bootstrap provides unbiased estimates of SEs and does not impose a normal distribution on the data.19

In a second set of regressions, an indicator representing participation in Kids LiveWell was added to the previous model with interactions between the participation indicator and year dummies to assess the difference in changes in nutrient content of children's menu items over time among restaurants participating in Kids LiveWell and non-participating restaurants. Restaurants joining Kids LiveWell between its launch in July 2011 and January 2015 were identified via the program's website.5

Trends in children's beverages were examined in more detail. Beverages were categorized into mutually exclusive groups: sugar-sweetened beverages (> 5 kcal/item, not described as “100% juice” or white milk), low-calorie beverages (≤5 kcal/item and not described as “unsweetened”), unsweetened beverages (≤5 kcal/item and described as “unsweetened”), 100% juice (described as “100% juice”), and white milk (unflavored). Five was chosen as the threshold for “low-calorie” items based on recommendations from the Institute of Medicine Task Force on Nutrition Standards for Foods in Schools, which states that beverages sold in schools, other than 100% juice or milk, should contain <5 kcal/portion as packaged, meaning <5 kcal/item.20,21 Flavored milks were classified as sugar sweetened, based on healthy beverage standards that have been previously implemented in large public school districts.22,23 Most (87%) beverages in this category contained >100 kcal/item. Sugar-sweetened beverages were further divided into mutually exclusive categories: soda (carbonated beverages), fruit drinks (excludes “100% juice”), flavored milk, and other sweetened beverages (e.g., sport drinks, smoothies, sweetened teas). Tests for equality of proportions were used to determine whether proportions of beverages within each category differed between 2012 and 2013, 2014, and 2015. All analyses were conducted using Stata, version 13.

Results

Table 1 shows predicted mean calories, sodium, and saturated fat in children's beverages, entrées, side dishes, and desserts in 2012 and changes between 2012 and 2013, 2014, and 2015. On average, beverages, entrées, side dishes, and desserts contained 139 kcal (SE=5.6), 362 kcal (SE=8.8), 157 kcal (SE=10.4), and 360 kcal (SE=22.0), respectively. Entrées, side dishes, and desserts contained 794 mg (SE=21.0), 231 mg (SE=23.5), and 159 mg (SE=13.1) of sodium, and 6.1 g (SE=0.3), 1.7 g (SE=0.2), and 10.5 g (SE=0.9) of saturated fat, respectively. Between 2012 and 2014, there were small but significant increases in beverage calories, which increased by 6 kcal (95% CI=0.8, 10.6) from 2012 to 2013 and 11 kcal (95% CI=3.7,18.3) from 2012 to 2014. There was no significant change in beverage calories between 2012 and 2015, and no changes in calories, sodium, or saturated fat in other food categories at any time point between 2012 and 2015.

Table 1. Mean Per-Item Nutrients in Children's Menu Items in 2012 and Changes From 2012 to 2015.

| Nutrients | Beverage | Entréea | Side dishb | Dessert |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012, M (SE) | ||||

| Calories (kcal) | 139 (5.6) | 362 (8.8) | 157 (10.4) | 360 (22.0) |

| Sodium (mg) | – | 794 (21.0) | 231 (23.5) | 159 (13.1) |

| Saturated fat (g) | – | 6.1 (0.3) | 1.7 (0.2) | 10.5 (0.9) |

| Change, 2012–2013, M (95% CI) | ||||

| Calories (kcal) | 6 (0.8, 10.6)* | −8 (−15.4, 0.1) | −5 (−19.6, 10.0) | 3 (−15.0, 21.2) |

| Sodium (mg) | – | −14 (−35.2, 7.0) | −9 (−56.6, 39.2) | 10 (−0.7, 20.8) |

| Saturated fat (g) | – | −0.1 (−0.3, 0.1) | −0.1 (−0.4, 0.2) | 0.0 (−0.9, 0.9) |

| Change, 2012–2014, M (95% CI) | ||||

| Calories (kcal) | 11 (3.7, 18.3)** | −2 (−16.3, 11.3) | 6 (−13.6, 25.1) | −2 (−24.9, 20.9) |

| Sodium (mg) | – | 5 (−33.4, 42.8) | 33 (−20.4, 86.3) | 8 (−2.7, 18.9) |

| Saturated fat (g) | – | 0.2 (−0.3, 0.6) | −0.1 (−0.5, 0.3) | −0.2 (−1.2, 0.9) |

| Change, 2012–2015, M (95% CI) | ||||

| Calories (kcal) | 6 (−1.4, 14.2) | −1 (−17.0, 14.6) | −6 (−25.7, 13.6) | −10 (−32.5, 13.0) |

| Sodium (mg) | – | −13 (−54.6, 29.5) | 11 (−41.1, 63.6) | 5 (−7.0, 17.2) |

| Saturated fat (g) | – | 0.2 (−0.3, 0.8) | −0.4 (−0.8, 0.0) | −0.5 (−1.6, 0.5) |

Note: Changes in mean per-item calories, sodium, and saturated fat adjusted for whether a restaurant chain is national or not, and restaurant type (fast food, full service, fast-casual). Random intercepts for restaurant were included to account for clustering between items within restaurant chains. Coefficients and SEs are bootstrapped estimates. Boldface indicates statistical significance (

p<0.05;

p<0.01).

Includes burgers, entrées, pizza, salads, sandwiches, and soups not categorized as appetizers or side dishes.

Includes appetizers and sides, fried potatoes, and baked goods (i.e., bread, rolls, and biscuits).

Table 2 shows differences in calories, sodium, and saturated fat in children's menu items in 2012 and changes between 2012 and subsequent years among restaurants participating in Kids LiveWell (n=15) and non-participating restaurants (n=30). Participating restaurants significantly reduced entrée calories between 2012 and 2013 (−24, 95% CI= −40.4, −7.2) and between 2012 and 2014 (−40, 95% CI= −68.1, −11.4) compared with non-participating restaurants, but differences did not persist from 2012 to 2015. Participating restaurants showed a trend toward increasing calories in children's side dishes across all time periods, although differences between participating and non-participating restaurants were only statistically significant between 2012 and 2015 (49, 95% CI=4.6, 92.7), and this was largely driven by a reduction in calories among non-participating restaurants. There were no differences between participating and non-participating restaurants with regard to calories in children's beverages or desserts, or with respect to sodium or saturated fat in any menu category.

Table 2. Difference in Mean Per-Item Nutrients in Children's Menu Items From 2012-2015 Among U.S. Chain Restaurants Participating in Kids LiveWell as of January 2015 and Non-Participating Restaurants.

| Variable | Beverage | Entréea | Side dishb | Dessert |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restaurants participating in Kids LiveWell | ||||

| No. of restaurants | 14 | 15 | 14 | 8 |

| No. of children's menu items | 890 | 639 | 321 | 152 |

| 2012, M (SD) | ||||

| Calories (kcal) | 143 (10.2) | 373 (14.0) | 156 (14.9) | 350 (21.3) |

| Sodium (mg) | – | 796 (30.9) | 252 (34.8) | 158 (13.5) |

| Saturated fat (g) | – | 6.1 (0.4) | 1.6 (0.3) | 9.3 (0.6) |

| Change, 2012–2013, M (95% CI) | ||||

| Calories (kcal) | 3 (−4.0, 10.4) | −21 (−35.6, −5.9)** | 3 (−21.9, 27.2) | −2 (−22.0, 18.5) |

| Sodium (mg) | – | −30 (−70.0, 9.6) | −7 (−79.1, 65.7) | 11 (−1.8, 23.2) |

| Saturated fat (g) | – | −0.4 (−0.7,0.0)* | 0.0 (−0.5, 0.5) | −0.2 (−1.0, 0.5) |

| Change, 2012–2014, M (95% CI) | ||||

| Calories (kcal) | 13 (−0.1, 25.4) | −24 (−49.2, 1.9) | 24 (−7.6, 55.6) | −3 (−31.0, 25.0) |

| Sodium (mg) | – | −21 (−89.1, 47.3) | 53 (−31.4, 136.4) | 6 (−2.7, 15.4) |

| Saturated fat (g) | – | 0.2 (−0.5, 0.8) | 0.2 (−0.4, 0.8) | −0.2 (−1.2, 0.9) |

| Change, 2012–2015, M (95% CI) | ||||

| Calories (kcal) | 14 (0.3, 27.1)* | −12 (−39.2, 15.4) | 17 (−12.2, 45.5) | −7 (−34.4, 21.5) |

| Sodium (mg) | – | −24 (−95.1, 46.7) | 31 (−48.8, 110.2) | 6 (−5.3, 17.1) |

| Saturated fat (g) | – | 0.5 (−0.2, 1.2) | 0.1 (−0.4, 0.6) | −0.4 (−1.3, 0.6) |

| Restaurants not participating in Kids LiveWell | ||||

| No. of restaurants | 26 | 25 | 19 | 7 |

| No. of children's menu items | 996 | 739 | 210 | 69 |

| 2012, M (SE) | ||||

| Calories (kcal) | 134 (6.1) | 349 (9.8) | 162 (16.0) | 353 (33.1) |

| Sodium (mg) | – | 788 (26.8) | 214 (27.6) | 151 (21.1) |

| Saturated fat (g) | – | 6.0 (0.3) | 1.8 (0.4) | 11.0 (1.7) |

| Change, 2012–2013, M (95% CI) | ||||

| Calories (kcal) | 7 (0.9, 13.7)* | 3 (−4.2, 10.3) | −12 (−24.9, 0.2) | 12 (−30.2, 54.6) |

| Sodium (mg) | – | −1 (−24.0, 22.4) | −13 (−50.1, 23.1) | 9 (−14.1, 31.4) |

| Saturated fat (g) | – | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.4) | −0.1 (−0.3, 0.1) | 0.4 (−1.9, 2.7) |

| Change, 2012–2014, M (95% CI) | ||||

| Calories (kcal) | 9 (1.6, 16.3)* | 16 (3.7, 28.5)* | −16 (−39.8, 8.5) | 2 (−43.5, 46.7) |

| Sodium (mg) | – | 27 (−8.1, 62.3) | 3 (−41.1, 47.1) | 14 (−17.1, 46.0) |

| Saturated fat (g) | – | 0.2 (−0.4, 0.7) | −0.4 (−1.0, 0.2) | −0.3 (−2.9, 2.3) |

| Change, 2012–2015, M (95% CI) | ||||

| Calories (kcal) | −1 (−8.7, 7.4) | 8 (−9.8, 24.8) | −32 (−64.0, 0.10) | −15 (−58.1, 27.5) |

| Sodium (mg) | – | −3 (−49.9, 43.1) | −13 (−71.4, 44.9) | 6 (−26.7, 38.9) |

| Saturated fat (g) | – | 0.0 (−0.7, 0.7) | -0.9 (−1.7, −0.1)* | −0.8 (−3.6, 1.9) |

| Difference in difference | ||||

| Change, 2012–2013, M (95% CI) | ||||

| Calories (kcal) | −4 (−13.3, 5.2) | −24 (−40.4, −7.2)** | 15 (−12.7, 42.7) | −14 (−59.7, 31.8) |

| Sodium (mg) | – | −29 (−76.0, 17.2) | 7 (−71.6, 85.1) | 2 (−23.5, 27.6) |

| Saturated fat (g) | – | −0.5 (−0.9, −0.1)* | 0.1 (−0.4, 0.6) | −0.6 (−3.0, 1.8) |

| Change, 2012–2014, M (95% CI) | ||||

| Calories (kcal) | 4 (−10.2, 17.6) | −40 (−68.1, −11.4)** | 40 (−1.3, 80.6) | −5 (−56.8, 47.6) |

| Sodium (mg) | – | −48 (−126.7, 30.6) | 49 (−42.7, 141.7) | −8 (−39.7, 23.5) |

| Saturated fat (g) | – | 0.0 (−0.9, 0.9) | 0.6 (−0.3, 1.4) | 0.1 (−2.6, 2.8) |

| Change, 2012–2015, M (95% CI) | ||||

| Calories (kcal) | 14 (−1.0, 29.6) | −19 (−50.6, 11.8) | 49 (4.6, 92.7)* | 9 (−41.6, 59.2) |

| Sodium (mg) | – | −21 (−106.2, 64.6) | 44 (−57.1, 144.9) | 0 (−34.7, 34.2) |

| Saturated fat (g) | – | 0.4 (−0.5, 1.4) | 0.9 (−0.1, 1.9) | 0.5 (−2.3, 3.3) |

Note: Changes in mean per-item calories, sodium, and saturated fat adjusted for whether a restaurant chain is national or not, and restaurant type (fast food, full service, fast casual). Random intercepts for restaurant were included to account for correlation between items within restaurant chains. Coefficients and SEs are bootstrapped estimates. Boldface indicates statistical significance

p<0.05

p<0.01

Includes burgers, entrées, pizza, salads, sandwiches, and soups not categorized as appetizers or side dishes.

Includes appetizers and sides, fried potatoes, and baked goods (i.e., bread, rolls, and biscuits).

No., number.

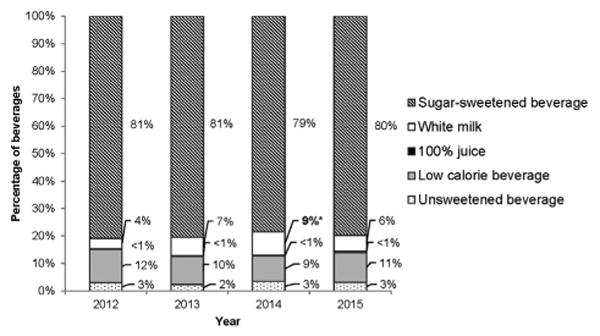

Figure 1 shows the percentage of children's beverages in each category across time. Sugar-sweetened beverages constituted the largest percentage of beverages in all years, making up 79%–81% of beverages.

Figure 1.

Types of children's beverages available in 45 U.S. chain restaurants in 2012-2015.

Note: Figure shows the percentage of beverages (n=1,886) offered on children's menus in 45 U.S. national chain restaurants in 2012-2015 that were sugar-sweetened beverages, white milk, 100% juice, low-calorie beverages, or unsweetened beverages. Based on recommendations from the Institute of Medicine Task Force on Nutrition Standards for Foods in Schools, sugar-sweetened beverages were items containing >5 calories/item and not described as “100%juice” or white milk.18,19 Low-calorie beverages were items containing ≤5 calories/item and not described as “unsweetened.”

*Statistically significant change from 2012 (p<0.05).

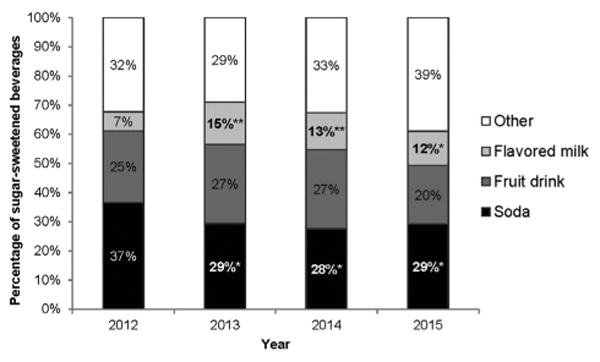

Within sugar-sweetened beverages, the percentage of options that were regular sodas declined from 2012 to 2015, dropping from 37% in 2012 to 29% in 2015 (p=0.032) (Figure 2). The percentage of flavored milks nearly doubled in this time period, rising from 7% of sugar-sweetened beverages in 2012 to 12% in 2015 (p=0.014).

Figure 2.

Types of children's sugar-sweetened beverages available in 45 U.S. chain restaurants in 2012–2015.

Note: Figure shows the percentage of sugar-sweetened beverages (n=1,507) offered in 45 U.S. national chain restaurants in 2012–2015 that were soda, fruit drinks, flavored milks, or other sugar-sweetened beverages. *Statistically significant change from 2012 (p<0.05); **statistically significant change from 2012 (p<0.01).

Discussion

There have been no substantial changes in calories, sodium, or saturated fat in children's menu items across multiple years, despite at least 45% of the restaurant sample publically committing to improving kids' meals between 2011 and 2015. There was a significant increase in mean beverage calories between 2012 and 2013 and 2014, but it was very small and there was no difference when comparing 2012 with 2015. Although restaurants participating in Kids LiveWell reduced calories in entrées between 2012 and 2013 and 2014 compared with non-participating restaurants, these changes did not persist between 2012 and 2015. Although the availability of soda on menus declined over time, this did not change availability of sugar-sweetened beverages, which consistently constituted nearly 80% of beverages. Flavored milks replaced sodas that were removed from children's menus.

Results from this study are similar to findings from Deierlein and colleagues,12 who examined nutritional differences in children's entrées and side dishes available for sale in 29 of the top 50 chain restaurants in 2010 and 2014. Consistent with current findings, the authors reported no significant differences in calories, sodium, or saturated fat in children's main dishes or side dishes offered at fast-food restaurants from 2010 to 2014. The only significant finding was a decrease in calories (−46, p<0.05) and milligrams of sodium (−128, p<0.05) among side dishes offered in sit-down restaurants in 2014 compared with 2010. Differences between study findings may have resulted from the difference in restaurants included in the sample (29 of the top 50 versus 45 of the top 100 in this study), or difference in assessed time period (2010 and 2014 versus 2012-2015 in this study).

The findings from this study are in contrast to a 2013 report from Center for Science in the Public Interest, which concluded that restaurants were offering healthier meal combinations. That study compared all possible combinations of children's meals offered in 34 of the top 50 restaurants in 2008 and 2012 and found that the percentage of meals meeting the Guidelines for Responsible Food Marketing to Children, which apply standards for calories, sodium, and saturated fat from the Dietary Guidelines for Americans24 and Institute of Medicine Dietary Reference Intakes,25 increased from 1% in 2008 to 3% in 2012.26 In addition, the proportion of meals meeting the calorie and sodium standards doubled between 2008 and 2012, increasing from 7% to 14% and 15% to 34%, respectively. The difference in findings might be due to different time periods being analyzed (2008 compared with 2012 versus 2012-2015 for the present study) or the way menu items were assessed (all possible combinations versus individual menu items in this study).

If a meal was ordered for a child in 2015 containing an average beverage, entrée, side dish, and dessert, it would contain 1,007 kcal, which is nearly twice the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Recommended Dietary Allowance for children aged 4–8 years (<533 kcal/ meal).24 An average meal without a beverage would contain 1,187 mg sodium, which is more than 60% of the Institute of Medicine's 1,900 mg daily upper limit for children aged 4–8 years.25 Meals at the 15 restaurants participating in Kids LiveWell were even higher in calories and sodium than non-participants in 2015, with the average combination containing 1,034 calories and 1,219 mg sodium. More than 150 restaurant chains nationwide are participating in Kids LiveWell, but participants are only required to offer one children's meal and one other item that meet the program's nutrition standards.5 Strengthening the program's requirements for participation by asking restaurants to adopt the Kids LiveWell standards across a larger proportion of meals, or to adopt specific standards for healthy beverages that are consistent with public health recommendations, may lead to more meaningful improvements in children's menu items.

The trend toward increasing beverage calories despite reductions in soda on children's menus is concerning. Restaurants have received substantial media attention for their efforts to remove soda from children's menus, with at least 15% of restaurants in the study sample announcing voluntary efforts since 2013.7,8 Though it is possible restaurants will make further changes in future years, as of early 2015, these commitments have not impacted availability of sugar-sweetened beverages on children's menus. When soda was removed from menus, other sweetened beverages replaced them. Restaurants should be encouraged to eliminate all sweetened beverages from children's menus, including flavored milks, fruit drinks, and sport drinks.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, only items available on children's menus were assessed, a method that does not account for how items were promoted or which items children are actually purchasing and consuming. Many children, especially adolescents, may be purchasing food from the regular menu. Although availability of unhealthy items on menu boards has been linked to the poor nutritional quality of purchased items, other factors, such as advertisements and combination meals, may impact children's food and beverage choices.27 A recent study assessing children's menu changes at a regional full-service restaurant found that when fruit and vegetable sides were bundled with children's meals by default, customer orders were more likely to include a healthy side dish.27 Similarly, McDonald's found that replacing soda with 100% apple juice and low-fat milk as the default children's beverage increased juice and milk selections by 9 percentage points.28 By not examining combination meals in this study, improvements to default children's items that could positively impact what children are purchasing and consuming may have been missed.

Additionally, this study's difference-in-difference analysis is subject to limitations. First, results from this analysis were stratified by whether an item was offered in a participating restaurant in each year. Thus, sample sizes for menu categories with fewer total items, particularly desserts, may have been too small to detect significant effects. Second, baseline nutrient data were collected in 2012, but Kids LiveWell was launched at the end of 2011. Although it is unlikely that restaurants would have made significant menu changes in the first few months of the program, any positive changes made between July 2011 and January 2012 would not have been captured in this analysis, thus biasing results toward the null. Additionally, restaurants in this sample joined Kids LiveWell at different time points between 2011 and 2015, but were labeled as either “participants” or “non-participants” across all years. This was done to account for changes participating restaurants may have made in preparation for officially joining the initiative; however, this choice may have diluted the changes made by true program participants in each year, biasing effect estimates toward the null. Third, the difference-in-difference study design assumes parallel trends over time, and this assumption could not be tested because data from an earlier time period were not available. However, all restaurants were within the nation's 100 largest chains, and there are no clear differences between characteristics of participating and non-participating restaurants that would suggest differences with regard to changes in nutrient content of children's menu items over time. Finally, this analysis included only 15 restaurants participating in Kids LiveWell, which is a small subset of the more than 150 program participants. Because participating restaurants in this sample are primarily national chain restaurants, results cannot be generalized to smaller regional chains or independent restaurants. Future research is needed to examine the true program effect using a more representative sample of participating restaurants.

Conclusions

Between 2012 and 2015, there was little progress toward improving the healthfulness of children's menu items available in the nation's largest chain restaurants. Broad-reaching efforts to engage restaurants in offering and promoting healthful children's meals, through, for example, public–private partnerships that encourage reformulation or set more-rigorous voluntary nutrition standards for kids' meals, are needed to have a bigger impact.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene for creating and maintaining MenuStat.org.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Supplemental Materials: Supplemental materials associated with this article can be found in the online version at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.11.007.

References

- 1.Poti JM, Popkin BM. Trends in energy intake among U.S. children by eating location and food source, 1977-2006. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(8):1156–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.05.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Center for Health Statistics. Caloric intake from fast-food among children and adolescents in the United States, 2011-2012. [Accessed October 21, 2015]; www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db213.pdf. Published September 2015.

- 3.Poti JM, Slining MM, Popkin BM. Where are kids getting their empty calories? Stores, schools, and fast-food restaurants each played an important role in empty calorie intake among U.S. children during 2009–2010. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(6):908–917. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2013.08.012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powell LM, Nguyen BT. Fast-food and full-service restaurant consumption among children and adolescents: effect on energy, beverage, and nutrient intake. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(1):14–20. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.417. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Restaurant Association. Kids LiveWell website. [Accessed October 15, 2015]; www.restaurant.org/Industry-Impact/Food-Healthy-Living/Kids-LiveWell/About.

- 6.Nutrition journey 2013 progress report. Boston, MA: McDonald's USA; [Accessed October 15, 2015]. http://news.mcdonalds.com/getattachment/06344ba3-94c0-4171-90ad-35f304142151. Published September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Center for Science in the Public Interest. Wendy's removes soda from kids' meals. [Accessed October 21, 2015]; http://cspinet.org/new/201501152.html. Published January 15, 2015.

- 8.Forbes. Burger King removes soda from kids menus. [Accessed October 21, 2015]; http://fortune.com/video/2015/03/10/burger-king-removes-soda-from-kids-menu/. Published March 10, 2015.

- 9.O'Donnell SI, Hoerr SL, Mendoza JA, Goh ET. Nutrient quality of fast-food kids meals. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1388–1395. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirkpatrick SI, Reedy J, Kahle LL, Harris JL, Ohri-Vachaspati P, Krebs-Smith SM. Fast-food menu offerings vary in dietary quality, but are consistently poor. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(4):924–931. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012005563. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1368980012005563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sliwa S, Anzman-Frasca S, Lynskey V, Washburn K, Economos C. Assessing the availability of healthier children's meals at leading quick-service and full-service restaurants. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2016;48(4):242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2016.01.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deierlein AL, Peat K, Claudio L. Comparison of nutrient content of children's menu items at U.S. restaurant chains, 2010–2014. Nutr J. 2015;14:80. doi: 10.1186/s12937-015-0066-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12937-015-0066-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nation's Restaurant News. Nation's Restaurant News top 200. [Accessed September 20, 2016]; http://nrn.com/nrn-top-200. Published June 26, 2012.

- 14.Bleich SN, Wolfson JA, Jarlenski MP. Calorie changes in chain restaurant menu items: implications for obesity and evaluations of menu labeling. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(1):70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.026. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bleich SN, Wolfson JA, Jarlenski MP. Calorie changes in large chain restaurants: declines in new menu items but room for improvement. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(1):e1–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bleich SN, Wolfson JA, Jarlenski MP, Block JP. Restaurants with calories displayed on menus had lower calorie counts compared to restaurants without such labels. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(11):1877–1884. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0512. http://dx.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.New York City Department of Health & Mental Hygiene. MenuStat methods. [Accessed February 2016]; http://menustat.org/methods-for-researchers/. Published January 2016.

- 18.U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Research Service, National Agricultural Library. National nutrient database for standard reference. [Accessed February 2016]; http://ndb.nal.usda.gov/. Published November 2015.

- 19.Efron B. Bootstrap methods: another look at the jackknife. Ann Statist. 1979;7(1):1–26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1214/aos/1176344552. [Google Scholar]

- 20.IOM. Nutrition Standards for Foods in Schools: Leading the Way Towards Healthier Youth. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2007. [Accessed June 29, 2016]. www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/∼/media/Files/Report%20Files/2007/Nutrition-Standards-for-Foods-in-Schools-Leading-the-Way-toward-Healthier-Youth/factsheet.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.CDC. The CDC guide to strategies for reducing the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages. [Accessed June 29, 2016]; www.cdph.ca.gov/SiteCollectionDocuments/StratstoReduce_Sugar_Sweetened_Bevs.pdf. Published March 2010.

- 22.Gase LN, McCarthy WJ, Robles B, Kuo T. Student receptivity to new school meal offerings: assessing fruit and vegetable waste among middle school students in the Los Angeles Unified School District. Prev Med. 2015;67(suppl 1):S28–S33. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mozaffarian RS, Gortmaker SL, Kenney EL, et al. Assessment of a districtwide policy on availability of competitive beverages in Boston Public Schools, Massachusetts, 2013. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E32. doi: 10.5888/pcd13.150483. http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd13.150483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. DHHS. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. 7. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; Dec, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine. Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes: water, potassium, sodium, chloride, and sulfate. [Accessed April 9, 2016]; https://iom.nationalacademies.org/Reports/2004/Dietary-Reference-Intakes-Water-Potassium-Sodium-Chloride-and-Sulfate.aspx. Published February 2004.

- 26.Center for Science in the Public Interest. Kids' meals: obesity on the menu. [Accessed October 24, 2015]; https://cspinet.org/new/pdf/cspi-kids-meals-2013.pdf. Published 2013.

- 27.Anzman-Frasca S, Mueller MP, Sliwa S, et al. Changes in children's meal orders following healthy menu modifications at a regional U.S. restaurant chain. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015;23(5):1055–1062. doi: 10.1002/oby.21061. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/oby.21061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alliance for a Healthier Generation. McDonald's and Alliance for a Healthier Generation announce progress on commitment to promote balanced food and beverage choices. [Accessed February 12, 2015]; www.healthiergeneration.org/news__events/2015/06/25/1283/mcdonalds_and_alliance_for_a_healthier_generation_announce_progress_on_commitment_to_promote_balanced_food_and_beverage_choices. Published June 25, 2015.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.