Abstract

Background

Against a background of failure to prevent neonatal invasive early-onset group B Streptococcus infections (GBS) in our maternity unit using risk-based approach for intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, we introduced an antenatal GBS carriage screening programme to identify additional women to target for prophylaxis.

Objectives

To describe the implementation and outcome of an antepartum screening programme for prevention of invasive early-onset GBS infection in a UK maternity unit.

Design

Observational study of outcome of screening programme (intervention) with comparison to historical controls (preintervention).

Setting

Hospital and community-based maternity services provided by Northwick Park and Central Middlesex Hospitals in North West London.

Participants

Women who gave birth between March 2014 and December 2015 at Northwick Park Hospital.

Methods

Women were screened for GBS at 35–37 weeks and carriers offered intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis. Screening programme was first introduced in hospital (March 2014) and then in community (August 2014). Compliance was audited by review of randomly selected case records. Invasive early-onset GBS infections were defined through GBS being cultured from neonatal blood, cerebrospinal fluid or sterile fluids within 0–6 days of birth.

Main outcome

Incidence of early-onset GBS infections.

Results

6309 (69%) of the 9098 eligible women were tested. Screening rate improved progressively from 42% in 2014 to 75% in 2015. Audit showed that 98% of women accepted the offer of screening. Recto-vaginal GBS carriage rate was 29.4% (1822/6193). All strains were susceptible to penicillin but 11.3% (206/1822) were resistant to clindamycin. Early onset GBS rate fell from 0.99/1000 live births (25/25276) in the prescreening period to 0.33/1000 in the screening period (Rate Ratio=0.33; p=0.08). In the subset of mothers actually screened, the rate was 0.16/1000 live births (1/6309), (Rate Ratio=0.16; p<0.05).

Conclusions

Our findings confirm that an antenatal screening programme for prevention of early-onset GBS infection can be implemented in a UK maternity setting and is associated with a fall in infection rates.

Keywords: Group B Streptococcus, early onset infection, neonates, screening

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first comprehensive report in the UK describing the successful implementation of a group B Streptococcus infections (GBS) screening programme and its impact on reducing early-onset GBS disease.

As our results are based on an observational rather than experimental study design, our findings could be explained by factors other than the screening programme.

As a single centre study, our findings may not be generalisable to other units.

Introduction

Group B Streptococcus (GBS) is a commensal in the human gastrointestinal and genital tract. It is estimated that 15–30% of pregnant women are colonised with GBS. A third to half of the babies born to these women will also be colonised with GBS, and 2–3% of those colonised will develop invasive GBS infection such as pneumonia, septicaemia or meningitis. Two-thirds of invasive infections in infants occur in the first seven postnatal days (invasive early-onset GBS infections (EOGBS)) and most of the remainder present 7–90 days after birth (invasive late-onset GBS infections (LOGBS)).1 GBS infection is the commonest cause of neonatal sepsis and meningitis in the western world including the UK. In the UK, rates of invasive infant GBS disease have risen significantly over the past 20 years. A recent (2014–2015) enhanced surveillance has reported rates of 0.54 and 0.36 per 1000 live births for EOGBS and LOGBS infections, respectively. These increases have occurred despite the introduction of national guidelines in 2003 recommending a risk-based prevention approach for offering intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP).2–4

All current strategies for prevention of EOGBS infections are based on the use IAP, which is known to reduce EOGBS infection by 70–90%.5 6 According to the risk-based prevention approach for offering IAP advocated by the UK National Screening Committee and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecology (RCOG), mothers with a history of a previous baby with GBS infection, urinary infection with GBS during the index pregnancy or fever during labour are given intrapartum penicillin (or clindamycin/vancomycin in women with penicillin allergy).2 5–7 However, around 50% of mothers of babies who develop EOGBS infection do not have risk factors limiting the potential impact of this approach.8 In a recent study in Northern Ireland, only 42% of women with identifiable risk factors received IAP and adherence to the guidelines was only 50–70%. Only 55.8% of neonates with confirmed EOGBS had maternal risk factors and only 25.5% of mothers of neonates with EOGBS received IAP.9 In Western Europe, the only countries other than the UK to use a risk-based approach are the Netherlands and Belgium. In the UK and the Netherlands, there has been a steady increase in EOGBS rates despite more than a decade of risk-based prevention approach for offering IAP.2 10 In contrast, significant reductions in EOGBS infections have been reported in countries such as the USA, Canada, Australia, Germany and Spain, all of whom have adopted antenatal screening programme followed by IAP to GBS carriers to prevent EOGBS.11–14 15 As such, the best approach to reduce EOGBS infections remains controversial.

Geographical variation in rates of invasive GBS disease have been noted within the UK, with North West London identified as an area of high incidence.16

Our North West London Hospital serves an ethnically diverse community of 500 000 people. Despite using the nationally recommended risk-based prevention approach, EOGBS rates in our hospital remained consistently high since 2008, approaching four times the national rate by 2013. A consensus decision was reached among the neonatologists, obstetricians, midwives and microbiologists in our hospital to introduce antenatal screening for GBS followed by IAP to GBS carriers in 2014.

In this paper, we report the implementation of our programme for antenatal screening for GBS followed by IAP and subsequent changes observed in EOGBS infection rate.

Methods

Study design

A non-randomised observation study with comparison to historical controls.

Between March 2014 and December 2015, a programme of antenatal screening for GBS followed by IAP for the prevention of invasive EOGBS infection was implemented in the maternity units at the Northwick Park Hospital and Central Middlesex Hospitals, London. In the first 6 months, this was implemented in antenatal clinics at the Northwick Park and Central Middlesex hospitals and then extended to community antenatal clinics in September 2014. Nearly all births took place in the maternity unit at Northwick Park Hospital and were the only ones included in this study. Less than 1% of women opted for home birth or delivered in other maternity units. Local guidelines for screening and antibiotic prophylaxis for mothers and babies were drafted (figure 1) based on the universal screening guidelines for prevention of early-onset GBS infection developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta (2010).17

Figure 1.

Local guidelines for prevention of early-onset neonatal group B Streptococcus infections (GBS) disease.

Women with no record of screening or who declined screening were managed according to risk-based prevention approach for offering IAP.

Screening

We offered pregnant women informed choice of antenatal GBS screening and IAP if found to be carriers.

We printed information leaflets about GBS in eight languages (English, Gujarati, Arabic, Somali, Urdu, Tamil, Polish and Rumanian). Mothers were given these leaflets at their first attendance (usually before 20 weeks gestation) and again at 35–37 weeks' gestation, when the screening was performed. Using illustrated instructions provided, most expectant mothers were able to collect low vaginal and anorectal swabs themselves (self-collection). Midwifery assistance was available for those women who did not wish to collect the swabs themselves.

Microbiology

Two swabs, one each from low vagina and anorectum were inoculated in LIM enrichment broth (Thermo Scientific), incubated at 35–37°C in air for 18–24 hours and subcultured on GBS chromogenic agar medium (Thermo Scientific Brilliance GBS Agar) and incubated again at 35–37°C in 5% CO2 for 18–24 hours. Pink colonies of presumed GBS were confirmed by latex agglutination tests to determine their Lancefield grouping. Antibiotic susceptibility tests to penicillin, clarithromycin, clindamycin, vancomycin and teicoplanin were performed using disk diffusion tests as recommended by the British Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. (V.12 January 2013).

Neonates were considered to have invasive EOGBS infection if GBS was cultured from their blood, cerebrospinal fluid or other sterile fluids within 0–6 days of birth.

Audits of implementation of guidelines

Using a random number generator, we selected a random 1% (52) sample of maternity records for vertical audit during the period August 2014 to July 2015 to review compliance with the screening and administration of IAP. Similarly, we conducted a horizontal audit of a 5% (57) random sample of GBS carriers in the period 1 March 2014 to 31 May 2015 to review whether IAP had been administered according to our guidelines.

Data collection and analysis

Laboratory-related information was collected from the Laboratory Information System (WinPath, Clinisys, UK) and information regarding the mothers and birth was collected from the hospital's computerised maternity information database. (Circonia Maternity Information System, UK).

As our intervention was a service improvement initiative rather than a research study, we did not perform a statistical sample size calculation to determine the number of the mothers who needed to be screened to demonstrate a statistical difference in invasive EOGBS rates. Rather all women (total population) during the intervention period were aimed to be included.

The key outcome measure was the incidence of EOGBS infection per 1000 live births in babies born in 2014 and 2015 compared with the incidence in the period 2009–2013. Binomial exact CIs were calculated for carriage rates and the occurrence of invasive EOGBS was compared between the two time periods using Fisher's Exact Test. The difference in occurrence rate between the two groups was also expressed as a risk ratio (ratio of the risk of EOGBS in the two groups), along with corresponding CIs. Significance was set at p<0.05.

We calculated the number of women needed to screen to prevent one case of invasive EOGBS.

Results

In the screening period, there were 9098 live births. The demographics of the mothers during the screening period, compared with those of mothers in the period 2009–2013 are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of characteristics of mothers in the prescreeeningand postscreening periods

| Variable | Category | 2009–2013 (n=25 073) | 2014–2015 (n=9104)* | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestation (weeks) | – | 39.1±2.1 | 39.1±2.0 | 0.43 |

| Age (years) | – | 29.0±5.4 | 29.7±5.3 | <0.001 |

| Mode of birth | Caesarean | 7163 (28.6%) | 2698 (29.9%) | 0.05 |

| Instrumental | 3162 (12.6%) | 1123 (12.5%) | ||

| SVD | 14 748 (58.8%) | 5193 (57.6%) | ||

| Ethnicity | Black | 3401 (13.6%) | 867 (9.6%) | <0.001 |

| British/Irish | 2665 (10.7%) | 770 (8.6%) | ||

| White other | 4964 (19.9%) | 2393 (26.6%) | ||

| Indian subcontinent | 11 811 (47.2%) | 4237 (47.0%) | ||

| Other | 2166 (8.7%) | 741 (8.2%) |

Figures are Mean±SD or number (percentage).

*Complete missing demographic data in 84 mothers.

SVD, spontaneous vaginal delivery.

The results suggested no significant difference between the two time periods for gestational age. Mothers were significantly older during screening period, but the mean difference in age was only 0.7 years. There was a small increase (1.3%) in birth by caesarean section in the screening period. The latter time period saw an increase in the percentage of white other mothers (increase from 19.9% to 26.6%) and a reduction in black mothers (13.6% down to 9.6%).

In the 22-month period between March 2014 and December 2015 (period when screening programme was introduced), 6309 (69%) of the 9098 eligible women were screened. GBS screening rate improved progressively from 42% in 2014 to 75% in 2015 as the programme was rolled out from the hospital-based antenatal clinics to the community-based clinics.

The monthly screening rates are shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Monthly screening rates for group B Streptococcus infections (GBS).

In the screened women, 97.8% (6193/6309) had lower vaginal and anorectal swabs. However, the correct timing of collection (from 35 weeks to 2 days before birth) was only achieved in 4937/6309 women (78%).

The detected GBS carriage rate in women screened using recto-vaginal swabs was 29.4% (1822/6193; 95% CI 28.3% to 30.6%) dropping to 20% (p<0.05) when vaginal swabs alone (20/100; 95% CI 12% to 30%) were collected. When rectal swabs alone were collected, 4/16 (25%) women were detected as carriers (95% CI 7.9% to 60.3%). All strains of GBS detected in the screening programme were sensitive to penicillin but 206/1822 (11.3%) of the isolates were resistant to clindamycin.

The vertical audit showed that 40/52 women (77%) were offered information about GBS screening before 28 weeks gestation. Four out of 52 women gave birth before 37 weeks. Of the remaining 48 women, 35 (73%) were offered GBS screening at 35–37 weeks gestation. Overall, 41/48 (85%) women were offered GBS screening at some point during their pregnancy from 35 weeks to time of birth. Forty of the 41 (98%) accepted the offer of GBS screening and all of the women who were found to be GBS carriers agreed to have IAP. Eleven of the 13 GBS positive women received IAP according to the guidelines. The reasons why two women did not receive IAP were not apparent from the notes.

Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP)

The horizontal audit of women who were GBS carriers showed that 46 of 57 women (80.7%) were given IAP. Of the 46 women, 42 women were given IAP at the correct time. Four of the 46 women were not given IAP as it was not necessary because they had elective caesarean section without rupture of membranes. Of the 11/57 women who were not given IAP, there was insufficient time to administer IAP due to precipitate birth (within 2 hours) in six women. In another two women screening results were not available as samples were taken immediately prior to birth. It was not clear why IAP was not prescribed in two women, and in one woman IAP was prescribed but not given.

Of the 42 women who received IAP, 35 women (83.3%) received IAP 2 or more hours prior to birth and 26 women (61.9%) received two or more doses of antibiotics indicating that they had IAP at least 4 hours before birth. The median number of doses of antibiotic administered was 2 (range 1–7, average 2.4). All eligible women received penicillin as none were allergic to penicillin.

Outcomes

Three babies developed EOGBS infection during the screening period. Of these three cases, only one was born to a woman who had been screened. She had been screened at 33 weeks and was negative for GBS at that time. It is not clear why she was screened at 33 weeks. The mother had a spontaneous vaginal delivery at term (40 weeks). However, subsequently GBS was isolated from a vaginal swab taken postpartum for investigation of unexplained tachycardia in the mother.

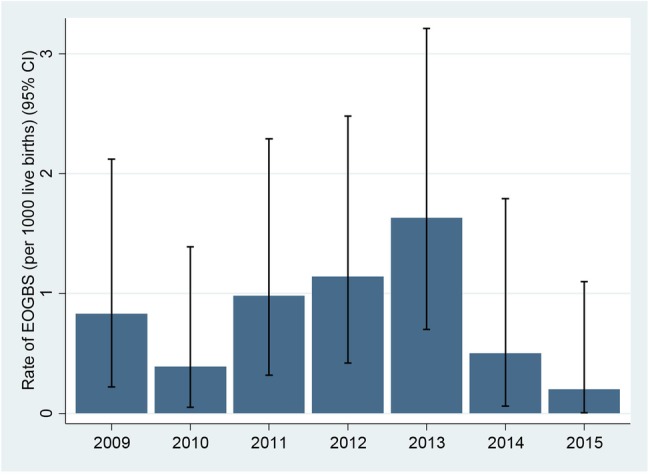

In the period 2009–2013 when risk-based strategy was used, 25 babies born to 25 276 mothers developed EOGBS infection, a rate of 0.99/1000 live births. In the period, March 2014 and December 2015, 3/9098 of all live births and only 1/6309 babies of screened mothers developed EOGBS infection. Annual rates of early-onset GBS infection in the control and screening periods are shown in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Annual rates of early-onset group B Streptococcus infections (GBS) infection in the prescreening (2009–2013) and postscreening periods (2014, 2015).

The rate of EOGBS in babies born in the screening period (0.33/1000 live births; 95% CI 0.09 to 0.96) was threefold lower (Rate Ratio=0.33; 95% CI 0.10 to 1.10) than in those born in the prescreening period 2009–2013 (0.99/1000 live births; 95% CI 0.64 to 1.46), although this difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.08).

Comparing EOGBS rates in babies born to mothers who were actually screened (0.16/1000 LB (1/6309; 95% CI 0.00 to 0.88), the rate of EOGBS was more than five times lower (Risk Ratio=0.16 (95% CI 0.02 to 1.18; p<0.05) compared with the prescreening period (0.99/1000 LB (25/25 276; 95% CI 0.64 to 1.46).

Based on reductions observed in this study, the number needed to screen to prevent one EOGBS infection was 1459 (95% CI 831 to 5984).

Discussion

Our rationale for introducing antenatal screening-based IAP was the consistently high rate of invasive EOGBS infection in our unit despite implementation of national guidance which recommends risk-based IAP. A recent national audit by the RCOG observed variable practice in adherence to the national guidelines.18

We implemented the antenatal screening programme because the efficacy of screening-based IAP has been established in many other countries.

A survey of the women participating in the programme demonstrated a high level of acceptance of screening and self-collection of the screening swabs.19 A previous study demonstrated that self-collection swabs were as sensitive for detection of GBS as physician collected swabs.20

GBS screening rate improved progressively from 42% in 2014 to 75% in 2015 as the programme was rolled out from the hospital-based antenatal clinics to the community-based clinics. As the earliest opportunity for screening was at 35–37 weeks gestation, mothers of babies born prematurely were not screened but managed according to the risk-based approach.

Where only vaginal swabs were collected, the GBS carriage rate was 20% compared with 29.4% where low vaginal and anorectal swabs were collected. Our results confirm that low vaginal and anorectal swabs are necessary to provide an accurate assessment of GBS colonisation status.21 Of women who were screened, 78% were screened at the right time and using the right specimens. The reasons for failure to screen according to our guidelines are not clear but could be due to lack of familiarity with the guidelines or the mothers were registered for the first time just before birth.

The recto-vaginal GBS carriage rate in our women was 29.4%. This rate is similar to the 28% carriage rate reported in a previous study in London and higher than the 21% carriage rate reported in Oxford.22 23 It is likely that the different carriage rates are due to the different ethnic origin of the women who were screened.24 In the Oxford study, 90% of the women described themselves as white British. In contrast, <10% of the women screened in our study were white British. (table 1). We observed a significant increase in the ‘white other’ ethnic group in the study period compared with 2009–2013 but no significant change in other ethnic groups. A majority of mothers in the ‘other white’ category was from Rumania, Poland and other Eastern European countries. There was a small increase (1.35%) in the caesarean sections in the screening period. The reasons for this increase were not clear. We believe that this increase is unlikely to have affected the early-onset GBS rates.

Development of resistance is a major concern whenever antibiotics are administered. In our study, none of the GBS strains were resistant to penicillin. Reassuringly, in the US where there is widespread use of penicillin for IAP for prevention of EOGBS, GBS continues to be susceptible to penicillin although there are reports of tolerance.17 25 Clindamycin is recommended as the alternative antibiotic for IAP in women who are allergic to penicillin. In our study population, clindamycin resistance rate in GBS isolates detected by screening was 11.3%, lower than the 18% resistance in GBS bacteraemia isolates reported recently in the UK.26

In the absence of electronic patient records and because screening was introduced as a service improvement, we used audit methodology to evaluate compliance with the guidelines rather than reviewing every individual woman. The ‘vertical’ audit demonstrated that 73% of the women were screened at the recommended 35–37 weeks of gestation, although 85% were screened at some time during pregnancy. The reasons why some of the women were not screened at 35–37 weeks are not clear. Given that only one woman declined screening, failure to screen other women could be due to an initial lack of awareness about antenatal screening programme for prevention of invasive early-onset GBS infection and the recommended timing for screening. The vertical audit demonstrated overall compliance with the administration of IAP. The horizontal audit showed a high level of compliance with choice, dose and timing of administration of the IAP. In 10% of women IAP could not be administered because of precipitate labour. Overall, 83.5% of the GBS carriers received IAP >2 hours before birth and 61.9% received IAP at least 4 hours before birth. IAP is considered to be most effective when given 4 hours before birth and ineffective if given <2 hours before birth.27

Anaphylaxis or other severe allergic reactions following administration of penicillin is understandably a concern. None of the women included in our audits gave history or developed allergic reactions to penicillin. Furthermore, we are not aware of any women developing adverse reactions to IAP through our hospital's adverse event reporting system (Datix) or through departmental reporting systems. In the USA, despite administration of penicillin to millions of mothers as IAP since 1996, there have been only four published reports of anaphylaxis associated with GBS chemoprophylaxis, all non-fatal.17

We observed non-significant reduction (p=0.08) in the EOGBS rates in the babies born to all women in 2014 and 2015 when screening-based IAP was introduced compared with the previous period 2009–2013. However, there was significant reduction in the EOGBS rate in the screened women compared with women not screened in the period 2009–2013. Among the screened population, one baby with EOGBS infection was born to a mother who was negative for GBS colonisation when she was screened at 33 weeks. The mother was later found to be colonised with GBS when a vaginal swab was tested as a part of investigation for unexplained tachycardia. It is recognised that screening swabs taken before 6 weeks of birth fail to accurately predict GBS carriage at birth in >50% of women.28 Following the introduction of screening-based IAP, the EOGBS rate our maternity service fell to a lower rate than 0.42/1000 live births reported by the Public Health England in 2014.26

In this study, the number of women needed to screen to prevent one case of invasive EOGBS infection was 1459 (95% CI 831 to 5984). This was considerably lower than the 5704 cited by Angstetra et al29 in Australia.

Limitations

As our results are based on an observational rather than experimental study design, our findings could be explained by factors other than the screening programme. In particular, changes in the characteristics of patients in the two time periods may have influenced the change in rate of infection. There was a significant increase in the proportion of women of ‘other white’ ethnicity was observed in 2014 and 2015 but we are unaware of any published reports suggesting women from these primarily Eastern and Central European countries have a lower rate of early-onset disease. Furthermore, as a single centre study, our findings may not be generalisable to other units.

We did not review every individual woman's maternity case notes to record if adequate IAP had been given to GBS carriers or to those with risk factors. Instead we relied on audits of a random sample. It is possible that the audits do not give a true picture of IAP in all women. As a result, we cannot draw any definite conclusions regarding the causal relationship between IAP administration in screened women and the EOGBS rates. We did not review individual case notes to identify women who may have developed adverse reactions to IAP. Instead, we relied on the adverse event reporting system in the hospital. It is possible that minor adverse events may not have been reported.

Conclusion

The findings of our programme confirm that screening-based intrapartum prophylaxis can be implemented and is widely accepted by pregnant women in our maternity unit. The programme was associated with a reduction in invasive EOGBS infections in neonates While the reduction did not reach statistical significance, our results provide further evidence that screening-based intrapartum prophylaxis should be considered in maternity units in the UK where rates of EOGBS infections remain high despite implementation of a risk-based approach.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the midwives, obstetricians, The Doctors Laboratory and above all, the mothers who participated in the screening programme. We also thank Professor Philip Steer for his review of the manuscript and helpful comments.

Footnotes

Contributors: GGR, GN, TMcA, AO'R, PK and RN were involved in all aspects of the programme including organisation, implementation, evaluation and analysis. HA and CT were associated in the microbiological evaluation of different methods and development of standard operational procedures. TL, SW, RB performed and analysed the audits under the supervision of GG. SH and PB generated and analysed the data with external advice from TL. All authors contributed to drafting and editing of the manuscript.

Funding: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval: The Research and Development department classed this programme as a service evaluation and improvement and confirmed that it did not require formal ethics approval.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Heath PT, Jardine LA.. Neonatal infections: group B streptococcus. Systematic review 323. BMJ Clin Evid 2014;2014:pii: 0323 http://clinicalevidence.bmj.com/x/systematic-review/0323/overview.html. (accessed 2 Aug 2016). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lamagni TL, Keshishian C, Efstratiou A, et al. . Emerging trends in the epidemiology of invasive group B streptococcal disease in England and Wales, 1991–2010. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57:682–8. 10.1093/cid/cit337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Sullivan C, Lamagni T, Efstratiou A, et al. . Group B Streptococcal (GBS) disease in UK and Irish infants younger than 90 days, 2014–2015. Arch Dis Child 2016;101:A2. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The Prevention of Early-onset Neonatal Group B Streptococcal Disease. Green-top Guideline No. 36 2nd edition 2012. https://http://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gtg36_gbs.pdf (accessed: 03 Aug 2016).

- 5.Brocklehurst P. Screening for Group B streptococcus should be routine in pregnancy: AGAINST: current evidence does not support the introduction of microbiological screening for identifying carriers of Group B streptococcus. BJOG 2015;122:368 10.1111/1471-0528.13085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caffrey OE, Prentice P. NICE clinical guideline: antibiotics for the prevention and treatment of early-onset neonatal infection. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2014;99:98–100. 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steer PJ, Plumb J. Myth: Group B streptococcal infection in pregnancy: comprehended and conquered. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2011;16:254–8. 10.1016/j.siny.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schrag SJ, Zell ER, Lynfield R, et al. . A population-based comparison of strategies to prevent early-onset group B streptococcal disease in neonates. N Engl J Med 2002;347:233–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa020205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eastwood KA, Craig S, Sidhu H, et al. . Prevention of early-onset Group B Streptococcal disease—the Northern Ireland experience. BJOG 2015;122:361–7. 10.1111/1471-0528.12841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bekker V, Bijlsma MW, van de BD, et al. . Incidence of invasive group B streptococcal disease and pathogen genotype distribution in newborn babies in the Netherlands over 25 years: a nationwide surveillance study. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14:1083–9. 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70919-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cagno CK, Pettit JM, Weiss BD. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease: updated CDC guideline. Am Fam Physician 2012;86:59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de la Rosa FM, Cabero L, Andreu A, et al. . Prevention of group B streptococcal neonatal disease: a plea for a European consensus. Clin Microbiol Infect 2001;7:25–7. 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2001.00196.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Money D, Allen VM. The prevention of early-onset neonatal group B streptococcal disease. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2013;35: 939–51. 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30818-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Maternal Group B Streptococcus in pregnancy: screening and management 2016. https://www.ranzcog.edu.au/document-library/maternal-gbs-in-pregnancy.html (accessed 03 Aug 2016).

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Report, Emerging Infections Program Network, Group B Streptococcus, 2014 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/abcs/reports-findings/survreports/gbs14.pdf (accessed on 03 Aug 2016).

- 16.Lamagni TL, Henderson K, Efstratiou A, et al. . Invasive GBS infection in England, 2009: associated risk factors. Palermo, Italy: XVIII Lancefield International Symposium on Streptococci and Streptococcal Diseases, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verani JR, McGee L, Schrag SJ. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease--revised guidelines from CDC, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 2010;59:1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Audit of current practice in preventing early-onset neonatal group B streptococcal disease in the UK 2015. Mar. First Report https://http://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/research--audit/gbs-audit-first-report.pdf (accessed on 03 Aug 2016).

- 19.McQuaid F. Patient Experience Survey. Presented at the Group B Streptococcus Conference. 2015. Nov 3, London. UK: http://gbss.org.uk/latest-news/new-one-day-conference-on-group-b-strep-for-health-professionals/ (accessed 03 Aug 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hicks P, Diaz-Perez MJ. Patient self-collection of group B streptococcal specimens during pregnancy. J Am Board Fam Med 2009;22:136–40. 10.3122/jabfm.2009.02.080011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El Aila NA, Tency I, Claeys G, et al. . Comparison of different sampling techniques and of different culture methods for detection of group B streptococcus carriage in pregnant women. BMC Infect Dis 2010;10:285 10.1186/1471-2334-10-285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hastings MJ, Easmon CS, Neill J, et al. . Group B streptococcal colonisation and the outcome of pregnancy. J Infect 1986;12: 23–9. 10.1016/S0163-4453(86)94775-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones N, Oliver K, Jones Y, et al. . Carriage of group B streptococcus in pregnant women from Oxford, UK. J Clin Pathol 2006;59:363–6. 10.1136/jcp.2005.029058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stapleton RD, Kahn JM, Evans LE, et al. . Risk factors for group B streptococcal genitourinary tract colonization in pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol 2005;106:1246–52. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000187893.52488.4b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimura K, Nishiyama Y, Shimizu S, et al. . Screening for group B streptococci with reduced penicillin susceptibility in clinical isolates obtained between 1977 and 2005. Jpn J Infect Dis 2013;66:222–5. 10.7883/yoken.66.222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Public Health England. Voluntary surveillance of pyogenic and non-pyogenic streptococcal bacteraemia in England, Wales and Northern Ireland: 2014 Health Protection Report. 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/478808/hpr4115_strptcccs.pdf (accessed 03 Aug 2016).

- 27.de Cueto M, Sanchez MJ, Sampedro A, et al. . Timing of intrapartum ampicillin and prevention of vertical transmission of group B streptococcus. Obstet Gynecol 1998;91:112–14. 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00587-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yancey MK, Schuchat A, Brown LK, et al. . The accuracy of late antenatal screening cultures in predicting genital group B streptococcal colonization at delivery. Obstet Gynecol 1996;88:811–15. 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00320-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Angstetra D, Ferguson J, Giles WB. Institution of universal screening for Group B streptococcus (GBS) from a risk management protocol results in reduction of early-onset GBS disease in a tertiary obstetric unit. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2007;47:378–82. 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2007.00760.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.