Abstract

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a well-defined risk factor for peripheral artery disease (PAD), but protects against the development and growth of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). Diabetes mellitus is associated with arterial stiffening and peripheral arterial media sclerosis. Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) are increased in diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. AGEs are known to form cross-links between proteins and are associated with arterial stiffness. Whether AGEs contribute to the protective effects of diabetes mellitus in AAA is unknown. Therefore, the ARTERY (Advanced glycation end-pRoducts in patients with peripheral arTery disEase and abdominal aoRtic aneurYsm) study is designed to evaluate the role of AGEs in the diverging effects of diabetes mellitus on AAA and PAD.

Methods and analysis

This cross-sectional multicentre study will compare the amount, type and location of AGEs in the arterial wall in a total of 120 patients with AAA or PAD with and without diabetes mellitus (n=30 per subgroup). Also, local and systemic vascular parameters, including pulse wave velocity, will be measured to evaluate the association between arterial stiffness and AGEs. Finally, AGEs will be measured in serum, urine, and assessed in skin with skin autofluorescence using the AGE Reader.

Ethics and dissemination

This study is approved by the Medical Ethics committees of University Medical Center Groningen, Martini Hospital and Medisch Spectrum Twente, the Netherlands. Study results will be disseminated through peer-reviewed journals and scientific events.

Trial registration number

trialregister.nl NTR 5363.

Keywords: Advanced glycation end products, Peripheral artery disease, Abdominal aortic aneurysm, Diabetes mellitus

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Large number of arterial tissue samples (n=120).

Four well-defined subgroups to compare different research questions: patients with peripheral artery disease and patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm equally divided with and without diabetes mellitus.

State-of-the-art quantitative measurements of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs).

Availability of additional biomaterials (skin, venous tissue, fat tissue, blood and urine) for in-depth analysis of the distribution of AGEs and other tissue markers.

Biopsy material may not include specific predilection sites for aneurysm rupture and may not represent status of vascular tissue in general due to heterogeneity.

Background

Diabetes mellitus is a risk factor for various diseases, including retinopathy, renal insufficiency and atherosclerosis.1 Remarkably, diabetes mellitus is a risk factor for peripheral artery disease (PAD), but protects against the development of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). Evidence for an inverse association between diabetes mellitus and AAA was shown in a large case–control study with veterans (n=73 451) in which an AAA was detected in 1031 participants.2 This study demonstrated an OR of 0.54 for the presence of diabetes mellitus and AAA.2 This inverse association was confirmed by a meta-analysis consisting of 17 large studies.3 In addition, AAA growth was shown to be decreased substantially in patients with diabetes mellitus (n=49) as compared to those without diabetes mellitus (n=311) after 36 months of follow-up.4 The explanation for the diverging effects of diabetes mellitus on occlusive versus dilating arterial disease remains unclear.

Differences in effects of diabetes mellitus on aorta versus large peripheral arteries may contribute to these diverging effects.5 6 AAA is characterised by inflammation of the tunica media with matrix metalloproteinase and macrophage activation, causing proteolysis and smooth muscle cell apoptosis.7 8 In contrast, PAD results from inflammation of the tunica intima and increased endothelial permeability, macrophage infiltration, retention of cholesterol and recruitment of smooth muscle cells which form a fibrous cap.9 Nevertheless, AAA and PAD appear often simultaneously in patients, possibly due to their common risk factors. Diabetes-induced changes in arterial pulse wave propagation and reflection may be another factor contributing to the diverging effects of diabetes on increased occlusive arterial disease in the lower extremities and relative protection against AAAs. Type 2 diabetes is associated with increased aortic stiffness, without abnormalities in aortic diameter or carotid stiffness.10 Patients with type 2 diabetes demonstrate a decreased reflection magnitude, which may indicate an increased penetration of pulsatile energy to distal vascular beds.10

Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) might also play a role in these different effects of diabetes mellitus on vascular tissues. AGEs are formed by non-enzymatic glycaemic and oxidative stress reactions. Diseases with increased glycaemic or oxidative stress are associated with increased AGE levels. Indeed, increased serum and skin AGEs are found in patients with diabetes mellitus compared to controls.11–13 Oxidative stress plays a role in the pathogenesis of AAA and PAD.14 15 In line with this reasoning, increased serum AGEs and skin AGEs were found in patients with PAD as compared to controls.16 17 Furthermore, our data show increased skin AGEs, non-invasively assessed, in 252 patients with AAA compared to controls (Boersema J et al, unpublished data, 2017). Two effects of AGEs have been described, namely formation of cross-links on long-lived proteins and induction of cellular stress responses by engagement of the receptor for AGEs.18 Cross-linking causes stiffness, but may also protect against mechanical structure loss of the affected tissues. The association between AGEs and arterial stiffness is shown in several studies. In patients with end-stage renal disease and in type 1 diabetes mellitus, skin AGE level was associated with pulse wave velocity, a measure of arterial stiffness.19 20 Increased arterial stiffness is associated with atherosclerotic disease.21 However, in a mouse model, homogenous stiffening reduced aneurysm growth, whereas segmental aortic stiffening caused aneurysm growth.22

Therefore, the aim of the ARTERY study (Advanced glycation end-pRoducts in patients with peripheral arTery disEase and abdominal aoRtic aneurYsm study) is to identify the association between the presence of diabetes mellitus and increased accumulation of AGEs and arterial stiffening in the vascular wall in patients with AAA and PAD. If an association would be found, it would support our hypothesis that increased AGE accumulation may cause homogenous stiffness of the vascular wall and protect against AAA development and growth, but increases atherosclerosis in PAD.

Methods

Objectives

Primary objectives

To compare the amount of AGEs in the vascular wall between patients with and without diabetes mellitus suffering from:

Abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Peripheral artery disease.

Secondary objectives

Our secondary objectives are:

To compare types and location of the AGEs between patients with and without diabetes mellitus.

To evaluate the relation between the amount of AGEs and vascular stiffness within all subgroups.

To correlate AGEs in the vascular wall to serum, urine and skin AGEs in the whole study group.

Study design

The ARTERY study is designed as a cross-sectional multicentre study, performed in three centres in the Netherlands.

Participants

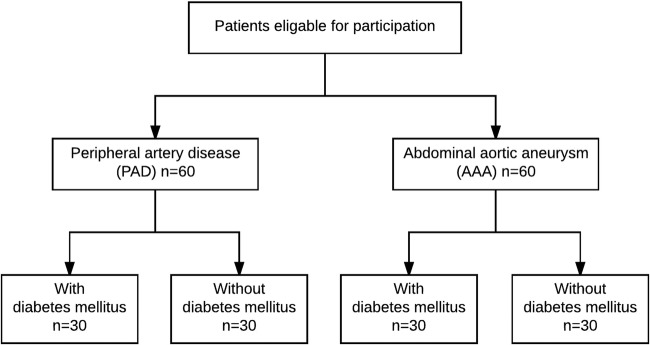

Patients from at least 18 years on, willing to participate, are eligible for the study. Patients will be included in case of the diagnosis of AAA or PAD in whom an indication for open surgery exists. Patients with concomitant AAA and PAD will be excluded, as well as patients with inflammatory disorders. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarised in table 1. Patients will be divided into four groups, based on the diagnosis of AAA or PAD and the presence or absence of diabetes mellitus (figure 1). American Diabetes Association guidelines will be used to define diabetes mellitus. The diagnosis of diabetes mellitus will be supposed by a random glucose ≥11.1 mmol/L, HbA1c ≥6.5% or 48 mmol/mol or a history of diabetes mellitus.1

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| AAA |

|

|

| PAD |

|

|

AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; PAD, peripheral artery disease.

Figure 1.

Patient groups.

In total, 120 patients will be included in the ARTERY study. This number is based on two sample size calculations. For our primary objective, calculation was based on a study which compared the content of the specific AGE pentosidine in plaques of diabetic and non-diabetic patients with carotid artery stenosis. In this study, a significant difference was found in 7 patients with diabetes mellitus (197.0±34.0 pmol/mg collagen) and 20 patients without diabetes mellitus (111.9±16.2 pmol/mg collagen).23 With a power of 80% and an α of 5%, each group has to consist of three patients. With four groups in our study, this would result in at least 12 patients. However, for our secondary objectives, an additional sample size calculation was performed. This calculation was based on skin AGEs in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. This study reported a mean skin AGE level of 2.79±0.8 arbitrary units (AU) in 973 patients with diabetes mellitus and 2.14±0.6 AU in 231 patients without diabetes mellitus.13 To show a similar difference between patients with and without diabetes mellitus of skin AGEs, 25 patients per group are required. Taking a failure plus dropout rate of 20% into account together with the possibility of subgroup analysis, we should include 30 patients per subgroup and a total of 120 patients.

Recruitment

The patients will be recruited from the outpatient clinic of vascular surgery located in one of the three following Dutch hospitals: University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG), Martini Hospital Groningen and Medisch Spectrum Twente (MST).

Patients will be informed about the study by their treating vascular surgeon. Detailed written and oral information will be given by the investigator or research coordinator.

Study procedures

After signing the informed consent form, patients are asked to fill in a questionnaire and have an appointment in the vascular laboratory. Blood will be drawn and 24-hour urine will be collected before surgery. Several biopsies will be obtained during surgery, depending on the type of surgery, and of which more details are shown below. Collected tissue biopsies will be stored until analysis.

Blood and urine sampling

Blood will be sampled for routine analysis and stored to determine AGEs. For direct analysis, blood will be drawn in an EDTA tube, lithium heparin tube and a sodium fluoride tube. Citrate plasma, EDTA plasma and serum will be stored at −80°C. For the analysis of AGEs, EDTA tubes will be used for blood collection, which will be transported on ice, centrifuged on 4°C and stored at −80°C until batch analysis.

Patients will be asked to collect urine for 24 hours and to keep the container cool until the urine is returned to the laboratory. The urine will be centrifuged, routine analysis will be performed and samples will be stored at −80°C.

Biopsy

During surgery, full-thickness biopsies from the arterial wall will be taken at predefined locations. These biopsies will be marked with sutures to assure cranio-caudal directions.

In case of an open aneurysm repair, a biopsy will be obtained 5 cm below the lowest renal artery on the left ventral side with a size of 3 (length)×1 (width) cm.

In case of bypass surgery for PAD, a biopsy will be obtained from the proximal anastomosis in the groin of 1 (length)×0.5 (width) cm.

In case of an endarterectomy for PAD, usually the common femoral artery, a biopsy will be obtained from the proximal part of the artery with a size of 1 (length)×0.5 (width) cm.

In addition, skin tissue, venous tissue and fat tissue will be obtained and stored as described below. Skin tissue will be obtained from the incision with a size of 1 (length)×0.5 (width)×1 (depth) cm. Venous tissue is only available in case of an autologous venous bypass. In that case, a circular segment from the venous graft will be obtained at the level of the distal anastomosis with a size of 0.25–0.50 cm. Peri-aortic adipose tissue will be obtained during open aneurysm repair and perivascular adipose tissue will be obtained from the groin when available during bypass surgery or endarterectomy for PAD.

Storage

After surgery, biopsy material of the arterial tissue will be divided into three equal parts. The first two parts, together with skin, venous and adipose tissue, will be snap frozen and stored at −80°C. The third part, marked with a suture on the most distal part of the biopsy, will be stored in formaldehyde for 24–72 hours. Afterwards, tissue will be dehydrated with ethanol and embedded in paraffin. Materials of MST will be fixed with formaldehyde, stored in 96% ethanol and transported to the UMCG per batch of 10 samples where these tissues will be embedded in paraffin. Additional biopsy material, which will not be used for primary or secondary research questions, will be stored for future research. Information about the use of additional tissue for future research is included in the patient information and in the informed consent form.

Outcome measures

Table 2 presents an overview of the outcome measures and measurement methods, which will be described in detail in the following paragraphs.

Table 2.

Measures and methods

| Domain | Outcome measure | Methods/equipment |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Cardiovascular risk factors Cardiovascular disease Cardiovascular family history Drug use |

Evaluation medical records Questionnaire |

| Diabetes mellitus Renal function Lipid profile Liver function Thyroid function |

Routine blood analysis, including random glucose, HbA1c, creatinine, total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, triglycerides, ALAT, ASAT, gamma-GT, LDH, TSH, T4 and hsCRP. EDTA, li-heparine tube, NaF tube. |

|

| Weight | Seca 877 scale | |

| AGEs in arterial wall | Quantitative measurement | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| Types and localisation | Immunohistochemistry | |

| AGEs in fluids | Serum AGEs | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| Urine AGEs | High-performance liquid chromatography | |

| Skin AGEs | Skin autofluorescence | AGE Reader |

| Vascular parameters | Blood pressure | Microlife WatchBP Office |

| Ankle-brachial index | Vicorder | |

| Diameter aorta | Siemens Acuson S2000 | |

| Intima-media thickness | Esaote MyLabOne | |

| Pulse wave velocity | Sphygmocor EM3 |

AGEs, advanced glycation end-products; ALAT, alanine aminotransferase; ASAT, aspartate aminotransferase; GT, glutamyltransferase; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; hsCRP, high sensitivity C-reactive protein; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Demographics

The patients' characteristics such as date of birth, sex, cardiovascular risk factors, cardiovascular disease, cardiovascular family history, duration of diabetes mellitus, glycaemic control and drug use will be assessed by evaluating medical records and will be confirmed or complemented by a questionnaire consisting of 25 questions.

Weight, length, waist and hip diameter will be recorded during visit at the vascular laboratory. Routine blood and urine analysis will be performed to evaluate the presence of diabetes mellitus and to determine several cardiovascular risk factors, including renal function.

AGEs in arterial wall

Analysis of AGEs in the arterial wall, serum and urine will be performed by the laboratory for Metabolism and Vascular Medicine, Maastricht University Medical Center, the Netherlands. Protein-bound carboxylmethyllysine (CML), Nε-(carboxyethyl)lysine (CEL) and 5-hydro-5-methylimidazolone (MG-H1) will be measured in the first part of the arterial biopsy material with ultra-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC–MS/MS), as described previously.24

To localise different types of AGEs, 4 mm slices will be made from the paraffin-embedded arterial tissue. Consecutive slices will be stained with several antibodies, including polyclonal anti-AGE antibody (Abcam, ab23722), monoclonal anti-AGE antibody for lysine derivatives (Biorbyt, orb27490) and monoclonal anti-pentosidine (Biorbyt, orb27502).

AGEs in fluids

Specific protein-bound plasma and urine AGEs, CML, CEL and MG-H1, will be measured with UPLC–MS/MS, as described previously.25 Protein-bound plasma and urine pentosidine will be measured using high-performance liquid chromatography, as described previously.26

Skin AGEs

AGEs in the skin will be assessed non-invasively with the AGE Reader (DiagnOptics Technologies BV, Groningen, the Netherlands). This method uses ultraviolet light to excite specific AGEs. Reflection and emission light are detected and converted into a skin autofluorescence (SAF) level expressed in AUs. Detailed information about this method is described elsewhere.27 Both inner forearms will be scanned three times. Patients will be asked not to use sun blockers, skin tanners or skin creams 2 weeks before the measurement, since these creams influence the SAF measurement.28

Vascular parameters

Several vascular parameters will be obtained for the ARTERY study. These parameters include blood pressures, toe pressures and duplex ultrasound of the aorta. In addition, carotid artery intima-media thickness and carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity will be measured in the vascular laboratory of the UMCG only. Measurements will be performed by trained vascular technicians.

Brachial artery blood pressures will be measured three times on both arms in sitting position after 10 min of rest.

For the ankle-brachial index measurement, patients should be in supine position. For the ankle-brachial index, the systolic pressure will be measured of the brachial artery, and the posterior tibial artery and the dorsalis pedis artery bilaterally. This will be measured during cuff release using a Doppler probe. Toe-brachial index will be measured using toe photo-electric plethysmography during gradual pressure release of a cuff placed at the base of the first toe, the toe pressure being defined by reappearance of the plethysmographic signal.

Screening to exclude concomitant AAA and PAD will be performed with duplex ultrasound in supine position. An AAA will only be reassessed in case the last imaging procedure was more than 2 months ago.

Carotid intima-media thickness will be measured as a marker of generalised atherosclerotic burden. The far wall of the left and right common carotid artery will be measured with the MyLabOne (Esaote Europe B.V., Maastricht, the Netherlands). Three measurements will be performed with an average of six heart beats of the wall segment of 10 mm before the transition to the carotid bulb.

For the measurement of the carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity, patients are asked not to drink coffee or alcohol and not to smoke 3 hours before the measurement. Patients are allowed to have a light meal. Arterial waveforms will be obtained from the carotid and femoral artery and the time delay will be measured between the feet of the two waveforms. The distance covered by the waves will be established as 80% of the distance between the two recording sites. Pulse wave velocity will be calculated as distance/time delay in m/s with the use of the Sphygmocor EM3 (AtCor Medical Pty, West Ryde, Australia).

Data handling and statistical analysis

Informed consent forms will be collected and stored at the UMCG. Biomaterials from patients will be coded. All generated data will be stored and coded in an electronic Case Report File with the software OpenClinica. Data will be exported to the SPSS software (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA) for statistical analysis.

Described data will be shown as mean with SD for normal distributed variables, mean with IQR for skewed data and number with percentages for categorical data. Difference between groups will be tested with the independent Student's t-test or non-parametric tests for skewed data. For categorical variables, χ2 test will be performed. After comparing differences with a univariate analysis, multivariable analyses will be performed to adjust for important confounders of AGEs. A value of p<0.05 will be considered significant.

Ethics consideration

All investigators performed and passed the examination of the Dutch Basic course on Regulations and Organisation for clinical investigators.

Discussion

The ARTERY study is designed to define the possible role of AGEs in the protection against AAA formation in diabetes mellitus. The protocol for this cross-sectional multicentre study addresses this issue by combining local and systemic AGE assessments with vascular functional and imaging methods.

Several research groups have evaluated the localisation and content of AGEs in human tissue before. Most studies have been performed assessing skin AGE levels.29 Furthermore, Hofman et al described the measurement of AGEs in right atrial appendages and vein graft material from patients with coronary artery disease.30 31 However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that will compare AGE accumulation in human vascular tissue and will investigate the effects of diabetes mellitus on AGE accumulation and distribution in different vascular diseases. Furthermore, the current study has been designed to provide answers on several additional research questions, including the association between tissue AGEs and vascular stiffness. In addition, this study will show the association between skin AGEs measured non-invasively and AGEs measured in vascular tissue, urine and blood.

The AGE Reader uses fluorescence for assessing skin AGEs. SAF is strongly associated with AGEs from skin biopsies.27 Several studies have shown that SAF, measured with the use of the AGE Reader, is related to arterial parameters such as pulse wave velocity and intima-media thickness, and predicts cardiovascular events.19 32–35 However, the correlation between AGEs measured in the arterial wall compared to SAF is unknown. It is likely that there is a correlation between both, since Hofmann et al30 showed that skin AGE levels were strongly correlated to AGEs in cardiac tissue from patients with coronary artery disease. A strong association between AGEs of the arterial wall and AGEs measured with SAF would underscore the role of the AGE Reader as an easy and non-invasive technique as a marker of vascular tissue accumulation.

Although we designed our study carefully, there are some limitations. We do not exclude patients suffering from renal insufficiency. These patients also have increased AGE accumulation.36 We have chosen not to exclude these patients, since patients with vascular disease frequently have renal insufficiency. Exclusion of patients with concurrent renal failure and vascular disease would result in a selection bias. Therefore, we have decided to increase our sample size to allow subgroup analysis. In addition, renal function will be a variable which will be included into multivariate analyses. In addition, biopsy material obtained at the location of disease may not be representative for vascular tissue in general. We standardise the biopsies procedure to minimise location-specific differences. However, it is technically and ethically not possible to obtain additional biopsies from different vascular sites to determine whether AGEs are distributed equally.

In conclusion, the ARTERY study will investigate the diverging effects of diabetes mellitus on AAA and PAD and the role of AGEs as a possible explanatory factor. The study will be conducted in a multicentre setting. Primary objective is to analyse AGEs in the arterial wall. As secondary objectives, AGEs of the arterial wall will be compared to AGE measurements in blood, urine and skin, and with vascular wall parameters.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Hannie Westra, PhD, and Berber Doornbos-van der Meer, MSc, Department of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology, Groningen, the Netherlands for their expert advice of immunohistochemical analysis and antibodies. The authors also thank the technicians of the vascular laboratory UMCG for helping with the protocol of the vascular measurements and performing preliminary tests: Saskia van de Zande, MSc, Anne van Gessel, MSc, and Arie van Roon, PhD. Finally, the authors wish to thank the research coordinator Anja Stam for her help setting up the study in MST.

Footnotes

Contributors: LCdV, CJZ and JDL conceived the ARTERY study. LCdV drafted the first version of this manuscript. LCdV and JB are responsible for the management of the study. All authors read, revised and approved the final manuscript and also contributed to the design of the ARTERY study.

Funding: This study is partly funded from bench fee provided for PhD students from the Junior Scientific Masterclass, University Medical Center Groningen. Additionally, an unrestricted grant from Sanofi-Aventis Nederland B.V. (grant number 13375000007024/R1/TP) and a financial contribution from the Jan Kornelis de Cock-Hadders foundation was provided.

Competing interests: AJS is a founder and shareholder of DiagnOptics BV, the Netherlands, manufacturing autofluorescence readers (http://www.diagnoptics.com). All other authors have nothing to disclose related to this paper.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the Medical Ethics committee, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands (METc 2014/269). Local approval for the ARTERY study was given by the Medical Ethics committee and the board of directors of the Martini Hospital (METc 2014/269) and MST (METc H15-076).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2016;39(Suppl 1):S1–S112.26696671 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE, et al. Prevalence and associations of abdominal aortic aneurysm detected through screening. Aneurysm Detection and Management (ADAM) Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group. Ann Intern Med 1997;126:441–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-126-6-199703150-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Rango P, Farchioni L, Fiorucci B, et al. Diabetes and abdominal aortic aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2014;47:243–61. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2013.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Rango P, Cao P, Cieri E, et al. Effects of diabetes on small aortic aneurysms under surveillance according to a subgroup analysis from a randomized trial. J Vasc Surg 2012;56:1555–63. 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.05.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shteinberg D, Halak M, Shapiro S, et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysm and aortic occlusive disease: a comparison of risk factors and inflammatory response. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2000;20:462–5. 10.1053/ejvs.2000.1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanchard JF, Armenian HK, Friesen PP. Risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysm: results of a case-control study. Am J Epidemiol 2000;151:575–83. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sinha S, Frishman WH. Matrix metalloproteinases and abdominal aortic aneurysms: a potential therapeutic target. J Clin Pharmacol 1998;38:1077–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henderson EL, Geng YJ, Sukhova GK, et al. Death of smooth muscle cells and expression of mediators of apoptosis by T lymphocytes in human abdominal aortic aneurysms. Circulation 1999;99:96–104. 10.1161/01.CIR.99.1.96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK. Progress and challenges in translating the biology of atherosclerosis. Nature 2011;473:317–25. 10.1038/nature10146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chirinos JA, Segers P, Gillebert TC, et al. Central pulse pressure and its hemodynamic determinants in middle-aged adults with impaired fasting glucose and diabetes: the Asklepios study. Diabetes Care 2013;36:2359–65. 10.2337/dc12-1463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Odetti P, Fogarty J, Sell DR, et al. Chromatographic quantitation of plasma and erythrocyte pentosidine in diabetic and uremic subjects. Diabetes 1992;41:153–9. 10.2337/diab.41.2.153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sell DR, Lapolla A, Odetti P, et al. Pentosidine formation in skin correlates with severity of complications in individuals with long-standing IDDM. Diabetes 1992;41:1286–92. 10.2337/diab.41.10.1286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lutgers HL, Graaff R, Links TP, et al. Skin autofluorescence as a noninvasive marker of vascular damage in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006;29:2654–9. 10.2337/dc05-2173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller FJ Jr, Sharp WJ, Fang X, et al. Oxidative stress in human abdominal aortic aneurysms: a potential mediator of aneurysmal remodeling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2002;22:560–5. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000013778.72404.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madamanchi NR, Vendrov A, Runge MS. Oxidative stress and vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005;25:29–38. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000150649.39934.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lapolla A, Piarulli F, Sartore G, et al. Advanced glycation end products and antioxidant status in type 2 diabetic patients with and without peripheral artery disease. Diabetes Care 2007;30:670–6. 10.2337/dc06-1508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Vos LC, Noordzij MJ, Mulder DJ, et al. Skin autofluorescence as a measure of advanced glycation end products deposition is elevated in peripheral artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2013;33:131–8. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldin A, Beckman JA, Schmidt AM, et al. Advanced glycation end products: sparking the development of diabetic vascular injury. Circulation 2006;114:597–605. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.621854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ueno H, Koyama H, Tanaka S, et al. Skin autofluorescence, a marker for advanced glycation end product accumulation, is associated with arterial stiffness in patients with end-stage renal disease. Metab Clin Exp 2008;57:1452–7. 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Llauradó G, Ceperuelo-Mallafré V, Vilardell C, et al. Advanced glycation end products are associated with arterial stiffness in type 1 diabetes. J Endocrinol 2014;221:405–13. 10.1530/JOE-13-0407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mattace-Raso FU, van der Cammen TJ, Hofman A, et al. Arterial stiffness and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: the Rotterdam Study. Circulation 2006;113:657–63. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.555235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raaz U, Zöllner AM, Schellinger IN, et al. Segmental aortic stiffening contributes to experimental abdominal aortic aneurysm development. Circulation 2015;131:1783–95. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furfaro AL, Sanguineti R, Storace D, et al. Metalloproteinases and advanced glycation end products: coupled navigation in atherosclerotic plaque pathophysiology? Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2012;120:586–90. 10.1055/s-0032-1323739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanssen NM, Wouters K, Huijberts MS, et al. Higher levels of advanced glycation endproducts in human carotid atherosclerotic plaques are associated with a rupture-prone phenotype. Eur Heart J 2014;35:1137–46. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanssen NM, Engelen L, Ferreira I, et al. Plasma levels of advanced glycation endproducts Nε-(carboxymethyl)lysine, Nε-(carboxyethyl)lysine, and pentosidine are not independently associated with cardiovascular disease in individuals with or without type 2 diabetes: the Hoorn and CODAM studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:E1369–1373. 10.1210/jc.2013-1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheijen JL, van de Waarenburg MP, Stehouwer CD, et al. Measurement of pentosidine in human plasma protein by a single-column high-performance liquid chromatography method with fluorescence detection. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2009;877:610–14. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meerwaldt R, Graaff R, Oomen PH, et al. Simple non-invasive assessment of advanced glycation endproduct accumulation. Diabetologia 2004;47:1324–30. 10.1007/s00125-004-1451-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noordzij MJ, Lefrandt JD, Graaff R, et al. Dermal factors influencing measurement of skin autofluorescence. Diabetes Technol Ther 2011;13:165–70. 10.1089/dia.2010.0123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Genuth S, Sun W, Cleary P, et al. Skin advanced glycation end products glucosepane and methylglyoxal hydroimidazolone are independently associated with long-term microvascular complication progression of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2015;64:266–78. 10.2337/db14-0215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hofmann B, Jacobs K, Navarrete Santos A, et al. Relationship between cardiac tissue glycation and skin autofluorescence in patients with coronary artery disease. Diabetes Metab 2015;41:410–15. 10.1016/j.diabet.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hofmann B, Adam AC, Jacobs K, et al. Advanced glycation end product associated skin autofluorescence: a mirror of vascular function? Exp Gerontol 2013;48:38–44. 10.1016/j.exger.2012.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lutgers HL, Graaff R, de Vries R, et al. Carotid artery intima media thickness associates with skin autofluoresence in non-diabetic subjects without clinically manifest cardiovascular disease. Eur J Clin Invest 2010;40:812–17. 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02329.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lutgers HL, Gerrits EG, Graaff R, et al. Skin autofluorescence provides additional information to the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) risk score for the estimation of cardiovascular prognosis in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 2009;52:789–97. 10.1007/s00125-009-1308-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Vos LC, Mulder DJ, Smit AJ, et al. Skin autofluorescence is associated with 5-year mortality and cardiovascular events in patients with peripheral artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014;34:933–8. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Vos LC, Boersema J, Mulder DJ, et al. Skin autofluorescence as a measure of advanced glycation end products deposition predicts 5-year amputation in patients with peripheral artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2015;35:1532–7. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hartog JW, de Vries AP, Lutgers HL, et al. Accumulation of advanced glycation end products, measured as skin autofluorescence, in renal disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2005;1043:299–307. 10.1196/annals.1333.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.