Abstract

Objectives

To report health-state utility values measured using the five-level EuroQol five-dimensional questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L) in a large sample of patients with end-stage renal disease and to explore how these values vary in relation to patient characteristics and treatment factors.

Methods

As part of the prospective observational study entitled “Access to Transplantation and Transplant Outcome Measures,” we captured information on patient characteristics and treatment factors in a cohort of incident kidney transplant recipients and a cohort of prevalent patients on the transplant waiting list in the United Kingdom. We assessed patients’ health status using the EQ-5D-5L and conducted multivariable regression analyses of index scores.

Results

EQ-5D-5L responses were available for 512 transplant recipients and 1704 waiting-list patients. Mean index scores were higher in transplant recipients at 6 months after transplant surgery (0.83) compared with patients on the waiting list (0.77). In combined regression analyses, a primary renal diagnosis of diabetes was associated with the largest decrement in utility scores. When separate regression models were fitted to each cohort, female gender and Asian ethnicity were associated with lower utility scores among waiting-list patients but not among transplant recipients. Among waiting-list patients, longer time spent on dialysis was also associated with poorer utility scores. When comorbidities were included, the presence of mental illness resulted in a utility decrement of 0.12 in both cohorts.

Conclusions

This study provides new insights into variations in health-state utility values from a single source that can be used to inform cost-effectiveness evaluations in patients with end-stage renal disease.

Keywords: end-stage renal disease, EQ-5D-5L, health-state utility values, multivariable regression

Introduction

Estimates of health-state utility values are required to undertake cost-effectiveness evaluations in which quality-adjusted life-years are the outcome of interest. Utility estimates can be captured using patient-reported questionnaires as part of a clinical trial or observational study, but in the absence of primary data, estimates are often sourced from published literature.

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is a chronic condition that has been shown to impact patients’ health status. Numerous studies have been conducted to measure utility values among patients receiving renal replacement therapy. Meta-analyses of published studies suggest that higher utility values are generally observed among patients who receive kidney transplants in comparison with those on dialysis [1], [2]. Pooling results across studies can be an appealing approach to obtain a summary estimate (weighted average with associated uncertainty) of a utility value for each health state of interest that can be used to quality-adjust survival in a cost-effectiveness model. However, caution is required when undertaking meta-analyses of health-state utility values because there is often considerable variability in utility scores as a result of using different valuation methods across studies [3]. A further limitation of pooled utility estimates is that they may not be able to take into account heterogeneity of patient characteristics and treatment or measurement factors that could explain variations in utility scores for a given condition. Individual utility studies often have small sample sizes and each study may collect only a limited number of covariates that are not comparable across studies or not always relevant to a specific decision problem or patient population.

The Access to Transplantation and Transplant Outcome Measures (ATTOM) study is a prospective observational study that involved collection of a wide range of data on patient characteristics, treatment factors and health outcomes from all 72 renal units in the United Kingdom. As part of this study, we recruited a cohort of incident kidney transplant and simultaneous (combined) pancreas and kidney (SPK) transplant recipients as well as a cohort of prevalent waiting-list patients selected as controls for transplanted patients [4]. Collection of health-state utility values as part of the ATTOM study has facilitated the following objectives of the present analysis:

-

1.

To report health-state utility values for a large sample of patients with ESRD using the five-level version of the EuroQol five-dimensional questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L).

-

2.

To conduct multivariable regression analyses to understand patient and treatment factors associated with variations in health-state utility values among kidney transplant recipients and waiting-list patients that can then be used to inform quality adjustment of life-years in cost-effectiveness evaluations.

Cost-effectiveness analyses involving patients with ESRD have been undertaken to address a wide range of decision problems, including comparisons of dialysis versus transplantation [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], alternative dialysis modalities or initiation strategies [10], [11], [12], alternative approaches to kidney allocation [13], and different immunosuppressive therapies after transplantation [14], [15], [16]. Given that there may be considerable variation among cost-effectiveness analyses in terms of the target population or the data available to researchers on patient characteristics, we present utility values for a range of potential modeling needs. We demonstrate that with access to more detailed information, we can gain greater insight into the extent of variation in health-state utility values among patients with ESRD. To our knowledge, this is the largest study to date to report health-state utility values based on EQ-5D-5L responses collected in both kidney transplant recipients and waiting-list patients in the United Kingdom.

Methods

The EQ-5D is a widely used generic instrument for describing and valuing health in terms of five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. The original version of the EQ-5D has three levels of response categories for each dimension, ranging from no problems to extreme problems [17]. More recently, a five-level version of the questionnaire was developed in an attempt to improve the instrument’s sensitivity and to reduce ceiling effects [18].

Patients aged 18 to 75 years who received a kidney or SPK transplant in the United Kingdom between November 1, 2011, and September 30, 2013, were approached for recruitment into the ATTOM study. Patients were asked to complete the EQ-5D-5L at recruitment (within 90 days of transplant). Patients who were enrolled during the first 6 months of the ATTOM study were approached at approximately 6 months post-transplant to complete the EQ-5D-5L again. It was not possible to capture EQ-5D-5L responses at 6 months in all transplant recipients because study nurses were only available on site to administer questionnaires for a total period of 12 months. The present analysis focuses only on the EQ-5D-5L data collected at 6 months because this is likely to be a more stable reflection of post-transplant health status than data collected within 90 days of transplant when patients may still be recovering from surgery.

Patients on the kidney transplant waiting list were selected as matched controls for every incident transplant recipient on the basis of the following criteria: transplant center, age (within 5 years), time on the waiting list, type of transplant (kidney only or SPK), diabetes status (as a primary renal diagnosis), and dialysis status (at the time of listing) [4]. The selection of patients on the waiting list as matched controls in the ATTOM study was designed for the purpose of studying survival as an outcome rather than specifically for the measurement of health status. Because patients were not necessarily matched on the basis of health status, this article will refer to the two cohorts as transplant recipients and waiting-list patients (rather than matched controls). For waiting-list patients, EQ-5D-5L responses were captured within 90 days of recruitment. Waiting-list patients were prevalent patients who had been receiving dialysis for varying periods of time. Therefore, the EQ-5D-5L assessment at recruitment in these patients did not represent the start of dialysis as a treatment modality. Recruitment of a prevalent cohort of waiting-list patients facilitates an analysis of health-state utility values in relation to the length of time that patients had been receiving dialysis.

Questionnaire responses were converted to index scores using the preliminary EQ-5D-5L value set for England, which can be accessed via a link on the EuroQol Web site (www.euroqol.org) [19]. We undertook ordinary least squares (OLS) regression with robust standard errors to explore the influence of transplant versus waiting-list status with and without the addition of age, gender, ethnicity, and diabetes as a primary renal diagnosis and summarized model fit by reporting Akaike information criterion values. To investigate the effect of additional patient characteristics collected in the ATTOM study on health-state utility values, we also fitted separate multivariable regression models for transplant recipients and waiting-list patients. This allowed us to explore the effect of donor type (deceased versus living donor) and kidney alone versus SPK transplant among transplant recipients and time on dialysis among patients on the waiting list. For both patient populations, we also considered smoking status and comorbidities that occurred in at least 5% of patients. Final multivariable models were based on covariates that were significant at a P-value cut-off point of 0.10.

Comorbidity information was missing for less than 1% of transplant recipients and waiting-list patients and these observations were omitted from the separate multivariable regression analyses. Among patients on the waiting list, approximately 30% had missing information about time on dialysis and therefore we performed multiple imputation creating 10 imputed data sets using ordered logistic regression before fitting the multivariable model.

All analyses were conducted in Stata version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Table 1, Table 2 summarize the characteristics of all patients who were recruited into the ATTOM study in each cohort in comparison with the characteristics of the subset of patients who completed the EQ-5D-5L in each cohort. For waiting-list patients, EQ-5D-5L responses were available in 87% of the cohort and the characteristics of the patients who completed the questionnaire were broadly consistent with those of the overall population. For transplant recipients, EQ-5D-5L responses at 6 months post-transplant were available only in 23% of the cohort, with some under-representation from patients of nonwhite ethnicity, SPK transplants, and patients who experienced graft failure or death.

Table 1.

Summary of characteristics for transplant recipients who completed an EQ-5D-5L assessment at 6 mo compared with all transplant recipients

| Characteristic |

Transplant recipients with EQ-5D-5L assessment (total = 512) |

All transplant recipients (total = 2250) |

Pvalue* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Age (y) | |||||

| 18–29 | 41 | 8.0 | 233 | 10.4 | 0.157 |

| 30–39 | 62 | 12.1 | 322 | 14.3 | |

| 40–49 | 128 | 25.0 | 550 | 24.4 | |

| 50–59 | 140 | 27.3 | 591 | 26.3 | |

| >60 | 141 | 27.5 | 554 | 24.6 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 307 | 60.0 | 1413 | 62.8 | 0.184 |

| Female | 205 | 40.0 | 837 | 37.2 | |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 452 | 88.3 | 1857 | 82.5 | 0.006 |

| Asian | 28 | 5.5 | 209 | 9.3 | |

| Black | 24 | 4.7 | 140 | 6.2 | |

| Other | 8 | 1.6 | 44 | 2.0 | |

| Diabetes (primary renal diagnosis) | 60 | 11.7 | 322 | 14.3 | 0.095 |

| Transplanted organ | |||||

| Kidney only | 489 | 95.5 | 2099 | 93.3 | 0.046 |

| Combined kidney and pancreas | 23 | 4.5 | 151 | 6.7 | |

| Donor type | |||||

| Deceased donor | 320 | 62.5 | 1439 | 64.0 | 0.480 |

| Living donor | 192 | 37.5 | 811 | 36.0 | |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Ischemic heart disease | 48 | 9.4 | 193 | 8.6 | 0.822 |

| Respiratory disease | 47 | 9.2 | 174 | 7.7 | 0.353 |

| Malignancy | 45 | 8.8 | 144 | 6.4 | 0.068 |

| Mental illness | 28 | 5.5 | 133 | 5.9 | 0.698 |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Nonsmoker | 277 | 54.1 | 1207 | 53.6 | 0.128 |

| Current smoker | 43 | 8.4 | 239 | 10.6 | |

| Ex-smoker | 151 | 29.5 | 214 | 26.2 | |

| Unknown | 41 | 8.0 | 590 | 9.5 | |

| Graft failure at time of EQ-5D-5L assessment† | 2 | 0.4 | 58 | 2.6 | <0.001 |

| Graft failure at any time during follow-up | 15 | 2.9 | 112 | 5.0 | 0.033 |

| Graft failure status missing | 2 | 0.4 | 7 | 0.3 | |

| Patient death at time of EQ-5D-5L assessment† | 0 | 0.0 | 23 | 1.0 | <0.001 |

| Patient death at any time during follow-up | 8 | 1.6 | 67 | 3.0 | 0.013 |

| Patient death status missing | 58 | 11.3 | 275 | 12.2 | |

EQ-5D-5L, five-level EuroQol five-dimensional questionnaire.

Chi-square goodness of fit.

For patients with no EQ-5D assessment, this refers to status at 6 mo after transplant.

Table 2.

Summary of characteristics for waiting-list patients who completed an EQ-5D-5L assessment at recruitment compared with all waiting-list patients

| Characteristic |

Waiting-list patients with EQ-5D-5L assessment (total = 1704) |

All waiting-list patients (total = 1959) |

Pvalue* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Age (y) | |||||

| 18–29 | 137 | 8.0 | 162 | 8.3 | 0.927 |

| 30–39 | 224 | 13.2 | 260 | 13.3 | |

| 40–49 | 412 | 24.2 | 485 | 24.8 | |

| 50–59 | 481 | 28.2 | 551 | 28.1 | |

| >60 | 450 | 26.4 | 501 | 25.6 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 984 | 57.8 | 1135 | 57.9 | 0.898 |

| Female | 720 | 42.3 | 824 | 42.1 | |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 1299 | 76.2 | 1463 | 74.7 | 0.503 |

| Asian | 192 | 11.3 | 242 | 12.4 | |

| Black | 178 | 10.5 | 213 | 10.9 | |

| Other | 35 | 2.1 | 41 | 2.1 | |

| Diabetes (primary renal diagnosis) | 195 | 11.4 | 238 | 12.2 | 0.955 |

| Time on dialysis | |||||

| Predialysis | 98 | 5.8 | 107 | 5.5 | <0.001† |

| <1 y | 224 | 13.2 | 224 | 11.4 | |

| 1–3 y | 389 | 22.8 | 389 | 19.9 | |

| >3 y | 457 | 26.8 | 457 | 23.3 | |

| Missing | 536 | 31.5 | 782 | 39.9 | |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Ischemic heart disease | 166 | 9.7 | 179 | 9.1 | 0.627 |

| Respiratory disease | 119 | 7.0 | 138 | 7.0 | 0.977 |

| Malignancy | 122 | 7.2 | 135 | 6.9 | 0.872 |

| Mental illness | 125 | 7.3 | 141 | 7.2 | 0.973 |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Nonsmoker | 854 | 50.1 | 977 | 49.9 | 0.333 |

| Current smoker | 238 | 14.0 | 262 | 13.4 | |

| Ex-smoker | 387 | 22.7 | 432 | 22.0 | |

| Unknown | 225 | 13.2 | 288 | 14.7 | |

EQ-5D-5L, five-level EuroQol five-dimensional questionnaire.

Chi-square goodness of fit.

If missing category is excluded, P = 0.870.

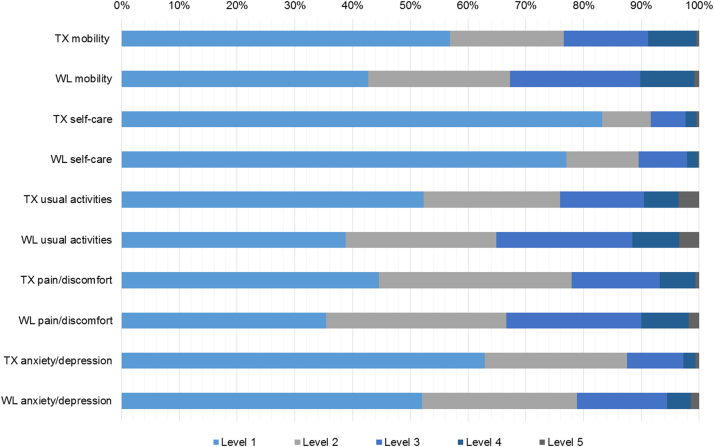

The proportion of transplant recipients and waiting-list patients reporting each level of problems for each dimension on the EQ-5D-5L is shown in Figure 1. The largest differences between transplant recipients and waiting-list patients are seen in the proportion of patients who indicated level 1 versus level 2 in the dimensions for mobility and usual activities.

Fig. 1.

Health profile showing the proportion of patients reporting each level of problems for each dimension on the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire for transplant recipients (TX) and waiting-list patients (WL). EQ-5D-5L, five-level EuroQol five-dimensional questionnaire.

Table 3 shows the influence of various combinations of predictor variables on health-state utility values taking waiting-list patients as the constant. Transplant recipients have significantly higher mean utility scores than waiting-list patients. The largest utility decrement across all models is associated with diabetes.

Table 3.

Influence of predictor variables on health-state utility values for waiting-list patients (constant) and transplant recipients (n = 2216)

| Model | Coefficient | Robust standard error | Pvalue | 95% CI | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: transplant vs. waiting list | |||||

| Waiting list (constant) | 0.773 | 0.005 | <0.001 | 0.762 to 0.783 | −408.9 |

| Transplant | +0.054 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 0.032 to 0.075 | |

| Model 2: transplant vs. waiting list, age | |||||

| Waiting list, aged 18–29 y (constant) | 0.814 | 0.015 | <0.001 | 0.784 to 0.844 | −413.4 |

| Age (y) | |||||

| 30–39 | −0.046 | 0.019 | 0.015 | −0.084 to −0.009 | |

| 40–49 | −0.049 | 0.018 | 0.008 | −0.084 to −0.013 | |

| 50–59 | −0.057 | 0.018 | 0.001 | −0.092 to −0.022 | |

| >60 | −0.027 | 0.017 | 0.123 | −0.061 to 0.007 | |

| Transplant | +0.053 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 0.032 to 0.075 | |

| Model 3: transplant vs. waiting list, gender | |||||

| Waiting list, male (constant) | 0.787 | 0.006 | <0.001 | 0.775 to 0.800 | −419.6 |

| Female | −0.034 | 0.010 | <0.001 | −0.052 to −0.015 | |

| Transplant | +0.053 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 0.031 to 0.074 | |

| Model 4: transplant vs. waiting list, diabetes | |||||

| Waiting list, nondiabetic (constant) | 0.782 | 0.006 | <0.001 | 0.771 to 0.793 | −439.4 |

| Diabetic | −0.083 | 0.016 | <0.001 | −0.115 to −0.052 | |

| Transplant | +0.054 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 0.033 to 0.075 | |

| Model 5: transplant vs. waiting list, age and gender | |||||

| Waiting list, male aged 18–29 y (constant) | 0.829 | 0.016 | <0.001 | 0.798 to 0.860 | −424.2 |

| Age (y) | |||||

| 30–39 | −0.047 | 0.019 | 0.014 | −0.084 to −0.010 | |

| 40–49 | −0.048 | 0.018 | 0.008 | −0.083 to −0.013 | |

| 50–59 | −0.058 | 0.018 | 0.001 | −0.093 to −0.023 | |

| >60 | −0.029 | 0.017 | 0.100 | −0.063 to 0.006 | |

| Female | −0.034 | 0.009 | <0.001 | −0.052 to −0.015 | |

| Transplant | +0.053 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 0.031 to 0.074 | |

| Model 6: transplant vs. waiting list, age, diabetes | |||||

| Waiting list, nondiabetic aged 18–29 y (constant) | 0.816 | 0.015 | <0.001 | 0.785 to 0.846 | −442.1 |

| Age (y) | |||||

| 30–39 | −0.036 | 0.019 | 0.060 | −0.073 to 0.002 | |

| 40–49 | −0.040 | 0.018 | 0.028 | −0.076 to −0.004 | |

| 50–59 | −0.050 | 0.018 | 0.005 | −0.085 to −0.015 | |

| >60 | −0.019 | 0.017 | 0.273 | −0.053 to 0.015 | |

| Diabetic | −0.081 | 0.016 | <0.001 | −0.113 to −0.050 | |

| Transplant | +0.054 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 0.032 to 0.075 | |

| Model 7: transplant vs. waiting list, age, gender, diabetes | |||||

| Waiting list, male nondiabetic aged 18–29 y (constant) | 0.830 | 0.016 | <0.001 | 0.800 to 0.861 | −452.6 |

| Age (y) | |||||

| 30–39 | −0.036 | 0.019 | 0.055 | −0.073 to 0.001 | |

| 40–49 | −0.039 | 0.018 | 0.029 | −0.075 to −0.004 | |

| 50–59 | −0.051 | 0.018 | 0.004 | −0.086 to −0.017 | |

| >60 | −0.021 | 0.017 | 0.233 | −0.055 to 0.013 | |

| Diabetic | −0.081 | 0.016 | <0.001 | −0.112 to −0.049 | |

| Female | −0.033 | 0.009 | <0.001 | −0.052 to −0.015 | |

| Transplant | +0.053 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 0.032 to 0.074 | |

| Model 8: transplant vs. waiting list, age, gender, diabetes, ethnicity | |||||

| Waiting list, male nondiabetic, non-Asian aged 18–29 y (constant) | 0.837 | 0.016 | <0.001 | 0.807 to 0.868 | −457.1 |

| Age (y) | |||||

| 30–39 | −0.038 | 0.019 | 0.045 | −0.075 to −0.001 | |

| 40–49 | −0.043 | 0.018 | 0.018 | −0.078 to −0.007 | |

| 50–59 | −0.054 | 0.018 | 0.002 | −0.089 to −0.020 | |

| >60 | −0.025 | 0.017 | 0.152 | −0.059 to 0.009 | |

| Female | −0.033 | 0.009 | <0.001 | −0.051 to −0.015 | |

| Diabetic | −0.078 | 0.016 | <0.001 | −0.110 to −0.046 | |

| Asian ethnicity | −0.040 | 0.018 | 0.024 | −0.074 to −0.005 | |

| Transplant | +0.051 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 0.029 to 0.072 | |

AIC, Akaike information criterion; CI, confidence interval.

Table 4, Table 5 present multivariable regression models for transplant recipients and waiting-list patients, respectively. For both models, the presence of mental illness as a comorbidity was associated with the largest utility decrement. Running separate regression models for each patient group not only allows us to explore the effect of treatment-specific covariates such as donor type for transplant recipients or the length of time on dialysis for waiting-list patients, but also suggests that the magnitude of the effect of covariates such as diabetes may differ between patient groups. In addition, controlling for other variables, we found that age was no longer a significant predictor of health-state utility values in either of the final regression models. Variance-covariance matrices for all regression models are available in Supplemental Materials found at doi:10.1016/j.jval.2017.01.011.

Table 4.

Transplant recipient multivariable regression model for EQ-5D-5L index scores (n = 510)

| Model | Coefficient | Robust standard error | Pvalue | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.860 | 0.013 | <0.001 | 0.834 to 0.885 |

| Primary renal diagnosis | ||||

| Other | Reference | |||

| Diabetes | −0.103 | 0.036 | 0.004 | −0.173 to −0.032 |

| Donor | ||||

| Deceased | Reference | |||

| Living | 0.040 | 0.018 | 0.03 | 0.004 to 0.075 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Mental illness | −0.121 | 0.045 | 0.008 | −0.210 to −0.032 |

| Ischemic heart disease | −0.093 | 0.048 | 0.052 | −0.187 to 0.001 |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Nonsmoker/unknown status | Reference | |||

| Current smoker | −0.064 | 0.038 | 0.095 | −0.139 to 0.011 |

| Ex-smoker | −0.048 | 0.021 | 0.023 | −0.089 to −0.007 |

CI, confidence interval; EQ-5D-5L, five-level EuroQol five-dimensional questionnaire.

Table 5.

Waiting-list patients multivariable regression model for EQ-5D-5L index scores (n = 1680)

| Model | Coefficient | Robust standard error | Pvalue | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.880 | 0.012 | <0.001 | 0.855 to 0.904 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | Reference | |||

| Female | −0.050 | 0.011 | <0.001 | −0.070 to −0.028 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White, black, other | Reference | |||

| Asian | −0.051 | 0.020 | 0.008 | −0.090 to −0.014 |

| Primary renal diagnosis | ||||

| Other | Reference | |||

| Diabetes | −0.059 | 0.018 | 0.001 | −0.095 to −0.024 |

| Time on dialysis | ||||

| Predialysis | Reference | |||

| <1 y | −0.052 | 0.018 | 0.004 | −0.088 to −0.016 |

| 1–3 y | −0.056 | 0.016 | 0.001 | −0.087 to −0.024 |

| >3 y | −0.076 | 0.014 | <0.001 | −0.104 to −0.048 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Ischemic heart disease | −0.045 | 0.019 | 0.014 | −0.082 to −0.009 |

| Mental illness | −0.120 | 0.024 | <0.001 | −0.167 to −0.073 |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Nonsmoker/ex-smoker/unknown status | Reference | |||

| Current smoker | −0.028 | 0.016 | 0.078 | −0.059 to 0.003 |

CI, confidence interval; EQ-5D-5L, five-level EuroQol five-dimensional questionnaire.

Discussion

Estimates of health-state utility values to inform cost-effectiveness evaluations are often sourced from the published literature. As the volume of published utility estimates for many disease areas continues to grow, analysts undertaking cost-effectiveness evaluations increasingly need to justify their approach for selecting which values to use as inputs in their models [20], [21]. One strategy is to select a single study from the published literature that most closely reflects the patient population (inclusion/exclusion criteria), disease stage, and health states defined in the model. In contrast, if multiple studies estimating health-state utility values for the same disease state have been published, another strategy is to pool estimates across studies using meta-analytic techniques. In some cases, neither of these strategies is entirely satisfactory; a single study may not report utility estimates for the full range of health states of interest in the cost-effectiveness model but meta-analysis may be unsuitable because of the high levels of heterogeneity arising from differences in the methods used to value health states [3], [22]. This has given rise to the practice of selecting health-state utility estimates from separate studies to inform the different comparator arms in a cost-effectiveness model, to distinguish between patient subgroups, or to capture decrements in utility because of adverse events and comorbidities. Drawing on data from disparate sources to inform the same cost-effectiveness model can potentially lead to inconsistent or implausible values and raise additional questions about how utility values should be combined [22], [23].

Published systematic reviews have identified a large number of studies capturing health-state utility values among patients with ESRD. In studies by Liem et al. [1] and Wyld et al. [2], health-state utility values were more extensively studied in dialysis patients than in transplant patients and only a minority of studies evaluated health status in both groups of patients at the same time. In the ATTOM study, we recruited incident kidney and SPK transplant recipients and also identified a cohort of prevalent patients on the transplant waiting list. In addition to administering the EQ-5D-5L, we collected data on a range of patient characteristics and treatment factors to allow us to explore their effects on utility scores. Our analysis confirms previous findings that transplant recipients have higher utility scores than dialysis patients. The mean utility score at 6 months for transplant recipients in our study (0.83) was similar to the values reported in meta-analyses by Liem et al. (0.81) and Wyld et al. (0.82). The mean utility score for patients on the transplant waiting list in our study was 0.77, higher than the mean values reported among dialysis patients by Liem et al. (0.56 for hemodialysis, 0.68 for peritoneal dialysis patients) and Wyld et al. (0.71). In our analysis, we also fitted separate regression models for transplant recipients and waiting-list patients. It may seem counterintuitive at first glance that the constant for waiting-list patients was higher than the constant for transplant recipients. The higher constant in the model for the waiting-list population reflects the health status of the 6% of patients who had not yet commenced dialysis. In the ATTOM study, the waiting-list population consisted of prevalent patients who had been receiving dialysis for varying periods of time, thus providing an opportunity to quantify decrements in health status in relation to time spent on dialysis.

We made a number of other notable observations based on the results of our regression analyses. First, diabetes was consistently associated with lower health-state utility values. Other studies have reported a similar finding, but of varying magnitude. Wyld et al. [2] reported a utility decrement of 0.10 for patients with diabetes. A single-center study of transplant recipients in the United States reported a utility decrement of 0.05 for patients with diabetes [24], and a study of patients receiving peritoneal dialysis in Thailand reported a decrement of 0.24 [25]. Second, female gender and Asian ethnicity were associated with marginally lower utility scores in the combined regression analysis for all patients, but when we ran separate analyses for each cohort, these covariates were retained only in the model for waiting-list patients. We were not able to investigate the reasons for these findings in the present analysis, but they warrant further consideration of the impact this could have on expected health gains for different patient groups as a result of transplantation. Third, in the separate multivariable regression models for transplant recipients and waiting-list patients, the analyses showed that when we were able to control for other factors affecting health status such as comorbidities and length of time on dialysis, age no longer had any additional explanatory effect on index scores. The systematic review by Wyld et al. [2] attempted to explore the effect of age on utility estimates. When data were available, the authors found that mean patient age did not significantly influence utility; however they, stated that they were not able to further investigate the effect of age because of incomplete reporting and use of mean age rather than patient-level data.

Primary collection of data on health-state utility values can be a time-consuming and resource-intensive exercise, making the published literature a valuable source of estimates to inform cost-effectiveness evaluations. Looking across some of the cost-effectiveness analyses in patients with ESRD published in the last 10 years [7], [8], [9], [12], [15], [16], there is still a concentrated reliance on utility estimates from a small number of studies published before 1999, all with sample sizes of fewer than 200 patients [26], [27], [28]. For cost-effectiveness evaluations that adopt a cohort modeling approach, it may be sufficient to source mean utility estimates by treatment modality. However, with increasing use of patient-level modeling, it may also be desirable to have access to utility estimates that capture variability in outcomes across the patient population. The final multivariable regression models that were fitted separately in the transplant recipient and waiting-list populations in our analysis provide insight into how health-state utility values vary by a range of patient characteristics.

One of the strengths of the ATTOM study is the ability to explore the effects of a wide range of covariates on health status using patient-level data, but there may be other important confounders that we did not capture and were not able to control for in our analyses. Another important limitation of the study design with respect to this analysis is that the process of selecting patients as matched controls from the transplant waiting list was not specifically done on the basis of health status but rather to inform an analysis of survival. For this reason, in addition to reporting combined regression analyses of EQ-5D-5L responses for transplant recipients and waiting-list patients, we explored the effect of treatment-specific covariates in separate regression models for each cohort. Although sample sizes for each cohort in this study were larger than those in many previous studies that have estimated health-state utility values in patients with ESRD, the number of EQ-5D-5L responses that we were able to collect at 6 months in the transplant cohort was lower than planned. We explored the representativeness of the subset of patients with EQ-5D-5L responses in relation to the overall recruited population of transplant recipients. Patients with EQ-5D-5L responses were representative in terms of age and comorbidities, but patients with poorer outcomes (graft failure and death) were under-represented. Nevertheless, because the rates of graft failure and patient death in the transplant cohort at 6 months were low, this is unlikely to have much of an impact on the estimates of mean index scores. Similarly, we explored the representativeness of waiting-list patients with EQ-5D-5L responses in comparison with the overall recruited population of waiting-list patients and did not find any significant differences in patient characteristics. In particular, we did not find any evidence to suggest that patients with poorer health status who had been receiving dialysis for longer periods of time were under-represented in our analysis of EQ-5D-5L responses. In theory, it may be preferable to explore the relationship between health status and treatment factors such as time on dialysis using a longitudinal study design. The potential advantages of a longitudinal design need to be balanced with other considerations such as the time and cost associated with data collection as well as the likelihood of loss to follow-up that could lead to bias.

In the present analysis, we have restricted our approach to the use of OLS regression. Although several regression modeling approaches have been proposed in the literature to deal with the bounded and skewed nature of health-state utility data [29], [30], [31], [32], we believe that OLS regression with robust standard errors is justified in this case because the primary objective was to estimate mean utility scores and sample sizes were relatively large. Nonetheless, there are a number of other analytic approaches that could be applied to our data set to facilitate a more comprehensive comparison of different methods in future research.

Conclusions

When conducting cost-effectiveness evaluations of patients with ESRD, careful consideration should be given to the treatment strategies being compared and the selection of the most appropriate utility values that reflect the characteristics of the patient populations of interest. The present study provides new insights into variations in health-state utility values from a single source that can be used to inform such evaluations in the future.

Acknowledgments

Source of financial support: This article presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under the Programme Grant for Applied Research (RP-PG-0109-10116) entitled Access to Transplantation and Transplant Outcome Measures (ATTOM). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

We thank all patients who participated in the ATTOM study. We are also grateful to the ATTOM research nurses for their time and effort in recruiting patients for the study.

EQ-5DTM is a trade mark of the EuroQol Group. The EQ-5D-5L was used in the ATTOM study with permission from the EuroQol Group Foundation.

Footnotes

Supplemental material accompanying this article can be found in the online version as a hyperlink at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2017.01.011 or, if a hard copy of article, at www.valueinhealthjournal.com/issues (select volume, issue, and article).

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material

References

- 1.Liem Y.S., Bosch J.L., Hunink M.G. Preference-based quality of life of patients on renal replacement therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Value Health. 2008;11:733–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wyld M., Morton R.L., Hayen A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of utility-based quality of life in chronic kidney disease treatments. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peasgood T., Brazier J. Is meta-analysis for utility values appropriate given the potential impact different elicitation methods have on values? Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33:1101–1105. doi: 10.1007/s40273-015-0310-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oniscu G.C., Ravanan R., Wu D. Access to Transplantation and Transplant Outcome Measures (ATTOM): study protocol of a UK wide, in-depth, prospective cohort analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010377. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jassal S.V., Krahn M.D., Naglie G. Kidney transplantation in the elderly: a decision analysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:187–196. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000042166.70351.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kontodimopoulos N., Niakas D. An estimate of lifelong costs and QALYs in renal replacement therapy based on patients’ life expectancy. Health Policy. 2008;86:85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howard K., Salkeld G., White S. The cost-effectiveness of increasing kidney transplantation and home-based dialysis. Nephrology. 2009;14:123–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2008.01073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haller M., Gutjahr G., Kramar R. Cost-effectiveness analysis of renal replacement therapy in Austria. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:2988–2995. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanchez-Escuredo A., Alsina A., Diekmann F. Economic analysis of the treatment of end-stage renal disease treatment: living-donor kidney transplantation versus hemodialysis. Transplant Proc. 2015;47:30–33. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalez-Perez J.G., Vale L., Stearns S.C. Hemodialysis for end-stage renal disease: a cost-effectiveness analysis of treatment options. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21:32–39. doi: 10.1017/s026646230505004x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee C.P., Chertow G., Zenios S.A. A simulation model to estimate the cost and effectiveness of alternative dialysis initiation strategies. Med Decis Making. 2006;26:535–549. doi: 10.1177/0272989X06290488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu F.X., Treharne C., Arici M. High-dose hemodialysis versus conventional in-center hemodialysis: a cost-utility analysis from a UK payer perspective. Value Health. 2015;18:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mutinga N., Brennan D.C., Schnitzler M.A. Consequences of eliminating HLA-B in deceased donor kidney allocation to increase minority transplantation. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;5:1090–1098. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McEwan P., Baboolal K., Conway P. Evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of sirolimus versus cyclosporin for immunosuppression after renal transplantation in the United Kingdom. Clin Ther. 2005;27:1834–1846. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Earnshaw S.R., Graham C.N., Irish W.D. Lifetime cost-effectiveness of calcineurin inhibitor withdrawal after de novo renal transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1807–1816. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007040495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morton R.L., Howard K., Webster A.C. The cost-effectiveness of induction immunosuppression in kidney transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:2258–2269. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996;37:53–72. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herdman M., Gudex C., Lloyd A. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L) Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1727–1736. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devlin N.J., Shah K., Feng Y. OHE Research Paper, Office of Health Economics; London: 2016. Valuing health-related quality of life: an EQ-5D-5L value set for England. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brauer C.A., Rosen A.B., Greenberg D. Trends in the measurement of health utilities in published cost-utility analyses. Value Health. 2006;9:213–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence. Guide to the methods of technology appraisal 2013. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/article/pmg9/resources/non-guidance-guide-to-the-methods-of-technology-appraisal-2013-pdf. [Accessed October 19, 2015]. [PubMed]

- 22.Ara R, Wailoo AJ. NICE DSU Technical Support Document 12: the use of health state utility values in decision models. Available from: http://www.nicedsu.org.uk. [Accessed October 16, 2015]. [PubMed]

- 23.Ara R., Brazier J.E. Populating an economic model with health state utility values: moving toward better practice. Value Health. 2010;13:509–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dukes J.L., Seelam S., Lentine K.L. Health-related quality of life in kidney transplant patients with diabetes. Clin Transplant. 2013;27:E554–E562. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakthong P., Kasemsup V. Health utility measured with EQ-5D in Thai patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis. Value Health. 2012;15:S79–S84. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Churchill D.N., Torrance G.W., Taylor D.W. Measurement of quality of life in end-stage renal disease: the time trade-off approach. Clin Invest Med. 1987;10:14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laupacis A., Keown P., Pus N. A study of the quality of life and cost-utility of renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 1996;50:235–242. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Wit G.A., Ramsteijn P.G., de Charro F.T. Economic evaluation of end stage renal disease treatment. Health Policy. 1998;44:215–232. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(98)00017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pullenayegum E.M., Tarride J.E., Xie F. Analysis of health utility data when some subjects attain the upper bound of 1: Are Tobit and CLAD models appropriate? Value Health. 2010;13:487–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basu A., Manca A. Regression estimators for generic health-related quality of life and quality-adjusted life years. Med Decis Making. 2012;32:56–69. doi: 10.1177/0272989X11416988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunger M., Baumert J., Holle R. Analysis of SF-6D index data: Is beta regression appropriate? Value Health. 2011;14:759–767. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hernandez Alava M., Wailoo A.J., Ara R. Tails from the peak district: adjusted limited dependent variable mixture models of EQ-5D questionnaire health state utility values. Value Health. 2012;15:550–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material