Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to determine the relationship between hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and tinnitus in South Korea using data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (KNHANES) (2010–2012).

Study design

Cross-sectional analysis of a nationwide health survey.

Methods

KNHANES is a nationally representative cross-sectional survey of South Korea population. Only postmenopausal women aged 19–65 years were included in the study (n=2736). Auditory function was evaluated using pure-tone audiometric testing according to established KNHANES protocols. Subjects were questioned about their experience with tinnitus. Exogenous hormone-related factors included the starting age and duration of HRT.

Results

The overall prevalence of tinnitus was 22.2% among postmenopausal women. (1) Tinnitus severity was significantly higher in women using HRT (p=0.0024) and (2) significantly lower in women who breast fed their children (p=0.0386). (3) According to logistic regression models, the longer duration of HRT was significantly associated with increasing tinnitus (OR=1.323, 95% CI 1.007 to 1.737, p=0.0441).

Conclusion

A longer duration of HRT was associated with developing tinnitus in Korean postmenopausal women. Further experimental and epidemiological researches are needed to elucidate the causal relationship between HRT and tinnitus.

Keywords: Tinnitus, Hormone replacement therapy, Epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We used a nationally representative, cross-sectional, civilian non-institutionalised sample of Korean adults.

We evaluated the relationships between tinnitus and hormone replacement therapy (HRT) by including a variety of economic, social, behavioural and health variables.

We used five models that were regarded as possible confounding variables in a series of logistic regression analyses to lessen the confounding effect of possible tinnitus determinants.

Tinnitus status was notified only by respondents and were not observed directly or recorded. And we could not examine the HRT preparations being used by the participant.

Introduction

Tinnitus is a debilitating condition described as the conscious perception of sound without an actual external sound.1 The prevalence of tinnitus has been reported to range from 5% to 25% in the adult population.2 3 Risk factors for tinnitus include hearing loss, occupational and recreational noise exposure, obesity, smoking, alcohol consumption, head injury, arthritis, use of ototoxic medications (to treat hypertension), genetic predisposition, otosclerosis, Ménière’s disease, vestibular schwannoma, anxiety, depression and temporomandibular joint dysfunction.3–9 Reproductive hormones may also affect the development of tinnitus.1

Postmenopausal women have a dramatically altered physiology due to sex hormone changes, resulting in hot flashes, flushing, oedema and mood changes.10 Some postmenopausal women select the use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to alleviate their symptoms. Previous reports have indicated that HRT may cause sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus and hyperacusis.11 12 Based on these findings, we hypothesised that HRT might be associated with tinnitus in postmenopausal women in Korea.

As we know for certain, no previous studies have used nationwide data to investigate the association between self-reported tinnitus and HRT in postmenopausal females. In this study, we scrutinise the correlation between tinnitus and HRT in postmenopausal females using the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (KNHANES).

Methods

Study population

This study was conducted using KNHANES information obtained between 2010 and 2012 (Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDCP), Cheongwon, Korea). KNHANES, a nationally representative survey planned to precisely evaluate nutrition and health, has been used by the KCDCP’s Division of Chronic Disease Surveillance since 1998. A health survey team, consisting of an otolaryngologist and nurse examiners, travel around the country in a mobile examination centre performing physical examinations and interviews. The KNHANES consists of a health examination survey, a health interview and a nutritional survey. The survey collects information through domestic interviews and direct formalised physical investigations implemented in the especially well-found mobile examination centre. The KNHANES programme has previously been depicted in full.13 14

During 2010–2012, there were 25 534 KNHANES participants aged 19 years or older. Of these, 22 798 participants were excluded from the analysis because of at least one of the following reasons: male (n=11 616), older than 65 years (n=2711), not postmenopausal (n=8447) or missing the ‘Presence of Tinnitus’ questionnaire (n=24). In Korea, only a small proportion of menopausal women aged 65 years or older currently take HRT. So we excluded the older women. A total of 2736 women were eligible for the study. Written informed consent was received from all subjects ahead of survey. Endorsement of this study protocol was acquired from the Institutional Review Board of the Catholic University of Seoul Korea (IRB no. HC14EISE0097; Bucheon, Korea).

Audiometric measurement and tinnitus survey and noise exposure

The test of pure-tone audiometry was performed using an automatic audiometer (SA 203, Entomed, Malmö, Sweden) in a double-walled, sound-isolated chamber located in a KNHANES mobile examination centre. All audiometric examinations were performed under the direct control of an otolaryngologist qualified to operate an audiometer. Only an air conduction hearing threshold was estimated. The supra-auricular headphones were used in all participants in soundproof chamber to provide good sound isolation form room noise. The trained otolaryngology-specialist offered standardised directions about the automated audiometric examination. The test of automated audiometry was fully implemented through a modified Hughson-Westlake procedure; it used a single pure tone for 1–2 s duration. Threshold was defined as the lowest hearing level at which can be heard for at least half of a series of ascending trials with a minimum of two responses out of three at a single level. The automated audiometry test including air-conducted pure-tone stimuli demonstrated a good repeatability (test–retest reliability) and validity, which were equivalent to those of the manual pure-tone audiometry test.15 16 All subjects reacted by pressing a button when they perceived a tone. Pure-tone air conduction was estimated for test frequencies of 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0 and 6.0 kHz. Hearing impairment was defined as the pure-tone averages of 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 and 4.0 kHz stimuli at a threshold of a 40 dB hearing level in the ear with better hearing.17

Subjects were inquired of their experiences with tinnitus.18 In reply for the questionnaire item, ‘Within the past year, did you ever hear a sound (buzzing, hissing, ringing, humming, roaring, machinery noise) originating in your ear?’, examiners were trained to inscribe ‘yes’ if the subject stated perceiving an unusual or odd sound at any time in the past year. Participants who answered ‘yes’ to the question were then inquired about the resultant annoyances in their lives: ‘How severe is this noise in your daily life?’ Participants circled the response that best described their experiences: not annoying, annoying (irritating), severely annoying or causes sleep problems. Participants were deemed to suffer from annoying tinnitus if they rated tinnitus severity as annoying or severely annoying. Subjects were asked about their experience with noise exposure. Subjects were instructed to circle ‘yes’ 'Have you ever worked in the place for over 3 months that you should have a loud voice for communicating with the other people because of noising sound?’

Assessment of HRT and other risk factors

Endogenous hormone-related risk factors included age at menarche, age at menopause, total reproductive years, age at first birth, duration of breast feeding and number of pregnancies. Information of obstetric and gynaecological issues was assembled by questioning the subjects for recalling the age of menopause and menarche and the age at last and first parturition, breast -feeding, parity and gravity. Exogenous hormone-related risk factors included duration of oral contraceptive use and starting age and duration of HRT.

The health interview survey consists of individual factors and household factors. The individual components included information on cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, physical activity mental and oral health, weight control, which was collected via self-administration. The household components were composed of medical conditions, socioeconomic status, injury and activity limitation, which were collected using face-to-face interview in mobile examination centre. Cigarette smoking status was classified into three categories: current smokers, ex-smoker and non-smoker. The amount of pure alcohol consumed was calculated in grams per day during the 1 month before the interview. Depending on average of daily alcohol consumption, participants were categorised into three groups. Subjects who consumed an average of less than 1 g/day of alcohol were non-drinkers, while those who consumed 1–15 g/day were considered mild to moderate drinker. The heavy drinkers consumed an average of more than 15 g/day of alcohol. Regular exercise means energetic aerobic activity done for at least 20 min at least 3 days a week. Height and weight were checked by trained medical personnel. Standing height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a SECA 225 stadiometer (SECA, Hamburg, Germany) when subject were standing barefoot. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as individual’s weight (kg) divided by the square of their height on metre. Measurement of participant’s waist circumference (WC) was performed midpoint level between the iliac crest and the costal margin. The measurement should be read at the end of a normal expiration using a measuring tape (seca 200, seca Deutschland) to the nearest 0.1 cm. Obesity was defined as a BMI ≥25 kg/m2 among the population over 19 years of age in accordance with the Asia-Pacific criteria of WHO guideline. The cut-off levels for abdominal obesity were defined as a WC ≥90 cm for men and WC ≥85 cm for women, according to the definition by the Korea Society for the study of obesity. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥130 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥85 mm Hg or being on an antihypertensive management for patients with history of hypertension. Diabetes mellitus was defined as a fasting plasma glucose level ≥126 mg/dL or being on medication use for elevated glucose. Those who answered that they had been diagnosed by a medical professional with stroke, myocardial infarction and angina were defined as having a cardiovascular disease. With the same questionnaire as those used in the KNHANES, mental health surveys were performed in all participants. The adult respondents checked their level of stress according to none, mild, moderate and severe categories. Depression was screened using the Korean version of the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Short Form (CIDI-SF), which was validated as a cost-effective screening instrument that could be easily integrated into health surveys.19 The WHO CIDI-SF contains queries such as ‘In your lifetime, have you ever had 2 weeks or more when nearly every day you felt sad, blue, or depressed?’ and ‘Have there ever been 2 weeks or longer when you lost interest in most things such as work or hobbies or things you usually like to do for fun?’ To assess depression, subjects answered ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to a question of whether they had experienced a depressed mood for 2 or more continuous weeks during the previous year.

Statistical analyses

The SAS survey procedure (V.9.3; SAS Institute) was used to reflect the complex sampling design and sampling weights of KNHANES and estimate nationally representative prevalence. The procedures contained unequal probabilities of selection, oversampling and non-response information, which enabled inferences about adolescent participants.

The prevalence and 95% CIs for tinnitus were calculated. For univariate analyses, logistic regression analysis (PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC in SAS) and the Rao-Scott χ2 test (PROC SURVEYFREQ in SAS) were used to test the statistical significance of relationship between tinnitus and risk elements in a complex sampling design. Participant features were calculated as numbers or percentages for categorical variables and as means±SE for continuous variables and simple and multiple linear regression analyses were used to investigate the relationship between tinnitus and mental status. Multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to determine whether the tinnitus of participants had a relationship with HRT. We estimated five statistical models based on the characteristics of the variables. Model 1 included age. Socioeconomic and lifestyle-related characteristics including BMI, smoking status, alcohol intake and exercise habits were included based on the results from the univariate analysis (model 2). Model 3 adjusted for the variables in model 2 plus comorbidity such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, education, income, stress level, breast feeding, bilateral oophorectomy and hysterectomy. Finally, model 5 adjusted for the variables in model 3 plus hearing impairment, mental health and noise exposure.

Results

Among the 2736 participants older than 19 years of age, 607 had experienced tinnitus in the previous 12 months (prevalence: 22.2%). The age distribution in the total of 2736 women eligible for the study was as follows. Below 49 years was 11.14%, 50–54 years was 31.16%, 55–59 years was 32.29% and 60–64 years was 25.41%. The characteristics of subjects with and without tinnitus are shown in table 1. Participants with tinnitus were significantly older than those without tinnitus (p=0.001). The prevalence of tinnitus was higher in hearing-impaired subjects than in normal-hearing subjects (p<0.0001). Of the health–behaviour parameters examined, only heavy drinking (p=0.019) and general obesity (p=0.004) were significantly associated with no tinnitus. Subjects with tinnitus had less education (p=0.005), depression (p=0.013) and a lower household income (p=0.003).

Table 1.

Potential factors associated with tinnitus

| Parameter | Tinnitus | ||

| Yes (n=607) | No (n=2129) | p Value | |

| Age (years) | 56.2±0.3 | 55.5±0.1 | 0.001* |

| Smoking—current smoker (%) | 4.6±1.1 | 5.9±0.7 | 0.364 |

| Drinking—heavy drinker (%) | 0.3±0.2 | 1.3±0.3 | 0.019* |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 9.7±1.5 | 11.2±0.8 | 0.354 |

| Hypertension (%) | 39.6±2.5 | 35.8±1.3 | 0.149 |

| Hyperlipidaemia (%) | 9.4±1.4 | 10.8±0.5 | 0.314 |

| Routine exercise (%) | 16.1±1.9 | 19.4±1.1 | 0.140 |

| General obesity (%) | 31.4±2.2 | 39.1±1.3 | 0.004* |

| Abdominal obesity (%) | 52.1±2.5 | 56.0±1.3 | 0.149 |

| Education—≥high school (%) | 31.1±2.6 | 37.6±1.4 | 0.005* |

| Residential area—urban (%) | 76.1±2.8 | 77.0±2.2 | 0.695 |

| Spouse—yes (%) | 85.5±1.7 | 83.5±1.0 | 0.327 |

| Income—lower quartile (%) | 19.5±1.8 | 15.2±1.0 | 0.003* |

| Noise exposure (%) | 10.0±0.9 | 10.5±1.4 | 0.749 |

| Depression (%) | 12.4±1.9 | 7.8±0.8 | 0.013* |

| Anxiety (%) | 19.0±1.1 | 25.0±2.4 | 0.014* |

| Cardiovascular disease† (%) | 3.0±0.5 | 2.7±0.7 | 0.708 |

| Metabolic syndrome‡ (%) | 40.0±1.3 | 43.1±2.4 | 0.248 |

| Osteoarthritis (%) | 12.6±1.2 | 10.2±0.9 | 0.362 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (%) | 3.4±0.2 | 3.2±0.2 | 0.845 |

| Stress—moderate to severe (%) | 28.5±2.3 | 24.8±1.1 | 0.118 |

| Hearing impairment (%) | 17.8±1.9 | 7.0±0.7 | <0.001* |

| Thyroid disease (%) | 4.8±0.8 | 4.4±0.6 | 0.847 |

| Asthma (%) | 4.9±1.1 | 3.4±0.5 | 0.151 |

| Sleep duration (hour) | 6.8±0.2 | 6.8±0.2 | 0.682 |

Data are presented as mean±SE.

*Indicates statistical significance.

†Myocardiac infarction and angina were known by questionnaire of subjects.

‡Metabolic syndrome was defined: the Asia-Pacific guideline was used for abdominal obesity ≥80 cm for women; high triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL or medication; low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol 40 mg /dL for women or medication; high blood pressure ≥130/85/85 mm Hg or medication; high fasting blood glucose ≥126 mg/dL or medication or diagnosed by doctor.

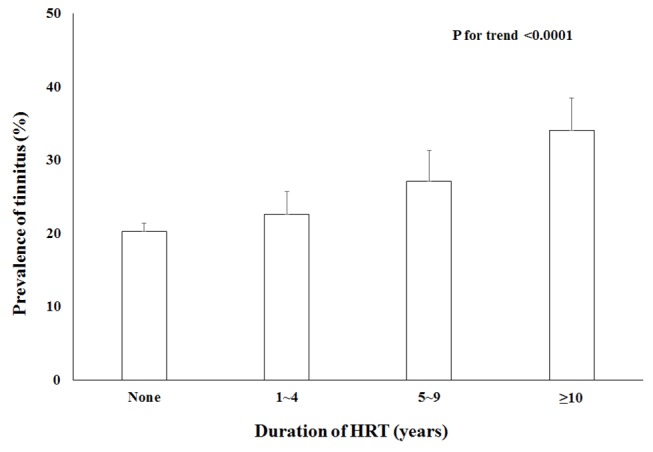

The relationship between tinnitus prevalence and HRT duration is illustrated in figure 1. The prevalence of tinnitus was 20.3% in subjects not using HRT, 22.6% in subjects using HRT for 1–4 years, 27.2% in subjects using HRT for 5–9 years and 34.0% in subjects using HRT for more than 10 years (p for trend <0.0001).

Figure 1.

The effect of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) duration on the prevalence of tinnitus.

Table 2 presents data on the relationship between tinnitus and HRT according to logistic regression models. Age, BMI, smoking status, alcohol intake, exercise habits, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, education, income, stress level, breast feeding, bilateral oophorectomy, hysterectomy, hearing impairment, depression, anxiety and noise exposure were included in multivariate logistic regression analyses. In the final regression model (model 5), the use of HRT in postmenopausal women was significantly associated with tinnitus (OR=1.309, 95% CI 1.000 to 1.712, p=0.0496). Regarding duration of HRT, there was a significant trend between a longer period of HRT and an increased risk of tinnitus.

Table 2.

Logistic regression models of hormone replacement therapy for tinnitus

| Hormone replacement therapy OR (95% CI) | Duration of hormone replacement therapy OR (95% CI) | |||||||

| No | Yes | p Value | No | 1–4 years | 5–9 years | ≥10 | p for trend | |

| Model 1 | 1 | 1.445 (1.130 to 1.849) | 0.0033* | 1 | 1.216 (0.851 1.737) | 1.415 (0.911 to 2.199) | 1.858 (1.207 to 2.862) | 0.0013* |

| Model 2 | 1 | 1.426 (1.113 to 1.826) | 0.0049* | 1 | 1.192 (0.834 to 1.705) | 1.378 (0.887 to 2.140) | 1.873 (1.216 to 2.883) | 0.0016* |

| Model 3 | 1 | 1.357 (1.041 to 1.769) | 0.0239* | 1 | 1.234 (0.836 to 1.823) | 1.354 (0.857 to 2.140) | 1.552 (0.972 to 2.479) | 0.0207* |

| Model 4 | 1 | 1.347 (1.029 to 1.763) | 0.0304* | 1 | 1.214 (0.818 to 1.799) | 1.326 (0.834 to 2.108) | 1.578 (0.982 to 2.534) | 0.0235* |

| Model 5 | 1 | 1.309 (1.000 to 1.712) | 0.0496* | 1 | 1.144 (0.764 to 1.711) | 1.251 (0.801 to 1.955) | 1.556 (0.964 to 2.512) | 0.0418* |

Model 1: adjusted for age.

Model 2: adjusted for age, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, alcohol intake and exercise habits.

Model 3: adjusted for age, BMI, smoking status, alcohol intake, exercise habits, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, education, income, stress level, breast feeding, bilateral oophorectomy and hysterectomy.

Model 4: adjusted for age, BMI, smoking status, alcohol intake, exercise habits, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, education, income, stress level, breast feeding, bilateral oophorectomy, hysterectomy and hearing impairment.

Model 5: adjusted for age, BMI, smoking status, alcohol intake, exercise habits, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, education, income, stress level, breast feeding, bilateral oophorectomy, hysterectomy, hearing impairment, depression, anxiety and noise exposure.

*Indicates statistical significance.

Discussion

This is the first nationwide study to examine the relationship between HRT and tinnitus in postmenopausal women. After adjusting for confounding factors (age, BMI, smoking status, alcohol intake, exercise habits, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, stress level, oophorectomy and hearing impairment), our findings indicate that a longer duration of HRT use was associated with increasing tinnitus in postmenopausal women.

In a study of guinea pigs, HRT caused inflammation and vacuolisation of the stria vascularis and elevated the auditory brainstem response threshold.20 Additionally, in perimenopausal female CBA mice, HRT was found to impair inner ear (outer hair cell) functioning.21 This may be due to the effect of HRT on the auditory efferent feedback system from the medial superior olivary complex to the outer hair cells.22 Previous epidemiological studies have shown a negative effect of combined oestrogen and progestin therapy on the auditory system of postmenopausal women and a sensitivity of the auditory pathway to HRT in premenopausal women.23 24

There is evidence to suggest that oestrogen causes tinnitus.11 First, oestrogen receptors (ERs) are found in areas of the ear involved in transmitting hearing impulses and in inner ear homeostasis, such as inner and outer hair cells, spiral ganglion cells, the stria vascularis and the spiral ligament.25 26 Cells of the small vessels located in the inner ear and cochlea have also been shown to have ERs. Oestrogen may alter the flow of metabolites into cells that process auditory information.27 Second, oestrogen alters neurotransmitter receptor concentrations and has a direct excitatory effect on neuronal tissue.28–30 Oestrogen has been found to downregulate the number of synaptic vesicles located near the presynaptic membrane of inhibitory synapses.31 Oestrogen also reduces the ability of neurons to synthesise gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), by reducing autoinhibition of the GABAergic preoptic area through the GABAB receptor.32 Thus, oestrogen affects transmission of auditory impulses from the cochlea to the higher auditory centres (eg, superior temporal gyrus of the cerebral cortex).20 Furthermore, cochlear abnormalities can initiate tinnitus, and the condition can be maintained through cascades of neural changes in the central auditory system.33

Progesterone may also play an important role in tinnitus. First, progesterone receptors have been found in the inner ear structures, such as the stria vascularis and the endolymphatic sac, in mice.21 As these structures affect the blood supply to the cochlea and regulate endolymph, it is likely that progesterone plays a vital role in auditory mechanisms.21 Second, progesterone may affect the auditory system by acting as an agonist of GABAA receptors, which are prevalent throughout the auditory system.34 Third, progesterone reduces serotonin levels, and therefore indirectly influences auditory processing.35 Fourth, progesterone may counterbalance the main excitatory action of oestrogen through inhibition of the central nervous system; for example, allopregnanolone, a metabolite of progesterone, inhibits chloride ion conductance and subsequently reduces neuronal excitability.36 37 Fifth, the use of a combination of oestrogen and progesterone may potentiate progesterone function. Continuous progestin therapy can cause ongoing downregulation of oestrogen receptors or irreversible damage to receptors that can prevent the binding of circulating oestrogen.19 Additionally, in a study of mice, the expression of progesterone receptors was upregulated by oestrogen.38

This study showed that among the population to have HRT, the prevalence of tinnitus was significantly higher than among those not to have HRT after adjusting for sociodemographic factors and comorbidities including hearing impairment. There is an association that women with tinnitus have a lesser degree of hearing than those without tinnitus. This could demonstrate that these postmenopausal women without HRT, with little or no remaining endogenous oestrogen production, have a higher rate of debilitating effect of auditory function after than before menopause, which is consistent with preceding suggestions that oestrogen might have a protective role in auditory function.11 12 39 Subjects with HRT could have poorer hearing than those without HRT. However, when adjusting for hearing impairment and noise exposure in model 5, participants with HRT still had a greater OR for tinnitus as compared with the non-HRT group.

A tinnitus questionnaire for postmenopausal women receiving HRT may have clinical applications. Tinnitus causes irritability, frustration, hearing difficulties, annoyance, hyperacusis, concentration difficulties, insomnia, psychological distress and depression.40–47 Discontinuation of HRT may lead to recovery of hearing function and resolution of tinnitus.11 12 It is important for physicians to be attentive to the association between HRT and tinnitus in postmenopausal women.

This study has several limitations. First, due to study’s cross-sectional design, causal relationships could not be evaluated. Second, tinnitus status was based on subjective responses using self-administered questionnaires, and misclassification of tinnitus may have occurred. Third, we could not examine the HRT preparations being used by the participant because of national representative survey. Finally, we could not evaluate the vestibular dysfunction.

Despite these limitations, however, our study is the first to investigate an association between HRT duration and tinnitus prevalence in postmenopausal women using a representative Korean population. As this study was a well-designed nationwide population-based survey, the results can be considered valid and reliable.

Conclusion

We found that HRT for longer periods of time was associated with an increased risk of developing tinnitus in Korean postmenopausal women. In the future, a randomised and/or prospective study is needed to elucidate the causal relationship between HRT and tinnitus.

Acknowledgments

We thank the 150 residents at the otorhinolaryngology departments at the 47 training hospitals in South Korea. We also thank members of the Division of Chronic Disease Surveillance of the KCDCP for their participation and dedicated work. We are grateful to Jeong-A Kim and Mi-Ran Jang for their valuable review of the manuscript. The English in this document has been reviewed by at least two native English-speaking professional editors.

Footnotes

Contributors: SSL wrote the first draft of the manuscript and took part in the data analyses. KDH performed statistical analyses. YHJ designed the study and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Competing interests: None declared.

Data sharing statement: Additional data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at with the doi:10.5061/dryad.v586b.

References

- 1. Langguth B, Kreuzer PM, Kleinjung T, et al. Tinnitus: causes and clinical management. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:920–30. 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70160-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Khedr EM, Ahmed MA, Shawky OA, et al. Epidemiological study of chronic tinnitus in Assiut, Egypt. Neuroepidemiology 2010;35:45–52. 10.1159/000306630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shargorodsky J, Curhan GC, Farwell WR. Prevalence and characteristics of tinnitus among US adults. Am J Med 2010;123:711–8. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Michikawa T, Nishiwaki Y, Kikuchi Y, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with tinnitus: a community-based study of Japanese elders. J Epidemiol 2010;20:271–6. 10.2188/jea.JE20090121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lockwood AH, Salvi RJ, Coad ML, et al. The functional neuroanatomy of tinnitus: evidence for limbic system links and neural plasticity. Neurology 1998;50:114–20. 10.1212/WNL.50.1.114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fujii K, Nagata C, Nakamura K, et al. Prevalence of tinnitus in community-dwelling Japanese adults. J Epidemiol 2011;21:299–304. 10.2188/jea.JE20100124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nondahl DM, Cruickshanks KJ, Huang GH, et al. Tinnitus and its risk factors in the Beaver dam offspring study. Int J Audiol 2011;50:313–20. 10.3109/14992027.2010.551220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gopinath B, McMahon CM, Rochtchina E, et al. Incidence, persistence, and progression of tinnitus symptoms in older adults: the Blue Mountains Hearing Study. Ear Hear 2010;31:407–12. 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181cdb2a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dehmel S, Pradhan S, Koehler S, et al. Noise overexposure alters long-term somatosensory-auditory processing in the dorsal cochlear nucleus--possible basis for tinnitus-related hyperactivity? J Neurosci 2012;32:1660–71. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4608-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, et al. Executive summary of the stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:1159–68. 10.1210/jc.2011-3362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Strachan D. Sudden sensorineural deafness and hormone replacement therapy. J Laryngol Otol 1996;110:1148–50. 10.1017/S0022215100135984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hanna GS. Sudden deafness and the contraceptive pill. J Laryngol Otol 1986;100:701–6. 10.1017/S0022215100099928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Park SH, Lee KS, Park HY. Dietary carbohydrate intake is associated with cardiovascular disease risk in korean: analysis of the third Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination survey (KNHANES III). Int J Cardiol 2010;139:234–40. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Park HA. The Korea national health and nutrition examination survey as a primary data source. Korean J Fam Med 2013;34:79. 10.4082/kjfm.2013.34.2.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Swanepoel deW, Mngemane S, Molemong S, et al. Hearing assessment-reliability, accuracy, and efficiency of automated audiometry. Telemed J E Health 2010;16:557–63. 10.1089/tmj.2009.0143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mahomed F, Swanepoel deW, Eikelboom RH, et al. Validity of automated threshold audiometry: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ear Hear 2013;34:745–52. 10.1097/01.aud.0000436255.53747.a4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. World Health Organization. Millions of people in the world have hearing loss that can be treated or prevented: 2013. http://www.who.int/pbd/deafness/news/Millionslivewithhearingloss.pdf accessed 1 Apr 2015.

- 18. Seo JH, Kang JM, Hwang SH, et al. Relationship between tinnitus and suicidal behaviour in korean men and women: a cross-sectional study. Clin Otolaryngol 2016;41:222–7. 10.1111/coa.12500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gigantesco A, Morosini P, Development MP. Development, reliability and factor analysis of a self-administered questionnaire which originates from the World Health Organization's Composite International Diagnostic Interview - Short Form (CIDI-SF) for assessing mental disorders. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 2008;4:8. 10.1186/1745-0179-4-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bittar RS, Cruz OL, Lorenzi MC, et al. Morphological and functional study of the cochlea after administration of estrogen and progesterone in the guinea pig. Int Tinnitus J 2001;7:41–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Price K, Zhu X, Guimaraes PF, et al. Hormone replacement therapy diminishes hearing in peri-menopausal mice. Hear Res 2009;252:29–36. 10.1016/j.heares.2009.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhu X, Vasilyeva ON, Kim S, et al. Auditory efferent feedback system deficits precede age-related hearing loss: contralateral suppression of otoacoustic emissions in mice. J Comp Neurol 2007;503:593–604. 10.1002/cne.21402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guimaraes P, Frisina ST, Mapes F, et al. Progestin negatively affects hearing in aged women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:14246–9. 10.1073/pnas.0606891103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Caruso S, Maiolino L, Rugolo S, et al. Auditory brainstem response in premenopausal women taking oral contraceptives. Hum Reprod 2003;18:85–9. 10.1093/humrep/deg003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stachenfeld NS. Sex hormone effects on body fluid regulation. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2008;36:152–9. 10.1097/JES.0b013e31817be928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stenberg AE, Wang H, Fish J, et al. Estrogen receptors in the normal adult and developing human inner ear and in Turner's syndrome. Hear Res 2001;157:87–92. 10.1016/S0378-5955(01)00280-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hultcrantz M, Simonoska R, Stenberg AE. Estrogen and hearing: a summary of recent investigations. Acta Otolaryngol 2006;126:10–14. 10.1080/00016480510038617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Biegon A, McEwen BS. Modulation by estradiol of serotonin receptors in brain. J Neurosci 1982;2:199–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Silva NL, Boulant JA, testosterone Eof. Estradiol, and temperature on neurons in preoptic tissue slices. Am J Physiol 1986;250:R625–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kelly MJ, Moss RL, Dudley CA. Differential sensitivity of preoptic-septal neurons to microelectrophoresed estrogen during the estrous cycle. Brain Res 1976;114:152–7. 10.1016/0006-8993(76)91017-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ledoux VA, Woolley CS. Evidence that disinhibition is associated with a decrease in number of vesicles available for release at inhibitory synapses. J Neurosci 2005;25:971–6. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3489-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wagner EJ, Ronnekleiv OK, Bosch MA, et al. Estrogen biphasically modifies hypothalamic GABAergic function concomitantly with negative and positive control of luteinizing hormone release. J Neurosci 2001;21:2085–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baguley D, McFerran D, Tinnitus HD. Lancet 2013;382:1600–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Follesa P, Concas A, Porcu P, et al. Role of allopregnanolone in regulation of GABA(A) receptor plasticity during long-term exposure to and withdrawal from progesterone. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 2001;37:81–90. 10.1016/S0165-0173(01)00125-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Birzniece V, Bäckström T, Johansson IM, et al. Neuroactive steroid effects on cognitive functions with a focus on the serotonin and GABA systems. Brain Res Rev 2006;51:212–39. 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Katzenellenbogen BS. Mechanisms of action and cross-talk between estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor pathways. J Soc Gynecol Investig 2000;7:S33–S37. 10.1177/1071557600007001S10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rogawski MA, Progesterone RMA. Progesterone, neurosteroids, and the hormonal basis of catamenial epilepsy. Ann Neurol 2003;53:288–91. 10.1002/ana.10534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Moffatt CA, Rissman EF, Shupnik MA, et al. Induction of progestin receptors by estradiol in the forebrain of estrogen receptor-alpha gene-disrupted mice. J Neurosci 1998;18:9556–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hederstierna C, Hultcrantz M, Collins A, Christina H, Malou H, Aila C, et al. Hearing in women at menopause. prevalence of hearing loss, audiometric configuration and relation to hormone replacement therapy. Acta Otolaryngol 2007;127:149–55. 10.1080/00016480600794446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schleuning AJ. Management of the patient with tinnitus. Med Clin North Am 1991;75:1225–37. 10.1016/S0025-7125(16)30383-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Crocetti A, Forti S, Ambrosetti U, et al. Questionnaires to evaluate anxiety and depressive levels in tinnitus patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2009;140:403–5. 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.11.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tyler RS, Baker LJ. Difficulties experienced by tinnitus sufferers. J Speech Hear Disord 1983;48:150–4. 10.1044/jshd.4802.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dobie RA. Depression and tinnitus. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2003;36:383–8. 10.1016/S0030-6665(02)00168-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Miguel GS, Yaremchuk K, Roth T, et al. The effect of insomnia on tinnitus. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2014;123:696–700. 10.1177/0003489414532779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Langguth B. A review of tinnitus symptoms beyond 'ringing in the ears': a call to action. Curr Med Res Opin 2011;27:1635–43. 10.1185/03007995.2011.595781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tyler RS, Baker LJ. Difficulties experienced by tinnitus sufferers. J Speech Hear Disord 1983;48:150–4. 10.1044/jshd.4802.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tyler RS. Neurophysiological models, psychological models, and treatments for tinnitus Tyler RS, Tinnitus treatment: clinical protocols. New York: Thieme, 2006:1–22. [Google Scholar]