Abstract

Introduction

Retrievable inferior vena cava (IVC) filters have been increasingly used in patients with major trauma who have contraindications to anticoagulant prophylaxis as a primary prophylactic measure against venous thromboembolism (VTE). The benefits, risks and cost-effectiveness of such strategy are uncertain.

Methods and analysis

Patients with major trauma, defined by an estimated Injury Severity Score >15, who have contraindications to anticoagulant VTE prophylaxis within 72 hours of hospitalisation to the study centre will be eligible for this randomised multicentre controlled trial. After obtaining consent from patients, or the persons responsible for the patients, study patients are randomly allocated to either control or IVC filter, within 72 hours of trauma admission, in a 1:1 ratio by permuted blocks stratified by study centre. The primary outcomes are (1) the composite endpoint of (A) pulmonary embolism (PE) as demonstrated by CT pulmonary angiography, high probability ventilation/perfusion scan, transoesophageal echocardiography (by showing clots within pulmonary arterial trunk), pulmonary angiography or postmortem examination during the same hospitalisation or 90-day after trauma whichever is earlier and (B) hospital mortality; and (2) the total cost of treatment including the costs of an IVC filter, total number of CT and ultrasound scans required, length of intensive care unit and hospital stay, procedures and drugs required to treat PE or complications related to the IVC filters. The study started in June 2015 and the final enrolment target is 240 patients. No interim analysis is planned; incidence of fatal PE is used as safety stopping rule for the trial.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval was obtained in all four participating centres in Australia. Results of the main trial and each of the secondary endpoints will be submitted for publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12614000963628; Pre-results.

Keywords: adult intensive and critical care, thromboembolism, trauma management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is conducted as a phase IIb multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT) concerning the benefits and risks of early use of inferior vena cava (IVC) filters in patients with major trauma who have contraindications to anticoagulant prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism (VTE). It will provide the much needed important information to clinicians about the best strategy to reduce the burden of VTE in patients with major trauma.

In addition to clinical effectiveness, this study will also examine the (A) mechanical complications of IVC filters, (B) bleeding complications, (C) cost-effectiveness and (D) long-term health outcomes after using IVC filters as a primary VTE prophylactic measure in patients with major trauma.

Blinding of the treating clinicians to treatment allocation is deemed to be impossible; centralised web-based randomisation to ensure adequate allocation concealment, and strict guidelines on when and how often a CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) should be performed to detect mild or early pulmonary embolism for the study patients. This study design will (A) reduce outcome detection bias, (B) avoid unnecessary radiation from routine CTPA for asymptomatic study patients and (C) ensure the clinical safety of the patient allocated to the control group.

The study is not powered to detect a small to moderate difference in 90-day mortality (<9%); but the results of this study will inform us whether a phase III RCT is necessary to confirm the role of IVC filters—as a primary VTE prophylactic device—for patients with major trauma.

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is one of the most preventable causes of death and morbidity in hospitalised patients.1 2 VTE accounted for over 14 000 hospitalisations (or 70 per 100 000) and 5000 deaths in Australia in 20083; and according to the New South Wales Clinical Excellence Commission, a large number of hospital-associated VTE (n=2229) including fatal PE were identified in 2012 and 2013. The total cost of VTE per person per annum, including loss in productivity, was estimated to be over US$1.47 million and the total cost of VTE for Australia in 2008 was $A3.9 billion.3 The total burden of VTE in the European Union countries exceeded 1.6 million events, comprising 0.7 million cases of DVT, 0.4 million cases of non-fatal PE and 0.5 million VTE-related deaths.4 The majority of patients with VTE-related deaths were untreated with VTE prophylaxis and VTE was not diagnosed before postmortem; only 7% of deaths occurred in those on prophylaxis or therapy.5 Studies of routine screening of hospital patients for asymptomatic DVT have shown that VTE is common but clinically silent in a high proportion. As such, VTE prophylaxis is of paramount importance in reducing mortality and morbidity of VTE. Although underutilisation of VTE prophylaxis in many situations has improved with education and use of electronic prescription alert systems, recent studies show that a significant proportion of hospitalised patients, at high risk for VTE, including those who are critically ill or injured, do not receive VTE prophylaxis.6 7

The incidence of asymptomatic VTE, including PE, in critically ill or injured patients is very high despite anticoagulant prophylaxis.8 In one cohort study, up to 10% of the patients already had unsuspected DVT at the time of intensive care unit (ICU) admission.9 The American College of Chest Physicians guidelines recommend that all ICU patients should be assessed for their risk of VTE, and that most should receive VTE prophylaxis on admission to the ICU.10 Both the National Quality Forum and The Joint Commission (the organisation that accredits American hospitals) also recommend that the proportion of patients who receive VTE prophylaxis or have documentation about why VTE prophylaxis is not given within 24 hours of ICU admission, should be used as a performance indicator.2 11 However, many clinicians perceive the risk of bleeding as more important than the risk of VTE, leading to a delay or even omission of VTE prophylaxis in a high proportion of patients.12–14 Observational studies have suggested that a delay of more than 1–3 days in initiating VTE prophylaxis is associated with a threefold increased risk of VTE and possibly also mortality in critically ill and injured patients.15–18 Early initiation of VTE prophylaxis using a multimodal approach, including the use of mechanical VTE prophylaxis for many critically ill and injured patients, may be the most effective way to reduce the disease burden of VTE in the critically ill and injured patients.19 20

Injury is a leading cause of death among young people and was responsible for two-thirds of deaths of young Australians in 2005 despite the injury death rate falling by 50% between 1986 and 2005.21 Guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians have suggested that subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or low-dose unfractionated heparin (UFH) should be used for thromboprophylaxis in patients at high risk of VTE including patients with major trauma.22 Although LMWH may be more efficacious than UFH, and there was no difference in major bleeding in patients without obvious contraindications to anticoagulants,23 the clinical concern about excessive haemorrhage persists especially for patients who have significant risk of bleeding after trauma. The incidence of asymptomatic PE between 3 and 7 days after moderate to major trauma is extremely high (24%), despite LMWH or UFH prophylaxis,8 and use of pneumatic lower limb compression devices or UFH prophylaxis alone may not be completely effective in preventing VTE.8 22 24 Indeed, fatal PE is the third leading cause of death in patients who survive the first 24 hours after major trauma.25 As such, retrievable inferior vena cava (IVC) filters have been increasingly used in many patients with trauma.26 27

Preliminary evidence to support the role of IVC filters in major trauma

IVC filters are, however, expensive ($A>3000 per filter without considering radiology costs), invasive and associated with significant complications, including erosion of the IVC, inducing thrombosis either above or below the filter, migration of the filter to the right atrium, and tilting or malpositioning of the filter resulting in ineffective filtering of emboli and fatal PE.28–30 Despite the risk of having significant complications and evidence to support its cost-effectiveness from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or meta-analyses is sparse,31–35 IVC filters are increasingly used in many trauma centres worldwide.36 In 2007, the US market for IVC filters was valued at under $200 million, with expected growth to top $300 million in 2012.37 The most appropriate patients who will benefit from an IVC filter and the optimal time to insert and remove a retrievable IVC filter in patients after major trauma remains uncertain.38–40 Confounding these issues further, some retrievable IVC filters are not removed (>10% for many centres) which may induce long-term venous thromboembolic or mechanical complications especially if the filter is left in situ for longer than 60–90 days.41 42

Currently the use of different strategies in preventing VTE after major trauma remains very controversial,22 43–50 and the practice of thromboprophylaxis, especially in patients who have significant risk of bleeding within the first week of trauma, varies considerably between different trauma centres.25 The optimal method of thromboprophylaxis in patients after major trauma at risk of bleeding remains highly uncertain.

Fatal PE is an important patient-centred outcome after major trauma.51 It has been reported to occur at a frequency between 0.4% and 4.2% after major trauma.24 52 53 It has been argued that thromboprophylaxis may not be cost-effective in trauma patients,35 because fatal PE occurs more often in patients who have more severe traumatic injuries and some of these patients may die with PE, instead of from PE. Our recent study did, however, suggest that fatal PE is a preventable disease, with an attributable mortality of 50% (95% CI 36% to 62%), and it accounts for about 12% of all deaths after major trauma.54 55 Furthermore, our recent multicentre observational studies showed that acute PE is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients,56 and omission of early VTE prophylaxis in critically ill patients, in particular after multiple trauma, either without clinical reasons (relative risk of 1.66, 95% CI 1.22 to 2.25; absolute increase in risk 3.9%, 95% CI 2.2 to 5.6) or due to contraindications from increased bleeding risk, is associated with a substantial increased risk of mortality.18

Retrievable IVC filters have been used in our patients with trauma in Western Australia (WA) since 2007, and in the years 2007 and 2008, 7.4% of all patients with trauma received a retrievable IVC filter. During these 2 years, the incidence of radiological or postmortem examination confirmed symptomatic PE occurred at 3% of all hospitalised patients with trauma, and this risk increased substantially to about 10% if only patients with trauma who had an Injury Severity Score (ISS) >15 (see online supplementary appendix 1) were considered. Since we noted that fatal PE is likely preventable with an IVC filter, retrievable IVC filters have been increasingly used as a primary thromboprophylaxis for our patients with trauma who have contraindications to pharmacological thromboprophylaxis (>70–100 per annum in WA), very similar to many trauma centres.26 The preliminary findings from our most recent observational study showed that retrievable IVC filters appeared to be very effective in reducing fatal PE (none observed for all 223 patients who received an IVC filter). The use of IVC filters was still associated with substantial risks of lower or upper limb VTE (16%) and mechanical complications (12%) including adherent filter (5%) and IVC filter occlusion due to thrombus (4%), despite a high filter retrieval rate (87%) through a centralised protocol and process.42 Evidence suggested that if IVC filters are applied to all patients with major trauma, the estimated number of IVC filters needed to prevent one fatal PE is relatively large (mean 125, 95% CI 100 to 167)54 and may not be cost-effective.

bmjopen-2017-016747supp001.pdf (145.4KB, pdf)

Because retrievable IVC filters are relatively expensive and invasive as a preventive strategy, it is more likely to be cost-effective if it is reserved for patients who have a very high risk of PE and, at the same time, the injuries are still compatible with survival when use of pharmacological thromboprophylaxis is contraindicated.54 According to the Trauma Embolic Scoring System (TESS) (see online supplementary appendix 2),57 58 the TESS score for this type of patients would be likely greater than 10 with an estimate risk of symptomatic VTE between 10% and 20% even when a proactive approach to detect VTE is not adopted. Even though many patients with major trauma will have deranged coagulation profiles which are considered as contraindicated to receive anticoagulant prophylaxis, their propensity to develop VTE does not appear to be different from those without such acquired coagulopathy.59–61 This group of patients with trauma will serve as the best candidates to assess the cost-effectiveness of IVC filters and will form the study population of this planned RCT in which we will adopt a proactive approach to detect VTE in our study patients (for details see below).

Primary aims of the study

To assess whether the early use of IVC filters as primary VTE prophylaxis can reduce the incidence of symptomatic PE in patients who are at high risk of developing DVT and PE after major trauma who also have contraindications to anticoagulant VTE prophylaxis.

To assess the cost-effectiveness of IVC filters in preventing PE after major trauma in this cohort of patients.

Secondary aims of the study

To assess whether IVC filters are effective in reducing symptomatic PE in patients who do not receive pharmacological DVT prophylaxis within the first 7 days of major trauma.

To assess the incidence of complications of IVC filters in patients with major trauma, including whether IVC filter will increase the risk of symptomatic and asymptomatic DVT in the lower limbs.

To assess the risk factors associated with DVT and PE after an IVC filter placement.

Methods and analysis

Protocol version 1.1 Feb 2015, no protocol amendment since initiation of the trial.

Randomisation process

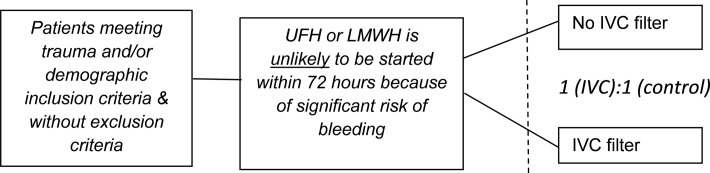

This is a pragmatic four-centre population-based phase IIb randomised controlled parallel-design study comparing the benefits, harms and cost-effectiveness of IVC filters in patients with major trauma at high risk of developing DVT and PE but with contraindications to pharmacological VTE prophylaxis (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing inclusion and equal allocation of participants to receive an IVC filter or no IVC filter for thromboembolic prophylaxis. IVC, inferior vena cava; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; UFH, unfractionated heparin.

Written informed consent will be obtained either from each patient or their next of kin (or person responsible for the patient) for participation in the trial including use of long-term health outcome data through the data linkage unit; and for those who are allocated to the IVC filter group, separate clinical consents for IVC filter insertion and removal will be obtained. Randomisation will be conducted by a random number generator, in permuted blocks stratified by centre, and allocation concealment will be maintained by a web-page randomisation and allocation portal (http://davinci.statisticalrevelations.com.au/). Blinding of the patients and attending clinicians is not intended or possible, but the data analyst will be blinded to the study allocation. All VTE outcomes will be adjudicated by radiologists independent of the trial to reduce detection bias. Deidentified data will be entered into the password-protected web portal of the trial (http://davinci.statisticalrevelations.com.au/); and only the chief investigators and members of the data monitoring and safety committee (DMSC) would have access to outcome data of the participants. As in May 2017, the trial has reached >80% enrolment target.

Inclusion criteria

Patients will be eligible for the trial (1) if they are considered to have contraindications to pharmacological thromboprophylaxis within 72 hours of hospital admission by their attending intensivist, trauma or spinal surgeon or neurosurgeon; and (2) ISS >15 (see online supplementary appendix 1). A list of contraindications to pharmacological VTE prophylaxis is described in the case record form (CRF) and web data portal.

Exclusion criteria

severe head or systemic injury where death within 48–72 hours is expected;

attending clinicians judge that patients are at low risk of bleeding, without contraindications to pharmacological VTE prophylaxis (as listed in the CRF) and can receive pharmacological thromboprophylaxis within 3 days after major trauma;

patients who have CT evidence of PE on admission to the hospital after trauma;

patients who have been treated with full systemic anticoagulation by warfarin, UFH or LMWH for pre-existing medical disease (eg, patients with chronic atrial fibrillation requiring systemic anticoagulation) until admission due to trauma;

pregnancy;

aged <18 years old;

the IVC filter cannot be inserted within 72 hours of trauma admission.

Study intervention and follow-up

In this study, the types of retrievable IVC filters used will be determined by the usual standard practice of the study centres, and will be inserted by a trained interventional radiologist either in the X-ray department or ICU. Dates of insertion and removal of the IVC filter will be recorded. All IVC filters will be removed before hospital discharge or 90 days after the trauma, unless the clinicians believe that the IVC filter should be left for longer than this predefined period due to a strong clinical indication. The reasons for leaving the IVC filters will be recorded for those that are left in situ for >90 days. Currently, there is a WA statewide standardised protocol to ensure all retrievable IVC filters are removed by the Department of Radiology within 60–90 days. All complications related to IVC filters will be recorded (eg, migration/displacement, caval occlusion) and managed according to the best clinical practice available. Mechanical complications related to the IVC filters are considered as severe adverse events (SAEs). All retrieved filters will be examined by the Department of Medical Engineering and Physics at Royal Perth Hospital for filter fractures, clot loads and mechanical properties (spring load of the ‘legs’, hardness of the alloy, chemical composition) as a substudy. All trauma deaths including those included in this study will be referred to the Coroner’s office for postmortem examination to exclude fatal PE. Clinical follow-up will be maintained up to day 90 after the injury (or hospital discharge whichever is longer) and subsequent further long-term follow-up will be achieved using data linkage of WA statewide health data for patients recruited in WA.

We adopt a proactive approach to detect asymptomatic DVT and symptomatic PE events in this study. Routine compression ultrasonography of the thighs and calf of all patients will be performed at 2 weeks after study enrolment, or later if it is not possible at that time (eg, external fixation of lower limb fractures). Although routine lower limbs ultrasonography screening may reduce the risk of PE in seriously injured patients,62 it may not be cost-effective and is currently not used in the study centres nor most trauma centres in Australia.63

Imaging techniques used to diagnose PE and when this will be performed is at the discretion of the attending clinicians according to their clinical suspicion for PE. However, CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) is considered mandatory if one or more of the following conditions or situations occur unless a prior CTPA has already been performed within the last 3 days:

hypotension with systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg for longer than 30 min;

unexplained chest pain;

hypoxia requiring ≥6 L/min of oxygen or 50% inspired oxygen to maintain arterial oxygen saturation >94%.

Routine imaging to screen for asymptomatic PE is not used in this study. Routine lower limb venography will not be used. D-dimers also will not be used to screen for DVT or PE in this study because of its very low specificity and positive predictive value in trauma patients.

Concurrent treatments

The study is not blinded and attending clinicians should initiate pharmacological VTE prophylaxis as appropriate or as soon as possible. The trial recommends initiation of pharmacological VTE prophylaxis within 7 days of injury regardless of whether the patients have received an IVC filter. Because this is a pragmatic study, the decisions about when to initiate UFH or LMWH and the doses needed after study enrolment are at the discretion of the attending clinicians and the data will be recorded. Intravenous low-dose heparin (<800 units/hour) as an anticoagulant for continuous renal replacement therapy is not contraindicated in the study, but patients who require full systemic anticoagulation by either UFH or LMWH before randomisation are not eligible for the study (eg, patients with atrial fibrillation requiring systemic anticoagulation). Antiplatelet agents for new or pre-existing medical conditions (eg, coronary artery disease, stroke, vertebral artery dissection) are permissible.

All patients will receive mechanical DVT prophylaxis, in the form of lower limb compression devices, to the leg that is not injured. There is no restriction on attending clinicians to insert an IVC filter for VTE prophylaxis for patients randomised to the control group if there is a well-established indication to do so (eg, development of VTE with absolute contraindications to initiate systemic anticoagulation according to the treating clinicians) but these data will be recorded.

Primary endpoints

The composite endpoint of (A) PE as demonstrated by CTPA, high probability ventilation/perfusion scan, transoesophageal echocardiography (by showing clots within pulmonary arterial trunk), pulmonary angiography or postmortem examination during the same hospitalisation or 90-day after trauma whichever is earlier; and (B) hospital mortality.

The total cost of treatment including the costs of an IVC filter, total number of CT and ultrasound scans required, length of ICU and hospital stay, procedures and drugs required to treat PE or complications related to the IVC filter.

Secondary endpoints

All complications related to an IVC filter, including displacement of the filter, erosion of IVC, inducing lower limb DVT and failure to remove the IVC filter in the recommended period.

Risk of fatal PE and non-fatal PE in patients who do not receive any pharmacological VTE prophylaxis within 7 days of major trauma.

Hospital mortality or 90-day mortality whichever is earlier.

- Risk of bleeding after study enrolment

- Major bleeding—contributing to death, at a critical site (eg, intracranial, spinal, epidural, airway haemorrhage), requiring transfusion (of either red blood cells, platelets or fresh frozen plasma) or a reduced haemoglobin >2 g/dL within 24 hours.

- Non-major but clinically relevant bleeding—requiring new medical interventions (eg, gastrointestinal endoscopy, local or systemic drugs to control bleeding).

- Minor bleeding—not requiring new medical intervention (eg, mild haematuria, coffee-ground nasogastric aspirate, skin bruises).

Participant withdrawal criteria and management

side effects of an IVC filter are detected and removal of the filter is deemed to confer more benefits than harms by the attending clinicians, but all complications related to the IVC filter and reasons for removal of the filter will be recorded and all patients will be followed up for at least 90 days after enrolment (or hospital discharge whichever is longer) and further follow-up on health outcomes is achieved by data linkage;

no participants withdrawing from the trial will be replaced and the proposed sample size has allowed for 20% dropout or crossover between the two treatment arms.

Data collection (table 1)

Table 1.

Baseline and clinical data collected until day 90 after enrolment for patients included in the trial

| Baseline characteristics | Concurrent interventions and investigations | Bleeding and transfusion outcomes | VTE and other important clinical outcomes |

| Demographic factors | Total number of CTPA or echocardiography, V/Q perfusion scan | Major bleeding—contributing to death, at a critical site (eg, intracranial, spinal, epidural, airway haemorrhage), requiring transfusion (of either red blood cells, platelets, or fresh frozen plasma) or a reduced haemoglobin >2 g/dL within 24 hours | Occurrence of symptomatic PE or DVT and duration between hospital admission and occurrence of VTE, including fatal PE in the postmortem examination |

| Comorbidities including previous history of VTE and body mass index | The duration between hospital admission and the first attempt to diagnose PE by any form of imaging modality | Non-major but clinically relevant bleeding—requiring new medical interventions (eg, gastrointestinal endoscopy, local or systemic drugs to control bleeding) | Occurrence of asymptomatic DVT on lower limb screening ultrasound within 14 days of study enrolment |

| Relevant medication history including antiplatelet agents, hormonal replacement therapy or oral contraceptive pills for female patients | Duration between hospital admission and the time to start the first dose of antithrombotic prophylaxis | Minor bleeding—not requiring new medical intervention (eg, mild haematuria, coffee-ground nasogastric aspirate, skin bruises) | ICU, hospital and 90-day mortality (if length of hospital stay is >90 days) |

| Pattern of injuries, ISS and CT brain findings including Marshall CT brain grading | Whether full anticoagulation is used, the indications for such therapy and the duration between hospital admission and full systemic anticoagulation | Total amount of allogeneic blood products needed within 90 days after enrolment | Length of ICU and hospital stay. For patients with ICU readmission, the reasons for ICU readmission will be noted and the total number of ICU days of all ICU admission during the same hospitalisation will be calculated |

| The type of the IVC filter used for the study patients | Whether UFH or LMWH is used for DVT/PE prophylaxis, the dose used, and duration between hospital admission and initiation of anticoagulant prophylaxis | Occurrence of acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy | |

| Whether sequential lower limb compression device is used and the duration between hospital admission and the time this device is commenced and the total time of use of this type of device | Total length of mechanical ventilation, including invasive and non-invasive ventilation | ||

| Use of femoral vein as an access for central venous catheter and dialysis catheter | Use of all forms of vasopressor/inotropic support and the total days of requiring such support after study enrolment | ||

| Use of intracranial pressure monitor | Duration of filter left in situ and all complications related to IVC filters (eg, migration/displacement, caval occlusion, filter thrombosis) | ||

| The total number of operations required after study enrolment, and reasons for the operations and the operative diagnoses | |||

| Long-term VTE and complications related to the use of IVC filters beyond day 90 (up to 5 years) using data linkage techniques |

CTPA, CT pulmonary angiography; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; ICU, intensive care unit; ISS, Injury Severity Score; IVC, inferior vena cava; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; PE, pulmonary embolism; UFH, unfractionated heparin; V/Q, ventilation/perfusion; VTE, venous thromboembolic events.

The following data will also be obtained for all patients enrolled in the study and these characteristics will be used to generate a TESS to ensure that the randomisation is balanced, in terms of VTE risk, between the two groups (see online supplementary appendix 2).

demographics;

previous history of DVT/PE (see online supplementary appendix 3);

comorbidity including the history of smoking and drug use before the injury;

injury pattern and severity including ISS (see online supplementary appendix 1);

neurological signs and CT findings on admission for patients with head injury;

body mass index;

medications before and after the injury: antiplatelet agents, hormonal replacement therapy or oral cntraceptive (OC) pills for female patients;

the duration between injury and hospital admission;

the duration between hospital admission and IVC filter insertion for patients who are randomised into IVC group and also for patients who require IVC filter in the control group due to clinical reason (ie, crossed over for clinical reason such as DVT but with active contraindication for anticoagulation);

total number of CTPA or other imaging modalities used (eg, echocardiography, ventilation / perfusion (V/Q) or perfusion scan, and so on);

the duration between hospital admission and the first attempt to diagnose PE by any form of imaging modality;

duration between hospital admission and the time to start the first dose of antithrombotic prophylaxis;

whether full anticoagulation is used, the indications for such therapy and the duration between hospital admission and full systemic anticoagulation;

whether UFH or LMWH is used for DVT/PE prophylaxis, the dose used, and duration between hospital admission and initiation of pharmacological thromboprophylaxis;

whether sequential lower limb compression device is used and the duration between hospital admission and the time this device is commenced and the total time of use of this type of device;

occurrence of DVT or PE and duration between hospital admission and occurrence of DVT/PE;

occurrence of acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy;

use of femoral vein as an access for central venous catheter and dialysis catheter;

bleeding complications and interventions required for all bleeding complications after study enrolment as defined in the secondary endpoints;

ICU, hospital and 90-day mortality (if length of hospital stay is >90 days);

length of ICU and hospital stay: for patients with ICU readmission, the reasons for ICU readmission will be noted and the total number of ICU days of all ICU admission during the same hospitalisation will be calculated;

total length of mechanical ventilation, including invasive and non-invasive ventilation;

use of all forms of vasopressor/inotropic support and the total days of requiring such support after study enrolment;

use of intracranial pressure monitor;

the total number of operations required after study enrolment, reasons for the operations and the operative diagnoses; in addition, the number of surgical procedures that require cessation of heparin and the duration of withholding DVT prophylaxis each time will be recorded;

the type of the IVC filter used for the study patients and dates of insertion and removal of the IVC filter; for IVC filters that are left in situ for >90 days, the reasons for leaving the IVC filters will be recorded;

proportion of IVC filters found to have clots after being retrieved;

all complications related to IVC filters (eg, migration/displacement, caval occlusion); mechanical complications related to the IVC filters are considered as SAEs;

we will also use the unique data linkage unit in WA to evaluate hospital readmissions due to all causes, VTE, complications related to the IVC filters and long-term survival at about 3–5 years after study enrolment as a substudy of this randomised controlled study.

Sample size calculation

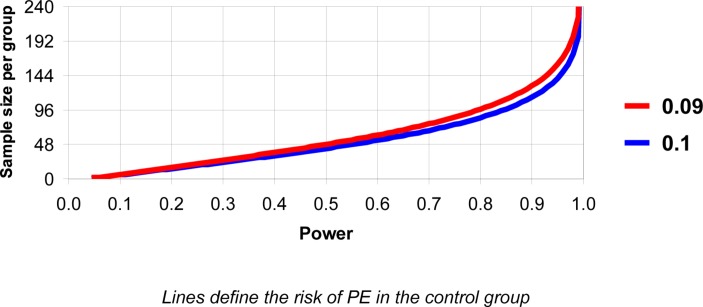

Although IVC filters are increasingly used for thromboprophylaxis in many patients with trauma, their clinical effectiveness has never been well documented. They are invasive, expensive and have significant complications some of which are life threatening. It is important to demonstrate clinical superiority before they are widely used in patients who are already at risk of mortality and, hence, a superiority trial rather than a non-inferiority trial is preferred. We are planning a study of independent treatment cases and placebo controls with one control per case. The incidence of asymptomatic PE between 3 and 7 days after moderate to major trauma is extremely high (24%) despite LMWH or UFH prophylaxis. Prior data indicate that the PE rate among patients who are at high risk of VTE without thromboprophylaxis (similar to our control patients) is >0.09 (or 9%). The relatively high incidence of PE is expected because (A) we use a proactive approach to detect mildly symptomatic PE, and (B) we have chosen the group of patients with trauma who are at extreme risk of VTE and, at the same time, cannot receive pharmacological thromboprophylaxis. The TESS score of these patients is expected to be >10. Evidence suggested that IVC filters are highly effective in reducing PE. If the PE rate of the intervention group is close to 0.5%, we will need to study 97 experimental subjects and 97 control subjects to be able to reject the null hypothesis that the failure rates for experimental and control subjects are equal with probability (power) 0.8 (or 0.9 if the baseline risk of PE is 10%). We assume there will be a small proportion of patients who will have study intervention crossed over between the two groups. Therefore, the total sample size of this study is 240 (120 per group), allowing up to 20% of the study subject crossed over between the control and intervention groups without affecting the power of the study (see figure 2). If an IVC is associated with an increased risk of lower limb DVT, this sample size will also have >80% power to detect an increased risk of DVT due to the IVC filter from 10% to 25%.

Figure 2.

Graph showing the power of the study in relation to the sample size in each study group and incidence of PE in the control group. PE, pulmonary embolism.

Data analysis plan

An interim analysis is not planned because this will compromise the power of the proposed study. However, fatal PE and SAEs will be reported to the ethics committee and monitored by an independent DMSC comprising two members who have experience in conducting clinical trials related to trauma and critical illness. Statistically, at least four fatal PEs all occurring only in the control group of 100–120 patients are needed to conclude that without IVC (or control group) would lead to an increased risk of fatal PE in the study population and this will terminate the entire trial before the completion of the study with the proposed sample size (n=240). Any significant side effects experienced by participants of the trial will be addressed according to the standard clinical management procedures that this may include early removal of the IVC filter. The primary and secondary outcomes will be analysed by an intention-to-treat principle, and as such, any patients that cross over into the other group will be analysed as the group they are originally allocated to.

Categorical and continuous baseline variables and outcomes with skewed distributions will be compared by χ2 test and Mann-Whitney U test, respectively. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis will be used to assess whether early use of retrievable IVC filters will affect the time for the patients to experience the first composite endpoint event (eg, PE or death) within 90 days of randomisation. A predefined restricted or subgroup analysis on risk of fatal PE and non-fatal PE in patients who do not receive any pharmacological VTE prophylaxis within 7 days of major trauma is planned.

As for the economic analysis, it will comprise (A) the net resource cost of IVC compared with the status quo without IVC (cost analysis) and (B) comparison of net resource use with net health benefits (cost-effectiveness).

A. Cost analysis

The total cost of treatment using an IVC filter includes the device itself, the consumables required for insertion and removal, the costs of personnel required for the procedure and costs of complications. Cost components for both arms of the trial which require analysis include length of index hospital stay including number of days in ICU, readmission days including ICU, pharmaceuticals required to treat PE, DVT prophylaxis, associated investigations including all X-rays, CTPA, ultrasonography and any other associated procedures. Follow-up will extend to 90 days postprocedure in the first instance; furthermore, long-term outcomes including survival and venous thromboembolic complications and the cost-effectiveness in preventing these complications beyond day 90 will be assessed through use of linked health data. Costs will be drawn from hospital finance data where possible, but all resources will be collected in standard units and otherwise quantified using standard Australian resource data such as the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) for medical procedures and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) for pharmaceuticals. Costs will be standardised to 2015 Australian dollars. The cost analysis will take the perspective of the Australian health system. Because different institutions may have ways of managing patients with trauma and hence also the costs needed, we will also analyse the cost outcomes using the funding provided to each recruited patient according to the Australian Activity-Based Funding model.

Current cost data estimates

It is estimated that the total cost of the procedure using IVF filters is approximately $A6000, comprising: $3000—IVF filter, $3000—consumables for insertion + labour costs for insertion and removal.64 Given the significant number needed to treat (estimated to be 10), net savings are unlikely to accrue unless additional individual benefits are evident such as survival and venous insufficiency after VTE. Given estimates of 20% expected DVT and 9%–10% expected PE in the study cohort, the device will only be cost saving if PE costs on average, more than $A60 000. However, if there is a difference in life saved after the use of IVC filters—that is a reduction in fatal PE as suggested by existing observational studies35—this will contribute enormously to cost-effectiveness (as distinct from cost savings).

B. Cost-effectiveness

Costs of the procedure will be compared with health outcomes as determined from the trial. The cost analysis as described above will indicate whether IVC filters provide a net saving to the healthcare system. A net saving in costs combined with a net health benefit suggests a dominant health intervention strategy. In the event that the IVC filters demonstrate health benefits at some cost, formal cost-effectiveness analysis can provide information around the relative health benefits for a given cost, compared with alternative resource demands, such as comparable procedures.

Using mortality outcomes, both at 90 days after admission and long term after hospital discharge obtained by linked health data, cost per life year gained can be estimated. Long-term outcomes can also be estimated using Markov decision analysis based on probabilities from the literature. Sensitivity analysis will be undertaken to test robustness of the parameters, to identify cost drivers and to estimate conditions under which the procedure is cost-effective. Cost-effectiveness ratios can be compared with similar procedures to estimate potential acceptability for wider policy.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been approved by the ethics committees of the Coroner’s Court of Western Australia (EC03-14), Royal Perth Hospital (14-139; consent forms in online supplementary appendix 4), Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital (2014-161), Fiona Stanley Hospital (14-139) and Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital (15/QRBW/437). Informed consent information forms can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author of this manuscript (KMH). This study has been registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trial Register (ACTRN12614000963628). A manuscript with the results of the primary clinical outcome and secondary outcomes will be published in a peer-reviewed journal. Separate manuscripts will be written on cost-effective analyses, determinants of the mechanical complications of the IVC filters and long-term outcomes after use of retrievable IVC filters, and these will also be submitted for publication in peer-reviewed journals. Chief investigators listed in this study protocol and those who contribute to the completion of the trial including drafting and critical revising of the final manuscripts will be the authors of the published manuscripts. Patient-level raw data of this study can be obtained from the corresponding author and the full data set may also be deposited in open clinical data registry if funding is available on completion of all substudies.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: KMH, SR, SH, RZ, AK, JL, BW, AH, EG and TC were all involved in conception and trial design. All authors were involved in drafting of the article and critical revision of the article for important intellectual content. All the authors were involved in final approval of the article. KMH provided statistical expertise and EG provided expertise on economic analysis of the study. Preparing study design, collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data; writing of the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication are the responsibilities of KMH.

Funding: This work was supported by the State Health Research Advisory Council (SHRAC) of Western Australia. KMH is funded by Raine Medical Research Foundation and WA Health through the Raine Clinical Research Fellowship. The funding agencies play no role in the design of the study and any process in the conduction of this trial including data analysis and the decision to publish.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Coroner’s Court of Western Australia (EC03-14), Royal Perth Hospital (14-139), Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital (2014-161), Fiona Stanley Hospital (14-139) and Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital (15/QRBW/437).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Galson SK. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Deep Vein Thrombosis andPulmonary Embolism. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44178/

- 2. National Quality Forum. National Voluntary Consensus Standards for Prevention and Care of venous thromboembolism: additional performance measures, 2008. http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2008/10/National_Voluntary_Consensus_Standards_for_prevention_and_Care_of_Venous_Thromboembolism__Additional_Performance_Measures.aspx

- 3. The burden of venous thromboembolism in Australia. Report by Access Economics Pty Limited for the Australian and New Zealand Working Party on the management andprevention of venous thromboembolism in Australia, 2008. https://www.deloitteaccesseconomics.com.au/uploads/File/The_burden_of_VTE_in_Australia.pdf

- 4. Cohen AT, Agnelli G, Anderson FA, et al. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) in Europe. the number of VTE events and associated morbidity and mortality. Thromb Haemost 2007;98:756–64. 10.1160/TH07-03-0212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohen AT. The burden of venous thromboembolism in the hospital setting. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb 2009-2010:102. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cohen AT, Tapson VF, Bergmann JF, et al. Venous thromboembolism risk and prophylaxis in the acute hospital care setting (ENDORSE study): a multinational cross-sectional study. Lancet 2008;371:387–94. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60202-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cohen AT. Prevention of postoperative venous thromboembolism. BMJ 2009;339:b4477. 10.1136/bmj.b4477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schultz DJ, Brasel KJ, Washington L, et al. Incidence of asymptomatic pulmonary embolism in moderately to severely injured trauma patients. J Trauma 2004;56:727–33. 10.1097/01.TA.0000119687.23542.EC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cook DJ, Crowther MA. Thromboprophylaxis in the intensive care unit: focus on medical-surgical patients. Crit Care Med 2010;38:S76–S82. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c9e344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF. Prevention of venous thromboembolism:American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8thEdition). 133, 2008:381S–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Joint Commission International. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) measures. https://www.jointcommission.org/venous_thromboembolism/

- 12. Kakkar AK, Davidson BL, Haas SK; Investigators Against Thromboembolism (INATE) Core Group. Compliance with recommended prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism: improving the use and rate of uptake of clinical practice guidelines. J Thromb Haemost 2004;2:221–7. 10.1111/j.1538-7933.2004.00588.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ginzburg E, Dujardin F. Physicians' perceptions of the definition of Major bleeding in Major orthopedic surgery: results of an international survey. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2011;31:188–95. 10.1007/s11239-010-0498-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tapson VF, Decousus H, Pini M, et al. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients: findings from the International Medical Prevention Registry on venous thromboembolism. Chest 2007;132:936–45. 10.1378/chest.06-2993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Steele N, Dodenhoff RM, Ward AJ, et al. Thromboprophylaxis in pelvic and acetabular trauma surgery. the role of early treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005;87:209–12. 10.1302/0301-620X.87B2.14447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nathens AB, McMurray MK, Cuschieri J, et al. The practice of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in the Major trauma patient. J Trauma 2007;62:557–63. 10.1097/TA.0b013e318031b5f5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lilly CM, Liu X, Badawi O, et al. Thrombosis prophylaxis and mortality risk among critically ill adults. Chest 2014;146:51–7. 10.1378/chest.13-2160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ho KM, Chavan S, Pilcher D. Omission of early thromboprophylaxis and mortality in critically ill patients: a multicenter registry study. Chest 2011;140:1436–46. 10.1378/chest.11-1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ho KM, Litton E. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in hospitalized elderly patients: time to consider a 'MUST' strategy. J Geriatr Cardiol 2011;8:114–20. 10.3724/SP.J.1263.2011.00114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kakkos SK, Caprini JA, Geroulakos G, et al. Combined intermittent pneumatic leg compression and pharmacological prophylaxis for prevention of venous thromboembolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;9:CD005258. 10.1002/14651858.CD005258.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Eldridge D. Injury among young Australians. Bulletin 60: AIHW, 2008. http://www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=6442452801 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guyatt GH, Akl EA, Crowther M, et al. American College of Chest PhysiciansAntithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis Panel. Executive summary:Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College ofChest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012;141(2 Suppl):7S–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Paciaroni M, Ageno W, Agnelli G. Prevention of venous thromboembolism after acute spinal cord injury with low-dose heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin. Thromb Haemost 2008;99:978–80. 10.1160/TH07-09-0540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rosenthal D, McKinsey JF, Levy AM, et al. Use of the Greenfield filter in patients with Major trauma. Cardiovasc Surg 1994;2:52–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bandle J, Shackford SR, Sise CB, et al. Variability is the standard: the management of venous thromboembolic disease following trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2014;76:213–6. 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182aa2fa9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shackford SR, Cook A, Rogers FB, et al. The increasing use of vena cava filters in adult trauma victims: data from the American College of Surgeons National Trauma Data Bank. J Trauma 2007;63:764–9. 10.1097/01.ta.0000240444.14664.5f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kaufman JA, Kinney TB, Streiff MB, et al. Guidelines for the use of retrievable and convertible vena cava filters: report from the Society of Interventional Radiology multidisciplinary consensus conference. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2006;2:200–12. 10.1016/j.soard.2006.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sing RF, Rogers FB, Novitsky YW, et al. Optional vena cava filters for patients with high thromboembolic risk: questions to be answered. Surg Innov 2005;12:195–202. 10.1177/155335060501200303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rogers FB, Strindberg G, Shackford SR, et al. Five-year follow-up of prophylactic vena cava filters in high-risk trauma patients. Arch Surg 1998;133:406–11. 10.1001/archsurg.133.4.406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stawicki SP, Sims CA, Sharma R, et al. Vena cava filters: a synopsis of complications and related topics. J Vasc Access 2008;9:102–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cherry RA, Nichols PA, Snavely TM, et al. Prophylactic inferior vena cava filters: do they make a difference in trauma patients? J Trauma 2008;65:544–8. 10.1097/TA.0b013e31817f980f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Young T, Tang H, Aukes J, et al. Vena caval filters for the prevention of pulmonary embolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;4:CD006212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chiasson TC, Manns BJ, Stelfox HT. An economic evaluation of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis strategies in critically ill trauma patients at risk of bleeding. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000098. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rajasekhar A, Lottenberg L, Lottenberg R, et al. A pilot study on the randomization of inferior vena cava filter placement for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in high-risk trauma patients. J Trauma 2011;71:323–9. 10.1097/TA.0b013e318226ece1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Haut ER, Garcia LJ, Shihab HM, et al. The effectiveness of prophylactic inferior vena cava filters in trauma patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Surg 2014;149:194–202. 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Knudson MM, Ikossi DG, Khaw L, et al. Thromboembolism after trauma: an analysis of 1602 episodes from the American College of Surgeons National Trauma Data Bank. Ann Surg 2004;240:490–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Smouse B, Johar A. Is market growth of vena cava filters justified? A review of indications, use, and market analysis. Endovascular Today 2010:74–7. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hope WW, Demeter BL, Newcomb WL, et al. Postoperative pulmonary embolism: timing, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Am J Surg 2007;194:814–9. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stefanidis D, Paton BL, Jacobs DG, et al. Extended interval for retrieval of vena cava filters is safe and may maximize protection against pulmonary embolism. Am J Surg 2006;192:789–94. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.08.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sing RF, Camp SM, Heniford BT, et al. Timing of pulmonary emboli after trauma: implications for retrievable vena cava filters. J Trauma 2006;60:732–5. 10.1097/01.ta.0000210285.22571.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Karmy-Jones R, Jurkovich GJ, Velmahos GC, et al. Practice patterns and outcomes of retrievable vena cava filters in trauma patients: an AAST multicenter study. J Trauma 2007;62:17–25. 10.1097/TA.0b013e31802dd72a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ho KM, Tan JA, Burrell M, et al. Venous thrombotic, thromboembolic, and mechanical complications after retrievable inferior vena cava filters for Major trauma. Br J Anaesth 2015;114:63–9. 10.1093/bja/aeu195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Scales DC, Riva-Cambrin J, Wells D, et al. Prophylactic anticoagulation to prevent venous thromboembolism in traumatic intracranial hemorrhage: a decision analysis. Crit Care 2010;14:R72. 10.1186/cc8980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Arnold JD, Dart BW, Barker DE, et al. Gold medal Forum winner. unfractionated heparin three times a day versus enoxaparin in the prevention of deep vein thrombosis in trauma patients. Am Surg 2010;76:563–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kurtoglu M, Yanar H, Bilsel Y, et al. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after head and spinal trauma: intermittent pneumatic compression devices versus low molecular weight heparin. World J Surg 2004;28:807–11. 10.1007/s00268-004-7295-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Eppsteiner RW, Shin JJ, Johnson J, et al. Mechanical compression versus subcutaneous heparin therapy in postoperative and posttrauma patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg 2010;34:10–19. 10.1007/s00268-009-0284-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Latronico N, Berardino M. Thromboembolic prophylaxis in head trauma and multiple-trauma patients. Minerva Anestesiol 2008;74:543–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mismetti P, Rivron-Guillot K, Quenet S, et al. A prospective long-term study of 220 patients with a retrievable vena cava filter for secondary prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest 2007;131:223–9. 10.1378/chest.06-0631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Berber O, Vasireddy A, Nzeako O, et al. The high-risk polytrauma patient and inferior vena cava filter use. Injury 2017. pii: ;48:1400–4. 10.1016/j.injury.2017.04.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sarosiek S, Rybin D, Weinberg J, et al. Association between Inferior Vena Cava Filter insertion in Trauma Patients and In-Hospital and overall mortality. JAMA Surg 2017;152:75–81. 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.3091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rogers FB, Cipolle MD, Velmahos G, et al. Practice management guidelines for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in trauma patients: the EAST practice management guidelines work group. J Trauma 2002;53:142–64. 10.1097/00005373-200207000-00032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Knudson MM, Lewis FR, Clinton A, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism in trauma patients. J Trauma 1994;37:480–7. 10.1097/00005373-199409000-00025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Khansarinia S, Dennis JW, Veldenz HC, et al. Prophylactic Greenfield filter placement in selected high-risk trauma patients. J Vasc Surg 1995;22:231–6. 10.1016/S0741-5214(95)70135-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ho KM, Burrell M, Rao S, et al. Incidence and risk factors for fatal pulmonary embolism after Major trauma: a nested cohort study. Br J Anaesth 2010;105:596–602. 10.1093/bja/aeq254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ho KM, Burrell M, Rao S. Extracranial injuries are important in determining mortality of neurotrauma. Crit Care Med 2010;38:1562–8. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e2ccd8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ho KM, Chavan S. Prevalence of thrombocytosis in critically ill patients and its association with symptomatic acute pulmonary embolism. A multicentre registry study. Thromb Haemost 2013;109:272–9. 10.1160/TH12-09-0658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rogers FB, Shackford SR, Horst MA, et al. Determining venous thromboembolic risk assessment for patients with trauma: the Trauma Embolic Scoring System. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;73:511–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ho KM, Rao S, Rittenhouse KJ, et al. Use of the Trauma Embolic Scoring System (TESS) to predict symptomatic deep vein thrombosis and fatal and non-fatal pulmonary embolism in severely injured patients. Anaesth Intensive Care 2014;42:709–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ho KM, Pavey W. Applying the cell-based coagulation model in the management of critical bleeding. Anaesth Intensive Care 2017;45:166–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ho KM, Duff OC. Predictors of an increased in vitro thrombotic and bleeding tendency in critically ill trauma and non-trauma patients. Anaesth Intensive Care 2015;43:317–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ho KM, Tan JA. Can the presence of significant coagulopathy be useful to exclude symptomatic acute pulmonary embolism? Anaesth Intensive Care 2013;41:322–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Allen CJ, Murray CR, Meizoso JP, et al. Surveillance and early management of Deep Vein Thrombosis decreases rate of pulmonary embolism in High-Risk Trauma Patients. J Am Coll Surg 2016;222:65–72. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sud S, Mittmann N, Cook DJ, et al. Screening and prevention of venous thromboembolism in critically ill patients: a decision analysis and economic evaluation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;184:1289–98. 10.1164/rccm.201106-1059OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Spangler EL, Dillavou ED, Smith KJ. Cost-effectiveness of guidelines for insertion of inferior vena cava filters in high-risk trauma patients. J Vasc Surg 2010;52:1537–45. 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.06.152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-016747supp001.pdf (145.4KB, pdf)