Abstract

Objectives

Fever is a common symptom of mostly benign illness in young children, yet concerning for parents. The aim of this study was to describe parental knowledge, attitudes and beliefs regarding fever in children aged ≤5 years of age.

Design

A cross-sectional study using a previously validated questionnaire. Results were analysed using descriptive statistics and multivariable logistic regression.

Setting

Purposively selected primary schools (n=8) in Cork, Ireland, using a paper-based questionnaire. Data were collected from a cross-sectional internet-based questionnaire with a convenience sample of parents via websites and web pages (n=10) previously identified in an interview study.

Participants

Parents with at least one child aged ≤5 years were invited to participate in the study.

Main outcome measures

Parental knowledge, attitudes and beliefs when managing fever in children.

Results

One thousand one hundred and four parents contributed to this research (121 parents from schools and 983 parents through an online questionnaire). Almost two-thirds of parents (63.1%) identified temperatures at which they define fever that were either below or above the recognised definition of temperature (38°C). Nearly two of every three parents (64.6%) alternate between two fever-reducing medications when managing a child’s fever. Among parents, years of parenting experience, age, sex, educational status or marital status did not predict being able to correctly identify a fever, neither did they predict if the parent alternated between fever-reducing medications.

Conclusions

Parental knowledge of fever and fever management was found to be deficient which concurs with existing literature. Parental experience and other sociodemographic factors were generally not helpful in identifying parents with high or low levels of knowledge. Resources to help parents when managing a febrile illness need to be introduced to help all parents provide effective care.

Keywords: Key Words:child, fever, temperature, parents, knowledge, attitude

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A large number of parents were recruited for this study which is one of the major strengths of this study.

Beliefs and opinions were captured in a non-clinical setting which may portray more realistic attitudes and concerns than those captured at the point of care or in acute care settings.

The questionnaire used in this study was previously validated.

A limitation of the study is that we cannot estimate response rate from the web-based study.

Participants were mainly mothers or had third level education which limits generalisability of findings.

Introduction

Fever, defined as a regulated rise in temperature, is common in childhood,1–4 however fever episodes are rarely a symptom of serious illness.1 5 6

Fever is commonly defined as a temperature of 38°C or above.7 8 Fever on its own does not require treatment,9 and guidelines recommend that antipyretics should only be used when the child is also distressed or in pain.4 However, research suggests that parents often misuse antipyretics by overdosing or underdosing,10 11 or by routinely alternating between antipyretics when managing a fever,12 despite guidance to the contrary.4

Studies examining parents’ attitudes and beliefs around fever are limited.13 The majority of published studies were conducted in secondary care where perceptions may be biased as children may be acutely unwell, placing stress on the parents and possibly influencing responses.13 Consequently, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, together with their guideline development group have suggested that studies examining home antipyretic use and parental help-seeking behaviour be completed.6 To help address these gaps, we surveyed parental knowledge, attitudes and beliefs around childhood fever and febrile illness.

Methods

Cross-sectional data for this study were collected from parents with at least one child aged 5 years of age or younger, and were recruited from one of two sources: purposively selected primary schools (n=8) in Cork, Ireland, and via the internet (websites and web pages n=10 (see online supplementary table 1))during December 2015 and January 2016. No major public health initiatives were initiated during that time. The schools were selected to maximise sample variation, and included urban and rural settings; large and small schools; and schools that were, and were not designated as delivering education to children and young people who are experiencing, or are at risk of experiencing, educational disadvantage. The websites and web pages used to recruit parents for the internet questionnaire were selected from previous qualitative work with parents (see online supplementary table 1).14 A review of existing literature suggested a sample size of ≥600 parents would be adequate to ensure generalisability of responses.7 12 15–23 Data collection in schools took place over 1 week in December 2015, while responses from the internet questionnaire were obtained in January 2016. There were no incentives for participation. School based parents provided written informed consent, whereas consent was implied from online participation.

bmjopen-2016-015684supp001.pdf (93.8KB, pdf)

The questionnaire administered in this study was developed and used in previous research.7 24–26 The questionnaire was modified to reflect custom and practice in Ireland and piloted with a sample of five parents. It consisted of 38 questions with subthemes. Response options, including yes/no, agree/disagree and Likert Scales were used. The questionnaire assessed parental knowledge, help-seeking behaviours and expectations, needs for additional resources, fever management practices, use of pharmaceutical products, and concerns, attitudes (feelings about) and beliefs.

Respondents’ answers were entered into a Microsoft Excel (2013) data file. Available cases were analysed. Paper-based responses were entered by RH (a researcher not involved in the care of participants). A random sample of 20% of paper-based responses were checked for accuracy by MK. Where data were missing, available cases were analysed. Data were analysed using SPSS V.22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA) and R V.3.3.1.27 Categorical variables were described by the count and proportion in each category. Continuous variables were described by their means and standard deviations (SDs), or by their medians and inter quartile ranges (IQRs), depending on whether they were normally distributed or not.

Crude associations between categorical variables were assessed using Pearson’s χ2 test. p Values <0.05 were considered statistically significant, given a null hypothesis of independence. Multivariable logistic regression was used to estimate covariate adjusted associations, reported as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), between key sociodemographic predictors (years of parental experience, respondent age, sex, educational level and marital/partner status) and each the following dependent variables: whether the parent identified the correct temperature indicative of a fever, and whether parents reported alternating fever-reducing medications.

Participant involvement

A previous qualitative study on this topic conducted by the research team14 found that parents identified fever as a priority when caring for young children, however parents perceived that they lacked knowledge. Following on from this study, a small number of parents were asked to participate in the design of this study. Parents were not involved in recruiting other parents. Study participants who indicated that they would like to receive a copy of the final report were provided with the report.

Results

Parents’ characteristics

A total of 121 parents recruited from schools completed the paper-based questionnaire (response rate 42%), while 983 parents contributed using the online questionnaire. Overall, 1104 parents contributed to this research. Although the majority of parents were white Irish (91.8%, n=746), parents representing 34 nationalities participated in the study.

Demographic information is listed in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information

| Overall | Website/web page sample | School sample | ||

| Gender | N Male Female |

817 4.5% 95.5% |

696 3.7% 96.3% |

121 9.1% 90.9% |

| Age of parents | N Range (years) Mean (SD) |

805 20–55 35.3 (4.8) |

685 20–51 34.7 (4.5) |

120 26–55 38.3 (4.7) |

| Number of children (n=817) | N Range Median (IQR) |

817 1–7 2 (2) |

696 1–6 2 (2) |

121 1–7 2 (2) |

| Education level | N Primary level Secondary level Third level |

816 0.2% 11.6% 88.2% |

696 0.3% 11.4% 88.4% |

120 0% 13.3% 86.7% |

| Marital status/living situation | N Married Cohabiting Single Divorced Widowed Civil partnership |

816 79.3% 15.6% 3.3% 1% 0.6% 0.2% |

696 77.6% 17.1% 3.3% 1.1% 0.6% 0.3% |

120 89.2% 6.7% 3.3% 0% 0.8% 0% |

Knowledge

Parents (n=1104) indicated that they considered temperatures between 36°C and over 40°C indicative of fever. Almost two-thirds of parents (63.1%) identified temperatures at which they define fever that were either below (44%) or above (19.1%) the recognised definition of temperature (38°C).7 8 Logistic regression analysis showed no apparent associations between reporting the correct definition of fever temperature and years of parenting experience or key sociodemographic factors (see online supple mentary table 2).

Parents illustrated a good level of knowledge regarding infections and medication. Most parents (94.9% n=971) believed that the majority of children with a fever did not need an antibiotic, while 89.4% (n=915) were aware that antibiotics are used to cure infections caused by bacteria. Logistic regression analysis with parents’ knowledge of antibiotics as the dependent variable found no statistically significant associations between this and years of parenting experience or key sociodemographic factors (see online supplementary table 3). The majority of parents, 89.7% (n=917), knew that antibiotics are not used to cure viral infections. Female sex and having a third level education were independently associated with correctly answering that antibiotics are not used to cure infections caused by viruses (see online supplementary table 3).

Help seeking and expectations

A large proportion of parents (69.8% n=709) had visited the general practitioner (GP) because of fever in their child. Among the most common reasons selected to visit a GP when a child had fever were fever lasting more than 3 days and fever accompanied by a skin rash.

More than half of parents (51.6%) had visited a GP at an out-of-hours practice with their child because of fever. The expectations of parents when they consult GPs are shown in table 2 below. Greater than a third of parents (39.4% n=385) had seen different doctors with their child due to fever. Of these parents, 31.3% (n=111) indicated that they had received conflicting information from these doctors regarding fever in their child, for example, ‘Some say treat others say if not high let it run its course’, ‘Some say 37.5°C is fever and some say 38°C is a fever’.

Table 2.

Parental expectations when they consult a general practitioner due to fever in a child

| Obtain a physical examination | 72.2% (n=598) |

| Get advice on alarm symptoms | 9.4% (n=78) |

| Reassurance | 5.7% (n=48) |

| To obtain antibiotics | 2.9% (n=24) |

| To obtain paracetamol | 2.3% (n=19) |

Use of GP services with introduction of free GP care for children

The majority of parents (87.5% n=734) indicated that the introduction of free GP care in Ireland (July 2015)28 had not impacted on how often they have or will consult the GP in future regarding fever.

Information sources

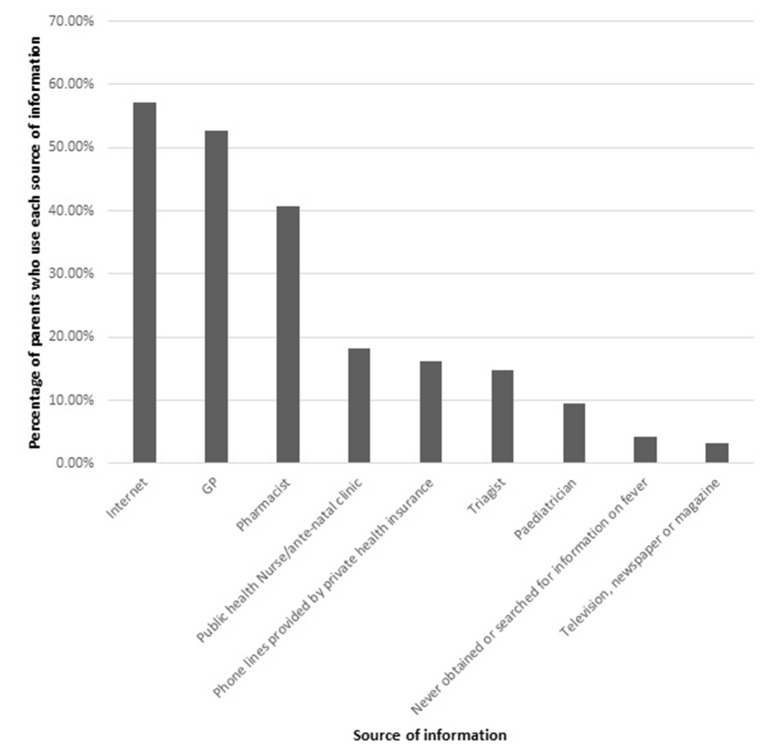

Figure 1 below illustrates sources of information used by parents.

Figure 1.

Sources of information used by parents. GP, general practitioner.

The data indicate that the majority of parents (79.5% n=660) would prefer to receive information about fever before their child gets sick. When their child is sick, almost three-quarters of parents (74.2% n=617) would prefer to receive information about fever from a GP. A further 12.3% (n=102) would be happy to receive information from a pharmacist. When their child is not sick, parents indicated that they prefer to receive information by searching for the information on the internet (28.1% n=233). A further 27% (n=224) would prefer to receive information from a nurse, 25.5% (n=211) from a pharmacist and 19.4% (n=161) from a GP.

The data indicate that parents (39.1%) would like to receive information about fever in a number of ways (verbally, on paper and through an internet site). A further 34.5% would prefer to receive information verbally and on paper.

Parents’ methods for managing childhood fever

Greater than a third of parents (37.4% n=413) give medication when fever is higher than 38°C. A minority of parents (1.2% n=13) do not give medication when their child has a fever.

More than three-quarters of parents (84.4% n=854) would not use fever-reducing medication together, however almost two-thirds of parents (64.6% n=714) alternate between fever-reducing medications. There were no apparent associations between whether the parent reported alternating fever-reducing medications and years of parenting experience or key sociodemographic factors (see online supplementary table 2). The majority of parents (81.8% n=830) indicated that they use liquid or oral forms of medication. Suppository or rectal forms of medication were favoured by 10% (n=102) of parents. A small number of parents (1.1% n=11) preferred not to use medication while 3.8% (n=39) use methods other than medication to reduce fever (e.g. tepid sponging).

Concerns, attitudes and beliefs

Almost two-thirds of parents (60.4% n=667) were worried about the consequences of fever in general, while only 27.2% (n=301) of parents were of the opinion that fever may be beneficial to their child’s health. Reasons parents selected to fear fever are shown in table 3 below.

Table 3.

Parental reasons to fear fever

| Fear of fever | Fear of dehydration (47.7% n=526) Fear of febrile convulsions (74.5% n=822) Fear of fever leading to brain damage (31.3% n=345) |

Greater than three-quarters of parents (80.5% n=890) agreed that fever causes discomfort. A statistically significant association was observed between parental worry about the consequences of fever and age of the parent χ² (4)=9.531, p=0.049. Older parents (41 years of age and older) were more likely to disagree that they worry about the consequences of fever, while younger parents (20–30 years of age) were less likely to disagree that they worry about the consequences of fever.

Discussion

The study shows that parental knowledge regarding correct definition of febrile temperature is deficient, with many parents identifying fever when temperatures are either above or below the accepted level. Parental knowledge concerning the purpose and appropriate uses of antibiotics was found to be good. Parents regularly consulted the GP when their child had a fever, however if parents consulted more than one doctor when their child had a fever (e.g. GP, out-of-hours doctor, specialist) they often received conflicting information from each doctor. Parents’ main source of information was via the internet or from a GP. The majority of parents would give medication when their child has a fever (with or without accompanying symptoms). Most parents do not give antipyretic medication together, however almost two-thirds of parents alternate between antipyretic medications to reduce fever symptoms. The majority of parents revealed that they are worried about the consequences of fever. Contrary to expectations, neither parental experience, nor key sociodemographic characteristics, were generally predictive of parental knowledge or reported behaviours.

A substantial proportion of parents involved in this research selected incorrect temperatures to define fever which is similar to existing literature.7 29–34 This study confirms that parents are still detecting and managing fevers at temperatures which are below the recommended temperature for fever (38°C).7 It also shows that parents are not identifying fevers when their child’s temperature is above normal fever temperature definition. However, considerably more of the population included in this research (63.1%) selected incorrect temperatures at which to define fever when contrasted with existing research (22%–56%).7 29–32 The higher level of incorrect answers shown in this study may reflect a more accurate representation of the prevalence of misinformation as a larger sample size increases precision of estimates. Nevertheless, the inclusion of a greater proportion of highly educated individuals when compared with previous research should have decreased the number of incorrect answers as education and health literacy are intrinsically linked.35 This study demonstrates that evidence-based information resources need to be directed at all parents as demographic factors (e.g. level of education) have no impact on parents’ knowledge of fever definition. Similar to previous research, the majority of parents were worried about the consequences of fever.1 3 7 19 21–23 31 34 36–40 This may have contributed to their frequent use of antipyretics which concurs with existing literature.3 7 11 14–16 23 Similar to previous research, parents also indicated that they prefer liquid to suppository forms of medication.14 Furthermore, parents indicated that they often alternate between fever-reducing medications but rarely use them together. Guidelines recommend that antipyretics are not used alternately to decrease the risk of dosing errors and toxicity,4 41 nonetheless previous research has indicated that parents do alternate between fever-reducing medications.3 12 40 The inclusion of a large proportion of highly educated parents may have influenced this result as previous research has shown that highly educated parents tend to medicate more regularly than less well educated individuals.11 Parents demonstrated a good level of knowledge regarding infections and antibiotic use which is similar to previous research.7 This result may reflect the education level of the included sample. However, it may also reflect improvements based on a European campaign aimed at reducing unnecessary prescriptions for antibiotics and decreasing antibiotic resistance.42

The natural and favourable biological nature of fever should be communicated to parents,43 both before the child gets sick and when the child is sick. Furthermore, specific information regarding alternating between fever-reducing medications should be conveyed to parents in user-friendly and accessible language. It is clear, therefore, that in order to provide information which may decrease pressure on GPs to examine children with benign fever, information resources need to be designed, produced and made available to parents, which concurs with existing research.14 Providing parents with evidence-based information in a form which is accessible, understandable and concise should increase awareness and thus decrease overuse of antipyretics where administration disagrees with guidelines. It may alleviate unnecessary presentations at healthcare facilities for assessment and treatment. Tackling the issue of inappropriate detection and management of fever does not have a single solution but requires a suite of initiatives similar to those used to increase awareness regarding antibiotic prescribing.42 44 Information and media campaigns have proven to effectively reduce patient desire for antibiotics where there is insignificant need.42 Furthermore, advertising, marketing and sponsorship of antipyretics should be reviewed by governments in line with standards for advertising of prescription medication. The media have a large role to play in communicating with parents and patients in general. Perhaps the media could play a role in communicating an effective message to parents of children regarding management of fever and febrile illness.

Future work should investigate the feasibility of an intervention to assist parents to manage fever and febrile illness in their children effectively. Empowering parents to take responsibility for effective care of their children should be a key public health issue. Furthermore, the knowledge and beliefs of healthcare professionals should be investigated to understand if parents’ misinformation, attitudes and beliefs are as a result of healthcare professionals’ misinformation, beliefs or outdated information on the topic.

The large sample size is one of the major strengths of this study. Furthermore, beliefs and opinions were captured in a non-clinical setting. This may portray more realistic attitudes and concerns than those captured at the point of care or in acute care settings as the influence of stressful situations may be eliminated. A limitation of the study is that we cannot estimate response rate from the web-based study. A further limitation is the low response rate from the school-based study. The most prominent issue with cross-sectional studies is responder bias as non-participation in questionnaire-based studies is rarely random.45 However, we do not believe this has altered the findings of this study as they are reasonably comparable with existing international studies. This study included a large proportion of highly educated parents, which may not be representative of the general population. Similarly, the included sample did not reflect diverse ethnic backgrounds. This would reduce the external validity as results may not be generalisable to the entire population. When interpreting these results, the reader needs to consider the demographics of the included population. We minimised the effect of response bias associated with internet users by incorporating a paper-based element to the questionnaire. However, the response rate from the paper-based questionnaire was low (42%). We tested for associations between the source of information (school-based vs web-based), finding no evidence of differential responses. Additionally, it is likely that there is a high percentage of internet users among the target population (parents of young children), therefore any response bias with regard to use of the internet is minimal. In the models we have reported, we measured parental experience by the total number of years they had been parents (ie, the age of their oldest child). We estimated similar models where total number of children or total child-years of parenting were used to reflect experience, but there were no appreciable differences in the conclusions drawn from these models and those we have reported here.

Conclusion

Lack of knowledge and presence of conflicting information regarding fever and febrile illness continues to be one of the most prevalent public health issues encountered by parents of young children. Despite increased efforts by guideline writers and national organisations, evidence-based fever management practices continue to be misunderstood or misinterpreted by a section of the population. These levels of misinformation and inappropriate management remain a primary concern to those attempting to improve child health and well-being and decrease unnecessary burden on healthcare services. The current research provides public policy makers with an up-to-date snapshot of current knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of parents concerning fever and febrile illness in children 5 years of age and younger. As nations aim to decrease pressure on healthcare services, a spotlight on parental concerns showcases the need for initiatives and interventions to empower parents to take informed responsibility for the care and management of their child when they have a fever or febrile illness.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the parents who contributed to this research.

Footnotes

Contributors: MK: conceptualised and designed the study, adjusted the questionnaire to reflect custom and practice in Ireland, applied for ethical approval, recruited parents, input data into Excel, performed statistical analysis, compiled the results, reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. LJS: conceptualised and designed the study, assisted with adjustment of the questionnaire to reflect custom and practice in Ireland, reviewed, revised and approved the final manuscript, and submitted the manuscript. FS: conceptualised and designed the study, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. RO’S: conceptualised and designed the study and approved the final manuscript as submitted. EGdB: designed and validated the original questionnaire, approved adjustments to reflect custom and practice in Ireland, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. AMG: assisted with statistical analysis, reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. RH: assisted with data entry and approved the final manuscript as submitted. DD: designed and performed logistic regression modelling, reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. SMC: conceptualised and designed the study, assisted with adjustment of the questionnaire to reflect custom and practice in Ireland, assisted with statistical interpretations, reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. The HRB Clinical Research Facility Cork support publication costs associated with this study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Ethics approval: Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Cork Teaching Hospitals (reference ECM 4 (y)).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: A full data set of results is available from the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Purssell E, Collin J. Fever phobia: The impact of time and mortality--a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2016;56:81–9. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eldalo A. Saudi parent′s attitude and practice about self-medicating their children. Arch Pharm Pract 2013;4:57–62. 10.4103/2045-080X.112985 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Teagle AR, Powell CV. Is fever phobia driving inappropriate use of antipyretics? Arch Dis Child 2014;99:701–2. 10.1136/archdischild-2013-305853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Feverish illness in children: Assessment and initial management in children younger than 5 years National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence - Clinical Guidelines, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crocetti M, Moghbeli N, Serwint J. Fever phobia revisited: have parental misconceptions about fever changed in 20 years? Pediatrics 2001;107:1241–6. 10.1542/peds.107.6.1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fields E, Chard J, Murphy MS, et al. Assessment and initial management of feverish illness in children younger than 5 years: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ 2013;346:f2866. 10.1136/bmj.f2866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Bont EG, Francis NA, Dinant GJ, et al. Parents' knowledge, attitudes, and practice in childhood fever: an internet-based survey. Br J Gen Pract 2014;64:e10–e16. 10.3399/bjgp14X676401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. International Classification of Diseases. ICD-10-CM Diagnosis Code R50.9 2016. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en#/R50.9 (Last accessed 28/10/16).

- 9. de Bont EG, Brand PL, Dinant GJ, et al. [Risks and benefits of Paracetamol in children with fever]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2014;158:A6636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Patricia C. Evidence-based management of childhood fever: what pediatric nurses need to know. J Pediatr Nurs 2014;29:372–5. 10.1016/j.pedn.2014.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jensen JF, Tønnesen LL, Söderström M, et al. Paracetamol for feverish children: parental motives and experiences. Scand J Prim Health Care 2010;28:115–20. 10.3109/02813432.2010.487346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Walsh A, Edwards H, Fraser J. Over-the-counter medication use for childhood fever: a cross-sectional study of Australian parents. J Paediatr Child Health 2007;43:601–6. 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01161.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kelly M, McCarthy S, O'Sullivan R, et al. Drivers for inappropriate fever management in children: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pharm 2016;38:761–70. 10.1007/s11096-016-0333-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kelly M, Sahm LJ, Shiely F, et al. Parental knowledge, attitudes and beliefs regarding fever in children: an interview study. BMC Public Health 2016;16:540 10.1186/s12889-016-3224-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cinar ND, Altun I, Altınkaynak S, et al. Turkish parents' management of childhood fever: a cross-sectional survey using the PFMS-TR. Australas Emerg Nurs J 2014;17:3–10. 10.1016/j.aenj.2013.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kelly L, Morin K, Young D. Improving caretakers' knowledge of fever management in preschool children: is it possible? J Pediatr Health Care 1996;10:167–73. 10.1016/S0891-5245(96)90040-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lagerløv P, Loeb M, Slettevoll J, et al. Severity of illness and the use of paracetamol in febrile preschool children; a case simulation study of parents' assessments. Fam Pract 2006;23:618–23. 10.1093/fampra/cml046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Maguire S, Ranmal R, Komulainen S, et al. Which urgent care services do febrile children use and why? Arch Dis Child 2011;96:810–6. 10.1136/adc.2010.210096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nijman RG, Oostenbrink R, Dons EM, et al. Parental fever attitude and management: influence of parental ethnicity and child's age. Pediatr Emerg Care 2010;26:339–42. 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181db1dce [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sakai R, Niijima S, Marui E. Parental knowledge and perceptions of fever in children and fever management practices: differences between parents of children with and without a history of febrile seizures. Pediatr Emerg Care 2009;25:231–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tessler H, Gorodischer R, Press J, et al. Unrealistic concerns about fever in children: the influence of cultural-ethnic and sociodemographic factors. Isr Med Assoc J 2008;10:346–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. van Stuijvenberg M, de Vos S, Tjiang GC, et al. Parents' fear regarding fever and febrile seizures. Acta Paediatr 1999;88:618–22. 10.1080/08035259950169260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Walsh A, Edwards H, Fraser J. Parents' childhood fever management: community survey and instrument development. J Adv Nurs 2008;63:376–88. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04721.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huang Y, Gu J, Zhang M, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice of antibiotics: a questionnaire study among 2500 Chinese students. BMC Med Educ 2013;13:163. 10.1186/1472-6920-13-163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cals JW, Boumans D, Lardinois RJ, et al. Public beliefs on antibiotics and respiratory tract infections: an internet-based questionnaire study. Br J Gen Pract 2007;57:942–7. 10.3399/096016407782605027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Godycki-Cwirko M, Cals JW, Francis N, et al. Public beliefs on antibiotics and symptoms of respiratory tract infections among rural and urban population in Poland: a questionnaire study. PLoS One 2014;9:e109248 10.1371/journal.pone.0109248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2016. https://www.R-project.org/ (Last accessed 15/11/16). [Google Scholar]

- 28. Department of Health. Minister Reilly announces free GP care for children aged 5 and under as part of Budget 2014. Progress made in achieving more for less but 2014 will be a challenging year for the health services (press release). Dublin, Ireland: Department of Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kramer MS, Naimark L, Leduc DG. Parental fever phobia and its correlates. Pediatrics 1985;75:1110–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Taveras EM, Durousseau S, Flores G. Parents' beliefs and practices regarding childhood fever: a study of a multiethnic and socioeconomically diverse sample of parents. Pediatr Emerg Care 2004;20:579–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cohee LM, Crocetti MT, Serwint JR, et al. Ethnic differences in parental perceptions and management of childhood fever. Clin Pediatr 2010;49:221–7. 10.1177/0009922809336209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Al-Eissa YA, Al-Sanie AM, Al-Alola SA, et al. Parental perceptions of fever in children. Ann Saudi Med 2000;20:202–5. 10.5144/0256-4947.2000.202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bertille N, Fournier-Charrière E, Pons G, et al. Managing fever in children: a national survey of parents' knowledge and practices in France. PLoS One 2013;8:e83469 10.1371/journal.pone.0083469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sahm LJ, Kelly M, McCarthy S, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of parents regarding fever in children: a Danish interview study. Acta Paediatr 2016;105:69–73. 10.1111/apa.13152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kickbusch IS. Health literacy: addressing the health and education divide. Health Promot Int 2001;16:289–97. 10.1093/heapro/16.3.289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zyoud SH, Al-Jabi SW, Sweileh WM, et al. Beliefs and practices regarding childhood fever among parents: a cross-sectional study from Palestine. BMC Pediatr 2013;13:66. 10.1186/1471-2431-13-66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Erkek N, Senel S, Sahin M, et al. Parents' perspectives to childhood fever: comparison of culturally diverse populations. J Paediatr Child Health 2010;46:583–7. 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01795.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chang LC, Liu CC, Huang MC. Parental knowledge, concerns, and management of childhood fever in Taiwan. J Nurs Res 2013;21:252–60. 10.1097/jnr.0000000000000007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Athamneh L, El-Mughrabi M, Athamneh M, et al. Parents' Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of Childhood fever management in Jordan: a Cross-Sectional Study. J Appl Res Child 2014;5. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chiappini E, Parretti A, Becherucci P, et al. Parental and medical knowledge and management of fever in Italian pre-school children. BMC Pediatr 2012;12:97. 10.1186/1471-2431-12-97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hewson P. Paracetamol: overused in childhood fever.. Australian Prescriber 2000;23. [Google Scholar]

- 42. McNulty CA, Cookson BD, Lewis MA. Education of healthcare professionals and the public. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012;67(suppl 1):i11–i18. 10.1093/jac/dks199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mistry N, Hudak A. Combined and alternating acetaminophen and ibuprofen therapy for febrile children. Paediatr Child Health 2014;19:531–2. 10.1093/pch/19.10.531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Arnold SR, Straus SE. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices in ambulatory care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;4:Cd003539. 10.1002/14651858.CD003539.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Levin KA. Study design III: Cross-sectional studies. Evid Based Dent 2006;7:24–5. 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015684supp001.pdf (93.8KB, pdf)