Abstract

Objective

To compare trends in readmission rates among safety net and non-safety net hospitals under the US Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP).

Design

A retrospective time series analysis using Medicare administrative claims data from January 2008 to June 2015.

Setting

We examined 3254 US hospitals eligible for penalties under the HRRP, categorised as safety net or non-safety net hospitals based on the hospital’s proportion of patients with low socioeconomic status.

Participants

Admissions for Medicare fee-for-service patients, age ≥65 years, discharged alive, who had a valid five-digit zip code and did not have a principal discharge diagnosis of cancer or psychiatric illness were included, for a total of 52 516 213 index admissions.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Mean hospital-level, all-condition, 30-day risk-adjusted standardised unplanned readmission rate, measured quarterly, along with quarterly rate of change, and an interrupted time series examining: April–June 2010, after HRRP was passed, and October–December 2012, after HRRP penalties were implemented.

Results

58.0% (SD 15.3) of safety net hospitals and 17.1% (SD 10.4) of non-safety net hospitals’ patients were in the lowest quartile of socioeconomic status. The mean safety net hospital standardised readmission rate declined from 17.0% (SD 3.7) to 13.6% (SD 3.6), whereas the mean non-safety net hospital declined from 15.4% (SD 3.0) to 12.7% (SD 2.5). The absolute difference in rates between safety net and non-safety net hospitals declined from 1.6% (95% CI 1.3 to 1.9) to 0.9% (0.7 to 1.2). The quarterly decline in standardised readmission rates was 0.03 percentage points (95% CI 0.03 to 0.02, p<0.001) greater among safety net hospitals over the entire study period, and no differential change among safety net and non-safety net hospitals was found after either HRRP was passed or penalties enacted.

Conclusions

Since HRRP was passed and penalties implemented, readmission rates for safety net hospitals have decreased more rapidly than those for non-safety net hospitals.

Keywords: Quality in health care, Health policy, GENERAL MEDICINE (see Internal Medicine)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Time series study with over 7 years of data, with outcome measured quarterly.

Trend analyses and comparative interrupted time series adjust for hospital baseline readmission rate in 2008.

Two different definitions of safety net hospital tested.

Our analysis only examines the outcome of readmission rates and does not examine other important outcomes such as observation stays, emergency department visits, patient-reported outcomes or mortality.

Introduction

As part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in April 2010, the US Congress passed the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP).1 Under HRRP, starting in October 2012, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) began financially penalising hospitals that perform worse than the national average on risk standardised readmission rates for Medicare patients.1 To reduce readmission rates, hospitals are implementing programmes to improve transitions in care and engage community services.2 3 This has been accompanied by a significant decline in readmission rates nationally.4–6

Despite these promising results, concerns have been voiced that HRRP would have the unintended consequence of worsening outcomes for the socially disadvantaged patients served by safety net hospitals.7–11 There are two potential mechanisms by which HRRP may disadvantage safety net hospitals, adversely affecting the rate of improvement in readmission rates. First, safety net hospitals which care for a larger proportion of patients with low socioeconomic status (SES), may find it challenging or costly to address underlying socioeconomic reasons for readmissions, such as homelessness, lack of social support or medication non-compliance.2 10 12 13 Second, because of their higher readmission rates,4 14 safety net hospitals have been more likely both to be penalised and to face slightly higher financial penalties under HRRP.7–9 15 16 These increased penalties may reduce resources to already financially strained institutions, inhibiting their ability to invest in effective transitions of care programmes, leading to less improvement in readmission rates. While a recent study found that safety net hospitals experienced larger declines in readmission rates for specific conditions when compared with non-safety net hospitals between 2013 and 2016, it also found that compared with other hospitals with similarly elevated readmission rates at baseline, safety net hospitals did no better.17 However, this study did not adjust for baseline readmission rates in their analysis or examine the trends in the context of HRRP being passed in April 2010, which is the time of greatest decline in readmission rates.6 It also did not determine whether these trends were affected specifically at the time that penalties were implemented as part of HRRP.

Therefore, given concerns for HRRP’s potential effect on safety net hospitals’ abilities to improve patient outcomes due to both the patients they treat and the financial penalties they face, we examined whether overall trends in 30-day, all-condition risk-standardised readmission rates at safety net and non-safety net hospitals have declined at similar rates from 2008 through 2015, taking into account their starting readmission rates. We also examined the quarter immediately after HRRP was passed as part of the ACA on 23 March 2010 and the quarter after the penalties were implemented on 1 October 2012 to see if readmission rate trends changed differentially among safety net and non-safety net hospitals.

Methods

Overview

This was an observational study in which we linked over 7 years of Medicare claims to census data for included patients and American Hospital Association (AHA) information on hospitals. We used census data to classify patients as low SES using a composite of neighbourhood level indicators and then classified hospitals as ‘safety net’ according to whether they admitted disproportionally higher numbers of patients with low SES. We then used claims data to construct standardised readmission rates (SRRs) for each hospital in each calendar quarter of the study period. We used time series models to examine whether quarterly SRRs for safety net hospitals had different trends over time when compared with non-safety net hospitals, adjusting for baseline readmission rates in 2008. We then performed a comparative interrupted time series (ITS) analysis, examining the effect of HRRP on safety net hospitals compared with non-safety net hospitals at two different time points: the quarter including April–June 2010 and in the quarter including October–December 2012. In secondary analyses, we defined safety net hospitals based on proportion of Medicaid admissions.

Data sources

Data were obtained from Medicare’s administrative claims database from January 2008 through June 2015. This dataset includes hospitalisation data for fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare beneficiaries, including index admissions, readmissions and in-hospital comorbidity data from the CMS Inpatient Standard Analytic File. This dataset also includes enrolment, demographic and postdischarge mortality status from the Medicare Enrollment Database. We linked all patients to block level census data from the 2009 to 2013 American Community Survey based on their nine-digit zip codes. The American Community Survey is an ongoing statistical survey by the US Census Bureau.18 To obtain hospital characteristics and Medicaid caseload, we linked each hospital to the 2008 AHA survey data using its Medicare Provider ID. Study was approved by Yale’s IRB, Human Investigation Committee . Identifiable data used for this study were obtained through a data use agreement with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Study sample

Our study sample was constructed to be consistent with the National Quality Forum endorsed Hospital-Wide (All-Condition) Risk-Standardised Readmission Rate measure (referred to as hospital-wide readmission measure) which CMS has been using since 2013 to publicly report each hospital’s readmission rate for Medicare beneficiaries.19 We included Medicare FFS beneficiaries aged ≥65 years, enrolled in Medicare Part A for at least 12 consecutive months, discharged alive from any non-cancer acute care hospital from January 2008 to June 2015. We included multiple index admissions per patient over the study period, excluding only admissions in which the primary diagnoses were psychiatric or cancer. In cases of transfers, as in the hospital-wide readmission measure, readmissions are attributed to the hospital that ultimately discharged the patient to a non-acute care setting. Additional inclusion and exclusion criteria were consistent with the publicly reported hospital-wide readmission measure.19 In addition, we excluded those discharges for patients with invalid five-digit zip codes as we were unable to link them to the census data. We also excluded admissions to hospitals that were ineligible for HRRP. To ensure stable baseline rates for each hospital, we excluded hospitals that had fewer than 100 discharges in the base year 2008. To ensure stability of estimates, for each quarter we excluded hospitals that had fewer than 25 discharges during that quarter.

Safety net hospital definition

There are multiple definitions of safety net hospitals, which can identify different, non-overlapping hospitals, with no consensus on the best definition.20 Due to this, we chose to use one primary definition, and in a secondary analysis use a different definition, based on a different data source.

We identified safety net hospitals based on the proportion of patients that had low SES in the baseline year of 2008. For our primary analysis, patient’s SES was defined based on the validated Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) SES index, adjusted for cost of living.21 This index uses the following census data variables to create an index from 0% to 100%: unemployment, percent below US poverty line, median income, median value of owner occupied homes, percent with less than high school education, percent with at least 4 years college and percent of homes with crowding. We adjusted the variables median income and median value of owner occupied homes using the Bureau of Economic Analysis’s Regional Price Parity adjustment22 from 2008 to account for regional cost of living differences. We defined patients with low SES as those who live in a zip code with a SES index score in the lowest quartile of all zip codes.

We then calculated the proportion of patients with low SES among all patients admitted to each hospital for the base year of 2008. We defined safety net hospitals as those hospitals in the quartile serving the largest proportion of patients with low SES.

As a secondary analysis, we used a definition employed in previous research, defining safety net hospitals as any public hospital or any private hospital with an annual Medicaid caseload that is greater than 1 SD above the mean of its respective state’s private hospital Medicaid caseload.23

Outcome

We identified all unplanned readmissions within 30 days of hospitalisation using previously described algorithms.19 We calculated a SRR for each hospital for each quarter. As with the hospital-wide readmission measure, in order to adjust for case-mix and service-mix at each hospital, we calculated SRRs obtained from five models for each of five distinct cohorts (cardiorespiratory, cardiovascular, neurology, surgery and medicine). Each of the five logistic regression models adjusted for age, sex, the admission diagnosis grouped by AHRQ Clinical Classification Software, and clinical comorbidities grouped by modified CMS-Condition Category. Unlike the hospital-wide readmission measure, each model was estimated using general estimating equations rather than random-effects models to account for clustering by hospital. We used all years of data to create each of the five cohort models. The beta coefficients from each of the five models were then used to calculate an expected probability of readmission for each discharge, and these, along with the observed number of readmissions, summarised over hospitals and quarters to calculate an observed over expected readmission rate for each of 5 the cohorts for each hospital for each quarter. We took the weighted arithmetic mean of the five cohorts for each hospital and each quarter, weighted by quarterly cohort volume, and multiplied this by the overall unadjusted readmission rate to obtain an SRR for each hospital for each quarter.

Statistical analyses

We describe hospital characteristics including hospital size, urban/rural status, hospital ownership, hospital regional location and teaching status for all included hospitals by safety net status. We tested for differences between safety net and non-safety net hospital characteristics using Χ2 tests. We also summarised SRR by safety net status, and plotted mean SRR by quarter for each hospital type. Then, we estimated a mixed-effects linear regression model to assess whether safety net and non-safety net hospitals had different trends over time for the entire study period. We used the SRR as the dependent variable and included elapsed calendar quarter as a linear independent variable, safety net status as an indicator variable, the interaction of safety net status with calendar quarter and to account for the potential bias that hospitals starting at a higher readmission rate may decline more rapidly, we added the baseline 2008 SRR to adjust for the starting readmission rates; each model also included hospital as a random effect to account for correlation of quarterly rates within hospital. By testing if the interaction of safety net status and time was significant, we were able to use this model to assess whether safety net hospitals had different overall trends than non-safety net hospitals. As a sensitivity analysis, to assess whether hospital characteristics other than safety net status might account for any differences in readmission trends by safety net status, we replicated this model including hospital characteristics. We then performed a comparative ITS analysis, comparing the change in SRR for safety net hospitals compared with non-safety net hospitals at two distinct time points: (1) quarter 2, 2010, which is when directly HRRP was passed and (2) quarter 4, 2012, which is the first 3 months of HRRP’s penalties. We then repeated all analyses using the secondary definition of safety net status.

Statistical analysis was done using SAS software system (SAS V.9.3) and Stata (Stata V.14.1).

Results

Cohort

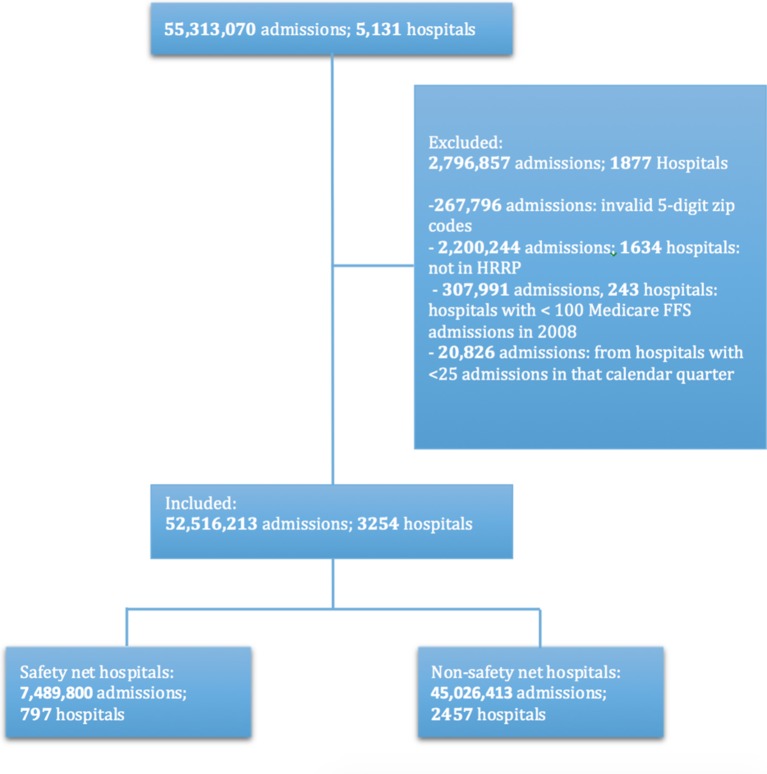

The initial sample included 55 313 070 index admissions at 5131 hospitals from January 2008 to June 2015, eligible for the hospital-wide readmission measure.19 After exclusions (see figure 1), our final cohort comprised 52 516 213 admissions at 3254 hospitals.

Figure 1.

Cohort development of safety net and non-safety net hospitals. FFS, fee-for-service, HRRP, Hospital Readmission Reduction Program.

Hospital characteristics

Among the 25% of hospitals defined as safety net hospitals using the AHRQ SES index, the mean percent of patients with low SES served at safety net hospitals was 58.0% (15.3), whereas the mean percent was 17.1% (10.4) at non-safety net hospitals.

Safety net hospitals were more likely to serve a higher proportion of Medicaid patients, more likely to be small (<100 beds), to be rural, to be either public or for-profit, to be located in the south, and to be non-teaching hospitals compared with non-safety net hospitals (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline hospital characteristics for safety net and non-safety net hospitals

| Non-safety net* | Safety net* | p Value† | ||

| N | 2457 (100.0) | 797 (100.0) | ||

| % Medicaid patients | ≤5% | 152 (6.2) | 37 (4.6) | <0.001 |

| 6%–10% | 304 (12.4) | 45 (5.6) | ||

| 11%–15% | 448 (18.2) | 90 (11.3) | ||

| 16%–20% | 672 (27.4) | 162 (20.3) | ||

| 21%–30% | 679 (27.6) | 258 (32.4) | ||

| >30% | 152 (6.2) | 183 (23.0) | ||

| Missing | 50 (2.0) | 22 (2.8) | ||

| Beds | 6–24 | 63 (2.6) | 29 (3.6) | <0.001 |

| 25–49 | 214 (8.7) | 128 (16.1) | ||

| 50–99 | 383 (15.6) | 149 (18.7) | ||

| 100–199 | 662 (26.9) | 235 (29.5) | ||

| 200–299 | 436 (17.7) | 102 (12.8) | ||

| 300–399 | 271 (11.0) | 59 (7.4) | ||

| 400–499 | 155 (6.3) | 29 (3.6) | ||

| 500+ | 223 (9.1) | 44 (5.5) | ||

| Missing | 50 (2.0) | 22 (2.8) | ||

| Teaching status | None | 1500 (61.1) | 589 (73.9) | <0.001 |

| Major teaching | 205 (8.3) | 47 (5.9) | ||

| Minor teaching | 702 (28.6) | 139 (17.4) | ||

| Missing | 50 (2.0) | 22 (2.8) | ||

| Urban status | Rural | 136 (5.5) | 169 (21.2) | <0.001 |

| Urban | 2271 (92.4) | 606 (76.0) | ||

| Missing | 50 (2.0) | 22 (2.8) | ||

| Ownership | Private non-profit | 280 (11.4) | 217 (27.2) | <0.001 |

| Private for profit | 1666 (67.8) | 319 (40.0) | ||

| Public | 461 (18.8) | 239 (30.0) | ||

| Missing | 50 (2.0) | 22 (2.8) | ||

| Region | West | 459 (18.7) | 129 (16.2) | <0.001 |

| Midwest | 654 (26.6) | 69 (8.7) | ||

| Northeast | 463 (18.8) | 32 (4.0) | ||

| South | 830 (33.8) | 502 (63.0) | ||

| Missing | 1 (0.0) | 43 (5.4) | ||

| % Low SES‡ | Mean (SD) | 17.1 (10.4) | 58 (15.3) | <0.001 |

| Range | (0–57.6) | (38.3–100) |

*Reported as number (per cent) except where noted for % low SES.

†χ2 test of independence across safety net hospitals.

‡SES, socioeconomic status.

Standardised readmission rates

We plotted the mean hospital-wide SRRs for each quarter for safety net and non-safety net hospitals (figure 2). The mean SRR for safety net hospitals was 17.0% (SD 3.7) in the first quarter of 2008, decreasing to 13.6% (SD 3.6) by the second quarter of 2015. The mean SRR for non-safety net hospitals was 15.4% (SD 3.0) in the first quarter of 2008, decreasing to 12.7% (SD 2.5) by the second quarter of 2015. The absolute difference in the mean SRR between the two types of hospitals was 1.6% (95% CI 1.3 to 1.9) in the first quarter of 2008 and was 0.5% (95% CI 0.7 to 1.2) in the second quarter of 2015, a 43% relative reduction in the gap between safety net hospitals and non-safety net hospitals.

Figure 2.

Quarterly standardized readmission rates for safety net hospitals and non-safety net hospitals from January 2008 through June 2015 defined using hospital’s proportion of patients with low SES. HWR, hospital-wide readmission; SES, socioeconomic status.

Difference in trends

The decline in SRR was significantly greater among safety net hospitals than among non-safety hospitals: 0.03 percentage points per quarter (95% CI 0.03% to 0.02%, p<0.001). This result was unchanged after adjustment for hospital characteristics: 0.03 percentage points per quarter (95% CI 0.03% to 0.03%, p<0.001).

Comparative ITS results

The comparative ITS analyses revealed that for hospitals overall, the SRR declined significantly after the second quarter of 2010 and again after the final quarter of 2012 (absolute change of −0.17 (−0.24 to –0.09) p<0.001 and −0.22 (−0.30 to –0.14) p<0.001, respectively). However, when examining the interaction of the decline at this time and safety net status of the hospital, the decline in SRR for safety net hospitals was not significantly different from the decline in SRR for non-safety net hospitals when comparing their two trends at those times: Q2 2010 (absolute difference of 0.02 (−0.13 to 0.18) p=0.76), or Q4 2012 (absolute difference −0.01 (−0.18 to 0.15), p=0.88).

Secondary analysis with alternative safety net hospital definition

In our secondary analyses defining safety net status using Medicaid caseload we plotted the SRR by safety net status (figure 3). We found that the absolute difference in the mean SRR between safety net and non-safety net hospitals decreased from 0.56% (95% CI 0.29 to 0.83) in the first quarter of 2008 to 0.11% (95% CI −0.12 to 0.36) in the second quarter of 2015, a 80% relative reduction in the gap between the two types of hospitals. In our linear time series analysis, we similarly found that there was a greater decline in SRR for safety net hospitals compared with non-safety net hospitals, but by a smaller amount: 0.01 percentage points per quarter (95% CI 0.02 to 0.01, p<0.001). This again held true after adjusting for hospital characteristics: 0.01 percentage points per quarter (95% CI 0.02 to 0.01, p<0.001)

Figure 3.

Quarterly standardised readmission rates for safety net hospitals and non-safety net hospitals from January 2008 through June 2015 defined using Medicaid caseload. HWR, hospital-wide readmission.

Similarly, we found that the SRR declined significantly after April 2010 and again after October 2012 among all hospitals. However, using this definition of safety net status, the comparative ITS showed that after HRRP was passed in April 2010, the SRR for safety net hospitals declined more by an absolute value of −0.21 (−0.38 to –0.05; p=0.009). There was no significant difference in decline after HRRP was implemented in October 2012 (absolute difference of −0.05 (−0.22 to 0.12), p=0.56).

Discussion

Our study shows that during the era of HRRP, risk-standardised readmission rates declined more rapidly at safety net hospitals than at non-safety net hospitals after accounting for their baseline readmission rates, by an additional 0.03 percentage points per quarter over the study period 2008–2015, attenuating the gap in performance between safety net and non-safety net hospitals. This more rapid decline was found using two different definitions of safety net hospitals and remained after adjusting for key hospital characteristics. These results indicate that the gap in performance between safety net and non-safety net hospitals has narrowed over the years spanning HRRP’s enactment and implementation.

Because HRRP may have influenced the change in readmission rates differently specifically when it was passed or when penalties were implemented, we used comparative ITS to examine the impact of these two events on the differential drop in readmission rates between the two types of hospitals. Our results showed that while these differences declined steadily over the study period, they did not have a significantly different rate of change associated with either event. This again suggests that the penalties did not inhibit safety net hospitals’ abilities to improve readmission rates compared with non-safety net hospitals.

Our study adds to the results of a recent study by Carey and Lin in several important ways. We show that hospital-wide readmission rates are declining faster for safety net hospitals compared with non-safety net hospital in addition to the condition-specific readmission rates shown by Carey and Lin.17 In addition, our study uses patient-level data to build a single model to obtain the standardised readmission rates each quarter, rather than using the reported standardised readmission results created from different models each year. By using this patient-level model, we were able to examine the trends over time, after adjusting for the baseline readmission rate in the first year, and to show that over the study period, there was indeed a greater drop for safety net hospitals compared with non-safety net hospitals that was not only due to higher baseline readmission rates. We also were able to examine the readmission rate trends and effects over the time periods spanning the passing of HRRP and the implementation of the penalties, showing a steady decline over the entire time period, without specific drops when HRRP was passed or penalties were implemented.

There are several possible reasons why the difference in readmission rates between safety net hospitals and non-safety net hospitals narrowed steadily over our study period. First, safety net hospitals may care for a larger proportion of patients whose readmissions could be avoided by quality improvement and care transitions programmes that have been shown to be effective, such as improving discharge instructions and ensuring closer outpatient follow-up.24–27 Second, safety net hospitals may have had better connections to their communities and the primary care networks that serve their patients, improving their ability to implement coordinated programmes to reduce readmissions. Lastly, the administrators at safety net hospitals, knowing they had higher readmission rates and would face more penalties, may have been more likely to focus on or invest more in improving their readmission rates.

Though these early results are promising, they should be viewed with caution. Patients discharged from safety net hospitals are still more likely to be readmitted within 30 days than those discharged from non-safety net hospitals, although the difference is now less than one percentage point. Additionally, this study does not assess unintended consequences of readmission reduction efforts, such as inappropriately diverting patients to emergency or observation care. A recent study by Zuckerman et al found no correlation between change in readmission rate and change in observation-service use, but studies have not been done specifically in the safety net hospital population.6 Another potential unintended consequence would be diversion of resources from other important quality and safety initiatives to readmission efforts. There is evidence that mortality has not increased with the nationally declining readmission rate overall,4 but we do not know if there has been a differential effect in safety net hospitals compared with non-safety net hospitals. We also do not know if a potentially disproportionate amount of resources to reducing readmission rates are being spent at safety net hospitals, which could potentially threaten financial margins with downstream effects such as closures or not having funds to invest in other initiatives.

Our study has several additional limitations. First, for our primary analysis, the definition of safety net hospitals uses a neighbourhood indicator—the AHRQ SES index—to identify patients with low SES, and is not a direct measure of patients’ income, wealth, education or other measures of SES. This index, however, is validated for Medicare patients and importantly comprised multiple SES characteristics not otherwise available in administrative data.21 In addition using this definition, more safety net hospitals are identified that are small, rural and located in the South, due to the concentration of poverty in this part of the country. To address this limitation, we also performed a secondary analysis using Medicaid status as a marker of low SES, which is a patient-specific marker. We identified hospitals with significantly higher Medicaid caseloads within each state, mitigating the likelihood that one region of the country would be over-represented. Results were similar and our results are also similar to those of a recent study which showed narrowing of disparities in readmissions for safety net hospitals using a definition based on the patients with Supplemental Security Income.17 Another limitation specific to the ITS at the 2010 time point is that the passing of HRRP occurred simultaneously with the recovery audit contractor programme, under which short stay payments were rescinded. It is possible that this programme affected payments to safety net versus non-safety net hospitals differently. However, it is known that readmissions would be less likely to be affected by this policy, as those stays are more likely to be longer. Additionally, this would not affect the overall results of narrowing disparities, only the potentially causal effect at the time point of 2010. Finally, our study only examines disparities in readmission rates between safety net hospitals compared with non-safety net hospitals. It is possible that HRRP has had different effects on outcomes within hospitals.

This study does not directly answer the currently debated policy question of whether the readmission measure should be risk-adjusted for SES. However, a central argument for SES risk-adjustment is that without adjustment, safety net institutions will be unfairly penalised and that patients served at these institutions may suffer. This study demonstrates that caring for socially disadvantaged patients does not interfere with a hospital’s ability to reduce the risk of readmission. In fact, those hospitals serving the largest proportion of patients with low SES have been more successful at reducing readmissions than non-safety net hospitals. Readmission rate, however, is only one outcome and further studies will be needed to assess HRRP’s effect on further patient-centric outcomes of mortality, patient satisfaction, emergency department visits and observation stays as well as its effect on potential hospital closures that would limit care.

Conclusion

We found that while safety net hospitals had higher readmission rates than non-safety net hospitals at baseline, their readmission rates have declined more rapidly since HRRP, reducing the disparity gap in readmission rates for patients treated at safety net hospitals. Our study suggests that HRRP has been effective at improving readmission rates for all patients and decreasing disparities for patients served at safety net hospitals.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All those who contributed significantly to this work are listed as authors and meet all criteria for authorship. All who meet criteria for authorship are listed as authors. Specifically, AMS, LIH, JYK, JH, JNG, ZL, JSR and SMB contributed substantially to the conception and design of the work and the interpretation of data for the work; JYK and JH also contributed substantially to the analysis of the data for the work. AS drafted the work and all authors revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approve of the final version of the work and are in agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This work was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (R01HS022882). The AHRQ had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the AHRQ.

Competing interests: AMS, LIH, JYK, JH, JNG, ZL, JSR and SMB receive funding from the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services to construct quality measures, including the hospital-wide readmission measure. JSR also reports receiving research support through Yale University from Medtronic and Johnson and Johnson to develop methods of clinical trial data sharing, from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to develop methods for post-market surveillance of medical devices, and from the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association (BCBSA) to better understand medical technology evidence generation.

Ethics approval: Yale HIC.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data from this study were obtained through a data use agreement with the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the American Hospital Association, as well as using data from the 5-year American Community Survey census data.

References

- 1. Hospital Readmission Reduction Program. Patient protection and Affordable Care Act S 2025. (23 Mar 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 2. Joynt KE, Sarma N, Epstein AM, et al. Challenges in reducing readmissions: lessons from leadership and frontline personnel at eight minority-serving hospitals. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2014;40:435–AP7. 10.1016/S1553-7250(14)40056-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bradley EH, Curry L, Horwitz LI, et al. Contemporary evidence about hospital strategies for reducing 30-day readmissions: a national study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:607–14. 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.03.067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Medicare Hospital Quality Chartbook: Performance Report on Outcome Measures September 2014: Prepared by Yale New Haven Health Services Corporation Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2014.

- 5. Gerhardt G, Yemane A, Hickman P, et al. Medicare readmission rates showed meaningful decline in 2012. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev 2013;3:E1–E12. 10.5600/mmrr.003.02.b01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zuckerman RB, Sheingold SH, Orav EJ, et al. Readmissions, observation, and the hospital readmissions reduction program. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1543–51. 10.1056/NEJMsa1513024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boccuti GC C. Aiming for fewer hospital U-turns. the Medicare Hospital Readmission Reduction Program The Henry Kaiser Family Foundation Issue Brief. http://kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/aiming-for-fewer-hospital-u-turns-the-medicare-hospital-readmission-reduction-program/ (29 Jan 2015).

- 8. Gilman M, Adams EK, Hockenberry JM, et al. California safety-net hospitals likely to be penalized by ACA value, readmission, and meaningful-use programs. Health Aff 2014;33:1314–22. 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Joynt KE, Jha AK. Characteristics of hospitals receiving penalties under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. JAMA 2013;309:342–3. 10.1001/jama.2012.94856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barnett ML, Hsu J, McWilliams JM. Patient characteristics and differences in hospital readmission rates. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1803. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gu Q, Koenig L, Faerberg J, et al. The medicare hospital readmissions reduction program: potential unintended consequences for hospitals serving vulnerable populations. Health Serv Res 2014;49:818–37. 10.1111/1475-6773.12150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Calvillo-King L, Arnold D, Eubank KJ, et al. Impact of social factors on risk of readmission or mortality in pneumonia and heart failure: systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:269–82. 10.1007/s11606-012-2235-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Herrin J, St Andre J, Kenward K, et al. Community factors and hospital readmission rates. Health Serv Res 2015;50:20–39. 10.1111/1475-6773.12177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ross JS, Bernheim SM, Lin Z, et al. Based on key measures, care quality for Medicare enrollees at safety-net and non-safety-net hospitals was almost equal. Health Aff 2012;31:1739–48. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gilman M, Hockenberry JM, Adams EK, et al. The financial effect of value-based purchasing and the hospital readmissions reduction program on safety-net hospitals in 2014: a Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:427–36. 10.7326/M14-2813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sheingold SH, Zuckerman R, Shartzer A. Understanding medicare hospital readmission rates and differing penalties between safety-Net and other hospitals. Health Aff 2016;35:124–31. 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carey K, Lin MY. Hospital readmissions reduction program: safety-net hospitals show improvement, modifications to penalty formula still needed. Health Aff 2016;35:1918–23. 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. American Community Survey Information Guide. commerce USDo. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Evaluation YNHHSCCfORa. 2015 Measure Updates and Specification Report Hospital-Wide All-Cause Unplanned Readmission Measure - Version 4.0. (Mar 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peter Cunningham LF. Environmental Scan to Identify the Major Research Questions and Metrics for Monitoring the Effects of the Affordable Care Act on Safety Net Hospitals : Center for Studying Health System Change. ASPE, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality R, MD Creation of New Race-Ethnicity Codes and Socioeconomic Status (SES) Indicators for Medicare Beneficiaries. 2014. http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/final-reports/medicareindicators/index.html.

- 22. Bureau of Economic Analysis UDoC News Release: Real Personal Income for States and Metropolitan Areas. 2016. http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/regional/rpp/2016/pdf/rpp0716.pdf.

- 23. Gaskin DJ, Hadley J, Freeman VG. Are urban safety-net hospitals losing low-risk medicaid maternity patients? Health Serv Res 2001;36(1 Pt 1):25–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jenq GY, Doyle MM, Belton BM, et al. Quasi-experimental evaluation of the effectiveness of a large-scale readmission reduction program. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:681. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, et al. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1822–8. 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:178–87. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 1999;281:613–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.