Abstract

Introduction

Low vision and blindness adversely affect education and independence of children and young people. New ‘assistive’ technologies such as tablet computers can display text in enlarged font, read text out to the user, allow speech input and conversion into typed text, offer document and spreadsheet processing and give access to wide sources of information such as the internet. Research on these devices in low vision has been limited to case series.

Methods and analysis

We will carry out a pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT) to assess the feasibility of a full RCT of assistive technologies for children/young people with low vision. We will recruit 40 students age 10–18 years in India and the UK, whom we will randomise 1:1 into two parallel groups. The active intervention will be Apple iPads; the control arm will be the local standard low-vision aid care. Primary outcomes will be acceptance/usage, accessibility of the device and trial feasibility measures (time to recruit children, lost to follow-up). Exploratory outcomes will be validated measures of vision-related quality of life for children/young people as well as validated measures of reading and educational outcomes. In addition, we will carry out semistructured interviews with the participants and their teachers.

Ethics and dissemination

NRES reference 15/NS/0068; dissemination is planned via healthcare and education sector conferences and publications, as well as via patient support organisations.

Trial registration number

NCT02798848; IRAS ID 179658, UCL reference 15/0570.

Keywords: Vision, Low vision, Assistive technology, Adolescent, Child

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Enrolment in different settings, pragmatically exploring feasibility.

Low selection, performance and detection bias.

Small sample size.

Performance and social desirability bias (masking of participants not possible).

Possible differential bias between study arms (attractiveness of active intervention).

Introduction

People are considered to have ‘low vision’ when their corrected visual acuity (VA) is poorer than 6/18 in their better eye, or their visual field is less than 10° from the point of fixation, but they use, or are potentially able to use, vision for the planning and/or execution of a task.1 There is an overlap with the definitions of visual impairment (VI) and severe VI/blindness. Low vision affects almost 3 million children worldwide.2 3 It adversely affects educational and employment opportunities, causing economic hardship in adult life.4 5 Early assessment, provision of low-vision aids (LVAs) and training in their use are essential to improve functional vision (FV) and to allow children to fully participate in education and improve their quality of life (QoL).

In recent years, LVAs have been complemented by ‘assistive technologies’ (AT). These include electronic vision enhancement devices such as closed-circuit television (CCTV), computer screen reading software, digital audio books, periodicals and text which can be accessed via computers, mobile phones and tablet computers. AT may enhance reading and writing skills, as well as communication with the world on an equal basis, thereby improving the QoL of people with low vision and facilitating the learning process.6

Teachers, parents and young people with low-vision report limited use of prescribed LVAs and other AT devices usually for fear of ‘standing out’. Electronic devices can have other limitations including a lack of portability, poor integration with school information technology networks and limitations of either input or output functions.

Tablet computers may help overcome many of these problems as they are portable and capable of running a wide range of software and of accessing wireless networks. More importantly, acceptability by young people may be high. Numerous applications are available, such as screen magnifiers, optical character recognition and text-to-speech conversion. All manufacturers provide ‘accessibility features’. The Apple iPad, recommended by low-vision support charities such as the Royal National Institute for Blind People and the Royal London Society for the Blind, increases reading speed in adults with low vision7 and is used by many people with low vision.8

Tablet computers are of considerably lower cost (around £400–1600 per student) than current standard classroom technology, such as CCTV (which can cost up to £6400 with distance and near camera, per student). Tablet computers offer the additional advantages of direct access to school intranets, social acceptability and word document and spreadsheet processing. Additionally, the price of tablet computers is likely to fall, whereas the price of CCTVs has remained high.

In the UK, support funding for children and young people with VI in local authority-maintained settings has traditionally been administered by their local authority. There is increasingly a shift of funding streams, for example, children with VI may attend educational settings which are not funded or maintained by the local authority, or individual funding may be agreed with the family (self-directed support). Robust information about the performance of different devices is vitally important for educational settings and families and carers.

We have carried out two systematic Cochrane reviews of the paediatric low-vision literature and have found that to date, no clinical trials of AT for young people with low vision have been conducted.9 10 Instead, the literature is limited to small non-randomised case series and cohort studies, mostly of optical devices. Informal discussions with young people with VI, their families and teachers indicate that those who have access to tablet computers such as Apple iPads find their accessibility features very useful, and would support research comparing this AT with conventional LVAs.

Methods and analysis

Our hypothesis is that tablet computer-based AT may have high acceptability and usage by children and young people with low vision, and may improve their FV, vision-related QoL (VRQoL) and access to education. As no preliminary data on trial feasibility are available, we will carry out a pilot study to assess whether or not a definitive trial exploring this issue is feasible.

Primary objective

The principal research question is: ‘Is it feasible to recruit young people with low vision into a randomised controlled trial testing the effect of electronic assistive technologies on reading, educational and quality of life outcome measures?’

Secondary research questions

Is the active intervention (tablet computer) acceptable to young people, their families/carers and their teachers?

Is the active intervention accessible, and do participants use it?

Estimate VRQoL measures, FV measures and reading and educational outcome measures by intervention group at 6 months

Have there been any adverse events (loss of motivation, negative peer comments) about using the AT?

What are the costs associated with the active intervention?

Trial design

This is a parallel 1:1 two-arm pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT); the experimental intervention will be an Apple iPad tablet computer with low-vision applications, and the control intervention will consist of the conventional low-vision support as per standard clinical care, which includes optical LVA and/or CCTV.

Study setting

There will be three recruitment sites, one in India (L V Prasad Eye Institute (LVPEI), Hyderabad, Telangana; Meera and L B Deshpande Centre for Sight Enhancement, a tertiary eye care hospital) and two in the UK—The Child Development Centre in Bedford (a multidisciplinary community health, education and social care facility for children with developmental needs and disabilities) and the low-vision clinic for children and young people at Moorfields Eye Hospital (a tertiary eye care facility in London). The decision to have two very different settings reflects the study funders’ aim to provide people in low-income countries with equal access to innovation, and to shorten the timescale of implementation of novel approaches in low-income settings.

Inclusion criteria

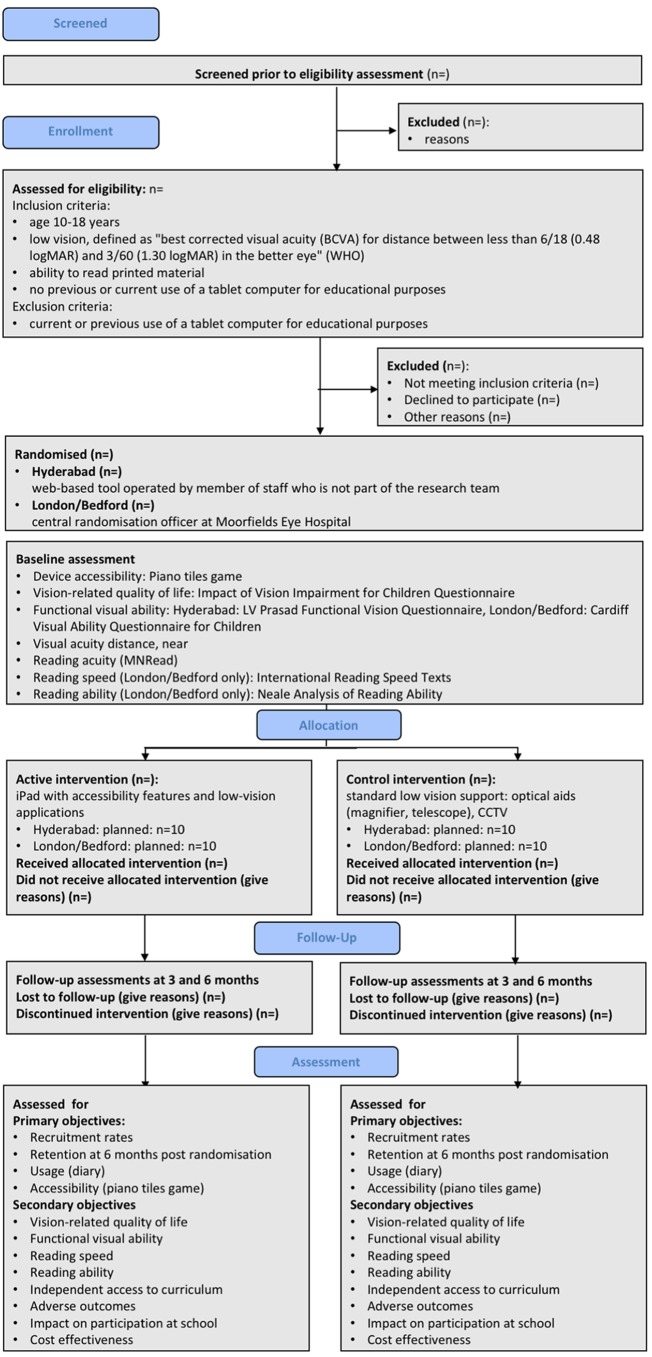

We will include young people aged 10–18 years with low vision, defined as ‘best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) for distance between less than 6/18 (0.48 logMAR) and 3/60 (1.30 logMAR) in the better eye’ (WHO), who are able to read printed material and who are not currently using, and have not previously used, tablet computer for educational purposes (figure 1). We will include students who have access to a tablet computer already but do not use it for educational purposes. We will include students who use a laptop. We will also include students who use or have previously used optical LVAs such as magnifiers, telescopes and CCTV systems.

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing planned participant flow (after Consort extension for pilot and feasibility studies19). CCTV, closed-circuit television.

Exclusion criteria

Young people who are currently using or are prior users of a tablet computer for educational purposes (at school or frequently for homework) will be excluded. We accept that many videos and games children watch on tablet computers can be seen as educational, and that many children will use a tablet computer occasionally for research for homework. We will include young people using a tablet computer in this way.

Should participants in the control group receive a tablet computer from their local VI team or from their educational setting or if they start taking their own tablet computer to school, they will be removed from the trial and no further data collection will take place.

Near VA equivalent to 6/18 (0.48 logMAR) or better will not be an exclusion criterion, as even though students may perform well on a near acuity test, their reading acuity may be less than the near acuity measured in a clinical setting. Furthermore, as functional reading acuity can gradually reduce over the course of the day, there may be an increase in the need for optical magnification towards the end of the day, and when completing homework. Figure 1 summarises the design of the trial; each of the trial aspects is described in detail below.

Interventions

All participants recruited in the India and London site will receive a comprehensive low-vision assessment with an optometrist, including the prescription and supply of optimal refractive correction, tints and optical devices (magnifiers, telescopes), discussion and demonstration of electronic magnifiers, signposting to appropriate services and liaison with teachers for VI and class teachers.

The active intervention will be the use of a tablet computer (Apple iPad) for educational purposes at school and at home. The device will run word processing, spreadsheet and slide presentation files (Microsoft Office for iPad). These will allow students to import documents from the school’s learning environment onto their device, work on them and export them back to the teacher. Users will be given information and instruction on voice-over (text-to-speech), magnification and contrast settings in the iOS software. In addition, we will install the video magnifier, colour identifying and image recognition application ‘ViaOpta Daily’. The UK devices will have WiFi enabled to access school wireless networks. Additionally, those in India will have wireless data (3G) connectivity.

None of these applications is a medical device; they therefore do not require CE marking (confirmed by Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA)). We will activate the device accessibility features and install the applications before participants receive the devices. In London and India, study optometrists will train participants in the use of devices, features and applications. In Bedford, the team for visually impaired pupils will support this training. We envisage an initial training session of 2 hours in the first week, followed by telephone support or follow-up visits to the setting if required. For participants recruited in London, each participant’s teacher for the vision impaired will be informed of their inclusion in this study. Letters will be sent to the class teacher, teacher for the vision impaired and school special education needs coordinator requesting that the young people be allowed to use their device in the classroom.

In India, participants were provided with training in the use of the devices and iPad at the low-vision rehabilitation centre. Additional support was provided over the phone to children who faced some difficulty with using the iPad initially.

The control intervention will consist of the comprehensive low-vision assessment only. Due to differences in the recruitment route at Bedford, participants in the control group at Bedford will not be reassessed but will continue with their current spectacles and low-vision devices and will continue to be monitored by the VI team.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes of this trial relate to feasibility of a full trial. There will be four primary outcomes: (1) recruitment rate over 6 months, (2) retention of participants until 3 months after randomisation, (3) acceptance/usage of the allocated device and (4) accessibility of the active intervention device.

Our recruitment target at both the site in India and the UK sites is 20 participants each over 6 months. We will consider that a definitive trial is feasible if we enrol 90% of this figure (n=18) during this period and/or if 100% are enrolled over 7 months. We will record the number of eligible young people declining to participate and their reasons for not wishing to take part. We will also capture whether any children dropped out of the study and why.

We will measure acceptance/usage of the allocated device using a participant diary; we will summarise usage for the electronic database as ordinal variable: 0=no acceptance, 1=used sometimes, 2=used frequently. We will define success as 80% of participants in the active intervention group using the device ‘frequently’.

Accessibility of the active intervention device will be determined by asking participants to play a touch-based game, ‘Piano Tiles’. In this game, the player has to touch moving black tiles that move down the screen. Following an introduction to the game using the ‘classic’ version, we will assess the young person’s score in the ‘zen’ version over 15 s and record the best score of three attempts. We will convert the game score to an ordinal variable for capture within the pilot database as follows: score 0–15: ordinal variable 0=low accessibility, 16–35: 1=medium accessibility, greater than 35: 2=high accessibility. The protocol authors agreed on using this scoring system based on five children with good and with low vision playing this game; this system is at present not validated, and this pilot trial will allow us to collect data about the range of scores achieved by the population of interest.

Exploratory/secondary outcomes

In addition to the primary outcomes, which will inform a future full RCT, we will collect data on a range of measures of visual function used in healthcare settings. Specifically, we will record functional visual ability, as measured by Cardiff Visual Ability Questionnaire for Children (CVAQC)11 for UK participants, and the L V Prasad Functional Vision Questionnaire (LVP-FVQII) for participants in India.12 While it would be desirable to use the same instrument in both settings, differences in language and activities of daily living mean that there is no validated, universal tool that could be used both in India and in the UK.

Across all sites, we will measure VRQoL, using the Impact of Vision Impairment for Children Questionnaire.13

In the UK only, we will use three reading assessment tools which are available in English, but not Telugu, the local language spoken by most children in Hyderabad: (1) the Neale Analysis of Reading Ability (NARA, a test of reading accuracy, comprehension and speed),14 15 a tool which measures visual function and comprehension. This is a tool commonly used in educational settings; it has only been used in one previous study with children with low vision. (2) To measure reading speed, we will use the International Reading Speed Texts (IReST).16 (3) to measure peak reading speed, near VA and critical print size, we will use the MNREAD Acuity Charts, University of Minnesota, USA (MNREAD) test.17 NARA and IREST will be tested at baseline using the participant’s currently preferred LVA, and at 3 and 6 months using the allocated study device, excluding text-to-speech conversion; the assessment will be recorded as audio file for evaluation by a masked observer. MNREAD will be performed using spectacle correction only.

From the participant’s diary and from semistructured interviews (see online supplementary material), we will record as free text the participant’s experience of independent access to the curriculum, any adverse outcomes (loss of motivation, negative peer comments) and accessibility and impact of the allocated device on the participant. At the end of the observation period, we will collect feedback from the participants’ teachers with regards to their impression of the impact of the allocated device on participants. We will report the cost of the devices as cost of device and training. We will provide initial training as part of the study. For ongoing technical support, we will rely on the manufacturers’ and suppliers’ support helplines.

Lastly, we will record demographic data (age at study entry, gender, ethnic group), ophthalmic history (time since diagnosis of VI, underlying ophthalmic diagnosis) and visual function (BCVA for distance and near, monocularly and binocularly, at each timepoint, recorded in logMAR; reading acuity on the MNREAD chart with refractive correction, but without LVA).18

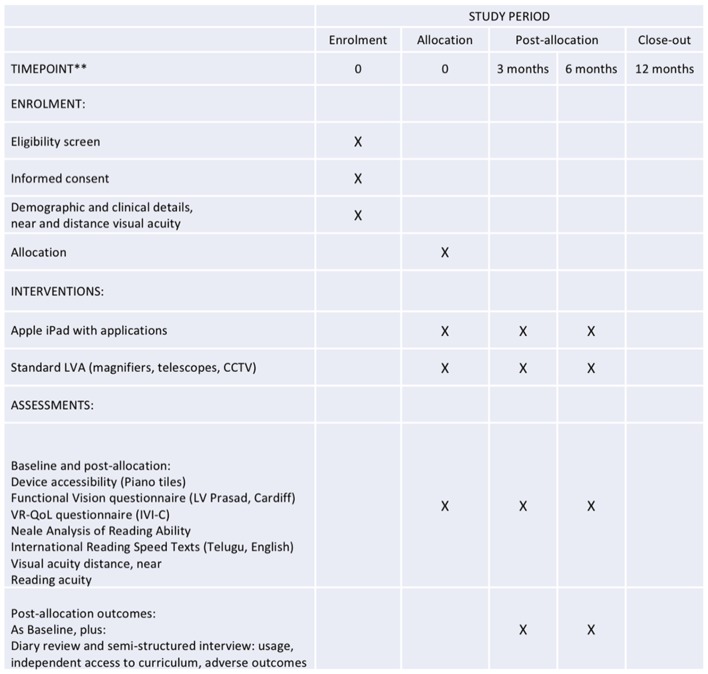

Participant timeline

Each participant will be in the study for 6 months from randomisation, with assessments at baseline, 3 and 6 months. The schedule of assessments is summarised in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schedule of enrolment, interventions and assessments (after SPIRIT20 21). CCTV, closed-circuit television; IVI-C, Impact of Vision Impairment for Children; LVA, low-vision aid; VRQoL, vision-related quality of life.

Sample size

This trial will enrol 40 students, 20 in the UK and 20 in India. A sample size of 20 is commonly used in feasibility studies. As this is the first RCT of an AT for children with low vision, a formal sample size calculation was not possible; there are no data on expected recruitment and retention. We decided on a target sample size that appears achievable over a 6-month period at one site in India and two sites in the UK. In addition, there are no data on effect size of AT for reading in children, and no data on effect size of conventional LVAs on any of the selected outcomes other than near and distance acuity. A sample size of 20 per site therefore appears appropriate to gather initial information.

Recruitment

We will identify eligible participants from low-vision clinics at Moorfields in London, from students known to their local vision impairment teams in Bedford Borough and Central Bedfordshire and the low-vision clinic at the LVPEI in Hyderabad.

The initial approach about the study will be conducted as follows:

At MEH London: a member of the clinical team providing low-vision services for children and young people will tell the family about the study and gain permission to be approached by a member of the research team. Moorfields also operate an opt-out policy which allows research teams to approach patients eligible for research about research projects. This policy clearly states that patients/families are free to decline study participation. There is no coercion.

At CDC Bedford: Students known to the Bedfordshire teachers for visually impaired students will be approached, along with their family.

At LVPEI: a member of the clinical team will first approach patients and their family.

Once a young person and their family have expressed an interest in taking part, we will provide verbal and written study information. An accredited paediatric optometrist who is a member of the research team (MDC, VKG, RT, SB) will obtain written consent from a parent or carer, and will invite children/young people to give their assent in writing or verbally.

Assignment of interventions

Allocation sequence generation and implementation

Young people who agree to take part will be randomised to receive either a tablet computer with low-vision applications or standard low-vision care. Allocation will be at a 1:1 ratio. At MEH London and CDC Bedford, randomisation will be prepared by the senior data manager in the Research & Development (R&D) department using permuted blocks of varying sizes in the statistical programme STATA. Researchers will phone Moorfields R&D department after each enrolment to obtain the randomisation allocation; the senior data manger will record patient’s study ID, hospital number, randomisation allocation and randomisation date on the trial randomisation log file. Randomisation for the participants at the LVPEI, India, will use a web-based tool (https://www.sealedenvelope.com), operated by an optometrist in the low-vision clinic team who is not involved in the study. The researcher will contact the optometrist to obtain information about the allocated treatment as participants are enrolled.

Allocation concealment mechanisms

The study optometrist will contact the senior data manager (Moorfields) or the member of staff holding the randomisation schedule (LVP) for randomisation, so while allocation sequence is concealed from the research team, the allocated intervention will not be concealed. As participants attend a wide range of schools, the risk of contamination by participants exchanging allocated equipment is low. Each participant will receive a password required to use their device and will be asked not to share it with others.

Masking

Masking of participants to the intervention will not be possible, which may cause performance bias. In order to avoid detection bias, we will mask outcome assessors to the intervention by recording reading performance as audio files (NARA, IREST), which will be subsequently evaluated by a masked observer. CVAQC and LVP-FVQII questionnaires will be administered by a masked observer. Diaries will be reviewed in masked fashion.

Data collection, management and analysis

Data collection methods

Data will be collected from patients in accordance with the patient consent form, patient information sheet and the study protocol. Patients will be assigned a study number after consent prior to randomisation. This number will be used on all case report forms, questionnaires and interview materials. Two separate databases will be built, one for UK and another for LVP which will capture pilot information for analysis. This will contain demographic data and information on the primary outcomes only.

Exploratory data will be captured as follows: all sites will use a standardised paper-based case report form and a standardised Microsoft Office Excel spreadsheet as database. At MEH London, MC will collect data and transfer them onto the spreadsheet; at CDC Bedford, RT and at LVP, SB and VKG will carry out data collection and transfer.

Data management (handling, processing and storage)

Data within the MEH database will be analysed by AQ, who will not meet the participants or be involved in data collection. UCL as study sponsor will act as the data controller for the study. The data from LVP will remain with VKG for statistical analysis and she will act as the data controller.

For the data from MEH London and CDC Bedford, ADN will process, store and dispose of all described data in accordance with all applicable legal and regulatory requirements, including the Data Protection Act 1998 and any amendments thereto. Data will be stored centrally and kept in locked, secure access filing cabinets or on password-protected NHS computers on hospital premises; this includes electronic data and case report forms, questionnaires and interview materials.

For the data from the LVPEI, India, VKG will process, store and dispose of all described data in accordance with all applicable legal and regulatory requirements. Data will be stored centrally at the LVPEI, Hyderabad, and kept in locked, secure access filing cabinets or on password-protected hospital computers on hospital premises; this includes electronic data and case report forms, questionnaires and interview materials.

UCL and each participating site recognise that there is an obligation to archive study-related documents at the end of the study. The chief investigator confirms that she will archive the study master file at Moorfields Eye Hospital for the period stipulated in the protocol and in line with all relevant legal and statutory requirements. The principal investigator at each participating site agrees to archive his/her respective site’s study documents for Moorfields Eye Hospital, the Child Development Centre Bedford and the LVPEI, and in line with all relevant legal and statutory requirements.

Statistical methods

This is a pilot RCT, and data will be used to help design a definitive study. The dataset in India and the dataset in the UK will be handled and analysed separately, as randomisation methods and some of the outcomes measures (such as functional visual ability) differ between the two settings. We will use descriptive statistical methods only (proportions, mean/SD if data are normally distributed and median/IQR if not), and will not make comparisons between groups.

Participant retention

This is one of the primary outcomes mentioned earlier. Compliance, defined as usage of the allocated device, will be monitored by diary. We will attempt to reduce attrition bias by staying in touch with participants throughout the study, by text messages, emails and phone calls and (in Bedford) visits to the educational setting. If participants wish to withdraw after they have been allocated to a treatment group, we will ask them to undergo a final assessment. We will record reasons for withdrawal on the case report form (free text). Data collected up to the point of withdrawal will be used in the data analysis.

Data monitoring

The sponsor’s data monitoring and auditing procedures will apply, that is, each site will, twice a year, send the sponsor an update on the following information: delegation log, adverse event log and deviation log. In addition, the lead site (Moorfields London) will send the sponsor a copy of the annual progress report when it is submitted to the Research Ethics Committee.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MDC, HU, VKG, CB and AD-N designed the study and secured funding. MDC, RT, HU, SB and VKG conducted the study and acquired the data. AQ, CB, MDC and VKG analysed the data. The present manuscript was drafted by AD-N and critically reviewed and amended by all authors; the revision was equally reviewed by all authors.

Funding: This study was funded by British Council for the Prevention of Blindness and by Apple Inc, and sponsored by University College London.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: National Research Ethics Committee North of Scotland/Grampian 15/NS/0068.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Funding

This work will be supported by a grant of £50 530 from the British Council for the Prevention of Blindness (BCPB) and by Apple (iPads and additional support for study site in India). The BCPB encouraged the authors to double the originally envisaged sample size to the current numbers. Apple supports this work by providing all equipment to the site in India. Apple has not influenced the study design.

Insurance/indemnity

University College London holds insurance against claims from participants for harm caused by their participation in this clinical study. Participants may be able to claim compensation if they can prove that UCL has been negligent. However, if this clinical study is being carried out in a hospital, the hospital continues to have a duty of care to the participant of the clinical study. University College London does not accept liability for any breach in the hospital’s duty of care or any negligence on the part of hospital employees. This applies whether the hospital is an NHS Trust or otherwise. Similarly, LVPEI holds a public liability policy for insurance against claims from public (patient/visitor) for harm/injury or damage caused to them or their vehicle within the premises of the hospital.

Timeline, milestones and monitoring

From grant activation after ethical approval, the project will have an active participant recruitment, intervention and assessment phase of 12 months, preceded by 1 month for purchase of equipment and followed by 2 months of analysis and write-up.

Discussion

This pilot trial will be the first RCT in the field of low-vision care for children and young people, bringing robust methodology to this research area. Besides traditional clinical measures of vision, the inclusion of educational outcomes in our study will provide highly valuable information to families and teachers of children with low vision. Education constitutes a vital component of a child/young person’s ‘professional occupation’. A study design combining clinical and educational data is therefore ideally suited to capture information relevant to young people’s daily lives.

We will report feasibility outcomes which will help design a full RCT (recruitment and retention rates, which will inform sample size) and provide initial information about accessibility of the selected AT devices.

Limitations

This trial has a small sample size, with 10 participants in each treatment arm in each of the two participating countries. However, in the absence of prior data, we consider this sample size acceptable to assess feasibility.

Our age range is deliberately broad, from 10 to 18 years. There are likely to be significant differences between young people of 10 years and those of 18 years in terms of complexity of schoolwork, volume of homework and acceptability of using AT. We have not attempted to balance the age of participants in each group but suggest that this be considered in future trials of this nature.

Our geographical spread is wide and the levels of support already received by children differ greatly between the UK and India. Although there are teachers for the visually impaired in India, they are typically employed in special schools for the blind and are well versed with Braille. There is not an analogous support system for children with low vision in mainstream schools. However, most teachers in these schools encourage children to use the prescribed low-vision devices and make the required arrangements in the classroom, for example, seating young people with VI in the first row and allowing extra time to copy from the board.

The study design reduces the risk of some but not all types of bias. Randomisation, allocation concealment and masked assessment will reduce selection, performance and detection bias. Masking of participants is not possible, so some performance and social desirability bias remain. The possibility of obtaining an iPad, if taking part in the trial, may influence recruitment rates, but this would affect all participants equally. It is not yet known whether allocation of an iPad might have an impact on retention rates; the attractiveness of electronic devices to young people may be a source of differential bias between the study arms. In order to minimise this source of bias, those participants who have been allocated an iPad for the trial will be asked to return it on the last study visit, and those who have been allocated standard care will then have the opportunity to have an iPad for 6 months, without further assessments. We will analyse dropouts in each group and this may affect the design of any future studies we perform in this area, for example, we may ensure each participant receives a device to keep at some stage.

We rely on self-report for measuring device use, which may be a source of error. We initially considered using tracking software to determine the time for which devices were used (and what they were being used for) but felt there were significant practical, ethical and privacy concerns when doing this.

Strengths

Generaliability

Particular emphasis in this study will be placed on understanding barriers to enrolment. We will document reasons for not wishing to take part, such as lack of time for research appointments and attitudes towards electronic devices for use at school. We expect that the three study sites will encounter a variety of operational issues, some of which may differ between sites and countries.

Having research sites in a high-income and in a low-income country raises certain difficulties: QoL tools need to reflect local activities of daily living, reading measurement tools need to be presented in the local language and randomisation of participants in different time zones is challenging if relying on a central randomisation facilitator.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics

This work was approved by the National Research Ethics Committee North of Scotland/Grampian 15/NS/0068, by the sponsor’s (University College London) local research ethics committee and by the local Research Ethics Committee at the LV Prasad Institute in Hyderabad, India. Research Ethics Committee and the funders will be notified of any changes to the protocol.

All participants aged ≥16 years will be asked to provide written confirmation of informed consent; in younger participants, we will obtain written consent from a parent/carer and will invite the young person to sign an assent form. Children are a vulnerable population. We will ensure that children can express their feelings about taking part in the study. Whenever possible we will invite children to give written or verbal assent. If a child appears uncomfortable taking part, we will not enrol them. Only patients for whom written consent can be obtained from parents or guardians will be enrolled. If non-English speaking families wish to take part, we will use a telephone-based interpretation service to communicate.

As tablet computers are attractive to young children, it would not be fair to limit access to these devices to the intervention group only. We will, therefore, ask participants to return the devices at the end of the 6-month study period and issue them to the control group participants for 6 months. This will be after the end of the observation period, and no additional data will be collected.

Reporting and dissemination

We will disseminate our findings through presentations at national and international conferences, through publications in scientific journals, at staff meetings and through feedback to participants. AHDN is a member of the Vision 2020/UK Vision Strategy Children with Low Vision Group, from where findings can be disseminated via the Vision2020, RNIB and Blind Children UK/Guide Dogs routes. MDC is a committee member of the International Society for Low Vision Research and Rehabilitation which the largest international meeting for researchers and clinicians in low vision.

bmjopen-2017-015939supp001.pdf (320KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-015939supp002.doc (121KB, doc)

bmjopen-2017-015939supp003.pdf (40.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-015939supp004.jpg (8KB, jpg)

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Management of low vision in children. Bangkok: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gilbert C, Muhit M. Twenty years of childhood blindness: what have we learnt? Community Eye Health 2008;21:46–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gilbert CE, Ellwein LB. Refractive Error Study in Children Study Group. Prevalence and causes of functional low vision in school-age children: results from standardized population surveys in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2008;49:877–81. 10.1167/iovs.07-0973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Frick KD, Hanson CL, Jacobson GA. Global burden of trachoma and economics of the disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2003;69(5 Suppl):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. RNIB. Eye Work Project. 2013. http://www.rnib.org.uk/aboutus/contactdetails/nireland/services/niemployment/pages/eyework.aspx (accessed 20 Mar 2013).

- 6. Alves CC, Monteiro GB, Rabello S, et al. Assistive technology applied to education of students with visual impairment. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2009;26:148–52. 10.1590/S1020-49892009000800007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gill K, Mao A, Powell AM, et al. Digital reader vs print media: the role of digital technology in reading accuracy in age-related macular degeneration. Eye 2013;27:639–43. 10.1038/eye.2013.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crossland MD, Silva RS, Macedo AF. Smartphone, tablet computer and e-reader use by people with vision impairment. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2014;34:552–7. 10.1111/opo.12136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barker L, Thomas R, Rubin G, et al. Optical reading aids for children and young people with low vision. Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2015;3:CD010987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thomas R, Barker L, Rubin G, et al. Assistive technology for children and young people with low vision. Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2015;6:CD011350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Khadka J, Ryan B, Margrain TH, et al. Development of the 25-item Cardiff Visual Ability Questionnaire for Children (CVAQC). Br J Ophthalmol 2010;94:730–5. 10.1136/bjo.2009.171181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gothwal VK, Lovie-Kitchin JE, Nutheti R. The development of the LV Prasad-Functional Vision Questionnaire: a measure of functional vision performance of visually impaired children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2003;44:4131–9. 10.1167/iovs.02-1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cochrane GM, Marella M, Keeffe JE, et al. The impact of Vision Impairment for Children (IVI_C): validation of a vision-specific pediatric quality-of-life questionnaire using Rasch analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:1632–40. 10.1167/iovs.10-6079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Douglas G, Grimley M, Hill E, et al. The use of the NARA for assessing the reading ability of children with low vision. Br J Vis Impair 2002;20:68–75. 10.1177/026461960202000204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hill E, Long R, Douglas G, et al. Neale analysis of Reading Ability for readers with low vision. A supplementary manual to aid the assesssment of partially sighted pupils' reading using the Neale Analysis of Reading Ability (NARA) Birmingham, UK: Visual Impairment Centre for Teaching and Research; School of Education; University of Birmingham 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Trauzettel-Klosinski S, Dietz K. Standardized Assessment of Reading Performance: the New International Reading speed texts IReST. Investigative Opthalmology & Visual Science 2012;53:5452–61. 10.1167/iovs.11-8284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Legge GE, Ross JA, Luebker A, et al. Psychophysics of Reading. VIII. the Minnesota Low- Vision Reading Test. Optometry and Vision Science 1989;66:843–53. 10.1097/00006324-198912000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Virgili G, Cordaro C, Bigoni A, et al. Reading acuity in Children: evaluation and reliability using MNREAD Charts. Investigative Opthalmology & Visual Science 2004;45:3349–54. 10.1167/iovs.03-1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, et al. PAFS consensus group. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2016;2:64. 10.1186/s40814-016-0105-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586. 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-015939supp001.pdf (320KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-015939supp002.doc (121KB, doc)

bmjopen-2017-015939supp003.pdf (40.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-015939supp004.jpg (8KB, jpg)