Abstract

Objectives

Smoking is associated with adverse health outcomes among drug users, including those in treatment. To date, however, there has been little evidence about smoking patterns among people receiving opioid-dependence treatment in developing countries. We examined self-reported nicotine dependence and associated factors in a large sample of opioid-dependent patients receiving methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) in northern Vietnam.

Setting

Five clinics in Hanoi (urban area) and Nam Dinh (rural area).

Participants

Patients receiving MMT in the settings during the study period.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

We collected data about smoking patterns, levels of nicotine dependence and other covariates such as socioeconomic status, health status, alcohol use and drug use. The Fagerström test was used to measure nicotine dependence (FTND). Logistic regression and Tobit regression were employed to examine relationships between the smoking rate, nicotine dependence and potentially associated variables.

Results

Among 1016 drug users undergoing MMT (98.7% male), 87.2% were current smokers. The mean FTND score was 4.5 (SD 2.4). Longer duration of MMT (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.96 to 0.99) and being HIV-positive (OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.88) were associated with lower likelihood of smoking. Being employed, older age at first drug injection and having long duration of MMT were inversely related with FTND scores. Higher age and continuing drug and alcohol use were significantly associated with higher FTND scores.

Conclusion

Smoking prevalence is high among methadone maintenance drug users. Enhanced smoking cessation support should be integrated into MMT programmes in order to reduce risk factors for cigarette smoking and improve the health and well-being of people recovering from opiate dependence.

Keywords: Cigarette smoking, tobacco use, nicotine dependence, methadone maintenance treatment, Vietnam

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study included a large sample in multiple clinics in urban and rural areas.

The study employed validated instruments to increase the comparability of the study.

The causal relationships could not be established due to the cross-sectional design.

All data were gathered by retrospective self-report without biochemical confirmation, which might may mask under-reporting of ongoing drug use.

The convenience sampling strategy limited the generalisability of findings.

Introduction

Despite the reduction of smoking worldwide, cigarette smoking rates remain high among opiate-dependent individuals—three or four times higher than in the general population.1–4 A systematic review of Guydish et al in 2011 indicated that smoking rates among patients in addiction treatment ranged from 65% to 87.2%.5 Smoking is a primary cause of morbidity and mortality in illicit drug users.6 7 Evidence indicates that the death rates of smokers who had received opioid abuse treatment were four times greater than that of their counterparts.8 Additionally, smokers with a range of other substance abuse problems were more likely to die due to smoking-related illnesses compared with their non-smoking peers.6 8

Methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) is an effective method to reduce opiate use and improve health status.9 10 However, some evidence suggests that short-term MMT may increase smoking in a dose-dependent relationship, with higher dose of MMT associated with greater nicotine dependence.11–13 Nicotine appears to make methadone or other opiates more efficaciously reinforced14; therefore, MMT patients may be more likely to continue to smoke, and to smoke heavily, when taking MMT to counteract the sedating effects of methadone or to produce a more pleasurable experience when tobacco and methadone are used together.1 15

In contrast, a study by Helena et al found that people with a long duration of MMT were likely to change their smoking habits, reducing nicotine dependence and cigarette smoking.16 In addition, some prior research suggests a high level of motivation to quit smoking among long-term MMT patients.17 However, other research indicates that there is no significant association between ongoing MMT and smoking levels or quitting attempts.18

Globally, Vietnam is one of the countries with very high prevalence of tobacco smoking. Approximately 23.8% of adults smoke, and there is a major gender difference, with 47.4% of men and 1.4% of women being current cigarette smokers.19 Smoking is a major contributor to disease burden in Vietnam, accounting for 6.2% of total deaths.20 Health surveys of people with opioid dependence have described sexual activities,21 concurrent drug use,22 23 quality of life21 and health service utilisation,24 but there has been little analysis of smoking behaviour in this population in Vietnam. This study explored the prevalence of smoking and levels of nicotine dependence, and associated factors among MMT patients. Our study is among the first to provide evidence on the pattern of smoking cigarettes during opioid-dependence treatment in Vietnam. The purpose was to contribute evidence to support implementation of dedicated smoking cessation services for opiate users in treatment in Vietnam.

Materials and methods

Survey design and sampling

We conducted a cross-sectional study from June to August 2013 at five clinics in Hanoi and Nam Dinh. These two provinces have a high prevalence of HIV-positive patients in the northern region of Vietnam, with 19 987 and 3577 people living with HIV/AIDS, respectively.25 Sampling was undertaken at clinics at central, provincial and district levels that had at least 150 MMT patients. The characteristics of the study sites are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Study settings and sample size

| Level | Settings | Site name | Type of services | Sample size |

| District (urban) | Nam Dinh City | Provincial AIDS Centre | MMT + VCT | 270 |

| District (rural) | Xuan Truong District | District Health Centre | MMT + VCT + ART + GH | 151 |

| District (urban) | Tu Liem District | District Health Centre | MMT + VCT + ART + GH | 201 |

| District (urban) | Long Bien District | District Health Centre | MMT + VCT + ART + GH | 184 |

| District (urban) | Ha Dong District | Regional Polyclinic | MMT+ GH | 210 |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; GH, general healthcare; MMT, methadone maintenance treatment; VCT, voluntary counselling and testing.

Participant recruitments

Participants were eligible if they (1) received daily methadone, (2) were aged ≥18 years and (3) agreed to provide written informed consent. Patients were excluded if they had any health or communication problems that prevented them from answering the questionnaire.

Eligible patients were invited when they visited the clinics. If they agreed to enrol, they were asked to give written informed consent. A private room in each clinic was arranged to ensure confidentiality and to create a comfortable atmosphere during the interview. A sample of 1016 patients was enrolled in the study, accounting for 90% of MMT patients in five clinics.

Data collectors did not engage in the provision of care or treatment. No direct healthcare providers were involved in the interview or handling of data. Interviewers were well-trained Master of Public Health students from Hanoi Medical University.

Measures and instruments

Smoking-related variables

The primary outcome was current smoking status, categorised into two groups: current smoker (yes/no). Participants were classified as a current cigarette smoker if they have ever smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their life and have smoked in the last 30 days. Those who have never smoked 100 cigarettes and not currently smoking or participants who have smoked 100 cigarettes but have been abstinent in the last 30 days were categorised as non-smokers.26 Among current smokers, nicotine dependence was measured by the Fagerström test for nicotine dependence (FTND).27 28 The FTND instrument has been applied elsewhere in Vietnam.29 The total scores range from 0 to 10. The higher the Fagerström score indicates the greater nicotine dependence. Regarding FTND score, patients were categorised into five groups: 0–2, very low; 3–4, low; 5, moderate; 6–7, high; and 8–10, very high.

Study covariates

Socio-demographic variables consisted of sex, age, monthly income, employment status, educational attainment, residential area and marital status. Monthly household income included all sources of income for each household member and was collected via self-reported information by patients. Based on income information, patients were classified into five quintile groups: poorest, poor, middle, rich and richest.

Health status was self-reported by employing the five-level EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L) instrument.30 This includes five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression). The EQ-5D-5L has been validated in Vietnamese context.31 Respondents who experienced from ‘slightly’ to ‘extremely’ on an item were categorised as ‘currently having pain or anxiety’. Those who reported no pain or anxiety were categorised as ‘no pain/anxiety’. Other health conditions examined included HIV infection status and whether they received antiretroviral treatment (ART).

Alcohol use was assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test—Consumption (AUDIT-C), a brief version of the 10-question AUDIT instrument.32 33 The AUDIT-C score ranges from 0 to 12, where ≥4 in men and ≥3 in women are considered at-risk drinking.34 The higher score means the greater alcohol dependence. The AUDIT-C instrument has been validated for Vietnamese populations elsewhere.35 36

Drug use characteristics were assessed regarding history of drug use, age at onset of drug use and drug injection and number of episodes of drug rehabilitation.35 Participants who reported using any substance (heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine) at least once within the past month were considered concurrent drug users during MMT. Duration of MMT was assessed by self-reported.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using Stata V.12.0 for Windows. t-Tests, Mann-Whitney tests and χ2 tests were applied to identify differences among socio-demographic, drug and alcohol-related and health-related characteristics by current smoking status (yes/no).

Multivariate logistic regression, combined with polynomial fractions for the duration of MMT treatment, was employed to determine factors associated with being a current smoker. Additionally, this model controlled for nesting of participants within each of the five clinic sites. Variables associated with the outcome in bivariate analysis with a p<0.25 were included in the multivariate model manually in a forward stepwise manner. Only statistically significant variables with a p<0.05 were retained in the final model.

Because the FTND score was censored from 0 to 10, we used Tobit regression to examine the relationships between FTND scores and potentially related factors.37 We also used a stepwise backward strategy, which is based on the log-likelihood ratio test. The threshold of p value<0.1 was used to include variables. All potential interactions were examined. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was employed to assess model calibration. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Table 2 indicates the characteristics of respondents. Most participants were men (98.7%) compared with just 1.3% of women, and they mainly came from urban areas (85.15). The mean age was 36.8 years (SD 7.6). Most respondents had less than a high school education (55.3%). The majority were married or lived with their partners (67.7%). One-fifth of respondents were employed. The average monthly income was 5.2 million VND, approximately US$250 (SD 4.2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of study participants by smoking status

| Current smoker | Total | p Value | |||

| No | Yes | ||||

| N (%) | 130 (12.8) | 886 (87.2) | 1016 (100) | ||

| Socio-demographics | |||||

| Age in years, mean years (SD) | 38.6 (8.3) | 36.5 (7.5) | 36.8 (7.6) | <0.01 | |

| Gender, n (%) | |||||

| Female | 3 (23.1%) | 10 (76.9%) | 13 (1.3) | 0.26 | |

| Male | 127 (12.7%) | 876 (87.3%) | 1003 (98.7) | ||

| Monthly income (million VND), mean (SD) | 4.8 (3.8) | 5.2 (4.2) | 5.2 (4.2) | 0.29 | |

| Marital status (n, %) | |||||

| Single/divorced/separated/widowed | 35 (10.7) | 293 (89.3) | 328 (32.3) | 0.16 | |

| Live with spouse/partner | 95 (13.8) | 593 (86.2) | 688 (67.7) | ||

| Education (n, %) | |||||

| Less than high school | 80 (14.2) | 482 (85.8) | 562 (55.3) | 0.18 | |

| High school | 40 (10.3) | 347 (89.7) | 387 (38.2) | ||

| More than high school | 10 (14.9) | 57 (85.1) | 67 (6.5) | ||

| Location (n, %) | |||||

| Urban | 104 (12) | 761 (88) | 865 (85.1) | 0.08 | |

| Rural | 26 (17.2) | 125 (82.8) | 151 (14.9) | ||

| Employment status (n, %) | |||||

| Unemployed | 39 (14.9) | 222 (85.1) | 261 (25.5) | 0.46 | |

| Self-employed | 64 (11.8) | 478 (88.2) | 542 (53.4) | ||

| Employed | 27 (12.7) | 186 (87.3) | 213 (21.1) | ||

| Substance use, n (%) | |||||

| Hazardous drinking (n, %) | 35 (11.6) | 266 (88.4) | 301 (29.6) | 0.88 | |

| History of drug injection (n, %) | 81 (10.9) | 665 (89.1) | 746 (73.4) | <0.01 | |

| Current drug use (n, %) | 4 (8.2) | 45 (91.8) | 49 (4.8) | 0.32 | |

| Age of drug use, mean age (SD) | 25.7 (7.8) | 24.4 (6.6) | 24.5 (6.7) | 0.04 | |

| Age of drug injection, mean age (SD) | 26.8 (8.2) | 26.8 (7.2) | 26.8 (7.3) | 0.97 | |

| Number of drug rehabilitation, mean episode (SD) | 5.3 (7.8) | 4.8 (6.0) | 4.8 (6.3) | 0.98 | |

| MMT duration, mean months (SD) | 18.0 (12.1) | 16.3 (10.8) | 16.5 (11.0) | 0.20 | |

| Health-related characteristics | |||||

| Current ART, n (%) | 13 (19.7) | 53 (80.3) | 66 (6.5) | 0.08 | |

| Currently feeling pain, n (%) | 24 (13.3) | 156 (86.7) | 180 (17.7) | 0.81 | |

| Currently feeling anxiety, n (%) | 28 (13.3) | 182 (86.7) | 210 (20.7) | 0.60 | |

| Currently perceive mobility problem, n (%) | 8 (10.8) | 66 (89.2) | 74 (7.3) | 0.79 | |

| Currently perceive self-care problem, n (%) | 7 (17.5) | 33 (82.5) | 40 (3.9) | 0.36 | |

| Currently perceive usual activity problem, n (%) | 7 (11.7) | 53 (88.3) | 60 (5.9) | 0.79 | |

| MMT service delivery model | |||||

| MMT + VCT | 32 (11.9) | 238 (88.1) | 270 (26.6) | 0.03 | |

| MMT + GH | 17 (8.1) | 193 (91.9) | 210 (20.7) | ||

| MMT + VCT + ART + GH | 81 (15.1) | 455 (84.9) | 536 (52.8) | ||

ART, antiretroviral therapy; GH, general healthcare; MMT, methadone maintenance treatment; VCT, voluntary counselling and testing.

One-third of participants were hazardous drinkers (29.6%). Patients with a history of heroin injection accounted for >70% of the sample. Only 5 in 100 patients reported current illicit drug use during treatment (4.8%). The average length of MMT was 16.5 months (SD 11.0). Overall, 17.7% and 20.7% of participants reported currently feeling pain and/or anxiety, respectively. Respondents with mobility and self-care problem were 7.3% and 3.9%, respectively. Half of the participants were enrolled in MMT clinics that had comprehensive packages (including MMT, HIV testing and counselling services, ART and general healthcare (GH)).

Table 2 shows that the proportion of MMT patients who currently smoked was 87.3% of men and 76.9% of women. The difference between male and female smokers was not statistically significant (p=0.26), probably because of the very small number of females in this study. Smoking status was significantly different between groups regarding age, history of drug injection, age at initiation of drug use and MMT clinic models (p<0.05).

Smoking behaviour and nicotine dependence among MMT patients are revealed in table 3. Mean age of initial smoking was 17.2 years (SD 3.5), with mean duration of regular smoking being 14.1 years (SD 8.5). A total of 306,300 VND per month were spent for cigarettes (= US$15). Among smokers, mean FTND score was 4.5 (SD 2.4), and most of them were in low (27.0%) and very low dependence (26.1%) groups.

Table 3.

Smoking pattern of Vietnamese methadone maintenance treatment patients

| Characteristic | N (%) |

| Age at smoking initiation, mean years (SD) | 17.2 (3.5) |

| Duration of regular smoking, mean years (SD) | 14.1 (8.5) |

| Expense for smoking (1,000 VND per month), mean (SD) | 306.3 (289.4) |

| Fagerström test for nicotine dependence score, mean (SD) | 4.5 (2.4) |

| Nicotine dependence scale, n (%) | |

| Very low | 231 (26.1) |

| Low | 239 (27.0) |

| Moderate | 115 (12.9) |

| High | 184 (20.8) |

| Very high | 117 (13.2) |

| Number of cigarette per day, n (%) | |

| ≤10 | 409 (46.2) |

| 11–20 | 407 (45.9) |

| 21–30 | 49 (5.5) |

| >30 | 21 (2.4) |

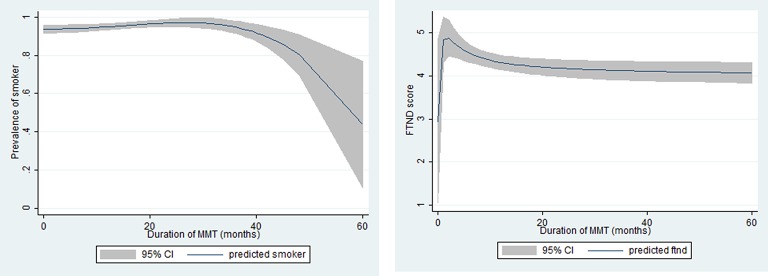

Figure 1 indicates that the smoking rate and FTND score were high in the early phase of treatment, and then significantly decreased afterwards.

Figure 1.

Smoking pattern of methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) patients regarding the duration of MMT: (A) prevalence of cigarette smoker; (B) Fagerström test for nicotine dependence (FTND) score.

The reduced multivariate model in table 4 shows that patients with high school education (OR 2.29, 95% CI 1.28 to 4.07) were more likely to report current smoking than others. Being HIV-positive (OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.88) was negatively associated with current smoking. Individuals having longer duration of MMT were less likely to smoke than others (OR 0.98; 95% CI 0.96 to 0.99).

Table 4.

Factors associated with smoking status

| Characteristics | Current smoking (yes/no) | FTND score | ||||

| OR | 95% CI | Coefficient | 95% CI | |||

| Age | 0.04* | 0.01 | 0.08 | |||

| Education (vs < high school) | ||||||

| High school | 2.29* | 1.28 | 4.07 | |||

| Occupations (vs unemployed) | ||||||

| Employed | −0.55* | −1.07 | −0.03 | |||

| Income quintile (vs poorest) | ||||||

| Rich | 0.52† | −0.03 | 1.07 | |||

| Richest | 0.63† | 0.10 | 1.17 | |||

| HIV status (vs negative) | ||||||

| Positive | 0.46* | 0.24 | 0.88 | −0.44 | −1.11 | 0.22 |

| Unknown | −0.76 | −1.76 | 0.24 | |||

| Age of first drug injection | −0.07* | −0.11 | −0.02 | |||

| Substance use | ||||||

| Interaction between current drug use and alcohol drinking (vs no use drug + no drink hazardously) | ||||||

| Only drink hazardously | 1.51 | 0.82 | 2.78 | 0.83* | 0.37 | 1.30 |

| Only use drug | 1.61* | 0.23 | 3.25 | |||

| Both use drug + drink hazardously | 1.75* | 0.24 | 3.25 | |||

| No. of drug rehabilitation (vs none) | ||||||

| 1–5 times | −0.33 | −0.75 | 0.09 | |||

| Duration of MMT (months) | 0.98* | 0.96 | 0.99 | −0.03* | −0.05 | −0.01 |

| MMT delivery model (vs MMT + VCT) | ||||||

| MMT + GH | 2.11* | 0.98 | 4.56 | |||

| MMT + VCT + ART + GH | −0.30 | −0.73 | 0.13 | |||

*p<0.05; †p<0.1.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; FTND, Fagerström test for nicotine dependence; GH, general healthcare; MMT, methadone maintenance treatment; VCT, voluntary counselling and testing.

Table 4 shows the findings from the Tobit model. Being employed, higher age at first drug injection and having long duration of MMT treatment were inverse factors for FTND scores. Further, higher age and having other single or multiple substance abuse (illicit drug, alcohol drinking) were significantly associated with higher FTND score.

Discussion

The smoking rate among MMT patients was very high, with 87.3% of men and 79.6% of women being current smokers. Smoking prevalence among the mostly male MMT clients was twice the national average for men (about 47%) in the general population.19 This is consistent with research in other countries, such as Switzerland, the USA, Australia, Canada, Mexico and England.8 38–42 The high persistence of smoking might be explained by the interactive effects of addictive substances such as methadone, narcotics and nicotine.14 Consequently, patients during MMT may be more vulnerable to smoking than in general populations. Some evidence indicates that smoking helps drug users to cope with cravings.43 44 Additionally, methadone use might contribute to high consumption of cigarettes because MMT patients smoke to counteract the sedating effects of methadone. It is also possible that there are pleasing effects when cigarettes and methadone are taken together.1 15 Together, these effects might be a barrier for smoking cessation among MMT patients. To date, in Vietnam, only two official smoking cessation clinics for opiate users in treatment, one in Hanoi and one in Ho Chi Minh City, have been in operation. Therefore, plans to scale up MMT nationally should consider integrating smoking cessation services to diminish the smoking epidemic in this population.

The current study shows that longer duration of MMT was associated with lower likelihood of current smoking and less nicotine dependence. Notably, smoking increased gradually in the first 30 months (but not significantly) and decreased remarkably afterwards. It is possible that in the initial stage of treatment smoking helped patients to counter the aftertaste of MMT and may have enhanced the pleasing effects.45 Consequently, they may have been more likely to smoke cigarettes until they could feel comfortable with the side effects of MMT. A study by Abbott46 with 189 MMT patients found that after 12 months of treatment smoking support cessation was the fourth most requested and important service although very few patients requested this service at baseline.46

Likewise, we observed higher FTND scores among patients in the first five months of MMT and then a steady decrease afterwards. It may be that in the first few months patients would require a high dose for effective treatment, which leads to more severe nicotine dependence (as indicated by the FTND score).13 47 In contrast, patients treated with MMT for a long time tend to receive stable or lower methadone doses, which may diminish nicotine dependence and promote the intention to quit smoking.3 The evidence from Vietnam is consistent with a study in Slovakia by Okruhlica et al, which suggested that the level of nicotine dependence was reduced after 12 months of treatment when the MMT dose was stabilised.48

Respondents with multiple substance abuse (alcohol and illicit drug use) had higher nicotine dependence, especially among those who concurrently used illicit drugs during MMT. The complex relationships between smoking, alcohol and drug use have been well-documented in global settings. People having one risk behaviour (such as drug use) tend to engage in other behaviours (such as smoking and alcohol).45 49–52 Therefore, these relationships during the course of MMT are clinically important that should be carefully monitored and controlled, which could help to identify who may need to receive specific cessation interventions at MMT sites.

This study also found significant associations between smoking and socio-demographic factors such as age, education and employment. Older age was correlated with higher nicotine dependence (higher FTND score). This is consistent with studies in Korea and China.53 54 Additionally, people with high school education were more likely to smoke compared with those with lower education. This is somewhat counterintuitive given the inverse relationship between education and smoking in many countries,30 but could be explained by an associated factor such as income. It might be anticipated that the highly educated respondents are more likely to have higher income to spend more on tobacco consumption.

Results of multivariable regression indicated that HIV-positive drug users were less likely to be current smokers, which could be related to perceptions about health risks. Fears about impending poor physical health due to HIV/AIDS could encourage patients to avoid risky behaviours such as smoking and alcohol use.55 However, empirical evidence worldwide suggests that people undertaking both ART and MMT often relapse and smoke more often.29 56 Furthermore, when they believe that they will not live long enough to suffer from smoking-related illnesses, or perceive that they are at a lower health risk for continued smoking especially during a stable stage of ART, they may smoke more.55 Therefore, special attention should be paid to MMT patients living with HIV in order to help them avoid risk behaviours and promote a healthier lifestyle.

This study has strengths that included a large sample size (1016 MMT patients) and high response rate, collaboration with multiple clinics in various areas and validated instruments (eg, FTND, AUDIT-C, EQ-5D-5L). Nonetheless, several limitations should be considered. First, the causal relationships could not be established due to the cross-sectional design. Additionally, all data were gathered via retrospective self-report interviews without biochemical confirmation. This may have resulted in under-reporting of ongoing drug use due and introduce recall and disclosure bias. Finally, due to the convenience sampling strategy at clinics in just two geographical areas, the generalisation of our results is limited.

Conclusion

This study revealed that smoking is highly prevalent among MMT patients, putting them at a high risk of smoking-related illnesses. Despite the decrease of smoking over the course of MMT, smoking cessation support should be integrated into MMT programmes in Vietnam in order to diminish smoking-related adverse outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: BXT, HLTN, CL, MD, HPD and HTTP conceived of the study and participated in its design. BXT, HLTN, HTTP, LHN, CTN, CL and GTN implemented the survey and compiled the data. LHN, HPN, NPTN and BXT analysed the data. All authors helped to draft the manuscript and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: IRB of Vietnam Authority of HIV/AIDS Control.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are available from the Authority of HIV/AIDS Control (VAAC). Requests for data on this study may be submitted to VAAC and go through a review process by the Scientific and Ethical Research Committee. The contact for requesting data use is Dr Phan Thi Thu Huong, email: huongphanmoh@gmail.com, Deputy Director in Research of the Vietnam Authority of HIV/AIDS Control, Ministry of Health, Vietnam.

References

- 1. Richter KP, Hamilton AK, Hall S, et al. Patterns of smoking and methadone dose in drug treatment patients. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2007;15:144–53. 10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shadel WG, Stein MD, Anderson BJ, et al. Correlates of motivation to quit smoking in methadone-maintained smokers enrolled in a smoking cessation trial. Addict Behav 2005;30:295–300. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nahvi S, Richter K, Li X, et al. Cigarette smoking and interest in quitting in methadone maintenance patients. Addict Behav 2006;31:2127–34. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Organization WH. WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco smoking. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guydish J, Passalacqua E, Tajima B, et al. Smoking prevalence in addiction treatment: a review. Nicotine Tob Res 2011;13:401–11. 10.1093/ntr/ntr048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hurt RD, Offord KP, Croghan IT, et al. Mortality following inpatient addictions treatment. role of tobacco use in a community-based cohort. JAMA 1996;275:1097–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hurt RD, Eberman KM, Croghan IT, et al. Nicotine dependence treatment during inpatient treatment for other addictions: a prospective intervention trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1994;18:867–72. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00052.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hser YI, McCarthy WJ, Anglin MD. Tobacco use as a distal predictor of mortality among long-term narcotics addicts. Prev Med 1994;23:61–9. 10.1006/pmed.1994.1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Consensus Development Panel on Effective Medical Treatment of Opiate A. Effective Medical treatment of opiate addiction. JAMA 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lowinson JH. Substance abuse: a comprehensive textbook. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chait LD, Griffiths RR. Effects of methadone on human cigarette smoking and subjective ratings. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1984;229:636–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Frosch DL, Shoptaw S, Nahom D, et al. Associations between tobacco smoking and illicit drug use among methadone-maintained opiate-dependent individuals. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;8:97–103. 10.1037/1064-1297.8.1.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Clarke JG, Stein MD, McGarry KA, et al. Interest in smoking cessation among injection drug users. Am J Addict 2001;10:159–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wapf V, Schaub M, Klaeusler B, et al. The barriers to smoking cessation in Swiss methadone and buprenorphine-maintained patients. Harm Reduct J 2008;5:10. 10.1186/1477-7517-5-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Richter KP, Choi WS, McCool RM, et al. Smoking cessation services in U.S. methadone maintenance facilities. Psychiatric services 2004;55:1258–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Baran-Furga H, Chmielewska K, Bogucka-Bonikowska A, et al. Self-reported effects of methadone on cigarette smoking in methadone-maintained subjects. Subst Use Misuse 2005;40:1103–11. 10.1081/JA-200042162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Richter KP, Gibson CA, Ahluwalia JS, et al. Tobacco use and quit attempts among methadone maintenance clients. Am J Public Health 2001;91:296–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stark MJ, Campbell BK. Cigarette smoking and methadone dose levels. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 1993;19:209–17. 10.3109/00952999309002681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. WHO. Global adult tobacco survey (GATS) in Viet Nam. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bui LN, Nguyen NTT, Tran LK, et al. Risk factors of burden of disease: a comparative assessment study for evidence-based health policy making in Vietnam. The Lancet 2013;381(S2):S23. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61277-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tran BX, Nguyen LH, Nong VM, et al. Behavioral and quality-of-life outcomes in different service models for methadone maintenance treatment in Vietnam. Harm Reduct J 2016;13:4. 10.1186/s12954-016-0091-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tran BX, Ohinmaa A, Mills S, et al. Multilevel predictors of concurrent opioid use during methadone maintenance treatment among drug users with HIV/AIDS. PLoS One 2012;7:e51569. 10.1371/journal.pone.0051569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tran BX, Ohinmaa A, Duong AT. Changes in drug use are associated with health-related quality of life improvements among methadone maintenance patients with HIV/AIDS. Quality of life research: an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 2012;21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tran BX, Phan HT, Nguyen LH, et al. Economic vulnerability of methadone maintenance patients: implications for policies on co-payment services. Int J Drug Policy 2016;31:131–7. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vietnam General Statistics Office. Report on Health Indicators 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Prevention CfDCa. Adult Tobacco Use Information: Glossary. Atlanta, USA, 2009. (10-4-2017). [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pomerleau CS, Carton SM, Lutzke ML, et al. Reliability of the fagerstrom tolerance questionnaire and the fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence. Addict Behav 1994;19:33–9. 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90049-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, et al. The fagerström Test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the fagerström tolerance questionnaire. Br J Addict 1991;86:1119–27. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nguyen NP, Tran BX, Hwang LY, et al. Prevalence of cigarette smoking and associated factors in a large sample of HIV-positive patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in Vietnam. PLoS One 2015;10:e0118185 10.1371/journal.pone.0118185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Eqol G. EQ-5D-5L user Guide: basic information on how to use the EQ-5D-5L instrument. Rotterdam, The Netherlands 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tran BX, Ohinmaa A, Nguyen LT. Quality of life profile and psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L in HIV/AIDS patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012;10:132. 10.1186/1477-7525-10-132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Giang KB, Allebeck P, Spak F, et al. Alcohol use and alcohol consumption-related problems in rural Vietnam: an epidemiological survey using AUDIT. Subst Use Misuse 2008;43(3-4):481–95. 10.1080/10826080701208111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Broyles LM, Gordon AJ, Sereika SM, et al. Predictive utility of Brief Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) for human immunodeficiency virus antiretroviral medication nonadherence. Subst Abus 2011;32:252–61. 10.1080/08897077.2011.599255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bush K, et al. The AUDIT Alcohol Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C)<subtitle>an effective brief screening test for Problem Drinking</subtitle>. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:1789–95. 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tran BX, Nguyen N, Ohinmaa A, et al. Prevalence and correlates of alcohol use disorders during antiretroviral treatment in injection-driven HIV epidemics in Vietnam. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;127:39–44 44. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tran BX, Nguyen LT, Do CD, et al. Associations between alcohol use disorders and adherence to antiretroviral treatment and quality of life amongst people living with HIV/AIDS. BMC Public Health 2014;14:27 10.1186/1471-2458-14-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Twisk J, Rijmen F. Longitudinal tobit regression: a new approach to analyze outcome variables with floor or ceiling effects. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:953–8. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Best D, Lehmann P, Gossop M, et al. Eating too little, smoking and drinking too much: wider lifestyle problems among methadone maintenance patients. Addiction Research & Theory 1998;98. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bernstein SM, Stoduto G. Adding a choice-based program for tobacco smoking to an abstinence-based addiction treatment program. J Subst Abuse Treat 1999;17:167–73. 10.1016/S0740-5472(98)00071-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tacke U, Wolff K, Finch E, et al. The effect of tobacco smoking on subjective symptoms of inadequacy ("not holding") of methadone dose among opiate addicts in methadone maintenance treatment. Addict Biol 2001;6:137–45. 10.1080/13556210020040217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Walsh RA, Bowman JA, Tzelepis F, et al. Smoking cessation interventions in Australian drug treatment agencies: a national survey of attitudes and practices. Drug Alcohol Rev 2005;24:235–44. 10.1080/09595230500170282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shin SS, Moreno PG, Rao S, et al. Cigarette smoking and quit attempts among injection drug users in Tijuana, Mexico. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15:2060–8. 10.1093/ntr/ntt099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McCarthy WJ, Zhou Y, Hser YI, et al. To smoke or not to smoke: impact on disability, quality of life, and illicit drug use in baseline polydrug users. J Addict Dis 2002;21:35–54. 10.1300/J069v21n02_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Frosch DL, Shoptaw S, Nahom D, et al. Associations between tobacco smoking and illicit drug use among methadone-maintained opiate-dependent individuals. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;8:97–103. 10.1037/1064-1297.8.1.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. McCool RM, Paschall Richter K. Why do so many drug users smoke? J Subst Abuse Treat 2003;25:43–9. 10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00065-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Abbott PJ. Case management: ongoing evaluation of patients' needs in an opioid treatment program. Prof Case Manag 2010;15:145–52. 10.1097/NCM.0b013e3181c8c72c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Elkader AK, Brands B, Selby P, et al. Methadone-nicotine interactions in methadone maintenance treatment patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2009;29:231–8. 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181a39113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Okruhlica L, Devinsky F, Klemplova D, et al. Reduction in self-reported nicotine dependence after stabilization in methadone maintenance treatment. Heroin Add & Rel Clin Probl 2003;5:39–46. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fryar CD, Hirsch R, Porter KS, et al. Smoking and alcohol behaviors reported by adults: united States. 378, 2006. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad378.pdf (accessed 17 Sep 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nyamathi AM, Sinha K, Marfisee M, et al. Correlates of heavy smoking among alcohol-using methadone maintenance clients. West J Nurs Res 2009;31:787–98. 10.1177/0193945909338851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Asher MK, Martin RA, Rohsenow DJ, et al. Perceived barriers to quitting smoking among alcohol dependent patients in treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat 2003;24:169–74. 10.1016/S0740-5472(02)00354-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Falk DE, H-y Y, Hiller-Sturmhöfel S. An epidemiologic analysis of Co-Occurring Alcohol and tobacco use and disorders. Alcohol Research and Health 2006;29:162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Park S, Lee JY, Song TM, et al. Age-associated changes in nicotine dependence. Public Health 2012;126:482–9. 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yang T, Shiffman S, Rockett IR, et al. Nicotine dependence among Chinese city dwellers: a population-based cross-sectional study. Nicotine Tob Res 2011;13:556–64. 10.1093/ntr/ntr040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Burkhalter JE, Springer CM, Chhabra R, et al. Tobacco use and readiness to quit smoking in low-income HIV-infected persons. Nicotine Tob Res 2005;7:511–22. 10.1080/14622200500186064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nguyen NT, Tran BX, Hwang LY, et al. Motivation to quit smoking among HIV-positive smokers in Vietnam. BMC Public Health 2015;15:326 10.1186/s12889-015-1672-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.