Abstract

Objectives

To compare the weight categorisation of a cohort of UK children using standard procedures (ie, comparing body mass index (BMI) centiles to age-matched UK reference data) versus an approach adjusted for maturation status (ie, matching relative to biological age).

Design

Analysis of data collected from an observational study of UK primary school children.

Setting

Schools in South West England.

Participants

Four hundred and seven 9–11 year-old children (98% white British).

Main outcome measures

Weight status was classified using BMI centiles using (1) sex and chronological age-matched referents and (2) sex and biological age-matched referents (based on % of predicted adult stature) relative to UK 1990 reference growth charts. For both approaches, children were classified as a normal weight if >2nd centile and <85thcentile, overweight if 85th and <95thcentiles, and obese if ≥95thcentile.

Results

Fifty-one children (12.5%) were overweight, and a further 51 obese (12.5%) according to standard chronological age-matched classifications. Adjustment for maturity resulted in 32% of overweight girls, and 15% of overweight boys being reclassified as a normal weight, and 11% and 8% of obese girls and boys, respectively, being reclassified as overweight. Early maturing children were 4.9 times more likely to be reclassified from overweight to normal weight than ‘on-time’ maturers (OR 95% CI 1.3 to 19).

Conclusions

Incorporating assessments of maturational status into weight classification resulted in significant changes to the classification of early-maturing adolescents. Further research exploring the implications for objective health risk and well-being is needed.

Keywords: childhood obesity, weight status, maturity, weight measurement

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The analyses are based on objective height and weight measurements of 407 children taken by trained researchers implementing a rigorous standardised protocol.

The approach is the first to demonstrate a simple and readily replicable means of exploring or adjusting for the impact of maturity timing on weight categorisation during late childhood/early adolescence.

Although the sample was representative of the diversity of children in one geographical area of the UK, the data are not nationally representative and ethnic minority groups are particularly under-represented.

Introduction

Childhood obesity is consistently linked to a greater risk of obesity in adulthood and the consequent increased risk to health through conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and certain forms of cancer.1 As a means of identifying children at elevated risk, the classification of children’s weight status is widely practised by physicians and public health teams in many countries.2–4 Yet, parents’ recognition of when a child is overweight can be as low as 25%.5 This is in part exacerbated by the normalisation of being overweight, with approximately 33% of UK 10–11 year-olds now being classified as overweight or obese. Schemes such as England’s National Child Measurement Programme (NCMP), through which over 95% of 4–5 and 10–11 year-old children are weighed each year,6 provide excellent data for monitoring population-level obesity. However, the NCMP has also been used to provide objective feedback to parents on their child’s weight status with a view to improving awareness and engaging families with weight management services. To date, however, providing NCMP data as feedback has resulted in little uptake of weight management support7 and may have alienated many parents who are angry and/or disbelieving of the information provided.7–9

Research investigating the source of parental anger and rejection of the weighing and measuring of children highlights that many parents fear that the risk of harm to their child’s health and well-being is greater from labelling them as overweight (eg, in undermining self-esteem and triggering eating disorder symptomology and poor self-esteem) than it is from being overweight.7–11 In the absence of conclusive evidence that this is not the case, and given that strong negative associations between parent–child weight talk and well-being have been reported,12 health professionals have a responsibility to ensure that any intervention that could incur such risks is based on accurate information and does not target those for whom it may not be necessary.

A primary reason that parents offer for being distrusting of the information provided about their child’s weight status is that such judgements fail to account for individual differences. In particular, parents argue that when children approach puberty, judgements of their weight status that do not take account of relative differences in pubertal development are not valid.8 While there is reliable evidence that earlier puberty is associated with a greater risk of obesity, and thus that the two may be somewhat conflated,13 researchers have also raised the question of whether it is appropriate to judge weight status based on body mass index (BMI) during puberty when some increase in body fat is normal and healthy.14 15 The use of BMI for establishing weight status in relation to health risk in children is certainly problematic, especially during the period of peak growth velocity (average onset 11.8 years in girls and 14.0 years in boys)16 when height (and therefore the weight to height ratio on which the BMI is based) is liable to considerable change. Past work using dual energy x-ray absorption (DXA) scans to provide accurate assessments of body fat demonstrates a considerable normative increase in fat mass around the trunk in both boys and girls in the lead up to the period of peak height velocity (ie, the main event referred to as ‘puberty’) regardless of physical activity and dietary fat intake.17 18 Yet, these studies have not used data to adjust estimates of a child’s weight status according to their maturity status.

There is currently no research reporting on the effect that adjustment for pubertal status could have on population estimates of obesity, or of how we could adjust the classification of risk for children who are advanced in maturity through acceptable, non-invasive means. Despite this lack of work, it would be possible to do so within a practice setting via using non-invasive means of estimating children’s maturity status that are currently available. Accordingly, the aim of this study is to investigate the degree to which the weight categorisation of a cohort of UK 9–11 year-old children differs when estimated through comparison of their BMI against chronological age-matched and sex-matched UK BMI reference charts (standard UK practice), versus when estimated using reference charts matched to their biological (ie, maturity adjusted) age. This analysis is undertaken with a view to providing a means of adjusting for expected maturity-related increases in body fat mass among children and adolescents to provide more accurate estimates of obesity prevalence. The process of generating more tailored estimates of weight status may also help to engage parents in discussions about a healthy weight for their child and has the potential to increase acceptance that a child is overweight.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 407 9–11 year-old children who formed the UK sample of the International Study of Childhood Obesity, Lifestyle and the Environment (ISCOLE).19 Participants were recruited from 26 primary schools in South West England. Schools were stratified according to pupils’ socioeconomic status (based on levels of entitlement to free school meals: high, mid and low) of the catchment area and weighted by size (large and small), and then approached sequentially to maximise the diversity of the sample of participating children. All year 6 children in participating schools were eligible to take part. The analytical sample used in this study showed little ethnic diversity: 98% were white British, compared with 90%–97% in the local authorities where data were collected, and 87% nationally.

Procedure

Detailed information of the standardised data collection protocol is published elsewhere.19 Written consent for the study was obtained from head teachers and parents, and assent provided by children prior to participation. A battery of anthropometric measurements were taken by staff trained in the ISCOLE protocol. Standing height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm without shoes with the participant’s head in the Frankfort Plane and at the end of a deep inhalation using a Seca 213 portable stadiometer (Hamburg, Germany). Body mass was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a portable Tanita SC- 240 Body Composition Analyzer (Arlington Heights, Illinois, USA). For both height and weight, two measurements were taken and the mean of the two scores used in subsequent analysis. If the two values differed by more than 0.5 cm for height, or 0.5 kg for weight, a third measure was taken, and the average of the closest two retained in the analysis. Subsequently, BMI (body mass (kg)/height (m2)) was calculated. Overarching ethical approval for the ISCOLE protocol was provided by the Pennington Biomedical Research Center Institutional Review Board, and local ethical approval was also obtained for the UK site by the institutional research ethics committee. Data were entered into a secure central web-based management system, audited by the ISCOLE coordinating centre.

Classification of maturity and weight status. Maturity status was calculated by a non-invasive means (ie, the Khamis-Roche method),20 based on the percentage of predicted adult stature that a child had attained at measurement. This method holds that among youth of the same age, individuals who are closer to their mature (ie, adult) stature are more advanced in biological maturity. A boy of 12 years who has attained 90% of predicted adult height, for example, would be considered more mature than a boy, of the same age and height, who had obtained 80% predicted adult height. The Khamis-Roche method predicts adult height from the child’s age, height and weight, and mid-height of the biological parents. Self-reported parent heights were adjusted for overestimation using equations generated from over 1000 measured and self-estimated heights from adults.21 The Khamis-Roche method has been validated against skeletal age in American youth22 and has also been applied in studies of British youth.23–25 The median error bounds (ie, the CI within which 50% of the cases for true height will fall) between actual and predicted adult stature between the ages of 9–12 fall between 2.0 and 2.5 cm in boys and 1.9 and 2.1 cm in girls, respectively.20

Maturity status was calculated using z-scores for the percentage of mature height achieved: for group comparisons, z-scores between −1.0 and +1.0 were considered ‘on time’, z-scores below −1.0 ‘late maturers’ and z-scores above 1.0 ‘early maturers’.26 To obtain an estimate of biological age, percentage of adult stature was compared with age-specific and sex-specific reference standards generated from the UK 1990 growth reference data.27 Reference standards for percentage of adult stature attained were calculated at intervals of 0.1 years for each sex. Percentages were based on mean values for stature attained at each age interval, and the mean values for stature attained at and above 18 years of age (177.6 cm in males; 163.7 cm in females). For example, a girl of 10.5 years who had attained 91.5% of predicted adult stature would have presented a value equivalent to the mean percentage of adult stature attained by UK girls aged 12.0 years. Accordingly, she would be assigned a maturational (biological) age of 12.0 years. For both standard and adjusted calculations of weight status, and in line with the threshold used for population assessment using NCMP data by Public Health England in 2016,28 overweight and obesity were judged through reference to the UK 1990 BMI reference data.29 Children with a BMI of ≥85th centile and <95th centile were classified as overweight, and children over the 95th centile as obese. The difference between the two classification systems (ie, standard and maturity adjusted) stemmed from the reference curve against which the child’s BMI was compared. To calculate standard classifications, children were matched to the reference curve appropriate to their sex and chronological age in months.

Analysis

We examined whether the classification of weight differed significantly when using standard versus adjusted BMI centiles using χ2 tests and explored whether there were differences in the number of children reclassified according to sex or maturity status using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Effect sizes were also computed to provide an indication of the meaningfulness of statistical differences; η2 indicates the effect size of F statistics in ANOVA; values ≥0.022 are considered a small but meaningful effect, ≥0.059 a moderate effect and 0.14 and upwards a large effect.30 Cohen’s d was used for two-way comparisons (≥0.2 and ≤0.5 considered a small effect, ≥0.5 and ≤0.8 a moderate effect and ≥0.8 a large effect). ORs of the probability of change in classification were calculated for early, on-time and late maturers.

Results

The sample comprised 407 children (78% of the 525 involved in the study; 223 girls (55%), mean age 10.9 years, SD=0.5, range 9.3–11.8) whose height and weight were objectively measured and whose biological parents self-reported their own heights. Average BMI was 18.3 (SD=3.0), and according to usual age and sex matched cut-offs, 51 (12.5%) children were classified as overweight and a further 51 (12.5%) obese. Slightly more girls than boys were overweight or obese (26% vs 24%, respectively). No children were underweight (BMI <2nd centile). On average, girls had reached a more advanced stage of maturity than boys (girls averaged 88% expected adult height, vs 81% for boys). Five per cent of boys and 9% of girls were late maturers, 71% of boys and 61% of girls on-time and 24% of boys and 30% of girls were early maturers.

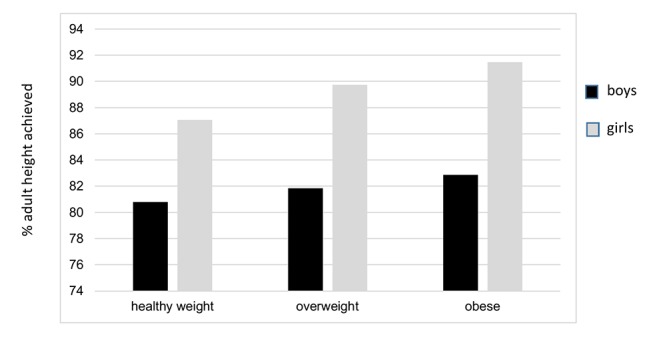

The results of a two-way (gender and weight status) ANOVA indicated that there was a significant difference in biological maturity across weight categories (F(2,401)=38, p<0.001; η2=0.16), gender (F(1,401)=422, p<0.001; η2=0.51) and a significant interaction term (F(2,401)=5.5, p=0.005; η2=0.03). The data show a trend for girls to be more biologically mature than boys at this age, for biological maturity to be more advanced in higher weight categories and for the difference in biological maturity between weight categories to be more pronounced in girls (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Trends in maturation status across weight categorisation.

Comparisons with adjusted values

For the sample as a whole, the mean difference between chronological age and biological age (ie, age for the given percentage of expected adult height achieved) was 0.18 years (SD=0.6), ranging from a delay of 1.67 years, to being advanced by 5.5 years. This latter value refers to a girl with a height of 166 cm, who had reached 99.9% of her predicted adult height; her weight status did not change when adjusting for developmental stage (she was classified as obese using both systems).

When BMI centile was adjusted for maturation, there was a small decrease in the proportion of children classified as overweight (from 12.5% to 10.6%) and obese (from 12.5% to 11.8%). This related to a small but significant decrease in the mean estimated BMI centile within the sample; standard versus adjusted calculation mean BMI=58.2 (SD=30.1) versus 57.4 (SD=28.8) (t(406)=3.09, p=0.002; d=0.02). Overall, 5 (11%) overweight or obese boys and 13 (22%) of overweight or obese girls were reclassified into a lower weight category (χ2=583, p<0.001, table 1). Only one boy and three girls were reclassified into a higher weight category.

Table 1.

Comparison of weight classifications following BMI centile adjustment

| Adjusted centiles | ||||

| Standard centiles | Healthy weight n(%) | Overweight n(%) | Obese n(%) | Total N |

| Boys | χ2 (df=4)=299, p<0.001 | |||

| Healthy weight | 139 (>99) | 1 (<1) | 0 | 142 |

| Overweight | 3 (15) | 17 (85) | 0 | 20 |

| Obese | 0 | 2 (8) | 22 (92) | 24 |

| Girls | χ2 (df=4)=290, p<0.001 | |||

| Healthy weight | 164 (>99) | 1 (<1) | 0 | 165 |

| Overweight | 10 (32) | 19 (61) | 2 (7) | 31 |

| Obese | 0 | 3 (11) | 24 (89) | 27 |

BMI, body mass index.

Of the 111 children judged to be early maturers, 59% were classified as a healthy weight using standard chronological age growth reference charts (19% overweight and 23% obese), compared with 67% following adjustment for maturity (13% overweight and 21% obese). Overweight early maturers (ie, those we consider most important to ‘get right’ on the basis of requiring intervention or not) were 4.9 times more likely to be reclassified as a normal weight following maturity adjustment than their overweight on-time peers (43% vs 13%; OR=4.9; 95% CI 1.25 to 19). There was no apparent difference for obese children reclassified as overweight (8% vs 12%; OR=0.67, 95% CI 0.10 to 4.4).

Discussion

A comparison of the weight status categorisation of a sample of 9–11 year-old UK children according to standard chronological age versus biological age growth charts resulted in the downward classification of 18% of overweight and obese children, representing 22% of overweight girls and 11% of overweight boys. Only four children (1%) were reclassified into a higher weight category. This effect was more pronounced in girls, for whom almost one in three girls who were reported to be overweight would not have been classified as such using a maturity-adjusted approach. Given the limited age range of the sample, and that boys mature on average 2 years later than girls, the effect may reach a similar extent for boys but at a later age.

Within this study, we attempted to quantify the difference that adjusting judgements of weight status by a child’s level of maturity could have on both population estimates of childhood overweight and obesity and on the treatment of individual children and families. The strengths of this work reside with basing the analysis on a broad cohort of children using robust objective measurement protocols at an age when the effects of puberty are first starting to emerge, and importantly at the age when weight measurement by health professionals takes place and the lack of consideration for maturity is known to be a source of tension between parents and health services. A limitation of this study is that the original UK 1990 dataset bases the norms on which the BMI centiles that we (and health services) use, include children of all maturity levels, not only on-time maturers. However, it is likely that the differences observed in our analyses would have been greater, rather than smaller, if the reference data had also standardised for maturity status (ie, if off-time maturers could be removed). We also note that children from ethnic minorities were under-represented in our sample.

BMI is acknowledged to be a useful but imperfect proxy indicator of fat mass (and excess fat mass) and subsequent health risk.31–33 Past work has explored how moderating factors such as sex, race and ethnicity may influence the accuracy of BMI in predicting health risk34 35; however, whereas the impact of puberty on BMI at a given chronological age is well established, few studies have attempted to quantify the impact of biological maturity has on the accuracy of weight classifications.36 A sensitivity and specificity analysis of BMI in classifying obesity (as measured by body fat mass established through DXA scans, establishing puberty through tanner scales) in adolescents of all ages in New Zealand reported 6%–12% of misclassification.36 Nonetheless, the present study is the first to demonstrate how weight classification may account for children’s maturity status in addition to age and sex when benchmarking BMI against growth reference charts,and to report on the likely effects (in terms of changes to weight classifications) of doing so. As the healthy range for BMI increases with age up to adulthood as a reflection of expected healthy increases in body fat during puberty, it is likely that early maturing children and adolescents can be a normal or healthy weight at a higher BMI than their later maturing peers: however, research specifically mapping maturity-adjusted weight categorisation to health risk is needed to formally test this hypothesis.

These findings post two key implications for practice. First, they raise the question of whether we should adjust for maturity when judging whether children or adolescents are overweight. Given the lack of evidence that weight monitoring (as undertaken through the NCMP and similar programmes) results in positive effects on children’s health and health behaviours,7 37 and some evidence that such monitoring activities could undermine their well-being and self-concept,8 9 there seems little risk that adjusting for biological maturity will result in harm (ie, children are not identified, and do not receive effective help). Conversely the practice could be of benefit if we are better able to raise awareness and engage with parents whose children remain classified as overweight or obese following adjustment as a result of showing that we have tailored the judgement to their child’s level of biological maturity. Second, the findings suggest that early-maturing children are particularly at risk of misclassification; this group are already known to be at greater risk of poor mental health38–40 and may be particularly susceptible to the negative impact of such evaluations as they generally hold more negative perceptions of the physical self (lower perceptions of attractiveness, sports competence and fitness).41 As such, early-maturing children and adolescents represent a vulnerable group with whom we should be particularly careful to minimise the potential unintended negative consequences of health policies.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: FG led in the drafting of the paper, development of the idea for the use of the ISCOLE data in this way (with SC), conduct of analyses (with CB). She was a CI for the UK ISCOLE site, involved with data collection, researcher training and quality oversight. SC provided expertise in the assessment of maturity and interpretation of findings, contributed to the development of the concept for using the ISCOLE data in this way (with FG) and contributed to the drafting of the paper. He was involved with data collection and coordination for the UK ISCOLE site. MS is the PI of the UK ISCOLE study site and contributed to the drafting of the paper. CB provided input and expertise to the analysis of the study data and contributed to the drafting of the paper. PK is the PI of ISCOLE across the 12-centre site, responsible for the design of the original study and oversight of data collection and analysis, and contributed to drafting the paper.

Funding: The ISCOLE study on which this paper is based was funded by The Coca-Cola Company. All authors except for CB were recipients of this grant. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. All researchers were independent of the funders in all aspects of their research.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Pennington Biomedical Research Center, and University of Bath Department for Health Research Ethics Committee (REACH).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No data are available for sharing.

References

- 1. Park MH, Falconer C, Viner RM, et al. The impact of childhood obesity on morbidity and mortality in adulthood: a systematic review. Obes Rev 2012;13:985–1000. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01015.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. DigitalNHS. National Child Measurement Programme. http://content.digital.nhs.uk/NCMP (cited 15 Dec 2016).

- 3. Wieske RC, Nijnuis MG, Carmiggelt BC, et al. Preventive youth health care in 11 European countries: an exploratory analysis. Int J Public Health 2012;57:637–41. 10.1007/s00038-011-0305-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Roberto C, Soo J, Pomeranz L. Regulatory strategies for preventing obesity and improving public health Managing and Preventing Obesity: Behavioural Factors and Dietary Interventions. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tompkins CL, Seablom M, Brock DW. Parental Perception of Child?s Body Weight: A Systematic Review. J Child Fam Stud 2015;24:1384–91. 10.1007/s10826-014-9945-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Digital NHS. National Child Measurement Programme: england 2015/16 school year Data Quality Statement. 2016. http://content.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB22269/nati-chil-meas-prog-eng-2015-2016-qual.pdf (accessed 15 Dec 2016).

- 7. Falconer CL, Park MH, Croker H, et al. The benefits and harms of providing parents with weight feedback as part of the national child measurement programme: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 2014;14:549 10.1186/1471-2458-14-549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gillison F, Beck F, Lewitt J. Exploring the basis for parents' negative reactions to being informed that their child is overweight. Public Health Nutr 2014;17:987–97. 10.1017/S1368980013002425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grimmett C, Croker H, Carnell S, et al. Telling parents their child's weight status: psychological impact of a weight-screening program. Pediatrics 2008;122:e682–e688. 10.1542/peds.2007-3526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Syrad H, Falconer C, Cooke L, et al. Health and happiness is more important than weight': a qualitative investigation of the views of parents receiving written feedback on their child's weight as part of the National Child Measurement Programme. J Hum Nutr Diet 2015;28:47–55. 10.1111/jhn.12217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Borra ST, Kelly L, Shirreffs MB, et al. Developing health messages: qualitative studies with children, parents, and teachers help identify communications opportunities for healthful lifestyles and the prevention of obesity. J Am Diet Assoc 2003;103:721–8. 10.1053/jada.2003.50140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gillison FB, Lorenc AB, Sleddens EF, et al. Can it be harmful for parents to talk to their child about their weight? A meta-analysis. Prev Med 2016;93:135–46. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Prentice P, Viner RM. Pubertal timing and adult obesity and cardiometabolic risk in women and men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes 2013;37:1036–43. 10.1038/ijo.2012.177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. O'Dea J, Abraham S. Should body-mass index be used in young adolescents? Lancet 1995;345:657 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)90563-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bini V, Celi F, Berioli MG, et al. Body mass index in children and adolescents according to age and pubertal stage. Eur J Clin Nutr 2000;54:214–8. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Malina RM, Bouchard C, Bar-Or O. Growth, Maturation, and physical activity. Human Kinetics, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sherar LB, Esliger DW, Baxter-Jones AD, et al. Age and gender differences in youth physical activity: does physical maturity matter? Med Sci Sports Exerc 2007;39:830. 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180335c3c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sherar LB, Eisenmann JC, Chilibeck PD, et al. Relationship between trajectories of trunk fat mass development in adolescence and cardiometabolic risk in young adulthood. Obesity 2011;19:1699–706. 10.1038/oby.2010.340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Katzmarzyk PT, Barreira TV, Broyles ST, et al. The International Study of Childhood Obesity, Lifestyle and the Environment (ISCOLE): design and methods. BMC Public Health 2013;13:900 10.1186/1471-2458-13-900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Khamis HJ, Roche AF. Predicting adult stature without using skeletal age: the Khamis-Roche method. Pediatrics 1994;94:504–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Epstein LH, Valoski AM, Kalarchian MA, et al. Do children lose and maintain weight easier than adults: a comparison of child and parent weight changes from six months to ten years. Obes Res 1995;3:411–7. 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00170.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Malina RM, Dompier TP, Powell JW, et al. Validation of a noninvasive maturity estimate relative to skeletal age in youth football players. Clin J Sport Med 2007;17:362–8. 10.1097/JSM.0b013e31815400f4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cumming SP, Standage M, Gillison F, et al. Sex differences in exercise behavior during adolescence: is biological maturation a confounding factor? J Adolesc Health 2008;42:480–5. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cumming SP, Standage M, Loney T, et al. The mediating role of physical self-concept on relations between biological maturity status and physical activity in adolescent females. J Adolesc 2011;34:465–73. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Smart JE, Cumming SP, Sherar LB, et al. Maturity associated variance in physical activity and health-related quality of life in adolescent females: a mediated effects model. J Phys Act Health 2012;9:86–95. 10.1123/jpah.9.1.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Malina RM, Cumming SP, Morano PJ, et al. Maturity status of youth football players: a noninvasive estimate. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2005;37:1044–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Freeman JV, Cole TJ, Chinn S, et al. Cross sectional stature and weight reference curves for the UK, 1990. Arch Dis Child 1995;73:17–24. 10.1136/adc.73.1.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Public Health England (internet) 2016. Measuring and interpreting BMI in Children. http://www.noo.org.uk/NOO_about_obesity/measurement/children (cited 15 Dec 2016).

- 29. Cole TJ, Freeman JV, Preece MA. Body mass index reference curves for the UK, 1990. Arch Dis Child 1995;73:25–9. 10.1136/adc.73.1.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fritz CO, Morris PE, Richler JJ. Effect size estimates: current use, calculations, and interpretation. J Exp Psychol Gen 2012;141:2–18. 10.1037/a0024338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Freedman DS, Mei Z, Srinivasan SR, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and excess adiposity among overweight children and adolescents: the Bogalusa Heart Study. J Pediatr 2007;150:e2:12–17. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.08.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Freedman DS, Sherry B. The validity of BMI as an indicator of body fatness and risk among children. Pediatrics 2009;124(Suppl 1):S23–S34. 10.1542/peds.2008-3586E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mei Z, Grummer-Strawn LM, Pietrobelli A, et al. Validity of body mass index compared with other body-composition screening indexes for the assessment of body fatness in children and adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr 2002;75:978–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Duncan JS, Duncan EK, Schofield G. Accuracy of body mass index (BMI) thresholds for predicting excess body fat in girls from five ethnicities. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2009;18:404–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zimmermann MB, Gübeli C, Püntener C, et al. Detection of overweight and obesity in a national sample of 6-12-y-old Swiss children: accuracy and validity of reference values for body mass index from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the International Obesity Task Force. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;79:838–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Taylor RW, Falorni A, Jones IE, et al. Identifying adolescents with high percentage body fat: a comparison of BMI cutoffs using age and stage of pubertal development compared with BMI cutoffs using age alone. Eur J Clin Nutr 2003;57:764–9. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nihiser AJ, Lee SM, Wechsler H, et al. BMI measurement in schools. Pediatrics 2009;124(Suppl 1):S89–S97. 10.1542/peds.2008-3586L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Niven AG, Fawkner SG, Knowles AM, et al. Maturational differences in physical self- perceptions and the relationship with physical activity in early adolescent girls. Pediatr Exerc Sci 2007;19:472–80. 10.1123/pes.19.4.472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kaltiala-Heino R, Marttunen M, Rantanen P, et al. Early puberty is associated with mental health problems in middle adolescence. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:1055–64. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00480-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Laitinen-Krispijn S, Van der Ende J, Hazebroek-Kampschreur AA, et al. Pubertal maturation and the development of behavioural and emotional problems in early adolescence. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999;99:16–25. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb05380.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cumming SP, Sherar LB, Hunter Smart JE, et al. Physical activity, physical self-concept, and health-related quality of life of extreme early and late maturing adolescent girls. J Early Adolesc 2012;32:269–92. 10.1177/0272431610393250 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.