Abstract

Objectives

Conceptual clarity on physician volunteer engagement is lacking in the medical literature. The aim of this study was to present a conceptual framework to describe the elements which influence physician volunteer engagement and to explore volunteer engagement within a national educational programme.

Setting

The context for this study was the Acute Critical Events Simulation (ACES) programme in Canada, which has successfully evolved into a national educational programme, driven by physician volunteers. From 2010 to 2014, the programme recruited 73 volunteer healthcare professionals who contributed to the creation of educational materials and/or served as instructors.

Method

A conceptual framework was constructed based on an extensive literature review and expert consultation. Secondary qualitative analysis was undertaken on 15 semistructured interviews conducted from 2012 to 2013 with programme directors and healthcare professionals across Canada. An additional 15 interviews were conducted in 2015 with physician volunteers to achieve thematic saturation. Data were analysed iteratively and inductive coding techniques applied.

Results

From the physician volunteer data, 11 themes emerged. The most prominent themes included volunteer recruitment, retention, exchange, recognition, educator network and quasi-volunteerism. Captured within these interrelated themes were the framework elements, including the synergistic effects of emotional, cognitive and reciprocal engagement. Behavioural engagement was driven by these factors along with a cue to action, which led to contributions to the ACES programme.

Conclusion

This investigation provides a preliminary framework and supportive evidence towards understanding the complex construct of physician volunteer engagement. The need for this research is particularly important in present day, where growing fiscal constraints create challenges for medical education to do more with less.

Keywords: volunteer, engagement, qualitative research, medical educatical, critical care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First study to synthesise key elements of physician volunteer engagement into a conceptual framework.

Covers an underinvestigated issue and draws on a wider theoretical background.

Qualitative data obtained provides new insights into physician volunteer engagement, which may offer practical ideas to improve volunteer engagement strategies.

Our findings were obtained in one country, within one national programme.

Explored volunteer engagement in a highly engaged group of physicians, study was not able to explore disengagement.

Introduction

Physician volunteers are essential to healthcare delivery and medical education.1 Despite the growing need to optimise volunteer physician engagement, there is a paucity of data on how to improve and maintain engagement. Volunteerism can be defined as any altruistic act, which is undertaken without financial gain while engagement has been defined as being ‘actively committed’ or ‘to involve oneself or become occupied; to participate'.2 3

Physicians appear to highly value their role as volunteers. In a US study by Gruen et al, 95% of physicians surveyed rated community participation as important.4 Yet, in a national survey of 319 physicians, only 39% participated in volunteer activities.5 Therefore, there appears to be a wide gap between the perceived importance of volunteering and its translation into action or engagement. Such studies illustrate the need to better understand the determinants of physician volunteer engagement and the ways in which it can be optimised.

Most of the medical literature on engagement is centred on the patient and behaviours that promote health. A few isolated studies focusing on physician engagement were identified but there is currently no accepted model describing the multifaceted dimensions of physician volunteer engagement.6–10 We can draw from the social science literature in order to define and examine the various components of engagement.

The concept of engagement, specifically, school engagement has been synthesised in a review by Fredricks et al.11 They present engagement as a multifaceted construct including three dynamically interrelated components: behavioural, emotional and cognitive engagement. Behavioural engagement is related specifically to the on task behaviour. Emotional engagement is related to the value of the tasks as determined by the individual. Value is further divided into four components: ‘interest (enjoyment of the task), attainment value (importance of doing well on the task for confirming aspects of one’s self-schema), utility value (importance of the task for future goals), and cost (negative aspects of engaging in the task)'.11 Cognitive engagement refers to an individual’s motivational goals and self-regulated learning. This concept can be further described as a psychological investment in learning, understanding and mastering knowledge or skills with a ‘desire to go beyond the requirements, and a preference for challenge'.11

In this study, we sought to develop a conceptual framework to describe and explore the components and theoretical underpinnings of physician volunteer engagement. We began our investigation with a secondary analysis of a comprehensive needs assessment in a quality improvement initiative aimed at the overall enhancement of the Acute Critical Events Simulation (ACES) programme. Later, we extended this initial work by obtaining additional data to provide evidence towards understanding the complex construct of physician volunteer engagement.

Context

The ACES programme is a national educational programme aimed at improving the proficiency of individuals and teams involved in the early management of critically ill patients. Nurses, respiratory therapists and physicians who are the first to respond to a patient in crisis come from various disciplines and practice in diverse milieus. Their experience managing acutely ill patients is often very limited given the low incidence of critical illness. Yet, clinical studies indicate that early recognition and management are most effective in lowering both morbidity and mortality. Randomised controlled trials and guidelines emphasise the importance of the 'golden hour' in patients with conditions such as myocardial infarction, stroke and sepsis.12–17 The ACES programme includes various simulation modalities delivered online or face to face as well as books and didactic material. It also includes instructor certification courses. Most of the educational materials have been customised to meet the needs of different groups of learners.

This programme was initially developed from the vision and efforts of a small collective of Canadian critical care physicians who volunteered their time and expertise. It has successfully evolved into a national educational programme, has been acquired by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada and continues to advance and grow. Volunteers remain fundamental to the ACES programme. They create materials, organise courses, teach and conduct research. From 2010 to 2014, the programme recruited a total of 73 volunteers, 69 of whom were physicians. The need for volunteers is increasing due to greater demand, addition of new forms of simulation, growth of online curricula and anticipated movement to a competency-based programme.

Method

A conceptual framework was constructed; secondary analysis of the ACES quality improvement initiative data was performed; additional interviews were conducted; qualitative data collection was performed and analysed iteratively.

Conceptual framework

A conceptual framework is meant to explain the key factors, constructs or variables, and their presumed relationships to be studied.18 19 An extensive literature review along with expert consultation informed the development of the framework. We opted for a more prestructured qualitative research design as we wanted to bound the study within a set of engagement variables, yet at the same time we needed to maintain enough flexibility to allow for emergent findings so as to better understand the construct of physician engagement. We adapted a student engagement conceptual framework.11 We found Fredericks et al’s theory of engagement to be useful in our medical context. In further modifying the conceptual framework, we used the ‘bins approach’, whereby the framework is mostly a visual catalogue of roles to be studied (eg, physician leaders and physicians), and within each role, how the variables of engagement influence their actions.19 A multidisciplinary panel of experts iteratively collaborated on the modifications to the conceptual framework included critical care physicians and leaders, administrators, system-level policymakers and a sociologist.

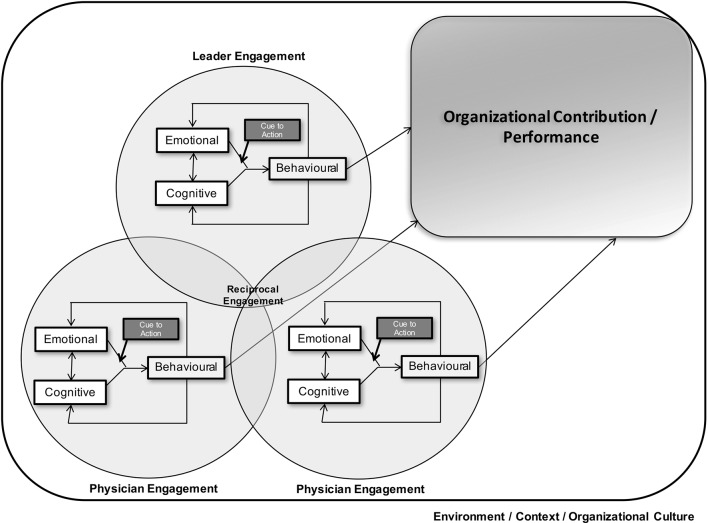

We developed the model shown in figure 1 to explore volunteer physician engagement in a comprehensive manner. For our study, the physician behaviour of participation as a volunteer is the desired outcome. All other elements which contribute and lead to this behaviour are under investigation. In this figure, we have shown two physicians and one leader for simplicity. In reality, there may be many leaders and physicians. We define a leader as an individual within the group who influences others towards a mutual purpose or common goal.20 We define an individual’s engagement as a multidimensional construct including emotional and cognitive engagement which ultimately can lead to behavioural engagement, with tasks directed towards contributing to organisational development and/or a specific domain, such as education, quality and safety, and so on.11

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

An individual’s overall engagement is impacted by their demographic and psychosocial characteristics. The emotional and cognitive components drive behaviour. The bidirectional arrows between these components indicate that the presence and/or development of one component may impact the other. The behaviour itself may further promote the emotional and cognitive components and enhance volunteer behaviours (indicated by the arrow back to the emotional and cognitive components). In addition, the behaviour requires a ‘cue to action’ or trigger (which can be either intrinsic or extrinsic to the individual). A simplistic example of an extrinsic ‘cue to action’ may involve the director of the programme contacting a volunteer to participate.

Individual volunteers have the potential to impact each other and synergistically enhance one another’s engagement. We have termed this variable ‘reciprocal engagement'. This is akin to mutual engagement involving individual actions/attributes and the actions/attributes of others.21 This relationship and enhanced engagement potential is likely secondary to the impact on the individuals’ emotional, cognitive and behavioural components and/or may provide a trigger leading to the behaviour.

Leaders have their own intrinsic characteristics, emotional and cognitive components which drive the behaviour. Reciprocal engagement may also synergistically increase the engagement of both the leader and individuals.

Ultimately, the behavioural engagement of the individual volunteers can lead to increased organisational performance.22 Sustainability of the volunteers likely depends on these factors being maintained and may fluctuate for an individual over time with periods of greater and lesser engagement, for example, based on the presence or absence of a ‘cue to action’ and also based on changes in organisational culture, leadership and other individuals.

Data collection and analysis

As part of a quality improvement initiative of the ACES programme, interviews were conducted by AL between 2012 and 2013. Participant selection was carried out using maximum variation purposive sampling to identify individuals who would provide a balanced representation.23–25 All participants were initially contacted by email or telephone. Participants included programme directors from different specialties and healthcare professionals from different backgrounds. On analysis of this interview data, the ‘physician as volunteer’ theme was identified. To further explore this finding and achieve thematic saturation, AS and SS performed additional telephone interviews with physician volunteers in 2015.

Semistructured interview guides were designed to follow a broad, predetermined line of inquiry that was flexible and that could evolve as data collection unfolded, permitting exploration of emerging themes. Interview guides were created by an interdisciplinary team of investigators with expertise in medical education, simulation, sociological and qualitative research methods. Interview guides were piloted with a sub group of ACES instructors who were not involved in the research study. None of the interviewers had a relationship with any of the study participants prior to study commencement. Study participants were made aware of the interviewers’ level of training and organisational affiliation(s). Interviews lasted from 45 to 60 min were audiorecorded, and transcribed verbatim (see online, supplementary appendix S1 for interview guides). The interviewers (AS and SS) took ongoing field notes during the data collection process to aid in the analysis phase.

bmjopen-2016-014303supp001.pdf (46.4KB, pdf)

Qualitative data analysis of the comprehensive data set included the application of inductive coding techniques, using thematic content analysis, and NVIVO software for data management.19 23 The research team followed Creswell’s coding process where data are first explored to gain a general sense of the data and then coded. These codes were described and collapsed into themes.23 The analysis team consisted of three researchers (AS, SS and AL) who participated in coding training and meetings to develop the coding tree and codebook. The three researchers (AS, SS and AL) generated codes (from the same interview transcripts) independently. Then, they engaged in consensus discussions. Inter-rater reliability, assessed prior to independent coding, demonstrated a 95.73% agreement and a 0.75 Kappa score which is considered to be substantial agreement.26 The volunteer construct was further explored and coded, through a more focused analytic approach in order to gain an in-depth understanding of volunteer engagement.27 In an iterative process, additional interviews were performed to reach saturation of the subthemes specific to volunteer engagement. To ensure the analysis process, and subsequent themes were appropriate and reflected ACES facilitators/leaders views, members of our research team who worked with the ACES programme (PC and AL) engaged in informal discussions with ACES members so as to vet the findings. This study was granted an official exemption by The Ottawa Hospital Research Ethics Board.

Results

For the larger study (quality improvement initiative of the ACES programme), 15 interviews were performed to gain a broad and comprehensive understanding of the ACES programme, which included programme directors and healthcare professionals across Canada; physicians (n=11), nurses (n=2) and respiratory therapists (n=2) (interview guide 1). An additional 15 interviews of physician volunteers were performed (interview guide 2). Overall, 30 of 33 invited individuals agreed to participate in the semistructured interviews for a response rate of 91%. All physician volunteers who were interviewed were full-time clinicians and members of the ACES faculty, who are called to participate as needed. Participants are displayed in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of interview participants

| Characteristic | n | % |

| Number | 30 | |

| Region* | ||

| Mountain | 7 | 23 |

| Prairies | 3 | 10 |

| Ontario | 14 | 47 |

| Quebec | 2 | 7 |

| Atlantic | 4 | 13 |

| Specialty/discipline** | ||

| Critical care | 23 | 77 |

| Anaesthesia | 7 | 23 |

| Internal medicine | 5 | 17 |

| Surgery | 3 | 10 |

| Family medicine | 3 | 10 |

| Nurses | 2 | 7 |

| Respiratory therapists | 2 | 7 |

| Paediatric critical care | 1 | 3 |

*The regions of Canada have been divided in the following way: mountain includes British Columbia and Alberta; prairies include Saskatchewan and Manitoba; Atlantic includes all Atlantic Provinces.

** Individuals were classified under their current practice specialties. Note that an individual may be practicing in more than one specialty.

To gain an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon of volunteer engagement, the data set was coded and 11 themes were identified and subcoded. Of these themes, six interrelated themes—volunteer recruitment, volunteer retention, volunteer exchange, volunteer recognition, educator network and quasi-volunteerism—were most prominent in our data. A summary of the qualitative findings is presented in box 1. Representative quotes are provided to illustrate each theme.

Box 1. Summary of the qualitative findings.

-

Volunteer recruitment

Word of mouth

Snowball approach

Career stage

-

Volunteer retention

Distributed leadership and career paths

Programme change and evolution/innovation

Comfort zone

Reciprocal engagement

Intrinsic motivation

Learners

Barriers

-

Volunteer exchange

Career opportunities

Keep current

Academic currency

-

Volunteer recognition

Personal recognition

Scholarly/academic work

-

Educator network

Common vision

Duration or participation/loyalty

Affect

-

Quasi-volunteerism

Academic pressure

Curriculum vitae

Volunteer recruitment

Word of mouth

All recruitment was accomplished through word of mouth. That is, the cue to action was uniformly described by volunteers as an informal interaction with another volunteer, usually a leader who would call the volunteers to request their involvement.

I just got a call from him [ACES Director] one day, he introduced himself and talked about this program where a few guys were getting together and trying to do this thing and at that time there were, I don’t know, about 6 or 7 guys and he asked if I wanted to be part of it.

Snowball approach

A snowball approach was described by participants as a means of identifying and recruiting high-quality volunteers. With this approach, leaders would contact volunteers within the group, who in turn would reach out to contacts in their social networks to identify potential new recruits who have the qualities required to contribute to the group.

What I would do is have more than one person get in touch with the person they are trying to recruit. First of all you want to cherry pick the people you want to recruit. It’s just like a draft in sports or something. You want to cherry pick the people you want on your team and once you’ve earmarked certain people and say, ‘this person is not just strong clinically but also has great personal skills, is humble enough to listen to feedback, and to not get offended by it but to work with it'.

Career stage

Participants explored the different career stages of physicians who are recruited to volunteer with the programme and felt that younger physicians are generally easier to recruit.

If it was in the middle part of their [physician] career, they may be on a certain track and it’s difficult to engage them. I think it would be great if we could recruit people at mid-career because they have a bit more experience, a bit more knowledge about how things should work or how things should flow. On the other hand, if you recruit younger people, I think they are more enthusiastic and have completely new ideas and that’s not a bad thing either right? For me, it was great to be involved early on but I was definitely a little shy to come forward with suggestions initially because, yeah, it’s just a very established crowd.

Volunteer retention

Distributed leadership and career paths

The organisation embraces an open culture creating a collaborative environment, which allows for new leaders to be brought in and mentored by long-standing leaders. This relationship enables long-standing leaders to remain involved with the programme while balancing other career demands. In this way, ACES is able to deepen its leadership base by distributing responsibilities to others.

I have decreased in participation, though I still remain section chair, well it is more of a co-chair position because I have a capable colleague who has taken over some of the curriculum development…I don’t see myself in this role for perpetuity and so it’s a good opportunity for people to transition and I think it’s part of the natural transition process. I still remain involved and committed to being part of the National ACES Program, and I still assist locally but I have decreased my involvement. It is more of a career choice and balancing the different aspects of my career that I’ve taken on as well.

Programme change and evolution

The programme’s continual growth, ongoing modifications and innovative nature were described by volunteers as being very intellectually stimulating. This cognitive component was described by many participants as a major contributor to their initial and ongoing commitment and involvement with the programme.

I think the fact that we change and we grow is very important. If it was just the same program every year it will eventually become stagnant and people will lose interest.

Comfort zone

Comfort zone is indicative of a behavioural state within which a person operates in an ‘anxiety neutral’ condition. The objective is to push or lead individuals beyond their comfort zone until comfort is achieved, which enables a consistent high-level performance. During their interviews, volunteers were asked if they felt they were drawn to more challenging tasks. One physician put it like this,

So, why is it that you have to get out of your comfort zone? Why do you have to embark on a new mission or path that is quite challenging, one that there is no guarantee that it is going to work? I actually enjoy the process. I love working with others, I love creating things, and I love taking something that’s just in the idea stage, and you know transforming it into something that’s actually real.

Reciprocal engagement

Participants identified that a volunteer can enhance another volunteer’s engagement and this process is cyclical. Participants further identified that interacting and connecting with students further enhanced their overall engagement.

It’s amazing to go [to the ACES course] and see all these people giving their time because they love to teach and want people to do better. They are genuinely interested in the well-being of these fellows to be better doctors and it’s catching you can’t help but get your love of education back.

Intrinsic motivation

We use the psychological lens of motivation to underpin our understanding of intrinsic motivation. There is a fundamental distinction between actions that are self-determined and those that are controlled. The former, which reflects an individual’s personal attributes and internal (intrinsic) motivation, was identified as contributing to the volunteers’ participation in the programme. The answer might be as simple as, ‘I was built like that. This is who I am’. In fact, many described a strong internal drive to participate, hoping that they ‘would be called’ to action more frequently to perform tasks for the organisation. Interestingly, participants spoke of a willingness to give more of their time, noting that financial incentives were of low to absent value in their activities with the ACES programme. One participant described his experience like sitting on the bench waiting for the coach to call:

I guess one of the biggest things as a volunteer, you’re always somebody who is kind of on the bench and the coach may call you into play at any time. And, you kind of wonder if you’re gonna get called off the bench to play…I love it and I love being invited back each time.

Learners

Fellows, often referred to as high-level learners by the volunteers, served as catalysts for both emotional and cognitive engagement in the ACES programme. Some volunteers expressed the gratification they felt in teaching the next generation of intensivists, while others expressed the fulfilment in teaching such advanced learners:

It’s gratifying to feel like you are teaching the next generation of docs as they come through and they are high level learners who are about to become intensivists themselves so they are keen to learn.

Barriers

The main barriers to retention included career trajectory (as described above) and individual time constraints, including both personal and professional demands. As volunteer physicians continue along their career, they may choose different pursuits (eg, research) and then do not have time to remain an ACES volunteer.

Volunteer exchange

Career opportunities

We use volunteer exchange from the theory of social exchange which posits that social behaviour is the result of an exchange process.28Volunteers noted that aside from receiving continuing medical education credit for their volunteerism, their participation in the ACES course provided additional benefits for their careers:

Being an ACES volunteer means that this is Royal College (RC) accredited and I think that speaks a lot to the quality of the course but also for an academic person who might have additional interests in teaching more RC courses, this work stands out quite a bit.

Keeping current

Volunteering in the ACES course gave individuals the benefit of staying current at a national level. This knowledge acquisition and networking opportunity both enhanced an individual’s practice personally and professionally.

It’s a good group of people, so it’s always a good time and it’s a way to keep your finger on the pulse of how things are going nationally and talk to people about what is going on in other centres.

Academic currency

The benefit of volunteering in the course was viewed by many individuals in terms of professional value whereby the experience counts towards promotion and tenure at an academic institution.

It’s always something you can list in your own CV within our medical practice plan. Teaching at these things counts in terms of academic points, you can put down each year that you taught this and that has academic currency.

Contributing to another’s programme was further described as a method of building up ones currency in that there was an expectation that, in turn, volunteer peers would ‘pay back’ the favour at a later date.

Volunteer recognition

Personal recognition

Attainment value, such that involvement of volunteers with the programme confirmed aspects of one’s self ‘this is who I am’, was further described in the form of personal recognition of their role as educators, by colleagues at other universities, across the country.

Scholarly/academic work

Volunteers want their work in the ACES programme to be recognised as scholarly contributions. The ACES programme leadership sends letters of recognition to volunteers’ department heads; however, participants described difficulty in getting universities to recognise ACES contributions as scholarly.

I think ACES does a very good job at recognizing our contributions. They catalogue and document the contributions on an annual basis, they send letters to our Department heads so they recognize us. I think the greater impact is to have an opportunity to enhance this recognition as scholarly work, to meet the criteria for standard publication in a peer review outlet.

Educator network

Common vision

Personal perceptions of the importance of the volunteer work coupled with a common vision, passion for education and collaborative spirit were described by participants. At the highest level, the penultimate goal of potentially impacting patient care as an outcome was described by both leaders and volunteers. The potential effect on patient care (utility value) was further described as being achievable through the volunteers’ abilities and opportunity to help the residents acquire the knowledge and skills required to excel in the clinical setting.

I think we share a common vision, a common passion. We all believe in education, I think that through collaboration we can do greater things than we could independently. There’s a sense of satisfaction of doing it.

Duration of participation/loyalty

Participants expressed feelings of loyalty to other volunteers in the network, especially those who have been involved for a longer duration.

I think there’s always going to be some loyalty because you’ve invested a great period of time. Also, it is one of the few tangible creations that you’ve helped develop and so you feel part of it.

Affect

Deep and meaningful emotional components connecting volunteers to the ACES programme educator network were identified. Being part of a network elicited strong positive emotions. The enjoyment experienced by volunteers was strongly linked to interactions with other like-minded educators. The face-to-face interaction of volunteers on an annual basis at varying Canadian locations was described as an essential part of the organisation.

When we meet it’s like a bunch of friends getting together…everybody is full of energy when you arrive…everybody is happy, people are smiling…and you are basically like a big family…It’s mostly, I think, emotional at that stage.

Quasi-volunteerism

Academic pressure

The term quasi-volunteer is reflected in both extrinsic and intrinsic motivations to extend effort into a relationship and/or activity. That is, volunteers in academic teaching hospitals described ‘academic pressures’, especially for younger doctors, where they felt they were required to meet specific academic expectations:

The premise that its volunteerism is somewhat true. Nobody has a gun to my head saying I have to do it but we all have to do something, academically. So, I guess it’s quasi-volunteerism. Like if I wasn’t doing this I would have to, especially us younger docs, like we are all on some degree of academic pressure to keep the university happy. So, if I were not doing this teaching, I’d be doing something else, you know?

Curriculum vitae

Intrinsically, participant volunteers used the teaching exposure at the national ACES course to grow their own curriculum vitae (CVs). As such, for some, the volunteer activities were not performed for purely altruistic reasons, but also for professional gain:

It’s good to have in your career, you have to have exposure to teaching outside of your center so this gives me the opportunity to fulfill that, so it’s not all altruistic. it’s something that I do need to do for my curriculum vitae.

Discussion

The productivity, success and sustainability of the ACES organisation depend on the recruitment, retention and recognition of volunteers in a collaborative network. As shown in our conceptual framework, the synergistic effects of the individual’s emotional and cognitive engagement along with reciprocal engagement within the environmental context and culture of the organisation, followed by a cue to action, lead to behavioural engagement in volunteer activities and contributions to the ACES programme. Wherein the conceptual framework has underpinned and bounded the study, as described by Fredricks et al (2004), we have also found that it is difficult to specifically separate out the behavioural, emotional and cognitive elements of engagement. We feel that our findings call for richer characterisations of how physicians behave, feel and think.

Overall, our study yields several key findings that contribute to our understanding of what motivates physicians to volunteer, and perhaps more importantly what sustains their volunteerism. With respect to recruitment, we found that word-of-mouth recruitment was the primary behavioural vehicle to engage new members. In the marketing literature, word of mouth is defined as an interpersonal communication, independent of the organisation’s marketing activities, about an organisation or its products.29 Our findings support this literature in that word of mouth is a dyadic communication between a source and a recipient.30 This implies that the occurrence of word of mouth is determined by characteristics of the recipient, the characteristics of the source and their mutual relationship.31 32

Word-of-mouth communication was found to be particularly effective behavioural component in securing buy-in from new members when done early in the recruitment phase. That is, a phone call from one of the long-standing members of ACES early in the selection phase was conducted so as to gain an initial impression of potential new members. This also tended to have the effect in attracting the potential recruit. This supports earlier research that demonstrated receiving positive information through word of mouth early in the recruitment process is positively related to perceived organisational attractiveness and actual recruitment.33 Within the business literature, this phenomenon is called the accessibility-diagnosticity model. The model suggests that information provided through word of mouth affects potential recruits’ early evaluations of the organisation because of its accessibility in memory and its feedback potential.34 35 That is, if a physician receives positive word-of-mouth information on a given programme or organisation, they are more likely to think favourably when asked at a later date to perform a volunteer activity. This finding has clear practical implications for practice in that organisations should try to stimulate positive word of mouth early in the recruitment process because of its positive impact on potential recruits’ attraction to an organisation and subsequent retention.

Long-standing ACES volunteers take careful measures to select, and subsequently recruit new members. In turn, this recruitment effort has a significant impact on long-term retention. The majority of physicians recruited become committed to the ACES programme and have long-term sustainability as volunteers. We have found that a key to this commitment and sustainability lies in the strength of the social networks among volunteer physicians. Research on teams in which dyads are found within larger groups of people (eg, ACES volunteer physicians within the larger medical community) suggests that people are likely to collaborate with others who possess qualities and skills, and know-how that are complementary to their own and relevant to reaching a particular objective.36 Interestingly, we found that many of the new recruits were already well known to at least several of the ACES physician volunteers, and thus were already in their educator network. This supports the notion that people are inclined to create relationships with friends of their friends (or the business associates of their business associates). The effect of sharing mutual acquaintances on attachment appears to be additive in that each additional mutual acquaintance shared by an unconnected dyad (relationship) additionally increased the likelihood that they will become acquainted.37 Perhaps the reason for the excellent retention and deep commitment of ACES physician volunteers is explained by the structure of the ACES social networks which comprises many third-party connections. Research states that ties connecting people who share several common third party connections are more likely to withstand the test of time.38 39 As related to our conceptual framework, we understand that physician volunteers exercise both emotional (intrinsic commitment and loyalty) and cognitive (intellectual challenge and constant change/growth) engagement that directly relate to the retention of volunteers.40 41

Personal satisfaction was an overarching finding that mapped directly to the emotional and cognitive elements of engagement within the conceptual framework. Our study has shown that financial incentives are of low to absent value to physician volunteer engagement in all activities within the ACES programme. The emotional and cognitive rewards coupled with reciprocal engagement were key elements. In addition, the organisational culture provided the basis for successful engagement. The need to enhance scholarly recognition was identified. Literature supports that the internal motivation is a strong driver of volunteer teacher participation.9 The high value placed on personal satisfaction appears to be consistent across a variety of contexts. This domain of personal satisfaction can be further broken down into the emotional, cognitive and reciprocal form of engagement and mapped to our conceptual framework. In particular, physicians felt a strong sense of cognitive engagement with regard to being ‘pushed’ out of their comfort zone so as to reach a new and expanded state of performance.42 43

We found workload and increased external demands to be a threat to physician volunteer activities. Yet, in the ACES group we identified healthcare professionals who have remained engaged despite considerable external demands. In fact, most volunteers interviewed in this programme would contribute further if called upon. The high level of engagement of these individuals is complex and involves many elements of the conceptual framework. In some circumstances, when other demands increased, volunteers modified their role and mentored new leaders, allowing for ongoing engagement. Moving away from traditional ‘individual’ leadership theories, team leadership theory includes the concept of team leadership capacity, which includes the entire range of the team’s leadership.44 It appears that the ACES organisational structure has capitalised on this distributed shared leadership approach to ensure sustainable and diversity of available leaders.

Limitations

There are several limitations to our study. It was a cross-sectional study performed in a single context of highly engaged healthcare professionals, most of whom were located at academic teaching hospitals. The nature of engagement within the organisation may be context specific. Further studies are required to determine the transferability our findings to other contexts. In our study, we sought perspectives from volunteers performing various tasks. However, given the sample size it is not possible to determine if the underlying components of engagement change with variation in the roles. Furthermore, we did not examine the time spent volunteering (eg, hours/weeks per year) nor did we seek out individuals who may have volunteered but later completely withdrew. We will ensure to capture this data in our future work. Finally, when the volunteer role includes teaching, we identified that the reciprocal engagement between the student and teacher adds to the overall engagement of the volunteer. This component was not in our conceptual framework and could be added in future investigations where the volunteer role includes teaching.

Future research

The presumption that engagement is malleable is an exciting prospect.45 46 A cohesive framework is required to facilitate understanding of the complex construct of volunteer physician engagement and this framework can be used in the development of multifaceted approaches to enhance volunteer physician engagement. For example, an intervention may include enhancing reciprocal engagement through collaborative meetings and enhancing interpersonal relationships; emotional engagement by connecting with individuals on a deeper level with respect to the meaning and potential outcomes of their work; cognitive engagement by including intellectually challenging tasks, and recognition of the volunteers work through faculty appointment, newsletters among their peers, awards and scholarly acknowledgement. Further research is also required to determine how we measure engagement. The conceptual framework presented in this paper may aid in the design of measurement tools. The strategies and tools may vary depending on type of volunteer activity and setting. Furthermore, research is required to explore the construct of disengagement, to determine if different professional ‘identities', such as nurses, respiratory therapists, administrators, have different facilitators and inhibitors to engagement. Future studies may also explore if volunteer participation impacts an individuals’ clinical practice or career path.

Conclusion

Volunteer physicians are essential to the growth and sustainability of the ACES programme. This organisation has demonstrated great success with engaging highly effective volunteers. Our conceptual framework and qualitative findings provide a preliminary framework as an important initial step in understanding the complex construct of volunteer physician engagement. This study will guide us in our development of a multifaceted intervention, aligned with the conceptual framework, to enhance volunteer physician engagement within the organisation. Finally, given the current economic climate, providing compensation to physicians for additional education-related activities may not be financially feasible or sustainable so alternative approaches must be explored to engage volunteer physicians.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the healthcare professionals who participated in this study and shared their experiences and opinions with the research team.

Footnotes

Contributors: AJS and SS had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. AJS, SS, AL, KD, SB, PC: study concept and design; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. AJS, SS, AL, KD: acquisition of data. AJS, SS, AL, PC: analysis and interpretation of data. AJS, SS: drafting of the manuscript. AL. SB, PC: obtained funding. AL, KD: administrative, technical or material support. AJS, SS, PC: study supervision. All authors have approved the final version of this manuscript.

Funding: Resources and secretariat support for this project were provided by the Royal College.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: No patient involvement in this study.

Ethics approval: This study was granted an official exemption by the Chair of The Ottawa Hospital Research Ethics Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Taitz JM, Lee TH, Sequist TD. A framework for engaging physicians in quality and safety. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:722–8. 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Volunteering. Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, 2015. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Volunteering (accessed 1 oct 2014).

- 3. The American Heritage College Dictionary . (4th ed) Houghton Mifflin Company, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gruen RL, Campbell EG, Blumenthal D. Public roles of US physicians: community participation, political involvement, and collective advocacy. JAMA 2006;296:2467–75. 10.1001/jama.296.20.2467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grande D, Armstrong K. Community volunteerism of US physicians. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:1987–91. 10.1007/s11606-008-0811-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Milliken AD. Physician engagement: a necessary but reciprocal process. CMAJ 2014;186:244–5. 10.1503/cmaj.131178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Snell AJ, Briscoe D, Dickson G. From the inside out: the engagement of physicians as leaders in health care settings. Qual Health Res 2011;21:952–67. 10.1177/1049732311399780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mazurenko O, Hearld LR. Environmental factors associated with physician's engagement in communication activities. Health Care Manage Rev 2015;40:1. 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kumar A, Kallen DJ, Mathew T. Volunteer faculty: what rewards or incentives do they prefer? Teach Learn Med 2002;14:119–24. 10.1207/S15328015TLM1402_09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vath BE, Schneeweiss R, Scott CS. Volunteer physician faculty and the changing face of medicine. West J Med 2001;174:242–6. 10.1136/ewjm.174.4.242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fredricks JA, Blumenfeld PC, Paris AH. School engagement: potential of the Concept, State of the evidence. Rev Educ Res 2004;74:59–109. 10.3102/00346543074001059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-Elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice guidelines (Writing Committee to revise the 2002 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation myocardial infarction) developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:e1–e157. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Adams HP, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, et al. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the american Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and intervention council, and the atherosclerotic peripheral vascular disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working groups: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke 2007;38:1655–711. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.181486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med 2008;36:296–327. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000298158.12101.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe Sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1368–77. 10.1056/NEJMoa010307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rivers EP, Coba V, Whitmill M. Early goal-directed therapy in severe Sepsis and septic shock: a contemporary review of the literature. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2008;21:128–40. 10.1097/ACO.0b013e3282f4db7a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016;315:801–10. 10.1001/jama.2016.0287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research & evaluation methods. SAGE Publications, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J. Qualitative data analysis. SAGE Publications, incorporated, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Swanwick T, Understanding medical education. Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wenger E. Communities of Practice. Cambridge University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Preskill H, Torres RT. Evaluative Inquiry for Learning in Organizations. Thousand Oaks,CA: SAGE, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Creswell JW. Educational Research: planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. Boston, MA: Pearson, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Creswell JW, Hanson WE, Plano VLC, et al. Qualitative research designs selection and implementation. The Counseling Psychologist 2007;35:236–64. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hennink M, Hutter I, Bailey A. Qualitative research methods. SAGE, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med 2005;37:360–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cama R. Evidence-Based Healthcare Design. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Emerson RM. Toward a theory of value in social exchange. Social exchange theory 1987;11:46. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bone PF. Word-of-mouth effects on short-term and long-term product judgments. J Bus Res 1995;32:213–23. 10.1016/0148-2963(94)00047-I [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gilly MC, Graham JL, Wolfinbarger MF, et al. A Dyadic Study of Interpersonal Information search. J Acad Mark Sci 1998;26:83–100. 10.1177/0092070398262001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bansal HS, Voyer PA. Word-of-Mouth Processes within a Services Purchase Decision Context. Journal of Service Research 2000;3:166–77. 10.1177/109467050032005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lau GT, Ng S. Individual and situational factors influencing negative Word-of-Mouth Behaviour. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences / Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l'Administration 2001;18:163–78. 10.1111/j.1936-4490.2001.tb00253.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Van Hoye G, Lievens F. Tapping the grapevine: a closer look at word-of-mouth as a recruitment source. J Appl Psychol 2009;94:341–52. 10.1037/a0014066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Feldman JM, Lynch JG. Self-generated validity and other effects of measurement on belief, attitude, intention, and behavior. J Appl Psychol 1988;73:421–35. 10.1037/0021-9010.73.3.421 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Herr PM, Kardes FR, Kim J. Effects of Word-of-Mouth and Product-Attribute Information on Persuasion: an Accessibility-Diagnosticity Perspective. J Consum Res 1991;17:454. 10.1086/208570 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rivera MT, Soderstrom SB, Uzzi B. Dynamics of Dyads in Social Networks: assortative, Relational, and Proximity Mechanisms. Annu Rev Sociol 2010;36:91–115. 10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134743 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Newman ME. Clustering and preferential attachment in growing networks. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys 2001;64(2 Pt 2):025102. 10.1103/PhysRevE.64.025102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Burt RS. Decay functions. Social Networks 2000;22:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Martin JL, Yeung K-T. Persistence of close personal ties over a 12-year period. Soc Networks 2006;28:331–62. 10.1016/j.socnet.2005.07.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Deci. E, Ryan M. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York, NY: Plenum, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Deci EL, Ryan RM. The support of autonomy and the control of behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol 1987;53:1024–37. 10.1037/0022-3514.53.6.1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. White A. Continuous Quality improvement. London, UK: Piatkus Books, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yerkes R, Dodson J. The dancing mouse: a study in animal behavior. Journal of Comparative Neurology & Psychology 1907;18:459–82. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Northouse PG. Leadership. SAGE Publications, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Coates H. The value of student engagement for higher education quality assurance. Quality in Higher Education 2005;11:25–36. 10.1080/13538320500074915 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Parsons J, Taylor L. Student engagement: What do we know and what should we do? 2011. https://education.alberta.ca/media/6459431/student_engagement_literature_review_2011 (accessed 10 oct 2014).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014303supp001.pdf (46.4KB, pdf)