Abstract

Introduction

Obesity and physical inactivity are major societal challenges and significant contributors to the global burden of disease and healthcare costs. Information and communication technologies are increasingly being used in interventions to promote behaviour change in diet and physical activity. In particular, social networking platforms seem promising for the delivery of weight control interventions.

We intend to pilot test an intervention involving the use of a social networking mobile application and tracking devices (Fitbit Flex 2 and Fitbit Aria scale) to promote the social comparison of weight and physical activity, in order to evaluate whether mechanisms of social influence lead to changes in those outcomes over the course of the study.

Methods and analysis

Mixed-methods study involving semi-structured interviews and a pre–post quasi-experimental pilot with one arm, where healthy participants in different body mass index (BMI) categories, aged between 19 and 35 years old, will be subjected to a social networking intervention over a 6-month period. The primary outcome is the average difference in weight before and after the intervention. Secondary outcomes include BMI, number of steps per day, engagement with the intervention, social support and system usability. Semi-structured interviews will assess participants’ expectations and perceptions regarding the intervention.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval was granted by Macquarie University’s Human Research Ethics Committee for Medical Sciences on 3 November 2016 (ethics reference number 5201600716).

The social network will be moderated by a researcher with clinical expertise, who will monitor and respond to concerns raised by participants. Monitoring will involve daily observation of measures collected by the fitness tracker and the wireless scale, as well as continuous supervision of forum interactions and posts. Additionally, a protocol is in place to monitor for participant misbehaviour and direct participants-in-need to appropriate sources of help.

Keywords: Obesity [Mesh], Exercise [Mesh], Fitness Trackers [Mesh], Social media [Mesh]

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first experimental study to evaluate mechanisms of social comparison and weight change in users from different body mass index categories, using a mobile social networking application.

The use of wireless tracking devices to assess weight and physical activity obviates the need to use less reliable self-reported measures.

Qualitative methods will help gather input to optimise the intervention.

Limitations include the quasi-experimental nature of the study: the pre–post design without randomisation impacts the interpretation of the results, as multiple confounders may be at play.

Introduction

Obesity is a major societal challenge and a significant contributor to the global burden of disease and healthcare costs.1–3 Effective weight loss interventions have been identified,4 but weight regain is common in the long term.5 6 Finding effective ways to promote and sustain weight loss is essential in controlling the obesity epidemic and its health consequences.

While obesity has complex causation, it is clear that diet and physical activity patterns play a major role in weight change.5 7 These lifestyle behaviours are, in turn, strongly shaped by social factors.8–12 For instance, studies have shown that an individual’s likelihood of becoming obese is highly influenced by whether or not someone in their social network becomes obese, suggesting that the norms and behaviours that lead to obesity may indeed propagate in social networks.13 This suggests the possibility that social networks may similarly be used to spread healthy behaviours and curb the obesity epidemic.14

Social networks are a particularly interesting system for the delivery of weight management interventions.15 Social networks are webs of social relationships surrounding individuals16 that enable several social functions: social influence, social control, social comparison, companionship and social support.17 An interesting aspect in social networks is the tendency of people to associate and bond with alike individuals, such as people who share similar interests, beliefs and behaviours (ie, homophily).18 Additionally, tie strength is a measure of the importance of the interactions between two individuals in a social network. Strong ties are a major source of social support, but weaker ties are also crucial, as they seem to be better at transmitting new information and behaviours (a phenomenon known as the ‘strength of weak ties’).16

The influence of dissimilar weak ties in weight management remains largely unknown. Until now, most experimental studies in weight management involve samples of relatively homogeneous participants (eg, overweight and/or obese). Furthermore, the effect of different social comparison strategies on motivation to lose weight in heterogeneous groups is still relatively unexplored. Although social comparison has been associated with greater weight loss in weight management interventions,19 it remains a question whether comparisons with higher or lower standards may have different effects on weight. Interestingly, in physical activity studies, social comparison to the level of median performance (50th percentile) has been shown to be more effective in increasing physical activity than anchoring feedback to a higher level such as the top quartile (75th percentile).20 A potentially useful way to explore these mechanisms is through the use of online social networks.

Online social networks (OSNs), which are now ubiquitous in our lives, enable individuals to create and display a personal profile to other users, as well as to build a network of connections.21 Moreover, OSNs are increasingly being used for research and public health purposes. Their advantages include the possibility to inexpensively disseminate health interventions and the ability to create and modify networks specifically for research purposes, a common strategy in network interventions.15

Given the scale of the obesity ‘epidemic’ and the need for effective interventions that are simple, affordable and scalable, it is no surprise that social network interventions are emerging as a potentially powerful approach to tackle this health problem.22 To date, several experiments have been conducted using OSNs to promote weight loss, physical activity and adherence to a healthy diet, with encouraging results.23–26 Nevertheless, research is still needed in order to ascertain how interventions involving OSNs may be optimised to increase their effectiveness.27 28

Finally, the growing availability of smartphones, mobile applications (apps) and wireless trackers, such as wearable activity monitors and connected weight scales, is giving rise to new opportunities in the study of weight management and obesity.20 29 30 They have the power to reach and be used by individuals at any time in their natural environments, facilitating ongoing real-time tracking, and they also enable the reliable collection of physical activity and anthropometric measures (eg, weight), thus obviating the need to use less reliable self-reports of these outcomes in research studies.31 32

This study aims to pilot test a social networking mobile application connected to wireless tracking devices, in order to evaluate mechanisms of social comparison in users from different body mass index (BMI) categories, as well as to assess effects on BMI, weight and physical activity levels, during 6 months. Qualitative methods will also be used to test the feasibility and acceptance or the intervention, as well to gather input to optimise it, in view of future evaluation in a randomised controlled trial.

Methods and analysis

Study design

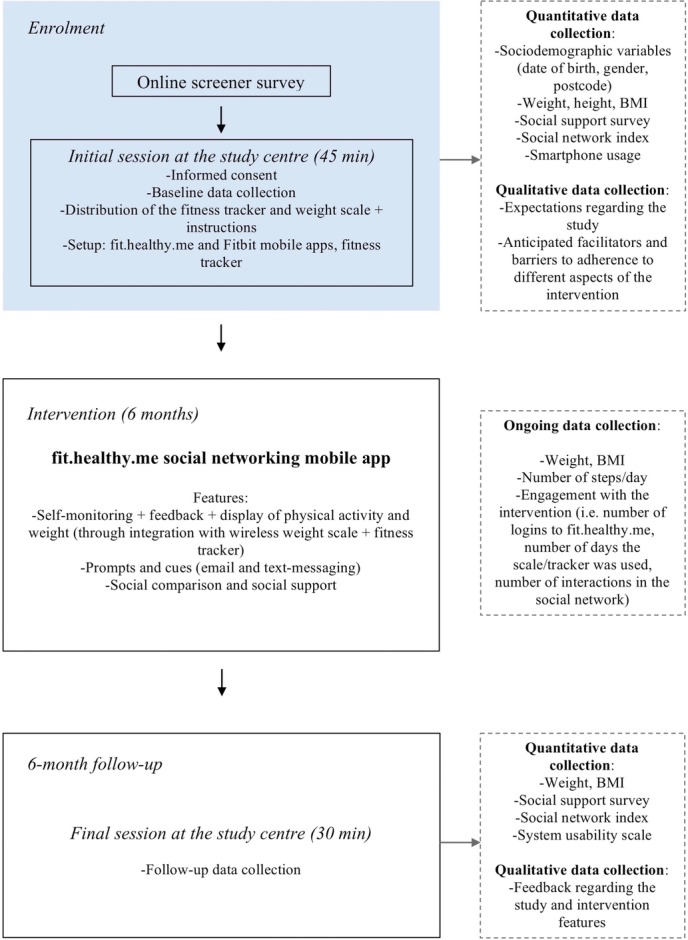

We will conduct a mixed-methods study involving semi-structured interviews and a pre–post quasi-experimental pilot with one arm, where participants will be subjected to a social networking mobile app intervention over a 6-month period, starting in April 2017 (figure 1). The study design was chosen to enable efficient testing of the feasibility and acceptance of the intervention, as well to gather input to optimise it and increase its effectiveness. Preliminary exploratory data gathered from this pilot study will also be useful in guiding a future randomised controlled trial. The design of this study followed the ‘CONSORT 2010 statement—extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials’.33

Figure 1.

Study flowchart.

Study sample and recruitment

Eligible study participants are consenting healthy adults who are able to speak, write and read English, aged between 19 and 35 years old, who plan to be living in Sydney for the duration of the study, own a mobile phone (iOS or Android) with Internet access, have Wi-Fi connection at home, are able to use a fitness tracker (Fitbit Flex 2 bracelet) and wireless weight scale (Fitbit Aria scale) for the duration of the study, and agree to have two mobile applications installed on their smartphone (fit.healthy.me and Fitbit). Exclusion criteria include pregnancy or breastfeeding, BMI below 17, prior history of eating disorders or having diabetes or other comorbid conditions that might impact on study participation (eg, severe mental illness, end-stage disease).

Forty participants will be recruited using a purposive sampling technique in order to achieve an equal number of participants for each of the following categories of BMI (kg/m2): 17–20.9, 21–24.9, 25–29.9 and ≥30. These categories do not directly correspond to the WHO’s cut-off points for underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) and obese (≥30 kg/m2)34 and were chosen in order to limit the recruitment of people in the lower limits of BMI, who may be at higher risk of becoming severely underweight. The sample size was pragmatically chosen to enable a comprehensive study of the feasibility of the intervention.

The study will be advertised at Macquarie University. The following strategies will be used sequentially until the desired sample size is achieved: (1) posters and flyers will be distributed on campus during ‘Orientation week’ (ie, the week that marks the beginning of the academic year in Australia) and onwards; (2) advertisements will be circulated on social media, targeting Macquarie University students and staff; and (3) promotional information will be included in the monthly Macquarie University email newsletter. All of the promotional materials will direct potential participants to the study website, where they will be able to read more information about the study and check the eligibility criteria. The study website will also include a link to a Qualtrics survey aimed at assessing eligibility criteria. After completing the survey, participants who meet inclusion criteria will be contacted by the research team to schedule a 45 min session at the study centre.

Intervention

We designed a modular intervention for weight and physical activity monitoring (fit.healthy.me) based on the existing Personal Health Record ‘Healthy.me’. ‘Healthy.me’ is a research platform available in web and mobile app versions (iOS, Android), which facilitates the management of health information, communication with health services and peers, and access to decision support and self-care tools.35 36 Interestingly, its modular development enables the isolation of intervention components in software modules, which can be easily added or removed from the system, and assessed for effectiveness in different combinations. Although the ‘complete’ Healthy.me system consists of several features that facilitate the self-management of health and healthcare, fit.healthy.me is focused only on social networking and tracking of weight, BMI and steps (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Screenshots of the home page and ‘My measures’ module of the fit.healthy.me mobile application.

Several behaviour change techniques were considered in the design of this intervention: self-monitoring and feedback on physical activity, weight and BMI, prompts and cues, social support and social comparison. Prompts and cues (text messages and emails every 2 weeks) were included to remind users to ‘wear’ the fitness tracker during waking hours and to use the scale daily to monitor their weight, as well as to check fit.healthy.me at least every day.

In all interactions in the system, participants may choose to use either a pseudonym or their own name. Furthermore, users are able to interact and provide social support to each other through the use of messaging and the social forum, as well as ‘follow’ particular ‘buddies’ with whom they might identify more closely.

In order to enable the automation of self-monitoring, fit.healthy.me was integrated with two digital devices—the Fitbit Flex 2 fitness tracker (bracelet) and the Fitbit Aria weight scale—which wirelessly sync with fit.healthy.me (via the Fitbit Application Programming Interface (API)). Fitbit Flex 2 uses accelerometer technology to measure acceleration signals which are then converted into common indicators of physical activity (eg, steps) through proprietary algorithms; it has demonstrated good reliability and validity for measuring step count in free-living conditions.32 37 Syncing between the Fitbit mobile application and the paired Fitbit Flex 2 occurs periodically throughout the day when the feature ‘All-day sync’ is turned on. The Fitbit Flex 2 resets to zero at midnight every night; when syncing is not enabled, data are kept on the tracker with minute-to-minute information stored for up to 7 days and daily information stored for up to 30 days. The Fitbit Aria scale syncs automatically after each weigh-in.

Weight, BMI and step count measures are obtained by fit.healthy.me from the Fitbit API every 5 min. The values for weight and BMI retrieved from the Fitbit API correspond to the last time the person used the weighing scale (independent of the day). In contrast, the value for steps is a daily measure (ie, it is reset to zero at midnight every day) and the value retrieved from the API by fit.healthy.me at any given point correspond to the last time the Fitbit Flex 2 bracelet was synced that day.

The social components of the intervention were integrated using a unique social module, which enables users to visualise their step count and weight management efforts in comparison to other users, through the display of those measures in table and graphical formats (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Screenshots displaying the social comparison features in fit.healthy.me.

Mean values for ‘Others’ and ‘Buddies’ are calculated automatically by fit.healthy.me using data retrieved from the Fitbit API. In order to enable an objective comparison of each individual with the remaining participants, averages were calculated excluding measures for the ‘self’.

Another special consideration was the calculation of mean value for steps. Since observations equal to zero pose a particular problem in accelerometer data (eg, they may reflect forgetfulness to wear the tracker or non-syncing rather than inactivity38), we decided to exclude those observations from the calculation of the mean values for ‘Others’ and ‘Buddies’. This exclusion enables participants to compare themselves at any time with a mean value not skewed by ‘zero observations’ from individuals not wearing the tracker or not enabling syncing with the API.

Data collection and analysis

Study outcomes

The primary outcome will be the average difference in weight between 6 months and baseline. Secondary outcomes include BMI, number of steps per day, engagement with the intervention (ie, number of logins to fit.healthy.me, number of days the scale and fitness tracker were used, number of interactions in the social network), social support and system usability.

For the purposes of assessing the baseline and 6-month measures for the steps count outcome, the mean number of steps per day will be compared between the first and last 7 days of the study, from a minimum of 4 valid days.38 A valid day was defined as 10 or more hours of monitor wear37; wear time was defined by subtracting non-wear time from 24 hours, and non-wear was defined as a period of at least 60 consecutive minutes of zero counts, allowing for 1–2 min of counts between 0 and 100.38 39

Qualitative evaluations will occur preintervention and postintervention, with the aim of assessing participants’ perspectives regarding the intervention (eg, usability, feasibility, satisfaction, facilitators and barriers to adherence), as well as to explore potential mechanisms of social comparison and social influence related to this intervention.

Study procedures and data collection

Eligible individuals will be invited to attend an initial 45 min session at the study centre. During this session, participants will be welcomed into the study, then asked to sign and date a consent form, witnessed by the investigator or another person and provided with a copy.

Following this, participants’ sociodemographic variables will be collected, as well as smartphone usage information (eg, type of smartphone used, hours per day spent using the smartphone, comfort with using the technology). Participants will also be asked to fill-in two questionnaires: the social support survey40 and the social network index.41

Participants will then be asked to answer a few questions about their expectations for the study and anticipated facilitators and barriers in regard to several aspects of the intervention (eg, use of a wearable to monitor physical activity, daily use of a wireless scale to monitor weight changes, use of the mobile app to track progress, use of the social components of the mobile app). These same aspects will be evaluated again at the end of the intervention.

Finally, baseline measures will be collected (eg, weight and height). Body weight will be measured to the nearest 0.1 kg in light clothing without shoes using a digital scale (Fitbit Aria scale). Height will be measured to the nearest 0.1 cm at baseline only using a wall-mounted stadiometer. BMI will be calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2).

Both the Fitbit mobile app and fit.healthy.me will be downloaded and installed at this point, and a Fitbit account will be created.

Initially, participants will undergo a 7-day period of baseline assessment where they will not be able to login to fit.healthy.me but will be asked to use the Fitbit Flex 2 every day during waking hours and weigh themselves using the Fitbit Aria scale every day. After this period, participants will be instructed to use both the wireless devices and fit.healthy.me, at least daily. Both devices will be calibrated previously to the initial study session.

At the end of the 45 min session, participants will be given the opportunity to ask any questions related to the study protocol or the technology and will be provided with a telephone number and email address of research personnel for troubleshooting.

Ongoing data collection will include weight, BMI, number of steps per day and measures of engagement with the intervention (ie, number of logins to fit.healthy.me, number of days the scale/tracker was used, number of interactions in the social network). Weight, BMI and step count data, dated and timestamped for each participant, will be retrieved by the research team via the Fitbit API.

At the end of the study, participants will be asked to attend a 30 min session at the study centre to answer a few questions and provide feedback regarding the intervention. Satisfaction will be measured by administering the System Usability Scale; scores will be calculated according to Brooke’s guidelines.42

Quantitative data analysis

Outcomes will be compared between baseline and 6 months using dependent t-tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests will be used where data are not normally distributed. Sensitivity analyses will explore whether adherence to the intervention influences outcomes.

Qualitative data analysis

For the qualitative data analysis, audiotapes will be transcribed verbatim. Content analysis of the qualitative information gathered will be done using NVivo (Melbourne, Australia). Two researchers will systematically review and code the transcripts, following the constant comparative method and thematic analysis.43 44 Discrepancies in coding between the two investigators will be resolved through consensus. Extracts from the text files will be provided to illustrate each theme or content area.

Ethics and dissemination

Questions or concerns regarding participation will be addressed individually. Participation in the study will be purely voluntary, and participants will have the right to withdraw from participation in this study at any time, without having to give a reason and without adverse consequences.

The social network will be monitored by a research member with clinical expertise, who will respond to concerns raised by participants. Additionally, a protocol will be in place to monitor for participant misbehaviour and direct participants-in-need to appropriate sources of help. Monitoring will involve daily observation of measures collected by the fitness tracker and the wireless scale, as well as continuous supervision of social network interactions and posts.

In the unlikely case that participants mention psychological distress on the forum or experience concerning weight changes, the following procedure will apply: research staff will make a posting on the forum to provide information about where to seek additional help (ie, seek consultation with general practitioner, attend a nominated counselling service). If a participant reports on the forum that they are experiencing high levels of distress, we will contact the participant informing that they should immediately attend their local hospital emergency department, general practitioner and/or call Lifeline or 000.

The social features of fit.healthy.me have been previously used in several studies.35 36 45 46 A button to report any concerns is available to all participants and displayed after each post in the forum. When this button is used, immediate action is taken by the investigators to contact the participants involved and provide the necessary support. This protocol has been used in four Healthy.me trials with more than 2000 participants in areas such as influenza vaccination, well-being, sexual health and asthma.35 36 45 46

Caution will be taken in the handling and storage of the data so that risks to privacy are minimised, in accordance with the Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research. Research data will be held in a secure storage repository at Macquarie University, and the electronic data will only be accessible to individual researchers during the time of their involvement in the project. Electronic data will be stored on password-protected computer. No data will be allowed to leave Macquarie University. Hard copies will be securely stored in a locked cabinet at the Australian Institute of Health Innovation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Bahia Chahwan, Burcu Yüksel, Camilla Andersson and Tania Polhill for their contributions to study design and mobile application design and development.

Footnotes

Twitter: @LilianaLaranjo

Contributors: LL, AYSL, PM, HLT and EC developed the protocol, drafted the manuscript, critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding: This research is supported by a grant received from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Centre of Research Excellence in Informatics and E-Health (1032664).

Competing interests: EC and AL could benefit from commercialisation of fit.Healthy.me.

Ethics approval: Macquarie University’s Human Research Ethics Committee for Medical Sciences.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, et al. . Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999-2010. JAMA 2012;307:491. 10.1001/jama.2012.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peeters A, Barendregt JJ, Willekens F, et al. . Obesity in adulthood and its consequences for life expectancy: a life-table analysis. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:24–32. 10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adams KF, Schatzkin A, Harris TB, et al. . Overweight, obesity, and mortality in a large prospective cohort of persons 50 to 71 years old. N Engl J Med 2006;355:763–78. 10.1056/NEJMoa055643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jolly K, Lewis A, Beach J, et al. . Comparison of range of commercial or primary care led weight reduction programmes with minimal intervention control for weight loss in obesity: lighten up randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2011;343:d6500. 10.1136/bmj.d6500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dombrowski SU, Knittle K, Avenell A, et al. . Long term maintenance of weight loss with non-surgical interventions in obese adults: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2014;348:g2646. 10.1136/bmj.g2646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sacks FM, Bray GA, Carey VJ, et al. . Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. N Engl J Med 2009;360:859–73. 10.1056/NEJMoa0804748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Casazza K, Fontaine KR, Astrup A, et al. . Myths, presumptions, and facts about obesity. N Engl J Med 2013;368:446–54. 10.1056/NEJMsa1208051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cunningham SA, Vaquera E, Maturo CC, et al. . Is there evidence that friends influence body weight? A systematic review of empirical research. Soc Sci Med 2012;75:1175–83. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.05.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fletcher A, Bonell C, Sorhaindo A. You are what your friends eat: systematic review of social network analyses of young people's eating behaviours and bodyweight. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011;65:548–55. 10.1136/jech.2010.113936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cohen-Cole E, Fletcher JM. Is obesity contagious? Social networks vs. environmental factors in the obesity epidemic. J Health Econ 2008;27:1382–7. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pachucki MA, Jacques PF, Christakis NA. Social network concordance in food choice among spouses, friends, and siblings. Am J Public Health 2011;101:2170–7. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Christakis NA, Fowler JH. Social contagion theory: examining dynamic social networks and human behavior. Stat Med 2013;32:556–77. 10.1002/sim.5408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med 2007;357:370–9. 10.1056/NEJMsa066082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Coiera E, networks S. Social media, and social diseases. BMJ 2013;346:f3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Valente TW. Network interventions. Science 2012;337:49–53. 10.1126/science.1217330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Valente T, . Social Networks and Health. Oxford University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Glanz K, Rimer B, Viswanath K. Health Behavior and Health Education. SanFrancisco, 2008. 4th ed. [Google Scholar]

- 18. McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook JM. Birds of a feather: homophily in social networks. Annu Rev Sociol 2001;27:415–44. 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hartmann-Boyce J, Johns DJ, Jebb SA, et al. . Effect of behavioural techniques and delivery mode on effectiveness of weight management: systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Obes Rev 2014;15:598–609. 10.1111/obr.12165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Patel MS, Volpp KG, Rosin R, et al. . A Randomized Trial of Social comparison feedback and financial incentives to increase physical activity. Am J Health Promot 2016;30:416–24. 10.1177/0890117116658195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. boyd danahm, Ellison NB. Social network sites: definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 2007;13:210–30. 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ashrafian H, Toma T, Harling L, et al. . Social networking strategies that aim to reduce obesity have achieved significant although modest results. Health Aff 2014;33:1641–7. 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rovniak LS, Sallis JF, Kraschnewski JL, et al. . Engineering online and in-person social networks to sustain physical activity: application of a conceptual model. BMC Public Health 2013;13:753. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Laranjo L, Arguel A, Neves AL, et al. . The influence of social networking sites on health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2015;22:243–56. 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Centola D. The spread of behavior in an online social network experiment. Science 2010;329:1194–7. 10.1126/science.1185231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Centola D. An experimental study of homophily in the adoption of health behavior. Science 2011;334:1269–72. 10.1126/science.1207055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maher CA, Lewis LK, Ferrar K, et al. . Are health behavior change interventions that use online social networks effective? A systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2014;16:e40. 10.2196/jmir.2952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Laranjo L, Arguel A, Neves AL, et al. . The influence of social networking sites on health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2015;22:243–56. 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Greene J, Sacks R, Piniewski B, et al. . The impact of an online social network with wireless monitoring devices on physical activity and weight loss. J Prim Care Community Health 2013;4:189–94. 10.1177/2150131912469546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hales S, Turner-McGrievy GM, Wilcox S, et al. . Social networks for improving healthy weight loss behaviors for overweight and obese adults: a randomized clinical trial of the social pounds off digitally (Social POD) mobile app. Int J Med Inform 2016;94:81–90. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Eapen ZJ, Peterson ED. Can mobile health applications facilitate meaningful behavior change?: time for answers. JAMA 2015;314:1236–7. 10.1001/jama.2015.11067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kooiman TJ, Dontje ML, Sprenger SR, et al. . Reliability and validity of ten consumer activity trackers. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil 2015;7:24. 10.1186/s13102-015-0018-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, et al. . CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2016;2:64. 10.1186/s40814-016-0105-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 1995;854:1-452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lau AY, Sintchenko V, Crimmins J, et al. . Impact of a web-based personally controlled health management system on influenza vaccination and health services utilization rates: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012;19:719–27. 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lau AY, Proudfoot J, Andrews A, et al. . Which bundles of features in a Web-based personally controlled health management system are associated with consumer help-seeking behaviors for physical and emotional well-being? J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e79. 10.2196/jmir.2414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sushames A, Edwards A, Thompson F, et al. . Validity and reliability of Fitbit Flex for step count, moderate to vigorous physical activity and activity energy expenditure. PLoS One 2016;11:e0161224–14. 10.1371/journal.pone.0161224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Colley R, Connor Gorber S, Tremblay MS. Quality control and data reduction procedures for accelerometry-derived measures of physical activity. Health Rep 2010;21:63–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dominick GM, Winfree KN, Pohlig RT, et al. . Physical activity assessment between consumer- and research-grade accelerometers: a comparative study in free-living conditions. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2016;4:e110. 10.2196/mhealth.6281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med 1991;32:705–14. 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Edmunds WJ. Social ties and susceptibility to the common cold. JAMA 1997;278:1231b–1231. 10.1001/jama.278.15.1231b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Brooke J. SUS - A quick and dirty usability scale. Usability Eval Ind 1996;189:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Taylor S, Bogdan R. Introduction to qualitative research methods: the search for meanings. New York: Wiley, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mortimer NJ, Rhee J, Guy R, et al. . A web-based personally controlled health management system increases sexually transmitted infection screening rates in young people: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2015;22:805–14. 10.1093/jamia/ocu052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lau AY, Dunn AG, Mortimer N, et al. . Social and self-reflective use of a web-based personally controlled health management system. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e211 10.2196/jmir.2682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.