Abstract

Importance

Published guidelines describing effective adolescent depression care in primary care settings include screening, assessment, treatment initiation, and symptom monitoring. It is unclear the extent to which these steps are documented in patient health records.

Objectives

To determine rates of appropriate follow-up care for adolescents with newly-identified depression symptoms in three large health systems.

Design

Structured data retrospectively extracted from electronic health records were analyzed for three months following initial symptom identification to determine whether the patient was followed up and, if so, whether treatment was initiated and/or symptoms were monitored.

Setting

Records were collected from two large health maintenance organizations (HMOs) in the western United States and a network of community health centers in the Northeast.

Participants

The study group included adolescents (n = 4612) with newly-identified depression symptoms, defined as an elevated score on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 ≥ 10) and/or a diagnosis of depression.

Main Outcome and Measures

Outcomes included rates of treatment initiation, symptom monitoring, and follow-up care documented within three months of initial symptom identification.

Results

Treatment was initiated for nearly two-thirds of adolescents (79% of those with a diagnosis of Major Depression); most received psychotherapy alone or in combination with medications. However, in the three months following identification, 36% of adolescents received no treatment, 68% did not have a follow-up symptom assessment, and 19% did not receive any follow-up care. Further, 49% of adolescents prescribed antidepressant medication did not have any documentation of follow-up care for three months. Younger age, more severe initial symptoms, and receiving a diagnosis was significantly associated with treatment initiation. Differences in rates of follow-up care were evident between sites, suggesting that differences within health systems may also affect care received.

Conclusions and Relevance

Most adolescents with newly-identified depression symptoms received some treatment, usually including psychotherapy, within the first three months after identification. However, follow-up care was low and substantial variation existed between sites. Results raise concerns about the quality of care for adolescent depression.

Major depression is a chronic, disabling condition affecting 12% of adolescents,1 with as many as 26% of youth experiencing at least mild depressive symptoms.2 Depression impairs social and academic functioning and is associated with poor long term outcomes.3–5 As many as 8% of youth who develop depression during adolescence complete suicide by young adulthood,3 and medical costs associated with adolescent depression are higher than those for almost any other mental health condition. 3,6

Timely initiation of effective treatment is crucial since failure to achieve remission is associated with higher likelihood of relapse, developing recurrent depression, and more impaired long term functioning.7, 8 Early intervention for symptomatic youth may also prevent development of a depressive episode.9 Diagnosed adolescents who enter treatment at a younger age, earlier in the course of a depressive episode, and prior to developing chronic depression have better outcomes following acute treatment.10 However, although effective treatments exist, up to 80% of adolescents with depression do not receive appropriate care.11

This gap in care and the emergence of child mental health care as a national priority12 spurred efforts to improve care. Primary care settings have been targeted to increase early identification and access to effective care.13,14 Depression care toolkits and practice guidelines have been disseminated to support primary care providers (PCPs) in evidence-based identification and treatment of adolescent depression.15–17 Recent legislation (i.e., 2009 Child Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act, 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act) emphasized adherence to effective care standards and accountability for the quality of care through the development of health care quality measures/indicators. In an effort to identify evidence-based targets for quality measures, synthesize available provider guidelines, and inform a research agenda, Lewandowski and colleagues developed a care pathway describing “essential practices for adolescent depression management from screening to symptom remission.”18

Federal initiatives incentivizing universal use of electronic health records (EHRs) including the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act and Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act dramatically increased opportunities to conduct comprehensive, timely evaluations of care. Incentives for meaningful use of EHRs target enhanced care coordination, reduced medical errors, and provide a platform from which to conduct large-scale routine measurement of care quality. However, the vast majority of these initiatives do not include behavioral health indices.19

Little empirical research has evaluated routine care for adolescent depression. What is known suggests the need for vast improvements. Despite recommendations from several national bodies,20, 21, 22 screening for adolescent depression in primary care is rare.23 In pediatric primary care settings with policies specifically targeting universal screening for adolescent depression, 36% of youth exhibit significant symptoms.23 However, only 17–27% of depressed adolescents receive treatment in usual care settings.24, 25 No studies to date have evaluated the documented course of care for adolescents from symptom identification through treatment initiation.

The current study aims to add to this emerging literature by evaluating the initial course of care for adolescents identified with depressive symptoms in primary care settings as it is documented in the EHR. This study examined routine care in several large health care systems to assess whether adolescents newly-identified with depression symptoms received appropriate follow-up care in the three months following identification. Elements of appropriate follow-up care were based on the depression care management pathway18 and included initiating antidepressant or psychotherapy treatment, having at least one follow-up visit, and symptom monitoring with a well-validated questionnaire.

METHOD

Data sources and sample

Data were abstracted from EHRs of three large health provider systems. Organizations were recruited through colleagues and prior collaborations, and were identified for study inclusion if they used any version of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9),26 reported serving at least 500 adolescents with depression diagnoses in the previous calendar year, offered behavioral health services, and used a consistent EHR across practice settings to facilitate data collection (i.e., data collected in structured fields could be queried by analysts at each site, de-identified, and transmitted to the authors). The first three organizations contacted that met these criteria agreed to participate. Two large health maintenance organizations (HMOs) in the western United States and a network of community health centers in the Northeast (identities masked per agreements) participated and were compensated for their participation. This study was approved by the Chesapeake Institutional Review Board and the Institutional Review Boards at each site.

Retrospective data collection identified patients eligible for study inclusion during an intake period from January 1st, 2012 – June 30th, 2013. Eligible participants were adolescents ages 12–20 on January 1st, 2012 with at least one face-to-face provider visit during the intake period and documented symptoms of depression. At the HMOs, participants were limited to those continuously enrolled during the study period.

The index event was the first evidence of newly-identified symptoms of depression, defined by elevated PHQ (score ≥ 10), new depression diagnosis, or both within the same 30-day period. To determine both history and follow-up care, data were collected for 6 months before and 3 months after the index event. Patients with evidence of bipolar, psychotic, autism spectrum, or personality disorders at any time were excluded. Since a primary aim of this study was to evaluate care for newly-identified depression symptoms, patients were also excluded if there was evidence 6 months prior to the index event of depression diagnosis, antidepressants prescribed, or previous positive PHQ. Data collected included: 1) dates of administration and scores for all depression symptom questionnaires; 2) dates, Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes, and encounter diagnoses for all face-to-face primary care or mental health visits/encounters; 3) dates and active psychopharmocologic compounds for all antidepressants prescribed or recorded on a medications list, and 4) demographic information.

Measures

Depression Symptoms

The Patient Health Quesionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) is a 9-item self-report questionnaire assessing depression symptoms and severity that has been validated for use with adolescents.26,27 Very slight modifications have been made for adolescents (e.g., replacing an item about “work” to “schoolwork”), resulting in the PHQ-9 Modified for Adolescents (PHQ-A) and the PHQ-modified for teens. All sites used at least one of these verssions with their adolescent population, collectively referred to hereafter as PHQ. PHQ items are based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria for major depression and are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“nearly every day”). A score of 10 or higher indicates clinically significant symptoms (“moderate depression”), and was is consistent with clinical cutoffs reportedly used by providers within each site.

Depression diagnosis

Depression diagnoses in the current study included International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9)28 codes that indicate clinically significant symptoms of depression: Major Depressive Affective Disorder, Other and Unspecified Depressive Disorders, Dysthymia, and Adjustment Disorders that reflect significant depressive symptoms (i.e., with depressed mood; with mixed anxiety and depressed mood; with mixed disturbance of emotions and conduct; prolonged depressive reaction).

Demographic information

Demographic information was collected from EHR data fields. Variables included age, sex, race, ethnicity, insurance status at index event, presence of chronic medical conditions (e.g., asthma, obesity, or other physical health conditions) and co-occurring behavioral health diagnoses.

Medication treatment

Antidepressant medication treatment was determined by an indication of an antidepressant on the patient’s medication list or in a specific field for prescription information within the EHR.

Psychotherapy treatment

Any visit including a CPT code for psychotherapy was identified.

Statistical Analyses

Standard descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and clinical characteristics overall and across sites. Rates of treatment initiation within 3 months were compared across levels of demographic and clinical characteristics, with statistical hypothesis tests conducted by chi-squared tests. Logistic regression models were used to compare the odds of any treatment initiation within 3 months across levels of demographic and clinical characteristics, and across sites. Univariate and bivariate analyses were conducted to describe the sample and compare differences across organizations and patient characteristics. Logistic regression analyses were performed to assess the impact of demographic and clinical characteristics on treatment initiation. Demographic (age, sex, race, ethnicity) and clinical (index event, symptom severity, diagnosis) characteristics were included in the regression models if they significantly contributed to the model (i.e., p < .05). Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 21.29

RESULTS

Descriptives

4612 adolescents (67% female) were identified with depression symptoms. Significant differences across sites were evident for all baseline variables except patient sex (Table 1). Most adolescents were Caucasian (63%) and not identified as Hispanic/Latino (74%), though race data were frequently missing (21%). Sites 2 and 3 primarily served patients with commercial insurance/self-pay (95% and 99%), while most patients at Site 1 had Medicaid/CHIP insurance (72%). Nearly two thirds of patients had comorbid behavioral health diagnoses, and chronic physical health conditions were also common, 41% (Site 1) and 70% (Site 2; not reported at Site 3).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics by Site

| Site 1 (n = 855) | Site 2 (n = 1750) | Site 3 (n = 2007) | Total sample (n = 4612) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at index event, mean (SD), years | 15.2 (2.0) | 15.6 (2.1) | 16.7 (2.4) | 16.0 (2.3)* |

| Female sex, No. (%) | 582 (68) | 1136 (65) | 1342 (66) | 3060 (66) |

| Race, No. (%) | ||||

| White/Caucasian | 303 (35) | 1155 (66) | 1446 (72) | 2904 (63)* |

| Black/African American | 128 (15) | 70 (4) | 100 (5) | 298 (7) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 9 (1) | 32 (2) | 114 (6) | 155 (3) |

| Other/Multiracial | 6 (1) | 59 (3) | 217 (11) | 282 (6) |

| Missing | 409 (48) | 434 (25) | 130 (6) | 973 (21) |

| Ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 399 (47) | 326 (19) | 162 (8) | 887 (19)* |

| Missing | 113 (13) | 160 (9) | 69 (3) | 342 (7) |

| Insurance at index event, No. (%) | ||||

| Medicaid/CHIP | 617 (72) | 81 (5) | 18 (1) | 716 (16)* |

| Commercial, other, self-pay | 238 (28) | 1669 (95) | 1989 (99) | 3896 (85) |

| Comorbid condition, No. (%) | ||||

| Chronic health condition | 347 (41) | 1232 (70) | --a | --a* |

| Behavioral health condition | 403 (47) | 1107 (63) | 1471 (73) | 2981 (65)* |

| Index event, No. (%) | ||||

| Positive PHQ (≥ 10) | 487 (57) | 218 (12) | 1187 (59) | 1892 (41)* |

| Depression diagnosis | 258 (30) | 889 (51) | 255 (13) | 1402 (30) |

| Both positive PHQ and depression diagnosis | 110 (13) | 643 (37) | 565 (28) | 1318 (29) |

| PHQ-9 Score at index event, mean (SD) | 14.0 (3.6) | 15.4 (4.1) | 15.7 (4.2) | 15.3 (4.1)* |

| Diagnosis at index event, No. (%) | ||||

| Major Depression | 15 (4) | 726 (47) | 554 (68) | 1295 (47)* |

| Dysthymia | 111 (30) | 61 (4) | 36 (4) | 208 (8) |

| Unspecified Depression | 158 (43) | 366 (24) | 130 (16) | 654 (24) |

| Adjustment disorder with depressive symptoms | 84 (23) | 379 (25) | 100 (12) | 563 (21) |

Note:

Test of between-site differences significant at the level p < .001,

Site did not provide this information

The majority of patients were identified at the index event through a positive PHQ alone (Site 1 = 57%; Site 3 = 59%), or a new depression diagnosis alone (Site 2 = 51%). Diagnoses at the index event were most often Major Depression (47%) or Other/Unspecified Depression (24%). The average PHQ score at the index event indicated moderately severe symptoms (mean = 15.3, SD = 4.1), though this was significantly lower at Site 1 (mean = 14.0, SD = 3.6), consistent with moderate symptoms. Adolescents identified with a positive PHQ only had a significantly lower score (mean = 15.5, SD = 3.9) than those with both a positive PHQ and a new diagnosis (mean = 16.4, SD = 4.2). Among adolescents with a positive PHQ only, 12% received a depression diagnosis during the three month follow-up period, and an additional 20% received another behavioral health diagnosis (e.g., anxiety disorders).

Symptom Monitoring

Regardless of other follow-up care, documentation of symptom monitoring (i.e., PHQ administered) in the three month follow-up period was present for only 32% of adolescents. Significant differences between sites indicated that patients at Site 1 were less likely to have a PHQ score recorded (6%) than Sites 2 (31%) or 3 (44%, p < .001).

Treatment Initiation

64% of adolescents initiated treatment within the follow-up period; 19% received antidepressants only, 29% received psychotherapy only, and 16% received combined treatment (Table 2). Older adolescents were significantly more likely to receive treatment, and were over four times more likely to receive only antidepressants. Rates and types of treatment were similar for males and females. Adolescents with a positive PHQ only at the index event were least likely to receive any treatment (54%). Higher initial PHQ scores (i.e., more severe symptoms) and diagnoses of Major Depression were associated with significantly higher rates of receiving treatment.

Table 2.

Treatment Initiation Within 3 Months of Index Event by Baseline Characteristics

| Sample (n) | Anti-depressant medication only (%) | Therapy only (%) | Combined treatment (%) | Total any treatment (%) | No treatment (%) | p valuesa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 4612 | 19 | 29 | 16 | 64 | 36 | |

| Age at index event | .042 | ||||||

| 12–14 | 1346 | 8 | 42 | 14 | 64 | 36 | |

| 15–17 | 1891 | 17 | 27 | 18 | 62 | 38 | |

| 18–21 | 1375 | 33 | 18 | 15 | 66 | 34 | |

| Sexb | .53 | ||||||

| Male | 1550 | 19 | 27 | 17 | 63 | 37 | |

| Female | 3060 | 20 | 29 | 15 | 64 | 36 | |

| Race | < .001 | ||||||

| White/Caucasian | 2904 | 22 | 29 | 18 | 69 | 31 | |

| Black/African American | 298 | 15 | 25 | 9 | 49 | 51 | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 155 | 17 | 26 | 14 | 57 | 43 | |

| Other/Multiracial | 282 | 18 | 26 | 21 | 65 | 35 | |

| Missing | 973 | 12 | 30 | 10 | 52 | 48 | |

| Ethnicity | < .001 | ||||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 887 | 13 | 29 | 9 | 51 | 49 | |

| Missing | 342 | 14 | 31 | 11 | 56 | 44 | |

| Index Event | < .001 | ||||||

| Positive PHQ (≥ 10) | 1892 | 17 | 25 | 12 | 54 | 46 | |

| Depression diagnosis | 1402 | 17 | 37 | 12 | 66 | 34 | |

| Bothc | 1312 | 25 | 26 | 25 | 76 | 24 | |

| PHQ-9 Score at index event | < .001 | ||||||

| Noned | 1412 | 17 | 37 | 12 | 66 | 34 | |

| Moderate (10–14) | 1563 | 15 | 27 | 12 | 54 | 46 | |

| Moderately Severe (15–19) | 1088 | 24 | 23 | 20 | 67 | 33 | |

| Severe (20+) | 549 | 27 | 22 | 29 | 78 | 22 | |

| Diagnosis at index event | < .001 | ||||||

| Major Depression | 1295 | 30 | 24 | 25 | 79 | 21 | |

| Dysthymia | 208 | 25 | 32 | 7 | 64 | 36 | |

| Unspecified Depression | 654 | 14 | 31 | 19 | 64 | 36 | |

| Adjustment Disordere | 563 | 6 | 50 | 7 | 63 | 37 | |

| No diagnosisf | 1892 | 17 | 24 | 12 | 53 | 47 |

Notes:

Chi-square test of difference between “Total any treatment” and “No treatment” groups;

Values for sex were missing for two individuals.

Both positive PHQ and depression diagnosis;

New diagnosis only as index event;

Only those with depressive symptoms included;

Positive PHQ only as index event

Treatment initiation was significantly associated with site and several patient characteristics (see Table 3; R2 =.13). Preliminary analyses indicated that patient sex was not significantly associated with treatment initiation; it was therefore excluded from the model. Compared to Site 1, Sites 2 and 3 were twice as likely to initiate treatment. Patient race (Caucasian) and younger age were significantly associated with treatment initiation. Adolescents who did not receive a PHQ at the index event and those with scores in the moderate range were equally likely to initiate treatment, while those with more severe scores initiated treatment 1.5–2.2 times more often. Receiving a diagnosis was significantly associated with treatment initiation.

Table 3.

Multivariable Model Predicting Any Treatment Initiation.

| OR (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Site | ||

| Site 1 | Ref. | < .001 |

| Site 2 | 1.77 (1.45 – 2.16) | |

| Site 3 | 2.10 (1.72 – 2.57) | |

| Age at index event | ||

| 12–14 | Ref. | .008 |

| 15–17 | 0.78 (0.67 – 0.92) | |

| 18–20 | 0.83 (0.70 – 0.99) | |

| Race | ||

| White/Caucasian | Ref. | < .001 |

| Black/African American | 0.55 (0.43 – 0.71) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.54 (0.39 – 0.77) | |

| Other/Multi-racial | 0.76 (0.58 – 0.99) | |

| Missing | 0.63 (0.54 – 0.75) | |

| PHQ score at index event | ||

| None (new diagnosis only as index event) | Ref. | < .001 |

| Moderate (10–14) | 0.99 (0.82 – 1.21)a | |

| Mod-Severe (15–19) | 1.46 (1.19 – 1.80) | |

| Severe (20+) | 2.14 (1.65 – 2.79) | |

| Diagnosis at index event | ||

| No diagnosis (positive PHQ-9 only as index event) | Ref. | < .001 |

| Major Depression/Dysthymia | 2.65 (2.20 – 3.20) | |

| Unspecified Depression/Adjustment disorderb | 1.75 (1.43 – 2.14) | |

Notes: OR = Odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire;

Not significantly different than the referent group

Only those adjustment disorders with depressive symptoms included

Follow-up care

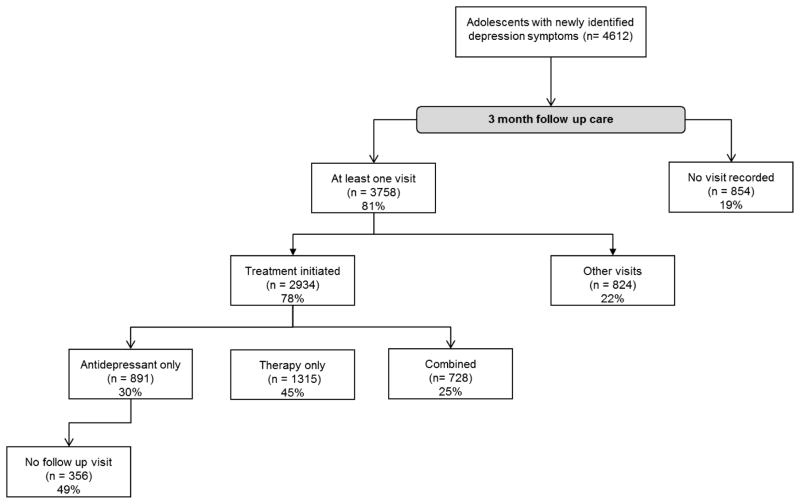

As shown in Figure 1, 19% of adolescents with newly-identified depression symptoms did not receive any follow-up visit. Treatment was initiated for 78% of adolescents who did receive a follow-up visit. Among adolescents prescribed antidepressants only (i.e., did not receive therapy), 49% did not have another visit recorded in the 3 month follow-up period.

Figure 1.

3-month follow-up care

aOther visits: any documented visit that did not include a behavioral health treatment or antidepressant medication, such as an ill visit or well-child visit

DISCUSSION

Rates of appropriate follow-up care for adolescents with newly-identified depression symptoms in three large health systems were examined via structured data retrospectively extracted from electronic health records. Treatment was initiated for nearly two thirds of adolescents, the majority of whom received psychotherapy. Nearly 80% of youth with diagnoses of Major Depression initiated treatment. Regardless of treatment initiation, two thirds of adolescents did not have further symptom monitoring with a PHQ. 19% of adolescents identified with clinically significant depression symptoms and 49% of adolescents prescribed antidepressants had no documentation of follow-up care. Differences in rates of follow-up care were evident across sites, suggesting differences within health systems may impact care.

Appropriately identifying symptoms and diagnoses are initials steps in the adolescent depression care pathway,18 and are essential to providing adequate follow-up care and treatment.30 Essential to assessment is measuring symptom severity31 and 70% of adolescents received a symptom-based questionnaire (PHQ) at the index event. Symptom assessment is critical to guiding treatment decisions for depressed adolescents, since initial PHQ scores have been associated with symptom severity up to six months later.32

Presence of both an elevated PHQ and a new diagnosis at the index event is arguably representative of higher quality of care than either alone, as it suggests assessment to confirm a diagnosis. A modest percentage of adolescents fell into this category (13–37%). Variability across sites was evident for diagnoses conferred; Site 1 reported higher rates of dysthymia and other/unspecified depression than expected.5 This may reflect providers’ lack of diagnostic confidence or use of these diagnoses “in lieu of”, perhaps due to concerns of stigma associated with major depression. Importantly, neither a PHQ score nor a recorded diagnosis confirm that an adequate clinical assessment was conducted. It may be the case that some PCPs inadvisably recorded a diagnosis based solely on the positive screen, which has implications for assumptions of appropriate treatment and follow up care.

Regardless of diagnosis, 19% of adolescents identified with clinically significant depression symptoms received no care for the following three months. Follow-up contact and further assessment following a positive screen are recommended even for mild symptoms by current guidelines and best practices.18 These findings raise concerns that many depressed adolescents receive an unacceptable level of care, particularly striking since over half of adolescent suicide completers suffer from chronic, unremitted depression.33,34

Also concerning was the lack of follow-up care after prescribing an antidepressant. Current black box warnings highlight the risk of increased suicidality for youth prescribed antidepressants and recommend patients are “monitored appropriately and observed closely…especially during the initial few months.”35, yet nearly half of adolescents prescribed an antidepressant did not have a visit in the three months following prescription.

Treatment early in a depressive episode, particularly for younger adolescents, may improve outcomes9,10,36, so finding that treatment was initiated for the majority of adolescents was encouraging. Though youth with more severe symptoms based on PHQ score were more likely to receive treatment, 22% of adolescents endorsing severe symptoms remained untreated. Younger adolescents were more likely to receive psychotherapy and much less likely to receive medication alone. This is consistent with current recommendations, which encourage supportive counseling, monitoring, and/or psychotherapy as first line treatment, particularly for younger adolescents or youth with mild symptoms.18

Half of adolescents with only a positive PHQ at the index event initiated treatment, 29% of whom received antidepressants. A small percentage of adolescents identified with a positive PHQ only received a depression or other behavioral health diagnosis later in the follow-up period, possibly reflecting initial observation or further assessment. The remaining youth treated without a diagnosis may reflect providers’ reluctance to diagnose, though they recognized the need to provide care.

Regardless of treatment initiation, symptom monitoring is recommended.21, 22 A recent study of a collaborative care model including regular symptom monitoring found significantly better depression outcomes for adolescents.24 In the current study, rates of symptom monitoring were modest (32%). Significant variability across sites may represent the impact of organizational policy on care. Site 3 reported policies requiring PHQs be administered for antidepressant refills, possibly driving the noticeably higher rate of symptom monitoring at the Site (44%). In contrast, Site 1, where rates of symptom monitoring were 6%, reported policies encouraging universal screening, but not symptom monitoring.

Limitations and Future Directions

The primary limitation of this and other studies relying on medical record (EHR) data is that conclusions depend on how information is gathered and recorded. Distinctions between lack of appropriate follow-up care or failure to document care events cannot be made. Alternative appropriate provider behaviors (e.g., specialist referrals, telephone follow-up contact) or relevant patient behaviors (treatment dropout/refusal, electing to receive care elsewhere, change in insurance or location, barriers to access including transportation and insurance coverage) were not evaluated in the current study because such information was rarely documented in structured data fields. Future studies should seek to accurately assess the extent to which PCPs conduct accurate clinical assessments that inform appropriate follow up care.

These challenges to documentation are common to EHR-based research evaluations of mental health care quality.37 However, similar documentation is required for quality measurement, quality improvement initiatives, and continuity of care. Thus, limitations of data availability are not only problematic for research, but also reflect limitations in what members of the clinical team are able to learn about the patient. Therefore, limitations of EHR documentation are themselves likely contributors to poor quality of care.

Finally it is unclear the extent to which findings from the current study are generalizable beyond the settings in which data were collected. Differences in outcomes and potential health care disparities between Site 1 (serving predominantly racial/ethnic minority Medicaid recipients) and Sites 2 and 3 (serving primarily Caucasian, privately insured youth) were not explored in the current study; and in fact high rates of missing data (e.g., race) hinder further analyses. Moreover, the participating sites are highly regarded health care institutions. They are often looked to as leaders in cutting edge care that routinely employ quality improvement initiatives focused on adolescent behavioral health care. Thus, results from the current study, discouraging as they are, may overstate the quality of care in other settings.

Clinical Implications/Conclusions

Current standards of care recommend that adolescents identified with depression symptoms receive further assessment, initiate antidepressant medication and/or psychotherapy treatment, and are monitored for changes in symptoms, especially following an antidepressant prescription. Evidence from this study suggests that quality of care in routine practice diverges from these standards. Given the negative outcomes associated with untreated adolescent depression,3–5 greater attention to improving adherence to quality standards is warranted.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: This project was supported by grant number U18HS020503 (PI: Scholle) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of AHRQ.

Financial Disclosure: The authors have indicated that they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data Integrity: Briannon O’Connor and Sarah Scholle had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis

References

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. Mental Health Findings NSDUH series H-42, HHS publication no.(SMA) 11-4667. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Ross J, Hawkins J, Harris WA, Lowry R, McManus T, Chyen D, Lim C, Whittle L, Brener ND, Wechsler H. Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2010;59(5):1–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weissman MM, Wolk S, Goldstein RB, Moreau D, Adams P, Greenwald S, Klier CM, Ryan ND, Dahl RE, Wickramaratne P. Depressed adolescents grown up. JAMA. 1999;281(18):1707–1713. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.18.1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewinsohn PM, Hops H, Roberts RE, Seeley JR, Andrews JA. Adolescent psychopathology: I. Prevalence and incidence of depression and other DSM-III-R disorders in high school students. J Abnorm Psychol. 1993;102(1):133–144. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Benjet C, Georgiades K, Swendsen J. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication--Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lynch FL, Clarke GN. Estimating the economic burden of depression in children and adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(6):143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Maser JD, Zeller PJ, Endicott J, Coryell W, Paulus MP, Kunovac JL, Leon AC, Mueller TI. Major depressive disorder: a prospective study of residual subthreshold depressive symptoms as predictor of rapid relapse. J Affect Disord. 1998;50(2):97–108. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paykel E, Ramana R, Cooper Z, Hayhurst H, Kerr J, Barocka A. Residual symptoms after partial remission: an important outcome in depression. Psychol Med. 1995;25(06):1171–1180. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700033146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarke GN, Hawkins W, Murphy M, Sheeber LB, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Targeted Prevention of Unipolar Depressive Disorder in an At-Risk Sample of High School Adolescents: A Randomized Trial of a Group Cognitive Intervention. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(3):312–321. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199503000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curry J, Rohde P, Simons A, Silva S, Vitiello B, Kratochvil C, Reinecke M, Feeny N, Wells K, Pathak S, Weller E, Rosenberg D, Kennard B, Robins M, Ginsburg G, March J. Predictors and Moderators of Acute Outcome in the Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(12):1427–1439. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000240838.78984.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet need for mental health care among US children: Variation by ethnicity and insurance status. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1548–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zima BT, Murphy JM, Scholle SH, Hoagwood KE, Sachdeva RC, Mangione-Smith R, Woods D, Kamin HS, Jellinek M. National quality measures for child mental health care: background, progress, and next steps. Pediatrics. 2013;131(Supplement 1):S38–S49. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1427e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horwitz SM, Leaf PJ, Leventhal JM, Forsyth B, Speechley KN. Identification and management of psychosocial and developmental problems in community-based, primary care pediatric practices. Pediatrics. 1992;89(3):480–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horwitz SM, Kelleher K, Boyce T, Jensen P, Murphy M, Perrin E, Stein RE, Weitzman M. Barriers to health care research for children and youth with psychosocial problems. Jama. 2002;288(12):1508–1512. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.12.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foy JM, Kelleher KJ, Laraque D. Enhancing pediatric mental health care: strategies for preparing a primary care practice. Pediatrics. 2010;125(Supplement 3):S87–S108. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0788E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jellinek MS, Patel BP, Froehle MC. Bright Futures in Practice: MentalHhealth. National Center for Education in Maternal and Child Health, Georgetown University; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheung AH, Zuckerbrot RA, Jensen PS, Ghalib K, Laraque D, Stein RE. Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): II. Treatment and ongoing management. Pediatrics. 2007;120(5):e1313–1326. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewandowski RE, Acri MC, Hoagwood KE, Olfson M, Clarke G, Gardner W, Scholle SH, Byron S, Kelleher K, Pincus HA. Evidence for the management of adolescent depression. Pediatrics. 2013;132(4):e996–e1009. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Council for Community Behavioral Healthcare. HIT Adoption and Readiness for Meaninful Use in Community Behavioral Health. Washington DC: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical Guideline 28: Depression in Children and Young People: Identification and Management in Primary, Community, and Secondary Care. London, UK: NHS; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Birmaher B, Brent D, Bernet W, Bukstein O, Walter H, Benson RS, Chrisman A, Farchione T, Greenhill L, Hamilton J, Keable H, Kinlan J, Schoettle U, Stock S, Ptakowski KK, Medicus J. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(11):1503–1526. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318145ae1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Force UPST. Screening and treatment for major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):1223–1228. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewandowski RE, O’Connor BC, Bertagnolli A, Beck A, Tinoco A, Gardner W, Jellinek-Berents C, Newton D, Wain K, Brace N, deSa P, Scholle SH, Hoagwood K, Horwitz SM. Screening and diagnosis of depression in adolescents in a large HMO. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400465. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richardson LP, Ludman E, McCauley E, Lindenbaum J, Larison C, Zhou C, Clarke G, Brent D, Katon W. Collaborative care for adolescents with depression in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(8):809–816. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.9259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asarnow JR, Jaycox LH, Duan N, LaBorde AP, Rea MM, Murray P, Anderson M, Landon C, Tang L, Wells KB. Effectiveness of a quality improvement intervention for adolescent depression in primary care clinics: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(3):311–319. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allgaier AK, Pietsch K, Fruhe B, Sigl-Glockner J, Schulte-Korne G. Screening for depression in adolescents: validity of the patient health questionnaire in pediatric care. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(10):906–913. doi: 10.1002/da.21971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richardson LP, McCauley E, Grossman DC, McCarty CA, Richards J, Russo JE, Rockhill C, Katon W. Evaluation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Item for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;126(6):1117–1123. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; [accessed March, 2015]. Classifications of Diseases, Functioning, and Disability [Internet] Available from: www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9cm.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 29.IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; Released 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mash EJ, Hunsley J. Evidence-based assessment of child and adolescent disorders: Issues and challenges. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2005;34(3):362–379. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3403_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Best Evidence Statement (BESt): Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) During the Acute Phase. Cincinnati, OH: Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richardson LP, McCauley E, McCarty CA, Grossman DC, Myaing M, Zhou C, Richards J, Rockhill C, Katon W. Predictors of persistence after a positive depression screen among adolescents. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6):e1541–e1548. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brent DA, Perper JA, Moritz G, Allman C, Friend A, Roth C, Schweers J, Balach L, Baugher M. Psychiatric risk factors for adolescent suicide: a case-control study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32(3):521–529. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199305000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaffer D, Gould MS, Fisher P, Trautman P, Moreau D, Kleinman M, Flory M. Psychiatric diagnosis in child and adolescent suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(4):339–348. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830040075012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. [Accessed March, 2015];US Food and Drug Administration wesbite. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/informationbydrugclass/ucm096273.htm.

- 36.Kennard B, Silva S, Vitiello B, Curry J, Kratochvil C, Simons A, Hughes J, Feeny N, Weller E, Sweeney M. Remission and residual symptoms after short-term treatment in the Treatment of Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(12):1404–1411. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000242228.75516.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Castillo EG, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Vawdrey D, Stroup TS. Electronic Health Records in Mental Health Research: A Framework for Developing Valid Research Methods. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(2):193–196. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]