Abstract

The objective of this study was to extend an ultrasound surface wave elastography (USWE) technique for noninvasive measurement of ocular tissue elastic properties. In particular, we aim to establish the relationship between the wave speed of cornea and the intraocular pressure (IOP). Normal ranges of IOP are between 12 and 22 mmHg. Ex vivo porcine eye balls were used in this research. The porcine eye ball was supported by the gelatin phantom in a testing container. Some water was pour into the container for the ultrasound measurement. A local harmonic vibration was generated on the side of the eye ball. An ultrasound probe was used to measure the wave propagation in the cornea noninvasively. A 25 gauge butterfly needle was inserted into the vitreous humor of the eye ball under the ultrasound imaging guidance. The needle was connected to a syringe. The IOP was obtained by the water height difference between the water level in the syringe and the water level in the testing container. The IOP was adjusted between 5 mmHg and 30 mmHg with a 5 mmHg interval. The wave speed was measured at each IOP for three frequencies of 100, 150 and 200 Hz. Finite element method (FEM) was used to simulate the wave propagation in the corneal according to our experimental setup. A linear viscoelastic FEM model was used to compare the experimental data. Both the experiments and the FEM analyses showed that the wave speed of cornea increased with IOP.

Keywords: surface wave elastography, wave speed, cornea, ultrasound, intraocular pressure

INTRODUCTION

Glaucoma is the second leading cause of blindness in the world. In the United States, more than 120,000 patients are blind from glaucoma [1]. The IOP is strongly related with the prevalence and severity of optic nerve axon damage in open angle glaucoma [2]. The normal range of IOP is between 12 and 22 mmHg. Elevation in IOP is associated with increasing prevalence of glaucoma and reduction of IOP is able to slow the disease progression [3]. Currently, reduction of IOP is the only available clinical treatment. However, a significant number of glaucoma patients continue to develop vision loss and blindness despite this treatment [4]. In a study, 738 eyes were categorized into three groups based on IOP determinations over the first three 6-month follow-up visits. It was found that eyes with early average IOP greater than 17.5 mmHg had an estimated worsening during subsequent follow-up that was 1 unit of visual field defect score greater than eyes with average IOP less than 14 mmHg (p = 0.002). Contrariwise, some patients with elevated IOP do not develop glaucoma [5]. These incongruities could arise due to alteration in stiffness of the ocular tissues and their response to elevated IOP. These factors are material determinants of IOP-derived lamina strain which is related to glaucoma occurrence [6]. Elevated IOP induces distention of the sclera and lamina cribrosa and impose direct mechanical strain on the axons of the optic nerve damaging nerve fibers and potentially impairing the nerve’s blood supply. Mechanical strain sustained by the optic nerve can also lead to thinning of the lamina cribrosa and increase in the translaminar pressure gradient, potentially impairing retrograde transport of neurotrophic factors from the lateral geniculate nucleus to the retinal ganglion cells [7]. Abnormal biomechanical properties of ocular tissues may also give rise to greater IOP variability, which has been increasingly recognized as another risk factor for glaucoma [8–10].

We have developed an ultrasound surface wave elastography (USWE) technique to characterize the biomechanical properties of superficial and deeper tissues, such as skin [11], lung [12], and tendon [13]. Currently, there is no non-invasive technique clinically available for evaluating the in-vivo biomechanical tissue properties of the eye. The purpose of this work is to noninvasively measure the wave speed of cornea in ex vivo porcine eyes and develop the relationship between the wave speed in cornea with IOP in the physiology ranges.

Porcine ocular tissues are commonly used to evaluate the mechanical behavior of various ocular tissues due to its similarities with human ocular tissues [14]. Moreover, with its availability, relevant animal models for systemic study of induced disease states, such as ocular hypertension, can be generated. Published investigations on various ocular tissues include optic nerve head [15, 16], sclera [17], and laminar cribrosa [18].

Numerous elastography techniques have been developed to study soft tissues such as livers, however, only limited applications are published on ocular tissues [19–21]. The aim of this study was to develop a noninvasive method for measuring the wave speed of cornea for various IOP using porcine eye balls. In USWE, a shaker was used to generate a small, local, short vibration on the surface of the eye, and the wave propagation in the ocular tissues was measured by using ultrasonic imaging and analysis.

In order to manipulate the IOP for ex vivo porcine eye balls, a 25 gauge butterfly needle was inserted into the vitreous humor space close to the cornea of the eye. The needle was connected to a syringe filled with saline. The IOP was obtained by the water column height of the syringe relative to the water level in the testing container. The IOP was changed from 5 mmHg to 30 mmHg with an interval of 5 mmHg. A FEM model was developed to simulate the wave propagation in the cornea according to the experiments and compare with the experimental data.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eight porcine eye balls were enucleated about 1 hour after death from 35–40 kg female pigs that were part of IACUC approved studies. The eyes were immersed in saline solution and then transported to the authors’ laboratory for experimental preparation. To support the eye ball for experiment, the eye was supported on some rubber materials and placed in a testing plastic container. A gelatin mixture was prepared from porcine skin gelatin (SIGMA-ALDRICH, Inc). The gelatin mixture was heated to 60° and then cooled down to the room temperature. The cooled gelatin mixture was poured into the plastic container to support the eye ball. The gelatin surrounded the eye ball but did not cover the surface of the eye ball completely. The gelatin mixture provided the support for the eye ball for experiment. The gelatin may also absorb some wave energy and reduce the wave reflection from hard boundaries of the testing container. The completed eye and gelatin structure was allowed to set overnight. The eye ball experiments were performed on the following day. In order to change the pressure in the eye ball, a 25 gauge butterfly needle was inserted into the vitreous humor space close to the cornea of the eye under the ultrasound imaging guidance. The needle was connected to a 10 mL syringe filled with water. The syringe was mounted on a retort stand and changed to different heights. The intraocular pressure (IOP) was obtained by the water height difference between the water level in the syringe and the water level in the testing container. Some water was put in the testing container for ultrasound measurement of the eye ball.

Intraocular pressure was maintained at a pressure between 5 and 30 mmHg and changed gradually at an interval of 5 mmHg by raising the syringe (Fig. 1). At each pressure level (5, 10 15, 20 25 and 30 mmHg), a sinusoidal vibration signal of 0.1 s duration was generated by a function generator (Model 33120A, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). The vibration signals were used at three frequencies of 100, 150, and 200 Hz. The excitation signal at a frequency was amplified by an audio amplifier (Model D150A, Crown Audio Inc., Elkhart, IN) and then drove an electromagnetic shaker (Model: FG-142, Labworks Inc., Costa Mesa, CA 92626) mounted on a stand. The shaker applied a 0.1s harmonic vibration on the surface of the eye ball using an indenter with 3 mm diameter (Fig. 1). The propagation of the vibration wave in the ocular tissues was measured using an ultrasound probe (Verasonics, Inc, Kirkland, WA) submerged in water and mounted above the cornea on another stand. The ultrasound system was equipped with a linear array transducer (L11-4, Philips Healthcare, Andover, MA) transmitting at 6.4 MHz center frequency. The measurements were repeated three times at each frequency and each pressure level.

Figure 1.

Experimental setup of the USWE system. The shaker was in touch with the limbus region of eye ball to generate a 0.1 second harmonic vibration while an ultrasound probe was placed over the eye ball to measure the wave speed of cornea noninvasively. A butterfly needle was inserted in the vitreous region of the eyeball with the ultrasound imaging guidance. The needle was connected to a syringe filled with water. The IOP was obtained by the water column height of the syringe relative to the water level in the testing container. The IOP was changed from 5 mmHg to 30 mmHg with an interval of 5 mmHg.

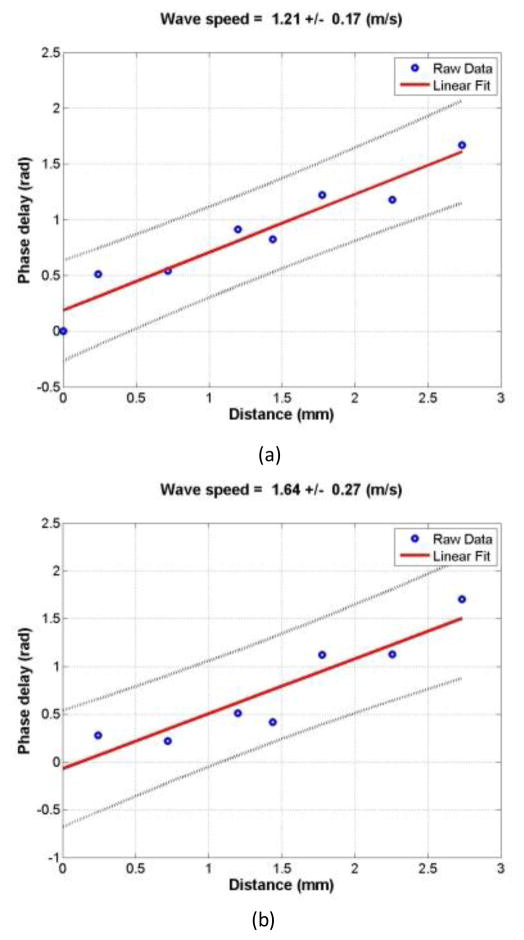

The wave motions were measured at eight locations in the cornea for each pressure level and for each frequency. The tissue motion at a location was measured by analyzing the ultrasound tracking beam through that location [22]. The wave speed was analyzed by the change in wave phase with distance. Using the tissue motion at the first location as a reference, the wave speed was measured using the wave phase delay of the remaining locations relative to the first location (Fig. 2). At each frequency, the wave speed in the cornea was estimated using a phase gradient method,

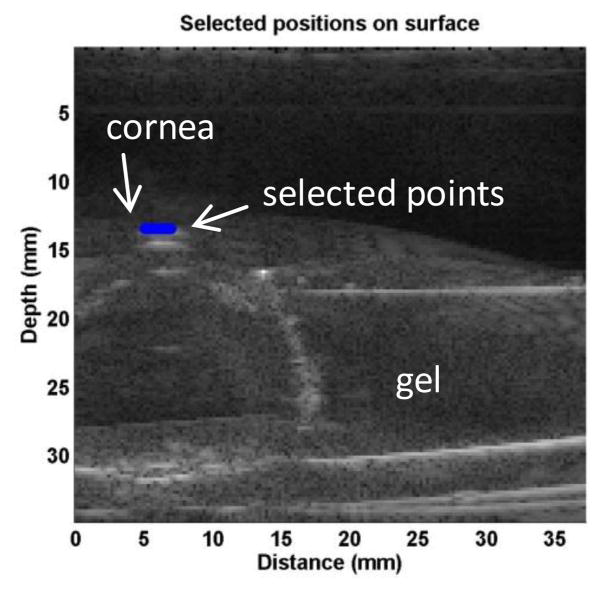

Figure 2.

Representative B-mode images of porcine ocular tissue. Eight locations in the cornea were selected to measure the wave speed in cornea by using the ultrasound tracking method. Blue dots indicate the points selected for measurement.

| (1) |

where Δr is the distance between 2 detected locations and Δϕ is the phase change over that distance, f is the excitation frequency in Hz. Three measurements were made at each frequency. It has been shown that on gelatin phantoms the wave speed estimation has a standard error less than 10% based on 7-point regression [23]. Therefore, it is necessary to obtain multiple measurements of Δϕ and a statistical regression to get accurate estimates of wave speed. Ideally, the phase of the surface wave ϕ at a particular frequency has a linear relationship with the distance. The wave speed was measured over eight locations in the central region of the cornea and analyzed with a linear regression curve obtained using a least-squares fitting technique on multiple Δϕ measurements,

| (2) |

where Δϕ̂ denotes the linear regression value of multiple Δϕ measurements, α and β are regression parameters, and the wave speed is calculated as follows,

| (3) |

The quality of the measurement of wave speed was assured by the sum of squares of linear regression residuals (R2) being ≥ 0.8 [22]. R2 is the coefficient of determinant ranging from 0 to 1, a statistical measure of how close the data fit the regression line. In general, the higher the R2, the better the model fits the data.

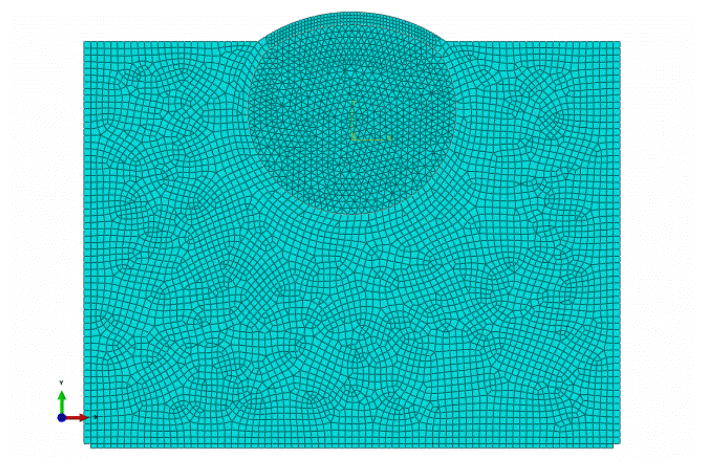

Numerical modeling

A FEM model was conducted in ABAQUS (version 6.12-1, 3DS Inc, Waltham, MA). The eye and surrounding gelatin was simulated by a 2D planar model of an infinite elastic medium with the density of 1000 kg m−3. Representative geometric model was reconstructed from image analysis of the surface profile at a reference pressure of 0 mmHg: The white-to-white corneal diameter was 13.5 mm. The central cornea thickness was 0.6 mm based on the ultrasound measurements; its radius of curvature was 7.5 mm and eccentricity was 0.5. The sclera radius of curvature was 12.8 mm, the anterior thickness was 0.88 mm, the equatorial thickness was 1.02 mm, and the posterior thickness was 1.45 mm.

The cornea and sclera were divided by a radial line through the center of the sclera ellipse. Vitreous humor fills, composed largely of hyaluronic acid, fill the posterior segment of the eye and were modelled as an acoustic medium. The cornea and sclera were modelled using a nearly incompressible, linear, viscoelastic generalized Maxwell model. The constitutive relationship is defined as follows [25]:

| (4) |

where Eequ is the equilibrium modulus, Ei is the relaxation modulus of the i-th branch. τi is the time constant of the i-th branch, ε is the strain, and ε̇ is the strain rate. In this study, a two branch model (i.e., m=2) was adopted [26]. The time constants (τ1 and τ2) are denoted as the short term time constant (τs) and the long time term constant (τl). The instantaneous (Einst) is defined as [27]:

| (5) |

The branch relaxation modulus were set to be equal (i.e., E1 = E2). Thus, the branch relaxation moduli can be found as:

| (6) |

It has been shown that sclera has stiffer response than cornea. So the instantaneous and equilibrium moduli of the sclera were set to be 5 times of those of the cornea [28–30]. To the best of our knowledge, viscoelastic properties of the porcine cornea and sclera have not been measured. The values of the material parameters of ocular shell and vitreous humor were estimated based on approximation of the model predictions with the results obtained from the infusion experiments in porcine eyes and were summarized in Table 1 [28].

Table 1.

Material parameters for the finite element model of the gelled porcine eye ball.

| Material | Einst [MPa] | Eequ [MPa] | τs[sec] | τl [sec] | Bulk modulus [GPa] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cornea | 1.1 | 0.265 | 0.35 | 68 | |

| sclera | 5.5 | 1.325 | 0.35 | 68 | |

| vitreous | 2.1404 | ||||

| gel |

The model was excited using a line source in the sclera and the displacement was applied in the radial direction. Harmonic excitations were performed at 100, 150, and 200 Hz with a duration of 0.1 s. A uniform pressure was applied on the inner surfaces of the cornea and sclera in the direction normal to the corneal and scleral surfaces at each point. The range of IOP was set between 5 and 30 mmHg at an interval of 5 mmHg. The boundary of gel was attached to an infinite region to minimize the wave reflections.

The mesh of the cornea and sclera, as well as the gel, were constructed using linear quadrilateral elements (type CPS4R) with size 0.25 mm × 0.25 mm for cornea and 0.5 mm × 0.5 mm for sclera and gel, enhanced with hourglass control and reduced integration, to minimize shear locking and hourglass effects. The vitreous material was meshed using linear triangular acoustic elements (type AC2D3) with size 0.5 mm × 0.5 mm The infinite region was meshed by infinite elements (type CINPE4) (Fig. 2). The dynamic responses of the tissue model to the excitations were solved by the ABAQUS explicit dynamic solver with automatic step size control. Mesh convergence tests were performed so that further refining the mesh did not change the solution significantly.

RESULTS

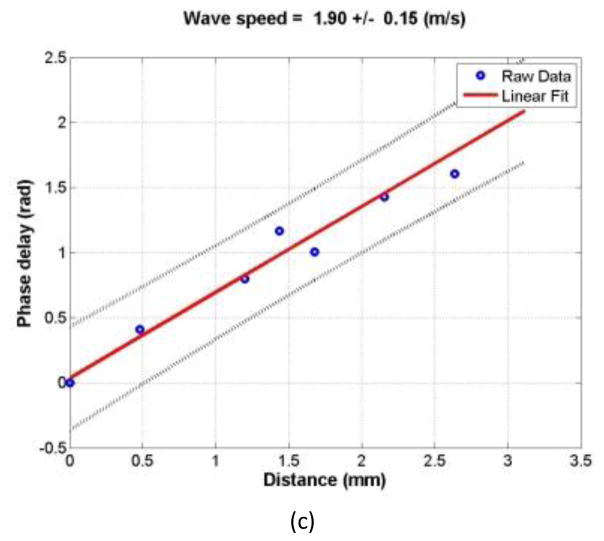

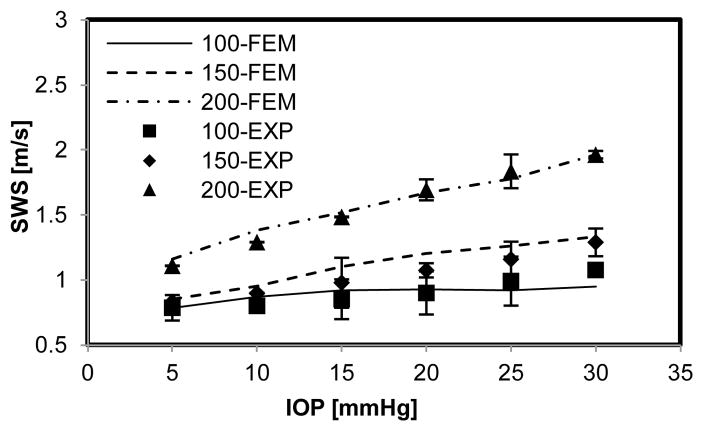

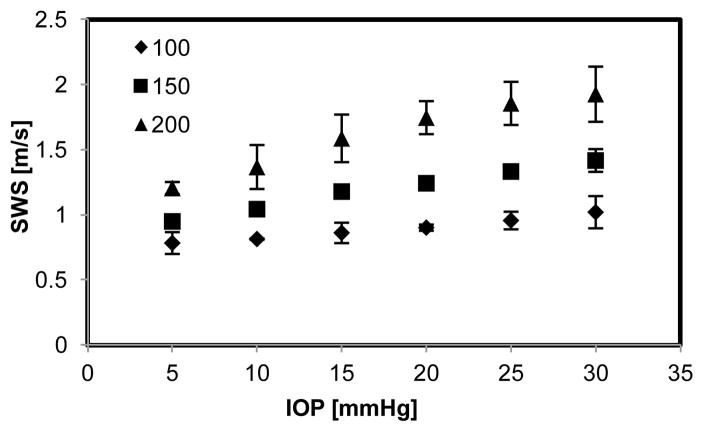

Eight porcine eyes were evaluated in this study. The tissue motion in response to the vibration at different excitation frequencies (100, 150, and 200 Hz) was detected with a high frame rate of 2000 frame/s. The wave speed is shown with 95% confidence interval, mean ± standard error (Fig. 4a, b, c). Figure 7 shows the relationship between wave speed and IOP in a representative experiment. Wave speed in the cornea increased with frequency at each level of IOP, from 0.83 m/s at 100 Hz to 1.96 m/s at 200 Hz (Fig. 7). At the same frequency, the wave speed increased with IOP, from 0.83 to 1.07 m/s at 100 Hz, from 0.86 to 1.29 m/s at 150 Hz and from 1.11 to 1.96 m/s at 200 Hz (Fig. 7).

Figure 4.

Representative phase delay-distance relationships of the cornea at different excitation frequencies. The wave phase change with position, in response to a 0.1 second excitation at 100 (a), 150 (b), and 200 Hz (c), was used to measure the wave speed.

Figure 7.

Comparison between representative experimental measurements and results of corresponding numerical simulations. Error bars represent the standard deviation of 3 measurements.

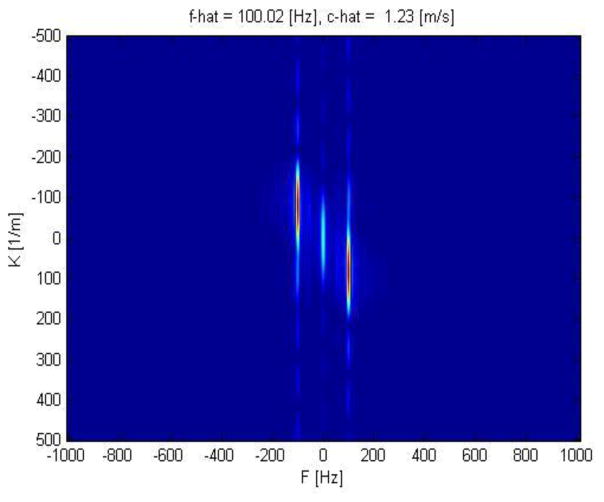

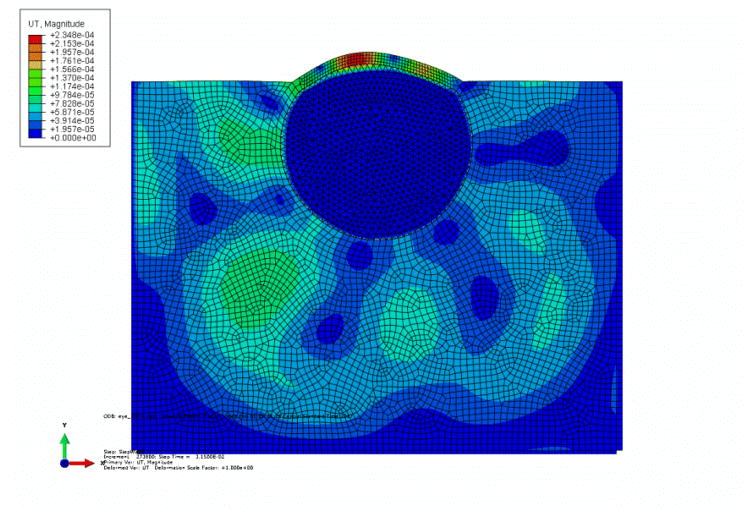

FEM analysis of gelled porcine eyes submerged in water was used to investigate the effects of IOP on the wave speed in cornea. Harmonic excitation was used to propagate waves in the eye ball. The plane waves were excited by vibrating a segment of elements on the sclera perpendicular to the direction of wave propagation. Vitreous humor behaves as a fluid-like material. Acoustic medium is used to model sound propagation problems in usually a fluid in which stress is purely hydrostatic (no shear stress). In this study, we think it is appropriate to model vitreous humor with acoustic medium. As the boundary of the gel was assigned infinite elements, there is no wave reflection in the boundary. The temporal-spatial displacement field of a central segment of cornea was extracted to minimize the influence of boundary effects. It showed that the wave pattern became denser with increasing excitation frequency. 2D-FFT of the displacement versus time data was performed using

| (7) |

where uy(x,t) is the motion of the cornea perpendicular to the excitation as a function of distance from the excitation (x) and time (t). Here, K is the wave number and F is the temporal frequency of the wave. The coordinates of the k-space are the wave number (K) and the frequency (F) [31]. The wave velocity is calculated,

| (8) |

(Fig 6). From the numerical simulation, it showed that the wave speed in the cornea increased with IOP and excitation frequency as well as fit well with the representative experimental measurements (Fig 7). Figure 8 shows the relationship between wave speed and IOP from all experimental measurements. Wave speed in the cornea increased with frequency from 0.73 at 100 Hz to 1.93 m/s at 200 Hz (Fig. 8). At the same frequency, the wave speed increased with IOP from 0.78 to 1.02 m/s at 100 Hz, from 0.92 to 1.42 m/s at 150 Hz and from 1.17 to 1.93 m/s at 200 Hz (Fig. 8).

Figure 6.

Representative k-space from 2D FFT transformation of the cornea at 100 Hz excitation frequency.

Figure 8.

Shear wave speed intraocular pressure relationship of porcine cornea at multiple frequencies (100, 150, and 200 Hz) from 8 experimental measurements. Error bars represent the standard deviation of measurements among 8 specimens.

DISUCCSION

The aim of this study was to understand the relationship between the wave speed in cornea with the IOP in ex vivo procine eye ball models. The level of IOP was adjusted by lifting the relative height between the eye and the water level in the syringe connected via a needle. At each pressure level, a shaker was used to generate a harmonic mechanical vibration on the surface of the eye ball at three frequencies (100, 150, and 200 Hz). The resulting wave propagation in the corneal was noninvasively measured using an ultrasound technique. In this study, the wave propagation in the cornea was measured at three frequencies of 100 Hz, 150 Hz and 200 Hz. The magnitude of 100 Hz wave motion is stronger than the 150 and 200 Hz wave motion. The wave length is inversely proportional to the wave frequency while attenuation rises with the wave frequency. The frequency ranges chosen in this paper consider the wave motion amplitude, spatial resolution and wave attenuation. The wave speed in the cornea was determined by analyzing ultrasound data directly from the cornea. Therefore, the wave speed measurement is local and independent of the location of excitation. A FEM model was built according to the experiments to simulate the wave propagation in the cornea. We found that the wave speed increased with IOP at three different excitation frequencies both from experiments and FEM simulation.

The results from this study are within the range of published results for other species. The wave speed in the porcine cornea was found to be from 0.72 to 1.93, which is similar to values reported for the rabbit cornea, indicating that the wave velocities were 1.14 ± 0.08 m/s and 1.30 ± 0.10 m/s in young and mature rabbit corneas [32]. Shear wave speed of corneas in central regions on ex vivo porcine model was approximately 2.3 m/s at 10 mmHg of IOP [19]. In their study, they placed it in refrigerator prior to testing which may lead to stiffening of cornea and elevation of the magnitude of corneal shear wave speed. The biomechanical properties of human and porcine corneas were evaluated showing that human and porcine corneas have almost the same biomechanical behavior under short and long-term loading, yet human corneas were stiffer than porcine corneas [33]. This research may be useful for us to analyze the in vivo data of the wave speed of cornea between healthy subjects and glaucoma patients. It is difficult to manipulate the IOP in human subjects.

It has been shown that acoustic properties of material are altered with deformation and pressurization, correspondingly changing the wave propagation speed or reflected wave amplitude in the material [34, 35]. Numerous studies have shown the relationship between the echo intensity and the stress or strain experienced by the isolated soft tissues under static or cyclic loading scenarios [36, 37]. Moreover, local speed of wave propagation is directly linked to local stiffness [38]. Corneal stiffness is a function of intraocular pressure and increases with IOP [39]. In patients with glaucoma, the cornea was in compression state due to the increase of IOP. Our results in this ex vivo porcine eye model showed that the wave speed of cornea increased with the IOP. For the glaucoma diagnosis and management, the fine tuning corneal wave speed measurement could also correlate the applanation tonometry with the IOP.

There may be exceptions to this trend due to the numerous disease states. While the present study has emphasized near-physiological condition, the timescale of these tests was less than 1 h. The interpretation of results from this study to glaucoma is questionable. However, the findings of this study have relevance to refractive surgeries and screening tests. Corneal pathologies such as Keratoconus or corneal ectatic disease may lead to abnormal elastic properties in terms of anterior and posterior corneal stiffening before refractive surgery and alter the dynamic response of cornea exhibited as wave propagation in the cornea in response to elevation in IOP [40].

In the ex vivo model, we were able to manipulate the IOP and established the relationship between IOP and wave speed of cornea. Finite element modeling predicted the effects of pressurizing the eye to an IOP of 30 mmHg in terms of wave speed propagation in the cornea. The vitreous humor is a clear gel-like substance that occupies the space behind the lens and in front of the retina at the back of the eye. Given its fluid like material property, the vitreous humor was modelled as an acoustic medium so that the shear wave did not propagate through the vitreous material. The infinite elements assigned on the boundary of gel were used to get rid of the wave reflection, and hence, improve wave speed calculation. It showed that the wave speed increased with IOP at different excitation frequencies, which is in good agreement with the obtained representative experimental measurements (correlation coefficient R = 0.98). In this study, the cornea was assumed as a linear, isotropic, homogeneous, and viscoelastic medium. However, it has been shown that the cornea is largely governed by the structure of the stroma which consists primarily of a lamellae of type-I collagen fibrils embedded in a hydrated proteoglacan matrix. Gradual recruitment of the embedded (load bearing) wavy collagen fibrils with increasing IOP give rise to a nonlinear mechanical behavior of the cornea with a stiffening effect at IOP greater than 60 mmHg [30, 41]. Yet, the range of pressure prescribed in this study covers normal range of IOP and it showed that cornea behaved linearly within a range of IOPs between 2 and 4 kPa [42]. Therefore, it is reasonable to model the cornea as linear viscoelastic material in this study. Moreover, within each lamella, the collagen fibers run parallel to each other, but the alignment direction can vary from one lamella to another. Since the collagen fibers are the stiffest component of the cornea’s structure, the orientation distribution of these fibrils largely governs the mechanical properties of the cornea and leads them to be anisotropic [43, 44]. Future study will develop a structure-based constitutive model incorporating the orientation distribution of collagen fibers in different lamella in the cornea to characterize its dynamic mechanical response to the changes in IOP.

CONCLUSION

In this research, the wave propagation in the cornea was noninvasively measured using an ex vivo porcine eye model. FEM was used to simulate the wave propagation in the corneal according to the experiments. Both the experiments and the FEM analyses showed that the wave speed of cornea increased with IOP at different excitation frequencies ranging from 0.72 to 1.93 m/s. This research may be useful for us to analyze the in vivo data of the wave speed of cornea between healthy subjects and glaucoma patients. This noninvasive method may be useful to measure the in vivo elastic properties of ocular tissues for assessing ocular diseases.

Figure 3.

FEM modeling of the porcine eye balls according to experimental setup.

Figure 5.

Contour of translational displacement field in the eye ball due to harmonic excitation.

Highlight.

We used the ultrasound surface wave elastography technique to noninvasively measure ocular tissue elastic properties in an ex vivo porcine eye model and establish the relationship between the wave speed of cornea and the intraocular pressure.

Experiments were carried out on 10 ex vivo porcine eyes.

Finite element modeling was conducted to validate the effects of IOP on the wave speed measurements in the cornea.

Our results showed that the wave speed in the cornea increased with IOP at different excitation frequencies in both experiments and finite element modeling.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by a NIH R21 grant (EY026095, co-PI AJS, XZ) from the National Eye Institute, and an unrestricted grant to the Department of Ophthalmology from Research to Prevent Blindness. We thank Mrs. Jennifer Poston for editing this manuscript. The authors would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their critical and constructive comments and Dr. Peter A. Lewin, Associate Editor, for his careful handling of this manuscript. We would be able to improve this manuscript with their help.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Congdon N, et al. Causes and prevalence of visual impairment among adults in the United States. Archives of Ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill: 1960) 2004;122(4):477–485. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leske MC. Open-angle glaucoma an epidemiologic overview. Ophthalmic epidemiology. 2007;14(4):166–172. doi: 10.1080/09286580701501931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.7, A.G.I.S. The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration. The AGIS Investigators. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130:429–440. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00538-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Investigators, A. The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration. Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 7. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130(4):429–440. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00538-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandt JD, et al. Central corneal thickness in the ocular hypertension treatment study (OHTS) Ophthalmology. 2001;108(10):1779–1788. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00760-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Midgett DE, et al. The pressure-induced deformation response of the human lamina cribrosa: Analysis of regional variations. Acta Biomaterialia. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.12.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salinas-Navarro M, et al. Ocular hypertension impairs optic nerve axonal transport leading to progressive retinal ganglion cell degeneration. Experimental eye research. 2010;90(1):168–183. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asrani S, et al. Large diurnal fluctuations in intraocular pressure are an independent risk factor in patients with glaucoma. Journal of glaucoma. 2000;9(2):134–142. doi: 10.1097/00061198-200004000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caprioli J, Coleman AL. Intraocular pressure fluctuation: a risk factor for visual field progression at low intraocular pressures in the Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(7):1123–1129. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Musch DC, et al. Intraocular pressure control and long-term visual field loss in the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(9):1766–1773. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.01.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, et al. Quantitative assessment of scleroderma by surface wave technique. Medical engineering & physics. 2011;33(1):31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang X, et al. Noninvasive ultrasound image guided surface wave method for measuring the wave speed and estimating the elasticity of lungs: A feasibility study. Ultrasonics. 2011;51(3):289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y, et al. A non-invasive technique for estimating carpal tunnel pressure by measuring shear wave speed in tendon: a feasibility study. Journal of biomechanics. 2012;45(16):2927–2930. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeng Y, et al. A comparison of biomechanical properties between human and porcine cornea. Journal of biomechanics. 2001;34(4):533–537. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(00)00219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sigal IA, et al. Finite element modeling of optic nerve head biomechanics. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2004;45(12):4378–4387. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feola AJ, et al. Finite Element Modeling of Factors Influencing Optic Nerve Head Deformation Due to Intracranial PressureICP Affects ONH Deformation. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2016;57(4):1901–1911. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-17573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norman RE, et al. Finite element modeling of the human sclera: influence on optic nerve head biomechanics and connections with glaucoma. Experimental eye research. 2011;93(1):4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newson T, El-Sheikh A. Mathematical modeling of the biomechanics of the lamina cribrosa under elevated intraocular pressures. Journal of biomechanical engineering. 2006;128(4):496–504. doi: 10.1115/1.2205372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen TM, et al. In Vivo Evidence of Porcine Cornea Anisotropy Using Supersonic Shear Wave ImagingAnisotropy Measured in Porcine Cornea Using SSI. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2014;55(11):7545–7552. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen TM, et al. Monitoring of Cornea Elastic Properties Changes during UV-A/Riboflavin-Induced Corneal Collagen Cross-Linking using Supersonic Shear Wave Imaging: A Pilot StudyMonitoring of Cornea Elastic Property Changes. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2012;53(9):5948–5954. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanter M, et al. High-resolution quantitative imaging of cornea elasticity using supersonic shear imaging. IEEE transactions on medical imaging. 2009;28(12):1881–1893. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2009.2021471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X, Osborn T, Kalra S. A noninvasive ultrasound elastography technique for measuring surface waves on the lung. Ultrasonics. 2016;71:183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2016.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang X, Qiang B, Greenleaf J. Comparison of the Surface Wave Method and the Indentation Method for Measuring the elasticity of Gelatin Phantoms of Different Concentrations. Ultrasonics. 2011;51(2):157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perez BC, et al. Finite element modeling of the viscoelastic responses of the eye during microvolumetric changes. Journal of biomedical science and engineering. 2013;6(12A):29. doi: 10.4236/jbise.2013.612A005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Callister WD, Rethwisch DG. Materials science and engineering. Vol. 5. John Wiley & Sons; NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bellezza AJ, Burgoyne CF, Hart RT. Viscoelastic characterization of peripapillary sclera: material properties by quadrant in rabbit and monkey eyes. 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Downs JC, et al. Viscoelastic material properties of the peripapillary sclera in normal and early-glaucoma monkey eyes. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2005;46(2):540–546. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris HJ, et al. Correlation between biomechanical responses of posterior sclera and IOP elevations during micro intraocular volume change. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2013;54(12):7215–7222. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ethier CR, Johnson M, Ruberti J. Ocular biomechanics and biotransport. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2004;6:249–273. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.6.040803.140055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woo SY, et al. Nonlinear material properties of intact cornea and sclera. Experimental eye research. 1972;14(1):29–39. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(72)90139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernal M, et al. Material property estimation for tubes and arteries using ultrasound radiation force and analysis of propagating modes. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2011;129(3):1344–1354. doi: 10.1121/1.3533735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang S, Larin KV. Shear wave imaging optical coherence tomography (SWI-OCT) for ocular tissue biomechanics. Optics letters. 2014;39(1):41–44. doi: 10.1364/OL.39.000041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elsheikh A, Alhasso D, Rama P. Biomechanical properties of human and porcine corneas. Experimental eye research. 2008;86(5):783–790. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kobayashi H, Vanderby R. New strain energy function for acoustoelastic analysis of dilatational waves in nearly incompressible, hyper-elastic materials. Journal of Applied Mechanics. 2005;72(6):843–851. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kobayashi H, Vanderby R. Acoustoelastic analysis of reflected waves in nearly incompressible, hyper-elastic materials: forward and inverse problems. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2007;121(2):879–887. doi: 10.1121/1.2427112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pan L, Zan L, Foster FS. Ultrasonic and viscoelastic properties of skin under transverse mechanical stress in vitro. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 1998;24(7):995–1007. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(98)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duenwald S, et al. Ultrasound echo is related to stress and strain in tendon. Journal of biomechanics. 2011;44(3):424–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deffieux T, et al. Assessment of the mechanical properties of the musculoskeletal system using 2-D and 3-D very high frame rate ultrasound. IEEE transactions on ultrasonics, ferroelectrics, and frequency control. 2008;55(10):2177–2190. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Touboul D, et al. Supersonic Shear Wave Elastography for the In Vivo Evaluation of Transepithelial Corneal Collagen Cross-LinkingSSI Evaluation of TE-CXL. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2014;55(3):1976–1984. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spoerl E, Seiler T. Techniques for stiffening the cornea. Journal of Refractive Surgery. 1999;15(6):711–713. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-19991101-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prim DA, et al. A mechanical argument for the differential performance of coronary artery grafts. Journal of the mechanical behavior of biomedical materials. 2016;54:93–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2015.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anderson K, El-Sheikh A, Newson T. Application of structural analysis to the mechanical behaviour of the cornea. Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 2004;1(1):3–15. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2004.0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nejad TM, Foster C, Gongal D. Finite element modelling of cornea mechanics: a review. Arquivos brasileiros de oftalmologia. 2014;77(1):60–65. doi: 10.5935/0004-2749.20140016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shazly T, et al. On the uniaxial ring test of tissue engineered constructs. Experimental Mechanics. 2015;55(1):41–51. [Google Scholar]