Abstract

This research explores the origins of observed differences in time preference across countries and regions. Exploiting a natural experiment associated with the expansion of suitable crops for cultivation in the course of the Columbian Exchange, the research establishes that pre-industrial agro-climatic characteristics that were conducive to higher return to agricultural investment, triggered selection, adaptation and learning processes that generated a persistent positive effect on the prevalence of long-term orientation in the contemporary era. Furthermore, the research establishes that these agro-climatic characteristics have had a culturally embodied impact on economic behavior such as technological adoption, education, saving, and smoking.

JEL Classification: D14, D90, E21, I12, I25, J24, J26, O10, O33, O40, Z1

Keywords: Time preference, Delayed Gratification, Cultural Evolution, Economic Development, Comparative Development, Human Capital, Education, Saving, Smoking

1 Introduction

“Patience is bitter, but its fruit is sweet.”

– Aristotle

The rate of time preference has been largely viewed as a pivotal factor in the determination of human behavior. The ability to delay gratification has been associated with a variety of virtuous outcomes, ranging from academic accomplishments to physical and emotional health.1 Moreover, in light of the importance of long-term orientation for human and physical capital formation, technological advancement, and economic growth, time preference has been widely considered as a fundamental element in the formation of the wealth of nations. Nevertheless, despite the central role attributed to time preference in comparative development, the origins of observed differences in time preference across societies have remained obscured.2

This research explores the coevolution of time preference and economic development in the course of human history, uncovering the origins of the distribution of time preference across countries and regions. It advances the hypothesis, and establishes empirically that geographical variations in the natural return to agricultural investment generated a persistent effect on the distribution of time preference across societies. In particular, exploiting a natural experiment associated with the expansion of suitable crops for cultivation in the course of the Columbian Exchange (i.e., the pervasive exchange of crops between the New and Old World; Crosby, 1972), the research establishes that pre-industrial agro-climatic characteristics that were conducive to higher return to agricultural investment triggered selection, adaptation and learning processes that have had a persistent positive effect on the prevalence of long-term orientation in the contemporary era. Furthermore, the research establishes that these agro-climatic characteristics have had a culturally embodied impact on economic behavior such as technological adoption, human capital formation, the propensity to save, and the inclination to smoke.

The proposed theory generates several testable predictions regarding the effect of the natural return to agricultural investment on the rate of time preference. The theory suggests that in societies in which the ancestral population was exposed to a higher crop yield (for a given growth cycle), the rewarding experience in agricultural investment triggered selection, adaptation and learning processes which have gradually increased the representation of traits for higher long-term orientation in the population. Thus, descendants of individuals who resided in such geographical regions are characterized by higher long-term orientation. Moreover, the theory further proposes that societies that benefited from the expansion in the spectrum of suitable crops in the post-1500 period experienced further gains in the degree of long-term orientation.

The empirical analysis exploits an exogenous source of variation in potential crop yield and growth cycle across the globe to analyze the effect of pre-industrial crop yields on various measures of long-term orientation at the country, region, and individual levels. Consistent with the predictions of the theory, the empirical analysis establishes that indeed higher potential crop yield experienced by ancestral populations during the pre-industrial era, increased the long-term orientation of their descendants in the modern period.

The analysis establishes this result in five layers: (i) a cross-country analysis that accounts for the confounding effects of a large number of geographical controls, the onset of the Neolithic Revolution, as well as continental fixed effects; (ii) a within-country analysis across second-generation migrants that accounts for host country fixed effects, geographical characteristics of the country of origin, as well as migrants’ individual characteristics, such as gender and age; (iii) a cross-country individual-level analysis that accounts for the country’s geographical characteristics as well as individuals’ characteristics, such as income and education; (iv) a cross-regional individual-level analysis that accounts for the region’s geographical characteristics, individuals’ characteristics, and country fixed-effects; and (v) a cross-regional analysis that accounts for the confounding effects of a large number of geographical controls, as well as country fixed-effects.

The research introduces novel measures of potential caloric yield and crop growth cycle for each cell of size 55′ × 5′ (approximately 100km2) across the globe. These measures estimate the potential (rather than actual) caloric yield per hectare per year, under low level of inputs and rain-fed agriculture, capturing cultivation methods that characterized early stages of development, while removing potential concerns that caloric yields reflect endogenous choices that could be affected by time preference. Moreover, the estimates are based on agro-climatic constraints that are largely orthogonal to human intervention, mitigating further possible endogeneity concerns.

The analysis accounts for a wide range of potentially confounding geographical factors that might have directly and independently affected the reward for a longer planning horizon, and hence, the formation of time preference. In particular, it controls for the effects of absolute latitude, average elevation, terrain roughness, distance to navigable water, as well as islands and landlocked regions. Additionally, it accounts for climatic variability, and thus the risk that was associated with fluctuations in food supply, as well as for geographical factors that may have affected trade, and therefore the planning horizon. Furthermore, unobserved geographical, cultural, and historical characteristics at the continental level may have codetermined the global distribution of time preference. Hence, the analysis accounts for these unobserved characteristics by the inclusion of a complete set of continental fixed effects. Moreover, when the sample permits, the analysis accounts for unobserved heterogeneity at the country level by the inclusion of country fixed-effects.

The research exploits a natural experiment associated with the Columbian Exchange (i.e., the expansion of suitable crops for cultivation in the post-1500 period) to mitigate possible concerns relating to: (i) the historical nature of the effect of caloric yield on long-term orientation, (ii) the role of omitted regional characteristics, and (iii) the relative impact of potential sorting of high long-term orientation individuals into high yield regions. First, the Columbian Exchange permits the establishment of the historical nature of the effect of these geographical characteristics as opposed to a potential contemporary link between geographical attributes, development outcomes and the rate of time preference. In particular, restricting attention to crops that were available for cultivation in the pre-1500CE era, permits the identification of the historical nature of the effect.

Second, the Columbian Exchange diminishes concerns about the role of omitted regional characteristics in the observed association. The Columbian Exchange increases the potential crop yield if and only if the potential yield of some newly introduced crop is larger than the potential yield of the originally dominating crop. Hence, a priori, by construction, conditional on the potential pre-1500CE crop yield, the potential assignment of crops associated with this natural experiment ought to be independent of any other attributes of the grid, and the estimated causal effect of the change in potential crop yield is unlikely to be driven by omitted characteristics of the region.

Third, the natural experiment associated with the Columbian Exchange provides the necessary ingredients to assess the relative contributions of the forces of cultural evolution and sorting in the post-1500 era. Indeed, the association between crop yield and time preference could also be attributed to the potential sorting of high long-term individuals into high yield regions. While this sorting process would not affect the nature of the results (i.e., variations in the return to agricultural investment across the globe would still be the origin of the differences in time preference), it would undermine the cultural interpretation of the underlying mechanism. However, if changes in crop yield in the course of the Columbian Exchange affect time preference, once cross-country migrations over this period are accounted for, this effect is unlikely to capture sorting but rather cultural evolution in the post-1500 era.

The first part of the empirical analysis examines the effect of crop yield on the rate of time preference across countries. Using a country-level measure of time preference, as proxied by the index of Long-Term Orientation (Hofstede, 1991), the analysis establishes that, conditional on crop growth cycles, higher pre-industrial caloric yield has a positive effect on Long-Term Orientation in the modern period. The findings are robust to the inclusion of continental fixed-effects, a wide range of confounding geographical characteristics, and the years elapsed since the country transitioned to agriculture. In particular, the estimates suggest that a one-standard deviation increase in potential crop yield increases a country’s Long-Term Orientation by about half a standard deviation.

Moreover, the analysis establishes that crop yield has had primarily a direct effect on time preference rather than an indirect one via the process of development. In particular, accounting for the potential effect of higher crop yield on pre-industrial population density, urbanization, and GDP per capita, and their conceivable persistent effect on contemporary development, does not affect the qualitative results. Furthermore, while effective caloric yield in a given region might have been affected by climatic risks, spatial diversification, and trade, the results are robust to the inclusion of these additional factors into the analysis.

Furthermore, the results suggest that it is the portable, culturally embodied component of the effect of potential crop yield that has a long-lasting effect on the time preference. In particular, the effect on long-term orientation of the crop yield in a population’s ancestral homeland is stronger than the effect of crop yield in its current geographical location. Additionally, the empirical analysis establishes that long-term orientation is the main cultural characteristic determined by potential crop yield. Crop yield has a largely insignificant effect on country-level measures of individualism or collectivism, internal cooperation or competition, tolerance and rigidness, hierarchy and inequality of power, trust, and uncertainty avoidance. Moreover, the effect of crop yield on long-term orientation is not mediated by these cultural characteristics.

The second part of the empirical analysis examines the effect of crop yield in the parental country of origin on the long-term orientation of second-generation migrants. This analysis accounts for host country fixed-effects, mitigating possible concerns about the confounding effect of host country-specific characteristics such as geography, culture and institutions. Moreover, this setting assures that the effect of crop yield on long-term orientation captures cultural elements that have been transmitted across generations, rather than the direct effect of geographical attributes at the country of origin, or the effect of omitted characteristics of the host country (Fernández, 2012; Giuliano, 2007; Guiso et al., 2004). In line with the theory, these findings suggest that higher crop yield in the parental country of origin has a positive, statistically and economically significant effect on the long-term orientation of second-generation migrants, accounting for the confounding effect of individual characteristics, a wide range of geographical attributes of the parental country of origin, as well as the number of years since the parental country of origin transitioned to agriculture.

The third part of the empirical analysis explores the effect of crop yield on individual’s long-term orientation in the World Values Survey, both across countries as well as across regions within a country. The results lend further credence to the proposed theory. In particular, they show that the probability of having long-term orientation increases for individuals who live in a region with higher crop yield. This result is robust to the inclusion of continental fixed effects, and a wide range of confounding geographical as well as individual characteristics.

Finally, the analysis establishes the association between time preference and comparative development in three different layers. First, ethnic groups whose ancestral populations were exposed to higher crop yield in the pre-1500 era had a higher probability of adopting major technological innovations. Second, potential crop yield has a significant effect on saving and smoking behavior of second-generation migrants. Third, higher crop yield is positively associated with investment in human capital across countries.

This research constitutes the first attempt to decipher the biogeographical origins of variations in time preference across the globe. Moreover, it sheds additional light on the geographical and bio-cultural origins of comparative development (e.g., Ashraf and Galor, 2013; Diamond, 1997), the interaction between the evolution of human traits and the process of development (Galor and Moav, 2002; Spolaore and Wacziarg, 2013), and the persistence of cultural characteristics (e.g., Alesina et al., 2013; Belloc and Bowles, 2013; Bisin and Verdier, 2000; Fernández, 2012; Nunn and Wantchekon, 2011).

2 The Model

This section develops a dynamic model that captures the evolution of time preference during the agricultural stage of development – a Malthusian era in which individuals that generated more resources had larger reproductive success (Ashraf and Galor, 2011; Dalgaard and Strulik, 2015; Vollrath, 2011). The evolution of time preference is based on four elements: occupational choice, learning, reproductive success, and intergenerational transmission. First, individuals characterized by higher long-term orientation choose agricultural practices that permit higher but delayed return. Second, the engagement of individuals with long-term orientation in profitable investment ventures mitigates their tendency to discount the future and reinforces their ability to delay gratification. Third, the superior economic outcomes of individuals with long-term orientation increases their reproductive success. Fourth, since time preference is transmitted intergenerationally, the engagement in occupations associated with higher yields and, thus, with higher reproductive success, gradually increases the representation of high long-term orientation individuals in the population.3 Thus, societies characterized by greater return to agricultural investment are also characterized by higher long-term orientation in the long run.

Consider an overlapping-generations economy in an agricultural stage of development. In every time period the economy consists of three-period lived individuals who are identical in all respects except for their rate of time preference. In the first period of life - childhood - agents are economically passive and their consumption is provided by their parents. In the second and third periods of life, individuals have access to identical land-intensive production technologies that allow them to generate income by hunting, fishing, herding, and land cultivation. Some of the available modes of production require investment (e.g., planting) and delayed consumption, and thus, in the absence of financial markets, individuals’ occupational choices reflect their rate of time preference.

2.1 Production

Adult individuals face the choice between two modes of agricultural production: an endowment mode and an investment mode. The endowment mode exploits the existing land for hunting, gathering, fishing, herding, and subsistence agriculture. It provides a constant level of output, R0 > 1, in each of the two working periods of life. The investment mode, in contrast, is associated with planting and harvesting of crops. It requires an investment in the first working period, leaving the individuals with 1 unit of output, but it provides a higher level of resources, R1, in the second working period. In particular, ln(R1) > 2 ln(R0).4

Hence, depending on the choice of production mode, the income stream of member i of generation t (born in period t − 1) in the two working periods of life, (yi,t, yi,t+1), is

| (1) |

2.2 Preferences and Budget Constraints

In each period t, a generation consisting of Lt individuals becomes economically active. Each member of generation t is born in period t−1 to a single parent and lives for three periods. Individuals generate utility from consumption in each period of their working life and from the number of their children. The preference of a member i of generation t is represented by the utility function:

| (2) |

where ci,t and ci,t+1 are the levels of consumption in the first and the second working periods of member i of generation t and ni,t+1 is the individual’s number of children. Furthermore, is individual i’s discount factor, i.e., , where is the rate of time preference of member i of generation t.

In the first working period, in the absence of financial markets and storage technologies, member i of generation t consumes the entire income, yi,t. Hence, consumption of member i of generation t in the first working period, ci,t, is ci,t = yi,t. In the last period, member i of generation t allocates her income, yi,t+1, between consumption, ci,t+1, and expenditure on children, τni,t+1, where τ is the resource cost of raising a child. Hence, the budget constraint of individual i of generation t in the last period of life is τni,t+1 + ci,t+1 = yi,t+1.

2.3 Allocation of Resources between Consumption and Children

Members of generation t allocate their last period income between consumption and child rearing so as to maximize their utility function subject to the budget constraint. Given the homotheticity of preferences, individuals devote a fraction (1 − γ) of their last period income to consumption and a fraction γ to child rearing. Hence, the level of last period consumption and the number of children of member i of generation t, ci,t+1 and ni,t+1, are ci,t+1 = (1 − γ)yi,t+1 and ni,t+1 = γyi,t+1/τ. Given these optimal choices, the level of utility generated by member i of generation t is therefore, , where ζ ≡ γ ln(γ/τ) + (1 − γ) ln(1 − γ)].

2.4 Occupational Choice

Each member i of generation t chooses the desirable mode of production that maximizes life time utility, vi,t. Differences in the desirable mode of production across individuals reflect variations in their rate of time preference.

Given the discount factor, , the life time utility of a member i of generation t, vi,t, under each of the two modes of production is

| (3) |

Hence, since ln(R1) > 2 ln(R0), there exists an interior level of the discount factor, β̂, such that an individual who possesses this discount factor is indifferent between the endowment and the investment modes of production:5

| (4) |

The segmentation of the population between the investment and the endowment modes of production is determined by β̂. In particular, member i of generation t is engaged in the endowment mode if , and in the investment mode if . Furthermore, the threshold level of the discount factor above which individuals are engaged in the investment mode is lower if the return to agricultural investment, R1, is higher, i.e.,

| (5) |

2.5 Time Preference, Income and Fertility

The income stream of member i of generation t in the two working periods, (yi,t, yi,t+1), is determined by the threshold level of the discount factor, β̂. In particular,

| (6) |

Consequently, the number of children of member i of generation t is determined by the threshold level of the discount factor, β̂, such that

| (7) |

Hence, since R1 > R0, the number of children of individuals engaged in the investment mode of production, nI, is larger than that of individuals engaged in the endowment mode, nE, i.e., nI > nE.6

2.6 The Evolution of Time Preference

2.6.1 Evolution of Time Preference within a Dynasty

Suppose that time preference is transmitted across generations. Suppose further that the rate of time preference is affected by the experience of individuals over their life time.7 In particular, individuals who are engaged in the endowment mode of production maintain their inherited time preference, , and transmit it to their offspring, whereas those who are engaged in the investment mode learn to delay gratification and transmit to their offspring an augmented discount factor that reflects this acquired tolerance.8 Unlike the experience of individuals who are engaged in the endowment mode of production that has no impact on their rate of time preference, the experience of individuals who are engaged in the investment mode provides a positive reinforcement to their patience, enhancing their ability to delay gratification.

The degree of long-term orientation transmitted by individuals of the investment type to their offspring, , reflects their inherited time preference, , as well as their acquired patience due to the reward to their investment, R1. The higher is the reward to investment, the more gratifying is the experience with delayed gratification (reflected by higher income and reproductive success), and thus, the higher is the degree of long-term orientation that they transmit to their offspring. Moreover, the higher is the inherited time preference, the higher is the degree of long-term orientation transmitted to the offspring. Indeed, evidence suggests that larger rewards to delayed gratification reinforce the ability to delay gratification even further (Dixon et al., 1998; Mazur and Logue, 1978; Newman and Bloom, 1981; Rung and Young, 2015). Furthermore, children become more long-term oriented when observing a long-term oriented adult (Bandura and Mischel, 1965). Thus, if the contribution of the parental inherited time preference to the long-term orientation of the offspring is characterized by the law of diminishing returns, is an increasing, strictly concave function of the parental inherited time preference, .

Hence, as depicted in Figure 1, the time preference that is inherited by a member i of generation t + 1, , is

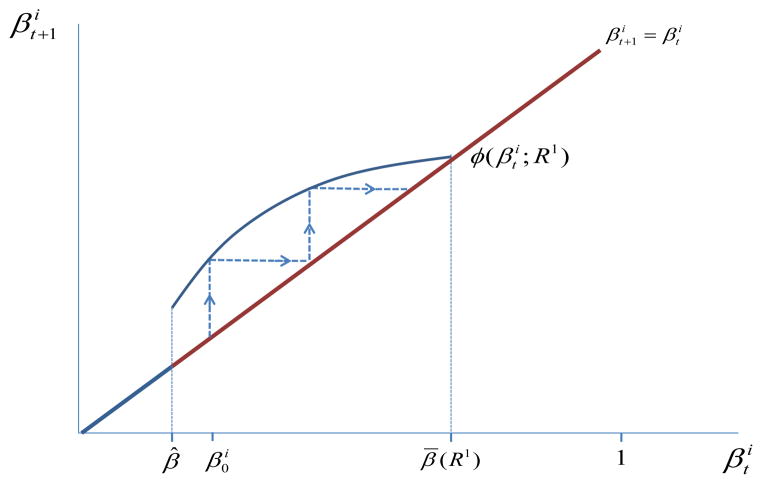

Figure 1.

The Evolution of Time Preference within a Dynasty

| (8) |

where for any ; ϕ( β̂;R1) > β̂; .

As depicted in Figure 1, if the time preference of member i of generation 0 is below the threshold β̂, the individual chooses the endowment mode and the time preference of each member of the individual’s dynasty remains at . In particular, if then . In contrast, if , then member i of generation 0 chooses the investment mode and the evolution of time preference within individual i’s dynasty converges to a unique steady-state level β̄I (R1) > β̂, such that β̄I = ϕ( β̄I ;R1). Hence, .

2.6.2 Evolution of Time Preference Across Generations

Suppose that the time preferences of individuals in period 0 are characterized by a continuous distribution function with support [0, β̄I (R1)] and density .9 Suppose further that the initial size of the population of generation 0 is L0 = 1, i.e.,

| (9) |

Given the threshold level of the discount factor, β̂, above which the investment mode of production is beneficial, the size of the population of generation 0 that is engaged in the endowment mode of production, , and the size of the population of generation 0 that is engaged in the investment mode of production, , are

| (10) |

Since the critical level, β̂, is stationary over time, it follows from (8), that the distribution of across individuals with a discount factor below β̂ is unchanged over time. Additionally, income and therefore the number of children are constant over time for each group (i.e., the endowment type, E, and the investment type, I).

Thus, in generation t, the size of the population of each group is determined by its initial level and the number of children per adult:

| (11) |

where .

The average time preference of generation t, β̄t, is therefore the weighted average of the time preference of the endowment type, , and of the investment type, . The weights are determined by the relative size of the two types in generation t. Hence, the average time preference in society in period t, β̄t, is

| (12) |

where is the fraction of offsprings in generation t who are descendants from individuals engaged in the endowment mode of production in generation 0, i.e.,

| (13) |

Thus, the fraction of individuals of the endowment type declines asymptotically to zero (i.e., ), reflecting their lower reproductive success.

2.7 Steady-State Equilibrium

As the economy approaches a steady-state equilibrium, the fraction of individuals of the endowment type in each generation declines asymptotically to zero. Hence, it follows that the steady-state level of the average time preference in the economy, β̄, is equal to steady-state level of time preference among individuals engaged in the investment mode of production, i.e., β̄ = β̄I (R1) where ∂ β̄/∂R1 > 0.10 Although R0 affects the allocation of the population between the investment and the endowment modes of production, since individuals of the investment type entirely dominate the population asymptotically, and since their time preference converges to the same long-run steady-state level β̄I (R1), which is independent of R0, it follows that the steady-state level of time preference in the economy β̄ is also independent of R0.

Moreover, while an increase in the rate of return to investment, R1, lowers the threshold level of the discount factor above which individuals will chose the investment mode of production, the gradual increase in the ability to delay gratification among individuals of the investment type, and the increase in their relative share in the population (due to higher resources and thus reproductive success) brings about an increase in steady-state level of long-term orientation in society.

Thus, since R0 has no persistent effect on time preference in the long-run, while R1 has a persistent positive effect on the steady-state level of time preference, the empirical investigation of the deep determinants of contemporary time preference ought to focus on variations in R1 across countries and regions, while disregarding potential variations in R0 across the globe.11

2.7.1 Independence of the Steady-State Time Preference from its Initial Distribution

As previously established, the steady-state level of time preference in the economy, β̄, is independent of the initial distribution of time preference in the population as long as the support of the distribution function is [0, β̄]. Thus, changes in the initial distribution can only have temporary effects on time preference, as long as the support of the distribution function remains [0, β̄]. In particular, if sorting occurs, and individuals with high long-term orientation sort themselves into environments in which the return to agricultural investment is higher, this sorting would affect the level of time preference during the transition to the steady state, but would not affect the long run time preference in the economy.

2.7.2 The Effect of an Increase in Crop Yield on Time Preference

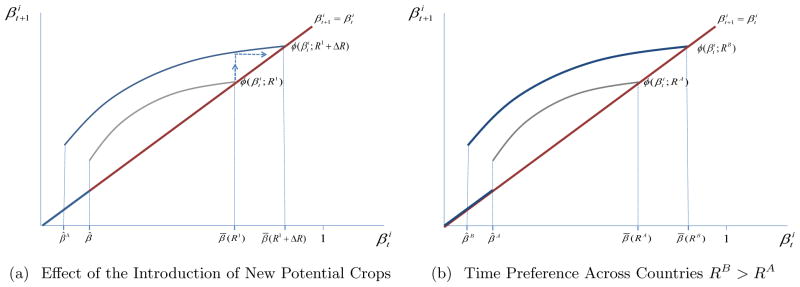

Suppose that after the economy reaches the steady-state equilibrium, β̄I (R1), new crops are introduced and the return to the investment mode increases from R1 to R1+ΔR. As depicted in Figure 2(a) and as follows from (5) and the properties of ϕ(βt;R1), the rise in R1 decreases the threshold level to β̂Δ while shifting ϕ(βt;R1) upwards. Hence, the economy gradually transitions to a higher steady-state equilibrium β̄I (R1+ΔR), and the introduction of new crops increases long-term orientation. Moreover, consider two countries, A and B, identical in all respects except for their return to the investment mode of production. Suppose RA < RB, then as depicted in Figure 2(b), the high return country, B, will have a higher long-term orientation in the steady-state (i.e., β̄(RB) > β̄(RA)).

Figure 2.

Comparative Dynamics

2.7.3 The Effect of an Increase in Crop Growth Cycle on Time Preference

While the waiting period in the basic model is equal to one by construction, a simple extension of the model captures the effect of an increase in the waiting period on the rate of time preference. Suppose that the rate of time preference that is transmitted intergenerationally by parents of the investment type is affected by their inherited time preference, their acquired patience due to the reward to their investment, as well as the length of the delay in the reward that is associated with this investment. In particular, suppose that the subjective reward from this investment, R, is a positive function of the actual resources generated by this investment, R1, and a decreasing function of the waiting period, θ, i.e., R = ξ(R1, θ), where ∂ξ/∂R1 > 0 and ∂ξ/∂θ < 0.12

Generalizing the transmission of the time preference across generations who are engaged in the investment mode, to account for the effect of the duration of the waiting period, it follows that

| (14) |

where ∂ϕ/∂j > 0 for , θ. In particular, holding the subjective reward from investment constant, R, the longer is the waiting period, θ, the higher is the acquired tendency to delay gratification (i.e., ∂ϕ/∂θ > 0).

Thus, an increase in the duration of the waiting period has conflicting effects on the evolution of time preference for individuals of the investment type. In particular,

| (15) |

On the one hand, an increase in the waiting period, holding R1 constant, is equivalent to a decrease in the subjective reward, and hence it reduces the rewarding effect of investment on the individual’s ability to delay gratification. However, the unavoidable increase in the waiting period that is associated with this higher reward, on the other hand, mitigates the aversion from delayed consumption.

Thus, following the analysis in section 2.7 the economy’s average rate of time preference converges to a steady-state level, β̄(R1, θ), where ∂ β̄(R1)/∂R1 > 0 and ∂ β̄(R1, θ)/∂θ ⪌ 0.

2.8 Testable Predictions

The model generates several testable predictions regarding the relationship between crop yield and time preference. First, the theory suggests that across economies identical in all respects except for their return to agricultural investment, the higher the crop yield, the higher the long-term orientation in the long-run. In particular, given the crop growth cycle, the higher is the crop yield, the higher is the average level of long-term orientation. Second, the theory suggests that the expansion in the spectrum of potential crops in the post-1500 period generated an additional increase in the degree of long-term orientation in society, beyond the initial level generated by the pre-1500 crops. Third, the theory suggests that an increase in the crop growth cycle generates conflicting effects on the rate of time preference. On the one hand, an increase in the crop growth cycle, holding the crop yield constant, is equivalent to a reduction in the return on investment, and hence it reduces the effect of rewarding investment experience on the ability to delay gratification. However, the increase in the duration of the investment mitigates the aversion from delayed consumption. Thus, the overall effect is ambiguous.

3 Data and Empirical Strategy

This section presents the empirical strategy developed to analyze the effect of the return to agricultural investment on contemporary variations in the rate of time preference. It introduces novel global measures of historical potential crop yield and growth cycles that are employed in order to examine their effect on a range of proxies for time preference at the individual, regional, and national levels.13

3.1 Identification Strategy

The analysis surmounts significant hurdles in the identification of the causal effect of historical crop yield on long-term orientation. First, long-term orientation may affect the choice of technologies and therefore actual crop yields. Hence, to overcome this concern about reverse causality, this research exploits variations in potential (rather than actual) crop yields associated with agro-climatic conditions that are orthogonal to human intervention.

Second, the results may be biased by omitted geographical, institutional, cultural, or human characteristics that might have determined long-term orientation and are correlated with potential crop yield. Thus, several strategies are employed to mitigate this concern: (i) The analysis accounts for a large set of confounding geographical characteristics (e.g., absolute latitude, elevation, roughness, distance to the sea or navigable rivers, average precipitation, percentages of a country’s area in tropical, subtropical or temperate zones, and average suitability for agriculture). (ii) It accounts for continental fixed effects, capturing unobserved time-invariant heterogeneity at the continental level. (iii) It accounts for confounding individual characteristics (e.g., age, gender, education, religiosity, marital status, and income). (iv) It conducts regional-level analyses of the effect of potential crop yield on long-term orientation, accounting for country fixed effects and thus unobserved time-invariant country-specific factors. (v) It explores the determinants of time preference in second-generation migrants, accounting for the host country fixed effects, and thus time-invariant country-of-birth-specific factors, (e.g., geography, institutions, and culture), thus permitting the identification of the importance of the portable, culturally embodied component of the effect of geography.

Third, geographical attributes that had contributed to crop yield in the past are likely to be conducive to higher crop yield in the present. In particular, the correlation between past crop yield and contemporary time preference may therefore reflect the direct impact of invariant geographical attributes on contemporary economic outcomes that may be correlated with the rate of time preference. To mitigate this concern, this research exploits the potential yield in the pre-1500 period (i.e., prior to the expansion in the spectrum of potential crops in the course of the Columbian Exchange) to identify the persistent effect of historical crop yield on long-term orientation, lending credence to the hypothesis that it is the portable, culturally embodied component of the effect of potential crop yield, rather than persistent geographical attributes that affect time preference.

Fourth, the natural experiment associated with the Columbian Exchange, and the differential assignment of superior crops to different regions of the world, further mitigates potential concerns about omitted variables. In particular, in each grid, the Columbian Exchange brought about an increase in potential crop yield if and only if the potential yield of a newly introduced crop is larger than the potential yield of the originally dominating crop. Hence, a priori, by construction, conditional on the potential pre-1500CE crop yield, the potential assignment of crops associated with this natural experiment ought to be independent of any other attributes of the grid, and the estimated causal effect of the change in potential crop yield is unlikely to be driven by omitted characteristics of the region. Given the positive empirical association between crop yield and growth cycle, this natural experiment is based on the identifying assumption that, conditional on the pre-1500 distribution of potential crop yield and growth cycle, the change in the potential crop yield and growth cycle resulting from the introduction of new crops is distributed randomly, independently of any other attributes of the grid. Appendix B.2 provides supportive evidence for the plausibility of this assumption.

Fifth, the natural experiment associated with the Columbian Exchange sheds light on the contribution of the forces of cultural evolution to the formation of time preference, as opposed to the sorting of high long-term orientation individuals into geographical regions characterized by higher agricultural return. While this sorting process would not affect the nature of the results (i.e., variations in the return to agricultural investment across the globe would still be the origin of the contemporary regional distribution of time preference), this natural experiment provides an essential element that permits the separation of the effect of crop yield on the cultural evolution of time preference from the conceivable sorting of high long-term orientation individuals into regions with high yields. Thus, the differential assignment of superior crops to indigenous populations across the globe in the course of the Columbian Exchange mitigates concerns about sorting. In particular, the causal effect of changes in crop yield is unlikely to capture the effect of sorting in the post-1500 era since the analysis accounts for cross-country migrations over this period.

Finally, superior historical crop-yield could have positively affected past economic outcomes, such as population density, urbanization, and income per capita, which may have affected the observed rate of time preference. Hence, accounting for historical population density, urbanization, as well as GDP per capita, permits the analysis to isolate the cultural component of the effect of potential crop yield from the persistence of past economic prosperity.

3.2 Independent Variables: Potential Crop Yield and Growth Cycle

This subsection introduces the novel global measures of historical potential crop yield and growth cycles that are central to the analysis. These measures properly represent potential crop yield across the globe, as captured by calories (per hectare per year), rectifying deficiencies associated with weight-based measures of agricultural yield. The measures hinge on: (i) estimates of potential crop yield and growth cycle under low level of inputs and rain-fed agriculture – cultivation methods that characterized early stages of development, and (ii) agro-climatic conditions that are orthogonal to human intervention. Furthermore, in light of the expansion of crops amenable for cultivation in the course of the Columbian Exchange (Crosby, 1972), these measures account for pre-1500CE crop yield and growth cycles and their changes in the post-1500 period.

The historical measures of crop yield and growth cycles are constructed based on data from the Global Agro-Ecological Zones (GAEZ) project of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The GAEZ project supplies global estimates of crop yield and crop growth cycle for a variety of crops in grids with cells size of 5′ × 5′ (i.e., approximately 100 km2). For each crop, GAEZ provides estimates for crop yield based on three alternative levels of inputs – high, medium, and low - and two possible sources of water supply – rain-fed and irrigation. Additionally, for each input-water source category, it provides two separate estimates for crop yield, based on agro-climatic conditions that are arguably unaffected by human intervention, and agro-ecological constraints that could potentially reflect human intervention. The FAO dataset provides for each cell in the agro-climatic grid the potential yield for each crop (measured in tons, per hectare, per year). These estimates account for the effect of temperature and moisture on the growth of the crop, the impact of pests, diseases and weeds on the yield, as well as climatic related “workability constraints”. In addition, each cell provides estimates for the growth cycle for each crop, capturing the days elapsed from the planting to full maturity.

The measures employed in the analysis are based on the agro-climatic estimates under low level of inputs and rain-fed agriculture. These restrictions remove potential concerns that the level of agricultural inputs, the irrigation method, and soil quality, reflect endogenous choices that could be potentially correlated with time preference.

In order to capture the nutritional differences across crops, and thus to ensure comparability in the measure of crop yield, each crop’s yield in the GAEZ data (measured in tons, per hectare, per year) is converted into caloric yield (measured in millions of kilo calories, per hectare, per year). This conversion is based on the caloric content of crops, provided by the United States Department of Agriculture Nutrient Database for Standard Reference.14

In light of the expansion in the set of crops that were available for cultivation in each region in the course of the Columbian Exchange, the constructed measures distinguish between the caloric suitability in the pre-1500 period and in the post 1500 period (Figures B.2 and B.3). In particular, the pre-1500 estimates are based on the subset of crops in the GAEZ/FAO data set which were available for cultivation in different regions of the world before 1500CE, as documented in Table A.2 (Crosby, 1972; Diamond, 1997).15 In the post 1500CE period, in contrast, all regions could potentially adopt all crops for agricultural production.16

Based on these estimates, the analysis assigns to each cell the crop with the highest potential yield among the available crops in the pre- and post-1500CE period.17 Thus, the research constructs three sets of measures: (i) the yield and growth cycle for the crop that maximizes potential yield before the Columbian Exchange, (ii) the yield and growth cycle for the crop that maximizes potential yield after Columbian Exchange, and (iii) the changes in the yield and growth cycles of the dominating crop in each cell due to the Columbian Exchange.

Using these measures, the research constructs estimates for the average regional crop yield and the average regional crop growth cycle that reflect the average regional levels of these two variables among crops that maximize the caloric yield in each cell. Since a sedentary community is unlikely to exist in a region in which the caloric yield is zero, the analysis focuses on the averages across cells where the maximum potential crop yield is positive.18

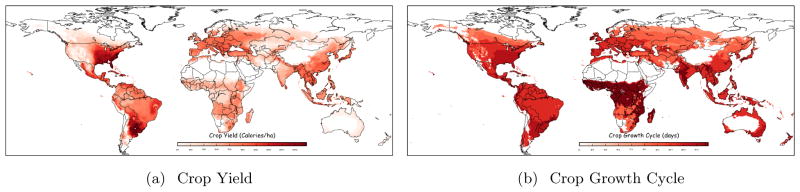

Figure 3 depicts the distribution of potential crop yield and growth cycle across global 5′ × 5′ grids for crops available for cultivation in the pre-1500CE period. Each cell in Figure 3(a) depicts the potential yield (measured in millions of kilo calories, per hectare, per year) generated by the crop with the highest potential yield in that cell. Higher crop yields are marked by darker cells, while lower ones by lighter ones. Similarly, Figure 3(b) depicts the potential crop growth cycle for the crop with the highest potential yield in each cell. Longer growth cycles are marked by darker cells and shorter ones by lighter cells.

Figure 3.

Potential Crop Yield and Growth Cycle for pre-1500CE Crops

As is evident from Figure 3, there are large regional and cross country variations in crop yields. The cross country distribution of pre-1500CE potential crop yield ranges between 0.5 and 18 (millions of kilo calories per hectare per year), has a mean of 7.2 and a standard deviation of 3.2. On the other hand, the distribution of pre-1500CE crop growth cycle has a mean of 134 days, a standard deviation of 18 days and ranges between 80 and 199 days. The correlation between crop yield and growth cycle pre-1500CE is 0.4 (p < 0.01) and post-1500CE is 0.78 (p < 0.01); suggesting that “Trees that are slow to grow, bear the best fruit” (Molière).

The use of potential crop yield as a proxy for actual crop yield overcomes possible concerns about reverse causality.19 Importantly, potential crop yield can serve as a good proxy since it is positively correlated with actual crop yield at the cell level (Figure A.2). Moreover, as established in Appendix B.10, using the Ethnographic Atlas (Murdock, 1967), potential crop yield is positively correlated with the dependence on agriculture, the intensity of agriculture, and the contribution of agriculture to subsistence across ethnic groups.

3.3 Additional Controls

As suggested in the empirical strategy section, crop yield is correlated with other geographical characteristics that may have affected the evolution of time preference. Hence, the analysis accounts for the potential confounding effects of a range of geographical factors such as absolute latitude, average elevation, terrain roughness, distance to sea or navigable rivers, as well as islands and landlocked regions.20 Furthermore, the analysis accounts for continental fixed effects, capturing unobserved continent-specific geographical and historical characteristics that may have codetermined the global distribution of time preference.

The empirical analysis considers the confounding effect of the advent of sedentary agriculture, as captured by the years elapsed since the onset of the Neolithic Revolution, on the evolution of the rate of time preference. The onset of agriculture could have generated conflicting effects on the evolution of time preference. The rise of institutionalized statehood in the aftermath of the transition to agriculture was associated with the taxation of crop yield and thus with a reduction in the incentive to invest (Mayshar et al., 2013; Olsson and Paik, 2013). However, the effect of the Neolithic Revolution on technological advancements and investment in agricultural infrastructure (Ashraf and Galor, 2011; Diamond, 1997) may have countered this adverse effect on the net crop yield. Thus, the effect of the agricultural revolution on the rate of time preference appears a priori ambiguous.

Moreover, the effect of crop yield on long-term orientation would be stronger in regions that experienced the transition to agriculture earlier, provided this evolutionary process had not matured. However, since all countries in the sample experienced the Neolithic Revolution at least 400 years ago, and the vast majority more than 3000 thousand years ago, it is very likely that this culturally driven evolutionary process has matured and its interaction with the years elapsed since the Neolithic Revolution has an insignificant effect on time preference.

4 Crop Yield and Long-Term Orientation (Cross-Country Analysis)

4.1 Baseline Analysis

This section analyzes the empirical relation between crop yield, crop growth cycle, and long-term orientation across countries. In particular, it examines the effect of crop yield on the cultural dimension identified by Hofstede (1991) as Long-Term Orientation (LTO). Hofstede et al. (2010) define Long-Term Orientation as the cultural value that stands for the fostering of virtues oriented toward future rewards, perseverance and thrift.21 For the sample of countries used in this research, there exists a positive relation between this measure of Long-Term Orientation and income per capita, education, and economic growth (Figure A.3).

In order to explore the effect of crop yield and growth cycle on Long-Term Orientation, the following empirical specification is estimated via ordinary least squares (OLS):

| (16) |

where LTOi is the level of Long-Term Orientation in country i as identified by Hofstede et al. (2010), crop yield and crop growth cycle of country i are the post-1500CE measures constructed in the previous section, Xij is geographical characteristic j of country i, YSTi is the number the years elapsed since country i transitioned to agriculture, {δc} is a complete set of continental fixed effects, and εi is the error term of country i. The theory suggests that β1 > 0.

The effect of potential crop yield and growth cycle on Long-Term Orientation based on the full set of available crops in the contemporary era are shown in Table 1. Column (1) establishes the relationship between crop yield and Long-Term Orientation, accounting for continental fixed effects and therefore for unobserved time-invariant omitted variables at the continental level. The estimated coefficient is positive and statistically significant at the 1% level. In particular, an increase of one standard deviation in crop yield increases Long-Term Orientation by 0.3 standard deviations (i.e., 7.4 percentage points).

Table 1.

Crop Yield, Growth Cycle, and Long-Term Orientation

| Long-Term Orientation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Whole World | Old World | |||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Crop Yield | 7.43*** (2.48) | 9.84*** (2.88) | 9.06*** (2.62) | 9.46*** (3.41) | −7.07 (6.41) | 13.26*** (2.55) | 15.23*** (3.58) | |

| Crop Growth Cycle | −0.70 (3.96) | 10.47 (10.99) | −3.18 (4.03) | |||||

| Crop Yield (Ancestors) | 13.31*** (2.94) | 19.55*** (6.69) | ||||||

| Crop Growth Cycle (Ancestors) | −3.15 (3.52) | −13.41 (11.26) | ||||||

| Absolute Latitude | 2.85 (4.05) | 1.88 (3.85) | 1.68 (4.33) | 3.99 (3.63) | 4.72 (3.88) | 4.76 (4.15) | 3.87 (4.71) | |

| Mean Elevation | 4.98* (2.87) | 5.97** (2.96) | 6.09** (3.03) | 5.96** (2.46) | 5.47** (2.54) | 4.58 (2.99) | 4.87 (3.03) | |

| Terrain Roughness | −6.24** (2.51) | −5.72** (2.75) | −5.72** (2.75) | −6.72*** (2.49) | −6.56** (2.54) | −6.40** (2.83) | −6.29** (2.82) | |

| Neolithic Transition Timing | −6.46** (2.87) | −6.31** (3.06) | −3.24 (7.22) | −4.75* (2.60) | −4.08 (2.66) | |||

| Neolithic Transition Timing (Ancestors) | −4.31* (2.30) | −1.70 (6.24) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Continent FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Additional Geographical Controls | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Old World Sample | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Adjusted-R2 | 0.54 | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.66 | 0.65 | 0.61 | 0.61 |

| Observations | 87 | 87 | 87 | 87 | 87 | 87 | 72 | 72 |

Notes: The table establishes the positive, statistically, and economically significant effect of a country’s potential crop yield, measured in calories per hectare per year, on its level of Long-Term Orientation measured on a scale of 0 to 100, accounting for continental fixed effects and other geographical characteristics. Additional geographical controls include distance to coast or river, and landlocked and island dummies. All independent variables have been normalized by subtracting their mean and dividing by their standard deviation. Thus, all coefficients can be compared and show the effect of a one standard deviation increase in the independent variable on Long-Term Orientation. Heteroskedasticity robust standard error estimates are reported in parentheses;

denotes statistical significance at the 1% level,

at the 5% level, and

at the 10% level, all for two-sided hypothesis tests.

Column (2) accounts for other confounding geographical characteristics of the country such as absolute latitude, mean elevation above sea level, terrain roughness, mean distance to the sea or a navigable river, and dummies for being landlocked or an island. Accounting for the effects of geography and unobserved continental heterogeneity, a one standard deviation increase in crop yield increases Long-Term Orientation by 9.8 percentage points or equivalently 0.4 standard deviations. This is the largest association of any of the variables included in the analysis. Moreover, most geographical characteristics have no significant association with Long-Term Orientation.

Column (3) considers the confounding effect of the advent of sedentary agriculture, as captured by the years elapsed since the onset of the Neolithic Revolution, on the evolution of the rate of time preference. Reassuringly, the coefficient on crop yield remains stable and statistically significant at the 1% level and implies that a one standard deviation increase in crop yield increases Long-Term Orientation by 9.1 percentage points. The estimated coefficients of other geographical characteristics remain smaller than the effect of crop yield. Additionally, the effect of the years elapsed since the onset of the Neolithic Revolution is negative and statistically significant at the 5% level. In particular, a one standard deviation increase in the number of years since the onset of the Neolithic Revolution (approximately 2350 years) is associated with a decrease of 6.5 percentage points in Long-Term Orientation.

Column (4) accounts for the effect of crop growth cycle on Long-Term Orientation. As suggested by the theory the coefficient on crop yield remains positive and statistically significant at the 1% level, while the coefficient on crop growth cycle is negative, though not statistically different from zero. The estimated coefficient on crop yield remains stable implying that a one standard deviation increase on crop yield increases Long-Term Orientation by 9.5 percentage points.

The proposed hypothesis suggests that the evolution of time preference reflected the exposure of the ancestral population of contemporary societies to higher crop yield. However, migration of individuals in the post-1500 period could generate a mismatch between the crop yield in the country of residence and the crop yield to which the ancestral populations were exposed. Thus, in order to analyze the effect that migration might have had on the estimated effect, column (5) adjusts crop yield, growth cycle, and timing of transition to agriculture to account for the ancestral composition of the contemporary populations (Putterman and Weil, 2010). These ancestry adjusted measures capture the geographical attributes that existed in the homelands of the ancestral populations of each contemporary country. In particular, for each country the adjusted crop yield is the weighted average of crop yield in the countries where the ancestral populations resided. This adjustment permits the analysis to capture the culturally embodied transmission rather than the direct effect of geography.

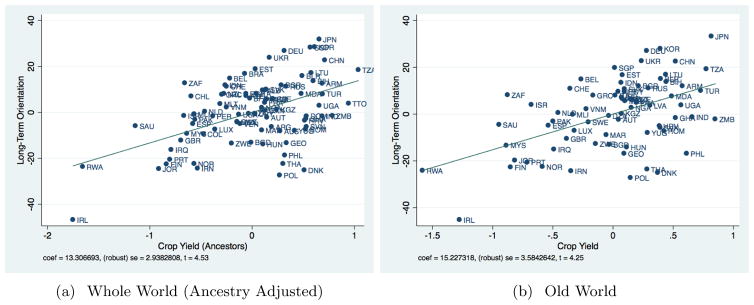

As established in column (5), the estimated effect of crop yield is 50% larger, reinforcing the notion that the effect of these geographical attributes is culturally embodied. Moreover, as reported in column (6), in a horse race between the ancestry adjusted and unadjusted measures of crop yield and crop growth cycle, only the adjusted measure of crop yield remains economically and statistically significant, reinforcing the hypothesis about the culturally embodied transmission. The estimates in column (5) imply that accounting for continental fixed effects, other geographical characteristics, the ancestry adjusted timing of transition to the Neolithic Revolution, and the ancestry adjusted crop growth cycle, a one standard deviation increase in the crop yield experienced by the ancestral populations of contemporary countries increases current levels of Long-Term Orientation by 0.53 standard deviations (i.e., 13.3 percentage points). Figure 4(a) depicts the partial correlation plot for the specification in column (5).

Figure 4.

Potential Crop Yield and Long-Term Orientation

Note: This figure illustrates the positive effect of potential crop yield on Long-Term Orientation in the whole world (panel a) and the Old World (panel b). The depicted relationships account for the full set of controls in Table 1.

Additionally, columns (7) and (8) establish that the effect of crop yield on Long-Term Orientation is much larger in the Old World, where intercontinental migration and population replacement were less prevalent. One standard deviation increase in crop yield increases Long-Term Orientation by 13.3 and 15.2 percentage points (0.52 and 0.60 standard deviations), respectively. Figure 4(b) depicts the partial correlation between crop yield and Long-Term Orientation for the specification in column (8).

4.2 Natural Experiment: The Columbian Exchange

The natural experiment generated by the Columbian Exchange provides an essential ingredient in overcoming three unsettled issues regarding the observed association between crop yield and Long-Term Orientation: (a) the role of omitted variables at the country level, (b) the comparative role of cultural evolution and the sorting of high long-term orientation individuals into high yield regions, and (c) the historical, as opposed to the contemporary, link between crop yield and long-term orientation.

In order to explore the effect of crop yield, growth cycle, and their changes on Long-Term Orientation, the following empirical specification is estimated via ordinary least squares (OLS):

| (17) |

where LTOi is the level of Long-Term Orientation in country i, yieldi and growth cyclei are the pre-1500CE levels of these measures, Δyieldi and Δcyclei are their post-1500 changes generated in the course of the Columbian Exchange, Xij is geographical characteristic j of country i, YSTi is the number of years elapsed since country i transitioned to agriculture, {δc} is a complete set of continental fixed effects, and εi is the error term of country i. The theory suggests that and .

Table 2 examines the effect of pre-1500CE crop yield and growth cycle and their changes in the course of the Columbian Exchange on Long-Term Orientation. Accounting for continental fixed effects column (1) establishes that a one standard deviation increase in the pre-1500CE crop yield generates a 5.7 percentage points increase in Long-Term Orientation. Column (2) shows that the expansion of crops available for cultivation in the post-1500CE period generates an additional increase in Long-Term Orientation. In particular, a one standard deviation increase in pre-1500 crop yield increases Long-Term Orientation by 6 percentage points, while the change in crop yield increases it by 7.9 percentage points. Column (3) establishes that accounting for the confounding effects of additional geographical characteristics and the time elapsed since the transition to agriculture increases the estimated effect of pre-1500 crop yield and its change in the post-1500CE period. Column (4) accounts for the effect of pre-1500CE growth cycle and its change in the course of the Columbian Exchange. Reassuringly, the effect of pre-1500CE crop yield and its change are higher than before and remain statistically and economically significant. Column (5) accounts for migration and population replacement adjusting for the ancestral composition of contemporary populations. The estimated effect of pre-1500CE crop yield increases by 25%, reinforcing the notion that the effect of these geographical attributes is culturally embodied. Moreover, as reported in column (6), in a horse race between the ancestry adjusted and unadjusted measures of crop yield and crop growth cycle and their changes, only the adjusted level of pre-1500 crop yield remains economically and statistically significant, reinforcing the hypothesis that the effect of crop yield on Long-Term Orientation operated through cultural transmission. Columns (7) and (8) establish that the effect of crop yield on Long-Term Orientation is much larger in the Old World, where intercontinental migration and population replacement were less prevalent. In particular, mitigating the effect of measurement errors, the estimated effects in column (8) are larger, implying that a one standard deviation increase in pre-1500CE crop yield increases Long-Term Orientation by 15.2 percentage points, while a one standard deviation increase in the change in yield in the course of the Columbian Exchange increases Long-Term Orientation by 10.5 percentage points.

Table 2.

Crop Yield, Growth Cycle, and Long-Term Orientation: Exploiting the Columbian Exchange

| Long-Term Orientation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Whole World | Old World | |||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Crop Yield (pre-1500) | 5.67** (2.40) | 5.98*** (2.09) | 7.28*** (2.29) | 8.82*** (3.13) | −3.76 (5.41) | 12.23*** (2.84) | 15.21*** (3.51) | |

| Crop Yield Change (post-1500) | 7.88** (3.08) | 8.77*** (2.69) | 9.83*** (3.11) | 2.50 (7.00) | 7.95*** (2.56) | 10.53*** (3.30) | ||

| Crop Growth Cycle (pre-1500) | −3.77 (4.17) | 4.46 (10.20) | −7.65 (4.80) | |||||

| Crop Growth Cycle Change (post-1500) | 0.16 (1.90) | −8.61 (6.85) | 0.31 (1.73) | |||||

| Crop Yield (Ancestors, pre-1500) | 10.56*** (2.35) | 14.05*** (5.01) | ||||||

| Crop Yield Change (Anc., post-1500) | 9.86*** (2.28) | 8.60 (5.68) | ||||||

| Crop Growth Cycle (Anc., pre-1500) | −7.31** (3.59) | −12.61 (10.09) | ||||||

| Crop Growth Cycle Ch. (Anc., post-1500) | 0.77 (1.60) | 8.74 (6.08) | ||||||

| Neolithic Transition Timing | −7.05** (2.90) | −6.15** (2.96) | 5.84 (7.46) | −5.06* (2.73) | −3.46 (2.77) | |||

| Neolithic Transition Timing (Anc.) | −4.27* (2.23) | −8.11 (6.14) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Continent FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Geographical Controls | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Old World Sample | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Adjusted-R2 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.61 | 0.62 |

| Observations | 87 | 87 | 87 | 87 | 87 | 87 | 72 | 72 |

Notes: The table establishes the positive, statistically, and economically significant effect of a country’s pre-1500CE potential crop yield and the post-1500CE change in this yield in the course of the Columbian Exchange on the country’s level of Long-Term Orientation, accounting for continental fixed effects and other geographical characteristics. Geographical controls include absolute latitude, mean elevation, terrain roughness, distance to coast or river, and landlocked and island dummies. All independent variables have been normalized by subtracting their mean and dividing by their standard deviation. Thus, all coefficients can be compared and show the effect of a one standard deviation increase in the independent variable on Long-Term Orientation. Heteroskedasticity robust standard error estimates are reported in parentheses;

denotes statistical significance at the 1% level,

at the 5% level, and

at the 10% level, all for two-sided hypothesis tests.

4.2.1 Mitigating Concerns about Omitted Variables

The natural experiment associated with the Columbian Exchange, and the differential assignment of superior crops to different regions of the world, mitigates potential concerns about omitted variables. In particular, this natural experiment is based on the identifying assumption that, conditional on the pre-1500 distribution of potential crop yield and growth cycle, the change in the potential crop yield and growth cycle resulting from the introduction of new crops is distributed randomly, independently of any other attributes of the grid. More formally, the identifying assumption is that the changes in crop yield and growth cycle, conditional on their pre-1500 levels, are orthogonal to the error term ∊i in equation (17). Appendix B.2 provides supportive evidence for the plausibility of this assumption.

Moreover, using statistics on the selection on observables and unobservables (Altonji et al., 2005; Bellows and Miguel, 2009; Oster, 2014), Tables B.8 and B.14 establish that the degree of omitted variable bias is very low and is unlikely to explain the size of the estimated effect of crop yield and its change. In particular, omitted factors would need to be 3–6 times more strongly correlated with the change in crop yield than all the controls accounted for in order to explain the estimated effect of the change in crop yield on Long-Term Orientation. Similarly, omitted factors would need to be at least 50 percent more strongly negatively correlated with pre-1500 yield in order to explain the size of the coefficient, suggesting that the estimated coefficient should be considered a lower bound of the true effect. Indeed, in all specifications, the bias-adjusted estimated effect of pre-1500 crop yield is strictly positive and larger than the OLS estimate (Oster, 2014).

4.2.2 Sorting vs. Cultural Evolution

This subsection examines the relative contributions of cultural evolution and sorting to the observed relation between crop yield, growth cycle and Long-Term Orientation. The theory highlights the effect of crop yield on the gradual propagation of traits for higher long-term orientation due to the forces of natural selection and cultural evolution. A-priori, however, the positive association between higher crop yield and Long-Term Orientation could have been partly generated by the sorting of high long-term individuals into high yield regions. While the existence of this sorting process would not affect the nature of the results (i.e., variations in the return to agricultural investment across the globe would still be the origin of the spatial differences in time preference), it would affect the interpretation of the results, regarding the comparative role of cultural evolution in this association.

The natural experiment associated with the Columbian Exchange provides the necessary ingredients to assess the relative contributions of the forces of cultural evolution and sorting in the post-1500 era. While sorting could have been an important force in the pre-1500 period, and in particular during the demic diffusion of the Neolithic Revolution across the globe, the results in Tables 2 and B.11 suggest that it is an insignificant force in the post-1500 period. Moreover, as suggested in the theory, if during the thousands of years elapsed since the onset of the Neolithic Revolution (and prior to the Columbian Exchange), the composition of time preference in each region had plausibly reached the proximity of its long-run steady-state equilibrium (and is thus independent of the initial composition of time preference in the region), then sorting and its effect on the initial distribution of time preference would have had a negligible effect on Long-Term Orientation in the pre-1500 period and the relationship between Long-Term Orientation and crop yield, even in the pre-1500 era, would reflect primarily the forces of either cultural or genetic evolution.

This research employs two strategies to establish the importance of cultural evolution relative to sorting in the determination of Long-Term Orientation in the post-1500 period. First, restricting the analysis to countries that were not subjected to large inflows of migrants in the post-1500 period, but nevertheless experienced a change in their crop yield and growth cycle, the research isolates the effects of cultural evolution on Long-Term Orientation from the potential effect of sorting.22 In particular, restricting the analysis to the Old World sample, as established in columns (7) and (8) of Table 2, changes in crop yield in the post-1500 period have a positive and significant effect on Long-Term Orientation. Additionally, for a sample of countries where at least 90 percent of the population descends from individuals that were native to the location in 1500, the positive effect of changes in crop yield in the post-1500 period on Long-Term Orientation is even larger (Table B.11). These results suggest that cultural evolution is a significant force in the determination of Long-Term Orientation during the post-1500 period.

Second, comparing the whole world sample, where migration is prevalent, to the previous sub-samples, in which migration is low, facilitates the analysis of the potential contribution of sorting to Long-Term Orientation. In particular, if sorting had taken place, high long-term orientation individuals would have migrated to locations with higher yields, and thus, one would observe a stronger association between changes in the crop yield and Long-Term Orientation in the whole world sample than the one observed in the subsamples with low migration. But, as established in columns (4) and (5) of Table 2, the estimated effect of changes in crop yield in the whole world sample is smaller than the estimated effect in the Old World sample as well as in the native sample, even after adjusting for the ancestral composition of contemporary populations. This suggests that sorting played an insignificant role in the determination of Long-Term Orientation in the whole world sample during the post-1500 era.

4.2.3 Accounting for the Persistence of Historical Geographical Attributes

This subsection examines the relative contributions of cultural evolution and the persistence of geographical characteristics in the formation of Long-Term Orientation. The natural experiment associated with the Columbian Exchange provides the necessary ingredients to assess the relative contribution of historical geographical characteristics to the formation of Long-Term Orientation, as opposed to a potential contemporary association between geographical attributes, development outcomes and the rate of time preference.

Focusing on crops that were available for cultivation in pre-1500CE era permits the identification of the historical nature of the effect. Indeed, as established in Table 2, crop yield in the pre-1500 era has a significant effect on the contemporary level of long-term orientation. Moreover, the effect of historical yields remains in effect even after accounting for migration, suggesting again that this trait is culturally embodied. Furthermore, constraining the analysis to cells in which the dominating crop had changed in the post-1500CE period, and thus abstracting from cells in which the dominating contemporary crops are indistinguishable from the historical ones, does not qualitatively alter the results (Appendix B.2).

4.3 Robustness

4.3.1 Persistence of Development

This subsection establishes that the effect of crop yield on Long-Term Orientation is unaffected by the plausible effect of agricultural productivity on pre-industrial population density, urbanization, and GDP per capita, and their conceivable persistent effect on contemporary development (Ashraf and Galor, 2011; Nunn and Qian, 2011). In particular, accounting for historical population density as well as urbanization and GDP per capita permits the analysis to isolate the cultural component of the effect of potential crop yield, from the persistent consequences of past economic prosperity.

Table 3 establishes that accounting for historical levels of population density, urbanization, and GDP per capita, the coefficients on crop yield and its change in the post-1500 period remain stable and statistically and economically significant.23 Furthermore, the partial and semi-partial R2 analysis suggest that the explanatory power of crop yield and growth cycle, as well as their changes, is significantly larger than alternative geographical and economic factors.24

Table 3.

Crop Yield, Growth Cycle, and Long-Term Orientation: Accounting for the Persistence of Development

| Long-Term Orientation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Population Density | Urbanization | GDP per capita | ||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||

| 1500CE | 1500CE | 1800CE | 1870CE | 1913CE | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Crop Yield (Ancestors, pre-1500) | 11.05*** (2.53) | 11.52*** (2.33) | 10.01*** (3.68) | 11.08*** (3.68) | 11.54*** (3.18) | 11.54*** (3.22) | 14.19*** (5.08) | 12.66** (5.02) |

| Crop Yield Change (post-1500) | 10.76*** (2.89) | 10.40*** (2.78) | 8.77** (3.35) | 9.96*** (3.35) | 10.05*** (3.23) | 10.22*** (3.37) | 15.55*** (3.22) | 14.92*** (3.29) |

| Crop Growth Cycle (Anc., pre-1500) | −8.06* (4.06) | −10.43*** (3.63) | −5.06 (5.28) | −7.30 (5.37) | −8.60* (4.68) | −8.75* (4.84) | −12.58* (6.44) | −10.28 (6.46) |

| Crop Growth Cycle Ch. (post-1500) | −0.46 (1.72) | −1.06 (1.84) | 1.06 (2.91) | 0.55 (2.95) | 0.07 (2.37) | 0.03 (2.41) | 2.14 (3.38) | 3.31 (3.35) |

| Population density in 1500 CE | 3.76** (1.86) | |||||||

| Urbanization rate in 1500 CE | 1.90 (2.24) | |||||||

| Urbanization rate in 1800 CE | −0.57 (1.22) | |||||||

| GDP per capita 1870 | 10.57*** (3.65) | |||||||

| GDP per capita 1913 | 10.99*** (3.53) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Partial R2 | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Crop Yield (Anc., pre-1500) | 0.23*** | 0.25*** | 0.11*** | 0.12*** | 0.20*** | 0.20*** | 0.25*** | 0.21** |

| Crop Yield Change (post-1500) | 0.16*** | 0.16*** | 0.08** | 0.09*** | 0.12*** | 0.12*** | 0.27*** | 0.26*** |

| Crop Growth Cycle (Anc., pre-1500) | 0.06* | 0.09*** | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06* | 0.06* | 0.12* | 0.09 |

| Crop Growth Cycle Ch. (post-1500) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Population density in 1500 CE | 0.05** | |||||||

| Urbanization rate in 1500 CE | 0.01 | |||||||

| Urbanization rate in 1800 CE | 0.00 | |||||||

| GDPpc 1870 | 0.16*** | |||||||

| GDPpc 1913 | 0.17*** | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Semi-Partial R2 | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Crop Yield (Anc., pre-1500) | 0.08*** | 0.09*** | 0.04*** | 0.04*** | 0.07*** | 0.07*** | 0.09*** | 0.07** |

| Crop Yield Change (post-1500) | 0.05*** | 0.05*** | 0.03** | 0.03*** | 0.04*** | 0.04*** | 0.10*** | 0.09*** |

| Crop Growth Cycle (Anc., pre-1500) | 0.02* | 0.03*** | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02* | 0.02* | 0.04* | 0.03 |

| Crop Growth Cycle Ch. (post-1500) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Population density in 1500 CE | 0.01** | |||||||

| Urbanization rate in 1500 CE | 0.00 | |||||||

| Urbanization rate in 1800 CE | 0.00 | |||||||

| GDPpc 1870 | 0.05*** | |||||||

| GDPpc 1913 | 0.05*** | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Continental FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Geographical Controls & Neolithic | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adjusted-R2 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.59 | 0.59 |

| Observations | 87 | 87 | 65 | 65 | 79 | 79 | 50 | 50 |

Notes: The table establishes the positive, statistically, and economically significant effect of a country’s pre-1500CE potential crop yield, growth cycle and their post-1500CE changes in these values in the course of the Columbian Exchange on the country’s level of Long-Term Orientation, accounting for continental fixed effects, other geographical characteristics, and pre-industrial development (population density, urbanization rates, and GDP per capita). All independent variables have been normalized by subtracting their mean and dividing by their standard deviation. Thus, all coefficients can be compared and show the effect of a one standard deviation increase in the independent variable on Long-Term Orientation. Heteroskedasticity robust standard error estimates are reported in parentheses;

denotes statistical significance at the 1% level,

at the 5% level, and

at the 10% level, all for two-sided hypothesis tests.

4.3.2 Alternative Cultural Characteristics

This subsection establishes that the effect of potential crop yield on Long-Term Orientation does not capture its effect on a wide range of other cultural characteristics proposed by Hofstede (1991), such as Uncertainty Avoidance (the level of tolerance and rigidness of society), Power Distance (the level of hierarchy and inequality of power), Individualism (how individualistic as opposed to collectivistic a society is), and Masculinity (level of internal cooperation or competition).25 In particular, as demonstrated in Table 4, pre-1500CE crop yield and its change do not affect this range of cultural characteristics, while accounting for their potential confounding effects does not alter the effect of pre-1500CE crop yield and its change on Long-Term Orientation.26 Furthermore, while crop yield has a marginally significant negative effect on Generalized Trust (Table 4) accounting for Trust does not alter the effect of crop yield on Long-Term Orientation.

Table 4.

Crop Yield, Growth Cycle, and Other (Cultural) Traits

| Cultural Indices | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Long-Term Orientation (1) |

Trust (2) |

Individualism (3) |

Power Distance (4) |

Cooperation (5) |

Uncertainty Avoidance (6) |

|

| Crop Yield (Ancestors, pre-1500) | 9.43*** (3.46) | −7.76* (4.01) | −11.85 (7.15) | 5.76 (6.62) | −8.11 (6.58) | 3.70 (6.42) |

| Crop Yield Change (Anc., post-1500) | 8.15*** (2.09) | −0.62 (3.55) | −3.12 (2.85) | 1.77 (2.63) | −1.48 (2.45) | −0.17 (2.33) |

| Crop Growth Cycle (Anc., pre-1500) | −6.60* (3.82) | 0.64 (4.95) | 3.27 (5.64) | −1.54 (6.57) | 4.79 (6.73) | 5.04 (6.43) |

| Crop Growth Cycle Change (Anc., post-1500) | −1.07 (1.76) | 1.94 (2.11) | −3.70 (3.18) | −0.69 (3.02) | 2.99 (2.53) | −0.11 (3.32) |

|

| ||||||

| Continental FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| All Geographical Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Agr. Suitability & Neolithic | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adjusted-R2 | 0.70 | 0.45 | 0.67 | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.59 |

| Observations | 85 | 83 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |