Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) kills over 1.5 million people per year despite the available anti-TB drugs. The emergence of drug-resistant TB poses a major threat to public health and prompts for an urgent need for new and more effective drugs. The long duration needed to treat TB by the current TB drugs, which target the essential cellular activities, inevitably leads to the emergence of drug-resistance. The response regulator PhoP, an essential virulence factor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB), is an attractive target for developing novel anti-TB drugs. Guided by the crystal structure of the PhoP-DNA complex, we designed and developed a robust high-throughput screening assay to identify PhoP inhibitors that disrupt the PhoP-DNA binding. The assay was based on Foster resonance energy transfer (FRET) between a Cy3 label on the DNA and a Cy5 on PhoP. From a test screening of ~6,000 bioactive compounds and approved drugs, three active compounds were identified that directly bound to PhoP and inhibited the PhoP-DNA interactions. These three PhoP inhibitors can be further developed to improve potency and are useful to study the mechanism of inhibition. In addition, our results demonstrated that this FRET-based PhoP-DNA binding assay is valid for additional compound library screening to identify new leads for developing novel TB drugs that targeting the virulence of MTB.

Keywords: High-throughput screening, PhoP inhibitors, tuberculosis, FRET, protein-DNA complex, TB drugs

1. INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis (TB) has remained one of the most serious threats to public health, due to the increasing prevalence of multi-drug resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) TB and the synergy of TB with HIV infection [1]. Each year, over 9 million new TB cases are reported, and 1.5 million people died from TB [2]. The global health security risk of TB and grave consequences to those affected prompted World Health Organization (WHO) to call for drug-resistant TB to be addressed as a public health crisis. Because there is no consistently effective TB vaccine available [3–5], new therapeutics effective against drug-resistant strains are urgently needed.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB), the causative agent of TB, is able to adapt to its host cellular environment, evade immune responses, and develop drug resistance by modulating the expression of genes in response to environmental signals [1, 6]. This ability is mainly contributed by a group of proteins called two-component systems (TCS), which are major signaling proteins in bacteria [7–8]. Because TCSs are absent from humans and other animals, they are attractive targets for developing new antibiotics [9–10]. A TCS typically consists of a sensor histidine kinase (HK) and a response regulator (RR). Most HKs are membrane bound and sense environmental signals. Sensing of the signals activates the HK kinase activity to phosphorylate its cognate RR, which in turn mediates cellular responses, mostly through regulating gene expression [11].

TCSs play an important role in bacterial pathogenesis, with the Salmonella enterica PhoPQ being a well-studied example [12–13]. Disrupting either phoP (encoding a RR) or phoQ (encoding a HK) in S. enterica makes it avirulent, suggesting that the PhoPQ proteins can be effective drug targets. Because TCSs work upstream of the targets of conventional antibiotics, drugs inhibiting TCSs are likely to be effective against drug-resistant bacterial pathogens [9]. Similar to the Salmonella PhoPQ system, the PhoPR two-component system in MTB is essential for virulence [14]. PhoR is a transmembrane sensor HK, and PhoP is a RR that regulates expression of over 110 genes [15–17]. Because disrupting the phoPR genes severely attenuates MTB growth in infection models, these attenuated strains are being developed as live vaccines [18–20], and one such vaccine candidate is currently in clinical trials [21]. Further demonstrating the importance of PhoPR in virulence, a mutation that upregulates expression of phoPR has been found in an MTB outbreak strain that is associated with increased dissemination and severity of human TB [22]. The function of PhoPR on MTB virulence is directly related to the ability of PhoP to regulate gene transcription. A single point mutation in phoP of an avirulent strain, H37Ra, is responsible for most of its avirulent phenotype [23–25]. This mutation, Ser219 to Leu, is located on the DNA-recognition helix [26–27], and the mutation reduces the PhoP-binding affinity to gene promoters. These findings suggest that PhoP inhibitors can potentially be new drugs to treat TB by disrupting the PhoPR function.

PhoP belongs to the OmpR/PhoB family of response regulators [28]. It has two distinct domains, an N-terminal receiver domain that contains the phosphorylation site Asp and a C-terminal effector domain that contains DNA-binding elements [26–27]. The DNA sequences that bind PhoP contain a direct repeat of a 7-bp motif with a 4-bp spacer [29]. PhoP is a monomer in solution, but it binds DNA highly cooperatively as a dimer. Based on the PhoP-DNA binding mechanism revealed by the crystal structure of a PhoP-DNA complex [30], we designed a FRET-based high-throughput screening (HTS) assay for identification of inhibitors of the PhoP-DNA binding. The FRET assay has been miniaturized into a 1536-well plate format for large-scale compound library screening.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Site-directed mutagenesis and protein purification

Mutagenesis of the phoP gene to replace Asp106 with Cys was performed using the QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The pET28-phoP plasmid [27] was used as the template, and the mutation primers were D106C_f and D106C_r (Table 1).

Table 1.

DNA oligo sequences used in this study. The top two sequences are PCR primers, the last two are of the counterscreen, and the rest are of DNA duplexes for PhoP-DNA complexes. The 7-bp motifs of the PhoP-binding sequences are highlighted in bold type.

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| D106C_f | CGTGACTCGCTACAGTGCAAGATCGCGGGTCTG |

| D106C_r | CAGACCCGCGATCTTGCACTGTAGCGAGTCACG |

| cy3-sel36_f | /5Cy3/GATTCACAGCTGATTCACAGCATCTAG |

| sel36_f | GATTCACAGCTGATTCACAGCATCTAG |

| sel36_r | CTAGATGCTGTGAATCAGCTGTGAATC |

| cy3-sel36m_f | /5Cy3/GATTCACAGCTGATaCACAGgATCTAG |

| sel36m_f | GATTCACAGCTGATaCACAGgATCTAG |

| sel36m_r | CTAGATcCTGTGtATCAGCTGTGAATC |

| cy3_ahpC_f | /5Cy3/GCCTgACAGCGACTTCACgGCACGATG |

| ahpC_f | GCCTgACAGCGACTTCACgGCACGATG |

| ahpC_r | CATCGTGCcGTGAAGTCGCTGTcAGGC |

| 14bp_f | /5Cy5/CCTAGCAGCAGTGG |

| 14bp_r | /5Cy3/CCACTGCTGCTAGG |

The pET28-phoP plasmids containing the wild type or mutated phoP genes were transformed into E. coli strain BL21 (DE3). Protein expression was induced by IPTG at 18 °C overnight. The proteins were purified using Ni2+-affinity chromatography as described previously [27]. In brief, the protein purified from Ni2+-affinity column was cleaved by the TEV protease to remove the His-tag, and the tag-free protein was again passed through the Ni2+-affinity column to separate from the His-tag, un-cleaved protein, and His-tagged TEV protease. The proteins were further purified and buffer-exchanged with a Superdex 200 column (GE Life Sciences) prior to downstream applications.

2.2. Purification and fluorophore labeling of PhoP-DNA complexes

Oligonucleotides of Cy3-labeled DNA (Table 1) were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, Coralville, IA). Two complementary strains were mixed and annealed by heating at 80 °C and then slowly cooling to room temperature. The Cy3-labeled DNA was mixed with purified PhoP at a 1:2 DNA-protein molar ratio in the binding buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, and 5 mM MgCl2). Cy5-maleimide (GE Life Sciences) was dissolved in anhydrous dimethylformamide according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cy5-maleimide in 10-fold excess was mixed with PhoP or PhoP-DNA in the binding buffer supplemented with 1 mM TCEP, and the mixture was incubated at 4 °C overnight. The labeling mixture was first passed through a PD MiniTrap column (GE Healthcare) in the binding buffer to remove the majority of free Cy5 dye; fractions containing the protein were then passed through a Superdex 200 column to further purify the complex. The concentration of the complex was determined by UV-Vis spectrophotometry monitoring absorbance at 260, 280, 550, and 650 nm, which are the absorbance maxima of DNA, protein, Cy3, and Cy5, respectively.

2.3. Isothermal titration calorimetry measurements

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments were conducted at 20 °C with a MicroCal iTC200 system in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, and 5 mM MgCl2 as described previously [29]. The DNA sample in the syringe was titrated into the protein sample in the cell. The sample cell was stirred at 800 rpm. The data were fitted using Origin 7.0 with a one-set-of-sites binding model.

2.4. Thermofluor

Thermofluor experiments were performed with an ABI Prism 7900HT system. Protein at a ~0.02 mg/ml concentration was mixed with 1000-fold diluted SYPRO Orange (Life Technologies) in various buffers in a 96-well PCR plate. The samples were heated from 25 to 95 °C at a ramp rate of 1%, and the fluorescence intensity was measured continuously. The data were fitted to a Boltzmann equation [31] using EXCEL Solver (Microsoft Office) to obtain the melting temperatures.

2.5. FRET assay

The Cy3-labeled DNA and Cy5-labeled PhoP formed a FRET pair for this assay. For assay development, samples were mixed in 96-well plates, and fluorescence was measured in an EnVision microplate reader (PerkinElmer) with an excitation wavelength of 485 (±20) nm and emissions of 535 (±40) and 665 (±20) nm.

2.6. Compound libraries and high-throughput screening

Three small compound collections were screened including the Ligand of Pharmacologically Active Compounds (LOPAC, Sigma-Aldrich), approved drug collection of 2800 compounds, and clinical drug candidates of 2000 compounds. Compounds were prepared and diluted in DMSO at a 1:3 ratio in 384-well polypropylene plates which were transferred to 1,536-well polypropylene plates using a 384-well pipettor station (Cybi-well, Cybio Inc).

The purified PhoP-Cy5-DNA-Cy3 complex in the assay buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 0.01% tween-20) was dispensed to 1536-well assay plates at 2.5 µl/well using a Multidrop-Combi (Thermo Scientifics) dispensing station followed by addition of 23 nl/well of compound solutions using a Pintool station (Waco Automation, San Diego, CA). After incubation at room temperature for 2 hours, the assay plates were measured with excitation of 485 (±20) nm and emissions of 565 (±20) and 665 (±20) nm. NaCl at 1 M was used as a positive control (100% inhibition), and DMSO in place of the compounds as a negative control (0% inhibition).

A 14-bp DNA duplex labeled with Cy3 in one end and Cy5 in the other end (14bp_f and 14bp_r in Table 1) was used as a counterscreen to eliminate false-positive compounds. The DNA duplex obtained from IDT was dissolved at 5 µM in the binding buffer, and then diluted into the assay buffer. The fluorescence was detected with the excitation and emission wavelengths same as those for the labeled PhoP-DNA complex.

2.7. Protein thermal stability assay

PhoP thermal stability was assayed by heating the protein samples at different temperatures and then measuring the amount of the protein remaining in solution. PhoP at 20 µg/ml was mixed with the inhibitors in a total volume of 50 µl and heated for 3 min in a thermocycler. After heating, the samples were immediately transferred to an ice-water bath. The denatured protein was precipitated by centrifugation at 4 °C and 15,000 g for 5 min. The supernatant was mixed with the Protein Assay solution (Bio-Rad) at a 4:1 ratio, and the absorbance at 595 nm was measured in a SmartSpec Plus spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad). The data were fitted to the Boltzmann equation [31] using EXCEL Solver to obtain the melting temperatures.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Assay principle

Because PhoP-DNA binding is essential for the PhoP function as a transcriptional regulator in regulating MTB virulence, disrupting the PhoP-DNA interaction should attenuate the MTB virulence. To screen for inhibitors that disrupt the PhoP-DNA binding, we designed a FRET-based assay, guided by the crystal structure of the PhoP-DNA complex [29] (Figure 1). The FRET system consisted of the Cy3-labeled DNA as the donor and the Cy5-labeled PhoP protein as the acceptor. A FRET signal from Cy3 to Cy5 is present when PhoP-Cy5 binds to DNA-Cy3, whereas dissociation of the PhoP-DNA complex by PhoP inhibitors reduces the FRET signal.

Fig 1.

Design of a FRET system guided by the structure of the PhoP-DNA complex. The two PhoP molecules are designated as A and B. Molecule A is colored in dark green and light green for its receiver and effector domain, respectively, and molecule B is colored in blue and cyan. The recognition helix and wing in molecule B are labeled. The side chain of D106 in molecule A is shown as sticks; the residue is disordered in B. The sites of Cy3 and Cy5 labels are marked with red and blue stars, respectively. Their approximate distances are labeled.

3.2. Purification of the single-cysteine PhoP mutant

The wild-type PhoP protein is free of Cys. To attach Cy5-maleimide to PhoP, we prepared a single-cysteine mutant of PhoP by replacing Asp106 with Cys (D106C). Asp106 is located at the N-terminus of α4 in molecule A, but is in a disordered loop in molecule B, whose α4 is unwound and involved in the dimer interface (Figure 1). The distance from the Asp106 side chain to the end of the DNA where Cy3 is attached is ~25 Å, well within the Forster distance of 54 Å [32]. The mutant protein was purified by Ni2+-affinity and gel filtration chromatography similarly to the wild-type protein. The thermal stability profile was similar to that of the wild type (Figure 2) and its DNA-binding affinity was also identical to that of the wild type (Table 2). These observations suggested that mutation of Asp106 to Cys did not affect the PhoP function.

Fig 2.

Comparison of thermal stability profiles of the wild-type PhoP and D106C mutant. The melting temperatures were measured by Thermofluor as described in Methods. All conditions had 100 mM HEPES at pH 7.5 with additional components as labeled. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the measurements. Melting temperatures of both wild type and mutant varied with the additives in the buffer in a similar manner. The two profiles are essentially identical within the error of measurements.

Table 2.

Comparison of PhoP-DNA binding thermodynamic parameters for the wild type (wt) and D106C mutant of PhoP. Dissociation constants (Kd, nM), enthalpy (ΔH, kcal/mol), and stoichiometry (N) were obtained by fitting the ITC titration data with Origin using a one-set-of-sites model. Values of TΔS (kcal/mol) were calculated from the values of Kd and ΔH. N is the number of DNA molecule per PhoP molecule. The data are the average and standard deviation of two or three titrations. DNA sequences are listed in Table 1.

| DNA | PhoP | Kd | ΔH | TΔS | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sel36 | wt | 8.03±3.42 | −12.11±0.10 | −1.22±0.16 | 0.45±0.02 |

| D106C | 7.48±2.16 | −12.03±0.31 | −1.11±0.14 | 0.37±0.02 | |

|

| |||||

| sel36m | wt | 32.27±4.12 | −9.41±0.36 | 0.64±0.41 | 0.50±0.09 |

| D106C | 38.20±4.31 | −9.74±1.22 | 0.51±0.60 | 0.52±0.11 | |

3.3. Preparation of the PhoP-Cy5-DNA-Cy3 complex

Purified D106C was either directly labeled with Cy5-maleimide or complexed with DNA first and then reacted with the fluorescent dye. Because the PhoP-DNA complex is much more stable than PhoP alone, the preformed complex had a better labeling efficiency. Therefore, the large-scale Cy5 labeling reaction was performed with the PhoP-DNA complexes, prepared by mixing purified D106C protein with annealed Cy3-labeled DNA duplex in a molar ratio of 2 to 1 (protein to DNA). The fluorophore-labeled PhoP-DNA complex was purified by gel filtration. The absorbance profiles at 260, 280, 550, and 650 nm of the elution fractions were perfectly superposed on each other (Figure 3), indicating that the peak contained both protein-Cy5 and DNA-Cy3 in a complex. The peak fractions had a purple color that came from the mixture of blue (Cy5) and red (Cy3) dyes. The purified complex had a molar ratio of Cy5-to-Cy3 of ~1.35, indicating a Cy5-maleimide labeling efficiency of ~67%.

Fig 3.

Elution profile of the Cy3-Cy5-labeled PhoP-DNA complex from Superdex 200 column. The PhoP-DNA-Cy3 complex was labeled with excess Cy5-maleimide, and the labeling mixture of was first passed through a PD MiniTrap column to remove the majority of free dye before loading on the Superdex 200 column (see Methods for details). Fractions of 0.5 ml were collected and their absorbance at 260, 280, 550, and 650 nm were measured. The absorbance at 550 nm (A550, gray line) was plotted using the secondary vertical axis to bring the curve to a scale comparable to that of A260 (solid black line). The peaks of A550 (Cy3) and A260 (DNA) curves coincide with each other, indicating the accuracy of the data. The slightly elevated reading of A280 (dotted line) relative to that of A650 (dashed line) at the tail of the major peak was due to a shoulder peak from impurities in the DNA sample.

3.4. Assay development

The assay development was performed in a 96-well plate format. To assess the energy transfer efficiency between Cy3 and Cy5 in the protein-DNA complex, we monitored the fluorescence intensities at the emission wavelengths of both fluorophores with the donor Cy3 being excited. The DNA used in this experiment was sel36 (Table 1). Significant fluorescence energy transfer occurred when both the Cy5-labeled PhoP and Cy3-labeled DNA were in a complex (Figure 4a). Therefore, dissociation of the PhoP-DNA complex can be detected by measuring the disruption of the fluorescence of energy transfer from Cy3 to Cy5.

Fig 4.

Development of the Cy3-Cy5 FRET-based HTS assay. Fluorescence intensity was measured with an EnVision microplate reader. The excitation filter was at 485 nm to excite Cy3 except for panel (c) as noted below. Emission was monitored in two channels: the Cy3 channel at 535 nm and the Cy5 channel at 665 nm. Samples were placed in a 96-well microplate at a volume of 100 µl. Error bars are the standard deviations. (a) Fluorescence intensities of both emission channels of various samples as labeled. The fluorescence of free Cy3-labeld DNA in the absence or presence of free Cy5 saturated the Cy3 emission channel. A mixture of both Cy5-labeled PhoP and Cy3-labled DNA reduced the Cy3 fluorescence and increased the Cy5 fluorescence. (b) Relative fluorescence of the PhoP-DNA complexes in the presence of NaCl and SDS. Purified PhoP-DNA complexes were mixed with NaCl or SDS, and the Cy5 emission was measured. (c) Effects of NaCl and SDS on the fluorescence of free Cy5, measured with the excitation filter at 555 nm and emission filter at 665 nm. Free Cy5 dye was at ~2 µM. NaCl had negligible reduction of the Cy5 fluorescence, but 1% SDS increased the fluorescence by ~75%. (d) Relative fluorescence (Cy5 channel) of the purified PhoP-ahpC complex at 10-, 15-, and 20-fold dilution. The fluorescence intensity of Cy5 was proportional to the PhoP-ahpC concentration. 1 M NaCl lowered the FRET signal by ~10-fold for all three dilutions. (e) Effects of various assay components on the Cy5 emission of the PhoP-ahpC complex. The concentration of the PhoP-DNA complex was ~0.4 µM, DMSO was at 10%, tween 20 was at 0.01%, and NaCl was at 1M.

Because no PhoP inhibitor is available as a positive control, we used high salt concentration or SDS to dissociate the PhoP-DNA complex. The effect of salt on the FRET signal depended on the concentration of the complex and the sequence of the DNA, which correlates with the affinity of the complex [29]. For a perfect direct-repeat sequence sel36, the PhoP-DNA complex was so stable that 1 M NaCl only reduced the FRET signal to ~60% when the complex was at high concentration (Figure 4b). At lower PhoP-DNA concentrations, 1 M NaCl efficiently dissociated the complex with a ~10-fold reduction of FRET signal for medium-affinity complexes [29], such as the PhoP-ahpC (Figure 4b). This level of reduction in FRET signal was similar to that between the PhoP-Cy5-DNA-Cy3 complex and the DNA-Cy3 mixed with free Cy5 in solution (comparing fluorescence at 665 nm of PhoP-Cy5+DNA-Cy3 with that of DNA-Cy3+free Cy5 in Figure 4a), suggesting a complete dissociation of the complex by 1 M NaCl. Because the quenching of Cy5 fluorescence by 1 M NaCl is negligible (Figure 4c), the reduction in FRET signal must be due to the dissociation of the PhoP-DNA complex. 1% SDS should dissociate the protein-DNA complex by denaturing the protein. However, for the PhoP-ahpC complex, the Cy5 emission in the presence of 1% SDS was slightly higher than that in the presence of 1 M NaCl (Figure 4b), presumably due to the increase of the quantum yield of the fluorophore by SDS (Figure 4c). These results indicate that NaCl at 1 M is a suitable positive control for the FRET-based binding assay of PhoP to DNA.

3.5. Selection of DNA sequence

To construct a FRET system for PhoP-DNA binding that is sensitive to PhoP inhibitors under physiological conditions, we selected the DNA sequence from the ahpC promoter (Table 1), which binds PhoP with a Kd value of 104 nM [30], an affinity on par with the majority of PhoP-binding sites on gene promoters [29]. As mentioned above, the DNA sequence determines the affinity of the PhoP-DNA complex and hence the likelihood of dissociation of the complex by PhoP inhibitors. The dimer interface is an attractive site for developing inhibitors to the PhoP-DNA binding because the binding is highly cooperative and dependent on the dimer-interface interactions [29]. The protein-DNA interface is extensive and buries ~1740 Å2 of the protein surface area, whereas the protein dimer interface is relatively weaker, burying ~790 Å2 of surface area per subunit [30]. Therefore, it is more likely for a small-molecule inhibitor to disrupt the dimer interface than to compete for the DNA-binding interface. The PhoP-ahpC complex is sensitive to the disruption in the PhoP dimer interface as single point mutations at the dimer interface increased the binding Kd by ~6-fold [30].

3.6. Assay optimization

The PhoP-ahpC complex with both Cy3 and Cy5 labels was prepared and purified for the FRET assay. To determine an optimal concentration, the purified complex at a concentration of ~7.9 µM was diluted 10-, 15-, and 20-fold in the assay buffer. The fluorescence intensity of Cy5 emission was proportional to the concentration of the PhoP-DNA complex (Figure 4d). At each dilution, the addition of 1 M NaCl to the assay solution reduced the FRET fluorescence by ~10-fold. The presence of 10% DMSO reduced the fluorescence of the PhoP-DNA complex by <10%, while tween-20 in the assay buffer improved the signal (Figure 4e). The buffer components had a background fluorescence of ~1% of the signal. Overall, a 20-fold dilution of the purified PhoP-DNA complex gave a suitable signal to noise ratio, and the buffer components did not interfere with the FRET assay.

3.7. High-throughput screen, hits identification and counterscreen

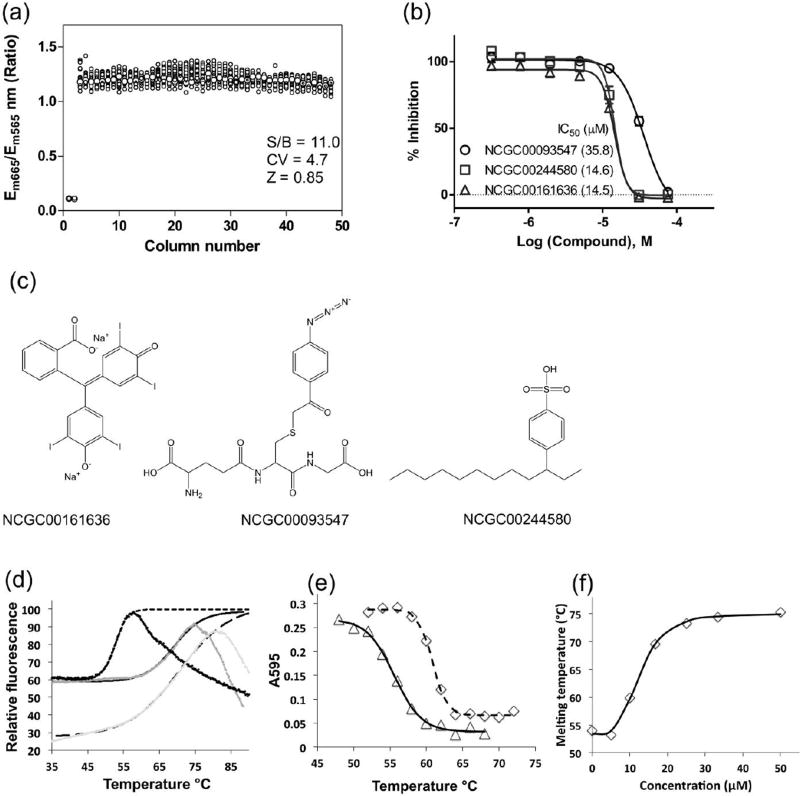

To increase compound screening throughput, we miniaturized this assay to the 1,536-well plate format. The purified PhoP-ahpC complex was incubated with the compound solutions followed by detection of the FRET signal. The signal-to-basal ratio was 11.0 fold, coefficient of variation (CV) was 4.7% and Z’ factor was 0.85 in this assay (Fig. 5a), indicating a robust assay suitable for HTS.

Fig 5.

HTS assay and confirmation of hits. (a) Scatter plot of 1536-well plate results determined in a DMSO plate test. The wells in columns 1 and 2 were added with 1 M NaCl as a positive control. Columns 3 to 48 were added with DMSO, a solvent for dissolving compounds. (b) Concentration response curves of three compounds from the confirmation screen, which were confirmed to inhibit PhoP-DNA interactions by direct binding to PhoP. (c) Structures of the three compounds. (d) Thermal melting curves of PhoP in the absence (black data points with short-dashed fitted curve) and presence of either compound NCGC00093547 (gray data points with solid curve) or NCGC00161636 (light gray data points with long-dashed curve) at 1 mM measured by Thermofluor. Relative fluorescence was expressed as the percentage of the fitted maximum fluorescence for each melting curve. The smooth curves are the data fitted to the Boltzmann equation. (e) Thermal shift curves measured by Bio-Rad protein microassay in the presence of 5 µM (triangle markers with solid curve) and 58 µM (diamond markers with dashed curve) NCGC00244580. PhoP was mixed with the inhibitor and heated, and the amount of the protein remained in solution was measured as described in Methods. (f) Inhibitor concentration dependence of PhoP melting temperature. At each concentration of the inhibitor NCGC00093547, a thermal melting curve was measured as in (e) to obtain the melting temperature.

We then screened ~6,000 compounds containing bioactive compounds and approved drugs [33]. A total of 118 primary hits were selected for confirmation. The compound confirmation was performed in the same FRET assay with 11 concentrations of the compounds, ranging from 8 nM to 77 µM.

The hits were also counter-screened in a FRET assay using a 14-bp DNA labeled with Cy3 attached to one end and Cy5 to the other end (Table 1). This counterscreen helped to eliminate false positives that directly interfered with the assay, such as compounds that quench the Cy3 or Cy5 fluorescence or absorb the excitation light. A 14-bp DNA duplex has a distance of ~47 Å between the two ends based on standard B form DNA conformation. Such a Cy3 and Cy5-labeled DNA duplex has an energy transfer efficiency of ~0.5 [34]. Compounds that reduced the FRET signal of this counterscreen were removed from the hit list.

Out of the selected 118 hits from the primary screen, 23 compounds were removed as their activities were too weak or not confirmed, and another 44 compounds were eliminated as false positives by the counterscreen. Among the confirmed compounds, 29 compounds exhibited complete inhibition of PhoP-DNA binding, and the other 20 compounds exhibited partial inhibition. The IC50 values of the confirmed compounds ranged from 1 to 100 µM. Two compounds increased the FRET signal of this assay, indicating a possible change in the conformation of the PhoP-DNA complex. From the positive hits, we selected 24 compounds for further experiments to confirm their direct binding to PhoP.

3.8. Confirmation of direct binding of inhibitors to PhoP

To eliminate compounds from HTS that reduced the FRET signal by competing with PhoP for binding to DNA, we assayed the direct binding of the compounds to PhoP. First, we applied the Thermofluor method [31]. Thermofluor uses a SYPRO orange dye that gives strong fluorescence when binding to exposed hydrophobic surface of heat-denatured proteins. Binding of inhibitors often stabilizes the protein and thereby shifts the protein melting temperature. We identified two compounds, NCGC00093547 and NCGC00161636, which increased the PhoP melting temperature by 14 and 18 °C, respectively, at the assay conditions (Figure 5d). The IC50 values for NCGC00093547 and NCGC00161636 were 15.6 and 15.5 µM, respectively, measured by the HTS confirmation screen (Figure 5b).

Many HTS hits interfered with the fluorescence measurement of Sypro Orange and therefore could not be confirmed by Thermofluor. For these compounds, we determined their effect on PhoP stability by measuring the amount of protein remaining in solution after heat treatments [35] using the Bio-Rad protein microassay. We identified another compound NCGC00244580 (IC50 = 35.8 µM by HTS confirmation screen) using this method (Figure 5e). As a proof of principle, we also measured the inhibitor concentration dependence of the melting-temperature shift for the compound NCGC00093547 (Figure 5f). At low inhibitor concentrations, there was no effect on the protein melting temperature. The melting temperature started to rise when the compound concentration was above 5 µM. The apparent dissociation constant was 12.6 µM, similar to the IC50 value measured by the HTS confirmation screen. Overall, the results confirmed that the FRET-based PhoP-DNA binding assay was effective for identifying PhoP inhibitors that directly bind to PhoP to inhibit its DNA binding.

4. DISCUSSION

Drug-resistant TB is a formidable challenge to modern medicine. Current treatment regimens can take up to 2 years with a combination of multiple drugs that can have severe side effects. Globally, the treatment success rate of MDR-TB patients is only 50%, and the success rate drops to 26% for XDR-TB [36]. New and better treatments are urgently needed to combat this formidable human pathogen.

All current TB drugs attack essential cellular activities. The first line TB drugs are isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, ethambutol and streptomycin. Isoniazid is a prodrug that is activated by the catalase peroxidase (KatG) in MTB [37]. The activated molecule binds to InhA, an enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase, thereby inhibiting the synthesis of mycolic acids, which are components of the mycobacterial cell wall [38]. Activation of isoniazid by KatG also produced a range of radicals, including nitric oxide, and these free radicals also contribute to the killing of the bacteria [39]. Rifampicin inhibits bacterial RNA polymerase [40]. It binds in a pocket of the β subunit of RNA polymerase deep within the DNA/RNA channel and thereby blocks the path of the elongating RNA. Pyrazinamide is a prodrug that is converted by the bacterial pyrazinamidase to the active form pyrazinoic acid, which inhibits fatty acid synthase type I [41]. Pyrazinamide also targets the ribosomal protein S1 and inhibits its trans-translation activity [42]. Ethambutol works by inhibiting arabinosyl transferase for the synthesis of arabinogalactan, a cell wall component [43–44]. Streptomycin inhibits protein synthesis by binding to the 16S rRNA of the 30S subunit of the bacterial ribosome [45–46].

The second line TB drug Ethionamide is a prodrug that is activated by EthA, a mono-oxygenase in MTB, and the activated molecule inhibits InhA in the same way as isoniazid [47]. The quinolone drugs, such as moxifloxacin, target DNA gyrase [48]. The three new TB drugs, bedaquiline, delamanid, and pretomanid, also target essential cellular functions. Bedaquiline is the first new TB drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in more than 40 years [49]. It targets the proton pump of ATP synthase in MTB [50], leading to inadequate ATP synthesis. Delamanid and pretomanid are nitroimidazoles, which works by blocking the synthesis of mycolic acids, but in a manner different from isoniazid [51].

MTB acquires drug resistance through spontaneous mutations of its genomic sequence [52]. Disruption of essential cellular activities by TB drugs leads to selection and enrichment of mutations of drug resistance during the prolonged treatment that is necessary to cure TB. TCSs offer ideal drug targets that can potentially overcome such a problem [53]. TCS Inhibitors target the upstream functions that control proteins of essential cellular activities. Therefore, they are likely to be effective against existing drug-resistant TB. In addition, because TCSs control multiple proteins of essential cellular activities, bacterial resistance is less likely to develop. Furthermore, the PhoPR TCS is essential for MTB virulence but not for its survival. Drugs inhibiting PhoPR will attenuate MTB virulence without killing the bacterium, and hence there is less selection pressure for drug-resistant mutations [54]. The development of the phoP-knockout strain as a live-attenuated MTB vaccine supports the feasibility of developing PhoP inhibitors as TB drugs [21].

Recently, the DNA consensus motif for binding PhoP has been identified [29, 55–56], and the structure of a PhoP-DNA complex has been reported that reveals detailed PhoP-DNA binding interactions [30]. These findings make it possible to design a FRET-based HTS assay to screen for PhoP inhibitors that disrupt the PhoP binding to gene promoters. Such PhoP inhibitors should disrupt the cellular response to the signals sensed by the PhoPR system and thereby attenuate the MTB virulence, mimicking the effect of the phoP mutant [15–16]. We have confirmed three PhoP inhibitors with IC50 values of 14.5 to 35.8 µM that blocked the PhoP-DNA interaction. Although these compounds were not potent, the results indicated that our assay is useful for further screening of a large compound collection to identify better lead compounds for drug development.

In summary, PhoP is an attractive target for developing novel anti-TB drugs to overcome the drug-resistant problems. We developed a FRET-based assay suitable for high-throughput screening of compound libraries for inhibitors of PhoP-DNA interactions. A screen of ~6,000 compounds using this assay led to identification of three compounds, which were confirmed to directly bind PhoP to disrupt its DNA-binding activity. These PhoP inhibitors can be lead compounds for further development of potent PhoP inhibitors as a novel class of anti-TB drugs that should be effective against drug-resistant TB.

Acknowledgments

All authors contributed to the design, performance, analysis, or reporting of the work. The authors thank Drs. Rongde Qiu, Huaiyan Cheng, and Yinghong Feng for their assistance in operating the EnVision microplate reader, and thank the compound management team at NCATS for their assistance with the chemical compound libraries.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant R01GM079185 and the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences intramural grants R071IR and R0713018 to S.W., and by the Intramural Research Program of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health to W.Z. The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private ones of the authors and are not to be construed as official or reflecting the views of the Department of Defense, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, or National Institute of Health.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Dalton T, Cegielski P, Akksilp S, Asencios L, Campos Caoili J, Cho SN, Erokhin VV, Ershova J, Gler MT, Kazennyy BY, Kim HJ, Kliiman K, Kurbatova E, Kvasnovsky C, Leimane V, van der Walt M, Via LE, Volchenkov GV, Yagui MA, Kang H, Akksilp R, Sitti W, Wattanaamornkiet W, Andreevskaya SN, Chernousova LN, Demikhova OV, Larionova EE, Smirnova TG, Vasilieva IA, Vorobyeva AV, Barry CE, 3rd, Cai Y, Shamputa IC, Bayona J, Contreras C, Bonilla C, Jave O, Brand J, Lancaster J, Odendaal R, Chen MP, Diem L, Metchock B, Tan K, Taylor A, Wolfgang M, Cho E, Eum SY, Kwak HK, Lee J, Min S, Degtyareva I, Nemtsova ES, Khorosheva T, Kyryanova EV, Egos G, Perez MT, Tupasi T, Hwang SH, Kim CK, Kim SY, Lee HJ, Kuksa L, Norvaisha I, Skenders G, Sture I, Kummik T, Kuznetsova T, Somova T, Levina K, Pariona G, Yale G, Suarez C, Valencia E, Viiklepp P. Prevalence of and risk factors for resistance to second-line drugs in people with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in eight countries: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2012;380(9851):1406–17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60734-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zumla A, George A, Sharma V, Herbert RH, Baroness Masham of I. Oxley A, Oliver M. The WHO 2014 global tuberculosis report--further to go. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(1):e10–2. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70361-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aagaard C, Dietrich J, Doherty M, Andersen P. TB vaccines: current status and future perspectives. Immunol Cell Biol. 2009;87(4):279–86. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen P, Doherty TM. The success and failure of BCG - implications for a novel tuberculosis vaccine. Nature reviews. 2005;3(8):656–62. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colditz GA, Brewer TF, Berkey CS, Wilson ME, Burdick E, Fineberg HV, Mosteller F. Efficacy of BCG vaccine in the prevention of tuberculosis. Meta-analysis of the published literature. Jama. 1994;271(9):698–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. Drug-resistant tuberculosis: World Health Organization launches global response plan 2007–2008. Euro Surveill. 2007;12(7):E0707053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.West AH, Stock AM. Histidine kinases and response regulator proteins in two-component signaling systems. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26(6):369–76. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01852-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stock AM, Robinson VL, Goudreau PN. Two-component signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:183–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gotoh Y, Eguchi Y, Watanabe T, Okamoto S, Doi A, Utsumi R. Two-component signal transduction as potential drug targets in pathogenic bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2010;13(2):232–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang YT, Gao R, Havranek JJ, Groisman EA, Stock AM, Marshall GR. Inhibition of bacterial virulence: drug-like molecules targeting the Salmonella enterica PhoP response regulator. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2012;79(6):1007–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2012.01362.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang S. Bacterial Two-Component Systems: Structures and Signaling Mechanisms. In: Huang C, editor. Protein Phosphorylation in Human Health. InTech: Rijeka: Croatia; 2012. pp. 439–466. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zwir I, Latifi T, Perez JC, Huang H, Groisman EA. The promoter architectural landscape of the Salmonella PhoP regulon. Mol Microbiol. 2012;84(3):463–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08036.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller SI, Kukral AM, Mekalanos JJ. A two-component regulatory system (phoP phoQ) controls Salmonella typhimurium virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(13):5054–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.13.5054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryndak M, Wang S, Smith I. PhoP, a key player in Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16(11):528–34. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perez E, Samper S, Bordas Y, Guilhot C, Gicquel B, Martin C. An essential role for phoP in Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2001;41(1):179–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walters SB, Dubnau E, Kolesnikova I, Laval F, Daffe M, Smith I. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis PhoPR two-component system regulates genes essential for virulence and complex lipid biosynthesis. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60(2):312–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalo-Asensio J, Mostowy S, Harders-Westerveen J, Huygen K, Hernandez-Pando R, Thole J, Behr M, Gicquel B, Martin C. PhoP: a missing piece in the intricate puzzle of Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence. PLoS One. 2008;3(10):e3496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin C, Williams A, Hernandez-Pando R, Cardona PJ, Gormley E, Bordat Y, Soto CY, Clark SO, Hatch GJ, Aguilar D, Ausina V, Gicquel B. The live Mycobacterium tuberculosis phoP mutant strain is more attenuated than BCG and confers protective immunity against tuberculosis in mice and guinea pigs. Vaccine. 2006;24(17):3408–19. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aporta A, Arbues A, Aguilo JI, Monzon M, Badiola JJ, de Martino A, Ferrer N, Marinova D, Anel A, Martin C, Pardo J. Attenuated Mycobacterium tuberculosis SO2 vaccine candidate is unable to induce cell death. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45213. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nambiar JK, Pinto R, Aguilo JI, Takatsu K, Martin C, Britton WJ, Triccas JA. Protective immunity afforded by attenuated, PhoP-deficient Mycobacterium tuberculosis is associated with sustained generation of CD4+ T-cell memory. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42(2):385–92. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arbues A, Aguilo JI, Gonzalo-Asensio J, Marinova D, Uranga S, Puentes E, Fernandez C, Parra A, Cardona PJ, Vilaplana C, Ausina V, Williams A, Clark S, Malaga W, Guilhot C, Gicquel B, Martin C. Construction, characterization and preclinical evaluation of MTBVAC, the first live-attenuated M. tuberculosis-based vaccine to enter clinical trials. Vaccine. 2013;31(42):4867–73. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soto CY, Menendez MC, Perez E, Samper S, Gomez AB, Garcia MJ, Martin C. IS6110 mediates increased transcription of the phoP virulence gene in a multidrug-resistant clinical isolate responsible for tuberculosis outbreaks. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(1):212–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.1.212-219.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng H, Lu L, Wang B, Pu S, Zhang X, Zhu G, Shi W, Zhang L, Wang H, Wang S, Zhao G, Zhang Y. Genetic basis of virulence attenuation revealed by comparative genomic analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain H37Ra versus H37Rv. PLoS One. 2008;3(6):e2375. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JS, Krause R, Schreiber J, Mollenkopf HJ, Kowall J, Stein R, Jeon BY, Kwak JY, Song MK, Patron JP, Jorg S, Roh K, Cho SN, Kaufmann SH. Mutation in the transcriptional regulator PhoP contributes to avirulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra strain. Cell host & microbe. 2008;3(2):97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frigui W, Bottai D, Majlessi L, Monot M, Josselin E, Brodin P, Garnier T, Gicquel B, Martin C, Leclerc C, Cole ST, Brosch R. Control of M. tuberculosis ESAT-6 secretion and specific T cell recognition by PhoP. PLoS pathogens. 2008;4(2):e33. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang S, Engohang-Ndong J, Smith I. Structure of the DNA-binding domain of the response regulator PhoP from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochemistry. 2007;46(51):14751–61. doi: 10.1021/bi700970a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Menon S, Wang S. Structure of the response regulator PhoP from Mycobacterium tuberculosis reveals a dimer through the receiver domain. Biochemistry. 2011;50(26):5948–57. doi: 10.1021/bi2005575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galperin MY. Structural classification of bacterial response regulators: diversity of output domains and domain combinations. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(12):4169–82. doi: 10.1128/JB.01887-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He X, Wang S. DNA consensus sequence motif for binding response regulator PhoP, a virulence regulator of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochemistry. 2014;53(51):8008–20. doi: 10.1021/bi501019u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He X, Wang L, Wang S. Structural basis of DNA sequence recognition by the response regulator PhoP in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24442. doi: 10.1038/srep24442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ericsson UB, Hallberg BM, Detitta GT, Dekker N, Nordlund P. Thermofluor-based high-throughput stability optimization of proteins for structural studies. Anal Biochem. 2006;357(2):289–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuan F, Griffin L, Phelps L, Buschmann V, Weston K, Greenbaum NL. Use of a novel Forster resonance energy transfer method to identify locations of site-bound metal ions in the U2-U6 snRNA complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(9):2833–45. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang R, Southall N, Wang Y, Yasgar A, Shinn P, Jadhav A, Nguyen DT, Austin CP. The NCGC pharmaceutical collection: a comprehensive resource of clinically approved drugs enabling repurposing and chemical genomics. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(80):80ps16. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iqbal A, Arslan S, Okumus B, Wilson TJ, Giraud G, Norman DG, Ha T, Lilley DM. Orientation dependence in fluorescent energy transfer between Cy3 and Cy5 terminally attached to double-stranded nucleic acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(32):11176–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801707105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jafari R, Almqvist H, Axelsson H, Ignatushchenko M, Lundback T, Nordlund P, Martinez Molina D. The cellular thermal shift assay for evaluating drug target interactions in cells. Nat Protoc. 2014;9(9):2100–22. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2015. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suarez J, Ranguelova K, Jarzecki AA, Manzerova J, Krymov V, Zhao X, Yu S, Metlitsky L, Gerfen GJ, Magliozzo RS. An oxyferrous heme/protein-based radical intermediate is catalytically competent in the catalase reaction of Mycobacterium tuberculosis catalase-peroxidase (KatG) J Biol Chem. 2009;284(11):7017–29. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808106200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rozwarski DA, Grant GA, Barton DH, Jacobs WR, Jr, Sacchettini JC. Modification of the NADH of the isoniazid target (InhA) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 1998;279(5347):98–102. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5347.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wengenack NL, Rusnak F. Evidence for isoniazid-dependent free radical generation catalyzed by Mycobacterium tuberculosis KatG and the isoniazid-resistant mutant KatG(S315T) Biochemistry. 2001;40(30):8990–6. doi: 10.1021/bi002614m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campbell EA, Korzheva N, Mustaev A, Murakami K, Nair S, Goldfarb A, Darst SA. Structural mechanism for rifampicin inhibition of bacterial rna polymerase. Cell. 2001;104(6):901–12. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00286-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zimhony O, Vilcheze C, Arai M, Welch JT, Jacobs WR., Jr Pyrazinoic acid and its n-propyl ester inhibit fatty acid synthase type I in replicating tubercle bacilli. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2007;51(2):752–4. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01369-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi W, Zhang X, Jiang X, Yuan H, Lee JS, Barry CE, 3rd, Wang H, Zhang W, Zhang Y. Pyrazinamide inhibits trans-translation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 2011;333(6049):1630–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1208813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Telenti A, Philipp WJ, Sreevatsan S, Bernasconi C, Stockbauer KE, Wieles B, Musser JM, Jacobs WR., Jr The emb operon, a gene cluster of Mycobacterium tuberculosis involved in resistance to ethambutol. Nat Med. 1997;3(5):567–70. doi: 10.1038/nm0597-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Belanger AE, Besra GS, Ford ME, Mikusova K, Belisle JT, Brennan PJ, Inamine JM. The embAB genes of Mycobacterium avium encode an arabinosyl transferase involved in cell wall arabinan biosynthesis that is the target for the antimycobacterial drug ethambutol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(21):11919–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Springer B, Kidan YG, Prammananan T, Ellrott K, Bottger EC, Sander P. Mechanisms of streptomycin resistance: selection of mutations in the 16S rRNA gene conferring resistance. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2001;45(10):2877–84. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.10.2877-2884.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wong SY, Lee JS, Kwak HK, Via LE, Boshoff HI, Barry CE., 3rd Mutations in gidB confer low-level streptomycin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2011;55(6):2515–22. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01814-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnsson K, King DS, Schultz PG. Studies on the mechanism of action of isoniazid and ethionamide in the chemotherapy of tuberculosis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117(17):5009–5010. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Drlica K, Hiasa H, Kerns R, Malik M, Mustaev A, Zhao X. Quinolones: action and resistance updated. Curr Top Med Chem. 2009;9(11):981–98. doi: 10.2174/156802609789630947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cox E, Laessig K. FDA approval of bedaquiline--the benefit-risk balance for drug-resistant tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(8):689–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1314385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andries K, Verhasselt P, Guillemont J, Gohlmann HW, Neefs JM, Winkler H, Van Gestel J, Timmerman P, Zhu M, Lee E, Williams P, de Chaffoy D, Huitric E, Hoffner S, Cambau E, Truffot-Pernot C, Lounis N, Jarlier V. A diarylquinoline drug active on the ATP synthase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 2005;307(5707):223–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1106753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matsumoto M, Hashizume H, Tomishige T, Kawasaki M, Tsubouchi H, Sasaki H, Shimokawa Y, Komatsu M. OPC-67683, a nitro-dihydro-imidazooxazole derivative with promising action against tuberculosis in vitro and in mice. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Almeida Da Silva PE, Palomino JC. Molecular basis and mechanisms of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: classical and new drugs. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(7):1417–30. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rasko DA, Moreira CG, Li de R, Reading NC, Ritchie JM, Waldor MK, Williams N, Taussig R, Wei S, Roth M, Hughes DT, Huntley JF, Fina MW, Falck JR, Sperandio V. Targeting QseC signaling and virulence for antibiotic development. Science. 2008;321(5892):1078–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1160354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dong YH, Wang LH, Xu JL, Zhang HB, Zhang XF, Zhang LH. Quenching quorum-sensing-dependent bacterial infection by an N-acyl homoserine lactonase. Nature. 2001;411(6839):813–7. doi: 10.1038/35081101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Galagan JE, Minch K, Peterson M, Lyubetskaya A, Azizi E, Sweet L, Gomes A, Rustad T, Dolganov G, Glotova I, Abeel T, Mahwinney C, Kennedy AD, Allard R, Brabant W, Krueger A, Jaini S, Honda B, Yu WH, Hickey MJ, Zucker J, Garay C, Weiner B, Sisk P, Stolte C, Winkler JK, Van de Peer Y, Iazzetti P, Camacho D, Dreyfuss J, Liu Y, Dorhoi A, Mollenkopf HJ, Drogaris P, Lamontagne J, Zhou Y, Piquenot J, Park ST, Raman S, Kaufmann SH, Mohney RP, Chelsky D, Moody DB, Sherman DR, Schoolnik GK. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis regulatory network and hypoxia. Nature. 2013;499(7457):178–83. doi: 10.1038/nature12337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Solans L, Gonzalo-Asensio J, Sala C, Benjak A, Uplekar S, Rougemont J, Guilhot C, Malaga W, Martin C, Cole ST. The PhoP-dependent ncRNA Mcr7 modulates the TAT secretion system in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS pathogens. 2014;10(5):e1004183. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]