Abstract

Background

Pavlovian-Instrumental-Transfer (PIT) examines the effects of associative learning upon instrumental responding. Previous studies examining PIT with ethanol-maintained responding showed increases in responding following presentation of an ethanol-paired Conditioned Stimulus (CS). Recently, we conducted two studies examining PIT with an ethanol-paired CS. One of these found increases in responding, while the other did not. This less robust demonstration of PIT may have resulted from the form of the CS used, as we used a 120-s light stimulus as a CS, while the previous studies used either a 120-s auditory stimulus or a 10-s light stimulus. The present study examined whether using conditions similar to our earlier study, but with either a 120-s auditory or a 10-s light stimulus as a CS, resulted in more robust PIT. We also examined the reliability of our previous failure to observe PIT.

Methods

Three experiments were conducted examining whether PIT was obtained using (1) a 120-s light stimulus, (2) a 10-s light stimulus, or (3) a 120-s auditory stimulus as CSs.

Results

We found PIT was not obtained using (1) a 120-s light stimulus as a CS, (2) a 10-s light stimulus as a CS, or (3) a 120-s auditory stimulus as a CS.

Conclusions

These results suggest that CS form does not account for our earlier failure to see PIT. Rather, factors like rat strain or how ethanol drinking is induced may account for when PIT is or is not observed.

Keywords: Alcoholism, Ethanol Self-Administration, Operant Behavior, Craving, Relapse

Introduction

Associative learning is widely thought to play an important role in alcoholism (Hogarth et al 2013; Koob et al 1989), particularly in relapse (de Wit & Stewart 1981; Wikler 1948). However, isolating this role can be difficult with most commonly used procedures (see Lamb et al 2016c). One procedure thought to effectively isolate the role of associative learning upon operant responding, like drug seeking, is Pavlovian-Instrumental-Transfer (PIT; Estes, 1943). In PIT, the response – reinforcer (or Unconditioned Stimulus; US) relationship and the Conditioned Stimulus (CS) – US relationship are trained separately, and then the effects of the CS upon responding is examined when both the response – reinforcer and the CS – US relationships are in extinction. We recently conducted two studies examining PIT using an ethanol-paired CS (Lamb et al 2016a). In one of these studies, we found PIT; that is, the CS increased responding for ethanol. However, in the other study, we did not find PIT.

These results appear to contradict each other, and the failure to find PIT in the one study appears to contradict other studies finding PIT using an ethanol-paired CS (Krank 2003; Glassner et al 2005; Corbit & Janak 2007, 2016; Krank et al 2008; Milton et al 2012). While many things will influence the Conditioned Responses (CR) elicited by a CS, two important factors are the CS and the US (Holland 1977; Holland 1979; Kearns & Weiss 2004). The CS used in our studies differed from the CSs used in the previous studies along potentially important dimensions. The CS used in our studies was the lighting of a cue light located above where the response lever was normally located for 120-s. Glassner et al, Corbit & Janak, and Milton et al all used a 120-s presentation of an auditory stimulus. Krank and Krank et al used a localized cue light that was lit for 10-s and found PIT when the cue light was located near the lever on which responding was reinforced, but not when the light was located away from this lever.

Both the modality of the CS and its duration can influence the CR elicited by a CS (Holland 1977). For instance, a short localized light presentation paired with a positive valenced CS, like food, will often elicit approach towards the CS. Consistent with this, Krank observed approach towards the CS in his experiments. Further, when this approach brought the rat nearer the lever on which responding had been reinforced, responding increased. However, when this approach took the rat away from the lever, responding decreased or was unchanged. Thus, it may be that our failure to find PIT was a result of the 120-s light presentation being too long to elicit much approach. The other studies used a 120-s auditory stimulus. Auditory and visual stimuli of equal duration can elicit different CRs (Holland 1977), it may be that the CR elicited by a 120-s auditory CS facilitated responding, while the CR elicited by a 120-s visual stimulus did not. Thus, the form of the CS used in our previous experiment may not have been optimal for showing PIT.

The present experiments were designed to address this possibility and one even simpler alternative explanation, i.e., that our previous result was a false negative. The current report consists of three experiments. The first is an exact replication of the experimental group in our previous report that failed to observe PIT. Thus, assessing the likelihood of the previous negative finding being a false negative. The second experiment used training and testing conditions similar to those used by Krank (2003) with 10-s localized light CSs. The third and last experiment used training and testing conditions similar to Corbit & Janak (2007) with120-s auditory CSs. Note, these last two experiments were designed to assess the extent to which our earlier failure to observe PIT was the result of CS form rather than an attempt to assess the repeatability of the earlier results of Krank or Corbit & Janak, which have been demonstrated by the several experiments contained within each of those reports and by subsequent publications (see Krank et al 2008 and Milton et al 2012; Corbit & Janak 2016).

It is also important to note that at least two findings in our earlier report (Lamb et al 2016a) argue against the possibility of CS form being responsible for the lack of PIT. First, we replicated that experiment using food instead of ethanol and found PIT. Second, when rats responded for ethanol and for food under a concurrent Fixed Ratio schedule, the 120-s light CS did produce PIT. Thus, while our previous results would argue against our failure to find PIT being a result of CS form, the reported experiments were designed to eliminate these simpler explanations along with the even simpler explanation that our earlier result was a false negative. However, if one of these simpler explanations did prove true, this would have two potentially useful outcomes. First, it would provide a reliable preparation with which to study the role of associative learning in alcoholism; and second, it would provide a better understanding of the boundary conditions of this preparation, which might provide insight into the behavioral mechanisms operating in PIT (see Sidman 1960). However, if these simpler explanations prove unlikely, then this would focus our attention on the potential role of other factors, such as the US, rat strain, etc. in the expression of PIT, topics to which we return to in the discussion.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

All procedures conducted on the rats were approved by the local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (2011). Male Lewis rats weighing between 260 and 285 grams were purchased from Charles River. Rats were individually housed, and for approximately two-weeks were allowed unrestricted access to food and water. After this, food was restricted to 12 to 15 gram per day, but water was freely available except as noted below.

Eight rats were used in Experiment 1 that replicated the results of our previous experiment examining PIT with a 120-s light CS with rats responding under an Random Interval (RI) schedule of ethanol delivery (Lamb et al 2016a). Sixteen rats were used in Experiment 2 that was similar to the experiment of Krank (2003) using 10-s light CSs that were located either over the response lever or away from the lever with rats also responding under an RI schedule of ethanol delivery. Eight were randomly assigned to a paired group and 8 to an explicitly unpaired group. As eight operant chambers were used, two sets of eight rats were run in sequential sessions; and randomization was blocked by session and then stratified by the number of responses made such that half the rats above or below the median in that session were assigned to each group. Finally, 8 rats were used in Experiment 3, which was similar to that of Corbit & Janak (2007) using a 120-s auditory stimulus with rats responding under a Random Ratio (RR) schedule of ethanol delivery, were randomly assigned such that half the rats had the clicker as a CS and the tone as an unpaired stimulus, and the other half the tone as a CS and the clicker as an unpaired stimulus. Note that rats were not randomly assigned to experiments and thus, statistical comparisons among the three experiments would be of dubious validity.

Apparatus

Experiments occurred in eight commercially available operant chambers (ENV-008, Med-Associates, Georgia, VT) with two levers arranged on either side of one wall with a light above each and a houselight above the chamber on the opposite wall. A magazine was positioned between the levers where rats could access food pellets (45 mg chow flavored, BioServ, Frenchtown, NJ) and solutions (via a 0.1 mL dipper mechanism) when they were delivered. Chambers were also equipped with a speaker connected to a tone generator (ANL-926, Med-Associates, Georgia, VT). Stimuli presentation, reinforcement delivery, and response recording were controlled using a program written and executed with commercially available software (Med-PC IV, Med-Associates, Georgia, VT). Operant chambers were housed in ventilated, light and sound attenuating cubicles (ENV-022V, Med-Associates, Georgia, VT). Pink noise was generated in the room housing operant equipment to further isolate tones within the operant chamber.

Induction of Ethanol Drinking

For one week, rats were given 16% (w/v) ethanol in their home cage along with a bottle containing only water for 24-h on Monday, Wednesday & Friday. Starting the following week, at mid-day rats were fed their daily food ration. Two hours prior, drinking water was removed and one hour before feeding another bottle containing an 8% ethanol solution was placed in the cage and remained available for two hours (i.e., until one hour after food was presented). This was done each weekday for 11 weeks.

Experiment 1: 120-s light CS, RI ethanol responding

Procedures in Experiment 1 were similar to those in Experiment 1 of Lamb et al (2016a) for the paired group in that experiment.

Ethanol Self-administration

Self-administration sessions lasted one hour, during these an 8 kHZ, 80 dB tone sounded. In the first session, 3-s presentations of a 0.1 ml dipper filled with 8% (w/v) ethanol occurred under a Random Time (RT) 10-s schedule. Subsequently, ethanol was delivered for each lever press, then under a Random Interval (RI) 20-s schedule and finally under a RI 30-s schedule. Ethanol self-administration training took 58 sessions.

Pavlovian Conditioning

This phase followed training on ethanol self-administration. Ten sessions were conducted during this phase and during these sessions the response levers were removed from the experimental chambers. Pavlovian conditioning sessions were 60 min long. Every third minute there was a 50% probability of turning on the cue light located over where the ethanol lever had been for 120 -s. While this light was lit, 4- s presentations of ethanol occurred under an RT 25 s schedule (with the RT schedule not operating during the dipper presentation and the probability query window set to 1 s).

Test Session

Following the ten Pavlovian Conditioning sessions, the levers were returned to the experimental chambers and on the next two days rats responded on an RI 30 s schedule of ethanol delivery. Following this, a test session was conducted. In the 28 min test sessions, the tone sounded constantly. After 4 min, the light above the ethanol lever came on for 120-s. This cycle repeated itself 4 times and then 4 min of the tone alone occurred after which the test session ended. This test occurred in extinction, i.e., ethanol was not presented.

Experiment 2: 10-s light CS (near and far from the lever), RI ethanol responding

Procedures in Experiment 2 were based on those in Experiment 1 of Krank (2003).

Ethanol Self-administration

Self-administration sessions lasted 30 min and the houselight was on during this time. In the first session, 3-s presentations of 0.1 ml dipper containing 8%(w/v) ethanol occurred under a Random Time 10-s schedule. Subsequently, each lever press resulted in a dipper presentation. Following this training the response requirement was changed to a Random Interval 10-s schedule of dipper delivery. Ethanol self-administration training took 58 sessions.

Pavlovian Conditioning and Unpaired-Exposure

Ten sessions were conducted during this phase and during these the response levers were removed from the experimental chambers. Pavlovian conditioning sessions consisted of 20 ethanol light pairings. Half of these pairings were with the light located above where the response lever was normally located. The other half was with the light located on the other side of the panel. The 10-s light CS was followed by US delivery. The US consisted of two 3-s presentations of a 0.1 ml dipper containing 8% ethanol separated by a 1.5-s refill period and followed by a 2.5-s period when the dipper was down. The Inter-Trial-Interval (ITI) averaged 100-s and ranged from 20 to 180 s. Light presentations occurred in the same manner for the unpaired group. However, the 20 US deliveries occurred according to a RT schedule during the ITI with the constraint that these did not occur during the first or last 10-s of the ITI.

Test Session

The test session was identical to the Pavlovian Conditioning and Unpaired Exposure sessions with two exceptions: (1) the lever was returned to the chamber; and (2) no ethanol was delivered either response independently or contingent upon a response.

Experiment 3: 120-s auditory CS, Random Ratio ethanol responding

Procedures in Experiment 3 were based on those in Experiment 1 of Corbit & Janak (2007). Note that in Corbit & Janak’s experiment Pavlovian Conditioning preceded self-administration training.

Pavlovian Conditioning and Unpaired-Exposure

During experimental sessions the houselight was lighted. In the first session, 3-s presentations of the 0.1 ml dipper containing 8%(w/v) ethanol occurred under a Random Time 10-s schedule. In the subsequent 8 sessions, Pavlovian Conditioning occurred. During these 75-min sessions the response levers were removed from the experimental chambers. Pavlovian conditioning sessions consisted of either 6 ethanol 120-s clicker (80 dB, 5 HZ) pairings or 6 ethanol 120-s tone (80 dB, 8kHZ) pairings. The rats for whom the tone was paired with ethanol received six 120-s presentations of the clicker in each session without ethanol delivery. The rats for whom the clicker was paired with ethanol received six 120-s presentations of the tone without ethanol delivery. The ethanol US consisted of two 3-s presentations of a 0.1 ml dipper containing 8% ethanol separated by a 1.5-s refill period and followed by a 2.5-s period when the dipper was down, and was delivered during the CS under a RT 22.5-s schedule that did not run during US deliveries. The Inter-Trial-Interval (ITI) between tone and clicker presentations averaged 300-s and ranged from 180 to 420 s.

Ethanol Self-administration

Self-administration sessions lasted 60 min. Initially, each lever press resulted in a dipper presentation. Following this training the response requirement was changed to a Random Ratio 5 schedule of dipper delivery across sessions. Ethanol self-administration training took 62 sessions.

Test Session

Following ethanol self-administration training, rats were given one reminder session of Pavlovian Conditioning followed by a single self-administration session, then the test session was conducted. During the test session, levers were returned to the chamber and the tray containing 8% ethanol was present. However, no ethanol was ever delivered. Test sessions began with 120-s during which neither the tone or clicker were presented. This was followed by 120-s presentations of the tone (T) and clicker (C) in the following order TCCTTC with each presentation separated by a 180-s ITI during which neither the tone or the clicker sounded. This was followed by 180-s when neither the tone nor clicker sounded.

Analysis Plan

The experimental question in each experiment was whether the ethanol paired stimulus increased responding. In Experiment 1, this was addressed by examining whether the change score (responding in the presence of the stimulus minus responding in the period that preceded it) was different than zero using a t-test. In Experiment 2 the experimental question was addressed by comparing change scores for response rate (during stimulus rates minus pre-stimulus rates) between the paired and unpaired groups for each location separately using a t-test. In Experiment 3 the experimental question was addressed by examining if the change score calculated as responding during the paired stimulus minus responding during the unpaired stimulus was different from zero using a t-test (essentially a paired t-test). STATA version 14.1 (STATA Corp; College Station, TX) was used.

Results

Experiment 1

Baseline Responding & Conditioning

Responding varied substantially between rats with the mean number of responses in the last five sessions ranging from 17.0 to 124.8 and the number of ethanol presentations ranging from 12.8 to 56.0. The mean number of responses was 47.9 (SD=36.1) with a median of 35.4 (IQR 22.4–62.9). The mean number of ethanol presentations was 26.8 (15.1) with a median of 22.3 (15.2–35.1). The amount of ethanol earned during these sessions ranged from 0.31 to 1.37 g/kg with a mean value of 0.65 (0.37) and a median value of 0.54 (0.37 – 0.85). On all but the first day during Pavlovian Conditioning, the distribution of magazine entries was consistent with learning occurring with rats making more magazine entries when the light CS was on than when the light was off. However, as some of these entries during the CS will be in response to the raising of the dipper (US delivery), number of magazine entries is not a good measure of learning in this situation.

Responding during the Test Session

There was no evidence that responding that had previously been reinforced by ethanol delivery was increased by presentation of the light that had been paired with ethanol. As can be seen in Figure 1, the number of responses during the 120-s light presentations minus the number of responses in the 120 s that preceded the light presentation ranged from −3 to 6 with a median value of 0.5 (−1 – 3). The mean change score was 1 (3.0), and the mean was not reliably different from zero (t(7)=0.95, p=0.37). Mean change score for magazine entries drug the CS was 1.3 (5.8), and this value was not reliably different from zero (t(7)=0.6; p=0.56)

Figure 1.

The effects of a 120-s ethanol-paired light located over the response lever on responding for ethanol that is in extinction. The number of responses during light presentations minus the number of responses in the 120-s periods that precede light presentations is plotted for each of eight rats. The gray bar at zero marks where the number of responses during the CS is equal to the number of responses that occurred in the period before it. Points above the gray bar would indicate an increase in responding and points below it a decrease in responding.

Experiment 2

Baseline Responding & Conditioning

While there was great variation in both responding (range of means for last five sessions across rats: 11.8 – 99.6) and number of ethanol deliveries earned (8 –50), the Paired and UnPaired groups were similar. The median number of responses made was 23.9 (18.5–42.4) in the Paired and 45.9 (19.9–50.3) in the UnPaired groups. The mean responses made were 35.6 (28.6) and 38.0 (18.0) and these values did not differ reliably (t(14)=0.2, p=0.85). The median number of ethanol presentations earned was 17.9 (13.7–31.1) and 28.9 (15.1–35.2), which resulted in 0.44 (0.33– 0.76) and 0.71 (0.37 – 0.86) g/kg ethanol being earned. The mean number of dipper presentations were 23.4 (13.6) and 25.7 (11.8) and these did not differ reliably (t(14)=0.4, p=0.71). The Paired group made more magazine entries during the 10-s light presentations than the UnPaired group. The mean number of magazine entries during light presentations in the Paired group was 15.5 (5.8) compared to 7.3 (5.3) in the UnPaired group, a reliable difference (t(14)=3.0, p=0.01). Median values were 14.5 (11.5–19.5) and 6.5 (4.5–8). Conditioning of magazine entries to light presentations appear to be more robust when the light was located away from where the lever had been positioned. Mean number of magazine entries during presentation of this light was 9.5 (1.5) in the Paired compared to 5.0 (1.5) in the UnPaired group and this difference was statistically reliable (t(14)=2.9, p=0.02 with Welch correction for unequal variances). While for presentations of the other light the Paired group made more magazine entries than the UnPaired group (6 (5.3) v. 2.3 (1.9)), these values were not reliably different statistically (t(14)=1.9, p=0.09). As dipper presentations occurred following the end of the CS, these magazine entry results are consistent with learning occurring; particularly when the CS was located away from the response lever.

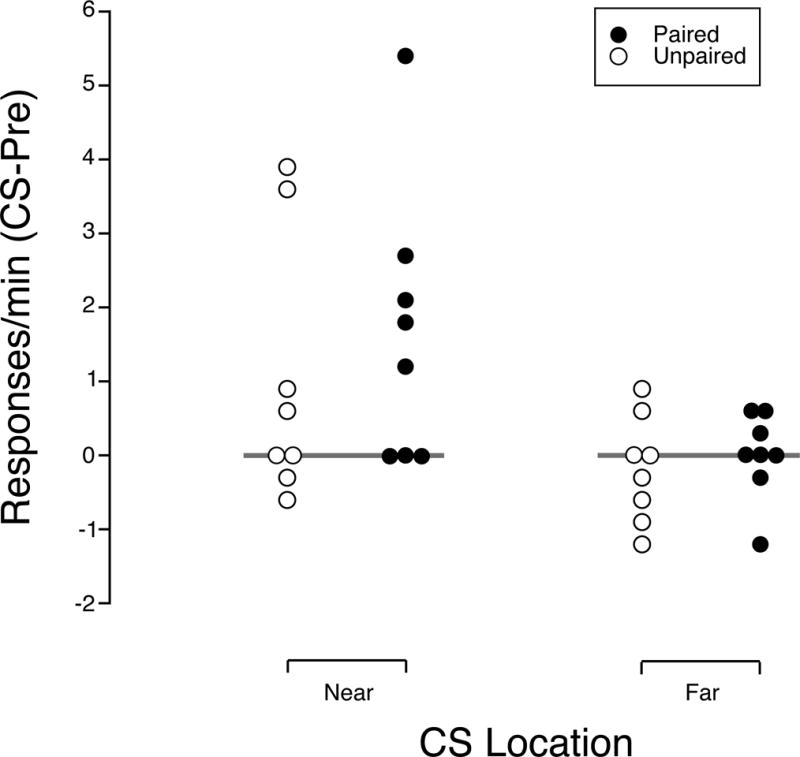

Responding during the Test Session

There was some evidence that responding was increased when the ethanol-paired CS was located near the response lever, but there was no evidence that responding was increased when the CS was located away from the response lever (Figure 2). The change score for the rate of responding when the CS was located near the response lever ranged from 0 to 5.4 responses/min with a median of 1.5 (0 – 2.4) in the paired group compared to change scores ranging from −0.6 to 3.9 with a median of 0.3 (−0.2 – 2.3) in the unpaired group. The mean change score when the CS was located near the response lever was 1.7 (1.8) in the paired group compared to 1.0 (1.8) in the unpaired group. These means were not reliably different (t(14)=0.7, p=0.49). However, the mean for the paired group was reliably greater than zero (t(7)=2.5, p=0.04), but this was not the case in the unpaired group (t=1.6, p=0.15). When the CS was located away from the response lever, change scores ranged from-1.2 to 0.6 in the paired group with a median of 0 (−1.2 – .45) in the paired group compared to a range of −1.2 to 0.9 and a median of −0.2 (−0.8 – 0.3) in the unpaired group. The mean change score was 0 (0.6) in the paired group and −0.2 (0.7) in the unpaired group, and these means did not reliably differ (t(14)=0.6, p=0.57). Also, neither mean was reliably different from zero (paired: t=0.0, p=1.00; unpaired: t=0.7, p=0.48). Additionally, there was evidence that the response to the CS varied by location in the paired group (t=2.5, p=0.04), but this evidence was less reliable in the unpaired group (t=2.2, p=0.07). Similar to what was seen during the Pavlovian Conditioning sessions, change scores for magazine entries during the CS was greater in the Paired than the UnPaired group when the CS was located away from the response lever (t(14)=4.0,; p=0.001), but not when the CS was located over the response lever (t(14)=1.3; p=0.20).

Figure 2.

The effects of a 10-s light either located over the response lever on responding for ethanol that is in extinction or away from the response lever. In one group of eight rats light presentations had been paired with ethanol delivery, while in another group of eight rats the light was explicitly unpaired with ethanol deliveries. The response rate during light presentations minus the response rate in the 10-s preceding light presentations is plotted for each rat. The gray bar at zero marks where the response rate during the CS is equal to the response rate in the 10-s before it. Points above the gray bar would indicate an increase in responding and points below it a decrease in responding.

Experiment 3

Baseline Responding & Conditioning

The mean number of responses per session for the last five sessions before beginning Pavlovian conditioning ranged from 11.4 to 72.2 with a median of 17.9 (15.6 – 27.1) and a mean of 25.6 (20.0). The number of ethanol presentations earned ranged from 1.6 to 15.4 with a median of 4 (3.4 –6.1) and a mean of 5.5 (4.3), which result in a median of 0.01 (0.01 – 0.01) g/kg ethanol being earned. Neither the mean number of responses (t(6)=0.9, p=0.41) nor mean number of dipper presentations (t(6)=0.9, p=0.38) differed between the rats assigned the click as a CS and those assigned the tone as a CS. Data for the fifth of eight Pavlovian conditioning sessions was lost. In the remaining sessions 4 of 8 rats made more magazine entries during the CS than the UnPaired stimulus in all of these 7 sessions, 2 rats in 6 and 2 rats in 5, and all rats made more magazine entries during the CS than the unpaired stimulus in the last training session. However, as with Experiment 1, while this pattern of magazine entries is consistent with learning occurring, magazine entries during the CS likely are also a result of dipper deliveries.

Responding during the Test Session

There was no evidence that the CS increased responding that had been reinforced with ethanol compared to the unpaired stimulus. As can be seen in Figure 3, responses in the presence of the CS minus responses during the unpaired stimulus during the test session ranged from −8 to 7 with a median of 2 (−3 – 4) and a mean of 0.6 (4.9). The mean was not reliably different from zero (t(7)=0.4, p=0.73). Magazine entries during the paired stimulus minus magazine entries during the unpaired stimulus, also, did not reliably differ from zero (t(7)=2.0; p=0.09; mean= −5.9(2.9)).

Figure 3.

The effects of a 120-s ethanol-paired auditory stimulus on responding for ethanol that is in extinction. In half the rats a tone was paired with ethanol deliveries and in the other half a clicker. The other stimulus was explicitly unpaired with ethanol delivery in each group of rats. The number of responses during alcohol-paired stimulus minus the number of responses in the unpaired stimulus is plotted for each of eight rats. The gray bar at zero marks where the number of responses during the CS is equal to the number of responses that occurred during the unpaired stimulus. Points above the gray bar would indicate an increase in responding during the CS and points below it a decrease.

Discussion

In the current experiments, PIT was not seen when the ethanol-paired CS was a 120-s light presentation, a 10-s light presentation, or a 120-s auditory stimulus. While there was a significant increase in lever responding during the 10-sec light stimulus near the lever in experiment 2, this increase was not significantly different from the unpaired light presented near the lever, and responding for the unpaired light was also increased, though not significantly. This argues against these results of experiment 2 being PIT. Overall, these results suggest that our previous failure to see PIT with an ethanol-paired CS (Lamb et al 2016a) was neither a false negative nor a function of the form of the CS used. Other results from our previous study also buttress this assertion. The present findings are at odds with the results of previous studies finding PIT with an ethanol-paired CS using either a 120-s auditory stimulus or a 10-s light presentation (Krank 2003; Glassner et al 2005; Corbit & Janak 2007, 2016; Krank et al 2008; Milton et al 2012). This discrepancy likely results from one of the many variables (e.g., rat strain, method of inducing drinking, presence of another reinforcer, amount of ethanol earned etc.) that differed between the studies, and points to their potential importance in influencing the effects of an ethanol-paired CS on responding for ethanol. Such a possibility is most consistent with an interpretation of PIT resulting from CRs elicited by the CS rather than CS-elicited changes in motivation.

Previously, we reported an absence of PIT when a 120-s light stimulus had been paired with ethanol. We replicated this finding in the current set of experiments. The effects seen in this study and the previous one (Lamb et al 2016a), mean change scores of 1.0 (3.0) in the current study and 0.3 (4.4) in the previous report, are essentially identical. The failure to see PIT in either study does not appear to be a power issue, and combining the data from both studies would still result in a change score close to zero. Thus, a failure to see PIT with an ethanol-paired CS under these conditions appears to be a reliable and replicable result.

This failure to observe PIT under these conditions stands in contrast to other reports in which PIT was observed (Krank 2003; Glassner et al 2005; Corbit & Janak 2007, 2016; Krank et al 2008; Milton et al 2012; and Lamb et al 2016a experiment 3). The studies from other laboratories that reported PIT with an ethanol-paired CS had used either a 120-s auditory stimulus or a 10-s light presentation as a CS compared to the 120-s light that was used when PIT was not seen. The form of the CS, however, does not explain why PIT was not seen with a 120-s light CS. When either a 120-s auditory stimulus or a 10-s light was used as a CS under conditions similar to those used in studies when PIT was not observed, PIT was still not observed (Experiments 2 & 3 of this report), suggesting that CS form is not responsible for the differences between the studies.

The nature of the US is also an important determinant of the CR elicited by a CS (Holland 1979); and this may have differed between the studies demonstrating and not demonstrating PIT. In particular it may be that when the US has a more food-like nature, PIT may be more easily demonstrated than when the US has a less food-like nature. When the US is food, PIT can be demonstrated under the conditions used in experiment 1 of this report and experiment 1 of our previous report (Lamb et al 2016a experiment 2). Further, when food (Lamb et al 2016a experiment 3) or sucrose (Corbit & Janak 2007 experiment 2) is available concurrently, PIT can be demonstrated. Additionally, when sweeten ethanol is used as the US (Krank 2003; Glassner et al 2005) or rats are induced to drink ethanol using either a sucrose or saccharin fading procedure (Corbit & Janak 2007 experiment 1; Krank e al 2008; Milton et al 2012), PIT can be demonstrated. Thus, in all but one study (Corbit & Janak 2016) in which PIT has been demonstrated, there might be some reason to suspect that an association with food or sweet taste changed the nature of the ethanol CS. Notably, using sweeten ethanol, or a sucrose or saccharin fading procedure might make the ethanol US in these rat experiments more like the ethanol US in human drinking, -few people begin drinking alcohol by drinking unflavored, unsweetened warm alcohol solutions (see Gauvin et al 1993.

Another difference between experiments demonstrating PIT and those not demonstrating PIT is the strain of rats used. All the studies not finding PIT with an ethanol-paired CS used Lewis rats (this study and Lamb et al 2016a experiment 1). All but one experiment (experiment 3 Lamb et al 2016a) finding PIT with an ethanol-paired CS used other strains: Glassner et al, Corbit & Janak, and Krank et al used Long-Evans rats; Milton et al used Lister Hooded rats; and Krank used Sprague Dawley rats. Different strains of rats have different propensities to emit particular CRs in response to a CS paired with a particular US (Andrews et al 1995; Kearns et al 2006). Thus, an ethanol-paired CS may elicit CRs more likely to result in PIT in strains other than the Lewis rat.

The reported studies provide evidence that previous failures to see PIT are not a result of CS form. However, these results should not be interpreted as a failure to replicate experiments in which PIT was observed with ethanol-maintained behavior using these CS-Forms (Corbit & Janak 2007, 2016; Krank 2003; Krank et al 2008; Milton 2012; Glassner 2005; Lamb et al 2016a experiment 3). As has been outlined above there are important differences between the present experiments and the previous experiments such as rat strain and how likely the ethanol-US is to be treated like food that may explain the discrepant results. Other differences, such as ethanol self-administration training length also exist, though this might be expected to improve the chances of seeing PIT in the present experiments (see Corbit & Janak 2016).

What was or was not conditioned and the adequacy of the comparisons may influence how our results should be interpreted. The absence of PIT may reflect either a lack of effective Pavlovian conditioning, or the development of a CR that interferes with the expression of PIT. The range of CRs measured in these and our previous experiments limits our ability to address this possibility in any comprehensive manner. However, clearly similar Pavlovian training procedures produce adequate conditioning to produce PIT with food (e.g. Lamb et al 2016a Experiment 2) or with ethanol under other circumstances (e.g., Lamb et al 2016a Experiment 3; Corbit & Janak 2007, 2016; Krank 2003; Krank et al 2008). Additionally, in Experiment 2 of this report, magazine entries were increased in response to the CS showing that Pavlovian Conditioning had occurred. Further, we previously showed that partial extinction of Pavlovian conditioning does not reveal PIT as would be expected if a CR was interfering with its expression using the Pavlovian and Instrumental training and the testing procedures used in Experiment 1 (Lamb et al 2016a experiment 1).

The comparisons made in the various studies also must be considered (see Lamb et al 2016c). Comparisons to responding immediately proceeding CS presentation to responding during the CS presentation usefully controls for between subject differences in overall propensity to respond and changes in this propensity as extinction occurs during the test session (e.g., experiment 1 of this report and Glassner et al 2005). However, such comparisons do not control for any potential non-associative excitatory or inhibitory properties that the stimuli used as CSs or USs might have. Likely, the best control condition for studies like these is the Truly-Random-Control procedure (Rescorla 1967). This procedure presents both the stimulus used as the CS and the stimulus used as the US in the conditioning procedure randomly throughout the experimental session at an overall frequency identical to that of the conditioning sessions. This controls for the non-associative excitatory or inhibitory effects of the stimuli used as CSs and USs without potentially imbuing the stimulus used as a CS with inhibitory properties as might happen in explicitly unpaired control conditions (experiments 2 & 3 of this report, Krank 2003; Corbit & Janak 2007, 2016; Krank et al 2008; Milton et al 2012). Only two experiments examining PIT using ethanol-maintained responding have used a Truly-Random-Control procedure: one found PIT (Lamb et al 2016a experiment 3) and one did not (Lamb et al 2016a experiment 1). Thus, from the existing body of work the conditions under which PIT can be seen with ethanol-maintained behavior is not totally clear, but at least under some conditions an ethanol-paired CS will increase responding for ethanol.

There are at least three broad ways that a CS might facilitate responding for the US. The CS might increase motivation for the US, i.e., function like an establishing operation (see Troisi 2013) such as food deprivation for food-maintained responding. The increase in responding seen following CS presentation is often attributed to such CS elicited changes in motivation. Sometimes, however, the increase in responding is not specific to the US with which the CS was paired. For instance, Corbit & Janak (2007) found that an ethanol-paired CS also increased responding for sucrose. This effect is often interpreted as a general increase in motivation or general PIT. Arguing against such a motivational interpretations are the findings of Krank (2003) and Krank et al (2008), which showed that a light serving as an ethanol-paired CS increased responding when located over the response lever, but decreased responding when located away from the lever. Clearly, if the ethanol-paired CS increased motivation, it should increase responding regardless of its location. The counter-argument is that while the CS increased motivation, the CS also elicited approach and this approach interfered with the expression of the increase in motivation. Support for such a claim can be found when partial extinction of the CS-US relationship results in PIT that was not seen before the partial extinction (e.g. LeBlanc et al 2012 in a study of cocaine self-administration; but see Lamb et al 2016a).

A second way that a CS might increase responding is by predicting the delivery of the outcome that reinforces responding (see Makintosh 1974 pp. 226–7). During extinction of the operant response, the US that had reinforced responding is not delivered. In the past, presentation of the CS predicted delivery of the US in that context. Thus, at least momentarily, presentation of the CS changes the context from one in which the US is not delivered to one in which the US will be delivered. This presumably makes the context more like the one in which responding had been reinforced. This greater similarity might be expected to increase responding.

The third way that a CS might increase responding is by eliciting a CR that increases the probability of a response (see Tomie 1995). For instance, Krank interpreted the increase in responding that he saw when the light CS was located near the response lever as resulting from the approach that the CS elicited. As he observed approach towards the light during CS presentations, and when the light was located near the lever, responding increased. However, when the light was located away from the lever, responding either decreased or was unchanged.

Of course, these different ways that a CS could facilitate responding are not mutually exclusive and would sometimes tend to blend together. Behavior could be increased both because motivation is increased and because the CS is located near the response lever with conflicting results seen when approach towards a localized CS competes with the motivational effects of the CS. Similarly, behavior could be facilitated not only because a context in which the US is delivered is more similar to the context in which responding has been reinforced, but also because entries into the goal magazine often precede and set the occasion for responses.

Still, we think that our recent results are most consistent with responding being facilitated by the particular CR elicited by the CS rather than by CS-elicited increases in motivation or the CS predicting US delivery making the context more similar to the context in which responding had been reinforced. The CS-US pairing situations in which we failed to observe PIT are very similar or identical to those situations in which PIT has been observed and there is little reason to believe that the CS would have the ability to increase motivation in some, but not others of these instances. Likewise, the CS-US pairings similarly predict US delivery in these various studies and why this should result in increases in responding in one situation yet have no effect on responding in other situations is also difficult to explain. However, the details that differ between the experiments finding PIT and those not finding PIT, such as the presence of food in the context or the strain of rat used, might well result in different CRs that are more or less likely to facilitate responding.

If it is the behavior elicited by an alcohol-paired CS that results in increased responding for alcohol, then reducing these CRs elicited by the CS should reduce the likelihood of increased responding for alcohol. Often, such CRs might in and of themselves seem of little consequence, e.g. gazing at a liquor bottle. However, each seemingly small change in behavior likely results in an increasing probability of actual alcohol-seeking. Once the probability of alcohol-seeking becomes greater than other readily available behaviors, alcohol-seeking occurs (Lamb & Ginsburg submitted; see Kacelnik et al 2011 for a nice discussion of this view on what behavior is “chosen”); and once alcohol-seeking occurs, it is likely to be reinforced. This in turn, increases the future probability of alcohol-seeking in that context. This “competition” between alcohol-seeking and other behavior means that while the allocation of behavior to alcohol-seeking can be reduced by ensuring its non-reinforcement (i.e., extinction), a more effective means of reducing alcohol-seeking is the reinforcement of alternative behavior (see Ginsburg & Lamb 2013a, 2013b, 2013c, 2015; Lamb et al 2016b).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant AA12337. CWS was supported by the NIH/NIDA Intramural Research Program. The excellent technical assistance of Jonathan Chemello was instrumental in the accomplishment of this work.

References

- Andrews JS, Jansen JHM, Linders S, Princen A, Broekkamp CLE. Performance of four different rat strains in the autoshaping, two-object discrimination and swim maze tests of learning and memory. Physiol Behav. 1995;57(4):785–790. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)00336-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbit LH, Janak PH. Ethanol-associated cues produce general pavlovian-instrumental transfer. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(5):766–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbit LH, Janak PH. Changes in the influence of alcohol-paired stimuli on alcohol seeking across extend training. Front Psychiatry. 2016;7:169. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Stewart J. Reinstatement of Cocaine-Reinforced Responding in the Rat. Psychopharm. 1981;75:134–143. doi: 10.1007/BF00432175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes WK. Discriminative conditioning. I. A discriminative property of conditioned anticipation. J Exp Psychol. 1943;32(2):150–155. [Google Scholar]

- Gauvin DV, Moore KR, Holloway FA. Do rat strain differences in ethanol consumption reflect differences in ethanol sensitivity or the preparedness to learn? Alcohol. 1993;10:37–43. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(93)90051-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasner SV, Overmier JB, Balleine BW. The role of Pavlovian cues in alcohol seeking in dependent and nondependent rats. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66(1):53–61. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg BC, Lamb RJ. A history of alternative reinforcement reduces stimulus generalization of ethanol-seeking in a rat recovery model. Drug Alc Dep. 2013a;129(1–2):94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg BC, Lamb RJ. Reinforcement of an alternative behavior as a model of recovery and relapse in the rat. Behav Processes. 2013b;94:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg BC, Lamb RJ. Shifts in discriminative control with increasing periods of recovery in the rat. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013c;37(6):1033–9. doi: 10.1111/acer.12048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg BC, Lamb RJ. Incubation of ethanol reinstatement depends on test conditions and how ethanol consumption is reduced. Behav Processes. 2015;113:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarth L, Balleine BW, Corbit LH, Killcross S. Associative learning mechanisms underpinning the transition from recreational drug use to addiction. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2013;1282:12–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland PC. Conditioned Stimulus as a determinant of the form of the Pavlovian Conditioned Response. J Exp Psychol: Animal Behav Processes. 1977;3(1):77–104. doi: 10.1037//0097-7403.3.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland PC. The effects of qualitative and quantitative variation in the US on individual components of Pavlovian appetitive conditioned behavior in rats. Animal Learn Behav. 1979;7(4):424–432. [Google Scholar]

- Kacelnik A, Vasconcelos M, Monteiro T, Aw J. Darwin’s “tug of war” vs. starlings’ “horse-racing”: how adaptations for sequential encounters drive simultaneous choice. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2011;65:547–558. [Google Scholar]

- Kearns DN, Gomez-Serrano MA, Wiess SJ, Riley AL. A comparison of Lewis and Fischer rat strains on autoshaping (sign-tracking), discrimination reversal learning and negative automaintenance. Behav Brain Res. 2006;169:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns DN, Wiess SJ. Sign-tracking (autoshaping) in rats: a comparison of cocaine and food as unconditioned stimuli. Learning Behav. 2004;32(4):463–476. doi: 10.3758/bf03196042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Stinus L, Le Moal M, Bloom FE. Opponent process theory of motivation: neurobiological evidence from studies of opiate dependence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1989;13(2–3):135–140. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(89)80022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krank MD. Pavlovian conditioning with ethanol: sign-tracking (autoshaping), conditioned incentive, and ethanol self-administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(10):1592–1598. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000092060.09228.DE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krank MD, O’Neill S, Squarey K, Jacob J. Goal- and signal-directed incentive: conditioned approach, seeking, and consumption established with unsweetened alcohol in rats. Psychopharm. 2008;196(3):397–405. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0971-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb RJ, Ginsburg Addiction as a BAD, a Behavioral Allocation Disorder. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2017.05.002. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb RJ, Ginsburg BC, Schinler CW. Effects of an ethanol-paired CS on responding for ethanol and food: Comparisons with a stimulus in a truly-random control group and to a food-paired CS on responding for food. Alcohol. 2016a;57:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2016.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb RJ, Maguire DR, Ginsburg BC, Pinkston JW, France CP. Determinants of choice, and vulnerability and recovery in addiction. Behav Processes. 2016b;127:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb RJ, Schindler CW, Pinkston JW. Conditioned Stimuli’s role in relapse: pre-clinical research on Pavlovian-Instrumental-Transfer. Psychopharm. 2016c;233:1933–194. doi: 10.1007/s00213-016-4216-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc KH, Ostlund SB, Maidment NT. Pavlovian-to-instrumental transfer in cocaine seeking rats. Behav Neurosci. 2012;126(5):681–689. doi: 10.1037/a0029534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makintosh NJ. The psychology of animal learning. Academic Press; London: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Milton AL, Schramm MJ, Wawrzynski JR, Gore F, Oikonomou-Mpegeti F, Wang NQ, Samuel D, Economidou D, Everitt BJ. Antagonism at NMDA receptors, but not beta-adrenergic receptors, disrupts the reconsolidation of pavlovian conditioned approach and instrumental transfer for ethanol-associated conditioned stimuli. Psychopharm. 2012;219(3):751–761. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2399-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals: Eighth Edition. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA. Pavlovian conditioning and its proper control procedures. Psychol Rev. 1967;74(1):71–80. doi: 10.1037/h0024109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidman M. Tactics of Scientific Research: Evaluating Experimental Data in Psychology. Basic Books, NY; NY: 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Tomie A. CAM - An animal learning model of excessive and compulsive implement-assisted drug-taking in humans. Clin Psychol Rev. 1995;15(3):145–167. [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JR. Perhaps more consideration of Pavlovian-Operant interaction may improve the clinical effeicacy of behaviorally based drug treatment programs. Psychol Rec. 2013;63(4):863–894. doi: 10.11133/j.tpr.2013.63.4.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikler A. Recent progress in research on the neurophysiologic basis of morphine addiction. Am J Psychiatry. 1948;105(5):329–338. doi: 10.1176/ajp.105.5.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]