Abstract

Effective disease monitoring provides a foundation for effective public health systems. This has historically been accomplished with patient contact and bureaucratic aggregation, which tends to be slow and expensive. Recent internet-based approaches promise to be real-time and cheap, with few parameters. However, the question of when and how these approaches work remains open.

We addressed this question using Wikipedia access logs and category links. Our experiments, replicable and extensible using our open source code and data, test the effect of semantic article filtering, amount of training data, forecast horizon, and model staleness by comparing across 6 diseases and 4 countries using thousands of individual models. We found that our minimal-configuration, language-agnostic article selection process based on semantic relatedness is effective for improving predictions, and that our approach is relatively insensitive to the amount and age of training data. We also found, in contrast to prior work, very little forecasting value, and we argue that this is consistent with theoretical considerations about the nature of forecasting. These mixed results lead us to propose that the currently observational field of internet-based disease surveillance must pivot to include theoretical models of information flow as well as controlled experiments based on simulations of disease.

ACM Classification Keywords: G.3. Probability and statistics: Correlation and regression analysis, H.1.1. Systems and information theory: Value of information, H.3.5. Online information services: Web-based services, J.3. Life and medical sciences: Health

Author Keywords: Disease, epidemiology, forecasting, modeling, Wikipedia

INTRODUCTION

Despite a rapid pace of advancement in medicine, disease remains one of the most tenacious challenges of the human experience. Factors such as globalization and climate change contribute to novel and deadly disease dynamics [107], as highlighted by recent events such as the 2014–2015 Ebola epidemic in West Africa [139] and the ongoing Zika crisis in the Americas [129].

The highest-impact approach for addressing this challenge is a strong public health system [56, 139], including effective and timely disease surveillance, which quantifies present and future disease incidence to improve resource allocation and other planning. Traditionally, this depends on in-person patient contact. Clinic visits generate records that are accumulated, and these results are disseminated, typically by governments. Given appropriate resources, this approach is considered sufficiently reliable and accurate, but it is also expensive and coarse. Further, it is slow. Measurements of present disease activity are not available, only measurements of past activity.

These problems have motivated a new, complementary approach: use internet data such as social media, search queries, and web server traffic. This is predicated on the conjecture that individuals’ observations of disease yield online traces that can be extracted and linked to reality. The anticipated result is estimates of present disease activity available in near real-time, called nowcasts, as well as forecasts of future activity informed by near real-time observations — as we will argue, a related but fundamentally different product.

This notion was well-received in both the popular press [66, e.g.] and the scientific literature. One of the first papers has been cited over 2,000 times since its publication in late 2008 [59]. Based on these results and amid the rush of enthusiasm, Google founded web systems, Google Flu Trends and Google Dengue Trends, to make nowcasts available to the public.

However, subsequent developments have led to increasing skepticism. For example, after significant accuracy problems [24] and scientific criticism [95], Flu and Dengue Trends folded in the summer of 2015 [154].

Among the numerous studies in the scientific literature, the details of how to process and evaluate internet traces are varied and scattered, as are experimental contexts. Further, we suspect many additional studies yielded negative results and were not published. That is, measuring disease using internet data works some of the time, but not always. We ask: when does it work and how does it work?

We address this question using Wikipedia. The present work is a large-scale experiment across 19 disease/country contexts curated for comparability on these two dimensions, using linear models atop Wikipedia traffic logs and an article filter leveraging relatedness information from Wikipedia categories [152]. This enables us to address four research questions motivated by the above conjecture and core question. These are:

RQ1. Semantic input filter. Does prediction improve when inputs are filtered for relatedness before being offered to a linear fitting algorithm? We found that using Wikipedia’s inter-article and category links as a proxy for semantic relatedness did in fact improve results, and that offering the algorithm unrelated yet correlated articles made predictions worse.

RQ2. Training duration. Does the amount of training data, measured in contiguous weekly data points, affect the quality of predictions? We found that our algorithm was less sensitive to this parameter.

RQ3. Forecast horizon. How far into the future can our algorithms predict disease incidence? In contrast to previous work, we found almost no forecasting value; even 1-week forecasts were ineffective.

RQ4. Staleness. How long does a given model remain effective, before it must be re-trained? We found that performance of good models deteriorated as staleness increased, but relatively slowly.

This paper is supported by open-source experiment code1 and a supplementary data archive2 containing our input and output data, early explorations of data and algorithms, and a machine-readable summary of our literature review.

Our contributions are as follows:

Answers to the research questions based on thousands of discrete experiments.

A literature review comprehensive in the areas of internet-based disease surveillance and Wikipedia-based measurement of the real world.

Data and code to support replication and extension of this work. We hope to provide a basis for a tradition of comparability in the field of internet-based disease surveillance.

A research agenda that we hope will lead to a more robust field able to meet the life-and-death needs of health policy and practice.

Our paper is organized as follows. We review the relevant literature, outline the design of our experiment, and present our results. We close with a discussion of what this really tells us and our proposals for how the field should best proceed.

RELATED WORK

This paper falls into four contexts: traditional patient- and laboratory-based disease surveillance, internet-based disease surveillance, Wikipedia-based measurement of the real world, and the latter two applied to forecasting. This section extends and adapts the literature review in our previous paper [57].

To our knowledge, this review is comprehensive in the latter three areas as of April 2016. A BibTeX file containing all of our references is in the supplement, as is a spreadsheet setting out in table form the related work attributes discussed below.

Traditional disease surveillance

Traditional forms of disease surveillance are based upon direct patient contact or biological tests taking place in clinics, hospitals, and laboratories. The majority of current systems rely on syndromic surveillance data (i.e., about symptoms) including clinical diagnoses, chief complaints, school and work absenteeism, illness-related 911 calls, and emergency room admissions [86].

For example, a well-established measure for influenza surveillance is the fraction of patients with influenza-like illness. A network of outpatient providers report the number of (1) patients seen in total and (2) who present symptoms consistent with influenza and having no other identifiable cause [28]; the latter divided by the former is known as “ILI”. Other electronic resources include ESSENCE, based on data from the Department of Defense Military Health System [16] and BioSense, based on data from the Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs, retail pharmacies, and Laboratory Corporation of America [15].

Clinical labs play a critical role in surveillance of infectious diseases. For example, the Laboratory Response Network, consisting of over 120 biological laboratories, provides active surveillance of a number of diseases ranging from mild (e.g., non-pathogenic E. coli and Staphylococcus aureus) to severe (e.g., Ebola and Marburg), based on clinical or environmental samples [86]. Other systems monitor non-traditional public health indicators such as school absenteeism rates, over-the-counter medication sales, 911 calls, veterinary data, and ambulance runs. Typically, these activities are coordinated by government agencies at the local or regional level.

These systems, especially in developed countries, are generally treated as accurate and unbiased.3 However, they have a number of disadvantages, notably cost and timeliness: for example, each ILI datum requires a clinic visit, and ILI data are published only after a delay of 1–2 weeks [28].

Internet-based disease surveillance

The basic conjecture of internet-based disease surveillance is that people leave traces of their online activity related to health observations, and these traces can be captured and used to derive actionable information. Two main classes of trace exist: sharing such as social media mentions of face mask use [112] and seeking such as web searches for health-related topics [59].4

In this section, we focus on the surveillance work most closely related to our efforts, specifically, that which uses existing single-source internet data feeds to estimate a scalar disease-related metric. We exclude from detailed analysis work that (for example) provides only alerts [38, 178], measures public perception or awareness of a disease [138], includes disease dynamics in its model [147,170], evaluates a third-party method [95, 120], uses non-single-source data feeds [38, 55], or crowd-sources health-related data (participatory disease surveillance) [34,35].

We also focus on work that estimates biologically-rooted metrics. For example, we exclude metrics based on seasonality [11,130], pollen counts [58,165], over-the-counter drug sales volume [82,98], and emergency department visits [52].

These traces of disease observations are embedded in search queries [5, 7, 9, 12, 14, 17, 21, 25, 26, 31, 32, 33, 39, 49, 50, 53, 59, 63, 64, 71, 72 73, 77, 78, 81, 85, 87, 90, 97, 103, 104, 109, 119, 126, 127, 131, 132, 141, 142, 144, 146, 157, 158, 162, 163, 166, 168, 169, 170, 173, 177, 179, 180, 182], social media messages [1, 2, 8, 10, 20, 36, 40, 41, 42, 46, 51, 60, 62, 68, 76, 84, 89, 92, 93, 115, 116, 118, 123, 124, 148, 149, 151, 176], web server access logs [57, 79, 101, 105], and combinations thereof [13, 19, 30, 91, 136, 143, 167].

At a basic level, traces are extracted by counting query strings, words or phrases, or web page URLs that are related to some metric of interest (e.g., number of cases), forming a time series of occurrences for each item. A statistical model is then created that maps these inputs to the official values of the metric. This model is trained on time periods when both the internet and official data are available, and then applied to estimate the metric over time periods when the official data are not available, i.e., forecasting the future and nowcasting the present. The latter is useful in the typical case where official data availability lags real time.

The disease surveillance work cited above has been applied to a wide variety of infectious and non-infectious conditions: allergies [87], asthma [136, 176], avian influenza [25], cancer [39], chicken pox [109, 126], chikungunya [109], chlamydia [42, 78, 109], cholera [36, 57], dengue [7, 31, 32, 57, 62, 109], diabetes [42, 60], dysentery [180], Ebola [5, 57], erythromelalgia [63], food poisoning [12], gastroenteritis [45, 50, 71, 126], gonorrhea [77, 78, 109], hand foot and mouth disease [26, 167], heart disease [51, 60], hepatitis [109], HIV/AIDS [57, 76, 177, 180], influenza [1, 2, 8, 9, 10, 13, 19, 20, 21, 30, 33, 40, 41, 43, 46, 48, 53, 57, 59, 68, 72, 73, 79, 81, 84, 85, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 97, 101, 103, 104, 105, 109, 115, 116, 118, 123, 124, 126, 131, 132, 141, 142, 143, 146, 148, 149, 151, 157, 163, 168, 170, 173, 179, 182], kidney stones [17], listeriosis [166], Lyme disease [14], malaria [119], measles [109], meningitis [109], methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) [49], Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) [158], obesity [42, 60, 144], pertussis [109, 116], plague [57], pneumonia [109, 131], respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) [25], Ross River virus [109], scarlet fever [180], shingles [109], stroke [60, 162], suicide [64, 169], syphilis [78, 127], tuberculosis [57, 180], and West Nile virus [25].

In short, while a wide variety of diseases and locations have been tested, such experiments tends to be performed in isolation and are difficult to compare. We begin to address this disorganization by evaluating an open data source and open algorithm on several dimensions across comparable diseases and countries.

Wikipedia

Wikipedia article access logs, i.e., the number of requests for each article over time, have been used for a modest variety of research. The most common application is detection and measurement of popular news topics or events [3, 6, 37, 70, 80, 83, 121, 171, 172]. The data have also been used to study the dynamics of Wikipedia itself [133, 155, 161]. Social applications include evaluating toponym importance in order to make type size decisions for maps [23], measuring the flow of concepts across the world [160], and estimating the popularity of politicians and political parties [171]. Finally, economic applications include attempts to forecast box office revenue [44, 108] and stock performance [29, 99, 113, 114, 164].

In the context of health information, the most prominent research direction focuses on assessing the quality of Wikipedia as a health information source for the public, with respect to cancer [96, 135], carpal tunnel syndrome [100], drug information [88], kidney conditions [156], and emerging infectious diseases [54].

A few health-related studies make use of Wikipedia access logs. Tausczik et al. examined public “anxiety and information seeking” during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, in part by measuring traffic to H1N1-related Wikipedia articles [153]. Laurent and Vickers evaluated Wikipedia article traffic for disease-related seasonality and news coverage of health issues, finding significant effects in both cases [94]. Aitken et al. found a correlation between drug sales and Wikipedia traffic for a selection of approximately 5,000 health-related articles [4], and Brigo et al. between news on celebrity movement disorders and Wikipedia traffic on topical articles [18]

A growing number of such studies map article traffic to quantitative disease metrics. McIver & Brownstein used Poisson regression to estimate the influenza rate in the United States from Wikipedia access logs [105]. Hickmann et al. combined official and internet data to drive mechanistic forecasting models of seasonal influenza in the United States [67]. Bardak & Tan assessed forecasting models for influenza in the U.S. based on Wikipedia access logs and Google Trends data, finding an improvement in both nowcasting and forecasting power when both were combined [13]. Finally, we previously found high potential of article traffic for both nowcasting and forecasting in several disease-location contexts [57].

In short, the use of Wikipedia access logs to measure real-world quantities is growing, as is interest in Wikipedia for health purposes. To our knowledge, the present work is the broadest and most rigorous test of this opportunity to date.

Forecasting

Of the internet data and Wikipedia surveillance studies discussed in the above two sections, 28 included a statistical forecasting component of some kind. (One used disease dynamics for forecasting [67], which is again out of scope for this review.) This forecasting falls into three basic classes: finding correlations, building models with linear regression, and building models with other statistical techniques.

Correlation analysis

The basic form of these 8 studies is to vary the temporal offset between internet and official data, either forecasting (internet mapped to later official) or anti-forecasting (internet to earlier official), and report the correlation. Thus, the claim is that a linear model is plausible, but no actual model is fitted and there is no test set. Various offsets have been tested, with up to ±7 months in one case [109].

Four of these studies report that forecasting is promising in at least some contexts [50, 79, 87, 109], while four report that it is not [101, 103, 126, 179]. Two studies report their best correlations at an anti-forecasting offset [50, 87].

This approach lacks a convincing explanation for why given offsets performed well or poorly. Rather, the goal of these studies appears to be to illustrate a relationship between internet and official data in a specific context, in order to motivate further work.

Linear regression

Extending the above analysis by one step is to actually fit the offset linear models implied by high correlation. We found 8 studies that did this. One used ridge regression [13], three used ordinary least squares [13, 57, 97], one “applied multiple linear regression analysis with a stepwise method” [169], one used a log-odds linear model with no fitting algorithm specified [167], and the rest did not specify a fitting algorithm [77, 131, 157]. We suspect that the latter four used ordinary least squares, as this is the most common linear regression algorithm. Again, the offsets tested varied.

Six of these studies reported positive results, i.e., that the approach was successful or promising in at least some contexts [13, 57, 77, 131, 167, 169], while two reported negative results [97, 157].

An important methodological consideration is whether a separate test set is used. This involves fitting the model on a training set and then applying the coefficients to a previously unseen test set; the alternative is to fit the model on a single dataset and then evaluate the quality of fit or estimates from the same dataset. The former is the best practice, while the latter is vulnerable to overfitting and other problems.

Three of the studies reporting positive results had no test set [57, 131, 169], two performed a single experiment with one training and one test set [77, 167], and one used cross-validation (multiple separations of the data into training/test pairs) [13]. Two of these studies, both reporting positive results, used Wikipedia data [13, 57].

Our work falls into this class, as we use elastic net regression [181] to test forecasting up to 16 weeks. Our experiment is much larger than any prior work, with thousands of individual training/test pairs, and each test is arranged in a realistic temporal arrangement with the test set immediately following the training set (as opposed to cross-validation, which intermingles them).

Other statistical techniques

A smorgasbord of other methods have been used to address the problem of statistical forecasting. All 12 of these studies reported positive results (though recall that negative results are less likely to be published). None used Wikipedia data.

The linear methods we found are linear autoregressive models [115, 124], stacked linear regression [143], multiple linear regression with a network component [43], and a dynamic Poisson autoregressive model [163]. We also found non-linear methods: matrix factorization and nearest neighbor models [30], support vector machines [143], AdaBoost with decision trees [143], neural networks [32], and matching meteorological data to historic outbreaks [21,151].

Further methods are time series-aware, using autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) Box-Jenkins models [9, 12, 32, 48]. These are applicable only to seasonal diseases.

Five of these studies used cross-validation [21, 32, 43, 48, 124], while six had one training and one test set [9, 30, 115, 143, 151, 163]. One did not specify the nature of validation [12].

It is quite plausible that statistical techniques other than linear regression can produce better models, though as we argue later, this should be supported by solid theoretical motivation for a specific technique.

We elected to use linear regression for several reasons. First, this is most common in prior work, and we wanted to reduce the number of dimensions on which ours differed. Second, in general, simpler methods are preferred; we wanted to find out the performance of linear regression before moving on to other things. Finally, our sense (as we explore in greater detail below) is that a better understanding of the data and the information pipeline is a higher priority than exploring the complex menu of statistical techniques.

That said, our open-source experimental framework can support evaluation of these and other statistical methods. This may be an opportunity to directly compare different methods.

EXPERIMENT DESIGN

This section describes the data sources we used and the design of our two experiments.

Overview

Our goal was to perform a large-scale experiment to evaluate our approach for internet data-based disease monitoring and forecasting across two dimensions: countries and diseases. We tested 19 contexts of 4 countries by 6 diseases at the same weekly time granularity.

We implemented the experiments in Python 3.4 with a variety of supporting libraries, principally Pandas [106] and Scikit-learn [125]. Our experiment code is open source, and brief replication guidance is included with the code.

Our analysis period is July 4, 2010 through July 5, 2015, i.e., 261 weeks starting on Sunday or Monday depending on the country. This period was selected somewhat arbitrarily as a balance between data availability and a larger experiment.

Data sources

We used three data sources: official disease incidence data, Wikipedia article traffic logs, and the Wikipedia REST API. All of the data we used are in the supplement.

Disease incidence data

We downloaded official disease incidence data from national government ministry of health (or equivalent) websites.5 In some cases, these raw data were in spreadsheets; in others, they were graphs presented as images, which we converted to numbers using WebPlotDigitizer [140]. Each disease/country context resulted in a separate Excel file, which we then collated into a single Excel file for input into the experiment.

Our goal was to select a tractable number of countries and diseases that produces a large number of disease/country pairs in the dataset, in order to facilitate comparisons. We had three general inclusion criteria:

Incidence data (number of cases) that are publicly available for the years 2010–2015 and reported weekly, to enable the same fine temporal granularity in every context.

Diseases diverse on various dimensions such as mode of transmission, treatment, prevention, burden, and seasonality. We ultimately selected six: chlamydia, dengue fever, influenza, malaria, measles, and pertussis.

Countries also diverse across the globe, targeting one per continent. Ultimately, we selected Colombia, Germany, Israel, and the United States. We found no African or Asian country that consistently reported high-quality data on sufficient diseases for a sufficient fraction of the study period.

This selection is a challenging optimization task due to the variety of national surveillance and reporting practices. We believe that the set we selected is illustrative rather than representative.

Of the 24 disease/country combinations above, we found data for 19, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of the main experiments. This shows the diseases and countries we studied with properties of each, as well a summary of each of the 19 contexts. Bold r2 indicates the high-performing contexts examined in more detail in the results section.

|

Country Total Wikipedia traffic from country [175] Language Country’s traffic in language [175] Total language traffic from country [174] Official data source |

Colombia 0.5% Spanish 89% 7.6% [75] |

Germany 7.5% German 75% 79% [74] |

Israel 0.5% Hebrew 54% 93% [111] |

United States 22% English 94% 42% [27] |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | Timing | |||||

| Chlamydia | erratic |

max(r2) root article total cases |

0.08 4.0×103 |

0.11 Chlamydia infection 3.4 × 106 |

||

|

|

||||||

| Dengue fever | seasonal |

max(r2) root article total cases |

0.91 Dengue 5.4 × 105 |

0.31 Denguefieber 4.0 × 103 |

0.07 1.9×101 |

0.33 Dengue fever 3.1 × 103 |

|

|

||||||

| Influenza | seasonal |

max(r2) root article total cases |

0.93 Influenza 2.3 × 105 |

0.77 Influenza 3.6 × 106 |

||

|

|

||||||

| Malaria | seasonal |

max(r2) root article total cases |

0.71 Malaria 3.2 × 105 |

0.06 6.0 × 102 |

0.24 Malaria 3.4 × 103 |

|

|

|

||||||

| Measles | erratic |

max(r2) root article total cases |

0.40 Sarampión 9.2 × 103 |

0.46 Masern 2.5 × 104 |

0.46 4.6× 102 |

0.49 Measles 6.5 × 102 |

|

|

||||||

| Pertussis | erratic |

max(r2) root article total cases |

0.59 Tos ferina 9.7 × 103 |

0.83 Keuchhusten 4.8 × 104 |

0.48 1.2 × 104 |

0.48 Pertussis 5.3 × 104 |

Wikipedia access logs

Summary access logs for all Wikipedia articles are available to the public.6 These contain, for each hour from December 9, 2007 to present and updated in real time, a compressed text file listing the number of requests for every article in every language, except that articles with no requests are omitted.7

If an article’s traffic during a month was less than 60 requests, we treated that entire month as zero; if all months had traffic below that threshold, we removed the article from our dataset. We normalized these request counts by language and summed the data by week, producing for each article a time series vector where each element is the fraction of total requests in the article’s language that went to that article. These weeks were aligned to countries’ reporting week (starting on Monday for Germany and Sunday for the other three countries).

We did not adjust for time zone between Wikipedia traffic data (in UTC) and official incidence data (presumably in local time). This simplified the analysis, and these offsets are relatively small compared to the weekly aggregation.

Wikipedia API

Wikipedia provides an HTTP REST API to the public.8 It is quite complex, containing extensive information about Wikipedia content as well as editing operations. We used it for two purposes: (1) given an article, get its links to other articles, and (2) given an article, get its categories. This study used the link and category state as of March 24, 2016.

We applied the latter iteratively to compute the semantic relatedness of two articles. The procedure roughly follows that of Strube and Ponzetto’s category tree search [152]:

Fetch the categories of each article.

If there are any categories in common, stop.

Otherwise, fetch the categories of the categories and go to Step 2.

We refer to this relatedness as category distance for specificity. The distance between two articles is the number of fetch cycles, capped at 8. A category encountered at different levels in the two expansions yields the greater level as the distance. An article’s distance from itself is 1.

Basic experimental structure

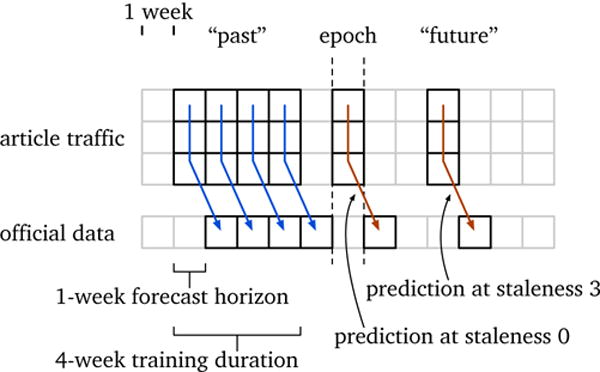

Our approach maps Wikipedia article traffic for a given week to official disease incidence data for the same or a different week, using a linear model. That is, we select a small subset of articles (order 10–1,000) and use a linear regression algorithm on some training weeks to find the best linear mapping from those articles’ request counts to the official case counts. We then apply these fitted coefficients to later, previously unseen article traffic and see how well the prediction matches the known incidence numbers. This approach is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of one model and its parameters, and how it fits into the weekly cadence of our experiments. The basic goal of a model is to map an article traffic vector, for some selection of articles, to official disease incidence (a scalar). The epoch is the current week from the perspective of the model, i.e., weeks before the epoch are treated as the past and weeks after the epoch as the future. We assume that official data are available until the week prior to the epoch (i.e., a 1-week reporting delay). The model’s training duration is the number of example weeks used to fit the model (here, 4 weeks); the last week of training data is always immediately before the epoch. Its forecast horizon is the temporal offset between the traffic vector and the official data; a value of zero is a nowcast and values greater are forecasts. Once fitted, the model can provide predictions; a prediction stale by 0 weeks uses the epoch’s article traffic; staleness greater than 0 use article traffic after the epoch.

The independent variables are:9

Epoch, i. Week used as the current, present week for the model. Priorweeks are the model’s past and used for training; later weeks are the model’s future and used for testing, along with the epoch. This approach follows how models are actually deployed — the most current data available are used for training, and then the model is used to predict the present and future.

Forecast horizon, h. Temporal offset between article traffic and official data. Traffic that is mapped to the same week’s official data is a horizon of zero, also called a nowcast; traffic mapped one week into the future is a one-week horizon, etc.

Training duration, t. Number of consecutive weeks of training data offered to the regression. The last week of incidence training data is immediately prior to the epoch; the last week of article traffic data is h weeks before the epoch.

Staleness, s. Number of weeks after the epoch that the model is tested. Article traffic on the epoch is staleness 0, traffic the week after the epoch is staleness 1, etc.

A model is a set of linear coefficients ωj and intercept ω0 that maps article requests A1 through An to official data I:

A model can produce one prediction per staleness s, at week i + s.

Accuracy is evaluated by creating a model sequence of models with consecutive epochs and the same horizon, duration, and staleness; this yields a time series of one prediction per model. We then compare the predicted time series to the official data using the coefficient of determination r2 ∈ [0, 1 (i.e. the square of the Pearson correlation r), which quantifies the fraction of variance explained by the model [117].

The key advantage of r2 is that it is self-normalizing and dimensionless, making it possible to compare models with different incidence units and scales. Also, it is widely used, making comparison with prior work possible. However, the metric does have disadvantages. In particular, it can be hard to interpret. Not only is it unitless, it cannot be used to assess sensitivity and specificity, nor answer questions like the number of infections identified by the model. As we argue below, future work should investigate more focused evaluation metrics.

Additional independent variables apply to model sequences:

Linear regression algorithm

To fit our linear models, we used elastic net regression [181], an extension of ordinary least squares regression with two regularizers. One minimizes the number of non-zero coefficients, and the other minimizes the magnitude of the coefficients.10 This reflects our desire for models using few articles and for setting roughly the same coefficients on articles whose traffic is correlated.

Elastic net has two parameters. α is the combined weight of both regularizers, which was chosen by Scikit-learn using cross-validation. ρ (called l1_ratio by Scikit-learn) is the relative weight between the two, which we set to 90% non-zero and 10% magnitude.

These choices were guided by data examination; we also considered lasso [159] and ridge regression [69] as well as setting the parameters manually or automatically. The Jupyter notebooks [128] that supported this examination are in the supplement.

Article filter

We used a two-stage article filter, using first article links and second category distance. For a given disease, we manually select a root article in English and follow Wikipedia’s inter-language links to find roots for the other languages (Table 1). This is the only manual step in our approach. The root article and all articles linked comprise the first group of candidates.

Next, we reduce the candidate pool to those articles whose category distance is at most some limit d ∈ ℤ ∪ [1, 8]. This yields anywhere from a dozen to several hundred articles whose traffic vectors are offered to the training algorithm (which itself selects a further subset for non-zero coefficients).

Experiments

We performed two experiments. Experiment 1 focuses on U.S. influenza, a context familiar to the authors and with excellent data, thus affording a more detailed analysis addressing all four research questions.

In Experiment 1, we tested category distances of 1–8 with and without confounding. That is, for the non-confounded control, we used a single root of “Influenza”; for the confounded case, we added two additional root articles: “Basketball” and “College basketball”. The goal was to offer the algorithm correlated but unrelated and thus potentially misleading articles, in order to test the hypothesis that purely correlation-based feature selection can be problematic.

This hypothesis is hinted at in Ginsberg et al. [59], whose feature selection algorithm was driven by correlation between search queries and ILI. This model ultimately included the 45 most-correlated queries, which were all influenza-related. However, of the 55 next-most-correlated queries, 19 (35%) were not related, including “high school basketball”. Models with up to the top 80 queries performed almost as well as the 45-query model, with varying correlation up to roughly 0.02 worse, and may have contained unrelated queries (Figure 1 in the citation). The 81st query was the unrelated “oscar nominations”, which caused a performance drop of roughly 0.03 all by itself. That is, one can imagine that slightly different circumstances could lead a Ginsberg-style model to contain unrelated, possibly detrimental queries.

The remaining independent variables are: 9 horizons from 0–16 weeks, 7 training durations from 16–130 weeks (roughly 4 months through 2½ years), staleness from 0–25 weeks for horizon 0, and staleness 0 for other horizons, for a total of 185,236 models11 comprising 3,808 model sequences.

Experiment 2 broadens focus to all 19 disease/country contexts and narrows analysis to research questions RQ2–RQ4. We built models for category distance limits of both 2 and 3 and chose the best result, as detailed below. The other independent variables are the same as Experiment 1. In total, Experiment 2 tested roughly 432,721 models12 and 9,044 model sequences.

Next, we present the key results of these experiments. All output is in the supplement, but we report only specific analyses.

RESULTS

Our hope for this work was to uncover a widely applicable statistical disease forecasting model, which would complement traditional surveillance with its real-time nature and small number of parameters.

This section presents results of testing this notion. In Experiment 1, we explore U.S. influenza in some detail, then broaden our focus in Experiment 2 to all 19 disease/country pairs.

Experiment 1: U.S. influenza

Example predictions

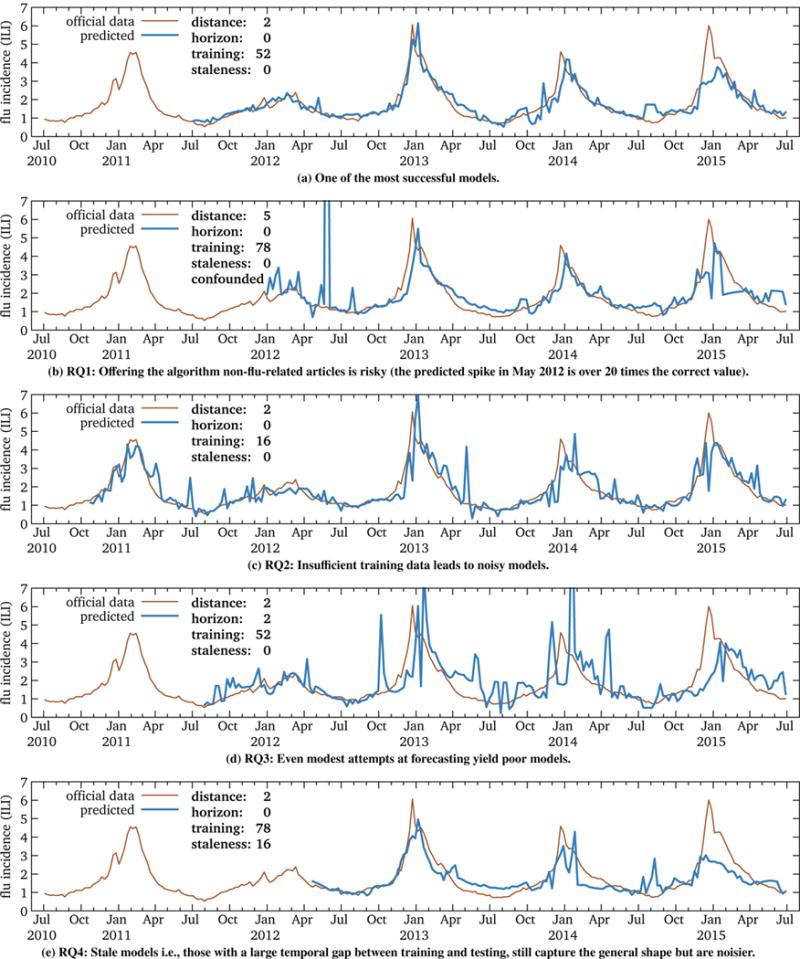

In this experiment, we tested 3,808 U.S. influenza model sequences. Some of these worked well (informally, succeeded), and others worked less well (failed). Figure 2 illustrates some of these predictions, with Figure 2a being one of the most successful. The other subfigures highlight the effects of the four research questions:

RQ1: Figure 2b illustrates the risks of offering non-flu-related articles (in this case, basketball-related) to the fitting algorithm. In addition to increased noise, there is a large spike in the prediction for the week of May 27, 2012. Possible explanations include the controversial 2012 National Basketball Association (NBA) draft lottery on May 30 [22] and the death of Hall-of-Famer Jack Twyman on May 31 [102].

RQ2: Though accuracy is relatively insensitive to training duration, as we detail below, Figure 2c shows an example of a noisy prediction likely due to insufficient training data.

RQ3: Figure 2d illustrates the hazards of forecasting; even this modest 2-week horizon yields a noisy, spiky model.

RQ4: Figure 2e illustrates a model stale by roughly 4 months; that is, these models have a 16-week gap between the epoch (the end of training) and when they were applied. They are still able to capture the general shape of the flu cycle but are not as accurate as fresher models.

Figure 2.

Five of the 3,808 U.S. influenza model sequences we tested, highlighting representative results for each of the four research questions. Each point in the blue predicted series is from an independently trained model. The remainder of this section explores the reasons why some models might succeed and others fail.

The following sub-sections explore these aspects of accuracy in detail, first the value of semantic relatedness (RQ1), then how the models are less sensitive to training duration and staleness (RQ2 and RQ4), and finally the models’ near-total inability to forecast (RQ3).

Semantic relatedness matters (RQ1)

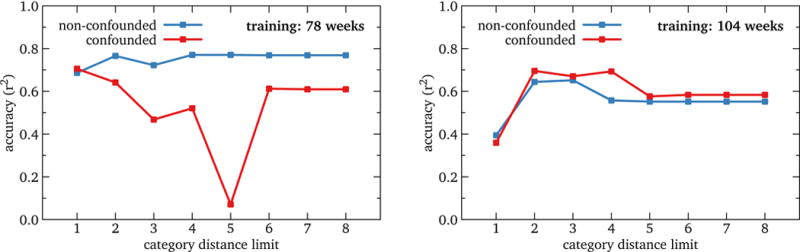

We tested the value of limiting model inputs to articles semantically related to the target context in two ways: by testing the effect of likely-correlated but unrelated articles (basketball) and relatedness limits based on Wikipedia categories. We held forecast horizon and staleness at zero. The results are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

RQ1: Accuracy of U.S. influenza nowcast models by category distance limit, for two representative training durations. The non-confounded model performs consistently better than the confounded model for training durations up to 1½ years (78 weeks) and roughly the same at 2 and 2½ years (104 and 130 weeks). Further, all models’ performance is best or nearly so at a distance limit of 2. This suggests that a semantic article filter such as ours is in fact desirable.

Comparing the control case of a single root article, “Influenza” to the confounded one of adding two additional roots, “Basketball” and “College basketball”, yields two results: confounding the models either makes things worse, sometimes greatly so, (training duration 78 weeks or less) or has little effect (training of 104 weeks or more). This suggests that casting a wide net for input articles is a bad idea: it is unlikely to help, it might hurt a lot, and it can be very costly, perhaps even turning a workstation problem into a supercomputer problem.13

A complementary experiment tested category distance limits of 1 to 8. All training durations showed a roughly similar pattern: distance 1 was clearly sub-optimal, distance 2 had the highest accuracy or nearly so, and distance 3 or more showed a plateau or modest decline. Considered with the results above, this implies that somewhere in the gap between category distance 8 and entirely unrelated articles, a significant decline in accuracy is probable. This suggests that a relatively small limit is most appropriate, as higher does not help, and offering the fitting algorithm more articles is risky, as we showed above.

In short, we show that an input filter based on some notion of relatedness is useful for Wikipedia-based disease prediction, and we offer a filter algorithm that requires minimal parameterization — simply select a root article, which need not be in a language known to the user due to inter-language links.

Training and staleness matter less (RQ2, RQ4)

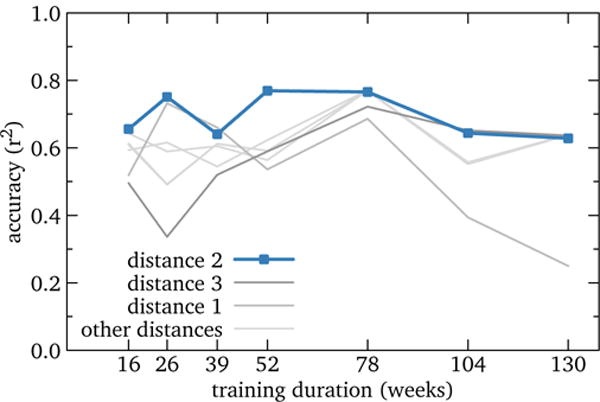

We tested the effect of training duration from 16 to 130 weeks (4 months to 2½ years) with all 8 distance limits and forecast horizon and staleness held at zero, as well as staleness from 0 to 25 weeks (6 months) with three training values, distance at 2, and forecast horizon at zero.

Training durations of 26, 52, and 78 weeks at distance 2 show similar r2 of roughly 0.76, while 39 weeks dips to r2 = 0.64 (Figure 4); we suspect this is due to severely overestimating the peak magnitude in the 2013–2014 season. Other category distances yield a similar pattern, with distance 2 being close to the best at all training durations. We speculate that this general plateau of 6–18 months’ training is because the fit selects similar models, yielding similar results.

Figure 4.

RQ2: Accuracy of U.S. influenza nowcast models by training duration. Performance is relatively insensitive to this parameter, with reasonable results throughout the tested range, and the best value somewhere in the range of 6 to 18 months. This suggests that training duration should be a lower priority than other model parameters.

This suggests that optimizing training duration should have lower priority than other model parameters and that considerations other than pure accuracy may be relevant. For example, influenza is a yearly, seasonal disease; 39 weeks is ¾ cycle, which may be an awkward middle ground that often attempts to combine small fractions of two influenza seasons with summer inactivity. On the other hand, 52 weeks and 78 weeks capture 1 and 1½ cycles respectively, which plausibly is more robust. Another implication is that one shouldn’t simply train on all the data available; conversely, potential models need not be discarded a priori if training data are limited.

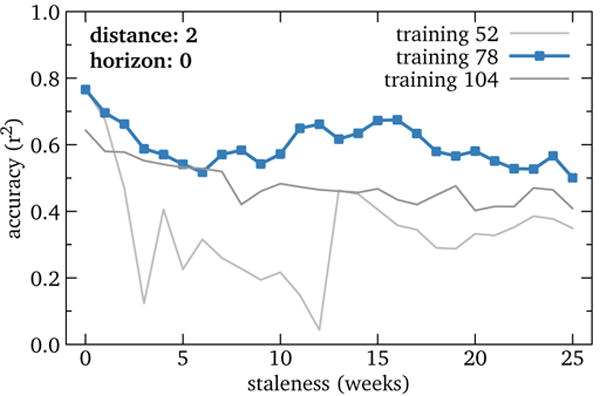

Staleness also showed relative insensitivity (Figure 5). At 78 weeks training, accuracy started at r2 = 0.77 for staleness 0 and gradually declined to roughly 0.6 by 25 weeks. Training of 52 and 104 weeks showed a broadly similar pattern with generally lower r2, except that the former had very poor performance from staleness 3 to 12. This was caused by a huge, erroneous predicted spike in spring 2015, caused in turn by the models for epoch 248 and 249 making severe overestimates. We suspect that these models unluckily chose articles with traffic data quality problems.

Figure 5.

RQ4: Accuracy of U.S. influenza models by model staleness (i.e., temporal gap between training and testing). Performance declines steadily with increasing staleness, though the general trend is slow. These results also differentiate training duration of 78 weeks from others, as it is more robust to staleness. This suggests that using Wikipedia data to fill the gap left by even significantly delayed official data is feasible.

This result is encouraging because staleness is a parameter determined by data availability rather than user-selected. That is, models robust to high staleness might be usable to fill longer delays in official data publication, and our results suggest that Wikipedia data can be used to augment official data delayed much longer than the 1–2 weeks of U.S. ILI.

Forecasting doesn’t work (RQ3)

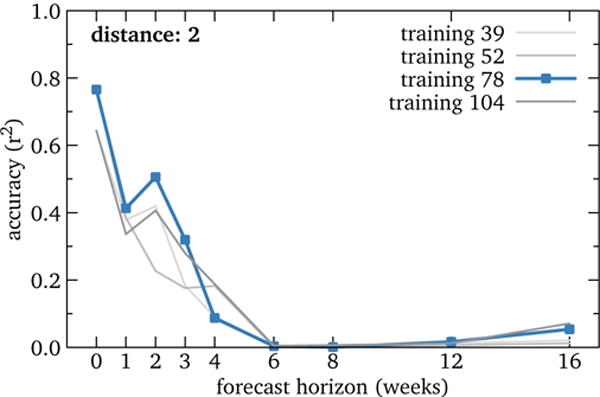

We tested forecasting horizons of 0 to 16 weeks, with four training durations, category distance of 2, and staleness of 0 weeks.

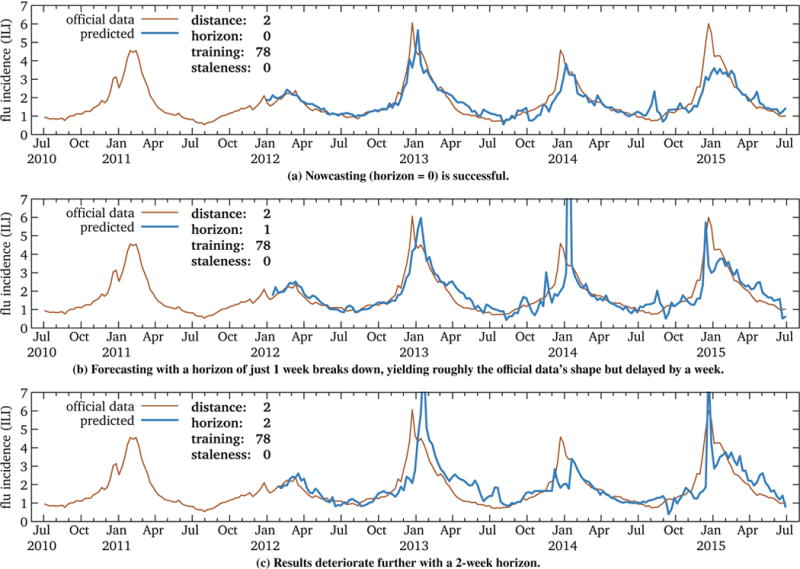

Figure 6 shows model sequence examples for forecasts of 0 (nowcasting), 1, and 2 weeks. These results are not encouraging. While the nowcast performs relatively well (r2 = 0.77), the 1-week and 2-week forecasts perform poorly (r2 = 0.41 and 0.51, respectively). In addition to greater noise, the forecasts show a tendency for spikes (e.g., January 2014 in Figure 6b) and an “echo” effect of the same length as the forecast horizon. We speculate that the latter is due to training data that includes summer periods when phase does not matter; when applied to times near the peak when it does, the model cannot compensate.

Figure 6.

RQ3: Two U.S. influenza models. While nowcasting is effective, even modest levels of forecasting have markedly lower accuracy, due to noise and an “echo” effect. This suggests that forecasting using Wikipedia data requires performance metrics sensitive to phase shift.

Figure 7 quantifies this situation. All four training periods show rapid decline in forecasting accuracy, even with a single-interval horizon of 1 week.

Figure 7.

RQ3: Accuracy of U.S. influenza models by forecast horizon. Performance declines markedly even with a horizon of just one week. This suggests, in contrast to prior work, that forecasting disease using Wikipedia data is risky. (Other category distances display a similar pattern.)

These results contrast with prior work. For example, we reported several situations with high correlations between Wikipedia article traffic and official data under a forecasting off-set [57]. However, this work had no independent test set; i.e., it reported training set correlations, which are very likely to be higher than test set correlations. Similarly, Bardak & Tan [13] reported linear regression models whose performance was best at a 5-day forecast. This work tested a large number of algorithms and parameterizations and used internal cross-validation rather than a test set that strictly followed the training, the latter being a more realistic setting.

In short, it appears that statistical forecasting of disease incidence with summary Wikipedia access logs may be risky; whether this applies to internet data in general is another hypothesis. We return to these broader issues in the discussion section below.

Experiment 2: Compare diseases and locations

Recall that our goal was to obtain comparable disease incidence data in a dense variety of diseases and locations, hoping that this would enable comparisons on those two dimensions for the training, horizon, and staleness research questions (RQ2, RQ3, RQ4). That is, what is the relationship between these parameters and properties of given diseases or locations?

The best r2 score for any parameter configuration in each disease/country context is listed in Table 1 above. These range from r2 = 0.06 for Israel malaria to 0.93 for Germany influenza, with most of these best scores being rather poor. Thus, these generally negative results do not support the analysis we originally envisioned, though we do observe that all contexts with small case numbers perform poorly.

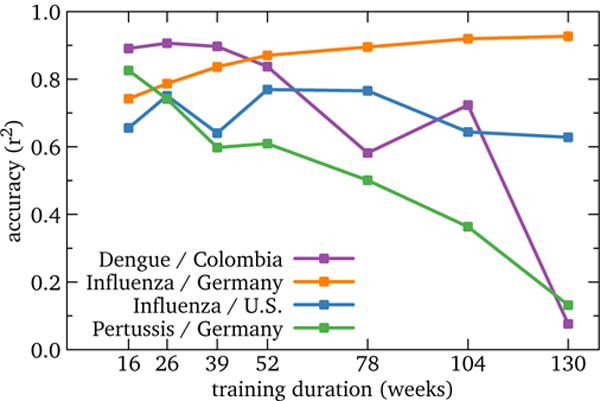

Instead, we analyze the four best-performing contexts (Germany influenza, Colombia dengue, Germany pertussis, and U.S. influenza) as individual case studies; this number is somewhat arbitrary but does appear to capture all the contexts above the accuracy inflection point. For all three questions, results were generally consistent with Experiment 1.

Parameterizing category distance was guided by our count of how many articles fell at which category distances (category_distance.ipynb in the supplement), which suggested using 3, as well as the results of Experiment 1, which suggested 2. We ran the experiment at both distances and report the distance which yielded the best mean r2 across all training durations at horizon zero, staleness zero.

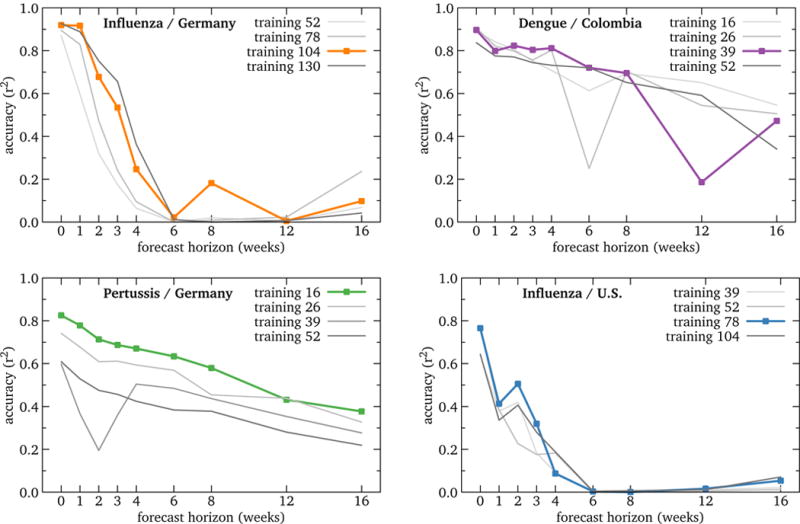

Training and staleness still matter less (RQ2, RQ4)

Figure 8 illustrates accuracy of the four best-performing contexts by training duration, with horizon and staleness both held at zero. In addition to U.S. influenza, both Germany influenza and Colombia dengue both show plateaus of insensitivity to training duration, though these plateaus fall at different parts of the range, roughly 16–52 weeks and 52–130 weeks respectively. We speculate that this is because cultural and disease-related properties both affect how the models work, which in turn influences parameterization.

Figure 8.

RQ2: Accuracy of high-performing global models by training duration. In addition to U.S. influenza, Germany influenza and Colombia dengue also show performance plateaus in training duration; however, the trends and usable ranges vary. On other other hand, Germany pertussis is competitive only at 16 weeks training and drops off rapidly at longer values. This suggests that other parameters may still be of higher priority, and that good performance on a small number of training durations may be cause for concern.

Germany pertussis shows a different trend: highest performance is at 16 weeks, with a steady and large decline as training increases. Examining these models (see supplement) shows that they are autoregressive; essentially, the best fit sets all article coefficients to zero, and the estimate is the mean of the training period. Colombia dengue shows a similar pattern to a lesser degree. With short training periods, this yields higher r2 because it is responsive.

That is, in these cases, Wikipedia has little to add. We speculate that this is caused by some combination of the Wikipedia data lacking sufficient signal, the official data being noisy (variation of 20% or more from week to week is common), and pertussis being a non-seasonal disease (dengue and influenza both are). This result is consistent with Goel et al., which found a similar result for Yahoo search queries and influenza [61].

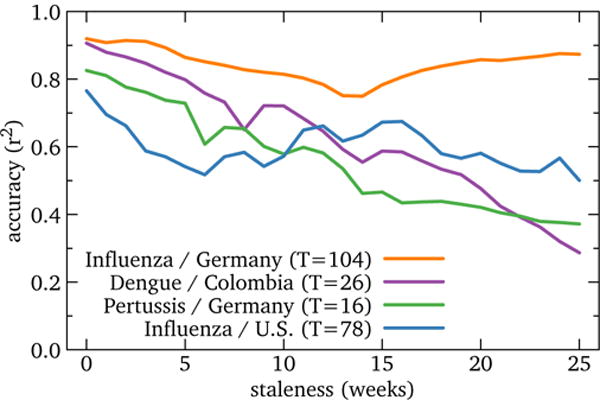

Figure 9 illustrates accuracy by staleness, with horizon held at zero and each context presented at its best training period. Germany influenza is consistent with the U.S.: very modest decline with increasing staleness. Colombia dengue and Germany pertussis show results consistent with the training discussion above: autoregressive models that predict the mean of recent history decline in performance as they reach further into the future.

Figure 9.

RQ4: Accuracy of high-performing global models by staleness. Performance decline is slow for U.S. influenza and Germany and somewhat faster for the other two contexts, though still considerably less than for forecasting. This suggests that using Wikipedia data to fill reporting delays of official data is feasible in some cases.

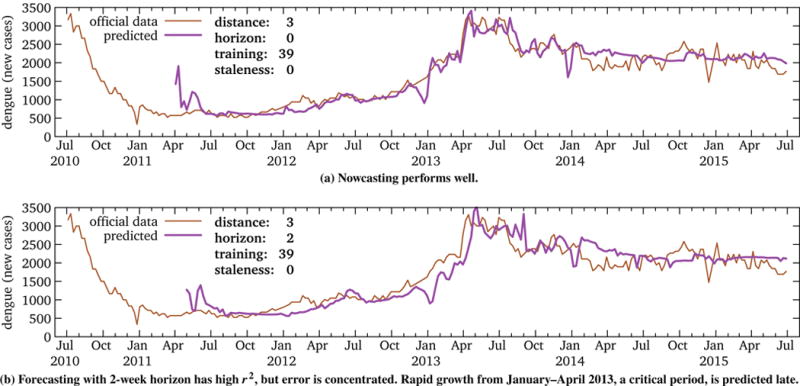

Forecasting still doesn’t work (RQ3)

Figure 10 illustrates the accuracy of best-performing models by forecast horizon, at staleness zero and the best four training durations. Like the U.S., Germany influenza shows immediate and dramatic decline in performance. It appears that there may be some forecasting promise for Colombia dengue, as its performance decline is much slower.

Figure 10.

RQ3: Accuracy of high-performing global models by forecast horizon. While the U.S. and Germany influenza models decline rapidly, Colombia dengue and Germany pertussis declines more slowly. This raises hopes of workable forecasting.

However, Figure 11 illustrates the nowcast and 2-week forecast predictions for Colombia dengue. These show that the high r2 is misleading. While the forecast accurately captures the overall trend, it misses the critical growth period of early 2013. That is, the same echo effect seen in U.S. influenza forecasting results in good predictions when we care least and erroneous ones when we care most. This highlights the pitfalls of non-time-series-aware, yet popular, metrics such as r2. That is, apparently high-performing models may not actually be so, and careful examination of the data as well as appropriate metrics are necessary.

Figure 11.

RQ3: Nowcasting vs. forecasting Colombia dengue. Because forecast error is concentrated in a critical period, the high r2 is misleading. (Other horizons are similar.) This is consistent with our initial conclusion that even short-term forecasting is implausible with Wikipedia data, despite promising results in Figure 10.

DISCUSSION

In this section, we address the implications of our results: what does this study tell us, and what should we do next?

What have we learned?

Our most direct findings are related to the four research questions. First, we found that filtering inputs with semantic relatedness improves predictions and that filters based on minimal human input are effective (RQ1). This is consistent with the adage “garbage in, garbage out” and prior admonishments on the risks of big data [95]. A further valuable implication is that predictions and prediction experiments are tractable on workstations, not just supercomputers.

Second, we found that our linear approach is less insensitive to both the amount (RQ2) and age (RQ4) of training data. This simplifies parameter tuning and implies that in some cases, nowcasting models can be quite robust.

Finally, and contrary to prior work, we found very little forecasting value, even just one time step ahead (RQ3). Why the different outcomes? We identify eight non-exclusive possible explanations:

We made mistakes (i.e., our code has bugs). The opportunity for peer review is one motivation for making our code open-source.

Prior work made mistakes. For example, we suspect that our promising results in [57] are due to lack of a test set.

We targeted the wrong contexts. This work selected mostly for data availability and comparability (e.g., diseases notifiable in many locations) rather than likelihood of success or local prevalence, which may have reduced the power of our experiments.

We used the wrong measure of semantic relatedness. While it appears that our category distance metric offers fairly broad plateaus of good performance, it is quite plausible that different approaches are better. We recommend that future experiments investigate this question, perhaps by combining our framework with one or more open-source relatedness implementations [110,145, e.g.].

-

We used the wrong statistical methods. Though our choice of elastic net linear regression is not particularly novel, and prior work has obtained promising results using similar approaches, it is plausible that other statistical approaches are better.

For example, all linear regression ignores the inherent auto-correlation of time series data and cannot respond to temporal errors such as timing of outbreak peaks. Also consistent with prior work, we weighted uninteresting off-season disease activity the same as critical periods around the peak.

The path forward is to test other statistics. Our framework is general enough to support evaluation of other algorithms, which we plan and encourage others to do.

Using language as a proxy for location is inadequate in this setting. For example, while the language we selected for each country delivers the majority of Wikipedia traffic for that country (Table 1), often-substantial minority traffic is from elsewhere.

Wikipedia or Wikipedia data are inferior to other internet data sources for these purposes. This question could be addressed using qualitative studies to evaluate disease-relevant use patterns and motivations across internet systems, in concert with further quantitative work to systematically compare Wikipedia to other internet data.

Forecasting is a really hard problem. This returns to our core question: when and how is disease measurement using internet data effective?

We find the last item the most intriguing. That is, though the others likely play a role, we argue that it is the crux of the issue. This argument is rooted in a simple distinction: that forecasting the future is fundamentally different, and more difficult, than nowcasting the present.

The internet-based approach to disease measurement is based in the (very probably true) conjecture that individuals leave traces of their health observations online. These traces, however, are snapshots of the present, not the future. This is why, under the right circumstances, nowcasting likely adds value to traditional disease surveillance systems with reporting lag.

On the other hand, it is not obvious why successful nowcasting should extend to forecasting. Why should lay health observations, let alone their highly imperfect internet traces, be predictive of future disease incidence? If one could forecast disease using a statistical map between internet data and later official data, this would suggest that individuals create online traces weeks or months prior to similar observations finding their way into traditional surveillance systems.

In some contexts, this is plausible. Forexample, Paparrizos et al. recently reported that searches for symptoms of pancreatic cancer such as ulcers, constipation, and high blood sugar significantly lead the diagnosis [122], though with a high false positive rate.

In others, this implication is unconvincing. For example, influenza and dengue fever move much faster than pancreatic cancer and do not have distinctive leading symptoms. Also, their seasonal patterns are likely more reliably informed by non-internet data sources such as weather reports. Thus, despite previous work to the contrary, we are unsurprised by our models’ inability to forecast.

We argue that forecasting disease requires capturing the mechanism of its transmission. One approach to this is to deploy the statistical model with an informed sense of which and how leading symptoms are likely to be present, as Paparrizos et al. did; another is to combine internet and/or official data with mathematical transmission models rooted in first principles. This approach uses internet data to constrain mathematically plausible forecast trajectories, much like weather forecasting, and has shown promise on multiple-month horizons [67,147].

More specifically, we speculate that an internet-based disease surveillance system useful in practice might have four components: (1) official data arriving via a tractable number of feeds, large enough for diversity but small enough that each feed can be examined by humans at sufficient frequency and detail, (2) internet data feeds, again arriving in a tractable manner, (3) mathematical models of disease transmission appropriate for the diseases and locations under surveillance, and (4) algorithms to continually re-train and re-weight these three components. These algorithms would use recent performance on validated, epidemiologically appropriate metrics (probably not r2) to make evaluations and adjustments. The system would emit incidence nowcasts and forecasts with quantitative uncertainty, as well as diagnostics to enable meaningful human supervision. For example, if a specific Wikipedia article has been informative in the past but then suddenly becomes non-informative, this change might be alerted.

This brings us to the question of how to follow the present study. We propose focused improvements to the approach we presented as well as a broader look at what might be best for the field in the long term.

Direct extensions of this work

This study raises several focused, immediate questions. Some of these can be answered using the supplement, and others would require new experiments.

First, we did no content analysis of the articles selected by our algorithm, either at the filter stage or by the elastic net for nonzero coefficients. We also have not compared the automatically derived related-article lists with manually curated ones, nor studied why some seasons did better than others. These would provide additional insight into the information flow.

Second, the statistics and algorithms have various opportunities, including non-linear models, regression that includes time series data properties such as auto-correlation, more advanced semantic relatedness metrics, more focused metrics such as the timing and magnitude of peaks, automatic parameter tuning, and ensemble approaches. (These improvements would be straightforward additions to the experiment source code.)

Finally, the Wikipedia data have drawbacks. A technical issue is that article traffic is noisy; for example, we observed some articles where one hour had many orders of magnitude more hits than the preceding and following hours. Characterizing and mitigating the noise problems may help.

A more important concern is that language is a questionable proxy for location and unlikely to be viable at the sub-national level. We see two solutions to this problem. First, the Wikimedia Foundation and Wikipedia community could make available geo-located traffic data; privacy-preserving methods for doing so are quite plausible [134]. Second, the Wikipedia-based semantic distance measure could be combined with a different data source for quantifying health observations.

One possibility is the Google Health Trends API [154], which makes available geo-located traffic counts for both search queries and conceptual “entities” [150] to approved researchers. One could use Wikipedia to specify a set of time series and Google to obtain them. A disadvantage is that these Google data are not available to the public, as Wikipedia traffic is. However, understanding the value-add (if any) would support a cost-benefit analysis of this issue.

Laying a better foundation

We opened the paper by asking “when and how does it work”, hoping to find the answers by comparing across diseases and countries. We did not turn up enough positive results to do this comparison, which caused us to reconsider the approach in general.

This question has three pieces — when, how, and work — none of which have been adequately answered, by us or (to our knowledge) anyone else. To explain this, we invoke the three pillars of science: theory, experiment, and simulation [65]. The field of internet-based disease measurement rests on just experiment, and further, the experiments in question (including ours) are observational, not controlled.

That is, a study proposing a new method or context for such disease measurement must not only show convincingly that it does work but also when and how; otherwise, how can we avoid the risky potential attractor of unrelated yet correlated features? How do we know whether a positive result is robust or how close a negative one was to success? In this section, we propose a research agenda to bring together all three pieces, which may build a new foundation for the field and make it reliable enough for the life-and-death decisions of health policy and practice.

When

Under what circumstances can an approach be expected to work, i.e., what are the relevant parameters, what is their relationship to success, and what are their values in a given setting? Recall the core conjecture of the field: that individuals’ observations of disease yield online traces that can be transformed into actionable knowledge. This conjecture’s truth is clearly non-uniform across all settings: parameters such as disease, location, temporal granularity, number of cases, internet penetration, culture-driven behavior, various biases, exogenous causes of traffic, internet systems(s) under study, and algorithm choice all play a role. The relevant parameters are poorly known, as the sensitivity of a given approach to their values.

How

This requires a theoretical argument that a given approach, including all its pieces, can be trusted to work, which in turn requires understanding, not simply a high r2. Without this, one has little reason to believe or disbelieve a given result.

A related issue is correlation vs. informativeness. Finding correlated signals is not the same as finding informative signals; recall that in the U.S., basketball is correlated with influenza. Decent theory will provide a basis to argue that a given signal is in fact informative (or not).

Work

One must quantify the value added over traditional surveillance alone; simply matching official data well does not do this. We need evaluation metrics that are relevant to downstream uses of the model and provide contrast to plausible alternatives.

For example, very simple models such as autoregression are often competitive on metrics like r2, as demonstrated above and by others [61]. However, constraining mechanistic models with internet-based ones seems most useful with estimates of inflection points, rather than incidence. Knowing outbreak peak timing even a week or two sooner can provide much value, and inflection points such as the peak are when simple models might break down. That said, inflection points must be accurate, and the current internet-based approaches are noisy.

The bottom line is: We argue that this field needs (1) mathematical theory describing the flow of disease-related information from human observations through internet systems and algorithms to actionable knowledge and (2) controlled experiments, which are not possible in the real world but can be performed using simulated outbreaks and simulated internet activity.

In short, we claim that the right question is not “what happens when we try X” but rather “what are the relevant fundamental characteristics of the situation, and how does X relate to them”. This cannot be answered by observation alone.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank our anonymous reviewers for key guidance and the Wikipedia community whose activity we studied. Emiliano Heyns’ Better Bib(La)TeX for Zotero plug-in14 was invaluable, as was his friendly, knowledgeable, and speedy technical support. Plot colors from ColorBrewer15 by Cynthia A. Brewer, Pennsylvania State University. This work is supported by NIH/NIGMS/MIDAS, grant U01-GM097658-01, and DTRA/JSTO, grants CB10092 and DTRA10027.

Footnotes

These data streams do have known inaccuracies and biases [47] but are the best available. For this reason, we refer to them as official data rather than ground truth.

In fact, there is evidence that the volume of internet-based health-seeking behavior dwarfs traditional avenues [137].

Case definitions for the same disease vary somewhat between countries; interested readers should follow the references for details.

This request count differs from the true number of human views due to automated requests, proxies, pre-fetching, people not reading the article they loaded, and other factors. However, this commonly used proxy for human views is the best available.

Vocabulary used in the experiment source code differs somewhat.

That is, elastic net is roughly the weighted sum of lasso regression (minimize non-zero coefficients) and ridge regression (minimize coefficient magnitude).

The number of models takes into account boundary effects (e.g., whether there is enough training data available for a given epoch) as well as models invalid due to missing data.

The total number of models created was 464,080, but we estimate that 23,267 of them were for the confounded U.S. influenza, ignored in Experiment 2, and 8,092 for Colombia influenza, which we excluded because we had official data for only one season.

Our two experiments totaled roughly 12 hours on 8 cores.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

(Equal contribution within each topic.) Led study and writing: Priedhorsky. Principal experiment design: Osthus, Priedhorsky. Experiment design: Del Valle, Deshpande. Experiment programming and execution: Priedhorsky. Data acquisition: Daughton, Fairchild, Generous, Priedhorsky. Content analysis for unreported pilot experiment: Daughton, Moran, Priedhorsky. Principal results analysis: Priedhorsky. Results analysis: Daughton, Osthus. Supplement preparation: Priedhorsky. Wrote the manuscript: Daughton, Moran, Osthus, Priedhorsky. Critical revisions of manuscript: Del Valle, Deshpande, Fairchild, Generous.

VERIFYING THE SUPPLEMENT

The supplement contains Python pickles and other potentially malicious files. Accordingly, inside the archive is a file sha256sums, which contains SHA-256 checksums of every other file. The checksum of sha256sums itself is:

210f310b24bf840960b8ebed34c3d03f

f3f0b11e6592f54be3d4c021cbac135c

References

- 1.Achrekar Harshavardhan, et al. Predicting flu trends using Twitter data. Computer Communications Workshops (INFOCOM Workshops)) 2011 http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/INFCOMW.2011.5928903.

- 2.Achrekar Harshavardhan, et al. Twitter improves seasonal influenza prediction. Health Informatics (HEALTHINF) 2012 http://www.cs.uml.edu/~bliu/pub/healthinf_2012.pdf.

- 3.Ahn Byung Gyu, Van Durme Benjamin, Callison-Burch Chris. WikiTopics: What is popular on Wikipedia and why. Workshop on Automatic Summarization for Different Genres, Media, and Languages (WASDGML) 2011 http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2018987.2018992.

- 4.Aitken Murray, Altmann Thomas, Rosen Daniel. Engaging patients through social media. IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics; 2014. (Tech report). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alicino Cristiano, et al. Assessing Ebola-related web search behaviour: Insights and implications from an analytical study of Google Trends-based query volumes. Infectious Diseases of Poverty. 2015;4 doi: 10.1186/s40249-015-0090-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40249-015-0090-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Althoff Tim, et al. Analysis and forecasting of trending topics in online media streams. Multimedia. 2013 http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2502081.2502117.

- 7.Althouse Benjamin M, Yih Yng Ng, Cummings Derek AT. Prediction of dengue incidence using search query surveillance. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2011 Aug.5:8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001258. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0001258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aramaki Eiji, Maskawa Sachiko, Morita Mizuki. Twitter catches the flu: Detecting influenza epidemics using Twitter. Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP) 2011 http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2145432.2145600.

- 9.Araz Ozgur M, Bentley Dan, Muelleman Robert L. Using Google Flu Trends data in forecasting influenza-like-illness related ED visits in Omaha, Nebraska. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2014 Sept.32:9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.05.052. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2014.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aslam Anoshé A, et al. The reliability of tweets as a supplementary method of seasonal influenza surveillance. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2014 Nov.16:11. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3532. http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayers John W, et al. Seasonality in seeking mental health information on Google. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013 May;44:5. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.01.012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bahk Gyung Jin, Kim Yong Soo, Park Myoung Su. Use of internet search queries to enhance surveillance of foodborne illness. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2015 Nov.21:11. doi: 10.3201/eid2111.141834. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2111.141834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bardak Batuhan, Tan Mehmet. Prediction of influenza outbreaks by integrating Wikipedia article access logs and Google Flu Trend data. IEEE Bioinformatics and Bioengineering (BIBE) 2015 http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/BIBE.2015.7367640.

- 14.Bogdziewicz Michał, Szymkowiak Jakub. Oak acorn crop and Google search volume predict Lyme disease risk in temperate Europe. Basic and Applied Ecology. 2016 Jan. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2016.01.002.

- 15.Borchardt Stephanie M, Ritger Kathleen A, Dworkin Mark S. Categorization, prioritization, and surveillance of potential bioterrorism agents. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 2006 Jun;20:2. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2006.02.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.idc.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bravata Dena M, et al. Systematic review: Surveillance systems for early detection of bioterrorism-related diseases. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004 Jun;140:11. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-11-200406010-00013. http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-140-11-200406010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breyer Benjamin N, et al. Use of Google Insights for Search to track seasonal and geographic kidney stone incidence in the United States. Urology. 2011 Aug.78:2. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.01.010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brigo Francesco, Erro Roberto. Why do people Google movement disorders? An infodemiological study of information seeking behaviors. Neurological Sciences. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1007/s10072-016-2501-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10072-016-2501-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Broniatowski David Andre, et al. Using social media to perform local influenza surveillance in an inner-city hospital: A retrospective observational study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance. 2015;1:1. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.4472. http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/publichealth.4472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broniatowski David A, Paul Michael J, Dredze Mark. National and local influenza surveillance through Twitter: An analysis of the 2012–2013 influenza epidemic. PLOS ONE. 2013 Dec.8:12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083672. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0083672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brooks Logan C, et al. Flexible modeling of epidemics with an empirical bayes framework. PLOS Computational Biology. 2015 Aug.11:8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004382. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brooks Matt. Was the NBA draft lottery rigged for the New Orleans Hornets to win? Washington Post. 2012 May; https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/early-lead/post/was-the-nba-draft-lottery-rigged-for-the-new-orleans-hornets-to-win/2012/05/31/gJQAmL5V4U_blog.html.

- 23.Burdziej Jan, Gawrysiak Piotr. Using web mining for discovering spatial patterns and hot spots for spatial generalization. Chen Li, et al., editors. Foundations of Intelligent Systems. 2012;(7661) http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-34624-8_21.

- 24.Butler Declan. When Google got flu wrong. Nature. 2013 Feb.494:7436. doi: 10.1038/494155a. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/494155a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carneiro Herman Anthony, Mylonakis Eleftherios. Google Trends: A web-based tool for real-time surveillance of disease outbreaks. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2009 Nov.49:10. doi: 10.1086/630200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/630200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cayce Rachael, Hesterman Kathleen, Bergstresser Paul. Google technology in the surveillance of hand foot mouth disease in Asia. International Journal of Integrative Pediatrics and Environmental Medicine. 2014;1 http://www.ijipem.com/index.php/ijipem/article/view/6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) MMWR morbidity tables. 2015 http://wonder.cdc.gov/mmwr/mmwrmorb.asp.

- 28.Overview of influenza surveillance in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); 2016. (Technical Report). http://www.cdc.gov/flu/pdf/weekly/overview.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cergol Boris, Omladič Matjaž. What can Wikipedia and Google tell us about stock prices under diferent market regimes? Ars Mathematica Contemporanea. 2015 Jun;9:2. http://amc-journal.eu/index.php/amc/article/view/561. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chakraborty Prithwish, et al. Forecasting a moving target: Ensemble models for ILI case count predictions. SIAM Data Mining. 2014 http://epubs.siam.org/doi/abs/10.1137/1.9781611973440.30.

- 31.Chan Emily H, et al. Using web search query data to monitor dengue epidemics: A new model for neglected tropical disease surveillance. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2011 May;5:5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001206. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0001206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chartree Jedsada. Monitoring dengue outbreaks using online data. Ph.D. University of North Texas; 2014. http://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc500167/m2/1/high_res_d/dissertation.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cho Sungjin, et al. Correlation between national influenza surveillance data and Google Trends in South Korea. PLOS ONE. 2013 Dec.8:12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081422. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0081422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chunara Rumi, et al. Online reporting for malaria surveillance using micro-monetary incentives, in urban India 2010–2011. Malaria Journal. 2012 Feb.11:1. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-11-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chunara Rumi, et al. Flu Near You: An online self-reported influenza surveillance system in the USA. Online Journal of Public Health Informatics. 2013 Mar;5:1. http://dx.doi.org/10.5210/ojphi.v5i1.4456. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chunara Rumi, Andrews Jason R, Brownstein John S. Social and news media enable estimation of epidemiological patterns early in the 2010 Haitian cholera outbreak. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2012 Jan.86:1. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0597. http://dx.doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ciglan Marek, Nørvåg Kjetil. WikiPop: Personalized event detection system based on Wikipedia page view statistics. Information and Knowledge Management (CIKM) 2010 http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/1871437.1871769.

- 38.Collier Nigel, et al. BioCaster: Detecting public health rumors with a Web-based text mining system. Bioinformatics. 2008 Dec.24:24. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn534. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btn534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cooper Crystale Purvis, et al. Cancer internet search activity on a major search engine, United States 2001–2003. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2005 Jul;7:3. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.3.e36. http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7.3.e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Culotta Aron. Towards detecting influenza epidemics by analyzing Twitter messages. Workshop on Social Media Analytics (SOMA) 2010 http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/1964858.1964874.