Abstract

Purpose

Racial disparities in the incidence and risk profile of prostate cancer at diagnosis among African-American men are well reported. However, it remains unclear whether African-American race is independently associated with adverse outcomes in men with clinical low risk disease.

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively analyzed the records of 895 men in the SEARCH (Shared Equal Access Regional Cancer Hospital) database in whom clinical low risk prostate cancer was treated with radical prostatectomy. Associations of African-American and Caucasian race with pathological biochemical recurrence outcomes were examined using chi-square, logistic regression, log rank and Cox proportional hazards analyses.

Results

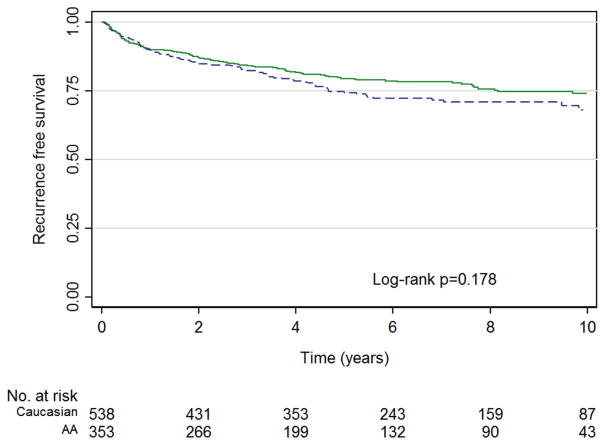

We identified 355 African-American and 540 Caucasian men with low risk tumors in the SEARCH cohort who were followed a median of 6.3 years. Following adjustment for relevant covariates African-American race was not significantly associated with pathological upgrading (OR 1.33, p = 0.12), major upgrading (OR 0.58, p = 0.10), up-staging (OR 1.09, p = 0.73) or positive surgical margins (OR 1.04, p = 0.81). Five-year recurrence-free survival rates were 73.4% in African-American men and 78.4% in Caucasian men (log rank p = 0.18). In a Cox proportional hazards analysis model African-American race was not significantly associated with biochemical recurrence (HR 1.11, p = 0.52).

Conclusions

In a cohort of patients at clinical low risk who were treated with prostatectomy in an equal access health system with a high representation of African-American men we observed no significant differences in the rates of pathological upgrading, up-staging or biochemical recurrence. These data support continued use of active surveillance in African-American men. Upgrading and up-staging remain concerning possibilities for all men regardless of race.

Keywords: prostatic neoplasms, African Americans, watchful waiting, neoplasm staging, neoplasm grading

The suitability of active surveillance for AA men with otherwise clinically favorable PCa at presentation has been questioned on the presumption of more aggressive disease. This assertion has been difficult to validate, given the marked underrepresentation of AA men in the landmark cohorts that have established the viability of surveillance in the low risk state.1,2 Indeed, AA men bear a comparatively greater PCa burden relative to that of other major American demographic groups, including increased PCa rates, higher proportions of high grade and advanced stage disease at presentation, and a greater risk of cancer specific mortality.3–5 However, it is unclear whether these disparities persist following adjustment for disease characteristics, therapeutic selection, socioeconomic status and access to care because conflicting studies addressing this issue exist.6,7

Most studies that directly addressed outcomes in AA patients during active surveillance indicate higher rates of disease reclassification and treatment compared with Caucasian men, although they are limited by the smaller sample sizes and the relative underrepresentation of AA patients in these cohorts.8–11 In the absence of larger studies the concordance between clinical grade and stage with pathological parameters at radical prostatectomy has been offered as a proxy for evaluating candidacy for active surveillance in men with low risk disease. Several studies with disproportionately low participation rates of AA men relative to the American population have shown contrasting results. Single institution and cross-sectional data from NCDB (National Cancer Data Base) have shown higher rates of upgrading and up-staging while others, including a multi-institutional study from CaPSURE™, showed no significant differences by race.12–15

In this context we evaluate rates of pathological upgrading, up-staging and recurrence-free survival among a racially diverse cohort of men at clinically low risk undergoing surgical treatment for PCa in the United States Veterans Affairs system, an equal access health system with a high representation of AA men.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Under institutional review board supervision data on men who underwent radical prostatectomy between 1989 and 2011 at 6 United States Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers, including West Los Angeles, San Diego and Palo Alto, California; Durham and Asheville, North Carolina; and Augusta, Georgia, were combined into the SEARCH database. Data collected in SEARCH included sociodemographic parameters, clinical tumor characteristics, surgical pathology, followup PSA and disease recurrence. Details regarding SEARCH methodology have been reported previously.16,17

The primary study objective was to examine the effect of AA vs Caucasian race in the development of any adverse pathological characteristics in men with clinical low risk PCa treated with prostatectomy. We identified patients at low risk, defined as Gleason pattern 3 + 3 or less on diagnostic biopsy, PSA 10 ng/ml or less and clinical stage T2a or less. Men of other races, including missing or undefined responses, were excluded from analysis since Asian, Latino or Pacific Islander status represented a small proportion of the cohort (46 patients). Clinical and demographic characteristics were compared across AA and Caucasian strata using frequency tables; the Kruskal-Wallis, Wilcoxon and Mann-Whitney rank sum tests; the chi-square test; and the t-test as appropriate. We further described postoperative risk status using the CAPRA-S postoperative score based on pretreatment PSA and pathological characteristics.18

We examined several definitions of adverse pathology findings, including any Gleason upgrade (3 + 4 or greater), major Gleason upgrade (4 + 3 or greater), upstaging (pT3a or greater, or N1) or positive surgical margins. These end points were selected based on an association with adverse longitudinal oncologic outcomes. They are often regarded as surrogates, although intermediate ones, for active surveillance candidacy.

We constructed multivariable logistic regression models to examine the impact of race adjusted for other relevant clinical and pathological characteristics, including age, PSA, clinical stage (T2 vs T1), percent of cores positive for cancer, treatment year, body mass index in kg/m2 and treatment center. Covariates included in the analysis of positive margin status included prostate weight and surgical technique (open retropubic, perineal, laparoscopic or robot-assisted). We tested for interaction terms between covariates that may have modified the response variables in the multivariable logistic regression models. Two-sided p <0.05 was regarded as significant. All statistical analysis was performed using STATA®, version 13.

Subanalyses were done using more restrictive definitions of active surveillance candidacy, including JHU and UCSF criteria.19,20 JHU criteria included Gleason grade 3 + 3 or less, PSA density 0.15 ng/ml/ml or less, clinical stage T1c or less, 2 or fewer cores positive and no single core involvement of cancer 50% or greater.19 UCSF criteria included Gleason 3 +3 or less, clinical stage T2c or less, 33% or fewer cores positive and no single core involvement of cancer 50% or greater.20 PSA density was calculated using pathological specimen weight for the 853 men (95.3%) without available volume calculations at biopsy. This was performed because we previously found a strong correlation between preoperative ultrasound measured volume and pathological prostate weight in SEARCH.21 Core specific data, including the maximum percent of tissue involved with tumor, were lacking for individual treatment centers (as low as 25.3%) and yet were relatively complete for other centers (highest 92.3%). Complete clinical and pathological data allowing for the calculation of strict active surveillance definitions were available on 532 men (59.4%) for JHU criteria and on 544 (60.8%) for UCSF criteria.

Recurrence was defined as a single postoperative PSA value greater than 0.2 ng/ml, 2 values of 0.2 ng/ml each (BCR) or the receipt of any salvage PCa therapy administered for increased PSA. Time to recurrence was compared between the AA and Caucasian groups using Kaplan-Meier plots and the log rank test. We examined the role of AA vs Caucasian race using the Cox proportional hazards method adjusted for significant clinical and pathological characteristics, including age, pathological Gleason score, preoperative PSA, margin status, presence or absence of seminal vesicle invasion, extracapsular extension, treatment year, treatment center and body mass index. Patients who received adjuvant radiation for undetectable postoperative PSA were censored at that time as not having recurrence.

RESULTS

Clinical and Demographic Characteristics

We identified 895 men with clinical low risk tumors who were treated with surgery, including 355 AA (39.7%) and 540 Caucasian men (60.3%) in a cohort of 3,492 patients. Among all patients median PSA was 5.2 ng/ml (IQR 4.2–6.9) and mean age was 61.0 years. Compared with Caucasian men AA men were younger at diagnosis (mean age 59.5 vs 62.0 years, p <0.01) and had significantly higher PSA (median 5.5 vs 5.1 ng/ml, p <0.01) and PSA density (median 0.134 vs 0.126 ng/ml/ml, p = 0.02). A higher proportion of AA than Caucasian men had clinical stage T1c disease at diagnosis (78.3% vs 69.3%, p <0.01). A total of 344 men met strict UCSF active surveillance criteria, as did 204 by JHU criteria, representing 63% and 38% of patients, respectively, with clinical data sufficient for calculation. Table 1 lists complete clinical and demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Characteristics at diagnosis and pathological characteristics of 895 men treated with radical prostatectomy for low clinical risk Gleason 3 + 3 PCa between 1990 and 2011

| Caucasian | African-American | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. pts | 540 | 355 | – | ||

| Mean ± SD age at diagnosis | 62.0 ± 5.8 | 59.5 ± 6.7 | <0.01 | ||

| Median ng/ml PSA at diagnosis (IQR) | 5.1 | (4.0–6.6) | 5.5 | (4.5–7.2) | <0.01 |

| Median ng/ml/gm PSA density (IQR) | 0.126 (0.088–0.177) | 0.134 (0.096–0.192) | 0.02 | ||

| Mean ± SD biopsy cores (SD): | |||||

| No. sampled | 9.1 ± 3.0 | 9.3 ± 3.1 | 0.40 | ||

| No. pos | 2.5 ± 1.8 | 2.5 ± 1.7 | 0.75 | ||

| % Pos | 0.30 ± 0.21 | 0.28 ± 0.19 | 0.28 | ||

| Median ml prostate vol (IQR)* | 33 | (26–44) | 33 | (25–44) | 0.99 |

| No. clinical stage (%): | <0.01 | ||||

| T1c | 374 | (69.3) | 278 | (78.3) | |

| T2a | 166 | (30.7) | 77 | (27.2) | |

| No. treatment yr (%): | 0.03 | ||||

| 1990–1996 | 59 | (10.9) | 38 | (10.7) | |

| 1997–2003 | 248 | (45.9) | 133 | (37.5) | |

| 2004–2011 | 233 | (43.2) | 184 | (51.8) | |

| No. surgical approach (%): | 0.001 | ||||

| Open retropubic | 367 | (69.0) | 275 | (77.5) | |

| Perineal | 143 | (26.9) | 54 | (15.2) | |

| Laparoscopic | 14 | (2.6) | 11 | (3.1) | |

| Robotic | 8 | (1.5) | 13 | (3.7) | |

| Unknown | 8 | (1.5) | 2 | (0.6) | |

| No. pathological Gleason grade (%): | <0.01 | ||||

| 3 + 3 | 334 | (61.9) | 189 | (53.2) | |

| 3 + 4 | 142 | (26.3) | 140 | (39.4) | |

| 4 + 3 | 39 | (7.2) | 14 | (3.9) | |

| 4 + 4 or Greater | 25 | (4.6) | 12 | (3.4) | |

| No. pathological T stage (%): | 0.46 | ||||

| T2 | 455 | (87.0) | 306 | (86.9) | |

| T3 | 58 | (11.1) | 35 | (9.9) | |

| T4 | 10 | (1.9) | 11 | (3.1) | |

| No. lymph node status (%): | 0.55 | ||||

| pN1 | 1 | (0.2) | 0 | ||

| pN0 | 217 | (40.5) | 153 | (43.1) | |

| pNx | 317 | (59.3) | 202 | (56.9) | |

| No. pos surgical margin (%): | 179 | (35.2) | 144 | (41.5) | 0.06 |

| No. extracapsular extension (%): | 50 | (9.3) | 33 | (9.3) | 0.99 |

| No. seminal vesicle invasion (%): | 12 | (2.2) | 12 | (3.4) | 0.29 |

| No. Gleason upgrade (%): | |||||

| Any 3 + 4 or greater | 206 | (38.2) | 166 | (46.8) | 0.01 |

| Major 4 + 3 or greater | 64 | (11.9) | 26 | (7.3) | 0.03 |

| Mean ± SD pathological wt (gm) | 41.9 ± 18.1 | 42.8 ± 19.8 | 0.49 | ||

| No. pathological up-stage (%):† | 68 | (13.0) | 46 | (13.1) | 0.98 |

| No. any upgrade or up-stage (%): | 233 | (43.2) | 182 | (51.3) | 0.02 |

| No. CAPRA-S group (%): | 0.16 | ||||

| 0–2 | 387 | (71.7) | 234 | (65.9) | |

| 3–5 | 142 | (26.3) | 110 | (31.0) | |

| 6–10 | 11 | (2.0) | 11 | (3.1) | |

Diagnostic transrectal ultrasound volume unavailable in 479 patients.

pT3 or greater, or N1.

Pathological Findings

At radical prostatectomy Gleason score was concordant with biopsy (3 + 3) in 523 men (58.4%). A higher proportion of AA men experienced any upgrade from diagnostic biopsy (3 + 4 or greater) compared with Caucasian men (46.8% vs 38.2%, p = 0.01). However, unadjusted rates of major upgrading (4 + 3 or greater) were significantly higher in Caucasian than in AA patients (11.9% vs 7.3%, p = 0.03). Positive surgical margins were found in 41.5% of AA men compared with 35.2% of Caucasians (p = 0.06). No significant differences were observed between AA and Caucasian men in pathological up-staging, seminal vesicle invasion or extracapsular extension. One Caucasian patient had positive lymph nodes at surgery while node status was not assessed in 58% of patients. Postoperative CAPRA-S scores were similar in the 2 groups. Table 1 lists complete pathological outcomes.

On multivariable logistic regression analysis adjusted for clinical and pathological characteristics AA race was not significantly associated with pathological upgrading to 3 + 4 or greater (OR 1.33 95% CI 0.92–1.93, p = 0.12), major upgrading (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.31–1.10, p = 0.10), up-staging (OR 1.09, 95% CI 0.65–1.83, p = 0.73) or positive surgical margins (OR 1.04, 95% CI 0.73–1.49, p = 0.81, supplementary table 1, http://jurology.com/). On separate subset analyses of men who met JHU and UCSF strict active surveillance criteria (p = 0.50 and 0.75, respectively) AA status was not significantly associated with pathological upgrading to 3 + 4 or greater. Moreover, there was no significant association between AA or Caucasian race with major pathological upgrading, up-staging or surgical margin status in these subsets (supplementary table 2, http://jurology.com/).

Recurrence-Free Survival

Among patients who did not experience BCR median followup was 6.3 years (IQR 3.8–8.9). Median followup was shorter in AA than in Caucasian patients (5.7 years, IQR 3.2–8.6 vs 6.6, IQR 4.2–9.2, p = 0.03). A total of 209 men experienced BCR, including 89 AA (22.3%) and 120 Caucasian men (25.2%) (p = 0.32). Five-year freedom from BCR rates were 73.4% and 78.4% for AA and Caucasian men, respectively (log rank p = 0.18, see figure). After adjustment for clinical and pathological characteristics AA race was not significantly associated with time to BCR (HR 1.11, 95% CI 0.81–1.50, p = 0.52, table 2). On multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis there was no association between race and time to BCR upon further restricting analysis to men meeting JHU (p = 0.95) or UCSF (p = 0.56) active surveillance criteria.

Figure 1.

Biochemical recurrence-free survival by AA (blue curve) vs Caucasian (green curve) race

Table 2.

Cox proportional hazards analysis modeling recurrence-free survival in 895 men treated with radical prostatectomy

| Independent Variable | HR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Race (AA vs Caucasian) | 1.105 (0.814–1.501) | 0.521 |

| Age at diagnosis | 0.998 (0.975–1.021) | 0.865 |

| Pathological Gleason score:* | ||

| 3 + 3 (referent) | 1.357 (0.975–1.889) | 0.071 |

| 3 + 4 | 1.459 (0.787–2.704) | 0.230 |

| 4 + 3 | 2.022 (1.071–3.817) | 0.030 |

| PSA at diagnosis | 1.107 (1.029–1.191) | 0.006 |

| Margin status | 2.134 (1.563–2.913) | 0.000 |

| Seminal vesicle invasion | 1.854 (0.900–3.821) | 0.094 |

| Extracapsular extension | 1.096 (0.702–1.711) | 0.687 |

| Treatment yr | 0.980 (0.945–1.017) | 0.286 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2/5 units) | 1.107 (0.953–1.286) | 0.183 |

No patient had pathological Gleason score 4 + 4 or greater.

DISCUSSION

Whether AA men are at greater risk for adverse outcomes during surveillance for clinically low risk PCa is a matter of significant clinical importance. Because AA men endure a higher burden of PCa in relation to Caucasian men, exclusion from active surveillance would expose a considerable proportion of AA men to treatment and, therefore, it warrants closer scrutiny.6 Currently, discordance exists in the literature with some studies indicating higher risks of pathological up-staging and biochemical recurrence in AA men while others show equivalence when adjusting for relevant factors. However, the unifying limitations in these studies are the disproportionately low participation rates of AA patients, and the unmeasured influences of socioeconomic status and access to care.1,12,14

We evaluated the role of AA vs Caucasian race in a large, diverse cohort of men at clinically low risk receiving treatment at 6 United States Veterans Affairs medical centers. We observed no significant association between AA race and pathological upgrading, up-staging, positive margin status or biochemical recurrence after treatment.

Prior studies of the incidence of pathological upgrading and up-staging in AA men have yielded conflicting results. Sundi et al described 1,801 men at very low risk who were treated with prostatectomy at The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.12 Of these men 256 (14%) who were AA were significantly more likely to experience adverse pathological findings even given highly restrictive criteria for low risk disease.12 Higher rates of upgrading and up-staging in The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions cohort have been attributed in part to a higher incidence of anterior tumors in AA men, which resulted in clinical under staging.22 In contrast, Jalloh et al evaluated similar end points in 273 AA (6.5%) and 3,771 Caucasian men (89.1%) derived from UCSF and the CaPSURE registry, a national disease registry drawing from 43 sites, in which no difference was observed in the rate of upgrading or up-staging by race.14

We noted higher unadjusted rates of positive surgical margins in AA men. However, on multivariable analysis incorporating relevant clinical and pathological features at diagnosis this relationship was not statistically significant. These findings are supportive of those reported by Witte et al in 260 AA men compared with 347 Caucasian men.23 In that study race was not an independent predictor of margin status. Other groups, including Jalloh et al,14 detected persistent differences in margin status associated with race even when adjusted for relevant clinical factors, including prostate size, year of treatment, nerve sparing technique and surgical approach. Notably, high rates of positive margins were observed in AA and Caucasian patients relative to that in many published open and robotic series. Although consistent with prior analyses in the SEARCH database, these findings highlight technical and patient related factors that may contribute to higher rates of positive margins.24,25 Variations in pelvic anatomy between AA and Caucasian men, including steeper symphysis pubis angles and more narrow mid pelvic areas in AA men, have been described that may impart a greater technical challenge, particularly during apical dissection.26,27

Prior studies of disparities in recurrence-free survival outcomes among risk stratified AA men have demonstrated inconsistent results with several studies indicating an independent association of race and recurrence.1,28 In this updated study restricted to men at low risk we did not detect significant differences in the rate of clinical recurrence among AA men. Our findings are in agreement with an earlier SEARCH analysis of pathological outcomes in men who were candidates for active surveillance, including 140 AA patients, comprising 42.5% of the cohort.29 In that series AA race was not significantly associated with time to BCR at a median 43-month followup.

The current results in a restricted cohort of men at clinically low risk are also consistent with prior publications from the broader SEARCH experience that have shown a small but consistently increased risk of recurrence in AA men on multivariable analysis that did reach thresholds for statistical significance.17,30 Greater statistical power may be required to definitively address this question in a longitudinally followed surgical cohort. However, if present, such an effect would likely be small.

There are limitations to this analysis that require discussion. Improvements in biopsy with routine use of extended sextant sampling may not be well reflected in participants in earlier study years. This factor may exaggerate a discordance between biopsy and prostatectomy. To account for this we adjusted for year of surgery in our analyses. In addition, we observed an almost 1-year difference in followup between AA and Caucasian participants, which introduces the possibility of followup bias in our analysis of recurrence-free survival. To address this we used time to event analysis, which accounts for differential followup. In addition, pathological specimens were not reviewed centrally, a limitation that may affect the relationship between biopsy and surgical pathological assignment.

Lastly, a subset of SEARCH participants lacked complete clinical and demographic information, particularly for early study year participants. Such limitations also impacted the description of biopsy characteristics, including the percent of cores involved with tumor and the greatest single core tumor volume at treatment sites. These variables prevented the description of JHU or UCSF strict criteria in approximately 40% of the study population.

We studied the role of AA vs Caucasian race on immediate pathological and distant biochemical outcomes in a cohort of men at clinically low risk who were treated with prostatectomy. AA men were diagnosed at younger ages and with higher PSA. However, when controlling for relevant disease characteristics, AA race was not independently associated with pathological upgrading, up-staging, positive surgical margins or clinical recurrence. These findings may directly impact the treatment of AA men who have newly diagnosed PCa with low risk features by demonstrating parity in surgical outcomes, which may offer a valuable surrogate inclusion criterion for active surveillance candidacy.

Ultimately, greater racial diversity in a longitudinal surveillance cohort is required to explicitly study outcomes with time in AA patients with favorable disease. However, our results support the validity of clinical risk stratification in AA men with localized PCa.

CONCLUSIONS

In a diverse, multicenter, multiethnic cohort of men at clinically low risk in an equal access medical system African-American race was not associated with pathological upgrading, up-staging, positive surgical margins or clinical recurrence. Active surveillance in African-American men with clinically favorable risk prostate cancer should not be withheld based on higher risks of adverse pathological features at prostatectomy.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, NIH (National Institutes of Health) Grant R01CA100938 (WJA), NIH Specialized Programs of Research Excellence Grant P50 CA92131-01A1 (WJA), Georgia Cancer Coalition (MKT), NIH Grant K24 CA160653 (SJF) and United States Department of Defense Grant W81XWH-13-2-0074 (MRC and PRC).

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AA

African-American

- BCR

biochemical recurrence

- CAPRA-S

Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment

- JHU

Johns Hopkins University

- PCa

prostate cancer

- PSA

prostate specific antigen

- UCSF

University of California-San Francisco

Footnotes

No direct or indirect commercial incentive associated with publishing this article.

The corresponding author certifies that, when applicable, a statement(s) has been included in the manuscript documenting institutional review board, ethics committee or ethical review board study approval; principles of Helsinki Declaration were followed in lieu of formal ethics committee approval; institutional animal care and use committee approval; all human subjects provided written informed consent with guarantees of confidentiality; IRB approved protocol number; animal approved project number.

References

- 1.Faisal FA, Sundi D, Cooper JL, et al. Racial disparities in oncologic outcomes after radical prostatectomy: long-term follow-up. Urology. 2014;84:1434. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klotz L, Vesprini D, Sethukavalan P, et al. Long-term follow-up of a large active surveillance cohort of patients with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:272. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsivian M, Banez LL, Keto CJ, et al. African-American men with low grade prostate cancer have higher tumor burdens: results from the Duke Prostate Center. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2013;16:91. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ritch CR, Morrison BF, Hruby G, et al. Pathological outcome and biochemical recurrence-free survival after radical prostatectomy in African-American, Afro-Caribbean (Jamaican) and Caucasian-American men: an international comparison. BJU Int. 2013;111:E186. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu KC, Tarone RE, Freeman HP. Trends in prostate cancer mortality among black men and white men in the United States. Cancer. 2003;97:1507. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du XL, Fang S, Coker AL, et al. Racial disparity and socioeconomic status in association with survival in older men with local/regional stage prostate carcinoma: findings from a large community-based cohort. Cancer. 2006;106:1276. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaines AR, Turner EL, Moorman PG, et al. The association between race and prostate cancer risk on initial biopsy in an equal access, multiethnic cohort. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:1029. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0402-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iremashvili V, Soloway MS, Rosenberg DL, et al. Clinical and demographic characteristics associated with prostate cancer progression in patients on active surveillance. J Urol. 2012;187:1594. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.12.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abern MR, Bassett MR, Tsivian M, et al. Race is associated with discontinuation of active surveillance of low-risk prostate cancer: results from the Duke Prostate Center. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2013;16:85. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2012.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Odom BD, Mir MC, Hughes S, et al. Active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer in African American men: a multi-institutional experience. Urology. 2014;83:364. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sundi D, Faisal FA, Trock BJ, et al. Reclassification rates are higher among African American men than Caucasians on active surveillance. Urology. 2015;85:155. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sundi D, Ross AE, Humphreys EB, et al. African American men with very low-risk prostate cancer exhibit adverse oncologic outcomes after radical prostatectomy: should active surveillance still be an option for them? J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2991. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.0302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ha YS, Salmasi A, Karellas M, et al. Increased incidence of pathologically nonorgan confined prostate cancer in African-American men eligible for active surveillance. Urology. 2013;81:831. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.12.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jalloh M, Myers F, Cowan JE, et al. Racial variation in prostate cancer upgrading and upstaging among men with low-risk clinical characteristics. Eur Urol. 2015;67:451. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiner AB, Patel SG, Eggener SE. Pathologic outcomes for low-risk prostate cancer after delayed radical prostatectomy in the United States. Urol Oncol. 2015;33:164, e11. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moreira DM, Nickel JC, Andriole GL, et al. Greater extent of prostate inflammation in negative biopsies is associated with lower risk of prostate cancer on repeat biopsy: results from the REDUCE study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2016;19:180. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2015.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freedland SJ, Amling CL, Dorey F, et al. Race as an outcome predictor after radical prostatectomy: results from the Shared Equal Access Regional Cancer Hospital (SEARCH) database. Urology. 2002;60:670. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01847-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Punnen S, Freedland SJ, Presti JC, Jr, et al. Multi-institutional validation of the CAPRA-S score to predict disease recurrence and mortality after radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2014;65:1171. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter HB, Kettermann A, Warlick C, et al. Expectant management of prostate cancer with curative intent: an update of the Johns Hopkins experience. J Urol. 2007;178:2359. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dall’Era MA, Konety BR, Cowan JE, et al. Active surveillance for the management of prostate cancer in a contemporary cohort. Cancer. 2008;112:2664. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sajadi KP, Terris MK, Hamilton RJ, et al. Body mass index, prostate weight and transrectal ultrasound prostate volume accuracy. J Urol. 2007;178:990. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sundi D, Kryvenko ON, Carter HB, et al. Pathological examination of radical prostatectomy specimens in men with very low risk disease at biopsy reveals distinct zonal distribution of cancer in black American men. J Urol. 2014;191:60. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Witte MN, Kattan MW, Albani J. Race is not an independent predictor of positive surgical margins after radical prostatectomy. Urology. 1999;54:869. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00273-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jayachandran J, Aronson WJ, Terris MK, et al. Obesity and positive surgical margins by anatomic location after radical prostatectomy: results from the Shared Equal Access Regional Cancer Hospital database. BJU Int. 2008;102:964. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07881.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tewari A, Sooriakumaran P, Bloch DA, et al. Positive surgical margin and perioperative complication rates of primary surgical treatments for prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing retropubic, laparoscopic, and robotic prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2012;62:1. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Bodman C, Matikainen MP, Yunis LH, et al. Ethnic variation in pelvimetric measures and its impact on positive surgical margins at radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2010;76:1092. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allott EH, Howard LE, Song HJ, et al. Racial differences in adipose tissue distribution and risk of aggressive prostate cancer among men undergoing radiotherapy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:2404. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamoah K, Deville C, Vapiwala N, et al. African American men with low grade prostate cancer have increased disease recurrence after prostatectomy compared with Caucasian men. Urol Oncol. 2015;33:70, e15. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kane CJ, Im R, Amling CL, et al. Outcomes after radical prostatectomy among men who are candidates for active surveillance: results from the SEARCH database. Urology. 2010;76:695. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.12.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamilton RJ, Aronson WJ, Presti JC, Jr, et al. Race, biochemical disease recurrence, and prostate-specific antigen doubling time after radical prostatectomy: results from the SEARCH database. Cancer. 2007;110:2202. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]