Abstract

Time orientation is an unconscious yet fundamental cognitive process that provides a framework for organizing personal experiences in temporal categories of past, present and future, reflecting the relative emphasis given to these categories. Culture lies central to individuals’ time orientation, leading to cultural variations in time orientation. For example, people from future-oriented cultures tend to emphasize the future and store information relevant for the future more than those from present- or past-oriented cultures. For survey questions that ask respondents to report expected probabilities of future events, this may translate into culture-specific question difficulties, manifested through systematically varying “I don’t know” item nonresponse rates. This study drew on the time orientation theory and examined culture-specific nonresponse patterns on subjective probability questions using methodologically comparable population-based surveys from multiple countries. The results supported our hypothesis. Item nonresponse rates on these questions varied significantly in the way that future-orientation at the group as well as individual level was associated with lower nonresponse rates. This pattern did not apply to non-probability questions. Our study also suggested potential nonresponse bias. Examining culture-specific constructs, such as time orientation, as a framework for measurement mechanisms may contribute to improving cross-cultural research.

Keywords: nonresponse, time orientation, subjective probability questions, survey research

Cognitive psychology has shaped the framework for understanding and improving survey measurement through the Cognitive Psychology and Survey Methodology movement (Schwarz, 2007; Sudman, Bradburn, & Schwarz, 1996). One of the elementary constructs of cognition is culture, which provides a systematic framework for individuals to organize personal experiences (Nisbett, Peng, Choi, & Norenzayan, 2001). As culture is knowledge learned and shared among a group of people (Goodenough, 1971; Hong, 2009; Shweder & LeVine, 1984), it requires verbal and nonverbal communications. Time orientation, a type of nonverbal communication which Hall (1959) labelled as “the silent language,” is shaped by culture.

This study attempts to build a bridge between the time orientation theory and subjective probability questions, a question type that has become increasingly popular in survey research, by examining the relationship between time orientation and respondents’ tendency to say, “I don’t know,” to these questions. Given the tight link between time orientation and culture, a good understanding of whether and how time orientation affects response behaviors on these questions will provide important insights for cross-cultural research.

Time Orientation and Culture

Time orientation is theorized as an unconscious yet fundamental cognitive process that people use for organizing personal experiences relevant to certain temporal dimensions in order to assign coherent meaning to those experiences (Kluckhohn & Strodtbneck, 1961). Although many models have advocated time orientation and human behaviors (e.g., Hofstede, 2011; Graham, 1981), this study focuses on the model by González & Zimbardo (1985) that advocates temporal focus given to the categories of future, present and past orientations. Under this model, time is viewed as a continuum ranging from a category of past to present and to future. Time orientation indicates the category to which cognitive attention is given. This does not mean an orientation towards an exclusive temporal category. Rather, it is where the relative emphasis is located on the temporal continuum (Shipp, Edwards, & Lambert, 2009; Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999). Future time orientation, for instance, is conceptualized through a degree to which the anticipated future is integrated into the present situation, often reflected in future planning and perception of future needs and goals. A person can be considered as being future oriented, if more attention is given to the future than the present or the past. Although there is a variation in time orientation across individuals within culture (Hill, Block, & Buggie, 2000; Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999), an individual’s time orientation is believed to be mostly a product of his or her cultural background (Graham, 1981; Levine, 1997), making culture as a unit categorized with future, present, and past time orientations (González & Zimbardo, 1985).

Comprehensive and systematic research examining cultural groups (e.g., countries) on the future, present and past orientation with a methodological rigor is scarce as echoed by Sircova and colleagues (2014). This may well be a reflection of the fact that “no (cultural) beliefs are more ingrained and subsequently hidden than those about time (p. xv, Levine, 1997).” One such study examined 62 countries using data from the Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE) Research Project on various cultural dimensions, including the degree to which future orientation is practiced in a country (see Tables 13.5 and 13.12b in Ashkanasy et al., 2004). GLOBE findings show that Western countries are ranked high on the spectrum of how much future orientation is practiced in a county and Arab, Latin European, Latin American and Eastern European countries are towards a lower end, with Asian countries spread across the spectrum. This corresponds to other studies (e.g., Hall, 1959; 1976; Ko & Gentry, 1991; Rojas-Méndez & Davies, 2005). Further, the GLOBE study suggests that, within Western Europe, countries in Northern Europe that speak Germanic languages (e.g., the Netherlands, Austria) are more future oriented than those in the Mediterranean region or speaking Romance languages (e.g., Greece, Italy).

The GLOBE Project also provides an interesting point in their presentation of Switzerland by examining time orientation by language: French speakers score lower on future orientation than the rest, who are mostly German speakers. This suggests time orientation varies by language. This is not surprising given the nexus of language and culture (Fong, 2012; Risager, 2006; Silverstein, 2004). Even though not culture per se, language is an important element of culture, related to basic cognition (Bowerman & Levinson, 2001; Majid, Bowerman, Kita, Haun, & Levinson, 2004; Vygotsky, 1962; Whorf, 1956) and further to time orientation (Graham, 1981; Usunier & Valette-Florence, 2007). In fact, the combination of language and time orientation has been shown to affect individuals’ behaviors (e.g., Chen, 2013).

Differential time orientation by race and ethnicity is also reported for multi-racial or multi-ethnic countries. For example, Anglos in the U.S. are associated with higher future orientation than Blacks and Hispanics (Brown & Segal, 1996; Graham, 1981; Marín & Marín 1991) and Asians being more future oriented than Blacks (Steinberg et al., 2009). In New Zealand, students of European descendants are shown to be more future oriented than Maori students (Bray, 1970).

When merging the literature on time orientation, groups associated with nationality, race, ethnicity and language emerge as contributors of a variation in time orientation, all of which are regarded as agents of culture (Hong, 2009). Hence, this study uses these characters as a working version of “culture”.

Future Time Orientation and Item Nonresponse on Subjective Probability Questions

Survey questions using subjective probability have gained popularity increasingly (Hurd, 2009). These questions ask respondents about perceived chances of certain events happening in the future on probabilistic terms using a response scale of 0% to 100% and have been applied to financial outlook (e.g., Dominitz, 1998; Hurd, Van Rooij, & Winter, 2011), health-related expectations (e.g., Hurd & McGarry, 2002) and voting intention (e.g. Delavande & Manski, 2010; Gutsche, Kapteyn, Meijer, & Weerman, 2014). Answers to these questions were shown to predict actual future outcomes (e.g. Delavande & Manski, 2010; Hurd & McGarry, 2002).

Although popular, subjective probability questions are likely to be more difficult than other question types, because 1) respondents may not have enough information in their memories for reasonably predicting future events (e.g., losing a job in 5 years) and 2) respondents may feel uncertain about how to translate this lacking information into an answer that maps onto the solicited probabilistic response scale. This difficulty may well prompt respondents to rely on certain response strategies, such as providing answers heaping at multiples of 10 or 25 or item nonresponse by saying, “I don’t know” (e.g. Bruine de Bruin, Fischbeck, Stiber, & Fischhoff, 2002; Lee & Smith, 2016).

The connection between time orientation and culture examined above has important implications for subjective probability questions in cross-cultural research. Although not explicit, subjective probability questions assume that respondents have information of reasonable quantity and quality for predicting own future. The time orientation theory, on the other hand, suggests that the quantity and quality of information relevant for such predictions vary by time orientation (Bergadaa, 1990). Future-oriented individuals or cultural groups are more focused on future planning than past- or present-oriented individuals or groups and, hence, have more and better information for future prediction, including answering subjective probability questions. This implies an alignment of time orientation for future-oriented individuals or groups with subjective probability questions but a misalignment for the remainders. This is not surprising in that, as pointed out by Graham (1981), future time orientation held by Anglo Americans is the prevailing assumption in social sciences, because the majority of research has been carried out by Anglo Americans or those trained in the Anglo American culture.

These considerations lead to hypotheses that subjective probability questions are more difficult among respondents from present- or past-oriented cultures than those from future-oriented cultures, resulting in differential rates of “I don’t know” item nonresponse, a reflection question difficulty (Tourangeau, Rips, & Rasinski, 2000) and that this differential item nonresponse is observed at the cultural group level as well as the individual level. Item nonresponse has long been a concern as it directly equates to lowered statistical power and, more importantly, is a source of bias (Brick & Kalton, 1996; Ferber, 1966; Little & Rubin, 2002). This study tests these hypotheses by analyzing secondary data from population-based surveys from multiple countries, covering a wide range of cultural groups, supplemented with country-level future orientation scores from a published study.

Method

Databases

This study is based on the analysis of secondary data. The main data come from the 2006 Health and Retirement Study (HRS) for the U.S., Wave 1 of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) for the U.K., Wave 1 of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE; Börsch-Supan & Jürges, 2005, Börsch-Supan et al., 2005; 2013) for Austria, Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, France, Spain, Italy, Greece, and Israel, and the 2011 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). These are sister surveys targeting elderly adults and sharing methodological similarities (e.g., longitudinal surveys using area probability samples administered in-person) as well as content similarities (e.g., health and labor participation near and through the retirement stage).

These surveys include a set of subjective probability questions. Generally, the subjective probability question section starts with an introduction such as, “I have some questions about how likely you think various events might be. When I ask a question I’d like for you to give me a number from 0 to 100. For example, ‘90’ would mean a 90 percent chance. You can say any number from 0 to 100.” The introduction is followed by a practice question, such as, “What do you think the chances are it will be rainy tomorrow?”, before asking substantive questions. Structural skip patterns are applied to many subjective probability questions (e.g., chances of retiring asked only for those who are not retired).

The only subjective probability question asked across all four surveys is about life expectancy. There is little variation in the exact wording for this question across HRS, ELSA and SHARE: “What are the chances that you will live to be age [75/80/85/90/95/100/105/110/120] or more?” except that HRS excludes respondents aged 90 years old or older. The target age in the bracket is determined based on respondents’ current age. The CHARLS version is different from the rest as the question uses a 5-point response scale and asks, “Suppose there are 5 steps, where the lowest step represents the smallest chance and the highest step represents the highest chance, on what step do you think is your chance in reaching the age of [75/80/85/90/95/100/105/110/115]?”

Across HRS, ELSA and SHARE, two additional subjective probability questions are asked: chances of receiving an inheritance in the next ten years and chances of leaving an inheritance. These three surveys also ask a subjective probability question related to future financial situations with different wordings: “What do you think are the chances that your income will keep up with the cost of living for the next five years?” in HRS, “What are the chances that at some point in the future you will not have enough financial resources to meet your needs?” in ELSA, and “What are the chances that five years from now your standard of living will be better than today?” in SHARE.

The supplementary data come from the GLOBE Project introduced earlier. We use the country-level score on how much future orientation is practiced (see Tables 13.5 and 13.12b of Ashkanasy et al., 2004). These scores are available for most countries included in HRS, ELSA, SHARE and CHARLS. Below, we describe variables used in this study.

Dependent Variables

We examine item nonresponse on six questions with little to no comparability issues across data sources. Three of them are subjective probability questions about 1) receiving an inheritance in ten years, 2) life expectancy, and 3) financial situations. The rest are non-probability questions about 4) self-rated health (e.g., “Would you say your health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” in HRS), 5) body weight, and 6) the bank account balance. (Note that the bank account value applies to those with bank accounts.) These questions are selected for the following reasons. First, the future events asked in the subjective probability questions are different and may be subject to varying levels of difficulty. Particularly for older adults these surveys target, questions about inheritance may be easier than those about future financial situations or life expectancy, because there are fewer external factors affecting receiving an inheritance than a standard of living or longevity.

Second, non-probability questions are included to examine whether the hypothesized item nonresponse pattern is specific to subjective probability questions. Also, these non-probability questions on their own are reported with varying levels of item nonresponse: assets and body weights are shown to produce higher item nonresponse rates than, for example, factual demographic questions (e.g., Andreski, McGonagle, & Schoeni, 2007), due to the sensitivity (e.g., not wanting to reveal own assets or weights) and difficulty (e.g., recalling actual bank account balance). On the other hand, the self-rated health question is neither difficult nor sensitive, making a high item nonresponse rate unlikely.

Item nonresponse arises for various reasons and is typically classified into respondents’ saying “I don’t know” or refusing to give an answer (e.g., Colsher & Wallace, 1989). Because refusals are a reflection of question sensitivity rather than difficulty (Tourangeau, Rips, & Rasinski, 2000), this study focuses on item nonresponse due to “I don’t know” answers. It should be noted that, across the selected subjective probability questions in this study, “I don’t know” accounts for a larger proportion of nonresponse than refusals, while this is not true for the non-probability questions. (See Appendix 1 for the proportions of “I don’t know” nonresponse, refusal nonresponse and response across six selected questions. Refusal rates are low, except for the bank balance question. No specific pattern emerges in analysis of refusals.)

Independent Variables

The hypotheses are tested at individual and group levels. Hence, independent variables are created separately at these levels in such a way that reflects a variation in time orientation.

Cultural groups

Building on the tight connection between time orientation and culture, we first use a combination of country, race, ethnicity and interview language as “culture” for the group-level analysis. Interview language is a reflection of true cultural orientation for monolinguals and a product of convenience for multilinguals (i.e., a preferred language). Regardless, language used in survey interviews and conversations alike is shown to bring its cultural norms to the discourse (Bond, 1983; Lee, Nguyen, & Tsui, 2011; Lee & Schwarz, 2014; Lee, Schwarz, & Goldstein, 2014; Marian & Kaushanskaya, 2004; Ross, Xun, & Wilson, 2002).

Specifically, we use the following groups to delineate culture: at the country level, the U.S., the U.K., Austria, Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, France, Spain, Italy, Greece, Israel and China. For multi-racial, multi-ethnic or multi-lingual countries, we further partition as best as the data allow in the following way. For the U.S., we combine race, ethnicity, and interview language, resulting in the categories of non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, Hispanics interviewed in English, and Hispanics interviewed in Spanish. Those reported as non-Hispanic other race in HRS are excluded, because of its small sample size and their unascertainable cultural backgrounds. For the U.K., we use Whites and non-Whites, the only culture-relevant characteristic available in the ELSA public use data. Note that the majority of non-Whites in the U.K. are Blacks and those with South Asian backgrounds (UK Office of National Statistics, 2013). For Israel, we further divide the sample by interview language (Russian, Hebrew and Arabic) as Hebrew is spoken mainly by Jewish, Russian by immigrant Jewish, and Arabic by Arabs in Israel (Shohamy, 2006).

European countries in SHARE may be combined into two large groups delineated by language and geography: 1) Germanic-speaking countries in Northern Europe (Austria, Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands) and 2) Romance-speaking countries along with the Mediterranean geography (France, Spain, Italy and Greece). In sum, this study includes 12 countries, where the U.S. is further divided into 4 groups; the U.K. into 2 groups; and Israel into 3 groups.

Time orientation indicators

At the country level, we use the score on future orientation practices from the GLOBE Project reported in Ashkanasy et al. (2004) as a time orientation indicator. While this score is available for all 12 countries in this study, we exclude Israel, because, despite its apparent linguistic diversity, the language used in the GLOBE data collection for Israel cannot be ascertained.

At the individual level, we use the following four indicators: 1) present time orientation, 2) future optimism, 3) sense of control, and 4) religiosity. Note that these are measured in a self-administered module assigned to roughly a random half of the sample in HRS and SHARE except for France. Hence, France, the U.K., and China are not included in the individual-level analysis. Also, present-time orientation and sense of control are not asked in SHARE and, hence, not included in the analysis.

Present-time orientation is measured in HRS with rating a statement, “I live life one day at a time and don’t really think about the future,” on a 6-point agreement scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. Future optimism is measured with a statement, “I am always optimistic about my future,” on the 6-point agreement scale in HRS and “I feel that the future looks good for me” on a 4-point scale from “never” to “often” in SHARE. Sense of control is measured with a question, “Using a 0 to 10 scale where 0 means ‘no control at all’ and 10 means ‘very much control,’ how would you rate the amount of control you have over your health these days?”, in HRS. Religiosity is measured with a statement, “I believe in a God who watches over me,” on the 6-point agreement scale in HRS and with a question, “Thinking about the present, about how often do you pray?” on a 6-point scale from “never” to “more than once a day” in SHARE.

While future optimism, sense of control and religiosity are not direct measures of time orientation, the literature shows time orientation conceptually encompassing these traits (Strathman, Gleicher, Boninger, & Edwards, 1994) and a theoretical and empirical relationship between time orientation and these traits for future prediction (Boniwell & Zimbardo, 2004; Nurmi, 1987). Those who are optimistic tend to develop future plans as a coping strategy (Scheier, Carvers, & Bridges, 1994) and anticipate positive outcomes (Boniwell & Zimbardo, 2004), making optimism related to future orientation (Boyd & Zimbardo, 2005; Marko & Savickas, 1998). Individuals with low sense of control view external forces determining their life and deem future planning irrelevant, making sense of control as a strong correlate of future orientation (Branningan, Shahon, & Schaller, 1992; Shipp, Edwards, & Lambert, 2009). Moreover, sense of control over health is shown to be related to general sense of control and particularly relevant for older persons (Lachman, 1986; Lachman & Weaver, 1986). Religiosity reflects the locus of control being external not internal, making high religiosity negatively related to future orientation (Carter, McCollough, Kim-Spoon, Corrales, & Blake, 2012; Öner-Özkan, 2007). In fact, there are a few items on the Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory (ZTPI) reflecting these constructs, such as Item 3: “Fate determines much in my life,” Item 33: “Things rarely work out as I expected,” and Item 38: “My life path is controlled by forces I cannot influence.” Clearly, Items 3 and 38 are negatively related to sense of control and Item 33 to optimism. Given these and the older age of our study sample, we expect the combination of present-time orientation, future optimism, sense of control and religiosity, while not perfect, to approximate various aspects of future time orientation.

Control Variables

We control for age in years, gender and educational attainment across all surveys as they are known correlates of item nonresponse (e.g., Colsher & Wallace, 1989; Elliott, Edwards, Angeles, Hambarsoomians, & Hays, 2005). Because comparable education measures across countries and surveys are not readily available, it is harmonized into a single variable with three categories indicating low, middle and high education, roughly equivalent to less than high school, high school and some college or more education in the U.S. Appendix 2 describes the detail of this harmonization.

Analysis Procedure

Focusing on respondents aged 50 years old or older, the analysis is conducted in four steps. We first examine item nonresponse rates due to “I don’t know” answers on six selected questions across cultural groups. By combining the item nonresponse rates of three subjective probability questions and the future orientation score from the GLOBE Project, we examine their relationship at the country level. Second, we compare the nonresponse rates across cultural groups by controlling for potential demographic differences using logistic regression models. Within each survey, the cultural group with the lowest odds of saying, “I don’t know”, is used as a reference group.

Third, the individual-level nonresponse is examined for HRS and SHARE by combining item nonresponse on the six selected questions into two variables: item nonresponse to any of the subjective probability questions and item nonresponse to any of the non-probability questions. In logistic regression, we model these variables onto cultural groups while controlling for potential covariates and consider these as base models. We then add indicators relevant to time orientation to the base models and consider these as full models. We compare the fit between the base models and the full models using likelihood ratio tests. This allows us to examine whether time orientation indicators have meaningful values for explaining item nonresponse and whether the values are equivalent between subjective probability questions and non-probability questions. This analysis is based on the sample with complete time orientation indicators.1

The last step of analysis examines potential nonresponse bias in the subjective probability about life expectancy. This is motivated by a recent study that shows a higher subsequent mortality rate by nonrespondents to this question than respondent in HRS (Lee & Smith, 2016), which implies that nonresponse itself contains information relevant to mortality. Although subsequent mortality status would be ideal for examining nonresponse bias, mortality data beyond HRS have limitations (e.g., Anne & Doblhammer, 2010; Romero-Ortuno, Fouweather, & Jagger 2013). Given this, we choose to examine self-rated health between respondents and nonrespondents of the life expectancy question, as both self-rated health and subjective life expectancy are known to predict mortality (Jylhä, 2011) and asked in all four surveys. Hence, all surveys are included in this nonresponse bias analysis. We use self-rated health by combining “poor” and “fair” categories in HRS, SHARE, and ELSA and “very poor” and “poor” in CHARLS to note negative health and the remaining categories to note positive health.

Results

This paper presents results from a single year or wave of respective surveys; however, it should be noted that data from other years or waves show consistent results. Because results from weighted and unweighted analyses are comparable and population-level estimates are not of particular interest, we present unweighted analyses in this study.

Group-Level Item Nonresponse

Overall, item nonresponse rates of the subjective probability questions range from 0.89% on receiving an inheritance in ELSA to 20.07% on life expectancy in CHARLS. Non-probability questions show a similar range of item nonresponse rates as low as 0.02% for self-rated health in SHARE and as high as 15.25% of bank account values in HRS. When examining these rates by cultural groups, a wide variation emerges within each question and between subjective probability and non-probability questions as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Rates of “I Don’t Know” Item Nonresponse of Subjective Probability and Non-Probability Questions by Country, Race, Ethnicity, and Interview Language, 2006 Health and Retirement Study, Wave 1 of English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, Wave 1 of Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe and 2011 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study

| Subjective Probability Expectation Questions | Non-Probability Questions | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Receive Inheritance | Life Expectancy | Financial Situations | Self-Rated Health | Body Weight | Bank Account Value | |||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| n | % | SE(%) | n | % | SE(%) | n | % | SE(%) | n | % | SE(%) | n | % | SE(%) | n | % | SE(%) | |

| Health and Retirement Study (HRS) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Total | 16,175 | 2.38 | 0.12 | 15,584 | 4.83 | 0.17 | 16,217 | 5.88 | 0.18 | 16,423 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 16,308 | 0.68 | 0.06 | 12,494 | 15.25 | 0.32 |

| US White (Ref.) | 12,405 | 1.74 | 0.12 | 12,000 | 2.82 | 0.15 | 12,432 | 3.80 | 0.17 | 12,568 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 12,468 | 0.57 | 0.07 | 10,249 | 14.04 | 0.34 |

| US Black | 2,233 | 4.34*** | 0.43 | 2,129 | 9.49*** | 0.64 | 2,246 | 8.06*** | 0.57 | 2,294 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 2,285 | 0.96 | 0.20 | 1,325 | 22.04*** | 1.14 |

| US Hispanic, English | 785 | 3.18* | 0.63 | 757 | 5.55** | 0.83 | 787 | 7.12*** | 0.92 | 798 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 792 | 0.76 | 0.31 | 529 | 15.50 | 1.57 |

| US Hispanic, Spanish | 752 | 6.25*** | 0.88 | 698 | 24.50*** | 1.63 | 752 | 32.58*** | 1.71 | 763 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 763 | 1.57* | 0.45 | 391 | 23.53*** | 2.15 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Total | 11,166 | 0.89 | 0.09 | 11,172 | 1.97 | 0.13 | 11,174 | 2.51 | 0.15 | 11,355 | 0.12 | 0.03 | n.a. | 9,892 | 1.63 | 0.13 | ||

| UK White (Ref.) | 10,867 | 0.75 | 0.08 | 10,873 | 1.78 | 0.13 | 10,875 | 2.23 | 0.14 | 11,025 | 0.09 | 0.03 | n.a. | 9,630 | 1.63 | 0.13 | ||

| UK Non-White | 298 | 5.70*** | 1.34 | 298 | 8.72*** | 1.63 | 298 | 12.75*** | 1.93 | 318 | 0.63 | 0.44 | n.a. | 252 | 1.19 | 0.68 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Total | 23,117 | 3.30 | 0.12 | 23,075 | 10.60 | 0.20 | 23,138 | 6.03 | 0.16 | 23,298 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 23,236 | 0.83 | 0.06 | 11,343 | 9.25 | 0.27 |

| Austria (Ref.) | 1,549 | 0.84 | 0.23 | 1,549 | 2.52 | 0.40 | 1,551 | 1.74 | 0.33 | 1,552 | 0.00 | n.a. | 1,535 | 0.26 | 0.13 | 807 | 13.01 | 1.18 |

| Germany | 2,923 | 1.71** | 0.24 | 2,924 | 3.49# | 0.34 | 2,932 | 2.59 | 0.29 | 2,939 | 0.00 | n.a. | 2,935 | 0.24 | 0.09 | 1,447 | 4.77*** | 0.56 |

| Sweden | 2,975 | 2.15*** | 0.27 | 2,958 | 3.85* | 0.35 | 2,979 | 2.18 | 0.27 | 2,993 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 2,988 | 0.80** | 0.16 | 1,846 | 3.09*** | 0.40 |

| Netherlands | 2,841 | 2.78*** | 0.31 | 2,836 | 6.42*** | 0.46 | 2,845 | 4.18*** | 0.38 | 2,860 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 2,857 | 0.53 | 0.14 | 1,711 | 9.70* | 0.72 |

| Spain | 2,317 | 3.54*** | 0.38 | 2,310 | 12.16*** | 0.68 | 2,304 | 8.03*** | 0.57 | 2,341 | 0.00 | n.a. | 2,338 | 2.52*** | 0.32 | 1,250 | 14.48 | 1.00 |

| Italy | 2,489 | 1.81** | 0.27 | 2,486 | 10.02*** | 0.60 | 2,492 | 4.94*** | 0.43 | 2,500 | 0.00 | n.a. | 2,498 | 0.56 | 0.15 | 990 | 8.48** | 0.89 |

| France | 2,911 | 6.11*** | 0.44 | 2,911 | 16.45*** | 0.69 | 2,914 | 9.57*** | 0.55 | 2,968 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 2,955 | 0.74* | 0.16 | 1,614 | 11.15 | 0.78 |

| Greece | 2,662 | 4.58*** | 0.41 | 2,661 | 10.22*** | 0.59 | 2,663 | 6.20*** | 0.47 | 2,666 | 0.00 | n.a. | 2,663 | 0.41 | 0.12 | 772 | 10.23 | 1.09 |

| Israel Total | 2,450 | 5.35*** | 0.45 | 2,440 | 29.88*** | 0.93 | 2,458 | 14.48*** | 0.71 | 2,479 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 2,467 | 1.54*** | 0.25 | 906 | 14.13 | 1.16 |

| Israel, Russian | 192 | 2.60*** | 1.15 | 192 | 26.56*** | 3.19 | 192 | 12.50*** | 2.39 | 192 | 0.00 | n.a. | 192 | 0.00 | n.a. | 95 | 7.37 | 2.68 |

| Israel, Hebrew | 1,928 | 5.71*** | 0.53 | 1,924 | 28.64*** | 1.03 | 1,936 | 14.10*** | 0.79 | 1,955 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 1,944 | 1.54*** | 0.28 | 806 | 14.89 | 1.25 |

| Israel, Arabic | 330 | 4.85*** | 1.18 | 324 | 39.20*** | 2.71 | 330 | 17.88*** | 2.11 | 332 | 0.00 | n.a. | 331 | 2.42* | 0.84 | 5 | 20.00 | 17.89 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) a | ||||||||||||||||||

| China | n.a. | 13,791 | 20.07 | 0.34 | n.a. | 13,791 | 0.62 | 0.07 | n.a. | 2,221 | 5.22 | 0.47 | ||||||

“I don’t know” and refusal nonresponses cannot be differentiated in the data and, hence, combined into one category.

Estimates significantly different from the reference group within survey at p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p<0.001

In the U.S., item nonresponse rates across all subjective probability questions are significantly lower for Whites than for other groups. Notably, the highest item nonresponse rates on all subjective probability questions are observed from Hispanics interviewed in Spanish. For example, 32.58% of Spanish-interviewed Hispanic respondents said, “I don’t know,” to the financial situation question. This rate is nine times higher than White respondents’ (3.80%). Among Hispanics, nonresponse rates on all subjective probability questions are significantly higher for those interviewed in Spanish than those in English (p=0.005).

In the U.K., item nonresponse rates on all subjective probability questions are significantly higher for non-Whites than for Whites. Among European countries in SHARE, item nonresponse rates of the probability questions are the lowest for Austria at 0.84% on inheritance, 2.52% on life expectancy and 1.74% on financial situation and the highest for France at 6.11%, 16.45% and 9.57% for respective questions. Although not as obvious for the inheritance question, Germanic-speaking countries and Romance-speaking countries combined with Greece form two distinctive clusters with respect to item nonresponse rates for the life expectancy question and the financial situation questions. The latter group shows much higher nonresponse rates. Further, these rates are higher for Israel than for any other countries in SHARE. Especially on the life expectancy question, nonresponse rate is almost 30% in Israel, with a substantial variation by interview language. The highest item nonresponse rate is observed for respondents in Israel interviewed in Arabic at 39.20%, which further means that data on subjective life expectancy are missing for two out of five Arabic-interviewed Israeli respondents.

While this culture-specific variation in item nonresponse rates holds across all subjective probability questions, the inheritance question shows lower item nonresponse rates and less cultural variation than the other two subjective probability questions. For example, differences in the nonresponse rates between Whites and Spanish-interviewed Hispanics in the U.S. are 4.51 percent points for the inheritance question, 21.68 for the life expectancy question and 28.78 for the financial situation question.

This differential item nonresponse pattern is not observed for non-probability questions. The self-rated health question shows very low nonresponse rates, virtually 0% across all groups. Although considered sensitive, body weight is subject to relatively low nonresponse rates ranging up to 2.52%. Item nonresponse rates are higher for the bank balance question than the other two non-probability questions across all groups with some variation: in HRS, higher item nonresponse rates for Blacks and Spanish-interviewed Hispanics than for Whites; in ELSA, no difference between Whites and non-Whites; and no particular pattern associated with country or language in SHARE. For example, in Austria, nonresponse rates are consistently the lowest among countries in SHARE across all subjective probability questions at less than 3% and low on self-rated health at 0% and body weight at 0.26%; however, its nonresponse rate on the bank balance question is on a higher end at 13.01%. Moreover, among all six selected questions, the bank balance question shows the highest item nonresponse rates for Germanic-language-speaking countries in SHARE. However, this is not the case for other European countries in SHARE.

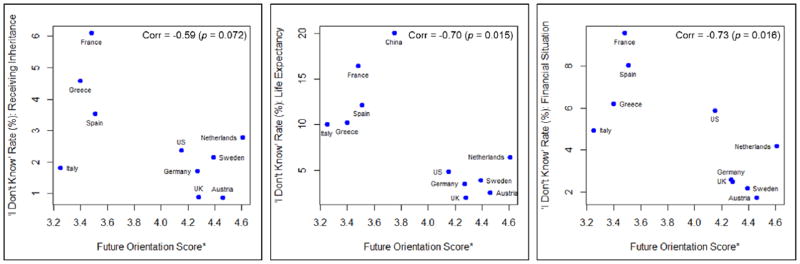

Group-level item nonresponse rates of the three subjective probability questions from Table 1 are plotted against the future orientation scores from the GLOBE Project along with estimated correlation coefficients in Figure 1. There are two distinctive clusters in the figures: one with low nonresponse rates and high future orientation scores and the other with high nonresponse rates and low future orientation scores. The first cluster includes Anglo and Germanic-language-speaking countries, whereas the second includes Romance-language speaking or Mediterranean European countries and China. The estimated correlation coefficients between item nonresponse rates and future orientation scores are negative and significant at α=0.05 for all subjective probability questions. This pattern does not apply to the non-probability questions whose item nonresponse rates are not related to future time orientation.

Figure 1.

Relationship between Country-Level Future Orientation Score and “I Don’t Know” Item Nonresponse Rates on Subjective Probability Questions, 2006 Health and Retirement Study, Wave 1 of English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, Wave 1 of Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe, 2011 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, and Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness Research Project

* Country-level future orientation scores come from Table 13.5 of Ashkanasy, Gupta, Mayfield, & Trevor-Roberts (2004) based on the data from the Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness Research Project; the higher the score, the more future oriented the country practices.

Cultural groups compared above may be different with respect to age, gender and education, and item nonresponse may be a function of these socio-demographics. In order to examine the influence of cultural backgrounds on item nonresponse independent of the socio-demographics, item nonresponse is modeled as a function of cultural group, age, gender, and education through logistic regression. Table 2 includes the results for life expectancy; results for the other two subjective probability questions are in Appendix 4. Generally, younger age, male and higher education are associated significantly lower odds of saying, “I don’t know”, compared to their counterparts, although not universally so across surveys. The cultural group differences in nonresponse rates remain consistently significant even after holding the socio-demographic differences constant. Most notably, odds of saying, “I don’t know,” to the life expectancy question for Spanish-interviewed Hispanics is 7.26 [95% CI: 5.76–9.16] times of Whites’ in the U.S. Non-White respondents in the U.K. are far less likely to respond than Whites with an odds ratio of 7.65 [95% CI: 4.92–11.92]. All countries in SHARE other than Germany show significantly higher odds of nonresponse, compared to Austria. Odds ratios are particularly higher for Romance-language speaking or Mediterranean European countries (from 4.21 to 7.40) and for the cultural groups in Israel (from 7.32 to 28.37) than countries speaking Germanic languages.

Table 2.

Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals from Logistic Regression of “I Don’t Know” Item Nonresponse on Subjective Life Expectancy by Country, Race, Ethnicity, and Interview Language Controlling for Age, Sex and Education, 2006 Health and Retirement Study, Wave 1 of English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, Wave 1 of Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe and 2011 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study

| Odds Ratio [95% CI] | |

|---|---|

| Health and Retirement Study (HRS) | |

| (n=15,600) | |

| US Black vs. US White | 3.13 [2.58,3.79] |

| US Hispanic, English vs. US White | 1.79 [1.27,2.53] |

| US Hispanic, Spanish vs. US White | 7.26 [5.76,9.16] |

| Age (years) | 1.04 [1.03,1.05] |

| Male vs. Female | 0.64 [0.54,0.75] |

| High school vs. < High school | 0.46 [0.39,0.55] |

| Some college+ vs. < High school | 0.29 [0.22,0.38] |

| English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) | |

| (n=11,490) | |

| UK Non-White vs. UK White | 7.65 [4.92,11.92] |

| Age (years) | 1.07 [1.05,1.08] |

| Male vs. Female | 0.80 [0.60,1.06] |

| Middle vs. Low education | 0.69 [0.32,1.47] |

| High vs. Low education | 0.79 [0.53,1.16] |

| China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) a | |

| (n=13,753) | |

| Age (years) | 1.00 [1.00,1.01] |

| Male vs. Female | 0.92 [0.85,1.00] |

| Middle vs. Low education | 0.74 [0.64,0.86] |

| High vs. Low education | 0.74 [0.43,1.26] |

| Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) | |

| (n=21,418) | |

| Germany vs. Austria | 1.45 [0.99,2.12] |

| Sweden vs. Austria | 1.63 [1.12,2.37] |

| Netherlands vs. Austria | 2.84 [1.99,4.06] |

| Spain vs. Austria | 4.71 [3.30,6.71] |

| Italy vs. Austria | 4.54 [3.21,6.44] |

| France vs. Austria | 7.40 [5.26,10.42] |

| Greece vs. Austria | 4.21 [2.97,5.99] |

| Israel, Russian vs. Austria | 17.68 [11.04,28.32] |

| Israel, Hebrew vs. Austria | 17.32 [12.34,24.31] |

| Israel, Arabic vs. Austria | 28.37 [18.77,42.88] |

| Age (years) | 1.04 [1.03,1.04] |

| Male vs. Female | 0.82 [0.74,0.90] |

| Middle vs. Low education | 0.84 [0.62,1.15] |

| High vs. Low education | 0.73 [0.64,0.85] |

“I don’t know” and refusal nonresponses cannot be differentiated in the data and, hence, combined into one category.

Individual-Level Item Nonresponse

Table 3 includes odds ratios of nonresponse to any of the subjective probability questions and to any of the non-probability questions from the base and full logistic regression models. In the base model, the cultural group approximated through nationality, race, ethnicity and language is a strong predictor of nonresponse for the subjective probability questions for HRS and SHARE in a consistent way as in Table 2. The effect of cultural group is unclear for the non-probability questions, however. For instance, odds ratio of Arabic-speaking Israelis saying, “I don’t know,” to the subjective probability questions compared to Austrians is 29.58, significant at p<0.001, while there is no significant difference on the non-probability questions. This cultural variation remains virtually the same in the full models, which incorporate indicators relevant to time orientation.

Table 3.

Odds Ratios of “I Don’t Know” Item Nonresponse on Subjective Probability Questions and Non-Probability Questions in Base Model (Logistic Regression without Psycho-Social Characteristics) and Full Model (Logistic Regression with Psycho-Social Characteristics), 2006 Health and Retirement Study and Wave 1 of Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe

| Health and Retirement Study (HRS) | Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Subjective Probability Questions (n=5,921) | Non-Probability Questions (n=4,797) | Subjective Probability Questions (n=12,652) | Non-Probability Questions (n=6,402) | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Base Model | Full Model | Base Model | Full Model | Base Model | Full Model | Base Model | Full Model | |

| Time-Orientation-Relevant Indicators | ||||||||

| Present time orientation | - | 1.09** | - | 1.00 | - | - | ||

| Future optimism | - | 1.05 | - | 1.02 | - | 0.86*** | - | 1.07 |

| Sense of control over health | - | 0.99* | - | 0.99* | - | - | ||

| Religiosity | - | 1.18* | - | 1.09 | - | 1.09*** | - | 0.97 |

| Cultural Group | ||||||||

| US Black vs. US White | 2.97*** | 2.76*** | 1.51*** | 1.43** | - | - | - | - |

| US Hispanic, English vs. US White | 2.18*** | 2.02** | 1.45 | 1.38 | - | - | - | - |

| US Hispanic, Spanish vs. US White | 7.92*** | 7.23*** | 1.81** | 1.72* | - | - | - | - |

| Germany vs. Austria | - | - | - | - | 1.22 | 1.24 | 0.35*** | 0.35*** |

| Sweden vs. Austria | - | - | - | - | 1.55* | 1.76* | 0.24*** | 0.23*** |

| Netherlands vs. Austria | - | - | - | - | 2.67*** | 2.77*** | 0.68* | 0.67** |

| Spain vs. Austria | - | - | - | - | 5.44*** | 5.18*** | 1.22 | 1.25 |

| Italy vs. Austria | - | - | - | - | 4.57*** | 4.17*** | 0.59** | 0.60* |

| Greece vs. Austria | - | - | - | - | 5.22*** | 4.57*** | 0.54** | 0.57** |

| Israel, Russian vs. Austria | - | - | - | - | 67.20*** | 71.87*** | 1.95 | 1.93 |

| Israel, Hebrew vs. Austria | - | - | - | - | 22.08*** | 23.31*** | 1.76*** | 1.72*** |

| Israel, Arabic vs. Austria | - | - | - | - | 29.58*** | 25.12*** | 2.00 | 1.90 |

| Control Variables | ||||||||

| Age (years) | 1.06*** | 1.06*** | 1.03*** | 1.03*** | 1.02*** | 1.02*** | 1.01 | 1.01 |

| Male vs. Female | 0.64*** | 0.67*** | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.76*** | 0.81** | 0.72*** | 0.70*** |

| Middle vs. Low education | 0.39*** | 0.42*** | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.66* | 0.70 | 0.93 | 0.92 |

| High vs. Low education | 0.24*** | 0.27*** | 0.63*** | 0.66* | 0.63*** | 0.66*** | 1.09 | 1.07 |

|

| ||||||||

| Model Fit | ||||||||

| −2 Log Likelihood | 2768.41 | 2743.17 | 4008.69 | 3998.55 | 6704.90 | 6670.47 | 3624.00 | 3621.18 |

| Likelihood Ratio Test | χ2 =25.24 (p<0.001) | χ2 =10.15 (p=0.038) | χ2 =34.44 (p<0.001) | χ2 =2.82 (p<0.245) | ||||

Significant effect at p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p<0.001

More importantly, these time orientation indicators are significant for predicting nonresponse to the subjective probability questions. In HRS, present time orientation and religiosity are positive predictors of nonresponse to these questions, while sense of control is a negative predictor. The more present-oriented and religious an individual, the more likely he or she says, “I don’t know,” to the subjective probability questions. On the other hand, the higher the sense of control, the lower nonresponse rates. On the non-probability questions, sense of control is the only significant covariate of nonresponse. In SHARE, both future optimism and religiosity are significant for explaining nonresponse on the subjective probability questions but in opposite directions (OR: 0.86 for future optimism and 1.09 for religiosity). These time orientation indicators play no role in examining nonresponse to the non-probability questions.

Adding time orientation indicators significantly improves our ability to explain nonresponse to the subjective probability questions in both HRS (χ2 =25.24; p<0.001) and SHARE (χ2 =34.44; p<0.001). Their value for the non-probability questions is unclear: they improve the fit for HRS (χ2 =10.15; p=0.038), but it is at a lower level than for the subjective probability questions. These indicators do not improve the model for SHARE (χ2 =2.82; p=0.245). (Note that these indicators at the cultural group level are distributed in such a way that follows cultural variations in time orientation. For instance, sense of control is significantly higher for Whites than other groups in HRS.)

Potential Nonresponse Bias on Subjective Life Expectancy

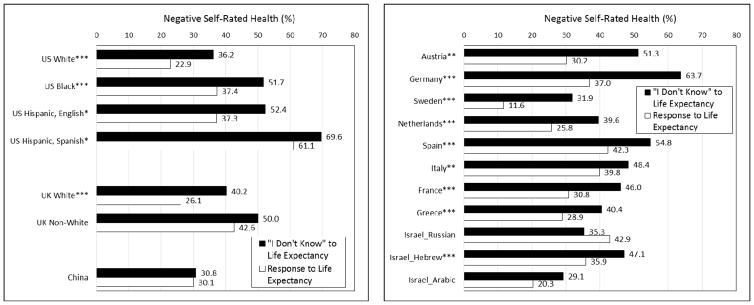

Self-rated health is compared between respondents and nonrespondents to the life expectancy question in Figure 2 in order to assess their comparability in health. Nonrespondents are associated with worse negative health than respondents across all cultural groups, except for Chinese and Israelis interviewed in Russian. For instance, in Germany, negative health is reported by 37.0% of respondents and by 63.7% of nonrespondents, a 26.7 percent point difference (p<0.001). Although the difference between respondents and nonrespondents is not significant for U.K. non-Whites and for Arabic-interviewed Israelis, this is mainly due to the small sample sizes and the general pattern of worse health by nonrespondents holds throughout cultural groups.

Figure 2.

Negative Self-Rated Health Rates by Subjective Life Expectancy Item Response Status by Country, Race, Ethnicity, and Interview Language2006 Health and Retirement Study, Wave 1 of English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, Wave 1 of Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe and 2011 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study a, b

aNegative health combined two most negative categories on self-rated health. These are “fair” and “poor” for all surveys but the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study for which “poor” and “very poor” were combined.

b“I don’t know” and refusal nonresponses cannot be differentiated in the data and, hence, combined into one category for the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study.

* Significant difference in negative health rates between who gave a response to and who said, “I don’t know,” to subjective life expectancy based on Pearson χ2 test at p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p< 0.001

Discussion

Our study showed that respondents from various cultural groups encompassing nationality, race, ethnicity, and language said, “I don’t know,” to subjective probability questions than to non-probability questions. More importantly, on subjective probability questions, there was a cultural variation in item nonresponse rates. Groups associated with Anglo cultures or Germanic languages consistently showed lower nonresponse rates than groups associated with Romance languages, or Mediterranean, Arab or Asian cultures. This culture-specific pattern was not observed for non-probability questions. Among subjective probability questions, this cultural variation was more apparent for topics about which respondents have little personal information, such as life expectancy and financial situations, compared to receiving an inheritance.

Analysis linking item nonresponse rates on subjective probability questions and future time orientation scores at the country level showed a significant negative relationship: the more future-oriented a country, the lower the nonresponse rates. On the other hand, for non-probability questions, time orientation did not differentiate the nonresponse rates.

A significant relationship between time orientation and nonresponse on subjective probability questions was observed at the individual level as well. In particular, respondents who were present-oriented and/or religious were more likely to say, “I don’t know”, than the remainders, while those who were optimistic about the future and/or with a high sense of control were less likely to do so than the counterparts. These indicators significantly improved our ability to explain nonresponse on subjective probability questions.

When combined together, results from our study support the hypotheses: subjective probability questions are more difficult for those from present- or past-oriented cultures than those from future-oriented cultures, resulting in differential item nonresponse rates due to “I don’t know”; and this variation is applicable at the group level as well as the individual level. More importantly, our study suggests that nonresponse on subjective probability questions is more than random noise and includes information relevant to substantive question topics. On the life expectancy question, a high item nonresponse rate is concerning, given its importance for policy-relevant analyses (e.g. Perozek, 2008). This concern becomes exacerbated if nonrespondents are different than respondents, especially when nonrespondents have worse health than respondents as shown in this study. If relying on respondents only, a large proportion of certain cultural groups, often associated with minority status (e.g., Spanish-interviewed Hispanics in the U.S., Arabic-interviewed Israelis), would be ignored in the analysis. This is likely to incur an underestimation of subsequent mortality and biases in analyses involving data about subjective life expectancy.

Time orientation is a complex concept, “resembling other well-known psychological measures (McGrath & Tschan, 2004).” As noted earlier in this study and also in the literature, time orientation is related to important traits, such as optimism, sense of control and religiosity, shown to affect human behaviors. If time orientation is a driver of nonresponse on subjective probability questions, this also implies that these traits also affect the nonresponse mechanism. This further poses challenges to cross-cultural research using data from such questions. There may be systematic nonresponse bias, particularly for groups who are not future oriented. This adversely affects comparability.

Of course, our study is not without limitations. Most importantly, it is based on secondary data not collected for the purpose of this study. Hence, even though the results of this study should be robust with respect to external validity by using population-based data, what this study can address is bounded by information available in HRS, SHARE, ELSA and CHARLS. An ideal data set will be based on a representative sample from an extensive list of cultural groups that cut across various time orientations and include a set of items measuring time orientation as well as other psychological traits relevant for nonresponse (e.g., sense of control), subjective probability questions and non-probability questions comprehensively. Simply put, such data do not exist, and collecting such data will present own challenges.

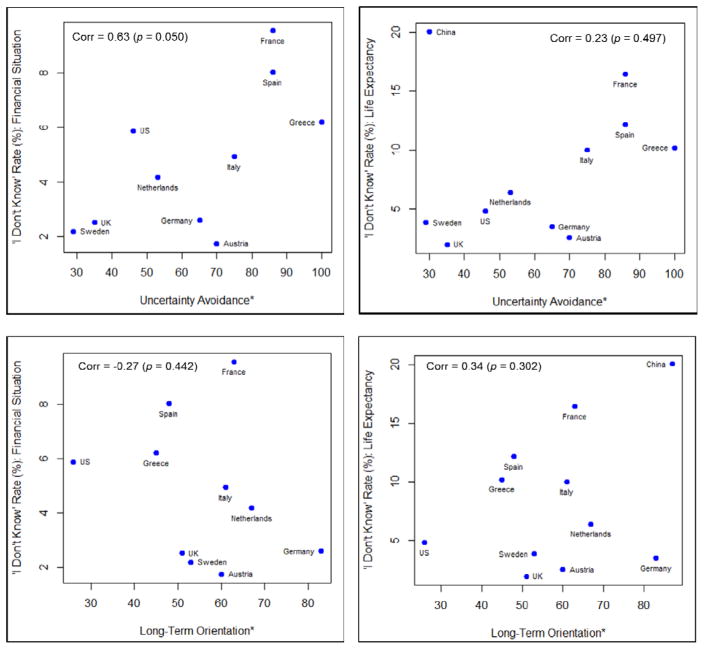

One may argue whether the systematic nonresponse pattern observed for subjective probability questions in this study reflects some other characteristics not accounted for in this study rather than time orientation. It should be emphasized that time orientation explained a part of, not the entirety of, nonresponse, as a portion of variance in nonresponse remained unexplained (see log likelihoods reported for models in Table 3). In particular, uncertainty avoidance, long-term orientation and numeracy, which also vary by culture and/or country, are worth further considerations for this culture-specific nonresponse pattern.

Uncertainty avoidance, one of the Hofstede’s cultural dimensions (Hofstede, 2011), may prompt respondents to say something other than, “I don’t know.” Hence, the role of future time orientation examined in this study should not be taken as though having an effect orthogonal to uncertainty avoidance. As seen in top two plots in Appendix 5, uncertainty avoidance, in fact, plays a role in nonresponse rates but in a direction opposite of what would be expected. There is no evidence that long-term orientation, another cultural dimension noted by Hofstede (Hofstede, 2011), is related to the item nonresponse rates in bottom two plots in Appendix 5. Adult numeracy scores reported for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries by the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (scores available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932897211) do not support the effect of numeracy on nonresponse to subjective probability questions. For instance, the U.S., a country with low item nonresponse rates, scored lower on numeracy than France and Italy and comparably to Spain, countries with high nonresponse rates in this study. Also note that if numeracy is the driver of the culture-specific nonresponse pattern, this pattern should be observed for the bank account value question, which was not in our analysis.

Other factors, such as respondent fatigue, unfamiliarity with probability questions or lack of interest in subjective probability questions, may explain nonresponse in general but not necessarily the pattern observed in this study. It is difficult to imagine that, for example, Spanish-interviewed Hispanics in HRS are more fatigued than Whites, when asked about subjective probabilities. Moreover, within the subjective probability section, three questions chosen in this study were asked in the order of financial situations, inheritance and life expectancy. Item nonresponse rates did not increase or decrease in this sequence. If unfamiliarity or lack of interest was to explain this pattern, this should emerge across all subjective probabilities. However, the culture-specific nonresponse pattern varied by the type of future events asked.

With nonresponse on the subjective life expectancy question, some may wonder whether it is a function of objective life expectancy, making respondents in countries with lower objective life expectancy to say, “I don’t know.” This was also not supported. Israel showed the highest nonresponse rate on the life expectancy question but has one of the longest objective life expectancy. Among countries considered in this study, life expectancy at birth is highest for Italy at 83 years old according to World Health Organization (2014) and is at 82 years old for Israel.

One may wonder whether the culture-specific item nonresponse pattern is applicable beyond the subjective probability questions in this study. Until we analyze all variables in all surveys, this question remains to be unascertained. Because each survey reflects social systems and programs related to health and retirement in corresponding countries, even if we are to carry out such analysis, there are very few comparable questions across surveys other than basic socio-demographic questions. Even education, one of the basic characteristics, was not readily comparable and had to be harmonized as shown in Appendix 2. While imperfect, we believe the questions included in this study provide a good representation of frequently asked survey questions.

Obviously, question difficulty matters for data quality. The level of difficulty is influenced by factors beyond typical respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics. This study finds that the difficulty depends on the topic of the question. Some questions, such as self-rated health, may result in virtually no nonresponse, but some, such as those using a subjective probability format, may results in nonresponse rates as high as 40%. Furthermore, culture-relevant traits, such as time orientation, may influence the difficulty level of certain question types, producing a culture-specific nonresponse pattern.

Findings in this study warrant a number of future studies. First, reasons why respondents say, “I don’t know,” could be examined in finer detail. Qualitative studies, such as cognitive interviews, with respondents from various cultural groups may provide insightful contexts. Second, time orientation combined with other culture-relevant psychological traits may explain other response patterns on subjective probability questions (e.g., pessimism on reporting 0% chance). In fact, Lee and Smith (2016) allude cultural differences in responses heaping at 0, 50 and 100 on the subjective life expectancy question. Using a more complete list of cultural traits beyond time orientation, various response patterns can be examined. Third, especially as data collection waves grow in the databases used in this study, nonresponse bias analysis can be extended by linking response patterns on subjective probability questions and actual outcomes (e.g., response to the subjective probability question about financial situations in five years versus actual financial situations five years after the probability question is administered).

Broadly speaking, it is clear that cultural norms (e.g., time orientation) are relevant to cognition and that cultural norms affect survey measurement through cognition. Ultimately, an effort to build a framework of cross-cultural measurement by scrutinizing the role of cultural norms beyond the Anglo American context on survey measurement will contribute to advancing measurement equivalence, a difficult yet vital task persistently concerning cross-cultural research (Scheuch, 1968).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported partly by the National Institute of Aging of the National Institutes of Health [grant number U01 AG009740].

Appendix 1

Detailed Item Nonresponse (“I Don’t Know” (DK) and Refusal (REF)) and Response (RES) Rates of Subjective Probability and Non-Probability Questions by Country, Race, Ethnicity, and Interview Language, 2006 Health and Retirement Study, Wave 1 of English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, Wave 1 of Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe and 2011 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study

| Subjective Probability Expectation Questions | Non-Probability Questions | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Receive Inheritance | Life Expectancy | Financial Situations | Self-Rated Health | Body Weight | Bank Account Value | |||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| n | DK (%) |

REF (%) |

RES (%) |

n | DK (%) |

REF (%) |

RES (%) |

n | DK (%) |

REF (%) |

RES (%) |

n | DK (%) |

REF (%) |

RES (%) |

n | DK (%) |

REF (%) |

RES (%) |

n | DK (%) |

REF (%) |

RES (%) |

|

| Health and Retirement Study (HRS) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| US Total | 16,363 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 96.5 | 15,642 | 4.8 | 0.4 | 94.8 | 16,363 | 5.8 | 0.9 | 93.3 | 16,424 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 99.9 | 16,424 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 98.6 | 13,999 | 13.6 | 10.8 | 75.6 |

| US White | 12,528 | 1.7 | 1.0 | 97.3 | 12,039 | 2.8 | 0.3 | 96.9 | 12,528 | 3.8 | 0.8 | 95.5 | 12,568 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 99.9 | 12,568 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 98.6 | 11,439 | 12.6 | 10.4 | 77.0 |

| US Black | 2,278 | 4.3 | 2.0 | 93.8 | 2,145 | 9.4 | 0.8 | 89.8 | 2,278 | 8.0 | 1.4 | 90.7 | 2,295 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 99.9 | 2,295 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 98.6 | 1,557 | 18.8 | 14.9 | 66.4 |

| US Hispanic, English | 795 | 3.1 | 1.3 | 95.6 | 759 | 5.5 | 0.3 | 94.2 | 795 | 7.0 | 1.0 | 92.0 | 798 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 99.8 | 798 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 98.5 | 595 | 13.8 | 11.1 | 75.1 |

| US Hispanic, Spanish | 762 | 6.2 | 1.3 | 92.5 | 699 | 24.5 | 0.1 | 75.4 | 762 | 32.2 | 1.3 | 66.5 | 763 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 763 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 98.4 | 408 | 22.6 | 4.2 | 73.3 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UK Total | 11,228 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 98.6 | 11,229 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 97.5 | 11,228 | 2.5 | 0.5 | 97.0 | 11,345 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 99.9 | n.a. | 10,528 | 1.5 | 6.1 | 92.3 | |||

| UK White | 10,924 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 98.7 | 10,925 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 97.8 | 10,924 | 2.2 | 0.5 | 97.3 | 11,027 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 99.9 | n.a. | 10,263 | 1.5 | 6.2 | 92.3 | |||

| UK Non-White | 304 | 5.6 | 2.0 | 92.4 | 304 | 8.6 | 2.0 | 89.5 | 304 | 12.5 | 2.0 | 85.5 | ,318 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 99.4 | n.a. | 265 | 1.1 | 4.9 | 94.0 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total | 23,215 | 3.3 | 0.4 | 96.3 | 23,215 | 10.5 | 0.6 | 88.9 | 23,215 | 6.0 | 0.3 | 93.7 | 23,306 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 99.9 | 23,291 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 98.9 | 12,761 | 8.2 | 11.1 | 80.7 |

| Austria | 1,551 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 99.0 | 1,551 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 97.4 | 1,551 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 98.3 | 1,552 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 1,552 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 98.7 | 922 | 11.4 | 12.5 | 76.1 |

| Germany | 2,933 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 98.0 | 2,933 | 3.5 | 0.3 | 96.2 | 2,933 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 97.4 | 2,939 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 2,939 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 99.6 | 1,721 | 4.0 | 15.9 | 80.1 |

| Sweden | 2,994 | 2.1 | 0.6 | 97.2 | 2,994 | 3.8 | 1.2 | 95.0 | 2,994 | 2.2 | 0.5 | 97.3 | 2,997 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 99.8 | 2,996 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 98.9 | 1,903 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 94.0 |

| Netherlands | 2,851 | 2.8 | 0.4 | 96.9 | 2,851 | 6.4 | 0.5 | 93.1 | 2,851 | 4.2 | 0.2 | 95.6 | 2,861 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 99.9 | 2,858 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 99.4 | 1,873 | 8.9 | 8.7 | 82.5 |

| Spain | 2,328 | 3.5 | 0.5 | 96.0 | 2,328 | 12.1 | 0.8 | 87.2 | 2,328 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 91.0 | 2,341 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 2,338 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 97.5 | 1,375 | 13.2 | 9.1 | 77.8 |

| Italy | 2,493 | 1.8 | 0.2 | 98.0 | 2,493 | 10.0 | 0.3 | 89.7 | 2,493 | 4.9 | 0.0 | 95.0 | 2,500 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 2,499 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 99.4 | 1,084 | 7.8 | 8.7 | 83.6 |

| France | 2,930 | 6.1 | 0.7 | 93.3 | 2,930 | 16.4 | 0.7 | 83.0 | 2,930 | 9.5 | 0.6 | 89.9 | 2,970 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 99.9 | 2,967 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 98.9 | 1,734 | 10.4 | 6.9 | 82.7 |

| Greece | 2,665 | 4.6 | 0.1 | 95.3 | 2,665 | 10.2 | 0.2 | 89.6 | 2,665 | 6.2 | 0.1 | 93.7 | 2,667 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 2,667 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 99.4 | 1,006 | 7.9 | 23.3 | 68.9 |

| Israel Total | 2,470 | 5.3 | 0.8 | 93.9 | 2,470 | 29.5 | 1.2 | 69.3 | 2,470 | 14.4 | 0.5 | 85.1 | 2,479 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 2,475 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 98.1 | 1,143 | 11.2 | 20.7 | 68.1 |

| Israel, Russian | 192 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 97.4 | 192 | 26.6 | 0.0 | 73.4 | 192 | 12.5 | 0.0 | 87.5 | 192 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 192 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 111 | 6.3 | 14.4 | 79.3 |

| Israel, Hebrew | 1,948 | 5.7 | 1.0 | 93.3 | 1,948 | 28.3 | 1.2 | 70.5 | 1,948 | 14.0 | 0.6 | 85.4 | 1,955 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 1,951 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 98.1 | 1,021 | 11.8 | 21.1 | 67.2 |

| Israel, Arabic | 330 | 4.9 | 0.0 | 95.2 | 330 | 38.5 | 1.8 | 59.7 | 330 | 17.9 | 0.0 | 82.1 | 332 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 332 | 2.4 | 0.3 | 97.3 | 11 | 9.1 | 54.6 | 36.4 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) a | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| China | n.a. | 13,791 | 20.1 | 79.9 | n.a. | 13,791 | 0.6 | 99.4 | n.a. | 2,221 | 5.2 | 94.8 | ||||||||||||

“I don’t know” and refusal responses cannot be differentiated in the data and, hence, combined into one category.

Appendix 2. Harmonization of Education Variable

Education is not a standardized system across countries.

Educational attainment is measured differently across four surveys used in this study and reflects own educational system in each country. We used the educational attainment measured in the Health and Retirement Study as the target. Specifically, we created a variable with categories of 1) less than high school, 2) high school diploma or equivalent, and 3) some college or more in order to indicate low, middle, and high education. Education variables in the other three surveys are harmonized as follows:

A. English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA)

The education variable in ELSA measures the highest educational qualification respondents obtained. This variable includes values 0 to 5, where 0 indicates “no qualification” (comparable to no education) and 5 “National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) 4/NVQ5/Degree or equivalent” (comparable to college degrees and above). We recoded the variables into the following three categories: 1) Low education equating to no qualification, NVQ2/General Certificate of Education (GCE) O level equivalent, and NVQ1/Certificate of Secondary Education (CSE) other grade equivalent; 2) Middle education equating to NVQ3/GCE A Level equivalent; and 3) High education equating to NVQ4/NVQ5/degree or equivalent and higher education below degree.

B. Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE)

The education variable in SHARE is based on the International Standard Classification of Education 1997. This variable includes levels 0 to 6, where 0 indicates “pre-primary education” (comparable to no education) and 6 “second stage of tertiary education” (comparable to advanced degrees that require more than course work). For detail, see http://www.uis.unesco.org/Library/Documents/isced97-en.pdf. We combined the values and used the following three categories: 1) Low education equating to pre-primary education, primary and lower secondary education; 2) Middle education equating to upper secondary education; and 3) High education equating to post-secondary, first stage of tertiary and second stage of tertiary education

C. China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS)

The education variable measures the highest level of education completed into levels 1 to 11, where 1 indicates “no formal education (illiterate)” (comparable to no education) and 11 “graduate from post-graduate, doctoral degree/Ph.D.” See http://charls.ccer.edu.cn/uploads/document/application/CHARLS2011________.doc for detail. We used the following three categories: 1) Low education equating to no formal education; 2) Middle education equating to completing elementary school; and 3) High education equating to completing middle school or above.

Appendix 3

Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals from Logistic Regression of “I Don’t Know” Item Nonresponse on Subjective Probability Questions and Non-Probability Questions with Psycho-Social Characteristics and Interviewer Characteristics, 2006 Health and Retirement Study

| Subjective Probability Questions (n=5,814) | Non-Probability Questions (n=4,718) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Odd Ratio [95% CI] | Odd Ratio [95% CI] | |

| Respondent Characteristics | ||

| Psycho-social characteristics | ||

| Present time orientation | 1.08 [1.01,1.16] | 1.00 [0.95,1.06] |

| Future optimism | 1.06 [0.99,1.13] | 1.02 [0.96,1.07] |

| Sense of control over health | 0.99 [0.99,1.00] | 0.99 [0.99,1.00] |

| Religiosity | 1.17 [1.00,1.37] | 1.05 [0.94,1.17] |

| Cultural Group | ||

| US Black vs. US White | 2.95 [2.19,3.99] | 1.32 [0.99,1.75] |

| US Hispanic, English vs. US White | 1.74 [1.04,2.87] | 1.39 [0.87,2.23] |

| US Hispanic, Spanish vs. US White | 6.26 [3.20,12.25] | 0.75 [0.39,1.43] |

| Control Variables | ||

| Age (years) | 1.07 [1.05,1.08] | 1.03 [1.02,1.04] |

| Male vs. Female | 0.64 [0.51,0.81] | 0.91 [0.76,1.09] |

| Middle vs. Low education | 0.40 [0.31,0.51] | 0.95 [0.75,1.21] |

| High vs. Low education | 0.26 [0.18,0.38] | 0.65 [0.48,0.88] |

| Interviewer Characteristics | ||

| Age (years) | 1.00 [0.99,1.02] | 1.00 [0.98,1.01] |

| Male vs. Feale | 1.00 [0.58,1.71] | 0.85 [0.50,1.43] |

| US Black vs. US White | 0.77 [0.45,1.32] | 1.48 [0.90,2.42] |

| US Hispanic vs. US White | 2.07 [0.47,9.08] | 5.17 [1.20,22.24] |

| Bilingual or Speak Spanish only vs. English only | 0.55 [0.14,2.08] | 0.42 [0.12,1.54] |

| No college vs. Some college+ education | 1.28 [0.89,1.85] | 0.91 [0.64,1.29] |

| Without vs. With previous HRS experience | 1.18 [0.63,2.20] | 1.38 [0.61,2.08] |

| Continuing vs. New HRS employee | 1.64 [0.76,3.32] | 1.37 [0.77,3.16] |

| ICC | 15.3% | 17.8% |

Appendix 4

Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals from Logistic Regression of Item Nonresponse on Subjective Probabilities of Receiving Inheritance and Financial Situations by Country, Race, Ethnicity, and Interview Language Controlling for Age, Sex and Education, 2006 Health and Retirement Study, Wave 1 of English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, and Wave 1 of Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe

| Receive Inheritance | Financial Situations | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Odds Ratio [95% CI] | Odds Ratio [95% CI] | |

| Health and Retirement Study (HRS) | ||

| n=16,331 | n=16,173 | |

| US Black vs. US White | 2.10 [1.62,2.73] | 1.82 [1.50,2.20] |

| US Hispanic, English vs. US White | 1.63 [1.07,2.50] | 1.75 [1.29,2.37] |

| US Hispanic, Spanish vs. US White | 2.18 [1.54,3.08] | 7.86 [6.35,9.73] |

| Age (years) | 1.05 [1.03,1.06] | 1.06 [1.05,1.07] |

| Male vs. Female | 0.91 [0.73,1.13] | 0.62 [0.54,0.73] |

| High school vs. < High school | 0.38 [0.30,0.48] | 0.37 [0.31,0.43] |

| Some college+ vs. < High school | 0.24 [0.17,0.35] | 0.17 [0.13,0.22] |

| English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) | ||

| n=11,161 | n=11,169 | |

| UK Non-White vs. UK White | 9.89 [5.56,17.32] | 9.10 [6.23,13.31] |

| Age (years) | 1.04 [1.02,1.07] | 1.05 [1.04,1.06] |

| Male vs. Female | 0.88 [0.59,1.33] | 0.67 [0.52,0.87] |

| Middle vs. Low education | 0.39 [0.10,1.56] | 0.27 [0.10,0.73] |

| High vs. Low education | 0.73 [0.42,1.27] | 0.52 [0.36,0.77] |

| Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) | ||

| n=21,342 | n=21,369 | |

| Germany vs. Austria | 2.09 [1.13,3.87] | 1.52 [0.97,2.39] |

| Sweden vs. Austria | 2.69 [1.47,4.90] | 1.27 [0.80,2.00] |

| Netherlands vs. Austria | 3.45 [1.91,6.22] | 2.52 [1.65,3.86] |

| Spain vs. Austria | 3.20 [1.74,5.91] | 4.14 [2.72,6.31] |

| Italy vs. Austria | 2.09 [1.12,3.90] | 2.93 [1.92,4.47] |

| France vs. Austria | 6.73 [3.78,11.98] | 4.47 [2.95,6.76] |

| Greece vs. Austria | 4.53 [2.52,8.15] | 3.01 [1.97,4.61] |

| Israel, Russian vs. Austria | 4.24 [1.47,12.27] | 12.00 [6.58,21.89] |

| Israel, Hebrew vs. Austria | 7.24 [4.03,12.98] | 10.28 [6.85,15.42] |

| Israel, Arabic vs. Austria | 2.75 [0.97,7.78] | 11.14 [6.59,18.84] |

| Age (years) | 1.04 [1.03,1.05] | 1.05 [1.04,1.05] |

| Male vs. Female | 0.79 [0.67,0.94] | 0.82 [0.72,0.93] |

| Middle vs. Low education | 0.43 [0.20,0.93] | 0.53 [0.33,0.86] |

| High vs. Low education | 0.75 [0.59,0.96] | 0.59 [0.48,0.73] |

Appendix 5

Relationship between Uncertainty Avoidance Score and “I Don’t Know” Item Nonresponse Rates on Subjective Probability Questions and between Long-Term Orientation Score and “I Don’t Know” Item Nonresponse Rates on Subjective Probability Questions, 2006 Health and Retirement Study, Wave 1 of English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, Wave 1 of Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe, 2011 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study

* Country-level uncertainty avoidance and long-term orientation scores come from Hofstede, Hofstede, & Minkov (2010).

Footnotes

With HRS, we also tested whether item nonresponse was a product of interviewer effects by adding interviewer-level data to the full models and found the role of time orientation remaining significant. Results are in Appendix 3.

References

- Andreski P, McGonagle K, Schoeni R. PSID Technical Series Paper 07–04. 2007. An analysis of the quality of the health data in the Panel Study of Income Dynamics. [Google Scholar]

- Anne S, Doblhammer G. Validity of the mortality follow-up in SHARE. 2010 Retrieved from: http://epc2010.princeton.edu/papers/100401.

- Ashkanasy N, Gupta V, Mayfield M, Trevor-Roberts E. Future orientation. In: House R, Changes P, Javidan M, Dorfman P, Gupta W, editors. Cuture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. pp. 282–342. [Google Scholar]

- Bergadaa MM. The role of time in the action of the consumer. Journal of Consumer Research. 1990;17(3):289–302. [Google Scholar]

- Bond MH. How language variation affects inter-cultural differentiation of values By Hong Kong bilinguals. Journal of Language and Social Psychology. 1983;2(1):57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Boniwell I, Zimbardo PG. Balancing one’s time perspective in pursuit of optimal functioning. In: Linley PA, Joseph S, editors. Positive psychology in practice. Hoboken: Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Börsch-Supan A, Brandt M, Hunkler C, Kneip T, Korbmacher J, Malter F, Schaan B, Stuck S, Zuber S. Data resource profile: The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) International Journal of Epidemiology. 2013;42(4):992–1001. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Börsch-Supan A, Brugiavini A, Jürges H, Mackenbach J, Siegrist J, Weber G, editors. Health, ageing and retirement in Europe: First results from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe. Mannheim: Mannheim Research Institute for the Economics of Aging; 2005. Retrieved ( http://www.share-project.org/uploads/tx_sharepublications/SHARE_FirstResultsBookWave1.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Börsch-Supan A, Jürges H, editors. The Survey of Health, Aging, and Retirement in Europe–Methodology. Mannheim: Mannheim Research Institute for the Economics of Aging; 2005. Retrieved ( http://www.share-project.org/uploads/tx_sharepublications/SHARE_BOOK_METHODOLOGY_Wave1.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Bowerman M, Levinson SC, editors. Language acquisition and conceptual development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd JN, Zimbardo P. Time perspective, health, and risk taking. In: Strathman A, Joireman J, editors. Understanding behavior in the context of time. Mahwah: LEA; 2005. pp. 85–10. [Google Scholar]

- Brannigan GG, Shahon AJ, Schaller JA. Locus of control and time orientation in daydreaming: Implications for therapy. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1992;153(3):359–361. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1992.10753731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray DH. Extent of future time orientation: A cross-ethnic study among New Zealand adolescents. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 1970;40(2):200–208. [Google Scholar]

- Brick MJ, Kalton G. Handling missing data in survey research. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 1996;5(3):215–238. doi: 10.1177/096228029600500302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CM, Segal R. Ethnic differences in temporal orientation and its implications for hypertension management. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1996;37(4):350–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruine de Bruin W, Fischbeck PS, Stiber NA, Fischhoff B. What number is ‘fifty-fifty’?: Redistributing excessive 50% responses in elicited probabilities. Risk Analysis. 2002;22(4):713–723. doi: 10.1111/0272-4332.00063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter EC, McCollough ME, Kim-Spoon J, Corrales C, Blake A. Religious people discount the future less. Evoluation and Human Behavior. 2012;33(3):224–231. [Google Scholar]

- Chen MK. The effect of language on economic behavior: Evidence from savings rates, health behaviors, and retirement assets. American Economic Review. 2013;103(2):690–731. doi: 10.1257/aer.103.2.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colsher PL, Wallace RB. Data quality and age: Health and psychobehavioral correlates of item nonresponse and inconsistent responses. Journal of Gerontoloty: Psychological Sciences. 1989;44:45–52. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.2.p45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delavande A, Manski CF. Probabilistic polling and voting in the 2008 presidential election: Evidence from the American Life Panel. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2010;74(3):433–459. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfq019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominitz J. Earnings expectations, revisions, and realizations. The Review of Economics and Statistics. 1998;80:374–88. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott MN, Edwards C, Angeles J, Hambarsoomians K, Hays RD. Patterns of Unit and Item Nonresponse in the CAHPS® Hospital Survey. Health Services Research. 2005;40(6p2):2096–2119. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferber R. Item nonresponse in a consumer survey. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1966;30:399–415. [Google Scholar]

- Fong M. The nexus of language, communication, and culture. In: Samovar L, Porter R, McDaniel E, Roy C, editors. Intercultural communication: A reader. Cengage Learning; 2012. pp. 271–279. [Google Scholar]

- González A, Zimbardo PG. Time in perspective: A psychology today survey report. Psychology Today. 1985:21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Goodenough WH. Culture, language, and society. McCaleb module in anthropology. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Graham RJ. The role of perception of time in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research. 1981;7(4):335–342. [Google Scholar]