Abstract

Pulse Wave Velocity (PWV) is a surrogate marker of arterial stiffness linked to cardiovascular morbidity. Pulse Wave Imaging (PWI) is a technique developed by our group for imaging the pulse wave propagation in vivo. PWI requires high temporal and spatial resolution which conventional ultrasonic imaging is unable to simultaneously provide. Coherent compounding is known to address this tradeoff and provides full aperture images at high frame rates. This study aims to implement PWI using coherent compounding within a GPU-accelerated framework. The results of the implemented method were validated using a silicone phantom against static testing. Reproducibility of the measured PWVs was tested in the right common carotid of six healthy subjects (n = 6) approximately 10–15 mm before the bifurcation during two cardiac cycles over the course of 1–3 days. Good agreement of the measured PWVs (3.97±1.21m/s, 4.08±1.15m/s, p = 0.74) was found. The effects of frame rate, transmission angle and number of compounded plane waves on PWI performance were investigated in the six healthy volunteers. Performance metrics such as the reproducibility of the PWVs, the coefficient of determination (r2), the SNR of the PWI axial wall velocities (SNRvPWI) and the percentage of lateral positions where the pulse wave appears to arrive at the same time-point indicating inadequacy of the temporal resolution (i.e., Temporal Resolution Misses) were used to evaluate the effect of each parameter. Compounding plane waves transmitted at 1° increments yielded optimal performance, generating significantly higher r2 and SNRvPWI values (p≤0.05). Higher frame rates (≥1667 Hz) produced improvements with significant gains in the r2 coefficient (p≤ 0.05) and significant increase in both r2 and SNRvPWI from single plane wave imaging to 3-plane wave compounding (p≤0.05). Optimal performance was established at 2778 Hz with 3 plane waves and at 1667 Hz with 5 plane waves.

Introduction

At the start of every cardiac cycle, blood is pumped into the circulatory system generating pulse waves that propagate throughout the arterial tree inducing displacements in the walls of arterial vessels [1]. The velocity of these waves, known as pulse wave velocity (PWV), is widely accepted as one of the most robust parameters directly related to arterial stiffness [2], [3]. More specifically, assuming the arteries behave similarm to elastic tubes, the modified Moens-Korteweg equation relates the wave velocity to the Young’s modulus of the artery, a direct index of arterial stiffness, as follows [2]:

| (1) |

where E is the Young’s modulus of the elastic tube wall, h is the wall thickness, ρ is the blood density, R is the inner radius of the tube and v is the Poisson’s ratio (the latter appears in the equation to compensate for the finite thickness of the wall). Furthermore, by shedding the thin wall assumption as well as the vessel circumferential homogeneity assumption, the PWV is also linked to arterial compliance (C) via the Bramwell-Hill equation:

| (2) |

where ρ is the blood density, with A being the arterial cross-section luminal area and P the arterial blood pressure within the vessel [4].

PWV measurements can be made noninvasively and have been shown to be highly reproducible [3] while providing a surrogate measure of arterial stiffness, with strong associations to cardiovascular morbidity [5], [6] atherosclerotic vascular burden [7] and target organ damage in the arterial circulation, especially among hypertensive patients [8], [9]. Furthermore, PWV has been recently shown to be a predictor of subclinical impairments in both cardiac and renal function, thus demonstrating its potential in early diagnosis and treatment [10].

Furthermore, focal vascular diseases such as atherosclerosis and abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) are known to affect the mechanical properties of tissues [2], [7], [11]. However, the PWV estimates in most clinical studies on arterial stiffness are based on the carotid-femoral method [6], [12], [13] and thus suffer from poor spatial resolution. Consequently, investigation of the local mechanical properties of pathological tissue is not possible with the aforementioned techniques. In order to address this issue, our group has developed Pulse Wave Imaging (PWI), an ultrasound-based noninvasive technique that provides estimates of the regional PWV with the accompanying r2 measurement quality indicator [14], [15]. This technique has recently been extended into piecewise PWI (pPWI) to achieve better resolution, on the scale of a few millimeters of arterial vessel length [16]. One of the main advantages of PWI compared to other MRI- and ultrasound-based techniques that have been developed to provide regional PWV estimates [17], [18], [19], [20], is that it visualizes the propagation of the pulse wave at extremely high temporal and spatial resolutions. Consequently, various features of the propagation can be characterized and used to diagnose vascular disease [21]. Additionally, estimating the PWVs within small sections of the imaged artery allows spatial maps of PWV and PWI modulus maps, which represent a relative metric of stiffness and can be used to detect and monitor atherosclerosis and AAAs [16].

From the previous description, it becomes apparent that PWI requires imaging at high frame rates coupled with high spatial resolution. More specifically, it has been reported that PWV estimation requires frame rates in the kilohertz range [19]. However, achieving such high frame rates may present a challenge, especially when using conventional focused imaging, where a focused beam is swept across the imaging plane and backscattered signals are sequentially acquired. In order to address this issue, stroboscopic techniques based on ECG-gating that reconstruct image sequences by using images from different cardiac cycles have been previously reported [16], [22] as well as exploiting the tradeoff between scan line density and frame rate on conventional scanners. In particular, this tradeoff is a significant one and has been experimentally evaluated [23]. Plane wave imaging [24]–[26] has been proposed to achieve ultrafast frame rates (i.e. more than 1 kHz). Its paradigm consists of using a single plane wave to insonify the full imaging plane [24]. Theoretically, the frame rate is only limited by the speed of sound and the attenuation of the sound waves in tissues and can thus reach levels above 10 kHz. However, it should be noted that there are practical restrictions imposed to the frame rate by the hardware data transfer rate and memory specifications.

The main drawback of plane wave imaging is the decreased image quality due to the lack of a transmit focus. This issue has been resolved, however, with the development of coherent compounding [27]. Steered plane waves are being transmitted into the medium followed by the acquisition and coherent summation of the backscattered echoes. This technique leads to higher image signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), decreased sidelobe levels and overall better image quality [27] and has been shown to augment various elastographic ([27], [28], [26]) as well as blood flow imaging techniques ([29], [30]). However, increasing the number of transmitted plane waves comes at the cost of frame rate, thus introducing a tradeoff between image quality and frame rate, which is regulated by the number of transmitted plane waves.

In the current study, PWI is implemented using plane wave imaging. A post-processing methodology for handling the increased amount of data generated by the proposed method is described, including GPU-accelerated functions for beamforming and motion estimation. The results are validated using a silicone phantom and reproducibility is verified in vivo. The performances of PWI and pPWI are assessed and optimized in vivo by investigating the effects of independently varying parameters affecting image quality (number of transmitted plane waves, plane wave transmission angle) and the frame rate. In order to quantify the effects of the aforementioned parameters, a variety of metrics is utilized. To our knowledge, this is the first study that optimizes coherent compounding parameters in vivo to effectively image the pulse wave propagation.

Materials and Methods

The present study was organized into three main parts. Firstly, feasibility of PWI and pPWI was demonstrated in a silicone phantom with validation through independent static testing. Secondly, the feasibility of PWI and pPWI was demonstrated in healthy subjects and reproducibility of the results between different acquisitions of the same subject was shown. Finally, in order to detect the optimal imaging parameters in vivo, an optimization study was performed utilizing data from six healthy volunteers.

Phantom Study Design

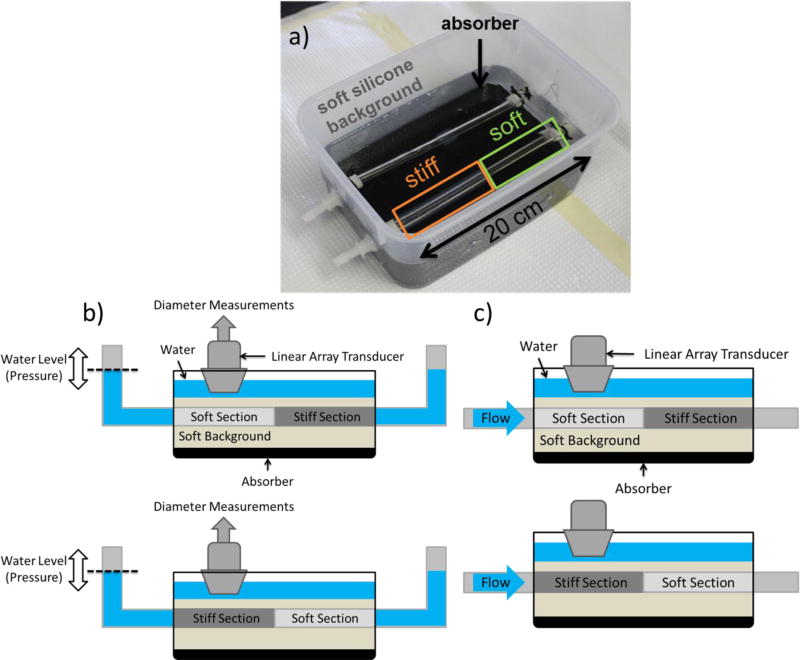

Silicone gel was used to construct a phantom with a soft and a stiff segment along the longitudinal axis [31]. A 240-mm concentric cylindrical mold comprised of a 12.5-mm internal diameter acrylic tube and an 8-mm outside diameter acrylic rod was lightly coated with petroleum jelly to allow the phantom to be extracted. For the soft segment of the phantom 100% A341 silicone soft gel (Factor II, Lakeside AZ) was used and for the stiff segment the mixture was 70% A341 and 30% LSR-05 silicone elastomer (Factor II, Lakeside AZ). 2% by weight silica powder was included as an ultrasound contrast agent. After mixing, 5 minutes of vacuum degassing prevented formation of air bubbles. The mold was held vertically and layers of soft or stiff material were introduced using a syringe and tube to avoid coating the portion of the mold used for subsequent layers with thin layers of silicone. Subsequent layers were poured after about an hour of curing time, and they naturally adhered strongly to each other. The phantom was carefully extracted from the mold using extra petroleum jelly, and then mounted on fittings in a plastic container. A very soft silicone background was constructed from 40% A341 gel and 60% Xiameter PMX-200 100CS silicone fluid (Dow Corning, Midland MI). No silica powder was included in the background because ultrasound speckle is not required outside of the vessel phantom. The vessel phantom was first filled with water to maintain a circular profile and avoid floating while the background material was filled to approximately 15mm above the top surface of the vessel phantom. The finalized phantom setup is shown in Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

a) Image of the phantom setup used in the present study, b) schematic of the static testing setup and c) schematic of the scanning location at each phantom section (Top: soft section, Bottom: stiff section).

Subsequently, two rubber tubes were attached to the outlets of the phantom and its free ends were fixed approximately 7–8cm above the top surface of it. Static testing was performed similarly to the mechanical testing performed in [32]. More specifically, the system was progressively filled with water and the water level in the tubes was measured at specific time points. The water level measurements provided intraluminal pressure estimates while simultaneously acquired ultrasonic images with a clinical scanner using a 10-MHz linear array (SonixTouch, Ultrasonix Medical Corp., Burnaby, BC, Canada) provided diameter measurements which were then used to estimate intraluminal area. Consequently, specific points of the pressure area relationship of the phantom vessel were recovered and used to provide a compliance estimate. The Bramwell-Hill equation (equation 2) was then employed to produce an expected PWV value. A schematic of the static testing setup of the phantom at each section is shown in Fig. 1b). An advantage of static testing over other mechanical testing methodologies is that since it doesn’t require extracting the phantom, it takes into account conditions that influence stiffness such as the geometry of the phantom, the pre-stretch and the influence of the surrounding medium.

Following static testing, the phantom was connected via rubber tubes to a peristaltic pump, which generated negative pulse waves by pressing and then releasing the rubber tubes at rate of approximately 2 Hz. A static circumferential pre-strain was produced by raising the height of the pump outlet reservoir to 50mm above the phantom. The approximate scanning location at each phantom section is shown in Fig. 1c). It should be noted that care was taken when connecting the phantom to the peristaltic pump so that the imaged location would be as far as possible from the fixed end of the phantom along the wave propagation direction. This was done to ensure sufficient travel time for the forward wave without getting mixed with the reflection wave generated at the fixed end of the phantom.

In vivo Study Design

Custom plane wave acquisitions were performed on the right common carotid arteries of six healthy volunteers (age range 22–32 y.o.). Care was taken so that the common carotid was imaged at least 1cm away from the bifurcation, to avoid mixing of the forward and the reflected pulse wave. Some of the acquisitions were repeated after 1–3 days in order to investigate the repeatability of the acquired PWV values. All images were acquired while the subjects were in a sitting position and care was taken to perform the repeated measurements at a similar time of the day to avoid PWV variations due to the circadian rhythm of the subjects.

Data Acquisition

In order to perform the acquisitions and assess the performance of compounded PWI, a programmable ultrasound research scanner (Verasonics Vantage 256, Kirkland, WA, USA) was used. All acquisitions were made using a standard 128-element, 5 MHz linear array transducer with 50% bandwidth and 298 µm element spacing (L7-4, ATL Ultrasound, Bothell, WA).

The phantom was scanned using a standard 5-plane wave sequence at a frame rate of 926 Hz. The plane wave steering angles were evenly spaced between −4° to 4°. In order to investigate whether coherent compounding produced an improvement over single plane wave imaging, the results of using 1, 3 and all 5 of the plane waves were compared.

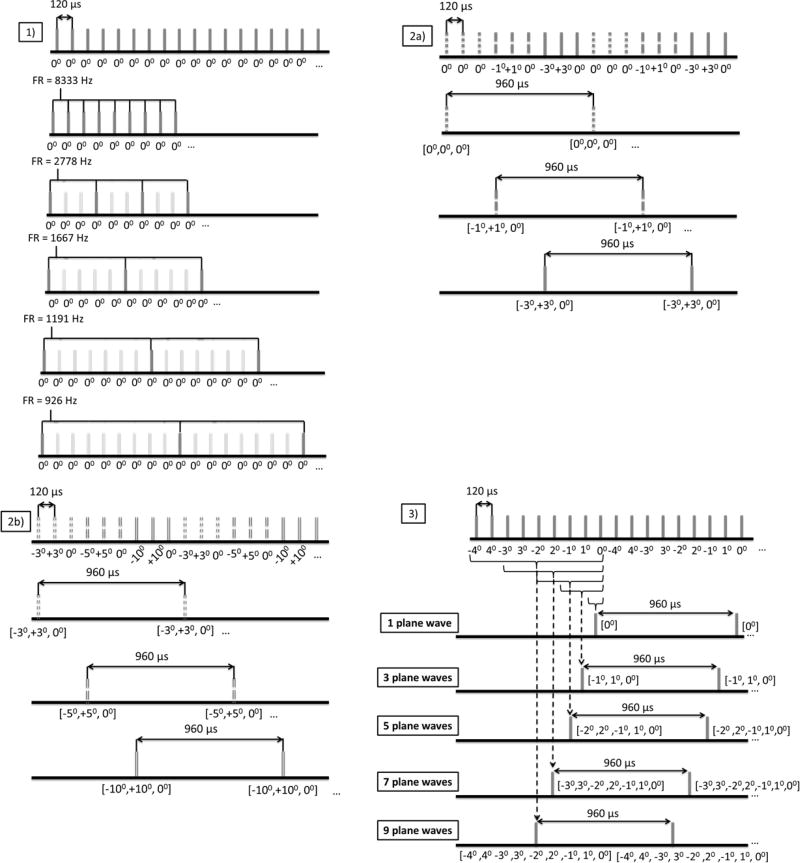

In the case of the in vivo study, three custom acquisition sequences (Fig. 2) were implemented to independently optimize the three compounding parameters. In all of the cases, the pulse repetition frequency (PRF) was set equal to 8333 Hz. This PRF value was sufficient to accommodate both the time needed for the sound waves to make the required round trip and also the transfer rate between the acquisition system and the host workstation.

Frame rate: An acquisition sequence transmitting plane waves at the PRF was initially implemented to assess the effects of frame rate on the performance of PWI. The frame rate was decimated at post-processing in order to simulate the frame rate drop caused by adding more steered plane waves. Specifically, by considering all of the frames, a frame rate equal to the PRF was achieved while the frame rate decreased to 2778 Hz, 1667 Hz, 1190 Hz and 926 Hz after maintaining one frame every 3, 5, 7 and 9 frames respectively. A schematic of this sequence is depicted in Fig. 2(1).

Plane Wave Transmission Angle: The effects of changing the plane wave transmission angles were investigated using a sequence that transmits nine plane waves at the PRF. The transmission angle strategy consisted of considering the nine plane waves as three sequential triplets transmitted at angles [−a, a, 0] with different angle a for each of the three triplets. Alternate polarity sequencing was utilized to avoid lateral shifts of the moving target observed otherwise [33]. Subsequently, the acquired RF signals from each triplet were compounded resulting in three 3-plane wave compounding image sequences at a frame rate of 926 Hz with different transmission angles of the tilted plane waves. Thus performance assessment of three different transmission angle values was made possible. This sequence was employed twice in order to compare the following transmission angles: 0°, 1°, 3° and 3°, 5°, 10°. Schematics of the two implemented sequences are shown in Figs. 2(2a) and 2(2b). It should be noted that in the case of 0° compounding practically corresponds to RF image averaging. Additionally, 3° was used in both acquisitions and served as a baseline to facilitate comparison between results from different acquisitions.

Number of Compounded Plane Waves: A 9-plane wave compounding sequence was implemented. Alternate polarity [−4°, 4°, −3°, 3°, −2°, 2°, −1°, 1°, 0°] was utilized again in order to avoid lateral shifts of the moving targets. Subsequently, the following subsets of the plane wave acquisitions were used to create compounded images: [0°], [−1°, 1°, 0°], [−2°, 2°, −1°, 1°, 0°], [−3°, 3°, −2°, 2°, −1°, 1°, 0°] and [−4°, 4°, −3°, 3°, −2°, 2°, −1°, 1°, 0°] and thus utilizing 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9 plane wave acquisitions respectively. A schematic depicting the implemented sequence is shown in Fig. 2(3).

Figure 2.

Custom acquisition sequences for independent assessment of each imaging parameter. 1) Acquisition sequence for frame rate optimization. 2) a) b) Acquisition sequences for the optimization of the angle of the steered plane waves 2a) is used to investigate angles 0°, 1° and 3° and 2b) is used to investigate angles 3° (repeated for comparison baseline purposes), 5° and 10°, 3) acquisition sequence for the optimization of the number of plane waves used in coherent compounding.

Each of the aforementioned acquisitions lasted for 1.2 seconds generating approximately 2.5 GB of data. Finally, it has to be noted that in both the phantom and the healthy subject cases care was taken so that the flow and the direction of pulse wave propagation was from the left toward the right side of the image.

Parallel beamforming

Beamforming was applied to the acquired channel data to produce full RF frame sequences. The beamforming employed in this study was a parallel pixel-wise implementation of the delay-and-sum method presented in [27]. More specifically, for each point of the resulting image the contributions of each element were determined and then coherently summed. This coherent summation was achieved by delaying the received channel data for each point by the total travelling time to from each element to that point and back. More specifically, if the x direction is considered parallel to the transducer’s element array and the z direction is considered to be along the depth of the image (perpendicular to the transducer’s surface), for a plane wave sent into a medium at an angle (a), the time to travel from the element (xel, 0) to a point (x,z) in the medium (tforward) is equal to:

where c is the average speed of sound in tissue (c = 1540 m/s). Additionally, the time for the echo to return to the element (tbackward) is equal to:

thus yielding the total travel time (ttotal) as follows:

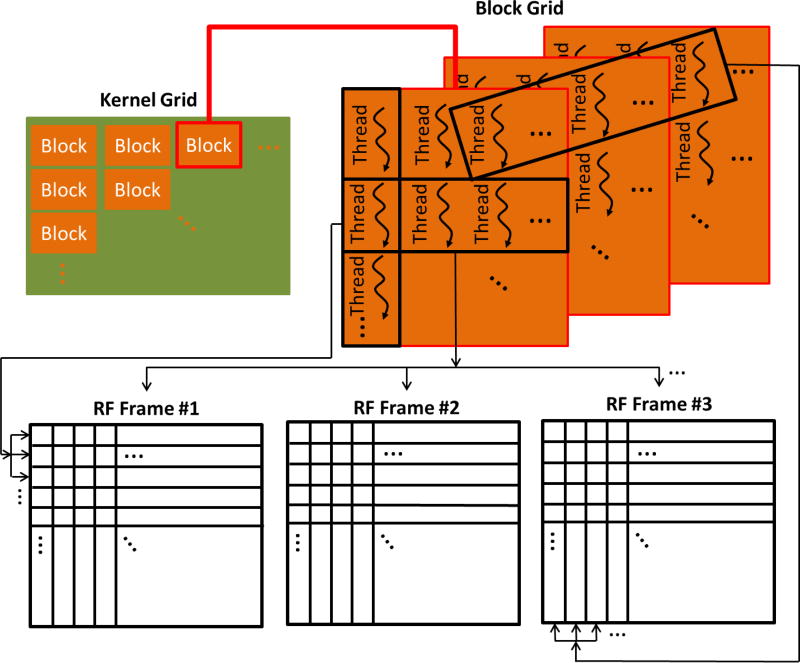

Given the significant performance gains achieved by utilizing graphic processing units (GPUs) as well as the faster execution time of compiled C code compared to interpreted MATLAB code the beamforming algorithm was implemented on the CUDA computing platform (CUDA 6.5, NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, California, U.S.) using the C programming language. A 2-D kernel grid was generated where each block was organized as a 3-D array of threads. Each thread in each block is uniquely characterized by three integers (threadId.x, threadId.y, threadId.z). According to the implemented algorithm threads with different threadId.y estimate and accumulate the contributions of elements at different samples of each beamformed RF-frame, while threads with different threadId.x act on different RF-frames. Finally, threads with different threadId.z act on different lines of the beamformed RF-frame. A schematic diagram indicating the allocation of threads in the parallel formation of the RF frames is shown in Fig. 3. Theoretically, creating a sufficient number of blocks and threads results to each thread working towards beamforming a specific pixel of a specific RF-frame, thus completely parallelizing the beamforming process. However, due to hardware limitations in the total number of threads that can be created, some of the threads are reused in multiple pixels, thus achieving partial parallelization of the process. In the beamforming process the f number was 1.7 and apodization was implemented on receive using a Hanning filter.

Figure 3.

Schematic depicting CUDA thread allocation in the parallel creation of the RF image sequence.

The program was executed using a Tesla C2075 GPU and on average it produced 1000 RF-frames with 2160 samples and 128 lines within approximately 30 seconds. Subsequently, the produced RF-frames were coherently summed to produce compounded RF-frames.

GPU-accelerated sub-sample displacement estimation algorithm

The axial wall velocities (vPWI) were estimated off-line from the produced RF-frames. In order to account for the increased size of the input data, this study introduces a sub-sample GPU-based 1-D normalized cross-correlation (NCC) algorithm, essentially parallelizing the sum-table method introduced in [34]. A detailed description of the implemented algorithm is given in Appendix A.

It should be noted that an assumption made in the current implementation to reduce the memory requirements was that the arterial wall displacements were sub-sample. This hypothesis was repeatedly tested and validated among healthy subjects who normally show the highest arterial displacements. Subsequently, the axial wall displacements were multiplied by the frame rate to obtain the vPWI.

The algorithm was implemented using MATLAB supported methods that apply functions to each element of GPU arrays and on average it produced 1000 vPWI frames in 35 seconds. The window size was approximately 7 times the wavelength and the window shift was set to 1 sample (~99% overlap).

In order to visualize the estimated vPWI and essentially the pulse wave propagation, the contours of both the anterior and the posterior arterial walls were manually outlined and subsequently used to generate moving masks according to the estimated vPWI that track the motion of each wall during a single cardiac cycle. Within the aforementioned moving masks the vPWI were color-coded (red color indicating motion towards and blue color indicating motion away from the transducer) and overlaid onto the B-mode image thus creating sequences of PWI vPWI images.

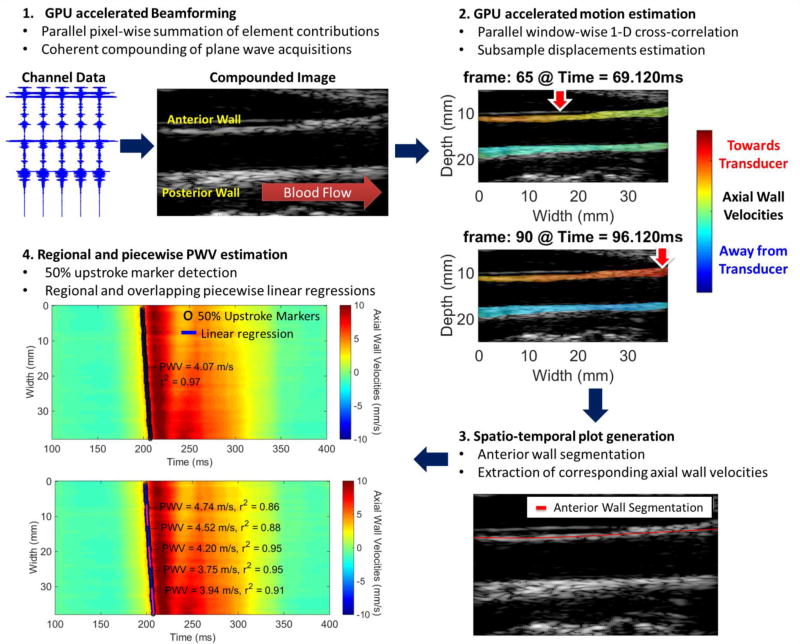

PWV and pPWV estimation

A schematic of the complete post-processing pipeline utilized in the current study is given in Fig. 4. After the generation of the compounded RF sequence, the estimation of the vPWI and generation of sequences of PWI vPWI images, a single line was manually traced through the anterior carotid wall and the vPWI waveforms at each point of the arterial wall trace were sequentially stacked generating a 2-D spatio-temporal plot that depicts the vPWI variation over distance and time of the pulse-wave propagation. Distance along the anterior arterial wall trace was calculated by estimating the length of the delineated carotid wall between each point and the leftmost point of the arterial wall trace. It should be noted that this segmentation of the anterior arterial wall for the purpose of generating the 2-D spatio-temporal plot is not related to the outlining of the anterior and posterior arterial walls used to produce PWI vPWI images.

Figure 4.

Schematic of the compounding PWI post-processing methodology. In 2 vertical red arrows with the white contour indicate the approximate location where the vPWI obtain values close to their 50% downstroke point, thus indicating the pulse wave propagation.

On the 2-D spatio-temporal images, the 50% upstroke point of the vPWI versus time was selected as the tracking feature to estimate the PWV. The 50% upstroke was defined as the time-point, at which vPWI was closest in value to the average between the foot and the peak of the vPWI at each beam location. The choice of this tracking feature is justified because the early wavefront is less affected by the generated reflected waves [2] and also because previous studies have shown that it is the most robust compared to alternative tracking features (foot, 25% upstroke, 75% upstroke) [23]. In the case of the phantom, the initial pulse wave corresponds to a drop in pressure so the 50% downstroke was used as the tracking feature and was defined as the average between the foot and the negative peak of the vPWI. Linear regression of the relationship between the 50% upstroke arrival time and the previously calculated distance along the anterior wall yielded the slope as the regional PWV value for the whole imaged segment and the corresponding coefficient of determination r2 as an approximate measure of the pulse wave propagation uniformity.

Subsequently, the localized pPWV measurements were estimated similarly to [16] where the 50% upstroke points were divided in 50% overlapping kernels of 20, 30, 40 and 50 points. Linear regressions were performed for each sub-region, thereby providing a localized PWV value along with the corresponding coefficient of determination r2, indicative of the quality of the linear fit. The size of the kernels was varied to investigate the effects of frame rate and compounding on various levels of PWV localization.

Performance Metrics

In order to assess the accuracy of the PWI measurements and evaluate the effect of each parameter on the quality of its results, various metrics were used.

Regional and piecewise PWV values: Comparison to static testing derived values in the case of the phantom and evaluation of repeatability and agreement between regional and mean piecewise PWVs in the case of the healthy volunteers.

Coefficient of determination (r2): Comparison of r2 values for different parameter configurations provides a quality metric contingent upon both varying image SNR as well as frame rate [23].

- PWI Axial Wall Velocities SNR (SNRvPWI): Similarly to [35], a stochastic metric of precision was used to compare the performance of vPWI estimation for various imaging configurations. Firstly, the anterior wall of the vessels was manually segmented and subsequently the frames corresponding to a period of 100 ms around the time-point of occurrence of the pulse wave propagation were isolated. SNRvPWI was estimated for each point of the anterior wall within small 2D windows (1mm × 1.2mm). The SNRvPWI and vPWI data were used to generate a 2D histogram that corresponds to the probability density function of SNRvPWI for each of the observed vPWI magnitudes. Finally, to facilitate comparison the expected value of SNRvPWI was estimated for each vPWI value as follows:

thus generating easily comparable curves between different imaging sequences. Finally, the mean SNRvPWI was estimated by averaging the estimated SNRvPWI for all the points of the anterior wall. - Temporal Resolution Misses (TRM): This metric was used to evaluate the frame rate’s capability to adequately sample the propagation of the pulse wave. More specifically, TRM were estimated as a percentage of the consecutive 50% upstroke markers that occur at the same time point over the total number of 50% upstroke markers. Thus:

Consequently, higher values of this metric correspond to an insufficient frame rate to capture the pulse wave propagation.

Given that the measurements were performed in the same group of 6 healthy subjects repeated measures ANOVA was selected as the designated statistical test and multiple comparisons were carried out using the Tukey correction within the results of each acquisition sequence. Finally, the errors indicate standard deviation.

Results

Phantom validation study

The recovered mean compliances using static testing in the case of the soft and the stiff sections were Csoft = 9.62 · 10−9m2/Pa and Cstiff = 5.11 · 10−9 m2/Pa. The area used in equation (2) denoted the mean cross-section luminal area estimated throughout the PWI experiments (A = 5.94 · 10−5 m2) and the density was set to ρ = 1000 kg/m3. Thus, from equation (2), the recovered static testing PWV values for the soft and the stiff phantom sections were PWVsoft = 2.49 m/s and PWVstiff = 3.41 m/s.

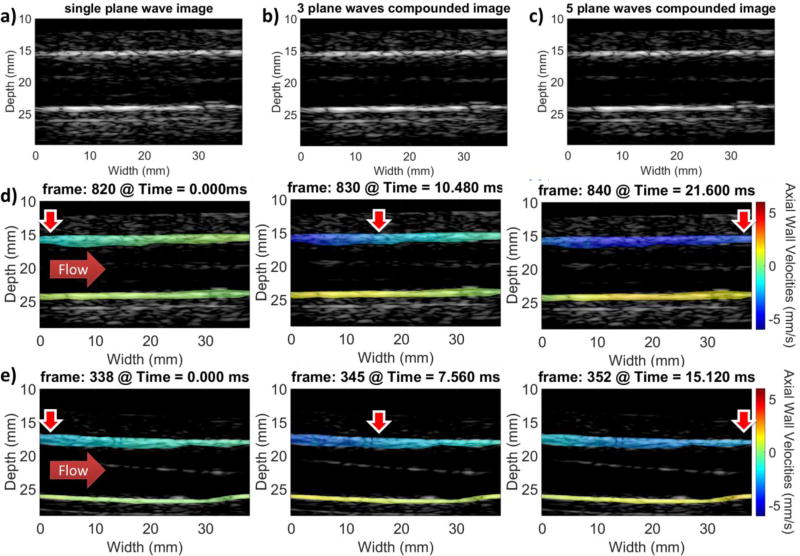

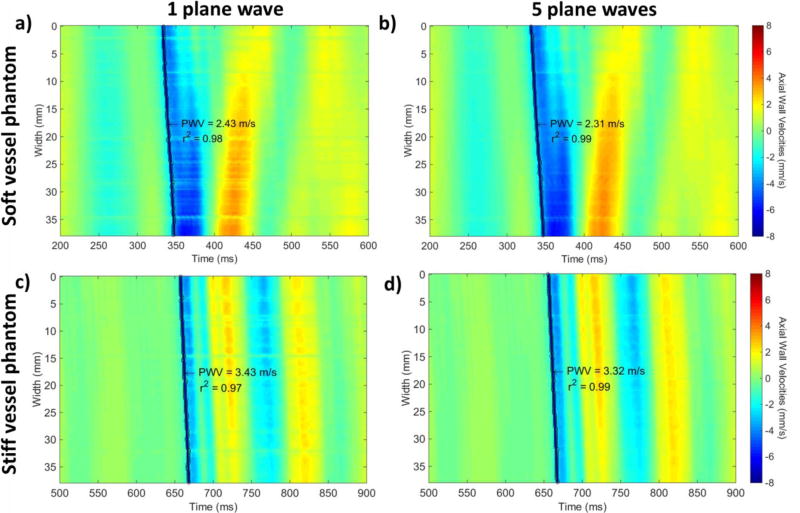

In the case of the PWI experiments, the stiff and soft parts of the phantom were imaged using 1, 3 and 5 plane waves. The resulting B-modes for the cases of 1, 3 and 5 plane waves as well as sequences of PWI images indicating the pulse wave propagation in the soft and stiff sections of the phantom are shown in Fig. 5. Subsequently, Fig. 6 shows the resulting spatio-temporal plots using 1 (Figs. 6a and 6c) and 5 plane waves (Figs. 6b and 6d) in the case of the soft (Figs. 6a and 6b) and stiff (Figs. 6c and 6d) phantom sections. Higher PWVs and overall lower magnitude vPWI were measured in the case of the stiff phantom section.

Figure 5.

a) Single plane wave B-mode of the phantom. b) 3 plane wave compounded B-mode image at the same location of the vessel phantom. c) 5 plane wave compounded B-mode image at the same location of the vessel phantom d) PWI vPWI image sequence at the soft section of the phantom. e) PWI vPWI image sequence at the stiff section of the phantom generated with the 5 plane wave compounding sequence. Red corresponds to motion towards the transducer and blue corresponds to motion away from it. Horizontal solid red arrows indicate flow direction and vertical red arrows with the white contour indicate the approximate location where the vPWI obtain values close to their 50% downstroke point, thus indicating the pulse wave propagation.

Figure 6.

Spatio-temporal plots generated using a) single plane wave imaging, b) 5 plane wave coherent compounding in the case of the soft phantom section, c) single plane wave imaging, and d) 5 plane wave coherent compounding in the case of the stiff phantom section. Red corresponds to motion towards the transducer and blue corresponds to motion away from it.

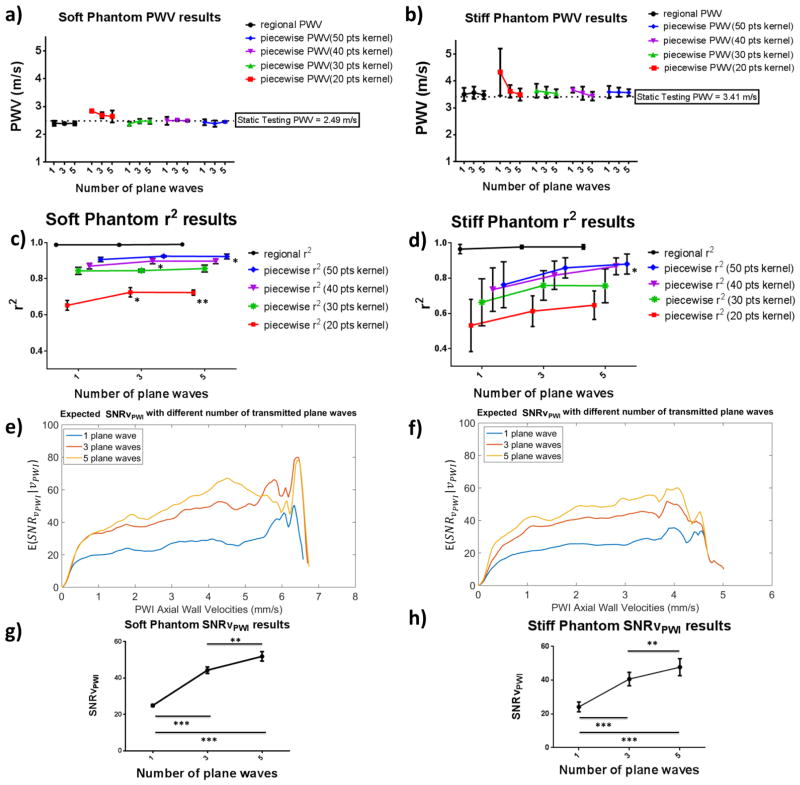

Fig. 7 shows the statistical results from analyzing four different cycles (N= 4) for each of the phantom’s soft and stiff sections. Good agreement was found between the PWVs measured using the whole imaged phantom section (regional PWV) and the piecewise PWVs with various kernel sizes. Good agreement was also found between the PWI-measured PWVs and the static testing PWVs in both phantom sections. Figs. 7c and 7d show the resulting regional and piecewise r2 values. In the case of the soft phantom section significant increases were observed for 20-point kernels between measurements made using 1 plane wave and 3 and 5 plane waves (p≤0.05 and p≤0.01 respectively) as well as in the case of 40-point kernels between measurements made using 1 and 3 plane waves (p≤0.05) and finally in the case of 50-point kernels between 1 and 5 plane waves (p≤0.05). Meanwhile, in the case of the stiff phantom section, increased variability of the r2 values was found and significance was only observed in the case of 50-point kernels between acquisitions using 1 and 5 plane waves (p≤0.05). Figs. 7e and 7f illustrate the expected SNRvPWI curves for 1, 3 and 5 plane waves. There was a significant improvement in the SNRvPWI as the number of plane waves increased from 1 to 3 and subsequently to 5 plane waves. Moreover, a less pronounced increase in the SNRvPWI was found from 3 to 5 plane waves. Similarly, in Figs. 7g and 7h, the mean SNRvPWI in both phantom sections underwent significant increase from both 1 to 3 plane (p≤0.005) waves as well as from 3 to 5 plane waves (p≤0.01). It should be noted that in the case of 5 plane waves the average SNRvPWI values reached ideal case values (51.84±2.56 for the soft phantom section and 47.72±5.05 for the stiff phantom section).

Figure 7.

Statistical analysis of the phantom PWI validation study. a) and b): regional and piecewise PWVs for different numbers of transmitted plane waves in the cases of the soft and stiff phantom sections respectively. c) and d): regional and piecewise r2 values for different numbers of transmitted plane waves in the cases of the soft and the stiff phantom sections respectively. The asterisks indicate significant difference compared to the single plane wave case. e) and f): expected SNRvPWI curves for different numbers of transmitted plane waves. In the cases of the soft and the stiff phantom sections respectively g) and h) show mean SNRvPWI for different number of transmitted plane waves in the cases of the soft and stiff phantom sections respectively. Asterisks indicate significant difference and the horizontal lines indicate the groups between which the corresponding level of significance was found (* : p≤0.05, ** : p≤0.01, *** : p≤0.001).

In vivo reproducibility study

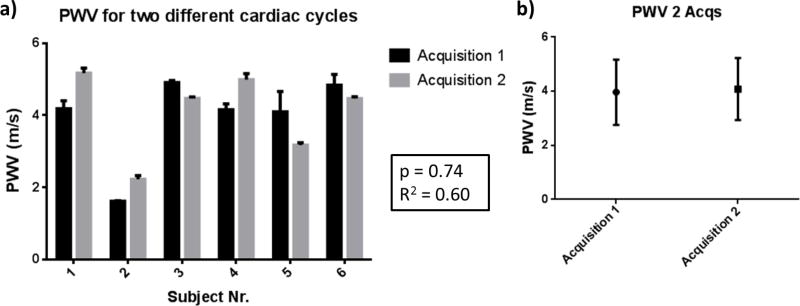

Six healthy subjects (n = 6) were scanned twice over the course of 1–3 days. Each measurement was made using the custom plane wave transmission angle imaging sequence shown in Fig. 2(2a). Thus, three measurements of the PWV of the same cardiac cycle were made with different transmission angles. Fig. 8a shows the average measured regional PWVs of the different cardiac cycles for each subject. Relatively good agreement was found between the PWVs measured for the same subject during different cardiac cycles. Furthermore, Fig. 8b shows the mean PWVs for all the investigated subjects during both acquisitions. Good agreement can be observed between the estimated PWV values (3.97±1.21 m/s for the first acquisition and 4.08±1.15 m/s for the second acquisition, p = 0.74, R2 = 0.6). The complete list of measured PWVs can be seen in Table I.

Figure 8.

a) PWVs of six (n=6) healthy subjects measured over two different cardiac cycle acquisitions over the course of 1–3 days. b) Mean PWVs of all subjects during the first and the second acquisition. The corresponding p-value from using paired t-test and the coefficient of determination R2 are shown in the middle.

Table I.

mean regional PWVs and corresponding standard deviations for 3 measurements of two cardiac cycle acquisitions over the course of 1–3 days for each healthy subject. Last row presents the inter-subject mean regional PWVs and the corresponding standard deviations for the 6 subjects

| Subject | PWV Acquisition 1 (Mean ± STD m/s) | PWV Acquisition 2 (Mean ± STD m/s) |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | 4.18±0.22 | 5.17±0.14 |

| S2 | 1.61±0.02 | 2.22±0.11 |

| S3 | 4.91±0.06 | 4.47±0.04 |

| S4 | 4.15±0.16 | 4.99±0.17 |

| S5 | 4.10±0.57 | 3.17±0.07 |

| S6 | 4.84±0.30 | 4.46±0.06 |

| Mean | 3.97±1.21 | 4.08±1.15 |

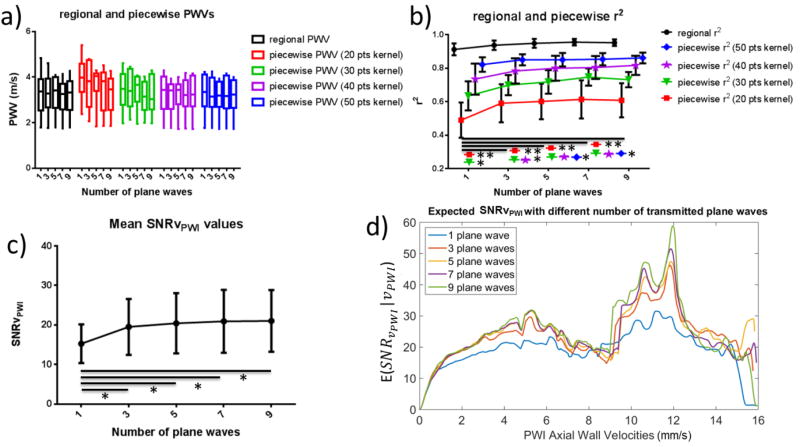

In vivo optimization study

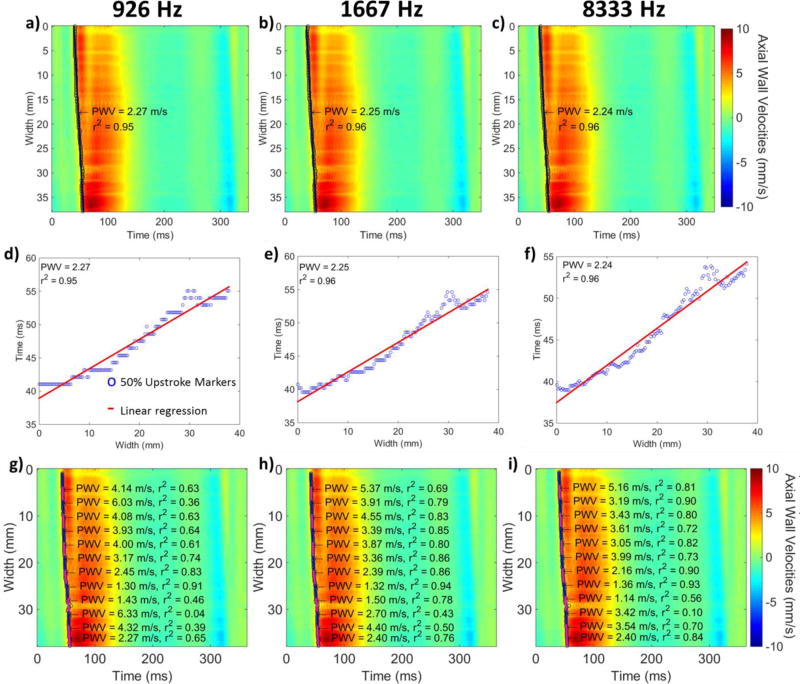

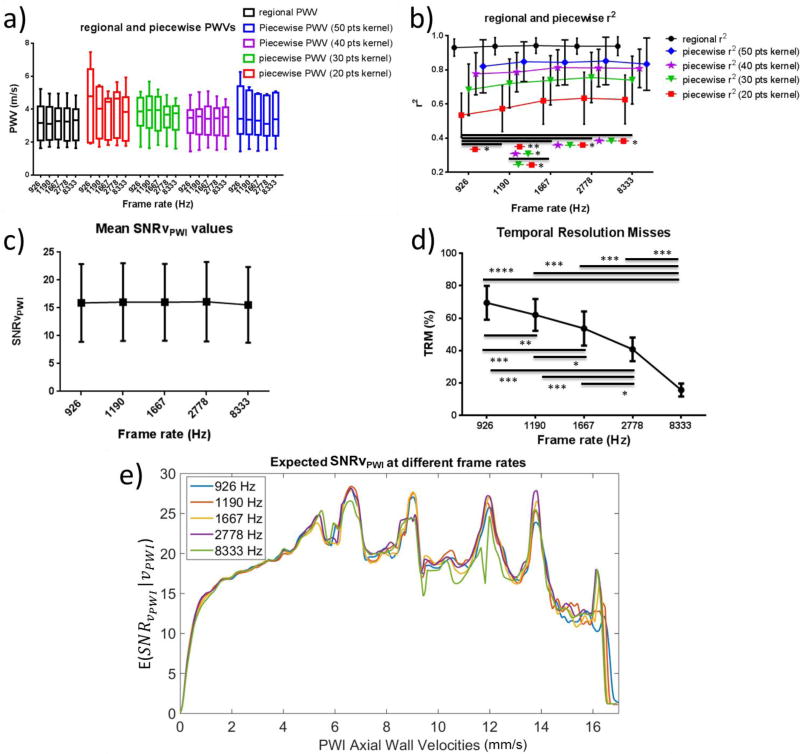

Table II provides a summary of the effects of different values of each imaging parameter on the regional and piecewise r2 as well as on the mean SNRvPWI and the TRMs. Fig. 9 shows spatio-temporal plots produced for the same subject at different frame rates. No noticeable change in quality can be observed. However, as seen in Figs. 9d, 9e and 9f, the layout of the 50% upstroke marker is changing. Fig. 10 shows the statistical analysis of PWI results at different frame rates. In Fig. 10a good agreement of the PWV values can be observed. In Fig. 10b the regional and piecewise r2 are plotted against different frame rates. As the frame rate increases, there is an increase in the r2 values. More specifically, in the case of 20-and 30-point kernels, there is a significant increase in the mean r2 as frame rate increases from 926 Hz to 1667 Hz (p≤0.01 and p≤0.05 respectively) as well as from 1190 Hz to 1667 Hz (p≤0.05 for both cases), from 926 Hz to 2778 Hz (p≤0.05 for both cases) and from 926 Hz to 8333 Hz (p≤0.05 for both cases). In the case of 20-point kernels significance was also found as the frame rate increased from 926 Hz to 1190 Hz (p≤0.05). In the case of 40-point kernels significance was only found between 926 Hz and 1667 Hz, 926 Hz and 2778 Hz as well as 926 Hz and 8333 Hz (p≤0.05). Finally, in the case of the largest kernel size (50 points) as well as in the case of regional r2 no significance was found.

Table II.

Summary of the effects of each imaging parameter to the performance metrics investigated in the in vivo optimization study. Each symbol indicates comparison between the performance metric values at the current and the immediately preceding imaging parameter value.

| Frame Rate Influence | Frame Rate | 926 Hz | 1190 Hz | 1667 Hz | 2778 Hz | 8333 Hz | |

| Regional r2 | I.V. | Ø | |||||

| 20 pts piecewise r2 | I.V. | ++ | ++ | Ø | |||

| 30 pts piecewise r2 | I.V. | Ø | ++ | Ø | |||

| 40 pts piecewise r2 | I.V. | ++ | Ø | ||||

| 50 pts piecewise r2 | I.V. | + | Ø | ||||

| Mean SNRvPWI | I.V. | Ø | − | ||||

| TRMs | I.V. | −−− | −− | −− | −−−− | ||

| Transmission Angles Influence | Transmission Angles | 0° | 1° | 3° | 3°(2) | 5° | 10° |

| Regional r2 | I.V. | ++ | Ø | RV | Ø | ||

| 20 pts piecewise r2 | I.V. | + | − | RV | − | Ø | |

| 30 pts piecewise r2 | I.V. | ++ | − | RV | − | − | |

| 40 pts piecewise r2 | I.V. | ++ | Ø | RV | −− | + | |

| 50 pts piecewise r2 | I.V. | + | Ø | RV | Ø | ||

| Mean SNRvPWI | I.V. | +++ | −− | RV | − | −− | |

| Number of Plane Waves | Number of Plane Waves | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | |

| Regional r2 | I.V. | + | + | Ø | |||

| 20 pts piecewise r2 | I.V. | +++ | + | Ø | |||

| 30 pts piecewise r2 | I.V. | ++ | + | Ø | |||

| 40 pts piecewise r2 | I.V. | ++ | Ø | + | |||

| 50 pts piecewise r2 | I.V. | ++ | Ø | ||||

| Mean SNRvPWI | I.V. | ++ | Ø | ||||

I.V.: initial value, +: non-significant increase, ++: significant increase (p≤0.05), +++: significant increase (p≤0.01), ++++: significant increase (p≤0.005), −: non-significant decrease, −−: significant decrease (p≤0.05), −−−: significant decrease (p≤0.01), −−−−: significant decrease (p≤0.005), Ø: no change

Figure 9.

a), b) c) Spatio-temporal plots and regional PWVs of a healthy subject corresponding to frame rates of 926 Hz, 1667 Hz and 8333 Hz respectively. d), e), f): 50% upstroke markers and regional linear fit determining the regional PWV corresponding to frame rates of 926 Hz, 1667 Hz and 8333 Hz respectively. g), h), i): Spatio-temporal plots and 20 point kernel piecewise PWVs corresponding to frame rates of 926 Hz, 1667 Hz and 8333 Hz respectively

Figure 10.

Statistical analysis of the in vivo frame rate variation results. a) regional and piecewise PWVs for different frame rates b) regional and piecewise r2 values for different frame rates c) mean SNRvPWI for different frame rates d) temporal resolution misses (TRMs) for different frame rates e) expected SNRvPWI curves for different frame rates. Asterisks indicate significant difference and the horizontal lines indicate the groups between which the corresponding level of significance was found (* : p≤0.05, ** : p≤0.01, *** : p≤0.001).

Fig. 10c shows the mean SNRvPWI values at each frame rate. No significant change occurs as the frame rate increases, except for a small dip occurring at the highest frame rate (8333 Hz). This can also be seen in Fig. 10e which shows the expected SNRvPWI curves. Finally, Fig. 10d shows the TRMs at each frame rate. Significant increases can be observed at each transition as the frame rate decreases.

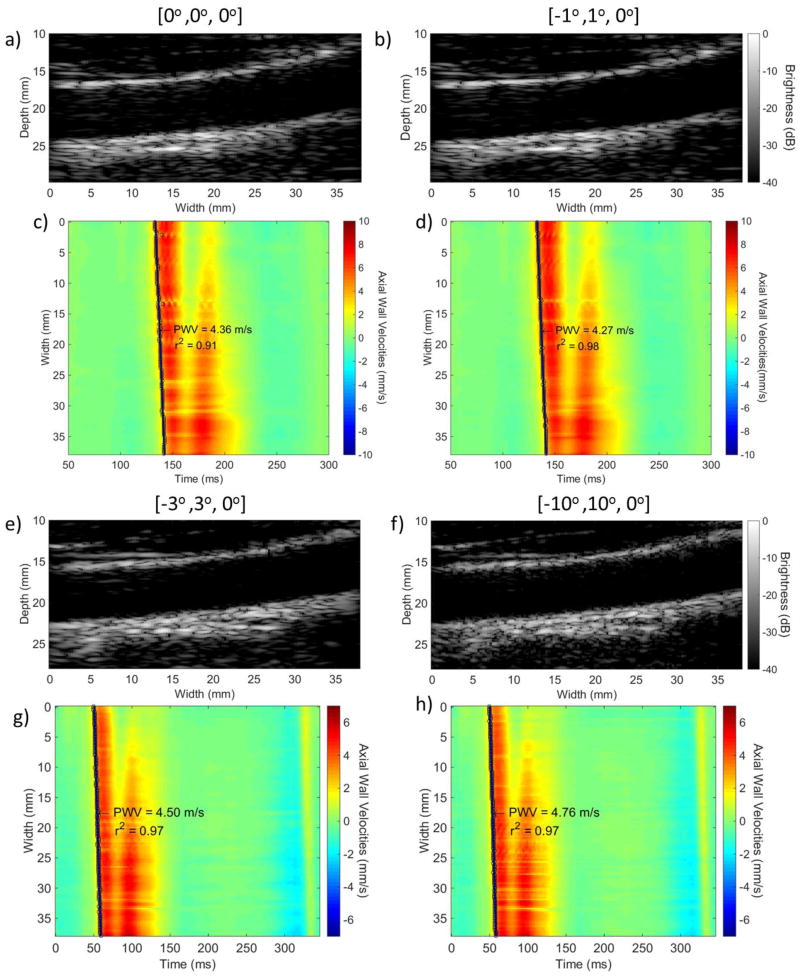

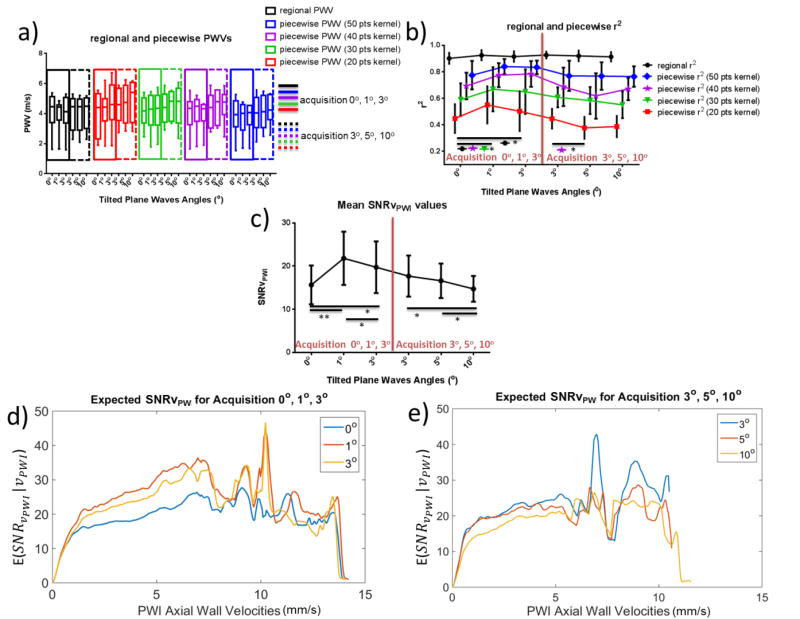

Fig. 11 shows B-mode images and the corresponding spatio-temporal maps using compounding with varying plane wave transmission angles. The statistical results for the six healthy subjects can be seen in Fig. 12. Fig. 12a shows the regional and piecewise PWVs measured for each set of transmission angles. Good agreement can be seen both within the same cardiac cycle as indicated by the PWVs within each of the colored bounding boxes (continuous line box for the acquisition corresponding to angles 0°, 1° and 3° and dashed line box for the acquisition corresponding to angles 3°, 5° and 10°) as well as between different cardiac cycles (between the continuous line and dashed line boxes).

Figure 11.

B-modes and spatio-temporal plots with the regional fit and the pulse wave velocity overlaid of a healthy volunteer created with three plane wave compounded acquisitions with the steering of each plane wave being a), c) [0°, 0°, 0°], b), d) [−1°, 1°, 0°], e), g) [−3°, 3°, 0°] and f), h) [−10°, 10°, 0°] respectively

Figure 12.

Statistical analysis of the in vivo plane wave transmission angle variation results. a) regional and piecewise PWVs for different transmission angles b) regional and piecewise r2 values for different transmission angles c) mean SNRvPWIfor different transmission angles d),e) expected SNRvPWI curves for different transmission angles (acquisitions 0°, 1°, 3° and 3°, 5°, 10° respectively). Asterisks indicate significant difference and the horizontal lines indicate the groups between which the corresponding level of significance was found (* : p≤0.05, ** : p≤0.01, *** : p≤0.001).

Figure 12b shows the corresponding regional and piecewise r2. Regional r2 showed a significant increase as the tilted plane wave transmission angle increased from 0° to 1° and from 0° to 3° (p≤0.05). Significant increases were found in the case of piecewise r2 between 0° and 1° for 30- and 40-point kernels (p≤0.05). In the case of acquisitions investigating the use of 3°, 5° and 10°, small decreases were found in the means of regional and piecewise r2, which, however, were not found to be significant, with the exception of a significant decrease between 3° and 5° for 40-point kernels (p≤0.05).

Fig. 12c depicts the mean SNRvPWI values. Significant increase was found between 0° and 1° (p≤0.01) as well as between 0° and 3° (p≤0.05). Additionally, a significant decrease was observed between 1° and 3° (p≤0.05). The mean SNRvPWI showed significant decreases as the transmission angles increased from 3° to 10° and from 5° to 10°. A non-significant decrease (p=0.1) was found between 3° and 5°. Similar findings can be seen in Figs. 12d and 12e, which depict the expected SNRvPWIcurves.

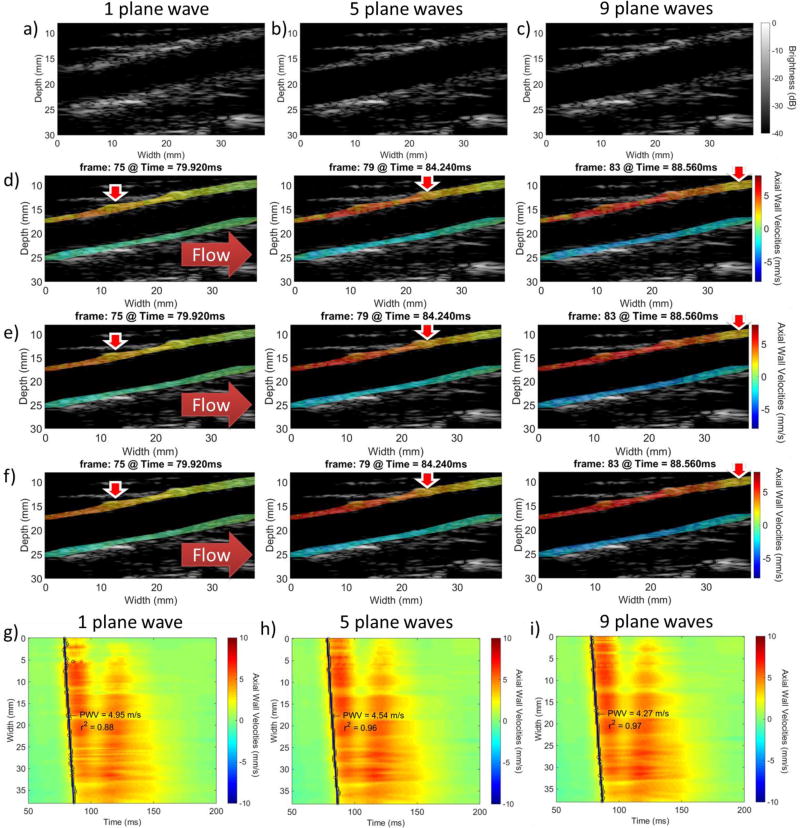

Fig. 13 shows a healthy carotid artery imaged with 1, 5 and 9 plane waves. Figs. 13a, 13b and 13c show the B-modes that correspond to 1, 5, and 9 plane waves respectively. The 5- and 9-plane wave compounded B-modes presented improvements compared to the single plane wave image. However, between them there was no apparent change in image quality. The corresponding PWI vPWI image sequences are shown in Figs. 13d, 13e and 13f. Figs. 13g, 13h and 13i show the resulting spatio-temporal maps.

Figure 13.

a), b), c): Compounded B-mode images of the common carotid of a healthy volunteer using 1, 5 and 9 plane waves respectively. d), e), f): PWI vPWI image sequences for 1, 5 and 9 plane wave acquisitions respectively. g), h), i): spatio-temporal plots with the regional fit and the pulse wave velocity overlaid for 1, 5 and 9 plane wave acquisitions respectively. Red corresponds to motion towards the transducer and blue corresponds to motion away from it. Horizontal solid red arrows indicate flow direction and vertical red arrows with the white contour indicate the approximate location where the vPWI obtain values close to their 50% downstroke point, thus indicating the pulse wave propagation.

Fig. 14 shows the results of the statistical analysis for various numbers of plane waves. Fig. 14a shows the mean regional and piecewise PWVs. Fig. 14b shows the increase in the r2 coefficient with the number of transmitted plane waves. However, significant increase was only found between the case of single plane wave imaging and the other imaging sequences. More specifically, in the case of 20- and 30-point kernels, significantly increased values (p≤0.01 and p≤0.05 respectively) were found between 1 and 3, 5, 7 and 9 plane waves. In the case of 40-point kernels significant increase was only found between 1 and 5, 7 and 9 plane waves (p≤0.05) while in the case of 50-point kernels the only significant increase was between 1 and 7 plane waves as well as 1 and 9 plane waves (p≤0.05). Finally, in the case of regional r2, while the ANOVA test rejected the null hypothesis that there was no difference between the means of each group (p≤0.05), no individual significant changes were found. Figs. 14c and 14d show the mean SNRvPWI values and the expected SNRvPWI curves for different numbers of plane waves. Similarly to Fig. 14b, significant increase only occurred between single plane wave imaging and multiple plane wave compounding (p≤0.05).

Figure 14.

Statistical analysis of the in vivo number of transmitted plane waves variation results. a) Regional and piecewise PWVs for different numbers of transmitted plane waves. b) Regional and piecewise r2 values for different numbers of transmitted plane waves. c) Mean SNRvPWI for different numbers of transmitted plane waves. d) Expected SNRvPWI curves for different numbers of transmitted plane waves. Asterisks indicate significant difference and the horizontal lines indicate the groups between which the corresponding level of significance was found (* : p≤0.05, ** : p≤0.01, *** : p≤0.001).

Discussion

In this study, PWI performance was found to improve by utilizing coherent compounding with the transition from single plane wave imaging to 3 plane wave coherent compounding being the most beneficial. PWV values were validated in a phantom and the benefits of using multiple steered plane waves were shown. Furthermore, repeatability of the PWV measurements was shown in vivo. To our knowledge, this is the first study to perform optimization of regional and piecewise PWI using coherent compounding by separating and independently investigating the effects of the main imaging parameters. Additionally, this study introduced and utilized a GPU-accelerated framework which allowed faster execution of time consuming operations (such as beamforming and motion estimation) and thus was catalytic in repeatedly processing the large amounts of data generated for the purpose of optimizing the imaging parameters. However, the main impact of this paper lies in optimizing the parameters involved in coherent compounding for the tracking and visualization of the pulse wave in vivo.

Phantom validation

Propagation of the negative pulse wave was observed in both the soft and stiff sections of the phantom. Figs. 5 and 6 indicated overall faster pulse wave propagation and lower vPWI magnitude in the stiff section. Similar observations were made in [16] where the mean peak axial wall velocities in stiffer atherosclerotic murine aortas with elevated PWVs were found to be significantly lower compared to normal aortas. Furthermore, as seen in Figs. 7a and 7b, the PWI measured regional and mean piecewise PWVs were validated against PWVs estimated by independent static testing. Agreement was also found between the mean piecewise PWVs and the regional PWVs, which was expected given the homogeneity of each phantom section. The smaller, 20-point kernels proved to be more susceptible to noise, given the low number of markers involved in the linear fit, thus leading to some deviations. However, these were small and mainly appeared in the case of single plane wave imaging which as seen in Figs. 7g and 7h was linked with lower mean SNRvPWI. Especially in the case of the stiff phantom section, piecewise PWVs were found to decrease as the number of the plane waves increased. However, the decreases were not significant and this could be attributed to the fact that thevPWI, have been shown to be underestimated in the case of lower numbers of plane waves [27], thus leading to the early detection of some of the 50% upstroke points and consequently yielding faster PWVs.

Increasing the number of plane waves showed an improvement in both the image quality, as seen in Fig. 5, as well as in the performance of PWI. More specifically, in Fig. 6, it can be seen that the quality of the spatio-temporal plots improved in both the stiff and soft sections of the phantom. In the case of single plane wave imaging, the vPWI at several lines appeared noisier and underestimated.

According to Figs. 10g and 10h, mean SNRvPWI was found to significantly increase as the number of plane waves increased from 1 to 3 and from 3 to 5, with a sharper increase in the former compared to the latter. The decreased SNRvPWI gains for more than 3 transmitted plane waves can be attributed to the motion of the phantom. Previous work has shown that when the insonified object undergoes motion in between plane wave transmits, coherent compounding is hindered [36] and thus further increase in the number of transmitted plane waves induces losses in SNRvPWI [33]. The corresponding expected SNRvPWI curves shown in Figs. 7e and 7f have a characteristic band-pass shape similar to the Strain Filter [37], with increased jitter error based on the Cramér-Rao lower bound more evident among the lower vPWI as also observed in [38] and SNRvPWI decreasing for higher vPWI being closer to the transition zone that occurs at high vPWI similarly to the Strain Filter [37], [39]. Finally, from these curves it is confirmed that the maximum vPWI found in the stiff phantom section are lower (approximately 5mm/s) compared to the soft phantom section (approximately 7mm/s).

Regarding Figs. 7c and 7d, while the regional r2 estimates were not significantly affected by changing the number of transmitted plane waves, increases were observed in piecewise r2 showing that coherent compounding aids in producing localized PWV estimates of higher quality. In the soft phantom case, significant increases were found for 3- and 5-plane wave compounding compared to single plane wave imaging for only the 20 point kernels (p≤0.05 and p≤0.01 respectively). This can mainly be attributed to the ideal properties of the phantom which produced overall high regional and piecewise r2 values, and thus only the most sensitive case of the 20-point kernels showed consistent significant increase with the number of transmitted plane waves. In the case of the stiff phantom section, the effects of including more plane waves were also found to be beneficial for the mean r2 values. However, the increased variability was detrimental to achieving significance. Additionally, the r2 coefficients were lower compared to the soft phantom case. This can be attributed in part to the lower vPWI magnitudes in the case of the stiff phantom which led to the 50% downstroke markers occurring at lower vPWI compared to the soft phantom. Consequently, as also shown in Figs. 7e and 7d, lower vPWI led to lower SNRvPWI, thus introducing jitter in the detection of the 50% downstroke points and variability in the estimated r2 values.

In vivo reproducibility study

Good intrasubject reproducibility of the estimated PWVs was found in healthy subjects for two different cardiac cycles measured 1–3 days apart. In all of the cases, the difference between the means of the PWVs estimated during each acquisition didn’t exceed 1 m/s. Similar findings have been reported in other clinical PWV studies using noninvasive techniques including widely used systems such as Sphygmocor (AtCor Medical, Sydney, Australia) and Complior (Artech Medical, Pantin, France) [40], [41]. Furthermore, the average carotid PWVs during each acquisition were within the carotid PWV range found in the existing literature (3–9 m/s [26], [42], [25]). The estimated PWV values were similar to the ones measured in a previous carotid PWI study (4–5.2 m/s, [14]) utilizing conventional ultrasound imaging with a clinical scanner (SonixTOUCH, Ultrasonix Medical Corp., Burnaby, BC, Canada).

In vivo optimization study

First, performance was assessed at different frame rates using single plane wave imaging. As Fig. 9 shows, while the quality of the spatio-temporal plots remains similar, the layout of the 50% upstroke markers changes significantly. More specifically, for the highest frame rate (8333 Hz) there are no consecutive 50% upstroke markers occurring at the same time. However, this comes at the expense of higher noise, especially at the region around 27–33 mm, which, while not greatly affecting the regional linear fit, has an effect on the smaller kernels. In the case of the lowest frame rate, multiple consecutive 50% upstroke markers lie on the same temporal line generating a staggered waveform and indicating that the frame rate is insufficient to capture the pulse wave propagation. This has a negative effect on the piecewise r2 values as shown in both Fig. 9g and in the statistical results shown in Fig. 10b. Fig. 10a asserts the reproducibility of PWVs at different frame rates at both regional and piecewise level. Regional PWVs were found to be similar to the piecewise PWVs, an expected result given that the subjects were healthy volunteers with no prior history of atherosclerosis and thus with homogeneous carotid walls. In the case of r2 values, Fig 10b indicates that while the regional r2 values remain unaffected, the piecewise r2 values increase as the frame rate increases from 926 Hz to 1667 Hz and then appear to saturate with no significant changes taking place between 1667, 2778 and 8333 Hz. It should be noted that at 8333 Hz the mean piecewise r2 values slightly decrease without showing significance. This slight decrease is due to the fact that the vPWI detected at this extremely high rate show increased jitter based on the Cramér-Rao lower bound. However, as also seen in Fig. 10c, this drop in SNRvPWI at 8333 Hz is not significant and thus doesn’t hinder the PWV estimation. On the other hand, the significant decreases in r2 at lower frame rates can be explained by the significantly increased TRMs. More specifically, as seen in Fig 10d for frame rates below 1667 Hz, over 60% of consecutive 50% upstroke markers are detected at the same time point and thus exacerbate the staggered appearance of the 50% upstroke markers waveform as also seen in Fig 9d. This impairs the linear fitting performance of PWI and induces errors. In the case of the sensitive 20-point kernels, even small increases in frame rate from 926 to 1190 Hz and from 1190 to 1667 Hz benefit the linear fitting, underlining the importance of increased frame rate in producing localized pulse wave velocity estimates.

In a recent study by Huang et al. [43], the effects of frame rate on the PWI r2 coefficient of determination were studied in silico. In that study, it was found that the optimal motion estimation rate was close to 200 Hz. However, it should be noted that in that study, conventional ultrasound imaging was simulated and, while the image width was similar to the one used in this study (approx. 40 mm), only 16 beams were used to create an image, thus effectively creating 16 independent 50% upstroke markers. This led to increased spacing between each beam and thus decreased frame rate is sufficient to properly capture pulse wave propagation. Nevertheless, agreement between the current study and that study was found. More specifically, given that SNRvPWI remains relatively stable for different frame rates, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the TRMs appear to be the main cause of r−2 fluctuation as frame rate changes. In Appendix B it is shown that in an ideal case scenario the TRM levels in [43] and in the current study are similar for the respective optimal frame rates.

Fig. 10e shows the expected SNRvPWI curves for different frame rates. It can be seen that PWI performance is similar at each frame rate with the expected SNRvPWI waveform at 8333 Hz having overall slightly lower values. Based on that figure it is observed that, while at medium and lower vPWI lower frame rates appear to achieve better SNRvPWIvalues, above 13 mm/s it can be seen that higher frame rates (1667 – 8333 Hz) perform better. This can be attributed to the fact that in the case of higher frame rates the same high vPWI, correspond to lower measured displacements prior to being normalized with respect to the frame rate and thus are further away from the transition zone [39] achieving higher quality.

In the next section of the study, the performance of PWI was investigated for compounding plane waves transmitted at different angles. Averaging plane wave acquisitions transmitted at 0° was found to produce poor results compared to compounding angled plane wave acquisitions. As seen in Figs. 11a, 11b and 11c, 11d the quality of the image and the vPWI was lower compared to the results of compounding with tilted plane waves transmitted at an angle of 1°. This was verified by the statistics in Fig 12 showing significant increases in both the r2 (p<0.05) and the mean SNRvPWI (p<0.01) values as the angle increased from 0° to 1°. Given that, by averaging plane waves transmitted at 0°, the side lobes affect the same locations in the image and thus do not cancel out via the coherent compounding approach, image quality deteriorates and the performance of the motion estimation algorithm is impaired [27]. Further increasing the transmission angle to 3° produced slightly worse results with smaller r2 gains and SNRvPWI significantly decreasing compared to the 1° case (p≤0.05). Similarly, in [28] it was found that increments of 1° provided higher image SNR and CNR compared to the case of 3° angle increments although it has to be noted that in that study the number of plane waves was not kept the same. For larger angles, no significant changes were found in the r2 values although the mean SNRvPWI values decreased between 3° and 10° as well as between 5° and 10°. A reason for this could be the fact that all of the sequences were at the same low frame rate (926 Hz) producing overall the low r2 values as previously seen in Fig. 10.

It should also be noted that in previous studies by Hansen et al. [44], [45] it was found that larger steering angles (>15°) produced better elastographic SNR, However, in those studies, special adaptive grating lobe correction was performed in order to mitigate their interference that leads to poor echo signal quality. Furthermore, large steering angles are beneficial for the estimation of 2D displacements (axial and lateral) which are necessary for the estimation of the full 2D strain tensor [44]. However, in the case of PWI, axial displacements are sufficient to detect the pulse wave propagation [16].

Finally, the effects of increasing the number of plane waves were investigated. The mean SNRvPWIvalues saturated after compounding more than 3 plane waves. More specifically, while the SNRvPWI increase from 1 to 3 plane waves was significant (p≤0.05) every subsequent increase only produced slight SNRvPWI increases. A similar SNR waveform was produced in [28] in silico, where tilted plane waves were added at increments of 1°. This saturation, as also observed and explained in the phantom case, can be attributed to the motion that carotids undergo between angled plane wave acquisitions thus resulting to reduced coherence and motion artifacts [36] consequently impacting SNRvPWI gains as the number of transmitted plane waves increases [33]. In the case of r2, further increase in the number of plane waves proved to be more effective since it produced significance for less sensitive (i.e. larger) kernel sizes. Increasing the number of plane waves from 3 to 5 produced significant gains for 40-point kernels compared to the single plane wave case and further increase from 5 to 7 plane waves produced significant gains for the largest and least sensitive 50-point kernels.

In summary, optimal PWI performance was found at relatively high frame rates ranging from 1667 to 2778 Hz. Lower frame rates showed high TRMs and significantly lower r2 and thus were deemed incapable of reliably tracking the local pulse wave propagation. Furthermore, compounding at increments of 1° resulted in optimal gains in both the r2 values and the SNRvPWI. Finally, SNRvPWI and r2 values were augmented by increasing the number of compounded plane waves used with the most prominent improvements occurring at the transition from single plane wave imaging to 3-plane wave compounding. Consequently, given these results summarized in Table II and the possible combinations seen in Table III, the most effective imaging sequences that would provide the most advantageous performance would be 3-plane wave compounding at 2778 Hz to accommodate faster propagating pulse waves or 5-plane wave compounding at 1667Hz in case higher r2 quality is needed.

Table III.

Illustration of the tradeoff between frame rate and the number of transmitted plane waves. Y corresponds to a valid combination and N corresponds to an invalid combination.

| Frame Rate (Hz)\Number of plane waves | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 926 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 1190 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| 1667 | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| 2778 | Y | Y | N | N | N |

| 8333 | Y | N | N | N | N |

Limitations and future work

One of the limitations of the current work lies in the fact that the proposed method of estimating the PWVs suffers from errors introduced by reflected waves. Reflected waves are seen in both the vessel phantom due to its fixed ends as well at the carotid close to the bifurcation. In order to overcome this issue the wavefront velocity of the pulse wave is tracked, which has been shown to be less affected by reflected waves [2] as also mentioned in a previous PWI study [16]. Another way to deal with this particular issue is utilize a recently developed inverse problem methodology to infer PWVs from the spatio-temporal plot and the arterial vessel characteristics [32].

Furthermore, it should be noted that while this study investigated various values of the coherent compounding parameters, the search was not exhaustive. This is justified given the in vivo setting of the study compared to similar studies that performed more meticulous optimization in a simulation environment [28], [43]. Given the volume of data that needed to be processed, optimization was performed in a pruned and sparser variable space, which however produced meaningful results which aim at tuning PWI towards clinical usage.

Moreover, for the purpose of this study motion estimation rate (MER) [39], [43] and frame rate were not separated. Decoupling these two variables could be advantageous for PWI; however, this is beyond the scope of this study and will be addressed in future research.

Furthermore, it has to be noted that selecting to induce pre-strain to the phantom by raising the water reservoir to 50mm was arbitrarily selected. It appeared to produce sufficient pre-strain without damaging the phantoms and it helped in keeping uniform conditions among different phantom scans. Ongoing work aims at determining pre-stretch conditions closer to physiological and performing intra-luminal pressure measurements with the introduction of a catheter in the phantoms.

Additionally, in the case of the phantom study, the pumping rate of the peristaltic pump was set higher than the physiological rate (1 Hz). This was done to obtain more cycles with a single ultrasound acquisition. This was of great utility for the current study, especially given the large amount of data that was generated with each ultrasound acquisition. Furthermore, care was taken to ensure that with the pumping rate being 2Hz, each wave had sufficient time to propagate along the phantom and also for the resulting reflections to subside without mixing with the next incoming wave.

Finally, future work will include clinical studies utilizing the optimized compounded PWI sequences to test its effectiveness in assessing the localized stiffness of patients with vascular pathology.

Conclusion

A GPU-accelerated framework was developed to process the volume of data produced by high-frame rate coherent compounding acquisitions. A phantom study was performed to validate the results of compounded PWI. Increasing the number of transmitted plane waves was found to enhance SNRvPWI and r2. Reproducibility of the PWVs from compounding sequences was also verified in vivo among healthy volunteers. Moreover, the results were within physiological range. The most beneficial frame rates for tracking the pulse wave in vivo were found to be between 1667 and 2778 Hz. Furthermore, 1° was found to be the optimal plane wave transmission angle for the tilted plane waves. Finally, most significant improvements in the performance of PWI were found with the transition from single plane wave imaging to 3-plane wave compounding acquisitions. Further increase in the number of plane waves produced smaller gains. Consequently, given the limitations in frame rate and the gains in tracking the pulse wave from increasing the number of transmitted plane waves, acquisitions with 3 plane waves at 2778 Hz and 5 plane waves at 1667 Hz are considered to be optimal for imaging the pulse wave propagation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported from the National Institutes of Health (research grant: NIH R01-HL098830). The authors would also like to thank Ronny Li, Ph.D. and Pierre Nauleau, Ph.D.

Appendix A

Let f(m,l,n) and g(m,l,n) represent the values of the reference and comparison RF-signal at m-th sample, l-th line and n-th frame, respectively. The NCC between the reference and the comparison windows is defined as:

| (A.1) |

Where u is the origin of the reference window, W is the window size and τ is the shift between the comparison and reference windows, which in this study is confined between −1 and 1 in order to yield sub-sample displacements.

The first step of the proposed algorithm consists of estimating in parallel the sum-tables for each line (l) in each frame (n) of the image sequence. The sum-table for the comparison windows is given by the following formula:

| (A.2) |

where M is the number of samples for each line. Similarly for the reference windows:

| (A.3) |

And finally the sum-table for the nominator of equation (A.1) can be constructed for τ = −1, 0 and 1:

| (A.4) |

Subsequently, the RNCC function is estimated in parallel for all the lines in all the frames in the image sequence for τ = −1, 0 and 1. Thus:

| (A.5) |

The resulting 4-D matrix containing RNCC has a size of (number of windows)×(number of lines)×(number of frames)×3. Given that RNCC only contained integer lags interpolation is necessary to improve the estimation accuracy. A cosine function was selected to fit to the three points (τ = −1,0, 1) [46] and thus, to estimate the axial wall displacements (dPWI) in parallel for all the windows in all the lines of all the frames the following calculations were made:

Where d(u, l, n) are the sub-sample axial wall displacements at each window position u, line l and frame n.

Appendix B

In an ideal case scenario, if no or relatively small noise in vPWI is considered, the relative TRM values depend on the lateral distance between neighboring lines and the frame rate. This is because the frame rate provides the sampling period at which the propagation of the wave is being tracked and which in order to produce the best linear fitting should ideally be close to the time that the wave needs to propagate from one line to the next. Thus, it is valid to assume that TRMs are proportional to the ratio of the time needed for the wave to travel from one line to the next (tpropagation) to the sampling period (T):

| (B.1) |

Where dlines is the distance between neighboring lines which can be roughly estimated as:

| (B.2) |

Substituting (B.2) in (B.1) we have

| (B.3) |

Given that in [43] and in the current study Widthtot and PWV are similar, it can be argued that TRM is only dependent on the ratio :

| (B.4) |

We can see that for FR = 200 Hz and Nlines = 16 the ratio is 12.5 and thus to achieve a similar ratio and consequently the same TRM level with Nlines = 128, a frame rate of approximately 1600 Hz is required. This is corroborated by the current study given that r2 values reach a plateau at approximately 1667 Hz thus showing agreement with the results of the aforementioned study.

Bibliography

- 1.Fung YC. Biomechanics - Circulation. Springer; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nichols W, O’Rourke MF, Vlachopoulos C. McDonald’s blood flow in arteries, sixth edition: theoretical, experimental and clinical principles. CRC pr. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laurent S, Cockcroft J, Van Bortel L, Boutouyrie P, Giannattasio C, Hayoz D, Pannier B, Vlachopoulos C, Wilkinson I, Struijker-Boudier H. Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: methodological issues and clinical applications. Eur. Heart J. 2006 Nov.27(21):2588–605. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tozzi P, Corno A, Hayoz D. Definition of arterial compliance. Am. J. Physiol. - Hear. Circ. Physiol. 2000;278(4) doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.4.H1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willum-Hansen T, Staessen J, Torp-Pedersen C, Rasmussen S, Thijs L, Ibsen H, Jeppesen J. Prognostic value of aortic pulse wave velocity as index of arterial stiffness in the general population. Circulation. 2006;113(5):664–70. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.579342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ben-Shlomo Y, Spears M, Boustred C, May M, Anderson SG, Benjamin EJ, Boutouyrie P, Cameron J, Chen C-H, Cruickshank JK, Hwang S-J, Lakatta EG, Laurent S, Maldonado J, Mitchell GF, Najjar SS, Newman AB, Ohishi M, Pannier B, Pereira T, Vasan RS, Shokawa T, Sutton-Tyrell K, Verbeke F, Wang K-L, Webb DJ, Willum Hansen T, Zoungas S, McEniery CM, Cockcroft JR, Wilkinson IB. Aortic pulse wave velocity improves cardiovascular event prediction: an individual participant meta-analysis of prospective observational data from 17,635 subjects. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014 Feb.63(7):636–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Popele NM, Grobbee DE, Bots ML, Asmar R, Topouchian J, Reneman RS, Hoeks AP, Van Der Kuip DA, Hofman A, Witteman JC. Association between arterial stiffness and atherosclerosis: The Rotterdam study. Stroke. 2001 Feb.32(2):454–460. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.2.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laurent S, Boutouyrie P, Asmar R, Gautier I, Laloux B, Guize L, Ducimetiere P, Benetos A. Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2001;37(5):1236–1241. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.5.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adji A, O’Rourke MF, Namasivayam M. Arterial stiffness, its assessment, prognostic value, and implications for treatment. Am. J. Hypertens. 2011 Jan.24(1):5–17. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weber T, Wassertheurer S, Hametner B, Parragh S, Eber B. Noninvasive methods to assess pulse wave velocity. J. Hypertens. 2015;33(5):1023–1031. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vorp DA. Biomechanics of abdominal aortic aneurysm. J. Biomech. 2007 Jan.40(9):1887–1902. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Bortel LM, Laurent S, Boutouyrie P, Chowienczyk P, Cruickshank JK, De Backer T, Filipovsky J, Huybrechts S, Mattace-Raso FUS, Protogerou AD, Schillaci G, Segers P, Vermeersch S, Weber T. Expert consensus document on the measurement of aortic stiffness in daily practice using carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity. J. Hypertens. 2012;30(3):445–448. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834fa8b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell GF, Hwang S-J, Vasan RS, Larson MG, Pencina MJ, Hamburg NM, Vita JA, Levy D, Benjamin EJ. Arterial stiffness and cardiovascular events: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2010 Feb.121(4):505–11. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.886655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo J, Li RX, Konofagou EE. Pulse wave imaging of the human carotid artery: an in vivo feasibility study. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2012 Jan.59(1):174–81. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2012.2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujikura K, Luo J, Gamarnik V, Pernot M, Fukumoto R, Tilson MD, Konofagou EE. A novel noninvasive technique for pulse-wave imaging and characterization of clinically-significant vascular mechanical properties in vivo. Ultrason. Imaging. 2007 Jul.29(3):137–54. doi: 10.1177/016173460702900301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Apostolakis IZ, Nandlall SD, Konofagou EE. Piecewise pulse wave imaging (ppwi) for detection and monitoring of focal vascular disease in murine aortas and carotids in vivo. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2016 Jan.35(1):13–28. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2015.2453194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herold V, Parczyk M, Mörchel P, Ziener CH, Klug G, Bauer WR, Rommel E, Jakob PM. In vivo measurement of local aortic pulse-wave velocity in mice with mr microscopy at 17.6 tesla. Magn. Reson. Med. 2009 Jun.61(6):1293–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Z, Yang Y, Yuan L, Liu J, Duan Y, Cao T. Noninvasive method for measuring local pulse wave velocity by dual pulse wave doppler: in vitro and in vivo studies. PLoS One. 2015 Jan.10(3):1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eriksson A, Greiff E, Loupas T, Persson M, Pesque P. Arterial pulse wave velocity with tissue doppler imaging. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2002 May;28(5):571–580. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(02)00495-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Markl M, Wallis W, Strecker C, Gladstone BP, Vach W, Harloff A. Analysis of pulse wave velocity in the thoracic aorta by flow-sensitive four-dimensional MRI: reproducibility and correlation with characteristics in patients with aortic atherosclerosis. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2012 May;35(5):1162–8. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li RX, Jourard I, Salomon J, Narayanan P, Walker LA, Russo C, di Tullio M, Konofagou EE. Noninvasive arterial pulse pressure mapping using pulse wave ultrasound manometry in hypertensive aortas and stenotic carotid arteries in vivo; IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo J, Fujikura K, Tyrie LS, Tilson MD, Konofagou EE. Pulse wave imaging of normal and aneurysmal abdominal aortas in vivo. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2009 Apr.28(4):477–86. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2008.928179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li RX, Qaqish W, Konofagou EE. Performance assessment of pulse wave imaging using conventional ultrasound in canine aortas ex vivo and normal human arteries in vivo. Artery Res. 2015 Sep.11:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.artres.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanter M, Fink M. Ultrafast imaging in biomedical ultrasound. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2014;61(1):102–119. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2014.6689779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kruizinga P, Mastik F, van den Oord SCH, Schinkel AFL, Bosch JG, de Jong N, van Soest G, van der Steen AFW. High-definition imaging of carotid artery wall dynamics. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2014;40(10):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Couade M, Pernot M, Messas E, Emmerich J, Hagège a, Fink M, Tanter M. Ultrafast imaging of the arterial pulse wave. Irbm. 2011 Apr.32(2):106–108. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montaldo G, Tanter M, Bercoff J, Benech N, Fink M. Coherent plane-wave compounding for very high frame rate ultrasonography and transient elastography. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2009;56(3):489–506. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2009.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poree J, Garcia D, Chayer B, Ohayon J, Cloutier G. Noninvasive vascular elastography with plane strain incompressibility assumption using ultrafast coherent compound plane pave imaging. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2015 Dec.34(12):2618–31. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2015.2450992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Osmanski B-F, Pernot M, Montaldo G, Bel A, Messas E, Tanter M. Ultrafast doppler imaging of blood flow dynamics in the myocardium. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2012;31(8):1661–1668. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2012.2203316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ekroll IK, Voormolen MM, Standal OK-V, Rau JM, Lovstakken L. Coherent compounding in doppler imaging. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2015 Sep.62(9):1634–43. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2015.007010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kashif AS, Lotz TF, McGarry MD, Pattison AJ, Chase JG. Silicone breast phantoms for elastographic imaging evaluation. Med. Phys. 2013 Jun.40(6):63503. doi: 10.1118/1.4805096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mcgarry M, Li R, Apostolakis I, Nauleau P, Konofagou EE. An inverse approach to determining spatially varying arterial compliance using ultrasound imaging. Phys. Med. Biol. 2016 Aug.61(15):5486–5507. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/61/15/5486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Denarie B, Tangen TA, Ekroll IK, Rolim N, Torp H, Bjastad T, Lovstakken L. Coherent plane wave compounding for very high frame rate ultrasonography of rapidly moving targets. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2013;32(7):1265–1276. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2013.2255310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo J, Konofagou E. A fast normalized cross-correlation calculation method for motion estimation. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2010 Jun.57(6):1347–57. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2010.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bunting EA, Provost J, Konofagou EE. Stochastic precision analysis of 2D cardiac strain estimation in vivo. Phys. Med. Biol. 2014 Nov.59(22):6841–58. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/59/22/6841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang J, Lu J. Motion artifacts of extended high frame rate imaging. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2007;54(7):1303–1315. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2007.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Varghese T, Ophir J. A theoretical framework for performance characterization of elastography: the strain filter. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 1997;44(1):164–172. doi: 10.1109/58.585212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinton GF, Dahl JJ, Trahey GE. Rapid tracking of small displacements with ultrasound. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2006 Jun.53(6):1103–1117. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2006.1642509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bunting EA, Provost J, Konofagou EE. Stochastic precision analysis of 2D cardiac strain estimation in vivo. Phys. Med. Biol. 2014 Nov.59(22):6841–58. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/59/22/6841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilkinson IB, Fuchs SA, Jansen IM, Spratt JC, Murray GD, Cockcroft JR, Webb DJ. Reproducibility of pulse wave velocity and augmentation index measured by pulse wave analysis. J. Hypertens. 1998 Dec.16(12 Pt 2):2079–84. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816121-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]