Abstract

Introduction

Esophageal cancer is an extremely aggressive neoplasm, diagnosed in about 17,000 Americans every year with a mortality rate of more than 80% within five years and a median overall survival of just 13 months. For decades, the go-to regimen for esophageal cancer patients has been the use of taxane and platinum-based chemotherapy regimens, which has yielded the field’s most dire survival statistics.

Areas covered

Combination immunotherapy and a more robust molecular diagnostic platform for esophageal tumors could improve patient management strategies and potentially extend lives beyond the current survival figures. Analyzing a panel of biomarkers including those affiliated with taxane and platinum resistance (ERCC1 and TUBB3) as well as immunotherapy effectiveness (PD-L1) would provide oncologists more information on how to optimize first-line therapy for esophageal cancer.

Expert commentary

Of the 12 FDA-approved therapies in esophageal cancer, zero target the genome. A majority of the approved drugs either target or are effected by proteomic expression. Therefore, a broader understanding of diagnostic biomarkers could give more clarity and direction in treating esophageal cancer in concert with a greater use of immunotherapy.

Keywords: Esophageal cancer, Precision medicine, Molecular oncology, Targeted therapy, PD-L1 inhibitors, CTLA-4 inhibitors, Combination immunotherapy, Proteomics, Targeted chemotherapy, Esophageal adenocarcinoma

1.0 Introduction

The molecular oncology arena has evolved tremendously in the last decade. New assays to detect and measure biomarkers that can predict the response to chemotherapy are being developed. Molecular diagnostics is the fastest growing division of in vitro diagnostics driven by multiple factors including the ability to forecast the therapeutic efficacy of expensive and sometimes toxic drugs [1]. Oncology accounts for the biggest slice of the molecular diagnostics market with an estimated 34% annual growth rate and is projected to be worth $8 billion in the next four years [2]. These technologies hold the promise to analyze a panel of indication-specific biomarkers in an individual’s tumor which can guide oncologists to optimal patient management strategies based on what is expressed or mutated in a patient’s tumor sample. Focusing on treating an individual’s tumor biology rather than the histological diagnosis is the essence of “precision medicine”.

Overall survival has improved for most cancers in the last two decades. However, a few cancers such as pancreatic, non-small cell lung, and esophageal carcinoma (EC) have retained stagnant survival outcomes mainly due to presentation in advanced stages but also due to ineffective chemotherapeutic agents [3]. It is clear that there is a need for a new approach to treating these cancers [4].

Clinical trials going down the conventional path of treating EC with platins, anthracyclines, topoisomerase I inhibitors, and pyrimidine analogues are yielding underwhelming results. A 2014 clinical trial compared two first-line therapy regimens using the most common drug classes for EC. A total of 416 gastroesophageal cancer patients were given either fluorouracil, leucovorin and Irinotecan (FOLFIRI) or cisplatin and capecitabine [5]. The average time-to-treatment failure was 5.1 months (FOLFIRI) and 4.2 months (cisplatin and capecitabine), respectively. Median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) duration were only 5.5 months, and 9.5 months respectively for the entire cohort [5]. Additional guidance to improve the selection of therapeutic agents would be more informative in the decision process.

There is potential to achieve improved outcomes by using molecular diagnostics to scrutinize biomarkers that can indicate benefit or treatment resistance affiliated with available drugs. Program death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression assays are recommended to qualify a patient for an immunotherapy clinical trial in other cancerous indications and should be highly considered in esophageal cancer as well. PD-L1 also possesses negative prognostic factors as it has been associated with younger patient age, more aggressive disease, higher tumor grade, and shorter overall survival in gastric and breast cancer [6,7]. Excision repair 1 (ERCC1), tubulin beta 3 class III (TUBB3), topoisomerase 1 (TOPO1), and topoisomerase 2-alpha (TOPO2A) proteomic assays should also be considered to identify if resistance markers or biomarkers associated with increased benefit are present in the tumor. Lastly, receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-2 (HER2) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression diagnostics could be considered for routine analysis to examine if the patient is a candidate for FDA-approved HER2 therapy or off-label tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Optimizing patient selection for their aptness to gain an immune response to tumor cells could also improve outcomes. PD-L1 expression in solid tumors is a marker of cancer’s ability to mask itself from T-cells in the adaptive immune system. Tumors that express PD-L1 ‘fake out’ the immune system by preventing a T-cell mediated response to cancer. Blocking PD-L1 protein on the surface of the tumor, as well as other ligands on the T-cell, would allow the immune system to recognize esophageal cancer as an antigen and could improve clinical outcomes.

The initial success of immunotherapy has been shown in several solid tumor clinical trials. Understanding the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of anti-PD-L1 drugs will give insight as to how immunotherapy can fit into the clinical paradigm of EC treatment. Taken together, immunotherapy and expanded molecular diagnostics could improve survival outcomes for esophageal cancer patients.

2.0 Esophageal Cancer: an Epidemic with Poor Outcomes

Esophageal cancer (EC) possesses a significant health risk due to its rising incidence and dismal survival rates. Esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) has gone up 6-fold in frequency in the preceding two decades, making its rate of increased occurrence the highest of all major cancers in the US [4,8]. Interestingly, there has also been a shift in primary tumor location and histological type due to unknown etiological factors [8]. Esophageal cancer typically begins in the mucosa of the esophagus and spreads through deeper tissue layers i.e. the submucosa, muscle layers, and serosa. Simultaneously there may be lymphatic or hematogenic progression. Risk of nodal or distant metastasis is more likely with greater depth of invasion. The most common histological diagnoses of esophageal cancer are squamous cell and adenocarcinoma. The squamous cell carcinoma type was once the more common diagnosis in the United States; however, the occurrence of adenocarcinoma has risen significantly in the last 30 years [9,10]. The incidence of adenocarcinoma has increased most prevalently among white males, and patients who present with esophageal cancer are an average age of 67 years old [11,12]. Adenocarcinoma usually forms in the lower (distal) part of the esophagus, near the stomach or what is known as the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) [13].

Survival for esophageal cancer has remained flat-lined during the same timeframe. Since 1975, 5-year survival rates have increased for most other cancers, with some cancers seeing 50 to 60 percent 5-year survival improvements over the last 40 years (Figure 1) [14]. Esophageal cancer continues to have poor prognosis with about 18 percent 5-year survival rate. It is expected that 16,910 patients will be diagnosed with esophageal cancer in 2016 and 15,690 will succumb to the disease [14]. If esophageal cancer is detected in the earlier stages of development there is an improved chance of surviving five years or longer; however, 80 percent of EC patients present with advanced disease (regional and distant metastases) [15]. It is imperative that comprehensive scrutiny of proteomic expression of the tumor is completed to understand the risk of cancer progression. A robust diagnostic panel may also give insight on what proteins can be used as targets and which resistance markers will limit the efficacy of first-line therapy.

Figure 1.

Five-year survival rates for some of the most common cancers in the United States in 1975 paired with current available figures. [14].

2.1 Current State of Medical Oncology for Esophageal Cancer

Esophageal resection remains integral for definitive treatment for loco-regional esophageal cancer. Given a high rate of relapse after resection – adjuvant or neo-adjuvant chemotherapy/chemo radiotherapy has become standard of care. Better staging techniques has contributed to improved treatment outcomes by enabling circumvention of surgical resection for moribund patients with metastatic disease. The other major advancement has been a push towards earlier diagnosis and associated organ-sparing treatment. Until just ten years ago standard treatment for high-grade dysplasia (Tis) and early stage cancer (T1a and b) used to be an esophagectomy which carries a high peri-operative and long-term morbidity. Now most of these patients can be managed with endoscopic treatment such as ablation and endoscopic resection allowing retention of native esophageal function [16]. However, few patients are diagnosed in early stages and the majority of patients present in stage II or later. After excluding a substantial proportion of stage IV patients, treatment for loco-regional disease (stage II and III) becomes the focus.

Patients diagnosed with loco-regional esophageal cancer are usually followed with one of the five paths if treatment is proposed depending on histological status and patient fitness [17].

Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by esophageal resection

Esophageal resection followed by adjuvant therapy

Surgery alone

Chemoradiation therapy alone

Perioperative ‘sandwich’ chemotherapy

While there is consensus that ‘something other than surgery alone’ should be done for EC, even the other four approaches have a five-year survival rate around 10–15%, demonstrating that the treatment of esophageal cancer could use an alternate approach [17].

Genomic alterations in cancer cells result in abnormalities of protein expression which can give insight on whether certain drugs will be effective. For instance, if a tumor expresses ERCC1, which is a resistance marker for platinum therapy, drugs like Cisplatin and Carboplatin will have decreased benefit [18–20] (Table 1). Patients are not routinely assessed for the expression of therapeutically relevant biomarkers and are subjected to blanket regimens of FDA approved drugs.

Table 1.

| Drug | Biomarker | Brand Name | Drug Status | Type of treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capecitabine | Xeloda® | FDA Approved | Chemotherapy | |

| Carboplatin | ERCC1 | Generic | FDA Approved | Chemotherapy |

| Cisplatin | ERCC1 | Platinol® | FDA Approved | Chemotherapy |

| Docetaxel | TUBB3 | Taxotere® | FDA Approved | Chemotherapy |

| Epirubicin | TOPO2A | Ellence® | FDA Approved | Chemotherapy |

| Etoposide | TOPO2A | Etopophos® | FDA Approved | Chemotherapy |

| Irinotecan | TOPO-I | Camptosar® | FDA Approved | Chemotherapy |

| Oxyplatin | ERCC1 | Eloxatin® | FDA Approved | Chemotherapy |

| Paclitaxel | TUBB3 | Taxol® | FDA Approved | Chemotherapy |

| Trastuzumab | HER2 | Herceptin® | FDA Approved | Targeted Therapy |

| Fluorouracil | Generic | FDA Approved | Chemotherapy | |

| Mitocycin | Generic | FDA Approved | Chemotherapy | |

| Cetuximab | EGFR | Erbitux® | Off-label | Targeted Therapy |

| MEDI4736 | PD-L1 | Durvalumab® | Clinical Trails | Targeted Therapy |

ERCC1 – Excision Repair Cross-Complementation Group 1

TUBB3 – Tubulin Beta 3

TOPO2A - Type II Topoisomerase

TOPO-I - Topoisomerase-1

HER2 – Receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-2

EGFR – Epidermal growth factor receptor

PD-L1 - Programmed death-ligand 1

![]()

Currently, 12 drugs are FDA approved for esophageal cancer, nine of which have clinical biomarkers associated with either resistance or improved outcomes (Table 1) [21]. It is not routine practice to order protein diagnostics for esophageal cancer (with the exception of HER2 and trastuzumab) [18]. If those proteins (designated in green in Table 1) are present in the tumor, those drugs have an increased likelihood of benefit. Conversely, if the resistant markers (shown in red in Table 1) are expressed in those tumors, the affiliated drugs will have a reduced likelihood of benefit. Without knowing the expression levels of these proteins, there is a lack of clarity on how to create effective patient management strategies to improve overall survival and decrease side effects by avoiding ineffective agents.

3.0 The Philosophy of ‘Precision Medicine’

The basic science, clinical pathology, and medical oncology communities have made remarkable achievements working together on analyzing, classifying and treating an array of deadly cancers over the last 45 years. In 1971, a person diagnosed with any cancer had a 50% chance of surviving for just one year. Today, a person with any type of cancer has a 50% chance to survive ten years from the time of initial diagnosis [22]. These improved outcomes may be a result of the field becoming increasingly more personalized over the decades. Indeed, earlier detection and an expanding arsenal of targeted therapy, small-molecule therapy and chemotherapies have contributed to heightened clinical care for cancer patients. However, we still have a long way to go with treating the cancers with the lowest survival rates. A birds-eye-view of how we have treated cancer over the last 100 years (Figure 2) highlights how targeting the biology of a tumor, rather than the location and histology, has improved survival outcomes over the last century. Moving the field farther in this direction could have a profound effect on survival outcomes for the toughest cancers (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Brief history of precision medicine in medical oncology. A birds-eye-view of how more precise patient management strategies have contributed to improved survival rates in all cancers over the last century [14,82]. EGFR – epidermal growth factor receptor; KRAS - V-Ki-ras2 Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog; ER – estrogen receptor; HER2 -- Receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-2; PR – progesterone receptor.

3.1 “Precision” Chemotherapy

If a patient was diagnosed with esophageal cancer and the plan was to place him/her on Cisplatin and Irinotecan, it would seem logical to investigate whether or not ERCC1 and TOPO1 were present in the tumor. There is evidence that these biomarkers add therapeutic value to a treatment plan because their expression can indicate increased or decreased efficacy of various drugs. Analyzing a panel of proteins applicable to esophageal cancer treatment (TUBB3, ERCC1, TOPO1, TOPO2A) could guide oncologists to utilize chemotherapy in the same manner as targeted drugs. TUBB3 and ERCC1 can reveal if a tumor possesses resistance to taxanes or platinum-based therapy [19,20,23,24]. TOPO1 and TOPO2A expression can reveal that a patient could benefit from topoisomerase inhibitors or anthracyclines, respectively [24,25]. Adding targeted therapy markers like HER2 and EGFR would also be pertinent for this panel to see if a patient was a good candidate for targeted therapy [26–28]. Finally, immunotherapy biomarker PD-L1 would reveal if the tumor was masking itself from the immune system of the patient [29–31]. Gathering information about what is making the tumor successful or resistant to certain drugs is important when optimizing first-line therapy.

Figure 3 proposes a workflow suggesting how a robust diagnostic platform could be implemented for esophageal cancer patients. Fundamentally, this workflow would give oncologists more insight on how a patient may respond to various types of chemotherapy drugs or whether the patient would be a good candidate for targeted or immune system therapy (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Potential pathology-based workflow for esophageal tumor specimen to optimize patient management strategies for esophageal cancer cases in the event the patient’s surgeon and oncologist opt for esophagectomy followed by adjuvant therapy. We recommend this proteomic panel to be utilized in order to scrutinize potential drug targets or chemotherapy resistant markers expressed in a patient’s tumor. ERCC1 – Excision Repair Cross-Complementation Group 1; TUBB3 – Tubulin Beta 3; TOPO2A - Type II Topoisomerase; TOPO-I – Topoisomerase-1; HER2 – Receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-2; EGFR – Epidermal growth factor receptor; PD-L1 - Programmed death-ligand 1; 5-FU -- Fluorouracil. Crossed out drugs names = do not use. Non-crossed out drug names = consider for use.

There has not been a study looking into improved survival statistics utilizing a proteomic assay panel like the one proposed in figure 3 in esophageal cancer or other solid tumor types. However, studies are beginning to tricking in establishing improved survival with commercial diagnostics in a few cancer indications. A study published in NEJM in 2015 showed that a 21-gene expression assay used for low-risk breast cancer patients identified subjects who would receive no benefit from additional chemotherapy which lowered the rate of recurrence in this population using endocrine therapy alone [32]. Another study which quantified HER2 in breast cancer samples with a commercial mass spectrometry assay (rather than the gold standard of immunohistochemistry) demonstrated prognostic utility. HER2 levels >2200 amol/μg were associated with significant extended disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) in adjuvant cases as well as longer OS in metastatic cases when treated with HER2 targeted therapy [33]. Molecular oncology clearly holds great diagnostic and prognostic potential.

3.2 One-Size-Fits-All Models are Impairing Targeted Therapy for EC

Over the last decade, oncology drugs utilizing monoclonal antibodies in concert with standard chemotherapy regimens in gastroesophageal cancer (GEC) generated poor trial results [34–38]. These underwhelming outcomes led to the growing awareness that targeted therapies should be used for appropriate patient populations whose tumors express the affiliated biomarker “target”. A targeted therapeutic will understandably be ineffective if the biomarker the drug is targeting is absent in the tumor. This circumstance would have no effect on the cancer’s progression and would risk unnecessary toxicity to the patient.

Use of targeted drugs in clinical trials involving gastroesophageal cancer in many cases have not been patient-selective based upon expression of companion biomarkers [37]. Administering an EGFR inhibitor such as cetuximab to the entire GEC population, where EGFR amplification occurs in an estimated 15% of patients, will understandably give disappointing results [34,35]. Conversely, studies that have been more discriminating in assembling their cohorts based on companion diagnostics have demonstrated that gastroesophageal cancer subtypes with EGFR overexpression benefit from anti-EGFR therapy [39]. It is logical to know if the target is indeed present in the tumor in clinical practice or while designing a clinical trial.

Esophageal and gastric cancers share first-line therapy protocols as well as molecular oncology tactics when it comes to targeting growth factor receptors like EGFR and HER2 [40,41]. The EXPAND trial revealed that advanced gastric cancer patients with the highest EGFR expression in their tumor biopsies retained the most survival benefit from cetuximab (anti-EGFR) therapy included in a standard chemo regimen [35,39]. Even though the EXPAND trial concluded there was no benefit adding EGFR targeted therapy to chemo regimen in 455 gastric cancer patients receiving first-line therapy – retrospective analysis demonstrated that those receiving cetuximab with the highest EGFR expression (via immunohistochemistry) had a better response to treatment [35]. Retrospective EGFR diagnostics also revealed that dozens of patients with clear overexpression of EGFR were not put in the cetuximab (anti-EGFR) arm of the trial [35]. The EXPAND trial may have missed an opportunity to yield significant data and improve progression-free and overall survival for a number patients had investigators screened for EGFR expression before the trial started.

The ToGA trial demonstrated that the cohorts of gastroesophageal patients with the most HER2 expression had longer survival rates on anti-HER2 therapy than other +3 IHC HER2 positive patients on the lower end of the HER2 expression, as quantified by mass spectrometry [42]. Therefore, not only knowing the presence of the biomarker is critical but knowing the degree of expressed drug target can yield prognostic data.

Accumulating evidence indicates that use of targeted agents with standard chemotherapy offers little to no benefit to esophageal cancer patients if their tumors are not tested for genotypic abnormalities or oncoprotein overexpression [43]. A clinical trial presented at the Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium in 2014, yet ultimately went unpublished, postulated that the addition of EGFR targeted therapy cetuximab to chemotherapy and radiation regimens would increase two-year survival by 12% [44]. This unpublished study revealed that out of 344 patients with both types of esophageal cancer, about 80% were considered advanced stage disease (T3/T4) while 20% had early stage EC (T1/T2) [44]. In this unpublished phase 3 clinical trial, the difference in overall survival between the targeted and non-targeted therapy cohorts were not significant. The complete response rate at two years was also established to be not significant [44]. Again, a targeted therapy that directly inhibits EGFR failed to improve overall survival and response rates in gastroesophageal cancer patients that were not preemptively screened for EGFR overexpression. Tumor biopsies were not tested for EGFR expression in this study. How could it be surmised that a tumor not utilizing EGFR for proliferation would respond to an EGFR inhibitor – on top of knowing that only 32% of gastroesophageal junction cancers express EGFR [45]? Had this clinical trial utilized EGFR molecular diagnostics before therapy, and placed patients in the various arms accordingly, the investigators may have seen significant results and most likely would have gone on to publish this study.

Targeting the extracellular receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-2 (HER2) transformed breast cancer therapy dramatically over the last 15 years when it was discovered that blocking the growth factor receptor with monoclonal antibodies demonstrated inhibition of tumor progression and metastases. It was found that some esophageal cancers also exhibit an overexpression of HER2 [46]. Therefore, anti-HER2 therapy in esophageal cancer is sparingly utilized as an off-label option and is also under investigation through clinical trials with the hope of seeing improvement in drug response similar to breast cancer.

It has also been demonstrated that a sustained response to trastuzumab correlates with the level of HER2 protein in gastro-esophageal cancer [47]. A retroactive investigation revealed high variability among patients with immunohistochemistry 3+ HER2 when absolute quantities of HER2 protein were measured with the sensitivity of mass spectrometry which can quantitate oncoproteins at the attomole/μg level. In this study, a predictive cutoff value of 2383.3 amol/μg was selected within all of the patients who were scored 3+ via IHC for HER2 protein in gastroesophageal cancers [47]. Patients with HER2 protein levels above the cutoff experienced prolonged overall survival as compared to patients with HER2 levels below the cutoff. This study is a compelling example highlighting the importance of knowing both the qualitative presence and qualitative amounts of drug targets in the tumor. Studies are beginning to demonstrate that the higher the target concentration, the more effective the drug will be. Clinical utility can also be gleaned from oncoprotein quantification as patients placed on targeted therapies that possess lower target protein levels may require additional follow-up to monitor their therapeutic response more carefully.

4.0 The Philosophy of Cancer Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy has become a progressive therapeutic tactic that many medical oncologists are adding to their arsenal of drug options. There have been numerous clinical trials demonstrating overall survival advantages in patients with late-stage melanoma, genitourinary cancers, non-small cell lung carcinoma, and triple negative breast cancer [48–50]. Esophageal carcinoma could also potentially benefit from this new pillar of anti-cancer therapy. PD-L1 (programmed death-ligand 1) is a biomarker that can be expressed in solid tumors. It is a docking station for the protein PD1 which is expressed on T-cells and has the function of identifying other cells in the body as “self” [51].

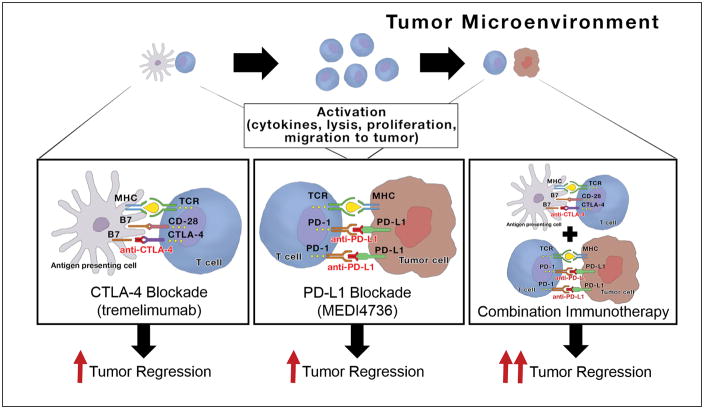

Because of immune defense mechanisms, antigen presenting cells (APCs) routinely scan an individual’s body for foreign molecules. When APCs signal T-cells to attack an antigen, such an attack will be avoided if the antigen (tumor) expresses PD-L1. When the PD1 protein on a T-cell connects with the PD-L1 ligand on a tumor, it allows the tumor to remain unscathed by host defenses. Presumably by blocking PD-L1 on a tumor, T-cells that come across the cancerous lesion go unhindered in activating the immune system against the tumor cells (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Utilizing combination immunotherapy could be an aggressive approach enabling improved survival rates in esophageal cancer patients by stimulating the immune system to halt erratic cell proliferation via two mechanisms of action rather than one [51,52]. The frame on the left demonstrates immune system activation via CTLA-4 blockade with drugs like tremelimumab where inhibition of the B7 ligand on the antigen presenting cell (APC) causes T-cells to proliferate and migrate toward the tumor. The center frame shows that once T-cells are signaled to target antigens like a tumor – that blocking PD-L1 (with drugs like MEDI4736) will allow T-cells to engage in a fight with the tumor cells by inhibiting a connection to PD-1 which is expressed on the T-lymphocyte. If PD-L1 is left unadulterated then the T-cell will recognize the tumor as “self” and be diverted from destructing the cancer. The far right frame shows that utilizing both mechanisms of action as a combination therapy has produced more robust tumor regressions in early clinical trials, which gives optimism to medical oncologists. CTLA4 – cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4; PD-L1 – program death-ligand 1.

Another route in which immunotherapy drugs may stimulate the immune system is by utilizing antagonists targeting T-cells, irrespective of PD-L1 expression on a tumor. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) is expressed on the surface of helper T cells and binds to CD86 and CD80 on antigen-presenting cells transmitting an inhibitory signal to T-cells [52]. Investigators are increasing their efforts in exploring the potential anti-tumor benefits of blocking CTLA-4 via antagonistic antibodies such as ipilimumab (FDA approved for melanoma in 2011). CTLA-4 blockade has demonstrated an inhibitory effect on the immune system’s tolerance to tumors and has opened another exciting avenue to a potentially useful immunotherapy strategy for cancer patients regardless of their PD-L1 status. Another anti-CTLA-4 therapy (not yet FDA approved) is tremelimumab.

Immunotherapy is like a “software update” to your immune system. By blocking PD-L1 on the surface of tumor cells, dormant T-cells waiting to defend your body will be reprogrammed to activate and attack the PD-L1-inhibited tumor(s). Adding a CTLA-4 antagonist as a combination therapy could foster an immune response to cancer if the tumor is not utilizing PD-L1 to avoid death by T-cells (Figure 4).

4.1 Past Clinical Trials: Combination Therapy vs. Monotherapy for EC

The foundation for combining two immunotherapy drugs is rooted in the fact that CTLA-4 and PD-L1 are characterized by separate yet complementary pathways that negatively regulate anti-tumor defense. Preclinical and phase I and II trials have reliably demonstrated better patient results (including response, complete response, and survival) with combination immunotherapy versus monotherapy alone [53].

Two drugs showing promise as combination checkpoint inhibitors are MEDI4736 (anti-PD-L1) and tremelimumab (anti-CTLA-4). MEDI4736 possesses a monoclonal antibody with antagonistic properties against programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1). MEDI4736 blocks the interaction between PD-L1 with the PD-1 (CD80) molecules, and enhancing T-cell activation and inhibiting immune defense avoidance [54]. Tremelimumab is also a fully human monoclonal antibody that targets and blocks the CTLA-4 ligand expressed on T-cells [55]. Treatment with the combination of anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-L1 agents have shown significant anti-tumor effects in several malignancies (Figure 4).

Combination immunotherapy targeting two avenues of immune-checkpoint activity, such as PD-L1 and CTLA-4, has demonstrated better response rates in patients receiving single-checkpoint targeted therapy [56]. PD-L1 blocking agents have demonstrated less toxicity than previous immunotherapy options like anti-interleukin 2 (IL-2) drugs [56].

MEDI4736 and tremelimumab when administered independently exhibited dose-proportional pharmacokinetic (PK) exposures and were in line with other monotherapy studies. Low incidence of ADA (immune deficiency) was observed in preclinical studies with both drugs, and complete soluble PD-L1 suppression was observed throughout the dosing interval in all subjects [57]. Clinical trials have shown that simultaneous immune-checkpoint blockade induces durable cancer regression. In metastatic melanoma, approximately 10% of patients treated with tremelimumab monotherapy demonstrated a therapeutic response lasting beyond five years [58].

Adding an immunotherapy regimen would not be too cumbersome on esophageal cancer patients due to the following reasons:

MEDI4736 – 1 hr infusions (10 mg/kg) every 14 days (Terminal half-life of MEDI4736 is 23 days, so infusion intervals may extend soon) [59].

Tremelimumab – 1 hr infusions (15 mg/kg) every 90 days [60].

Low incidence of adverse events [30].

For patients on second or third line therapy for EC, the low maintenance requirement of biweekly and trimonthly infusions for a patient under physical and psychological stress would be a beneficial aspect of this immunotherapy regimen, on top of the low likelihood of adverse events. There is also benefit from an efficacy standpoint in the event a patient’s tumor does not express PD-L1, this combo therapy could still be effective in stimulating an immune response to cancer via CTLA-4 blockade with tremelimumab. There have been a number of publications demonstrating better efficacy of combination therapy compared to mono-immunotherapy. The beneficial effects include smaller tumor volumes in mice models and improved overall survival in human clinical trials [61–64].

The CheckMate 067 trial tested if dual immunotherapy agents would outperform single agent check-point inhibition in patients with advanced melanoma. At the 2015 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) meeting, investigators reported that combination immunotherapy using nivolumab (anti-PD1) and ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4) doubled the length of progression-free survival (PFS) compared with ipilimumab alone. In his findings of the study, Dr. Wolchok stated: “Based upon the available evidence, the combination represents a means to improve outcomes, versus [anti-PD1 therapy] alone, particularly for patients whose tumors have <5% PD-L1 expression” [53].

Importantly, the CheckMate 067 study demonstrated that the patients who expressed PD-L1 gained essentially as much benefit from single-agent anti-PD1 therapy as from the combination of anti-PD1 and anti-CTLA-4 therapy [53]. This validates the prognostic value of knowing the expression of PD-L1 (among other relevant biomarkers) before deciding management strategies for a patient with EC.

Pharmacokinetics also comes into play from a personalized medicine standpoint as studies are looking into individual patient drug clearance rates versus survival statistics. Interestingly, the median overall survival for the patients in the fast-clearance group (n=147) was 9.6 months compared to 15.8 months for the slow-clearance cohort (n=146), suggesting that the patients who clear immunotherapy drugs faster from their body have shorter survival periods [65]. These results are intriguing and could potentially bring individual patient clearance rates into personalized medicine algorithms along with genomics and proteomics. Nevertheless, combination immunotherapy may have enough of a powerful effect to improve therapeutic response in patients with aggressive esophageal cancer.

4.2 Current Immunotherapy Clinical Trials in EC

An indication that there is a lack of agreement for the optimum perioperative treatment of EC is revealed by the number of ongoing clinical trials utilizing immunotherapy in gastroesophageal cancers. This reflects the need for a novel approach to giving esophageal cancer patients a chance at improved outcomes via immunotherapy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Ongoing clinical trials utilizing targeted immunotherapy in esophageal cancers [81].

| Clinical Trial | Phase | Indication | Drug | Target | Purpose | Completion Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT02625610 | 3 | First-Line Gastric Cancer | Avelumab | PD-L1 | Avelumab versus continuation of first-line chemotherapy. | 11/1/2023 |

| NCT02564263 | 3 | Advanced Esophageal Carcinoma | pembrolizumab | PD-L1 | Pembrolizumab vs physicians’ choice of single agent Docetaxel, Paclitaxel, or Irinotecan that have progressed after first-line standard therapy | 5/1/2018 |

| NCT02370498 | 3 | Advanced Gastro-Esophageal Carcinoma | pembrolizumab | PD-L1 | Pembrolizumab Versus Paclitaxel for Participants That Progressed After Therapy With Platinum and Fluoropyrimidine | 2/1/2018 |

| NCT02625623 | 3 | Gastroesophageal Adenocarcinoma | Avelumab | PD-L1 | Avelumab as a Third-line Treatment of Unresectable, Recurrent, or Metastatic Gastroesophageal Junction Adenocarcinoma | 1/1/2023 |

| NCT02639065 | 2 | Esophageal Cancer | MEDI4736 | PD-L1 | Safety and Efficacy of MEDI4736 following multi-modality therapy | 3/1/2019 |

| NCT02559687 | 2 | Advanced Esophageal Carcinoma | pembrolizumab | PD-L1 | Pembrolizumab Monotherapy in Third-line Previously Treated Subjects | 7/1/2017 |

| NCT02589496 | 2 | Gastroesophageal Adenocarcinoma | pembrolizumab | PD-L1 | Pembrolizumab who Progressed After First-Line Therapy With Platinum and Fluoropyrimidine | 12/1/2017 |

| NCT02335411 | 2 | Gastroesophageal Junction Cancer | pembrolizumab | PD-L1 | Pembro monotherapy, previously treated or Pembro combination therapy (+5FU or Cisplatin), treatment naïve or Pembro monotherapy, treatment naïve. | 10/1/2018 |

| NCT02340975 | 1b/2 | Gastroesophageal Adenocarcinoma | MEDI4736 + tremelimumab | PD-L1 + CTLA4 | MEDI4736 in Combination With Tremelimumab, MEDI4736 Monotherapy, and Tremelimumab Monotherapy | 11/1/2017 |

| NCT02689284 | 1b/2 | Gastroesophageal Junction Cancer | Margetuximab + Pembrolizumab | PD-L1 + HER2 | Safety and activity of margetuximab and pembrolizumab combination treatment in patients with HER2+ gastroesophageal junction cancer. | 3/1/2020 |

| NCT02572687 | 1 | Gastroesophageal Junction adenocarcinoma | Ramucirumab + MEDI4736 | PD-L1 + VEGF | Evaluate the safety of ramucirumab plus MEDI4736 in participants with locally advanced and unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma. | 8/1/2017 |

| NCT02658214 | 1 | Solid Tumors | MEDI4736 + tremelimumab + Chemotherapy | PD-L1 + CTLA4 | A Phase Ib Study to Evaluate the Safety and tolerability of MEDI4736 & Tremelimumab in combination with 1st-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced solid tumors | 4/1/2018 |

Out of all clinical trials, investigation NCT02340975 (shown in red in Table 2) has high potential to benefit esophageal adenocarcinoma patients directly as drugs MEDI4736 and tremelimumab would bring a double edged sword to the table, stimulating the immune system to attack cancer with or without the expression of PD-L1 in the tumor. Because the dual-therapy in this trial exploits two adaptive immune pathways, improved clinical outcomes are still possible because tremelimumab would block CTLA-4 to stimulate the immune system to join the fight against the patient’s cancer even if MEDI4736 is not entirely effective if the patient’s tumor does not express PD-L1.

Investigation NCT02658214 (shown in red in Table 2) spurs much interest as it will be interesting to see how patients with various solid tumor types respond to combo immunotherapy while on incremental chemotherapy. That may be the aggressive approach medical oncologists have been waiting for, or it may reveal that creating a hyperactive immune system in neutropenic patients could produce insurmountable adverse events. Regardless, many of the clinical trials shown in Table 2 could potentially aid in attaining FDA approval for immunotherapy in EC.

4.3 Is the Primary Immunotherapy Target (PD-L1) Present in Esophageal Tumors?

MEDI4736 blocks PD-L1 on the tumor cell surface and tremelimumab blocks CTLA-4 on the T-cell to signal the immune system to attack cancer. The non-redundant inhibitory mechanisms utilized by MEDI4736 and tremelimumab have demonstrated a combined effect in preclinical studies [66]. A 2015 ASCO presentation revealed that this combination of drugs has great potential for cancer therapy: “Because the agents block distinct processes involved in immunosuppression, the combination might provide greater antitumor activity as compared with monotherapy with either agent” [67]. But is PD-L1 expressed in esophageal cancer? According to a recent study, the occurrence of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) overexpression is around 40% in gastroesophageal cancers confirming the presence of the target for these drugs in esophageal cancers [68]. Therefore, it should be emphasized that knowing the PD-L1 status of an esophageal tumor at the time of diagnosis is relevant and possesses clinical value.

Expression of PD-L1 on a tumor biopsy is a good predictor of a patient’s response to a number of immunotherapy agents [56]. A Phase I study split bladder cancer patients into two groups of PD-L1-positive (IHC score of +2 and +3) and PD-L1-negative. Patients who expressed PD-L1 had a response rate of 46 percent compared to 15 percent of those with no PD-L1 expression. PD-L1 positive patients also had progression-free survival (PFS) that was four months longer than those without PD-L1 in their tumors [69,70]. A Phase II study administered anti-PD-L1 therapy in 143 patients with unknown PD-L1 statuses. In this larger cohort, there was only a 15 percent response rate with a 2.7 month progression-free survival [71]. There is no compelling reason not to screen patients for PD-L1 expression to have a better idea of which groups of patients will benefit the most from these very expensive drugs.

5.0 Conclusions

It is apparent that esophageal cancer would be a sustainable candidate for the cutting-edge immunotherapy that has brought promise to the oncology arena over the last five years. PD-L1 is a protein (ligand) used by tumors like a disguise allowing the cancerous cells to go undetected by the immune system. Two immunotherapy drugs showing great promise as a combination therapy regimen are MEDI4736 and tremelimumab, which would yield an efficient immune response to cancer in a patient via two separate mechanisms (Figure 4).

Esophageal cancer patients warrant increased proteomic analysis to inform oncologists which biomarkers are driving their patient’s tumors, and which proteomic molecules in their tumors will cause resistance to various classes of chemotherapy [72]. Interpatient heterogeneity makes optimal esophageal cancer treatment unpredictable because patient tumors can express (or not express) differing levels of proteomic biomarkers which has an effect on first-line therapy. Consequently, patient management strategies for EC can sometimes appear to be semi-arbitrary and hopefully a more robust diagnostic panel will provide a clearer picture on how to augment the primary medical intervention.

Immunotherapy has demonstrated anti-tumor activity in many solid tumors, and combination therapy may pack a needed larger “punch” in these patients compared to monotherapy. MEDI4736 and tremelimumab are relatively safe drugs with very low maintenance, and it will be interesting to see if metronomic dosing of chemotherapy will be tolerated in concert with the immunotherapy in Clinical Trial NCT02658214. It has been concluded that MEDI4736 + Tremelimumab should be ‘fast-tracked’ for treatment of esophageal cancer if the highlighted clinical trials are deemed safe and successful after peer review. There is also a clear need for a greater utilization of molecular diagnostics for patients with esophageal cancer to match proteomic expression levels of oncology-relevant targets with their corresponding therapy (Figure 3).

6.0 Expert Commentary

With the emergence of immunotherapy and privatized molecular diagnostic companies, medical oncologists will have more information on the biology of their patient’s tumor and a more comprehensive arsenal than just taxanes and platinum-based chemotherapies for treating esophageal cancer. Molecular diagnostic companies on both coasts in the United States have developed high-throughput assays that can give an incredible amount of information on the genomic and proteomic makeup of solid tumors whether using IHC, next-generation sequencing, mass spectrometry, RNAseq, whole genome sequencing, as well as a few other platforms.

In the United States, cancer diagnostics and therapy has been a recurring topic on primetime news within the last few years. CEOs of biotechnology companies as well as key members of the National Institute of Health have touched on these subjects on many major news networks. There is one key word that stands out in all of these interviews – ‘genomics’. Assuredly, the viewers at home can probably connect the dots to realize that our genetic disposition has an effect on which cancers we get and how to treat these cancers based upon the genome of the tumors themselves. However, much of the information we can get from genomic profiling via next-gen sequencing is not clinically applicable today. For instance, a commercial diagnostics company offers a solid tumor diagnostics test that analyses the mutational status of over 300 oncogenes. Of those hundreds of genes only a few have off-label clinical utility for esophageal cancer today (eg. KRAS for EGFR inhibitors). Some diagnostic companies are also offering whole genome sequencing in an effort to optimize first-line therapy in a number of cancers. Although these platforms are exciting and yield massive amounts of information about one’s cancer, there are not many data points a medical oncologist can act on with the results of these kinds of tests. So having the layout of all 3 billion base pairs in a given patient does not yet provide a clear route to compiling effective patient management strategies.

Even though the technology is improving exponentially in the cancer diagnostic arena, the most useful assays that could predict response to various anti-cancer therapies would be in the proteomic arena. Of the 12 FDA-approved therapies in esophageal adenocarcinoma, zero of them target the genome. A majority of the drugs either target or are effected by proteomic expression. For most patients with oncogenic mutations, there is not a corresponding drug that can be readily prescribed. And because esophageal cancer is so deadly, it is important to get the most relevant information that is useful with current technology so these patients can have the best chance at a durable response to first-line chemotherapy today. So why the need to analyze 300+ genes? Or map 3 billion base pairs? Or analyze the RNA of the tumor (which is a surrogate for proteomic expression)? Esophageal cancer therapy could be optimized with simple IHC in-house or outsourced multiplexed mass spec diagnostic tests looking at a panel of proteins that pertains to the drugs that are FDA approved or in clinical trial right now. Yes, those robust diagnostic platforms are important for the future of medical oncology, but many of them are not yet ready for prime-time.

7.0 Five-year View

Assuredly in the next five years we will see the needle move in the right direction for esophageal cancer survival. CAR (Chimeric Antigen Receptor) immunotherapy technology is also around the corner to potentially improve survival outcomes in many solid tumor indications. CAR immunotherapy technology yields more potent, or supercharged T-cells that have a specific affinity for an individual patient’s tumor [73].

Another exciting avenue for halting solid tumor pathogenesis is emerging nanotechnology specifically targeting a patient’s tumor cells. Inspired by how plants use porphyrins to do photosynthesis, colorful porphyrins self-assemble into biodegradable nanoparticles called porphysomes, which target the folate receptor expressed in cancer [74]. The now-colored tumors can absorb laser light, heating and killing the tumor, and sparing healthy cells. This technology is garnering much attention and should be ready for human clinical trials in the next two years.

DNA and RNA sequencing will eventually play a huge factor in the prescription of immunotherapy in esophageal cancer patients. Genetic panels that are currently in development will be able to analyze a tumor’s immune composition and activity, mutational load, surrogate markers, escape mechanisms, and tumor-extrinsic factors such as polymorphisms in the targeted biomarkers [75]. Soon patients will be matched with the best choice of immunotherapy based upon multiple genetic factors which should improve survival rates for some of the field’s toughest cases.

Lastly, groups are researching whether the magnitude of intra-tumor heterogeneity in a patient’s cancer is a predictor of their outcome. In a recent study, investigators developed new methods to reconstruct phylogenies using copy number profiles and hypothesized that resistance to anti-cancer therapy could be linked to the tumor’s level of genetic heterogeneity [76]. Data shows that the more heterogeneous a tumor is, the higher the likelihood that the patient becomes resistant to therapeutics, identifying what could explain why anti-cancer drugs become ineffective after some time [76]. Taken together, an improved understanding of tumor biology and new therapeutic avenues may be available to esophageal cancer patients in the next five years.

Key issues.

Esophageal cancer is a highly aggressive neoplasm that has a median overall survival of just 13 months and has seen very little improvement in survival statistics in the last four decades compared to other major cancers.

There are 12 FDA approved drugs for esophageal cancer, nine of which have a companion proteomic biomarker associated with chemotherapy resistance or increased benefit.

Robust proteomic scrutiny of esophageal tumors via molecular diagnostics to optimize first-line therapy should be utilized.

Proteomic analysis of HER2, EGFR, PD-L1, ERCC1, TUBB3, TOPO-I, and TOPO2A would help optimize first-line treatment plans for patients with esophageal cancer. Currently, HER2 proteomic analysis is the only biomarker consistently ordered in this indication.

PD-L1 is expressed in 40% of gastroesophageal cancers; therefore, anti-PD-L1 therapy in combination with anti-CTLA-4 immunotherapy would pack a large enough punch to potentially improve survival outcomes for esophageal cancer patients.

Clinical trials applying combination immunotherapy should be encouraged for esophageal cancer patients, especially if their tumors express PD-L1, harnessing the power of a patient’s immune system to combat their disease.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by research grants R01 HL112597, R01 HL116042, and R01 HL120659 to Dr. D.K. Agrawal from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, USA. The content of this review article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

K Agrawal has received research grants R01 HL112597, R01 HL116042, and R01 HL120659 to Dr. D.K. Agrawal from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, USA. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

References

* Article of interest

** Article of considerable interest

- 1.Debnath M, Prasad GBKS, Bisen PS. Molecular Diagnostics: Promises and Possibilities. Springer; Netherlands, Dordrecht: 2010. Segments of Molecular Diagnostics – Market Place [Internet] pp. 503–513. [cited 2016 May 11]. Available from: http://www.springerlink.com/index/10.1007/978-90-481-3261-4_30. [Google Scholar]

- 2*.Hughes MD. Molecular Diagnostics Market Trends and Outlook. This article is a future projection for the molecular diagnostic market and displays the growing market trends of the cancer diagnostic arena as doctors are steadily increasing their use of outsources cancer assays around the globe. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trowbridge R, Sharma P, Hunter WJ, Agrawal DK. Vitamin D receptor expression and neoadjuvant therapy in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Exp Mol Pathol [Internet] 2012;93(1):147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2012.04.018. Available from: <Go to ISI>://WOS:000305924000019\n http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0014480012000639/1-s2.0-S0014480012000639-main.pdf?_tid=abd622aa-c998-11e3-8904-00000aacb362&acdnat=1398114510_84a87107fb031020063190144ec62d7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kapoor H, Agrawal DK, Mittal SK. Barrett’s esophagus: Recent insights into pathogenesis and cellular ontogeny. Transl Res. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guimbaud R, Hospitalier C. J OURNAL OF C LINICAL O NCOLOGY. 2016 Prospective, Randomized, Multicenter, Phase III Study of Fluorouracil, Leucovorin, and Irinotecan Versus Epirubicin, Cisplatin, and Capecitabine in Advanced Gastric Adenocarcinoma: A French Intergroup ( Fédération F. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi N, Iwasa S, Sasaki Y, et al. Serum levels of soluble programmed cell death ligand 1 as a prognostic factor on the first-line treatment of metastatic or recurrent gastric cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol [Internet] 2016;142(8):1727–1738. doi: 10.1007/s00432-016-2184-6. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00432-016-2184-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qin T, Zeng Y, Qin G, et al. High PD-L1 expression was associated with poor prognosis in 870 Chinese patients with breast cancer. Oncotarget [Internet] 2015;6(32):33972–81. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5583. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26378017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kapoor H, Lohani KR, Lee TH, Agrawal DK, Mittal SK. Animal Models of Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma-Past, Present, and Future. Clin Transl Sci [Internet] 2015;8(6):841–847. doi: 10.1111/cts.12304. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/cts.12304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9*.Brown LM, Devesa SS, Chow WH. Incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus among white Americans by sex, stage, and age. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(16):1184–1187. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn211. This article provides analysis for the increasing rate of incidence of esophageal cancer in the United States. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blot WJ, McLaughlin JK. The Changing Epidemiology of Esophageal Cancer. Semin Oncol [Internet] 1999;26(5 Suppl 15):2–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10566604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kubo A, Corley DA. Marked Multi-Ethnic Variation of Esophageal and Gastric Cardia Carcinomas within the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(4):582–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12*.McLarty AJ, Deschamps C, Trastek VF, Allen MS, Pairolero PC, Harmsen WS. Esophageal resection for cancer of the esophagus: Long-term function and quality of life. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63(6):1568–1572. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)00125-2. This article describes the clinical facets of esophectomies which is a method of treating esophageal cancer before or after medical oncology intervention. This provides supporting evidence that medical intervention outside of surgery alone should be utilized when treating EAC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmassmann A, Oldendorf MG, Gebbers JO. Changing incidence of gastric and oesophageal cancer subtypes in central Switzerland between 1982 and 2007. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24(10):603–609. doi: 10.1007/s10654-009-9379-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14**.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2011. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2014. [Google Scholar]; SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2011 [Internet] Natl. Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2013. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2011/This report gives a shocking view of the dire circumstances that comes with an esophageal cancer diagnosis. This report details survival rates and statistics for patients diagnoses with EAC and hammers home the need for a new approach to treating this disease. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trowbridge R, Mittal SK, Agrawal DK. Vitamin D and the epidemiology of upper gastrointestinal cancers: a critical analysis of the current evidence. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet] 2013;22(6):1007–14. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0085. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3681828&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J, Zhang X-H, Ge J, Yang C-M, Liu J-Y, Zhao S-L. Endoscopic submucosal dissection vs endoscopic mucosal resection for colorectal tumors: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol [Internet] 2014;20(25):8282–7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i25.8282. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25009404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sehdev A, Catenacci DVT. Perioperative therapy for locally advanced gastroesophageal cancer: current controversies and consensus of care. J Hematol Oncol [Internet] 2013;6(1):66. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-6-66. Available from: http://www.jhoonline.org/content/6/1/66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18**.Fountzilas G, Valavanis C, Kotoula V, et al. HER2 and TOP2A in high-risk early breast cancer patients treated with adjuvant epirubicin-based dose-dense sequential chemotherapy. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-10. This article demonstrates that solid tumors that express TOPO2A have a more robust clinical response to anthracyclines. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19**.Olaussen KA, Dunant A, Fouret P, et al. DNA repair by ERCC1 in non-small-cell lung cancer and cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(10):983–991. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060570. ERCC1, or excision repair cross-complementation group 1, is a major protein involved in the nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway. NER is a DNA repair mechanism necessary for the repair of DNA damage from platinum agents. Tumors with low expression of ERCC1 have impaired NER capacity and may be more sensitive to platinum agents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20**.Bepler G, Williams C, Schell MJ, et al. Randomized international phase III trial of ERCC1 and RRM1 expression-based chemotherapy versus gemcitabine/carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(19):2404–2412. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.9783. This article demonstrates that solid tumors that express ERCC1 will have a lack of potential benefit and a limited clinical response when using platinum-based chemotherapy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henkel J. FDA.gov. FDA Consum. 2005;39:39. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cancer Research UK. CancerStats: Cancer Statistics for the UK. 2012 Online Source. www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/ [Internet] Available from: http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/

- 23**.Yang Y-L, Luo X-P, Xian L, et al. The Prognostic Role of the Class III β-Tubulin in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Patients Receiving the Taxane/Vinorebine-Based Chemotherapy: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One [Internet] 2014;9(4):e93997. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093997. Available from: http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0093997In this article TUBB3 is described as a microtubule protein that is implicated in resistance to taxane-based therapies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braun MS, Richman SD, Quirke P, et al. Predictive biomarkers of chemotherapy efficacy in colorectal cancer: Results from the UK MRC FOCUS trial. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(16):2690–2698. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.5580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25**.Arriola E, Rodriguez-Pinilla SM, Lambros MBK, et al. Topoisomerase II alpha amplification may predict benefit from adjuvant anthracyclines in HER2 positive early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;106(2):181–189. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9492-5. This article describes TOPO2A as an enzyme that alters the supercoiling of doublestranded DNA during cell division. High TOPO2A protein expression has been associated with benefit from anthracycline-based chemotherapy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Laurentiis M, Cancello G, Zinno L, et al. Targeting HER2 as a therapeutic strategy for breast cancer: A paradigmatic shift of drug development in oncology. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(SUPPL 4) doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27**.Pirker R, Pereira JR, von Pawel J, et al. EGFR expression as a predictor of survival for first-line chemotherapy plus cetuximab in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: analysis of data from the phase 3 FLEX study. Lancet Oncol [Internet] 2012;13(1):33–42. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70318-7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22056021Tumors overexpressing the EGFR protein are reported to have an improved response to anti-EGFR therapies. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28*.Nabholtz JM, Abrial C, Mouret-Reynier MA, et al. Multicentric neoadjuvant phase II study of panitumumab combined with an anthracycline/taxane-based chemotherapy in operable triple-negative breast cancer: identification of biologically defined signatures predicting treatment impact. Ann Oncol [Internet] 2014;25(8):1570–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu183. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24827135Therapies targeting both wild-type and mutated EGFR are approved for many solid tumor indication and tyrosine kinase inhibitors have been associated with improved benefit when tumors overexpress the EGFR protein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29**.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQM, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med [Internet] 2012;366(26):2455–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3563263&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstractTumors that express the PD-L1 protein can activate the T-cell localized PD-1 receptor to evade immune system mediated cell death. PD-L1 expression has been associated with response to both PD-L1 and PD-1 targeted therapies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med [Internet] 2012;366(26):2443–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3544539&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31*.Topalian SL, Drake CG, Pardoll DM. Targeting the PD-1/B7-H1(PD-L1) pathway to activate anti-tumor immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24(2):207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.12.009. This paper further demonstrates that PD-L1 expression has been associated with response to both PD-L1 and PD-1 targeted therapies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sparano JA, Gray RJ, Makower DF, et al. Prospective Validation of a 21-Gene Expression Assay in Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med [Internet] 2015;373(21):2005–2014. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510764. Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1510764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nuciforo P, Thyparambil S, Aura C, et al. High HER2 protein levels correlate with increased survival in breast cancer patients treated with anti-HER2 therapy. Mol Oncol [Internet] 2016;10(1):138–47. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.09.002. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26422389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waddell T, Chau I, Cunningham D, et al. Epirubicin, oxaliplatin, and capecitabine with or without panitumumab for patients with previously untreated advanced oesophagogastric cancer (REAL3): a randomised, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol [Internet] 2013;14(6):481–9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70096-2. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23594787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35*.Lordick F, Kang Y-K, Chung H-C, et al. Capecitabine and cisplatin with or without cetuximab for patients with previously untreated advanced gastric cancer (EXPAND): a randomised, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol [Internet] 2013;14(6):490–9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70102-5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23594786This article demonstrates that the clinical trials that don’t screen for proteomic targets yield poor results as it was unknown whether the biomarker EGFR was present in these patients receiving TKI therapy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohtsu A, Ajani JA, Bai Y-X, et al. Everolimus for Previously Treated Advanced Gastric Cancer: Results of the Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase III GRANITE-1 Study. J Clin Oncol [Internet] 2013;31(31):3935–3943. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.3552. Available from: http://jco.ascopubs.org/cgi/doi/10.1200/JCO.2012.48.3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Catenacci DVT. Next-generation clinical trials: Novel strategies to address the challenge of tumor molecular heterogeneity. Mol Oncol [Internet] 2015;9(5):967–996. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.09.011. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S157478911400235X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen DJ, Christos PJ, Kindler HL, et al. Vismodegib (V), a hedgehog (HH) pathway inhibitor, combined with FOLFOX for first-line therapy of patients (pts) with advanced gastric and gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) carcinoma: A New York Cancer Consortium led phase II randomized study. ASCO Meet Abstr. 2013;31(15_suppl):4011. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang L, Yang J, Cai J, et al. A subset of gastric cancers with EGFR amplification and overexpression respond to cetuximab therapy. Sci Rep [Internet] 2013;3:2992. doi: 10.1038/srep02992. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24141978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hedner C, Borg D, Nodin B, Karnevi E, Jirström K, Eberhard J. Expression and Prognostic Significance of Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptors 1 and 3 in Gastric and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. PLoS One [Internet] 2016;11(2):e0148101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148101. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26844548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagaraja V, Eslick GD. HER2 expression in gastric and oesophageal cancer: a meta-analytic review. J Gastrointest Oncol [Internet] 2015;6(2):143–54. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2014.107. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25830034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bang Y-J, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9742):687–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61121-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tian X, Zhou J-G, Zeng Z, et al. Cetuximab in patients with esophageal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Med Oncol [Internet] 2015;32(4):127. doi: 10.1007/s12032-015-0521-2. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s12032-015-0521-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suntharalingam M, Winter K, Ilson DH, et al. The initial report of RTOG 0436: A phase III trial evaluating the addition of cetuximab to paclitaxel, cisplatin, and radiation for patients with esophageal cancer treated without surgery. ASCO Meet Abstr. 2014;32(3_suppl):LBA6. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang KL, Wu T-T, Choi IS, et al. Expression of epidermal growth factor receptor in esophageal and esophagogastric junction adenocarcinomas. Cancer [Internet] 2007;109(4):658–667. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22445. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/cncr.22445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woo J, Cohen SA, Grim JE. Targeted therapy in gastroesophageal cancers: past, present and future. Gastroenterol Rep [Internet] 2015:gov052. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gov052. Available from: http://gastro.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2015/10/27/gastro.gov052.full. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47*.Ock C-Y, An E, Oh D-Y, et al. Quantitative measurement of HER2 levels by multiplexed mass spectrometry to predict survival in gastric cancer patients treated with trastuzumab. ASCO Meet Abstr. 2015;33(15_suppl):4050. This article demonstrates that quantitative molecular diagnostic data can be even more prognostic than immunohistochemistry showing the importance of knowing not only if the drug target is present but how much of the biomarker is expressed in the tumor. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gibson J. Anti-PD-L1 for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(6) doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grossman HB, Lamm DL, Kamat AM, Keefe S, Taylor JA, Ingersoll MA. Innovation in Bladder Cancer Immunotherapy. J Immunother [Internet] 2016 doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000130. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27428265. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Ratta R, Zappasodi R, Raggi D, et al. Immunotherapy advances in uro-genital malignancies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taube JM, Klein A, Brahmer JR, et al. Association of PD-1, PD-1 ligands, and other features of the tumor immune microenvironment with response to anti-PD-1 therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(19):5064–5074. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Magistrelli G, Jeannin P, Herbault N, et al. A soluble form of CTLA-4 generated by alternative splicing is expressed by nonstimulated human T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29(11):3596–3602. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199911)29:11<3596::AID-IMMU3596>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Doyle C. Combination Immunotherapy Superior to Monotherapy in Patients with Melanoma. Am Heal drug benefits [Internet] 2015;8(Spec Issue):41. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26380628. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Segal Neil Howard, Antonia Scott Joseph, Julie R. Brahmer, Michele Maio, Andy Blake-Haskins, Xia Li, Jim Vasselli, Ramy A. Ibrahim, Jose Lutzky SK. Preliminary data from a multi-arm expansion study of MEDI4736, an anti-PD-L1 antibody. | 2014 ASCO Annual Meeting | Abstracts | Meeting Library [Internet] J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(5s):2014. suppl; abstr 3002. Available from: http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/content/134136-144. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tarhini AA, Kirkwood JM. Tremelimumab (CP-675,206): a fully human anticytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 monoclonal antibody for treatment of patients with advanced cancers. Expert Opin Biol Ther [Internet] 2008;8(10):1583–1593. doi: 10.1517/14712598.8.10.1583. Available from: http://informahealthcare.com/doi/pdfplus/10.1517/14712598.8.10.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mahoney KM, Freeman GJ, McDermott DF. The Next Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitors: PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade in Melanoma. Clin Ther. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Homet Moreno B, Ribas A. Anti-programmed cell death protein-1/ligand-1 therapy in different cancers. Br J Cancer [Internet] 2015;112(9):1421–7. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.124. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25856776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lutzky J. Checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of cutaneous malignant melanoma. Chinese Clin Oncol [Internet] 2014;3(3):30. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3865.2014.05.13. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25841456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fairman D, Narwal R, Liang M, et al. Pharmacokinetics of MEDI4736, a fully human anti-PDL1 monoclonal antibody, in patients with advanced solid tumors. ASCO Meet Abstr. 2014;32(15_suppl):2602. [Google Scholar]

- 60*.Ribas A, Chesney Ja, Gordon MS, et al. Safety profile and pharmacokinetic analyses of the anti-CTLA4 antibody tremelimumab administered as a one hour infusion. J Transl Med [Internet] 2012;10(1):236. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-236. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3543342&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. This article provides pharmacokinetic data demonstrating that embattled esophageal cancer patient’s would be able to manage anti-CTLA4 therapy due to its safety profile and extended half-life. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61**.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab or Monotherapy in Untreated Melanoma. N Engl J Med [Internet] 2015;373(1):23–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504030. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26027431This paper demonstrated that combination immunotherapy yields more robust tumor response than monotherapy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Henricks LM, Schellens JHM, Huitema ADR, Beijnen JH. The use of combinations of monoclonal antibodies in clinical oncology. Cancer Treat Rev [Internet] 2015;41(10):859–867. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.10.008. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0305737215001930\nhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26547132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63*.Dai M, Yip YY, Hellstrom I, Hellstrom KE. Curing mice with large tumors by locally delivering combinations of immunomodulatory antibodies. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(5):1127–1138. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1339. Impressive durable tumor response seen in mice receiving combination immunotherapy. Mice harnessessing solid tumors had a much more robust response when receiving combination immunotherapy compared to a cohort receiving a few monotherapy regimens. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zou W, Wolchok JD, Chen L, et al. PD-L1 (B7-H1) and PD-1 pathway blockade for cancer therapy: Mechanisms, response biomarkers, and combinations. Sci Transl Med [Internet] 2016;8(328):328rv4. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad7118. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26936508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang E, Kang D, Bae K-S, Marshall MA, Pavlov D, Parivar K. Population Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Analysis of Tremelimumab in Patients With Metastatic Melanoma. J Clin Pharmacol. 2014 doi: 10.1002/jcph.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Garon EB. Current Perspectives in Immunotherapy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:S11–S18. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2015.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Antonia S, Ou S, Khleif S, et al. 1325PCLINICAL ACTIVITY AND SAFETY OF MEDI4736, AN ANTI-PROGRAMMED CELL DEATH-LIGAND 1 (PD-L1) ANTIBODY, IN PATIENTS WITH NON-SMALL CELL LUNG CANCER. Ann Oncol [Internet] 2014;25(suppl 4):iv466–iv466. Available from: http://annonc.oxfordjournals.org/content/25/suppl_4/iv466.1.abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 68**.Raufi AG, Klempner SJ. Immunotherapy for advanced gastric and esophageal cancer: preclinical rationale and ongoing clinical investigations. J Gastrointest Oncol [Internet] 2015;6(5):561–9. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2015.037. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4570917&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstractThis paper answers the important question of whether or not PD-L1 is even expressed in gastro-esophageal tumors in which it demonstrates that 40% of gasto-esophageal tumors express PD-L1 and therefore would be good candidates for immunotherapy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Powles T, Eder JP, Fine GD, et al. MPDL3280A (anti-PD-L1) treatment leads to clinical activity in metastatic bladder cancer. Nature [Internet] 2014;515(7528):558–62. doi: 10.1038/nature13904. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25428503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Petrylak Daniel Peter, Powles Thomas, Bellmunt Joaquim, Braiteh Fadi S, Loriot Yohann, Zambrano Cristina Cruz, Burris Howard A, Kim Joseph W, Teng Siew-leng Melinda, Bruey Jean-Marie, Hegde Priti, Oyewale O, Abidoye NJV. American Society of Clinical Oncology. (Ed.), editor A phase Ia study of MPDL3280A (anti-PDL1): Updated response and survival data in urothelial bladder cancer (UBC). [Internet]. J Clin Oncol; 2015 ASCO Annual Meeting; Chicago, 4501: 2015. suppl; abstr 4501. Available from: http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/content/148074-156. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fehrenbacher L, Spira A, Ballinger M, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel for patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (POPLAR): a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England) [Internet] 2016;387(10030):1837–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00587-0. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26970723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Trowbridge R, Kizer RT, Mittal SK, Agrawal DK. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D in the pathogenesis of Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Expert Rev Clin Immunol [Internet] 2013;9(6):517–533. doi: 10.1586/eci.13.38. Available from: <Go to ISI>://WOS:000319819500010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73*.Shi H, Sun M, Liu L, Wang Z. Chimeric antigen receptor for adoptive immunotherapy of cancer: latest research and future prospects. Mol Cancer [Internet] 2014;13:219. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-219. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4177696&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstractThis paper is a great example of where immunotherapy is going and how it will be improved to enhance patient response in the future. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.de Souza N. One particle to rule them all? Nat Methods [Internet] 2011;8(5):370–371. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0511-370a. Available from: http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/nmeth0511-370a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dijkstra KK, Voabil P, Schumacher TN, Voest EE. Genomics- and Transcriptomics-Based Patient Selection for Cancer Treatment With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Review. JAMA Oncol [Internet] 2016:1–7. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.2214. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27491050. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Schwarz RF, Ng CKY, Cooke SL, et al. Spatial and Temporal Heterogeneity in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer: A Phylogenetic Analysis. PLOS Med [Internet] 2015;12(2):e1001789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001789. Available from: http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77*.Sève P, Dumontet C. Is class III beta-tubulin a predictive factor in patients receiving tubulin-binding agents? Lancet Oncol. 2008 Feb;9:168–175. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70029-9. TUBBIII is a microtubule protein that is implicated in resistance to taxane-based therapies, which is one of the most common classes of drugs prescribed for patients with esophageal cancer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yin M, Yan J, Martinez-Balibrea E, et al. ERCC1 and ERCC2 polymorphisms predict clinical outcomes of oxaliplatin-based chemotherapies in gastric and colorectal cancer: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(6):1632–1640. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Karki R, Mariani M, Andreoli M, et al. βIII-Tubulin: biomarker of taxane resistance or drug target? Expert Opin Ther Targets [Internet] 2013;17(4):461–72. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2013.766170. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23379899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Teicher BA. Next generation topoisomerase I inhibitors: Rationale and biomarker strategies. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75(6):1262–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.U.S. National Institutes of Health. ClinicalTrialsgov [Internet] clinicaltrialsgov. 2013 Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/

- 82*.Silverberg E, Holleb AI. Major Trends in Cancer:25 Year Survey. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet] 1975;25(1):2–7. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.25.1.2. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.3322/canjclin.25.1.2This article served as a timeline for improved overall survival rates over the decades which was utilized in Figure 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]