Abstract

Epigenetic gene silencing of several genes causes different pathological conditions in humans, and DNA methylation has been identified as one of the key mechanisms that underlie this evolutionarily conserved phenomenon associated with developmental and pathological gene regulation. Recent advances in the miRNA technology with high throughput analysis of gene regulation further increased our understanding on the role of miRNAs regulating multiple gene expression. There is increasing evidence supporting that the miRNAs not only regulate gene expression but they also are involved in the hypermethylation of promoter sequences, which cumulatively contributes to the epigenetic gene silencing. Here, we critically evaluated the recent progress on the transcriptional regulation of an important suppressor protein that inhibits cytokine-mediated signaling, SOCS3, whose expression is directly regulated both by promoter methylation and also by microRNAs, affecting its vital cell regulating functions. SOCS3 was identified as a potent inhibitor of Jak/STAT signaling pathway which is frequently upregulated in several pathologies, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, viral infections, and the expression of SOCS3 was inhibited or greatly reduced due to hypermethylation of the CpG islands in its promoter region or suppression of its expression by different microRNAs. Additionally, we discuss key intracellular signaling pathways regulated by SOCS3 involving cellular events, including cell proliferation, cell growth, cell migration and apoptosis. Identification of the pathway intermediates as specific targets would not only aid in the development of novel therapeutic drugs, but, would also assist in developing new treatment strategies that could successfully be employed in combination therapy to target multiple signaling pathways.

Keywords: SOCS3, JAK, STAT, microRNA, methylation, epigenetic regulation, Gene silencing

INTRODUCTION

Epigenetic changes in cells are induced or temporal changes with or without modifications to DNA that do not cause mutations but leads to alterations in the structural, functional, and biochemical properties of the cells. Besides the post-translational modification mechanisms such as acetylation, methylation, ubiquitination, sumoylation, phosphorylation, oxidation and protein-protein interactions, which are key mechanisms that modify the functional and or structural properties of the proteins and regulate their activities, DNA methylation, histone modifications and miRNA mediated transcriptional regulation were also identified as the primary mechanisms which predominantly mediate epigenetic modifications in cells. Besides epigenetic gene regulation that is normally observed during the embryonic and developmental stages, epigenetic silencing of specific genes has been associated with several pathological conditions in humans. In addition, several microRNAs have been recently identified whose role in epigenetic gene regulation is indisputable.

In this article, we discuss epigenetic regulation of an important regulator of cytokine signaling gene SOCS3 (suppressor of cytokine signaling-3), which is vital in regulating essential functions, including cell proliferation, cell survival. SOCS3 is among the eight members of SOCS family of proteins and since its discovery, its role in many human pathological diseases has been reported. These conditions include cardiovascular diseases, different cancer types, immune disorders, inflammatory diseases, type II diabetes, diabetic nephropathy, obesity, asthma, gastrointestinal disorders, neuronal diseases, hepatitis and other viral infections, osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, tuberculosis, erythropoiesis, pregnancy and eczema. Studies on identifying the role of SOCS3 were greatly limited because genetic knockdown of SOCS3 in mice proved to be embryonic lethal as mice die in utero between E11 and E13 with fetal liver erythrocytosis and placental defects during embryonic development. Following tetraploid rescue approach, SOCS3 null embryos were recovered, however, the rescued SOCS3 null mice exhibited cardiac hypertrophy and prenatal lethality.

SOCS3 primarily affects the JAK/STAT (Janus activated kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription) pathway, which is induced by many cytokines during physiological and pathological conditions. Cytokines bind to their cell surface receptors and mediate signaling in the regulation of cell growth and cell survival. Interleukins and interferons are two different groups of cellular proteins belonging to this class, which initiate Jak/Stat signaling pathway and contributes to cellular events associated with the disease phenotype. Among the eight SOCS proteins (SOCS1 through SOCS7, and CIS), SOCS1 and SOCS3 proteins, due to the presence of the kinase inhibitory region, specifically target Jak kinase and inhibit its downstream signaling. Although SOCS1 and SOCS3 are structurally similar they are functionally unique and are active only against specific ligands. Functions of SOCS3 are responsive against different ligands that induce JAK/STAT signaling pathway, and several intracellular mechanisms are associated with post-translational modifications of SOCS3. However, this article is focused on the epigenetic regulations, mainly methylation and microRNAs, which affect SOCS3 expression.

1. Molecular mechanism of DNA methylation in the CpG islands

DNMTs (DNA methyltransferases) are enzymes that maintain methylation patterns of DNA following its replication. DNMT1, DNMT3a and DNMT3b have been identified which cooperate and maintain de novo methylation events. In addition, DNMT3L (DNMT like protein, referred as DNMT3A2) was also identified. Recent studies showed that knock down of both DNMT1 and DNMT3b resulted in gene inactivation by complete hypomethylation of the CpG islands [1, 2]. Methyl-CpG binding proteins (MBDs) have also been identified which act as translators between methylated DNA and histone modifiers, and comprises five members of this class, namely MeCP2, MBD1, MBD2, MBD3, and MBD4 [3]. Since cancer cells when treated with demethylating agents led to release of MBD proteins, hypomethylation and gene re-expression, it was presumed that binding of MBDs to methylated sequences is methylation- dependent. However, the affinity of promoters for specific MBDs is still unclear [4]. It is well known that histone deacetylation leads to gene inactivation and DNMTs recruit HDACs. Also DNMTs and MBDs were reported to recruit histone methyltransferases, which modify the lysine 9 residue of the histone H3 [5, 6]. Further, polycomb proteins contribute to these methylation events by cooperating with MBDs and DNMTs [7]. Thus, it is apparent that multiple proteins are involved which cumulatively contribute to the hypermethylation of CpG islands at the 5' position of cytosine and leads to chemical modifications of the DNA in the gene regulatory elements, specifically the promoters and enhancers, which affects gene expression.

2. Methylation of SOCS3 promoter region

The dinucleotide clusters of cytosines and guanines, commonly referred as CpG islands, are found in nearly 40% of the mammalian genes mainly in the promoter and exonic sequences [8]. These CpG islands are considered to be the representative markers in the genomic regions as mutational hotspots that could potentially lead to gene silencing [9, 10]. Gardiner and Frommer [11] deduced that a CpG island typically contains about 50% of C+G content with an observed to expected ratio of 0.6 within a stretch of 200 bp DNA sequence. Later, Takai and Jones [12] extended these values to be containing about 55% of C+G content with an observed-to-expected ratio of 0.65 in a stretch of 500 bp DNA sequence, and showed that these extended parameters are more likely to be associated with the 5' regions and importantly it also excluded the Alu repetitive elements which are the most abundant transposable elements identified in the human genome [12].

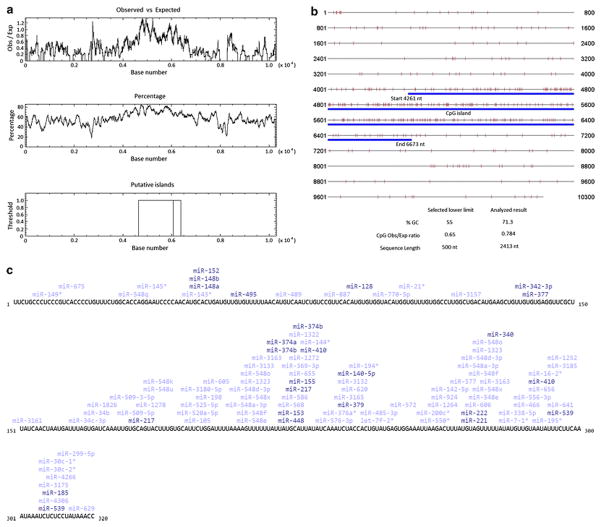

SOCS3 gene in humans is located on chromosome 17q25.3 (NCBI GenBank Accession Number NG_016851.1) that spans in 10.3 kb genomic region and encodes for a 24.77 kDa protein consisting of 225 amino acid residues. Our analysis of the methylation pattern in this genomic region revealed the presence of a putative CpG island that is located between 4261 to 6673 nucleotides of the 10.3 kb sequence. This CpG islands encompass the promoter region of SOCS3 and also extends into its coding sequence from its first exon (Figures 1a and 1b). Using the “CpG island searcher” tool from the Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of South California, we mapped all the methylation hotspots in the SOCS3 genomic region (Figure 1a). These findings correlate with the recently identified SOCS3 promoter region between -556 to -335 nucleotides that has two STAT binding regions located in close proximity to the TATA box indicating their role and significance of the promoter region in regulating SOCS3 expression [13].

Figure 1.

Figure 1a: Identification of the CpG island in the 10.4 kb human SOCS3 genomic sequence using CpG plot (EMBOSS). Figure shows the presence of a distinct CpG island which encompasses the promoter and coding sequence of human SOCS3 gene.

Figure 1b: Characterization of CpG island within the genomic sequence of human SOCS3. Figure shows the close proximity of individual CpG methylation sites within the CpG island that is highlighted in blue.

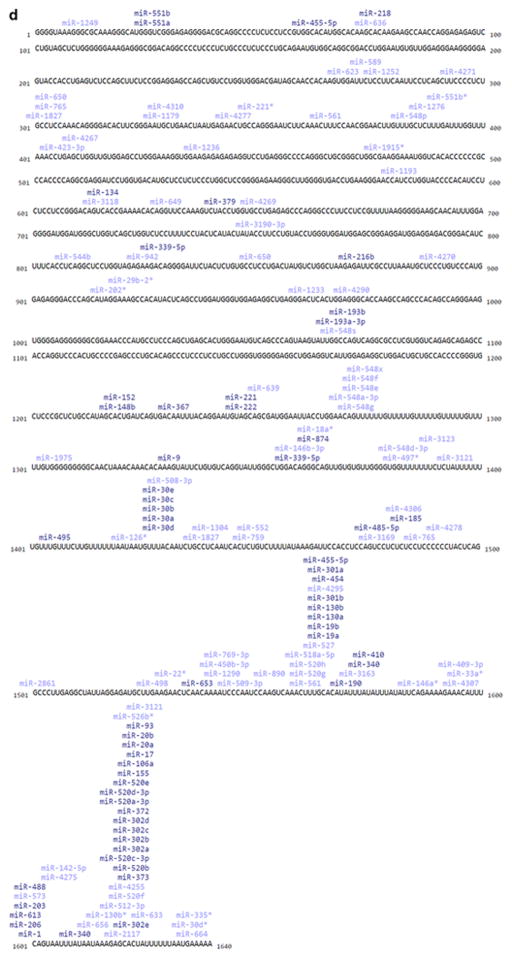

Figure 1c: MicroRNAs that can bind to human DNMT1 transcript. The binding sites of different miRNAs was analyzed at www.microrna.org, which shows the results of DNMT1 and its related sequences from NCBI (NM_001379, NM_001130823, AB209413, AK122759, BC092517).

Figure 1d: MicroRNAs that can bind to human SOCS3 transcript. The binding sites of different miRNAs was analyzed at www.microrna.org,which shows the results of SOCS3 sequence from NCBI (NM_003955.4).

3. Methylation dependent gene regulation by miRNAs

In most organisms including plants and vertebrate animals, miRNAs have been detected. These RNA molecules are about 23 nucleotides long, single-stranded and regulate gene expression controlling various biological processes [14]. In mammalian cells, regulation of gene expression by miRNAs is well documented, and it is clearly evident that miRNAs not only contribute to gene silencing by binding to specific sequences affecting transcription and translation but also mediates mRNA degradation [15]. Differential miRNA expression has also been reported in different tissue and tumor types, therefore down regulation of specific miRNAs in tumors would presumably have tumor suppressor functions [16–18]. These reports extend our understanding that expression or downregulation of certain miRNAs is specific for a given disease phenotype, and their presence would indicate them as signature miRNAs associated with the disease.

Along with an increasing evidence on the differential roles of miRNAs in gene regulation under both normal and pathological conditions, their role in DNA methylation of the promoters regions, gene silencing, gene expression and chromatin structure through histone modifiers was also reported [19–21]. In a specific study, a DNA demethylating agent and a HDAC inhibitor, when added to bladder cancer cells, induced expression of miRNA-127, which inhibited its target proto-oncogene BCL6 [22]. In a similar approach using DNMT1 and DNMT3b null cells, silencing of miRNA-124a induced expression of the oncogenic protein cyclin D kinase-6 [23]. These reports suggest that miRNAs are associated with promoter methylation and their expression or silencing regulates gene expression. In Figure 1c, we show the transcript analysis from www.microrna.org, which identifies possible miRNAs that can bind to the UTR sequence of human DNMT1 mRNA. Evidence from the literature clearly suggests that methylation plays a major role in regulating miRNA expression. In Table 1, we summarized methylation dependent regulation of miRNAs that affect expression of target genes in different human diseases, especially in different cancer types.

Table 1.

Methylation dependent regulation of miRNAs in human diseases

| Disease | miRNA | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atherosclerosis | mir-29b | Down regulates DNMT3b and DNA methylation in human aortic smooth muscle cells. | [98] |

| Atherosclerosis | mir-152 | Down regulation leads to DNMT1 mediated hypermethylation of Estrogen receptor α gene | [99] |

| Breast Cancer | mir-203 | Silencing of miR-203 promotes growth and invasion Breast cancer cells by up regulating the SNAI2 transcription factor. | [100] |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | mir-124-1, -2 | Induction of DNMT1 by Hepatitis C Virus core protein mediates suppression of miR-124. | [101] |

| Colorectal Cancer | mir-345 | BCL2-associated athanogene 3 (BAG3) which is an anti-apoptosis protein, is a target of mir-345. | [102] |

| Colorectal Cancer | mir-373 | The oncogene RAB22A is a target of hsa-miR- 373 which is down-regulated by methylation. | [103] |

| Colorectal Cancer | mir-1-1, 133a-1,133a-2 | Repression of the miR-1-133a cluster by DNA hypermethylation down regulates TAGLN2. | [104] |

| Colorectal Cancer | mir-149 | DNA Methylation dependent silencing of miR- 149 leads to up-regulation of its target protein Specificity Protein 1 (SP1). | [105] |

| Endometrial Cancer | mir-152 | miR-152 targets DNMT1 expression. | [106] |

| Esophageal Cancer | mir-375 | miR-375 negatively regulates PDK1expression in esophageal cancer. | [107] |

| Esophageal Cancer | mir-141 | miR-141 down-regulates SOX17 expression and activates Wnt signal pathway. | [108] |

| Glioblastoma multiforme | mir-211 | miR-211 which is a target of MMP-9 is inhibited by aberrant methylation in Glioblastoma multiforme. | [109] |

| Hepatitis B | mir-101 | Hepatitis B virus x protein down regulates miR-101 by DNA methylation and up regulates DNMT3A. | [110] |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | mir-124, -203 | Inhibited HCC cell growth by downregulatiing CDK6, VIM, SMYD3 and IQGAP1 or ABCE1. | [111] |

| Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma | mir-373 | Methyl-CpG binding protein (MBD2)suppresses expression of miR-373 during tumorigenesis. | [112] |

| Leukemia, Myeloid,Acute | mir-193a | Expression of miR-193a, which is a target for c-kit expression, is repressed by CpG promoter hypermethylation. | [113] |

| Leukemia, Myeloid,Acute | mir-193a | miR-193a represses expression of AML1/ETO, DNMT3a, HDAC3, KIT, CCND1, and MDM2; increases PTEN activity, induces G1 arrest and apoptosis. | [114] |

| Leukemia-Lymphoma | mir-143 | Methylation mediated repression of miR-143increases expression of the oncogene MLL-AF4 ALL. | [115] |

| Liver metastases of colon cancer | mir-34a | Silencing of miR-34a by CpG methylation upregulates expression of c-Met, Snail, and β-catenin. | [116] |

| Lung Cancer | mir-29a, 29b-1,29c | miR-29 family directly targets DNMT3A and -3B expression in lung cancer cell lines and induces expression of FHIT and WWOX. | [117] |

| Lupus Erythematosus,Systemic | mir-126 | miR-126 inhibits Dnmt1 expression by interaction with its 3'-UTR. | [118] |

| Lymphoma, B-Cell | mir-29 | miR-29 is repressed by MYC through HDAC3and EZH2 complex. | [119] |

| Melanoma | mir-31 | The kinases SRC, MET, NIK and the oncogene RAB27a are functional targets of miR-31. | [120] |

| Multiple cancer types | mir-34a, 34b,34c | Found inactivated by CpG methylation during tumor formation | [121] |

| Multiple Myeloma | mir-203 | CREB1 is a direct target of miR-203. | [122] |

| Myelodysplastic Syndromes | mir-124 | Methylation dependent silencing of miR-124is associated with EVI1 expression. | [123] |

| Neuroblastoma | mir-340 | miR-340 represses SOX2 transcription factor by targeting its 3'UTR. | [124] |

| Pancreatic Cancer | mir-124 | miR-124 downregulates Rac1 and inactivates MKK4-JNK-c-Jun pathway. | [125] |

| Prostate Cancer | mir-29a, -1256 | miR-29a and miR-1256 decreases expression of TRIM68 and PGK-1. | [126] |

| Prostate Cancer | mir-34b | miR-34b induces G0/G1 cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis by targeting the Akt and its signaling; also decreases expression of vimentin, ZO1, N-cadherin, and Snail. | [127] |

| Prostate Cancer | mir-31 | miR-31 suppressed E2F1, E2F2, EXO1,FOXM1, and MCM2 through androgen receptor regulatory mechanism. | [128] |

| Squamous Cell Carcinoma | mir-9-1, -2,-3 | Up regulates PTEN expression. | [129] |

| Stomach Cancer | mir-212 | miR-212 represses expression of MeCP2protein but not mRNA. | [130] |

| Stomach Cancer | mir-181c | miR-181c targets NOTCH4 and KRas to regulate Gastric Carcinogenesis. | [131] |

| Stomach Cancer | mir-10b | miR-10b targets MAPRE1 expression. | [132] |

| Stomach Cancer | mir-139 | HER2 inhibits miR-139 by up regulating CXCR4: promotes tumor progression and metastasis. | [133] |

| Stomach Cancer | mir-195 | miR-195 and miR-378 suppress CDK6 and VEGF signaling in gastric cancer. | [134] |

4. Regulation of SOCS3 expression by miRNAs

Silencing of miR-122 in the Huh7 hepatocellular carcinoma cells has been found to increase methylation in the SOCS3 promoter region as a result of which SOCS3 expression was found to be greatly reduced, which enhanced IFN-α signaling. Interestingly, decreased SOSC3 expression was also reported by miR-122 silencing in DNMT1 knockdown cells, which indicates that hypermethylation of SOCS3 promoter resulting from miR-122 silencing is independent of the methylating enzyme DNMT1 [13]. The authors also identified higher levels of STAT3 phosphorylation in miR-122 silenced cells treated with IFN-α besides decreased SOCS3 expression. Also in the same cells, SOCS3 expression was not induced upon treatment with IFN-α, IFN-β, IFN-γ or IFN-λ which stimulated SOCS3 expression in control cells, and increased expression of miR-122 was observed after IFN-λ treatment.

Significant up regulation of miR-203 was demonstrated in human breast cancer tissues and in MCF-7 breast cancer cell line. Knockdown of miR-203 was reported to enhance SOCS3 expression along with activated caspase 7- and caspase 9-mediated cellular apoptosis with increased sensitivity towards cisplatin treatment [24]. In murine hepatoma cells, over expression of miR-802 was shown to increase the transcript levels of SOCS1 and SOCS3, and identified that the hepatocyte nuclear factor 1β (Hnf1b), which is a transcription factor, as a primary target for miR-802. The authors also showed that knockdown of Hnf1b resulted in upregulation of SOCS1 and SOCS3 [25].

It was identified that the inhibition of IGF-2 upregulates SOCS3 expression, and the expression of miR-483-5p correlates with IGF-2 expression in mouse cancer cells, which indicates that miR-483-5p has an indirect effect on SOCS3 expression. Accordingly the authors also identified that overexpression of miR-483-5p suppresses SOCS3 expression [26]. Upregulation of SOCS3 and GHR in the skeletal muscle tissues of chickens with dwarf phenotype was recently reported. Using DF-1 chicken fibroblast cells, the authors demonstrated the regulatory role of miR-let-7b in the expression of GHR, and in this study overexpression of let-7b was reported to decrease expression of GHR and SOCS3, which suggests that let-7b regulates GHR mediated SOCS3 expression by affecting the Jak/Stat signaling pathway [27].

SOCS3 is a known negative regulator of G-CSF receptor signaling which is induced by STAT3. Using NIH3T3 cells that constitutively expression miR-125b, STAT3 was identified as its direct target. Transfection of these cells with the STAT3 UTR sequences fused with luciferase reporter gene showed about 40% reduction in the luciferase activity, and since SOCS3 is a feedback inhibitor of STAT3, these results imply that miR-125b affects SOCS3 expression by inhibiting STAT3 [28].

Respiratory syncytial virus infection of A549 human alveolar epithelial cells was identified to induce the expression of microRNA miR-let-7f. The RSV G-protein was also reported to trigger the expression of miR-let-7f along with SOCS1 and SOCS3 that negatively regulates IFN mediated Jak/Stat signaling [29]. Inhibition of SOCS3 protein was also reported in HEK293 cells that were transfected with miR-19a and stimulated with cardiotrophin-1, which is a specific ligand for gp130. However, the transcript levels of SOCS3 remained unaffected indicating that the microRNA miR-19a binds to the SOCS3 transcripts and affects its translation [30]. In Figure 1d, transcript analysis from www.microrna.org is demonstrated, which reveals the possible miRNA binding sites in the UTR region of human SOCS3 mRNA.

5. Role of DNA methylase in epigenetic silencing of SOCS3

Treatment with the proinflammatory cytokine, TNF-α, or the insulin growth factor resulted in increased SOCS3 expression in procine coronary smooth muscle cells; however, their combined treatment resulted in about five-fold decrease in SOCS3 expression [31]. We also identified similar findings in human coronary smooth muscle cells in which about five-fold decrease in the SOCS3 mRNA transcripts and protein levels were detected when treated with TNF-α and IGF-1 together. Interestingly, the combined treatment of both TNF-α and IGF-1 resulted in concomitantly higher levels of DNMT1 transcripts, indicating possible hypermethylation of SOCS3 gene which was further confirmed using methylation specific PCR [32]. Since TNF-α and IGF-1 are upregulated in atherosclerosis and also due to mechanical injury, abrogation of SOCS3 in presence of TNF-α and IGF-1 with concomitant increase in DNMT1 indicates epigenetic gene silencing of SOCS3 due to hypermethylation as the potential underlying mechanism that contributes to hyperplasia and leads to atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease [32]. Activation of STAT3 by IL-6 initiates proinflammatory response, while IL-10-mediated activation of STAT3 promotes anti-inflammatory response. As SOCS3 regulates Jak/Stat signaling which is also involved in inflammatory responses, apparent role of SOCS3 in inflammation could be predicted. Besides activation of both Stat1 and Stat3 by IL-6, it also was shown to negatively regulate SOCS3 expression, and recently the mechanism which interlaces the cytokine signaling with DNA methylation and leads to inhibition of IL-6 mediated silencing of SOCS3 expression was identified where IL-6 induced DNMT1 activity and promoted hypermethylation of SOCS3 leading to the inhibition of SOCS3 expression [33].

6. Methylation status of SOCS3 in different cancer types

There is increasing evidence that hypermethylation in the CpG islands of SOCS3 promoter leads to epigenetic silencing of SOCS3. Recently in H460 cells (NSCLC cancer) hypermethylation of SOCS3 promoter region was observed, and transfection of these cells with SOCS3 expression vector resulted in induction of apoptosis and growth inhibition along with reduced STAT3 phosphorylation [34, 35]. The same group has also identified that the SOCS3 promoter region contains two adjacent Stat binding sites. Interestingly, the Stat binding sites were identified within the CpG island which is subjected to hypermethylation, and therefore it correlates with the up regulation of Stat activity in absence of SOCS3 expression due to its epigenetic silencing [36]. In about 90% of patients with HNSCC, hypermethylation of SOCS3 was reported, and transfection of HNSCC cells with wild type SOCS3 resulted in induction of apoptosis and growth suppression besides downregulation of Stat3, bcl-2 and bcl-xL [37]. In cholangiocarcinoma, hypermethylation and epigenetic silencing of SOCS3 was observed with IL-6 induced aberrant activation of Stat3 resulting in resistance to cellular apoptosis [38]. About 35% of patients with Glioblastoma multiforme brain tumor were reported positive for methylation of SOCS3 in its promoter region, as identified through methylation specific PCR and bisulphite sequencing [39]. In another report that analyzed tumor samples from glioma patients, about 28% of patients were detected to have SOCS3 promoter methylation which was identified through bisulfite sequencing [40]. In an Asian cohort study with 62 patients having Glioblastoma multiforme, a tight correlation has been reported between hypermethylation of the SOCS3 promoter and CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP). This study further confirms and validates the above two findings which indicate that hypermethylation of the SOCS3 promoter could be a prognostic indicator in Glioblastoma multiforme patients [41]. Besides, hypermethylation of SOCS3 was also reported in other diseases, including malignant melanoma [42], Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma [43] and in many other cancer types.

Aberrant methylation of SOCS3 was identified in six out of eighteen hepatocellular carcinoma samples and in three out of ten HCC cell lines, besides similar frequency of suppressed SOCS3 expression was also observed in one out of three unmethylated primary samples. However, IL-6 was found to enhance Stat3 activity leading to cell growth and treatment with Jak2 inhibitor suppressed Stat3 phosphorylation but not FAK phosphorylation thus cell migration was not affected. FAK was reported to directly interact with SOCS3, and its interaction with Elongin B & C was shown to direct it to the proteasome degradation pathway [44]. These results also showed that restoration of SOCS3 in these cells resulted in inhibition of both cell growth and migration. DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) was identified to activate PPAR-γ which in turn transcriptionally induces SOCS3 expression. Subsequently, the ability of TH17 cells to produce IL-17 and enhance tumor growth was diminished due to the above increase in SOCS3 expression. These studies clearly indicate the anti-tumor properties of SOCS3 [45].

Multiple myeloma

Not all multiple myeloma cells lines was reported to exhibit methylation in the CpG island of SOCS3, and only in five out of seventy patients with malignant plasma cell disorders, SOCS3 was found methylated. Patients with methylated SOCS3 region were found with increased biochemical levels of LDH and creatinine [46]. Recently, platelet factor 4 (PF4) was shown to induce SOCS3 expression in U266 and OPM2 myeloma cells besides negatively regulating STAT3 and also down regulating the STAT3 target genes such as Mcl-1, survivin and VEGF [47].

Myeloproliferative disorders

The four main myeloproliferative diseases include: chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocytosis (ET), and myelofibrosis (MF). In the bone marrow cells of CML patients with IFN-α treatment, very low levels of SOCS3 mRNA was observed, however no methylation in the SOCS3 promoter sequence was observed which discloses an inverse correlation between SOCS3 expression and IFN-α sensitivity [48]. A recent clinical study on 39 patients with essential thrombocythemia, methylation-specific PCR analysis revealed no significant difference on increase in the methylation of SOCS3 or SOCS1 or PTPN6 compared with healthy individuals. Therefore methylation analysis of these negative regulators of Jak2 as a prognostic marker did not add to measurable values for ET patients characterized with myeloproliferative neoplasms [49]. Hypermethylation in the SOCS3 promoter region was also identified in sixteen out of sixty patients with Myelofibrosis but not in patients with PV or ET [50]. Another clinical study focused on 119 patients with PV or ET identified that 15 patients including adults and children showed hypermethylation of SOCS3 [51]. Recently, methylation profiling of SOCS3 in cell lines and bone marrow samples as shown through methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction increased methylation of SOCS1 and SOCS3 which was specific to CpG residues in the 3' translated exon sequences [52].

Using methylation-specific PCR, positive methylation was found in 13 out of 15 patients with renal cancer [53]. Twenty out of 51 patients with prostate cancer were detected for hypermethylation of SOCS3 [54]. Hypermethylation of SOCS3 was observed in 8 out of 24 patients diagnosed with acute myelogenous leukemia [55]. CD33 receptor was identified as a myeloid specific marker and SOCS3 was reported to inhibit CD33 receptor mediated cell proliferation. Treatment with gemtuzumab ozogamicin showed a higher response and overall survival in patients with methylated SOCS3. Sixteen out of twenty six liver specimens from patients diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma displayed activation of Stat3 and silencing of SOCS3, and treatment with demethylating agent inhibited IL-6 induced Mcl-1 expression therefore sensitizing the cholangiocarcinoma cells to TRAIL mediated apoptosis [56].

7. Pathological diseases associated with the regulation of SOCS3 expression

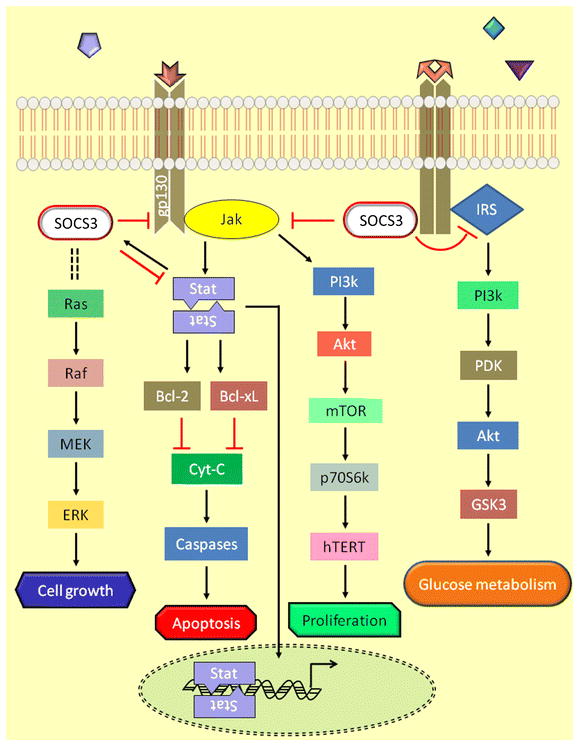

Besides cancer, there is increasing evidence for a prominent role of SOCS3 in different pathological conditions. The Figure 2 shows illustrations of possible interventions of SOCS3 in various human diseases.

Figure 2.

Possible SOCS3 interventions in various human diseases. Figure illustrates the effector pathways that are mediated by SOCS3 in different human diseases.

Immunological disorders

Some of the immunological disorders associated with SOCS3 expression include atopic asthma, dermatitis, multiple sclerosis, allergy, etc. In patients with TH2 type diseases, increased SOCS3 expression was correlated with intense disease severity, and higher levels of IgE were detected in patients with severe allergy [57]. In transgenic mice with constitutive expression of SOCS3, ovalbumin enhanced airway hyper responsiveness and increased levels of IgE, TH2 cytokines along with eosinophil infiltration were detected [58]. SOCS3 is not only involved in T cell differentiation but it also governs the T cell functions by negatively regulating the IL-2 signaling. Available evidence suggests that SOCS3 interacts with the PI3 kinase binding site on CD28 and affects CD28 mediated production of IL-2 [59]. Thus, it is logical to deduce that SOCS3 would have an active role in autoimmune diseases. In this direction, recent evidence shows that IFN-α treatment in psoriatic T cells abrogates SOCS3 expression and activates Jak/Stat pathway [60, 61]

Cardiovascular diseases

Studies from our laboratory have identified the essential role of SOCS3 in preventing neoinitimal hyperplasia in the coronary arteries both in vitro and in vivo. These studies revealed decreased SOCS3 expression in atherosclerotic microswines and in vitamin-D deficient hypercholesterolemic microswines suggesting that vitamin-D deficiency leads to cardiac hypertrophy and SOCS3 gene therapy would aid in the prevention of the associated cardiovascular diseases [31, 32, 62]. Adenovirus-mediated delivery of SOCS3 into cardiomyocytes was identified to suppress hypertrophic and anti-apoptotic phenotype induced by LIF mediated gp130 receptor signaling through Jak/Stat pathway, where LIF was also identified to induce Akt, MEK and ERK activation indicating that SOCS3 is induced by mechanical stress [63]. Recently in cardiac specific SOCS3 knockout mice, increased gp130 receptor mediated activation of Stat3, ERK, Akt and p38 was observed in adult mice between 15 to 25 weeks of age which displayed cardiac dysfunction and heart failure. However mice with cardiac specific gp130 and SOCS3 double knockout genotype were reported to live longer with histological abnormalities [64]. Though sufficient evidence exists which indicates that SOCS3 is regulated by IL-17 during atherosclerosis, the exact role of IL-17 in atherosclerosis is a subject of debate and controversy which requires further investigation.

Asthma

In asthmatic lungs of mice, IL-6 induced epigenetic regulation of SOCS3 was recently reported where acetylation of histone H4 was identified as the underlying epigenetic mechanism. Higher levels of acetylated histone H4 was found associated with SOCS3 promoter region which supports the hypothesis that histone acetylation regulates gene transcription by altering the chromatin structure. The study also shows that treatment with DNA methyltransferase inhibitor did not up regulate the transcriptional levels of SOCS3 indicating that although there is a dynamic correlation between methylation and histone acetylation, the two are independent mechanisms which regulate the chromatin structure and gene expression [65]. Recently, low levels of DNMT1 transcripts were observed in asthmatic mice compared to normal mice, and in the albumin challenged asthmatic mouse model, knockdown of DNMT1 was shown to induce SOCS3 expression which was correlated with hyperacetylation of histones [66, 67]. Suppression of SOCS3 through intranasal delivery of siRNA in mice was also found to increase eosinophil count, airway remodeling and improved mucus secretion [68].

Diabetes

Insulin was shown to induce SOCS3 expression and expression of Stat5B further enhanced the expression of SOCS3. Further SOCS3 protein engages negative feedback inhibition of insulin induced signaling without affecting the insulin receptor tyrosine kinase activity. The study also showed the possible molecular mechanism, and in this regard the Tyr960 residue of the insulin receptor is critical and is required for the binding of SOCS3 and Stat5B [69]. Also in patients with Type-II diabetes, abundant protein levels of phosphorylation of STAT3, phosphorylated Jak2 and SOCS3 was reported in their skeletal muscle cells, and STAT3 gene silencing through siRNA was shown to prevent lipid induced insulin resistance [70]. In obese and insulin resistant mice that were fed with high fat diet, elevated levels of HIF1α was reported, and in 3T3-L1 adipocytes that were treated with acriflavine, which is an HIF1α specific inhibitor, reduced expression of SOCS3 was reported [71].

The fibroblast growth factor-21 plays a vital role in regulating the metabolic disorder of insulin resistance that was associated with Type II Diabetes. Knock down of FGF-21 through adenoviral mediated delivery of shRNA specific to FGF-21 in ApoE null mice that were fed with high fat diet showed drastic increase in liver specific glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis [72]. This study also shows that liver specific activation of G6Pase and PEPCK enzymes is mediated through STAT3 pathway which inhibited SOCS3 expression causing insulin resistance in these mice.

Neurological disorders

In mouse astroglia and microglia, treatment with gemfibrozil was reported to induce SOCS3 mRNA and protein levels in a dose dependent manner with simultaneous activation of pAkt, p110 subunit of PI3k and Krüppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) suggesting that PI3K/Akt/KLF4 pathway mediates up regulation of SOCS3 in glial cells, and gemfibrozil would have important applications in the neuro-inflammatory and neurodegenerative disorders [73].

Viral infections

Overexpression of hepatitis C virus core protein was found to inhibit IFN-α induced activation of STAT1 thus preventing its nuclear translocation, and this inhibition was accompanied with an increase in SOCS3 mRNA suggesting that the HCV viral core protein is capable of inhibiting IFN-α mediated Jak/Stat signaling by up regulating SOCS3 expression [74]. In mice that are systemically infected with murine cytomegalovirus, IL-17 production was reported to be downregulated through stimulation of SOCS3 and IL-10 [75]. Loss of SOCS3 expression in SOCS3 conditional KO mice when infected with Herpes Simplex Virus was reported to have decreased number of HSV-1-specific CD8 T-cells. Whereas, increased number of HSV-1-specific CD8 cells were reported in STAT3 conditional KO mice indicating the therapeutic benefits of SOCS3 in modulating CD8 mediated host immunity against HSV infection [76].

Arthritis

In IL-6 knockout mouse model it was identified that mice lacking IL-6 were resistance to antigen induced arthritis indicating that IL-6 mediates progression of arthritis [77]. In patients suffering with Rheumatoid Arthritis but not with Osteoarthritis, elevated levels of SOCS3 mRNA with increased Stat3 phosphorylation was detected in their synovial tissue [78]. The above two findings correlate to the up regulation of IL-6 mediated Jak/Stat signaling which is regulated by SOCS3. Accordingly, adenovirus expressing SOCS3 when injected into the ankle joints of antigen or collagen induced arthritis mouse models resulted in reduced disease severity [78].

Osteoporosis

Differential expression of SOCS3 mRNA transcripts has been found in the bone of rats that received intermittent administration of PTH (1–34) peptide derived from parathyroid hormone. Since parathyroid hormone is used for the treatment of osteoporosis, these findings suggest that upregulation of SOCS3 with PTH (1-34) peptide treatment could be a mechanism to suppress the effects of inflammatory cytokines and thus could prove to be viable therapeutic approach in osteoporosis [79].

8. Molecular mechanism of SOCS3 inhibiting Jak/Stat signaling pathway

In mammals, Jak/Stat signaling pathway is the main axis by which cytokines induce cellular events such as cell proliferation, cell growth, cell migration, cell differentiation, and apoptosis which are critical for hematopoiesis, immune development, adipogenesis, cell growth. Jak/Stat pathway is activated by cytokines and tyrosine kinases, and is inhibited by tyrosine phosphatases, specific inhibitors and SOCS proteins. Jak kinases associate with the cytoplasmic domains of its receptor subunits, and ligand upon binding to these receptors induces homodimerization or heteromultimerization of the receptors and brings the two Jak molecules in close proximity resulting in their activation through transphosphorylation. These activated Jak molecules subsequently phosphorylate the cytoplasmic domain of the Jak receptor and as a result Stat proteins are recruited which are activated through phosphorylation by Jak kinases. The activated Jak kinase phosphorylates the tyrosine residue within the oligomerization domain of Stat protein which upon phosphorylation interacts with another phosphorylated Stat protein and dimerizes [80]. The Stat proteins upon activation and dimerization internalize into the nucleus where they bind to specific sequences in the promoter region and regulate gene expression [81].

SOCS3 is a negative regulator of Jak/Stat (Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription) pathway that directly binds to Jak and inhibits its kinase activity, which leads to abrogation of Jak/Stat signaling. A wide range of ligands including different cytokines such as interleukins, interferons, GM-CSF, EPO, LIF, CNTF, EGF, PDGF, leptin, insulin, cardiotrophin, growth hormone, prolactin and many more were identified to regulate SOCS3 expression. Different interleukins that are regulated by SOCS3 and also interleukins that either directly or indirectly control SOCS3 expression are shown in Table 2. SOCS3 was identified to interact with specific phosphopeptide sequences within Jak’s, Stat’s and the gp130 receptor subunit. Preferentially, SOCS3 binds to the SHP-2-binding site on the gp130 receptor and inhibits the downstream signaling induced by multiple cytokines. Though SOCS3 and SOCS1 inhibit Jak/Stat signaling in a similar mechanism, SOCS3 was identified to have higher affinity towards Tyr757 residue of the gp130 receptor. SOCS3 is the only SOCS protein known to be phosphorylated, and two different phosphorylation sites at Tyr204 and Tyr221 residues within the C-terminal region of the SOCS box were identified [82]. SOCS3 binds to the catalytic domains of Jak kinases (except Jak3) that have an evolutionarily conserved GQM motif in the insertion loop. The gp130 receptor induces conformational changes in the KIR-ESS-SH2 domain of SOCS3 which enables SOCS3 to bind to the JH1 domain in the JAK kinases [83]. The SH2 and the N-terminal KIR domain of SOCS3 which functions as a pseudosubstrate, interacts with the JH1 kinase domain located within the activation loop of the phosphorylated Jak2 and the phosphorylation of the Tyr1007 is critical for this interaction, while KIR domain strongly inhibits the kinase activity of Jak2 and inhibits its downstream signaling [84, 85]. Similar interactions of SOCS3 with Brk kinase was recently reported where SOCS3 although binds to the Brk kinase through SH2 domain, its inhibitory activity is mediated through the KIR domain of SOCS3. Since mutations in the KIR domain abrogate the inhibitory activity of SOCS3 towards Brk kinase, it is presumed that the KIR domain mediates the kinase inhibitory activity of SOCS3 and while the SH2 domain aids in binding through the phosphotyrosine residues, also the KIR domain was found to assist in this SH2 domain mediated binding of SOCS3 to this Brk kinase [86]. Interestingly, human endothelial cells when treated with the pro-inflammatory molecule, resistin, was found to result in a significant increase in SOCS3 expression both at mRNA and protein levels. This increase is accompanied with increased phosphorylation of Stat3 and treatment with Stat3 inhibitor blocked resistin-induced SOCS3 expression [87]. These findings suggest a dual regulatory role of SOCS3 in endothelial cells because IFN-γ-induced SOCS3 expression was previously identified to inhibit Stat3 expression induced by IL-6 [88].

Table 2.

Regulation of SOCS3 by different interleukins

| Interleukin | Mechanism by which SOCS3 regulates corresponding interleukins | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| IL-1 | SOCS3 inhibits IL-1 signaling by targeting TRAF-6/TAK1 signaling | [135] |

| IL-2 | T cells from SOCS3 transgenic mice showed reduced IL-2 production | [136] |

| IL-3 | Siglec-7 in absence of SOCS3 inhibits IL-3 induced cell proliferation. | [137] |

| IL-4 | IL-4 induces SOCS3 expression, and SOCS3 inhibits IL-4 expression by inhibiting c-Jun through ERK signaling | [138-140] |

| IL-6 | SOCS3 inhibits IL-6 induced by LPS | [141] |

| IL-7 | Downregulates SOCS3 | [142] |

| IL-8 | The proinflammatory activity of IL-8 is inhibited in cells transfected with SOCS3 expression vector. | [143] |

| IL-9 | IL-9 induces SOCS3, and overexpression of SOCS3 suppresses IL-9 mediated signaling | [144] |

| IL-10 | Enhances SOCS3 expression and is also reported to inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokines | [145] |

| IL-11 | IL-11 stimulates SOCS3 production, and SOCS3 over expression inhibits IL-11 mediated activation of STAT3 | [146] |

| IL-12 | SOCS3 inhibits IL-12 induced activation of STAT4 by binding to IL-12 receptor through its SH2 domain | [147] |

| IL-13 | IL-13 induces expression of SOCS3 by activating STAT6 | [148] |

| IL-15 | IL-15 treatment led to rapid phosphorylation of STAT6 in Mast cells (no evidence was shown if STAT6 further induces SOCS3 expression) | [149] |

| IL-17 | SOCS3 induced IL-17 production | [150, 151] |

| IL-18 | IL-18 upregulates SOCS3 expression in liver NKT cells | [152] |

| IL-19 | Lack of SOCS3 expression leads to IL-6 receptor mediated upregulation of IL- 19, IL-20 and IL-24 | [153] |

| IL-20 | Lack of SOCS3 expression leads to IL-6 receptor mediated upregulation of IL- 19, IL-20 and IL-24 | [153] |

| IL-21 | Induces STAT3 activation, which further induces expression of SOCS3 | [154] |

| IL-22 | Induces activation of STAT1 & STAT3, upregulates SOCS3 | [155] |

| IL-23 | SOCS3 negatively regulates IL-23 signaling | [151] |

| IL-24 | Induces STAT3 activation and SOCS3 expression; Lack of SOCS3 leads to IL-6 receptor mediated upregulation of IL-19, IL-20 and IL-24 | [153, 156] |

| IL-25 (IL- | IL-25 induces p38MAPK pathway dependent expression of SOCS3 in CD14 | [157] |

| 17E) | positive Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells | |

| IL-26 | IL-26 induced SOCS3 mRNA expression in intestinal epithelial cells | [158] |

| IL-27 | IL-27 induced SOCS3 expression in CD4 positive T cells | [159] |

| IL-28A | IL-28A induces expression of SOCS3 mRNA by activating STAT1 in human colorectal cancer cells | [160] |

| IL-29 | IL-29 induces expression of SOCS3 mRNA by activating STAT1 in human colorectal cancer cells | [160] |

| IL-31 | IL-31 activates STAT1 and STAT3 but it is not reported if the activated STATs could induce SOCS3 expression. Dose and time dependent induction of SOCS3 by IL-31 was reported in human lung epithelial cells. In keratinocytes IL-31 did not upregulate SOCS3. | [161, 162] |

| IL-32 | Induction of IL-32 and simultaneous increase in SOCS3 mRNA was observed in human ATII cells infected with Influenza A virus | [163] |

9. Signaling pathways regulated by SOCS3

Constitutive activation of Stat proteins was observed in many cancer types indicating that abnormal upregulation of Jak/Stat signaling contributes to the malignant phenotype resulting from cell growth and cell survival. Further, cytokines induce SOCS3 expression which in turn prevents activation of Stat proteins by inhibiting Jak activity demonstrating a negative feedback inhibition mechanism. The crosstalk between the Jak/Stat pathway, PI3k/Akt pathway and the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway was previously reviewed [80]. IL-2 induced telomerase activity through hTERT expression was reported in Adult T-cell Leukemia cells where it activates Jak1/2 through IL-2R receptor and leads to dimerization and activation of Stat5. IL-2 was also shown to activate PI3k/Akt/mTOR/S6k pathway and transcriptionally regulates hTERT expression which is modulated by the presence of HSP90 [89, 90]. In hepatocytes, SOCS3 regulates IL-6 mediated Jak/Stat3 pathway through gp130 receptor, and in hepatocyte specific SOCS3 knockout mouse model, absence of SOCS3 was shown to enhance activation of Stat3 and ERK1/2 following IL-6 or EGF stimulation which indicates that SOCS3 inhibits EGF receptor mediated IL-6 signaling by inhibiting MEK and ERK kinases [91]. The essence of Jak2 in growth hormone stimulated activation of ERK was also reported, and this activation of ERK is dependent on both Ras and Raf which act upstream in the signaling pathway, these results clearly demonstrate that Jak/Stat signaling crosstalks with Ras/Raf/ERK pathway [92]. Ras signaling was regulated by the interaction of SH2 domains of p120 RasGAP with a tyrosine residue of SOCS3 in its extreme C terminus region. Through mutation studies the authors identified that both Jak1 and Jak2 can phosphorylate the Tyr204 and Tyr221 residues on SOCS3 which were located in the C-terminal conserved SOCS box region, and a phosphopeptide from this region was found to interact with p120 RasGAP protein which was confirmed by microsequencing. These results elucidate that the SH2 binding domains of p120 RasGAP would interact with the phosphorylated Tyr204 and Tyr221 residues of SOCS3 protein. However, only phosphorylation of Tyr221 is essential for SOCS3 interaction with RasGAP and Jak is required for this binding to maintain Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway [82]. Expression of SOCS3 in tumor cells through cellular transfection was found to result in growth suppression by downregulation of Stat3, bcl-2 and bcl-xL [37]. Since bcl-2 and bcl-xL are important regulators of apoptosis which inhibit downstream caspases, it clearly indicates that expression of SOCS3 could also lead to induction of apoptotic pathway. However a recent report using PC3 cells, knockdown of SOCS3 by siRNA was shown to result in activation of both cell intrinsic or extrinsic apoptotic pathways through activation of caspases 3, 7, 8 & 9 and up regulation of PARP besides inhibiting the anti-apoptotic protein bcl-2. [93]. The same group also reported that SOCS3 inhibits FGF-2 induced cell proliferation and migration by inhibiting ERK1 and ERK2, independent of Stat1, Stat3 or Akt activation indicating that SOCS3 inhibits cell proliferation independent of Akt or Jak/Stat pathway. A mouse knock-in mutant having a substitution of tyrosine to phenylalanine at 757 residue in gp130 incapacitated its ability to interact with SOCS3 and resulted in hyperactivation of Stat3, and consequently it resulted in the induction of TGF-β and smad7 [94]. These findings demonstrate that Jak/Stat and TGF-β signaling pathways crosstalk and affect downstream transcription. Interestingly, it was also observed that this signaling crosstalk is the causative mechanism for liver fibrosis in mice lacking liver specific expression of SOCS3 [95]. It would be more interesting to extend these studies in gp130 null conditions. The SOCS box region of SOCS3 was identified as the essential region responsible for ubiquitination and degradation cellular proteins such as Jak’s including SOCS proteins by interacting with Elongin B and Elongin C, Cul-5, and Rbx1-2 to form a E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. Besides the SH2 domain was found to interact with the Tyr397 residue of FAK and inhibit its activity by directing it to the protease degradation pathway through polyubiquitination [96]. Hypermethylation of SOCS3 was found inversely correlated with EGFR in primary glioblastomas which characteristically have elevated levels of EGFR. Also complete knockdown of SOCS3 in glioblastoma cells resulted in activation of EGFR related signaling by increasing Stat3, FAK and MAPK, but was independent of Akt activation [97]. The intracellular signaling pathways which were affected by SOCS3 in regulating cell proliferation, migration, apoptosis and glucose metabolism were shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Intracellular signaling mechanisms regulated by SOCS3

Future directions

Since genetic loss of SOCS3 is embryonically lethal, additional studies such as conditional and tissue-specific knockdown of SOCS3 are required which would answer specific questions that would lead to a better understanding of both direct and indirect induction and tissue specific regulation of SOCS3. SOCS3 mediates direct inhibition of JAK. Therefore, JAK-specific inhibitors were developed for clinical use. Ruxolitinib is a specific inhibitor of Jak1/2 that was FDA approved in 2011 for the treatment of myelofibrosis. In mouse model with myeloproliferative neoplasm, oral administration of ruxolitinib prevented splenomegaly and decreased the circulating levels of the inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α and IL-6. Two Phases III studies, a double-blind and an open-label trial were conducted in which patients who received ruxolitinib were reported to achieve more than 35% reduction in spleen volume. Ruxolitinib was shown to inhibit cytokine-induced activation of STAT3 in patients with myelofibrosis and in healthy individuals where maximal inhibition was reported at 2 hours after dosing which returned to near baseline in about 10 hours. With these promising results of ruxolitinib in inhibiting JAK functions, different JAK inhibitors can be tested in other pathologies where inhibition of JAK would lead to disease prevention or cure.

Several cytokines and interferons have been identified as ligands which induce Jak/Stat pathway in different pathological conditions, thus several drug manufacturers have developed inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies for these cytokines and interferons some of which are in different phase trials for the treatment of SOCS3 related diseases. Besides these inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies against specific pathway mediators have been found to be effective and many of which are currently used in the treatment of many human diseases. The gp130 specific antibody "sgp130Fc" with a strong potential to block and inhibit IL-6-mediated signaling could be used in clinical trials to test its efficiency in treating the inflammatory bowel diseases, including Crohn’s Disease. This Jak/Stat signaling pathways is also the primary axis which mediates cellular functions that are vital to the progression of many diseases. Therefore, use of the monoclonal antibody would have parallel functions to that of SOCS3- mediated intracellular signaling.

Post-translational modifications on SOCS3 protein severely affect its cellular functions, in particular sumoylation, ubiquitination and methylation. Also, as we have reported, epigenetic suppression of SOCS3 is mediated through DNMTs-methylation activity on the CpG islands of the SOCS3 promoter region, which could be reversibly inhibited through DNMT specific inhibitors. The Jak inhibitory functions of SOCS3 were attributed to its kinase inhibitory region, therefore development of novel short peptide molecules derived from the functional motifs of the KIR domain could have significant therapeutic benefits. Such peptide molecules can be conjugated with cell penetrating peptides or can be delivered through nanoparticles for effective drug release. Besides, certain microRNAs were also identified to directly or indirectly inhibit or induce SOCS3 expression, and in this direction further studies are warranted for expression of miRNAs using viral vectors or other feasible experimental approaches.

As evident, SOCS3 plays a vital role in many human diseases and biochemical inhibition of SOCS3 targets through use of specific inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies was found to be beneficial for the treatment of SOCS3 associated diseases. Similarly, development and use of SOCS3 inducers could also aid in the treatment of SOCS3 related diseases, and in this direction our laboratory has conducted SOCS3 gene therapy trials using AAV vectors for the treatment of coronary restenosis.

Key issues.

SOCS3 protein is subjected to post translational modifications, which reduces its cellular levels affecting homeostasis, and since the mechanisms of post translational modifications are also the cellular defense mechanisms, it is always a challenge to maintain the threshold levels of SOCS3.

SOCS3 essentially inhibits cellular proliferation affecting more than three different signaling pathways, therefore identification of a specific responsive pathway in a given pathology is critical. Besides, an identified pathway intermediate could also be regulating other pathways which greatly limit the therapeutic strategies in using single molecule inhibitors. To overcome these issues new treatment strategies are implemented, although with limited success, where other drugs that induce or co-inhibit the pathway intermediates are used.

The approved JAK inhibitor, “Ruxolitinib”, like other synthetic drugs has the potential to induce deleterious side effects such as thrombocytopenia, anemia and neutropenia. Although ruxolitinib is used to inhibit Jak, its mechanism of inhibition is not identical to the molecular inhibition mediated by SOCS3. Thus, new drugs have to be developed which would impart similar functions as the biological SOCS3 protein, and in this direction use of small peptides appears promising besides gene therapy.

The role of SOCS3 is to maintain cellular homeostasis and normal functioning of the cell. Since SOCS3 is found to be associated with many human diseases more extensive studies are required to decipher its beneficial role in disease prevention and identification of precise and effective targets with therapeutic potential. For this, an elaborate or genome wide studies using microarrays and miRNA analysis is to be carried out which may provide a much broader scope in extending translational research in this direction.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health research grants R01HL090580, R01HL104516, and R01HL112597 to DKA. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Rhee I, Bachman KE, Park BH, Jair KW, Yen RW, Schuebel KE, Cui H, Feinberg AP, Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Baylin SB, Vogelstein B. DNMT1 and DNMT3b cooperate to silence genes in human cancer cells. Nature. 2002;416:552–556. doi: 10.1038/416552a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paz MF, Wei S, Cigudosa JC, Rodriguez-Perales S, Peinado MA, Huang TH, Esteller M. Genetic unmasking of epigenetically silenced tumor suppressor genes in colon cancer cells deficient in DNA methyltransferases. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2209–2219. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballestar E, Esteller M. The epigenetic breakdown of cancer cells: from DNA methylation to histone modifications. Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 2005;38:169–181. doi: 10.1007/3-540-27310-7_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lopez-Serra L, Ballestar E, Fraga MF, Alaminos M, Setien F, Esteller M. A profile of methyl-CpG binding domain protein occupancy of hypermethylated promoter CpG islands of tumor suppressor genes in human cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8342–8346. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robertson KD, Ait-Si-Ali S, Yokochi T, Wade PA, Jones PL, Wolffe AP. DNMT1 forms a complex with Rb, E2F1 and HDAC1 and represses transcription from E2F-responsive promoters. Nat Genet. 2000;25:338–342. doi: 10.1038/77124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuks F, Hurd PJ, Wolf D, Nan X, Bird AP, Kouzarides T. The methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 links DNA methylation to histone methylation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4035–4040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210256200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matarazzo MR, De Bonis ML, Strazzullo M, Cerase A, Ferraro M, Vastarelli P, Ballestar E, Esteller M, Kudo S, D'Esposito M. Multiple binding of methyl-CpG and polycomb proteins in long-term gene silencing events. J Cell Physiol. 2007;210:711–719. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larsen F, Gundersen G, Lopez R, Prydz H. CpG islands as gene markers in the human genome. Genomics. 1992;13:1095–1107. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(92)90024-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coulondre C, Miller JH, Farabaugh PJ, Gilbert W. Molecular basis of base substitution hotspots in Escherichia coli. Nature. 1978;274:775–780. doi: 10.1038/274775a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bird A. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev. 2002;16:6–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.947102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gardiner-Garden M, Frommer M. CpG islands in vertebrate genomes. J Mol Biol. 1987;196:261–282. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90689-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takai D, Jones PA. Comprehensive analysis of CpG islands in human chromosomes 21 and 22. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3740–3745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052410099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshikawa T, Takata A, Otsuka M, Kishikawa T, Kojima K, Yoshida H, Koike K. Silencing of microRNA-122 enhances interferon-alpha signaling in the liver through regulating SOCS3 promoter methylation. Sci Rep. 2012;2:637. doi: 10.1038/srep00637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carrington JC, Ambros V. Role of microRNAs in plant and animal development. Science. 2003;301:336–338. doi: 10.1126/science.1085242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Lamb J, Peck D, Sweet-Cordero A, Ebert BL, Mak RH, Ferrando AA, Downing JR, Jacks T, Horvitz HR, Golub TR. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature. 2005;435:834–838. doi: 10.1038/nature03702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA-cancer connection: the beginning of a new tale. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7390–7394. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esteller M. Epigenetic gene silencing in cancer: the DNA hypermethylome. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16(Spec No 1):R50–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saetrom P, Snove O, Jr, Rossi JJ. Epigenetics and microRNAs. Pediatr Res. 2007;61:17R–23R. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e318045760e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu L, Zhou H, Zhang Q, Zhang J, Ni F, Liu C, Qi Y. DNA methylation mediated by a microRNA pathway. Mol Cell. 2010;38:465–475. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sato F, Tsuchiya S, Meltzer SJ, Shimizu K. MicroRNAs and epigenetics. FEBS J. 2011;278:1598–1609. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saito Y, Liang G, Egger G, Friedman JM, Chuang JC, Coetzee GA, Jones PA. Specific activation of microRNA-127 with downregulation of the proto-oncogene BCL6 by chromatin-modifying drugs in human cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:435–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lujambio A, Ropero S, Ballestar E, Fraga MF, Cerrato C, Setien F, Casado S, Suarez-Gauthier A, Sanchez-Cespedes M, Git A, Spiteri I, Das PP, Caldas C, Miska E, Esteller M. Genetic unmasking of an epigenetically silenced microRNA in human cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1424–1429. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ru P, Steele R, Hsueh EC, Ray RB. Anti-miR-203 Upregulates SOCS3 Expression in Breast Cancer Cells and Enhances Cisplatin Chemosensitivity. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:720–727. doi: 10.1177/1947601911425832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kornfeld JW, Baitzel C, Konner AC, Nicholls HT, Vogt MC, Herrmanns K, Scheja L, Haumaitre C, Wolf AM, Knippschild U, Seibler J, Cereghini S, Heeren J, Stoffel M, Bruning JC. Obesity-induced overexpression of miR-802 impairs glucose metabolism through silencing of Hnf1b. Nature. 2013;494:111–115. doi: 10.1038/nature11793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma N, Wang X, Qiao Y, Li F, Hui Y, Zou C, Jin J, Lv G, Peng Y, Wang L, Huang H, Zhou L, Zheng X, Gao X. Coexpression of an intronic microRNA and its host gene reveals a potential role for miR-483-5p as an IGF2 partner. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;333:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin S, Li H, Mu H, Luo W, Li Y, Jia X, Wang S, Jia X, Nie Q, Li Y, Zhang X. Let-7b regulates the expression of the growth hormone receptor gene in deletion-type dwarf chickens. BMC Genomics. 2012;13 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-306. 306-2164-13-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Surdziel E, Cabanski M, Dallmann I, Lyszkiewicz M, Krueger A, Ganser A, Scherr M, Eder M. Enforced expression of miR-125b affects myelopoiesis by targeting multiple signaling pathways. Blood. 2011;117:4338–4348. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-289058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bakre A, Mitchell P, Coleman JK, Jones LP, Saavedra G, Teng M, Tompkins SM, Tripp RA. Respiratory syncytial virus modifies microRNAs regulating host genes that affect virus replication. J Gen Virol. 2012;93:2346–2356. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.044255-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou Hanbing, Park Stanley, Housman Jonathan, Elia Leonardo, Lim Byung-Kwan, Yajima Toshitaka. MicroRNA-19a (miR-19a) Regulates gp130 Signaling by Inhibiting Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling-3 (SOCS3) Protein Translation. Circulation. 2009;120:S835. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gupta GK, Dhar K, Del Core MG, Hunter WJ, 3rd, Hatzoudis GI, Agrawal DK. Suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 and intimal hyperplasia in porcine coronary arteries following coronary intervention. Exp Mol Pathol. 2011;91:346–352. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dhar K, Rakesh K, Pankajakshan D, Agrawal DK. SOCS3 Promotor Hypermethylation and STAT3-NF-kB Interaction Downregulate SOCS3 Expression in Human Coronary Artery Smooth Muscle Cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00570.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Y, Deuring J, Peppelenbosch MP, Kuipers EJ, de Haar C, van der Woude CJ. IL-6-induced DNMT1 activity mediates SOCS3 promoter hypermethylation in ulcerative colitis-related colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:1889–1896. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He B, You L, Uematsu K, Matsangou M, Xu Z, He M, McCormick F, Jablons DM. Cloning and characterization of a functional promoter of the human SOCS-3 gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;301:386–391. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)03071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He B, You L, Uematsu K, Zang K, Xu Z, Lee AY, Costello JF, McCormick F, Jablons DM. SOCS-3 is frequently silenced by hypermethylation and suppresses cell growth in human lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14133–14138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2232790100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He B, You L, Xu Z, Mazieres J, Lee AY, Jablons DM. Activity of the suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 promoter in human non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2004;5:366–370. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2004.n.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weber A, Hengge UR, Bardenheuer W, Tischoff I, Sommerer F, Markwarth A, Dietz A, Wittekind C, Tannapfel A. SOCS-3 is frequently methylated in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and its precursor lesions and causes growth inhibition. Oncogene. 2005;24:6699–6708. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Isomoto H. Epigenetic alterations in cholangiocarcinoma-sustained IL-6/STAT3 signaling in cholangio- carcinoma due to SOCS3 epigenetic silencing. Digestion. 2009;79(Suppl 1):2–8. doi: 10.1159/000167859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martini M, Pallini R, Luongo G, Cenci T, Lucantoni C, Larocca LM. Prognostic relevance of SOCS3 hypermethylation in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:2955–2960. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lindemann C, Hackmann O, Delic S, Schmidt N, Reifenberger G, Riemenschneider MJ. SOCS3 promoter methylation is mutually exclusive to EGFR amplification in gliomas and promotes glioma cell invasion through STAT3 and FAK activation. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122:241–251. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0832-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feng Y, Wang Z, Bao Z, Yan W, You G, Wang Y, Hu H, Zhang W, Zhang Q, Jiang T. SOCS3 promoter hypermethylation is a favorable prognosticator and a novel indicator for G-CIMP-positive GBM patients. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91829. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tokita T, Maesawa C, Kimura T, Kotani K, Takahashi K, Akasaka T, Masuda T. Methylation status of the SOCS3 gene in human malignant melanomas. Int J Oncol. 2007;30:689–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tischoff I, Hengge UR, Vieth M, Ell C, Stolte M, Weber A, Schmidt WE, Tannapfel A. Methylation of SOCS-3 and SOCS-1 in the carcinogenesis of Barrett's adenocarcinoma. Gut. 2007;56:1047–1053. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.111633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Niwa Y, Kanda H, Shikauchi Y, Saiura A, Matsubara K, Kitagawa T, Yamamoto J, Kubo T, Yoshikawa H. Methylation silencing of SOCS-3 promotes cell growth and migration by enhancing JAK/STAT and FAK signalings in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2005;24:6406–6417. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berger H, Vegran F, Chikh M, Gilardi F, Ladoire S, Bugaut H, Mignot G, Chalmin F, Bruchard M, Derangere V, Chevriaux A, Rebe C, Ryffel B, Pot C, Hichami A, Desvergne B, Ghiringhelli F, Apetoh L. SOCS3 transactivation by PPARgamma prevents IL-17-driven cancer growth. Cancer Res. 2013;73:3578–3590. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilop S, van Gemmeren TB, Lentjes MH, van Engeland M, Herman JG, Brummendorf TH, Jost E, Galm O. Methylation-associated dysregulation of the suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 gene in multiple myeloma. Epigenetics. 2011;6:1047–1052. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.8.16167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liang P, Cheng SH, Cheng CK, Lau KM, Lin SY, Chow EY, Chan NP, Ip RK, Wong RS, Ng MH. Platelet factor 4 induces cell apoptosis by inhibition of STAT3 via up-regulation of SOCS3 expression in multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 2013;98:288–295. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.065607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takeuchi K, Sakai I, Narumi H, Yasukawa M, Kojima K, Minamoto Y, Fujisaki T, Tanimoto K, Hara M, Numata A, Gondo H, Takahashi M, Fujii N, Masuda K, Fujita S. Expression of SOCS3 mRNA in bone marrow cells from CML patients associated with cytogenetic response to IFN-alpha. Leuk Res. 2005;29:173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fodermayr M, Zach O, Huber M, Machherndl-Spandl S, Wolfl S, Bosmuller HC, Hasenschwandtner S, Burgstaller S, Krieger O, Lutz D, Weltermann A, Hauser H. The clinical impact of DNA methylation frequencies of JAK2 negative regulators in patients with essential thrombocythemia. Leuk Res. 2012;36:588–590. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fourouclas N, Li J, Gilby DC, Campbell PJ, Beer PA, Boyd EM, Goodeve AC, Bareford D, Harrison CN, Reilly JT, Green AR, Bench AJ. Methylation of the suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 gene (SOCS3) in myeloproliferative disorders. Haematologica. 2008;93:1635–1644. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Teofili L, Martini M, Cenci T, Guidi F, Torti L, Giona F, Foa R, Leone G, Larocca LM. Epigenetic alteration of SOCS family members is a possible pathogenetic mechanism in JAK2 wild type myeloproliferative diseases. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:1586–1592. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang MY, Fung TK, Chen FY, Chim CS. Methylation profiling of SOCS1, SOCS2, SOCS3, CISH and SHP1 in Philadelphia-negative myeloproliferative neoplasm. J Cell Mol Med. 2013;17:1282–1290. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jing Yu, Li-chun Zhao, Song-mei Yao, Cheng-yan He, Hong-jun Li, Xiang-bo Kong. Expression of SOCS-3 and Its Methylation in Renal Cancer. Chem Res Chinese Universities. 2011;27(3):464. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pierconti F, Martini M, Pinto F, Cenci T, Capodimonti S, Calarco A, Bassi PF, Larocca LM. Epigenetic silencing of SOCS3 identifies a subset of prostate cancer with an aggressive behavior. Prostate. 2011;71:318–325. doi: 10.1002/pros.21245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Middeldorf I, Galm O, Osieka R, Jost E, Herman JG, Wilop S. Sequence of administration and methylation of SOCS3 may govern response to gemtuzumab ozogamicin in combination with conventional chemotherapy in patients with refractory or relapsed acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) Am J Hematol. 2010;85:477–481. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Isomoto H, Mott JL, Kobayashi S, Werneburg NW, Bronk SF, Haan S, Gores GJ. Sustained IL-6/STAT-3 signaling in cholangiocarcinoma cells due to SOCS-3 epigenetic silencing. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:384–396. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kubo M, Inoue H. Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) in Th2 cells evokes Th2 cytokines, IgE, and eosinophilia. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2006;6:32–39. doi: 10.1007/s11882-006-0007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seki Y, Inoue H, Nagata N, Hayashi K, Fukuyama S, Matsumoto K, Komine O, Hamano S, Himeno K, Inagaki-Ohara K, Cacalano N, O'Garra A, Oshida T, Saito H, Johnston JA, Yoshimura A, Kubo M. SOCS-3 regulates onset and maintenance of T(H)2-mediated allergic responses. Nat Med. 2003;9:1047–1054. doi: 10.1038/nm896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kubo M, Hanada T, Yoshimura A. Suppressors of cytokine signaling and immunity. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1169–1176. doi: 10.1038/ni1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eriksen KW, Woetmann A, Skov L, Krejsgaard T, Bovin LF, Hansen ML, Gronbaek K, Billestrup N, Nissen MH, Geisler C, Wasik MA, Odum N. Deficient SOCS3 and SHP-1 expression in psoriatic T cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:1590–1597. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Trowbridge RM, Pittelkow MR. Epigenetics in the pathogenesis and pathophysiology of psoriasis vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:111–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gupta GK, Agrawal T, DelCore MG, Mohiuddin SM, Agrawal DK. Vitamin D deficiency induces cardiac hypertrophy and inflammation in epicardial adipose tissue in hypercholesterolemic swine. Exp Mol Pathol. 2012;93:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yasukawa H, Hoshijima M, Gu Y, Nakamura T, Pradervand S, Hanada T, Hanakawa Y, Yoshimura A, Ross J, Jr, Chien KR. Suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 is a biomechanical stress-inducible gene that suppresses gp130-mediated cardiac myocyte hypertrophy and survival pathways. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1459–1467. doi: 10.1172/JCI13939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yajima T, Murofushi Y, Zhou H, Park S, Housman J, Zhong ZH, Nakamura M, Machida M, Hwang KK, Gu Y, Dalton ND, Yajima T, Yasukawa H, Peterson KL, Knowlton KU. Absence of SOCS3 in the cardiomyocyte increases mortality in a gp130-dependent manner accompanied by contractile dysfunction and ventricular arrhythmias. Circulation. 2011;124:2690–2701. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.028498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mishra Vani, Sharma Rahul, Chattopadhyay Brajadulal, Paul Bhola Nath. Epigenetic modification of suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 in asthmatic mouse lung: role of interleukin-6. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science. 2011;01(05):81. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Verma M, Chattopadhyay BD, Kumar S, Kumar K, Verma D. DNA methyltransferase 1(DNMT1) induced the expression of suppressors of cytokine signaling3 (Socs3) in a mouse model of asthma. Mol Biol Rep. 2014;41:4413–4424. doi: 10.1007/s11033-014-3312-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Verma M, Chattopadhyay BD, Paul BN. Epigenetic regulation of DNMT1 gene in mouse model of asthma disease. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40:2357–2368. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2317-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zafra MP, Mazzeo C, Gamez C, Rodriguez Marco A, de Zulueta A, Sanz V, Bilbao I, Ruiz-Cabello J, Zubeldia JM, del Pozo V. Gene silencing of SOCS3 by siRNA intranasal delivery inhibits asthma phenotype in mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91996. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Emanuelli B, Peraldi P, Filloux C, Sawka-Verhelle D, Hilton D, Van Obberghen E. SOCS-3 is an insulin-induced negative regulator of insulin signaling. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15985–15991. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.21.15985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mashili F, Chibalin AV, Krook A, Zierath JR. Constitutive STAT3 phosphorylation contributes to skeletal muscle insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2013;62:457–465. doi: 10.2337/db12-0337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jiang C, Kim JH, Li F, Qu A, Gavrilova O, Shah YM, Gonzalez FJ. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha regulates a SOCS3-STAT3-adiponectin signal transduction pathway in adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:3844–3857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.426338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang C, Dai J, Yang M, Deng G, Xu S, Jia Y, Boden G, Ma ZA, Yang G, Li L. Silencing of FGF-21 expression promotes hepatic gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis by regulation of the STAT3-SOCS3 signal. FEBS J. 2014;281:2136–2147. doi: 10.1111/febs.12767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ghosh A, Pahan K. Gemfibrozil, a lipid-lowering drug, induces suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 in glial cells: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:27189–27203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.346932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bode JG, Ludwig S, Ehrhardt C, Albrecht U, Erhardt A, Schaper F, Heinrich PC, Haussinger D. IFN-alpha antagonistic activity of HCV core protein involves induction of suppressor of cytokine signaling-3. FASEB J. 2003;17:488–490. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0664fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Blalock EL, Chien H, Dix RD. Murine cytomegalovirus downregulates interleukin-17 in mice with retrovirus-induced immunosuppression that are susceptible to experimental cytomegalovirus retinitis. Cytokine. 2013;61:862–875. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Navid Fatemeh, Yu Chengrong, Dambuza Ivy, Frank Gregory M, Egwuagu Charles E. STAT3/SOCS3 axis modulates CD8-mediated host immunity against HSV-1. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:5989. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boe A, Baiocchi M, Carbonatto M, Papoian R, Serlupi-Crescenzi O. Interleukin 6 knock-out mice are resistant to antigen-induced experimental arthritis. Cytokine. 1999;11:1057–1064. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shouda T, Yoshida T, Hanada T, Wakioka T, Oishi M, Miyoshi K, Komiya S, Kosai K, Hanakawa Y, Hashimoto K, Nagata K, Yoshimura A. Induction of the cytokine signal regulator SOCS3/CIS3 as a therapeutic strategy for treating inflammatory arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1781–1788. doi: 10.1172/JCI13568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li X, Liu H, Qin L, Tamasi J, Bergenstock M, Shapses S, Feyen JH, Notterman DA, Partridge NC. Determination of dual effects of parathyroid hormone on skeletal gene expression in vivo by microarray and network analysis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:33086–33097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Steelman LS, Pohnert SC, Shelton JG, Franklin RA, Bertrand FE, McCubrey JA. JAK/STAT, Raf/MEK/ERK, PI3K/Akt and BCR-ABL in cell cycle progression and leukemogenesis. Leukemia. 2004;18:189–218. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rawlings JS, Rosler KM, Harrison DA. The JAK/STAT signaling pathway. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:1281–1283. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cacalano NA, Sanden D, Johnston JA. Tyrosine-phosphorylated SOCS-3 inhibits STAT activation but binds to p120 RasGAP and activates Ras. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:460–465. doi: 10.1038/35074525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Babon JJ, Kershaw NJ, Murphy JM, Varghese LN, Laktyushin A, Young SN, Lucet IS, Norton RS, Nicola NA. Suppression of cytokine signaling by SOCS3: characterization of the mode of inhibition and the basis of its specificity. Immunity. 2012;36:239–250. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]