Abstract

Background

Our understanding of the conditions that influence substance abuse treatment retention in urban African American substance users is limited. This study examined the interacting effect of circumstances, motivation, and readiness (CMR) with distress tolerance to predict substance abuse treatment retention in a sample of urban African American treatment-seeking substance users.

Methods

Data were collected from 81 African American substance users entering residential substance abuse treatment facility in an urban setting. Participants completed self-reported measures on CMR and distress tolerance. In addition, participants were assessed on psychiatric comorbidities, substance use severity, number of previous treatments, and demographic characteristics. Data on substance abuse treatment retention were obtained using administrative records of the treatment center.

Results

Logistic regression analysis found that the interaction of CMR and distress tolerance was significant in predicting substance abuse treatment retention. Higher score on CMR was significantly associated with increased likelihood of treatment retention in substance users with higher distress tolerance, but not in substance users with lower distress tolerance.

Conclusions

Findings of the study indicate that at higher level of distress tolerance, favorable external circumstances, higher internal motivation, and greater readiness to treatment are important indicators of substance abuse treatment retention. The study highlights the need for assessing CMR and distress tolerance levels among substance users entering treatment, and providing targeted interventions to increase substance abuse treatment retention and subsequent recovery from substance abuse among urban African American substance users.

Keywords: Residential Treatment Dropout, Treatment Completion, Substance Use Disorders, Minority, Stages of Change

1. Introduction

Chronic substance use is a major public health concern, with substance use disorders costing more than half a trillion dollars a year in medical, economic, criminal, and social costs, and contributing to more than 100,000 deaths in the United States (U.S.; National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA], 2010). Conversely, substance abuse treatment is linked to decreases in substance use and criminal activity, as well as improvement in occupational, social, and psychological functioning (Hubbard, Craddock, & Anderson, 2003; McCusker, Stoddard, Frost, & Zorn, 1996; Simpson, Joe, & Brown, 1997). Despite the knowledge that receipt and completion of substance abuse treatment ameliorate substance use problems, only a small proportion of the population in need of substance abuse treatment actually receives any specialty treatment at drug and alcohol rehabilitation facility, hospital, or mental health center (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2014; Han, Clinton-Sherrod, Gfroerer, Pemberton, & Calvin, 2011).

Further, racial differences have been noted among those receiving substance abuse treatment. African American treatment-seeking substance users experience higher risk for dropping out of substance abuse treatment programs compared to their White counterparts (Bluthenthal, Jacobson, & Robinson, 2007; Jacobson, Robinson, & Bluthenthal, 2007; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2009). In residential treatment facilities that offer integrated substance abuse and mental health services, the increased risk of treatment dropout among African American substance users remains even after accounting for important individual characteristics, such as sex, types of substance abuse disorders, and mental health disorders (Choi, Adams, MacMaster, & Seiters, 2013). The rate of dropout is especially high among African American residential treatment-seek substance users in urban settings (Lejuez et al., 2008), suggesting that this high-risk population in intensive treatment often does not receive adequate treatment. Although a great deal of research has been conducted to understand factors related to substance abuse treatment retention, less is known about the underlying psychosocial factors that influence treatment retention in urban African American substance users.

The constructs of circumstances (i.e., external conditions that affects decision to change a behavior), motivation (i.e., internal recognition of the need to change a behavior), and readiness (i.e., availability and desire for changed behavior) have been identified as significant predictors of substance abuse treatment retention (de Leon, Melnick, Kressel, & Jainchill, 1994). These constructs conceptually align with the Stages of Change model, which states that behavior change occurs through a series of steps consisting of pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation for change, action, and maintenance (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1984). Conceptually, circumstances and motivation subscales correspond to pre-contemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages of the Stages of Change model, and readiness correspond to action and maintenance stages of the Stages of Change model. With this perspective, an individual in pre-action stages develops goals to change substance use behavior and commits to seek substance abuse treatment based on external circumstances (e.g., family relationships, finances) and internal motivation. Gradually, the person moves to action stage of completing substance abuse treatment program based on readiness to treatment.

The constructs of circumstances, motivation, and readiness are highly correlated, and combined, they have good predictive validity with respect to retention in treatment (Soyez, De Leon, Broekaert, & Rosseel, 2006). Consistent with previous research, the current study investigated the total effect of circumstances, motivation, and readiness (hereinafter referred to as CMR). Research has repeatedly shown that higher CMR significantly improves the likelihood of substance abuse treatment entry and retention (Cunningham, Sobell, Sobell, & Gaskin, 1994; Melnick, De Leon, Hawke, Jainchill, & Kressel, 1997). Although a strong predictor, CMR does not fully explain substance abuse treatment retention (Soyez et al., 2006). To further elucidate treatment retention, theoretical and empirical evidence provides support for the conditional effect of distress tolerance on the relationship between CMR and substance abuse treatment retention.

Grounded in the Negative Reinforcement Model, distress tolerance is defined as an individual’s ability to withstand negative emotional states (Simons & Gaher, 2005). The Negative Reinforcement Model suggests that substance use provides perceived and/or actual relief from negative moods, such as feelings of irritability, anxiety, stress, and depression, which reinforces the behavior and increases the likelihood of substance use in the future (Baker, Piper, McCarthy, Majeskie, & Fiore, 2004). This perspective may be extended to the study of substance abuse treatment retention. Substance users in residential settings experience unpleasant and uncomfortable emotions due to their experiences with difficulties in adjusting to a structured environment, withdrawal symptoms and drug cravings (Bartels & Drake, 1996; Baker et al., 2004). Distress tolerance may resemble the ability to cope with negative affect and stress experienced by treatment-seeking substance users in residential substance abuse treatment. Thus, a substance user may need higher distress tolerance, in addition to greater CMR, in order to complete substance abuse treatment program.

In support of the moderating effect of distress tolerance, a few studies have investigated the relations of negative affects with substance use outcomes at varying levels of distress tolerance (Ali, Ryan, Beck, & Daughters, 2013; Gorka, Ali, & Daughters, 2012). The aim of the current study was to examine whether distress tolerance moderates the relationship between CMR and substance abuse treatment retention in urban African American substance users. We hypothesize that urban African American treatment-seeking substance users with greater CMR are more likely to remain in substance abuse treatment if they also evidence higher distress tolerance, but not if they exhibit lower distress tolerance. Thus, CMR predicts substance abuse treatment retention more among those who can tolerate the challenges of the treatment program (i.e., high distress tolerance) than those with low distress tolerance.

2. Materials and Method

2. 1. Participants

The sample included 81 participants recruited from a residential treatment center. The selected residential treatment center offered various contract durations (i.e., 28, 30, 60, 90, and 180 days), but majority of the participants in the study were provided 28 or 30 days of treatment (81.5%). Treatment at this facility consisted of several strategies adopted from Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous, as well as group sessions that focused on relapse prevention and functional analysis. Prior to coming to this treatment facility, clients were required to abstain from any substance use for at least three days. At the center, clients were required to maintain complete abstinence from drugs and alcohol, and regular drug testing was conducted. Any use of substances was grounds for dismissal from the center.

2.2. Procedure

As a standard practice, all clients completed an intake-screening interview administered by doctoral-level graduate students and senior research staff. The intake-screening interview assessed psychiatric comorbidities, substance use severity, and demographic information. These measures are described in detail below. At the end of the intake-screening interview, clients were invited to take part in research. Inclusion criteria included African American treatment-seeking substance user and ability to speak and read English sufficiently to complete study procedures. Exclusion criterion included any diagnosed psychotic symptoms in the past twelve months that might potentially affect responses on the self-report measures.

Data collection occurred between September 2014 and April 2015. Participants were recruited within 10 days of their treatment entry at the center. Upon providing informed consent for the current study, participants completed a battery of self-report measures, including CMR, distress tolerance, and previous treatments. The measures were administered on a lab computer using a secured anonymous web-based survey tool, Qualtrics Labs, Inc. version 2009 (Qualtrics Labs, Inc., 2012). Information regarding psychiatric comorbidities, substance use severity, and demographic characteristics were obtained from the intake-screening assessment. Participants’ treatment retention information was obtained from the administrative offices at the treatment center. The study was reviewed and approved by the University Institutional Review Board.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Substance Abuse Treatment Retention

Substance abuse treatment retention, the dependent variable, was coded dichotomously (yes versus no). Treatment non-retention was defined as voluntarily leaving treatment against treatment center staff’s recommendations; or being asked to leave treatment due to engagement in treatment-interfering behaviors, such as using substances, breaking rules at the treatment facility, violent or aggressive behavior, selling of substances, or having sexual relations with other clients.

2.3.2. Circumstances, Motivation, and Readiness (CMR)

The CMR measure was the primary independent variable in the study. This information was assessed using an 18-item CMR scale (de Leon, 1993). Participants were asked to respond on a 5-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” The mean of these items determined participants’ external circumstances (e.g., “I believe that my family/relationship will try to make me leave treatment” and “I am worried that I will have serious money problems if I stay in treatment”), internal motivation (e.g., “Basically, I feel that my drug use is a very serious problem in my life” and “It is more important to me than anything else that I stop using drugs”), and readiness to treatment (e.g., “I came to this program because I really feel that I’m ready to deal with myself in treatment” and “I’ll do whatever I have to do to get my life straightened out”). The scale demonstrated good internal consistency in the current study (α = 0.83).

2.3.3. Distress Tolerance

Distress tolerance was measured using the Distress Tolerance Scale (Simons & Gaher, 2005). In this 15-item measure, participants were asked to rate items on a 5-point Likert scale to assess one’s perceived ability to endure negative emotional states (e.g., “Feeling distressed or upset is unbearable to me” and “My feelings of distress are so intense that they completely take over”). The mean of the items measured participants’ distress tolerance levels. This scale showed excellent internal consistency in this study (α = 0.92).

2.3.4. Potential Covariates

The following potential confounders were considered: psychiatric comorbidities (Axis I disorders and Axis II disorders), substance use severity, number of previous treatments, and demographic characteristics.

Axis I disorders were indexed on the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID-IV; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1995) for the following disorders: major depressive disorder, bipolar I disorder, psychotic symptoms, panic disorder, social phobia, obsessive compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder. Axis II disorders only included antisocial personality disorder and borderline personality disorder, since they are prevalent among substance users (Kokkevi, Stefanis, Anastasopoulou, & Kostogianni, 1998; Torrens, Gilchrist, & Domingo-Salvany, 2011). The SCID-IV has previously demonstrated good intra-rater and test-retest reliability (Williams, Gibbon, First, & Spitzer, 1992). Psychiatric comorbidities were measured as the total number of diagnosed psychiatric disorders, ranging from 0 to 10.

Substance use severity consisted of drug use frequency in the past year on a 5-point scale, ranging from “never” to “4 or more times a week.” For the analysis, the scale was coded dichotomously as monthly or less versus more than monthly use. The substance categories were marijuana, alcohol, cocaine (not crack), crack, ecstasy, methamphetamines, sedatives, heroin, illegal prescriptions, and PCP. Sum of the number of drugs used monthly was regarded as the substance use severity score. Substance use severity ranged from 0–10. Previous treatments consisted of the number of times participants had previously attended residential substance abuse treatment programs for drugs or alcohol.

Participants’ basic demographic information included sex, age in years, education level, marital status, and court-mandated status. Sex was indicated as either male or female. Education was coded as less than or some high school, GED, and high school graduate or higher. Marital status was coded as married/living with someone or unmarried, which consisted of never married, divorced, separated, and widowed. Court-mandated to attend treatment was coded dichotomously (yes versus no).

2.4. Data analysis plan

Data were downloaded or entered, as appropriate, and analyzed using SPSS version 22. All continuous data were assessed for normality. Prior to conducting any inferential statistics, descriptive analyses were performed on all study variables.

The primary independent variable, the moderator, and the potential covariates were examined for their relationship with the dependent variable using chi-square or t-test, as appropriate. The main effects of CMR and distress tolerance, and the interactive effect of CMR with distress tolerance on substance abuse treatment retention were analyzed using a logistic regression model. In order to probe for significant interaction effect, simple slope analysis was performed to examine the relation between CMR and substance abuse treatment retention at the varying levels of distress tolerance (high and low).

2.5. Missing Data

Missing data were noted in substance use severity (n = 2). The sample mean of substance use severity, 1.53, was entered for missing substance use severity values. In addition, previous treatments had an extreme outlier, which was replaced with the sample mean of previous treatments, 2.44.

3. Results

3.1. Univariate Analysis

The majority of the sample was male (71.6%), with the mean age of 41.02 years (SD = 12.35). Half of the sample was high school graduate or higher (50.6%), followed by some or less than high school (27.2%) and GED (22.2%). The majority of the sample was unmarried (92.6%) and unemployed (76.5%). These demographic characteristics reflect the low socioeconomic status of the sample. In the study, retention in substance abuse treatment was observed in 70.4% of the participants. Reasons for dropping out of substance abuse treatment included clinical discharge (19.8%), voluntary withdrawal (7.4%), and jail (2.5%). The mean scores of CMR and distress tolerance were 3.65 (SD = 0.73) and 2.96 (SD = 1.04), respectively.

3.2. Bivariate Analysis

T-test analyses showed that substance abuse treatment retention was neither related to CMR [t(31.32) = −1.17, p = 0.25] nor distress tolerance [t(79) = 1.27, p = 0.21]. As noted in Table 1, none of the covariates were statistically significantly related to substance abuse treatment retention. Therefore, no covariates were included in the subsequent logistic regression model.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics by retention in substance abuse treatment (N=81).

| Retention | Non-Retention | Statistical Test | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | %/Mean(SD) | n | %/Mean(SD) | |||

| Sex | χ2(1)=0.96 | 0.33 | ||||

| Male | 39 | 68.4% | 19 | 79.2% | ||

| Female | 18 | 31.6% | 5 | 20.8% | ||

| Highest education | χ2(2)=1.33 | 0.51 | ||||

| Some or less than high school | 15 | 26.3% | 7 | 29.2% | ||

| GED | 11 | 19.3% | 7 | 29.2% | ||

| High school graduate or higher | 31 | 54.4% | 10 | 41.7% | ||

| Marital statusa | – | 0.17 | ||||

| Married | 6 | 10.5% | 0 | 0.0% | ||

| Unmarried | 51 | 89.5% | 24 | 100.0% | ||

| Court-mandated treatment | χ2(1)=0.37 | 0.55 | ||||

| Yes | 35 | 61.4% | 13 | 54.2% | ||

| No | 22 | 38.6% | 11 | 45.8% | ||

| Age in years | 57 | 42.42(12.10) | 24 | 37.71(12.57) | t(79)=−1.58 | 0.12 |

| Number of previous treatments | 57 | 2.64(1.93) | 24 | 1.96(1.99) | t(79)= −1.44 | 0.16 |

| Psychiatric comorbidities | 57 | 1.39(1.45) | 24 | 1.21(1.84) | t(79)= −0.46 | 0.64 |

| Substance use severity level | 57 | 1.62(0.86) | 24 | 1.31(0.75) | t(79)= −1.54 | 0.13 |

Fisher’s Exact Test was used due to the small cell size of less than 5.

3.3. Multivariate Analysis

The CMR and distress tolerance scores were centered (i.e., each participant’s CMR and distress tolerance scores were subtracted from the means) to allow meaningful and interpretable results. The CMR and distress tolerance scores were entered in Step 1, and the interaction term of CMR by distress tolerance was entered in Step 2. As shown in Table 2, Step 1 with main effects was not a significant model for substance abuse treatment retention [χ2(2) = 3.14, p = 0.21]. However, the final model with the interaction effect was a significant model for predicting substance abuse treatment retention [χ2(3) = 7.13, p = 0.01]. The interaction of CMR with distress tolerance was significant in predicting the increased likelihood of substance abuse treatment retention (b = 0.98, Wald = 4.65, p = 0.03).

Table 2.

Circumstances, motivation, and readiness by distress tolerance predicting substance abuse treatment retention (N=81).

| b | SE | Wald | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-value | Model Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | χ2(2)=3.14, p=0.21 | ||||||

| CMR | 0.41 | 0.34 | 1.52 | 1.51 | 0.78–2.92 | 0.22 | |

| DT | −0.27 | 0.24 | 1.24 | 0.77 | 0.48–1.22 | 0.27 | |

| Step 2 | χ2(3)=7.13, p=0.01 | ||||||

| CMR | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.91 | 1.52 | 0.65–3.56 | 0.34 | |

| DT | −0.13 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.88 | 0.52–1.50 | 0.64 | |

| CMR by DT | 0.98 | 0.45 | 4.65 | 2.66 | 1.09–6.45 | 0.03 |

Note. CMR = Circumstances, Motivation, and Readiness; DT = Distress Tolerance

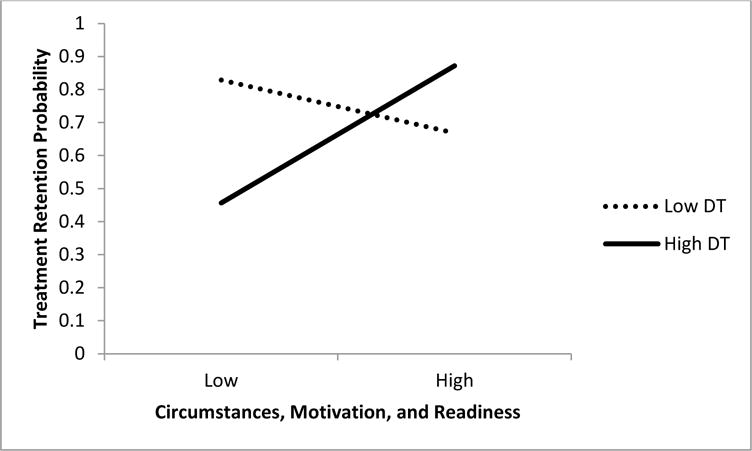

To further examine the effect of distress tolerance on the association between CMR and substance abuse treatment retention, two post-hoc regressions were performed. These regression models incorporated the main effect of CMR, the conditional effect of distress tolerance, and the interaction of the two variables to generate the slope of high distress tolerance (1 SD above the mean) and the slope of low distress tolerance (1 SD below the mean) (Aiken and West, 1991; Holmbeck, 2002). Results indicated that higher score on CMR was associated with increased likelihood of substance abuse treatment retention in individuals with high (b = 1.43, Wald = 4.47, p = 0.03), but not low (b = −0.60, Wald = 0.98, p = 0.32) distress tolerance. Specifically, among those with high distress tolerance, the odds of substance abuse treatment retention increased multiplicatively by 4.17 for every one-unit increase in CMR. Figure 1 provides graphical illustration of the relationship between CMR and substance abuse treatment retention by distress tolerance level.

Figure 1.

The relation of circumstances, motivation and readiness (CMR) on substance abuse treatment retention as a function of distress tolerance.

Note. DT = Distress Tolerance. All values are standardized. Low distress tolerance is 1 standard deviation below the mean. High distress tolerance is 1 standard deviation above the mean.

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Findings

Despite a need to better understand and increase substance abuse treatment retention in urban African American treatment-seeking substance users, there is a gap in research to study the interplay between psychosocial factors that influence substance abuse treatment retention. To that end, the current study investigated the moderating role of distress tolerance in the relation between CMR and substance abuse treatment retention in a sample of urban African American treatment-seeking substance users. Consistent with the study hypothesis, the effect of CMR on substance abuse treatment retention was significant in individuals with higher, but not lower, distress tolerance, suggesting that individuals who enter substance abuse treatment with higher level of self-awareness of their substance use problem and a strong desire to change their substance use behavior may not necessarily be able to complete treatment if they lack the skills to deal with negative affect. It is widely accepted that recognition of a behavior problem and desire for help are critical cognitive indicators of therapeutic engagement, such as confidence and commitment to treatment (Rosen, Hiller, Webster, Staton, & Leukefeld, 2004). The current study expands this knowledge by underscoring higher distress tolerance, together with favorable external circumstances, internal motivation, and readiness for treatment, as significant for substance abuse treatment retention.

Previous research has highlighted a positive association of CMR on substance abuse treatment retention (de Leon et al., 1994); however, the current study did not find a significant main effect of CMR on substance abuse treatment retention. Prior work on CMR is predominately based on samples that are dissimilar from the current study sample, such as larger sample size with a smaller proportion of African American substance users (de Leon et al., 1994; Simpson, Joe, Rowan-Szal, & Greener, 1995). The inconsistent finding across studies suggests that the effect of CMR on treatment outcome may differ in different populations. It has been noted that African American with substance dependence report lower socioeconomic status than White substance dependents (Lê Cook & Alegría, 2011). Thus, among African American substance users, experiences with socioeconomic disparities (Broman, Neighbors, Delva, Torres, & Jackson, 2008; Jacobson et al., 2007; SAMHSA, 2008), such as living in urban, unhealthy areas with high levels of poverty, and low education levels may influence their CMR levels and treatment outcomes.

Moreover, previous research has found a positive effect of higher distress tolerance on substance abuse treatment retention (Daughters et al., 2005), which was also not supported in this study. This association has been identified using a measure of behavioral distress tolerance rather than a measure of self-reported distress tolerance, as used in the study. Self-reported distress tolerance is regarded as the perceived ability to tolerate physical/psychological distress, while behavioral distress tolerance is the actual persistence in a goal-oriented task in the face of physical/psychological distress (Leyro, Zvolensky, & Bernstein, 2010). Self-reported and behavioral distress tolerance measures display weak association with one another (McHugh et al., 2011), suggesting that an individual’s perceived distress tolerance does not map well onto his/her actual ability to tolerate distress in a simulated environment.

Consistent with previous research on African American substance users (Daughters et al., 2005; Lejuez et al., 2008), the current study did not find number of previous treatments, substance use severity and demographic characteristics as important covariates. The current study also examined previously identified covariates, namely psychiatric comorbidities and court-mandated treatment status (Bornovalova, Lejuez, Daughters, Rosenthal, & Lynch, 2005; Lejuez et al., 2008; Tull & Gratz, 2012), but did not find them as significantly linked to substance abuse treatment retention. It is important to note that the analyses were conducted on a small sample that was recruited over the course of the study, and that might have limited the power to deduct significant covariates. Further, previous studies have investigated specific disorders in relation to substance abuse treatment retention, such as major depressive disorder, social phobia disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and borderline personality disorder. Whereas in this study, psychiatric comorbidities were included as a single composite measure consisting of the total number of Axis I and Axis II disorders. There may be specific disorders that place individuals at greater risk for treatment non-completion.

4.2. Limitations

Although this study addresses an important gap in the literature, there are some limitations to be noted. This study did not examine unique effects of external circumstances, internal motivation, and readiness for treatment on substance abuse treatment retention, and instead considered them together. Some studies have highlighted that motivation individually, as well as readiness, are significantly associated with substance abuse treatment retention (de Leon et al., 1994; Joe, Simpson, & Broome, 1999; Simpson & Joe, 1993). Future research may extrapolate the interacting effects of distress tolerance with external circumstances, internal motivation, and readiness for treatment on predicting substance abuse treatment retention. The current study utilized CMR measure for assessing Stages of Change. Although the CMR measure approximates the phases in the Stages of Change model, it does not represent all stages in the model, namely pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance, and termination. Other measures consistent with the Stages of Change model, such as Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale (Miller, & Tonigan, 1996), may be applied to replicate the findings of the current study.

The current study utilized SCID DSM-IV diagnoses to assess psychiatric comorbidities. Considering the changes with DSM-V diagnostic criteria for Axis I and Axis II disorders (First, Williams, Karg, & Spitzer, 2015), the study may be replicated using SCID DSM-V diagnoses. Further, the study was not powered to detect the association of CMR and distress tolerance with specific dropout reason (i.e., clinical discharge, voluntary withdrawal, and jail). Future research should examine this relationship in a sample with higher rates of clinical discharge, voluntary withdrawal, and return to jail. Moreover, given that treatments vary across substance abuse treatment programs, findings from this study may not generalize to substance users in other settings. However, the current study included urban African American treatment-seeking substance users who are at an increased risk for poor substance use outcomes, including low retention in substance abuse treatment (Bluthenthal et al., 2007; Jacobson et al., 2007).

4.3. Study Implications

Substance abuse treatment retention is a vital component for improved substance use outcomes. The findings of this study inform substance abuse treatment programs that favorable circumstances, increased motivation and readiness for treatment, combined with higher distress tolerance, are important for increasing substance abuse treatment retention in urban African American treatment-seeking substance users. Individuals in substance abuse treatment programs can be provided with specific interventions aimed at increasing treatment retention, and subsequently, improving their treatment outcomes.

Substance abuse treatment programs may adopt an early assessment tool to identify those at risk for leaving treatment prematurely and provide targeted intervention to those individuals. As the Stages of Change model is regarded as fluctuating over the course of treatment (DiClemente, 2005), substance abuse treatment programs may benefit from frequent assessments of CMR levels in treatment-seeking substance users and tailoring treatment to their stage. Individuals entering substance abuse treatment with low CMR may benefit from Motivational Interviewing aimed at increasing motivation and readiness to change substance use behavior and increasing participation in treatment (Allen & Olson, 2016; Carroll et al., 2006). Further, with emerging work suggesting that distress tolerance is a malleable characteristic (Leyro et al., 2010), this study highlights distress tolerance as a potential risk factor for low likelihood of retention in substance abuse treatment programs. Therefore, within the context of CMR, efforts that focus on distress tolerance skills or coping strategies to reduce negative affect, such as Skills for Improving Distress Tolerance (Bornovalova, Gratz, Daughters, Hunt, & Lejuez, 2012) and Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention program (Bowen et al., 2009), may increase substance abuse treatment retention.

Highlights.

We examined the underlying conditions of substance abuse treatment retention.

Greater circumstances, motivation, readiness, and distress tolerance are important.

Identification of those at-risk will allow a targeted intervention.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

Funding for this study was provided by NIH GRANT RO1 DA026424; the NIH had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

BA designed the study, conducted literature review, analyzed the data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. KMG and CWL supervised the study. KMG, SBD, and CWL gave technical support and conceptual advice. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict declared

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Allen RS, Olson BD. The what and why of effective substance abuse treatment. International Journal of Mental Health And Addiction. 2016;14(5):715–727. [Google Scholar]

- Ali B, Ryan JS, Beck KH, Daughters SB. Trait aggression and problematic alcohol use among college students: The moderating effect of distress tolerance. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37(12):2138–2144. doi: 10.1111/acer.12198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review. 2004;111:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels SJ, Drake RE. A pilot study of residential treatment for dual diagnoses. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1996;184(6):379–381. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199606000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluthenthal RN, Jacobson JO, Robinson PL. Are racial disparities in alcohol treatment completion associated with racial differences in treatment modality entry? Comparison of outpatient treatment and residential treatment in Los Angeles County, 1998 to 2000. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(11):1920–1926. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Gratz KL, Daughters SB, Hunt ED, Lejuez CW. Initial RCT of a distress tolerance treatment for individuals with substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;122(1–2):70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova M, Lejuez C, Daughters S, Rosenthal M, Lynch T. Impulsivity as a common process across borderline personality and substance use disorders. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:790–812. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen S, Chawla N, Collins SE, Witkiewitz K, Hsu S, Grow J, Marlatt A. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for substance use disorders: A pilot efficacy trial. Substance Abuse. 2009;30(4):295–305. doi: 10.1080/08897070903250084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman CL, Neighbors HW, Delva J, Torres M, Jackson JS. Prevalence of substance use disorders among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks in the national survey of American life. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(6):1107–1114. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.100727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Ball SA, Nich C, Martino S, Frankforter TL, Farentinos C, Woody GE. Motivational interviewing to improve treatment engagement and outcome in individuals seeking treatment for substance abuse: A multisite effectiveness study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;81(3):301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Adams SM, MacMaster SA, Seiters J. Predictors of residential treatment retention among individuals with co-occurring substance abuse and mental health disorders. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2013;45(2):122–131. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2013.785817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JA, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Gaskin J. Alcohol and drug abusers’ reasons for seeking treatment. Addictive Behaviors. 1994;19(6):691–696. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughters SB, Lejuez CW, Bornovalova MA, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Brown RA. Distress tolerance as a predictor of early treatment dropout in a residential substance abuse treatment facility. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:728–734. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leon G. Circumstances, Motivation, and Readiness (CMR) Scales for Substance Abuse Treatment. New York City: Center for Therapeutic Community Research at NDRI, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- de Leon G, Melnick G, Kressel D, Jainchill N. Circumstances, motivation, readiness, and suitability (the CMRS scales): Predicting retention in therapeutic community treatment. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1994;20(4):495–515. doi: 10.3109/00952999409109186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC. Conceptual models and applied research: The ongoing contribution of the Transtheoretical Model. Journal of Addictions Nursing. 2005;16(1–2):5–12. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Williams JBW, Karg RS, Spitzer RL. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders (SCID-5-CV) Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gorka SM, Ali B, Daughters SB. The role of distress tolerance in the relationship between depressive symptoms and problematic alcohol use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26:621–626. doi: 10.1037/a0026386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B, Clinton-Sherrod M, Gfroerer J, Pemberton MR, Calvin SL. CBHSQ Data Review. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2011. State and sociodemographic variations in substance use treatment need and receipt in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard RL, Craddock S, Anderson J. Overview of 5-year followup outcomes in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Studies (DATOS) Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;25(3):125–134. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson JO, Robinson PL, Bluthenthal RN. Racial disparities in completion rates from publicly funded alcohol treatment: Economic resources explain more than demographics and addiction severity. Health Services Research. 2007;42(2):773–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00612.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe G, Simpson DD, Broome K. Retention and patient engagement models for different treatment modalities in DATOS. Drug Alcohol Dependence. 1999;57(2):113–125. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokkevi AA, Stefanis NN, Anastasopoulou EE, Kostogianni CC. Personality disorders in drug abusers: Prevalence and their association with AXIS I disorders as predictors of treatment retention. Addictive Behaviors. 1998;23(6):841–854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lê Cook B, Alegría M. Racial-ethnic disparities in substance abuse treatment: The role of criminal history and socioeconomic status. Psychiatric Services. 2011;62(11):1273–1281. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.11.1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Zvolensky MJ, Daughters SB, Bornovalova MA, Paulson A, Tull MT, Otto MW. Anxiety sensitivity: A unique predictor of dropout among inner-city heroin and crack/cocaine users in residential substance use treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46(7):811–818. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyro TM, Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A. Distress tolerance and psychopathological symptoms and disorders: A review of the empirical literature among adults. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136(4):576–600. doi: 10.1037/a0019712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCusker J, Stoddard A, Frost R, Zorn M. Planned versus actual duration of drug abuse treatment. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1996;184(8):482–489. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199608000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh R, Daughters SB, Lejuez CW, Murray HW, Hearon BA, Gorka SM, Otto MW. Shared variance among self-report and behavioral measures of distress intolerance. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2011;35(3):266–275. doi: 10.1007/s10608-010-9295-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnick G, De Leon G, Hawke J, Jainchill N, Kressel D. Motivation and readiness for therapeutic community treatment among adolescents and adult substance abusers. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1997;23(4):485–506. doi: 10.3109/00952999709016891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Assessing drinkers’ motivation for change: The Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale (SOCRATES) Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1996;10(2):81–89. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drugs, brains, and behavior: The science of addiction. 2010 Retrieved August 1, 2013, from http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/science-addiction.

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. The Transtheoretical Approach: Crossing Traditional Boundaries of Therapy. Homewood, Ill: Dow Jones-Irwin; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Qualtrics Labs, Inc. computer program. Qualtrics Labs, Inc.; Provo, UT: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen PJ, Hiller ML, Webster J, Staton M, Leukefeld C. Treatment motivation and therapeutic engagement in prison-based substance use treatment. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2004;36(3):387–396. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2004.10400038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons J, Gaher R. The Distress Tolerance Scale: Development and validation of a self-report measure. Motivation and Emotion. 2005;29:83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW. Motivation as a predictor of early dropout from drug abuse treatment. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 1993;30(2):357–368. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW, Brown BS. Treatment retention and follow-up outcomes in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS) Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1997;11(4):294–307. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW, Rowan-Szal G, Greener J. Client engagement and change during drug abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1995;7(1):117–134. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(95)90309-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soyez V, De Leon G, Broekaert E, Rosseel Y. The impact of a social network intervention on retention in Belgian therapeutic communities: A quasi-experimental study. Addiction. 2006;101(7):1027–1034. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Prevalence of substance use among racial & ethnic subgroups in the U.S. 2008 Retrieved January 13, 2014, from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/nhsda/ethnic/toc.htm.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Treatment outcomes among clients discharged from residential substance abuse treatment: 2005. 2009 Retrieved August 2, 2013, from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k9/TXcompletion/TXcompletion.htm.

- Torrens M, Gilchrist G, Domingo-Salvany A. Psychiatric comorbidity in illicit drug users: Substance-induced versus independent disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;113(2–3):147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, Gratz KL. The impact of borderline personality disorder on residential substance abuse treatment dropout among men. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;121(1–2):97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB, Spitzer RL. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III—R (SCID): II. Multisite test-retest reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49(8):630–636. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080038006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]