Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate whether pointwise regression analysis of serial measures of retinal sensitivity can predict future visual field (VF) loss.

Methods

Medical records of 158 patients with glaucomatous eyes with at least 6 years follow-up and 10 reliable VF exams were retrospectively analyzed. The entire follow-up period was divided into two, roughly corresponding to the first (early period) and second (late period) half of follow-up. Retinal sensitivity data obtained from the Swedish interactive threshold algorithm standard or full-threshold VF tests were analyzed, and linear and first-order exponential regression analyses of retinal sensitivity against time were performed to obtain the slope of regression analysis in each VF test location. Paired t tests were used to compare the slopes of the early and late period in each regression analysis.

Results

When assessed by linear regression analysis, inferior nasal location showed highest rate of change (−0.52 dB/year) in early period. Late period showed generally faster rate of progression compared to early period. Superior arcuate and superior and inferior nasal locations showed that early and late slopes did not show significant difference (p value, 0.19 ~ 0.49). Central and edged locations showed significant difference between the two slopes (p value < 0.05). First-order exponential regression analysis showed similar result.

Discussion

Superior arcuate and superior and inferior nasal areas in VF had a consistent rate of change of retinal sensitivity, indicating that these locations may have the higher capability for prediction of future deterioration. These results suggest that location should be considered when predicting glaucomatous VF progression.

Keywords: Disease progression, glaucoma, GPA, prediction, visual field tests

INTRODUCTION

Glaucoma is defined as progressive loss of retinal ganglion cells and characteristic changes in neuroretinal rim tissue in the optic nerve head accompanied by visual field (VF) constriction. Detection of disease progression is crucial to ensure appropriate clinical management in order to preserve long-term vision.

Functional progression is usually measured by standard automated perimetry. Humphrey standard automated perimetry yields global indices including mean deviation (MD) and visual field index (VFI). MD indicates the difference between normative and measured threshold light sensitivity of the retina after accounting for patient age, but can be affected by functional changes that are caused by diseases other than glaucoma, primarily cataracts. VFI calculates age-corrected defect depth at test points identified as significantly depressed in pattern deviation probability maps.1,2 A linear regression of MD or VFI with respect to patient age is a common method for determining glaucoma progression and predicting future progression.3 This parameter replaced MD as the cornerstone of Humphrey’s guided progression analysis (GPA). However, since glaucomatous damage is predominantly localized, global indices might not be most efficient in detecting localized changes. As such, pointwise analysis of multiple VF test locations is more sensitive for the detection of functional progression.4–9

Predicting future VF change is a primary concern of a clinician in glaucoma patient care as it can indicate worsening of disease or response to treatment. To predict future change, one assumes that it will be similar to the change observed in the past.3,10 To test this assumption, we compared the rate of change of retinal sensitivity in the first half of the follow-up period with the rate of change in the second half of the follow-up period, and with the rate of change over the entire follow-up period in each VF test location. Hence, the purpose of this study was to evaluate if pointwise regression analysis of retinal sensitivity at multiple VF test locations can predict future VF loss. We intended to determine the consistency of the rate of change in retinal sensitivity at multiple locations, which information may improve future predictions of VF loss. We also aimed to determine the locations that have a consistent rate of progression across the course of the disease, and therefore might be most suitable for predicting future VF deterioration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Medical records of all glaucoma patients who were followed up with a Humphrey Field Analyzer (Carl Zeiss Meditec Inc., Dublin, CA) at the glaucoma clinic of the Department of Ophthalmology at the Asan Medical Center between January 1990 and August 2012 were retrospectively reviewed. All eyes with neuro-ophthalmic disorders, retinal diseases or history of intraocular surgery other than uncomplicated glaucoma surgery during follow-up period were excluded. Glaucomatous eyes with at least 6 years follow-up and 10 reliable VF exams, after eliminating first tests to minimize a learning effect, were enrolled. All participants had best-corrected visual acuity of 20/40 or better, with a spherical refractive error between −6.0 and +4.0 diopters (D) and a cylinder correction within +3D, and a normal anterior chamber and an open-angle on slit-lamp and gonioscopic examinations. Participants had to have glaucomatous optic disc changes (cup to disc ratio ≥0.7, diffuse or focal neural rim thinning, disc hemorrhage or retinal nerve fiber layer defects) and glaucomatous VF defect. A glaucomatous VF defect was defined as a cluster of three points with a probability <5% on the pattern deviation map in at least one hemifield, including at least one point with a probability of <1%, a cluster of two points with a probability of <1% and a glaucoma hemifield test result outside normal limits, or a pattern standard deviation (SD) outside 95% of normal limits. Only reliable VF test results (false-positive errors <15%, false-negative errors <15% and fixation loss <20%) were included in the analysis. We excluded those cases with baseline MD less than −20 dB. In cases where both eyes fulfilled the inclusion criteria, one eye was randomly selected for inclusion.

In each patient, we arbitrarily divided the follow-up period (entire period) into two time periods, roughly the first half (early period) and second half (late period). Early and late periods were 3–6 years each, depending on the total follow-up period duration, and included at least five VF tests each.

All procedures conform to the Declaration of Helsinki, and this study was approved by the institutional review board of the Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan, Seoul, Korea.

Statistical Analysis

Retinal sensitivity data from programs 24-2 and 30-2 of the Swedish interactive threshold algorithm (SITA) standard (SS) or full-threshold (FT) VF tests were analyzed by exportation of the raw data. Of total 158 patients, 70 patients were tested with FT exclusively, 84 patients initially started with FT but switched to SS during follow-up, and only 4 patients were tested with SS through entire follow-up period. It is known that FT and SS yields similar but small differences exists, SS yielding slightly higher sensitivity values ranging from 0.8 dB to 1.9 dB on an average with distributional differences.11–14 Budenz et al.15 found that glaucomatous VF defects appear approximately the same size in both tests, but is shallower in SS than FT, which, in part, can be explained by distributional differences described by Artes et al.11 As there is some evidence on the distributional pattern of differences, rather than correcting through addition of same value through entire sensitivity range,16 we segmented sensitivity to three categories and added different values derived from above-mentioned research to FT sensitivity values: (1) 0.6 dB to values of 25 dB and above; (2) 1.8 dB to values between 24 dB and 15 dB; and (3) 1.1 dB to values of 15 dB and below.

In the 30-2 program, the 54 points that correspond to the 24-2 program were extracted, and the two locations nearest the blind spot were excluded from analysis. In each of the 52 points, linear regression and first-order exponential regression analysis of retinal sensitivity and time were performed separately for each of the three periods in each subject. In previous papers, authors used exponential model defined as y = ea+bx, which is equivalent to ln (y) = a + bx,17,18 where y is retinal sensitivity (raw sensitivity in our case), and x is duration of follow-up (years in our case). However, our raw retinal sensitivity data include zeroes, which cannot be transformed with simple logarithmic transformation. Adding 1 to raw sensitivity values before transformation maps 0 to 0, so our model is y′ = ea+bx, which is equivalent to ln (y′) = a + bx, where y′ = y + 1.

Paired t tests were used to compare the slope of the relation between early period and late period, and between early period and the entire follow-up period. The former (early period versus late period) was intended to assess the consistency of the rate of progression over time, and the latter (early period versus entire follow-up period) to assess if the initial rate of progression was representative of the rate of progression across the course of the disease. Left and right eyes were analyzed together, and the results are presented as right eye in the figures. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Data were reported as either median and range or mean and SD after evaluation of normality (Shapiro–Wilk test). p Value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 158 eyes from 158 individuals were included in the analysis. Mean (±SD) patient age at baseline was 49.1 ± 14.0 years, ranging from 18 to 79 years. Patient demographics and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Baseline demographic characteristics of participants.

| Age (mean ± SD, years) | 49.1 ± 14.0 |

|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 95/63 |

| Eye (right/left) | 67/91 |

| Total follow-up duration (median, range, years) | 9.9 (6.7 ~ 11.7) |

| Follow-up duration of early period (median, range, years) | 4.7 (3 ~ 5.9) |

| Follow-up duration of late period (median, range, years) | 5.1 (3 ~ 5.9) |

| VF tests in the entire follow-up period (median, range, number) | 12 (10 ~ 25) |

| VF tests in early period (median, range, number) | 7 (6 ~ 14) |

| VF tests in late period(median, range, number) | 6 (5 ~ 15) |

| MD at baseline VF (median, range, dB) | −5.62 (−19.20 ~ −0.01) |

| PSD at baseline (median, range, dB) | 5.38 (1.04 ~ 15.86) |

Abbreviations: MD, mean deviation; VF, visual field; PSD, pattern standard deviation; SD, standard deviation.

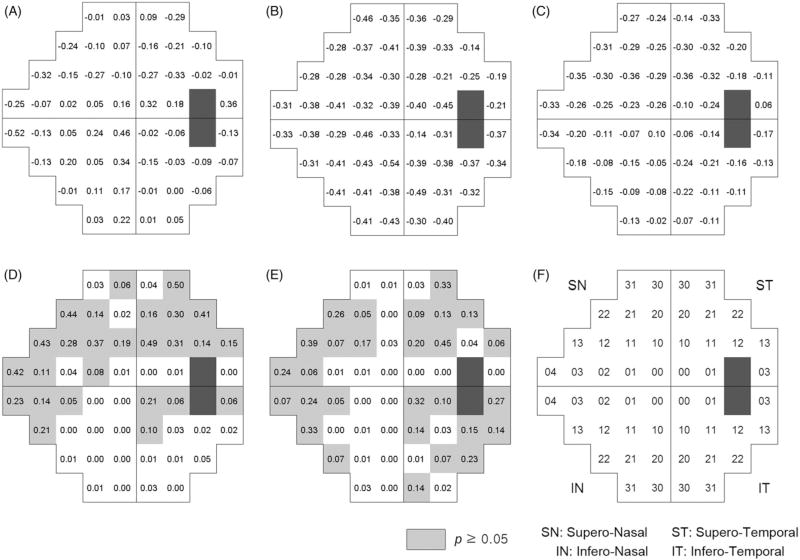

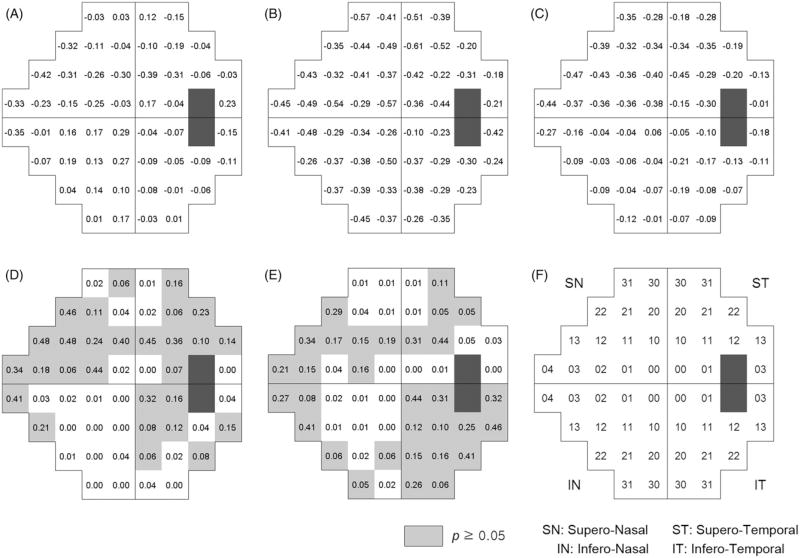

Six eyes had already received glaucoma surgery at the baseline, and 78 patients were receiving glaucoma medication, which has increased to 139 patients at the last follow-up. Intraocular pressure at last follow-up was significantly lower than that of baseline (Table 2). Average linear regression coefficients (dB/year, A, B and C) and p values of pairwise t test are presented in Figure 1 along with the comparison of the rate of change in early compare with either late (D) or entire follow-up (E). Location number is described in Figure 1(F). In early period, location 4 in inferior nasal VF showed highest rate of progression (−0.52 dB/year, Figure 1A). Location 13 and 4 in superior nasal VF (−0.32, and −0.25 dB/year, Figure 1A), superior locations 10 and 11 representing paracentral arcuate locations also showed relatively higher rate of progression (−0.10 ~ −0.33 dB/year, Figure 1A). Meanwhile, most of the infero-nasal locations and central locations showed relatively lower rate of progression. Late period generally showed faster rate of progression compared to early period (Figure 1B). No significant differences in early versus late slopes were detected in the superior arcuate and superior and inferior nasal locations (p value, 0.19–0.49, Figure 1D). For interpretability, locations that showed p value higher than 0.05 were marked as gray color (Figure 1D and E). In the mean time, central locations and edged locations showed that two slopes were significantly different. Comparative data of early rate of change with that of entire follow-up demonstrated slightly different pattern, but superior arcuate (except SN 10) and superior and inferior nasal locations showed consistent result (Figure 1E). Figure 2 demonstrated the result of first-order exponential regression analysis, which was similar to that of linear regression result. Superior arcuate and superior and inferior nasal locations showed that slopes were not significantly different. Therefore, the slope of the relation between time and retinal sensitivity in the superior arcuate and superior and inferior nasal areas was not significantly different across time periods when obtained by either linear or first-order exponential regression. By contrast, the slope of the locations in the superior and inferior edged areas and the central VF was significantly different between time periods, either between early period and late period, or between early period and the entire period.

TABLE 2.

Baseline and endpoint visual acuity, intraocular pressure and glaucoma medication (mean ± standard deviation).

| Baseline | Endpoint | p Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual acuity (LogMAR) | 0.08 ± 0.11 | 0.20 ± 0.26 | <0.01 |

| Intraocular pressure | 16.80 ± 3.16 | 14.06 ± 2.81 | <0.01 |

| Number of topical glaucoma medications | 0.61 ± 0.73 | 1.47 ± 0.93 | <0.01 |

Paired t test.

FIGURE 1.

Mean of linear regression coefficients (dB/year), for early period (A), late period (B) and entire period (C) in each VF test location. p Values after Bonferroni correction from paired t test of linear regression coefficients comparing early with late period (D), and early with entire period (E), location scheme (F).

FIGURE 2.

Mean of exponential regression coefficients (multiplied by 10 for better interpretability), for early period (A), late period (B) and entire period (C) in each VF test location. p Values after Bonferroni correction from paired t test of linear regression coefficients comparing early with late period (D), and early with entire period (E), location scheme (F).

DISCUSSION

Two types of analysis (event- and trend-based) are often used to detect glaucoma progression. Event-based method seeks to determine whether significant progression has occurred from the baseline status. Trend-based approach typically uses regression analysis to determine the rate of progression and can therefore be useful to predict future progression. By employing regression analyses, we intended to test rate of retinal sensitivity change in early period can predict that of late period in each VF test location. Our results showed characteristic spatial pattern of rate of change in early period, nasal and superior arcuate locations having clearly more negative regression coefficients. Furthermore, not all VF test locations had a consistent rate of change across the different time periods. In the central VF and edged locations (locations 0, 30 and 31), the slope was less consistent across time periods. However, in superior and inferior nasal locations and superior paracentral arcuate locations, the slope was generally consistent across time periods. Taken these findings together, we carefully make an assumption that nasal and superior arcuate locations deteriorate earlier than other locations, maintaining that pace over time. Such assumption suggests that these regions may have better predictability in future VF decay.

Inconsistency in retinal sensitivity trends over time in the central VF might be explained by the suggestion that 6° spatial resolution of VF grid in the 24-2 test pattern under-represents macular area and thus glaucomatous damage of the macular region might be missed and/or underestimated.19 Superior edged locations might have been affected by artifacts such as eyelids or lens frame, which contributed to the inconsistent measures in this location. Nasal steps and arcuate VF defects constitute the largest part of early glaucomatous change, and our results showed that these regions had a consistent rate of change of retinal sensitivity. In clinical situations, it is not always obvious whether observed retinal sensitivity decrease is caused by glaucomatous damage or other factors such as media opacity. Short- and long-term fluctuations and insufficient number of study series or follow-up period also contribute to difficulty in interpretation or prediction of VF change. Our findings show that there are spatial differences in the consistency of the rate of change in retinal sensitivity and therefore suggest that considering the spatial pattern may be useful in ambiguous situations. In addition, incorporating spatial characteristics into current trend- or event-based analyses may improve the specificity. For instance, significant deterioration from baseline in three or more of the same test locations (regardless where the locations are) in three consecutive examinations in GPA is usually regarded as a VF progression criteria20; however, if more weighting is attributed to locations where the rate of change is constant, the specificity of glaucoma progression detection may increase.

In this study, we used both linear regression and first-order exponential regression analyses. Commercially available progression detection programs such as Humphrey GPA or Progressor® employ linear regression analysis; however, some researchers advocate exponential regression analyses, thus we included both.17 At some locations, there were slight differences in the consistency of the two analyses, but locations with high consistency were similar with both analyses.

Our study has some limitations. We included data obtained by both FT and SITA strategies so that we could incorporate a longer follow-up period. Although the two strategies use different algorithms, previous studies have demonstrated that both strategies yield comparable results.11–16,21,22 However, use of two different algorithms might affect the outcome. We excluded patients who underwent cataract surgery during follow-up time; however, it is still possible that the retinal sensitivity of older patients may have been affected by incipient cataractous change. There was a significant change in progression at the edge locations in VF, which may be explained that edged position was still affected by lens artifact although the regression analysis of multiple exams could reduce the bias in some degree.

In conclusion, when we performed a pointwise regression analysis of retinal sensitivity at multiple VF locations, the superior arcuate and the superior and inferior nasal areas showed a consistent rate of change of retinal sensitivity over time, indicating that these locations have the highest capability for accurate prediction of future deterioration. Our results also suggest that test location should be considered when predicting glaucomatous VF progression.

Acknowledgments

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

Dr. Wollstein is a consultant to Allergan. Dr. Schuman receives royalties for intellectual property licensed by Massachusetts Institute of Technology to Carl Zeiss Meditec.

References

- 1.Bengtsson B, Heijl A. A visual field index for calculation of glaucoma rate of progression. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145:343–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cho JW, Sung KR, Yun SC, Na JH, Lee Y, Kook MS. Progression detection in different stages of glaucoma: mean deviation versus visual field index. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2012;56:128–133. doi: 10.1007/s10384-011-0110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bengtsson B, Patella VM, Heijl A. Prediction of glaucomatous visual field loss by extrapolation of linear trends. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:1610–1615. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Viswanathan AC, Crabb DP, McNaught AI, Westcott MC, Kamal D, Garway-Heath DF, et al. Interobserver agreement on visual field progression in glaucoma: a comparison of methods. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:726–730. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.6.726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilkins MR, Fitzke FW, Khaw PT. Pointwise linear progression criteria and the detection of visual field change in a glaucoma trial. Eye (Lond) 2006;20:98–106. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strouthidis NG, Scott A, Viswanathan AC, Crabb DP, Garway-Heath DF. Monitoring glaucomatous visual field progression: the effect of a novel spatial filter. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:251–257. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nouri-Mahdavi K, Mock D, Hosseini H, Bitrian E, Yu F, Afifi A, et al. Pointwise rates of visual field progression cluster according to retinal nerve fiber layer bundles. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:2390–2394. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manassakorn A, Nouri-Mahdavi K, Koucheki B, Law SK, Caprioli J. Pointwise linear regression analysis for detection of visual field progression with absolute versus corrected threshold sensitivities. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2896–2903. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Moraes CG, Liebmann CA, Susanna R, Jr, Ritch R, Liebmann JM. Examination of the performance of different pointwise linear regression progression criteria to detect glaucomatous visual field change. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2012;40:e190–e196. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2011.02680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asaoka R, Russell RA, Malik R, Garway-Heath DF, Crabb DP. Five-year forecasts of the Visual Field Index (VFI) with binocular and monocular visual fields. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251:1335–1341. doi: 10.1007/s00417-012-2214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Artes PH, Iwase A, Ohno Y, Kitazawa Y, Chauhan BC. Properties of perimetric threshold estimates from Full Threshold, SITA Standard, and SITA Fast strategies. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:2654–2659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bengtsson B, Heijl A, Olsson J. Evaluation of a new threshold visual field strategy, SITA, in normal subjects. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1998;76:165–169. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1998.760208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shirato S, Inoue R, Fukushima K, Suzuki Y. Clinical evaluation of SITA: a new family of perimetric testing strategies. Graef Arch Clin Exp. 1999;237:29–34. doi: 10.1007/s004170050190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wild JM, Pacey IE, Hancock SA, Cunliffe IA. Between-algorithm, between-individual differences in normal perimetric sensitivity: full threshold, FASTPAC, and SITA. Swedish Interactive Threshold algorithm. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:1152–1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Budenz DL, Rhee P, Feuer WJ, McSoley J, Johnson CA, Anderson DR. Comparison of glaucomatous visual field defects using standard full threshold and Swedish interactive threshold algorithms. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:1136–1141. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.9.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Moraes CG, Demirel S, Gardiner SK, Liebmann JM, Cioffi GA, Ritch R, et al. Effect of treatment on the rate of visual field change in the ocular hypertension treatment study observation group. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:1704–1709. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azarbod P, Mock D, Bitrian E, Afifi AA, Yu F, Nouri-Mahdavi K, et al. Validation of point-wise exponential regression to measure the decay rates of glaucomatous visual fields. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:5403–5409. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caprioli J, Mock D, Bitrian E, Afifi AA, Yu F, Nouri-Mahdavi K, et al. A method to measure and predict rates of regional visual field decay in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:4765–4773. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hood DC, Raza AS, de Moraes CG, Liebmann JM, Ritch R. Glaucomatous damage of the macula. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2013;32:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heijl A, Leske MC, Bengtsson B, Bengtsson B, Hussein M, Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial Group Measuring visual field progression in the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2003;81:286–293. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2003.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Musch DC, Gillespie BW, Motyka BM, Niziol LM, Mills RP, Lichter PR. Converting to SITA-standard from full-threshold visual field testing in the follow-up phase of a clinical trial. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2755–2759. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schimiti RB, Avelino RR, Kara-José N, Costa VP. Full-threshold versus Swedish Interactive Threshold Algorithm (SITA) in normal individuals undergoing automated perimetry for the first time. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:2084–2092. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]