Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to identify optimal blood pressure cut-offs to diagnose orthostatic hypotension (OH) during a sit-to-stand manoeuvre.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study of patients and healthy controls from the Vanderbilt Autonomic Dysfunction Center. Blood pressure was measured while supine, seated, and standing. Blood pressure changes were calculated from 1) supine-to-standing and 2) seated-to-standing. OH was diagnosed based on a supine-to-standing systolic blood pressure (SBP) drop ≥20 mmHg or a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) drop ≥10 mmHg. Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves identified optimal sit-to-stand cut-offs.

Results

Amongst the 831 subjects, more had systolic OH (n=354[43%]) than diastolic OH (n=305[37%]) during lying-to-standing. The ROC curves had good characteristics (SBP area under curve = 0.916[95% confidence interval: 0.896, 0.936], p<0.001; DBP area under curve = 0.930[95% confidence interval: 0.909, 0.950], p <0.001). A sit-to stand SBP drop ≥15 mmHg had optimal test characteristics (sensitivity= 80.2%; specificity= 88.9%; positive predictive value= 84.2%; negative predictive value= 85.8%), as did a DBP drop ≥7 mmHg (sensitivity= 87.2%; specificity= 87.2%; positive predictive value= 80.1%; negative predictive value= 92.0%).

Conclusions

A sit-to-stand manoeuvre with lower diagnostic cut-offs for OH provides a simple screening test for OH in situations where a supine-to-standing maneuver cannot be easily performed. Our analysis suggests that a SBP drop ≥15 mmHg or a DBP drop ≥7 mmHg best optimizes sensitivity and specificity of this sit-to-stand test.

Keywords: orthostatic hypotension, orthostatic intolerance, blood pressure, syncope, falls, autonomic diseases

INTRODUCTION

Orthostatic hypotension (OH) is defined as a sustained reduction of at least 20 mmHg systolic blood pressure (SBP) or 10 mmHg diastolic blood pressure (DBP) within 3 minutes of standing or head-up tilt (HUT) from a supine position [1]. The presence of OH has significant consequences that are still being understood; overall, it is associated with an increased risk of morbidity and mortality [2–5]. OH can be caused by acute conditions including hypovolemia, valvular heart disease, and acute illness, as well as a host of chronic disorders including diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, and multiple system atrophy [6]. The ability to identify OH is useful in many clinical areas including the emergency department, outpatient cardiology or neurology clinics, or inpatient units. Unfortunately, orthostatic blood pressure (BP) testing may be underutilized in day-to-day clinical practice due to the nature of testing maneuvers.

A sit-to-stand test is a logistically simpler test that doesn’t require a bed, allowing it to be easily performed in a clinic or an emergency department. A limitation of the sit-to-stand manoeuvre is that the orthostatic BP drops that are elicited are smaller due to the reduced acute change in gravitational stress in comparison to that of the supine-to-standing or HUT testing [7]. Therefore, the consensus definition thresholds for OH may under-diagnose OH when a sit-to-stand test is used. To our knowledge, no studies have identified the ideal BP cut-point that may best detect OH when a sit-to-stand manoeuvre is used.

Here, we studied patients and healthy volunteers with a wide range of change in orthostatic blood pressure, in whom we obtained supine, seated, and upright blood pressures. We used the standard diagnostic criteria of OH based on supine-to-stand BP as the gold standard to identify the optimal cut-point for BP drops during sit-to-stand orthostatic blood pressure testing that could be used to identify patients with OH.

METHODS

Both the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board and the Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board approved this cross-sectional study.

Participants

Subject data was obtained retrospectively from a database of patients and healthy subjects who presented to the Vanderbilt University Autonomic Dysfunction Centre. Subjects presented to the Vanderbilt Autonomic Dysfunction Centre for investigation and management of suspected autonomic nervous system pathology, or for participation in research studies. All participating subjects who signed written informed consent prior to testing were eligible for inclusion in this study. Subjects were excluded if they did not have a complete set of orthostatic BP measurements in each position, if they completed a protocol that required standing BP measurements greater than 5 minutes in duration and did not record a 5 minute value, or if key demographic characteristics were missing.

Protocols

Testing was performed on one occasion, either in the Vanderbilt Clinical Research Centre or in the Autonomic Clinic. Clinic participants were tested on the day of their clinic visit (usually in the morning). Subjects at the Clinical Research Center were tested around 8:00am after their first night sleeping at the Clinical Research Center. For the Clinical Research Centre subjects, medications that could alter autonomic tone or blood volume regulation were held for five half-lives prior to testing. At the clinic, medications were held on the day of testing. Blood pressure measurements were made by a nurse or trained cardiovascular technician. Participants underwent BP recordings by automated oscillometric sphygmomanometer attached to a patient care monitor, with a manual cuff as a backup. Recordings were made sequentially, first after the subject had been supine for at least 5 minutes, then while seated, and then while standing at 1 minute, 3 minutes, 5 minutes, and 10 minutes (as tolerated).

Data analysis

The drops in SBP and DBP were calculated from supine-to-standing and from sitting-to-standing. The “gold-standard” diagnosis of OH was made based on a supine-to-standing SBP drop ≥20 mmHg or DBP drop ≥10 mmHg[1]. We performed two analyses comparing patients with SBP OH or DBP OH to those without OH. We also performed two separate sensitivity analyses. In one analysis, we focused on only patients with severe drops in BP (defined as a SBP drop ≥40 mmHg or DBP drop ≥20 mmHg). In the second analysis, we focused only on the patients with less severe drops in BP (defined as a SBP drop <40 mmHg or DBP drop <20 mmHg). were isolated and compared to the rest of the patient cohort.

Statistical analysis

We used receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves to find the optimal diagnostic cut-point for the sit-to-stand test to best identify patients diagnosed with OH per the supine-to-standing test. We calculated test performance (sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value, and positive and negative likelihood ratios) at the various blood pressure cut-points. The Youden Index (J) was calculated to identify the blood pressure cut-point that optimized sensitivity and specificity [8]. This index is calculated as the sum of sensitivity and specificity minus one; the higher this value, the closer to optimal the sensitivity and specificity for a given cut-point. Unless reported otherwise, all values were reported as mean (standard error of the mean) or number (%). Differences in continuous variables between patients with and without OH were assessed using Student’s t-test for parametric data or Mann-Whitney U test for non-parametric data. The Chi-Square test was used for categorical variables. The level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05. Analyses were performed using SPSS Version 22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA). Figures were produced using Adobe Illustrator CC (Adobe Systems Incorporated, San Jose, California, USA).

RESULTS

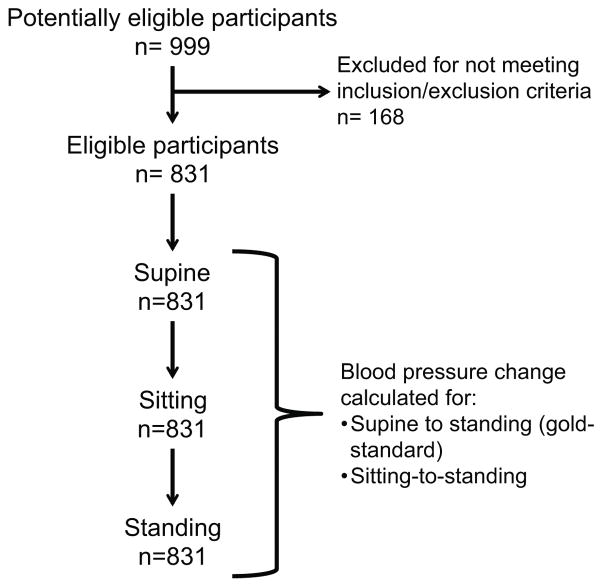

Suitable SBP recordings were available in 831 participants, while DBP recordings were available in 822 participants (Figure 1). These subjects were over 90% Caucasian and over 60% from Tennessee and neighboring states. They had been evaluated between March 1983 and January 2016. The most common diagnoses included vasovagal syncope (85), postural tachycardia syndrome (200), orthostatic intolerance (54) multiple system atrophy (97), pure autonomic failure (88), Parkinson’s disease (54), hypertension (24), autonomic neuropathy (24), baroreflex failure (23), and a group with a history of nonspecific orthostatic hypotension (104). Healthy control subjects (47) and a small number of patients with various neurological or cardiac disorders made up the rest of the study cohort.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for participant selection and testing.

A total of 381 (46%) subjects met either SBP or DBP criteria for OH during the supine-to-standing test. Specifically, 354 (43%) patients had SBP OH; 305 (37%) had DBP OH; and 277 (34%) of these subjects met both criteria during testing. By comparison, during sit-to-stand testing, 347 (42%) subjects met either SBP or DBP OH criteria. 284 (34%) patients had SBP OH; 277 (33%) had DBP OH; and 214 (26%) of these subjects met both criteria during testing.

Systolic blood pressure analysis

Table 1 illustrates subject characteristics comparing those who met the supine-to-standing SBP OH to those who did not. Overall, a large proportion of subjects had underlying autonomic or neurological conditions. There were very few subjects with non-neurogenic forms of OH in this cohort. There were significantly more subjects that met criteria for SBP OH during the supine-to-standing test than during the sit-to-stand test when using the conventional 20 mmHg drop in each test (43% vs. 34%; p<0.001; Table 2). In those with SBP OH, the mean decline in SBP during the supine-to-standing test was 58.7 ± 1.5 mmHg, which was significantly larger than the decline during sit-to-stand testing (34.0 ± 0.9 mmHg; p<0.001). In those without SBP OH, SBP increased during supine-to-standing testing on average by 3.6 ± 0.6 mmHg; this was significantly different from sit-to-stand testing (p<0.001), which produced a small decline of 0.6 ± 0.6 mmHg on average.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics in those with and without orthostatic hypotension.

| Characteristic | SBP criteria | DBP criteria | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| OH | No OH | OH | No OH | |

|

| ||||

| n = 354 | n = 477 | n = 305 | n = 517 | |

|

| ||||

| Mean (SD) or n (% total) | ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 63 (16) | 39 (49) | 59 (60) | 43 (18) |

| Female gender | 160 (19) | 361 (43) | 130 (16) | 384 (47) |

| Patient diagnoses | ||||

| Healthy subjects | 2 (0) | 45 (5) | 2 (0) | 45 (5) |

| Hypertension | 3 (0) | 21 (2) | 1 (0) | 23 (3) |

| Vasovagal syncope | 17 (2) | 68 (8) | 11 (1) | 74 (9) |

| Postural tachycardia syndrome | 0 (0) | 192 (23) | 0 (0) | 191 (23) |

| Orthostatic intolerance | 20 (2) | 43 (5) | 23 (3) | 40 (4) |

| Multiple system atrophy | 87 (10) | 10 (1) | 77 (9) | 17 (2) |

| Pure autonomic failure | 81 (10) | 7 (1) | 71 (9) | 17 (2) |

| Parkinson’s disease | 43 (5) | 11 (1) | 37 (5) | 17 (2) |

| Hyperadrenergic OH | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Nonspecific OH | 62 (7) | 41 (5) | 51 (6) | 47 (5) |

| Autonomic neuropathy | 18 (2) | 6 (1) | 15 (2) | 9 (1) |

| Baroreflex failure | 8 (1) | 15 (2) | 5 (1) | 18 (2) |

| Dopamine beta hydroxylase deficiency | 8 (1) | 0 (0) | 8 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Mast cell activation disorder | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0) |

| Progressive supranuclear palsy | 2 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 2 (0) |

| Progressive cerebellar dysfunction | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Autoimmune autonomic failure | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Sjogren’s sydrome | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Inappropriate sinus tachycardia | 0 (0) | 2 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0) |

| Palpitations | 0 (0) | 2 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0) |

| Multiple sclerosis | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Postprandial hypotension | 0 (0) | 3 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (0) |

| Pseudopheochromocytoma | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Deconditioning | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) |

Abbreviations: SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; OH, orthostatic hypotension; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

Patients diagnosed with systolic and/or diastolic orthostatic hypotension by supine-to-standing (2A) and sit-to-stand testing (2B).

| A. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Test | Criteria | OH | No OH |

|

| |||

| n (%) | |||

| Supine-to-standing | Systolic | 354 (43) | 477 (57) |

| Diastolic | 305 (37) | 517 (63) | |

| B. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Test | Criteria | OH | No OH |

|

| |||

| n (%) | |||

| Sit-to-stand | Systolic | 284 (34) | 547 (66) |

| Diastolic | 277 (33) | 545 (66) | |

Abbreviations: OH, orthostatic hypotension.

The mean rise in heart rate during supine-to-standing test was 15.4 ± 0.7 beats per minute (BPM) in those with SBP OH; this was significantly larger than the heart rate rise experienced during sit-to-stand (8.6 ± 0.6 BPM; p<0.001). In contrast, in those without SBP OH the mean rise in heart rate during supine-to-standing test was 26.7 ± 0.9 BPM; this was again significantly larger than the heart rate rise experienced during sit-to-stand (18.6 ± 0.7 BPM; p<0.001)

Diastolic blood pressure analysis

Patient characteristics in subjects with and without DBP OH are also shown in Table 1. There were also significantly more subjects that met criteria for DBP OH during the supine-to-standing test than during the sit-to-stand test using a 10 mmHg drop in each test (37% vs. 33%; p=0.005; Table 2). In those with DBP OH, the mean decline in DBP during the supine-to-standing test was 28.4 ± 0.8 mmHg, which was significantly larger than the decline during sit-to-stand testing (18.5 ± 0.7 mmHg; p<0.001). In those without DBP OH, the DBP increased during supine-to-standing testing on average by 6.0 ± 0.4 mmHg; this was significantly different from sit-to-stand testing (p<0.001), which increased by 2.3 ± 0.4 mmHg on average.

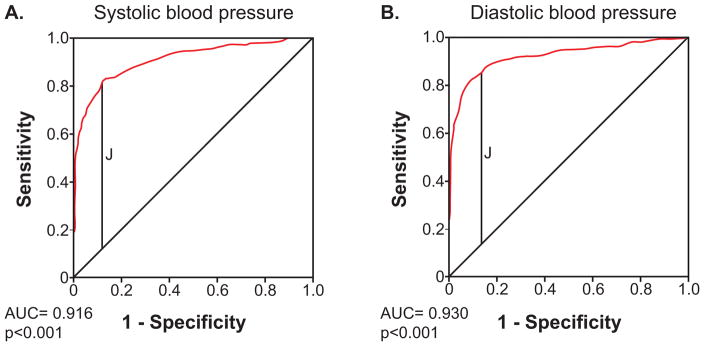

ROC curve analysis

Figure 2 presents the results of ROC curve analyses illustrating the diagnostic characteristics for the sit-to-stand test across all hypothetical cut-offs for SBP and DBP drops. Both curves had strong characteristics (SBP area under the curve = 0.916 [95% confidence interval: 0.896, 0.936], p<0.001; DBP area under the curve = 0.930 [95% confidence interval: 0.909, 0.950], p <0.001).

Figure 2.

Receiver operator characteristic curves for the detection of orthostatic hypotension during sit-to-stand testing.

Legend. Receiver operator characteristic curves for the detection of orthostatic hypotension during sit-to-stand testing using systolic blood pressure criteria (A) and diastolic blood pressure criteria (B). The red line is the plot of the true positive rate (sensitivity) against the false positive rate (1-specificity). The diagonal line represents the line of no-discrimination. The vertical black line represents where the Youden Index (J) is maximized; it is highest for a SBP drop cut-point of 15 mmHg (J= 0.691), and a DBP drop cut-point of 7 mmHg (J=0.744).

Table 3 illustrates test characteristics for the sit-to-stand manoeuvre at the conventional cut-points for OH (20 mmHg SBP drop, 10 mmHg DBP drop), as well as smaller cut-points around these values. At the conventional SBP OH cut-point of a 20 mmHg drop, we found a sensitivity of 72.3%, specificity of 94.1%, positive predictive value of 90.1%, and a negative predictive value of 82.1% for sit-to-stand. For a DBP drop of 10 mmHg, we found a sensitivity of 80.3%, specificity of 93.8%, positive predictive value of 88.4%, and a negative predictive value of 89.0% for sit-to-stand. The Youden Index (J) was highest for a SBP drop cut-point of 15 mmHg (J= 0.691), and a DBP drop cut-point of 7 mmHg (J=0.744).

Table 3.

Diagnostic characteristics for the sit-to-stand test across different cut-points for orthostatic hypotension.

| A. Systolic Blood Pressure | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| SBP drop cutoff | Sens (%) | Spec (%) | LR+ | LR− | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Youden statistic |

| 20 | 72.3 | 94.1 | 12.3 | 0.29 | 90.1 | 82.1 | 0.664 |

| 15 | 80.2 | 88.9 | 7.2 | 0.22 | 84.2 | 85.8 | 0.691 |

| 10 | 87.6 | 79.7 | 4.3 | 0.16 | 76.2 | 89.6 | 0.672 |

| 5 | 92.4 | 64.6 | 2.6 | 0.12 | 65.9 | 91.9 | 0.569 |

| 0 | 95.5 | 43.8 | 1.7 | 0.10 | 55.8 | 92.9 | 0.392 |

| B. Diastolic Blood Pressure | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| DBP drop cutoff | Sens (%) | Spec (%) | LR+ | LR− | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Youden statistic |

| 10 | 80.3 | 93.8 | 13.0 | 0.21 | 88.4 | 89.0 | 0.741 |

| 7 | 87.2 | 87.2 | 6.8 | 0.15 | 80.1 | 92.0 | 0.744 |

| 5 | 81.5 | 80.7 | 4.7 | 0.11 | 73.6 | 94.1 | 0.721 |

| 3 | 93.1 | 73.0 | 3.4 | 0.09 | 67.0 | 94.7 | 0.660 |

| 0 | 94.4 | 57.1 | 2.2 | 0.10 | 54.4 | 94.7 | 0.515 |

Abbreviations: SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; Sens, sensitivity; Spec, specificity; LR+, positive likelihood ratio; LR− negative likelihood ratio; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value.

Sensitivity analysis

Two sensitivity analyses were performed. The first analysis included only patients with severe drops in SBP (≥40 mmHg) or DBP (≥20 mmHg). This cohort comprised 268 (32%) patients with OH.

In the subset of patients with severe drops in SBP or DBP, ROC curves for SBP and DBP were highly significant (SBP AUC = 0.881 [95% confidence interval: 0.779, 0.983], p<0.001; DBP AUC = 0.920 [95% confidence interval: 0.884, 0.956], p<0.001). The Youden index was optimized for a SBP cut-off of 20 mmHg and a DBP cut-off of 10 mmHg in this group. At an SBP cut-off of 20 mmHg, the sensitivity and specificity were 82.2% and 80.0%, respectively. At a DBP cut-off of 10 mmHg, the sensitivity was 84.8% and the specificity was 94.4%.

A second sensitivity analysis was performed in patient cohort with less severe BP drops (a SBP drop of <40 mmHg or DBP drop <20 mmHg). This cohort comprised 563 (32%) patients with OH. ROC curves for SBP and DBP remained significant in this subgroup, although the sit-to stand test was less robust (SBP AUC = 0.846 [95% confidence interval: 0.801, 0.891], p<0.001; DBP AUC = 0.888 [95% confidence interval: 0.841, 0.934], p<0.001). The Youden index was optimized for a SBP cut-off of 10 mmHg and a DBP cut-off of 5 mmHg in this group. At an SBP cut-off of 10 mmHg, the sensitivity and specificity were 77.1% and 80.1%, respectively. At a DBP cut-off of 5 mmHg, the sensitivity was 83.6% and the specificity was 81.8%.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that the sit-to-stand test appears to be a good alternative test to diagnose OH, if lower BP drop thresholds are used. To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify an optimal cut-point for diagnosing OH using a sit-to-stand procedure. The use of these novel criteria may make the assessment and diagnosis of OH more accessible in varied clinical settings.

Diagnostic test characteristics

Other studies have shown that the sit-to-stand manoeuvre elicits a smaller blood pressure drop in comparison to HUT and supine-to-standing [9]. Cooke et al. reported that the sit-to-stand test has a sensitivity of 15.5%, a positive predictive value of 61.7%, and a negative predictive value of 50.2% using conventional cut-offs for OH of ≥20mmHg SBP or ≥10mmHg DBP with HUT used as the reference standard [9]. These values are all much lower than the test characteristics we found in our group at the conventional SBP and DBP OH cut-points (Table 3). Their study used a cohort of older adults being assessed for recurrent falls or orthostatic intolerance. In contrast, a large proportion of our patients had existing autonomic disorders, which may partially explain these differences.

Utility of sit-to-stand testing

We found that a threshold of 15 mmHg for SBP and 7 mmHg for DBP produced the optimal test characteristics as assessed with the Youden Statistic. However, the optimal cut-off to use for the sit-to-stand manoeuvre depends on the clinician’s goal and may vary depending on how sick the population of interest is. If the sit-to-stand test is meant to serve as a sensitive screening test for OH, then using a smaller required drop in BP as a cut-off criterion will have improved sensitivity and negative predictive value, yielding fewer false negative results. The tradeoff is a high false positive rate, with poorer specificity and poorer positive predictive value. In this context, sit-to-stand testing can be useful for borderline cases in helping determine the need for further testing by head-up-tilt with beat-to-beat monitoring.

The ability to effectively assess OH using a simple sit-to-stand manoeuvre serves an important practical purpose in the clinical environment. Dizziness, fainting, and falls are common complaints presented to both specialists and general practitioners. The prevalence of OH is estimated to range between 4–35%, and increases with age [10–12]. Patients may present with complaints potentially related to OH in the outpatient clinic, the emergency department, or even inpatient wards. In a cohort of patients evaluated in the emergency department, a finding of OH increased the likelihood that patients were admitted to inpatient units [13]. Given that over 50% of cases of OH are caused by acute events such as hemorrhage or dehydration [10], patients with OH may often represent a more seriously ill subset. This represents a key piece of clinical information for an emergency physician trying to decide whether to discharge or admit a patient. Additionally, given that the prevalence of OH is higher in older adults, many of whom have comorbidities that may impact mobility, a sit-to-stand manoeuvre offers a safer method to transfer a patient into an upright position without triggering an acute fall or syncopal event [14].

Given the high prevalence of OH, simple bedside screening for OH has often been advocated [11]. Simple screening is particularly important in a clinical environment with a high prevalence of OH-causing disorders, such as within a movement disorder or cardiology clinic. In this environment, it is important to measure orthostatic vital signs. However, this is frequently not done due to logistical difficulties, with the potential to miss diagnoses. In fact, in older adults being investigated for a syncopal episode in hospital, orthostatic BP testing was found to have the highest yield for impacting diagnosis and management of these patients amongst other investigations, yet was only performed 38% of the time [15]. In contrast to many other diagnostic tests, the cost of orthostatic BP testing is minimal. Most importantly, this is a missed opportunity to improve quality of life in these individuals, as appropriate treatment is available. The sit-to-stand testing would help alleviate this problem by making it possible to do testing while a patient is sitting on a chair in the examination room.

There are several limitations to the present study. As this was a retrospective design, we were unable to have patients undergo each test separately and randomize the order in which testing was conducted. Ideally, subjects would have been randomized in a crossover fashion to do either the sit-to-stand test or the supine-to-standing test first. Future studies should address this in order to better validate these findings. Additionally, we did not record any symptoms that were experienced during testing, thus we do not know if patients experienced symptomatic OH at different rates depending on the test. Finally, all pressure changes were recorded using an automated or manual sphygmomanometer. As such, we were not able to detect transient drops in blood pressure meeting criteria for other types of OH, such as initial OH, that are only detected when using beat-to-beat blood pressure monitoring. It is also important to recognize the generalizability of these results. A large proportion of our study population was made up of patients with chronic autonomic and neurological disorders. Many of these patients with OH likely had a neurogenic cause. Therefore, these results may not be generalizable to populations of patients presenting with non-neurogenic forms of OH, such as patients in the emergency department. As such, while we have developed optimal blood pressure cut-points for the sit-to-stand test in a fairly large cohort, this still requires validation in separate cohorts.

Head-up tilt or a supine-to-standing testing is recommended to diagnose orthostatic hypotension. This is still the “gold standard test”. Unfortunately, these tests can sometimes be impractical and cumbersome to perform in day-to-day clinical practice leading to the lack of necessary clinical assessments. The sit-to-stand manoeuvre is a simpler test, but induces a smaller orthostatic stress, making conventional blood pressure cut-offs to diagnose OH challenging to reach. Here, we have demonstrated in a large sample of patients with underlying neurologic or autonomic disorders that the sit-to-stand manoeuvre, when used with smaller diagnostic cut-offs for OH, provides a simple screening test for OH. This testing does not require the use of a hospital bed or tilt-table and could serve as an alternative in situations where one of the gold-standard tests cannot be easily performed. This could be useful in multiple settings, including clinics, inpatient units or in the emergency department, where testing could quickly be done while in the waiting room of a clinic or upon patient arrival at triage. By making the diagnostic criteria for OH easier to assess, there is an opportunity to improve care for these patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers P01 HL056693-19 and R01 HL102387 and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Clinical and Translational Science Award UL1 TR000445. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Presented at: 27th International Symposium on the Autonomic Nervous System from November 2-5, 2016 in San Diego, CA, USA.

References

- 1.Freeman R, Wieling W, Axelrod FB, Benditt DG, Benarroch E, Biaggioni I, et al. Consensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, neurally mediated syncope and the postural tachycardia syndrome. Clin Auton Res. 2011;21(2):69–72. doi: 10.1007/s10286-011-0119-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angelousi A, Girerd N, Benetos A, Frimat L, Gautier S, Weryha G, et al. Association between orthostatic hypotension and cardiovascular risk, cerebrovascular risk, cognitive decline and falls as well as overall mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2014;32(8):1562–1571. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000235. discussion 1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ricci F, Fedorowski A, Radico F, Romanello M, Tatasciore A, Di Nicola M, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality related to orthostatic hypotension: a meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(25):1609–1617. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veronese N, De Rui M, Bolzetta F, Zambon S, Corti MC, Baggio G, et al. Orthostatic Changes in Blood Pressure and Mortality in the Elderly: The Pro.V. A Study. American Journal of Hypertension. 2015;28(10):1248–1256. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpv022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freud T, Punchik B, Press Y. Orthostatic Hypotension and Mortality in Elderly Frail Patients. Medicine. 2015;94(24):e977. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldstein DS, Sharabi Y. Neurogenic orthostatic hypotension: a pathophysiological approach. Circulation. 2009;119(1):139–146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.805887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlson JE. Assessment of orthostatic blood pressure: measurement technique and clinical applications. South Med J. 1999;92(2):167–173. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199902000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer. 1950;3(1):32–35. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::aid-cncr2820030106>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooke J, Carew S, O’Connor M, Costelloe A, Sheehy T, Lyons D. Sitting and standing blood pressure measurements are not accurate for the diagnosis of orthostatic hypotension. QJM. 2009;102(5):335–339. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcp020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feldstein C, Weder AB. Orthostatic hypotension: a common, serious and underrecognized problem in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2012;6(1):27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ricci F, De Caterina R, Fedorowski A. Orthostatic Hypotension: Epidemiology, Prognosis, and Treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(7):848–860. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.06.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Low PA. Prevalence of orthostatic hypotension. Clin Auton Res. 2008;18(Suppl 1):8–13. doi: 10.1007/s10286-007-1001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen E, Grossman E, Sapoznikov B, Sulkes J, Kagan I, Garty M. Assessment of orthostatic hypotension in the emergency room. Blood Press. 2006;15(5):263–267. doi: 10.1080/08037050600912070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Committee ENAENRD. Naccarato M, Leviner S, Proehl J, Barnason S, Brim C, et al. Emergency Nursing Resource: orthostatic vital signs. Journal of emergency nursing: JEN : official publication of the Emergency Department Nurses Association. 2012;38(5):447–453. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mendu ML, McAvay G, Lampert R, Stoehr J, Tinetti ME. Yield of diagnostic tests in evaluating syncopal episodes in older patients. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(14):1299–1305. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.