Abstract

One of the most important advances in biology has been the discovery that siRNA (small interfering RNA) is able to regulate the expression of genes, by a phenomenon known as RNAi (RNA interference). The discovery of RNAi, first in plants and Caenorhabditis elegans and later in mammalian cells, led to the emergence of a transformative view in biomedical research. siRNA has gained attention as a potential therapeutic reagent due to its ability to inhibit specific genes in many genetic diseases. siRNAs can be used as tools to study single gene function both in vivo and in-vitro and are an attractive new class of therapeutics, especially against undruggable targets for the treatment of cancer and other diseases. The siRNA delivery systems are categorized as non-viral and viral delivery systems. The non-viral delivery system includes polymers; Lipids; peptides etc. are the widely studied delivery systems for siRNA. Effective pharmacological use of siRNA requires ‘carriers’ that can deliver the siRNA to its intended site of action. The carriers assemble the siRNA into supramolecular complexes that display functional properties during the delivery process.

Keywords: siRNA, Delivering siRNA, RNAi, Gene silencing, siRNA therapeutics

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, few areas of biology have been transformed as thoroughly as RNA molecular biology. This transformation has occurred along many fronts, as detailed in this issue, but one of the most significant advances has been the discovery of small (20–30 nucleotide [nt]) noncoding RNAs that regulate genes and genomes. This regulation can occur at some of the most important levels of genome function, including RNA processing, chromatin structure, RNA stability, chromosome segregation, transcription, and translation (1-3).

Despite many classes of small RNAs have emerged, biological roles, associated effector proteins, various aspects of their origins, and structures have led to the general recognition of three main categories: piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), short interfering RNAs (siRNAs), and microRNAs (miRNAs) (4-7).

RNA interference (RNAi), the biological mechanism by which double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) induces gene silencing by targeting complementary mRNA for degradation, is a tremendous innovation in the universal therapeutic treatment of disease and revolutionizing the way researchers study gene function. RNAi, first discovered in plants, was later demonstrated in the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans, an organism in which gene expression is downregulated by long dsRNA (8, 9).

Increasing knowledge on the molecular mechanisms of endogenous RNA interference, siRNAs have been emerging as innovative nucleic acid medicines fo the treatment of incurable diseases such as cancers (10-14). Because systemic administration will be required in most cases, there are challenges inherent in the further development of siRNAs for anti-cancer therapeutics, Although several siRNA candidates for the treatment of respiratory and ocular diseases are undergoing clinical trials (15-17).

In an attempt to develop siRNA for use in clinical trials as drugs, various chemical modifications are being investigated to improve qualities such as low immunostimulation, target organ/cell delivery, off-target effects, siRNA potency, and serum stability [18].

Despite the high therapeutic potential of siRNA, its application in clinical settings is still limited mainly due to the lack of efficient delivery systems [19-23].

The discovery of RNAi has opened doors that might introduce a novel therapeutic tool to the clinical setting [24-32]. RNAi is charged with controlling vital processes such as cell growth, tissue differentiation, heterochromatin formation, and cell proliferation. Accordingly, RNAi dysfunction is linked to cardiovascular disease, neurological disorders, and many types of cancer [33]. RNAi pathways transcend mere expansion of the gene regulation toolkit: They confer a qualitative change in the way cellular networks are managed [34].

MECHANISM OF RNA INTERFERENCE (RNAI)

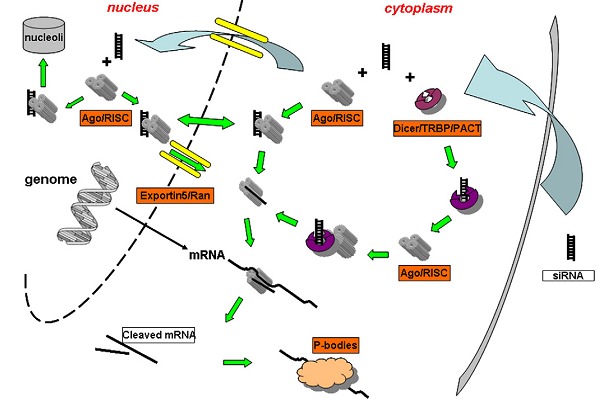

The first step of RNAi involves processing and cleavage of longer double-stranded RNA into siRNAs, generally bearing a 2 nucleotide overhang on the 3′ end of each strand. The enzyme responsible for this processing is an RNase III-like enzyme termed Dicer [35-38]. When formed, siRNAs are bound by a multiprotein component complex referred to as RISC (RNAinduced silencing complex) [39-42]. Within the RISC complex, siRNA strands are separated and the strand with the more stable 5′-end is typically integrated to the active RISC complex. The antisense single-stranded siRNA component then guides and aligns the RISC complex on the target mRNA and through the action of catalytic RISC protein, a member of the argonaute family (Ago2), mRNA is cleaved [43-47] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the siRNA mediated RNA interference pathway. After entry into the cytoplasm, siRNA is either loaded onto RISC directly or utilize a Dicer mediated process. After RISC loading, the passenger strand departs, thereby commencing the RNA interference process via target mRNA cleavage and degradation. siRNA loaded RISCs are also found to be associated with nucleolus region and maybe shuttled in and out of nucleus through an yet unidentified process [48].

ORIGINS siRNAs

Fire and Mello In 1998 uncovered the world of RNAi and revolutionized the contemporary understanding of gene regulation when they made the discovery that the silencing effectors in Caenorh abditis elegans were double stranded RNAs [49].

In 1999, siRNAs were discovered in plants and similarly demonstrated to guide sequence-dependent endonucleolytic cleavage of the mRNAs that they regulate in mammalian cells [50]. By 2001, miRNAs were found to comprise a broad class of small RNA regulators, with at least dozens of representatives in each of several animal and plant species [51]. With this discovery, in our view of the gene regulatory landscape two categories of small RNAs had become firmly embedded: siRNAs, as defenders of genome integrity in response to foreign or invasive nucleic acids such as transposons, transgenes, and viruses, and miRNAs, as regulators of endogenous genes [52].

Elbashir et al. in 2001 had successfully used synthetic siRNAs for silencing and determined the basic principles of siRNA structure and RNAi mechanics, providing the foundation for developing RNAi applications [53].

CHALLENGES WITH siRNA-BASED THERAPEUTICS

Delivering siRNA

The discovery of RNAi has excited the scientific field due to its potential for wide range of therapeutic applications [54-58]. Effective pharmacological use of siRNA requires ‘carriers’ that can deliver the siRNA to its intended site of action. The carriers assemble the siRNA into supramolecular complexes that display functional properties during the delivery process [59]. Viral vectors and non-viral vectors are two major categories delivery system for siRNA. The synthesis and industrial scalability are offer advantages of Non-viral delivery systems. Peptides, polymers, and Lipids are the extensively studied non-viral delivery vehicles [60-70].

The pharmacological mediator of siRNA, has faced significant obstacles in reaching its target site and effectively exerting its silencing activity.

The fantastic potential of siRNA to silence important genes in disease pathways comes with noteworthy challenges and barriers in its delivery.

Polymer- mediated Delivery Systems

For siRNA delivery, Polymers have emerged as an alternative class of extensively investigated carriers [71, 72]. Polymer-based delivery systems have been extensively used for plasmid DNA and more recently for siRNA [73-75]. As non-viral siRNA and plasmid vectors, many polymers have been thoroughly investigated because of their physical characteristics and diverse chemistries and well-characterized, and structure flexibilities, which allows for easy modification to fine-tune their physiochemical properties. Chitosan is reported to have low cytotoxicity and which is a cationic polysaccharide having muco adhesive properties. Cyclodextrin is another polymer that has also been studied as siRNA delivery system [76-88].

Peptide-Based Delivery Systems

Due to four major reasons, Peptides are viewed as alternative to the cationic polymers for the siRNA delivery: Cell specific delivery, pH based membrane, disruption, Their efficient packaging and Efficient membrane transport. Control over functionalization, ease of synthesis and stability of the peptide oligonucleotide complex make the low molecular weight peptides as the favorable candidates over lipoplexes as siRNA delivery vehicle [89-100].

Cell penetrating peptides (CPPs), also referred to as protein transduction domains (PTD), was observed to cross the plasma membrane by itself, which transactivates transcription of the HIV-1 genome, were first discovered a few decades ago when the HIV-1 Tat-protein. CPPs are the widely studied peptides as siRNA delivery system. The CPPs in three classes are classified: 1) synthetic ones, 2) chimeric peptides and 3) naturally derived peptides [101-106]. MPPs (Membrane perturbing peptides) are also studied as peptide delivery systems. Depending upon the DNA release behavior, The MPPs are studied in two categories: Endoosmolytic peptides and Fusogenic peptides that Fusogenic peptides act by mediating the DNA release at the endosomal pH and Endoosmolytic peptides act by endosomal lysis followed by DNA release [107].

Lipid -Based Delivery Systems

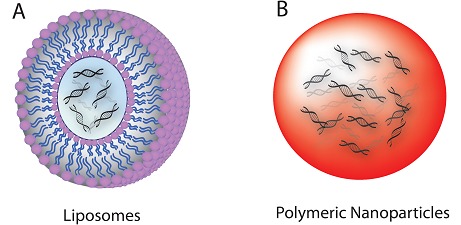

Various lipid-based delivery systems have been developed for in vivo application of siRNA. Lipid-based systems include liposomes, micelles, emulsions, and solid lipid nanoparticles [108-121].

MIT(Massachusetts Institute of Technology) and Alnylam Inc., (Cambridge, Massachusetts) collaborated on a project to synthesize a library of more than thousand different lipid-like molecules and screened them for their efficiency to deliver siRNA [122]. They tested these delivery systems in mice to treat the respiratory ailment and found that some of their molecules are ten times more efficacious in delivering siRNA in comparison to the existing non encapsulated siRNA delivery.

For the delivery of siRNA using lipid-based systems, particle size, lipid composition, drug-to lipid ratio, and the manufacturing process should be optimized.

Liposomes have been utilized as efficient delivery vectors for siRNA for almost 30 years since the successful use of lipofection in 1987 to transfer nucleic acids into animal and human cells [123, 124]. Liposomes are commonly used as delivery vehicles for a broad spectrum of therapeutics including siRNA. Interaction of the lipids with the nucleic acid leads to the formation of either coated vesicles having nucleic acid in the core or the aggregates, both of which are studied as lipoplexes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic of siRna nanocarriers. a) Liposomes. B) Polymeric nanoparticles [125].

siRNA Conjugate Delivery Systems

Combination of two or more types of delivery vehicles have led to the generation of this category. These combinations may be categorized as Peptide-Polymer, Liposome - Peptide, and Liposome-Polymer any other combination thereof [126-130].

Polymer and Liposomal-based delivery systems have been advanced the most for siRNA delivery, and have a vast supporting body of literature due to their extensive previous development for the delivery of antisense oligonucleotides, DNAzymes and plasmid DNA.

For targeted delivery of siRNAs to hepatocytes, Rozema et al. have developed a polymer-siRNA conjugate delivery system termed Dynamic PolyConjugates (DPCs) [131].

Recently, siRNA conjugates have shown promise as delivery platforms, leading to the development of well-defined, single-component systems that optimize the usage of minimal amounts of delivery material [131-134]. Studies have demonstrated invitro effectiveness of LSPCs (Liposome-siRNA-peptide complexes) in delivering PrP siRNA specifically to AchR-expressing cells, leading to suppressed PrPC expression and eliminated PrPRES formation [70].

Delivery of therapeutic siRNA in cancer

The siRNA has provided new opportunities for the development of innovative medicine to treat previously incurable diseases such as cancer [135-138]. It is of inherent potency because it exploits the endogenous RNAi pathway, allows specific reduction of disease associated genes, and is applicable to any gene with a complementary sequence [139]. For the rationale of siRNA-mediated gene therapy, genetic nature of cancer provides solid support. In fact, a number of siRNAs have been designed to target dominant oncogenes, viral oncogenes involved in carcinogenesis, or mal functionally regulated oncogenes. In addition, therapeutic siRNAs have been investigated for silencing target molecules crucial for tumor–host interactions and tumor resistance to chemo- or radiotherapy. The silencing of critical cancer-associated target proteins by siRNAs has resulted in significant antiproliferative and/or apoptotic effects [140]. However, most approaches to RNAi-mediated gene silencing for cancer therapy have been with cell cultures in the laboratory, and key impediments in the transition to the bedside due to delivery considerations still remain. Delivery systems that can improve siRNA stability and cancer cell-specificity need to be developed, nonspecific immune stimulatory effects and involve the minimizing of off-target. The delivery systems must be optimized for specific cancers, as the route of administration may differ depending on the nature of cancer. The current progress in siRNA delivery systems for liver [141], Breast [142, 143], prostate [144], and lung [145,146] cancers is discussed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Examples of siRNA delivery systems in treatment of cancers

| Delivery systems Targeted gene Property Animal model | |||

|

| |||

| Polymer | Her-2 | PEI | Ovarian cancer xenograft (147) |

| Polymer | PTN | PEI | Orthotopic glioblastoma (148) |

| Polymer | Akt1 | Poly (ester amine) | Urethane-induced lung cancer (149) |

| Liposome | Bcl-2 | Cationic liposome | Liver metastasis mouse model (150) |

| Liposome | Raf-1 | Cationic cardiolipin liposome | Prostate cancer xenograft (11) |

| Liposome | EphA2 | Neutral liposomes (DOPC) | Ovarian cancer xenograft (12) |

| Liposome | EGFR | Liposome-polycation-DNA | Lung cancer xenograft (151) |

| Liposome | Her-2 | Immunoliposome | Breast cancer xenograft (152) |

| Liposome | HBV | SNALP | HBV vector-based mouse (153) |

PEI, polyethyleneimine; SNALPs, stable nucleic acid–lipid particles.

Efficacy

In the recent years, a number of siRNAs have been successfully used in experimental models. Data from preclinical models are now giving rise to the translation of new siRNA-based therapies into clinical trials. The target selection process is extensional, requiring a thorough mining of pathways and databases [154]. Different siRNAs targeting different parts of the same mRNA sequence have varying RNAi efficacies, and only a limited fraction of siRNAs has been shown to be functional in mammalian cells [155]. Among randomly selected siRNAs, 58–78% were observed to induce silencing with greater than 50% efficiency and only 11–18% induced 90–95% silencing [156].

Off-target silencing effect

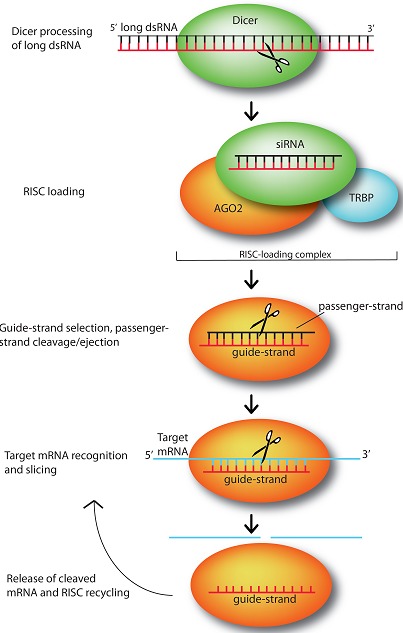

An early glimpse into the possible existence of off-target gene regulation by siRNAs came from gene expression profiling of siRNA studies. The specificity of RNAi is not as robust as it was initially thought to be. It is now well established that siRNA off-targets exist for many siRNA and that most siRNA molecules are probably not as specific as once thought. The introduction of siRNA can result in off-target effect, i.e. the suppression of genes other than the desired gene target, leading to dangerous mutations of gene expression and unexpected consequences [157]. The majority of the off-target gene silencing of siRNA is due to the partial sequence homology, especially within the 3’untranslated region (3’UTR), exists with mRNAs other than the intended target mRNA [158]. This mechanism is similar to the microRNA (miRNA) gene silencing effect. The off-target effect can also be a result of the immune response. RNA is recognized by immunoreceptors such as TLRs (Toll-like receptors) [159], leading to the release of cytokines and changes in gene expression. Although the sequence dependence of the immune response is not fully understood, some immunostimulatory motifs have been identified and they should be avoided [160]. Chemical modification of siRNA, such as 2’-O-methylation of the lead siRNA strand can also taper the miRNA-like off-target effects as well as the immunostimulatory activity without losing silencing effect of the target gene. Overall, therapeutic siRNA must be carefully designed. A combination of computer algorithms and empirica testing is also encouraged to allow effective design of potent siRNA sequences and minimize off-target effect (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

siRNA mediate silencing of target genes by guiding sequence dependent slicing of their target mRNAs. These non-coding, silencing RNAs begin as long dsRNA molecules, which are processed by endonuclease Dicer into short, active ~21-25 nt constructs. Once generated, a siRNA duplex is loaded by Dicer, with the help of RNA-binding protein TRBP, onto Argonaute (AGO2), the heart of the RNA-induced silencing complex (which here is represented just by AGO2). upon loading, AGO2 selects the siRNA guide strand, then cleaves and ejects the passenger strand. While tethered to AGO2, the guide strand subsequently pairs with its complementary target mRNAs long enough for AGO2 to slice the target. After slicing, the cleaved target mRNA is released and RISC is recycled, using the same loaded guide strand for another few rounds of slicing [161]

CONCLUSION

The design and engineering of siRNA carriers gained significant momentum in recent years, as a result of accumulation of predictable and therapeutically promising molecular targets. RNAi technology has progressed rapidly from an academic discovery to a potential new class of treatment for human disease. Initial observations that were useful for studying gene function in worms were quickly translated to other organisms, and in particular to mammals, revealing the potential clinical applications of siRNA, including an ability to induce persistent, potent, and specific silencing of a wide range of genetic targets. For any new therapeutics, safety is still the primary concern. While the off-target effect of siRNA is a major issue that needs to be addressed by improving the knowledge in this area, the long-term safety of siRNA is still not clear.

siRNA therapeutics are now well poised to enter the clinical formulary as a new class of drugs in the near future. siRNA-based therapies are emerging as a promising new anticancer approach, and a small number of Phase I clinical trials involving patients with solid tumours have now been completed. siRNA-based therapeutics hold great potential for cancer therapy and treatment of other diseases. However, many challenges, including rapid degradation, poor cellular uptake, and off-target effects, need to be addressed in order to carry these molecules into clinical trials. siRNA therapeutics have several distinct advantages over traditional pharmaceutical drugs. RNAi is an endogenous biological process, so almost all genes can be potently suppressed by siRNA. The identification of highly selective and inhibitory sequences is much faster than the discovery of new chemicals, and it is relatively easy to synthesize and manufacture siRNA on a large scale. As the treatment of cancers usually requires systemic delivery rather than more easily achievable local delivery, the progress of siRNA treatment for cancer has been relatively slow compared with that of other diseases curable by local siRNA administration.

Delivery, especially systemically administered siRNA, is another important barrier to be overcome. Although new materials and delivery systems are being investigated to enhance the delivery efficiency, approval procedures could be hindered by the complicated formulation. On the other hand, eyes and lungs are promising tissues for local delivery of naked siRNA, especially the former, which is reflected by the high number of clinical trial studies targeting this site. It is not surprising to see the first siRNA therapeutics to be approved is for ocular therapy in the very near future.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carthew RW, Sontheimer WJ. Origins and Mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell. 2009;136:642–655. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson RC, Doudna JA. Molecular Mechanisms of RNA Interference. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2013;42:217–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-083012-130404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carthew RW, Sontheimer EJ. Origins and mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell. 2009;136(4):55–642. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gunawardane LS, Saito K, Nishida KM, Miyoshi K, et al. A slicer-mediated mechanism for repeat-associated siRNA 5 end formation in Drosophila. Science. 2007;315(5818):1587–1590. doi: 10.1126/science.1140494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yigit E, Batista PJ, Bei Y, Pang KM, et al. Analysis of the C. elegans Argonaute family reveals that distinct Argonautes act sequentially during RNAi. Cell. 2006;127:747–757. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaikkonen MU, Lam MT, Glass CK. Non-coding RNAs as regulators of gene expression and epigenetics. Cardiovasc. Res. 2011;90(3):430–440. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batista PJ, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNAs: cellular address codes in development and disease. Cell. 2013;152(6):1298–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, et al. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Endoh T, Ohtsuki T. Cellular siRNA delivery using cell-penetrating peptides modified for endosomal escape. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2009;61:704–709. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oh YK, Park TG. siRNA delivery systems for cancer treatment. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2009;61:850–862. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pal A, Ahmad A, Khan S, Sakabe I, et al. Systemic delivery of Raf siRNA using cationic cardiolipin liposomes silences Raf-1 expression and inhibits tumor growth in xenograft model of human prostate cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 2005;26:1087–1091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landen CN, Jr., Chavez-Reyes A, Bucana CR, Schmandt MT, et al. Sood, Therapeutic EphA2 gene targeting in vivo using neutral liposomal small interfering RNA delivery. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6910–6918. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubin MA. Targeted therapy of cancer: new roles for pathologists-prostate cancer. Mod. Pathol. 2008;21(2):44–55. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soutschek J, Akinc A, Bramlage BK, Charisse R, et al. Vornlocher, Therapeutic silencing of an endogenous gene by systemic administration of modified siRNAs. Nature. 2004;432:173–178. doi: 10.1038/nature03121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aigner A. Nonviral in vivo delivery of therapeutic small interfering RNAs. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 2007;9:345–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santel A, Aleku M, Keil O, Endruschat J, et al. RNA interference in the mouse vascular endothelium by systemic administration of siRNA–lipoplexes for cancer therapy. Gene Ther. 2006;13:1360–1370. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juliano R, Alam MR, Dixit V, Kang H. Mechanisms and strategies for effective delivery of antisense and siRNA oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:4158–4171. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watts K, Deleavey GF, Damha MJ. Chemically modified siRNA: tools and applications. Drug Discov. 2008;13:842–855. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeong JH, Kim SW, Park TG. Molecular design of functional polymers for gene therapy. Prog. Polym. Sc. 2007;32:1239–1274. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iorns EC, Lord J, Turner N, Ashworth A. Utilizing RNA interference to enhance cancer drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007;6:556–568. doi: 10.1038/nrd2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo P, Coban O, Snead NM, Trebley J, et al. Engineering RNA for targeted siRNA delivery and medical application. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62(6):650–666. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Li Z, Han Y, Liang LH, et al. Nanoparticle-based delivery system for application of siRNA in vivo . Curr. Drug Metab. 2010;11(2):182–196. doi: 10.2174/138920010791110863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bumcrot D, Manoharan M, Koteliansky V, Sah DW. RNAi therapeutics: a potential new class of pharmaceutical drugs. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:711–719. doi: 10.1038/nchembio839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho W, Zhang X Q, Xu X. Biomaterials in siRNA Delivery: A Comprehensive Review. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2016:1–17. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201600418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song E, Lee SK, Wang J, Ince N, et al. RNA interference targeting Fas protects mice from fulminant hepatitis. Nat. Med. 2003;9:347–351. doi: 10.1038/nm828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Andaloussi S, Lakhal S, Mager I, Wood MJ. Exosomes for targeted siRNA delivery across biological barriers. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013 Mar;65(3):391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Check E. A tragic setback. Nature. 2002;420:116–118. doi: 10.1038/420116a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nguyen T, Menocal EM, Harborth J, Fruehauf JH. RNAi therapeutics: an update on delivery. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 2008;10:158–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pecot CV, Calin GA, Coleman RL, Lopez-Berestein G, et al. RNA interference in the clinic: challenges and future directions. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2011;11:59–67. doi: 10.1038/nrc2966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brummelkamp TR, Bernards R, Agami R. A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science. 2002;296:550–553. doi: 10.1126/science.1068999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miele E, Spinelli GP, Miele E, Di Fabrizio E, et al. Nanopar ticle-based delivery of small interfering RNA: challenges for cancer therapy. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2012;7:3637–3657. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S23696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rother S, Meister G. Small RNAs derived from longer non-coding RNAs. Biochimie. 2011;93:1905–1915. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu M, Zhang Q, Deng M, Miao J, Guo Y, et al. An analysis of human microRNA and disease associations. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(10):e3420. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berezikov E. Evolution of microRNA diversity and regulation in animals. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12(12):846–860. doi: 10.1038/nrg3079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishina K, Unno T, Uno Y, Kubodera T, et al. Efficient in vivo delivery of siRNA to the liver by conjugation of alpha tocopherol. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:734–740. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernstein E, Caudy AA, Hammond SM, Hannon GJ. Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature. 2001;409:363–366. doi: 10.1038/35053110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim DH, Behlke MA, Rose SD, Chang MS, et al. Synthetic dsRNA Dicer substrates enhance RNAi potency and efficacy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:222–226. doi: 10.1038/nbt1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McNamara JO, Andrechek ER, Wang Y, Viles KD, et al. Cell type-specific delivery of siRNAs with aptamersiRNA chimeras. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:1005–1015. doi: 10.1038/nbt1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hammond SM, Bernstein E, Beach D, Hannon GJ, et al. An RNA-directed nuclease mediates post-transcriptional gene silencing in Drosophila cells. Nature. 2000;404:293–296. doi: 10.1038/35005107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen PY, Weinmann L, Gaidatzis D, Pei Y, et al. Strand-specific 5’-Omethylation of siRNA duplexes controls guide strand selection and targeting specificity. RNA. 2008;14:263–274. doi: 10.1261/rna.789808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khvorova A, Reynolds A, Jayasena SD. Functional siRNAs and miRNAs exhibit strand bias. Cell. 2003;115:209–216. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00801-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jackson AL, Bartz SR, Schelter J, Kobayashi SV, et al. Expression profiling reveals off-target gene regulation by RNAi. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:635–637. doi: 10.1038/nbt831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Song JJ, Smith SK, Hannon GJ, Joshua-Tor L. Crystal structure of Argonaute and its implications for RISC slicer activity. Science. 2004;305:1434–1437. doi: 10.1126/science.1102514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zamore PD, Tuschl T, Sharp PA, Bartel DP. RNAi: double-stranded RNA directs the ATP-dependent cleavage of mRNA at 21 to 23 nucleotide intervals. Cell. 2000;101:25–33. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80620-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meister G, Landthaler M, Patkaniowska A, Dorsett Y, et al. Human Argonaute2 mediates RNA cleavage targeted by miRNAs and siRNAs. Mol. Cell. 2004;15:185–197. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choung S, Kim YJ, Kim S, Park HO, et al. Chemical modification of siRNAs to improve serum stability without loss of efficacy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;342(3):919–927. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu J, Carmell MA, Rivas FV, Marsden CG, et al. Argonaute2 is the catalytic engine of mammalian RNAi. Science. 2004;305:1437–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.1102513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rao DD, Vorhies JS, Senzer N, Nemunaitis J. siRNA vs. shRNA: similarities and differences. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61(9):746–759. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, et al. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391(6669):806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tomari Y, Zamore PD. Perspective: machines for RNAi. Genes Dev. 2005;19:517–529. doi: 10.1101/gad.1284105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meister G, Tuschl T. Mechanisms of gene silencing by doublestranded RNA. Nature. 2004;431:343–498. doi: 10.1038/nature02873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elbashir SM, Harborth J, Lendeckel W, Yalcin A, et al. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature. 2001;411:494–498. doi: 10.1038/35078107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schaffert D, Wagner E. Gene therapy progress and prospects: synthetic polymerbased systems. Gene Ther. 2008;15:1131–1138. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kumar P, et al. T cell-specific siRNA delivery suppresses HIV-1 infection in humanized mice. Cell. 2008;134:577–586. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang S, Zhao B, Jiang H, Wang B, et al. Cationic lipids and polymers mediated vectors for delivery of siRNA. J. Control Release. 2007;123:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kumar P, et al. Transvascular delivery of small interfering RNA to the central nervous system. Nature. 2007;448:39–43. doi: 10.1038/nature05901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zuhorn IS, Engberts JB, Hoekstra D. Gene delivery by cationic lipid vectors: overcoming cellular barriers. Eur. Biophys. J. 2007;36:349–362. doi: 10.1007/s00249-006-0092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aliabadi HM, Landry B, Sun C, Tang T, et al. Supramolecular assemblies in functional siRNA delivery: where do we stand? Biomaterials. 2012;33(8):2546–2569. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.11.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Verma V, Sangave P. REVIEW ON NON-VIRAL DELIVERY SYSTEMS FOR siRNA. IJPSR. 2014;5(2):294–301. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yin H, Kanasty RL, Eltoukhy AA, Vegas AJ, et al. Non-viral vectors for gene-based therapy. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15(8):541–555. doi: 10.1038/nrg3763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li W, Szoka FC., Jr Lipid-based nanoparticles for nucleic acid delivery. Pharm Res. 2007;24(3):438–449. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dorasamy S, Narainpersad N, Singh M, et al. Novel targeted liposomes deliver sirna to hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro . Chem Biol Drug Des. 2012;80:647–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2012.01446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim WJ, Kim SW. Efficient siRNA delivery with non-viral polymeric vehicles. Pharm Res. 2009;26:657–666. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9774-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kunath K, von Harpe A, Fischer D, Petersen H, et al. Lowmolecular-weight polyethylenimine as a non-viral vector for DNA delivery: comparison of physicochemical properties, transfection efficiency and in vivo distribution with high-molecular-weight polyethylenimine. J. Control Rel. 2003;89(1):113–125. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sato Y, Hatakeyama H, Sakurai Y, et al. A pH-sensitive cationic lipid facilitates the delivery of liposomal siRNA and gene silencing activity in vitro and in vivo . J Control Release. 2012;163:267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gomes-da-Silva LC, Fernandez Y, Abasolo I, et al. Efficient intracellular delivery of siRNA with a safe multitargeted lipid-based nanoplatform. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2013;8:1397–1413. doi: 10.2217/nnm.12.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guo J, Fisher KA, Darcy R, Cryan JF, et al. Therapeutic targeting in the silent era: advances in non-viral siRNA delivery. Mol. Biosyst. 2010;6(7):1143–1161. doi: 10.1039/c001050m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang XLi, Huang L. Non-viral nanocarriers for siRNA delivery in breast cancer. J. Control. Release. 2014;190:440–450. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pulford B, Reim N, Bell A, et al. Liposome-siRNApeptide complexes cross the blood-brain barrier and significantly decrease PrP on neuronal cells and PrP in infected cell cultures. PLoS One. 2010;5:11085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu ZW, Chien CT, Liu CY, Yan JY, et al. J. Drug Target. 2012;20:551. doi: 10.3109/1061186X.2012.699057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Akhtar S, Benter IF. Clin J. Invest. 2007;117:3623. doi: 10.1172/JCI33494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jere D, Jiang HL, Arote R, Kim YK, et al. Expert Opin. Drug Delivery. 2009;6:827. doi: 10.1517/17425240903029183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gary DJ, Puri N, Won YY. Polymer-based siRNA delivery: perspectives on the fundamental and phenomenological distinctions from polymer-based DNA delivery. J. Control. Release. 2007;121:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lungwitz U, Breunig M, Blunk T, Gopferich A. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2005;60:247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kortylewski M, et al. In vivo delivery of siRNA to immune cells by conjugation to a TLR9 agonist enhances antitumor immune responses. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009;27:925–932. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boussif O, Zanta MA, Behr JP. Optimized galenics improve in vitro gene transfer with cationic molecules up to 1000-fold. Gene Ther. 1996;3:1074–1080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Soutschek J, et al. Therapeutic silencing of an endogenous gene by systemic administration of modified siRNAs. Nature. 2004;432:173–178. doi: 10.1038/nature03121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Felber AE, Dufresne MH, Leroux JC. pH-sensitive vesicles, polymeric micelles, and nanospheres prepared with polycarboxylates. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:979–992. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rozema DB, et al. Dynamic PolyConjugates for targeted in vivo delivery of siRNA to hepatocytes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:12982–12987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703778104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hunter AC. Molecular hurdles in polyfectin design and mechanistic background to polycation induced cytotoxicity. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2006;58:1523–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Thurston TL, Wandel M, von Muhlinen MP, Foeglein N, et al. Galectin 8 targets damaged vesicles for autophagy to defend cells against bacterial invasion. Nature. 2012;482:414–418. doi: 10.1038/nature10744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cheung CY, Murthy N, Stayton PS, et al. A pH-sensitive polymer that enhances cationic lipid-mediated gene transfer. Bioconjug Chem. 2001;12:906–910. doi: 10.1021/bc0100408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rajeev KG, et al. Hepatocyte-specific delivery of siRNAs conjugated to novel non-nucleosidic trivalent N-acetylgalactosamine elicits robust gene silencing in vivo . Chem. BioChem. 2015;16:903–908. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201500023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fischer D, von Harpe A, Kunath K, Petersen H, et al. Copolymers of ethylene imine and N-(2-hydroxyethyl)-ethyleneimine as tools to study effects of polymer structure on physicochemical and biological properties of DNA complexes. Bioconjug. Chem. 2002;13:1124–1133. doi: 10.1021/bc025550w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Biessen EA, et al. Synthesis of cluster galactosides with high affinity for the hepatic asialoglycoprotein receptor. J. Med. Chem. 1995;38:1538–1546. doi: 10.1021/jm00009a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wong SC, et al. Co-injection of a targeted, reversibly masked endosomolytic polymer dramatically improves the efficacy of cholesterolconjugated small interfering RNAs in vivo . Nucleic Acid Ther. 2012;22:380–390. doi: 10.1089/nat.2012.0389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hou KK, Pan H, Schlesinger PH, Wickline SA. A role for peptides in overcoming endosomal entrapment in siRNA delivery – a focus on melittin. Biotechnol Adv. 2015;33(9 Pt 1):931–940. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Adami RC, Rice KG. Metabolic stability of glutaraldehyde cross-linked peptide DNA condensates. J. Pharm. Sci. 1999;88(8):739–746. doi: 10.1021/js990042p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Choi SW, Lee SH, Mok H, Park TG. Multifunctional siRNA delivery system: polyelectrolyte complex micelles of six-arm PEG conjugate of siRNA and cell penetrating peptide with crosslinked fusogenic peptide. Biotechnol. Prog. 2010;26:57–63. doi: 10.1002/btpr.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Oliveira S, van Rooy I, Kranenburg O, Storm G, et al. Fusogenic peptides enhance endosomal escape improving siRNAinduced silencing of oncogenes. Int. J. Pharm. 2007;331:211–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Song E, et al. Antibody mediated in vivo delivery of small interfering RNAs via cell-surface receptors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:709–717. doi: 10.1038/nbt1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hatakeyama H, Ito E, Akita H, et al. A pH-sensitive fusogenic peptide facilitates endosomal escape and greatly enhances the gene silencing of siRNA-containing nanoparticles in vitro and in vivo . J Control Release. 2009;139:127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hou KK, Pan H, Ratner L, Schlesinger PH, et al. Mechanisms of nanoparticle-mediated siRNA transfection by melittin-derived peptides. ACS Nano. 2013;7(10):8605–8615. doi: 10.1021/nn403311c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Peer D, Zhu P, Carman CV, Lieberman J, et al. Selective gene silencing in activated leukocytes by targeting siRNAs to the integrin lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:4095–4100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608491104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gallarate M, Battaglia L, Peira E, Trotta M. Peptide-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles prepared through coacervation technique. International Journal of Chemical Engineerin. 2011:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kumar P, et al. T cell-specific siRNA delivery suppresses HIV-1 infection in humanized mice. Cell. 2008;134:577–586. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Barrett SE, et al. Development of a liver-targeted siRNA delivery platform with a broad therapeutic window utilizing biodegradable polypeptide-based polymer conjugates. J. Control. Release. 2014;183:124–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1.Chiarantini L, Cerasi A, Fraternale A, et al. Comparison of a noveldelivery system for antisense peptide nucleid acids. J. Control Release. 2005;109:24–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yao YD, et al. Targeted delivery of PLK1-siRNA by ScFv suppresses Her2+ breast cancer growth and metastasis. Sci. Transl Med. 2012;4:130–148. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Green M, Loewenstein PM. Autonomous functional domains of chemically synthesized human immunodeficiency virus tat trans-activator protein. Cell. 1988;55:1179–1188. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tunnemann G, Martin RM, Haupt S, Patsch C, et al. Cargodependent mode of uptake and bioavailability of TAT-containing proteins and peptides in living cells. FASEB J. 2006;20:1775–1784. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5523com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chiu YL, Ali A, Chu CY, Cao H, et al. Visualizing a correlation between siRNA localization, cellular uptake, and RNAi in living cells. Chem. Biol. 2004;11:1165–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Moschos SA, Jones SW, Perry MM, Williams AE, et al. Lung delivery studies using siRNA conjugated to TAT(48–60) and penetratin reveal peptide induced reduction in gene expression and induction of innate immunity. Bioconjug. Chem. 2007;18:1450–1459. doi: 10.1021/bc070077d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Frankel AD, Pabo CO. Cellular uptake of the Tat protein from human immunodeficiency virus. Cell. 1988;55:1189–1193. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pujals S, Fernandez-Carneado J, Lopez-Iglesias C, Kogan MJ, et al. Mechanistic aspects of CPP-mediated intracellular drug delivery: relevance of CPP self-assembly. Biochim Biophys. Acta. 2006;1759(3):264–279. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wagner E. Application of membrane-active peptides for nonviral gene delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1999;38:279–289. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(99)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zuhorn IS, Engberts JB, Hoeckstra D. Gene delivery by cationic lipid vectors: overcoming cellular barriers. Eur. Biophys J. 2007;36:349–362. doi: 10.1007/s00249-006-0092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Liu Y, Zhu YH, Mao CQ, Dou S, et al. Triple negative breast cancer therapy with CDK1 siRNA delivered by cationic lipid assisted PEG-PLA nanoparticles. J. Control. Release. 2014;192:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kim SI, Shin D, Choi TH, Lee JC, et al. Systemic and specific delivery of small interfering RNAs to the liver mediated by apolipoprotein A-I. Mol. Ther. 2007;15:1145–1152. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Akinc A, Zumbuehl A, Goldberg M, Leshchiner ES, et al. A combinatorial library of lipid-like materials for delivery of RNAi therapeutics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:561–569. doi: 10.1038/nbt1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Dreyer JL. Lentiviral vector-mediated gene transfer and RNA silencing technology in neuronal dysfunctions. Mol. Biotechnol. 2011;47(2):169–187. doi: 10.1007/s12033-010-9334-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yagi N, Manabe I, Tottori T, Ishihara A, et al. A nanoparticle system specifically designed to deliver short interfering RNA inhibits tumor growth in vivo . Cancer Res. 2009;69:6531–6538. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhang J, et al. Assessing the heterogeneity level in lipid nanoparticles for siRNA delivery: size-based separation, compositional heterogeneity, and impact on bioperformance. Mol. Pharm. 2013;10:397–405. doi: 10.1021/mp3005337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Semple SC, Akinc A, Chen J, Sandhu AP, et al. Rational design of cationic lipids for siRNA delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:172–176. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Couto LB, High KA. Viral vector-mediated RNA interference. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2010;10(5):534–542. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hobo W, Novobrantseva TI, Fredrix H, Wong J, et al. Improving dendritic cell vaccine immunogenicity by silencing PD-1 ligands using siRNA-lipid nanoparticles combined with antigen mRNA electroporation. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2013;62:285–297. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1334-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zimmermann TS, Lee AC, Akinc A, Bramlage B, et al. RNAi-mediated gene silencing in non-human primates. Nature. 2006;441:111–114. doi: 10.1038/nature04688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gibbings DJ, Ciaudo C, Erhardt M, Voinnet O. Multivesicular bodies associate with components of miRNA effector complexes and modulate miRNA activity. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009;11:1143–1149. doi: 10.1038/ncb1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Castanotto D, Rossi JJ. The promises and pitfalls of RNA-interference-based therapeutics. Nature. 2009;457(7228):426–433. doi: 10.1038/nature07758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lee JB, Zhang K, Tam YY, Tam YK, et al. Lipid nanoparticle siRNA systems for silencing the androgen receptor in human prostate cancer in vivo . Int. J. Cancer. 2012;131:E781–E790. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Akinc A, Zumbuehl A, Goldberg M, et al. A combinatorial library of lipid-like materials for delivery of RNAi therapeutics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:561–569. doi: 10.1038/nbt1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Malone RW, Felgner PL, Verma IM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:6077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.16.6077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Felgner PL, Gadek TR, Holm M, Roman R, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:7413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Gavrilov K, Saltzman WM. Therapeutic siRna: Principles, challenges, and strategies. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 2012;85:187–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Lee SK, Siefert A, Beloor J, et al. Cell-specific siRNA delivery by peptides and antibodies. Methods Enzymol. 2012;502:91–122. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-416039-2.00005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Cesarone G, Edupuganti OP, Edupuganti CP, Wickstrom E. Insulin receptor substrate 1 knockdown in human MCF7 ER+ breast cancer cells by nuclease-resistant IRS1 siRNA conjugated to a disulfide-bridged D-peptide analogue of insulinlike growth factor 1. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007;18:1831–1840. doi: 10.1021/bc070135v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lorenz C, Hadwiger P, John M, Vornlocher HP, et al. Steroid and lipid conjugates of siRNAs to enhance cellular uptake and gene silencing. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14(19):4975–4977. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Blum JS, Saltzman WM. High loading efficiency and tunable release of plasmid DNA encapsulated in submicron particles fabricated from PLGAconjugated with poly-L-lysine. J. Control Release. 2008;129(1):66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kataoka K, Harada A, Nagasaki Y. Block copolymer micelles for drug delivery: design, characterization and biological significance. Adv. Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;47(1):113–131. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Rozema DB, Lewis DL, Wakefield DH, Wong SC, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:12982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703778104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Jackson AL, Linsley PS. Recognizing and avoiding siRNA off-target effects for target identification and therapeutic application. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010;9(1):57–67. doi: 10.1038/nrd3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Bobbin ML, Rossi JJ. RNA interference (RNAi)-based therapeutics:delivering on the promise? Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016;56:103–122. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010715-103633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Castanotto D, Rossi JJ. The promises and pitfalls of RNA-interferencebased therapeutics. Nature. 2009;457:426–433. doi: 10.1038/nature07758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Bora RS, Gupta D, Mukkur TK, Saini KS. RNA interference therapeutics for cancer: challenges and opportunities (review) Mol. Med. Rep. 2012;6:9–15. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Taratula O, Garbuzenko O, Savla R, Wang YA, et al. Multifunctional nanomedicine platform for cancer specific delivery of siRNAby superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles-dendrimer complexes. Curr Drug Deliv. 2011;8(1):59–69. doi: 10.2174/156720111793663642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Hu-Lieskovan S, Heidel JD, Bartlett DW, Davis ME, et al. Sequence-specific knockdown of EWS-FLI1 by targeted, nonviral delivery of small interfering RNA inhibits tumor growth in a murine model of metastatic Ewing’s sarcoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65(19):8984–8992. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Yano J, Hirabayashi K, Nakagawa S, Yamaguchi T, et al. Antitumor activity of small interfering RNA/cationic liposome complex in mouse models of cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10:7721–7726. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Leung RK, Whittaker PA. RNA interference: from gene silencing to gene-specific therapeutics. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005;107:222–239. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Pai SI, Lin YY, Macaes P, Meneshian A, et al. Prospects of RNA interference therapy for cancer. Gene Ther. 2006;13:464–477. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Lorenz C, Hadwiger P, John M, Vornlocher HP, et al. Steroid and lipid conjugates of siRNAs to enhance cellular uptake and gene silencing in liver cells. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14(19):4975–4977. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Pille JY, Li H, Blot E, Bertrand JR, et al. Intravenous delivery of anti-RhoA small interfering RNA loaded in nanoparticles of chitosan in mice: safety and efficacy in xenografted aggressive breast cancer. Hum Gene Ther. 2006;17(10):1019–1026. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Bedi D, Musacchio T, Fagbohun OA, Gillespie JW, et al. Delivery of siRNA into breast cancer cells via phage fusion proteintargeted liposomes. Nanomedicine. 2011;7(3):315–323. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Kim SH, Lee SH, Tian H, Chen X, et al. Prostate cancer cell-specific VEGF siRNA delivery system using cell targeting peptide conjugated polyplexes. J. Drug Target. 209;17(4):311–317. doi: 10.1080/10611860902767232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Zamora MR, Budev M, Rolfe M, Gottlieb J, et al. RNA interference therapy in lung transplant patients infected with respiratory syncytial virus. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 2011;183(4):531–538. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201003-0422OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Li S, Wu SP, Whitmore M, Loeffert EJ, et al. Effect of immune response on gene transfer to the lung via systemic administration of cationic lipidic vectors. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276(5Pt 1):L796–804. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.5.L796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Urban-Klein B, Werth S, Abuharbeid S, Czubayko F, et al. RNAi-mediated gene-targeting through systemic application of polyethylenimine (PEI)-complexed siRNA in vivo . Gene Ther. 2005;12:461–466. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Grzelinski M, Urban-Klein B, Martens T, Lamszus K, et al. RNA interference-mediated gene silencing of pleiotrophin through polyethylenimine-complexed small interfering RNAs in vivo exerts antitumoral effects in glioblastoma xenografts. Hum. Gene Ther. 2006;17:751–766. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Xu CX, Jere D, Jin H, Chang SH, et al. Poly (ester amine)-mediated, aerosol-delivered Akt1 small interfering RNA suppresses lung tumorigenesis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2008;178:60–73. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200707-1022OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Yano J, Hirabayashi K, Nakagawa S, Yamaguchi T, et al. Antitumor activity of small interfering RNA/cationic liposome complex in mouse models of cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10:7721–7726. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Li SD, Chen YC, Hackett MJ, Huang L. Tumor-targeted delivery of siRNA by selfassembled nanoparticles. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:163–169. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Hogrefe RI, Lebedev AV, Zon G, Pirollo KF, et al. Chemically modified short interfering hybrids (siHYBRIDS): nanoimmunoliposome delivery in vitro and in vivo for RNAi of HER-2. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2006;25:889–907. doi: 10.1080/15257770600793885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Morrissey DV, Lockridge JA, Shaw L, Blanchard K, et al. Potent and persistent in vivo anti-HBV activity of chemically modified siRNAs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:1002–1007. doi: 10.1038/nbt1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Yiu SM, Wong PW, Lam TW, Mui YC, et al. Filtering of ineffective siRNAs and improved siRNA design tool. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(2):144–151. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Naito Y, Ui-Tei K. Designing functional siRNA with reduced off-target effects. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013;942:57–68. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-119-6_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Chalk AM, Wahlestedt C, Sonnhammer EI. Improved and automated prediction of effective siRNA. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;319(1):264–274. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Jenny KW, Lam J, Alan J Worsley. What is the Future of SiRNA Therapeutics? J. Drug Des Res. 2014;1(1):1005. [Google Scholar]

- 158.Birmingham A, Anderson EM, Reynolds A, Ilsley-Tyree D, et al. 3’ UTR seed matches, but not overall identity, are associated with RNAi off-targets. Nat Methods. 2006;3:199–204. doi: 10.1038/nmeth854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Watts JK, Deleavey GF, Damha MJ. Chemically modified siRNA: tools and applications. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:842–855. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Judge AD, Sood V, Shaw JR, Fang D, et al. Sequence-dependent stimulation of the mammalian innate immune response by synthetic siRNA. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:457–462. doi: 10.1038/nbt1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Jinek M, Doudna JA. A three-dimensional view of the molecular machinery of RNA interference. Nature. 2009;457(7228):405–412. doi: 10.1038/nature07755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]