This study assesses the most attractive lip dimensions of white women based on attractiveness ranking of surface area, ratio of upper to lower lip, and dimensions of the lip surface area relative to the lower third of the face.

Key Points

Question

What lip dimensions are the most attractive in white women?

Findings

All 100 faces were cardinally ranked by 150 individuals in phase 1, and all 60 faces were cardinally ranked by 428 participants in phase 2. In a survey of attractiveness, an increase of 53.5% in the total lip surface area with a linear dimension equal to 9.6% of the lower face and an upper to lower lip ratio of 1:2 was found to be the most attractive.

Meanings

These findings indicate a quantifiable approach to determining the most attractive lip proportions used in augmentation procedures.

Abstract

Importance

Aesthetic proportions of the lips and their effect on facial attractiveness are poorly defined. Established guidelines would aid practitioners in achieving optimal aesthetic outcomes during cosmetic augmentation.

Objective

To assess the most attractive lip dimensions of white women based on attractiveness ranking of surface area, ratio of upper to lower lip, and dimensions of the lip surface area relative to the lower third of the face.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In phase 1 of this study, synthetic morph frontal digital images of the faces of 20 white women ages 18 to 25 years old were used to generate 5 varied lip surface areas for each face. These 100 faces were cardinally ranked by attractiveness through our developed conventional and internet-based focus groups by 150 participants. A summed ranking score of each face was plotted to quantify the most attractive surface area. In phase 2 of the study, 4 variants for each face were created with 15 of the most attractive images manipulating upper to lower lip ratios while maintaining the most attractive surface area from phase 1. A total of 60 faces were created, and each ratio was ranked by attractiveness by 428 participants (internet-based focus groups). In phase 3, the surface area from the most attractive faces was used to determine the total lip surface area relative to the lower facial third. Data were collected from March 1 to November 31, 2010, and analyzed from June 1 to October 31, 2016.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Most attractive lip surface area, ratio of upper to lower lip, and dimension of the lips relative to the lower facial third.

Results

In phase 1, all 100 faces were cardinally ranked by 150 individuals (internet-based focus groups [n = 130] and raters from conventional focus groups [conventional raters] [n = 20]). In phase 2, all 60 faces were cardinally ranked by 428 participants (internet-based focus groups [n = 408] and conventional raters [n = 20]). The surface area that corresponded to the range of 2.0 to 2.5 × 104 pixels represented the highest summed rank, generating a pool of 14 images. This surface area was determined to be the most attractive and corresponded to a 53.5% increase in surface area from the original image. With the highest mean and highest proportions of most attractive rankings, the 1:2 ratio was deemed most attractive. Conversely, the ratio of 2:1 was deemed least attractive, having the lowest mean at 1.61 and the highest proportion of ranks within 1 with 310 votes (72.3%).

Conclusions and Relevance

Using a robust sample size, this study found that the most attractive lip surface area represents a 53.5% increase from baseline, an upper to lower lip ratio of 1:2, and a surface area equal to 9.6% of the lower third of the face. Lip dimensions and ratios derived in this study may provide guidelines in improving overall facial aesthetics and have clinical relevance to the field of facial plastic surgery.

Level of Evidence

NA.

Introduction

Well-defined and full lips convey youth and attractiveness, representing a key feature of the lower facial third. Whether the goal is to restore the senile lip to its previous youthful glory or mimic the pouty appearance of the social media starlet, lip augmentation has become an increasing trend. Popular cosmetic procedures designed for augmentation range from temporary injectable dermal fillers (ie, hyaluronic acid) to structural fat grafting and soft alloplastic implants. Although dermal fillers for lip enhancement are relatively low cost and generally safe, aesthetic guidelines to direct the clinician in lip augmentation remain elusive and are primarily based on patient preference and surgeon eye.

Quantitative tools used to evaluate fullness include quantifying proportions in lip volume with 2-dimensional analysis using anthropometric measurements from patient photographs, digital morphs, and proportions of the vermillion height to other measurements in the lower facial third. In addition, several validated tools for evaluating the appearance of the lip have been proposed. Although these methods are promising, there is currently no accepted dimension considered most attractive or ideal other than the subjective concept of fuller lips. A putative ideal height ratio of the midline upper to lower lip in white individuals has been previously defined as 1:1.6 based on the golden ratio, with an upper lip projection of 3.5 mm and a lower lip projection of 2.2 mm on lateral view. Although symmetry, fullness, and well-demarcated vermillion borders are timeless features of the aesthetic lip, the ideal lip shape may be subject to stylistic changes based on current trends and has not been systematically evaluated. The aim of this study is to use our previously established focus group process to determine (1) the most attractive lip surface area (SA) of white women, (2) the most attractive upper to lower lip ratio, and (3) the total lip SA relative to the lower third of the face.

Methods

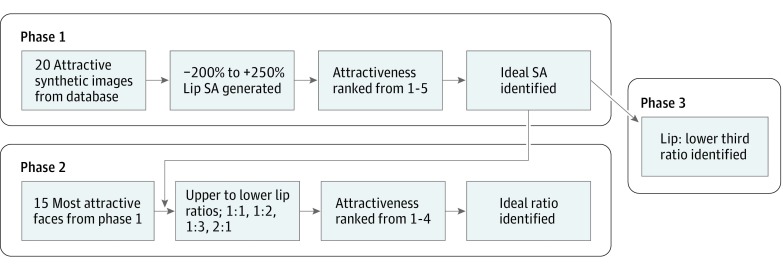

The general study design is shown in Figure 1. Data were collected from March 1 to November 31, 2010, and analyzed from June 1 to October 31, 2016. Using a database of synthetic images previously rated by attractiveness, we determined the most attractive SA of the lip. Keeping this SA constant, the upper to lower lip ratios of the most attractive faces from phase 1 were adjusted and an additional survey administered to define the most attractive ratio. The most attractive SAs were used to generate a ratio of the SA of the lips to the SA of the lower facial third.

Figure 1. Diagram of the Study Design.

From the synthetic images database, 20 attractive faces are initially selected. In phase 1, the range of lip surface area (SA) was generated and ranked by focus groups to determine the ideal SA. This SA is then used for phase 2, where upper to lower lip ratios are varied to determine the ideal by cardinal ranking. In phase 3, the same ideal SA was used to determine the percentage of the lip SA to the lower facial third.

Development of the Synthetic Image Database

A database of parent images used to generate synthetic images, which are subsequently ranked by attractiveness, was developed and described in our previous studies. Briefly, frontal photographs were obtained from female volunteers 18 to 25 years of age. Each photograph was used as an original parent generation to be morphed with another from the same generation. In each photograph, reference points in the same area were selected. By overlaying each image with corresponding reference points, prominent facial features were outlined, from which an algorithm created a blended 50:50 composite with averaged characteristics. The images were cardinally ranked by attractiveness on a 10-point Likert scale (with 1 indicating the least attractive face and 10 indicating the most attractive face) by our previously described internet-based focus group, establishing an overall attractiveness score for each face. For the present study, 20 photographs were selected from the database. All facial images used were created and presented to raters with approval from the institutional review board at the University of California, Irvine. As only synthetic morphs were used in this research and original photographs were never submitted for facial attractiveness rating, consent to take the photographs was waived by the institutional review board at the University of California, Irvine.

Phase 1: Developing a Set of Lip SA Images

A set of 20 synthetic images that had variable lip SAs and proportions were selected and normalized for size by using interpupillary distance for accurate comparison of linear distances and SAs. Facefilter Studio 2 (Reallusion Inc), an image editing and modification software, was used to manipulate lip dimensions (eg, −50%, +200%, and so on). This augmentation or reduction equally altered the upper and lower lips; therefore, the total SA was changed, but the upper to lower lip ratio was left unchanged. Lip dimensions were reduced or augmented to create a series of 5 modified images per face with varying SAs. Manual adjustment performed with the software involved scaling the lip from the labrale superius to the labrale inferiorus. Adjustments to the labial fissure, or lip width, were not performed because this is not routinely performed in lip augmentation procedures. Reduction and augmentation of lip SA ranged from −200% to 250% from the original; varying degrees of maximum augmentation and minimum reduction were used for each image because of the varying shape of the lips and chosen based on our clinical experience of what appeared naturally or possible with augmentation. To ensure that raters were evaluating changes in lip size, the facial images selected contained features that did not detract focus from the lips. This required selection of images that were the most symmetric and therefore above average in terms of attractiveness from our parent database.

Using the FaceFilter Studio software, increasing or decreasing the SA of each lip by a given percentage did not generate a corresponding quantifiable area other than noting its change from baseline (eg, 0% to 100%). Using a Java-based image-processing program (ImageJ), the vermillion border of the modified lips for the initial, minimum, and maximum modifications were outlined, and the area within the border was measured in pixels to determine the SA. By plotting these 3 SA values (minimum, original, and maximum) as a function of their corresponding percentage adjustment, a trend line was produced and used to determine the intermediate percentages to be used for SA modification. For example, in one image, the initial percentage adjustment was calculated to be 0% (24 341 pixels), the maximum as +200% (36 880 pixels), and the minimum as −200% (16 551 pixels). The intermediates were then graphically measured to be +100% (30 000 pixels) and −100% (20 000 pixels). This method generated a total of 5 images per face, producing 100 images (Figure 2). The vermillion lip was outlined using a graphics tablet (Intuos3, Wacom Co Ltd). Certain facial features, such as the vermillion lip, are not readily recognized by facial recognition software; therefore, tracing required clinical experience and manual expertise, a method we have used in our previous studies.

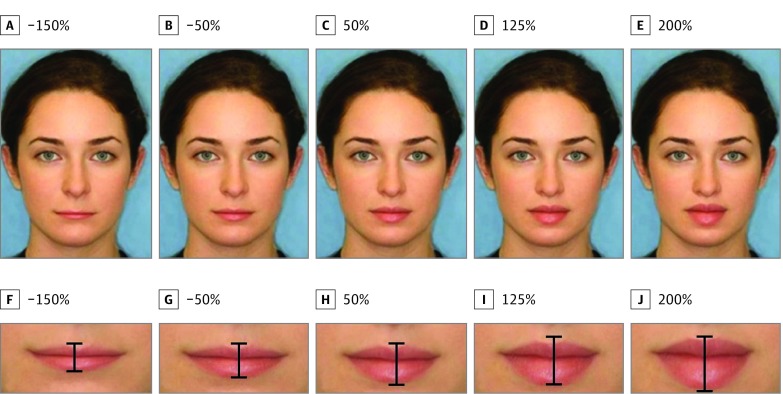

Figure 2. Phase 1: Determining the Most Attractive Surface Area (SA).

Total lip dimensions are manually minimized and enhanced relative to the original SA. A through E, Ratio-altered images as they appeared to raters in the survey; A and F, total lip SA minimized to −150% of the original; B and G, −50%; C and H, 50%; D and I, 125%; and E and J, 200%.

Phase 2: Individual Upper to Lower Lip Ratio

After survey responders ranked images in phase 1 of the study, 15 faces from the original 20 with the most attractive SA were selected for analysis of upper to lower lip ratio. The SAs of the 15 upper and lower lips were calculated using ImageJ and adjusted to fit the most attractive SA obtained in phase 1. With this SA held constant, upper to lower lip ratios of 1:2, 1:3, 1:1, and 2:1 were created, generating 4 images for each face for a total of 60 images (Figure 3). These ratios are representative of a variety of natural lip sizes and current trends in lip augmentation in which the upper lip is often overfilled compared with the lower lip. The adjusted digital composites were cropped at the stomion to include only the upper lip and then recombined with the corresponding lower lip, using the heal and blur features in Adobe C2S Photoshop (Adobe Systems Inc) to minimize artificial sharp demarcations from these combined images. This method was used to make the final lips appear more natural and was not used for reduction or augmentation.

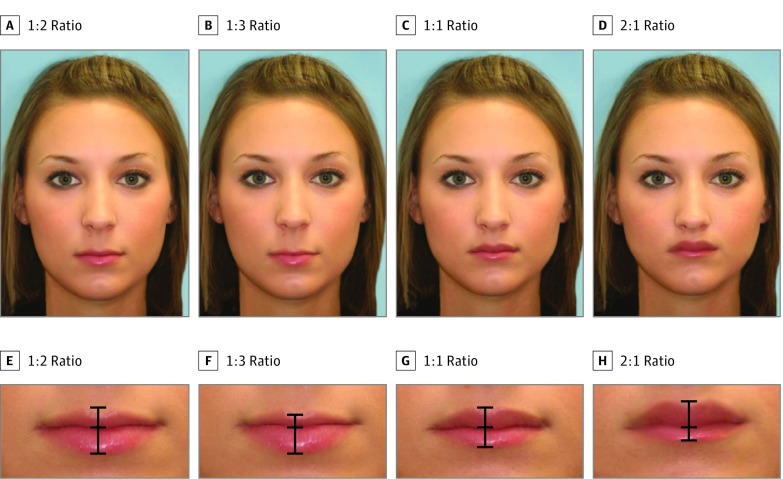

Figure 3. Phase 2: Generating Upper to Lower Lip Ratios.

Lip ratios are adjusted to keep the most attractive surface area constant. A through D, Images as they appeared to raters in the survey; A and E, 1:2 ratio; B and F, 1:3 ratio; C and G, 1:1 ratio; and D and H, 2:1 ratio.

Creating the Surveys and Rating for Attractiveness

The recruitment process was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, Irvine, and effectively used in our prior facial analysis studies. Evaluators were selected using a double-pronged recruitment process that involved a traditional focus group and a virtual focus group created from a social network site (Facebook). By this approach, this study used the initial focus group raters (n = 20) to reach the social network recruits (n = >1000), ensuring a large sample size.

Two online surveys were developed using QuestionPro.com (Survey Analytics LLC) in 2010. In phase 1, participants were presented with the set of 5 images per face of varying SAs and asked to cardinally rank each face for overall facial attractiveness on a 5-point Likert scale (with 1 indicating the least attractive photograph and 5 indicating the most attractive photograph). In phase 3, participants were presented with the set of 4 images per face of varying upper to lower lip ratios and asked to cardinally rank each face for overall facial attractiveness on a 4-point Likert scale. Evaluators were not informed that images were synthetic and were masked to the process of image manipulation. The traditional focus group members participated in both phase 1 and phase 2.

Derivation of Most Attractive SA and Ratio From Surveys

Each face had a mean cardinal rank produced by the facial attractiveness scores evaluated in the survey. For phase 1, a range of 1 × 104 to 4 × 104 pixels was derived for all images from ImageJ tracings. Therefore, the images were initially grouped by the number of pixels into groups by 2.5 × 103-pixel increments. Next, for each image in the group, the mean rank was assigned to each image and the total for that group summed. The group with the highest rank sum was categorized as the most attractive. With the use of ImageJ software, these images were manually analyzed and percentage augmentation from the original calculated by tracing the upper and lower lips. This generated a SA that was used to develop ratios for phase 2.

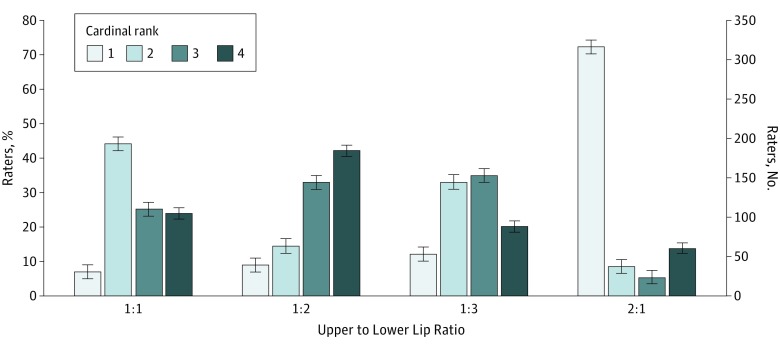

In phase 2, facial attractiveness scores were used to develop a histogram comparing rater vote frequency as a function of cardinal ranking to obtain the most attractive upper to lower lip ratio (Figure 4). This histogram was further statistically analyzed as described below.

Figure 4. Mean Frequency of Attractiveness Ranking Within Each Upper to Lower Lip Ratio.

The ratio of 1:2 had the highest proportion of ranks and generated the highest frequency of votes (180 [42.1%]) within the cardinal rank of 4. Alternatively, the ratio adjustment of 2:1 accumulated the highest frequency of the ratings (310 [72.32%]) within the cardinal ranking of 1 (least attractive). Error bars indicate SD.

Phase 3: SA Compared With Lower Facial Third

As previously noted, all faces were normalized by interpupillary distance before adjustment and analysis. Phase 1 generated a mean attractiveness for each image. The images cardinally ranked as most attractive based on SA were used to calculate the ratio of SA of total vermillion lip to lower third of the face. The lower third of the face, as defined by the neoclassical canons, is measured from the subnasale to the gnathion (menton).

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using PASW Statistics (SPSS Inc). For phase 2, mean ranks for each ratio were calculated, and the rank-based nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to determine a difference between mean attractiveness by rank, using rank as a continuous variable given that images were paired (ie, 4 images are simultaneously shown and ranked). The 2-sided Kruskal-Wallis test was also performed to determine whether there was a statistically significant difference between each ratio pair (1:1 compared with 1:2, 1:1 compared with 1:3, and so on) using the Tukey honestly significant difference test to adjust for multiple comparisons between pairs.

Results

Phase 1: Total Lip SA

All 100 faces were cardinally ranked by 150 individuals (internet-based focus groups [n = 130] and raters from conventional focus groups [conventional raters] [n = 20]), generating an optimal lip SA for every face in phase 1. The SA that corresponded to the range of 2.0 to 2.5 × 104 pixels represented the highest summed rank, generating a pool of 14 images (eFigure in the Supplement). This SA was determined to be the most attractive and corresponded to a 53.5% increase in SA from the original image.

Phase 2: Upper to Lower Lip Ratios and Phase 3: Lip SA to Lower Facial Third

All 60 faces were cardinally ranked by 428 participants (internet-based focus groups [n = 408] and conventional raters [n = 20]), generating a mean attractiveness ranking for each image. The means for each ratio were statistically not equal (Table), and the ratio of 1:2 had the highest mean rank overall at 3.10. Pairwise testing revealed a statistically significant difference among all ratio pairs except 1:1 to 1:3 (P < .001) (Table). A histogram was generated of the proportion of attractiveness ranks within each ratio (Figure 4). The ratio of 1:2 had the highest proportion of ranks within 4 (most attractive) with 180 votes (42.1%), followed by 1:1 (102 votes [23.83%]), 1:3 (86 votes [20.14%]), and 2:1 (59 votes [13.8%]). With the highest mean and highest proportions of most attractive rankings, the 1:2 ratio was deemed most attractive. Conversely, the ratio of 2:1 was deemed least attractive, having both the lowest mean at 1.61 and the highest proportion of ranks within 1 with 310 votes (72.43%). The SA of this ideal lip generated in phase 1 corresponds to a linear dimension equal to 9.6% of the distance of the lower third of the face.

Table. Mean Rank for Upper to Lower Lip Ratios and Pairwise Differences in Ranka.

| Ratio | Mean or Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Rank by Upper to Lower Lip Ratio (n = 6420) | ||

| 1:1 | 2.66 (2.64 to 2.68) | <.001 |

| 1:2 | 3.10 (3.08 to 3.12) | |

| 1:3 | 2.63 (2.61 to 2.66) | |

| 2:1 | 1.61 (1.58 to 1.63) | |

| Pairwise Difference in Ranks for Upper to Lower Lip Ratios | ||

| 1:1 | 1:2 (−0.48 to −0.40) | <.001 |

| 1:1 | 1:3 (−0.01 to 0.07) | .30 |

| 1:1 | 2:1 (1.01 to 1.01) | <.001 |

| 1:2 | 1:3 (0.43 to 0.51) | <.001 |

| 1:2 | 2:1 (1.45 to 1.54) | <.001 |

| 1:3 | 2:1 (0.98 to 1.07) | <.001 |

The mean rank for the 1:2 ratio is the highest among all ratios, and all means are not equal. Pairwise testing reveals a statistical difference among the ranks of all ratios except 1:1 to 1:3.

Discussion

We sought to quantitatively determine the most attractive SA and upper to lower lip ratio in a stepwise fashion using a large sample focus group. We initially quantified the most attractive lip by SA, then used the identified SA to determine the most attractive upper to lower lip ratio, and finally determined the ratio of the lips to the lower facial third. We found that the most attractive faces corresponded to those with an augmentation of the total SA by a mean of 53.5% from baseline and corresponding to 9.6% of the total SA of the lower facial third, with an upper to lower lip ratio of 1:2. Faces that deviated from this ideal SA or ratio were deemed less attractive. Overall, these findings were consistent with the ratio of most natural lips before any augmentation procedure.

We previously developed a novel method for generating synthetic images for analyzing facial attractiveness. Our robust virtual model for ranking facial attractiveness used a combined traditional and internet-based focus group to perform aesthetic analysis. This method has generated a robust set of attractiveness data, allowing for a highly powered statistical analysis compared with all previous studies on focus group evaluation of lip aesthetics.

Several goals exist for lip augmentation, including improving lip fullness, restoring volume in age-associated atrophy, and providing a more distinct vermillion border and philtrum. General guidelines offer the practitioner options for creating an ideal aesthetic but are often based on subjective analysis. Although analysis of lip fullness through morphometric analysis has previously been documented, ideal proportions and dimensions have not been clearly established. Our results indicate a more natural result is viewed as more aesthetically appealing, which provides clinicians with an objective foundation when proceeding with augmentation. We advocate preservation of the natural ratio or achieving a 1:2 ratio in lip augmentation procedures while avoiding the overfilled upper lip look frequently seen among celebrities.

The present study sought to determine attractive ideals for white women, and it is generally accepted that “harmony and disharmony does not lie within angles, distances…or volumes. They arise from proportion.”(p ix) Coleman et al found that, with respect to chin position, fuller lips were preferred in computer-generated retrognathic and prognathia profiles, whereas more retrusive lips were preferred in typical profiles among their focus group. Likewise, it has been previously reported that orthodontia treatment that protudes or retrudes lips is significantly unattractive. Similarly, Penna et al evaluated the ideal lip position with respect to the lower third of the face and found more attractive female lips had a higher ratio of lower vermillion height to chin-mouth distance, increased vermillion height to subnasale stomion, and vermillion height to subnasale menton. This association was observed in both frontal and lateral views. Taken together, fuller lips, when in harmony with the craniofacial skeleton, are generally considered more ideal. Although useful in overall facial analysis, these studies do not provide a quantitative tool for guiding aesthetic augmentation. In the current study, morphed images were overall more attractive in that they were significantly more propitiate than the corresponding parent images. Thus, this method allowed us to determine the most attractive lips given that overall facial proportions were in harmony. As most procedures in facial plastic surgery, it is generally recommended that the ideal lip aesthetic during augmentation should consider the entire face.

As the use of biologic agents for augmentation continues to increase, a validated metric for assessing fullness is necessary to aid in establishing aesthetic goals and allowing for reproducibility. The Medicus Lip Fullness Scale and Lip Fullness Scale are 5-point scales validated by photographic and live evaluation by trained physicians, with good intraobserver and interobserver reliability that may be used to assess fullness. These scales provide a tool to reliably determine whether a patient’s lips should be augmented, providing patients the ability to gauge their augmentation goals. Sawyer et al used 3-dimensional stereophotogrammetry to quantitatively analyze the linear distances, areas, and volumes of healthy untreated volunteers and found significant differences in all measures, with a trend toward larger values in men. In our study, we opted to use cardinal rankings to choose the most attractive face based on changes in lip SA or upper to lower lip ratio because we were assessing overall attractiveness based on changes in lip dimensions and not lip fullness. Future studies should compare focus group attractiveness scores to clinicians’ perceptions to determine whether there is concordance between these groups.

Limitations

Several limitations exist within the scope of our analysis. First, because there is no established reference range for total lip SA modification in the general population, the SA percentage reduction and augmentation extremes from our morphs were generated based on clinical experience of what appeared to be feasible. Second, the use of digital software to generate a range of upper to lower lip ratios, blend the upper and lower lips, and measure total areas lends itself to a degree to subjectivity and bias. Although the vermilion border provides an excellent border for tracing, it is not realistically traced automatically by facial recognition software; therefore, this method introduces a degree of subjectivity that is otherwise unavoidable. Third, we included upper to lower lip ratios that we believe represent what is most commonly seen in natural and filled lips; however, several permutations likely exist in the population that were not tested (ie, 1:1.5, 1:1.8, and so on). Fourth, we were not able to assess interrater reliability with respect to consistently choosing a particular ratio as attractive across all faces.

An additional limitation exists with respect to our survey methods. Although the traditional focus group of 20 individuals solicits more than 2000 participants to complete the survey, dropouts resulted in a total of 578 participants. Dropouts may occur in part because of survey fatigue based on overuse of this population in previous works. Furthermore, the method asked the traditional focus group of undergraduate students to solicit their social network contacts aged 18 to 25 years who were attending a 4-year university for survey; however, demographics could not be confirmed, and experience with fillers or conflicts of interest could not be ascertained, potentially resulting in confounding. Therefore, lack of demographic information also does not allow for screening of exclusion criteria or control of different aesthetic preferences that may exist between men and women. Although this may diminish the scientific rigor of the analysis, a previous study found that 3 traditional focus groups (otolaryngologists, beauticians, and undergraduates) are strongly correlated in assessments of facial attractiveness. The method for soliciting surveyors through social media when compared with a traditional undergraduate focus group also results in strong intergroup correlation. Nevertheless, lack of exclusionary criteria represents a study limitation.

Conclusions

The arbiters of patient preferences in facial aesthetics represent a complex interplay of print, advertisements, and social media. We aimed to provide plastic surgeons with a quantitative means to guide aesthetic parameters in lip augmentation. Using a statistically rigorous process with more than 500 participants in our focus group, we found that an optimum augmentation of 53.5%, an SA representing 9.6% of the lower third of the face, and an upper to lower lip ratio of 1:2 are viewed as most attractive and potentially ideal. Lip dimensions and ratios derived in this study provide guidelines in improving overall facial aesthetics and have clinical relevance to the field of facial plastic surgery.

eFigure. Additive or Ordinal Attractiveness Scores

References

- 1.Agarwal A, Gracely E, Maloney RW. Lip augmentation using sternocleidomastoid muscle and fascia grafts. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2010;12(2):97-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holden PK, Sufyan AS, Perkins SW. Long-term analysis of surgical correction of the senile upper lip. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2011;13(5):332-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Recupero WD, McCollough EG. Comparison of lip enhancement using autologous superficial musculoaponeurotic system tissue and postauricular fascia in conjunction with lip advancement. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2010;12(5):342-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bisson M, Grobbelaar A. The esthetic properties of lips: a comparison of models and nonmodels. Angle Orthod. 2004;74(2):162-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein AW. In search of the perfect lip: 2005. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(11, pt 2):1599-1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.San Miguel Moragas J, Reddy RR, Hernández Alfaro F, Mommaerts MY. Systematic review of “filling” procedures for lip augmentation regarding types of material, outcomes and complications. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015;43(6):883-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lemperle G, Anderson R, Knapp TR. An index for quantitative assessment of lip augmentation. Aesthet Surg J. 2010;30(3):301-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byrne PJ, Hilger PA. Lip augmentation. Facial Plast Surg. 2004;20(1):31-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarnoff DS, Saini R, Gotkin RH. Comparison of filling agents for lip augmentation. Aesthet Surg J. 2008;28(5):556-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richardson MA, Rousso DE, Replogle WH. Long-term analysis of lip augmentation with Superficial Musculoaponeurotic System (SMAS) tissue transfer following biplanar extended SMAS rhytidectomy. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2017;19(1):34-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacono AA, Quatela VC. Quantitative analysis of lip appearance after V-Y lip augmentation. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2004;6(3):172-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carruthers A, Carruthers J, Hardas B, et al. A validated lip fullness grading scale. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34(suppl 2):S161-S166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Werschler WP, Fagien S, Thomas J, Paradkar-Mitragotri D, Rotunda A, Beddingfield FC III. Development and validation of a photographic scale for assessment of lip fullness. Aesthet Surg J. 2015;35(3):294-307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kane MA, Lorenc ZP, Lin X, Smith SR. Validation of a lip fullness scale for assessment of lip augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(5):822e-828e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peck H, Peck S. A concept of facial esthetics. Angle Orthod. 1970;40(4):284-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarnoff DS, Gotkin RH. Six steps to the “perfect” lip. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(9):1081-1088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sawyer AR, See M, Nduka C. 3D stereophotogrammetry quantitative lip analysis. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2009;33(4):497-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Devcic Z, Karimi K, Popenko N, Wong BJ. A web-based method for rating facial attractiveness. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(5):902-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Popenko NA, Devcic Z, Karimi K, Wong BJ. The virtual focus group: a modern methodology for facial attractiveness rating. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(3):455e-461e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong BJ, Karimi K, Devcic Z, McLaren CE, Chen WP. Evolving attractive faces using morphing technology and a genetic algorithm: a new approach to determining ideal facial aesthetics. Laryngoscope. 2008;118(6):962-974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karimi K, Devcic Z, Popenko N, Oyoyo U, Wong BJ. Morphometric facial analysis: a methodology to create lateral facial images. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;19(4):403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farkas LG, Hreczko TA, Kolar JC, Munro IR. Vertical and horizontal proportions of the face in young adult North American Caucasians: revision of neoclassical canons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;75(3):328-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahmed O, Dhinsa A, Popenko N, Osann K, Crumley RL, Wong BJ. Population-based assessment of currently proposed ideals of nasal tip projection and rotation in young women. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2014;16(5):310-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coleman GG, Lindauer SJ, Tüfekçi E, Shroff B, Best AM. Influence of chin prominence on esthetic lip profile preferences. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132(1):36-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Modarai F, Donaldson JC, Naini FB. The influence of lower lip position on the perceived attractiveness of chin prominence. Angle Orthod. 2013;83(5):795-800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Penna V, Fricke A, Iblher N, Eisenhardt SU, Stark GB. The attractive lip: a photomorphometric analysis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015;68(7):920-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi Q, Zheng H, Hu R. Preferences of color and lip position for facial attractiveness by laypersons and orthodontists. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:355-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beer KR. Rejuvenation of the lip with injectables. Skin Therapy Lett. 2007;12(3):5-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farkas LG, Munro IR. Anthropometric Facial Proportions in Medicine. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher Ltd; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sunilkumar LN, Jadhav KS, Nazirkar G, Singh S, Nagmode PS, Ali FM. Assessment of facial golden proportions among North Maharashtrian population. J Int Oral Health. 2013;5(3):48-54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Additive or Ordinal Attractiveness Scores