Key Points

Question

Are statins beneficial when used for primary cardiovascular prevention in older adults?

Findings

In this post hoc secondary analysis of older adults in the randomized clinical trial Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial–Lipid-Lowering Trial (ALLHAT-LLT), there were no significant differences in all-cause mortality or cardiovascular outcomes between pravastatin sodium and usual care for primary prevention for adults 65 years and older.

Meaning

No benefit was found when a statin was given for primary prevention to older adults. Treatment recommendations should be individualized for this population.

Abstract

Importance

While statin therapy for primary cardiovascular prevention has been associated with reductions in cardiovascular morbidity, the effect on all-cause mortality has been variable. There is little evidence to guide the use of statins for primary prevention in adults 75 years and older.

Objectives

To examine statin treatment among adults aged 65 to 74 years and 75 years and older when used for primary prevention in the Lipid-Lowering Trial (LLT) component of the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT-LLT).

Design, Setting, and Participants

Post hoc secondary data analyses were conducted of participants 65 years and older without evidence of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; 2867 ambulatory adults with hypertension and without baseline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease were included. The ALLHAT-LLT was conducted from February 1994 to March 2002 at 513 clinical sites.

Interventions

Pravastatin sodium (40 mg/d) vs usual care (UC).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome in the ALLHAT-LLT was all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes included cause-specific mortality and nonfatal myocardial infarction or fatal coronary heart disease combined (coronary heart disease events).

Results

There were 1467 participants (mean [SD] age, 71.3 [5.2] years) in the pravastatin group (48.0% [n = 704] female) and 1400 participants (mean [SD] age, 71.2 [5.2] years) in the UC group (50.8% [n = 711] female). The baseline mean (SD) low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels were 147.7 (19.8) mg/dL in the pravastatin group and 147.6 (19.4) mg/dL in the UC group; by year 6, the mean (SD) low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels were 109.1 (35.4) mg/dL in the pravastatin group and 128.8 (27.5) mg/dL in the UC group. At year 6, of the participants assigned to pravastatin, 42 of 253 (16.6%) were not taking any statin; 71.0% in the UC group were not taking any statin. The hazard ratios for all-cause mortality in the pravastatin group vs the UC group were 1.18 (95% CI, 0.97-1.42; P = .09) for all adults 65 years and older, 1.08 (95% CI, 0.85-1.37; P = .55) for adults aged 65 to 74 years, and 1.34 (95% CI, 0.98-1.84; P = .07) for adults 75 years and older. Coronary heart disease event rates were not significantly different among the groups. In multivariable regression, the results remained nonsignificant, and there was no significant interaction between treatment group and age.

Conclusions and Relevance

No benefit was found when pravastatin was given for primary prevention to older adults with moderate hyperlipidemia and hypertension, and a nonsignificant direction toward increased all-cause mortality with pravastatin was observed among adults 75 years and older.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00000542

This post hoc secondary analysis of older adults in the randomized clinical trial ALLHAT-LLT compares statin treatment vs usual care for primary cardiovascular prevention.

Introduction

The number of older adults in the United States is increasing rapidly. According to the US Census Bureau, there are approximately 6 million people in the United States 85 years and older, and this group is expected to be 9 million by 2030. Many older patients take statins for primary cardiovascular prevention. In a study at the Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvania, 28% of patients aged 75 to 79 years and 22% of patients 80 years and older were taking a statin for primary prevention. Another study that analyzed the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey found that statin use for primary prevention for adults older than 79 years increased from 8.8% in 1999-2000 to 34.1% in 2011-2012. While there is some evidence of benefit to secondary prevention with statins among older adults, data are limited on the risks and benefits of statins for primary prevention in this age group. Improving our understanding of preventive interventions in patients 75 years and older has many implications for health care and its costs.

Until recently, decisions to initiate statins for primary prevention in patients were based largely on cardiovascular risk models developed from the Framingham Heart Study. This risk score has been demonstrated to be inaccurate in predicting cardiovascular events among the oldest adults (≥85 years). Elevated lipid levels are less predictive of cardiovascular risk with increasing age, and low lipid levels in the oldest adults usually correlate with increased mortality. Furthermore, the 2013 guideline from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association emphasized that “Few data were available to indicate an atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) event reduction benefit in primary prevention among individuals >75 years of age who do not have clinical ASCVD,”(pS24) and the risk calculator developed has a cutoff age of 79 years. However, these guidelines imply a disproportionate risk based on age, and there is controversy about overestimating risk among older adults. The recently published US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines of statin use for primary prevention also highlight the lack of evidence for its use in older adults (especially for adults ≥76 years). In addition, these guidelines raised many controversies regarding the evidence of statin use for primary prevention in asymptomatic adults, particularly for older adults.

Statins for primary prevention have been associated with some reductions in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) morbidity for older adults in some large clinical trials, while not in another trial, and most studies do not show an effect on all-cause mortality. Given the conflicting evidence, particularly for adults 75 years and older, there are several reasons to think that there may be heterogeneity of the effects of statins when used for primary prevention in older age groups. A recent Markov modeling study found that statins for primary prevention for adults 75 years and older would be cost-effective in preventing cardiovascular-related events (including coronary heart disease [CHD], stroke, revascularization procedures, and death). However, the authors noted that “even a small increase in geriatric-specific adverse effects could offset the cardiovascular benefit.”(p533) Despite the potential benefit of statins for primary cardiovascular prevention, even small adverse effects in older adults could lead to harm and may explain the inconsistent data on all-cause mortality. However, owing to the low proportion of older adults enrolled in clinical trials, it is difficult to fully understand the risks and benefits of statins for primary prevention in this population compared with younger adults. The objective of this study was to conduct secondary data analyses of several important outcomes of a large subset of older adults without baseline ASCVD from the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial–Lipid-Lowering Trial (ALLHAT-LLT) to evaluate the overall benefit for older adults.

Methods

We performed a subanalysis of the LLT component of the ALLHAT. The design of the ALLHAT has been previously described. Briefly, the ALLHAT-LLT, sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health, was a randomized, open-label trial conducted from February 1994 to March 2002 at 513 clinical sites. All participants of the ALLHAT-LLT were drawn exclusively from the parent trial, ALLHAT, which was an antihypertensive trial designed to determine if treatment with a calcium channel blocker, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, or an α-blocker reduces fatal CHD or nonfatal myocardial infarction compared with treatment with a thiazide-type diuretic. Details regarding sample size, recruitment, and randomization have been published elsewhere. Access to the full protocol may be found at http://www.ALLHAT.org. The trial protocol for the ALLHAT-LLT is available in Supplement 1. The institutional review board of The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston approved the secondary data analysis.

Study Population

Eligibility for the ALLHAT-LLT included ambulatory adults 55 years and older having stage 1 or 2 hypertension with at least one additional CHD risk factor, randomized to 1 of 4 antihypertensive drugs. Participants for the ALLHAT-LLT were excluded if they were currently receiving lipid-lowering therapy, were known to be intolerant of statins, manifested significant liver or kidney disease, or had a known secondary cause of hyperlipidemia. For individuals without known CHD, a fasting low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level of 120 to 189 mg/dL and a fasting triglycerides level lower than 350 mg/dL were required (to convert cholesterol level to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259; to convert triglycerides level to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0113). Ultimately, 10 355 adults were enrolled in the ALLHAT-LLT. Among the participants of the ALLHAT-LLT, we performed a subanalysis only of those individuals who were 65 years and older and without evidence of ASCVD (CHD, peripheral vascular disease, and cerebrovascular disease) at baseline. The full ASCVD criteria are listed in eTable 1 in Supplement 2.

Treatment

The intervention for the ALLHAT-LLT was open-label pravastatin sodium (40 mg/d) vs usual care (UC), and participants were randomly assigned to the 2 groups in a ratio of 1:1. Initially, participants in the pravastatin group began with a pravastatin sodium dosage of 20 mg/d and increased to 40 mg/d as needed to achieve a 25% decrease in LDL-C level; however, after the first 1000 participants enrolled in the study, a constant dosage of 40 mg/d was adopted for all participants in the pravastatin group. Study practitioners had the option to lower the dosage, discontinue treatment with pravastatin due to adverse effects, and prescribe other cholesterol-lowering drugs. The UC group was treated for LDL-C level lowering based on the discretion of their primary care physician.

Follow-up

Follow-up visits were done at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after antihypertensive trial randomization and every 4 months thereafter. Along with determination of the fasting total cholesterol level and questions about intervening events, at the 2-year, 4-year, and 6-year follow-up visits, a fasting lipid profile was obtained in random preselected samples of UC (5%) and pravastatin (10%) participants (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

Outcomes

The primary outcome in the ALLHAT-LLT was all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes included cause-specific mortality and nonfatal myocardial infarction or fatal CHD combined (CHD events). Study end points were ascertained at follow-up visits or by death certificates for all deaths and hospital discharge summaries for each hospitalized study event. Further details of the event ascertainment process are published elsewhere.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed during the entire study period of the trial with follow-up according to participants’ randomized treatment assignments regardless of subsequent crossover (intent-to-treat analysis). Characteristics of participants included in this analysis were calculated by age range and participants’ randomized treatment assignments, with statistical significance of differences determined using t tests or χ2 tests as appropriate. The cumulative event rates for each outcome by age range were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. A participant’s duration in the study started at randomization to the ALLHAT-LLT and ended at the date of last known follow-up or death. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to evaluate differences between event rate curves and provide hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs. A multivariable-adjusted model was constructed to give HRs that included the following predefined cardiac risks factors: baseline age, sex, black race/ethnicity, aspirin use (for primary prevention), current cigarette smoker, the presence of type 2 diabetes, body mass index, and systolic and diastolic blood pressures. We conducted sensitivity analyses testing the interaction between treatment group and age to assess if the treatment effect differed between adults 75 years and older and those younger than 75 years. For all analyses, a 2-tailed P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical software (Stata, version 14; StataCorp LP) was used for all analyses.

Results

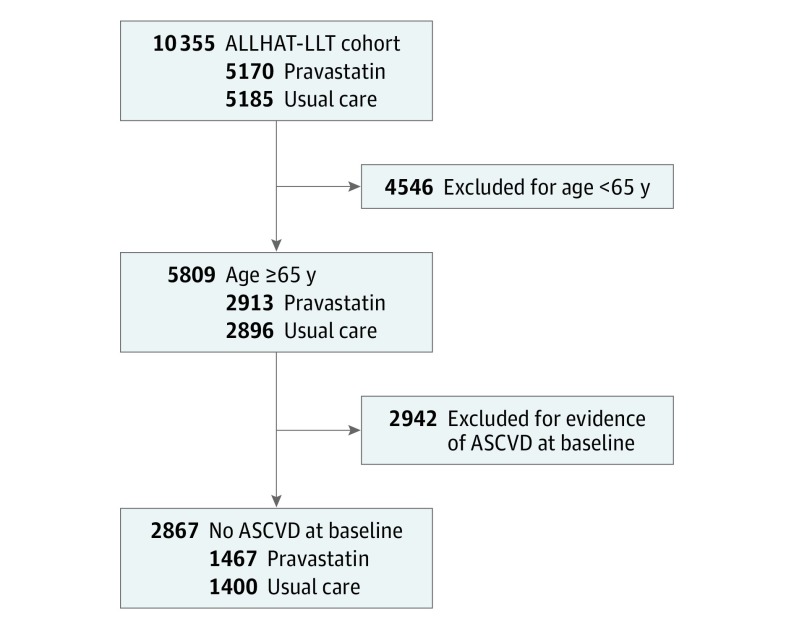

Among the 10 355 participants in the ALLHAT-LLT, 4546 were excluded owing to age younger than 65 years, and an additional 2942 participants with ASCVD at baseline were excluded (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). The analytical sample was 2867 ambulatory adults 65 years and older with hypertension and without ASCVD at baseline (Figure 1). There were 1467 participants in the pravastatin group and 1400 participants in the UC group. The baseline characteristics, including serum lipid levels stratified by age group (65-74 years and ≥75 years) and by treatment group (pravastatin vs UC), are listed in Table 1. In participants aged 65 to 74 years, the mean years of follow-up differed significantly for pravastatin (4.63 years) vs UC (4.77 years) (P = .04). Losses to follow-up in the ALLHAT-LLT are discussed elsewhere. Among participants 75 years and older, 86.7% (325 of 375) of the pravastatin group were taking antihypertensive medications vs 92.9% (326 of 351) of the UC group (P = .01), and the mean systolic blood pressures were 150.6 mm Hg in the pravastatin group and 147.5 mm Hg in the UC group (P = .01).

Figure 1. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials Diagram.

Shown is the selection of study participants from the overall Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial–Lipid-Lowering Trial (ALLHAT-LLT) randomized to receive pravastatin sodium vs usual care. ASCVD indicates atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the ALLHAT-LLT Participants by Treatment Group (Pravastatin vs Usual Care) and Age Group.

| Characteristic | 65-74 y | ≥75 y | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pravastatin Sodium | Usual Care | P Value | Pravastatin | Usual Care | P Value | Pravastatin | Usual Care | P Value | |

| No. | 1092 | 1049 | NA | 375 | 351 | NA | 1467 | 1400 | NA |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 68.8 (2.7) | 68.8 (2.8) | .61 | 78.5 (3.6) | 78.6 (3.6) | .86 | 71.3 (5.2) | 71.2 (5.2) | .68 |

| Female, No. (%) | 490 (44.9) | 513 (48.9) | .06 | 214 (57.1) | 198 (56.4) | .86 | 704 (48.0) | 711 (50.8) | .13 |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | |||||||||

| White non-Hispanic | 436 (39.9) | 419 (39.9) | .21 | 145 (38.7) | 136 (38.7) | .87 | 581 (39.6) | 555 (39.6) | .63 |

| Black non-Hispanic | 387 (35.4) | 363 (34.6) | 121 (32.3) | 115 (32.8) | 508 (34.6) | 478 (34.1) | |||

| White Hispanic | 167 (15.3) | 190 (18.1) | 78 (20.8) | 67 (19.1) | 245 (16.7) | 257 (18.4) | |||

| Black Hispanic | 47 (4.3) | 31 (3.0) | 11 (2.9) | 14 (4.0) | 58 (4.0) | 45 (3.2) | |||

| Other | 55 (5.0) | 46 (4.4) | 20 (5.3) | 19 (5.4) | 75 (5.1) | 65 (4.6) | |||

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 10.5 (4.4) | 10.6 (4.1) | .72 | 9.3 (4.3) | 9.2 (4.5) | .79 | 10.2 (4.4) | 10.3 (4.3) | .86 |

| Medication use, No./total No. (%) | |||||||||

| Women taking estrogen | 59/490 (12.0) | 60/513 (11.7) | .87 | 15/214 (7.0) | 11/198 (5.6) | .54 | 74/704 (10.5) | 71/711 (10.0) | .75 |

| Aspirin | 276/1092 (25.3) | 254/1049 (24.2) | .57 | 98/375 (26.1) | 100/351 (28.5) | .48 | 374/1467 (25.5) | 354/1400 (25.3) | .90 |

| Antihypertensive medication | 994/1092 (91.0) | 948/1049 (90.4) | .60 | 325/375 (86.7) | 326/351 (92.9) | .01 | 1319/1467 (89.9) | 1274/1400 (91.0) | .32 |

| Current cigarette smoking, No. (%) | 290 (26.6) | 247 (23.5) | .11 | 51 (13.6) | 53 (15.1) | .56 | 341 (23.2) | 300 (21.4) | .24 |

| Type 2 diabetes, No. (%) | 552 (50.5) | 544 (51.9) | .55 | 196 (52.3) | 171 (48.7) | .34 | 748 (51.0) | 715 (51.1) | .97 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 29.9 (5.9) | 30.0 (5.9) | .79 | 28.4 (5.4) | 28.2 (5.1) | .55 | 29.5 (5.8) | 29.5 (5.8) | .99 |

| >30, No. (%) | 476 (43.6) | 441 (42.0) | .45 | 123 (32.8) | 109 (31.1) | .62 | 599 (40.8) | 550 (39.3) | .38 |

| Blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | |||||||||

| Systolic | 146.9 (15.3) | 146.9 (15.3) | .95 | 150.6 (15.0) | 147.5 (16.1) | .01 | 147.8 (15.3) | 147.1 (15.5) | .19 |

| Diastolic | 84.0 (9.5) | 83.9 (10.1) | .92 | 82.1 (11.2) | 82.0 (9.7) | .88 | 83.5 (10.0) | 83.4 (10.0) | .88 |

| Fasting glucose, mean (SD), mg/dL | 132.1 (60.2) | 128.5 (57.2) | .21 | 127.4 (61.6) | 127.9 (61.8) | .92 | 130.9 (60.5) | 128.4 (58.4) | .30 |

| Lipid values | |||||||||

| Serum cholesterol, mean (SD), mg/dL | 225.5 (25.5) | 225.8 (24.6) | .81 | 225.1 (23.8) | 225.7 (26.2) | .74 | 225.4 (25.1) | 225.8 (25.0) | .70 |

| LDL-C, mean (SD), mg/dL | 148.0 (20.4) | 147.9 (19.3) | .90 | 146.6 (18.1) | 146.8 (19.7) | .93 | 147.7 (19.8) | 147.6 (19.4) | .95 |

| LDL-C <130 mg/dL, No. (%) | 243 (22.3) | 201 (19.2) | .09 | 64 (17.1) | 73 (20.8) | .21 | 307 (20.9) | 274 (19.6) | .40 |

| HDL-C, mean (SD), mg/dL | 46.7 (12.8) | 47.1 (13.8) | .47 | 48.8 (13.9) | 50.2 (14.3) | .17 | 47.2 (13.1) | 47.9 (14.0) | .19 |

| Fasting triglycerides, mean (SD), mg/dL | 152.0 (66.5) | 151.3 (70.2) | .82 | 145.0 (62.4) | 142.3 (66.5) | .60 | 150.3 (65.6) | 149.0 (69.3) | .63 |

| Antihypertensive randomization, No. (%)a | |||||||||

| Chlorthalidone | 376 (34.4) | 379 (36.1) | .72 | 150 (40.0) | 128 (36.5) | .69 | 526 (35.9) | 507 (36.2) | .98 |

| Amlodipine | 242 (22.2) | 239 (22.8) | 90 (24.0) | 82 (23.4) | 332 (22.6) | 321 (22.9) | |||

| Lisinopril | 241 (22.1) | 214 (20.4) | 65 (17.3) | 69 (19.7) | 306 (20.9) | 283 (20.2) | |||

| Doxazosin | 233 (21.3) | 217 (20.7) | 70 (18.7) | 72 (20.5) | 303 (20.7) | 289 (20.6) | |||

| Years of follow-up, mean (SD) [maximum] | 4.63 (1.59) [7.78] | 4.77 (1.57) [7.83] | .04 | 4.32 (1.62) [7.39] | 4.32 (1.58) [7.20] | .99 | 4.55 (1.60) [7.78] | 4.66 (1.58) [7.83] | .08 |

Abbreviations: ALLHAT-LLT, Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial–Lipid-Lowering Trial; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; NA, not applicable.

SI conversion factors: To convert cholesterol levels to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259; glucose level to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0555; and triglycerides level to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0113.

The ALLHAT randomization for chlorthalidone, amlodipine, lisinopril, and doxazosin mesylate was conducted in a ratio of 1.7:1:1:1.

Of the individuals assigned to pravastatin, 86.1% (1070 of 1243) were taking it at year 2 and 77.9% (197 of 253) at year 6 (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). In the UC group, 8.3% (96 of 1155) of participants were taking a statin by year 2 and 29.0% (77 of 266) by year 6. The rate of crossover to statin treatment in the UC group was more pronounced for participants aged 65 to 74 years compared with those 75 years and older. For participants aged 65 to 74 years in the UC group, 31.8% (70 of 220) were taking a statin by year 6; for those 75 years and older, only 15.2% (7 of 46) were taking a statin by year 6. Total cholesterol and LDL-C levels were lower at the 2-year, 4-year, and 6-year follow-up visits in the pravastatin group compared with the UC group across all age groups (eTable 3 in Supplement 2). The mean (SD) baseline LDL-C levels were 147.7 (19.8) mg/dL in the pravastatin group and 147.6 (19.4) mg/dL in UC group; by year 6, the mean (SD) LDL-C levels were 109.1 (35.4) mg/dL in the pravastatin group and 128.8 (27.5) mg/dL in the UC group. The ALLHAT-LLT ended in March 2002 as scheduled. Approximately half of those discontinuing pravastatin therapy did so without citing a reason, while the remainder cited adverse effects and other medical and nonmedical reasons. Specific adverse effects data were not collected.

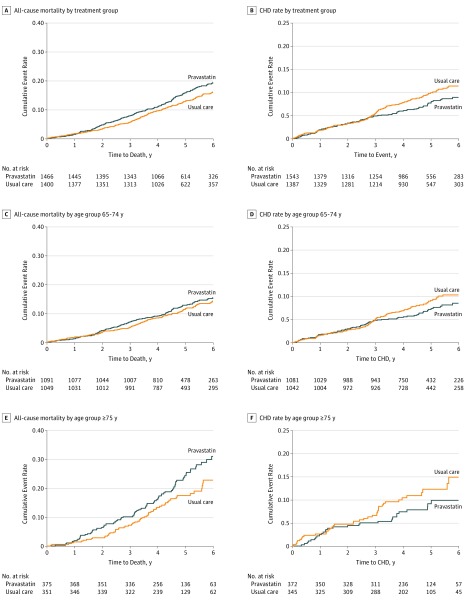

There was no benefit of pravastatin for any of the primary and secondary outcomes (Table 2 and Figure 2). For the primary outcome, all-cause mortality, more deaths occurred in the pravastatin group compared with the UC group in both age groups (Table 2). For participants aged 65 to 74 years, there were 141 deaths in the pravastatin group and 130 deaths in the UC group (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.85-1.37; P = .55). For participants 75 years and older, there was a nonsignificant increase in mortality in the pravastatin group, with 92 deaths vs 65 deaths in the UC group (HR, 1.34; 95% CI, 0.98-1.84; P = .07).

Table 2. Six-Year Incidence Rates for Primary and Secondary Outcomes in the ALLHAT-LLT, Cumulative Events, and Relative Risks Based on the Entire Follow-up by Age Group.

| Outcome | Cumulative Events | 6-y Incidence Rate (SE) per 100 Participants | Pravastatin vs Usual Care | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pravastatin Sodium | Usual Care | Pravastatin | Usual Care | HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| All-cause mortality | 233 | 195 | 19.4 (1.3) | 16.2 (1.2) | 1.18 (0.97-1.42) | .09 |

| 65-74 y | 141 | 130 | 15.5 (1.3) | 14.2 (1.3) | 1.08 (0.85-1.37) | .55 |

| ≥75 y | 92 | 65 | 31.0 (3.2) | 22.7 (3.0) | 1.34 (0.98-1.84) | .07 |

| CVD deaths | 101 | 87 | 8.2 (0.9) | 7.5 (0.9) | 1.14 (0.86-1.52) | .36 |

| 65-74 y | 64 | 62 | 7.2 (1.0) | 6.8 (0.9) | 1.02 (0.72-1.45) | .91 |

| ≥75 y | 37 | 25 | 11.2 (2.1) | 10.1 (2.3) | 1.39 (0.84-2.32) | .20 |

| CHD deaths | 49 | 50 | 4.0 (0.6) | 4.2 (0.7) | 0.97 (0.65-1.44) | .87 |

| 65-74 y | 33 | 35 | 3.9 (0.8) | 3.7 (0.7) | 0.94 (0.58-1.51) | .79 |

| ≥75 y | 16 | 15 | 4.1 (1.1) | 6.0 (1.8) | 0.99 (0.49-2.00) | .97 |

| Stroke deaths | 18 | 13 | 1.3 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.36 (0.67-2.78) | .40 |

| 65-74 y | 11 | 10 | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.1 (0.4) | 1.08 (0.46-2.54) | .87 |

| ≥75 y | 7 | 3 | 1.4 (0.6) | 1.8 (1.2) | 2.27 (0.59-8.79) | .23 |

| Non-CVD deaths | 117 | 95 | 10.8 (1.1) | 8.4 (1.0) | 1.21 (0.93-1.59) | .16 |

| 65-74 y | 72 | 61 | 8.5 (1.1) | 7.2 (1.0) | 1.17 (0.83-1.65) | .36 |

| ≥75 y | 45 | 34 | 18.3 (2.8) | 12.2 (2.4) | 1.26 (0.81-1.97) | .31 |

| Cause of death unknown | 15 | 13 | 1.6 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.14 (0.54-2.39) | .73 |

| 65-74 y | 5 | 7 | 0.6 (0.3) | 0.8 (0.4) | 0.72 (0.23-2.26) | .57 |

| ≥75 y | 10 | 6 | 4.9 (1.7) | 2.1 (0.8) | 1.58 (0.57-4.35) | .38 |

| Fatal CHD and nonfatal MIa | 107 | 128 | 8.8 (0.9) | 11.3 (1.0) | 0.81 (0.63-1.05) | .12 |

| 65-74 y | 76 | 89 | 8.4 (1.1) | 10.2 (1.1) | 0.85 (0.62-1.15) | .29 |

| ≥75 y | 31 | 39 | 9.9 (1.9) | 14.9 (2.7) | 0.70 (0.43-1.13) | .14 |

| Stroke, fatal and nonfatal | 71 | 65 | 6.2 (0.8) | 5.8 (0.8) | 1.06 (0.76-1.49) | .72 |

| 65-74 y | 44 | 42 | 5.2 (0.9) | 4.7 (0.8) | 1.03 (0.68-1.57) | .89 |

| ≥75 y | 27 | 23 | 9.0 (1.9) | 9.6 (2.4) | 1.09 (0.63-1.90) | .76 |

| Heart failure, hospitalized or fatal | 79 | 78 | 7.1 (0.9) | 7.7 (0.9) | 1.00 (0.73-1.36) | .98 |

| 65-74 y | 53 | 53 | 6.5 (1.0) | 7.1 (1.1) | 1.01 (0.69-1.47) | .98 |

| ≥75 y | 26 | 25 | 8.9 (1.9) | 9.1 (1.9) | 0.97 (0.56-1.68) | .91 |

| Cancer, fatal and nonfatal | 131 | 113 | 11.4 (1.1) | 10.0 (1.0) | 1.14 (0.88-1.46) | .32 |

| 65-74 y | 105 | 87 | 11.7 (1.2) | 10.2 (1.2) | 1.20 (0.90-1.60) | .21 |

| ≥75 y | 26 | 26 | 10.6 (2.2) | 9.0 (2.0) | 0.93 (0.54-1.59) | .78 |

Abbreviations: ALLHAT-LLT, Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial–Lipid-Lowering Trial; CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HR, hazard ratio for pravastatin sodium vs usual care; MI, myocardial infarction.

Fatal CHD events were ascertained by clinic report or by match with national databases (see the Outcomes subsection of the Methods section) plus a confirmatory death certificate. Hospitalized outcomes, such as nonfatal MIs, were primarily based on clinic investigator reports for which supporting copies of death certificates and hospital discharge summaries were requested. Clinical trials center medical reviewers verified the clinician-assigned diagnoses of outcomes. More detailed information was collected on a random 10% subset of CHD events to validate the procedure of using clinician diagnoses.

Figure 2. All-Cause Mortality and Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) Deaths Plus Nonfatal Myocardial Infarction by Treatment Group (Pravastatin vs Usual Care) and Age.

A, C, and E, Shown is all-cause mortality by treatment group and age group. B, D, and F, Shown are CHD deaths plus nonfatal myocardial infarction by treatment group and age group. The hazard ratios (95% CIs) are listed in Table 2. Pravastatin was given as pravastatin sodium.

There were 76 CHD events in the pravastatin group and 89 CHD events in the UC group for adults aged 65 to 74 years (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.62-1.15; P = .29), and there were 31 CHD events in the pravastatin group and 39 CHD events in the UC group for adults 75 years and older (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.43-1.13; P = .14) (Table 2). Stroke, heart failure, and cancer rates were similar in the 2 treatment groups for both age groups.

In multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression, the adjusted HR (pravastatin vs UC) for all-cause mortality for all participants 65 years and older was 1.15 (95% CI, 0.94-1.39; P = .17) (Table 3). In the age group 65 to 74 years, the HR was 1.05 (95% CI, 0.82-1.33); for the age group 75 years and older, the HR was 1.36 (95% CI, 0.98-1.89) (P = .24 for interaction). Multivariable regression for CHD events adjusting for the same cardiovascular risk factors did not significantly change the risk across all age groups, and there was no significant interaction between treatment group and age (eTable 4A and eTable 4B in Supplement 2).

Table 3. Multivariable Regression for All-Cause Mortality by Age Group and for Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) Events by Age Group.

| Variable | 65-74 y | ≥75 y | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Multivariable Regression for All-Cause Mortality by Age Group | ||||||

| Pravastatin | 1.05 (0.82-1.33) | .72 | 1.36 (0.98-1.89) | .06 | 1.15 (0.94-1.39) | .17 |

| Age | 1.06 (1.01-1.10) | .01 | 1.11 (1.06-1.15) | <.01 | 1.08 (1.06-1.10) | <.01 |

| Female | 0.83 (0.65-1.07) | .16 | 0.53 (0.38-0.74) | <.01 | 0.71 (0.58-0.87) | <.01 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | .01 | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | .11 | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | <.01 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 0.99 (0.98-1.01) | .37 | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) | .90 | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | .52 |

| Aspirin use | 1.03 (0.77-1.36) | .86 | 0.86 (0.59-1.24) | .42 | 0.97 (0.77-1.21) | .78 |

| Body mass index | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) | .90 | 0.99 (0.95-1.02) | .44 | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) | .98 |

| Black race/ethnicity | 1.04 (0.81-1.33) | .76 | 1.15 (0.82-1.60) | .41 | 1.08 (0.88-1.31) | .47 |

| Current cigarette smoker | 1.90 (1.43-2.53) | <.01 | 1.49 (0.91-2.45) | .11 | 1.75 (1.37-2.24) | <.01 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 1.74 (1.32-2.29) | <.01 | 1.66 (1.17-2.35) | <.01 | 1.66 (1.34-2.05) | <.01 |

| Multivariable Regression for CHD Events by Age Group | ||||||

| Pravastatin | 0.85 (0.63-1.16) | .31 | 0.70 (0.42-1.15) | .16 | 0.80 (0.62-1.04) | .09 |

| Age | 1.02 (0.96-1.08) | .48 | 1.05 (0.99-1.12) | .13 | 1.03 (1.01-1.06) | .01 |

| Female | 0.77 (0.56-1.06) | .11 | 0.46 (0.27-0.77) | <.01 | 0.65 (0.50-0.86) | <.01 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | .06 | 1.01 (0.99-1.02) | .51 | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | .06 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) | .75 | 1.00 (0.98-1.03) | .86 | 1.00 (0.98-1.01) | .83 |

| Aspirin use | 1.05 (0.73-1.49) | .80 | 1.52 (0.92-2.51) | .11 | 1.21 (0.91-1.61) | .20 |

| Body mass index | 1.00 (0.97-1.02) | .75 | 0.95 (0.90-1.01) | .10 | 0.99 (0.96-1.01) | .29 |

| Black race/ethnicity | 0.93 (0.68-1.28) | .66 | 0.79 (0.46-1.35) | .39 | 0.89 (0.68-1.17) | .40 |

| Current cigarette smoker | 1.49 (1.02-2.17) | .04 | 0.95 (0.41-2.16) | .89 | 1.31 (0.93-1.84) | .13 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 2.13 (1.49-3.04) | <.01 | 1.30 (0.78-2.18) | .32 | 1.80 (1.35-2.40) | <.01 |

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio for pravastatin sodium vs usual care.

Discussion

Our study found that newly administered statin use for primary prevention had no benefit on all-cause mortality or CHD events compared with UC in the subset of adults 65 years and older with hypertension and moderate hypercholesterolemia in the ALLHAT-LLT. We noted a nonsignificant direction toward increased all-cause mortality with the use of pravastatin in the age group 75 years and older, but there was no significant interaction between treatment group and age. The use of statins may be producing untoward effects in the function or health of older adults that could offset any possible cardiovascular benefit.

Statins may have an effect on the physical or mental functioning of older adults, and studies have shown that any negative effect on function places older adults at higher risk for functional decline and death. Older adults are at increased risk for statin-induced muscle problems; the risk of hospitalization for rhabdomyolysis in patients 65 years and older is more than 5 times higher than that in younger adults. It has also been suggested that statins have negative effects on energy and fatigue with exertion. Therefore, it is possible that, for vulnerable older adults, statins may have negative effects on function. Evidence has suggested that statin use may have negative effects on cognition, particularly in adults with mild cognitive impairment or dementia. However, a recent major review of the efficacy and safety of statins using trial data found no effect of statins on incident dementia or on cognitive function. However, that study fails to acknowledge that current trial data do not include many people 80 years and older or older frail adults; other individual trials were underpowered to identify the harms of statin therapy.

Observational studies from around the world have shown mixed findings regarding the benefit of statins for primary prevention in older adults. The only large lipid treatment clinical study specifically targeting older adults was the Prospective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk (PROSPER). Among the participants in the PROSPER without vascular disease at baseline (ie, primary prevention) (n = 3239), the use of pravastatin did not result in significant reductions in CHD or stroke events during a mean 3.2-year follow-up. If one subtracts from the all-cause mortality data of PROSPER with the specific results of mortality of older patients with CHD published by Afilalo et al, the mortality rate in the PROSPER in participants without CHD at baseline was 8.8% in those receiving placebo vs 9.6% in those receiving statin therapy.

The other major randomized trial that had a large proportion of older individuals, the Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin (JUPITER), included 5695 individuals 70 years and older with no cardiovascular disease at baseline but with a high-sensitivity C-reactive protein level of 2 mg/L or more (to convert C-reactive protein level to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 9.524). A secondary analysis of participants 70 years and older in the JUPITER study found all-cause mortality of 1.63 per 100 person-years in those receiving rosuvastatin and 2.04 per 100 person-years in those receiving placebo, a difference that was not statistically significant (P = .09). The JUPITER study has come under criticism pertaining to the early termination of the trial and strong commercial conflicts of interest.

The recently published results from the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE)-3 study have garnered support for the broader use of statins for primary prevention in intermediate-risk populations. HOPE-3 enrolled men 55 years and older and women 65 years and older who had at least one cardiovascular risk factor or women 60 years and older with 2 risk factors, all without a diagnosis of ASCVD. Participants were randomized to rosuvastatin (mean age, 65.8 years) or placebo (mean age, 65.7 years). At a median follow-up of 5.6 years, the first coprimary outcome (a composite of death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal stroke, or nonfatal myocardial infarction) occurred significantly less frequently with rosuvastatin than with placebo (3.7% vs 4.8%). There was no difference in death from any cause between the rosuvastatin group and the placebo group (5.3% vs 5.6%). While HOPE-3 appears to show benefit of statins for primary prevention for cardiovascular outcomes among a younger population of older adults, there was no benefit for all-cause mortality, although this measure was not a primary or secondary outcome. Stratification by age 65.3 years and younger vs older than 65.3 years gave similar estimates, but further analysis of the subgroup of older adults (particularly those ≥75 years) in HOPE-3 is needed.

Strengths and Limitations

A major strength of this study is its large population of high-risk older adults. The findings of the recent Markov modeling study evaluating the use of statins for primary prevention in adults aged 75 to 94 years suggested that, if statins had no effect on functional limitation or cognitive impairment, primary prevention strategies would prevent CHD and would also be cost-effective. However, the ALLHAT-LLT data suggest that, while there may be a trend toward cardiovascular benefit, there was no all-cause mortality benefit of statins for adults 65 years and older. More studies that address cardiovascular and noncardiovascular outcomes are needed to better understand the risks and benefits of statin therapy for primary prevention in older adults, particularly for those 75 years and older.

The following limitations should be noted in our study that should give caution when interpreting our findings. This study is a post hoc secondary analysis of the ALLHAT-LLT of a subgroup of participants. Another limitation is that an exclusion criterion for enrollment in the ALLHAT-LLT was current use of lipid-lowering therapy at baseline. The risk-benefit ratio of statin therapy in patients who were started on treatment with statins at a younger age may be different from that among those 75 years and older in whom one is considering initiating treatment with statins, and our study was unable to address this risk. An additional limitation is the lack of specific adverse effects data collected during the study, and such data could have given a better understanding of the risks and benefits of statin therapy. Another major limitation is that our subpopulation of older adults in the ALLHAT-LLT lessened the number of participants in each group; therefore, the power of the study might be insufficient for detecting small differences in risk of infrequent events. Other limitations include the open-label design of this study, potentially increasing the possibility of bias. In addition, there might have been differences in other nonpharmacological cholesterol-lowering interventions (eg, diet, exercise, and weight loss) in the UC group compared with the pravastatin group, particularly because the control group had frequent follow-up visits, which could motivate a healthier lifestyle; however, these factors were not measured in the ALLHAT-LLT. Finally, while there were significant differences in LDL-C levels by year 6 between the pravastatin group and the UC group in the preselected participants, an increasing number of participants in the UC group were taking a lipid-lowering drug (29.0% [77 of 266]), and an increasing number of participants in the pravastatin group were not taking the study drug by year 6 (22.2% [56 of 204]) (crossover). This level of crossover should be considered when interpreting our findings.

Conclusions

This secondary analysis of the subset of older adults who participated in the ALLHAT-LLT showed no benefit of primary prevention for all-cause mortality or CHD events when pravastatin was initiated for adults 65 years and older with moderate hyperlipidemia and hypertension. A nonsignificant trend toward increased all-cause mortality with pravastatin was observed among adults 75 years and older.

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Summary of Study Sample Exclusions Due to Baseline Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD), n (%)

eTable 2. Visit Compliance and Use of Lipid-Lowering Medications in the Pravastatin Group and Usual Care Group

eTable 3. Lipid Values at Baseline and Years 2, 4, and 6 of Follow-up

eTable 4A. Multivariate Regression for All-Cause Mortality Including Interactions of Treatment Group and Age

eTable 4B. Multivariate Regression for CHD Events Including Interactions of Treatment Group and Age

References

- 1.United States Census Bureau 2012 National population projections: summary tables. http://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/national/2012/summarytables.html. Accessed April 10, 2017.

- 2.Chokshi NP, Messerli FH, Sutin D, Supariwala AA, Shah NR. Appropriateness of statins in patients aged ≥80 years and comparison to other age groups. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(10):1477-1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johansen ME, Green LA. Statin use in very elderly individuals, 1999-2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(10):1715-1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strandberg TE, Kolehmainen L, Vuorio A. Evaluation and treatment of older patients with hypercholesterolemia: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;312(11):1136-1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinberger Y, Han BH. Statin treatment for older adults: the impact of the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines. Drugs Aging. 2015;32(2):87-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97(18):1837-1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Ruijter W, Westendorp RG, Assendelft WJ, et al. Use of Framingham risk score and new biomarkers to predict cardiovascular mortality in older people: population based observational cohort study. BMJ. 2009;338:a3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krumholz HM, Seeman TE, Merrill SS, et al. Lack of association between cholesterol and coronary heart disease mortality and morbidity and all-cause mortality in persons older than 70 years. JAMA. 1994;272(17):1335-1340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schatz IJ, Masaki K, Yano K, Chen R, Rodriguez BL, Curb JD. Cholesterol and all-cause mortality in elderly people from the Honolulu Heart Program: a cohort study. Lancet. 2001;358(9279):351-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kronmal RA, Cain KC, Ye Z, Omenn GS. Total serum cholesterol levels and mortality risk as a function of age: a report based on the Framingham data. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(9):1065-1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petersen LK, Christensen K, Kragstrup J. Lipid-lowering treatment to the end? a review of observational studies and RCTs on cholesterol and mortality in 80+-year olds. Age Ageing. 2010;39(6):674-680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. ; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines . 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25, pt B):2889-2934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han BH, Weinberger Y, Sutin D. Statinopause. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(12):1702-1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. ; US Preventive Services Task Force . Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316(19):1997-2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Redberg RF, Katz MH. Statins for primary prevention: the debate is intense, but the data are weak. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):21-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FAH, et al. ; JUPITER Study Group . Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(21):2195-2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glynn RJ, Koenig W, Nordestgaard BG, Shepherd J, Ridker PM. Rosuvastatin for primary prevention in older persons with elevated C-reactive protein and low to average low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels: exploratory analysis of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(8):488-496, W174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yusuf S, Bosch J, Dagenais G, et al. ; HOPE-3 Investigators . Cholesterol lowering in intermediate-risk persons without cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(21):2021-2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shepherd J, Blauw GJ, Murphy MB, et al. ; PROSPER Study Group (Prospective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk) . Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9346):1623-1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Odden MC, Pletcher MJ, Coxson PG, et al. Cost-effectiveness and population impact of statins for primary prevention in adults aged 75 years or older in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(8):533-541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group Major outcomes in moderately hypercholesterolemic, hypertensive patients randomized to pravastatin vs usual care: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT-LLT). JAMA. 2002;288(23):2998-3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis BR, Cutler JA, Gordon DJ, et al. ; ALLHAT Research Group . Rationale and design for the Antihypertensive and Lipid Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). Am J Hypertens. 1996;9(4, pt 1):342-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pressel S, Davis BR, Louis GT, et al. ; ALLHAT Research Group . Participant recruitment in the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). Control Clin Trials. 2001;22(6):674-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright JT Jr, Cushman WC, Davis BR, et al. ; ALLHAT Research Group . The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT): clinical center recruitment experience. Control Clin Trials. 2001;22(6):659-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.ALLHAT. The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) Data Coordinating Center. http://allhat.org. Accessed November 1, 2016.

- 26.Wenger NS, Shekelle PG. Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders: ACOVE project overview. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(8, pt 2):642-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wenger NS, Roth CP, Shekelle P; ACOVE Investigators . Introduction to the Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders-3 quality indicator measurement set. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(suppl 2):S247-S252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sewright KA, Clarkson PM, Thompson PD. Statin myopathy: incidence, risk factors, and pathophysiology. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2007;9(5):389-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Golomb BA, Evans MA, Dimsdale JE, White HL. Effects of statins on energy and fatigue with exertion: results from a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(15):1180-1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Padala KP, Padala PR, Potter JF. Statins: a case for drug withdrawal in patients with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(6):1214-1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collins R, Reith C, Emberson J, et al. Interpretation of the evidence for the efficacy and safety of statin therapy. Lancet. 2016;388(10059):2532-2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krumholz HM. Statins evidence: when answers also raise questions. BMJ. 2016;354:i4963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alpérovitch A, Kurth T, Bertrand M, et al. Primary prevention with lipid lowering drugs and long term risk of vascular events in older people: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2015;350:h2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobs JM, Cohen A, Ein-Mor E, Stessman J. Cholesterol, statins, and longevity from age 70 to 90 years. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(12):883-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gnjidic D, Le Couteur DG, Blyth FM, et al. Statin use and clinical outcomes in older men: a prospective population-based study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(3):e002333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Afilalo J, Duque G, Steele R, Jukema JW, de Craen AJ, Eisenberg MJ. Statins for secondary prevention in elderly patients: a hierarchical Bayesian meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(1):37-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Lorgeril M, Salen P, Abramson J, et al. Cholesterol lowering, cardiovascular diseases, and the rosuvastatin-JUPITER controversy: a critical reappraisal. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(12):1032-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Summary of Study Sample Exclusions Due to Baseline Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD), n (%)

eTable 2. Visit Compliance and Use of Lipid-Lowering Medications in the Pravastatin Group and Usual Care Group

eTable 3. Lipid Values at Baseline and Years 2, 4, and 6 of Follow-up

eTable 4A. Multivariate Regression for All-Cause Mortality Including Interactions of Treatment Group and Age

eTable 4B. Multivariate Regression for CHD Events Including Interactions of Treatment Group and Age