Abstract

The HIV-1-envelope (Env) trimer is covered by a glycan shield of ~90 N-linked oligosaccharides, which comprises roughly half its mass and is a key component of HIV evasion from humoral immunity. To understand how antibodies can overcome the barriers imposed by the glycan shield, we crystallized fully glycosylated Env trimers from clades A, B and G, visualizing the shield at 3.4-3.7 Å resolution. These structures reveal the HIV-1-glycan shield to comprise a network of interlocking oligosaccharides, substantially ordered by glycan crowding, which encase the protein component of Env and enable HIV-1 to avoid most antibody-mediated neutralization. The revealed features delineate a taxonomy of N-linked glycan-glycan interactions. Crowded and dispersed glycans are differently ordered, conserved, processed and recognized by antibody. The structures, along with glycan-array binding and molecular dynamics, reveal a diversity in oligosaccharide affinity and a requirement for accommodating glycans amongst known broadly neutralizing antibodies that target the glycan-shielded trimer.

INTRODUCTION

Glycan shields reside at the interface between virology, glycobiology and immunology. Very few pathogens withstand the antibody-mediated onslaught of the humoral immune system, but HIV can. Indeed, despite the presence of high titer HIV-reactive antibodies, sustained viremia is frequently observed over years of chronic HIV infection (Wei et al., 1995). The primary mechanism appears to be an evolving glycan shield (Wei et al., 2003), which couples the typical mutational rate of a small RNA virus (Jenkins et al., 2002) with an extraordinary level of N-linked glycosylation on the HIV-1 envelope (Env) glycoproteins (Allan et al., 1985), gp120 and gp41, which trimerize to form the HIV-1 viral spike, the only exposed viral antigen on the virion surface (reviewed in (Wyatt and Sodroski, 1998)). A median of 93 N-linked glycans (95% CI = 75-105, based on 2994 Env M-group sequences (www.hiv.lanl.gov)), cloak the surface of the trimeric spike and comprise over half its mass (Leonard et al., 1990) (Table S1).

Each N-linked glycan is encoded by a tripeptide, Asn-X-Ser/Thr, the N-glycan sequon (reviewed in (Kornfeld and Kornfeld, 1985)), which is recognized by oligosaccharyltransferase on nascent polypeptides as they extrude into the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum to couple a fully formed Glc3Man9(GlcNAc)2 precursor (2371 Da) to Asn in the N-glycan sequon (Hanover and Lennarz, 1980). The Glc3Man9(GlcNAc)2 precusor is trimmed by glycosidases through high mannose forms, then modified by glycotransferases, which assemble complex glycans in the Golgi meant for signaling and other glycobiology functions utilized by nearly all secreted or cell-surface expressed proteins in humans (Varki, 2011).

Because of their ubiquitous presence, all of these forms of N-linked glycosylation – high mannose through complex – are privileged from antibody recognition through check-point induced tolerance of the functional antibody repertoire. While antibodies can recognize non-self glycans (such as their recognition of the glycan antigens that define the human blood groups) (Stowell et al., 2008), if antibody recognition of a viral N-linked glycan were to result in cross-recognition of host N-linked glycans, such self-recognition results in the anergy or apoptosis of the N-glycan-reactive B cell (Wardemann et al., 2003). The upshot is that antibodies only recognize viral N-linked glycans in the context of a viral protein (a glycoprotein epitope) (Kong et al., 2013; McLellan et al., 2011; Pejchal et al., 2011) or in the context of at least two other viral glycans (an exclusively glycan-based epitope) (Sanders et al., 2002; Scanlan et al., 2002).

The ability of glycan shields to thwart the humoral response is demonstrated in part by their ubiquity: viruses as diverse as hepatitis C virus (HCV; Flaviviridae) (Helle et al., 2011), Epstein Barr virus (EBV; Herpesviridae) (Szakonyi et al., 2006), and Lassa virus (LASV; Arenaviridae) (Sommerstein et al., 2015), along with the aforementioned HIV-1, have extensive N-linked glycosylation, which covers exposed protein surfaces and whose glycan mass can exceed that of the protein component. Of these, the HIV-1 glycan shield is perhaps the most well-characterized. Structural studies of the HIV-1 Env trimer or its gp120 subunit have revealed tantalizing glimpses; however, glycosylated gp120 structures lack the interprotomer interactions of the pre-fusion closed state (Diskin et al., 2013; Kong et al., 2015), and at best only about a quarter of the glycan content has been observed with published trimeric structures (Garces et al., 2015; Julien et al., 2013; Kwon et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2016; Lyumkis et al., 2013; Pancera et al., 2014; Scharf et al., 2015) (Table S2). Thus, despite its importance, knowledge of the glycan shield has been primarily antibody-epitope focused, with little understanding of its cumulative characteristics, aggregate properties, and atomic-level structure. Here we present the 3.4 Å structure of a fully glycosylated HIV-1 pre-fusion trimer from clade G and characterize the organization of glycans and clustering of oligomannose residues. Additionally we present the 3.7 Å structures of fully glycosylated HIV-1 pre-fusion trimers from clades A and B and carried out molecular dynamics simulations and other analyses to provide insight into antibody-glycan interactions. The results reveal the HIV-1 glycan shield to form a network of interlocking oligosaccharides, substantially ordered by glycan crowding, which encase the protein component of the trimer and enable HIV-1 to avoid most antibody-mediated neutralization.

RESULTS

Design and Production of Diverse Pre-Fusion HIV-1 Trimers

To provide a general understanding of the HIV-1 glycan shield, we sought to determine crystal structures of glycan-shielded Env trimers from diverse HIV-1 clades. The production of pre-fusion closed trimers from diverse HIV-1 strains has been an obstacle to structural and immunogenicity studies. Sanders, Moore and colleagues identified a clade A strain (BG505), stabilized by a disulfide (SOS) and isoleucine to proline mutation (IP) and truncated at residue 664, which formed stable soluble trimers (Sanders et al., 2013). However, when SOSIP mutations were incorporated into other HIV-1 strains, many misfolded or formed aberrant structures, although more recently a few additional well-folded HIV-1 Env strains in the SOSIP context have been identified (de Taeye et al., 2015; Julien et al., 2015; Pugach et al., 2015). As the addition of antibody VRC01 to BaL gp160 HIV-1 virions stabilizes the pre-fusion closed state as assessed by cryo-electron tomography (Tran et al., 2012), we investigated whether the co-expression of antibody VRC01 with HIV-1 Env trimers might promote formation and stabilization of pre-fusion closed trimers.

To aid in VRC01-trimer complex formation, we designed cysteine mutations across the interface of the heavy chain of antibody VRC01 (A60CHC) and the CD4-binding site of HIV-1 gp120 (G459Cgp120) from a range of HIV-1 clades (Figure S1A) (for clarity, the molecule is added as subscript, see Extended Experimental Procedures). We succeeded in expressing covalent complexes of scFv or Fab VRC01 with SOSIP-stabilized trimers (Figure S1B-J), as stable pre-fusion closed Env trimers from diverse HIV-1 strains.

Structure of a Fully Glycosylated HIV-1 Env Trimer from Clade G

We observed the lattice formed by antibodies PGT122 and 35O22 in the BG505 SOSIP.664 T332N trimer structure (PDB 4TVP) (Pancera et al., 2014) to be dependent on antibody-antibody contacts (Figure 1A), and complexed Fabs PGT122 and 35O22 with fully glycosylated clade G X1193.c1 SOSIP.665 G459C trimers covalently linked with scFv VRC01 (A60CHC) (Figure S1K) and crystallized in hanging droplets. Data extended to a nominal 3.4 Å resolution, and the structure were refined to an Rwork/Rfree of 21.4%/27.2% with an average of 4.8 refined saccharide units/sequon and a solvent accessible-surface area for protein versus carbohydrate of 74,915 Å2 and 73,948 Å2 respectively. (Tables S2-S4, Methods and Extended Experimental Procedures). Electron density was observed for all HIV-1 Env residues between 31 and 665 of strain X1193.c1, except for 3 gp120 C-terminal amino acids of the engineered R6 furin cleavage site from 508-510. All five variable loops (V1-V5) of gp120 were resolved along with the complete fusion peptide of gp41, which was partially stabilized by an interprotomer interaction with a neighboring gp41 α9 helix (Figure S2A). In terms of glycan, ultra-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry confirmed the N-linked glycan to be primarily high mannose, with, Man5GlcNAc2 (Man-5), constituting 31.4% of the glycan, and Man-6 and Man-7 being much less predominant than Man-8 and Man-9 (Table S5). We observed electron density for 29 of the 31 N-linked glycans of X1193.c1 strain, which were distributed across the trimer protein surface (Figures 1B, S1L, S1M). 19 of these glycans were largely exposed to the solvent space between individual trimers suspended by the PGT122 and 35O22 Fabs in the crystal lattice (Figures S1N, S1O). Three glycans showed extensive interactions with antibody including N88 to 35O22, N276 to VRC01, and N332 to PGT122, whereas no glycans were involved in forming crystallization contacts, thereby providing a mostly unperturbed view of the HIV-1 trimeric glycan shield.

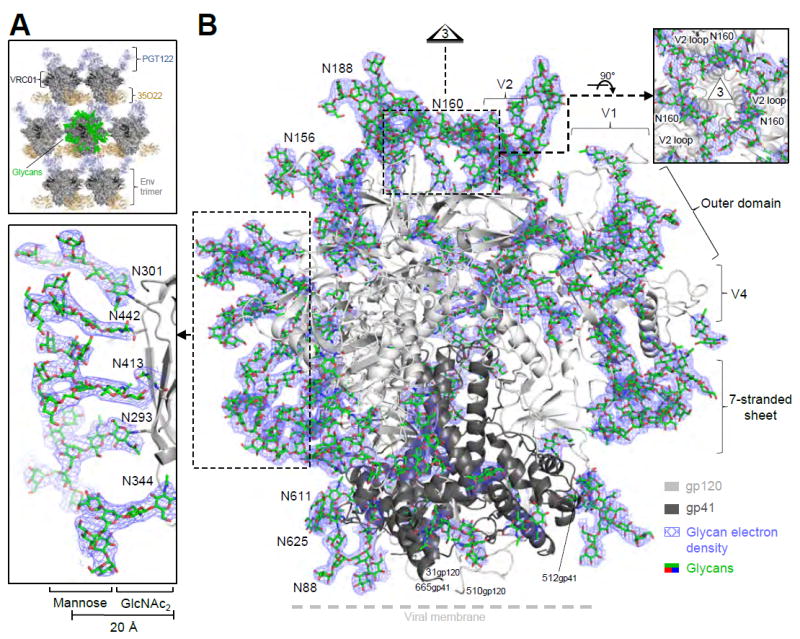

Figure 1. Crystal structure of a fully glycosylated HIV-1 Env trimer at 3.4 Å resolution reveals an ordered glycan shield.

(A) Lattice comprising Fabs 35O22 (gold) and PGT122 (light blue) holds fully glycosylated HIV-1 Env trimers (surface representation in dark gray, with glycan highlighted in green on a representative trimer), with variable domain-only VRC01 in dark gray. (B) Crystal structure of a fully glycosylated SOSIP trimer from clade G strain X1193.c1 with gp120 (light gray) and gp41 (dark gray) in ribbon representation and glycans (green) in stick representation. 2Fo-Fc electron density (slate blue) is shown at 0.8 σ for glycans; altogether over half of the carbohydrate has been crystallographically resolved. Insets show select clusters of N-linked glycans, comprising N-acetylglucosamine residues protruding perpendicularly from the protein surface and supporting mannose branches, which form a glycan canopy ~20 Å from the protein surface. A view down the 3-fold is provided in Figure 2D. See also Figure S1 and Tables S3 and S4.

We observed numerous occurrences of glycans organized into discrete structural groups. For example, at the apex of the trimer where the three C-strands of V1/V2 associate, glycan N160 was substantially ordered: two N-acetyl glucosamines (GlcNAc2) and the β-mannose sugar (Manβ) projected perpendicularly 20 Å from the protein surface (Figure 1B, right insert), with oligomannose branches engaged horizontally, making direct contacts with neighboring N160 oligomanose branches and assembling into an interprotomeric oligomannose ring about ~15 Å in diameter. The N160 glycans were buttressed by V1 side chains Glu187A and Lys187B, which contacted N160 mannose and N-acetylglucosamine residues, respectively. Additionally, mannose residues of the V1 glycan N188 contacted mannose residues of the N160 glycan ring. The conformation of the N160-glycan ring thus appeared to depend on the V1 sequence, its structure, and its glycosylation.

The N-glycan density on the gp120 outer domain was particularly high (Figure 1B, left insert). This region contained glycans that were most clearly defined in the electron density (except for glycans bound by antibody). The structure revealed Manβ1,4GlcNAcβ1,4GlcNAc stems to extend perpendicularly ~20 Å from the protein surface, with oligosaccharide branches forming a lateral canopy of glycans that extended from the membrane-proximal 35O22 epitope all the way to the variable loop cover of the trimer apex. In this ridge of interconnected glycans, oligosaccharides showed extensive electron density and allowed five Man-8 and Man-9 glycans to be modeled. However in other regions such as the glycans from gp41, only 2-3 sugar residues could be fitted to the electron density. In general, glycans not bound by antibody had B-factors similar to those observed for hypervariable loop residues (Figure S2B, C).

Structures of Fully Glycosylated HIV-1 Env Trimers from Clades A and B

We used the PGT122-35O22-HIV-1 trimer lattice to crystallize a fully glycosylated VRC01-complexed Env trimer from the clade B strain JR-FL as well as a fully glycosylated Env trimer from the clade A strain BG505 (Figure S2D). Diffraction from these crystals extended to nominal resolutions of 3.7 Å, and molecular replacement and refinement led to Rwork/Rfree of 25.3%/30.9% and 26.0%/30.7% for JR-FL and BG505, respectively, with an average of 4.6 and 3.8 refined saccharide units/sequon respectively and protein verses carbohydrate solvent accessible-surface area values of 66,575 verses 68,502 Å2 (JR-FL) and 67,960 verses 60,640 Å2 (BG505) (Tables S2-S4). Interestingly, despite general similarity of the lattice, the crystallizing antibodies did show strain-dependent variation, especialy with N137, a glycan known to be important in PGT122 recognition (Garces et al., 2015; Garces et al., 2014). N137 was disordered in JR-FL, ordered in BG505 and displaced by a V1 extension in X1191.c1 (Figure S2E).

Glycan compositions were high mannose, consistent with the GnTI-deficient cell line used for production, with Man-5 constituting 24.6% and 15.3% of the glycan from JR-FL and BG505 strains, respectively, and with Man-8 and Man-9 dominating over Man-7 and Man-6 (Table S5, Figure S3A). The glycan shields of BG505 SOSIP.664 and JR-FL SOSIP.664 revealed varied organizations of glycans on the HIV-1 trimer surfaces (Figures 2A, B, S2F), likely arising from differences in the positions of glycan sequons as well as differences in Env loop lengths and amino acids near N-linked glycans. Stem structures involving Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1,4GlcNAc, however, were generally conserved and projected similarly from the protein surface (Figure 2C), with oligomannose arms forming strain-dependent organizations. Overall, each of the three glycan structures appeared to provide substantial shielding of the pre-fusion HIV-1 Env trimer (Figure 2D).

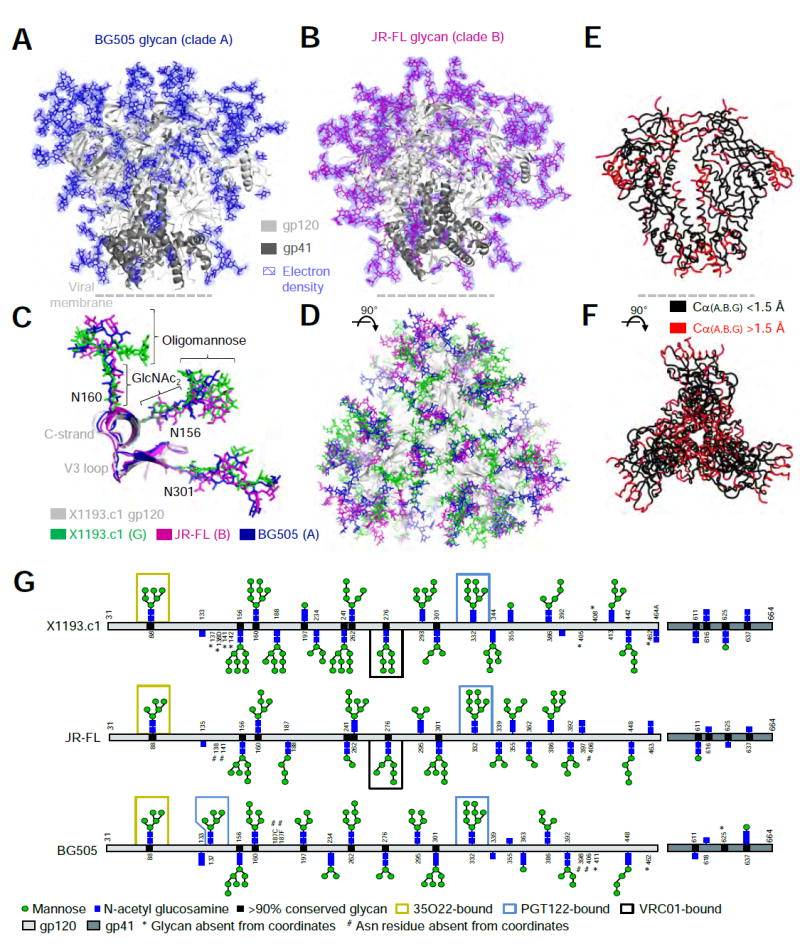

Figure 2. Fully glycosylated HIV-1 envelopes from clades A and B at 3.7 Å reveal conservation and diversity of protein and glycan shield.

(A-B) HIV-1 trimers with protein in ribbon representation and glycan (BG505; blue, JR-FL; magenta) in sticks. 2Fo-Fc electron density (slate blue) is shown at 0.8 σ for glycans; assuming the average glycan is Man-7, ~50% of the glycan mass is ordered. (C-D) Superposition of Env trimers from clades A, B and G. Protein and glycan are colored as indicated, except that the clade G protein is shown in gray for clarity. (E-F) Env conserved core (black) with structural variation of Cα > 1.5 Å highlighted in red. (G) Residue-level schematic of crystallographically observed glycans. See also Figure S2 and Tables S3 and S4.

The protein structures of the clades A, B and G Env analyzed here serve to define a conserved pre-fusion HIV-1 Env core (Figure 2E, F), with structural variability for both surface residues and internal residues such as the interhelical region of gp41 (Figure S2A, D). Comparison of the glycan order present in the three gp140 strains showed high correlation between different clades (r = 0.766 - 0.798) (Figure 2G). Thus, the clade A and clade B Env structures confirmed much of the ordered glycan shield observed with the clade G Env structure, and along with the clade G structure defined conserved glycan and protein core structures, as well as variable features.

A Distance-Based Classification of N-Linked Glycan-Glycan Interactions

Analysis of the inter-sequon neighbor distances revealed glycans on the HIV-1 trimers to have average nearest inter-glycan sequon distance peaking at 12 Å, and we classified these into three categories: (I) 4-7 Å, (II) 9-18 Å and (III) >20 Å (as measured by glycan sequon Asn Nδ2-Nδ2 atom distance) (Figure 3A). The dispersal of HIV-1 Env glycans was distinct from that observed with other type 1 fusion machines (Figure 3B). With HIV-1, a variety of glycan-glycan interactions was observed (Figures 3C, S3B-E). In category I, glycans made contacts primarily via GlcNAc stem residues. When glycan sequons were closely juxtaposed (e.g. 4 Å apart), we observed glycan forking (Figure 3C upper left); however, when the distance between sequons was slightly increased (e.g. 6 Å apart), glycan stems were observed to align in a parallel manner (Figure 3C lower left). Category II glycans with 9–18 Å inter-sequon distances lacked interactions between GlcNAc2 stems; rather GlcNAc2 stems were generally solvated, with glycan-glycan interactions occurring via oligomannose branches. These generally contacted other oligomannoses (branch-branch engagement), although interactions with GlcNAc2 stems (stem-branch association) were also observed (Figure 3C, middle-left panels). More complex associations or network of associations (Figure S3B-D) were observed comprising a variety of interlocking assemblies with two and sometimes three glycans clustering together (Figure 3C middle right panels), and including some long-range inter-glycan interactions, where sequons can be separated by 30 Å (Figure 3C, lower right). Despite the ability of glycans to form long-range interactions, these were not observed with category III glycans. Rather, category III glycans showed electron density for only two or three protein-proximal saccharide units and lacked clearly defined glycan-glycan interactions (Figure 3C, upper right).

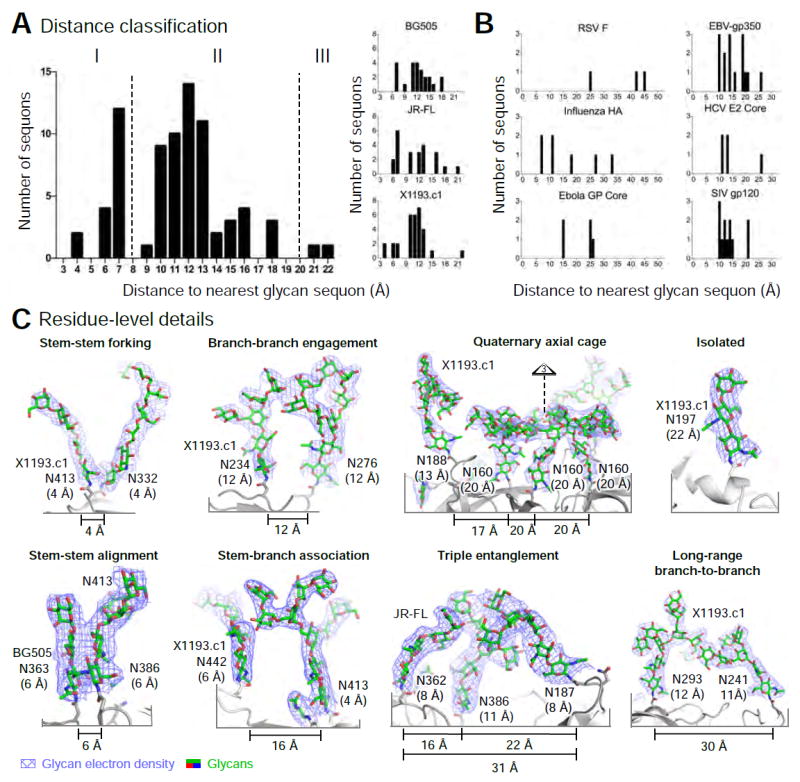

Figure 3. Taxonomy of glycan-glycan interactions that comprise the HIV-1 glycan shield.

(A) Classification based on nearest interglycan sequon distance, with histograms showing glycans from each trimer (right) and from the composite of three trimers (left). (B) Nearest-neighbor analysis for various viral Env glycoproteins. (C) Glycan residue-level details for glycan-glycan interactions. Glycans are shown in stick representation, with 2Fo-Fc electron density (slate blue) at 0.8 σ. Nearest Nδ2 glycan sequon neighbor distance is shown in parentheses. See also Figure S3.

The various observed glycan-glycan interactions may inhibit steric access to the protein surface. Steric inhibition might occur though an ‘umbrella effect’, where a single glycan shields a local patch (such as with glycan N197, Figure 3C, upper right), through a ‘mesh effect’, where two or more oligosaccharides interact locally (such as with X1193.c1 glycans N241 and N293, Figure 3C, lower right), or through a ‘forest effect’ where the spacing of sequons forms a substantially interacting glycan shield by creating an oligosaccharide canopy over the protein surface which may impede protein surface access (such as the glycan-shielded apex of X1193.c1, Figure 3C, upper middle right). In addition to these ordered effects, the disordered regions of the glycan shield may form entropic or dynamic barriers, also inhibiting access to the protein surface of Env.

Surface Glycan Density and Glycan Order

To understand the degree of ordered glycans on these fully glycosylated Env trimers, we investigated parameters that correlated with increased glycan order. The correlation between the number of ordered saccharide units in a glycan versus its nearest neighbor distance was not signific Figure S3F-H), however, we did observe strong correlations between the number of ordered saccharide units and the number of surrounding active sequons within spherical radii ranging from 10 to 55 Å (Figure 4A). When considering all three Env trimer structures, the Pearson correlation coefficient between the number of ordered saccharide units and the number of active sequons became significant at 20 Å, which may relate to a first shell of supporting glycans, and peaks at a radius of 50 Å, which may include a second shell of supporting glycan (Figure 4B). Application of this radial cutoff to each Env trimer structure yielded similar correlations (Figure S4A) and allowed for the definition of two distinct classes of glycans: “crowded” or “dispersed”, based on the number of neighboring sequons and the number of ordered saccharide units. By using Fisher’s exact test based on a 2 × 2 contingency table, we determined 15 neighboring sequons to provide the optimal separation between the two classes (see Methods for details and Figure S4B, C). Thus, a glycan was classified as being crowded if it had 15 or more neighboring glycans and dispersed if it had fewer than 15 neighboring glycans, within a 50 Å radius (Figures 4C, S4D).

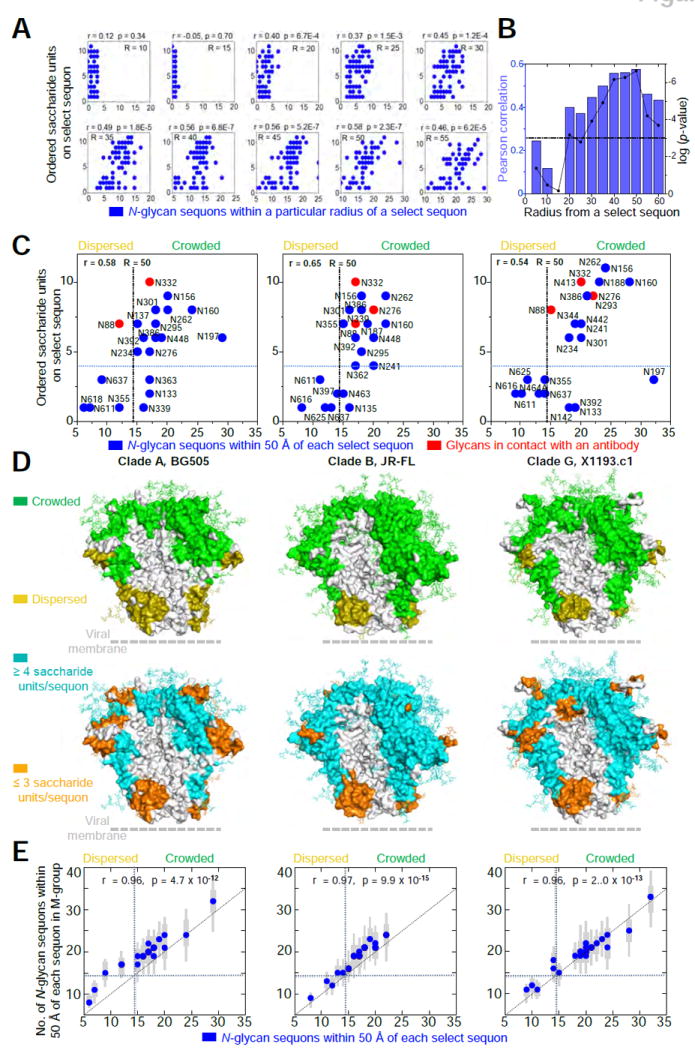

Figure 4. N-glycan crowding provides a mechanism for glycan order.

(A) Number of crystallographically ordered saccharide units on a particular sequon relative to the density of neighboring N-linked glycans. Radii (R) range from 10-55 Å and are centered on Nδ2 of the Asn residue in the N-linked glycan sequon. There were a total of 69 occupied sequons in the three crystal structures. All correlation values were determined using a Pearson correlation (r). (B) Pearson correlation values (blue) and associated log(p-value) values (black) plotted for radii ranging from 5-60 Å. The dotted black line represents a p-value of 0.001 for reference. (C) The number of neighboring N-linked glycans observed in crystal structures for BG505 (clade A, left), JR-FL (clade B, middle) and x1193.c1 (clade G, right) at a radial cutoff of 50 Å. Blue circles denote sequon positions with at least one crystallographically observed saccharide unit. Red circles denote sequon positions with glycans in contact with an antibody. The total number of occupied sequons for BG505, JR-FL and X1193.c1 was 21, 23, and 25 respectively. The dotted lines represent the best partitioning of the x and y variables using Fishers Exact test (see methods for details). (D) Crowded and dispersed glycans mapped onto the surface of each Env trimer structure (top row). Crystallographically ordered glycans were also mapped onto the surface of each Env trimer structure (bottom row). N-linked glycans are displayed in stick representation. To enhance visualization, all neighboring residues within 10 Å were also colored accordingly. (E) For each glycan in the three crystallized strains, the corresponding glycan crowding was determined for each of 2994 M-group sequences by threading the BG505, JR-FL and X1193.c1 structures. Blue circles indicate the median glycan neighbors, thick grey bars indicate the interquartile range and thin grey bars indicate the 95% range around the median. We found significant correlation between the number of glycan neighbors in the three strains and the median neighbors for M-group sequences. See also Figure S4.

To visualize differences between the location of crowded and dispersed glycans, we generated protein surface representations, which highlighted the 10 Å vicinity around each glycan sequon. This revealed that crowded glycans generally occupied the membrane-distal region of the Env trimer as well as the outer ridge of each gp120 (especialy the outer domain of gp120), whereas dispersed glycans were generally located in the membrane-proximal region of gp41 (Figure 4D, upper row). A common feature shared between all three structures was the presence of glycan-free surface (e.g. surface more than 10 Å from any glycan sequon), mostly located within the recessed regions between protruding outer domains. Strong concordance was observed between the three trimer structures for surfaces associated with crowded and dispersed glycans and the number of saccharide units on each sequon, except that sequons in Env variable loops occasionally contained only a few ordered saccharide units, despite being surrounded by “crowded” glycans (Figure 4D, lower row). Moreover, analysis of M-group Envs showed the pattern of glycan crowding and dispersal observed in the BG505, JR-FL and X1193.c1 trimer structures to be representative of M-group glycans (Figure 4E, Figure S4E).

Molecular Features Associated with Crowded and Dispersed Glycans

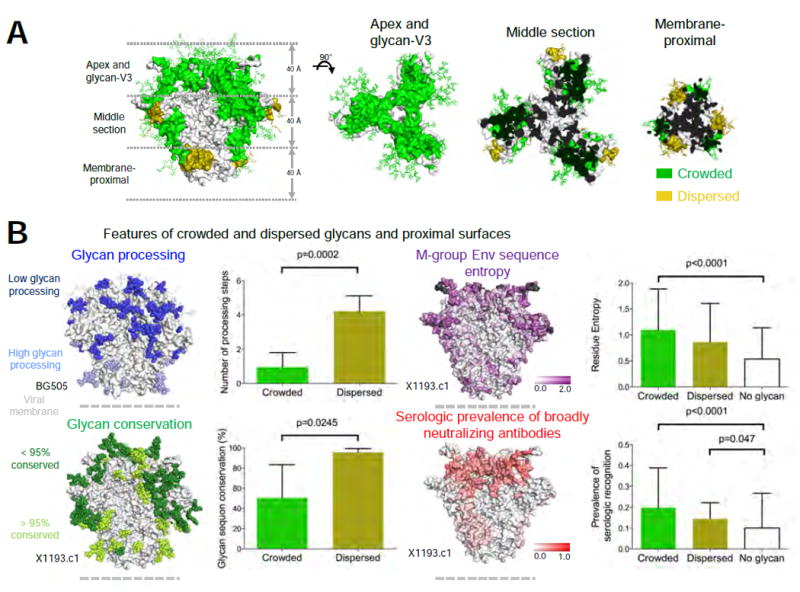

To provide additional insight into the biological characteristics of crowded and dispersed glycans, we analyzed the occurrence of crowded and dispersed glycan (and their 10 Å associated surfaces) within the context of the 3-propellar blades of the prefusion closed trimer (Figure 5A). Notably, crowded glycans and their 10 Å associated surfaces were located primarily on convex surfaces of the trimer and covered the entire membrane-distal apex and glycan-V3 region (Figure 5A, middle left). Half-way down the trimer, the peripheral surfaces of the middle of the trimer were mostly covered by crowded glycan, whereas surfaces closer to the trimer axis were generally not glycosylated (that is, over 10 Å from the nearest glycan sequon) (Figure 5A, middle right). The membrane-proximal surface of the trimer, and half the diameter of the trimer middle, was equally covered by all three types of surfaces (Figure 5A, far right).

Figure 5. Biological characteristics of crowded and dispersed HIV-1 glycans and their associated surfaces.

(A) Regions associated with crowded and dispersed glycans on the X1193.c1 trimer are shown from side (left panel) and top (three right panels) orientations, displayed as 40 Å sections through the trimer axis. (B) Features of crowded, dispersed and glycan-free surfaces. Correlations of crowded and dispersed glycans with glycan processing (upper left), glycan conservation (lower left), Env sequence entropy (upper right, insertion/deletion in hypervariable regions colored black) and serologic prevalence of broadly neutralizing antibodies (lower right). See also Figure S5E.

As dense occurrences of glycan are known to inhibit glycan processing (Guttman et al., 2014; Pritchard et al., 2015), we would expect glycan processing to be greater with dispersed glycan. We used the glycan-type identified on BG505 SOSIP.664 (Guttman et al., 2014) and observed the number of glycan processing steps to be indeed significantly higher for dispersed versus crowded glycan (p = 0.0002, Mann Whitney test) (Figure 5B, upper left). We also observed higher degree of glycan sequon conservation for dispersed glycans compared to crowded glycans (p = 0.0245, Mann Whitney test), using the glycan types defined from M-group analysis. (Figure 5B, lower left). Crowded glycans were significantly enriched (p = 0.014, Mann Whitney test) for glycans showing significant frequency difference between M-group subtypes (27 out of 35), while dispersed glycans were mostly conserved across subtypes (Figure S5A). We also assessed surface residues within 10 Å of crowded or dispersed glycans based on M-group analysis and observed surface-amino acids to be more variable near glycans (Figure 5B, upper right). Broadly neutralizing antibodies showed an increased frequency of recognition near N-linked glycans, with a further increase for regions of crowded glycans (Figure 5B, lower right). Thus crowded and dispersed glycans are differently ordered, processed and conserved, with glycosylated regions most frequently recognized by broadly neutralizing antibodies.

Insight from Molecular Dynamics: Known Broadly Neutralizing Antibody Need To Accommodate Glycan

To provide additional context for crowded and dispersed glycans, we used the BG505 SOSIP.664 T332N trimer structure to carry out three 500 ns molecular dynamics simulations with either Man-5, Man-7 or Man-9 glycans at every sequon (Movie S1). One distinct feature shared among the glycans was an extended conformation for the βMan-GlcNAc-GlcNAc core at the protein proximal stem. In the crystal structures, this angle was similar for crowded and dispersed glycans, both peaking at 145° and similar to the angle observed from the molecular dynamics simulations (Figures 5C, S5B-D, S5F-G). The crowded and dispersed groups displayed substantialy different profiles with respect to non-covalent inter-glycan contacts. In all three simulations, dispersed glycans showed a relatively lower number of glycan-glycan contacts, similar to observations in the crystal structures (Figure S5E-G). Altogether, these results indicate a strong concordance between crystallographic and MD results.

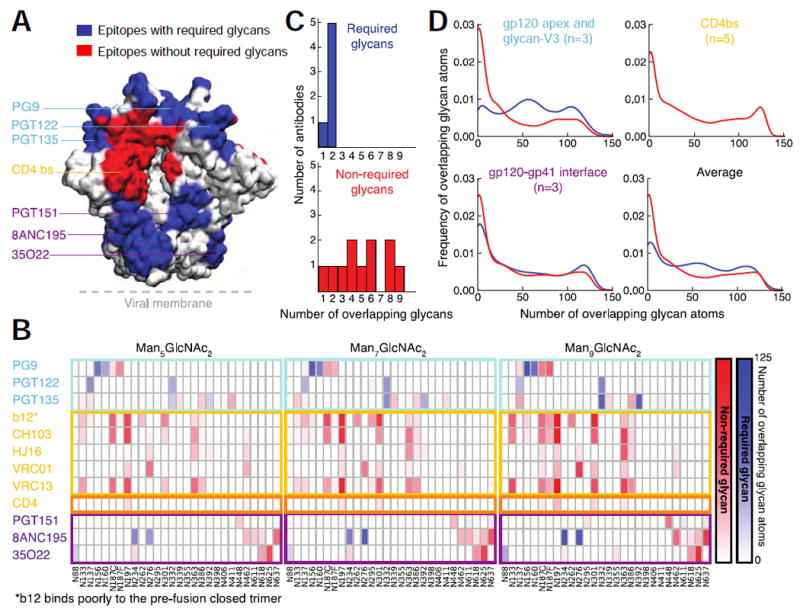

We analyzed the three 500 ns molecular dynamics simulations for glycan overlap of the volumes of bound broadly neutralizing antibodies (Figure 6A, B, Figure S6A-D and Table S6). Quantitative analysis of the extent of overlap between the volume occupied by broadly neutralizing antibodies and individual glycans throughout the trajectories (Figure 6B) showed concordance between the three oligomannose simulations. This analysis also revealed that CD4 and all of the 11 broadly neutralizing antibodies analyzed, including those targeting the CD4-binding site, showed substantial overlap with at least one glycan. The simulation confirmed that antibodies known to require select glycans for recognition (PG9, PGT122, PGT135, PGT151, 8ANC195 and 35O22) did, indeed, have these glycans occupying their bound volumes. CD4-binding site directed antibodies (b12, CH103, HJ16, VRC01, and VRC13) also showed substantial occupation of their binding volume by up to 9 glycans (Figure 6B, C). Moreover, atomic-level analysis of the frequency of overlap for required glycans and non-required glycans revealed similar distributions of glycan-antibody overlap (Figure 6D). These results indicated that known broadly neutralizing antibodies likely need to accommodate at least one glycan.

Figure 6. Molecular dynamics simulations reveal known broadly neutralizing antibodies that recognize the pre-fusion closed trimer need to accommodate N-linked glycan.

(A) Epitopes for known broadly neutralizing antibodies displayed on the surface of the HIV-1 Env trimer. Epitopes are colored blue if N-linked glycans are known to be required for recognition and red if they are not required. (B) Glycan-antibody overlap analysis derived from MD simulations of Man-5, Man-7 and Man-9 models of the HIV-1 glycan shield. Overlap is colored blue for glycans known to be required for recognition by a particular antibody and red for glycans not known to be required for recognition. (C) Distribution graphs of required and non-required glycans. (D) Frequency of overlapping glycans versus number of overlapping glycan atoms. See also Figure S6, Table S6, and Movie S1.

Insight from Glycan Arrays: Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies Display Sporadic Affinity for Oligosaccharide

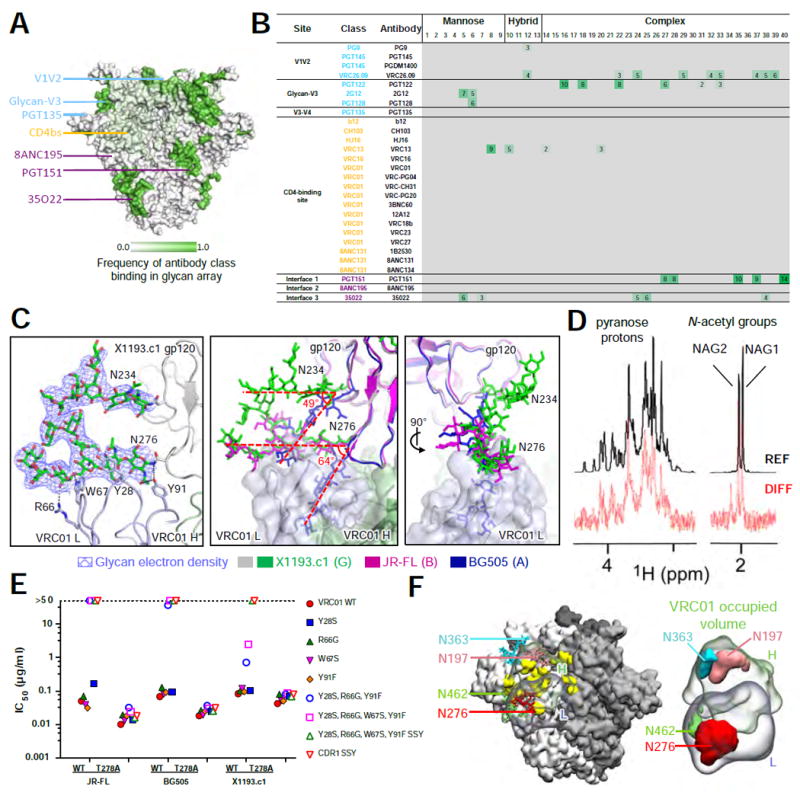

Antibodies can recognize glycans in a variety of ways, including high affinity binding of oligosaccharides. We assessed oligosaccharide binding for the 11 antibodies analyzed in Figure 6B as well as for the 16 CD4-binding site antibodies analyzed previously in the context of the CD4 supersite (Zhou et al., 2015) using an array of 40 oligosaccharides (Figure 7A, B) containing glycans representative of oligomannose, hybrid and complex-type glycans (Figure S6E).

Figure 7. Broadly neutralizing antibodies recognize oligosaccharides with a broad range of affinities.

(A) Epitope-specific frequency of recognition of oligosaccharides by broadly neutralizing antibodies displayed on the surface of trimeric HIV-1 Env. (B) Relative fluorescence index (× 106) for broadly neutralizing antibody recognition of 40 oligosaccharides coupled to glass slides. (C) Ordered glycans N276 and N234 with 2Fo-Fc electron density at 0.8 σ in the X1193.c1 structure (left) bound to VRC01 light chain via van der Waal’s contacts and hydrogen bonds. Superimposition of BG505, JR-FL and X1193.c1 structures (middle) showing the relative difference in orientation of N276 and N234 glycans between the VRC01-bound X1193.c1 and JR-FL structures and the BG505 structure (which was not complexed to VRC01). (D) Detection of VCR01 binding to Man9GlcNAc2Asn by Saturation Transfer Difference (STD) NMR. Signals for sugar protons are labeled above the reference spectrum (REF) (glycan only, top). STD enhancements for both N-acetyl groups of the core GlcNAc residues and pyranose protons are displayed in the difference spectrum (DIFF) (VRC01:Man9GlcNAc2Asn complex, bottom). (E) Neutralization titers for VRC01 mutants at the N276 binding interface. (F) Molecular dynamics analysis of glycans overlapping the bound VRC01 volume, showing surrounding glycans and antibody on trimer (left) and isosurface representation of glycans overlapping VRC01 volume (right). See also Figure S7 and Table S6.

Substantial binding was observed for antibodies PGT122 and 35O22 to glycans on the array. While both recognized oligomannose and complex-type glycans (Figure S6F, G), 35O22 binding appeared to be limited to sialylated complex-type glycans whereas PGT122 recognized both, a preference not entirely explained by electrostatic interactions (Figure S6F-I) although a sialic-acid binding site was previously defined for PGT121 (Mouquet et al., 2012) (in this structure, the bound glycan emanates from a neighboring PGT121 Fab in the crystal lattice). Other antibodies (PG9 and PGT151) known to require glycan for recognition displayed interactions with glycans on the array; of the CD4-binding site antibodies, only VRC13 showed significant binding to the glycan array (Figure 7A, B). These results indicated that, while some HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies did have direct high affinity for oligosaccharides, many broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibodies did not have detectable affinity for oligosaccharide in the context of a glycan array. For example, we observed no binding signal for PGT135, which is known to have substantial interaction with N-glycans 332 and 392 in its glycopeptide epitope (Kong et al., 2013).

Antibody Neutralization and Low Affinity Glycan Interactions

In contrast to the lack of glycan array binding by antibody VRC01 (or by any of the 12 antibodies from the VH-gene specific VRC01 and 8ANC131 classes) (Zhou et al., 2015) (Figure 7B), molecular dynamics simulations indicated the bound volume of VRC01 to have substantial overlap with glycans N197, N276, N363 and N462 (Figure 7F). Examination of the fully glycosylated crystal structures of scFv of VRC01 with pre-fusion closed clade B and clade G Envs, indicated little interaction with glycans N197, N363 or N462 (Figure S7A, B), but substantial interactions with glycan N276, which was highly ordered (Figures 7C, left, S7A, B). Similar ordering was previously observed between 45-46m2 and glycan N276 with Env in its receptor-bound conformation (Diskin et al., 2013), indicating interaction with glycan N276 in both receptor-bound and pre-fusion closed conformations.

We compared the orientations of glycan N276 from the crystal structure of glycosylated BG505 SOSIP.664 T332N, with glycan N276 from the VRC01-bound structures of JR-FL SOSIP.664 and X1193.c1 SOSIP.665 trimers (Figure 7C, middle and right). The VRC01-bound structures revealed the N276 glycan to be orientated in a manner compatible with VRC01 antibody access to the CD4-binding site, allowing extensive contacts of the heavy chain with the protein surface of the CD4-binding site. Additionally, comparison of BG505 SOSIP.664 T332N and X1193.c1 SOSIP.665 structures revealed glycan N234 to differ in angle by approximately 49°, apparently re-orientating through a domino effect with glycan N276 in a concerted mechanism with VRC01 binding (Figure 7F, middle).

To determine experimentally whether VRC01 could bind Man9GlcNAc2Asn, we used saturation transfer difference (STD) NMR, an NMR method that can detect protein-ligand interactions with affinities ranging from nM to mM Kds (McLellan et al., 2011). Signals belonging to the N-acetyl groups of the core GlcNAc residues yielded observable STD enhancement arising from GlcNAc and mannose ring protons (Figure 7D), consistent with VRC01 binding to the conserved GlcNAc-manose core. No STD enhancements were observed in control spectra with a sample containing glycan only. Despite this weak affinity, mutation at VRC01 light chain residues at key contact sites with glycan N276 gave rise to a loss of neutralization (Figure 7E). This was also observed in 3BNC117, another VH 1-2-derived antibody that has the same light chain somatic changes as the VRC01-glycan N276 contact residues and other VRC01-like antibodies (Figure S7C-E) (Zhou et al., 2013). These results suggest light chains from the VRC01 class to have somatically matured to functionally engage glycan N276 directly. Even though the glycan affinity of antibody VRC01 was too weak to be detected with glycan arrays, the VRC01 glycan interactions were nonetheless critical for its neutralization of HIV-1. Thus, while all known broadly neutralizing antibodies that target the shielded pre-fusion closed trimer need to accommodate glycan, glycan-array interactions are often not observed (Figures 6B, S7F-H) as antibodies can use a broad range of oligosaccharide affinities to fulfill this requirement.

DISCUSSION

Atomic-level details of glycan shields have long been sought to understand how viruses use glycan to evade host humoral immunity. Here we provide proof-of-principle for the ability of the PGT122-35O22 lattice (Pancera et al., 2014) to visualize fully glycosylated Env trimers from diverse clades. It should be possible to use this lattice or the 3H+109L-35O22 lattice (Garces et al., 2015) to examine different forms of N-linked glycan (e.g. on trimers expressed and processed from T cells) or different types of conformational stabilization (e.g. SOSIP.v1-v4 or DS-SOSIP) (de Taeye et al., 2015; Kwon et al., 2015). Indeed, we have grown crystals of both clade C and 293T-derived BG505 SOSIP with complex sugars (see Extended Experimental Methods), although these crystals need further optimization for atomic-level analysis.

The visualized glycan shields from HIV-1 clades A, B and G revealed a diversity of glycan conformations and glycan-glycan interactions (Figures 1-3, S3B-E). A conserved structural motif involved the projection of protein-proximal GlcNAc2 perpendicular to the protein surface, while protein-distal mannose branches assembled in a variety of ways to form extended canopies of interlocking oligosaccharide arms approximately 20 Å from the protein surface. These glycan orientations differed from N-glycans ordered through interaction with the protein surface (such as glycan N262, in which the GlcNAc stem associates with the protein surface) (Kong et al., 2015) or from glycans bound by antibody (Kong et al., 2013; McLellan et al., 2011; Pejchal et al., 2011), which interrupt branch interactions that provide the dominant form of glycan-glycan contact (Figure 3C). In general, we would expect the overall glycan orientation and glycan-glycan interactions that we observed here to be representative of dominant low energy ground states, in the same way that crystallographically visualized side chains define amino-acid stereochemistry (Engh R. A., 1991). Perhaps relevant to this, visualized glycans were often ordered to the same extent as surface amino-acid side chains (Figure S2B, C).

Although the surface of HIV-1 Env is perhaps the most genetically diverse region of HIV-1, we observed a number of conserved glycan features between the pre-fusion trimer structures from clades A, B and G. In particular, we observed similarities in regions of high and low glycan crowding, which appeared general to all of group M (Figure 4E) – and found regions of high glycan crowding to be correlated with lower glycan conservation, reduced glycan processing, higher Env sequence entropy, and greater serological prevalence of broadly neutralizing antibodies (Figure 5B). It remains to be seen if the biological characteristics of crowded and dispersed glycan that we observed with HIV-1 will be conserved in the glycan shields of other viruses.

The combination of structures and molecular dynamics simulations carried out here suggested known broadly neutralizing antibodies that target the pre-fusion closed trimer need to accommodate glycan (Figure 6). This glycan requirement may explain the observation that high autologous neutralizing titers against HIV-1 Env trimers stabilized in the pre-fusion closed state require more than 15 weeks to develop (Sanders et al., 2015), more than 3-times the time required to develop high autologous neutralizing titers against pre-fusion trimers with less glycosylation such as influenza A hemagglutinin. Perhaps relevant to this, tier 2 virus neutralizing antibodies were recently elicited via a naturally occuring N197 glycan-deficient region of a JR-FL immunogen (Crooks et al., 2015). Moreover, removal of specific glycans has been observed to be critical for interaction of Env with germline versions of some broadly neutralizing antibodies (Correia et al., 2014; Jardine et al., 2013; Jardine et al., 2015). Selective removal of glycans obstructing sites of viral vulnerability may thus allow better access to and priming of naïve B-cell receptors, which could be matured by boosting with glycan-reverted immunogens (Dosenovic et al., 2015; Jardine et al., 2013; Jardine et al., 2015). The diversity that we observed in oligosaccharide recognition by broadly neutralizing antibodies (Figure 7), however, cautions against relying on any single glycan-modifying strategy as a general means of eliciting broadly neutralizing antibodies against HIV-1; thus it may be that the presence of particular glycans such as a Man-5 glycan at residue 160 (Doria-Rose et al., 2014) or a high mannose glycan at residue 332 (Garces et al., 2015; Garces et al., 2014; Kong et al., 2013) is critical for initiating select B cell lineages. Finally, we note that the knowledge of structurally conserved and variable protein domains from the structures of Env from three diverse clades may help to guide the engineering of genotypically diverse HIV-1 Env trimers, perhaps as artificial chimeric vaccine constructs (Gorman et al., 2016). The structures of three fully glycosylated Env trimers described here thus not only allow for a definition of the glycan shield, but also provide insight into ways the shield might be modified to enhance the elicitation of neutralizing antibody.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

HIV-1 gp140 trimer and antibody production

HIV-1 gp140 proteins and antibody complexes were expressed in GnTI- cells and purified as described previously (Pancera 2014) or by using Ni2+ and Strep-tag affinity chromatography followed by gel filtration. PGT122 and 35O22 Fab regions were prepared and purified via size exclusion chromatography (Supplemental Experimental Procedures).

HIV-1 Env trimer-Fab complex preparation and crystallization

Purified trimers were mixed with purified PGT122 and 35O22 antibody Fabs in a 1:2:2 molar ratio (gp140 protomer:Fab:Fab) and incubated overnight at room temperature. Complexes were further purified by size exclusion chromatography and concentrated to 6-10 mg/ml for crystallization. (Supplemental Experimental Procedures).

X-ray data collection, structure solution and model building

Initial structures were solved by molecular replacement using PDB ID 4TVP coordinates as a starting model (Pancera et al., 2014). Model re-building and iterative refinement procedures were carried out as described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures with results shown in Table S3).

Glycan analysis by ultra performance liquid chromatography

Glycosylation profiles of N-linked glycans of purified Env proteins and antibodies were determined by hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography-ultra performance liquid chromatography (HILIC-UPLC) as previously described (Pritchard et al., 2015) (Supplemental Experimental Procedures and Table S5).

Saturation-transfer difference nuclear magnetic resonance

Binding of VRC01 to Man9GlcNAc2Asn was detected by NMR using saturation transfer methods as described (McLellan et al., 2011). Samples were prepared in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer containing 50 mM sodium chloride at pH 6.8. All experiments were carried out at 298 K (Supplemental Experimental Procedures).

Molecular dynamics simulations and glycan-antibody overlap analysis

All molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for the three fully glycosylated BG505 SOSIP.664 trimer models (Man-5, Man-7 and Man-9) were performed over 500 ns in explicit solvent and after superimposition of CD4 and 11 antibody structures, all glycan atoms from the MD trajectory within 3.0 Å of the antibody structure were recorded (Supplemental Experimental Procedures and Table S6).

Bioinformatics and definition of crowded and dispersed glycans

Using Fishers Exact test based on a 2 × 2 contingency table, groups were defined as crowded or dispersed depending on the number of neighboring sequons within a spherical shell of 50 Å and the number of saccharide units. 2994 M-group Env sequences from the from the Los Alamos HIV database (www.hiv.lanl.gov) were threaded onto each structure and the number of neighboring active glycan sequons for each glycan was then determined and was compared to that found for BG505, JR-FL or X1193.c1 (Supplemental Experimental Procedures).

Fabrication of NHS-glycan microarray and antibody-glycan binding assessment

The 40 glycans used in the array analysis were produced by the modular synthesis method and detailed in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Neutralization assays

Single round of replication BG505, JR-FL and X1193.c1 and T278A variant pseudoviruses were prepared, titered, and used to infect TZM-bl target cells as described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R. O’Connor for NMR support, J. Stuckey for assistance with graphics, and members of the Structural Biology Section and Structural Bioinformatics Core, Vaccine Research Center for discussions and comments on the manuscript. We thank Acellera for assistance with molecular dynamics simulations. Support for this work was provided by the Intramural Research Program of the Vaccine Research Center, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health (NIH) and from the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative’s (IAVI’s) Neutralizing Antibody Consortium. IAVI’s work is made possible by support from many donors including: the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark; Irish Aid; the Ministry of Finance of Japan; the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands; the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation; the UK Department for International Development; and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this manuscript do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US Government. The full list of IAVI donors is available at http://www.iavi.org. A-J. B. and M.Crispin were supported by the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative Neutralizing Antibody Center CAVD grant (Glycan characterization and Outer Domain glycoform design) and the Scripps Center For HIV/AIDS Vaccine Immunology-Immunogen Discovery (CHAVI-ID) grant 1UM1AI100663. K. W. and B. K. were supported by the Duke CHAVI-ID grant UM1 AI100645. T. L. was supported by the Swiss National Foundation of Science Fellowship 148914. V. S. S., C. C. L., C. Y. W. and C. H. W. were supported by Academia Sinica and Ministry of Science and Technology grants MOST 104-0210-01-09-02 and 103-2321-B-001-004. C. H. W. was supported by NIH grant R01 AI072155. The Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, National Institutes of Health, is supported under contract HHSN261200800001E. Use of sector 22 (Southeast Region Collaborative Access team) at the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the US Department of Energy, Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science, under contract number W-31-109-Eng-38.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

GSJ, CS and PDK conceived, designed and coordinated the study; GSJ, CS, KW, GYC, TL, PDK wrote and revised manuscript and figures; JRM provided intellectual expertise and guidance; HIV-1 Env designs: GSJ, ISG; Antibody-antigen covalent bond design: GSJ; Protein production: GSJ, AD, PVT, BZ; Crystal structures: GSJ, TZ, PVT, MP, PDK; Molecular Dynamics: GSJ, CS, TL, PDK; Structural analysis: GSJ, CS, KW, TL, PDK; Negative stain EM: UB; VRC01 mutagenesis: GSJ, MGJ; Neutralization assays: RK, JT, CWC, JRM; Glycan UPLC analysis: AJB, M Crispin; Glycan arrays: TZ, SSS, VSS, CCL, CYW, CHW; Bioinformatics sequence analysis: KW, TB, BTK; STD NMR: JB, CAB; provision of PGT122: DRB, WCK; provision of 35O22: M Connors. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

ACCESSION NUMBERS

Coordinates and structure factors for glycosylated X1193.c1 SOSIP-scFv VRC01-PGT122-35O22, JR-FL SOSIP-scFv VRC01-PGT122-35O22 and BG505 SOSIP-PGT122-35O22 complexes have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank under accession codes 5FYJ, 5FYK and 5FYL respectively.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information includes Extended Experimental Procedures, seven figures, six tables, and movie and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/xxx.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allan JS, Coligan JE, Barin F, McLane MF, Sodroski JG, Rosen CA, Haseltine WA, Lee TH, Essex M. Major glycoprotein antigens that induce antibodies in AIDS patients are encoded by HTLV-III. Science. 1985;228:1091–1094. doi: 10.1126/science.2986290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correia BE, Bates JT, Loomis RJ, Baneyx G, Carrico C, Jardine JG, Rupert P, Correnti C, Kalyuzhniy O, Vittal V, et al. Proof of principle for epitope-focused vaccine design. Nature. 2014;507:201–206. doi: 10.1038/nature12966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks ET, Tong T, Chakrabarti B, Narayan K, Georgiev IS, Menis S, Huang X, Kulp D, Osawa K, Muranaka J, et al. Vaccine-Elicited Tier 2 HIV-1 Neutralizing Antibodies Bind to Quaternary Epitopes Involving Glycan-Deficient Patches Proximal to the CD4 Binding Site. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004932. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Taeye SW, Ozorowski G, Torrents de la Pena A, Guttman M, Julien JP, van den Kerkhof TL, Burger JA, Pritchard LK, Pugach P, Yasmeen A, et al. Immunogenicity of Stabilized HIV-1 Envelope Trimers with Reduced Exposure of Non-neutralizing Epitopes. Cell. 2015;163:1702–1715. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diskin R, Klein F, Horwitz JA, Halper-Stromberg A, Sather DN, Marcovecchio PM, Lee T, West AP, Jr, Gao H, Seaman MS, et al. Restricting HIV-1 pathways for escape using rationally designed anti-HIV-1 antibodies. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1235–1249. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doria-Rose NA, Schramm CA, Gorman J, Moore PL, Bhiman JN, DeKosky BJ, Ernandes MJ, Georgiev IS, Kim HJ, Pancera M, et al. Developmental pathway for potent V1V2-directed HIV-neutralizing antibodies. Nature. 2014;509:55–62. doi: 10.1038/nature13036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosenovic P, von Boehmer L, Escolano A, Jardine J, Freund NT, Gitlin AD, McGuire AT, Kulp DW, Oliveira T, Scharf L, et al. Immunization for HIV-1 Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies in Human Ig Knockin Mice. Cell. 2015;161:1505–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engh RA, H R. Accurate bond and angle parameters for X-ray protein structure refinement. Acta Crystallographica A. 1991;47:392–400. [Google Scholar]

- Garces F, Lee JH, de Val N, Torrents de la Pena A, Kong L, Puchades C, Hua Y, Stanfield RL, Burton DR, Moore JP, et al. Affinity Maturation of a Potent Family of HIV Antibodies Is Primarily Focused on Accommodating or Avoiding Glycans. Immunity. 2015;43:1053–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garces F, Sok D, Kong L, McBride R, Kim HJ, Saye-Francisco KF, Julien JP, Hua Y, Cupo A, Moore JP, et al. Structural evolution of glycan recognition by a family of potent HIV antibodies. Cell. 2014;159:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman J, Soto C, Yang MM, Davenport TM, Guttman M, Bailer RT, Chambers M, Chuang GY, DeKosky BJ, Doria-Rose NA, et al. Structures of HIV-1 Env V1V2 with broadly neutralizing antibodies reveal commonalities that enable vaccine design. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:81–90. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman M, Garcia NK, Cupo A, Matsui T, Julien JP, Sanders RW, Wilson IA, Moore JP, Lee KK. CD4-induced activation in a soluble HIV-1 Env trimer. Structure. 2014;22:974–984. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanover JA, Lennarz WJ. N-Linked glycoprotein assembly. Evidence that oligosaccharide attachment occurs within the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:3600–3604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helle F, Duverlie G, Dubuisson J. The hepatitis C virus glycan shield and evasion of the humoral immune response. Viruses. 2011;3:1909–1932. doi: 10.3390/v3101909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardine J, Julien JP, Menis S, Ota T, Kalyuzhniy O, McGuire A, Sok D, Huang PS, MacPherson S, Jones M, et al. Rational HIV immunogen design to target specific germline B cell receptors. Science. 2013;340:711–716. doi: 10.1126/science.1234150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardine JG, Ota T, Sok D, Pauthner M, Kulp DW, Kalyuzhniy O, Skog PD, Thinnes TC, Bhullar D, Briney B, et al. HIV-1 VACCINES. Priming a broadly neutralizing antibody response to HIV-1 using a germline-targeting immunogen. Science. 2015;349:156–161. doi: 10.1126/science.aac5894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins GM, Rambaut A, Pybus OG, Holmes EC. Rates of molecular evolution in RNA viruses: a quantitative phylogenetic analysis. Journal of molecular evolution. 2002;54:156–165. doi: 10.1007/s00239-001-0064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julien JP, Cupo A, Sok D, Stanfield RL, Lyumkis D, Deller MC, Klasse PJ, Burton DR, Sanders RW, Moore JP, et al. Crystal structure of a soluble cleaved HIV-1 envelope trimer. Science. 2013;342:1477–1483. doi: 10.1126/science.1245625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julien JP, Lee JH, Ozorowski G, Hua Y, Torrents de la Pena A, de Taeye SW, Nieusma T, Cupo A, Yasmeen A, Golabek M, et al. Design and structure of two HIV-1 clade C SOSIP.664 trimers that increase the arsenal of native-like Env immunogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:11947–11952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1507793112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong L, Lee JH, Doores KJ, Murin CD, Julien JP, McBride R, Liu Y, Marozsan A, Cupo A, Klasse PJ, et al. Supersite of immune vulnerability on the glycosylated face of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:796–803. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong L, Wilson IA, Kwong PD. Crystal structure of a fully glycosylated HIV-1 gp120 core reveals a stabilizing role for the glycan at Asn262. Proteins. 2015;83:590–596. doi: 10.1002/prot.24747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornfeld R, Kornfeld S. Assembly of asparagine-linked oligosaccharides. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:631–664. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.003215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon YD, Pancera M, Acharya P, Georgiev IS, Crooks ET, Gorman J, Joyce MG, Guttman M, Ma X, Narpala S, et al. Crystal structure, conformational fixation and entry-related interactions of mature ligand-free HIV-1 Env. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:522–531. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, de Val N, Lyumkis D, Ward AB. Model Building and Refinement of a Natively Glycosylated HIV-1 Env Protein by High-Resolution Cryoelectron Microscopy. Structure. 2015;23:1943–1951. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Ozorowski G, Ward AB. Cryo-EM structure of a native, fully glycosylated, cleaved HIV-1 envelope trimer. Science. 2016;351:1043–1048. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard CK, Spellman MW, Riddle L, Harris RJ, Thomas JN, Gregory TJ. Assignment of intrachain disulfide bonds and characterization of potential glycosylation sites of the type 1 recombinant human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein (gp120) expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10373–10382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyumkis D, Julien JP, de Val N, Cupo A, Potter CS, Klasse PJ, Burton DR, Sanders RW, Moore JP, Carragher B, et al. Cryo-EM structure of a fully glycosylated soluble cleaved HIV-1 envelope trimer. Science. 2013;342:1484–1490. doi: 10.1126/science.1245627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan JS, Pancera M, Carrico C, Gorman J, Julien JP, Khayat R, Louder R, Pejchal R, Sastry M, Dai K, et al. Structure of HIV-1 gp120 V1/V2 domain with broadly neutralizing antibody PG9. Nature. 2011;480:336–343. doi: 10.1038/nature10696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouquet H, Scharf L, Euler Z, Liu Y, Eden C, Scheid JF, Halper-Stromberg A, Gnanapragasam PN, Spencer DI, Seaman MS, et al. Complex-type N-glycan recognition by potent broadly neutralizing HIV antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E3268–3277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217207109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pancera M, Zhou T, Druz A, Georgiev IS, Soto C, Gorman J, Huang J, Acharya P, Chuang GY, Ofek G, et al. Structure and immune recognition of trimeric pre-fusion HIV-1 Env. Nature. 2014;514:455–461. doi: 10.1038/nature13808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pejchal R, Doores KJ, Walker LM, Khayat R, Huang PS, Wang SK, Stanfield RL, Julien JP, Ramos A, Crispin M, et al. A potent and broad neutralizing antibody recognizes and penetrates the HIV glycan shield. Science. 2011;334:1097–1103. doi: 10.1126/science.1213256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard LK, Spencer DI, Royle L, Bonomelli C, Seabright GE, Behrens AJ, Kulp DW, Menis S, Krumm SA, Dunlop DC, et al. Glycan clustering stabilizes the mannose patch of HIV-1 and preserves vulnerability to broadly neutralizing antibodies. Nature communications. 2015;6:7479. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugach P, Ozorowski G, Cupo A, Ringe R, Yasmeen A, de Val N, Derking R, Kim HJ, Korzun J, Golabek M, et al. A native-like SOSIP.664 trimer based on an HIV-1 subtype B env gene. J Virol. 2015;89:3380–3395. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03473-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders RW, Derking R, Cupo A, Julien JP, Yasmeen A, de Val N, Kim HJ, Blattner C, de la Pena AT, Korzun J, et al. A next-generation cleaved, soluble HIV-1 Env Trimer, BG505 SOSIP.664 gp140, expresses multiple epitopes for broadly neutralizing but not non-neutralizing antibodies. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003618. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders RW, van Gils MJ, Derking R, Sok D, Ketas TJ, Burger JA, Ozorowski G, Cupo A, Simonich C, Goo L, et al. HIV-1 VACCINES. HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies induced by native-like envelope trimers. Science. 2015;349:aac4223. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders RW, Venturi M, Schiffner L, Kalyanaraman R, Katinger H, Lloyd KO, Kwong PD, Moore JP. The mannose-dependent epitope for neutralizing antibody 2G12 on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein gp120. J Virol. 2002;76:7293–7305. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.14.7293-7305.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan CN, Pantophlet R, Wormald MR, Ollmann Saphire E, Stanfield R, Wilson IA, Katinger H, Dwek RA, Rudd PM, Burton DR. The broadly neutralizing anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 antibody 2G12 recognizes a cluster of α1-2 mannose residues on the outer face of gp120. J Virol. 2002;76:7306–7321. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.14.7306-7321.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf L, Wang H, Gao H, Chen S, McDowall AW, Bjorkman PJ. Broadly Neutralizing Antibody 8ANC195 Recognizes Closed and Open States of HIV-1 Env. Cell. 2015;162:1379–1390. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommerstein R, Flatz L, Remy MM, Malinge P, Magistrelli G, Fischer N, Sahin M, Bergthaler A, Igonet S, Ter Meulen J, et al. Arenavirus Glycan Shield Promotes Neutralizing Antibody Evasion and Protracted Infection. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005276. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowell SR, Arthur CM, Mehta P, Slanina KA, Blixt O, Leffler H, Smith DF, Cummings RD. Galectin-1, -2, and -3 exhibit differential recognition of sialylated glycans and blood group antigens. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10109–10123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709545200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szakonyi G, Klein MG, Hannan JP, Young KA, Ma RZ, Asokan R, Holers VM, Chen XS. Structure of the Epstein-Barr virus major envelope glycoprotein. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:996–1001. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran EE, Borgnia MJ, Kuybeda O, Schauder DM, Bartesaghi A, Frank GA, Sapiro G, Milne JL, Subramaniam S. Structural mechanism of trimeric HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein activation. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002797. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varki A. Evolutionary forces shaping the Golgi glycosylation machinery: why cell surface glycans are universal to living cells. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2011;3 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardemann H, Yurasov S, Schaefer A, Young JW, Meffre E, Nussenzweig MC. Predominant autoantibody production by early human B cell precursors. Science. 2003;301:1374–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1086907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X, Decker JM, Wang S, Hui H, Kappes JC, Wu X, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Salazar MG, Kilby JM, Saag MS, et al. Antibody neutralization and escape by HIV-1. Nature. 2003;422:307–312. doi: 10.1038/nature01470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X, Ghosh SK, Taylor ME, Johnson VA, Emini EA, Deutsch P, Lifson JD, Bonhoeffer S, Nowak MA, Hahn BH, et al. Viral dynamics in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Nature. 1995;373:117–122. doi: 10.1038/373117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt R, Sodroski J. The HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins: fusogens, antigens, and immunogens. Science. 1998;280:1884–1888. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T, Lynch RM, Chen L, Acharya P, Wu X, Doria-Rose NA, Joyce MG, Lingwood D, Soto C, Bailer RT, et al. Structural Repertoire of HIV-1-Neutralizing Antibodies Targeting the CD4 Supersite in 14 Donors. Cell. 2015;161:1280–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T, Zhu J, Wu X, Moquin S, Zhang B, Acharya P, Georgiev IS, Altae-Tran HR, Chuang GY, Joyce MG, et al. Multidonor analysis reveals structural elements, genetic determinants, and maturation pathway for HIV-1 neutralization by VRC01-class antibodies. Immunity. 2013;39:245–258. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.