Version Changes

Revised. Amendments from Version 1

Version 2 contains the following changes:

In Table I, we give the dilution of NK1.1 antibody as 1/200, not 1/100 as was erroneously stated in version 1.

In "Mice", we discuss the phenotype of the Ncr1-iCre mouse and the steps we have taken to avoid the potential confounding effect of the slightly lower expression of NKp46 that is known to occur in these mice.

In "Discussion", we discuss the previously published data of the fate mapping on Ncr1-iCre mice.

In "Discussion", we acknowledge the limitations of our siLP leukocyte isolation technique.

In Figure 1, we reanalyse the siLP ILC populations using a Lin- CD127+ gating strategy, not Lin- only, as in version 1. Summary graphs now show medians, rather than means, as in version 1.

Abstract

Mouse liver contains both Eomes-dependent conventional natural killer (cNK) cells and Tbet-dependent liver-resident type I innate lymphoid cells (ILC1). In order to better understand the role of ILC1, we attempted to generate mice that would lack liver ILC1, while retaining cNK, by conditional deletion of Tbet in NKp46+ cells. Here we report that the Ncr1 iCreTbx21 fl/fl mouse has a roughly equivalent reduction in both the cNK and ILC1 compartments of the liver, limiting its utility for investigating the relative contributions of these two cell types in disease models. We also describe the phenotype of these mice with respect to NK cells, ILC1 and NKp46 + ILC3 in the spleen and small intestine lamina propria.

Keywords: NK, liver, ILC1, ILC3, NKp46, Tbet, Ncr1, Tbx21

Introduction

Mouse liver contains two NK cell populations. Conventional NK cells (cNK) are defined by their expression of CD49b (DX5) 1, depend on the transcription factor Eomes 2, and circulate freely 1, 3. The other NK cell population, which expresses CD49a 1, depends on the transcription factor Tbet 2, 3 and is unable to leave the liver 1, 3. There is still some dispute over whether these cells should properly be considered liver-resident NK cells or non-NK type I innate lymphoid cells (ILC1) 4, 5: here, we call them “liver ILC1”. In mice, cNK and liver ILC1 are distinct lineages that cannot cross-differentiate 6.

The factors involved in the lineage specification of liver ILC1 are already well-understood, but the function of these cells is not yet clear. They produce IFNγ and TNFα, as expected of ILC1, as well as high levels of GM-CSF 1– 3, 6, but it is unclear whether the production of these cytokines specifically by liver ILC1, as opposed to by cNK, have any role in health and disease. Tissue-resident ILC1 in some other organs have physiological functions 7, 8, so it is also possible that liver ILC1 have some as-yet-undiscovered physiological role.

To answer these questions, we sought to generate mice that would lack liver ILC1 while retaining cNK. Tbet knockout (Tbx21 -/-) mice fulfill these criteria 2, 3, but also have alterations in the T cell compartment that would complicate the analysis. Therefore, we crossed Tbx21 fl/fl onto Ncr1 iCre mice to produce conditional knockout (Ncr1 iCre Tbx21 fl/fl) animals, in which Tbet is lost only in cells expressing Ncr1, whose protein product is the NK cell activating receptor NKp46. Here, we report that these mice have a roughly equivalent reduction in both the cNK and ILC1 compartments of the liver, limiting their utility for investigating the relative contributions of these two cell types in disease models. We also note that the loss of Tbet differentially impacts NKp46 + ILC populations in the spleen, liver and small intestine, suggesting that Ncr1 iCre Tbx21 fl/fl mice could have potential as a tool for understanding how and when Tbet is required for NKp46 + ILC development and trafficking.

Materials and methods

Mice

B6(Cg)-Ncr1 tm1.1(icre)Viv/Orl mice 9 (RRID MGI:5309017; “Ncr1 iCre”) were acquired from the European Mutant Mouse Archive as frozen embryos and rederived in house. B6.129- Tbx21 tm2Srnr/J mice (RRID IMSR_JAX:022741; “Tbx21 fl/fl”) were acquired from the Jackson Laboratory. Ncr1 iCre mice were crossed onto Tbx21 fl/fl and the resultant F1 generation was backcrossed onto Tbx21 fl/fl to produce Ncr1 iCre Tbx21 fl/fl conditional knockouts (n = 6) and Ncr1 WT Tbx21 fl/fl littermate controls (n = 6).

Although we chose to use floxed-only, rather than iCre-only, littermate controls, we do recognise that iCre transgene expression itself can have an effect on phenotype. Ncr1 iCre mice are known to have slightly reduced expression of NKp46 on NK cells, although the total number of NK cells (identified as CD3- NKp46+) in these mice is normal 9. We confirmed these observations in Ncr1 iCre mice, compared to Ncr1 WT littermate controls in our own colony 10. Further, we identify NK cells as Lin- NK1.1+, rather than Lin- NKp46+, to avoid potential confounding effects of reduced NKp46 expression.

Mice were sacrificed between 6.5 and 9 weeks of age, using rising carbon dioxide followed by cervical dislocation. Spleen, liver and intestines were dissected out of each of the 12 mice for cell isolation. Animal husbandry and experimental procedures were performed according to UK Home Office regulations and institute guidelines, under project license 70/8530.

Cell isolation

Dissected livers (a total of 12) were minced finely with opposing scalpel blades. The tissue was collected in HBSS with Ca 2+ Mg 2+ (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) supplemented with 0.01% collagenase IV (Life Technologies) and 0.001% DNase I (Roche, distributed by Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, UK) and passed through a 70 μm cell strainer. The suspension was spun down (500 × g, 4°C, 10 minutes) and the pellet resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies). The cell suspension was then layered over 24% Optiprep (Sigma-Aldrich) and centrifuged without braking (700 × g, RT, 20 minutes). The interface layer was taken and washed in HBSS without Ca 2+ Mg 2+ (Lonza, distributed by VWR, Lutterworth, UK) supplemented with 0.25% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.001% DNase I.

Small intestine lamina propria lymphocytes were isolated using a protocol adapted from Halim and Takei 11. Briefly, dissected intestines (a total of 12) were placed in ice-cold PBS supplemented with 2% fetal calf serum (FCS; Life Technologies) and the bulk of fecal matter removed by flushing the intestines using a syringe and 18G blunt end needle. The intestines were cut longitudinally and vortexed briefly 3x in ice-cold PBS/2% FCS to remove residual fecal matter. Tissue sections were incubated in PBS supplemented with 1 nM EDTA (shaking at 120 rpm, 37°C, 20 minutes) followed by 3x washes with ice-cold PBS/2% FCS before being minced finely with opposing scalpel blades. The homogenized tissue was digested in DMEM (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% FCS, 50 µM 2-mercaptoethanol (Life Technologies), 250 U/mL collagenase IV and 50 U/mL DNase I (shaking at 120 rpm, 37°C, 20 minutes) and passed through a 70µm cell strainer. The cell suspension was centrifuged (400 × g, 4°C, 5 minutes) and the cell pellet resuspended in 40% Percoll (GE Healthcare, distributed by Sigma-Aldrich) before centrifugation without braking (600 × g, 4°C, 10 minutes). The resultant pellet was washed in PBS/2% FCS (400 × g, 4°C, 5 minutes).

Dissected spleens (a total of 12) were passed through a 40 µm cell strainer. Red blood cells were lysed by 5 minute incubation in ACK lysing buffer (Life Technologies).

Flow cytometry

The antibodies used are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1. Antibodies used for flow cytometry analysis.

| Antibody | Clonality | Fluorophore | Dilution | Host

Animal |

Manufacturer | Catalog # | RRID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD3 | 17A2 | FITC | 1/200 | Rat | Biolegend | 100203 | AB_312660 |

| CD8α | 53-6.7 | FITC | 1/200 | Rat | Biolegend | 100705 | AB_312744 |

| CD19 | 6D5 | FITC | 1/200 | Rat | Biolegend | 115505 | AB_313640 |

| Gr1 | RB6-8C5 | FITC | 1/200 | Rat | Biolegend | 108405 | AB_313370 |

| NK1.1 | PK136 | APC-eFluor 780 | 1/200 | Mouse | eBioscience | 47-5941 | AB_2637449 |

| CD45 | 30-F11 | Brilliant Violet 510 | 1/200 | Rat | Biolegend | 103137 | AB_2561392 |

| CD49a | Ha31/8 | Alexa Fluor 647 | 1/100 | Hamster | BD Biosciences | 562113 | AB_11153312 |

| CD49b | DX5 | PerCP-eFluor 710 | 1/200 | Rat | eBioscience | 46-5971 | AB_11149865 |

| CD127 | A7R34 | PE | 1/100 | Rat | eBioscience | 17-1271 | AB_469435 |

| NKp46 | 29A1.4 | PerCP-eFluor 710 | 1/50 | Rat | eBioscience | 46-3351 | AB_1834441 |

| Eomes | Dan11mag | PE-eFluor 610 | 1/100 | Rat | eBioscience | 61-4875 | AB_2574614 |

| Eomes | Dan11mag | PE-Cyanine7 | 1/100 | Rat | eBioscience | 25-4875 | AB_2573453 |

| Tbet | eBio4B10 | eFluor 660 | 1/100 | Mouse | eBioscience | 50-5825 | AB_10596655 |

| Tbet | eBio4B10 | PE-Cyanine7 | 1/100 | Mouse | eBioscience | 25-5825 | AB_11041809 |

| RORγt | Q31-378 | PE-CF594 | 1/100 | Mouse | BD Biosciences | 562684 | AB_2651150 |

The lineage cocktail consisted of CD3, CD8α, CD19 and Gr1 (Biolegend, London, UK). Dead cells were excluded using fixable viability dye eFluor 450 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) (4°C, 15 minutes). Surface staining was carried out in PBS supplemented with 1% FCS (4°C, 15 minutes). Intracellular staining was carried out using Human FoxP3 Buffer (BD Biosciences, Oxford, UK), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Data were acquired on an LSRFortessa II (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo v.X.0.7 (RRID SCR_008520; Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA).

Statistical analysis

Groups were compared using Mann-Whitney U Tests. Analysis was carried out using Vassarstats (RRID SCR_010263).

Results

See Figure 1.

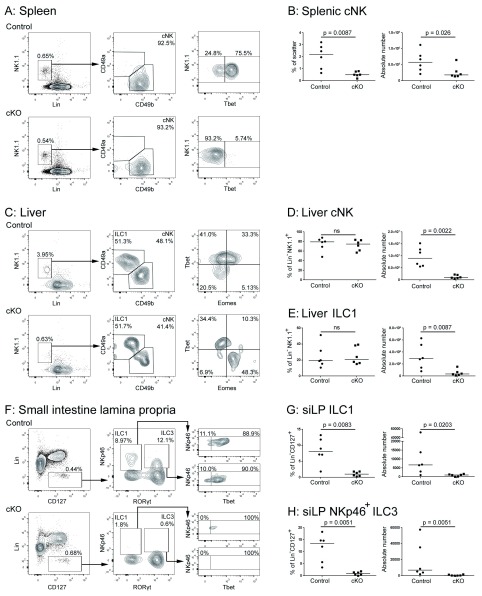

Figure 1. Characterisation of innate lymphoid cell (ILC) populations in Ncr1 iCre Tbx21 fl/fl mice.

Representative flow cytometry of leukocytes isolated from the ( A) spleen, ( C) liver and ( F) small intestine lamina propria (siLP) of Ncr1 WT Tbx21 fl/fl (“control”) and Ncr1 iCre Tbx21 fl/fl (“cKO”) mice. Gated by scatter and on live, CD45+ cells. Summary data for cell frequency and absolute number in ( B) spleen, ( D, E) liver and ( G, H) siLP. Each point represents data from a single mouse (n = 6 per group), bars represent the medians and p values were determined using a Mann-Whitney U Test.

Discussion

We observed a modest (~4-fold) reduction in splenic NK (defined as Lin- NK1.1+) in the Ncr1 iCre Tbx21 fl/fl conditional knockouts, compared to Ncr1 WT Tbx21 fl/fl littermate controls ( Figures 1A and B). This is comparable to the 2- to 4-fold reduction in splenic cNK that has previously been reported in Tbx21 knockout, compared to wild-type, mice 2, 3, 12 and is likely to be a result of reduced survival 12 or bone marrow egress 13 of NK cells in the absence of Tbet.

We also observed a reduction in the absolute number of cNK (defined as Lin- NK1.1+ CD49b+) in the liver ( Figures 1C and D). We had expected that this might be similar to the reduction of cNK in the spleen, but, at ~10-fold, it was more pronounced, potentially pointing towards a differential requirement for Tbet in cNK survival in or recruitment to the liver, compared to the spleen. Although the absolute number of liver ILC1 (defined as Lin- NK1.1+ CD49a+) was also reduced (~10-fold), a substantial residual population was present ( Figures 1C and E), in contrast to the Tbx21 knockout, in which these cells are almost completely eliminated 2, 3. Unlike the cNK in the conditional knockout, the residual liver ILC1 all expressed Tbet ( Figure 1C). This supports the proposal that Tbet is absolutely required for continued survival of these cells 2, since no ILC1 in which Tbet was not expressed persisted. We were surprised to note that Tbx21 excision seemed to be less efficient in liver ILC1 than cNK, because fate mapping of iCre activity under the Ncr1 promoter using R26R eYFP has previously shown that iCre activity is higher in ILC1 than cNK 9. Given the absolute requirement of Tbet for the survival of liver ILC1 2, 3, it seems likely that even if the excision failed in only a few cells, these would have benefited from a selection advantage that might have resulted in their expansion. Whatever the cause of the unexpectedly large reduction in cNK and the unexpectedly small reduction in ILC1, the finding that both of these were reduced by equivalent amounts in the liver of conditional knockouts compared to controls limits the utility of Ncr1 iCre Tbx21 fl/fl mice for dissecting the relative contributions of the two cell types in disease models.

Rankin et al. have also recently generated Ncr1 iCre Tbx21 fl/fl mice, and report a severe reduction in ILC1 (defined in their paper as Lin- RORγt+ NKp46-) and NKp46 + ILC3 (defined as Lin- RORγt+ NKp46+) in the small intestine lamina propria 14. We were able to isolate fewer Lin- CD127+ ILC from the small intestine than has previously been reported, but even with this sub-optimal cell isolation procedure we made findings similar to those of Rankin et al., observing a ~6-fold reduction in ILC1 (defined here as Lin- CD127+ RORγt+ NKp46-) and a ~24-fold reduction in NKp46+ ILC3 (defined here as Lin- CD127+ RORγt+ NKp46+) compared to littermate controls ( Figures 1F–H).

In summary, conditional deletion of Tbet in NKp46 + cells, where Tbx21 excision has been successful, differentially affects cNK and ILC1 in different organs. In the liver, a residual population of ILC1, in which Tbx21 has not been excised, persists. We conclude that the Ncr1 iCre Tbx21 fl/fl mouse is therefore unlikely to be useful for investigating the relative contributions of liver cNK and ILC1 to pathogenesis in disease models, but could still have potential as a tool for understanding how and when Tbet is required for the development and trafficking of NKp46 + ILC.

Data availability

The data referenced by this article are under copyright with the following copyright statement: Copyright: © 2017 Cuff AO and Male V

Data is available at DOI, 10.17605/OSF.IO/GDMWT 10.

Funding Statement

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust [105677] (Royal Society and Wellcome Trust Sir Henry Dale Fellowship).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 2; referees: 2 approved]

References

- 1. Peng H, Jiang X, Chen Y, et al. : Liver-resident NK cells confer adaptive immunity in skin-contact inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(4):1444–1456. 10.1172/JCI66381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gordon SM, Chaix J, Rupp LJ, et al. : The transcription factors T-bet and Eomes control key checkpoints of natural killer cell maturation. Immunity. 2012;36(1):55–67. 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sojka DK, Plougastel-Douglas B, Yang L, et al. : Tissue-resident natural killer (NK) cells are cell lineages distinct from thymic and conventional splenic NK cells. eLife. 2014;3:e01659. 10.7554/eLife.01659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peng H, Tian Z: Re-examining the origin and function of liver-resident NK cells. Trends Immunol. 2015;36(5):293–299. 10.1016/j.it.2015.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tang L, Peng H, Zhou J, et al. : Differential phenotypic and functional properties of liver-resident NK cells and mucosal ILC1s. J Autoimmun. 2016;67:29–35. 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Daussy C, Faure F, Mayol K, et al. : T-bet and Eomes instruct the development of two distinct natural killer cell lineages in the liver and in the bone marrow. J Exp Med. 2014;211(3):563–577. 10.1084/jem.20131560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sojka DK, Tian Z, Yokoyama WM: Tissue-resident natural killer cells and their potential diversity. Semin Immunol. 2014;26(2):127–131. 10.1016/j.smim.2014.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Melsen JE, Lugthart G, Lankester AC, et al. : Human circulating and tissue-resident CD56 (bright) natural killer cell populations. Front Immunol. 2016;7:262. 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Narni-Mancinelli E, Chaix J, Fenis A, et al. : Fate mapping analysis of lymphoid cells expressing the NKp46 cell surface receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(45):18324–18329. 10.1073/pnas.1112064108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Male V: “Conventional NK Cells and ILC1 Are Partially Ablated in the Livers of Ncr1iCreTbx21fl/fl Mice.” Open Science Framework. 2017. Data Source [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Halim TY, Takei F: Isolation and characterization of mouse innate lymphoid cells. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2014;106:3.25.1–13. 10.1002/0471142735.im0325s106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Townsend MJ, Weinmann AS, Matsuda JL, et al. : T-bet regulates the terminal maturation and homeostasis of NK and Valpha14i NKT cells. Immunity. 2004;20(4):477–494. 10.1016/S1074-7613(04)00076-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jenne CN, Enders A, Rivera R, et al. : T-bet-dependent S1P5 expression in NK cells promotes egress from lymph nodes and bone marrow. J Exp Med. 2009;206(11):2469–2481. 10.1084/jem.20090525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rankin LC, Girard-Madoux MJ, Seillet C, et al. : Complementarity and redundancy of IL-22-producing innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(2):179–186. 10.1038/ni.3332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]