Abstract

Applying a robust human rights framework would change thinking and decision-making in efforts to achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC), and advance efforts to promote women’s, children’s, and adolescents’ health in East Africa, which is a priority under the Sustainable Development Agenda. Nevertheless, there is a gap between global rhetoric of human rights and ongoing health reform efforts. This debate article seeks to fill part of that gap by setting out principles of human rights-based approaches (HRBAs), and then applying those principles to questions that countries undertaking efforts toward UHC and promoting women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health, will need to face, focusing in particular on ensuring enabling legal and policy frameworks, establishing fair financing; priority-setting processes, and meaningful oversight and accountability mechanisms. In a region where democratic institutions are notoriously weak, we argue that the explicit application of a meaningful human rights framework could enhance equity, participation and accountability, and in turn the democratic legitimacy of health reform initiatives being undertaken in the region.

Keywords: Universal Health Coverage, East Africa, Human rights, Health systems, Fair financing, Priority-setting, Accountability, Participation

Background

Lagging efforts to improve women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health have been a particular focus of development efforts in East Africa.1 The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) contain several health-related targets, of which promoting women’s and children’s health as well as Universal Health Care (UHC) attainment are critical aims [1]. The inclusion of UHC within the SDGs is a remarkable shift from previous health promotion efforts and has gained global support including from the World Health Organization (WHO) [2, 3]. The SDG targets are further elaborated upon in the 2015 UN Secretary General’s Global Strategy on Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health (“Global Strategy”), which provides a roadmap to advancing the health of women, children and adolescents. Together, the SDGs and the Global Strategy will inevitably deeply influence financing, policy-making, and programming for efforts to achieve UHC, and promote the health of women, children and adolescents in East Africa. The Global Strategy makes explicit mention of human rights and there has been substantial rhetoric from global leaders [4, 5] about the need to use human rights-based approaches, including recognition of the right to health, to achieve the Global Strategy as well as the target related to UHC. Yet, there continues to be a gap between this rhetoric and what occurs on the ground. This article will focus on a few issues that countries will necessarily face in the context of advancing the Global Strategy and achieving UHC, and in signaling how applying human rights principles has the potential to enhance equity, accountability and participation.

The right to health and human rights principles are defined in international human rights law and are also enshrined in treaties that the countries of the East African Community (EAC)2 have ratified, and Kenya has also embedded in its 2010 constitution [6–11]. The right to health “requires that health-care goods, services and facilities be available in adequate numbers; financially and geographically accessible, as well as accessible on the basis of non-discrimination; acceptable, that is, respectful of the culture of individuals, minorities, peoples and communities and sensitive to gender and life-cycle requirements; and of good quality” [7]. UHC is a crucial aspect of realizing the right to health, but “not all paths to universal health coverage are consistent with human rights requirements” [5, 7, 10, 12].

The importance of human rights is increasingly cited in relation to health in the development agenda [7]. The UN Secretary General’s Global Strategy on Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health (Global Strategy), a strategy to realizing the right to health for women, children and adolescents, is explicitly rooted in a human rights framework [13]. The 2016 report of the UN Secretary General’s Independent Accountability Panel (IAP) on the Global Strategy, created to ensure accountable implementation of the Global Strategy and on which one of these authors sits (self-identifying reference), even sets out an accountability framework based on human rights law [14].3 Yet, there remains a disconnect between this global rhetoric and the national realities of health reform initiatives in the region.

A human rights-based approach (HRBA) goes beyond the right to health and utilizes “human rights standards contained in, and principles derived from, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments” to guide analysis and policy, legislation, programming, and evaluation and monitoring [8, 9, 15–18]. “Among [the] human rights principles are: universality and inalienability; indivisibility; interdependence and inter-relatedness; non-discrimination and equality; participation and inclusion; accountability and the rule of law” [8, 9, 15, 16]. A human rights-based approach also “contributes to the development of the capacities of ‘duty-bearers’ to meet their obligations and/or of ‘rights-holders’ to claim their rights” [8, 9, 15–18]. As Sanghera et al. explain in respect of the new Global Strategy: “A human rights based approach is based on accountability and on empowering women, children, and adolescents to claim their rights and participate in decision making, and it covers the interrelated determinants of health and wellbeing. [It] promotes holistic responses, rather than fragmented strategies, and requires attention to the health needs of marginalised and vulnerable populations [13].” In this debate article, we set out how meaningfully applying these principles of human rights would change thinking and decision-making in efforts to achieve UHC and other targets related to the Global Strategy in East Africa in four specific domains: ensuring enabling legal and policy frameworks; establishing fair financing; democratizing priority-setting processes; and strengthening meaningful oversight and accountability [19, 20]. These four domains are derived from international human rights law relating specifically to the right to health [8–11], principles of international human rights law more broadly [8, 9, 15, 16], interpretative guidance on aspects of the right to health [7, 21], and inter-governmental guidance on applying a human rights-based approach to policy, legislation and programming [16]. In a region where democratic institutions are notoriously weak, we argue that the application of a robustly understood human rights based approach (HRBA) could enhance equity, transparency and accountability, and in turn the legitimacy of health reform initiatives being undertaken in the region (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Four proposed domains

Context

In addition to having fragile democratic institutions, the East African region has some of the worst health statistics in the world, as well as some of the highest rates of income poverty [22, 23]. For example, WHO estimates maternal mortality ratios (MMRs), which reflect the functioning of health systems as well as the status of women in society, at 710 per 100,000 live births for Burundi, Kenya at 510, Rwanda at 290, Uganda at 343 and Tanzania at 398, compared to the global average of 221 in 2015 [24]. The interventions that might address these elevated MMRs, including skilled birth attendance (SBA), remain low in across the region, and as low as 43% in Kenya [25]. Furthermore, not only do other basic indicators of health system functioning such as infant mortality rates also remain high, and rates of non-communicable diseases are exponentially growing in the region while health systems struggle to address basic health conditions [26, 27]. Underpinning these dismal statistics and contributing to unmet population needs is the lack of a skilled, trained health care workforce that enjoys decent work standards and basic labor protections. The region experiences the most severe needs-based shortage of health care workers in the world, with only 1.9 total health care workers for every 1000 population [28]. WHO has forecasted this shortage to worsen between 2013 and 2030 [13].

As elsewhere, health systems in East Africa reflect historical and economic patterns of privilege, as well as social values [29]. Formal health systems in the region were established as part of colonial governance, with an enormous role of parochial institutions delivering health care as charity [30, 31]. These institutions still provide over 50% of care in the region [32]. Beginning in the 1980s and 1990’s, HIV/AIDS took an enormous toll on the region [33]. Vertical programs such as the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) or the Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, as well as additional vertical programs targeted at other Millennium Development Goal (MDG) indicators, such as skilled birth attendance, did little to improve overall systems’ functioning, given that background conditions, including infrastructure and referral networks, were deeply unequal and fragile [34]. Along with narrow, targeted programs, the MDGs encouraged a technocratic, “apolitical” view of development, focused on efficiency of narrow outcome measures [35, 36]. Moreover, by 2010, the UN acknowledged that there was a lack of accountability in many countries’ efforts to meet MDGs 4 and 5, relating to maternal and child health, respectively, and the UN Secretary General launched the first Global Strategy on Women’s and Children’s Health, which was then expanded and made more robust in 2015 with the second Global Strategy on Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health to accompany the SDGs [37–39].

East Africa is rightly a focus for development partners concerned that weak health and demographic policies will hinder possibilities for economic growth. Health is also a priority area for regional cooperation among the five member states of the EAC. However, we argue here that technocratic approaches alone are unlikely to shift the underlying political determinants of health that hamper both the region’s development, and the possibility for the health system to perform the functions it should in the construction of inclusive citizenship [40]. The rest of this article sets out four ways in which applying a robust human rights framework would change thinking and decision-making about health reform on the path to UHC, and in turn in advancing women’s, children’s and adolescent’s health.

Enabling legal and policy frameworks

Health systems are inexorably governed by legal and policy frameworks, despite too little attention being paid to these in conventional “systems thinking” [41, 42]. Indeed, legal frameworks function as social—and political—determinants of health more broadly by establishing the parameters of people’s entitlements, the responsibilities of different levels of government and the regulation of private actors, among other things. Laws structure the institutions that provide goods and services. Laws and policies also establish social norms that invariably affect health (e.g., criminalization of sodomy or IV drug use), which reflect narratives of equal concern and respect, or do not [20].

The new Global Strategy explicitly calls for multi-sectoral approaches in planning [43]. In that context, applying an HRBA first makes the legitimacy of the normative framework for health directly relevant to health reforms. An HRBA requires situational analyses with respect not just to epidemiological or demographic conditions, but also laws, when health sector reforms are undertaken or health policies/directives are adopted. Second, HRBAs provide criteria, including fundamental commitments to dignity (e.g., bodily integrity and informed consent) and equality/non-discrimination by which to assess proposed or existing laws in relation to health.

The 2015 High Court of Kenya’s judgment on the constitutionality of the so-called “Uhuru’s HIV List” is a clear example of how the application of human rights principles could enhance the validity of laws and policies adopted in relation to health. In that case, a directive was issued by the President Uhuru Kenyatta to all County Commissioners to collect data on all school-going children living with HIV/AIDS. The Court found that the directive violated children’s rights to privacy, among other things. The Court ruled that the directive and actions taken under its direction violated the Constitution, but refrained from mandating the government to adopt a certain policy or protocols that met specific criteria [44]. Moreover, as the directive had begun to be implemented, there were already children who had been harmed, and for these children the court ruled that the government must de-identify the data in such a way so that it did not link a child to their HIV status.

Such harms can be avoided when the validity of legal frameworks are considered from the outset of policymaking. For example, the development of the East African Community HIV and AIDS Prevention and Management Act of 2015 provides an illustration of a legal framework that was developed using an HRBA and which seeks to promote the rights of persons living with or affected by HIV, even overriding national laws that contain discriminatory clauses [45]. The inclusive and democratic process for developing the law, which took 7 years of extensive consultations with stakeholders, including persons living with HIV, sex workers, men who have sex with men (MSM), drug users, health care workers, parliamentarians, civil society groups and religious leaders, not only exemplifies how HRBAs promote concern for and empower marginalized communities. From the perspective of health policy and governance, the process was critical to both the law’s legitimacy as well as that of the programs that were launched within its parameters.

Fair financing

The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which interprets the core formulation of the right to health under international law, calls for national governments to ensure that health facilities, goods, and services are, among other things, physically accessible and affordable on the basis of non-discrimination [8]. As both scholars and WHO Task Forces have pointed out, non-discrimination and equity in access to services requires equity in financing [46, 47]. According to WHO, “UHC is centrally concerned with both access to services and financial risk protection… progress toward UHC therefore requires reform of the health financing system” [47].

Indeed, it is now widely accepted that equity in access, as required under the right to health, can only be met if financing is equitable [7, 8, 20, 48, 49]. There is a governmental obligation not to treat people in accordance to their ability to pay, but in accordance to the needs that must be met to enable lives of dignity [47, 48, 50]. The UN Committee that provides interpretations the right to health under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR and ICESCR, respectively) has noted that equity demands that poorer households should not be disproportionately burdened with health expenses as compared to richer households [8]. The UN Special Rapporteur on the right to health explains, “Universal health coverage consistent with the right to health requires establishing a financing system that is equitable and pays special attention to the poor and others unable to pay for health care services, such as children and adolescents” [7].

Although all needs cannot be met in any health system, and many cannot be met immediately but only progressively in the contexts of East Africa, defining the contours of what the government is responsible for providing as an entitlement—as part of a right to health --calls for a fair process for meeting population health needs that does not rely solely on market mechanisms that would disproportionately burden and exclude the poor [47, 48, 51]. Indeed, a robustly understood HRBA requires substantial solidarity in financing, which in turn requires redistribution to level the playing field, and given their importance in the context of East Africa, effective regulation of private actors, as called for by CESCR: “States parties should … ensure that the private business sector … considers the importance of the right to health in pursuing their activities” [8].

Establishing fair financing would require tectonic shifts to the health reforms being undertaken in the region. As it stands, given the extremely low tax base common throughout the region, relying on preexisting employment schemes would undermine efforts at fair financing. In the EAC, only 36% of health care funding comes from domestic sources composed of 20% from the member states and 16% from private insurance. The remaining 63% of funding comprises 28% from out-of-pocket spending, and 35% from external sources [52].

The risk pooling pre-payment schemes that are being designed as statutory deductions for those who are registered with national health insurance schemes, heavily target those in formal employment while making little effort to address individuals employed in the informal sector [53]. Yet, in Uganda an estimated 30% of workers are in the formal sector [54]; in Kenya only an estimated 18% of people in the labor force are in the formal sector [55]; and in Rwanda an estimated 33% of employees are in the formal sector [56]. Thus, access to care for those employees—and for their children and dependents—is based not on need but on one family member’s employment status and insurance coverage, a situation which has been found to contravene constitutional and other commitments to equality by courts as well as government policy makers in other regions [50, 57].

In terms of external sources, the Global Financing Facility (GFF) has provided a $30 million grant for Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health (RMNCAH) to Uganda, constituting 7% of total government health spending [58], a $40 million grant for RMNCAH to Kenya [59], and a $40 million grant for RMNCAH to Tanzania [60]. But it should be noted that targeted aid efforts do not obviate the need for more robust and equitable domestic financing. Further, in the past aid aimed at abolishing users’ fees to expand maternal-child services for indigent patients in several East African countries have produced perverse effects in practice when policies have not been aligned with programs, and where health facilities are often not well-equipped or staffed to deal with the increase in number of patients, compromising the quality of services rendered [61]. For example, in 2015, the High Court of Kenya addressed discrimination and abuses experienced by women in public maternity hospitals, and ordered compensation for two women who were unconstitutionally detained at the Pumwani Maternity Hospital for inability to pay despite the policy of free maternal care [62].

Indeed, there is a substantial risk in East Africa that UHC may devolve into coverage that does not translate into equal effective access to care in practice, unless greater attention is paid to fair financing. Adopting an HRBA provides principles to guide such a process.

Priority setting: process and criteria matter

To advance the Global Strategy, and to achieve UHC, which is SDG Goal 3.8, countries in the region, as elsewhere, will need to make important choices. While the right to health requires states to pursue the highest attainable standard of health, it does not eliminate the need for states, rich and poor, to make choices about how to finance and what to finance within the health system. The right to health does require the process and criteria for priority setting to be equitable, non-discriminatory, participatory, accountable and transparent [8, 20].

First, states need to define which services they consider as priorities, which involves difficult trade-offs. For example, priority may be placed upon cost-effectiveness of interventions, but also may target severe diseases or disadvantaged populations, and should provide financial risk protection from the impoverishing impact of ill-health. Countries will need to establish such a list of priority services, and periodically update it every few years [47].

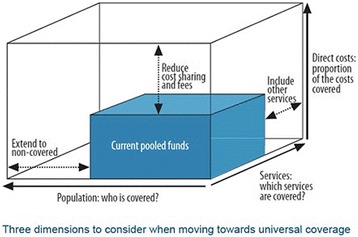

Second, countries in the region will need to make choices regarding the implementation of priorities, as illustrated in Fig. 2 [63]. Governments have limited pooled funds for health care, so in moving towards UHC governments will have to consider 1) whether to expand coverage to those currently not covered, 2) what proportion of the costs to cover, and 3) which services to cover.

Fig. 2.

Universal coverage - three dimensions

Here, governments can choose to include more priority services in the essential package, or expand coverage of existing priority services to non-covered populations, or reduce out-of-pocket payments for existing priority services. Embracing and pursuing the Global Strategy does not obviate the need for such trade-offs. For example, countries may need to choose between increasing the coverage of skilled birth attendance to all rural populations, or reducing copayments for antibiotic treatment of children with pneumonia. “The option they choose to do first may have far-reaching consequences for the level and distribution of health in the country, and of financial risk protection. Countries need to address these decisions on a recurrent, ongoing, basis” [64].

If health is considered a right, either under the Constitution or legislation, and the health system is understood as part of democratic governance in an HRBA, these questions are not merely technical ones, but require ensuring that citizens are active participants in the decisions that affect their health, including the definition of the contours of what their right to health includes [7]. Thus, to the extent possible, priority setting cannot be done merely on the basis of credible clinical and cost-effectiveness evidence, but must entail a legitimate democratic process. [8, 51]. As stated in the MDG Task Force on Child and Maternal Health, “Health claims—claims of entitlement to healthcare and enabling conditions—are assets of citizenship. Their effective assertion and vindication through the operation of the health system helps build a human rights culture and a stronger, more democratic society” [65].

Yet, governments in the East African region have not demonstrated openness to meaningful citizen participation in setting priorities UHC. For example, REACT, an EU funded five-year intervention that described and evaluated district-level priority-setting upon in one district each in Tanzania, Kenya and Zambia found “a high need to promote new approaches to priority-setting processes that take into account” “a broader range of relevant values, such as trust, equity, accountability and fairness” [66].

As scholars have pointed out at the global level, “sexual and reproductive rights may be systematically neglected in many essential service packages” [67]. But even those exercises intended to set priorities under the Global Strategy in the region have not been subject to robust participation. For example, “consensus-building exercises” in Uganda appear to have presented “consultations” on a predetermined package of “low-cost” interventions including voucher projects and results-based financing, which allowed the government to “complete key strategies in time” for the GFF investment deadline [68]. Similarly, Tanzania has adopted priorities without meaningful citizen participation [69]. Yet, such decisions as placing priority upon the “development of a systematic scale-up plan for long-acting and permanent family planning services to ensure marginalized groups are reached” affect people’s most intimate decisions about their life plans and reproductive lives, and therefore their dignity. In an HRBA, such priority-setting would require inclusion of the voices of people affected, including marginalized and vulnerable populations, such as people living with HIV, and persons with disabilities.

Admittedly, incorporating processes that enable people to meaningfully participate in some of the ranking and criteria for priorities (not choosing individual services) is time-consuming, expensive and extremely challenging, given information asymmetries and diverse interests in the health sector. Indeed, “governments by discussion” are never easy, as philosophers from the Greeks to John Stuart Mill realized [70, 71]. Yet, these processes are both necessary from a principled approach to human rights, and are more likely to result in decisions that are more socially legitimate. The WHO has reported that participation of women in the design, implementation, management and evaluation of community health systems is associated with “improved health and health-related outcomes,” including significant improvements in mortality rates for children and positive outcomes for contraceptive use and service uptake [72].

Small-scale examples from the region show the transformative potential of meaningful participation in HRBAs. For example, in 2015, the Commission for the Implementation of the Constitution in Kenya conducted a participatory research and implementation project that entailed multi-stakeholder workshops, in-depth surveys with users, and capacity-strengthening with providers over months. It resulted in revised service charters in the three counties, greater capacity of providers as well as awareness of patients’ rights, and a blueprint for further steps based on the granular realities of each specific context [73].

Oversight mechanisms: from monitoring and review to meaningful accountability

Accountability is perhaps the sine qua non of an HRBA [13, 74], and what sets it apart from other approaches to global health focused on equity. Human rights identifies health system users as active claims-holders and governments and other actors as duty-bearers. Monitoring efforts to assess effectiveness, with reliable and, to the extent possible, disaggregated data (to reveal disparities, and potential discrimination) is essential to enabling accountability. Yet monitoring data alone is insufficient; oversight mechanisms are needed to regulate power imbalances that plague the sector.

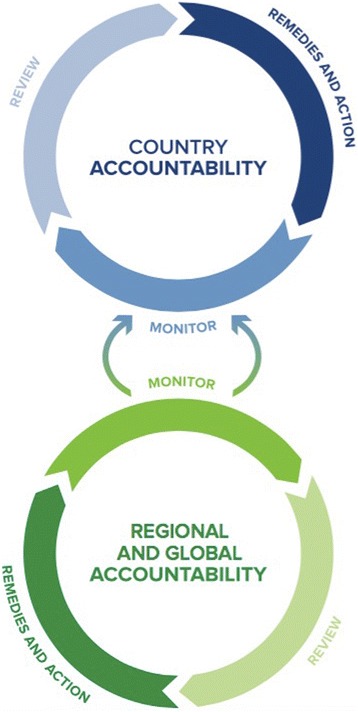

The accountability framework adopted by the UN Secretary General’s Independent Accountability Panel for the Global Strategy illustrates how monitoring, review, action, and remedies all form part of an HRBA to accountability, as shown in Fig. 3 [14]. Drawing from authoritative interpretations of international law [8, 9, 75], the monitor, review, action and remedy framework operates at both the national level, but also at the regional or international level [14].

Fig. 3.

IAP accountability framework

In addition to monitoring data, the IAP framework calls for a process of continuous review at both the local and global levels, by actors ranging from independent agencies to civil society. It also calls for oversight institutions to act in response to the review mechanisms by enforcing sanctions and providing incentives dependent upon compliance. Finally, it calls for remedies in the form of political action, social engagement, and judicial enforcement of health-related rights [76]. These actors, including parliamentary bodies, independent judiciaries and national human rights institutions with appropriate mandates and capacity, all can and should play key roles in ensuring that the health system is enshrining the normative commitments to equal dignity set out in international human rights law and national constitutions—in both law and practice [76].

In particular, independent judiciaries can play important roles in ensuring the values reflected in health systems are consistent with democratic commitments, and that health systems are understood as subject to the rule of law [20, 77]. Courts in the region are indeed already playing this role to some extent, which can re-orient norms and policies. For example, as mentioned above, a 2015 High Court of Kenya’s judgment ordered an end to discrimination and abuses experienced by women in public maternity hospitals, and compensation for two women who were unconstitutionally detained at the Pumwani Maternity Hospital for inability to pay [62]. In a 2016 case in Uganda, concerning the failure of the Mulago National Referral Hospital to protect mothers from having their babies stolen, the High Court of Uganda ordered access to civil society to monitor implementation of orders and make reports to the Court [78]. In a 2011 case in the Constitutional Court of Uganda, the court found that access to obstetric care services and human resources for maternal health constitute a part of the right to life guaranteed in Article 22 of Uganda’s Constitution [79].

Such remedies should not be confused with addressing malpractice; they are institutional remedies that are essential to not merely sanction violations but to prevent future abuses, ensure fidelity to constitutional and international norms, and subject health policies and programs to independent scrutiny of reasonableness. Requiring governments to publicly justify policies, and whether they are implemented appropriately, is as essential in health systems as in any other area of democracy [80].

Conclusion

There is increasing rhetoric about the importance of human rights to achieving the Global Strategy and the SDGs relating to health at global levels. Governments in East Africa are also acknowledging the link between health and rights [81]. Yet there continues to be a gap between this rhetoric and the reality of what applying human rights to efforts to achieve UHC would entail, and there is a real risk that the increased rhetoric of human rights replaces meaningful rights-based action.

We have argued here that rights are fundamentally about the regulation of power, and to understand health as a right is to understand that patterns of health and ill-health require democratic controls over power as they do in other arenas. Within the scope of this article it has not been possible to consider every aspect of HRBAs but specifically, we have argued that legal and policy frameworks play a critical role in establishing parameters for people to exercise their health-related rights and should be incorporated into multi-sectoral planning and situational analyses. Second, if health is a right, fair financing needs to divorce meeting essential health needs necessary for people’s dignity from ability to pay, which will require substantial reorientation of financing plans for the region. Third, meaningful participation in an HRBA requires stakeholders to be involved in voicing their needs when priorities are set, and the contours of essential packages and health reforms are undertaken. Finally, oversight mechanisms should include not only monitoring and evaluation within the health sector, but also meaningful remedies that call for greater public justification and accountability with respect to fundamental normative commitments as well as alignment of programmatic practice with policies and laws.

The EAC’s “Open Health Initiative”—aimed at harmonizing the health systems of member countries to promote UHC—provides an ideal opportunity for policy makers to create broader dialogues about the role of health systems in fostering better democratic governance [82, 83]. Policy makers at the EAC and national level, together with development partners, can enhance the equity, transparency and accountability of ongoing health reforms, as well as their democratic legitimacy, by taking human rights principles seriously. But ultimately conquering health rights and constructing inclusive, fair health systems will require ongoing struggle and vigilance by civil society, just as it does elsewhere.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the collaboration with the Christian Michelsen Institute on the project “Rights-based Approaches to Health Service Delivery.” Alicia Ely Yamin is deeply appreciative of the invaluable research assistance provided by Angela Duger, Research Associate at the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law, as well as assistance from Eric Friedman and Brenna Gautam on an earlier version.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CESCR

Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

- EAC

East African Community

- GFF

Global Financing Facility

- HRBA

Human rights-based approach

- IAP

International Accountability Panel

- ICESCR

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

- MDG

Millennium Development Goal

- MMR

Maternal mortality ratio

- MSM

Men who have sex with men

- PEPFAR

President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief

- RMNCAH

Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health

- SBA

Skilled birth attendance

- SDG

Sustainable Development Goal

- UHC

Universal Health Coverage

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

AEY drafted and revised this article. AM provided information for and contributed to the draft. Both authors have read and approved the final version of this article.

Authors’ information

Alicia Ely Yamin: Visiting Professor of Law and Director, Health and Human Rights Initiative, O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law, Georgetown University Law Center; Adjunct Lecturer on Law and Global Heath, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. Panelist, UN Secretary General’s Independent Accountability Panel for the Global Strategy (EWEC). NOTE: All opinions expressed are personal and do not necessarily reflect those of the IAP.

Allan Maleche: Human rights lawyer, Executive Director of KELIN, Chair Implementer Group of the Global Fund & Alternate Board Member of the developing country NGO constituency of the Global Fund Board.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

East Africa is a geographically defined region comprised of up to 20 states located on the East coast of Africa, including at minimum the East African Community states.

The East African Community is a regional intergovernmental organization comprised of six member states: Tanzania, Uganda, Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda and South Sudan.

All opinions expressed in this article are personal and do not reflect official positions of the IAP.

Contributor Information

Alicia Ely Yamin, Email: aey7@law.georgetown.edu.

Allan Maleche, Email: amaleche@kelinkenya.org.

References

- 1.General Assembly of the United Nations. Resolution 70/1. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. U.N. Doc. A/RES/70/1. UN. 2015.

- 2.World Health Organization. Sustainable development goal 3: health. WHO, 2017. http://www.who.int/universal_health_coverage/en/. Accessed 20 July 2017.

- 3.Marie-Paule Kieny, WHO Assistant Director-General, Health Systems and Innovation. Universal health coverage: unique challenges, bold solutions. World Health Organization. 2017. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/commentaries/2016/universal-health-coverage-challenges-solutions/en/.

- 4.Tedros A. Speech: WHO: appointment of Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus as new WHO director-general. 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5oUdOYARcRA. Accessed 23 June 2017.

- 5.United Nations High-Level Working Group on the Health and Human Rights of Women, Children and Adolescents . Leading the realization of human rights to health and through health: report of the high-level working group on the health and human rights of women, children and adolescents. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Status of ratification interactive dashboard, ratification of 18 international human rights treaties. United Nations. http://indicators.ohchr.org/. Accessed 2 Feb 2017.

- 7.United Nations Special Rapporteur Dainus Puras. Report by the special Rapporteur on the right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of mental and physical health, Dainius Puras. U.N. Doc. A/71/304. UN; 2016.

- 8.United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR). General comment no 14: the right to the highest attainable standard of health. U.N. Doc. E/C/.12/2000/4. UN. 2000.

- 9.United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR). General comment no. 22 (2016) on the right to sexual and reproductive health (article 12 of the international covenant on economic, social and cultural rights). U.N. Doc. E/C.12/GC/22. UN. 2000.

- 10.United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child. General comment no 15: the right of the child to the highest attainable standard of health. U.N. Doc. CRC/C/GC/15. UN. 2013.

- 11.United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child. General comment no. 4 (2003): adolescent health and development in the context of the convention on the rights of the child. U.N. Doc. CRC/GC/2003/4. UN. 2003.

- 12.World Health Organization . Positioning health in the post-2015 development agenda. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanghera J, et al. Human rights in the new global strategy. BMJ. 2015;351:h4184. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Independent Accountability Panel. 2016: old challenges, new hopes accountability for the global strategy for women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health. Independent accountability panel. 2016. http://www.iapreport.org/downloads/IAP_Report_September2016.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct 2016.

- 15.United Nations Development Group. The human rights based approach to development cooperation: towards a common understanding among UN agencies. UN. 2003.

- 16.Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, World Health Organization. Technical guidance on the application of a human rights-based approach to the implementation of policies and programmes to reduce preventable maternal morbidity and mortality. U.N. Doc. A/HRC/21/22. UN. 2012.

- 17.United Nations Population Fund. Definitions of rights based approach to development: by perspective. UN. 2003.

- 18.Hamm B. A human rights approach to development. Hum Rights Q. 2001;23:1005–1031. doi: 10.1353/hrq.2001.0055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freedman LP. Achieving the MDGs: health systems as core social institutions. Development. 2005;48(1):19–24. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.development.1100107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamin A. Taking the right to health seriously: implications for health systems, courts and achieving universal health coverage. Hum Rights Q. 2017;39:341–368. doi: 10.1353/hrq.2017.0021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.United Nations Special Rapporteur Anand Grover. Interim report by the special Rapporteur on the right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of mental and physical health, Anand Grover. U.N. Doc. A/67/302. UN. 2012.

- 22.Elowson C, Lins de Albuquerque A. Challenges to peace and security in eastern Africa: the role of IGAD, EAC and EASF, FOI. Swedish Defense Research Agency. 2016. https://www.foi.se/download/18.2bc30cfb157f5e989c31188/1477416021009/FOI+Memo+5634.pdf. Accessed 20 Mar 2017.

- 23.United Nations Development Programme . Human development report 2015: work for human development. New York: UNDP; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO . Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, and the United Nations population division. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO, Regional Office for Africa . Atlas of African health statistics: 2014 health situational analysis of the African region. Brazzaville: WHO, Regional Office for Africa; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwartz JI, Guwattude D, Nugent R, Kiiza CM, et al. Glob Health. 2014;10(77) doi:10.1186/s12992-014-0077-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Rubei D, Herrick C, Brown T. The politics of non-communicable diseases in the global south. Health Place. 2016;39:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.WHO . Global strategy on human resources for health: work force 2030. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coovadia H, et al. The health and health system of South Africa: historical roots of current public health challenges. Lancet. 2009;374(9692):817–834. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60951-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biermann W, Wagao J. The quest for adjustment: Tanzania and the IMF, 1980–1986. Afr Stud Rev. 1986;29(4):89–103. doi: 10.2307/524008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nord R, et al. Tanzania: the story of an African transition. Washington: International Monetary Fund; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kagawa RC, Anglenyer A, Montagu D. The scale of faith based organization participation in health service delivery in developing countries: systemic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e48457. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.UNAIDS . Getting to zero: HIV in eastern and southern Africa. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bendavid E, Bhattacharya J. PEPFAR in Africa: an evaluation of outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(10):688–695. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-10-200905190-00117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lange S. The depoliticisation of development and the democratisation of politics in Tanzania: parallel structures as obstacles to delivering services to the poor. J Dev Stud. 2008;44:1123.

- 36.Fukuda-Parr S, Yamin A, Greenstein J. The power of numbers: a critical review of millennium development goal targets for human development and human rights. J Hum Dev Capabilities. 2014;15:105. doi: 10.1080/19452829.2013.864622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.United Nations. 2010 UN summit, 2010. http://www.un.org/en/mdg/summit2010/. Accessed 20 Mar 2017.

- 38.United Nations. Keeping the promise-united to achieve the millennium development goals, 2010. http://www.un.org/en/mdg/summit2010/pdf/ZeroDraftOutcomeDocument_31May2010rev2.pdf. Accessed 30 Mar 2017.

- 39.WHO. Global strategy for women’s, children’s and adolescent’s health 2016–2030. http://www.who.int/life-course/partners/global-strategy/en/. Accessed 20 Mar 2017.

- 40.Ottersen OP, Dasgupta J, Blouin C, Buss P, Chongsuvivatwong V, Frenk J, et al. The political origins of health inequity: prospects for change. Lancet. 2014;383(9917):630–667. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62407-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kruk M, Pate M, Mullan Z. Introducing the lancet Global Health Commission on quality health systems in the SDG era. Lancet Glob Health. 2017; doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30101-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Gostin L. Global health law. 1. United States: Harvard University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 43.WHO, Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030, 2016. http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/global_strategy_workforce2030_14_print.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 26 Mar 2017.

- 44.Kenya Legal and Ethical Network on HIV & AIDS and Others v. Cabinet Secretary Ministry of Health and Others, Petition No. 250 of 2015 [High Court of Kenya], 2016 (Kenya is divided into 47 Counties –similar to states or provinces– where health programs are provided and managed).

- 45.Diwouta C. A comprehensive analysis of the HIV and AIDS legislation, bills, policies and strategies in EAC. Arusha: East African Community Secretariat; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Braveman P. What are health disparities and health equity? We need to be clear. Pub Health Rep. 2014;129(Suppl 2):5–8. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.WHO Consultative Group on Equity and Universal Health Coverage . Making fair choices on the path to universal health coverage. Geneva: WHO; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Constitutional Court of the Republic of Colombia, Judgment T-760/08. http://www.corteconstitucional.gov.co/relatoria/2008/T-760-08.htm. 2015. Accessed 26 Mar 2017.

- 49.Yamin A, Norheim O. Taking equality seriously: applying human rights frameworks to priority setting in health. Hum Rights Q. 2014;36:296–324. doi: 10.1353/hrq.2014.0027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association of South Africa and Another: In re Ex Parte President of the Republic of South Africa and Others (CCT31/99) ZACC 1; 2000 (2) SA 674; 2000 (3) BCLR 241. (25 February 2000).

- 51.Daniels N. Just health: meeting health needs fairly. New York, Cambridge: University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 52.East African Community . Situational analysis and feasibility study of options for harmonization of social health protection systems towards universal health coverage in the east African community partner states. Arusha: East African Community; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kimani JK, Ettarh R, Kyobutungi C, Mberu B, Muindi K. Determinants for participation in a public health insurance program among residents of urban slums in Nairobi, Kenya: results from a cross-sectional. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:66. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.International Labour Organization-Department of Statistics . Statistical update on employment in the informal economy. Geneva: International Labour Organization-Department of Statistics; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kenya National Bureau of Statistics . Economic survey 2016. Nairobi: Kenya National Bureau of Statistics; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 56.National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda . Labour survey 2016: pilot. Kigali: National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frenk J, Gómez-Dantés O. Ethical and human rights foundations of health policy: lessons from comprehensive reform in Mexico. Health Hum Rights J. 2015;17:31–37. doi: 10.2307/healhumarigh.17.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.World Bank. Uganda project appraisal document. Report no: PAD1794; 2016. 2E5. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/854971471534008736/pdf/PAD-07182016.pdf. Accessed 27 Mar 2017.

- 59.World Bank . Kenya project appraisal document. Report no: PAD1694. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 60.World Bank . Tanzania project appraisal document. Report no: 96274-TZ. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maina B. Medics raise alarm over maternity care. Daily Nation. 2013. http://www.nation.co.ke/news/Medics-raise-alarm-over-maternity-care−/−/1056/1872476/-/view/printVersion/-/8gcs0m/-/index.html. Accessed 10 Aug 2016.

- 62.Millicent Awuor Omuya & Another versus The Attorney General & Another, Petition 562 of 2012 [High Court of Kenya], 7 September 2015.

- 63.WHO. Universal coverage – three dimensions. 2017. http://www.who.int/health_financing/strategy/dimensions/en/. Accessed 30 Mar 2017.

- 64.Baltussen R, et al. Value assessment frameworks for HTA agencies: the organization of evidence-informed deliberative processes. Value Health. 2017;20(2):256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Freedman L, et al. UN Millennium Project, Task Force on Child Health and Maternal Health. 2005. Who’s got the power? Transforming health systems for women and children. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Byskov J, et al. Accountable priority setting for trust in health systems—the need for research into a new approach for strengthening sustainable health action in developing countries. BioMed Center. 2009;7:23. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-7-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fried S, et al. Universal health coverage: necessary but not sufficient. Reprod Health Matt. 2013;21:56. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(13)42739-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Global Financing Facility (GFF) The global financing facility: country-powered investments in support of every woman, every child. Washington, DC: The Global Financing Facility; 2016. p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hurd S, Wilson R, Cody A. Global Health Visions and Catalyst for Change. 2016. Civil society engagement in the global financing facility: analysis and recommendations. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mill JS. On liberty. London: Longman, Roberts & Green; 1869. pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Plato SS. Plato’s Parmenides. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bustreo F, et al. Women’s and children’s health: evidence of impact of human rights. Geneva: WHO Press; 2013. pp. 71–73. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Commission for the Implementation of the Constitution of Kenya . Report of the rights-based approach project in Bungoma, Kitui, and Nyeri counties. 2015. Integrating constitutional values and principles in county health facilities. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Langford M. A poverty of rights: six ways to fix the MDGs. IDS Bull. 2010;41(1):83. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-5436.2010.00108.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR). General comment no. 3: the nature of states parties’ obligations (art. 2, para. 1, of the covenant). UN. 1990.

- 76.Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health. 2015 accountability report – strengthening accountability: achievement and perspectives for women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health. Geneva: WHO. p. 2015. http://www.who.int/entity/pmnch/knowledge/publications/pmnch_report15.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 2 Feb 2017

- 77.United Nations. Sustainable development goal 16. 2016. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg16. Accessed 26 Mar 2017.

- 78.Center for Health, Human Rights & Development. Stop stealing babies – court directs Mulago National Referral Hospital. 2017. http://www.cehurd.org/2017/01/stop-stealing-babies-court-directs-mulago-national-referral-hospital/. Accessed 2 Feb 2017.

- 79.Centre for Health Human Rights and Development et al. versus The Attorney General, Petition 16 of 2011 [Constitutional Court of Uganda], Kampala.

- 80.Daniels N. Justice and justification: reflective equilibrium in theory and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kenyatta U. The Global financing facility: country-powered investments in support of every woman, every child. World Bank (stating, “the health of women and children is of intrinsic value and is a human right.”). http://www.globalfinancingfacility.org/img/GFF_REPORT.pdf. Accessed 27 Mar 2017.

- 82.East African Community . Report on the 9th ordinary meeting of the EAC sectoral council of ministers of health. EAC/SCM/HEALTH/001/2014. Arusha: East African Community; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rwirahira R. EAC members to adopt common healthcare system for the region. The east African. 2012. http://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/Rwanda/News/EAC+members+to+adopt+common+healthcare+system+for+the+region/-/1433218/1513918/-/bhdpcyz/-/index.html. Accessed 24 Oct 2015.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.