Abstract

Although evidence shows that attachment insecurity and disorganization increase risk for the development of psychopathology (Fearon, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, Lapsley, & Roisman, 2010; Groh, Roisman, van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Fearon, 2012), implementation challenges have precluded dissemination of attachment interventions on the broad scale at which they are needed. The Circle of Security–Parenting Intervention (COS-P; Cooper, Hoffman, & Powell, 2009), designed with broad implementation in mind, addresses this gap by training community service providers to use a manualized, video-based program to help caregivers provide a secure base and a safe haven for their children. The present study is a randomized controlled trial of COS-P in a low-income sample of Head Start enrolled children and their mothers. Mothers (N = 141; 75 intervention, 66 waitlist control) completed a baseline assessment and returned with their children after the 10-week intervention for the outcome assessment, which included the Strange Situation. Intent to treat analyses revealed a main effect for maternal response to child distress, with mothers assigned to COS-P reporting fewer unsupportive (but not more supportive) responses to distress than control group mothers, and a main effect for one dimension of child executive functioning (inhibitory control but not cognitive flexibility when maternal age and marital status were controlled), with intervention group children showing greater control. There were, however, no main effects of intervention for child attachment or behavior problems. Exploratory follow-up analyses suggested intervention effects were moderated by maternal attachment style or depressive symptoms, with moderated intervention effects emerging for child attachment security and disorganization, but not avoidance; for inhibitory control but not cognitive flexibility; and for child internalizing but not externalizing behavior problems. This initial randomized controlled trial of the efficacy of COS-P sets the stage for further exploration of “what works for whom” in attachment intervention.

Childhood experiences of parental insensitivity, as well as insecure and disorganized attachment, are precursors of a variety of problematic developmental outcomes; for some outcomes (e.g., physiological dysregulation, externalizing problems, and other forms of developmental psychopathology), disorganized attachment brings heightened risk even in comparison to other types of insecure attachment (e.g., Bernard & Dozier, 2010; Oosterman, De Schipper, Fisher, Dozier, & Schuengel, 2010; for reviews, see Fearon, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, Lapsley, & Roisman, 2010; Groh, Roisman, van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Fearon, 2012; Thompson, 2016). Evidence that some children (e.g., those from low-income households, with depressed mothers, or with exposure to violence/trauma) are at increased risk for insecure and disorganized attachment (e.g., Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, & Kroonenberg, 2004; Fearon & Belsky, 2016; Lyons-Ruth & Jacobvitz, 2016) has led to heightened interest in the development and evaluation of interventions targeting infants and young children with these risk factors. The past 20 years have witnessed the development of numerous therapeutic programs to prevent or ameliorate early insecure and disorganized attachments, often targeting maternal sensitivity as a means of influencing child attachment (e.g., Bernard et al., 2012; Cicchetti, Rogosch, & Toth, 2006; Juffer, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2008; Lieberman & Van Horn, 2005, 2008; Sadler et al., 2013; for reviews, see Berlin, Zeanah, & Lieberman, 2016; and Steele & Steele, in press). Some interventions have succeeded in increasing maternal sensitivity (e.g., van Zeijl et al., 2006), some in reducing the rate of insecure and/or disorganized attachment (e.g., Cicchetti et al., 2006; Lyons-Ruth, Connell, Grunebaum, & Botein, 1990), and some both (e.g., Heinicke, Fineman, Ponce, & Guthrie, 2001; for reviews, see Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, & Juffer, 2003, 2005).

With few exceptions (e.g., Juffer et al., 2008), these interventions are expensive and thus not practical for large-scale public health implementation. For example, high levels of intervener skills, accompanied by extensive protocol training and supervision, are often required to create and deliver individual diagnostic and treatment plans (Sadler et al., 2013). Several interventions rely on individualized video-feedback techniques (in which interveners select videotaped parent–child interactions to review with the parent; e.g., Bernard & Dozier, 2010; Egeland & Erickson, 2004). Although meta-analysis has demonstrated video-based feedback is valuable in promoting effective parenting (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., 2003), it involves the added expense and logistics of finding the time, space, equipment, and skills needed for videotaping parents and children (to which parents must consent), as well as payment for intervener time for presession video review and planning. Some interventions involve the delivery of these expensive services for relatively long periods of time (e.g., Heinicke et al., 2001).

The lack of attachment interventions scaled to meet broad public health needs has led to greater consideration of implementation issues among both researchers and clinicians (e.g., Berlin et al., 2016; Caron, Weston-Lee, Haggerty, & Dozier, 2015; Toth & Gravener, 2012), consistent with recent calls for researchers to attend to issues of implementation during the early stages of intervention planning (Glasgow, Lichtenstein, & Marcus, 2003; Ialongo et al., 2006). Addressing these considerations is critical in order for evidence-based parenting interventions to reach many of the families whose children are at risk for poor developmental outcomes. Consistent with this need, the present study is a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of a cost-effective attachment-based intervention.

The Circle of Security–Parenting (COS-P) Intervention

The need for an attachment-based intervention with the potential for broad implementation motivated the creation of the COS-P intervention (Cooper, Hoffman, & Powell, 2009). COS-P takes an innovative approach to help caregivers increase their capacities to serve as a source of security for their children (i.e., to provide a secure base; Bowlby, 1988), with the idea that this increases caregiver sensitivity and reduces the risk of insecure and disorganized attachment. This intervention was designed with implementation efficiencies and value in mind, in collaboration with staff from the real-world contexts in which it is to be implemented and the diverse at-risk families it is intended to serve (e.g., Head Start programs; Cooper et al., 2009; Woodhouse, Powell, Cooper, Hoffman, & Cassidy, in press).

Theoretical foundations of COS-P: Secure base provision, with a focus on caregiver response to child distress

A central theoretical foundation of COS-P is Bowlby’s (1988) assertion, at the heart of the attachment framework, that children are most likely to develop a secure attachment when they have confidence in an attachment figure to whom they can return as a safe haven for comfort when distressed, and then use as a secure base from which to confidently explore. The COS-P focus on caregiver secure base provision leads to an intervention emphasis on sensitive responsiveness to child distress (as opposed to sensitivity in nondistress contexts). Sensitive responding to child distress not only fosters the child’s use of the caregiver as a safe haven (because of expectations of comfort) but also fosters use of the caregiver as a secure base for exploration (because a distressed child cannot explore). In essence, a child’s experiences of coregulating distress with a responsive caregiver shape adaptive psychobiological responses to stress (including hypothalamus–adrenal–pituitary axis functioning; Blair et al., 2008; Bugental, Martorell, & Barraza, 2003; see Polan & Hofer, 2016), as well as mental representations of the care-giver as helpful and of distress as manageable in a relational context (Bowlby, 1982, 1988/1969). These physiological “hidden regulators” and mental representations are thought to contribute to secure attachment (Cassidy, Ehrlich, & Sherman, 2013). Moreover, these representations and regulatory mechanisms are thought to influence one another throughout development and in turn to provide the child with capacities for confident exploration.

This focus on the importance of caregiving response to child distress draws on several theoretical perspectives in addition to attachment theory (Dix, 1991; Feldman, 2012; Grusec & Davidov, 2010; Leerkes, Weaver, & O’Brien, 2012). Substantial data indicate that negative and atypical caregiving responses to distress are linked to insecure and disorganized attachment and psychopathology (e.g., Del Carmen, Pedersen, Huffman, & Bryan, 1993; Goldberg, Benoit, Blokland, & Madigan, 2003; Spinrad et al., 2007; for a review, see Leerkes, Gedaly, & Su, 2016). Given theory and evidence highlighting the important implications of caregiving response to distress, such caregiving response is a primary focus of COS-P.

Development of COS-P

COS-P was based on the original 20-week Circle of Security (COS; Hoffman, Marvin, Cooper, & Powell, 2006) protocol involving a video-feedback procedure conducted by expert clinicians that requires extensive individualized diagnostic and treatment plans; efficacy trials of several versions of the video-feedback protocol have been conducted (see Woodhouse et al., in press). In two studies, the original COS 20-week protocol was associated with significant decreases in attachment insecurity and disorganization, as compared to attachment assessed prior to COS (Hoffman et al., 2006; Huber, McMahon, & Sweller, 2015a). Further, in a RCT, a four-session home-visiting version of the COS video-feedback protocol revealed interaction effects among intervention, infant temperament, and maternal attachment style; a key finding was that the COS intervention was efficacious in reducing insecure attachment for infant–mother dyads at greatest risk (Cassidy, Woodhouse, Sherman, Stupica, & Lejuez, 2011). Finally, a COS modification designed to begin during pregnancy (COS Perinatal Protocol) was examined with substance-abusing mothers (n = 20) in a jail diversion program; following the program, 70% of infants were secure and just 20% were disorganized, rates comparable to infants of mothers in typical low-risk, middle-class samples and better than rates in typical high-risk samples (Cassidy et al., 2010).

To address resource-related barriers to broad implementation of the initial protocol design, three of the original COS developers (Cooper, Hoffman, and Powell) created a protocol that retained the key components of the original COS model while using a format that could be readily implemented, the COS-P intervention, by relying on typically available resources (e.g., clinicians already associated with Head Start programs), service structures, and service use patterns. During protocol development, the developers gathered input from staff of community agencies that might implement such an intervention (e.g., about funding, staff experience, time for training, and supervision options). Based on agency feedback, the COS-P developers worked to create an intervention applicable to a wide age range of children that could be taught relatively quickly (i.e., during a 4-day training session) to interveners with the skills typically available in community agencies, without need for extensive posttraining supervision. In addition, COS-P was designed so that it could be used with a group of parents (a particularly cost-effective option), as well as with individual parents. The manualized COS-P structure consists of eight modules, a brief structure contributing to greater implementability (see Bakermans-Kranenberg et al., 2003, for meta-analytic findings that relatively shorter attachment interventions are more efficacious). Finally, the intervention framework is user-friendly and face valid, making core components easy for both interveners and parents to understand.

Individualization of treatment despite use of stock video

The most important and challenging aspect in the adaptation of the original COS protocol involved a shift from the use of video of the specific caregiver–child dyad and accompanying individualized diagnostic and treatment plans to the use of stock video footage only, a shift necessary to allow broad implementation. Use of the same stock video footage with all parents may seem to suggest the lack of an individualized approach, yet this is not the case: individualized treatment is possible because parents are given tools (a vocabulary and a framework for observing and reflecting) that help them come to understand themselves and their individual children. First, parents are given tools to recognize and understand the different forms that children’s attachment-related needs can take (including how to consider the contribution of each child’s unique temperamental characteristics). Second, parents are helped to recognize and understand the ways children’s behaviors evoke specific thoughts and feelings in them (the caregivers), how these thoughts and feelings can guide their caregiving behavior, and how these caregiving behaviors can influence their children. Such insight is particularly important for parents who have experienced trauma or atypical caregiving in their own childhoods, as is the case for many parents in high-risk samples; theory and data suggest that the capacity to reflect on one’s own attachment experiences is key in breaking intergenerational cycles of insecure attachment (e.g., Cicchetti & Toth, 1997; Slade, 2016; Slade, Grienenberger, Bernbach, Levy, & Locker, 2005). These activities lay the foundation for skills of reflective dialogue, emotion regulation, parental empathy toward the child (referred to as the empathic shift), and caregiving sensitivity to child distress needed for secure base provision.

Additional Attachment-Related Child Outcomes: Executive Functioning (EF) and Behavior Problems

Although COS-P was designed to increase caregiver sensitivity to child distress and reduce the risk of insecure and disorganized attachment, it is useful to assess the intervention’s success in improving additional attachment-related child outcomes. For example, secure attachment has been shown to predict aspects of EF, including working memory, cognitive flexibility, and inhibitory control, in preschool children (Bernier, Carlson, Deschênes, & Matte-Gagné, 2012). EF skills are critical for success in school and life, and predict school readiness among children from low-income families above and beyond general intelligence (Blair & Razza, 2007). Not incidentally, the three key caregiving dimensions linked to children’s EF (sensitivity, mind–mindedness, and autonomy–support; Carlson, 2003) have also been linked to secure attachment (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978; Bernier & Dozier, 2003; Whipple, Bernier, & Mageau, 2011). Further, a recent study found that children of parents who participated in the Attachment and Biobehavioral Catchup for Toddlers program showed improved EF skills following the intervention, including reduced attention problems and enhanced cognitive flexibility (Lind, Raby, Caron, Roben, & Dozier, 2017 [this issue]).

Beyond EF, substantial research has linked secure child attachment to reduced risk for internalizing and externalizing problems, as noted above (for reviews, see Cicchetti, Toth, & Lynch, 1995; DeKlyen & Greenberg, 2016; Fearon et al., 2010; Groh et al., 2012). Further, an efficacy study of the original Circle of Security 20-week intervention found significant reductions in internalizing and externalizing behavior postintervention (Huber, McMahon, & Sweller, 2015b). Because EF and child behavior problems span two aspects of child functioning that have been linked to child attachment, and because they have such important implications for children’s social, academic, and mental health functioning (e.g., Bull, Espy, & Wiebe, 2008; see Williford, Carter, & Pianta, 2016), examining these outcomes is an important next step in assessing attachment intervention effects.

Moderators of Intervention Efficacy

Examination of potential moderators of intervention efficacy allows insight into the important issue of “what works for whom.” As noted by Rothwell (2005), it is important to consider interaction effects because of the potential for any intervention to affect subgroups of individuals differently. Potential disordinal treatment-subgroup interactions would be of particular importance to consider because of their clinical implications for individual outcomes (Byar, 1985). Rothwell commented that RCTs were originally designed for agricultural research, in which researchers were interested in overall crop outcomes rather than the well-being of any specific individual plant. In contrast, in the context of intervention with families of young children, the well-being of individual parents and children assumes great significance. Unfortunately, nearly all trials that are sufficiently powered to detect main intervention effects are underpowered to detect treatment-subgroup interactions (Rothwell, 2005). Rothwell argued that, although potential moderators identified via post hoc analyses should be considered suspect, moderators identified in an a priori fashion should be explored and interpreted in a tentative fashion, with the understanding that the best test of the validity of any given interaction effect emerges from results of future studies.

Given the limitations of sample size dictated by the funding available for the present study, examination of interaction effects could be done on an exploratory basis only. Nevertheless, we specified on an a priori basis two potential moderators of interest for which planned, exploratory analyses of interaction effects were conducted, namely, maternal depressive symptoms and maternal attachment style. As described below, previous research identified these variables as key potential moderators.

Maternal depressive symptomatology is a commonly examined moderator of attachment-based intervention. In a study of an attachment intervention for Early Head Start families, mothers higher on depressive symptoms showed the largest gains in maternal sensitivity following the intervention; moreover, whereas children in the control group were at increased risk for disorganization as maternal depressive symptoms increased, there was no such increase in risk for children in the intervention group, suggesting a buffering effect (Spieker, Nelson, DeKlyen, & Staerkel, 2005; see Robinson & Emde, 2004). In contrast, it is possible that reduced psychological resources such as depressive symptoms may preclude some parents from being able to benefit from the intervention for a number of reasons (e.g., attention difficulties or lowered capacity to change behavior).

In addition to depressive symptoms, maternal (self-reported) attachment style has also been explored as a potential moderator of treatment effects. Adult attachment style is conceptualized in terms of two dimensions: attachment anxiety (a preoccupation with relationships and fear of abandonment) and avoidance (a tendency to avoid interpersonal closeness; Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998). There is insufficient research to predict the nature of a potential moderation effect: some evidence suggests that adults who report more secure attachment styles may derive greater benefit from therapeutic interventions because they are better able to form a working alliance with the therapist/intervener (e.g., Eames & Roth, 2000; see Slade, 2016), yet some evidence indicates that interventions are more effective for insecure mothers, who have the greatest room for improvement in terms of their parenting (Robinson & Emde, 2004; see Jones, Cassidy, & Shaver, 2015, for a review of studies indicating that parents with self-reported insecure attachment style show more problematic parenting-related emotions, cognitions, and behaviors; see Cassidy et al., 2011, for a study in which maternal attachment style interacted with infant temperament to predict intervention outcome). Exploration of these potential moderating factors could be important for a more nuanced understanding of intervention efficacy.

The Present Study

The present study is the initial examination of the extent to which COS-P achieves its core aims of increasing caregiver sensitivity (in particular, maternal response to child distress) and of reducing the risk of insecure and disorganized attachment upon the conclusion of the intervention. This RCT also allowed us to examine whether the intervention reduces other risks associated with insecure and disorganized attachment in terms of improved EF and reduced behavior problems. Finally, we conducted exploratory analyses of potential moderators of intervention effects in an effort to begin to ask the questions about what works for whom: maternal depressive symptoms, maternal attachment (anxiety and avoidance), as well as child sex. With this study, we extend previous research on the impacts of attachment-based interventions by examining a relatively low-cost intervention with the potential for broad implementation.

The COS-P intervention was provided to mothers whose children were enrolled in four Head Start centers in Baltimore, Maryland. The Head Start program was chosen for two principal reasons. First, attending children and their families are characterized by multiple factors that place the children at risk for insecure attachment. Head Start/Early Head Start (HS/EHS) focuses principally on families whose incomes fall at or below the federal poverty line (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2008). In addition to being poor, HS/EHS participants are considered to be at risk in a variety of ways. The majority of families are single-parent households (58%), approximately one-third of parents have less than a high school education, and exposure to violent crime and arrests for crime are elevated in children enrolled in HS/EHS and their families (Office of Head Start National Center on Program Management and Fiscal Operations, 2008); further, data reveal that at the time of enrollment, most mothers “report enough depressive symptoms to be considered depressed” (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2006). Second, cost-efficiencies are important considerations for services provided within the HS/EHS context (Office of Head Start National Center on Program Management and Fiscal Operations, 2013), making COS-P a viable option for service providers working with HS families.

Participating mothers completed a set of baseline questionnaires and were then randomized into either a 10-week COS-P intervention group or a waitlist control group. Outcome assessments were obtained in a single laboratory visit. Child attachment and EF were assessed with widely used standardized laboratory observational measures, and mothers reported on their typical responses to their child’s distress and on child behavior problems; mothers also reported on their own attachment style and depressive symptoms, which were examined as potential moderators of intervention efficacy.

We hypothesized that intervention group mothers, compared to control group mothers, would be less likely to show unsupportive responses to their children’s distress and more likely to show supportive responses. We also hypothesized that intervention group children, compared to control group children, would show greater attachment security and less avoidance, and would be less likely to show disorganized attachment. A set of secondary analyses focused on research questions about whether the children of intervention group mothers differed from those of control group mothers on EF or behavior problems. We advanced no specific hypotheses for these secondary analyses because COS-P was not specifically designed to influence these aspects of child functioning. More important, EF and behavior problems were conceptualized as more distal outcomes, whereas changes in parenting responses toward the child and in the child’s attachment to the parent were viewed as more proximal outcomes. Thus, given that the sole outcome assessment occurred immediately following intervention, it was not clear whether there would be sufficient time for treatment group differences in EF and child behavior to emerge. Finally, because of mixed previous findings in the literature, we made no predictions about the moderating role of maternal attachment style or depressive symptoms in our exploratory examination of interaction effects.

Method

Participants

Mothers and their 3- to 5-year-old children were recruited from four local Head Start centers in low socioeconomic status (SES) communities across 15 months. Eligibility criteria were (a) custodial mother was over the age of 18, proficient in English, lacking untreated thought disorders (e.g., schizophrenia), available for weekly group intervention meetings, and not a previous Circle of Security participant; and (b) child had no severe illness or major developmental disorder (e.g., autism). If a mother had more than one HS-enrolled child, the youngest child was selected.

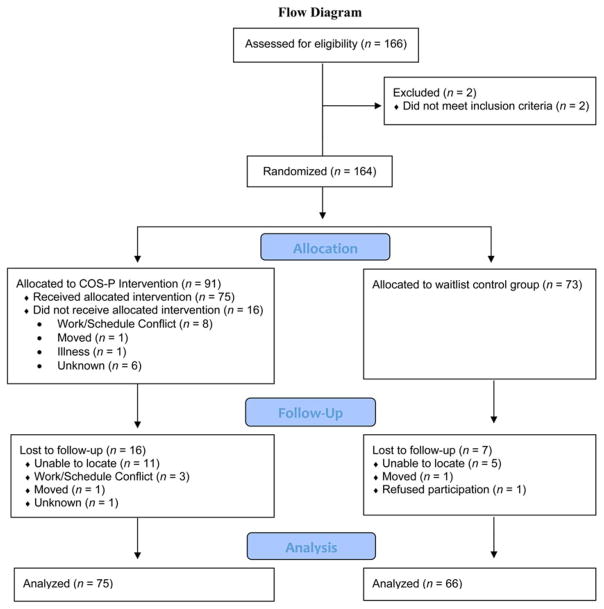

One hundred sixty-four dyads met eligibility criteria and participated in the baseline assessment; 91 mothers were randomly assigned to the intervention group and 73 to the wait-list control group. Of these 164 dyads, 23 did not participate in the outcome assessment, leaving 141 dyads with both baseline and outcome measures (75 intervention, 66 control). See Figure 1 for a flowchart detailing participant retention and withdrawal, and Table 1 for demographic information for participants included in analyses.

Figure 1.

(Color online) Flowchart detailing enrollment, participant retention, and experimentation processes.

Table 1.

Demographic information of participants with outcome data by treatment group

| Intervention (n = 75)

|

Control (n = 66)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | M (SD) | Range | n (%) | M (SD) | Range | |

| Mothers | ||||||

| Age (years)a | 28.21 (5.39) | 18.00–44.00 | 31.07 (7.14) | 20.33–48.00 | ||

| Education | ||||||

| Some HS | 8 (11%) | 16 (24%) | ||||

| HS graduate | 39 (52%) | 26 (39%) | ||||

| Some college | 22 (29%) | 22 (33%) | ||||

| College graduate | 3 (4%) | 2 (3%) | ||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| African American | 61 (81%) | 45 (68%) | ||||

| White | 8 (11%) | 9 (14%) | ||||

| Other | 4 (5%) | 7 (11%) | ||||

| Marital statusb | ||||||

| Single | 68 (91%) | 49 (74%) | ||||

| Married | 6 (8%) | 17 (26%) | ||||

| Children | ||||||

| Age (months) | 50.68 (5.94) | 40.45–63.58 | 51.15 (6.01) | 39.87–61.71 | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Girl | 43 (57%) | 39 (59%) | ||||

| Boy | 32 (43%) | 27 (41%) | ||||

Note: HS, High school. For some variables, the percentages do not total 100% because of missing data: for maternal education, n = 3; for ethnicity, n = 7; for marital status, n = 1.

Intervention group mothers were significantly younger than control group mothers, t (139) = −2.75, p = .007.

More intervention group mothers were single than control group mothers, χ2 (1, N = 140) = 7.92, p = .005.

Study design and procedure

Data were collected across three waves. For each wave, baseline data were collected in a 1-hr group session at the HS center from which each dyad was recruited. After providing informed consent, mothers completed a series of questionnaires assessing (a) personal characteristics, including attachment style, depressive symptoms, response to child distress, and other constructs not related to the current study; (b) family characteristics, including demographics; and (c) child behavior problems. Mothers received $25 for their participation.

Next, mothers were randomly assigned either to the COS-P intervention group or to a waitlist control group. Within each HS center, random assignment was stratified by race. More mothers were randomly assigned to the intervention group than the control group to increase statistical power (Baldwin, Bauer, Stice, & Rohde, 2011). Intervention group mothers attended weekly COS-P group meetings for 10 weeks at their usual HS center. Three intervention groups were conducted in each of the three waves, for a total of nine groups. Mothers received $15 per session attended. Interveners telephoned intervention group mothers weekly to encourage attendance, and called control group mothers three times at regular intervals to maintain contact and interest in the study. After the 10-week intervention period, all mothers from that wave (i.e., both intervention and control group mothers) were invited to the laboratory outcome assessment, detailed below. Once mothers in a given wave had completed the outcome assessment (typically within 2 months following the intervention period), waitlist control group mothers from that wave were invited to attend COS-P sessions and received the same compensation as intervention group mothers.

Outcome assessments occurred in individual 2-hr sessions at a laboratory playroom in a local clinic. Childcare for siblings and transportation were provided as needed. Mother–child dyads first completed an observational assessment of child attachment. Mothers then completed additional assessments in a private room, including the questionnaires completed at baseline. Children remained in the playroom and completed a series of tasks with an adult experimenter, including tasks measuring EF. The session was video-recorded for later coding. Upon completion of the outcome assessment, mothers received $50.

COS-P intervention

The COS-P protocol (Cooper et al., 2009) is divided into eight treatment modules that were delivered in weekly 90-min sessions for 10 weeks; each chapter contains approximately 15 min of archival video clips that are viewed and discussed during the session. The clips are of child–parent interactions, as well as of previous COS-P participants reflecting on what they learned about their own parenting from COS-P. The video indicates where to pause, what to discuss, and how to help parents consider their own parenting, as does the intervention manual.

Chapters 1 and 2 introduce parents to basic concepts of attachment, the use of the COS graphic as a map for parent–child interaction, and children’s secure base and safe haven needs. Chapters 3 and 4 address the concept of being with children emotionally; the core of being with is providing an emotional safe haven by responding to children’s affective states. In Chapter 5, parents consider the importance of reflecting on their own caregiving struggles. COS employs the user-friendly metaphor of shark music (i.e., the scary soundtrack that colors otherwise safe situations) to give parents a vocabulary for talking about defensive processes outside their conscious awareness that influence parenting. Parents learn that these defensive processes, often developed within their own attachment relationships, can make them experience some of their children’s needs as threatening. By labeling these threats “shark music,” parents can pause their habitual response, calm themselves (by “putting feelings into words”; Lieberman et al., 2007), and respond to their child’s needs, rather than to their own fears. Avoidant and ambivalent attachment patterns are introduced and contextualized as child adaptations to insensitive parenting. In Chapters 6 and 7, parents learn about disorganized attachment through discussion of mean (hostile), weak (helpless), and gone (neglecting) parenting (Lyons-Ruth, Yellin, Melnick, & Atwood, 2005). Parents discuss the importance of rupture and repair in relationships, and how rupture–repair processes support emotion regulation and successful relationships. Chapter 8 consists of a summary, discussion of the group’s experience, and celebration of parents’ completion of the program.

COS-P requires parents to take generalized information about children’s needs from stock video and apply it to their own strengths and struggles. At the same time, interveners individualize the program by inviting parents to describe attachment-related interactions with their child during the previous week. These are framed as circle stories and are used to help parents understand and enhance their secure base and safe haven provision. The supportive presence of the intervener creates a secure base from which parents can explore difficult parenting experiences and feelings (Bowlby, 1988). Four clinicians (three master’s level and one doctoral level) who worked with participating HS agencies or nearby social service agencies serving similar populations led the intervention groups; each group was led by a single intervener.

Intervention fidelity

A number of steps were taken to ensure fidelity in intervention delivery. First, a detailed manual specified the goals for each session and the procedures for attaining those goals. The manual described specific activities, as well as prescribed and proscribed intervener behaviors during intervention activities. Second, interveners were trained using a standardized protocol delivered by one of the COS-P developers. Third, all sessions were videotaped, allowing interveners to receive weekly supervision from a COS-P developer that included review of session videotapes and competent adherence to the manual. Fourth, interveners completed three self-report measures after each session to document their adherence to the manual. Interveners used the COS-P Facilitator Checklist to indicate whether they had completed each of the required activities for that session. One intervener failed to complete the checklist for all 10 weeks of one group, 9 weeks of a second group, and 1 week of a third group. Across all sessions for which the checklists were completed, interveners as a group indicated that they had completed 69% of the required activities, with a range across interveners from 63% to 74%. Interveners also used the Session Goals Rating Form to rate the degree to which they believed each goal specified for that session had been met using a scale of 1 (did not address this goal) to 4 (fully addressed this goal). Across all sessions, intervener ratings of the degree to which each goal was met was M = 3.41 (SD = 0.26), with a range across interveners from 2.90 to 3.57. In addition, interveners used the 13-item Facilitative Behaviors Rating Form to rate the degree to which they perceived themselves to have engaged in appropriate, facilitative behaviors (i.e., competently using prescribed behaviors and avoiding proscribed behaviors) on a scale from 1 (never) to 4 (most of the time), with proscribed behaviors reverse scored. Across all sessions, intervener ratings of competent use of appropriate, facilitative behaviors was M = 3.34 (SD = 0.14), with a range across interveners from 3.05 to 3.42. Fifth, because providing consistency in treatment dosage is a key aspect of ensuring fidelity (Bellg et al., 2004), participant attendance was monitored and steps were taken to encourage attendance and exposure to all material (e.g., regular calls or texts to encourage attendance, requests to come early to a session to make up material from a missed session, review of the previous session at the start of each session). Participants were informed that mothers who missed four sessions would be discontinued from the group. Sixty-four percent of mothers assigned to the intervention group completed at least six sessions.

Measures

Preschool Attachment Classification System

Following guidelines from Cassidy, Marvin, and The MacArthur Attachment Working Group (1992), children and mothers participated in a modified Strange Situation Procedure (Ainsworth et al., 1978), consisting of an initial 3-min period in which both mother and child were in the toy-filled playroom, followed by two separations (3 and 5 min) and two 3-min reunions. Based largely on children’s behavior upon reunion, children are given continuous scores reflecting attachment security and avoidance, each ranging from 1 to 7. High scores on the security scale are given to children who engage in warm, intimate reunions with the parent, as manifested either by affectionate physical proximity and/or contact, or through eager, responsive, continuing conversation, whereas low scores on the security scale are given for a variety of behaviors, as described below. High scores on the avoidance scale are given to children who limit physical or psychological closeness with the mother, although in a neutral and nonconfrontational manner.

Children also receive one of five attachment classifications: children classified as secure engage in warm, intimate interactions as described above; children classified as insecure–avoidant limit proximity and show neutral, nonconfrontational behavior; children classified as insecure–ambivalent show immature behavior and ambivalence about proximity seeking; and insecure–controlling/disorganized children control the interaction or show behaviors common to disorganized infants (e.g., freezing, fear expressions). Insecure–other children show a mixture of insecure behaviors; following typical practices, these children were combined with the insecure–controlling/disorganized group to form a single insecure–disorganized group lacking an organized attachment strategy (Main, 1990).

Children received three final scores reflecting attachment quality. In addition to the two continuous scores of security and avoidance, children were given a dichotomous score indicating whether they were classified as disorganized (insecure–disorganized group) versus organized (i.e., all other groups).

This widely used measure has strong psychometric properties (for a review, see Solomon & George, 2016). One coder coded all cases, and a second coded a randomly selected 26% of cases (intraclass correlation security = 0.89, p < .001; intraclass correlation avoidance = 0.96, p < .001; for classification groups, 86% agreement, Cohen κ = 0.79, p < .001). Coders were blind to information about the child or the mother, including intervention status. Disagreements were resolved through conferencing.

Coping With Toddlers’ Negative Emotions Scale (CTNES)

This scale (Spinrad et al., 2007) was used to measure mothers’ responses to child distress. Following item examination and the advice of on-site experienced Head Start staff, the CTNES was deemed most appropriate for the present sample (compared to a version of this measure designed for older children). Studies support the validity of the CTNES in pre-school children, showing the expected correlations between scores on the CTNES at toddler and preschool ages (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2010).

Caregivers rate their likelihood of engaging in each of seven possible responses to their child’s negative emotions in 12 hypothetical scenarios in which the child becomes upset, angry, or distressed (e.g., “If my child becomes upset and cries because he is left alone in his bedroom to go to sleep, I would:”). For each scenario, responses include the following: (a) distress reactions (e.g., “Become upset myself”), (b) punitive reactions (e.g., “Tell my child that if he doesn’t stop crying, we won’t get to do something fun when he wakes up”), (c) minimizing reactions (e.g., “Tell him that there is nothing to be afraid of”), (d) expressive encouragement (e.g., “Tell my child it’s okay to cry when he is sad”), (e) emotion-focused reactions (e.g., “Soothe my child with a hug or kiss”), (f) problem-focused reactions (e.g., “Help my child find ways to deal with my absence”), and (g) granting the child’s wish (e.g., “Stay with my child or take him out of the bedroom to be with me until he falls asleep”). For each scenario, caregivers rated each possible response from 1 (very likely) to 7 (very unlikely). The CTNES has demonstrated good reliability and validity (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2010; Gudmundson & Leerkes, 2012; Spinrad et al., 2007).

Following Gudmundson and Leerkes’s (2012) adaptation of the method from Spinrad et al. (2007), we averaged items from the expressive encouragement (αbaseline = 0.90, αoutcome = 0.91), emotion-focused (αbaseline = 0.76, αoutcome = 0.74), and problem-focused (αbaseline = 0.84, αoutcome = 0.86) subscales to create a composite measure of supportive responses to child distress (36 items; αbaseline = 0.89, αoutcome = 0.89, possible range = 1–7), and averaged items from the punitive (αbaseline = 0.79, αoutcome = 0.82), minimizing (αbaseline = 0.76, αoutcome = 0.80), and distress (αbaseline = 0.77, αoutcome = 0.74) subscales to create a composite measure of unsupportive responses to child distress (36 items; αbaseline = 0.85, αoutcome = 0.86, possible range = 1–7). We decided a priori to exclude the granting the child’s wish subscale because previous research indicated low internal consistency and a lack of fit with either composite (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2010; Spinrad et al., 2007). The two composites were reverse scored so that higher scores indicate more likely responding.

Child EF

Puppet-Says Task

The Puppet-Says Task (Kochanska, Murray, Jacques, Koenig, & Vandegeest, 1996; adapted from Reed, Pien, & Rothbart, 1984) is a simplified version of “Simon Says” designed to measure children’s inhibitory control. First, an experimenter asks children to perform 10 simple actions (e.g., “Touch your nose”) to demonstrate their understanding of each action. She then introduces two hand puppets (a puppy and an elephant), one of which is labeled “nice” and the other “mean,” with the identities of the puppets counterbalanced. Children are told to “do what the nice puppet says,” but “don’t do what the mean puppet says.” Children completed two practice trials to assess task comprehension, one for each puppet.

Children’s performance on the practice trials was coded on a 3-point comprehension scale (1 = passed trials immediately, 2 = passed trials eventually after at least one verbal correction, 3 = had to be physically guided to pass trials). Following the practice trials, children completed 12 test trials, alternating between the nice and mean puppet, with each giving six commands. Task instructions were repeated once after the first 6 trials. All test trials were coded for the child’s degree of movement in response to the given command (0 = no movement/did not comply with request, 1 = partial movement/began to comply with request, then stopped, 2 =complete movement/complied with request). Children’s summed score across trials with the mean puppet was subtracted from their summed score with the nice puppet, yielding a final score for inhibitory control, with higher values indicating better ability to comply with the nice puppet and to inhibit compliance with the mean puppet.

All cases were coded by two independent blind coders from video recordings; disagreements were resolved through consensus. The Krippendorff α values (Hayes & Krippendorff, 2007) for the three task variables ranged from 0.94 to 1.00. The Puppet Says Task has demonstrated good consistency with other measures of inhibitory control (Kochanska et al., 1996).

Dimensional Change Card Sort

In this measure of cognitive flexibility (Zelazo, Frye, & Rapus, 1996), children are shown a series of cards, one at a time, with one of two shapes (boat or rabbit) in one of two colors (red or blue); the children are instructed to place each card into one of two containers (one marked with a blue rabbit and one with a red boat) using a sorting rule of either shape or color. Children are asked first to sort six cards by one dimension (e.g., color), and then they are asked to switch and sort six cards by the other dimension (e.g., shape), for a total of 12 test trials (for details, see Zelazo, 2006). Prior to the test trials, an experimenter introduces the first sorting rule and demonstrates placing a card in the appropriate container, and children complete a practice trial to ensure comprehension. The experimenter repeats the sorting rule before each trial. Both the order of the sorting rules and the placement of the containers are counterbalanced across participants. Each child’s score is the number of correct sorts on the 6 test trials using the second sorting rule (i.e., the number correct after the child was asked to switch rules; possible range = 0–6), with higher scores indicating better cognitive flexibility.

All cases were coded by two independent coders from video-recordings; disagreements were resolved through consensus. Krippendorff α (Hayes & Krippendorff, 2007) was 0.97. This widely used task shows good test–retest reliability (Beck, Schaefer, Pang, & Carlson, 2011) and convergent validity with measures such as the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (Zelazo et al., 2013).

Child Behavior Checklist 1.5–5

Mothers completed this widely used 100-item questionnaire (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) to report their children’s internalizing (36 items, e.g., “is nervous, withdrawn”) and externalizing (24 items, e.g., “is restless, disobedient”) behavior problems. Reponses were given on a 3-point scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat/sometimes true, 2 = very/often true). Items were summed to create subscales for internalizing (αbaseline = 0.88, αoutcome = 0.87, possible range = 0–72) and externalizing (αbaseline = 0.92, αoutcome = 0.92, possible range = 0–48) problems. The Child Behavior Checklist shows strong psychometric properties (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000).

Potential moderators of intervention efficacy

Experiences in Close Relationships Scale (ECR)

The ECR (Brennan et al., 1998; Wei, Russell, Mallinckrodt, & Vogel, 2007) is a self-report measure of adult attachment anxiety and avoidance. The anxiety dimension reflects individuals’ fear of interpersonal rejection and abandonment (e.g., “I worry about being abandoned”), whereas the avoidance dimension reflects individuals’ feelings of discomfort with close relationships and avoidance of intimacy or reliance on others (e.g., “I get uncomfortable when people want to be very close to me”). Each item is rated on a 7-point scale from 1 (disagree strongly) to 7 (agree strongly). Mothers’ attachment anxiety and avoidance were calculated by averaging responses across subscale items, resulting in an anxiety and avoidance score for each participant. For logistical reasons, the first 53 participating mothers (at the baseline assessment only) completed the 12-item ECR—Short Version (ECR-S; 6 anxiety items, 6 avoidance items; Wei et al., 2007). In all other instances, mothers completed the original 36-item scale (18 anxiety items, 18 avoidance items; Brennan et al., 1998). Research indicates that for both avoidance and anxiety subscales, correlations across the two ECR versions are above .94 (Wei et al., 2007). Good internal consistency was evident in the present study (for attachment anxiety, αmeanbaseline = 0.75 and αoutcome = 0.93; for avoidance, αmeanbaseline = 0.78 and αoutcome = 0.86). Both the ECR and the ECR-S have been found to yield reliable and valid scores (Brennan et al., 1998; Crowell, Fraley, & Roisman, 2016; Wei et al., 2007).

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale

This 20-item self-report measure (Radloff, 1977) taps the frequency with which respondents experienced depressive symptoms over the past week. Responses are given on a 4-point scale, with 0 indicating that the symptom was rarely or never felt, and 3 indicating that it was experienced most or all of the time. Items were summed to derive a total score for depressive symptoms (αbaseline = 0.91, αoutcome = 0.91). The measure is widely used with both clinical and nonclinical populations (Beekman et al., 1997; Radloff, 1991); it shows good internal reliability across diverse samples (Radloff, 1977) and good validity (Clark, Mahoney, Clark, & Eriksen, 2002).

Demographic information

Mothers provided demographic information, including their age, education, race/ethnicity, and marital status, as well as their child’s age and sex (Table 1).

Results

Data analytic plan

We analyzed effects of the intervention on the two outcomes that COS-P directly targets: child attachment (security, avoidance, and organized vs. disorganized classification) and mothers’ responses to child distress (supportive and unsupportive responses). Next, we analyzed effects of the intervention on two secondary outcomes (as described above): child EF (inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility) and child behavior problems (internalizing and externalizing). Child sex was tested as a moderator of treatment effects; because none of the interactions was significant, however, child sex was dropped from analyses and is not reported here. Finally, we conducted additional exploratory analyses testing interactions between intervention group assignment and two moderators: baseline maternal attachment style (avoidant and anxious dimensions) and baseline maternal depressive symptoms.

To select covariates, we first examined all baseline and demographic variables on which the intervention and control groups significantly differed. Only two such variables emerged: intervention group mothers were younger and more likely to be single than control group mothers (see Table 1). Thus, all analyses included mothers’ age and marital status as covariates; we also examined results when these covariates were not included in analyses, and we report any differences found. In models testing an outcome that was also measured at baseline (maternal supportive and unsupportive responses to child distress, and child internalizing and externalizing behavior problems), we also controlled for baseline levels of that variable. In models testing child EF, we included child’s age and task comprehension, in line with previous studies of this outcome (e.g., Kochanska, Murray, & Coy, 1997).

Multilevel models were used in all analyses to accommodate the partially nested structure of the data. Partial nesting refers to data where observations are clustered into higher level units for some conditions but are unclustered in other conditions. In the present study, data from intervention group families were clustered because these participants attended one of nine COS-P groups; in contrast, data from control group families were unclustered because these participants had no contact with one another. We used the approach proposed by Bauer, Sterba, and Hallfors (2008) for modeling partially nested data, which treats each participant in ungrouped conditions as a group of one and which specifies experimental condition as a random effect. Analyses were performed using the MIXED (continuous outcomes) and GENLINMIXED (dichotomous outcomes) procedures in SPSS.

In line with current standards of intervention research, we used intent to treat (ITT; Gupta, 2011) analyses, in which participants are analyzed as randomly assigned, regardless of the amount of treatment received. We also conducted two sets of as-treated analyses, which take into account participants’ level of exposure to the intervention, defining level of exposure in two ways: (a) total number of sessions attended (a continuous variable), and (b) attended at least six sessions or not (a dichotomous variable). Using as-treated analyses did not change the pattern of findings, and so we report only results from the ITT analyses here.

Missing data

Only dyads that attended the outcome assessment are included in the reported analyses (141 out of 164 eligible dyads; see Figure 1). Mothers who attended the outcome assessment did not significantly differ on any baseline or demographic variables from mothers who did not attend. We analyzed data in each model using complete case analysis. Outcome data from several children were not available due to technical problems or child refusal, leading to reduced effective sample sizes for models predicting child attachment (N = 137), cognitive flexibility scores (N = 136), and inhibitory control scores (N = 135).

Analyses for the present study relied on modeling methods that could reflect the partially nested data (Bauer et al., 2008); these methods could not be practicably implemented in an analytic program that allowed for full information maximum likelihood to handle missing data. Thus, for participants missing responses to fewer than 20% of items on a given questionnaire subscale, we substituted each participant’s mean for the missing items (this was rare: an average of 0.3% of items were mean substituted across all subscales used in analyses). This method, which is equivalent to averaging available data, has been found to be reasonably statistically sound (Schafer & Graham, 2002). For participants missing responses to more than 20% of items on a questionnaire subscale, the participant’s data were not included in analyses using that subscale (this was also rare: less than 1% of all possible subscale scores were missing for this reason).

Preliminary analyses

Distributions for all variables were examined for skewness and kurtosis, as were residual distributions when regressing outcomes on covariates. Only one measure had a nonnormal distribution: child internalizing behavior problems at baseline (skew = 1.53, kurtosis = 3.28) and at outcome (skew = 1.48, kurtosis = 2.66). These scores were inverse-transformed, and the resulting distributions showed acceptable levels of skew (0.49 at baseline, 0.63 at outcome), as well as acceptable levels of kurtosis (−0.05 at baseline and −0.04 at outcome). These scores were then multiplied by −1 so that interpretation of variable levels would be in the same direction as the original variable (e.g., higher scores reflect higher levels of internalizing behavior), and were rescaled so that the minimum and maximum scores match the original scores for ease of interpretation.

Descriptive statistics

At baseline, maternal depressive symptoms ranged from 0 to 48.00 on the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (M = 17.73, SD = 12.25). Maternal attachment avoidance on the ECR ranged from 1.00 to 7.00 (M = 3.25, SD = 1.22), and attachment anxiety ranged from 1.00 to 6.50 (M = 3.15, SD = 1.27).

At outcome, the attachment classification distribution was as follows for children in the control group: 35 (55%) secure, 9 (14%) avoidant, 7 (11%) ambivalent, and 13 (20%) disorganized. In the intervention group, 38 (52%) were secure, 16 (22%) avoidant, 5 (7%) ambivalent, and 14 (19%) disorganized.

Intervention effects

Table 2 shows estimated marginal means for the intervention and control groups on all outcomes (except for the dichotomous disorganized attachment classification), as well as statistical tests of treatment main effects, including effect sizes, on continuous outcomes from the multilevel models. The pattern of results for the principal study outcomes of attachment and maternal response to distress remained the same when mothers’ age and marital status were not included as covariates (as did patterns for other study outcomes, except as noted below).

Table 2.

Adjusted means and treatment effects from mixed models predicting child and mother outcomes

| Intervention Group

|

Control Group

|

Treatment Effect

|

Moderators of Treatment Effect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | 95% CI | M | 95% CI | t | p | d | ||

| Child attachment | ||||||||

| Security | 4.98 | [4.45, 5.51] | 5.00 | [4.56, 5.43] | −0.04 | .97 | −0.01 | MAAv (p = .001) |

| Avoidance | 2.59 | [2.23, 2.96] | 2.54 | [2.16, 2.93] | 0.18 | .86 | −0.03 | |

| Responses to child distress | ||||||||

| Supportive responses | 5.72 | [5.51, 5.92] | 5.74 | [5.58, 5.91] | −0.22 | .83 | −0.03 | |

| Unsupportive responses | 3.32 | [3.16, 3.47] | 3.57 | [3.40, 3.74] | −2.18 | .03 | 0.37 | |

| Child functioning | ||||||||

| Internalizing behavior | 14.34 | [12.76, 15.91] | 15.08 | [13.38, 16.78] | −0.62 | .54 | 0.11 | MAAx (p = .03) |

| Externalizing behavior | 13.02 | [11.47, 14.57] | 12.53 | [11.12, 13.93] | 0.48 | .63 | −0.08 | MD (p = .03) |

| EF cognitive flexibility | 2.34 | [1.72, 2.96] | 2.91 | [2.25, 3.57] | −1.22 | .23 | −0.21 | |

| EF inhibitory control | 6.74 | [5.82, 7.67] | 5.14 | [4.16, 6.11] | 2.31 | .02 | 0.40 | MAAx (p = .03) |

Note: MAAv, maternal attachment avoidance; MAAx, maternal attachment anxiety; MD, maternal depressive symptoms; EF, executive functioning.

Child attachment

As shown in Table 2, there were no main effects of intervention on continuous attachment outcomes (i.e., security or avoidance). Moreover, rates of disorganized attachment were not found to differ between the treatment (19%) and control (20%) groups, t (132) = 0.26, p = .79 (odds ratio [OR] = 1.15).

Maternal response to child distress

As shown in Table 2, the intervention reduced mothers’ unsupportive responses to child distress. The intervention did not alter mothers’ supportive responses to child distress.

Child functioning

EF

Children of intervention group mothers showed better inhibitory control than children of control group mothers (see Table 2), although this effect was not present when maternal age and marital status were not controlled, t (128) =1.74, p = .20, d = 0.30. No differences between the intervention and control groups emerged for child cognitive flexibility.

Child behavior problems

The COS-P intervention had no main effect on child internalizing or externalizing behavior problems (see Table 2).

Moderation of intervention effects by maternal attachment style and depression: Exploratory analyses

We conducted planned, exploratory analyses to examine whether dimensions of adult attachment style (i.e., anxiety and avoidance) or maternal depressive symptoms moderated treatment effects. For interactions involving maternal attachment style, we first examined three-way interactions of intervention group assignment with both the avoidant and anxious dimensions before testing each dimension as a separate moderator; because no significant three-way interactions emerged, we do not report them here. Maternal attachment avoidance and anxiety were always included in a model together, as is standard practice in studies of adult attachment style using the ECR (e.g., Mikulincer, Shaver, Gillath, & Nitzberg, 2005). When statistically significant interactions emerged, they were probed by testing simple main effects at the mean and at ±1 SD from the mean of the moderator. We did not adjust individual test α levels to control the family-wise Type I error because we were concerned that this strategy would be counter to the discovery-oriented, exploratory nature of these analyses. This concern was heightened by the sample size, which was relatively small for detecting a moderator effect (see Aiken & West, 1991). We believe our approach balanced attention to Type I error and Type II error, and facilitated our goal of guiding future research by identifying potential Subgroup × Treatment interactions for future examination.

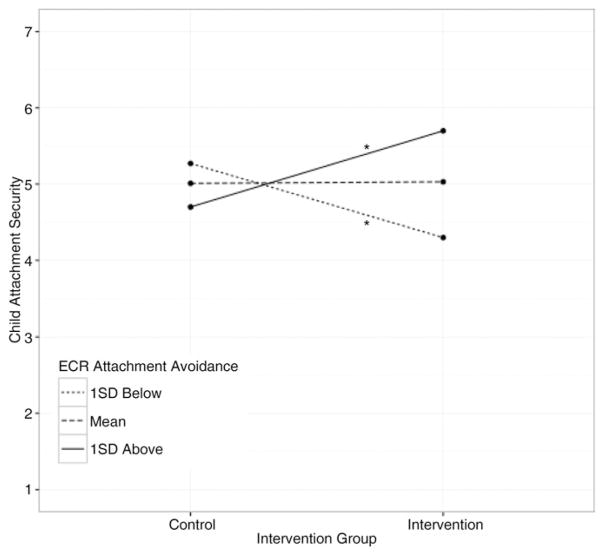

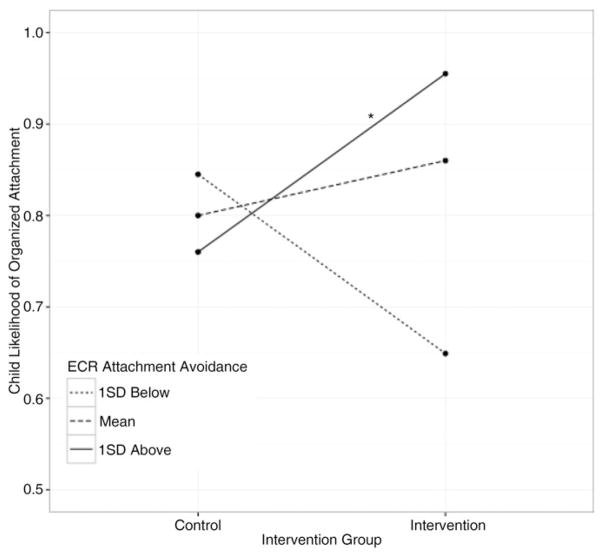

Moderated effects on child attachment

The nonsignificant main effect of the intervention on child attachment was qualified by two significant interactions: maternal attachment avoidance moderated intervention effects both on child security, t (128) =3.37, p =.001, and on rates of disorganization, t (128) = 2.38, p = .02. Probing these interactions revealed that, when their mothers were 1 SD above the mean on attachment avoidance, intervention group children tended to be both more secure, t (128) = 2.38, p = .02, d = 0.41, and less disorganized, z =2.31, p =.02 (OR =6.77), than control group children. When their mothers were at the mean on attachment avoidance, there was no evidence of a main effect of treatment on security, t (128) = 0.06, p = .95, d = 0.01, or disorganization, z =0.79, p =.43 (OR =1.52). When their mothers were 1 SD below the mean on attachment avoidance, intervention group children tended to be less secure than control group children, t (128) = −2.31, p = .02, d = −0.40, but there was no evidence of a main effect of treatment on disorganization z = −1.68, p = .09 (OR = 0.34). See Figures 2 and 3. Maternal attachment avoidance did not moderate effects on child avoidance, t (128) = −1.46, p = .15.

Figure 2.

Moderated effect of intervention on child attachment security at low, mean, and high levels of maternal attachment avoidance. *p <.05.

Figure 3.

Moderated effect of intervention on children’s likelihood of organized attachment at low, mean, and high levels of maternal attachment avoidance. *p < .05.

No other variables moderated intervention effects on child attachment, including (a) maternal attachment anxiety on child security, t (128) = 0.11, p = .92, child avoidance, t (128) = 0.24, p = .81, or disorganization, t (128) = 0.64, p = .52; and (b) maternal depressive symptoms on child security, t (128) = −1.02, p = .31, child avoidance, t (130) = 1.44, p = .15, or disorganization, t (130) = −0.39, p = .70.

Moderated effects on maternal response to distress

The significant main effect of intervention on maternal unsupportive response to distress was not moderated by maternal attachment anxiety, t (128) = 0.06, p = .95, maternal attachment avoidance, t (128) = 1.61, p = .11, or maternal depressive symptoms, t (130) = 0.03, p = .97. The nonsignificant main effect of intervention on maternal supportive response to distress was not moderated by maternal attachment anxiety, t (128) = −1.34, p = .18, maternal attachment avoidance, t (128) = 0.23, p = .82, or maternal depressive symptoms, t (130) = −1.21, p = .23.

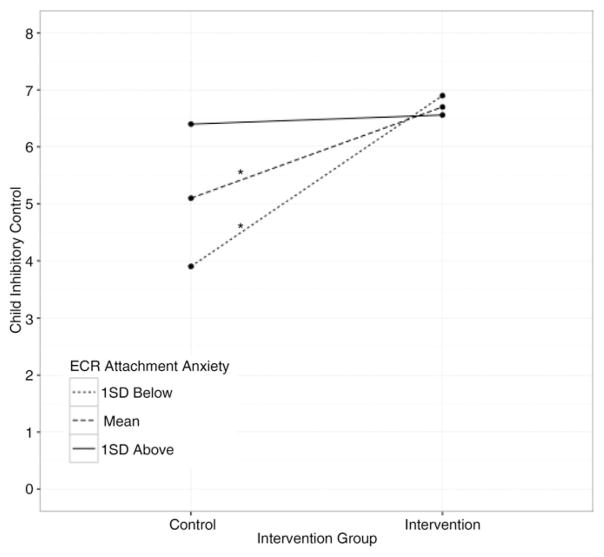

Moderated effects on child EF

The significant main effect of intervention status on inhibitory control (controlling for maternal age and marital status) was qualified by an interaction with maternal attachment anxiety, t (122) = −2.16, p = .03, such that the positive treatment effect held only when mothers were 1 SD below, t (122) = 3.08, p = .003, d = 0.54, or at the mean, t (122) = 2.27, p = .03, d = 0.40, on attachment anxiety; no effect was found when mothers were 1 SD above the mean on attachment anxiety, t (122) = 0.12, p = .91, d = 0.02; see Figure 4. (For this interaction, when covariates were not included, t (124) = −1.83, p = .07, yet the simple main effects remained significant at low, t (125) = 2.77, p = .01, d = 0.48, and average, t (125) = 2.10, p = .04, d = 0.37, but not high, t (125) = 0.21, p = .84, d = 0.04, levels of attachment anxiety.) Neither maternal attachment avoidance, t (122) = 0.02, p = .99, nor maternal depressive symptoms, t (124) = −0.74, p = .46, moderated treatment effects on child inhibitory control. The nonsignificant difference between the intervention and control groups for child cognitive flexibility was not moderated by maternal attachment anxiety, t (122) = −1.76, p = .08, attachment avoidance, t (122) = −0.32, p = .75, or depressive symptoms, t (124) = −0.65, p = .52.

Figure 4.

Moderated effect of intervention on child inhibitory control at low, mean, and high levels of maternal attachment anxiety. *p < .05.

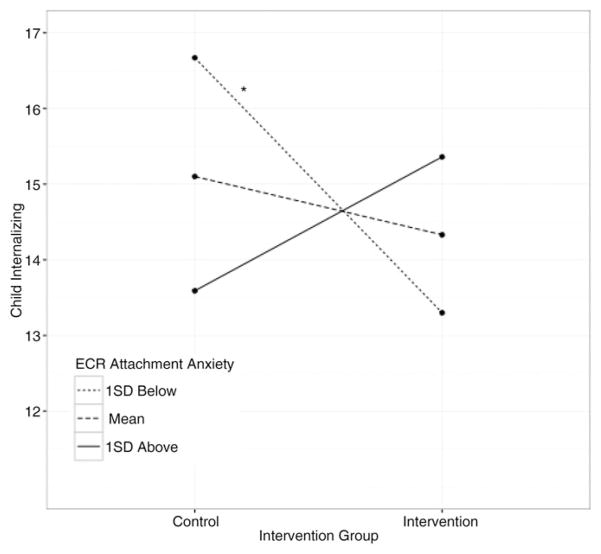

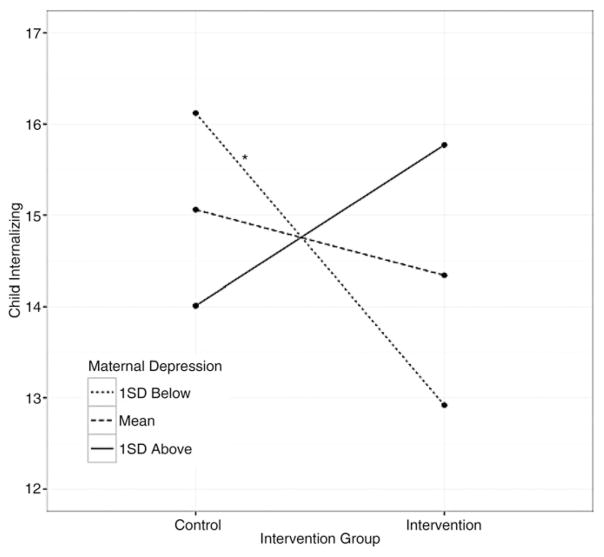

Moderated effects on child behavior problems

The nonsignificant main effect of intervention status on child internalizing problems was qualified by two significant interactions: Treatment × Maternal Attachment Anxiety, t (128) = 2.22, p = .03, and Treatment × Maternal Depressive Symptoms, t (129) = 2.17, p = .03; see Figures 5 and 6. Specifically, intervention group children had fewer mother-reported internalizing problems than control group children when mothers were 1 SD below the mean on attachment anxiety, t (128) = −1.99, p < .05, d = 0.34, or 1 SD below the mean on depressive symptoms, t (129) = −1.95, p = .05, d = 0.34. No simple effects emerged predicting child internalizing problems when mothers were at the mean on attachment anxiety, t (128) = −0.67, p = .51, d = 0.12, or depressive symptoms, t (129) = −0.61, p = .54, d = 0.10. Similarly, no simple effects were found when mothers were 1 SD above the mean on attachment anxiety, t (128) = 1.08, p = .28, d = −0.19, or depressive symptoms, t (129) = 1.06, p = .29, d = −0.18. When demographic covariates were not included, predictions of child internalizing problems were as follows: Treatment × Maternal Attachment Anxiety, t (131) = 1.81, p = .07, and Treatment × Maternal Depressive Symptoms, t (132) =1.76, p =.08. Intervention effects on internalizing problems were not moderated by maternal attachment avoidance, t (128) = 1.25, p = .22.

Figure 5.

Moderated effect of intervention on child internalizing behavior (transformed scores) at low, mean, and high levels of maternal attachment anxiety. *p < .05.

Figure 6.

Moderated effect of intervention on child internalizing behavior (transformed scores) at low, mean, and high levels of maternal depressive symptoms. *p = .05.

For externalizing problems, the nonsignificant intervention effect was not moderated by maternal attachment anxiety, t (130) = 1.93, p = .06, attachment avoidance, t (130) = 1.08, p = .28, or depressive symptoms, t (131) = 0.25, p = .80.

Discussion

The goal of the study was to conduct an RCT of the COS-P intervention within HS programs. In so doing, we address a critical barrier to progress in the attempt to reduce the risk of insecure and disorganized attachment among at-risk children living in poverty. Moreover, the present study tested the outcomes of an intervention that was designed for broad implementation, from the start, in collaboration with staff from the real-world contexts in which it would be implemented and with the diverse families it is intended to serve. Main effects for intervention were found only for maternal unsupportive (not supportive) responses to infant distress and, when controlling for maternal age and marital status, for child inhibitory control, but not for child attachment, child behavior problems, or child cognitive flexibility.

Consistent with past research, our exploratory analyses indicated that treatment was moderated by maternal self-reported attachment style (attachment anxiety and avoidance) and maternal depressive symptoms. It is important to note that the present RCT, like most RCTs (Rothwell, 2005), was not sufficiently powered to examine moderation and that the causal implications of the RCT design do not extend to potential moderators that cannot be randomly assigned (e.g., maternal characteristics). Moreover, although consistent with our discovery-oriented strategy, our uncontrolled family-wise Type I error rate increased our risk of incorrectly identifying potential moderation effects. Thus, results from the exploratory moderation analyses are interpreted with due caution, and are framed as setting the stage for future research. Below, we outline implications of the findings of the present study.

Child attachment

No main effects of intervention were found for child attachment in the present study, and it is difficult to know how to interpret a lack of significant main effects of treatment. It may be the case that COS-P, like many interventions, is not efficacious for all individuals, and the task becomes one of identifying those for whom it works in its current form and attempting to find ways of helping others. Yet future research involving a more fine-grained analysis of intervener fidelity and group process could potentially reveal delivery factors that could be changed. It may be that inclusion of an individualized pretreatment assessment would contribute to the ways in which COS-P can be tailored to better meet the needs of individual parents within sessions. Moreover, inclusion of additional follow-up assessments of outcome would be useful in capturing the degree to which delayed changes in attachment may emerge over time as learning consolidates. In sum, it will be important to conduct additional research on COS-P in order to explore factors that may be linked to child outcomes. From a public health perspective, it would be particularly beneficial to identify factors linked to improved outcomes that add as little as possible to the cost of implementation, so costs associated with potential changes to COS-P or its delivery could be used to guide decisions about future research.

Findings from the exploratory moderational analyses in the present study may also be important in guiding the direction of future research. These results indicated that self-reported maternal attachment style moderated the effect of treatment on child attachment. Although treatment effects for such predefined subgroups must be interpreted with caution, such interaction effects can have important clinical implications and can help to guide future research (Rothwell, 2005). If future research supports our findings that children of highly avoidant mothers assigned to COS-P were more secure and less likely to be disorganized, compared to children in the control group, then the implications for these children will be important in terms of public health benefits because insecurity and disorganization in early childhood put children at risk for a wide range of negative outcomes (e.g., Bernard & Dozier, 2010; Colonnesi et al., 2011; Fearon et al., 2010; Groh et al., 2012). Future research (e.g., an RCT testing the efficacy of COS-P in a sample selected for high levels of avoidance) could be conducted to provide more compelling evidence regarding whether COS-P increases attachment security and decreases the likelihood of attachment disorganization for children of highly avoidant mothers. If so, COS-P may thus reduce risk for later psychopathology and other negative outcomes for children of mothers with highly avoidant attachment styles and do so in a highly cost-efficient manner.

Such future research with mothers who are high in attachment avoidance could also examine mechanisms through which intervention may influence parenting processes and child outcomes, if present findings hold. Because self-reported adult attachment avoidance is consistently linked to negative parental attributions and insensitive behavior (Jones et al., 2015), as well as low empathy (Stern, Borelli, & Smiley, 2015), highly avoidant mothers may benefit from COS-P because of its emphasis on reducing insensitive caregiving by shifting toward an empathic view of their children’s needs. In addition, theory and research suggest that therapeutic settings that gently challenge clients’ insecure attachment styles tend to be most effective in fostering change (Daly & Mallinckrodt, 2009; see Daniel, 2006; Slade, 2016); it may be that the focus of COS-P provides such a challenge to avoidant mothers, thus fostering change more effectively among these mothers.

The unexpected finding that children of intervention group mothers with low attachment avoidance showed lower attachment security immediately after the intervention than did children in the control group is difficult to interpret. Further research is needed to examine whether this apparent iatrogenic effect is replicated or occurred merely by chance. It is likely that, by their very nature, many parenting interventions create disruptions in parenting and in child expectations, especially as parents begin to change habitual behavior. For children of highly avoidant mothers, this change would likely be positive, to the extent that insensitive responding is reduced and parents are becoming better able to serve as a safe haven. For children whose mothers were already engaging in supportive, attuned caregiving, however (which may be the case for children of low-avoidant mothers; e.g., Edelstein et al., 2004), a disruption could lead to short-term negative influences on children’s attachment-related expectations. As Lilienfeld (2007) noted, some treatments have been shown to result in short-term worsening of functioning for at least some recipients, despite evidence that the intervention is effective in terms of longer term outcomes. Future research with longer term follow-up assessments will be important in order to examine this possibility. Moreover, researchers should attend to the possibility that any intervention might be detrimental to a particular subset of individuals, so that modifications to individualized treatment can be made. Lilienfeld (2007) pointed out that too few researchers attend to deterioration effects in RCTs. If future research using a larger sample size and designed to detect moderated effects (e.g., using stratification of randomization by high and low levels of avoidance) replicates the observed moderation effect of maternal avoidance, it will be important to identify the mechanisms that explain differential outcomes for children of mothers high versus low in avoidance. Such information could be used to modify COS-P in ways that would reduce differential outcomes, and improve COS-P as a tool in broader implementation efforts.

It is unclear why we did not find a moderating effect whereby the intervention had a positive impact on the children of mothers high on attachment anxiety. Evidence suggests that attachment anxiety is associated with heightened self-disclosure and overfocus on attachment issues (Slade, 2016); thus, group sessions might not offer needed challenges to these mothers’ hyperactivating style. Moreover, some research has shown that attachment anxiety is associated with less psychological flexibility, the ability to change thoughts or behavior to serve valued ends (Salande & Hawkins, 2016); thus, anxious caregivers may need more time and practice to bring cognitions and behavior into alignment with intervention goals. It may also be that the intervention effected preliminary change in anxious mothers, but that the follow-up assessment occurred too soon after the intervention to capture the full effects.

In contrast to findings related to moderating effects of maternal attachment style on treatment effects for child attachment security and disorganization, no intervention effects emerged for child avoidance. It may be that child avoidance is a particularly engrained child attachment strategy that takes longer to shift in preschoolers. Researchers know strikingly little about the extent to which interventions are successful specifically in reducing avoidance, as nearly all previous studies report results in terms of secure versus insecure or organized versus disorganized attachment. Future research examining intervention effects on specific attachment dimensions will be important for shedding light on this issue.

Maternal response to child distress

As expected, mothers in the intervention group reported engaging in fewer unsupportive responses to their children’s distress than mothers in the control group following COS-P, regardless of maternal attachment style or depressive symptoms. A central goal of COS-P is to help parents serve as a secure base and safe haven for their children, via the empathic shift, whereby parents improve their ability to view their children’s behavior through the lens of empathy and understanding (Woodhouse et al., in press). When children experience that their distress can be expressed without eliciting negative responses, they may feel better understood by their caregiver and thus be more likely to use that caregiver as a secure base and safe haven. As noted earlier, substantial data indicate that it is caregivers’ responses to distress in particular that contribute to child attachment (e.g., Del Carmen et al., 1993), and to developmental outcomes such as internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Leerkes, Blankson, & O’Brien, 2009; see Spinrad et al., 2007). Thus, reducing mothers’ unsupportive responses through COS-P represents an important step in reducing children’s risk for insecure and disorganized attachment and psychopathology. Although other interventions have provided evidence of increasing maternal sensitivity broadly defined (i.e., including response to distress within a broader construct), to our knowledge, no previous intervention has provided specific evidence of reducing maternal unsupportive responses to child distress.

The use of maternal self-report to measure responses to child distress brings with it both strengths and limitations. Like all self-report measures, problems of social desirability and reporter bias are present. However, given that distress can occur infrequently in preschoolers, it can be difficult to observe, and parents may modify responses in observational contexts. For these reasons, we used a well-validated self-report measure that taps maternal responses to child distress across a range of contexts. Moreover, our findings (i.e., that mothers reported fewer unsupportive but not more supportive responses to distress postintervention) suggest that mothers were not simply responding in ways aligned with the parenting discussed in COS-P. Given its established links with observed parenting and child outcomes (Eisenberg et al., 2010), along with its ease of administration and scoring, the CTNES may be useful for tracking intervention outcomes in larger dissemination trials.

We had expected that intervention group mothers would report more supportive responses to child distress than control group mothers because the items in the supportive composite all reflect values imparted in the COS-P program. For instance, the expressive encouragement subscale (e.g., “tell my child that it’s ok to be upset”) is akin to the COS-P notion of being with, in which the parent accepts the child’s negative emotions in the moment rather than actively attempting to alter them. That supportive responses did not appear to change in response to intervention is puzzling. Future studies should determine if supportive responses increase with time or, alternately, if COS-P does not effect change in maternal supportive behavior. It is interesting to note, however, that Eisenberg et al. (2010) found that, across the toddler and preschool ages, only maternal unsupportive responses (and not supportive responses) were significantly correlated with observations of maternal sensitivity, maternal warmth, and child separation distress, and with childcare provider ratings of child externalizing symptoms. Such findings suggest that maternal self-reports of unsupportive responses are valid indices of mothers’ behavioral responding, whereas self-reports of supportive responses are not linked to these behaviors. Such findings raise questions about whether supportive maternal responses to child distress, at least as reported by parents, are ultimately important targets of intervention.

Child functioning