Abstract

Impairment of ubiquitin-proteasome system activity involving ubiquitin ligase genes UBE3A, UBE3B, and HUWE1 and deubiquitinating enzyme genes USP7 and USP9X has been reported in patients with neurodevelopmental delays. To date, only handful of single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and copy-number variants (CNVs) involving TRIP12, encoding a member of the HECT domain E3 ubiquitin ligases family on chromosome 2q36.3 have been reported. Using chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) and whole exome sequencing (WES), we have identified, respectively, five deletion CNVs and four inactivating SNVs (two frameshifts, one missense, and one splicing) in TRIP12. Seven of these variants were found to be de novo; parental studies could not be completed in two families. Quantitative PCR analyses of the splicing mutation showed a dramatically decreased level of TRIP12 mRNA in the proband compared to the family controls, indicating a loss-of-function (LoF) mechanism. The shared clinical features include intellectual disability with or without autistic spectrum disorders, speech delay, and facial dysmorphism. Our findings demonstrate that E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIP12 plays an important role in nervous system development and function. The nine presented pathogenic variants further document that TRIP12 haploinsufficiency causes childhood-onset neurodevelopmental disorder. Finally, our data enable expansion of the phenotypic spectrum of ubiquitin-proteasome dependent disorders.

Keywords: whole exome sequencing, chromosomal microarray, copy-number variants

INTRODUCTION

Copy-number variants involving chromosome 2q36.3 are rare. To date, only two interstitial deletion CNVs involving TRIP12 [MIM 604506], encoding a member of the HECT domain E3 ubiquitin ligases family, have been reported in the literature: a de novo ~ 5.4 Mb CNV deletion on 2q36.2q36.3 has been identified in an individual with severe intellectual disability (ID), multiple renal cysts, and dysmorphic features (Doco-Fenzy et al. 2008) and a de novo ~ 60 kb deletion involving FBXO36 and the first non-coding exon of TRIP12 has been described in a subject with an autistic spectrum disorder (Pinto et al. 2014). An ~ 180 kb CNV duplication encompassing FBXO36 and the 5′ portion of TRIP12 has been reported in an individual with macrocephaly (Figure 1a) (Oikonomakis et al. 2016). Recently, four TRIP12 de novo single nucleotide variants have been identified amongst 64 autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) candidate genes re-sequenced in 5,979 individuals; two missense and two truncating variants were detected in individuals with ASDs and ID, ranging from mild to moderate severity (O’Roak et al. 2014). Most recently, Lelieveld et al. (2016) have reported two additional truncating mutations in TRIP12 among 2,637 de novo mutations across 1,990 genes identified in a meta-analysis of 2,104 trios involving individuals with sporadic ID (Figure 1b and 1c). While this study was under review, Bramswig et al. (2016) reported a cohort of eleven individuals with variants in TRIP12, including the three patients reported by O’Roak et al. (2014). In addition, Subject 8 in our study was also enrolled in Bramswig et al.’s cohort (individual 8). We compare the clinical features in our patient cohort with all reported patients and discuss the TRIP12 associated phenotypic spectrum.

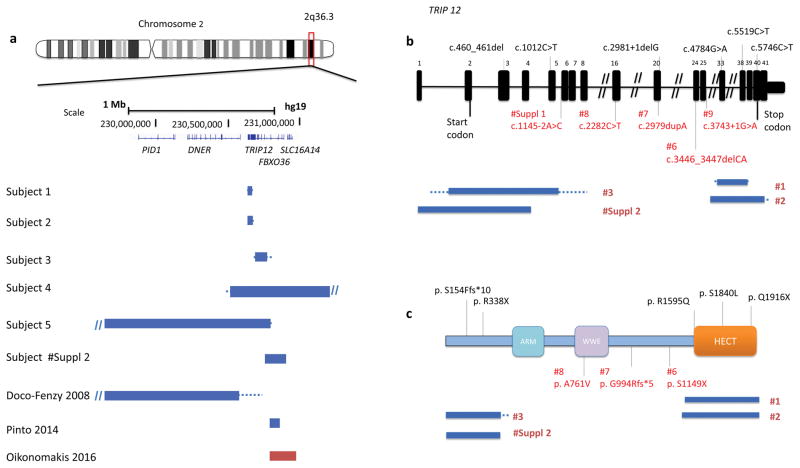

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic representation of 2q36.3 CNV deletions involving TRIP12 identified by exon-targeted CMA in six subjects from this study and three CNV subjects reported previously. Deletions are indicated in blue and duplications in red. The dotted lines depict the maximum deletion regions. (b) TRIP12 gene exonic structure. Three TRIP12 exonic deletion CNVs identified in subjects 1–3 are indicated under the diagram (blue bars indicate the minimum deletion region and the dotted lines depict the maximum deletion regions). The variants from this study are indicated in red and the previously reported variants are indicated in black. Reported variants include two missense c.5519C>T (p.S1840L) and c.4784G>A (p.R1595Q) and two truncating c.2981+1delG and c.1012C>T (p.R338X) changes from ASDs cohort studies (O’Roak et al. 2014) and c.5746C>T (p.Q1916X) and c.460_461del (p.S154Ffs*10) from 2,104 trio studies (Lelieveld et al. 2016). (c) Functional domains of TRIP12 include ARM domain (turquoise), WWE domain (purple) and HECT (E6AP-type E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase) (orange).

METHODS

Study Cohort

The study cohort consists of nine unrelated patients. Five patients carrying deletion CNVs in chromosome 2q36.3 were identified in our clinical database of 75,795 subjects referred for clinical chromosomal microarray analysis. Three patients carrying SNVs were found through our database of 9,056 individuals referred for clinical whole exome sequencing. These three patients were chosen through filtering for potentially LoF variants in previously unsolved cases with overlapping neurological phenotypes. The ninth subject was identified from a cohort of 207 individuals through CHU Angers, France, who had global developmental delay and was referred for WES trio analysis. To further investigate these novel variants, we have enrolled all nine individuals (age range from 1.8 years to 15 years) in research studies approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Baylor College of Medicine and CHU Angers in France. Written informed consents were obtained from the families. Consents for publication of the photographs were attained from the parents/legal guardians of subjects 5, 7, 8, 9, and subject Suppl 1.

Microarray and Molecular Analyses

The five CNV deletions were detected using customized exon-targeted oligo arrays (OLIGO V8, V9, and V10) designed at Baylor Genetics (Boone et al. 2010; Wiszniewska et al. 2014), which cover more than 4800 known or candidate disease genes with exon level resolution. The WES-targeted regions cover >23,000 genes for capture design (VCRome by NimbleGen®). The mean coverage of target bases was >140X, and >96% target bases were covered at >20X (Yang et al. 2014). WES trio analysis was performed using SureSelectXT Target Enrichment Kit capture by Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA with the mean coverage of 52X at the genomics platform of Nantes (Biogenouest Genomics). PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing to verify all candidate variants were done in the proband and the parents when available, according to standard procedures and candidate variants were annotated using the TRIP12 RefSeq transcript NM_004238. Quantitative PCR was performed to determine TRIP12 mRNA expression in the blood samples of the proband and controls by Applied Biosystems TaqMan Assays system based on the manufacturer’s instruction. The primers TRIP12_Forward (5′-GGATGCTGTGAGCAGAGAGA-3′) and TRIP12_Reverse (5′-CATCTGATCCATCGTCATCG-3′) were used in the qPCR experiments.

RESULTS

Study Cohort

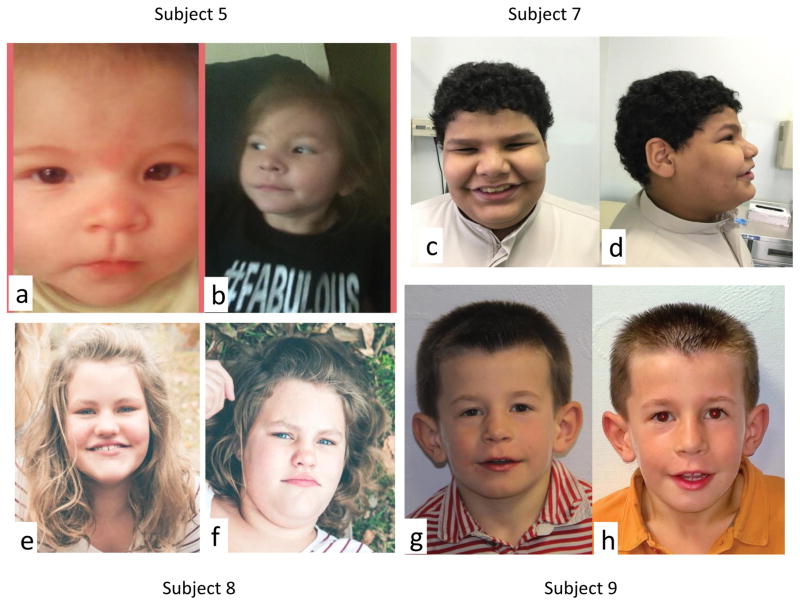

In our cohort all nine individuals presented with moderate to severe DD/ID and six of them manifested autistic behaviors (see Table 1 for detailed information). Similarly, Bramswig et al. also reported that all their eleven patients had DD/ID and eight out of eleven manifested some autistic behaviors. However, our patients showed more severe verbal defects. Out of eight patients with detailed clinical information, only one patient achieved fluent speech (12.5%), six patients had phrase or single words (75%), and one patient had no speech at 4 year of age (12.5%). In the Bramswig et al.’s cohort, six out of eleven patients could speak fluently (54.5%); the other patients spoke either phrases or single words (45.5%). Behavioral abnormalities in our cohort vary substantially, ranging from poor social interaction to extremely impulsive and aggressive behaviors, which were also reported in Bramswig et al.’s patients. Dysmorphic facial features are also variable; however, narrow up-slanting palpebral fissures (seen in four out of our seven subjects, 57.1%) and a distinct mouth with downturned corners (four out of our eight subjects in main cohort plus one supplementary patient, 55.6%) appear to be the most commonly shared facial feature in our cohort (Figure 2); these two features were not discussed in Bramswig et al.’s cohort. Of note, obesity was documented in four of our seven children (57.1%), with one progressing to morbid obesity. Interestingly, although the weight of subject 2 was 23.3 kg at 7 years of age (~ 52 centile), his calculated BMI was ~ 91 centile. Two subjects were also reported as obese in Bramswig’s cohort. Combined together, six out of eighteen individuals were documented as obese (33.3%). Microcephaly was observed in two our subjects and was not seen in Bramswig et al.’s cohort, and epilepsy was seen in one our individual but in three individuals in Bramswig et al.’s cohort. These data suggest that microcephaly (12.5%) and seizure (21%) are only minor features of TRIP12 associated syndrome. Among the other facial features, the most commonly shared features between two cohorts include wide months (37.5%) and large ear lobe (37.5%).

Table 1.

Summary of clinical presentations, and CMA and molecular findings in nine individuals with TRIP12 mutations

| Subject 1 | Subject 2 | Subject 3 | Subject 4 | Subject 5 | Subject 6 | Subject 7 | Subject 8 | Subject 9 | Summary from this study | Summary from Bramswig et al.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | Male | Male | Female | Female | Male | Male | Female | Male | 6 males, 3 females | 7 males, 4 females |

| Age at examination (years) | 15 | 7 | 15 | 4 | 1.8 | 4 | 10 | 12.5 | 7 | 1.8 to 15 | 5.7 to 26.3 |

|

TRIP12 Variant

(NM_004238) Genomic coordinates (min/max, hg19) |

Deletion of 9 exons

(30–38) chr2:230,634,390/230,636,077–230,654,539/230,655,748 |

Deletion of 17 exons

(25–41) chr2: 230,631,958/230,632,049–230,660,565/230,661,210 |

Deletion of 4 exons

(2–5) chr2:230, 230,679,862/698,794–230,781,114/230,801,002 |

Deletion of TRIP12 and

adjacent 7

genes chr2:230,489,478/230,513,445–231,457,431/231,508,839 |

Deletion of TRIP12 and 3

adjacent

genes chr2:229,076,749/229,152,599–230,801,061/230,811,273 |

Frameshift c.3446_3447delCA

(p.S1149*X) Chr2: 230,661,450 |

Frameshift c.2979dupA (p.G994Rfs*5) Chr2: 230,666,969 |

Missense c.2282C>T (p.A761V) Chr2: 230,672,494 |

Splicing c.3743+1G>A Chr2: 230,659,894 |

5 CNVs (microdeletions) 3 SNVs/indels (2 truncating, 1 missense) |

1 translocation 10 SNVs/indels (5 truncating, 5 missense) |

| Ethnicity | Mexican | NA | NA | Caucasian | NA | Saudi Arabia | United Arab Emirates (second cousins parents) | North European/Caucasian | Caucasian | ||

| Inheritance | de novo | Unknown | Unknown | de novo | de novo | de novo | de novo | de novo | de novo | 7 de novo, 2 parents NA | 9 de novo 2 parents NA |

| Maternal age at birth (years) | 45 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 25 | 25 | 26 | 29 | 25–45 | 22–34 |

| Paternal age at birth (years) | 47 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 35 | 27 | 34 | 48 | 27–48 | 25–41 |

| DD/ID | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 9/9 | 11/11 |

| Speech delay | + | + | ND | + | + | +. | + | + | + | 8/8 | 10/11 1 ND |

| Autistic behaviors | + Poor social interaction | − | ND | +. Stereotypic behaviors |

+ | +. | +. | +. | − | 6/8 | 8/11 |

| Other behavioral anomalies | Hyper anxiety. Untypical behaviors | ND | Repetitive, aggressive behaviors/sensory issues | Hyperactive and destructive behavior | ND | Extremely impulsive and aggressive behaviors. | − | 6/7 | 8/11 | ||

| First words (months) | 36 | 60 | ND | 24 | ND | ND | ND | 24 | 42 | ||

| Verbal ability | Fluent speech | <100 words at 7 years | ND | 30 words | 5–6 words | No words | single words | Phrase speech | Few phrase speech | 1/8 fluent speech 6/8 phrase or single words 1/8 no words |

6/11 fluent speech 5/11 phrase or single words |

| Motor delay | + | − | ND | + | + | + | + | + | + | 7/8 | 7/11 |

| Walking independently (months) | 15 | ND | ND | 20 | ND | ND | 22 | 23 | 29 | 15–29 | 13–23 |

| Seizures | − | − | ND | − | + | − | − | − | − | 1/8 | 3/11 |

| Microcephaly/OFC (cm) (percentile) | + 52.2 (2–10%) |

ND | ND | + 49 (25%) |

− | ND | − | − | − | 2/6 | 0/11 1 ND |

| Obesity/Weight (kg, percentile) | + 86kg (morbid obesity) |

− 23.3kg (BMI 91%) |

ND | + | − 65% |

ND | + 97% |

+ 90% |

− 50–75% |

4/7 | 2/11 |

| Height (cm) | 174 (75–90%) | 113.5 (6%) | ND | 103 (50%) | 89 (46%) | ND | ND | ND | 123 (75%) | Variable | Variable |

| Dysmorphic features | |||||||||||

| Head shape | Brachycephaly, dolichocephaly | − | ND | − | − | Sloping forehead | − | − | − | 2/8 | ND |

| Narrow palpebral fissures | + | − | ND | − | + | − | + | + | ND | 4/7 | ND |

| Downturned mouth corners | + | − | ND | − | + | − | + | + | − | 4/8 | ND |

| Wide month | + | − | ND | − | − | − | + | + | − | 3/8 | 3/8 |

| Hypertelorism | + | − | ND | − | − | − | − | − | − | 1/8 | 1/8 |

| Epicanthic folds | − | − | ND | + | + | − | + | − | − | 3/8 | 1/8 |

| Depressed nasal bridge | − | − | ND | − | − | − (high nasal bridge) | − | − | − | 0/8 | 1/8 |

| Short nose | − (long nose) | − | ND | − | − | − | − | − | − | 0/8 | 2/8 |

| Anteverted nares | − | − | ND | + | − | − | − | − | − | 1/8 | 1/8 |

| Low hanging columella | + | − | ND | − | − | − | − | − | − | 1/8 | 3/8 |

| Long philtrum | − | − | ND | − | − | − | − | − (short philtrum) | − | 0/8 | 2/8 |

| Smooth philtrum | − | − | ND | − | − | − | − | − | − | 0/8 | 2/8 |

| Thin upper lip vermilion | − (full lips) | − | ND | − | − | − | + | − | − | 1/8 | 2/8 |

| Exaggerated Cupid’s bow | − | − | ND | − | − | − | − | − | − | 0/8 | 4/8 |

| Pointed chin | − | − | ND | − | − | + | − | + | − | 2/8 | ND |

| Large ear lobe | + | − | ND | − | − | + | − | − | + | 3/8 | 3/8 |

| Low set ears | − | − | ND | − | + | − | − | − | − | 1/8 | 2/8 |

| Hand anomalies | − | − | − | − | − | − | spindle shaped fingers | − | − | ||

| Hearing loss (HL) | − | − | − | + Unilateal HL |

− | − | − | − | − | 1/9 | 0/11 |

| Brain anomalies | ND | − | ND | − | − | ND | ND | − | − | ||

Abbreviations are as follows: NA, not available; ND, not determined because of non-availability or non-applicability.

Figure 2.

Photographs of subjects 5, 7, 8, and 9 are shown. Note narrow up-slanting palpebral fissures and a distinct mouth with downturned corners. Informed consent for publication of these photographs was obtained.

Microarray and Molecular Analysis

The five deletion CNVs involving TRIP12, range in size from 20 kb to 1.7 Mb (Figure 1a). CNV deletions in subjects 1–3 removed 9 exons (exon 30–38), 17 exons (exon 25–41), and 4 exons (exon 2–5) of TRIP12, respectively, whereas the deletions in subjects 4 and 5 spanned the entire TRIP12 gene and the adjacent genes (Figure 1a). In subject 5, the 2q36.3 imbalance resulted from a translocation t(12)(p31.2;q36.3). Parental studies showed that three of the five CNVs arose de novo (subjects 1, 4, and 5); the parental samples were unavailable to evaluate inheritance for two deletion CNVs (subjects 2 and 3). No additional clinically relevant CNVs were identified in these five individuals.

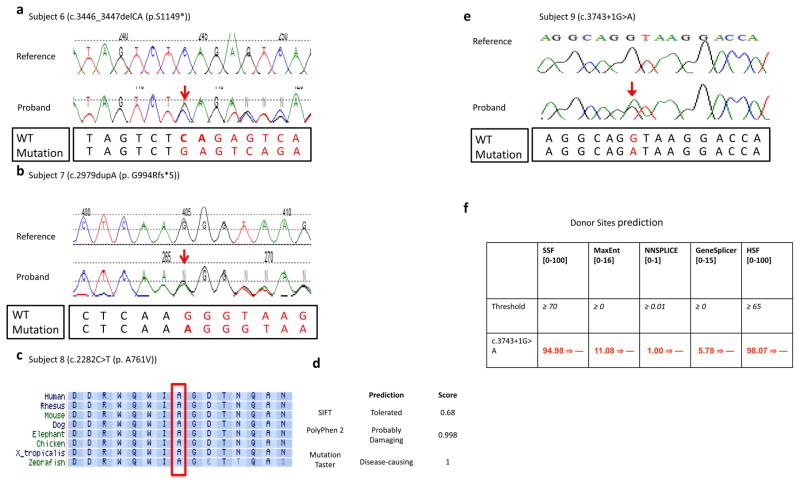

WES revealed two mutations, predicted to be truncating, c.3446_3447delCA (p.S1149X) in subject 6 and c.2979dupA (p.G994Rfs*5) in subject 7, one missense variant c.2282C>T (p.A761V) in subject 8, and splice-site mutation (c.3743+1G>A) in subject 9 (Figure 3a–c, f). With the exception of TRIP12 rare variants, no additional deleterious/disease-causing mutations in other known disease genes were identified in these four probands (Subject 6–9).

Figure 3.

(a,b) Sanger sequencing traces from subject 6 and subject 7 are presented. The WT and mutation sequences are shown separately below the Sanger traces. (c) Alignment of the TRIP12 protein sequence from multiple species around amino acid position 761 (NM_004238) that was altered from alanine to valine in subject 8. This alanine at position 761 was well conserved from human to zebrafish, and this missense change was predicted to be deleterious/disease-causing by MutationTaster and Polyphen-2 (d). (e) Chromatogram of de novo variant c.3743+1G>A and (f) results of in silico analysis of the 3743+1G>A variant found in subject 9 using five splicing prediction tools included in Alamut v2.7. The numbers in brackets indicate the value range generated by each predication tool. The threshold used by each prediction tool indicates that above this threshold the positions are predicted to be true splice-sites. The numbers in red are the actual value calculated by each prediction algorithm. All five prediction tools suggested that the donor splice site was abolished at the variant position.

The catalytic HECT ubiquitin ligase domain is located between amino acids 1590–1990, hence c.3446_3447delCA (p.S1149X) in subject 6 and c.2979dupA (p.G994Rfs*5) in subject 7 both result in loss of this domain (Figure 1c), and are predicted to cause loss of normal protein function either through nonsense mediated mRNA decay mechanism or loss of ligase function activity. Both truncating variants were confirmed by Sanger sequencing to be de novo events (Figure 3a, 3b).

The missense mutation in codon 761 (p.A761V) in subject 8, which was also confirmed to arose de novo by Sanger sequencing, is located in a highly conserved amino acid (Figure 3d) within the protein-protein interaction related WWE domain (Aravind 2001). A non-polar (alanine) to polar (threonine) change likely affected the interactions of TRIP12 with its binding partners. Two in silico prediction tools, PolyPhen-2 and MutationTaster, predicted deleterious/damaging and potentially disease causing effects of this mutation (Figure 3e).

The c.3743+1G>A de novo mutation observed in subject 9 is predicted to result in a complete loss of an invariant splice site by at least five donor site prediction tools incorporated in the Alamut software: SSF, MaxEnt, NNSPLICE, GeneSplicer, and HSF (Figure 3g). To further characterize the identified TRIP12 variant, we performed quantitative PCR on this splicing change c.3743+1G>A in the blood samples of subject 9, his both parents, and an unaffected sister. qPCR data showed dramatic reduction of TRIP12 mRNA level in the proband compared to three unaffected family member controls (Supplementary Figure S2), indicating that this splicing mutation led to loss of TRIP12 function through the nonsense mediated decay.

Together, our results implicate that all nine variants identified in subjects 1–9, represent pathogenic or likely pathogenic alleles. None of these rare TRIP12 variants, except the shared subject 8 (c.2282C>T), were observed in the common SNPs (dbSNP build 148), the 1000 Genomes, the Exome Variant Server (ESP6500), the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC), or the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC; exome data of ~ 6,000 subjects) databases (1000 Genomes Project; Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study; ExAC Brower. Exome Aggregation Consortium; NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP). Exome Variant Server). The c.2282C>T (p.A761V) change was recently seen three times in the ExAC database (Jan 31st, 2017) and four times in the gnomAD database (Jan 31st, 2017). Based on this very recent genotypic information from ExAC and gnomAD database, we re-classified this missense change as variant of unknown significance (VUS). Of note, the pLI score (Lek et al. 2016) of TRIP12 reported in ExAC database is 1.00. EXAC database uses the observed and expected variants counts to determine the probability whether a given gene is intolerant for loss-of-function variation (pLI score). The closer pLI is to one, the more LoF intolerant the gene appears to be. We consider pLI >= 0.9 as an extremely LoF intolerant. No LoF variants in TRIP12 were reported in ExAC as of January 22, 2017, whereas 76.9 variants were expected, suggesting that this gene is intolerant to LoF SNVs. The information of the four SNP variants CADD scores can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

DISCUSSION

TRIP12, an evolutionarily conserved 1992 amino acid protein that belongs to the HECT domain E3 ubiquitin ligases family, is widely expressed in various tissues. TRIP12 contains a WWE motif, predicted to mediate specific protein-protein interactions in ubiquitin and the ADP-ribose conjugation system (Aravind et al. 2001), a HECT domain, functioning as E6AP-type E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase containing a conserved cysteine residue that is necessary for the tagging of target proteins with ubiquitin, and an ARM (armadillo/β-catenin-like repeats) domain (Figure 1c) (Rotin et al. 2009).

Recent studies have revealed a few potential binding partners for TRIP12, including amyloid precursor protein-binding protein (APP-BP1) (Park et al. 2008); ADP-ribosylation factor 1 (ARF) (Chen et al. 2013; Velimezi et al. 2013); pancreas transcription factor 1a (PTF1a) (Hanoun et al. 2014); SRY (Sex determining region Y)-Box 6 (SOX6) (An et al. 2013); HECT, UBA, and WWE domain containing 1, E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (HUWE1) (Poulsen et al. 2012); and ring finger protein 168 (RNF168) (Gudjonsson et al. 2012), suggesting that TRIP12 plays an important role in a broad range of physiological processes. TRIP12 has been shown also to regulate DNA repair, cell growth, and ARF-P53 pathway related oncogenic stress (Chen et al. 2010; Chen et al. 2013; Gudjonsson et al. 2012). TRIP12 was also found to be required for the proper mouse brain development and neuronal cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis (Kajiro et al. 2011). Moreover, a recent study using RNAi cell knockdown demonstrated that TRIP12 likely functions together with HUWE1, encoded by an X-linked syndromic ID gene (MIM: 300706) in the ubiquitin fusion degradation (UFD) pathway. TRIP12 was also found to interact with APP-BP1, an important cell cycle checkpoint protein, and regulate its level of expression (Chen et al. 2000).

During this study, we also ascertained an individual with a splicing variant c.1145-2A>C in TRIP12 that was not present in his mother (see subject Suppl 1 in Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Figure S3–S6 for the detailed clinical and molecular data). The father was not available for the study. The c.1145-2A>C variant in the canonical mRNA isoform NM_004238 of TRIP12 is predicted to result in a complete loss of an invariant splice site by four acceptor site prediction tools incorporated in the Alamut software: MaxEnt, NNSPLICE, GeneSplicer and HSF (Supplementary Figure S4b). There are four verified RefSeq isoforms (NM_001284214, NM_001284215, NM_001284216, and NM_004238 used as reference isoform in this study) in TRIP12. In contrast to the c.3743+1G>A splicing mutation in subject 9, which affects all four isoforms and showed a much decreased expression level in quantitative PCR experiment (Supplementary Figure S2), the c.1145-2A>C splicing variant in subject supplementary 1, which affects only one isoform (NM_004238) and is predicted to result in synonymous changes in the other three isoforms by conceptual translation (Supplementary Figure S5), showed a similar TRIP12 RNA expression comparing to an unaffected control (Supplementary Figure S6a). These molecular findings are also consistent with the clinical features of the subject supplementary 1 with much milder neurocognitive phenotype than subject 9. Considering that the isoform-specific expression pattern in brain tissue is unknown, the pathogenicity of this splicing variant cannot be determined at this stage and thus has been classified as a variant of unknown significance.

In addition, by exploring the DECIPHER database, we have identified four individuals (DECIPHER IDs: 250590, 252476, 301556, and 281305) with CNV deletions involving TRIP12 and smaller than 1.5 Mb in size. Three of these deletions were reported as de novo events, and the inheritance of the fourth CNV (281305) has not been determined. This fourth deletion was the smallest in size (144 kb), involved only TRIP12 and FBXO36 and was detected in a 31-month-old male with psychomotor delay and non-specific asymmetric white matter (leukoencephalopathy). Multicystic renal dysplasia and renal insufficiency observed in this DECIPHER subject were consistent with the previous reports on TRIP12 CNV deletions (see Supplementary Table S1 for detailed clinical information) (Doco-Fenzy et al. 2008).

We molecularly and clinically characterized nine unrelated individuals with syndromic DD/ID, ASDs, and dysmorphic features due to heterozygous CNVs and SNVs/indels involving TRIP12. Considering ~ 60,000 and ~ 7,200 individuals who had neurological phenotypes and were studied by CMA and WES in our laboratories, the likely pathogenic TRIP12 mutations account for ~ 0.01% and ~ 0.06% rates, respectively. Our findings suggest that E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIP12 plays an important role in nervous system development and function; moreover, TRIP12 haploinsufficiency causes childhood-onset neurodevelopmental disorders. Further studies investigating the tissue specific and developmental expression of distinct TRIP12 isoforms, and exploring TRIP12 binding targets, could shed light on the pathophysiology of TRIP12-associated neurodevelopmental disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the families for participating in this study. We are most grateful to the Genomics platform of Nantes (Biogenouest Genomics) core facility for its technical support on performing exome for subject 9 and his parents. We acknowledge HUGODIMS (Western France exome based trio approach project to identify genes involved in intellectual disability). This study makes use of data generated by the DECIPHER community. A full list of centres who contributed to the generation of the data is available from http://decipher.sanger.ac.uk and via email from decipher@sanger.ac.uk. Funding for the project was provided by the Wellcome Trust. This work was supported in part by the National Human Genome Research Institute/National Heart Lung and Blood Institute grant to the Baylor-Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics [U54HG006542], and the NIH Common Fund, through the Office of Strategic Coordination/Office of the NIH Director under Award Number U01HG007709, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke R01 grant [NS058529 to J.R.L.], and a grant from the French Ministry of Health and Poitou-Charentes Regional Health Agency (HUGODIMS, 2013, RC14_0107).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

JRL has stock ownership in 23andMe and Lasergen, is a paid consultant for Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, and is a co-inventor on multiple United States and European patents related to molecular diagnostics for inherited neuropathies, eye diseases and bacterial genomic fingerprinting. The Department of Molecular and Human Genetics at Baylor College of Medicine derives revenue from the chromosomal microarray analysis and clinical exome sequencing offered by Baylor Genetics (http://bmgl.com/).

URLs

1000 Genomes Project. http://www.1000genomes.org. Accessed 11 Oct. 2016.

Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. http://www2.cscc.unc.edu/aric. Accessed 11 Oct. 2016.

ExAC Brower. Exome Aggregation Consortium. http://exac.broadinstitute.org. Accessed 11 Oct. 2016.

Mutation Taster. http://www.mutationtaster.org. Accessed 11 Oct. 2016.

NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP). Exome Variant Server. http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS. Accessed 11 Oct. 2016.

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM). http://www.omim.org. Accessed 11 Oct. 2016.

PolyPhen-2. http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2. Accessed 11 Oct. 2016.

Contributor Information

Jing Zhang, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, 77030, USA. Baylor Genetics LLC, Houston, TX, 77030, USA.

Tomasz Gambin, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, 77030, USA. Institute of Computer Science, Warsaw University of Technology, Warsaw, 02-038, Poland. Department of Medical Genetics, Institute of Mother and Child, Warsaw, 01-211, Poland.

Bo Yuan, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, 77030, USA. Baylor Genetics LLC, Houston, TX, 77030, USA.

Przemyslaw Szafranski, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, 77030, USA.

Jill A. Rosenfeld, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, 77030, USA

Mohammed Al Balwi, King Abdulaziz Medical City, Riyadh, 21423, Saudi Arabia.

Abdulrahman Alswaid, Department of Pediatrics, King Abdulaziz Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Lihadh Al-Gazali, Department of Paediatrics, Department of Pathology, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain -United Arab Emirates.

Aisha Al Shamsi, Department of Paediatrics, Department of Pathology, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain -United Arab Emirates.

Makanko Komara, Department of Paediatrics, Department of Pathology, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain -United Arab Emirates.

Bassam R. Ali, Department of Paediatrics, Department of Pathology, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain -United Arab Emirates

Elizabeth Roeder, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, 77030, USA. Departments of Pediatrics and Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, San Antonio, TX, 78230, USA.

Laura McAuley, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Children’s Health Children’s Medical Center Dallas, TX, 75235, USA.

Daniel S. Roy, Tripler Army Medical Center, Honolulu, 96859, USA

David K. Manchester, Genetics & Metabolism, Children’s Hospital, Aurora, CO, 80045, USA

Pilar Magoulas, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, 77030, USA.

Lauren E. King, Vanderbilt Children’s Hospital, Nashville, TN, 37232, USA

Vickie Hannig, Vanderbilt Children’s Hospital, Nashville, TN, 37232, USA.

Dominique Bonneau, Department of Biochemistry and Genetics, University Hospital, 49933 Angers Cedex 9, France. UMR CNRS 6015-INSERM 1083 and PREMMI, University of Angers, 49933 Angers Cedex 9, France.

Anne-Sophie Denommé-Pichon, Department of Biochemistry and Genetics, University Hospital, 49933 Angers Cedex 9, France. UMR CNRS 6015-INSERM 1083 and PREMMI, University of Angers, 49933 Angers Cedex 9, France.

Majida Charif, UMR CNRS 6015-INSERM 1083 and PREMMI, University of Angers, 49933 Angers Cedex 9, France.

Thomas Besnard, CHU Nantes, Service de Génétique Médicale, 9 quai Moncousu, 44093 Nantes CEDEX 1, France.

Stéphane Bézieau, CHU Nantes, Service de Génétique Médicale, 9 quai Moncousu, 44093 Nantes CEDEX 1, France.

Benjamin Cogné, CHU Nantes, Service de Génétique Médicale, 9 quai Moncousu, 44093 Nantes CEDEX 1, France.

Joris Andrieux, Institute of Medical Genetics, Jeanne de Flandre Hospital, Lille University Hospital, Lille, 59800, France.

Wenmiao Zhu, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, 77030, USA. Baylor Genetics LLC, Houston, TX, 77030, USA.

Weimin He, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, 77030, USA. Baylor Genetics LLC, Houston, TX, 77030, USA.

Francesco Vetrini, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, 77030, USA. Baylor Genetics LLC, Houston, TX, 77030, USA.

Patricia A. Ward, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, 77030, USA. Baylor Genetics LLC, Houston, TX, 77030, USA

Sau Wai Cheung, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, 77030, USA. Baylor Genetics LLC, Houston, TX, 77030, USA.

Weimin Bi, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, 77030, USA. Baylor Genetics LLC, Houston, TX, 77030, USA.

Christine M. Eng, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, 77030, USA. Baylor Genetics LLC, Houston, TX, 77030, USA

James R. Lupski, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, 77030, USA. Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, 77030, USA. Human Genome Sequencing Center, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, 77030, USA. Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX, 77030, USA

Yaping Yang, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, 77030, USA. Baylor Genetics LLC, Houston, TX, 77030, USA.

Ankita Patel, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, 77030, USA. Baylor Genetics LLC, Houston, TX, 77030, USA.

Seema R. Lalani, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, 77030, USA. Baylor Genetics LLC, Houston, TX, 77030, USA

Fan Xia, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, 77030, USA. Baylor Genetics LLC, Houston, TX, 77030, USA.

Pawel Stankiewicz, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, 77030, USA. Baylor Genetics LLC, Houston, TX, 77030, USA.

References

- An CI, Ganio E, Hagiwara N. Trip12, a HECT domain E3 ubiquitin ligase, targets Sox6 for proteasomal degradation and affects fiber type-specific gene expression in muscle cells. Skelet Muscle. 2013;3:11. doi: 10.1186/2044-5040-3-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravind L. The WWE domain: a common interaction module in protein ubiquitination and ADP ribosylation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:273–5. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01787-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone PM, Bacino CA, Shaw CA, Eng PA, Hixson PM, Pursley AN, AN, Kang SH, Yang Y, Wiszniewska J, Nowakowska BA, del Gaudio D, Xia Z, Simpson-Patel G, Immken LL, Gibson JB, Tsai AC, Bowers JA, Reimschisel TE, Schaaf CP, Potocki L, Scaglia F, Gambin T, Sykulski M, Bartnik M, Derwinska K, Wisniowiecka-Kowalnik B, Lalani SR, Probst FJ, Bi W, Beaudet AL, Patel A, Lupski JR, Cheung SW, Stankiewicz P. Detection of clinically relevant exonic copy-number changes by array CGH. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:1326–42. doi: 10.1002/humu.21360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramswig NC, Lüdecke HJ, Pettersson M, Albrecht B, Bernier RA, Cremer K, Eichler EE, Falkenstein D, Gerdts J, Jansen S, Kuechler A, Kvarnung M, Lindstrand A, Nilsson D, Nordgren A, Pfundt R, Spruijt L, Surowy HM, de Vries BB, Wieland T, Engels H, Strom TM, Kleefstra T, Wieczorek D. Identification of new TRIP12 variants and detailed clinical evaluation of individuals with non-syndromic intellectual disability with or without autism. Hum Genet. 2016 Nov 15; doi: 10.1007/s00439-016-1743-x. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Kon N, Zhong J, Zhang P, Yu L, Gu W. Differential effects on ARF stability by normal versus oncogenic levels of c-Myc expression. Mol Cell. 2013;51:46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Shan J, Zhu WG, Qin J, Gu W. Transcription-independent ARF regulation in oncogenic stress-mediated p53 responses. Nature. 2010;464:624–7. doi: 10.1038/nature08820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, McPhie DL, Hirschberg J, Neve RL. The amyloid precursor protein-binding protein APP-BP1 drives the cell cycle through the S-M checkpoint and causes apoptosis in neurons. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8929–8935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doco-Fenzy M, Landais E, Andrieux J, Schneider A, Delemer B, Sulmont V, Melin JP, Ploton D, Thevenard J, Monboisse JC, Belouadah M, Lefebvre F, Durlach A, Goossens M, Albuisson J, Motte J, Gaillard D. Deletion 2q36.2q36.3 with multiple renal cysts and severe mental retardation. Eur J Med Genet. 2008;51:598–607. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudjonsson T, Altmeyer M, Savic V, Toledo L, Dinant C, Grøfte M, Bartkova J, Poulsen M, Oka Y, Bekker-Jensen S, Mailand N, Neumann B, Heriche JK, Shearer R, Saunders D, Bartek J, Lukas J, Lukas C. TRIP12 and UBR5 suppress spreading of chromatin ubiquitylation at damaged chromosomes. Cell. 2012;150:697–709. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanoun N, Fritsch S, Gayet O, Gigoux V, Cordelier P, Dusetti N, Torrisani J, Dufresne M. The E3 ubiquitin ligase thyroid hormone receptor-interacting protein 12 targets pancreas transcription factor 1a for proteasomal degradation. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:35593–604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.620104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajiro M, Tsuchiya M, Kawabe Y, Furumai R, Iwasaki N, Hayashi Y, et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of Trip12 is essential for mouse embryogenesis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25871. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, Samocha KE, Banks E, Fennell T, O’Donnell-Luria AH, Ware JS, Hill AJ, Cummings BB, Tukiainen T, Birnbaum DP, Kosmicki JA, Duncan LE, Estrada K, Zhao F, Zou J, Pierce-Hoffman E, Berghout J, Cooper DN, Deflaux N, DePristo M, Do R, Flannick J, Fromer M, Gauthier L, Goldstein J, Gupta N, Howrigan D, Kiezun A, Kurki MI, Moonshine AL, Natarajan P, Orozco L, Peloso GM, Poplin R, Rivas MA, Ruano-Rubio V, Rose SA, Ruderfer DM, Shakir K, Stenson PD, Stevens C, Thomas BP, Tiao G, Tusie-Luna MT, Weisburd B, Won HH, Yu D, Altshuler DM, Ardissino D, Boehnke M, Danesh J, Donnelly S, Elosua R, Florez JC, Gabriel SB, Getz G, Glatt SJ, Hultman CM, Kathiresan S, Laakso M, McCarroll S, McCarthy MI, McGovern D, McPherson R, Neale BM, Palotie A, Purcell SM, Saleheen D, Scharf JM, Sklar P, Sullivan PF, Tuomilehto J, Tsuang MT, Watkins HC, Wilson JG, Daly MJ, MacArthur DG Exome Aggregation Consortium. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–91. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelieveld SH, Reijnders MR, Pfundt R, Yntema HG, Kamsteeg EJ, de Vries P, de Vries BB, Willemsen MH, Kleefstra T, Löhner K, Vreeburg M, Stevens SJ, van der Burgt I, Bongers EM, Stegmann AP, Rump P, Rinne T, Nelen MR, Veltman JA, Vissers LE, Brunner HG, Gilissen C. Meta-analysis of 2,104 trios provides support for 10 new genes for intellectual disability. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:1194–6. doi: 10.1038/nn.4352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oikonomakis V, Kosma K, Mitrakos A, Sofocleous C, Pervanidou P, Syrmou A, Pampanos A, Psoni S, Fryssira H, Kanavakis E, Kitsiou-Tzeli S, Tzetis M. Recurrent copy number variations as risk factors for autism spectrum disorders: analysis of the clinical implications. Clin Genet. 2016;89:708–18. doi: 10.1111/cge.12740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Roak BJ, Stessman HA, Boyle EA, Witherspoon KT, Martin B, Lee C, Vives L, Baker C, Hiatt JB, Nickerson DA, Bernier R, Shendure J, Eichler EE. Recurrent de novo mutations implicate novel genes underlying simplex autism risk. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5595. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y, Yoon SK, Yoon JB. TRIP12 functions as an E3 ubiquitin ligase of APP-BP1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;374:294–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto D, Delaby E, Merico D, Barbosa M, Merikangas A, Klei L, Thiruvahindrapuram B, Xu X, Ziman R, Wang Z, Vorstman JA, Thompson A, Regan R, Pilorge M, Pellecchia G, Pagnamenta AT, Oliveira B, Marshall CR, Magalhaes TR, Lowe JK, Howe JL, Griswold AJ, Gilbert J, Duketis E, Dombroski BA, De Jonge MV, Cuccaro M, Crawford EL, Correia CT, Conroy J, Conceição IC, Chiocchetti AG, Casey JP, Cai G, Cabrol C, Bolshakova N, Bacchelli E, Anney R, Gallinger S, Cotterchio M, Casey G, Zwaigenbaum L, Wittemeyer K, Wing K, Wallace S, van Engeland H, Tryfon A, Thomson S, Soorya L, Rogé B, Roberts W, Poustka F, Mouga S, Minshew N, McInnes LA, McGrew SG, Lord C, Leboyer M, Le Couteur AS, Kolevzon A, Jiménez González P, Jacob S, Holt R, Guter S, Green J, Green A, Gillberg C, Fernandez BA, Duque F, Delorme R, Dawson G, Chaste P, Café C, Brennan S, Bourgeron T, Bolton PF, Bölte S, Bernier R, Baird G, Bailey AJ, Anagnostou E, Almeida J, Wijsman EM, Vieland VJ, Vicente AM, Schellenberg GD, Pericak-Vance M, Paterson AD, Parr JR, Oliveira G, Nurnberger JI, Monaco AP, Maestrini E, Klauck SM, Hakonarson H, Haines JL, Geschwind DH, Freitag CM, Folstein SE, Ennis S, Coon H, Battaglia A, Szatmari P, Sutcliffe JS, Hallmayer J, Gill M, Cook EH, Buxbaum JD, Devlin B, Gallagher L, Betancur C, Scherer SW. Convergence of genes and cellular pathways dysregulated in autism spectrum disorders. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94:677–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen EG, Steinhauer C, Lees M, Lauridsen AM, Ellgaard L, Hartmann-Petersen R. HUWE1 and TRIP12 collaborate in degradation of ubiquitin-fusion proteins and misframed ubiquitin. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50548. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotin D, Kumar S. Physiological functions of the HECT family of ubiquitin ligases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:398–409. doi: 10.1038/nrm2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velimezi G, Liontos M, Vougas K, Roumeliotis T, Bartkova J, Sideridou M, Dereli-Oz A, Kocylowski M, Pateras IS, Evangelou K, Kotsinas A, Orsolic I, Bursac S, Cokaric-Brdovcak M, Zoumpourlis V, Kletsas D, Papafotiou G, Klinakis A, Volarevic S, Gu W, Bartek J, Halazonetis TD, Gorgoulis VG. Functional interplay between the DNA-damage-response kinase ATM and ARF tumour suppressor protein in human cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:967–77. doi: 10.1038/ncb2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiszniewska J, Bi W, Shaw C, Stankiewicz P, Kang SH, Pursley AN, Lalani S, Hixson P, Gambin T, Tsai CH, Bock HG, Descartes M, Probst FJ, Scaglia F, Beaudet AL, Lupski JR, Eng C, Cheung SW, Bacino C, Patel A. Combined array CGH plus SNP genome analyses in a single assay for optimized clinical testing. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22:79–87. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Muzny DM, Xia F, Niu Z, Person R, Ding Y, Ward P, Braxton A, Wang M, Buhay C, Veeraraghavan N, Hawes A, Chiang T, Leduc M, Beuten J, Zhang J, He W, Scull J, Willis A, Landsverk M, Craigen WJ, Bekheirnia MR, Stray-Pedersen A, Liu P, Wen S, Alcaraz W, Cui H, Walkiewicz M, Reid J, Bainbridge M, Patel A, Boerwinkle E, Beaudet AL, Lupski JR, Plon SE, Gibbs RA, Eng CM. Molecular findings among patients referred for clinical whole-exome sequencing. JAMA. 2014;312:1870–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.14601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.