Abstract

Mammalian cell division is thought to be driven by sequential activation of several Cyclin‐dependent kinases (Cdk), mainly Cdk4, Cdk6, Cdk2 and Cdk1. Since mice lacking Cdk4, Cdk6 or Cdk2 are viable, it has been proposed that they play compensatory roles. We report here that mice lacking Cdk4 and Cdk2 complete embryonic development to die shortly thereafter presumably due to heart failure. However, conditional ablation of Cdk2 in adult mice lacking Cdk4 does not result in obvious abnormalities. Moreover, these double mutant mice recover normally after partial hepatectomy. In culture, Cdk4−/−;Cdk2−/−embryonic fibroblasts become immortal, display robust pRb phosphorylation and have normal S phase kinetics. These observations indicate that Cdk4 and Cdk2 are dispensable for the mammalian cell cycle and for adult homeostasis.

Keywords: Cyclin-dependent kinases, Mouse development, Cell proliferation, Conditional knock outs, Liver regeneration

1. Introduction

The widely accepted model for the mammalian cell cycle involves sequential activation of related heterodimeric protein kinases, composed of a catalytic subunit, the Cyclin‐dependent kinase (Cdk), and a regulatory subunit known as Cyclin (reviewed in Malumbres and Barbacid, 2005). Two of these Cdks, Cdk4 and Cdk6, are activated by the D‐type Cyclins and have been implicated in the early phases of the cycle, particularly during exit from quiescence. Cdk4/6‐Cyclin D heterodimeric kinases are supposed to promote re‐entry into the cycle by initiating phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma (Rb) protein family, pRb, p107 and p130 (reviewed in Adams, 2001; Sherr and Roberts, 1999). Rb phosphorylation results in the liberation of transcription factors, such as members of the E2F family (reviewed in Dyson, 1998; Trimarchi and Lees, 2002), which are bound to the hypophosphorylated Rb proteins in non‐proliferating cells. These transcription factors are responsible for directing the expression of a variety of genes essential for advancing cells though the S phase of the cell cycle (Adams, 2001). Two of these genes encode Cyclins E1 and E2 which specifically bind to Cdk2. Active Cdk2–Cyclin E complexes further phosphorylate the Rb protein family, resulting in their complete inactivation. This process is considered to be essential for the liberation of transcription factors that mediate the synthesis of other cell cycle regulators such as the A‐type Cyclins and Cdk1. Sequential activation of Cdk2 and Cdk1 by the A‐type Cyclins is believed to be essential for the successful duplication of the cellular genome during the S phase and for progression into mitosis (Dyson, 1998; Trimarchi and Lees, 2002).

This model, mainly deduced from biochemical evidence, has not sustained genetic scrutiny. For instance, all mouse cell types, with the exception of pancreatic beta cells and pituitary lactotrophs proliferate normally in the absence of Cdk4 (Rane et al., 1999; Tsutsui et al., 1999). Likewise, ablation of Cdk6 only results in reduction of a subset of hematopoietic cells (Malumbres et al., 2004). Loss of both of these enzymes causes a much more dramatic phenotype that limits the proliferation of hematopoietic cell lineages leading to late embryonic lethality (Malumbres et al., 2004). Yet, double mutant embryos show normal proliferation rates in other tissues, indicating that Cdk4 and Cdk6 only play compensatory roles in cells of hematopoietic lineages. In agreement with these observations, mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) lacking Cdk4 and Cdk6 proliferate well and become immortal upon continuous culture in vitro. More importantly, they exit quiescence upon mitogenic stimuli and enter S phase with normal kinetics (Malumbres et al., 2004). Similar results have been obtained in mice lacking the three D‐type Cyclins (Kozar et al., 2004). Likewise, Cdk2, a kinase previously thought to be essential for driving cells through the G1/S transition, is dispensable for normal embryonic development and adult homeostasis (Berthet et al., 2003; Ortega et al., 2003). Unexpectedly, Cdk2 is essential for the first meiotic division of both male and female germ cells, an activity that cannot be compensated by any of the other Cdks (Ortega et al., 2003).

These observations have been attributed, at least in part to compensatory activities between Cdk2 and Cdk4. In this manuscript, we report the generation and characterization of mice carrying germ line as well as conditional mutations in the loci encoding these kinases. Mice lacking Cdk4 and Cdk2 in the germ line complete embryonic development and are born alive. Although they die soon thereafter possibly due to their limited numbers of cardiomyocytes, the rest of the tissues display normal levels of cell proliferation. More importantly, conditional ablation of Cdk2 in adult Cdk4 knock out mice does not result in detectable abnormalities even in highly proliferating tissues. Indeed, these double mutant mice efficiently regenerate their livers after partial hepatectomy (PH). These observations indicate that Cdk4 and Cdk2 are dispensable for mammalian cell division and raise further questions about their proposed role in driving the mammalian cell cycle.

2. Results

2.1. Complete embryonic development in the absence of Cdk4 and Cdk2

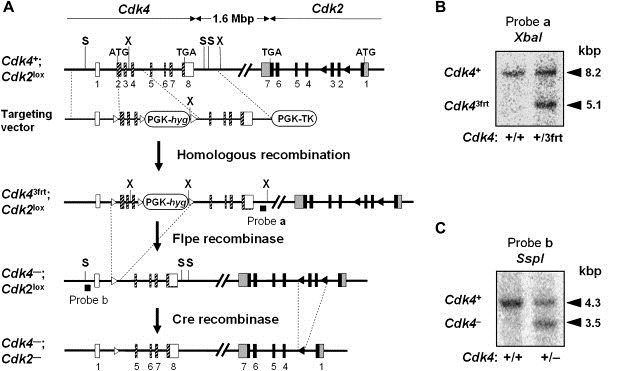

We have generated double mutant Cdk4 +/−;Cdk2 +/lox and Cdk4 +/−;Cdk2 +/− mice by targeting the Cdk4 locus in ES cells carrying a conditional Cdk2 lox allele (Figure 1). Intercrosses between Cdk4 +/−;Cdk2 +/− double heterozygous animals result in the generation of midgestation (E13.5) Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− embryos with Mendelian ratios (41/165, 25%). More importantly, a significant percentage of these embryos (about 40%) complete embryonic development. Newborn Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− mice weigh 25–40% less than their wild type littermates, a reduction in weight slightly more pronounced than that reported for mice lacking Cdk4 alone (20–25%) (Tsutsui et al., 1999; our unpublished observations). Importantly, neonatal Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− animals move normally and ingest milk. Yet, they die within 24h after birth.

Figure 1.

Generation of Cdk4−/−;Cdk2lox/lox and Cdk4−/−;Cdk2−/− mice. (A) Targeting strategy. The targeting vector carries three frt sequences flanking exons 2 and 4 as well as a PGK‐HygR cassette used for positive selection. The vector also contains a PGK‐TK cassette used for negative selection. Recombinant ES cell clones containing a floxed Cdk2lox allele were used to generate mice carrying the Cdk43frt and Cdk2lox alleles in the same chromosome. These mice were sequentially crossed with transgenic mice expressing the Flpe (pCAG‐Flpe) and Cre (CMV‐Cre) recombinases to generate heterozygous Cdk4−/−;Cdk2−/− mice. Cdk4 coding sequences are indicated by hatched boxes. Cdk4 non‐coding exons are indicated by open boxes. Cdk2 coding sequences are indicated by black boxes. Cdk2 non‐coding exons are indicated by grey boxes. frt and loxP sites are indicated by open and closed triangles, respectively. Only the restriction sites used in these diagnostic hybridizations are indicated. The location of probes a and b used in Southern blot analysis is indicated by a thick line. (B) Southern blot analysis to identify the Cdk43frt recombinant allele. (C) Southern blot analysis to identify the Cdk4−null allele.

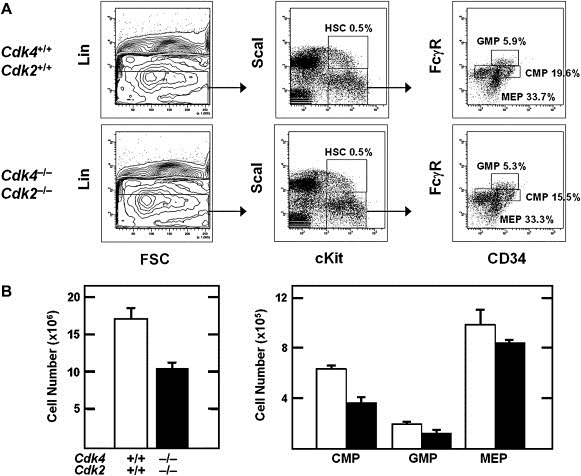

Histological analysis indicate that organogenesis is not significantly affected in newborn Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− mice. Moreover, they display normal levels of proliferating (Ki67) and apoptotic (TUNEL, active Caspase 3) cells in all tissues examined (data not shown), except in heart (see below). Previous studies with double Cdk mutant mice have revealed strong compensatory activities in the hematopoietic system between Cdk4 and Cdk6, but not between Cdk2 and Cdk6 (Malumbres et al., 2004). To determine the extent of compensation between Cdk2 and Cdk4 in hematopoietic cells we analyzed peripheral blood and fetal liver from late embryos for comparative purposes. Cdk4 −/−;Cdk6 −/− embryos die during late embryonic development due to anemia caused by limited proliferation of erythroid progenitors (Malumbres et al., 2004). In contrast, the relative levels of white and red blood cells in E17.5 Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− embryos were basically normal except for a small decrease in the number of red blood cells (1.27×106±0.14 RBC/mm3 versus 1.45×106±0.11 RBC/mm3 in wild type mice, n=3) that did not affect viability. Analysis of hematopoietic precursors by flow cytometry revealed that the relative percentages of hematopoietic stem cells (HSC), granulocyte‐macrophage progenitors (GMP), common myeloid progenitors (CMP) and megakaryocyte‐erythroid progenitors (MEP) in Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− embryos were very similar to those of wild type littermates (Figure 2A). Similar results were obtained with P1 neonatal mutants (data not shown). Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− fetal livers displayed about 60% the number of cells of livers isolated from wild type embryos, a reduction proportional to the smaller size of these double mutant embryos (Figure 2B, left). Accordingly, the total numbers of hematopoietic progenitors per liver was also reduced to a similar extent (Figure 2B, right). These observations contrast with those observed in embryos defective for Cdk4 and Cdk6 which displayed about one‐tenth the numbers of GMP and CMP precursors and about half of MEP progenitors (Malumbres et al., 2004). Thus, Cdk4 and Cdk2 do not play compensatory roles in embryonic and neonatal hematopoietic cells, indicating that these cells proliferate well with just one interphase kinase, either Cdk4 (in Cdk6 and Cdk2 double knock out mice) or Cdk6 (in the Cdk4 and Cdk2 double knock out mice described here).

Figure 2.

Analysis of hematopoietic stem cells and lineage committed progenitors in late gestation embryos. (A) Cells were isolated from fetal livers of E17.5 embryos and analysed by flow cytometry. Relative percentages of hematopoietic stem cells (HSC), granulocyte‐macrophage progenitors (GMP), common myeloid progenitors (CMP) and megakaryocyte‐erythroid progenitors (MEP) are shown. (B) Left panel shows absolute cell numbers per fetal liver of wild type (empty boxes) and Cdk4−/−;Cdk2−/− (solid boxes) embryos. Right panel shows total numbers of GMP, CMP and MEP populations calculated per liver. Solid boxes represent samples obtained from Cdk4−/−;Cdk2−/− embryos and empty boxes represent wild type littermates. Error bars: SD.

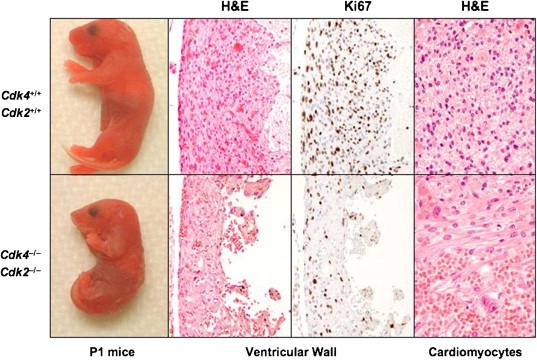

Newborn Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− mice show thinning of their ventricular walls due to a decrease in the number of proliferating cardiomyocytes (Figure 3). Quantitative analysis of Ki67 staining revealed about one‐third the number of proliferating cells in the ventricular walls of mutant hearts (Figure 3). No significant differences in apoptosis levels were observed between mutant and wild type hearts (data not shown). In some cases, Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− cardiomyocytes had an enlarged phenotype suggesting a hypertrophic, adaptive response (Figure 3). Moreover, these cardiomyocytes were partially disorganized by prominent capillaries. These observations suggest that Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− mice may not be able to sustain the major hemodynamic changes that take place at birth and die of cardiac failure. Indeed, newborn Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− mice have congestive livers (data not shown), a defect that reinforces the cardiac failure hypothesis.

Figure 3.

Mice lacking Cdk4 and Cdk2 develop to term but die soon after birth due to cardiac failure. (Left) Representative images of Cdk4+/+;Cdk2+/+ (top) and Cdk4−/−;Cdk2−/− (bottom) P1 mice. Microscopic images from these mice showing (center left) H&E staining (×200) and (center right) Ki67 immunostaining of serial sections of ventricular walls (×200), and (right) H&E staining of the myocardium showing partially disorganized and enlarged cardiomyocytes with prominent capillaries (×400).

2.2. Expression of cell cycle regulators

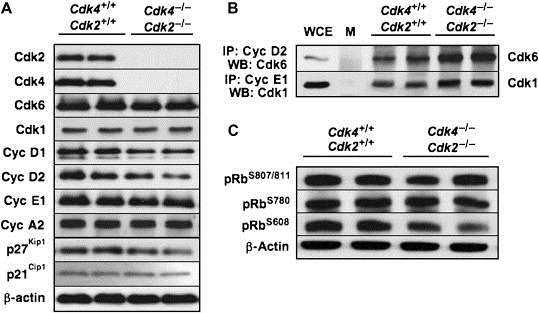

To understand the molecular mechanisms responsible for the absence of major developmental and proliferative defects in Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− double mutant mice, we examined the expression levels of other cell cycle regulators. To prevent possible indirect effects of damage suffered during delivery, we used late embryos (E17.5 or E18.5) to carry out these studies. As illustrated in Figure 4A, concomitant loss of Cdk4 and Cdk2 does not result in significant changes in the levels of Cdk6 and Cdk1, the two additional kinases implicated in driving the cell cycle. Likewise, all the Cyclins tested, including Cyclin D1 and D2, Cyclin E1 and Cyclin A2, display normal levels of expression. The steady state levels of the cell cycle inhibitors p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 also remain unchanged (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Biochemical characterization of cell cycle regulators in embryos lacking Cdk4 and Cdk2. (A) Expression levels of cell cycle regulators in wild type (Cdk4+/+;Cdk2+/+) and mutant (Cdk4−/−;Cdk2−/−) E17.5 embryos. Protein extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies elicited against the indicated proteins. (B) Cyclin D2/Cdk6 and Cyclin E1–Cdk1 complexes were immunoprecipitated with antibodies against Cyclin D2 or Cyclin E1 and analyzed by immunoblotting using antisera against Cdk6 or Cdk1, respectively. M: mock immunoprecipitates; WCE: whole cell extract at 1:20 of starting material prior to immunoprecipitation. (C) Analysis of pRb phosphorylation levels using antibodies specific for phosphorylated residues S807/811, S780 or S608.

We also examined how the absence of Cdk4 and Cdk2 affected the formation of Cyclin–Cdk complexes and the inactivation of pRb, a requirement for progression into the S phase. As shown in Figure 4B, we observed increased levels of Cyclin D2 complexed with Cdk6 and increased binding of Cyclin E1 to Cdk1, a non‐canonical Cyclin–Cdk complex recently reported by Aleem et al. (2005). Surprisingly, these double mutant embryos displayed normal levels of pRb phosphorylation. Moreover, phosphorylation of pRb occurs at residues S807/811 and S780, three sites known to be specifically phosphorylated by Cyclin D–Cdk4 complexes (Figure 4C). Likewise, pRb is also phosphorylated at residue S608 in Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− late embryos, a residue known to be the target of Cdk2 (Figure 4C). These observations suggest that Cyclin D–Cdk6 and Cyclin E–Cdk1 complexes may contribute to drive cell division by phosphorylating pRb at canonical sites in the absence of Cdk4 and Cdk2.

2.3. Immortalization of mouse embryonic fibroblasts

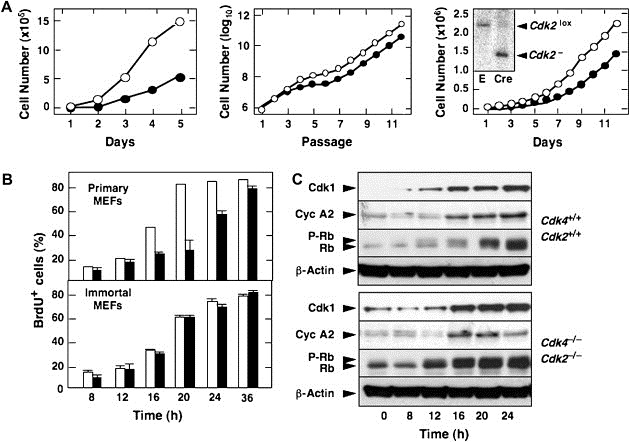

Proliferation of primary MEFs lacking either Cdk4 or Cdk2 is less robust than proliferation of wild type cells (Berthet et al., 2003; Ortega et al., 2003; Rane et al., 1999; Tsutsui et al., 1999). Concomitant loss of both kinases results in further decrease in their proliferation rate (Figure 5A, left). Primary Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− MEFs display delayed entry into S phase, although the percentage of cells that enter S phase eventually equals that of wild type MEFs (Figure 4B, top). More importantly, most of our cultures, 8 out of 10 embryos under classical culture conditions using 20% oxygen and four out of four embryos in low percent (3%) oxygen, became immortal upon continuous passage following a standard 3T3 protocol (Figure 4A, middle). These observations indicate that embryonic cells in culture can proliferate and become immortal in spite of lacking the two main Cdks implicated in the interphase (G1 phase, G1/S transition and S phase) of the cell cycle.

Figure 5.

Proliferative properties of primary and immortal MEFs. (A) Left panel shows proliferation of primary MEFs at passage 2. Center panel shows immortalization of primary MEFs by continuous passage following a classical 3T3 protocol. Cdk4 +/+;Cdk2 +/+ (open circles) and Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− (filled circles). Left panel shows proliferation of immortal Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 lox/lox MEFs infected with empty virus (open circles) or with virus expressing Cre recombinase (filled circles). Insert shows a Southern blot depicting complete cleavage of the Cdk2 lox allele in MEFs infected with virus expressing Cre recombinase (E, empty infected). (B) Percentage of quiescent Cdk4 +/+;Cdk2 +/+ (open bars) and Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− (filled bars) MEFs entering S phase upon addition of serum in the presence of 50 mM BrdU. Top panel shows results with primary MEFs. Bottom panel shows results with immortal MEFs. Error bars: SD. (C) Expression of Cdk1, Cyclin A2 (Cyc A2), hypophosphorylated (Rb) and phosphorylated (P‐Rb) forms of pRb in immortal MEFs at the indicated times after the addition of serum. β‐Actin serves as loading control.

To rule out that the ability of these cells to proliferate in culture was due to the rapid accumulation of mutations and/or epigenetic alterations during the immortalization protocol, we acutely ablated the Cdk2 locus in immortal Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 lox/lox MEFs. These cells do not contain mutations in either the INK4a/Arf or the P53 loci (data not shown). As illustrated in Figure 5A (right), acute removal of the floxed Cdk2 locus by infecting Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 lox/lox MEFs with a retrovirus expressing the bacteriophage Cre recombinase failed to significantly reduce their proliferation rate. Thus, Cdk4 and Cdk2 ameliorate the adaptation process, also known as “culture shock”, that MEFs must endure when transferred from the developing embryo to a Petri dish. However, these kinases are dispensable for proper proliferation of these cells once they have become adapted to grow under in vitro culture conditions.

Immortal Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− MEFs respond efficiently to mitogenic signals as illustrated by their normal kinetics in entering S phase (Figure 5B, bottom). These double mutant cells also display robust and timely pRb phosphorylation following serum stimulation (Figure 5C). E2F targets such as Cyclin A2 are also expressed with kinetics indistinguishable from wild type controls. Interestingly, induction of Cdk1, which has been shown to be partially dependent on E2F activity, also occurs normally (Figure 5C).

2.4. Ablation of Cdk4 and Cdk2 in adult mice

Most studies using genetic approaches in mice are limited to embryonic development, in particular when the targeted mutations result in a lethal phenotype. Thus, we examined whether the early postnatal death of Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− double mutant mice was due to an intrinsic cell cycle deficiency or to a developmental defect in specific lineages such as cardiomyocytes by ablating the Cdk2 locus in adult mice. To this end, we generated compound Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 lox/lox;RERT ert/ert animals (see Section 4) in which the Cdk2 lox alleles can be knocked out upon activation of the inducible CreERT2 recombinase (Feil et al., 1996) encoded by the ert allele. This allele drives CreERT2 expression from the locus encoding the large subunit of RNA polymerase II by an IRES‐dependent bi‐cistronic strategy and it is expressed in most, if not all cell types (Guerra et al., 2003).

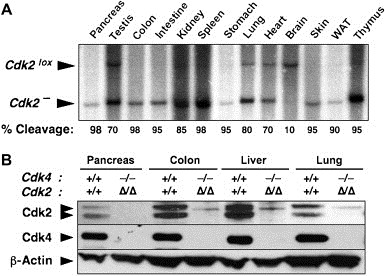

Weaned (P21) Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 lox/lox;RERT ert/ert mice were exposed to 4‐hydroxy‐tamoxifen (4OHT) for 4 months (1mg, twice a week) to allow efficient cleavage of the conditional Cdk2 lox alleles. As illustrated in Figure 6A, ≥95% of the conditional Cdk2 lox has recombined to generate the null allele in many tissues, including colon, pancreas, skin, small intestine, spleen, stomach and thymus. Other tissues such as heart, kidney, lung, testis and white adipose tissue displayed recombination levels ranging from 70 to 90%. Only brain contained minimal levels of recombined Cdk2 − allele, a consequence of the limited penetrability of 4OHT through the blood/brain barrier (Figure 6A). Ablation of Cdk2 expression in some of the tissues displaying high percentage of Cdk2 lox recombination, including colon, liver, lung and pancreas was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Figure 6B). These 4OHT‐treated Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 lox/lox;RERT ert/ert mice will be designated from now on as Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 Δ/Δ;RERT ert/ert. Cdk4 +/+;Cdk2 +/+;RERT ert/ert animals submitted to the same 4OHT treatment were used as controls.

Figure 6.

Generation of adult mice lacking Cdk4 and Cdk2. (A) Levels of excision of the conditional Cdk2lox alleles in Cdk4−/−;Cdk2lox/lox;RERTert/ert exposed to 4OHT for 4 months. DNA was isolated from the indicated tissues of the resulting Cdk4−/−;Cdk2Δ/Δ;RERTert/ert mice and analyzed by Southern blot. The migration of the conditional Cdk2lox and null Cdk2− alleles is indicated by arrowheads. The percentage of recombined Cdk2− allele in each of the tissues is indicated at the bottom. (B) Immunoblot analysis of the levels of expression Cdk4 and Cdk2 in some of the tissues shown in (A). As controls, we used extracts from the same tissues obtained from Cdk4+/+;Cdk2+/+;RERTert/ert mice treated with 4OHT. β‐Actin served as loading control.

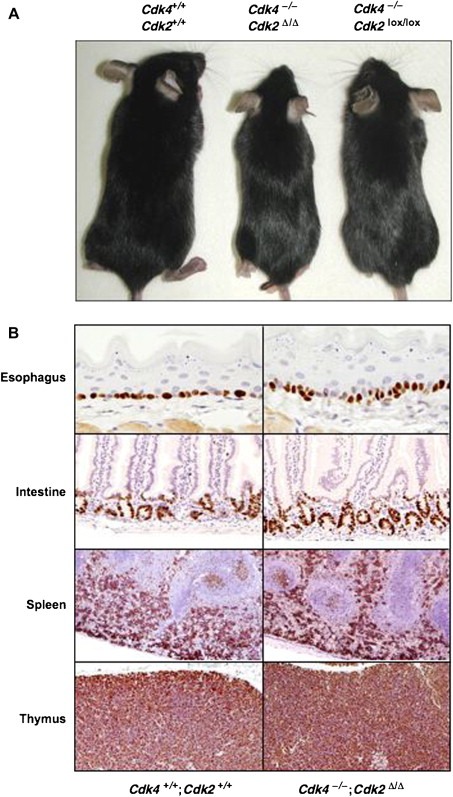

Despite complete or near complete ablation of Cdk2 in most tissues, Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 Δ/Δ;RERT ert/ert mice did not display obvious phenotypic deficiencies when compared to control Cdk4 +/+;Cdk2 +/+;RERT ert/ert mice submitted to the same 4OHT treatment (Figure 7A), except for those defects associated with loss of Cdk4 such as small size and diabetes (Rane et al., 1999; Tsutsui et al., 1999). Moreover, comparative analysis of the proliferation rates in all tissues examined by Ki67 immunostaining did not reveal significant differences. These results were most illustrative in tissues such as the esophagus (stratum germinativum) or intestine known for their active epithelial cell renewal (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Normal adult homeostasis and cell proliferation levels in tissues of Cdk4−/−;Cdk2Δ/Δ;RERTert/ert mice. (A) Five‐month‐old Cdk4+/+;Cdk2+/+;RERTert/ert, Cdk4−/−;Cdk2Δ/Δ;RERTert/ert and Cdk4−/−;Cdk2lox/lox;RERTert/ert mice. The Cdk4+/+;Cdk2+/+;RERTert/ert and the Cdk4−/−;Cdk2Δ/Δ;RERTert/ert mice were treated with 4OHT, whereas the Cdk4−/−;Cdk2lox/lox;RERTert/ert mouse was treated with oil. (B) Ki67 immunostaining of the indicated tissues obtained from 5‐month‐old 4OHT‐treated Cdk4+/+;Cdk2+/+;RERTert/ert and Cdk4−/−;Cdk2Δ/Δ;RERTert/ert mice. Esophagus: most of the stratum germinativum cells are proliferative (×400). Small intestine: proliferative cells are restricted to the lower part of the intestinal crypts (×200). Spleen: strong proliferation in the red pulp indicative of an active hematopoiesis. Most of the lymphoid cells in the white pulp are quiescent except those forming germinal centers (×50). Thymus: most thymocytes in the cortex are positive for Ki67 immunostaining (×100). The presence of the ert alleles in the description of the genotypes in the figure has been omitted for clarity.

2.5. Adult hematopoiesis in the absence of Cdk4 and Cdk2

Likewise, lympho‐hematopoietic organs such as spleen and thymus known for their continuous production of lymphoid or hematopoietic cells, also display normal proliferation levels (Figure 7B). In the spleen, the red pulp displayed the strongest Ki67 staining regardless of the presence or absence of Cdk4 and Cdk2 revealing that active erythropoiesis was not affected. Moreover, in the white pulp most of the lymphocytes appeared quiescent with the exception of several germinal centers. Other secondary lymphoid follicles present in the intestinal wall (Peyer's patches) and in lymph nodes displayed normal proliferation rates (data not shown), suggesting a functional B‐cell response in Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 Δ/Δ;RERT ert/ert animals. Moreover, in the thymus, one of the tissues with faster cell turnover and most sensitive to cell division defects, almost all cortical thymocytes were positive for Ki67 immunostaining, indicating that the continuous and sustained production of naive T cells was preserved in the absence of Cdk4 and Cdk2.

In depth analysis of the adult hematopoietic system of Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 Δ/Δ;RERT ert/ert mice revealed that Cdk4 and Cdk2 were dispensable for proliferation and differentiation of all lineages. As illustrated in Figure S1A, bone marrow of Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 Δ/Δ;RERT ert/ert mice had the same number of burst‐forming erythroid units, and colony‐forming units for granulocyte, macrophage, and mixed granulocyte/macrophage lineages as wild type controls. To rule out the possibility that these colonies arose from stem cells that retained Cdk2 lox alleles, we performed semi‐quantitative PCR analysis on genomic DNA extracted from individual colonies. In all cases, we found complete excision of the floxed Cdk2 sequences (data not shown). Next, we examined the contributions of these hematopoietic precursors to the various cell lineages by staining bone marrow cells with lineage‐specific antibodies. Flow cytometry analysis indicated that the percentage of B‐cells (B220 antibodies), NK‐cells (DX5α antibodies), T‐cells (CD3 antibodies) and granulocyte/monocytes (GR1 and CD11b antibodies) were basically the same as in the bone marrow of Cdk4 +/+;Cdk2 +/+;RERT ert/ert mice (Figure S1B).

The percentage of lymphoid B‐cells (B220 antibodies), T‐cells (CD3 antibodies) and NK‐cells (DX5α antibodies) were also similar to those obtained in control spleen (Figure S1C). Likewise loss of Cdk4 and Cdk2 did not alter cell proliferation in the thymus. Moreover, ablation of these genes did not appear to have a negative effect on the maturation program of T lymphocytes since the percentages of double negative, double positive and single positive populations were the same as in wild type mice (Figure S1D). These results conclusively demonstrate that adult hematopoiesis is not dependent on the kinase activity of both Cdk4 and Cdk2.

2.6. Normal liver regeneration in the absence of Cdk4 and Cdk2

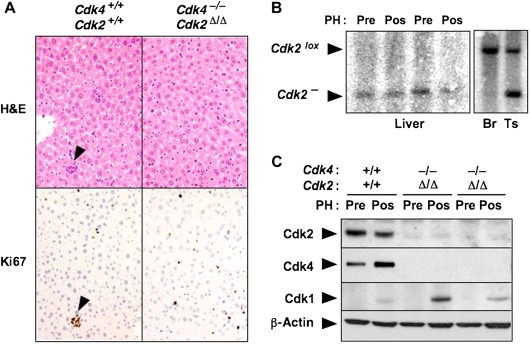

Liver regeneration following PH is considered one of the most stringent assays to assess the proliferative capacity of adult tissues. In this assay, adult hepatocytes regain proliferative properties to restore hepatic function as a response to the reduction in liver mass. Thus, we decided to test the proliferative properties of Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 Δ/Δ;RERT ert/ert mice by resecting two‐thirds of their livers and measuring hepatic regeneration 9 days later. Liver mass in the mixed 129/SvJ×C57BL/6J background in which the Cdk4 and Cdk2 strains are maintained is around 2.5% of the total body weight. Regenerated livers of 4‐OHT‐treated Cdk4 +/+;Cdk2 +/+;RERT ert/ert and Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 Δ/Δ;RERT ert/ert mice (n=3) displayed similar overall appearance and size (2.70±0.14% in the control mice and 2.55±0.21% in Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 Δ/Δ;RERT ert/ert animals). Histological characterization of sections from the regenerated livers showed normal morphology regardless of whether tissue regeneration occurred in the presence or absence of Cdk4 and Cdk2 (Figure 8A). Moreover, the levels of cell proliferation, determined by Ki67 immunostaining, were similar in the regenerated livers of control and Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 Δ/Δ;RERT ert/ert mice (Figure 8A).

Figure 8.

Liver regeneration in Cdk4−/−;Cdk2Δ/Δ;RERTert/ert mice. (A) 4OHT‐treated Cdk4+/+;Cdk2+/+;RERTert/ert and Cdk4−/−;Cdk2Δ/Δ;RERTert/ert mice were submitted to partial hepatectomy (PH) as indicated in Section 4 and the regenerated livers analyzed 9 days later by H&E and Ki67 immunostaining. A small hematopoietic cluster is indicated by arrowheads. (B) Southern blot analysis of the excision of conditional Cdk2lox alleles in resected (Pre) and regenerated (Pos) liver samples from two independent Cdk4−/−; Cdk2Δ/Δ;RERTert/ert mice. DNAs from brain (Br) and testis (Ts) tissue from one of these mice were also tested as controls. These tissues are known to undergo limited cleavage of the Cdk2lox allele (see Figure 5). (C) Immunoblot analysis of the expression of Cdk4, Cdk2 and Cdk1 in resected (Pre) and regenerated (Pos) livers of 4OHT‐treated Cdk4+/+;Cdk2+/+;RERTert/ert and Cdk4−/−; Cdk2Δ/Δ;RERTert/ert mice. β‐Actin served as loading control. The presence of the ert alleles in the description of the genotypes has been omitted for clarity.

To eliminate the possibility that liver regeneration in mutant mice may originate from a small subpopulation of stem cells that retained the conditional Cdk2 lox allele, we isolated DNA from regenerated livers of control and mutant mice and submitted them to Southern blot analysis. As shown in Figure 8B, DNA isolated from two independent mice only displayed the DNA band corresponding to the null Cdk2 − allele, thus indicating that hepatic regeneration occurred from Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− hepatocytes. Finally, western blot analysis of liver protein extracts obtained from the regenerated livers also showed absence of Cdk2 expression (Figure 8C). Interestingly, regenerated livers of mutant Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 Δ/Δ;RERT ert/ert mice expressed Cdk1 levels similar or possibly higher than those of control mice. These observations indicate that induction of Cdk1 expression in response to mitogenic signaling in proliferating tissues is independent of the presence of the two G1/S kinases, Cdk4 and Cdk2. These findings, taken together, provide convincing evidence that adult mammalian cells proliferate normally in the absence of Cdk4 and Cdk2.

3. Discussion

During evolution, eukaryotes have increased the number of Cdks according to their structural and functional complexity. Whereas yeasts have a single cell cycle Cdk, Cdc2/Cdc28, the mammalian genome has accumulated at least five loci encoding cell cycle Cdks (reviewed in Malumbres and Barbacid (2005)). They include Cdk1, most likely the functional orthologue of yeast Cdc2/Cdc28, Cdk2, Cdk3, Cdk4 and Cdk6. Widely accepted models propose that the increased Cdk complexity of higher eukaryotes is due to their need to have a more precise control of the various phases of the cell cycle. According to this model, Cdk3, Cdk4 and Cdk6 would be responsible for getting cells out of quiescence and driving them through G1, whereas Cdk2 and Cdk1 would be essential for the two most fundamental aspects of cell division, DNA synthesis and mitosis, respectively.

Recent genetic evidence, however, has challenged this model. We and others have targeted the genes encoding Cdk2, Cdk4 and Cdk6, to show that they are dispensable for cell proliferation, as well as for embryonic development and adult homeostasis (Berthet et al., 2003; Malumbres et al., 2004; Ortega et al., 2003; Rane et al., 1999; Tsutsui et al., 1999; Ye et al., 2001). Exceptions include the essential role of Cdk2 for meiotic cell division (Ortega et al., 2003), a fact often ignored when studying this kinase, and of Cdk4 for postnatal proliferation of specialized endocrine cells types such as insulin producing pancreatic beta cells and pituitary lactotrophs responsible for production of prolactin (Martin et al., 2003; Moons et al., 2002; Rane et al., 1999; Tsutsui et al., 1999).

It has been argued that the lack of requirement of individual Cdks for mammalian cell division is due to functional compensation by other Cdks. Indeed, concomitant ablation of the genes encoding Cdk4 and Cdk6 in the mouse germ line results in embryonic lethality, a more dramatic phenotype than that induced by ablating each locus independently (Malumbres et al., 2004). Cdk4 and Cdk6 are highly related kinases activated by the same D‐type Cyclins (Malumbres and Barbacid, 2005). Cdk4 −/−;Cdk6 −/− embryos die during late gestation due to limited proliferation of hematopoietic precursors, particularly those responsible for populating the erythroid lineage (Malumbres et al., 2004). Yet, Cdk4 −/−;Cdk6 −/− embryos display normal rates of cell proliferation in other tissues. Moreover, MEFs derived from these mutant embryos grow well in culture and enter the cell cycle upon mitogenic stimuli with normal kinetics (Malumbres et al., 2004). Similar results have been obtained in mice lacking the three D‐type Cyclins (Kozar et al., 2004). Thus, Cdk4 and Cdk6 play compensatory roles but only in highly specialized cell types.

In contrast, a recent report by Berthet et al. (2006) indicates that Cdk4 and Cdk2, the main G1/S kinases, have significant overlapping roles. In this study, Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− embryos die during midgestation due to heart defects not too different from those described here for newborn Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− mice. However, according to this report, combined absence of Cdk4 and Cdk2 results in limited phosphorylation, and hence deficient inactivation of pRb. This defect leads to limited expression of E2F targets essential for cell cycle progression such as Cyclin A and Cdk1. Indeed, in this study, Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− MEFs proliferate poorly and do not become immortal upon continuous passage in culture. Interestingly, the proliferative defects observed in these double mutant mice only occurred after midgestation, since E12.5 Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− embryos appeared to be normal (Berthet et al., 2006). The authors speculated that during early embryogenesis, either Cdk6 complexed to D‐type Cyclins or Cdk1 can inactivate pRb. A decrease in Cyclin D1 during midgestation would result in impaired pRb phosphorylation with subsequent inhibition of E2F‐dependent Cdk1 expression, leading to an overall decrease in cell proliferation that becomes incompatible with life (Berthet et al., 2006).

Our results are at variance with these findings. Whereas we observed embryonic lethality of Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− embryos, a significant percentage of them develop to term. Newborn Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− mice die shortly thereafter presumably due to cardiac insufficiency, a consequence of their limited number of cardiomyocytes. Yet, all other tissues, including those of hematopoietic origin, display normal proliferative levels. These observations indicate that Cdk2 does not play significant compensatory roles with Cdk4 in hematopoietic cells or any other cell type except for embryonic cardiomyocytes. Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− embryos are slightly smaller than those lacking Cdk4 alone (Rane et al., 1999; Tsutsui et al., 1999). However, the mixed background used in these studies prevents us to ascribe this small difference to loss of Cdk2.

Loss of viability during embryonic or early postnatal development often masks the overall phenotypic consequences of gene targeting. Generation of mice carrying a conditional mutation in the Cdk2 locus in a Cdk4 null background has allowed us to overcome this limitation by ablating Cdk2 in adult tissues. The absence of any overt phenotype in Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 Δ/Δ;RERT ert/ert mice, other than those observed in single Cdk4 and Cdk2 null animals, is not compatible with the central role proposed for these kinases during interphase. It could be argued that Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 Δ/Δ;RERT ert/ert mice do not display obvious abnormalities due to the low proliferation rates of most adult tissues. However, as illustrated here, a battery of highly proliferating adult tissues such as skin or small intestine as well as hematopoietic organs, display normal proliferation rates. Even hematopoietic precursors proliferate normally and retain the capacity to generate a normal mature hematopoietic system in the absence of Cdk4 and Cdk2. Moreover, adult hepatocytes deficient for these kinases can respond to severe stress conditions such as liver regeneration upon PH.

At the present time we can only speculate about the reasons for the different results obtained by us and Berthet et al. (2006). Both mice have similar genetic backgrounds, composed mainly of those of 129J and C57Bl6 origin, albeit our animals contain a limited contribution from CD1 mice. Whether this difference accounts for survival beyond mid‐gestation remains to be determined. It is also possible that the mice described by Berthet et al. have accumulated additional mutations either by chance or during selection of mice that underwent the rare recombination required to co‐segregate the neighboring Cdk4 and Cdk2 targeted loci. In any case, our results illustrate that mice can thrive without Cdk4 and Cdk2, specially during adult homeostasis.

Our in vitro studies with MEFs provide additional evidence that Cdk4 and Cdk2 are dispensable for the mammalian cell cycle. Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− MEFs become immortal with high (>80%) frequency when maintained in culture. These immortal MEFs have normal proliferation rates including S phase kinetics. Indeed, the only substantial difference between wild type and Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− MEFs resides in their increased susceptibility to the stress imposed by their adaptation to in vitro culture conditions. Under these stress conditions, MEFs lacking Cdk4 and Cdk2 proliferate significantly more slowly than MEFs expressing both enzymes. Yet, once Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 −/− MEFs become adapted to culture, they behave as wild type cells. Additional proof of the selective requirement for Cdk4 or Cdk2 during adaptation to culture conditions was provided by the efficient proliferation of immortal Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 lox/lox MEFs upon acute removal of Cdk2. Although the molecular mechanisms by which Cdk4 and Cdk2 facilitate cell division under in vitro stress conditions remain to be worked out, our results clearly illustrate that Cdk4 and Cdk2 are dispensable for mammalian cell division.

In summary, our results provide genetic evidence that Cdk4 and Cdk2 are dispensable for mammalian cell division, both during embryonic development and in adult homeostasis. These results are reminiscent of those previously reported for mice lacking Cdk6 and Cdk2 (Malumbres et al., 2004). Only loss of Cdk4 and Cdk6 expression is incompatible with life, at least during embryogenesis. Yet, most cell types proliferate well in the absence of these kinases, indicating that they play a developmental role in hematopoietic lineages, but are not essential for the basic process of mammalian cell division (Malumbres et al., 2004). Next, it will be necessary to determine to what extent interphase Cdks are essential for mammalian cell division by generating triple mutant mice deficient for Cdk4, Cdk6 and Cdk2. Targeting the Cdk3 locus will not be necessary since the strains used for these studies already carry a germ line mutation for Cdk3 (Ye et al., 2001). In addition, it will essential to determine whether Cdk1, the proposed orthologue for the yeast Cdc2/Cdc28 kinase, is also indispensable for mammalian cell division or can be compensated by other Cdks, by targeting this locus. This information will help us to better understand the role of Cdks in driving mammalian cell proliferation.

4. Experimental procedures

4.1. Gene targeting and mouse strains

The Cdk4 targeting vector was prepared as described in Figure 1. Briefly, a 6.4kbp EcoRI–BamHI genomic fragment containing the Cdk4 locus was isolated from a 129Sv/J genomic library and subcloned in pBluescript (Rane et al., 1999). An frt site was inserted 230bp upstream of exon 2. In addition, an frt‐PGK‐HygR‐frt hygromycin resistance cassette was inserted 115bp downstream of exon 4. A PGK‐thymidine kinase (TK) cassette was incorporated into the targeting vector for negative selection as previously described (Rane et al., 1999). The targeting vector was electroporated into ES cells carrying a Cdk2 conditional knock out allele (Ortega et al., 2003). Southern blot analysis of 120 HygR/GanR clones identified four recombinants (Figure 1B,C) that were aggregated to CD1 morulas. Male chimeras derived from two clones (ESDS1.15 and ESDS1.66) co‐segregated the targeted Cdk4 (Cdk4 3frt) and Cdk2 (Cdk2 lox) alleles to their offspring. The resulting Cdk4 +/3frt;Cdk2 +/lox mice were crossed to pCAG‐Flpe transgenics (Rodriguez et al., 2000) to excise the PGK‐HygR cassette and the exons 2‐4 (Figure 1A). The resulting Cdk4 +/−;Cdk2 +/lox mice were crossed to CMV‐Cre transgenics (Schwenk et al., 1995) to generate double heterozygous Cdk4 +/−;Cdk2 +/− animals. These heterozygous mice were crossed with wild type C57Bl6 animals to segregate the Flpe and Cre transgenes. Cdk4 +/−;Cdk2 +/lox mice were also mated with RERTert/ert mice (Guerra et al., 2003) to generate the Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 lox/lox;RERTert/ert animals used to ablate Cdk2 postnatally. These mice were also crossed with wild type C57Bl6 animals to segregate the Flpe transgene. Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 lox/lox;RERTert/ert mice were treated at weaning (P25) with 4‐OHT for 2–4 months (1mg, twice a week) to ensure efficient ablation of the conditional Cdk2 lox allele. These treated mice were designated as Cdk4 −/−;Cdk2 Δ/Δ;RERT ert/ert. Routine genotyping of Cdk4 −, Cdk2 − and Cdk2 lox alleles was carried out by PCR amplification using specific oligonucleotides (primer sequences are available from the authors upon request). Mice were maintained according to the animal care standards established by national and international institutions including the European Union.

4.2. Histopathology and immunohistochemistry

Embryos or organs dissected from mice were fixed in 10%‐buffered formalin (Sigma) and embedded in paraffin. Three‐ or five‐micrometer‐thick sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). For proliferation studies, tissues or embryos were stained with Ki67 specific antibodies (MIB‐1; Dako). Detection of apoptotic cells on tissue sections was carried out using the TUNEL assay (Apoptag Peroxidase, Intergen) or anti‐active Caspase 3 antibodies (R&D Systems).

4.3. Cell culture assays

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were isolated from E13.5 embryos and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 2mM glutamine, 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). MEFs were propagated in culture according to standard 3T3 protocols. For proliferation assays, 5×104 cells were plated on 6‐well plates in duplicate essentially as previously described (Martín et al., 2005). To analyse S phase entry, MEFs (106 cells/10cm dish) were deprived of serum for 72h in DMEM+0.1% FBS and re‐stimulated with 10% FBS to enter the cell cycle. Cells were continuously labeled with 50μM bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU; Sigma), harvested at the indicated times and stained with anti‐BrdU antibodies (Becton Dickinson) and propidium iodide. DNA content was analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSScalibur from Becton‐Dickinson). MEFs were infected with retroviral vectors expressing the Cre recombinase as previously described (Martín et al., 2005).

To study proliferation of hematopoietic precursors, livers were collected from E17.5 embryos, single cell suspensions prepared and 5×104 cells plated in methylcellulose (Stem Cell Technologies #03434) as suggested by the manufacturer. For each sample, two duplicate dishes were analyzed 9 days after plating.

4.4. FACS analysis

Livers were collected from E17.5 embryos and single cell suspensions were prepared. 2×106 cells/liver were immunostained and hematopoietic progenitors were identified as previously described (Malumbres et al., 2004). HSCs were gated as Lin− IL7Rα− c‐Kit+ Sca1+; CMPs as Lin− IL7Rα− c‐Kit+ Sca1− FcγRlow CD34+; GMPs as Lin− IL7Rα− c‐Kit+ Sca1− FcγRhi CD34+; and MEPs as Lin− IL7Rα− c‐Kit+ Sca1− FcγRlow CD34−. Cell surface markers used to identify the specific hematopoietic populations in adult bone marrow, thymus or spleen include CD3, CD4, CD8, CD11B, CD16/32, CD19, CD45, B220, DX5α, GR1 and Ter119 (all from Pharmingen). Their relative numbers were quantified using FACSScalibur and FACSAria (Becton Dickinson) cytometers.

4.5. Liver regeneration

Animals were anesthetized using inhalation of 2% isoflourane after which resection of two‐thirds of total liver mass (left lateral, left median and right median lobectomy) was performed. All animals were treated with 0.05mg/kg of buprenorphine following PH. The mass of the resected liver tissue was measured right after surgery, and that of the regenerated liver was determined after sacrificing the animals 9 days after the PH.

4.6. Protein analysis

Protein lysates were isolated and used for protein analysis by immunoblotting as previously described (Martín et al., 2005). Antibodies against the following proteins were used: Cdk2 (M2; Santa Cruz), Cdk1 (17; Santa Cruz), Cdk4 (C22; Santa Cruz), Cyclin A (H432; Santa Cruz), Cyclin E (M20; Santa Cruz), Cyclin D1 (DCS6; Neo Markers), Cyclin D2 (Santa Cruz), p21Cip1 (C19; Santa Cruz), p27Kip1 (Transduction Laboratories), β‐Actin (AC15, Sigma) and pRb (BD Pharmingen). pRb phosphospecific antibodies to S608 (#2181), S780 (#9307) and S807/811 (#9308) were from Cell Signalling. As secondary antibodies, peroxidase‐conjugated IgG (Dako) were used, followed by chemiluminescence detection (ECL; Amhersam).

Supporting information

Appendix Supplementary material

Supplemental Figure S1 Characterization of hematopoietic compartments in adult mice lacking Cdk4 and Cdk2. (A) Colony formation assay of bone marrow cells in methylcellulose. Bars represent number of colony‐forming units for granulocytes (CFU‐G), macrophages (CFU‐M), mixed granulocytes/macrophages (CFU‐GMM) and erythrocytes (BFU‐E), obtained from seeding 5×104 cells. (B–D) Flow cytometry analysis of the major hematopoietic populations in adult organs. Single cell suspensions were immunostained with antibodies against the indicated surface markers and the relative percentages of specific populations were quantified by cytometry. Open boxes represent samples obtained from 4OHT‐treated Cdk4+/+;Cdk2+/+;RERTert/ert control mice. Solid boxes represent samples obtained from treated Cdk4−/−;Cdk2Δ/Δ;RERTert/ert mice. Error bars: SD.

Acknowledgements

We thank Rut González, Marta San Román, Blanca Velasco, and Raquel Villar for excellent technical assistance and Arancha García for invaluable help with the cytometer. We also value the excellent support provided by the Transgenic and Comparative Pathology Units of the CNIO. This work was supported by grants from the Plan Nacional de Investigación Científica to D.S. (GEN2003‐20243‐C08‐02), M.M. (BMC2003‐06098) and M.B. (SAF2000‐0009‐CO2‐01, SAF2002‐10374‐E, SAF1999‐1825‐CE and SAF2004‐20477‐E), Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria to D.S. (PI031527), V Framework Programme of the European Union to M.B. (QLK3‐1999‐00875, QLG2‐CT‐2002‐00930, LSHC‐CT‐2004‐503438), INSERM and Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer (Région Aquitaine) to P.D. C.B. and A.C. were supported by fellowships from la Ligue contre le Cancer (Comité de la Dordogne) and FPI (Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia), respectively. The CNIO was partially supported by the RTICCC (Red de Centros de Cáncer; FIS C03/10).

Appendix A. Supplementary material 1.

1.1.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.molonc.2007.03.001.

Barrière Cédric, Santamaría David, Cerqueira Antonio, Galán Javier, Martín Alberto, Ortega Sagrario, Malumbres Marcos, Dubus Pierre, Barbacid Mariano, (2007), Mice thrive without Cdk4 and Cdk2, Molecular Oncology, 1, doi:10.1016/j.molonc.2007.03.001.

References

- Adams, P.D. , 2001. Regulation of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein by cyclin/cdks. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1471, 123–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleem, E. , Kiyokawa, H. , Kaldis, P. , 2005. Cdc2–Cyclin E complexes regulate the G1/S phase transition. Nat. Cell. Biol.. 7, 831–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthet, C. , Aleem, E. , Coppola, V. , Tessarollo, L. , Kaldis, P. , 2003. Cdk2 knockout mice are viable. Curr. Biol.. 13, 1775–1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthet, C. , Klarmann, K.D. , Hilton, M.B. , Suh, H.C. , Keller, J.R. , Kiyokawa, H. , Kaldis, P. , 2006. Combined loss of Cdk2 and Cdk4 results in embryonic lethality and Rb hypophosphorylation. Dev. Cell. 10, 563–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson, N. , 1998. The regulation of E2F by pRB-family proteins. Genes Dev.. 12, 2245–2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil, R. , Brocard, J. , Mascrez, B. , LeMeur, M. , Metzger, D. , Chambon, P. , 1996. Ligand-activated site-specific recombination in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 93, 10887–10890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra, C. , Mijimolle, N. , Dhawahir, A. , Dubus, P. , Barradas, M. , Serrano, M. , Campuzano, V. , Barbacid, M. , 2003. Tumor induction by an endogenous K-ras oncogene is highly dependent on cellular context. Cancer Cell. 4, 111–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozar, K. , Ciemerych, M.A. , Rebel, V.I. , Shigematsu, H. , Zagozdzon, A. , Sicinska, E. , Geng, Y. , Yu, Q. , Bhattacharya, S. , Bronson, R.T. , 2004. Mouse development and cell proliferation in the absence of D-Cyclins. Cell. 118, 477–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malumbres, M. , Barbacid, M. , 2005. Mammalian cyclin-dependent kinases. Trends Biochem. Sci.. 30, 630–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malumbres, M. , Sotillo, R. , Santamaría, D. , Galán, J. , Cerezo, A. , Ortega, S. , Dubus, P. , Barbacid, M. , 2004. Mammalian cells cycle without the D-type Cyclin-dependent kinases Cdk4 and Cdk6. Cell. 118, 493–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J. , Hunt, S.L. , Dubus, P. , Sotillo, R. , Nehme-Pelluard, F. , Magnuson, M.A. , Parlow, A.F. , Malumbres, M. , Ortega, S. , Barbacid, M. , 2003. Genetic rescue of Cdk4 null mice restores pancreatic β-cell proliferation but not homeostatic cell number. Oncogene. 22, 5261–5269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín, A. , Odajima, J. , Hunt, S.L. , Dubus, P. , Ortega, S. , Malumbres, M. , Barbacid, M. , 2005. Cell cycle inhibition and tumor suppression by p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 are independent of Cdk2. Cancer Cell. 7, 591–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moons, D.S. , Jirawatnotai, S. , Parlow, A.F. , Gibori, G. , Kineman, R.D. , Kiyokawa, H. , 2002. Pituitary hypoplasia and lactotroph dysfunction in mice deficient for Cyclin-dependent kinase-4. Endocrinology. 143, 3001–3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, S. , Prieto, I. , Odajima, J. , Martin, A. , Dubus, P. , Sotillo, R. , Barbero, J.L. , Malumbres, M. , Barbacid, M. , 2003. Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 is essential for meiosis but not for mitotic cell division in mice. Nat. Genet.. 35, 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rane, S.G. , Dubus, P. , Mettus, R.V. , Galbreath, E.J. , Boden, G. , Reddy, E.P. , Barbacid, M. , 1999. Loss of Cdk4 expression causes insulin-deficient diabetes and Cdk4 activation results in ß-cell hyperplasia. Nat. Genet.. 22, 44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, C.I. , Buchholz, F. , Galloway, J. , Sequerra, R. , Kasper, J. , Ayala, R. , Stewart, A.F. , Dymecki, S.M. , 2000. High-efficiency deleter mice show that FLPe is an alternative to Cre-loxP. Nat. Genet.. 25, 139–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwenk, F. , Baron, U. , Rajewsky, K. , 1995. A cre-transgenic mouse strain for the ubiquitous deletion of loxP-flanked gene segments including deletion in germ cells. Nucleic Acids Res.. 23, 5080–5081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr, C.J. , Roberts, J.M. , 1999. CDK inhibitors: positive and negative regulators of G1-phase progression. Genes Dev.. 13, 1501–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimarchi, J.M. , Lees, J.A. , 2002. Sibling rivalry in the E2F family. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol.. 3, 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui, T. , Hesabi, B. , Moons, D.S. , Pandolfi, P.P. , Hansel, K.S. , Koff, A. , Kiyokawa, H. , 1999. Targeted disruption of Cdk4 delays cell cycle entry with enhanced p27Kip1 activity. Mol. Cell. Biol.. 19, 7011–7019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye, X. , Zhu, C. , Harper, J.W. , 2001. A premature-termination mutation in the Mus musculus cyclin-dependent kinase 3 gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98, 1682–1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix Supplementary material

Supplemental Figure S1 Characterization of hematopoietic compartments in adult mice lacking Cdk4 and Cdk2. (A) Colony formation assay of bone marrow cells in methylcellulose. Bars represent number of colony‐forming units for granulocytes (CFU‐G), macrophages (CFU‐M), mixed granulocytes/macrophages (CFU‐GMM) and erythrocytes (BFU‐E), obtained from seeding 5×104 cells. (B–D) Flow cytometry analysis of the major hematopoietic populations in adult organs. Single cell suspensions were immunostained with antibodies against the indicated surface markers and the relative percentages of specific populations were quantified by cytometry. Open boxes represent samples obtained from 4OHT‐treated Cdk4+/+;Cdk2+/+;RERTert/ert control mice. Solid boxes represent samples obtained from treated Cdk4−/−;Cdk2Δ/Δ;RERTert/ert mice. Error bars: SD.