Daurichromenic acid, an anti-HIV meroterpenoid, is biosynthesized by a novel flavoprotein oxidase localized in the specialized epidermal organ, the glandular scales of Rhododendron dauricum.

Abstract

Daurichromenic acid (DCA) synthase catalyzes the oxidative cyclization of grifolic acid to produce DCA, an anti-HIV meroterpenoid isolated from Rhododendron dauricum. We identified a novel cDNA encoding DCA synthase by transcriptome-based screening from young leaves of R. dauricum. The gene coded for a 533-amino acid polypeptide with moderate homologies to flavin adenine dinucleotide oxidases from other plants. The primary structure contained an amino-terminal signal peptide and conserved amino acid residues to form bicovalent linkage to the flavin adenine dinucleotide isoalloxazine ring at histidine-112 and cysteine-175. In addition, the recombinant DCA synthase, purified from the culture supernatant of transgenic Pichia pastoris, exhibited structural and functional properties as a flavoprotein. The reaction mechanism of DCA synthase characterized herein partly shares a similarity with those of cannabinoid synthases from Cannabis sativa, whereas DCA synthase catalyzes a novel cyclization reaction of the farnesyl moiety of a meroterpenoid natural product of plant origin. Moreover, in this study, we present evidence that DCA is biosynthesized and accumulated specifically in the glandular scales, on the surface of R. dauricum plants, based on various analytical studies at the chemical, biochemical, and molecular levels. The extracellular localization of DCA also was confirmed by a confocal microscopic analysis of its autofluorescence. These data highlight the unique feature of DCA: the final step of biosynthesis is completed in apoplastic space, and it is highly accumulated outside the scale cells.

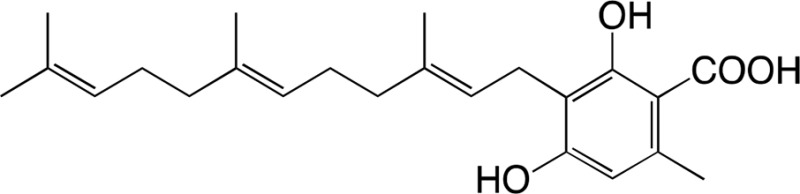

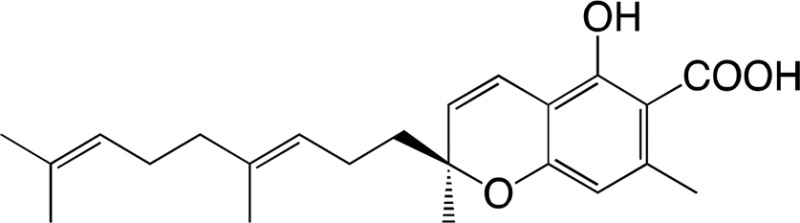

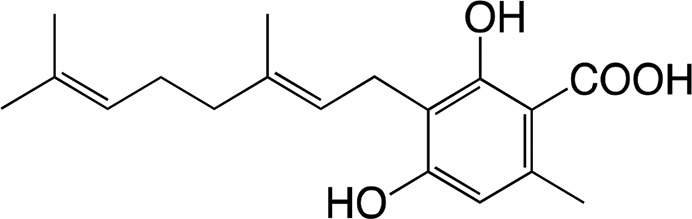

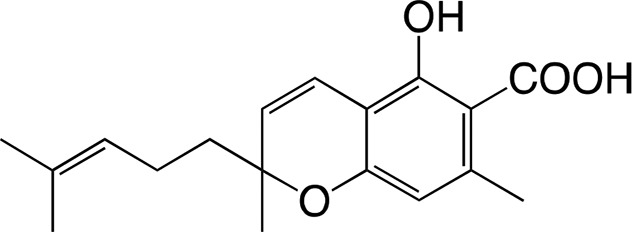

Rhododendron dauricum (Ericaceae), distributed in northeastern Asia, produces unique secondary metabolites, including daurichromenic acid (DCA; Fig. 1A), a novel meroterpenoid composed of orsellinic acid and sesquiterpene moieties (Kashiwada et al., 2001). DCA has attracted considerable attention as a medicinal resource because this compound shows various pharmacological activities (Iwata et al., 2004; Hashimoto et al., 2005). Especially, DCA has been one of the most effective natural products with anti-HIV properties, as shown in experiments with acutely infected H9 cells, in which the EC50 value of DCA (15 nm) was smaller than that of the positive control drug azidothymidine (44 nm; Lee, 2010). Thus, chemical synthesis of DCA has been studied extensively over the past few years (Liu and Woggon, 2010; Bukhari et al., 2015).

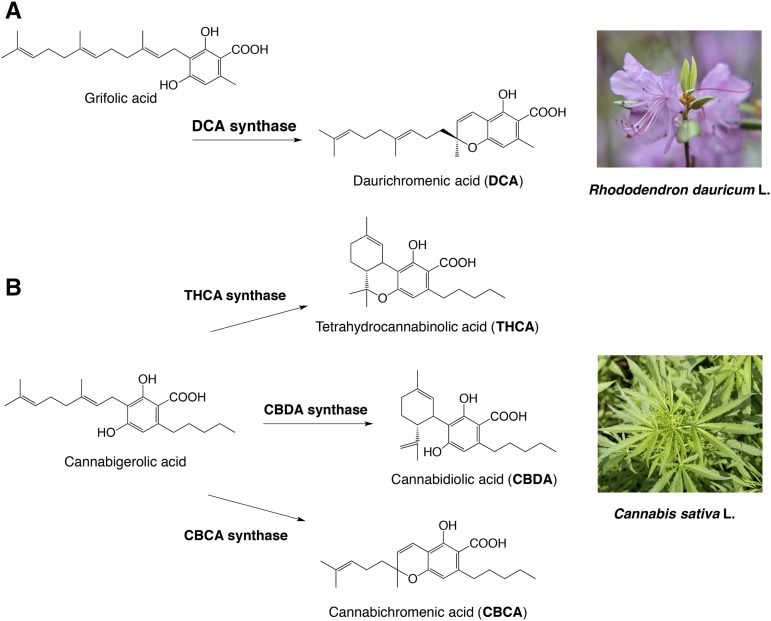

Figure 1.

Biosynthesis of plant meroterpenoids via oxidative cyclization of isoprenoid moieties. A, DCA biosynthesis in R. dauricum catalyzed by DCA synthase. B, Cannabinoid biosynthesis in C. sativa catalyzed by THCA synthase, CBDA synthase, and CBCA synthase.

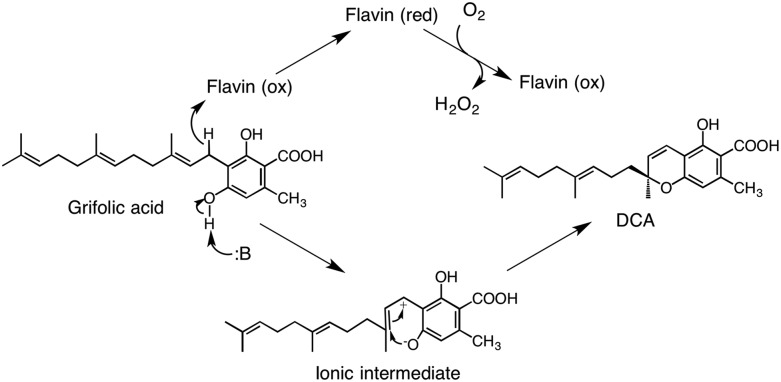

With respect to the biosynthesis of DCA, we previously reported partial characterization of an oxidocyclase, named DCA synthase, using a crude protein extract from young leaves of R. dauricum (Taura et al., 2014). DCA synthase is an enzyme that catalyzes the stereoselective oxidative cyclization of the farnesyl moiety of grifolic acid to form DCA (Fig. 1A). Unlike P450-type cyclases involved in glyceollin and furanocoumarin biosynthesis (Welle and Grisebach, 1988; Larbat et al., 2007), DCA synthase is a soluble protein and does not need exogenously added cofactors for the reaction. Remarkably, these features are similar to those reported for cannabinoid synthases from Cannabis sativa (Fig. 1B). Hitherto, three cannabinoid synthases, tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA) synthase, cannabidiolic acid (CBDA) synthase, and cannabichromenic acid (CBCA) synthase, have been identified and characterized (Taura et al., 1995, 1996; Morimoto et al., 1997). All cannabinoid synthases catalyze the oxidocyclization of the geranyl group of a common substrate, cannabigerolic acid, to form novel ring systems. Previous structural and biochemical studies have demonstrated that THCA synthase and CBDA synthase are flavoprotein oxidases belonging to the vanillyl alcohol oxidase (VAO) flavoprotein family (Sirikantaramas et al., 2004; Taura et al., 2007). These cannabinoid synthases catalyze reactions using covalently linked FAD as the coenzyme and molecular oxygen as the final electron acceptor. CBCA synthase, which synthesizes a chromene ring similar to that in DCA biosynthesis, has not been characterized at the molecular level, whereas CBDA synthase shares similar biochemical properties with THCA synthase (Morimoto et al., 1997). In contrast to these cannabinoid synthases, DCA synthase has neither been cloned nor purified. Therefore, the structural and functional characteristics of this enzyme remain unclear.

VAO flavoprotein family members have divergent functions and are widely distributed among plants, animals, and microorganisms (Leferink et al., 2008). Apart from cannabinoid synthases, several VAO family enzymes, involved in a variety of plant specialized pathways, have been identified to date, such as berberine bridge enzyme (BBE), (S)-tetrahydroprotoberberine oxidase, and dihydrobenzophenanthridine oxidase in benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis (Kutchan and Dittrich, 1995; Gesell et al., 2011; Hagel et al., 2012); AtBBE-like13 and AtBBE-like15 (monolignol oxidases) in lignin biosynthesis (Daniel et al., 2015); and carbohydrate oxidases involved in the defense against microbial pathogens to supply hydrogen peroxide as a by-product (Custers et al., 2004). Recently, crystal structures of Eschscholzia californica BBE (EcBBE; Winkler et al., 2008), AtBBE-like15 (Daniel et al., 2015), and THCA synthase (Shoyama et al., 2012) have been determined, and the structural basis of the enzymatic reactions was characterized in detail. As a common feature, these plant enzymes were proven to bicovalently bind to FAD coenzyme via a novel 6-S-cysteinyl,8α-N1-histidyl linkage, which was first identified in a bacterial FAD oxidase, glucooligosaccharide oxidase from Acremonium strictum (Huang et al., 2005).

Among the identified members of the VAO family, THCA synthase and CBDA synthase, producing major cannabinoids, have long been the only examples to catalyze the oxidocyclization of the prenyl moiety in a meroterpenoid natural product (Baunach et al., 2015). Thus, DCA synthase, mediating a reaction similar to those of cannabinoid synthases, is an interesting enzyme in which to study the structural and functional properties. As the initial step to the detailed studies of DCA synthase, we attempted to isolate the cDNA of the gene encoding DCA synthase, based on a homology search against the translated R. dauricum young leaf transcriptome, using cannabinoid synthases as queries. Heterologous expression of the recombinant proteins in a Pichia pastoris system provided evidence that one of the candidate cDNAs is of a gene that encodes an active DCA synthase. In this study, we describe the molecular cloning and biochemical characterization of DCA synthase, a novel member of the meroterpenoid cyclase-type flavoprotein oxidases.

In our previous study, we confirmed that the meroterpenoid metabolites (DCA and grifolic acid) as well as DCA synthase activity are localized predominantly to young leaves of R. dauricum (Taura et al., 2014). This tissue distribution also is notable because young leaves of R. dauricum, a kind of lepidote Rhododendron species, are covered with numerous trichomes called glandular scales (Desch, 1983). Glandular scale is a multicellular epidermal organ that contains secondary metabolites such as sesquiterpenoids, including germacrone, and these metabolites are thought to participate in repelling insects hazardous to this plant (Doss, 1984; Doss et al., 1986). However, little information is available on the relationship between glandular scales and DCA biosynthesis. In this study, we provide detailed evidence that DCA is biosynthesized and accumulated primarily in the glandular scales of young leaves. We also discuss possible reasons why this specialized metabolite is produced in the specialized epidermal organ, the glandular scales of R. dauricum.

RESULTS

Molecular Cloning and Sequence Analysis of DCA Synthase Candidates

Three cDNA contigs encoding FAD oxidase (FADOX) were identified as candidate cDNAs for DCA synthase from a young leaf transcriptome database of R. dauricum, as described in “Materials and Methods,” and they were tentatively designated as RdFADOX1 to RdFADOX3. To isolate their full-length cDNA sequences, we performed 5ʹ- and 3ʹ-RACE to obtain the terminal regions of the respective genes. Then, the coding regions of RdFADOX1 to RdFADOX3 cDNAs were amplified using gene-specific primers, which were subcloned into the expression vector pPICZA, and the sequences were reconfirmed.

The RdFADOX1 to RdFADOX3 genes contained 1,602-, 1,590-, and 1,587-bp open reading frames encoding 533-, 529-, and 528-amino acid-long polypeptides, respectively. The deduced amino acid sequences exhibited ∼50% identities among each other and showed from 40% to 50% identities with functionally characterized plant FAD oxidases, including THCA synthase, EcBBE, and AtBBE-like15 (Supplemental Fig. S1A). The RdFADOX amino acid sequences contained an FAD-binding domain 4 (pfam01565; Gesell et al., 2011) in their N-terminal halves (Supplemental Fig. S1B). In addition, multiple sequence alignment confirmed that the His and Cys residues that form the bicovalent linkage with the FAD coenzyme in structurally characterized FAD oxidases also are conserved in RdFADOXs (Supplemental Fig. S1A).

The extracellular localization of RdFADOX1 to RdFADOX3 and the presence of N-terminal signal peptides with 24, 24, and 21 amino acids, respectively, were predicted using online software such as PSORT and TargetP (Supplemental Fig. S1B). Thus, the mature peptide sequences of RdFADOX1 to RdFADOX3 are presumed to be of 509, 505, and 507 amino acids with molecular masses of 57.2, 56.4, and 56.8 kD, respectively. In addition, several Asn glycosylation motifs were found in respective RdFADOX primary structures. Based on these sequence characteristics, RdFADOX1 to RdFADOX3 are predicted to be secreted FAD oxidases, similar to cannabinoid synthases (Sirikantaramas et al., 2004; Taura et al., 2007).

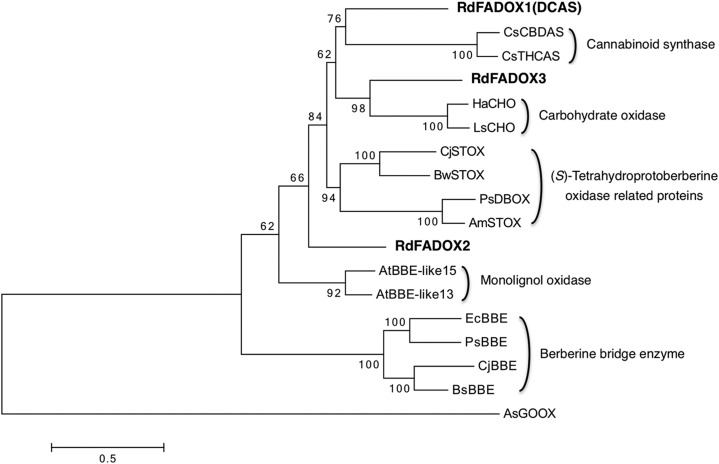

Among these candidate proteins, RdFADOX1 was relatively remarkable because, in the phylogenetic analysis based on the protein alignment with functionally characterized plant FAD oxidases, the RdFADOX1 sequence was the nearest neighbor to cannabinoid synthases to form a subclade, whereas RdFADOX3 was closest to carbohydrate oxidases and RdFADOX2 stood independently (Fig. 2). In addition, a relatively high transcript level of RdFADOX1 in the young leaf transcriptome was estimated by calculating FPKM (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped) values (Trapnell et al., 2010) for the respective RdFADOX open reading frames. The FPKM value for RdFADOX1 was 74.7, which was much higher than those calculated for RdFADOX2 and RdFADOX3 (11.2 and 29.6, respectively). Notably, the gene for orcinol synthase (Taura et al., 2016; GenBank accession no. LC133082), the polyketide synthase involved in orsellinic acid biosynthesis in the DCA pathway, also is a highly expressed gene with an FPKM value of 81.9.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree representing plant FAD oxidases. The bacterial enzyme Acremonium strictum glucooligosaccharide oxidase (AsGOOX) was used as an outgroup. Bootstrap values are presented at each node. The scale represents 0.5 amino acid substitutions per site. Abbreviations for species are as follows: Am, Argemone mexicana; At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Bs, Berberis stolonifera; Bw, Berberis wilsoniae; Cj, Coptis japonica; Cs, Cannabis sativa; Ec, Eschscholzia californica; Ha, Helianthus annuus; Ls, Lactuca sativa; Ps, Papaver somniferum; Rd, Rhododendron dauricum. Abbreviations for enzymes are as follows: BBE, berberine bridge enzyme; CBDAS, CBDA synthase; CHO, carbohydrate oxidase; DBOX, dihydrobenzophenanthridine oxidase; DCAS, DCA synthase; FADOX, FAD oxidase; STOX, (S)-tetrahydroprotoberberine oxidase; THCAS, THCA synthase. The NCBI protein registration numbers are as follows. BsBBE, AAD17487.1; CjBBE, BAM44344.1; EcBBE, AAC39358.1; PsBBE, AAC61839.1; CsCBDAS, BAF65033.1; HaCHO, AAL77103.1; LsCHO, AAL77102.1; PsDBOX, AGL44334.1; AsGOOX, AAS79317.1; AmSTOX, ADY15027.1; BwSTOX, ADY15026.1; CjSTOX, BAJ40864.1; CsTHCAS, BAC41356.1.

Heterologous Protein Expression in P. pastoris Culture

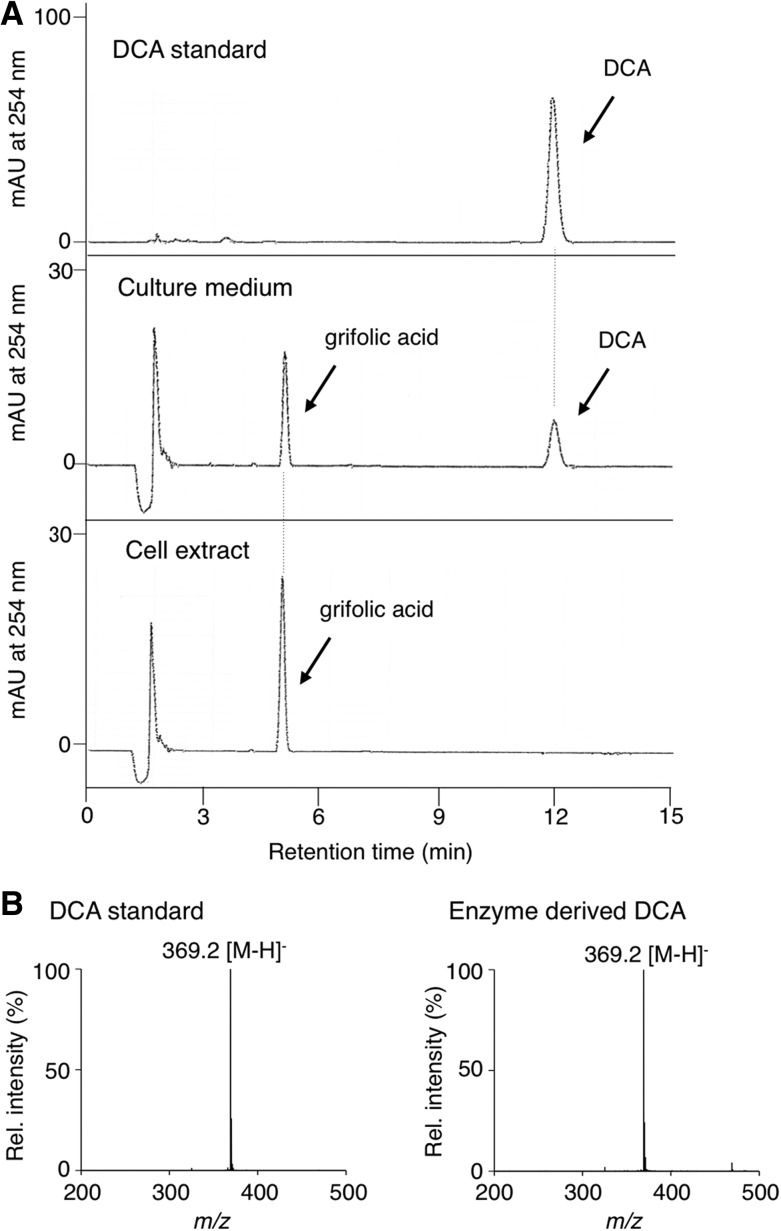

To examine which RdFADOX gene encodes DCA synthase, the pPICZA plasmids containing full-length cDNAs were introduced to P. pastoris KM71H by electroporation. The transgenic P. pastoris colonies were cultured individually in minimal liquid medium, and protein expression was induced by adding methanol. Enzyme assays using the cell extract and culture medium of the respective transgenic cultures clearly demonstrated that the RdFADOX1 gene encodes an active DCA synthase, because the culture supernatant exhibited a clear DCA-producing activity from grifolic acid (Fig. 3A; 30–40 pkat mg−1 protein). In contrast, the cell extract prepared from the same culture exhibited no enzyme activity (Fig. 3A), suggesting that the recombinant DCA synthase was effectively secreted from P. pastoris, likely because the N-terminal signal peptide also was functional in P. pastoris. The enzymatically synthesized DCA showed retention time and molecular mass identical to those of the authentic DCA sample on liquid chromatography (LC)-electrospray ionization (ESI)-mass spectrometry (MS) analysis (Fig. 3B). In addition, a chiral HPLC analysis revealed that the recombinant enzyme produced (+)-DCA as the predominant reaction product with an enantiomeric excess value of ∼92% (Supplemental Fig. S2). This stereoselectivity of the recombinant enzyme was similar to that of native DCA synthase (Taura et al., 2014). Based on these results, the RdFADOX1 gene cDNA was confirmed to be the one coding for DCA synthase. In contrast, neither the cell extract nor the culture medium prepared from the transgenic P. pastoris harboring the RdFADOX2 or RdFADOX3 gene showed DCA synthase activity, suggesting that these proteins might contribute to oxidative reactions other than DCA biosynthesis in R. dauricum plants.

Figure 3.

Product analyses of the reaction catalyzed by enzyme solution prepared from the transgenic P. pastoris expressing DCA synthase. A, HPLC elution profiles of DCA standard (top), the reaction mixture with culture medium (middle), and the reaction mixture with cellular extract (bottom). mAU, Milliabsorbance unit. B, ESI-MS (negative mode) of DCA standard (left) and DCA synthesized by culture medium as an enzyme (right).

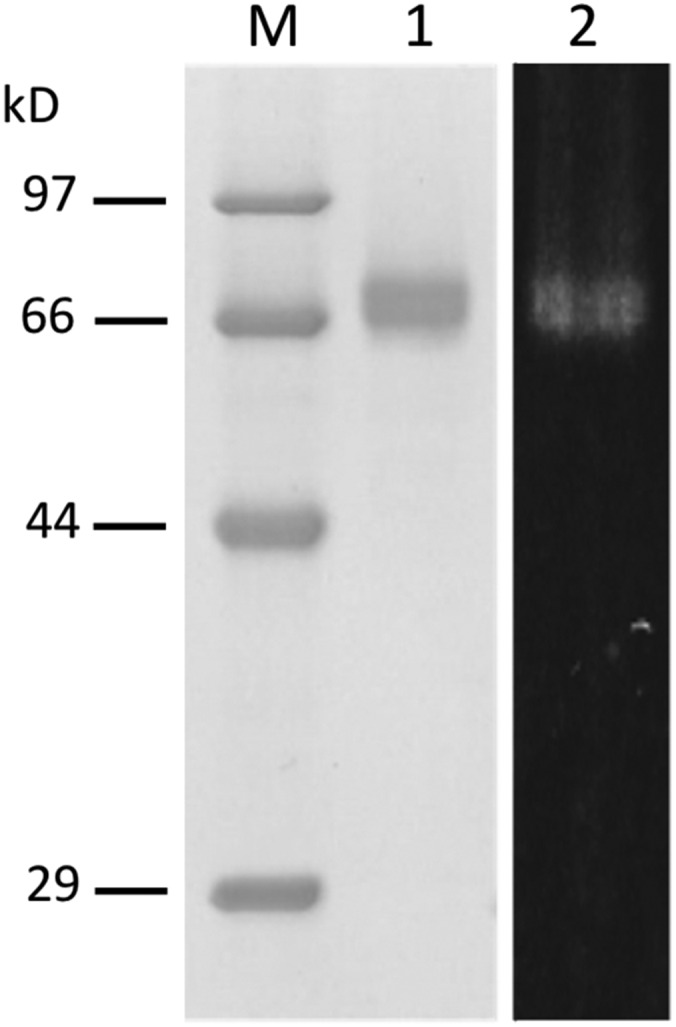

The recombinant DCA synthase in P. pastoris culture medium was immediately purified by column chromatography on hydroxylapatite, followed by TOYOPEARL CM650M. On SDS-PAGE, the purified enzyme was observed as a broad protein band with an average molecular mass of ∼74 kD (Fig. 4). The native molecular mass of the purified enzyme was estimated to be ∼68 kD, based on the elution volume on gel filtration chromatography, demonstrating that DCA synthase is a monomeric protein, as reported for cannabinoid synthases (Taura et al., 1995, 1996). The N-terminal amino acid sequence of the purified protein was Ala-His-Thr, which matched to the tripeptide at the 25th position of DCA synthase. Thus, the predicted 24-amino acid signal peptide was correctly cleaved during the protein synthesis in P. pastoris. Because the molecular mass of the purified enzyme was apparently larger than the theoretical value for the mature polypeptide (57.2 kD), carbohydrate attachment to the protein was suspected. As shown in Supplemental Figure S3, the purified enzyme was stained with periodic acid-Schiff sugar staining reagent, and in addition, endoglycosidase H treatment afforded an ∼58-kD convergent protein band that is insensitive to sugar staining, confirming that the recombinant DCA synthase was highly Asn glycosylated. This result was reasonable because the mature region of DCA synthase contains six Asn glycosylation motifs (Supplemental Fig. S1B).

Figure 4.

SDS-PAGE of the purified recombinant DCA synthase. Lane M, Molecular mass standards with indicated molecular masses; lane 1, purified DCA synthase (2 μg); lane 2, the same sample as in lane 1 visualized by transillumination at 310 nm.

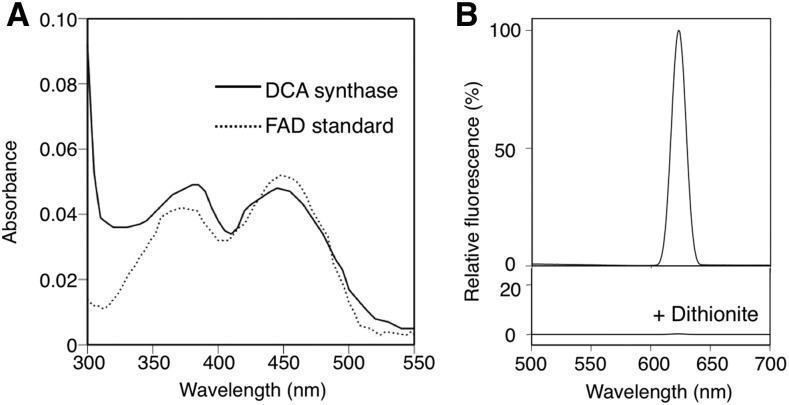

The concentrated solution of the recombinant DCA synthase was yellowish, and transillumination of the enzyme at 310 nm showed a clear in-gel autofluorescence as in the case of known flavoproteins (Kutchan and Dittrich, 1995; Sirikantaramas et al., 2004; Taura et al., 2007; Fig. 4). Because boiling of the enzyme in a denaturing buffer for SDS-PAGE failed to release the compound showing fluorescence, it was suggested that the fluorescent molecule might be covalently linked to the enzyme. The purified DCA synthase showed absorption maxima at 385 and 450 nm, which quite resembled that of authentic FAD (Fig. 5A). In addition, the fluorescence emission of DCA synthase exhibited a maximum at 624 nm, and supplementation with sodium dithionite, the flavin-reducing agent (Fox, 1974), resulted in a complete quenching of fluorescence (Fig. 5B). Taken together, these properties were consistent with those of flavoproteins, indicating that DCA synthase covalently binds to flavin coenzyme via conserved flavinylation residues (Supplemental Fig. S1). To obtain more structural information on the flavin molecule attached to DCA synthase, we attempted to hydrolyze the flavin by boiling the enzyme in 10 mm HCl for 10 min as described by Kutchan and Dittrich (1995). Consequently, AMP was clearly detected by HPLC and MS analyses in the acid-hydrolyzed sample (Supplemental Fig. S4), suggesting that the enzyme-bound FAD was hydrolyzed to release AMP as reported for EcBBE (Kutchan and Dittrich, 1995). Therefore, the flavin molecule in DCA synthase is most likely FAD.

Figure 5.

Spectral measurements of the purified recombinant DCA synthase. A, Absorption spectrum of the enzyme (0.23 mg mL−1) dissolved in 10 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7). B, Fluorescence emission spectrum of the same sample as in A. The sample was irradiated at 310 nm. The fluorescence emission at 624 nm was quenched by the addition of sodium dithionite.

Biochemical Properties of the DCA Synthase Reaction

Using the purified recombinant enzyme, the biochemical properties of the DCA-producing reaction were analyzed. First, as described previously for the native enzyme (Taura et al., 2014), the DCA synthase reaction did not need exogenously added redox coenzymes such as FAD (Supplemental Table S1). Divalent metal ions, which are often used as cofactors for class I and class II terpene cyclases (Baunach et al., 2015), also exhibited little effect on enzyme activity (Supplemental Table S1). In contrast, the reaction absolutely required molecular oxygen, because an oxygen-removing treatment using Glc oxidase and catalase in the presence of Glc (Fabian, 1965) completely abolished DCA synthase activity (Table I). Molecular oxygen would participate as the final electron acceptor in the reaction, because hydrogen peroxide, almost in equal quantities to those of DCA, was detected in the reaction mixture with a molar ratio of 1.07 (hydrogen peroxide) versus 1 (DCA). Thus, the reaction stoichiometry of DCA synthase is summarized as follows: grifolic acid + O2 → DCA + H2O2. Furthermore, the oxidative reaction is likely to proceed through an ionic intermediate rather than radical species, because two typical radical trap agents, 2-methyl-2-nitrosopropane (Makino et al., 1981) and N-acetyl-Cys (Ates et al., 2008), did not inhibit the enzyme activity (Supplemental Table S1). These biochemical properties of the recombinant DCA synthase were quite similar to those reported previously for FAD oxidases, including cannabinoid synthases (Kutchan and Dittrich, 1995; Sirikantaramas et al., 2004; Taura et al., 2007).

Table I. Oxygen requirement for the DCA synthase reaction.

Substrate and enzyme solutions were preincubated individually with the indicated additives at 30°C for 1 h prior to initiation of the reactions. Data are means ± sd of triplicate measurements. Relative activity of 100% was 57.4 nkat mg−1 protein. U, Units.

| Treatment | Relative Activity (%) |

|---|---|

| None | 100.0 ± 4.5 |

| 40 mm Glc + 5 U of Glc oxidase + 10 U of catalase | Not detected |

| 40 mm Glc + boiled Glc oxidase + 10 U of catalase | 97.5 ± 4.2 |

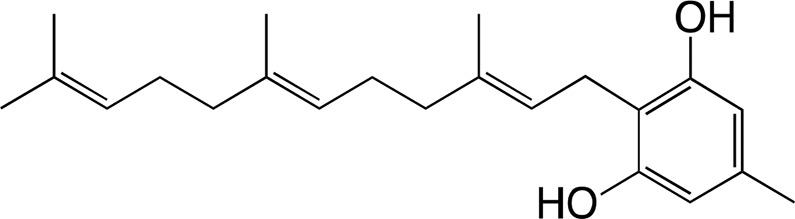

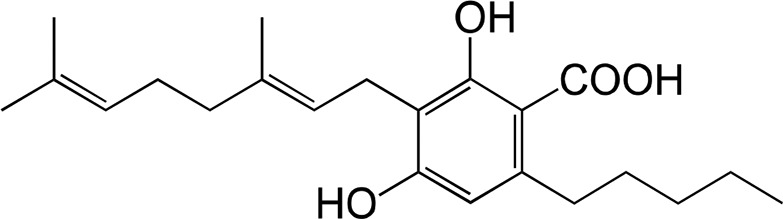

The substrate specificity of DCA synthase was analyzed using grifolic acid and its analogs, and the kinetic constants for each substrate were calculated. First, the recombinant DCA synthase oxidized grifolic acid with lowest Km and highest kcat values among the substrates tested herein (Table II). The resulting catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) was 5.61, which is similar to that reported for EcBBE (Gaweska et al., 2012) and more than 1,000-fold higher than those of THCA synthase and CBDA synthase (Supplemental Table S2; Taura et al., 1995, 1996). Therefore, the oxidative cyclization of grifolic acid by DCA synthase seems to be efficient enough to produce a large amount of DCA that accumulates in young leaves of R. dauricum (Taura et al., 2014). In contrast, the recombinant enzyme did not accept grifolin, the decarboxylated form of grifolic acid, as a substrate (Table II), suggesting that the carboxyl group is essential for substrate recognition of this enzyme. Likewise, DCA synthase did not catalyze the oxidation of cannabigerolic acid (Table II), the substrate for cannabinoid synthases. Cannabigerolic acid is a kind of prenylated alkylresorcylic acid like grifolic acid, but it has a larger alkyl chain and a shorter prenyl group compared with grifolic acid.

Table II. Steady-state kinetic parameters of the recombinant DCA synthase.

Data are means ± sd of triplicate measurements.

| Km | kcat | kcat/Km | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

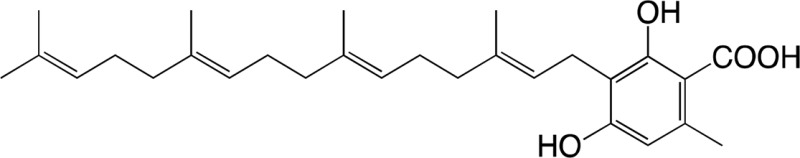

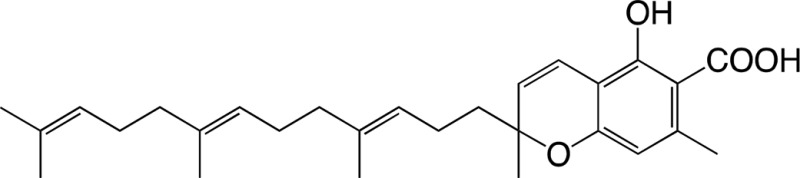

| Substrate Structures | Product Structures | μm | s−1 | s−1 μm−1 |

|

|

1.19 ± 0.20 | 6.53 ± 0.12 | 5.61 ± 0.82 |

| Grifolic acid | DCA | |||

|

Product not detected | - | - | - |

| Grifolin | ||||

|

Product not detected | - | - | - |

| Cannabigerolic acid | ||||

|

|

66.1 ± 12.7 | 2.14 ± 0.39 | 0.032 ± 0.001 |

| Cannabigerorcinic acid | Cannabichromeorcinic acida | |||

|

|

7.46 ± 1.85 | 0.131 ± 0.029 | 0.018 ± 0.002 |

| 3-Geranylgeranyl orsellinic acid | Diterpenodaurichromenic acida |

The absolute configuration of these products was not determined.

Next, to evaluate the effects of prenyl side chains, we prepared two prenyl chain analogs of grifolic acid, namely cannabigerorcinic acid (3-geranyl orsellinic acid; Shoyama et al., 1978) and 3-geranylgeranyl orsellinic acid, by acid-catalyzed prenylation of orsellinic acid (Crombie et al., 1988) and used them as substrates. Remarkably, DCA synthase could catalyze the oxidocyclization of both synthetic substrates to produce DCA analogs, although the calculated catalytic efficiencies were apparently lower than that for grifolic acid (Table II). The product obtained form cannabigerorcinic acid was cannabichromeorcinic acid, which was reported previously as a synthetic cannabinoid (Shoyama et al., 1984). The product obtained from 3-geranylgeranyl orsellinic acid was a novel DCA analog harboring a diterpenoid portion; therefore, we named it diterpenodaurichromenic acid.

With respect to the kinetic constants for each analog, the kcat value for cannabigerorcinic acid was comparable with that of grifolic acid; however, the Km value was more than 50-fold higher than that for grifolic acid (Table II). Thus, the farnesyl-to-geranyl conversion of the prenyl moiety in the substrate greatly lowered the affinity between enzyme and substrate. In contrast, when 3-geranylgeranyl orsellinic acid was used as a substrate, the kcat value was apparently reduced, whereas the Km value was of the same order as that for grifolic acid (Table II), suggesting that, although 3-geranylgeranyl orsellinic acid is an acceptable substrate for DCA synthase, it is rather hard to be cyclized in the active site of this enzyme. These results demonstrated that DCA synthase was relatively tolerant of the prenyl chain length of the substrate but mostly preferred grifolic acid, presumably because the farnesyl group is best suited for the active site. In contrast, DCA synthase strictly recognized the alkyl chain length because cannabigerolic acid with the pentyl group was not a suitable substrate for this enzyme.

Homology Modeling of DCA Synthase

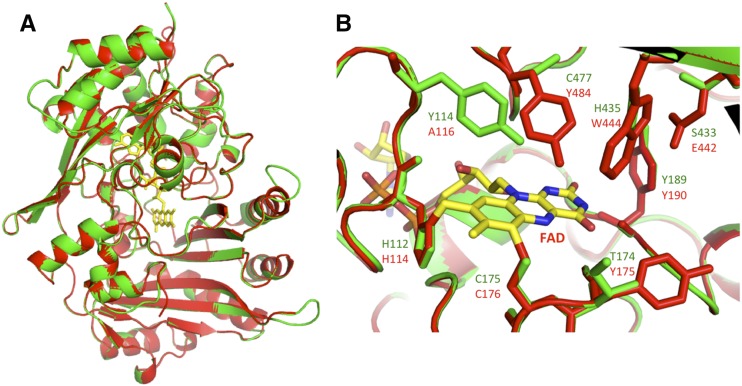

The homology model for DCA synthase was prepared using the crystal structure of THCA synthase as the template. As presented in Figure 6A, DCA synthase adopts almost the same overall topology as THCA synthase (Shoyama et al., 2012). In addition, the DCA synthase model places conserved His and Cys residues near the 8α and 6 positions, respectively, of the FAD isoalloxazine ring (Fig. 6B). This result strongly suggested that DCA synthase also features a bicovalent linkage with FAD via His-112 and Cys-175, as in the case of THCA synthase (Shoyama et al., 2012). Although the overall structure as well as the covalent linkage with the cofactor appear to be conserved, there are significant differences between the predicted active site residues of DCA synthase and THCA synthase (Fig. 6B). For example, Tyr-484 (top center), the general base in the THCA synthase reaction (Shoyama et al., 2012), is replaced by Cys-477 at the corresponding position of DCA synthase. Likewise, several amino acid residues surrounding FAD in THCA synthase also are substituted simultaneously in DCA synthase. These amino acid changes would be responsible for the differences in substrate coordination and/or catalytic processes between DCA synthase and THCA synthase. We perceive that x-ray crystallographic analysis of the enzyme-ligand complex would be required for detailed understanding of the unique catalytic features of DCA synthase.

Figure 6.

Homology model of DCA synthase constructed with the crystal structure of C. sativa THCA synthase (PDB ID: 3vte) as a template. A, Ribbon model for the overall structure of DCA synthase (green) superimposed on that of THCA synthase (red). B, Closeup views of the enzyme active sites. DCA synthase (green) was superimposed on the corresponding position of THCA synthase (red). The FAD molecule bicovalently linked to THCA synthase is depicted as a yellow stick model. The amino acid residues lining the active sites are indicated as one-letter codes in green (DCA synthase) or red (THCA synthase).

Phytochemical Analysis of Meroterpenoid Constituents in R. dauricum

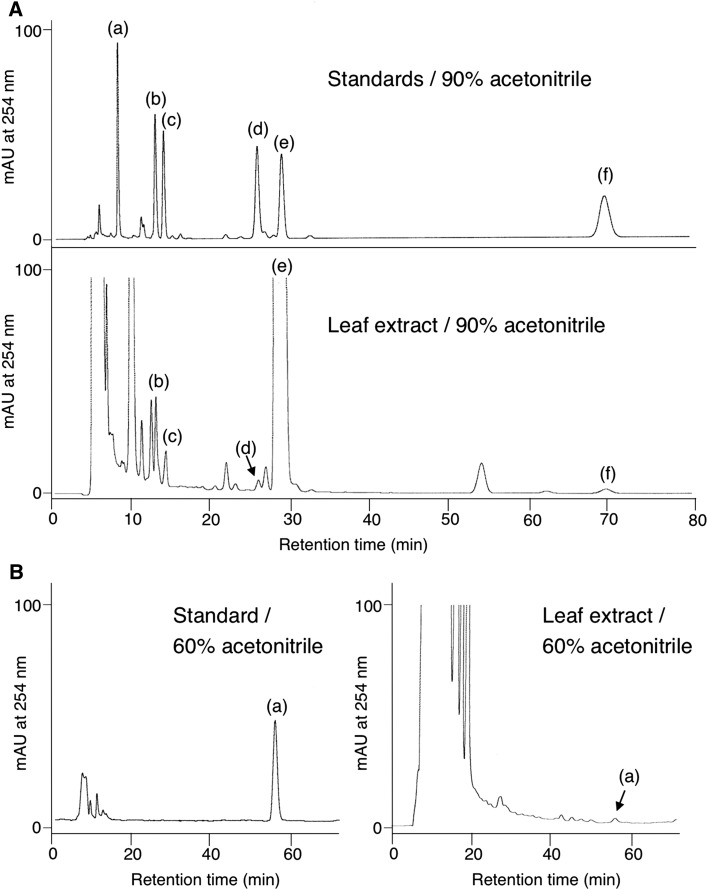

DCA synthase could accept prenyl chain analogs of the physiological substrate grifolic acid. Based on this in vitro result, we suspected that the prenyl chain analogs of DCA might actually be components in R. dauricum plants. To confirm this presumption, the methanol extract of young leaves was examined by HPLC and LC-PDA-ESI-MS analyses. As shown in Figure 7, the elution profile of the extract clearly showed peaks with retention times identical to those for cannabichromeorcinic acid and diterpenodaurichromenic acid, respectively, even though the peak intensities were apparently lower as compared with that of DCA. In addition, their MS and UV spectra, summarized in Table III, matched those of authentic samples. Thus, the presence of these DCA analogs was clearly identified in R. dauricum. Regarding their precursors, cannabigerorcinic acid as well as 3-geranylgeranyl orsellinic also were detected as minor constituents along with grifolic acid in the same leaf extract (Fig. 7; Table III). Therefore, R. dauricum contains meroterpenoids with C10, C15, and C20 isoprenoid moieties. The typical contents of the respective meroterpenoids in the young leaves, quantified by HPLC, are presented in Supplemental Figure S5. Presumably, DCA synthase catalyzes the biosynthesis of not only DCA but also prenyl chain analogs of DCA based on its in vitro substrate specificity, as described above.

Figure 7.

HPLC analyses of the R. dauricum young leaf extract to detect meroterpenoid constituents. A, Standard samples (top) and leaf extract (bottom) eluted with 90% acetonitrile. The instrument conditions are described in “Materials and Methods.” B, The same samples eluted using 60% acetonitrile so that the peak (a) in the extract could be well resolved. The peaks are as follows: (a), cannabigerorcinic acid; (b) grifolic acid; (c) cannabichromeorcinic acid; (d) 3-geranylgeranyl orsellinic acid; (e) DCA; (f) diterpenodaurichromenic acid. mAU, Milliabsorbance unit.

Table III. LC-PDA-ESI-MS analyses of meroterpenoid constituents in young leaves of R. dauricum.

| Peak Identifier in Figure 7 | Analyte | Retention Time/Mobile Phasea | HR-ESI-MS | MS/MSb | λmax |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| min | m/z | nm | |||

| (a) | Cannabigerorcinic acid | 8.5/A (55.7/B) | 303.15985 [M-H]− (calculated for C18H23O4−, 303.15964) | 259.2 [M-H-CO2]− | 223, 267, 303 |

| 285.2 [M-H-H2O]− | |||||

| (b) | Grifolic acid | 13.0/A | 371.22217 [M-H]− (calculated for C23H31O4−, 371.22224) | 327.4 [M-H-CO2]− | 225, 267, 305 |

| 353.2 [M-H-H2O]− | |||||

| (c) | Cannabichromeorcinic acid | 14.3/A | 301.14413 [M-H]− (calculated for C18H21O4−, 301.14399) | 257.2 [M-H-CO2]− | 256 |

| 283.2 [M-H-H2O]− | |||||

| (d) | 3-Geranylgeranyl orsellinic acid | 25.9/A | 439.28470 [M-H]− (calculated for C28H39O4−, 439.28484) | 395.4 [M-H-CO2]− | 224, 261, 302 |

| 421.4 [M-H-H2O]− | |||||

| (e) | DCA | 28.9/A | 369.20673 [M-H]− (calculated for C23H29O4−, 369.20659) | 325.3 [M-H-CO2]− | 256 |

| 351.2 [M-H-H2O]− | |||||

| (f) | Diterpenodaurichromenic acid | 70.4/A | 437.26834 [M-H]− (calculated for C28H37O4−, 437.26919) | 393.4 [M-H-CO2]− | 256 |

| 419.3 [M-H-H2O]− |

Secretion Property of DCA Synthase in Planta

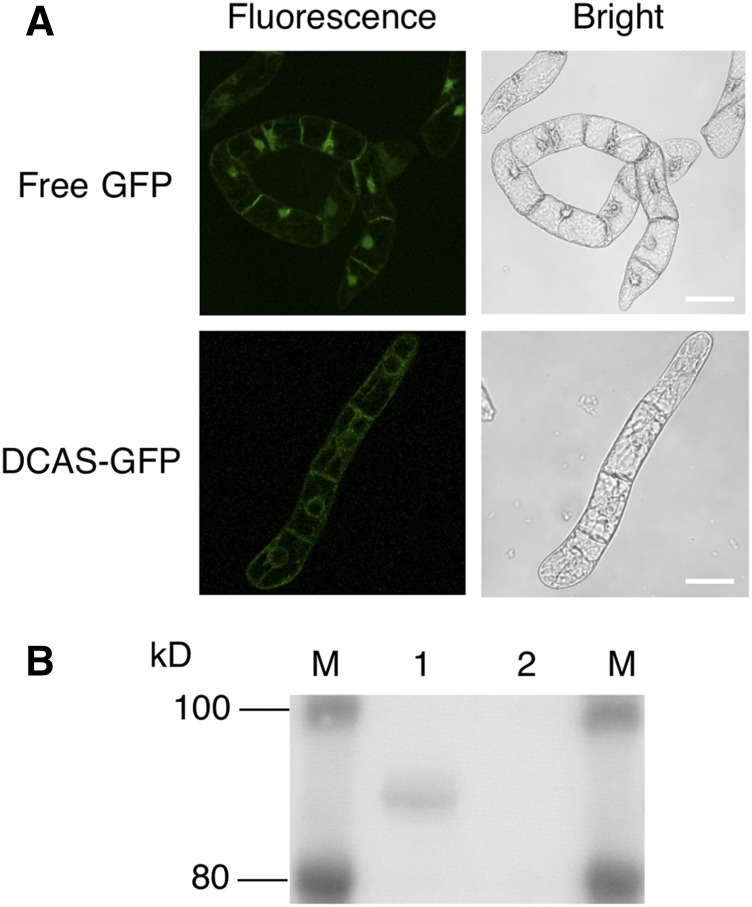

To estimate the subcellular localization of DCA synthase in plants, we stably transformed cultured tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) ‘Bright Yellow 2’ (BY-2) cells to express a fusion protein comprising the full-length DCA synthase and GFP and analyzed its distribution by confocal laser microscopy, western blotting, and enzyme assay. As shown in Figure 8A, the control cells expressing only GFP showed clear fluorescence in the cytoplasm and nucleus, whereas the fluorescence of the DCA synthase fusion protein was apparently weak but detectable in the endomembrane system of the transgenic BY-2 cells. However, this clearly suggested that most of the fusion protein was not retained in the endomembrane but secreted into the medium, as the western blotting using anti-GFP antibody detected an ∼89-kD band, which is the predicted size for the fusion protein in the sample prepared from culture supernatant (Fig. 8B, lane 1). However, the cell extract afforded no detectable signal in the western analysis, probably because the fusion protein in the endomembrane system was under the detection limit (Fig. 8B, lane 2). Furthermore, DCA synthase activity also was observed almost exclusively in the culture supernatant, as summarized in Table IV: the specific activity in the culture supernatant was 1,678 pkat mg−1 protein, whereas apparently weak enzyme activity (0.862 pkat mg−1 protein) was obtained for the cell extract, indicating that BY-2-derived DCA synthase was catalytically active and secreted efficiently even when it was fused to GFP. Consequently, DCA synthase was confirmed to behave as a secretory protein not only in P. pastoris cells but also in BY-2 cells, implying an extracellular localization of DCA synthase in R. dauricum plants.

Figure 8.

Analyses of the DCA synthase-GFP fusion protein expressed in suspension cultured cells of tobacco BY-2. A, Full-length DCA synthase was fused at its C-terminus to GFP and stably expressed in BY-2 cells. Fluorescence was observed with confocal microscopy. The top row represents cells expressing free GFP, whereas the bottom row shows fluorescence based on the fusion protein. Bars = 10 μm. B, Western-blot analysis with an anti-GFP antibody of the protein preparations from transgenic BY-2 expressing the fusion protein. Lane M, Prestained markers with the indicated molecular masses; lane 1, 20 μL of the culture medium; lane 2, 20 μL of the cellular protein extract.

Table IV. Distribution of DCA synthase activity between culture supernatant and cell extract prepared from the transgenic tobacco BY-2 cell culture expressing a DCA synthase-GFP fusion protein.

Data are means ± sd of triplicate measurements.

| Enzyme Preparation | Total Activity | Total Protein | Specific Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| pkat in mL of culture | mg in mL of culture | pkat mg−1 protein | |

| Culture supernatant | 161.6 ± 7.5 | 0.096 ± 0.013 | 1,678 ± 35.8 |

| Cell extract | 0.556 ± 0.051 | 0.643 ± 0.034 | 0.862 ± 0.041 |

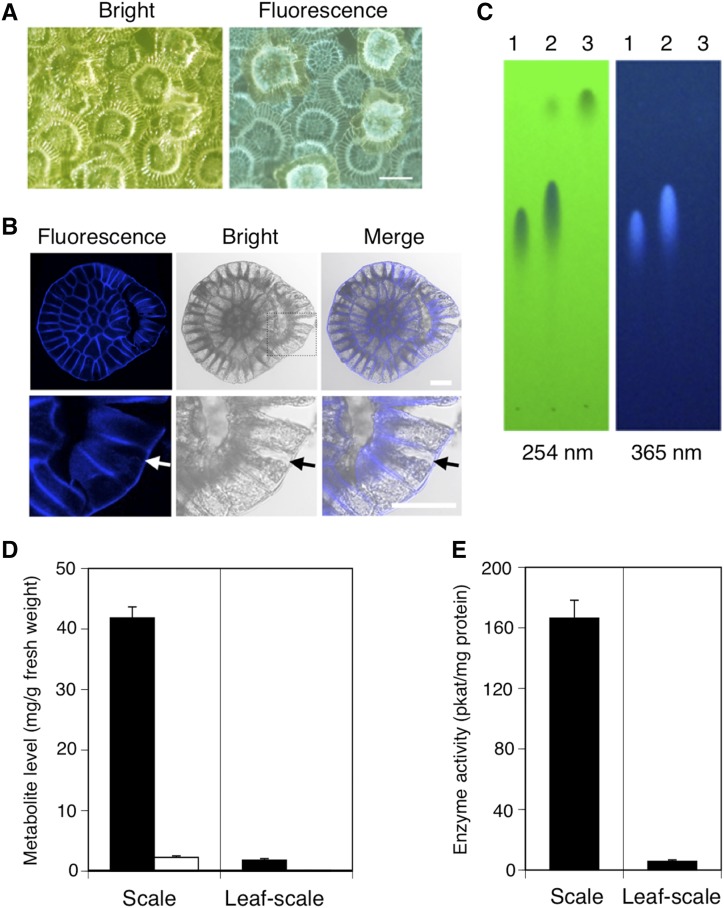

DCA Is Biosynthesized and Accumulated in the Glandular Scales of R. dauricum

R. dauricum is a typical lepidote Rhododendron species bearing numerous glandular scales on both the abaxial and adaxial surfaces of leaves (Desch, 1983). The scale is a multicellular structure of epidermal origin consisting of a stalk, attached to a leaf epidermis, and a circular-shaped expanded cap (Desch, 1983). Figure 9A shows the top view of the abaxial surface of a young leaf of R. dauricum covered with glandular scales. The cap of the scale is composed of relatively small central cells connected to stalk cells and surrounding inner and outer rim cells. During the microscopic observation of the leaf surface, we found that the scales showed light bluish autofluorescence under UV irradiation (Fig. 9A), suggesting that a fluorescent metabolite is accumulated specifically in the scales. Most of the scales showed a regularly compartmented fluorescence pattern, but some of them exhibited intense and diffused signals implying fluorescence leakage into the cytosol, probably due to physical damage in the scale structure.

Figure 9.

Analyses of glandular scales on the young leaves of R. dauricum. A, Closeup view of the abaxial side of a young leaf with numerous glandular scales under bright-field (left) and UV (right) irradiation. Bar = 100 μm. B, Confocal images of a detached scale under UV and bright-field irradiation. The bottom row shows enlarged images of the boxed part of the images in the top row. Arrows indicate cytoplasmic shrinkage in a rim cell. Bars = 20 μm. C, TLC analysis of scale extract and standard meroterpenoids visualized under irradiation at 254 nm (left) and 365 nm (right). Lane 1, DCA standard; lane 2, glandular scale extract; lane 3, grifolic acid standard. D, Distribution of meroterpenoid constituents between scales and scale-removed leaf tissue analyzed by HPLC. Black bars, DCA; white bar, grifolic acid. E, DCA synthase activity in the crude protein extract prepared from glandular scales (left) and scale-removed leaf tissue (right).

In order to analyze the subscale localization of autofluorescence more precisely, we detached the scales using an adhesive tape and observed the pattern using confocal fluorescence microscopy. It was quite an interesting observation that the autofluorescence was detected only in the periphery of scale cells showing a mesh-like pattern (Fig. 9B), suggesting that the fluorescent constituent is most likely localized in the apoplast of the scale. The observed scale was partially disrupted to its right (Fig. 9B), where cytoplasmic shrinkage also was observed for some cells, as indicated with the arrows (Fig. 9B, enlarged images in bottom row). The fluorescence at the corresponding position partly leaked into the cytosol; however, it largely remained in the mesh-like pattern even after cytoplasmic shrinkage (Fig. 9B). Therefore, we assumed that the fluorescent material in the apoplast of the scale might be partly associated with the cell wall components.

To identify the fluorescent compound, the methanol extract of scales was analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). The major fluorescent component in glandular scales was identified to be DCA, as the spot corresponding to DCA gave clear autofluorescence on the TLC plate under irradiation at 365 nm (Fig. 9C). In contrast, grifolic acid did not show fluorescence (Fig. 9C), indicating that the chromenic acid substructure in DCA contributes to the fluorescent property. In addition, HPLC analysis of the scale extract and scale-removed leaf extract clearly showed that DCA and grifolic acid are accumulated mainly in scales rather than in the leaf body (Fig. 9D). Likewise, protein extract prepared from glandular scales exhibited considerably higher DCA synthase activity than that of leaf body extract (Fig. 9E), strongly suggesting that DCA is biosynthesized and accumulated in glandular scales.

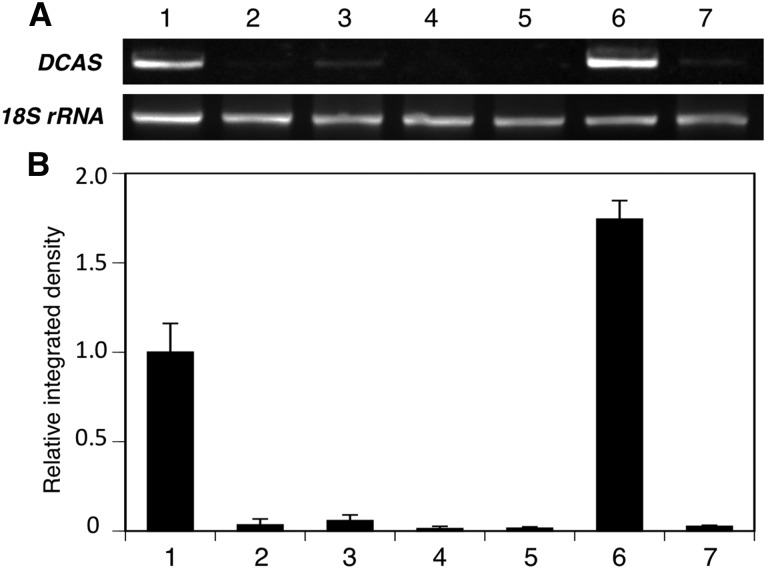

We also studied the tissue-specific expression of the DCA synthase gene by means of semiquantitative RT-PCR using gene-specific primers. Agarose gel analysis demonstrated that the DCA synthase gene is clearly expressed at a higher level in young leaves and in lesser amounts in mature leaves and twigs (Fig. 10). This tissue distribution pattern agreed well with the previously reported DCA content in each tissue (Taura et al., 2014). In addition, a much larger amount of PCR product was detected for the sample from scales in comparison with the sample from scale-removed young leaves (Fig. 10), demonstrating that the DCA synthase gene is expressed predominantly in the glandular scales. Based on all results of the assays at the chemical, enzymatic, and genetic levels, we concluded that the glandular scales are the site of DCA biosynthesis in R. dauricum plants. The extracellular localization of DCA autofluorescence seemed to be reasonable because DCA synthase is a secretory biosynthetic enzyme (Fig. 8).

Figure 10.

Analysis of the tissue distribution of DCA synthase transcripts in R. dauricum by semiquantitative RT-PCR. A, Agarose gel electrophoresis of a DCA synthase gene fragment (557 bp) amplified using gene-specific primers. The 18S rRNA gene fragment (663 bp) was amplified as a housekeeping control gene. Numbers indicate young leaves (1), mature leaves (2), twigs (3), flowers (4), roots (5), glandular scales (6), and scale-removed leaves (7). B, The band densities of DCA synthase fragments were normalized with that of 18S rRNA and are presented as means ± sd of triplicate assays, in which the expression level in young leaves was set to 1. Numbers indicate the same tissues as shown in A.

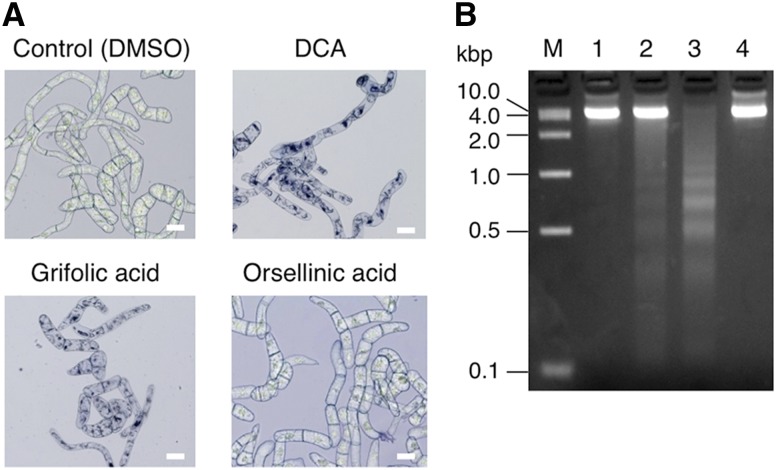

DCA and Grifolic Acid Are Cell Death-Inducing Phytotoxic Metabolites

As described above, DCA is accumulated in the extracellular compartment, the apoplast of glandular scales. With respect to the reason for this specific localization, we assumed that DCA might be a toxic metabolite and, thus, has to be excluded from plant cells. To confirm this possibility, we investigated the phytotoxic properties of DCA and its precursors, grifolic acid and orsellinic acid, using tobacco BY-2 cells as our experimental system. First, the cell viability of BY-2 cells after the treatment with each compound was measured by Trypan Blue staining. As shown in Figure 11A, 50 μm DCA and grifolic acid induced almost 100% cell death in BY-2 culture within 24 h of treatment, whereas orsellinic acid, the phenolic precursor, had no significant effects on the viability of BY-2 cells, suggesting that the prenylation of orsellinic acid is crucial for the phytotoxic effects. In addition, it was of interest that DNA laddering as well as smearing were detectable for genomic DNA samples from DCA- and grifolic acid-treated cells, wherein the laddering was more obviously detected for grifolic acid-treated cells (Fig. 11B). Therefore, DCA- and grifolic acid-induced cell death may be associated with the apoptotic pathway, at least in part. Although a detailed study should be conducted to clarify the efficacy and precise mechanism of their cytotoxicity, this report provides obvious evidence that DCA and grifolic acid are cell death-inducing phytotoxic meroterpenoids, similar to the cannabinoids such as THCA and cannabigerolic acid sequestered in the trichome head of C. sativa (Sirikantaramas et al., 2005).

Figure 11.

Phytotoxic effects of DCA and grifolic acid on suspension cultured tobacco BY-2 cells. A, Trypan Blue staining of DCA-, grifolic acid-, or orsellinic acid-treated cells. Five-day-old cell cultures were incubated with 50 µm of each indicated compound for 24 h and then stained with Trypan Blue. Control cells were treated with the solvent (DMSO) only. Bars = 100 µm. B, Agarose gel electrophoresis of genomic DNA from BY-2 cells treated as in A. DNA was separated on a 2% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. Lane M, Marker DNA with the indicated sizes; lane 1, control cells; lane 2, DCA-treated cells; lane 3, grifolic acid-treated cells; lane 4, orsellinic acid-treated cells.

DISCUSSION

Molecular and Biochemical Characterization of DCA Synthase

Meroterpenoids, produced by plants, bacteria, and fungi, are natural products that partially originate from the isoprenoid pathway (Matsuda and Abe, 2016). Plant meroterpenoids include many prenylated aromatics, such as flavonoids, isoflavonoids, stilbenoids, coumarin, quinone, phloroglucinol, and resorcinol harboring isoprenoid portions, and are a remarkable class of natural products because of their unique pharmacological and biological activities (Singh and Bharate, 2006; Rivière et al., 2012; Veitch, 2013; Chen et al., 2014; Mechoulam et al., 2014; Dugrand-Judek et al., 2015; Widhalm and Rhodes, 2016). Thus, biosynthetic studies of plant meroterpenoids have been conducted extensively in recent years, especially on aromatic prenyltransferases (Yazaki et al., 2009) and oxidocyclases belonging to FAD oxidases (Sirikantaramas et al., 2004; Taura et al., 2007) and P450 enzymes (Welle and Grisebach, 1988; Larbat et al., 2007). Physiologically, many plant meroterpenoids serve as chemical defense components in plants. For example, sophoraflavanone G, a lavandulyl flavanone from the genus Sophora, shows a potent antibacterial activity (Tsuchiya and Iinuma, 2000), whereas furanocoumarins, derived from prenylated phenylpropanoids, are defensive against various kinds of herbivores (Zangerl and Berenbaum, 1990). It is also of interest that these hydrophobic meroterpenoids, in addition to cannabinoids, are secreted into apoplastic compartments after their biosynthesis (Yamamoto et al., 1996; Sirikantaramas et al., 2005; Voo et al., 2012), as is the case with various hydrophobic terpenoids accumulated in the secretory cavity of glandular trichomes (Lange, 2015). In contrast to these well-documented examples, the biosynthetic mechanism, tissue localization, and physiological function of DCA had remained unclear largely because the gene responsible for DCA biosynthesis was not characterized.

In this study, we cloned a cDNA coding for DCA synthase from young leaves of R. dauricum. Phylogenetic analysis and amino acid alignment demonstrated that the primary structure of DCA synthase has appreciable homologies to plant FAD oxidases and contains conserved residues essential for novel bicovalent flavinylation (Leferink et al., 2008). VAO family FAD oxidases are widely distributed across plant species and are divergently evolved to catalyze oxidative reactions in various specialized metabolic pathways (Leferink et al., 2008). Among them, DCA synthase is the third example of meroterpenoid oxidocyclases, the first two being THCA synthase and CBDA synthase. However, DCA synthase has a novel characteristic as the enzyme that specifically cyclizes the farnesyl group in a natural meroterpenoid product of plant origin. It is noteworthy that flavoprotein oxidases with similar structure and function have evolved in genetically distinct plant species, C. sativa and R. dauricum, to produce respective pharmacologically valuable constituents. Hitherto, CBCA synthase in C. sativa and glyceollin synthase in Glycine max also have been identified to catalyze prenyl to chromene cyclization like DCA synthase (Welle and Grisebach, 1988; Morimoto et al., 1997); however, these enzymes have not been characterized at the molecular level.

Although the reactions catalyzed by VAO flavoproteins are variable, they all share common structural features and FAD-dependent reaction mechanisms (Leferink et al., 2008). Similarly, DCA synthase also contains covalently linked flavin as a coenzyme. In addition, this enzyme has an absolute requirement for molecular oxygen and releases hydrogen peroxide equal to the produced DCA, as reported for FAD oxidases. Based on these observations, we propose a reaction mechanism for DCA synthase in a flavin- and oxygen-dependent manner, as illustrated in Figure 12. With this mechanism, first, the flavin molecule accepts a hydride from the benzylic position of grifolic acid; simultaneously, a basic residue of the enzyme abstracts a proton from a phenolic hydroxyl group. These steps produce a reduced flavin and an ionic intermediate in the active site. The subsequent step is the stereospecific electrocyclization to form DCA and the hydride ion transfer from the reduced flavin to molecular oxygen, resulting in hydrogen peroxide formation and reoxidation of the flavin for the next reaction cycle.

Figure 12.

Proposed reaction mechanism of DCA synthase. Two electrons from the substrate are accepted by enzyme-bound flavin and then transferred to molecular oxygen to reoxidize flavin. DCA is synthesized from the ionic intermediate via stereoselective cyclization by the enzyme. B indicates the proposed basic residue of the enzyme.

In the case of THCA synthase, for which a crystal structure was elucidated, Tyr-484 contributes as a catalytic base to accept proton from the substrate (Shoyama et al., 2012). This residue is not conserved in DCA synthase, as depicted in the molecular model structure (Fig. 6B). It is notable, however, that the side chain of Tyr-114 in DCA synthase alternatively protrudes to the putative substrate-binding pocket (si-side of FAD; Fig. 6B), implying that Tyr-114 is a possible candidate for the catalytic base in the DCA synthase reaction. Actually, the catalytic base residues in plant FAD oxidases are not necessarily conserved at the specific position (Supplemental Fig. S1), as discussed previously by Daniel et al. (2015). Nevertheless, we regard that crystal structure determination and site-directed mutational studies of DCA synthase are essential for a precise understanding of the structure-function relationship of the reaction. These ongoing projects would demonstrate the structural basis underlying the differences in substrate recognition and cyclization processes between DCA synthase and cannabinoid synthases and might provide valuable insights into the rational design of enzyme active sites to synthesize novel unnatural meroterpenoids.

Kinetic studies using various substrates clearly demonstrated that DCA synthase is highly specific to grifolic acid. The catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) for DCA formation was 5.61, which was much higher than those of THCA synthase and CBDA synthase (Taura et al., 1995, 1996). This result may be reasonable because the oxidocyclization process catalyzed by DCA synthase is rather simple: it proceeds without the rearrangement of the geometrical configuration of the prenyl group proposed for the reaction schemes of THCA synthase and CBDA synthase (Sirikantaramas et al., 2004; Taura et al., 2007). Unlike grifolic acid, DCA synthase did not accept grifolin and cannabigerolic acid as a substrate. These results are relevant to the fact that R. dauricum does not produce neutral meroterpenoids without carboxyl group and cannabinoid-type metabolites with a pentyl side chain (Taura et al., 2014).

Of particular interest, DCA synthase showed enzyme activity on substrate analogs containing different prenyl groups to produce the corresponding chromenic acid derivatives, namely cannabichromeorcinic acid and diterpenodaurichromenic acid. Consequently, DCA synthase is a novel oxidocyclase that could cyclize multiple prenyl moieties in plant meroterpenoid biosynthesis. In addition, phytochemical analysis using LC-PDA-ESI-MS identified cannabichromeorcinic acid and diterpenodaurichromenic acid, probably produced by DCA synthase, as minor constituents in leaf extract of R. dauricum, although the absolute configuration of these DCA analogs has yet to be characterized. These results indicated the possibility that an unidentified aromatic prenyltransferase involved in the DCA pathway might promiscuously accept prenyl donor substrates to produce orsellinic acid derivatives with geranyl, farnesyl, and geranylgeranyl portions as the substrates for DCA synthase. The corresponding prenyltransferase is exceptionally remarkable because most of the aromatic prenyltransferases involved in plant specialized metabolism are strictly selective to either dimethylallyl pyrophosphate or geranyl pyrophosphate (Munakata et al., 2014).

Localization and Possible Physiological Function of DCA in R. dauricum

Rhododendron species are classified into two types, lepidote or elepidote Rhododendron, based on whether they have glandular scales or not (Desch, 1983). Morphologically, the stalked architecture of glandular scales is somewhat similar to the capitate stalked trichomes on plants belonging to Lamiaceae and Cannabaceae (Lange, 2015); however, glandular scales develop the expanded cap comprising the central and rim cells and do not have an obvious secretory cavity, although they contain hydrophobic sesquiterpenoids (Doss, 1984; Doss et al., 1986). In this study, we also demonstrated that DCA is produced and accumulated specifically in the glandular scales of R. dauricum based on several lines of evidence: DCA synthase gene expression, enzyme activity, as well as DCA content being observed predominantly in glandular scales rather than scale-removed leaf tissues. In addition, the extracellular distribution of DCA-based autofluorescence and the secreted nature of the recombinant DCA synthase expressed in a plant cell culture suggested the possibility that the DCA synthase reaction takes place in the apoplast of the glandular scales, like the THCA synthase reaction that occurs in the secretory cavity of glandular trichomes (Sirikantaramas et al., 2005).

Such an extracellular biosynthesis and accumulation of DCA presumably provides several advantages for R. dauricum plants. (1) DCA and grifolic acid could effectively serve as chemical barriers in the apoplast of glandular scales, the outermost layer of the plant, because these meroterpenoids exhibit antimicrobial activities (Hashimoto et al., 2005). (2) Hydrogen peroxide, the by-product of DCA synthase, also may take part in chemical defense because of its antimicrobial property as described in relation to FAD-dependent carbohydrate oxidases (Custers et al., 2004). (3) As demonstrated in this study, grifolic acid and DCA are potentially phytotoxic metabolites. Thus, they should be stored in the apoplast to avoid cellular damage in R. dauricum plants. Therefore, grifolic acid has to be effectively secreted once it is biosynthesized by an aromatic prenyltransferase. Many hydrophobic specialized metabolites are secreted, probably to serve in plant defense and/or to avoid self-poisoning, although only a few studies have been reported with respect to the mechanisms for transportation of these components (Shitan, 2016). For example, a diterpenoid sclareol in Nicotiana plumbaginifolia and monolignols in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) are transported to the apoplast by ATP-binding cassette transporters (Stukkens et al., 2005; Alejandro et al., 2012). In addition, a recent study using hairy root culture of Lithospermum erythrorhizon has demonstrated that shikonin, a kind of naphthoquinone meroterpenoid, is secreted utilizing pathways common to the ADP ribosylation factor/guanine nucleotide exchange factor system and actin filament polymerization (Tatsumi et al., 2016). We assume that a specific molecular mechanism, which might share similarity with either of them, would transport grifolic acid into the apoplast of glandular scales to circumvent self-poisoning and for the following DCA biosynthesis.

In conclusion, we conducted molecular and biochemical characterization of DCA synthase, a novel oxidocyclase specific to grifolic acid, to produce DCA with anti-HIV properties. The DCA synthase gene and the recombinant enzyme would be applicable for the semisynthesis and biomimetic heterologous production of DCA, because grifolic acid can be obtained in a large quantity from the inedible mushroom Albatrellus dispansus (Hashimoto et al., 2005), and more recently, a de novo production system of grifolic acid has been established using Aspergillus oryzae transformed with a grifolic acid-producing gene cluster from Stachybotrys bisbyi (Li et al., 2016). In addition, the ecological significance of DCA biosynthesis in plants also would be an interesting research subject. For example, DCA might participate in chemical defense against insects, as cannabinoids, structurally related to DCA, have insect-repellent properties (Rothschild and Fairbairn, 1980).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Reagents

Rhododendron dauricum plants were cultivated at the Experimental Station for Medicinal Plant Research at the University of Toyama. Suspension-cultured tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) BY-2 cells were obtained from the RIKEN Bioresource Center and cultured in a modified Murashige and Skoog medium as described previously (Sirikantaramas et al., 2005).

Chemical reagents were purchased from Wako Pure Chemicals unless stated otherwise. DCA, grifolic acid, grifolin, and cannabigerolic acid were from our laboratory collection (Taura et al., 2014). Previously reported meroterpenoids, cannabigerorcinic acid and cannabichromeorcinic acid, were synthesized as described by Shoyama et al. (1978, 1984). The standard sample of 3-geranylgeranyl orsellinic acid was chemically synthesized, using p-toluenesulfonic acid as a catalyst, from orsellinic acid and geranylgeraniol (Sigma-Aldrich), as described by Crombie et al. (1988). Diterpenodaurichromenic acid in racemic form was synthesized from 3-geranylgeranyl orsellinic acid by chemical oxidation using dichlorodicyanobenzoquinone (Hashimoto et al., 2005). The structures were verified by obtaining their physical data as summarized below using a JNM-ECA500 NMR spectrometer (JEOL) and an LC-PDA-ESI-MS system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The 1H-NMR spectra of 3-geranylgeranyl orsellinic acid and diterpenodaurichromenic acid were almost identical to those reported for grifolic acid and DCA (Kashiwada et al., 2001; Li et al., 2016), respectively, except for signals corresponding to prenyl chain differences (Supplemental Figs. S6 and S7).

3-Geranylgeranyl orsellinic acid: 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 11.85 (s, 1H), 6.26 (s, 1H), 5.28 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 5.08 to 5.10 (m, 3H), 3.43 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 2.52 (s, 3H), 2.01 to 2.06 (m, 12H), 1.82 (s, 3H), 1.68 (s, 3H), 1.59 (overlapped, 9H). HRMS (ESI, negative): m/z calculated for C28H39O4 [M-H]−: 439.28483, found 439.28439. λmax (PDA): 224, 261, 303 nm. Diterpenodaurichromenic acid: 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 11.85 (s, 1H), 6.73 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 6.22 (s, 1H), 5.48 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 5.08 to 5.12 (m, 3H), 2.52 (s, 3H), 2.04 to 2.09 (m, 6H), 1.95 to 1.98 (m, 4H), 1.73 to 1.78 (m, 2H), 1.68 (s, 3H), 1.60 (s, 3H), 1.59 (s, 3H), 1.57 (s, 3H), 1.40 (s, 3H). HRMS (ESI, negative): m/z calculated for C28H37O4 [M-H]−: 437.26919, found 437.26838. λmax (PDA): 255 nm.

Transcriptome Sequencing and Screening of Candidate Genes for RdFADOX

Total RNA was extracted from young leaves of R. dauricum using the RNAqueous kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Then, the cDNA library was prepared using the TruSeq RNA sample preparation kit with a low-throughput protocol (Illumina). The cDNA clusters generated on a Single-Read flow cell were sequenced on the Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx as 100-bp single-end reads to generate a data set consisting of 35,093,217 reads. The resulting sequence reads were assembled de novo using Rnnotator version 2.4.12 (Martin et al., 2010) with the default parameters to obtain 71,944 cDNA contigs with an average length of 535 bp. These transcriptome data were used as the DNA database for a local tBLASTn homology search using the BioEdit program version 7.2.5 (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html). Three putative nucleotide sequences encoding R. dauricum FAD oxidases (RdFADOX1–RdFADOX3) were mined from the databases using amino acid sequences of cannabinoid synthases as queries. The FPKM value for each gene was calculated according to the reported scheme (Trapnell et al., 2010).

cDNA Cloning of RdFADOX1 to RdFADOX3

The gene-specific oligonucleotide primers and PCR conditions listed in Supplemental Table S3 were used for amplification of the RdFADOX1 to RdFADOX3 gene fragments. To obtain complete cDNA sequences, including untranslated regions, 3ʹ- and 5ʹ-RACE reactions were conducted as described previously (Taura et al., 2016). The cDNA template was prepared by RT of young leaf RNA using ReverTra Ace (Toyobo) and dT17AP primer. The 3ʹ-RACE products for RdFADOX1 to RdFADOX3 genes were obtained using the adapter primer AP and specific primers FADOX(1–3)-3R, respectively. The template for 5ʹ-RACE was prepared by polyadenylation of the cDNA using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (Takara Bio) in the presence of deoxyadenine. First-round PCRs were conducted with dT17AP primer and specific primers FADOX(1–3)-5R1. Then, nested PCR using primers AP and FADOX(1–3)-5R2 amplified the 5ʹ-RACE products for RdFADOX1 to RdFADOX3 genes. All RACE products were subcloned into pMD-19 (Takara Bio) and sequenced on a 3130 DNA sequencer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The full-length RdFADOX1 to RdFADOX3 coding sequences were amplified with primers FADOX(1–3)-Fw and FADOX(1–3)-Rv, respectively, and subcloned into the expression vector pPICZA (Thermo Fisher Scientific) predigested with EcoRI and SalI using the In-Fusion HD cloning reagent (Clontech). The partial Kozak sequence (AAAACA) was inserted prior to the translational start ATG codon for optimal yeast expression (Hamilton et al., 1987). The expression vectors were designed to express the recombinant proteins in Pichia pastoris in the presence of methanol.

Computational Analyses of RdFADOX Sequences

The subcellular location and protein-sorting signal were predicted with the online programs TargetP (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TargetP/) and PSORT (http://www.psort.org/). Protein motifs were scanned using PfamScan (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/pfa/pfamscan/) and ScanProsite (http://prosite.expasy.org/scanprosite/). Multiple alignment of FAD oxidases, including RdFADOX1 to RdFADOX3, was carried out using the Clustal Omega program (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/). A neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was drawn by 1,000 bootstrap tests using MEGA6.06 software (http://www.megasoftware.net). The homology model of DCA synthase (RdFADOX1) was generated with SWISS-MODEL software (https://swissmodel.expasy.org) using the crystal structure of THCA synthase from Cannabis sativa (Protein Data Bank identifier 3vte) as the template. The model quality was evaluated by a Ramachandran plot, using RAMPAGE (http://mordred.bioc.cam.ac.uk/∼rapper/rampage.php), to confirm that most amino acid residues were grouped in the energetically allowed regions. All protein figures were rendered with PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org).

Heterologous Expression of RdFADOX1 to RdFADOX3 in P. pastoris

The pPICZA expression vectors, containing one of the full-length RdFADOX genes, were introduced individually to P. pastoris strain KM71H (Thermo Fisher Scientific) by electroporation, and the transformants were selected on YPD agar plates containing 1 mg mL−1 zeocin (InvivoGen). Protein expression in P. pastoris was accomplished essentially as described by Weis et al. (2004). The three minimal media used herein contained 200 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6), 1.34% yeast nitrogen base (Difco Laboratories), and 4 × 10−5% d-biotin and differed with respect to the carbon source of 10 g L−1 Glc or 1% or 5% methanol for BMD, BMM2, or BMM10, respectively. A single colony was inoculated into Erlenmeyer flasks containing 10 mL of BMD and cultivated at 25°C for 60 h. Then, 10 mL of BMM2 was added to the culture to initiate protein expression, and 2 mL of BMM10 was fed every 24 h after the onset of the induction. After 96 h of induction, the culture was centrifuged to obtain culture supernatant and cell pellet. The cells were washed twice with water and suspended in buffer A (10 mm potassium phosphate buffer [pH 7] containing 3 mm mercaptoethanol). Then, cellular extract was prepared by vortexing vigorously in the presence of glass beads. DCA synthase activity in the culture medium and cell extract was assayed as described below.

Purification and Biochemical Properties of the Recombinant DCA Synthase

The P. pastoris strain harboring the DCA synthase (RdFADOX1) gene was precultured in a large volume (400 mL) of BMD medium, and protein expression was induced by adding BMM2 (400 mL) followed by BMM10 (80 mL) every 24 h. The culture was harvested after 96 h of induction and centrifuged at 20,000g for 15 min. The supernatant (∼1,000 mL) was diluted 3-fold with buffer A and applied to a hydroxylapatite column (Nacalai Tesque; 1 cm × 10 cm) equilibrated with buffer A. The column was washed with three column volumes of the same buffer, and bound proteins were eluted with a 400-mL linear gradient of buffer A to 0.5 m potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7) containing 3 mm mercaptoethanol. Fractions containing DCA synthase activity were concentrated and dialyzed against buffer B (10 mm sodium citrate buffer [pH 5.5] containing 3 mm mercaptoethanol). The dialysate was applied to a 1-cm × 10-cm column containing TOYOPEARL CM-650M (Tosoh) equilibrated with buffer B. The column was washed with the same buffer, and DCA synthase was eluted with a 300-mL gradient of NaCl (0–0.5 m) in buffer B. The most active fractions eluted ∼0.2 m NaCl and were collected and used for the following biochemical characterization. The typical yield of the purified DCA synthase was 100 to 120 μg from 1,000 mL of culture supernatant.

The purity and subunit molecular mass of the recombinant DCA synthase were verified by SDS-PAGE analysis using a 12.5% acrylamide gel. The native molecular mass of DCA synthase was determined by gel filtration chromatography on a 2.5- × 75-cm Sephacryl S-200 HR column (GE Healthcare) calibrated with standard proteins. The N-terminal amino acid sequence of the purified DCA synthase was determined on a PPSQ-21 protein sequencer (Shimadzu). The carbohydrate staining of the enzyme was performed using the Glycoprotein Western Detection Kit (Clontech). The absorption and fluorescent emission spectra of the enzyme, dissolved in buffer A at a concentration of 0.23 mg mL−1, were recorded on a NanoDrop 2000c (Thermo Scientific) and a F-4500 (Hitachi Hi-Technologies) spectrophotometer, respectively. AMP was released from the purified DCA synthase by hydrolysis at 99°C for 10 min in the presence of 10 mm HCl (Kutchan and Dittrich, 1995) and then detected by a reverse-phase HPLC system, as described below, using 1% acetonitrile containing 10 mm ammonium formate as a mobile phase at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1. The mass spectrum of the AMP also was analyzed by an LC-ESI-MS system as described below.

The molecular oxygen requirement was assayed by DCA synthase reaction using substrate and enzyme solutions preincubated in the presence of 40 mm Glc, 5 units of Glc oxidase, and 10 units of catalase at 30°C for 1 h. The hydrogen peroxide produced by a by-product of DCA synthase was quantified using the Amplex Red Hydrogen Peroxide/Peroxidase Assay Kit as described by the manufacturer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Standard Assay Conditions for DCA Synthase

The standard reaction mixture consisted of 10 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6), 20 μm grifolic acid (or substrate analog), and the protein solution in a total volume of 100 μL. The reaction was incubated at 30°C for 30 min and terminated by adding 100 μL of methanol. The 10-μL aliquots were analyzed by HPLC and LC-PDA-ESI-MS to quantitate and characterize the reaction product, respectively. The stereoselectivity of the DCA-producing reaction was examined by a chiral HPLC device using a CHIRALPAK AD-H column (Daicel) as described previously (Taura et al., 2014).

HPLC and LC-PDA-ESI-MS Analyses of the Reaction Products

The enzyme reaction products were routinely analyzed and quantified by an HPLC system (Tosho) equipped with a Cosmosil 5C18-MS-II column (4.6 mm × 150 mm; Nacalai Tesque), as described previously (Taura et al., 2014). Elution was performed isocratically with aqueous acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1. The acetonitrile concentration was set for each product: 85% for DCA, 75% for cannabichromeorcinic acid, and 95% for diterpenodaurichromenic acid. The products were detected by absorption at 254 nm and quantified using calibration curves of the standard compounds. The samples also were analyzed by an LC-PDA-ESI-MS system (Thermo Fisher Scientific), composed of an Accela 600 HPLC pump, an Accela PDA detector, and an LTQ-Orbitrap-XL ETD Hybrid Ion Trap-Orbitrap mass spectrometer, to characterize the products in detail. The column and mobile phase were the same as those used for the HPLC analysis. The high-resolution MS (negative), MS/MS, and UV spectra were collected as described previously (Taura et al., 2016).

Enzyme Kinetics

The enzyme reactions were conducted in a similar manner to the standard assay conditions, using six concentrations (5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 μm) of substrates, in the presence of 0.37 μg of the purified DCA synthase. The reaction products were quantified by HPLC, and the kinetic constants were calculated by fitting the velocity data at each substrate concentration to Hanes-Woolf plots.

Phytochemical Analysis of Young Leaf Extract

Fresh young leaves (100 mg) were frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground into a fine powder by pestle and mortar. The powder was then extracted with 1 mL of methanol, and the resulting sample was subjected to HPLC as described above for quantitative analyses. The chromatographic separations were performed with 90% acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid at a flow rate of 0.25 mL min−1. Alternatively, 60% acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid was used as a mobile phase for the better separation of cannabigerorcinic acid from other constituents. The LC-PDA-ESI-MS analysis also was performed as described above, to identify the respective metabolites.

GFP Fusion Gene Construction and Expression in Tobacco BY-2 Cells

The GFP gene used in this study is the synthetic variant S65T cloned in pUC18 (Niwa et al., 1999). First, the GFP coding sequence was amplified with primers GFP-Fw and GFP-Rv and then introduced into the binary vector pBI121 (Clontech) between BamHI and SacI restriction sites to create pBI121-GFP. Full-length DCA synthase cDNA, amplified with DCAS-Fw and DCAS-Rv, was subcloned into pBI121-GFP by use of XbaI and BamHI restriction sites to construct pBI121-DCAS-GFP. The partial Kozak sequence (AACA; Lütcke et al., 1987) was inserted prior to the start codon of DCA synthase via the primer DCAS-Fw. pBI121-GFP and pBI121-DCAS-GFP were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens LBA4404 by electroporation. BY-2 cells were transformed by A. tumefaciens infection as described (An, 1987) and selected on solidified Murashige and Skoog medium containing kanamycin (100 μg mL−1). The suspension cultures of the transgenic cells were established in liquid Murashige and Skoog medium containing kanamycin and subcultured every 7 d. The 5-d-old culture (1 mL) was centrifuged to obtain culture supernatant and cell pellet. Cells were suspended in 1 mL of buffer A, and the extract was prepared using a microtube BioMasher homogenizer (Nippi), for DCA synthase assay and western blotting, along with the culture supernatant. Western blotting was performed using an anti-GFP antibody (MBL) as described previously (Kurosaki and Taura, 2015). The GFP fluorescence in the transgenic cells was observed by confocal microscopy as described below.

Collection and Analyses of the Glandular Scales from Young Leaves of R. dauricum

The glandular scales from both sides of young leaves were detached using a semitransparent adhesive tape (Scotch; 3M). The scales were suspended in PBS by gentle sonication, collected by centrifugation at 3,000g for 1 min, and then used for the following analyses. The methanol extract was prepared using a BioMasher, and the constituents were analyzed by TLC using a silica gel F254 plate (Merck) developed with chloroform:methanol (2:1). The DCA and grifolic acid contents in the extract also were analyzed by HPLC as described above. The crude protein extract of the collected scales was prepared with buffer A, using a BioMasher, and used for DCA synthase assay. The autofluorescence image of an isolated glandular scale was taken as described below.

Microscopy Analyses

Two different fluorescence microscopes were used in this study for respective purposes. A BX-50 microscope equipped with a BX-FLA fluorescent unit (Olympus) was used to observe epifluorescence images of the R. dauricum leaf surface with a band-pass excitation filter at 330 to 385 nm and a long-pass filter at 420 nm. Confocal images of isolated glandular scales were taken with a laser-scanning fluorescence microscope (LSM 700; Carl Zeiss), using a filter set of 405 nm excitation and 420 to 480 nm emission, whereas GFP signals expressed in BY-2 cells were excited at 488 nm and collected at 505 to 530 nm.

Expression Analysis of the DCA Synthase Gene by Semiquantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from young leaves, mature leaves, twigs, flowers, roots, glandular scales, and scale-deficient young leaves of R. dauricum as described above. The first-strand cDNA was then synthesized from 0.5 μg of each RNA sample as described above, except that a random hexamer (Toyobo) was used as the primer. The DCA synthase gene fragment (557 bp) was amplified with the primers DCAS-RT-Fw and DCAS-RT-Rv, whereas the 18S rRNA gene fragment (GenBank accession no. AB973224.1; 663 bp) was amplified with 18S-Fw and 18S-Rv as a housekeeping gene control. The PCR products were resolved on a 2% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. Each band density from triplicate experiments was analyzed by ImageJ version 1.49 (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

Analysis of the Phytotoxic Effects of DCA and Grifolic Acid

Five-day-old BY-2 cells were incubated with 50 μm DCA, grifolic acid, or orsellinic acid for 24 h. The viability of the cells was tested by adding Trypan Blue solution (Sigma-Aldrich). Genomic DNA was isolated from treated BY-2 cells by the CTAB method (Murray and Thompson, 1980). Then, electrophoresis was performed on a 2% agarose gel.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ databases. The nucleotide sequences of RdFADOX1 to RdFADOX3, which were renamed DCA synthase, DCA synthase-like1, and DCA synthase-like2, were registered with accession numbers LC184180, LC184181, and LC184182, respectively. The transcriptome data set of R. dauricum young leaves was deposited to the DDBJ Sequence Read Archive with BioProject accession number PRJDB5618.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Amino acid sequence analyses of RdFADOX1 to RdFADOX3.

Supplemental Figure S2. Stereoselectivity of the recombinant DCA synthase reaction evaluated by a chiral HPLC analysis.

Supplemental Figure S3. SDS-PAGE and carbohydrate staining of the purified recombinant DCA synthase.

Supplemental Figure S4. Analyses of AMP released from DCA synthase by acid hydrolysis.

Supplemental Figure S5. Quantitative analysis of meroterpenoid constituents in the young leaves of R. dauricum.

Supplemental Figure S6. 1H-NMR analysis of 3-geranylgeranyl orsellinic acid.

Supplemental Figure S7. 1H-NMR analysis of diterpenodaurichromenic acid.

Supplemental Table S1. DCA synthase activity under various conditions.

Supplemental Table S2. Steady-state kinetic parameters of cannabinoid synthases.

Supplemental Table S3. Oligonucleotide primers and PCR conditions used in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Y. Niwa (Shizuoka University) for pUC18 plasmid containing the S65T-type GFP gene; H. Fujino, Y. Tatsuo, Y. Takao, and Y. Murakami, at the Experimental Station for Medicinal Plant Research of the University of Toyama, for breeding R. dauricum plants; and Dr. T. Obita (University of Toyama), T. Matsumoto (University of Toyama), and Dr. T. Matsui (Tohoku University) for helpful advice on instrumental analyses.

Glossary

- DCA

daurichromenic acid

- FPKM

fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped

- LC

liquid chromatography

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- MS

mass spectrometry

- BY-2

Bright Yellow 2

- TLC

thin-layer chromatography

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by JSPS/MEXT KAKENHI (grant nos. 15K07994 and 17H05436 to F.T) and JSPS Core-to-Core Program, B, Asia-Africa Science Platforms (F.T. is one of the recipients).

References

- Alejandro S, Lee Y, Tohge T, Sudre D, Osorio S, Park J, Bovet L, Lee Y, Geldner N, Fernie AR, et al. (2012) AtABCG29 is a monolignol transporter involved in lignin biosynthesis. Curr Biol 22: 1207–1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An G. (1987) Binary Ti vectors for plant transformation and promoter analysis. Methods Enzymol 153: 292–305 [Google Scholar]

- Ates B, Abraham L, Ercal N (2008) Antioxidant and free radical scavenging properties of N-acetylcysteine amide (NACA) and comparison with N-acetylcysteine (NAC). Free Radic Res 42: 372–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baunach M, Franke J, Hertweck C (2015) Terpenoid biosynthesis off the beaten track: unconventional cyclases and their impact on biomimetic synthesis. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 54: 2604–2626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukhari SM, Ali I, Zaidi A, Iqbal N, Noor T, Mehmood R, Chishti MS, Niaz B, Rashid U, Atif M (2015) Pharmacology and synthesis of daurichromenic acid as a potent anti-HIV agent. Acta Pol Pharm 72: 1059–1071 [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Mukwaya E, Wong MS, Zhang Y (2014) A systematic review on biological activities of prenylated flavonoids. Pharm Biol 52: 655–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombie LW, Crombie WML, Firth DF (1988) Synthesis of bibenzyl cannabinoids, hybrids of two biogenetic series found in Cannabis sativa. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1 1988: 1263–1270 [Google Scholar]

- Custers JH, Harrison SJ, Sela-Buurlage MB, van Deventer E, Lageweg W, Howe PW, van der Meijs PJ, Ponstein AS, Simons BH, Melchers LS, et al. (2004) Isolation and characterisation of a class of carbohydrate oxidases from higher plants, with a role in active defence. Plant J 39: 147–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel B, Pavkov-Keller T, Steiner B, Dordic A, Gutmann A, Nidetzky B, Sensen CW, van der Graaff E, Wallner S, Gruber K, et al. (2015) Oxidation of monolignols by members of the berberine bridge enzyme family suggests a role in plant cell wall metabolism. J Biol Chem 290: 18770–18781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desch C., Jr (1983) The Rhododendron leaf scale. J Am Rhododendron Soc 37: 78–80 [Google Scholar]

- Doss RP. (1984) Role of glandular scales of lepidote Rhododendrons in insect resistance. J Chem Ecol 10: 1787–1798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss RP, Hatheway WH, Hrutfiord BF (1986) Composition of essential oils of some lipidote Rhododendrons. Phytochemistry 25: 1637–1640 [Google Scholar]

- Dugrand-Judek A, Olry A, Hehn A, Costantino G, Ollitrault P, Froelicher Y, Bourgaud F (2015) The distribution of coumarins and furanocoumarins in Citrus species closely matches Citrus phylogeny and reflects the organization of biosynthetic pathways. PLoS ONE 10: e0142757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian J. (1965) Simple method of anaerobic cultivation, with removal of oxygen by a buffered glucose oxidase-catalase system. J Bacteriol 89: 921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox JL. (1974) Sodium dithionite reduction of flavin. FEBS Lett 39: 53–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaweska HM, Roberts KM, Fitzpatrick PF (2012) Isotope effects suggest a stepwise mechanism for berberine bridge enzyme. Biochemistry 51: 7342–7347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesell A, Chávez ML, Kramell R, Piotrowski M, Macheroux P, Kutchan TM (2011) Heterologous expression of two FAD-dependent oxidases with (S)-tetrahydroprotoberberine oxidase activity from Argemone mexicana and Berberis wilsoniae in insect cells. Planta 233: 1185–1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagel JM, Beaudoin GA, Fossati E, Ekins A, Martin VJ, Facchini PJ (2012) Characterization of a flavoprotein oxidase from opium poppy catalyzing the final steps in sanguinarine and papaverine biosynthesis. J Biol Chem 287: 42972–42983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton R, Watanabe CK, de Boer HA (1987) Compilation and comparison of the sequence context around the AUG startcodons in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 15: 3581–3593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, Quang DN, Nukada M, Asakawa Y (2005) Isolation, synthesis and biological activity of grifolic acid derivatives from the inedible mushroom Albatrellus dispansus. Heterocycles 65: 2431–2439 [Google Scholar]

- Huang CH, Lai WL, Lee MH, Chen CJ, Vasella A, Tsai YC, Liaw SH (2005) Crystal structure of glucooligosaccharide oxidase from Acremonium strictum: a novel flavinylation of 6-S-cysteinyl, 8α-N1-histidyl FAD. J Biol Chem 280: 38831–38838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata N, Wang N, Yao X, Kitanaka S (2004) Structures and histamine release inhibitory effects of prenylated orcinol derivatives from Rhododendron dauricum. J Nat Prod 67: 1106–1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]