Abstract

Introduction/Objective

Adults aged 65 or older with arthritis may be at increased risk for cognitive impairment [cognitive impairment not dementia (CIND) or dementia]. Studies have found associations between arthritis and cognition impairments, however, none have examined whether persons with arthritis develop cognitive impairments at higher rates than those without arthritis.

Methods

Using data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) we estimated the prevalence of cognitive impairments in older adults with and without arthritis and examined associations between arthritis status and cognitive impairments. We calculated incidence density ratios (IDRs) using generalized estimating equations (GEE) to estimate associations between arthritis and cognitive impairments adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, income, depression, obesity, smoking, chronic conditions, physical activity, and birth cohort.

Results

The prevalence of CIND and dementia did not significantly differ between those with and without arthritis (CIND: 20.8%, 95% CI 19.7 – 21.9 vs. 18.3%, 95% CI 16.8 – 19.8; dementia: 5.2% 95% CI 4.6 – 5.8 vs. 5.1% 95% CI 4.3 – 5.9). After controlling for covariates, older adults with arthritis did not differ significantly from those without arthritis for either cognitive outcome (CIND IDR: 1.6, 95% CI = 0.9 – 2.9; dementia IDR: 1.1, 95% CI = 0.4 – 3.3) and developed cognitive impairments at a similar rate to those without arthritis.

Conclusion

Older adults with arthritis were not significantly more at risk to develop cognitive impairments and developed cognitive impairments at a similar rate as older adults without arthritis over six years.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Aging, Dementia, cognitive impairment not dementia

INTRODUCTION

About half of older adults (≥65 years) have some form of arthritis [1], such as rheumatoid arthritis, gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia, and arthritis is a leading cause of disability in U.S. adults [2]. While arthritis is known for its debilitating effect on the musculoskeletal system, some types of arthritis affect other body systems [3]. Cognitive impairment is also common in older adults. In 2010 an estimated 18% of individuals aged 75 to 84 years old and 32% of individuals over the age of 85 had Alzheimer disease dementia [4], while 22% of those 71 years old or older had milder forms of cognitive impairment not dementia (CIND) [5].

Prior studies that have examined associations between arthritis and cognition suggest that arthritis may increase the risk for cognitive impairment [6–10]. In one small cross-sectional study, 30% of people with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) had cognitive impairment compared to 7.5% of people without RA [6]. A second small study of 115 people with RA found approximately 30% had cognitive impairment [10]. In a larger longitudinal study (n = 1,449), persons with any joint disorder, but particularly RA, had twice the odds of reporting worse cognitive status later in life than those without a joint disorder [8]. A matched nested case-control study within a retrospective cohort reported a 25% increase in the incidence of dementia among patients with osteoarthritis than among those without osteoarthritis [7]. However, another study with the same design and database found no difference in the incidence of dementia in people with autoimmune rheumatic diseases compared with those without such diseases [9].

A plausible biological mechanism connecting arthritis and cognitive impairment is inflammation [11, 12]. Inflammation is common in arthritis. Even osteoarthritis, considered a disorder of the hyaline cartilage, is currently viewed as having inflammatory components [13]. However, cognitive impairments in people with arthritis may actually result from the sequelae of arthritis, rather than the inflammation itself. Cognitive impairment has been associated with pain [14], fatigue [15], depression [16] and reduced physical activity [17], all important symptoms of arthritis.

The purpose of this study was to describe the prevalence of cognitive impairments in older adults with arthritis and to examine the cross-sectional association between arthritis and cognitive impairment among older adults after controlling for potential covariates. A secondary purpose was to determine if older adults with arthritis developed cognitive impairments at a different rate compared with older adults without arthritis. We reasoned that those with arthritis would show cognitive impairment before those without arthritis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

The Health and Retirement Study (HRS), started in 1992, is a nationally representative longitudinal panel study of U.S. adults over the age of 50 that examines the aging process. As a steady-state study, it adds a new cohort of 51 to 56 year olds every 6 years (for a total of 5 cohorts by 2010) and obtains data every 2 years. The HRS has been approved by the University of Michigan Health Sciences Human Subjects Committee. We analyzed data on adults aged 65 and older from the 2004 cohort through the 2010 cohort (3 waves / 6 years) using the RAND Corporation HRS Data File (v. N), which provides self-reported individual variables, as well as summarized scores from all HRS waves. A total of 20,129 participants in 2004 provided data for the HRS (overall response rate of 87.6% [18]).

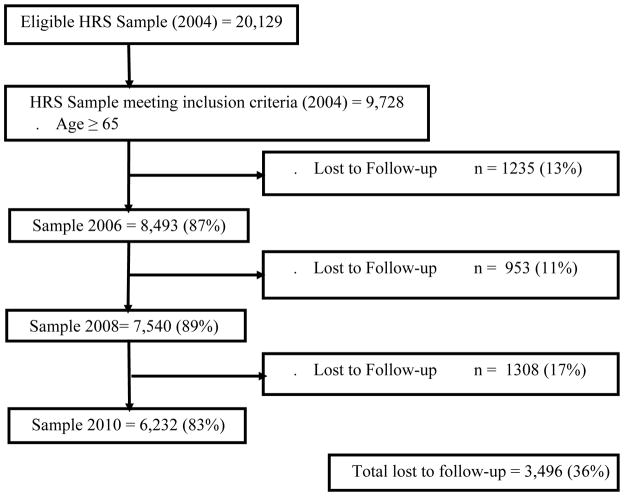

Those 65 or older in 2004 were eligible for our study; 9,728 (49%) met this criterion. Response rates for these participants for the 2006 to 2010 waves were between 83% and 89% (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart from the complete, eligible Health and Retirement Study 2004 sample to our analytic sample of people aged 65 or older.

Lost to Follow-up: Died, non-respondent, or proxy report

Arthritis Exposure

We identified cases of any type of arthritis with the question: “Have you ever had, or has a doctor ever told you that you have arthritis or rheumatism?” A case definition based on a similar question has been shown to have moderate specificity [19].

Outcomes

We determined cognitive impairment status using definitions described by Crimmins et al.[20]. This method included four items for cognitive functioning: a 10-word immediate recall test for short-term memory (scored 0–10); a delayed recall test for long-term memory (scored 0–10); the serial 7’s subtraction test to assess working memory (scored 0–5); and counting backwards from 20 to assess attention and processing speed (scored 0–2). Participants were allowed 5 trials for the serial 7’s task, and the backward counting was scored as correct/incorrect. Thus, the total cognitive functioning score could range from 0 to 27. Participants with scores from 0–6 were classified as having dementia, 7–11 as having CIND, and 12–27 as having no cognitive impairment [20]. This method of ascertainment has moderate specificity [21].

Covariates

Demographic covariates were self-reported age, sex, race/ethnicity, and marital status. Race/ethnicity was non-Hispanic white, Non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and Non-Hispanic others to protect respondent confidentiality. Marital status was “married/partnered” and “not married/partnered”. Socioeconomic covariates were self-reported education (“less than college degree” and “college and greater”) and income (from the RAND Corporation imputed household income score, coded approximately in thirds [$0 to $19,999; $20,000 to $39,999, $40,000 or greater]). Medical characteristic covariates were Body Mass Index (BMI) (kg/m2) (dichotomized using standard cutoffs of not obese <30 kg/m2 and obese ≥ 30 kg/m2), the number of 6 chronic conditions (from doctor-diagnosed conditions: high blood pressure, diabetes, cancer, lung disease, heart condition or stroke, categorized as “none”, “1”, or “2 or more”), and smoking status (never, previous, current). Depression was assessed using a subset of items from the short version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [22] (categorized as no depression or depression [cutoff of 4 or higher]). Physical activity was based on responses to questions about physical activity at each of three intensities: 1) vigorous (defined as activities, such as running or jogging, swimming, cycling, aerobics or gym workout, tennis, or digging with a spade or shovel), 2) moderately energetic (defined as activities such as, gardening, cleaning the car, walking at a moderate pace, dancing, floor or stretching exercises), or 3) mildly energetic (defined as activities such as vacuuming, laundry, or home repairs). Although not an official response, many participants volunteered “every day”, so that there were five frequency categories. Participants who engaged in any intensity physical activity “every day” or “more than once a week,” were considered active; “once a week” or “one to three times a month,” somewhat active; and “hardly ever or never,” inactive.

Statistical Analysis

We accounted for the complex sample design by including the study design variables (strata and sampling units) [23] and baseline weights in all analyses.

We compared characteristics at baseline between those with and without arthritis for each type of cognitive impairment status (no cognitive impairment, CIND, and dementia). We calculated weighted proportions and 95% confidence intervals (CI) using SAS (v. 9.3 [24]. We conservatively defined statistical significance (p ≤ 0.01) in the characteristics using non-overlapping CIs [25].

To examine associations between arthritis and CIND/dementia, after controlling for potential covariates, we calculated incidence density ratios (IDRs) and 95% CI using three modified Poisson regression models (i.e. models with robust variance estimators to account for variance overestimation due to model-misspecification) with generalized estimating equations (GEE) using SUDAAN (v. 11 [26]). Because participants reported outcomes multiple times over a six-year follow-up, we used exchangeable correlation matrices to account for correlations among these repeated measures. We computed standard errors with the Taylor Series Linearization Method (with-replacement sampling) to account for complex sample designs. Participants who died, refused to respond, or were lost to follow-up were included in the study until their last follow-up. All non-missing pairs of data were used to estimate parameters in the correlation matrix [27, 28].

All models were adjusted for age, sex, marital status, education, obesity, smoking, chronic conditions, physical activity, and depression. We also adjusted for birth cohort because it is independently associated with cognitive impairment [29]. Except for sex, education, race/ethnicity, and birth cohort, the other covariates were analyzed for changes over follow-up as time-dependent covariates (interaction between age and each covariate).

To determine if older adults with arthritis developed cognitive impairments at different rates as they aged compared with older adults without arthritis, we calculated the interactions between age and arthritis. We also controlled for interactions between age and all the other independent variables. A significant interaction effect would suggest that the two groups changed at different rates over time.

RESULTS

Of the 9,728 participants, 6,610 (67.9%) reported arthritis. For participants with CIND, a significantly higher percentage of participants with arthritis than those without arthritis were female, in the lowest income bracket, obese, had two or more chronic conditions, and were depressed (Table 1). For participants with dementia, a significantly higher percent of those with arthritis than those without arthritis were female, had two or more chronic conditions, and were depressed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of 2004 baseline characteristics of adults ≥65 cognitive impairment no dementia (CIND) (n = 2,032) and dementia (n = 558) in the Health and Retirement Study, by arthritis status

| Without Arthritis | With Arthritis | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| CIND | Dementia | CIND | Dementia | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| n | % | 95% CL | n | % | 95% CL | n | % | 95% CL | n | % | 95% CL | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| DEMOGRAPHICS | ||||||||||||

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 65–69 | 138 | 19.1 | (15.9, 22.4) | 25 | 10.5 | *(6.0, 15) | 336 | 18.4 | (16.4, 20.4) | 60 | 10.6 | (7.7, 13.5) |

| 70–74 | 139 | 25.3 | (21.2, 29.4) | 33 | 17.4 | (11.4, 23.4) | 278 | 19.2 | (16.9, 21.5) | 55 | 12.8 | (9.2, 16.4) |

| 75 or greater | 308 | 55.5 | (51.1, 60.0) | 116 | 72.1 | (65.0, 79.1) | 833 | 62.4 | (59.7, 65.1) | 269 | 76.6 | (72.2, 81) |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 315 | 52.9 | (48.4, 57.4) | 88 | 47.1 | (38.8, 55.3) | 525 | 36.1 | (33.3, 38.8) | 132 | 32.5 | (27.3, 37.7) |

| Female | 270 | 47.1 | (42.6, 51.6) | 86 | 52.9 | (44.7, 61.2) | 922 | 63.9 | (61.2, 66.7) | 252 | 67.5 | (62.3, 72.7) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| non-Hispanic white | 371 | 72.7 | (69.0, 76.4) | 92 | 63.0 | (55.4, 70.6) | 910 | 72.1 | (69.8, 74.5) | 193 | 62.9 | (57.7, 68.2) |

| Hispanic | 75 | 10.2 | (7.8, 12.6) | 29 | 13.5 | (8.4, 18.7) | 191 | 10.6 | (9.1, 12.2) | 53 | 11.0 | (7.9, 14) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 122 | 14.1 | (11.3, 16.8) | 50 | 21.3 | (15.2, 27.4) | 320 | 15.0 | (13.2, 16.7) | 127 | 22.8 | (18.5, 27.1) |

| non-Hispanic other | 17 | 3.0 | *(1.5, 4.6) | 3 | --- | --- | 26 | 2.3 | *(1.3, 3.2) | 11 | --- | --- |

| Marital Status | ||||||||||||

| Not married/partnered | 264 | 47.9 | (43.4, 52.4) | 85 | 49.4 | (41.1, 57.8) | 727 | 52.2 | (49.3, 55.0) | 220 | 57.6 | (51.8, 63.3) |

| Married/partnered | 320 | 52.1 | (47.6, 56.6) | 88 | 50.6 | (42.2, 58.9) | 720 | 47.8 | (45.0, 50.7) | 164 | 42.4 | (36.7, 48.2) |

| SOCIOECONOMIC | ||||||||||||

| Education | ||||||||||||

| Less than college | 541 | 91.7 | (89.0, 94.4) | 162 | 92.3 | (87.8, 96.9) | 1357 | 93.3 | (91.8, 94.7) | 368 | 95.3 | (92.9, 97.6) |

| College or greater | 44 | 8.3 | (5.6, 11.0) | 12 | --- | --- | 90 | 6.7 | (5.3, 8.2) | 16 | 4.7 | *(2.4, 7.1) |

| Income | ||||||||||||

| $0 to $19,999 | 268 | 44.4 | (39.9, 48.8) | 111 | 61.7 | (53.6, 69.8) | 792 | 54.1 | (51.3, 57.0) | 257 | 65.3 | (59.9, 70.8) |

| $20,000 to $39,999 | 197 | 33.5 | (29.3, 37.8) | 43 | 25.2 | (18.0, 32.5) | 425 | 30.1 | (27.4, 32.7) | 86 | 24.1 | (19.1, 29.0) |

| $40,000 or greater | 120 | 22.1 | (18.3, 25.9) | 20 | 13.1 | *(7.4, 18.8) | 230 | 15.8 | (13.7, 17.9) | 41 | 10.6 | (7.2, 14.1) |

| MEDICAL CHARACTERISTICS | ||||||||||||

| Obesity | ||||||||||||

| No | 268 | 73.8 | (68.8, 78.7) | 81 | 83.0 | (75.4, 90.5) | 545 | 63.5 | (60.1, 66.9) | 157 | 65.0 | (57.7, 72.3) |

| Yes | 103 | 26.2 | (21.3, 31.2) | 21 | 17.0 | *(9.5, 24.6) | 360 | 36.5 | (33.1, 39.9) | 78 | 35.0 | (27.7, 42.3) |

| Number of 6 Chronic Conditions | ||||||||||||

| 0 conditions | 142 | 24.4 | (20.5, 28.2) | 35 | 20.3 | (13.6, 27.0) | 188 | 13.8 | (11.8, 15.8) | 45 | 13.9 | (9.8, 18.1) |

| 1 condition | 202 | 33.7 | (29.5, 37.9) | 72 | 42.0 | (33.8, 50.3) | 448 | 30.9 | (28.2, 33.5) | 98 | 23.8 | (19.1, 28.5) |

| 2 or more conditions | 232 | 41.9 | (37.4, 46.5) | 65 | 37.6 | (29.6, 45.7) | 796 | 55.4 | (52.5, 58.2) | 233 | 62.3 | (56.7, 67.8) |

| Smoking | ||||||||||||

| Never smoked | 222 | 37.8 | (33.4, 42.1) | 79 | 48.2 | (40.0, 56.5) | 636 | 43.8 | (41.0, 46.7) | 171 | 45.6 | (39.8, 51.4) |

| Previous smoker | 284 | 49.3 | (44.8, 53.8) | 83 | 45.6 | (37.4, 53.8) | 675 | 47.3 | (44.5, 50.2) | 180 | 47.7 | (42, 53.5) |

| Current smoker | 76 | 12.9 | (9.9, 15.9) | 12 | --- | --- | 125 | 8.8 | (7.2, 10.5) | 28 | 6.7 | *(3.9, 9.4) |

| OTHER FACTORS | ||||||||||||

| Depression | ||||||||||||

| Not depressed | 510 | 87.8 | (84.9, 90.7) | 140 | 79.3 | (72.5, 86.2) | 1060 | 73.7 | (71.2, 76.2) | 247 | 64.4 | (58.8, 69.9) |

| Depressed | 75 | 12.2 | (9.3, 15.1) | 34 | 20.7 | (13.8, 27.5) | 384 | 26.3 | (23.8, 28.8) | 133 | 35.6 | (30.1, 41.2) |

| Physical Activity | ||||||||||||

| Inactive | 101 | 16.9 | (13.6, 20.3) | 48 | 24.8 | (17.9, 31.6) | 301 | 20.2 | (17.9, 22.4) | 142 | 36.9 | (31.3, 42.5) |

| Somewhat Active | 191 | 33.5 | (29.2, 37.8) | 55 | 29.9 | (22.5, 37.3) | 506 | 35.8 | (33.0, 38.5) | 115 | 29.5 | (24.3, 34.7) |

| Active | 293 | 49.6 | (45.1, 54.1) | 71 | 45.3 | (37.0, 53.6) | 638 | 44.1 | (41.2, 46.9) | 127 | 33.6 | (28.2, 38.9) |

Relative standard error (RSE) is between .20 and .29 indicating a high sampling error, results should be used with caution; --- RSE is ≥.30

CIND crude prevalence for those with arthritis (20.8%, 95% CI 19.7, 21.9) did not differ significantly from those without arthritis (18.3%, 95% CI 16.8, 19.8), and the association between CIND and arthritis after adjusting for covariates was not significant (CIND IDR: 1.6, 95% CI = 0.9, 2.9) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations between arthritis, demographic characteristics, socioeconomic characteristics, comorbidities, and sequelae of arthritis with cognitive impairment, no dementia (CIND) and dementia, Health and Retirement Study

| CIND | Dementia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDR | 95% CL | IDR | 95% CL | |

| ARTHRITIS (ref: No Arthritis) | ||||

| Arthritis | 1.6 | (0.9, 2.9) | 1.1 | (0.4, 3.3) |

| DEMOGRAPHICS | ||||

| Sex (ref: Male) | ||||

| Female | 0.3 | (0.1, 0.5) | 0.6 | (0.2, 1.8) |

| Race (ref: Non-Hispanic white) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 14.6 | (7.8, 27.3) | 25.4 | (9.0, 71.5) |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 4.6 | *(0.6, 34.2) | 5.7 | *(0.2, 146.8) |

| Hispanic | 11.2 | (4.8, 26.0) | 8.3 | (2.0, 33.7) |

| Marital Status (ref: Not married/partnered) | ||||

| Married/Partnered | 0.8 | (0.4, 1.5) | 0.4 | (0.1, 1.2) |

| SOCIOECONOMIC | ||||

| Education (ref: College or greater) | ||||

| Less than College | 56.5 | (20.0, 159.8) | 7.5 | *(0.6, 96.5) |

| Income (ref: $40,000+) | ||||

| $0 to $19,999 | 10.9 | (4.8, 24.8) | 45.2 | (7.4, 274.6) |

| $20,000 to $39,999 | 4.1 | (1.8, 9.1) | 12.8 | (2.1, 79.6) |

| MEDICAL CHARACTERISTICS | ||||

| Obesity (ref: Not obese) | ||||

| Obese | 1.4 | (0.7, 2.5) | 1.3 | (0.5, 3.6) |

| Smoking (ref: Never smoked) | ||||

| Previous smoker | 1.1 | (0.6, 2.0) | 1.8 | (0.6, 5.2) |

| Current smoker | 1.1 | (0.4, 3.0) | 0.1 | *(0.01, 0.5) |

| Number of Chronic Conditions (ref: 0 conditions) | ||||

| 1 condition | 0.9 | (0.4, 1.8) | 0.9 | (0.3, 2.7) |

| 2 or more conditions | 1.4 | (0.7, 2.7) | 4.3 | (1.4, 12.9) |

| OTHER FACTORS | ||||

| Depression (ref: not depressed) | ||||

| Depressed | 2.7 | (1.6, 4.4) | 6.5 | (3.0, 14.1) |

| Physical Activity (ref: Active) | ||||

| Inactive | 2.2 | (1.3, 3.8) | 10.3 | (4.2, 25.1) |

| Somewhat Active | 1.2 | (0.8, 1.9) | 2.2 | (1.1, 4.6) |

IDR: Incidence Density Ratio; 95% CI: 95% Confidence Interval; ref: reference standard;

potentially unstable estimate as there is the potential for high sampling error due to small sample size

Dementia crude prevalence also did not differ significantly between those with arthritis (5.2% 95% CI 4.6, 5.8) and those without arthritis (5.1% 95% CI 4.3, 5.9), and the association between dementia and arthritis after adjusting for covariates was not significant (dementia IDR: 1.1, 95% CI = 0.4, 3.3) (Table 2).

The interaction terms between arthritis and age in the CIND or dementia models were not significant (p > .01), indicating that the rate of development of cognitive impairment in older adults with arthritis resembled that in those without arthritis.

Although arthritis was not significantly associated with cognitive impairment in our models, several covariates were significantly associated with cognitive impairment. Characteristics associated with CIND were being male, being either non-Hispanic black or Hispanic, having less than a college education, having an income <$40,000, being depressed, and being inactive (Table 4). Characteristics specific to dementia resembled those for CIND, except that being a male and having less than a college education were not significantly associated with dementia, while having 2 or more chronic conditions, never being a smoker, and being somewhat inactive were associated with dementia. Of note is the large size of the association between those with CIND and those with less than a college education (IDR: 56.5, 95% CI 20.0, 159.8) and for between those with dementia and non-Hispanic blacks (IDR: 25.4, 95% CI 9.0, 71.5), those with incomes <$20,000 (IDR: 45.2 95% CI 7.4, 274.6), and those with incomes from $20,000 to $39,999 (IDR: 12.8 95% CI 2.1, 79.6).

DISCUSSION

Despite previous research that reported more cognitive impairment in people with arthritis, we found similar percentages of CIND and dementia among older adults with and without arthritis over a 6-year period. We also found that older adults with arthritis developed CIND or dementia at the same rate as those without arthritis, suggesting that arthritis does not accelerate the development of cognitive impairment.

One reason that our study’s results differed from previous studies is our sample selection. Ours is the first study to sample from a large representative sample of typically aging adults, while previous studies have generally used samples from registries [8], patients in rheumatology clinics [6], arthritis-based cohort studies [10], or insurance records [7]. Information obtained from these sources may suffer from selection bias, and not represent the true population but a group that has severe rather than mild disease. Samples from these sources may also receive differential care and more attention than the general population. The proposed mechanism for increased cognitive impairment in those with arthritis is inflammation. Those who indicated arthritis in our sample probably had a broad spectrum of both arthritis and inflammation from very mild to very severe. This varying degree of inflammation may have reduced the ability to detect a relationship between less severe arthritis and cognitive impairment. Future studies will need to examine specific types of arthritis to define how inflammation and the varying treatments that different types of arthritis receive relate to cognitive impairments

Another and perhaps more important reason for the differences in results from our study were our evaluation of variables closely associated with both arthritis and cognitive impairment. Factors such as pain, fatigue, depression, or reduced physical activity may be associated with both arthritis and cognitive impairment. In our study, decreased physical activity and depression were strongly associated with CIND or dementia. Although other studies adjusted for demographics and comorbidities such as diabetes and COPD, only one study [10] adjusted for depression and none for physical activity. Thus, studies that reported associations between cognitive impairment and arthritis may have been affected by sequelae associated with arthritis.

This study has multiple strengths. Its representativeness enhances its generalizability. Its sample size allowed sufficient statistical power to examine multiple associations. Its inclusion of relevant covariates allowed for their adjustment. The exclusion of persons with baseline cognitive impairment and the subsequent six-year follow-up allowed comparison of rates of the development of cognitive impairment. Finally, the use of GEE analytic techniques reduces the effects of missing data and accounts for repeated measures [27, 28].

This study has several limitations. First, it did not use objective tests, such as a physician’s diagnosis or neurocognitive testing to determine arthritis status or cognitive status. Our ascertainment of arthritis using self-report has only moderate specificity (range from 58.8%; to 70.6% [19]) and our method of ascertainment of dementia and CIND has a specificity of 76% [21]. Thus, this study will have misclassified cases of arthritis and cognitive impairment, although the prevalence of cognitive impairment resembled that of other studies [6, 10]. Second, we did not differentiate between types of arthritis which have varying degrees of inflammation, and also varying treatments. It is possible that different types of arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis, may have a stronger connection with cognitive impairments. Third this study excluded study participants who required proxies to provide answers, though including proxies did not significantly affect the results. Fourth, the overall loss to follow-up was 36%. Fifth, the method of identifying physical activity levels was not robust and has not been validated. Sixth, weighting the sample using respondent sampling weights from the entry year does not correct for attrition, which may underestimate later prevalence estimates. Seventh, the small sample sizes coupled with the potential for sampling error for those in subgroups of non-Hispanic Others, those with less than a college education, and current smokers indicate that findings for these subgroups should be viewed cautiously.

In conclusion, after adjustment for potential confounding variables, arthritis was not significantly associated with CIND or dementia among older adults from the general population. Moreover, the rate of cognitive decline over the six-year follow-up was similar for those with and without arthritis, suggesting that arthritis does not accelerate the development of cognitive impairment in a cohort of typically aging adults.

Acknowledgments

This research was performed by Dr. Nancy Baker under an appointment to the Research Participation program at the CDC, administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education and as a Visiting Scholar through The Center for Rehabilitation Research using Large Datasets at the University of Texas Medical Branch (funded by the National Institutes of Health - National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [grant # R24-HD065702]). The Health and Retirement Study (HRS) is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) and is conducted by the University of Michigan.

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Kristina Theis, from Arthritis Program, Division of Population Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta GA, who was instrumental in developing conceptual elements for this paper.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Barbour KE, Helmick CG, Theis K, Murphy LP, Hootman JM, Brady TJ. Prevalence of doctor-diagnosed arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation - United States, 2010–2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013;62:869–873. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brault MW, Hootman JM, Helmick CG, Theis K. Prevalence and most common causes of disability among adults --- United States, 2005. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2009;58:421–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young A, Koduri G. Extra-articular manifestations and complications of rheumatoid arthritis. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2007;21:907–927. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2007.05.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology. 2013;80:1778–1783. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828726f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, Heeringa SG, Weir DR, Ofstedal MB, Burke JR, Hurd MD, Potter GG, Rodgers WL, et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment without dementia in the United States. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;148:427–434. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-6-200803180-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Appenzeller S, Bértolo MB, Costallat LTL. Cognitive impairment in rheumatoid arthritis. Methods and Findings in Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology. 2004;26:339–343. doi: 10.1358/mf.2004.26.5.831324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang SW, Wang WT, Chou LC, Liao CD, Liou TH, Lin HW. Osteoarthritis increases the risk of dementia: A nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. Scientific Reports. 2015;5:10145. doi: 10.1038/srep10145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallin K, Solomon A, Kareholt I, Tuomilehto J, Soininen H, Kivipelto M. Midlife rheumatoid arthritis increases the risk of cognitive impairment two decades later: A population-based study. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2012;31:669–676. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-111736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu K, Wang H-K, Yeh C-C, Huang C-Y, Sung P-S, Wang L-C, Muo C-H, Sung F-C, Chen H-J, Li Y-C, et al. Association between autoimmune rheumatic diseases and the risk of dementia. BioMed Research International. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/861812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shin SY, Katz P, Wallhagen M, Julian L. Cognitive impairment in persons with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care & Research. 2012;64:1144–1150. doi: 10.1002/acr.21683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunningham C, Hennessy E. Co-morbidity and systemic inflammation as drivers of cognitive decline: new experimental models adopting a broader paradigm in dementia research. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy. 2015;7:33. doi: 10.1186/s13195-015-0117-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Troller J, Agars E. Systemic inflammation and cognition in the elderly. In: Miyoshi Koho, Morimura Yasushi, Maeda Kiyoshi., editors. Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Springer; 2010. pp. 177–197. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McAlindon TE. Editorial: Toward a New Paradigm of Knee Osteoarthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatology. 2015;67:1987–1989. doi: 10.1002/art.39177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berryman C, Stanton TR, Bowering KJ, Tabor A, McFarlane A, Moseley GL. Do people with chronic pain have impaired executive function? A meta-analytical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34:563–579. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nikolaus S, Bode C, Taal E, van de Laar MAFJ. Fatigue and factors related to fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review. Arthritis Care & Research. 2013;65:1128–1146. doi: 10.1002/acr.21949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rock PL, Roiser JP, Riedel WJ, Blackwell AD. Cognitive impairment in depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine. 2014;44:2029–2040. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sofi F, Valecchi D, Bacci D, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A, Macchi C. Physical activity and risk of cognitive decline: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2011;269:107–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sample sizes and response rates. [ http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/sampleresponse.pdf]

- 19.Sacks J, Harold L, Helmick CG, Gurwitz J, Emani S, Yood R. Validation of a surveillance case definition for arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:340–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crimmins EM, Kim JK, Langa KM, Weir DR. Assessment of Cognition Using Surveys and Neuropsychological Assessment: The Health and Retirement Study and the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2011;66B:i162–i171. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langa KM, Larson EB, Crimmins EM, et al. A comparison of the prevalence of dementia in the united states in 2000 and 2012. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2017;177:51–58. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steffick DE. Documentation of affective functioning measures in the Health and Retirement Study. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center, University of Michigan; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Technical description of the Health and Retirement Survey sample design. [ http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/index.php?p=userg&jumpfrom=HS]

- 24.SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT 9.3 User’s guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cumming G. Inference by eye: Reading the overlap of independent confidence intervals. Statistics in Medicine. 2009;28:205–220. doi: 10.1002/sim.3471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN language manual, Vols 1 and 2, Release 11. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeger SL, Liang K-Y, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: A generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:1049–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dodge HH, Zhu J, Lee CW, Chang CCH, Ganguli M. Cohort effects in age-associated cognitive trajectories. Journals of Gerontology - Series A Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2014;69:687–694. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]