Abstract

Background

Although it is likely that childbearing among women with disabilities is increasing, no empirical data have been published on changes over time in the numbers of women with disabilities giving birth. Further, while it is known that women with disabilities are at increased risk of cesarean delivery, temporal trends in cesarean deliveries among women with disabilities have not been examined.

Objective

To assess time trends in births by any mode and in primary cesarean deliveries among women with physical, sensory, or intellectual/developmental disabilities.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using linked vital records and hospital discharge data from all deliveries in California, 2000–2010 (n=4,605,061). We identified women with potential disabilities using ICD-9 codes. We used descriptive statistics and visualizations to examine time patterns. Logistic regression analyses assessed the association between disability and primary cesarean delivery, stratified by year.

Results

Among all women giving birth, the proportion with a disability increased from 0.27% in 2000 to 0.80% in 2010. Women with disabilities had significantly elevated odds of primary cesarean delivery in each year, but the magnitude of the odds ratio decreased over time from 2.60 (95% CI=2.25=2.99) in 2000 to 1.66 (95% CI=1.51–1.81) in 2010.

Conclusions

Adequate clinician training is needed to address the perinatal care needs of the increasing numbers of women with disabilities giving birth. Continued efforts to understand cesarean delivery patterns and reasons for cesarean deliveries may help guide further reductions in proportions of cesarean deliveries among women with disabilities relative to women without disabilities.

Keywords: Birth, Cesarean, Hospital discharge data, People with disabilities, Time trends

Introduction

As medical advances have facilitated longer lifespans and more active lives for women with disabilities, interest in childbearing in this population has increased [1, 2]. While women with disabilities still constitute a small proportion of women giving birth [3, 4], that proportion may be growing. However, no empirical data have been published on changes over time in the numbers of women with disabilities giving birth.

Time trends in mode of delivery are also of interest. Incidence of cesarean delivery in the general population increased dramatically from the mid-1990s through 2009 before leveling off and then beginning to decline in 2013 [5, 6] In 2010, nearly one third of births in the U.S. were cesarean deliveries [7]. The overall increase in cesarean deliveries was driven by a sharp reduction in the proportion of women delivering vaginally after a prior cesarean delivery, combined with an increase in primary cesareans (those occurring in women with no prior history of cesarean delivery)[7]. There are certain situations (e.g. placenta previa; cord prolapse) when a cesarean delivery is clearly indicated as a life-saving procedure [8, 9]. However, there are also more subjective indications (e.g. non-reassuring fetal status, failed progress in labor), in which clinician judgment plays a substantial role in determining whether to proceed with labor or conduct a cesarean [8, 10, 11].

Subjective indications appear to have contributed substantially to the increase in primary cesarean deliveries, perhaps in response to fears of litigation if adverse outcomes occurred in the absence of intervention [8, 12] One might expect such concerns to be associated with a particularly strong increase in cesarean deliveries among women with disabilities, whose pregnancies may be viewed by clinicians as especially high risk [13]. As yet though, temporal trends in cesarean deliveries among women with disabilities have not been examined.

The purpose of the present study was to assess time trends in births by any mode and in primary cesarean deliveries among women with physical, sensory, or intellectual/developmental disabilities during the 2000–2010 decade. We hypothesized that: 1) the proportion of women with disabilities among all women giving birth would increase over time; and 2) between 2000 and 2009, the proportion of deliveries by cesarean (among women with no previous cesareans) would increase more sharply among women with disabilities than among those without.

Methods

Our study utilized a retrospective cohort design. The data source consisted of linked hospital discharge and vital records (birth certificates and death files) for all births in the state of California between 2000 and 2010. The dataset contains de-identified data for mother and neonate pairs drawn from the maternal and neonatal hospital discharge record and the birth certificate. The study was approved by the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, and the Institutional Review Board of Oregon Health & Science University.

The dataset included a total of 5,772,198 delivery records. We excluded multiple gestations and breech presentations (n=332,719), identified using either the birth certificate checkboxes or International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, clinical modification (ICD-9) codes in the discharge file. Records with previable gestational ages (< 23 weeks gestation [14, 15]) were also excluded (n=6,946). Our resulting analytic sample size was 5,432,533 for examination of time trends in births (by any mode) to women with disabilities. Because a previous cesarean delivery is strongly associated with subsequent cesarean, our analysis of time trends in primary cesarean deliveries excluded 827,472 women with prior cesarean deliveries, yielding a sample size of 4,605,061.

Our dependent variable was primary cesarean delivery, documented either on the birth certificate or by an ICD-9 diagnosis or procedure code in the discharge file. We excluded women with previous cesarean deliveries because prior cesarean is strongly associated with subsequent cesarean delivery. In accordance with literature on the validity of birth certificate versus hospital discharge data [16–19], we privileged the discharge record whenever possible.

We identified disability status and type using ICD-9 diagnosis and procedure codes from the patient discharge data file. Our dataset was limited to diagnoses coded at or near the time of delivery; we did not have access to women’s full medical records. Therefore, we erred on the side of inclusivity in deciding what codes to categorize as “disability”, incorporating some milder conditions that we assumed must have been deemed salient if they were coded in the delivery discharge file. Appendix A contains a full list of ICD-9 codes included in our disability definition, along with sample frequencies. The list is divided into broad disability subgroups: physical, hearing, vision, and intellectual/developmental (IDD) disabilities. An individual woman could be in more than one group if she had multiple disability codes recorded on her discharge record. We also created a binary indictor of presence of any of our target disability types versus none.

Our disability algorithm was adapted from sets of codes used in prior research for identifying people with disability or risk of disability. Khoury et al. [20] worked with a disability epidemiologist and a physician to create a list of conditions associated with mobility disability. In consultation with clinicians and disability researchers, we modified the list by removing codes for acute injuries that may not have lasting impact (e.g. fracture of the spinal column without spinal cord injury) and adding several other diagnoses (e.g. late effects of polio; spinal muscular atrophy; epilepsy; cystic fibrosis; limb amputation) that may be associated with some level of physical disability, although not necessarily a mobility restriction. The addition of these diagnoses was intended to capture a broad range of conditions that may impact physical functioning. We erred on the side of inclusivity to increase generalizability and due to the fact that our data come from the delivery record and not from women’s full medical records. Diagnosis codes present in the delivery record may disproportionately reflect the most serious disabilities (obvious enough to be noted at time of delivery), thereby skewing the relationship between disability and cesarean delivery. To help counteract that bias, we included milder conditions as well, if coded. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis in which the physical disability category did not include the codes we had added to the list from Khoury, et al. [20] and we instead analyzed them in an “other conditions” category (see Appendix B).

We drew our initial list of hearing disability codes from Mann et al. [21], to which we added “other specified forms of hearing loss”, “congenital anomalies of ear causing impairment of hearing”, and “Deaf, nonspeaking, not elsewhere classifiable”. Javitt and colleagues [22] categorized vision loss codes by severity and tested their classification in relation to Medicare costs associated with vision care. We used all codes associated with moderate and severe vision loss and blindness, and added codes for vision conditions that often lead to vison loss (e.g. macular degeneration and other retinal disorders). For IDD, we used the list of codes generated by Lin et al. [23] -- with input from clinicians and policy makers -- to identify this population in a manner consistent with criteria for service eligibility.

The following pregnancy-related covariates were drawn from the vital statistics birth record: gestational age, which we used to create a preterm birth indicator (<37 weeks gestation); parity of the current pregnancy (nulliparous, indicating a first-time mother versus multiparous, indicating a mother with at least one prior pregnancy lasting longer than 20 weeks); and month of entry into prenatal care, which we used to create a dichotomous indicator of entry to care in the first trimester (<13 weeks) or not. Sociodemographic data extracted from the birth certificate included maternal age, race/ethnicity, and education. A small proportion of age values (0.06%) were missing; in these cases, maternal age was derived from the patient discharge file. We classified race/ethnicity as non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Asian, and Other. We categorized maternal education as those who had completed high school and were at least 16 years of age, and those who had not completed high school.

Additional covariates included comorbidities that have previously been found to be associated with cesarean delivery. These included hypertension, diabetes, and mental health conditions. Chronic hypertension was identified if documented on either the birth certificate or patient discharge file. Gestational hypertension or preeclampsia was extracted in a similar fashion. We identified women with chronic diabetes and gestational diabetes in the discharge file. We identified women with mental health conditions based on diagnoses in the discharge file (see Appendix A for a list of these ICD-9 codes). Our final covariate was health insurance (public insurance, private health insurance, or no insurance) as indicated in the discharge file.

We used descriptive statistics to characterize the sample overall, assessing demographic and health differences between women with and without disabilities using chi square tests. We then created figures to visualize time patterns in: 1) the proportion of births in which the mother had a code associated with possible disability (overall and stratified by parity); and 2) primary cesarean deliveries by disability presence and type. Lowess smoothing was applied in the figures to clarify general patterns in the context of annual fluctuations. Lastly, we conducted logistic regression analyses of the association between disability and primary cesarean delivery, stratified by year. We used Stata 14 for data analysis (StataCorp. 2015. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). Figures were created using R version 3.2.2 (R Core Team. 2015. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Compared to women without disabilities, women with disabilities were more likely to be non-Hispanic White, have completed high school, and be age 35 or older at the time of delivery (Table 1). They were also more likely to be nulliparous, to have preterm births, and to have comorbidities that could increase the risk of cesarean delivery.

Table 1.

Characteristics of women giving birth in California 2000–2010

| Cohort n (%) |

No Disability n (%) |

Any Disability n (%) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 5,432,533 | 5,406,679 (99.52) | 25,854 (0.48) | - |

| Maternal race/ethnicity | <0.001 | |||

| White | 1,494,976 (27.52) | 1,484,483 (27.46) | 10,493 (40.59) | |

| Black | 290,453 (5.35) | 288,457 (5.34) | 1,996 (7.72) | |

| Hispanic | 2,935,299 (54.03) | 2,924,502 (54.09) | 10,797 (41.76) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 580,233 (10.68) | 578,374 (10.7) | 1,859 (7.19) | |

| Other | 100,576 (1.85) | 100,025 (1.85) | 551 (2.13) | |

| Completed high school | 3,738,466 (68.82) | 3,718,439 (68.77) | 20,027 (77.46) | <0.001 |

| Maternal age 35+ | 903,534 (16.63) | 897,520 (16.6) | 60,014 (23.26) | <0.001 |

| Nulliparous | 2,126,378 (39.14) | 2,114,894 (39.12) | 11,484 (44.42) | <0.001 |

| Prenatal care in 1st trimester | 4,536,743 (83.51) | 4,514,773 (83.5) | 21,970 (84.98) | <0.001 |

| Preterm birth | 456,446 (8.4) | 453,071 (8.38) | 3,375 (13.05) | <0.001 |

| Chronic diabetes | 36,909 (0.68) | 36,016 (0.67) | 893 (3.45) | <0.001 |

| Gestational diabetes | 352,860 (6.5) | 350,021 (6.47) | 2,839 (10.98) | <0.001 |

| Chronic hypertension | 53,162 (0.98) | 52,426 (0.97) | 736 (2.85) | <0.001 |

| Gestational hypertension (preeclampsia) | 277,579 (5.11) | 275,448 (5.09) | 2,131 (8.24) | <0.001 |

| Mental health diagnosis | 59,880 (1.1) | 58,213 (1.08) | 1,649 (6.38) | <0.001 |

| Insurance | <0.001 | |||

| Public | 2,592,641 (47.72) | 2,581,109 (47.74) | 11,532 (44.6) | |

| Private | 2,725,306 (50.17) | 2,711,303 (50.15) | 14,003 (54.16) | |

| None | 113,716 (2.09) | 113,398 (2.1) | 318 (1.23) |

Among all women giving birth in California, the proportion with a diagnosis code associated with disability steadily increased from 0.27% (1,335/486,527) in 2000 to 0.80% (3,725/465,691) in 2010 (Figure 1). When stratifying by parity, similar patterns were apparent for both nulliparous and multiparous women (Figure 2). Among nulliparous women, the proportion of deliveries with a disability-related diagnosis code increased from 0.33% (626/188,875) in 2000 to 0.85% (1,565/184,229) in 2010. Among multiparous women, the proportion with disability-related codes rose from 0.24% (705/296,884) in 2000 to 0.77% (2,153/280,196) in 2010.

Figure 1.

Proportion of all births (N=5,432,433) in which the mother had a documented disability diagnosis by year (California, 2000–2010)

Figure 2.

Proportion of nulliparous births (N=2,126,378) and multiparous births (N=3,299,831) in which the mother had a documented disability diagnosis by year (California, 2000–2010)

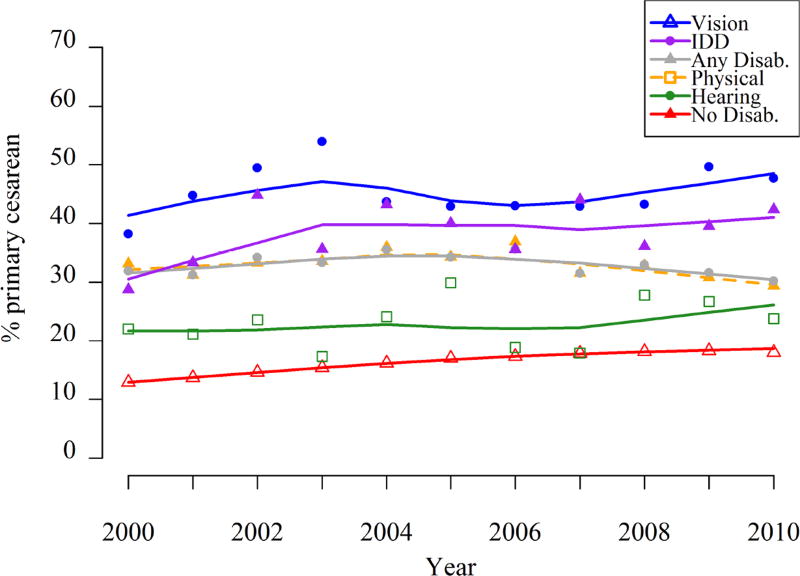

Figure 3 shows the proportions of births that were primary cesarean deliveries for each disability group in each year. Women with no disabilities consistently had the lowest proportion of primary cesarean deliveries, although this proportion increased from 12.9% in 2000 to 18.3% in 2009 before reducing slightly to 17.9% in 2010. Time trends for the disability groups were more variable (Figure 3). For the overall disability population, the proportion of primary cesarean deliveries started at 31.9%, increased slightly to a high of 35.5% in 2006, then tapered off slightly to 30.2% in 2010. That pattern was driven primarily by women with physical disabilities, who constituted 81.9% (17,085/20,860) of the total number of women with disabilities. (See Appendix B for a sensitivity analysis with a more narrowly defined physical disability category.) Women with hearing limitations were the disability group with the lowest proportion of primary cesarean deliveries, in some years nearly matching the proportion for women with no disabilities. Women with vision limitations were the group most likely to deliver by cesarean, with 38.2% of this group having primary cesarean deliveries in 2000, rising to a peak of 54.0% in 2003, decreasing to around 43% for a few years, and then rising again to 49.6% in 2009 and 47.7% in 2010. In every year but 2000, women with IDD had the second highest proportion of primary cesarean deliveries, ranging from a low of 28.8% in 2000 to a high of 44.8% in 2002 and ending the decade at 42.3% in 2010.

Figure 3.

Percent of primary cesarean deliveries by disability and year. (Analytic sample is women without prior cesarean delivery, N=4,605,061).

In multivariable analyses controlling for potential confounders, the adjusted odds ratios of primary cesarean delivery for women with any disability decreased over time from 2.60 (95% CI = 2.25 – 2.99) in 2000 to 1.66 (95% CI = 1.51 – 1.81) in 2010 (Table 2). Of note, the confidence intervals of the adjusted odds ratios for the most recent years of data do not overlap with those from the earliest years, suggesting that disparities in cesarean delivery decreased over time – the decrease in adjusted odds of cesarean delivery among women with disabilities compared with women without disabilities was statistically significant.

Table 2.

Adjusted odds ratios (AOR)* of primary cesarean, comparing women with disabilities to those without disabilities in each year. (Analytic sample is women without prior cesarean delivery.)

| Year | n | AOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 393,302 | 2.60 (2.25 – 2.99) |

| 2001 | 387,394 | 2.32 (2.02 – 2.67) |

| 2002 | 381,376 | 2.52 (2.20 – 2.88) |

| 2003 | 384,273 | 2.24 (1.97 – 2.54) |

| 2004 | 383,966 | 2.35 (2.08 – 2.65) |

| 2005 | 396,449 | 2.06 (1.83 – 2.31) |

| 2006 | 406,349 | 2.27 (2.04 – 2.52) |

| 2007 | 400,704 | 1.80 (1.64 – 1.98) |

| 2008 | 390,672 | 1.83 (1.67 – 2.00) |

| 2009 | 369,789 | 1.73 (1.57 – 1.90) |

| 2010 | 358,133 | 1.66 (1.51 – 1.81) |

Controlling for: maternal race/ethnicity, maternal education, maternal age, parity, initiation of prenatal care in the 1st trimester, preterm birth, chronic diabetes, gestational diabetes, chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension/preeclampsia, mental health diagnosis, and insurance.

Discussion

Among women giving birth in California, the proportion with a diagnosis code suggesting a disability more than doubled between the years 2000 and 2010, supporting our first hypothesis. Because we only had access to diagnosis codes from the delivery record as opposed to a mother’s full medical record, it is likely that the actual proportions of women giving birth each year were larger than the percentages we found in this dataset. There may also have been variations over time in accuracy of coding of diagnoses related to maternal disability status. Thus, the magnitude of change from year to year reflected in these data may not be precise. Nonetheless, the overall trend of women with disabilities being increasingly represented among women giving birth was clear.

In each year of the study period, women with disabilities had significantly greater odds of delivering by cesarean. This is consistent with cross-sectional studies that have found higher proportions of cesarean deliveries among women with intellectual and developmental disabilities [4, 24], physical disabilities [2–31], and sensory disabilities [24] compared to women with no disabilities. The medical necessity of cesarean deliveries among women with disabilities has been raised as a question in need of examination [32]. Women with disabilities have reported that decisions about mode of delivery were made without their input, and many have expressed concern that they will not be given the opportunity to deliver vaginally simply because they have a disability [2]. Cesarean deliveries may indeed be needed for women with some specific conditions (e.g. achondroplasia). However, there are also conditions where cesarean delivery is very common but may not be necessary. For example, women with spinal cord lesions at or above T6 are frequently delivered by cesarean due to fears of autonomic dysreflexia [33, 34], but an epidural could be sufficient to prevent that risk while allowing women to deliver vaginally [35]. Moreover, surgery and anesthesia may present increased risks for women with disabilities, and recovery from surgery may be more complicated [33, 36]. Thus, unnecessary cesareans are especially important to avoid in this population.

Encouragingly, and contrary to our second hypothesis for this study, cesarean deliveries did not increase at a greater rate for women with disabilities than for those without disabilities. In fact, from 2000 to 2010, we saw a decrease in the magnitude of the odds ratio for cesarean delivery among women with disabilities compared to women without disabilities. While the prevalence of cesarean delivery steadily increased for women without disabilities, it stayed relatively level for women with disabilities. This finding suggests two possibilities. One possibility is that clinicians were already so cautious about delivering women with disabilities vaginally that there was less room for a further increase in application of cesarean delivery in this population. A second possibility is that the higher proportion of cesarean deliveries among women with disabilities is a reflection of more objective determinations of medical necessity and thus has not been influenced by the pattern of increasing cesarean deliveries in response to subjective indications as has been the case for women without disabilities. Efforts to better understand the reasons for cesarean deliveries among women with disabilities are needed. Our research team is currently investigating medical indications for cesarean deliveries to shed light on how coded indications do or do not differ between women with and without disabilities.

The pattern of cesarean deliveries by year among women with disabilities was heavily influenced by women with physical disabilities, our largest disability type category. Time trends were more variable for smaller disability groups. The estimates for women with sensory disabilities and women with IDD shown in Figure 3 should be interpreted with caution, as they are based on relatively small sample sizes in each year and are not adjusted for covariates. The high proportion of cesarean deliveries among women with vision impairments is likely attributable in part to high prevalence of both chronic and gestational diabetes in this group [24]. Patterns of cesarean deliveries by disability type have been examined in greater detail elsewhere [24].

Our current findings are subject to the limitations of our data source. We were reliant on identifying disability via diagnosis codes, which bear an inexact relationship with functional limitations. As already noted, we only had access to ICD-9 codes recorded in the delivery discharge record, and therefore may have missed relevant diagnoses from elsewhere in women’s medical records. As such, we likely underestimate the proportions of women with disabilities within the cohorts of women who gave birth in California during 2000–2010. Moreover, diagnoses coded in the delivery record may tend to be most inclusive of conditions that are obvious and that may impact delivery, perhaps inflating the association between disability and cesarean delivery. However, these data also have important strengths. They represent a complete census (not a sample) of births in the most populous and one of the most diverse states in the U.S. The size of the dataset provides a rare opportunity to conduct year-by-year analyses by disability. Our data also allowed us to determine that the disabilities existed at or near the time of delivery.

Conclusion

Ours is the first study to date to examine time trends in births and mode of delivery to women with disabilities. Further research with additional years of data is needed to confirm the patterns we found. Based on data from 2000 to 2010, women with disabilities appear to be increasingly represented among women giving birth. Thus, the likelihood of an obstetrician or midwife encountering a woman with a disability in a practice context is likely to continue to grow. Adequate training and preparation for addressing the perinatal care needs of these women is therefore a high priority. Although women with disabilities have greater odds of primary cesarean delivery, it is encouraging that the proportion delivering by cesarean did not markedly increase between 2000 and 2010 as it did for women without disabilities. Continued efforts to understand cesarean delivery patterns and the reasons for cesarean deliveries may help guide further reductions in disparities between women with and without disabilities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under award #R21HD081309 (Horner-Johnson, PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Support for Dr. Horner-Johnson’s time was provided by grant #K12HS022981 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (Guise, PI). Dr. Darney is partially supported by a Junior Investigator Award from the Society of Family Planning. The funding agencies had no role in the conduct of the research or preparation of the manuscript for submission.

The authors thank Mekhala Dissanayake for analysis assistance during the manuscript revision process.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Prior Presentations

Portions of this analysis were presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Public Health Association, October 30-November 2, Denver, Colorado.

References

- 1.Iezzoni LI, et al. Prevalence of current pregnancy among US women with and without chronic physical disabilities. Med Care. 2013;51(6):555–62. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318290218d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smeltzer SC. Pregnancy in women with physical disabilities. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2007;36(1):88–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitra M, et al. Maternal characteristics, pregnancy complications, and adverse birth outcomes among women with disabilities. Med Care. 2015;53(12):1027–32. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parish SL, et al. Pregnancy outcomes among U.S. women with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2015;120(5):433–43. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-120.5.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanchette H. The rising cesarean delivery rate in America: what are the consequences? Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):687–90. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318227b8d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MJ. Births: preliminary data for 2015. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016;65(3):1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyle A, Reddy UM. Epidemiology of cesarean delivery: the scope of the problem. Semin Perinatol. 2012;36(5):308–14. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barber EL, et al. Indications contributing to the increasing cesarean delivery rate. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(1):29–38. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821e5f65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tita AT. When is primary cesarean appropriate: maternal and obstetrical indications. Semin Perinatol. 2012;36(5):324–7. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caughey AB, et al. Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(3):179–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen MT, McCullough LB, Chervenak FA. The importance of clinically and ethically fine-tuning decision-making about cesarean delivery. J Perinat Med. 2016 doi: 10.1515/jpm-2016-0262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng YW, et al. Litigation in obstetrics: does defensive medicine contribute to increases in cesarean delivery? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27(16):1668–75. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.879115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smeltzer SC, et al. Perinatal experiences of women with physical disabilities and their recommendations for clinicians. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2016;45(6):781–789. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2016.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Obstetric Care Consensus No. 3: Periviable birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(5):e82–94. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stoll BJ, et al. Trends in care practices, morbidity, and mortality of extremely preterm neonates, 1993–2012. JAMA. 2015;314(10):1039–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goff SL, et al. Validity of using ICD-9-CM codes to identify selected categories of obstetric complications, procedures and co-morbidities. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26(5):421–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2012.01303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lain SJ, et al. Quality of data in perinatal population health databases: a systematic review. Med Care. 2012;50(4):e7–20. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31821d2b1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lydon-Rochelle MT, et al. The reporting of pre-existing maternal medical conditions and complications of pregnancy on birth certificates and in hospital discharge data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(1):125–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lydon-Rochelle MT, et al. Accuracy of reporting maternal in-hospital diagnoses and intrapartum procedures in Washington State linked birth records. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2005;19(6):460–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2005.00682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khoury AJ, et al. The association between chronic disease and physical disability among female Medicaid beneficiaries 18–64 years of age. Disabil Health J. 2013;6(2):141–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mann JR, et al. Children with hearing loss and increased risk of injury. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(6):528–33. doi: 10.1370/afm.740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Javitt JC, Zhou Z, Willke RJ. Association between vision loss and higher medical care costs in Medicare beneficiaries costs are greater for those with progressive vision loss. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(2):238–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin E, et al. Using administrative health data to identify individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: a comparison of algorithms. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2013;57(5):462–77. doi: 10.1111/jir.12002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Darney BG, Biel FM, Quigley B, Caughey AB, Horner-Johnson W. Primary cesarean delivery patterns by presence and type of maternal disability. Women's Health Issues. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2016.12.007. [Epub ahead of print] http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2016.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Arata M, et al. Pregnancy outcome and complications in women with spina bifida. J Reprod Med. 2000;45(9):743–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Argov Z, de Visser M. What we do not know about pregnancy in hereditary neuromuscular disorders. Neuromuscul Disord. 2009;19(10):675–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chakravarty EF, Nelson L, Krishnan E. Obstetric hospitalizations in the United States for women with systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(3):899–907. doi: 10.1002/art.21663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morton C, et al. Pregnancy outcomes of women with physical disabilities: a matched cohort study. Pm r. 2013;5(2):90–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudnik-Schoneborn S, Zerres K. Outcome in pregnancies complicated by myotonic dystrophy: a study of 31 patients and review of the literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;114(1):44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2003.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skomsvoll J, et al. Obstetric and neonatal outcome in pregnant patients with rheumatic disease. Scand J Rheumatol Suppl. 1998;107:109–112. doi: 10.1080/03009742.1998.11720781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winch R, et al. Women with cerebral palsy: obstetric experience and neonatal outcome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1993;35(11):974–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1993.tb11579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Signore C, et al. Pregnancy in women with physical disabilities. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(4):935–47. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182118d59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jackson AB, Wadley V. A multicenter study of women's self-reported reproductive health after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80(11):1420–8. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Le Liepvre H, et al. Pregnancy in spinal cord-injured women, a cohort study of 37 pregnancies in 25 women. Spinal Cord. 2016 doi: 10.1038/sc.2016.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.ACOG Committee Opinion: Number 275, September 2002. Obstetric management of patients with spinal cord injuries. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(3):625–7. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02261-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jackson AB, et al. Reproductive health for women with spinal cord injury: pregnancy and delivery. SCI Nurs. 2004;21(2):88–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.