Abstract

Background

Each year at least 40,000 individuals receive an ostomy due to cancer. Living with an ostomy requires daily site and equipment care, lifestyle changes, emotional management, and social role adjustments. The Chronic Care Ostomy Self-management Training Program (CCOSMTP) offers an ostomy self-management curriculum; emphasizing problem-solving, self-efficacy, reframing cognitive responses, and goal setting.

Objectives

The qualitative method of content analysis was employed to categorize self-reported goals of ostomates identified during a nurse-led feasibility trial testing the CCOSMTP.

Methods

Thirty-eight ostomates identified goals at three CCOSMTP sessions. The goals were classified according to the City of Hope Health-Related Qualify of Life Model, a validated multi-dimensional framework, describing physical, psychological, social and spiritual ostomy-related effects. Nurse experts coded the goals independently and then collaborated to reach 100% consensus on the goals’ classification.

Findings

One-hundred and eighteen goals were identified by 38 participants. Eighty-seven goals (77.2%) were physical goals, related to the care of the skin, placement of the pouch/bag and management of leaks. There were 26 social goals (22.0%) addressing engagement in social/recreation roles and daily activities and five (0.8%) psychological goals on confidence and controlling negative thinking. While ostomy cancer survivors’ goals are variable, physical goals are most common in self-management training.

It is estimated that each year at least 40,000 individuals receive an ostomy due to either colorectal or genitourinary cancers (Seigel, Ma, Zou, & Jemal, 2014). Ostomies are the surgical attachment of bowel or ureter to the abdominal wall to allow elimination of feces or urine. An ostomy results in major life disruptions that impact the well-being of the whole individual; physically, psychologically, socially, and spiritually. Impacts include daily care of the stoma and skin, correct fitting of pouches, diet and elimination strategies, making adjustments in social routines in order to integrate daily care requirements, and attending to potentially negative emotional and spiritual changes that may accompany chronic care demands (Crawford et al., 2012; Recalla et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2014). The trend toward shorter hospital stays has resulted in fewer opportunities for specialized trained ostomy nurses to support patients with new ostomies. Thus, oncology nurses in both the hospital or outpatient settings may need to play a role in assisting ostomates to self-manage disease-related effects (Crawford et al., 2012).

Background

Chronic illness self-management has been increasingly studied as we have enabled individuals to live beyond acute episodes of most major diseases (Barlow, Wright, Sheasby, Turner, & Hainsworth, 2002). As a result, health care professionals’ concerns have shifted from cure to control of symptoms and disease effects. Patients living with a chronic illness are challenged to manage illness-related effects that impact their physical, psychological, and social roles in order to preserve or improve their health. In chronic illness management, patients become “experts” about their illnesses and their health care provides serve as coaches or consultants. This shared responsibility for illness-related activities by patients and health care professionals has earned the name “self-management” versus “self-care” due to the complexities of the skills and tasks required (Coster & Norman, 2009). The Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP) developed by Kate Lorig at Sanford University is a formal course that teaches patient self-management, incorporating content on care strategies along with activities to improve self-efficacy, problem-solving, and communication. The CDSMP program has been tested and proven beneficial in a variety of chronic illnesses (Barlow, Wright, Sheasby, Turner, & Hainsworth, 2002; Cockle-Heame & Faithfull, 2010; Ory et al., 2014).

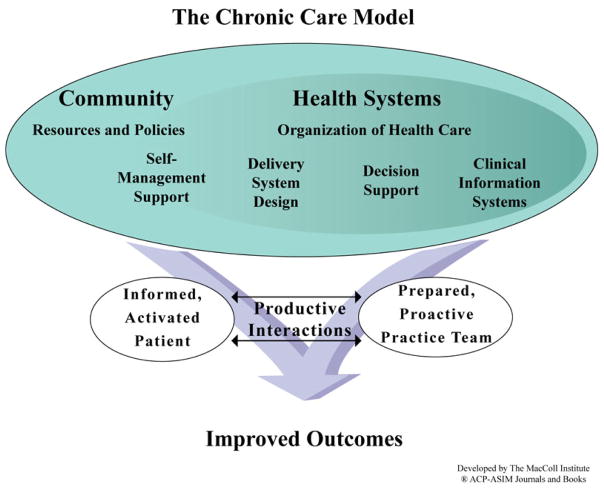

In 1996, the Chronic Care Model (CCM) was proposed as an alternative health care delivery system in order to improve illness-related outcomes (Wagner et al., 2001; Gugiu, Westine, Coryn, & Hobson, 2012). Figure 1 illustrates the model’s components, including self-management support (between patients and health care providers) and health system re-organization (clinical guidelines, integrated clinical information systems, and enhanced coordination of services) to enable care of chronic illness effects and health promotion efforts. The model transforms how chronic illness should be viewed; proposing, instead, that facilitation of patient self-management results in an informed, self-directed patients, more engaged and appropriate provider responses, and improved health-related outcomes (Gugiu, Westine, Coryn, & Hobson, 2012).

Figure 1.

The Chronic Care Model

The Chronic Care Ostomy Self-Management Program (CCOSMTP) was developed to address the consequences of living with an ostomy and to support patient self-management. The CCOSMTP builds on the principles of the CSMDP by Kate Lorig at Stanford University and the CCM. The CCOSMTP curriculum addresses practical and physical, emotional, social, and spiritual quality of life concerns (Table 1). The program includes strategies to enhance problem-solving, self-efficacy, reframing of cognitive responses, and goal setting (Grant, McCorkle, Hornbrook, Wendel, & Krouse, 2013; Lorig & Holman, 2003; Wagner et al., 2001).

Table 1.

The Chronic Care Ostomy Self-Management Training Program

| Topic | Curriculum |

|---|---|

| Practical Concerns of Living with An Ostomy | Self-management of equipment, complications, establishing a regular pattern of elimination |

| Physical Effects and Physical General Well-Being | Skin care, managing leakages, odors, gas, pain, fatigue, clothing changes, sleep disturbances, nutrition, exercise, other lifestyle changes |

| Psychological Effects and Psychological General Well-Being | Managing depression, anxiety, uncertainty, privacy, fear of recurrence, and negative thinking |

| Social Effects and Social General Well-Being | Preparation for emergencies, travel, work, social and public obligations, intimacy and sexuality, caregiver and partner relationships, financial management |

| Spiritual Effects | Acknowledging and applying meaning, faith |

Identification of illness-related goals has been shown to be beneficial in chronic illness self-management (Lorig & Holman, 2003). Goal setting helps individuals to identify and prioritize new behaviors required to master illness-related effects. When the goal is designed to address, mediate or improve the chronic illness effect, the greater the likelihood of behavioral change (Martin, Turner, Bourne, & Bateup, 2013). Goal setting has been incorporated into chronic disease self-management programs on diabetes, arthritis, and more recently in cancer (DeWalt et al., 2009; Kralik, Koch, Price, & Howard, 2004; Martin, Turner, Bourne, & Batehup, 2013; McCorkle et al., 2011; Schulman-Green et al., 2012).

The purpose of this study, therefore, is to report on the goals identified by a group of ostomates who participated in a nurse-lead self-management intervention: The Chronic Care Ostomy Self-Management Training Program (CCOSMTP). The study’s purpose was accomplished by using the City of Hope Health-Related Quality of Life (COHHRQOL) model to analyze the goals of ostomates who participated in the Chronic Care Ostomy Self-0management Training Program (CCOSMTP).

Theoretical Framework

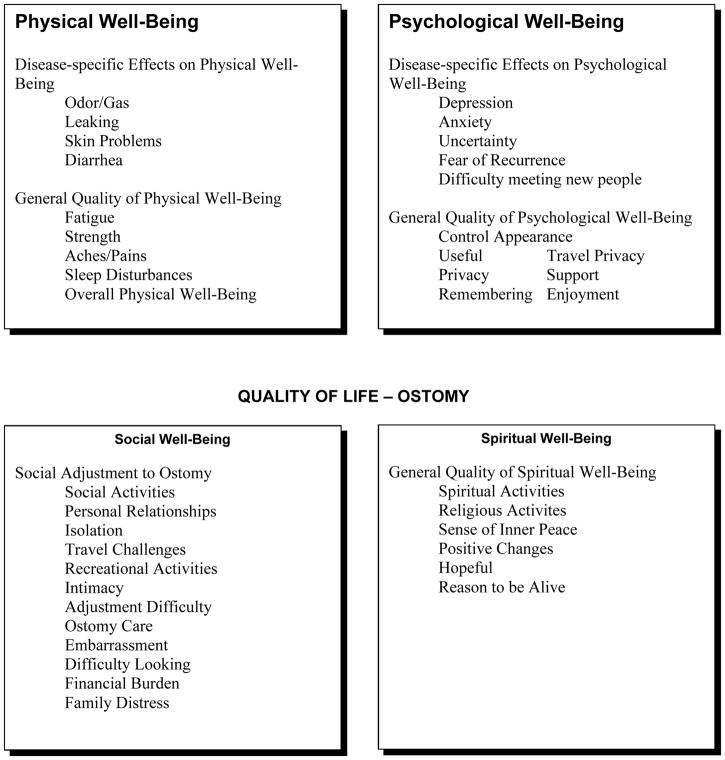

The COHHRQOL model, composed of four dimensions: physical well-being and functional status, psychological well-being, social well-being, and spiritual well-being guided the study design and analytical procedures. This framework was developed from the findings of qualitative and quantitative studies on ostomy-related quality of life changes. The model depicts the interrelationships of the four quality of life dimensions and their general and disease-specific effects. This holistic model illustrates that comprehensive management of all domain-related effects is needed to support improvement in overall quality of life (Grant, McCorkle, Hornbrook, Wendel, & Krouse, 2013) (Figure 2)..

Figure 2.

City of Hope Health Related Quality-of-Life Model

Design

Directed content analysis was employed to describe and categorize self-reported goals of ostomates who participated in a nurse-led feasibility trial on ostomy self-management (Grant, McCorkle, Hornbrook, Wendel, & Krouse, 2013; Hsieh & Shannon, 2005).

Participants and Setting

Thirty-eight ostomates enrolled in and participated in Wound, Ostomy and Continence (WOC) nurse-led sessions based on a well-defined ostomy self-management curriculum, as part of a feasibility trial testing the effects of this ostomy self-management curriculum. The feasibility trial was approved by the University of Arizona Institution Review Board. Table 1 illustrates the specific topics and related curriculum. The curriculum addressed physical effects associated with an ostomy and their related management, including care of the appliance, stoma, nutrition, and lifestyle changes. Other areas of the curriculum included management of psychological effects including depression and uncertainty, and adjusting to social changes in work and other social or public obligations. Ostomates were asked by the nurses to list three goals prior to the first session and again at two later sessions. They were instructed to describe the goal-directed behaviors that they desired to achieve in order to alter or manage their treatment--related effects. Goals could be either broad or specific.

Analysis Processes and Procedures

The approach to analyzing the content of the goals was directed content analysis as defined by Hsieh and Shannon (2005). Directed content analysis is used by researchers to confirm a theoretical framework in this case, the approach was employed to validate the COHHRQOL model and its relationship to the CCOSMTP. Initially, a panel of nurse experts (two Oncology and two WOC nurses) created and agreed upon a coding system derived from the components of the COHHRQOL model. Specifically, the coding system was created by first outlining the broad domains of the model: physical well-being and function, psychological well-being, social well-being, and spiritual well-being. Next, the nurse-experts created the coding system for the treatment-effects specific to each domain. We assumed that the goals identified by the participants at the three sessions would match the domain and treatment-related effects outlined in the model. For example, a physical treatment-related effect that would lend itself to a goal would be: managing leaks or dealing with odor/gas.

Once the coding template was created and agreed upon, each nurse expert independently applied the codes to the patient-identified goals and organized the codes by domains and treatment effects and by session. In the second round, the nurse experts collaborated to discuss any coding discrepancies by domain or treatment-effect. Overall, there were minimal discrepancies noted; the most frequent were distinguishing among problems/goals related to leaking and skin care. Each coding discrepancy was discussed in order to reach 100% agreement on the goals’ classification. The final agreed upon classification is presented as findings (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005)

The credibility of the content of the ostomy self-management curriculum is based on extensive qualitative and quantitative research by our team, (Grant et al., 2004), literature review (McMullen et al., 2008; Krouse et al., 2006), and use of the Quality of Life-Ostomy model (Figure 2), as the foundation for the content. (Grant et al., 2013). This model was derived from an extensive literature review, validated over a number of cancer populations and resulted also in a survey composed of forced choice and open-ended questions to ostomates in a national population. The survey has established validity and reliability.

Findings

All thirty-eight individuals living with an ostomy completed one or more of the goal setting sessions. Most of the participants had an ostomy due to colorectal cancer (52.6%) or bladder cancer (26.3%). The majority were Caucasian (86.8%) and male (73.7%). The mean number of days living with an ostomy was 201 days (Table 2).

Table 2.

Participant Demographic and Health-Related Characteristics (N=38)

| Demographic and Health-Related Characteristic | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age, years [mean (SD)] | 70.5 (7.7) [range 60 – 82] |

|

| |

| Frequency (%) | |

|

| |

| Male | 28 (73.7%) |

|

| |

| Race | |

| White | 33 (86.8%) |

| Black | 1 (2.6%) |

| Missing | 4 (10.5%) |

|

| |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 0 |

| Missing | 4 (10.5%) |

|

| |

| Cancer type | |

| CRC | 20 (52.6%) |

| Bladder | 10 (26.3%) |

| Ovarian | 1 (2.6%) |

| Prostate | 1 (2.6%) |

| CRC/Bladder/Prostate | 1 (2.6%) |

| Missing | 5 (13.1%) |

|

| |

| Time since ostomy, days [mean (SD)] | 201 (305) [range 22 – 1626] |

There were 118 goals identified by the participants for the three sessions. Eighty-seven goals (77.2%) were related to ostomy specific physical effects and general physical well-being, followed by 26 goals (22.0%) that addressed social concerns. There were few psychological goals and no spiritual goals. Table 3 summarizes the goals by the HRQOL domain and by session.

Table 3.

Physical, Social, Psychological, and Spiritual Goals of Ostomates

| Goals | Session 1 | Session 2 | Session 3 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | 63 | 21 | 3 | 87 |

| Social | 17 | 8 | 1 | 26 |

| Psychological | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| Spiritual | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The next level of our content analysis resulted in detail about the specific treatment effects. Table 4 outlines the categories of the goals for each of the treatment-related effects. The major categories representing physical goals associated with treatment effects were placement and care of the pouch/bag, nutrition, skin problems, and leaks. Categories of social goals were related to recreation and social engagement followed by achieving activities of daily living (ADLs). The categories of goals described for psychological treatment effects, although not as predominant as the physical goals were: building confidence, controlling obsessive thinking about the ostomy, achieving awareness, and maintaining a positive attitude. For all treatment effects, the number of goals decreased over time.

Table 4.

Goal Categories by Cancer-Related Treatment Effects

| Goal Categories | Session 1 | Session 2 | Session 3 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Physical Effects | ||||

| Odor/Gas/Noise | 6 | 3 | 0 | 9 |

| Skin Problems | 9 | 3 | 0 | 12 |

| Leaks | 8 | 3 | 0 | 11 |

| Elimination | 6 | 2 | 0 | 8 |

| Care of Appliance | 6 | 3 | 2 | 11 |

| Placement of Pouch/Bag | 11 | 3 | 0 | 14 |

| Nutrition | 10 | 4 | 1 | 15 |

| Aches/Pain | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Sleep Disturbance | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

|

| ||||

| Total | 63 | 21 | 3 | 87 |

|

| ||||

| Social Effects | ||||

| Perform ADLs | 5 | 2 | 0 | 7 |

| Recreational/Social | 8 | 3 | 0 | 11 |

| Travel Challenges | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 |

| Daily adjustments | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

|

| ||||

| Total | 17 | 8 | 1 | 26 |

|

| ||||

| Psychological Effects | ||||

| Confidence | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Control obsessive thoughts | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Awareness of feelings | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Maintain positive attitude | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

|

| ||||

| Total | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

Limitations

The focus of this analysis was to understand the primary goals of ostomates. While participants were helped to articulate achievable goals, we did not have the resources to follow up on goal attainment and relate quality of life changes to goal attainment (Bogardus et al., 2004; DeWalt et al., 2009). This would be important to add in future research (Hurn, Kneebone, & Cropley, 2006). In spite of this, we were able to assist the ostomates to consider and prioritize quality of life impacts associated with their ostomies; also we were able to help the ostomates describe these quality of life consequences as behaviors they desired to change. (Grant et al., 2004; Krouse et al, 2007).

Discussion

This study described goal setting as a component of an ostomy self-management program based on a validated holistic model of ostomy care and evidence-based ostomy self-management curriculum. Our findings demonstrate how in the context of education, cognitive reframing, and self- enhancing approaches, ostomates reported individualized goals that targeted a range of problems. Because goal setting is an accepted component of self-management interventions; self-management curriculum and cognitive and affective approaches offer the potential for participants to identify accurate, realistic behaviors they have confidence to achieve (DeWalt et al., 2009; Schulman-Green et al., 2012).

The goals described by our participants were predominately physical ones. These goals addressed managing ostomy-related effects or complications, including, care of the appliance, skin issues, and problems with leakage. Goals based on social treatment effects including socialization/recreation or capacity to achieve activities of daily living were consistent with social adjustments reported previously by ostomates (Recalla et al., 2013; McMullen et al., 2008). Although participants identified fewer social and psychological goals than physical goals, we hypothesized that ostomy-related physical effects often overshadow all other concerns for ostomate. This is confirmed when one relates these findings to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs where physical need provide the foundation for other identified needs (Maslow & Lowery, 1998). However, the types of psychological goals identified by participants, (building confidence and controlling negative thinking), were representative of the self-management affective and cognitive strategies promoted and monitored by the ostomy nurses in the CCOSMTP. While there were no spiritual goals identified by the ostomates, this was not an unexpected finding. In 2007, The National Consensus Project and the National Quality Forum published a paper identifying the preferred practices in palliative care. Content was shaped by the four dimensions of the Quality of Life Model (Table 1). (Ferrell et al., 2007). A recent article indicating progress in this area promotes the need to integrate spirituality education and research, and indicates a lack of professional application of spirituality to the support, education, and clinical care of patients (Ferrell & Borneman, 2015). As this education and research trickles down through professional education, we would expect to see spirituality aspects in patient education and goals of care.

Implications for Oncology Nursing Practice

Table 5 describes key nursing implications. A major clinical implication of this study is that management of ostomies and ostomy-related effects is multidimensional and changing. Oncology nurses must also recognize that patients’ concerns be prioritized and redirected to identifying goals that lend themselves to self-management behaviors. Our findings reveal that, initially, patient concerns such as equipment and daily bowel/bladder routines predominate, therefore, oncology nurses and ostomy-trained nurses should direct and coach ostomates to identify goals that address behavioral change to meet these concerns. Next, as daily care becomes familiar, attention on the part of nurses should be directed towards management of physical complications (leakage, skin excoriation, fatigue, etc). Over time, as complications lessen, and daily routines are established, the oncology nurse and the ostomate should collaborate on identifying goals and related behavioral changes that address adjustments in social roles, including work and recreation. Use of therapeutic communication strategies will enable nurses to identify emotional reactions to ostomy-related physical changes and a cancer diagnosis. At this time, nurses may engage ostomates in identifying goals that represent psychological effects of an ostomy. Ongoing education and strategies on the part of nurses to enhance self-efficacy and coping responses (psychological or spiritual-based) will promote adjustment and more focused goal identification (Martin, Turner, Bourne, & Batehup, 2013). Educational resources about ostomy management and effects of living with an ostomy may be used by oncology nurses in their goal-planning process. Figure 3 outlines useful educational resources on ostomy care.

Table 5.

Implications for Oncology Nursing Practice

| Ostomy-related effects are chronic, variable, and multidimensional affecting all areas of quality of life. |

| Assist ostomates to prioritize ostomy-related effects that require their self-management. |

| Engage ostomates in goal setting to describe behaviors to address ostomy-related effects. |

| Employ other self-management support strategies including communication, education, and cognitive reframing. |

Figure 3.

Patient Education Resources

Conclusions

Cancers of the gastrointestinal and genitourinary systems often require surgical interventions necessitating an ostomy. An ostomy results in major life changes that impact patients’ physical, emotional, social, and spiritual well-being. Physical-related effects typically predominate in the early stage of ostomy adjustment. Overtime, however, psychosocial-related effects are important areas for goal-planning. Self-management training that includes goal setting may be used by oncology nurses to enable ostomates to prioritize ostomy related effects and their associated care strategies.

Acknowledgments

HRQOL-Enhancing Ostomy self-management Intervention for CRC Survivors (NIHR21 CA 133337), Robert Krouse, Principal Investigator.

References

- Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J, Hainsworth Turner A. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: A review. Patient Education and Counseling. 2002;48:177–187. doi: 10.1016/50738-3991(02)00032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogardus ST, Bradley EH, Williams CS, Maciejewski WT, Gallo WT, Inoueye S. Achieving goals in geriatric assessment: Role of caregiver agreement and adherence to recommendation. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2004;52:99–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1532.5415.200-652017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockle-Heame J, Faithfull S. Self-management for men surviving prostate cancer: A review of behavioral and psychosocial interventions to understand what strategies can work, for whom, and in what circumstances. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;19:909–922. doi: 10.1002/pon.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coster S, Norman I. Cochrane review of educational and self-management interventions to guide nursing practice: A review. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2009;46:508–528. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford D, Texter T, Hurt K, VanAelst R, Glaza L, Vander Laan KJ. Traditional nurse instruction versus 2 session nurse instruction plus DVD for teaching ostomy care: A multisite randomized controlled trial. Journal of Wound Ostomy and Continence Nursing. 2012;39:529–537. doi: 10.1097/WON.06013e3182659ca3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWalt DA, Davis TC, Wallace AS, Seligman HK, Bryant-Shilliday B, Arnold CL, Freburger J, Schillinger D. Goal setting in diabetes self-management: Taking the baby steps to success. Patient Education and Counseling. 2009;77:218–223. doi: 10.1016/jpec.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell B, Borneman T. Caring for the Human Spirit. 2015. Spring-Summer. Integrating spirituality into palliative care education and research; pp. 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell B, Connor SR, Cordes A, Cahlin CM, Fine PG, Hutton N, … Qaroski K. The national agenda for quality palliative care: The national consensus project and the national quality forum. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2007;33:737–744. doi: 10.1016/j.painsymman.2007.02024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant M, McCorkle R, Hornbrook M, Wendel CS, Krouse R. Development of a Chronic Care Ostomy Self -Management Program. Journal of Cancer Education. 2013;28:70–78. doi: 10.1007/s13187-012-0433-1. doi:10:1007/513187-012-0433-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant M, Ferrell B, Dean G, Uman G, Chu D, Krouse R. Revision and Psychometric Testing of the City of Hope Quality of Life-Ostomy Questionnaire. Quality of Life Research. 2004;13:1445–1457. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000040784.65830.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gugiu PC, Westine CD, Coryn CLS, Hobson KA. An application of a new evidence grading system to research on the chronic care model. Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2012;36:3–43. doi: 10.77/0163278712436968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurn J, Kneebone I, Cropley M. Goal setting as an outcome measure: A systematic review. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2006;20:756–722. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kralik D, Koch T, Price K, Howard N. Chronic illness self-management: Taking action to create order. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2004;13:259–267. doi: 10.1046/j.1365.2702.2003.00826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krouse R, Grant M, Ferrell B, Dean G, Nelson R, Chu D. Quality of Life Outcomes in 599 Cancer and Non Cancer Patients with colostomies. Journal of Surgical Research. 2007;138:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krouse RS, Mohler MJ, Wendel CS, Grant M, et al. The VA ostomy health-related quality of life study: Objectives, methods, and patient sample. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2006;22(4):781–791. doi: 10.1185/030079906x96380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K, Holman H. Self-management education: History, definition, outcomes and management. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2003;26:1–7. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin F, Turner A, Bourne C, Batehup L. Development and qualitative evaluation of a self-management workshop for testicular cancer survivor-initiated follow-up. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2013;40:E14–E23. doi: 10.1188/13.ONF.Exxx-Exxx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslow A, Lowery R. Toward a Psychology of Being. 3. New York: Wiley and Sons; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- McCorkle R, Ercolano E, Lazenby M, Schulman-Green D, Schilling LS, Lorig K, Wagner EH. Self-management: Enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2011;61:50–62. doi: 10.3322/caac.20093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullen CK, Hornbrook MC, Grant M, Baldwin CM, Wendel CS, Mohler, … Krouse R. The greatest challenges reported by long-term colorectal cancer survivors with stomas. The Journal of Supportive Oncology. 2008;6:175–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ory MG, Smith ML, Ahn S, Jiang L, Lorig K, Whitelaw N. National study of chronic disease self-management: Age comparison of outcome findings. Health Education & Behavior. 2014;41:345–425. doi: 10.1177/1090198114543008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recalla S, English K, Nazarali R, Mayo S, Miller D, Gray M. Ostomy care and management: A systematic review. Journal of Wound Ostomy Continence Nursing. 2013;40:489–500. doi: 10.1097/WON.06013e3182a219a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulman-Green D, Jaser S, Martin F, Alonzo A, Grey M, McCorkle R, Whittemore R. Processes of self-management in chronic illness. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2012;44:136–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2012.01444.x. doi:111/j.1547-5069.2012.01444k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seigel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemel A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun V, Grant M, McMullen CK, Altschuler A, Mohler MJ, Hornbrook M, … Krouse R. From diagnosis through survivorship: Health-care experiences of colorectal cancer survivors with ostomies. Supportive Care Cancer. 2014;22:1563–1570. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2118-2. doi:10.1007s00520-014-2118-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schafer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: Translating evidence into action. Health Affairs. 2001;6:64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlhaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]