Abstract

Many bimodal bilinguals are immersed in a spoken language-dominant environment from an early age and, unlike unimodal bilinguals, do not necessarily divide their language use between languages. Nonetheless, early ASL–English bilinguals retrieved fewer words in a letter fluency task in their dominant language compared to monolingual English speakers with equal vocabulary level. This finding demonstrates that reduced vocabulary size and/or frequency of use cannot completely account for bilingual disadvantages in verbal fluency. Instead, retrieval difficulties likely reflect between-language interference. Furthermore, it suggests that the two languages of bilinguals compete for selection even when they are expressed with distinct articulators.

Keywords: bimodal bilingualism, verbal fluency, lexical retrieval, vocabulary

Despite having the ability to use both languages at high levels of proficiency, bilinguals typically show lower performance than their monolingual peers in verbal tasks that demand lexical access, e.g., picture naming and verbal fluency tasks (e.g., Michael & Gollan, 2005). Importantly, these bilingual ‘disadvantages’ generally persist even when bilinguals complete the verbal task in their first and dominant language (e.g., Gollan, Montoya, Cera & Sandoval, 2008; Ivanova & Costa, 2008).

The verbal fluency test is a word retrieval task that requires participants to produce as many words as possible that satisfy specific criteria within one minute. In category fluency, participants retrieve words from a particular semantic category, e.g., fruits or clothing. In letter fluency, participants retrieve words that begin with a specific letter, e.g., F or S. Because word representations are naturally organized in semantic networks, category fluency is a more automatic and natural process than letter fluency, which is considered to be more effortful and more dependent on executive control strategies (e.g., Grogan, Green, Ali, Crinion & Price, 2009; Delis, Kaplan & Kramer, 2001). Verbal fluency tests are widely used in clinical settings as standard measures of neuropsychological functioning. Therefore, it is critical to investigate the diagnostic ability of these tasks in bilingual populations and to understand the mechanisms underlying possible bilingual disadvantages.

Three possible, not mutually-exclusive, explanations for verbal fluency disadvantages in bilinguals have been proposed (e.g., Bialystok, Craik & Luk, 2008; Sandoval, Gollan, Ferreira & Salmon, 2010; Luo, Luk & Bialystok, 2010): 1) bilinguals may experience interference between exemplars from the target language and non-target language; 2) bilinguals may retrieve target language exemplars more slowly than monolinguals; and 3) smaller vocabulary (within each language) for bilinguals compared to monolinguals may lead to the generation of fewer target language exemplars.

Bilingual disadvantages have been more consistently reported for category fluency than for letter fluency (e.g., Bialystok et al., 2008; Gollan, Montoya & Werner, 2002; Portocarrero, Burright & Donovick, 2007; Rosselli, Ardila, Salvatierra, Marquez, Matos & Weekes, 2002). One possible explanation is that category fluency is more sensitive to non-target language interference because translation equivalents necessarily belong to the same semantic category, whereas they typically do not belong to the same letter category (except for cognates). Furthermore, some studies have reported bilingual advantages on executive control tasks that might benefit bilinguals’ performance on letter fluency tasks more than on category fluency tasks (Bialystok, Craik, Green & Gollan, 2009). Specifically, Luo et al. (2010) compared the time course of word retrieval in category and letter fluency in monolingual English speakers and unimodal bilinguals with lower and higher English vocabulary levels. No group differences were observed for category fluency, but high-vocabulary bilinguals retrieved MORE words than the two other groups in letter fluency (cf. Bialystok et al., 2008). The time course analysis revealed a flatter curve for the two bilingual groups in letter fluency compared to the monolingual group, and a lower-shifted curve for the low-vocabulary bilinguals. Luo et al. (2010) suggested that the flatter curve for the bilinguals reflected enhanced executive control, and that the difference in overall height of the curve reflected the different vocabulary levels of the two bilingual groups.

Only two published studies have compared performance between bimodal bilinguals and monolinguals on a conflict-resolution task and found no evidence for a bimodal bilingual advantage in executive control (Emmorey, Luk, Pyers & Bialystok, 2008a; Giezen, Blumenfeld, Shook, Marian & Emmorey, 2015), possibly because bimodal bilinguals do not experience the same needs for inhibition and control as unimodal bilinguals. Specifically, less monitoring may be required because bimodal bilinguals can speak and sign at the same time, and perceptual discrimination between their two languages is easier than for unimodal bilinguals (see Emmorey et al., 2008a, for discussion). Nonetheless, they must select and control two languages, e.g., in conversations with English monolinguals or deaf signers, and Giezen et al. (2015) reported evidence that bimodal bilinguals rely on inhibitory control mechanisms to suppress cross-language competition when listening to English words.

Studying verbal fluency in the dominant, spoken language of hearing bimodal bilinguals may provide useful insights into the mechanisms that underlie bilingual (dis)advantages in verbal fluency tasks because of their unique bilingual context. The majority of native ASL–English bimodal bilinguals are immersed in a spoken language-dominant environment and, unlike unimodal bilinguals, they do not necessarily divide their language use between languages because they often produce ASL signs and English words at the same time through code-blending and mouthing (Emmorey, Borinstein, Thompson & Gollan, 2008b). Therefore, they are unlikely to have smaller English vocabulary levels than monolingual English speakers, and may also use English more frequently than unimodal bilinguals (Emmorey, Petrich & Gollan, 2013; Pyers, Gollan & Emmorey, 2009).

The goal of the present study was to further investigate the role of non-target language interference, vocabulary size and reduced frequency of use in explaining bilingual disadvantages in verbal fluency. We focused on letter fluency, precisely because of the reduced possibility of the non-target language to influence retrieval of words in the target language for bimodal bilinguals. That is, because of their distinct phonological systems, ASL and English have no cognates (words that share form and meaning across the two languages, e.g., Dutch-English huis-house) that might benefit bilingual letter fluency performance (e.g., Sandoval et al., 2010; Blumenfeld, Bobb & Marian, 2016). Furthermore, bimodal bilinguals might be less likely than unimodal bilinguals to compensate for word retrieval difficulties with enhanced executive control abilities.

Therefore, if bimodal bilinguals retrieve fewer words than monolinguals in their dominant language (English), then this would strongly suggest that vocabulary size and/or reduced frequency of use are not sufficient to account for the bilingual disadvantage in verbal fluency. Furthermore, it would provide evidence that non-target language interference in verbal fluency is not dependent on phonological competition between the two languages. If, on the other hand, bimodal bilinguals and monolinguals do not differ significantly in the number of words they retrieve, then a comparison of the time course of retrieval of the two groups could provide further insight into the relative contributions of vocabulary size, reduced frequency of use, and executive control ability. Finally, if bimodal bilinguals retrieve MORE words than monolinguals, then it would, rather surprisingly perhaps, suggest that bimodal bilinguals also benefit from enhanced executive control abilities on a letter fluency task, in which case we would further predict a flatter retrieval slope for the bilinguals compared to the monolinguals (cf. Luo et al., 2010).

Methods

Participants

Nineteen hearing ASL–English bimodal bilinguals (8 females) and nineteen native monolingual English speakers (15 females) participated in the study. Background characteristics for both groups are listed in Table 1. One additional bimodal bilingual and monolingual were tested, but excluded from analysis because of technical failure and an incomplete background assessment, respectively. The bimodal bilinguals were all Children of Deaf Adults (Codas) who acquired ASL from birth. They self-rated their ASL and English proficiency on a 1 (‘very little’) – 7 (‘like native’) scale. Their mean ASL proficiency rating for was 6.0 (SD = 1.0), and five were ASL interpreters. All participants rated their English proficiency at the top end of the scale, and none were proficient in another spoken language. English receptive vocabulary knowledge was assessed with the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-III (Dunn & Dunn, 1997) and nonverbal intelligence was assessed with the K-BIT2 Matrices subtest (Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004) or the WASI Matrix Reasoning subtest (PsychCorp, 1999). Bimodal bilingual participants and monolingual participants did not differ significantly in age, years of education, vocabulary level or nonverbal intelligence (all ps ≥ .20).

Table 1.

Background characteristics of the bimodal bilingual and monolingual participants.

| ASL–English bilinguals | English monolinguals | t-test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 25.6 (5.9) | 25.9 (6.5) | .86 |

| Years of education | 14.4 (1.6) | 15.0 (1.1) | .20 |

| PPVT standard score | 110.1 (9.4) | 112.1 (11.7) | .58 |

| K-BIT Matrices T-score | 54.6 (8.2) | 55.9 (6.2) | .58 |

| ASL proficiency | 6.0 (1.0) | – | – |

| ASL % current exposure | 38.8 (22.2) | – | – |

| ASL % current use | 30.0 (18.3) | – | – |

Note. Proficiency-self ratings and information on language use and exposure were obtained through a language background questionnaire.

Procedure

The letter categories used in the present study were F, A, S, E, P, and M. Participants’ verbal responses were recorded on a digital audio-recorder, and a stopwatch was used to mark start and stop times on the recordings. Repetitions, responses from different letter categories, proper names, places and numbers were scored as errors. Raw scores were obtained by subtracting the number of errors from the total number of responses. Audacity® software was used to process the digital recordings and to identify the correct responses. For each correct response, the associated time-stamp (obtained through the software’s sound finder function) reflected the time between the onset of the recording and the onset of a given response. Based on these time-stamps, correct responses were grouped in 5-second bins for each 60-second trial.

Results

Table 2 illustrates the means and standard deviations for each letter category for the bimodal bilinguals and monolinguals.1 Despite similar receptive vocabulary levels, bimodal bilinguals retrieved significantly FEWER words than monolinguals (M = 12.8 (SD = 3.7) and M = 15.6 (SD = 3.8), t(36) = −2.36, p < .05, 95% CI [−5.3, −0.4], d = −0.76).

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations (between parentheses) of correct number of responses in each letter category for bimodal bilinguals and monolinguals.

| ASL–English bilinguals | English monolinguals | |

|---|---|---|

| F | 12.8 (5.3) | 15.8 (5.3) |

| A | 11.8 (3.9) | 13.2 (3.8) |

| S | 15.8 (5.2) | 18.4 (5.7) |

| E | 10.0 (3.5) | 11.9 (4.5) |

| P | 13.4 (4.7) | 18.1 (5.1) |

| M | 12.9 (4.1) | 16.2 (4.1) |

| Total | 12.8 (3.7) | 15.6 (3.8) |

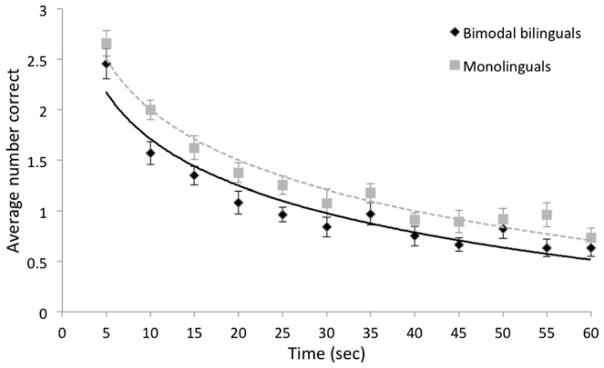

Figure 1 illustrates the time-course of retrieval in each group. Visual inspection of this graph suggests that the bimodal bilingual disadvantage is most apparent early in the letter fluency trial (except for the first five seconds). Towards the end of the trial, the differences appear to diminish slightly but do not completely disappear.

Figure 1.

Number of responses produced across all letter categories as a function of time and group. Lines represent the best-fitting logarithmic functions. Error bars represent one standard error from the mean.

This visual trend towards a larger disadvantage early in the letter fluency trial becomes even more evident if we plot the difference between bimodal bilinguals and monolinguals in number of correct responses (i.e., the ‘bimodal bilingual disadvantage’) as a function of time and exclude the first time bin, which according to Luo et al. (2010) is mainly determined by vocabulary size. Except for the penultimate bin, there is a clear indication of a downward linear trend over time towards a smaller difference in correct number of responses between bimodal bilinguals and monolinguals (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

‘Bimodal bilingual disadvantage’ with respect to mean number of correct responses as a function of time. The line represents the best-fitting linear function.

This downward trend is consistent with the reduced frequency of use account as well as the language interference account (Sandoval et al., 2010). However, these two accounts make opposite predictions with respect to the word frequency of responses produced by bilinguals. Whereas the reduced frequency of use account predicts that bilinguals will produce more higher-frequency exemplars than monolinguals because low-frequency words are less accessible for them, the interference account predicts that bilinguals will produce more lower-frequency exemplars than monolinguals because high-frequency words are more accessible in both languages and will thus compete more strongly with each other (Gollan et al., 2008). Therefore, we calculated the mean SUBTLEXus log frequency (Brysbaert & New, 2009) of correct responses produced by bimodal bilinguals and monolinguals, which did not differ significantly (M = 2.83 and M = 2.79, respectively, t(36) = 0.51, p = .61). Figure 3 plots frequency as a function of time for the letter fluency task. Visual inspection of this graph suggests that both groups produce higher-frequency words at the beginning of the trial, and there are no clear differences between the two groups.

Figure 3.

Mean SUBTLEXus log frequency of correct responses as a function of time for each group. Lines represent the best-fitting logarithmic function for each group. Please note that the y-axis does not start at zero to enhance visibility of the frequency patterns.

Discussion

The results show for the first time that bilingual disadvantages in verbal fluency are not limited to bilinguals of two spoken languages. This is an especially remarkable finding because 1) the bimodal bilinguals and monolinguals in this study had equal English receptive vocabulary levels, and 2) the bilinguals were immersed in an English-speaking environment from a very early age and were strongly spoken-language dominant. Furthermore, in contrast to unimodal bilinguals they can and often use both languages at the same time, and therefore they are less likely than unimodal bilinguals to differ from monolinguals in frequency of language use. Finally, in contrast to many combinations of spoken languages, there are no cognates for ASL and English that might benefit verbal fluency performance (i.e., there are no overlapping phonological forms).

These results have important implications for the use of verbal fluency tests as a standard measure of neuropsychological functioning and as a diagnostic tool for specific neurodegenerative diseases. The finding that bimodal bilinguals show disadvantages in verbal fluency for spoken English (their dominant language) needs to be taken into account when interpreting fluency test results. This finding also provides an important novel contribution to the existing literature on verbal fluency performance of different bilingual populations (e.g., Friesen, Luo, Luk & Bialystok, 2015; Kormi-Nouri, Moradi, Moradi, Akbari-Zardkhaneh & Zahedian, 2012; Ljungberg, Hansson, Andrés, Josefsson & Nilsson, 2013).

Specifically, our findings provide insight into the possible mechanisms underlying bilingual disadvantages in verbal fluency tasks. Given that the ASL–English bilinguals and English monolinguals had similar English receptive vocabulary levels, reduced vocabulary size clearly does not appear to be necessary for bilinguals to exhibit disadvantages in letter fluency. Although the results of the present study cannot fully distinguish between explanations based on reduced frequency of use and between-language interference, we think it is unlikely that reduced frequency of use can fully account for the bimodal bilingual disadvantage in letter fluency. This is because findings from two previous production studies with bimodal bilinguals suggested that they are not affected by a frequency lag to the same extent as unimodal bilinguals. Emmorey et al. (2013) found no difference between early or late ASL–English bilinguals and monolingual English speakers in picture naming latencies, error rates or frequency effects. Furthermore, Pyers et al. (2009) found that, although ASL–English bilinguals exhibited more lexical retrieval failures in English than monolingual English speakers, they produced more correct responses than Spanish–English bilinguals.

If between-language interference was driving the observed bimodal bilingual disadvantage in letter fluency (or at least contributed to this effect), then the current study demonstrates that bilingual disadvantages are not dependent on phonological competition between languages. That is, it would suggest that the two languages of bilinguals compete for selection during language production, regardless of whether the two languages share the same articulators or not. Although a number of studies have shown co-activation of a signed and a spoken language in comprehension, much less is known about non-selective access during bimodal bilingual production (see Emmorey, Giezen & Gollan, 2016).

One possibility that we have not yet considered is that ASL knowledge might influence English letter fluency through either fingerspelling (handshapes in a manual alphabet combined to spell English words) or initialized ASL signs (the handshape of the sign represents the initial letter of the English translation). Given the nature of the task (producing English words that begin with a particular letter), one might expect that fingerspelling and/or the existence of initialized signs in the ASL lexicon would actually facilitate rather than impair performance. Alternatively, because fingerspelled forms constitute orthographic rather than phonological representations of English words (i.e., handshapes map to letters not sounds), fingerspelling may interfere with phonologically-based retrieval strategies in English – a language that does not have a transparent mapping between orthographic and phonological representations.2

Furthermore, the existence of initialized signs may have interfered with English word retrieval for specific letter categories because some fingerspelled letter handshapes are also part of the native phonological inventory of ASL (Brentari & Padden, 2001). For example, ASL signs produced with the handshapes F, A and S are in most cases non-initialized signs (Lepic, 2013), e.g., the sign WRISTWATCH is made with an F handshape. In contrast, ASL signs produced with the handshapes E and M, and to a lesser extent P, are almost exclusively initialized signs (e.g., ELEVATOR is produced with an E handshape). However, inspection of Table 2 suggests that if anything, the bimodal bilingual disadvantage is LARGER for the ‘helpful’ letter categories E, P and M compared to F, A and S, indicating that possible language interference from initialized signs was not present for the letters F, A and S.

To further investigate the possibility that bimodal bilingual participants actively utilized links with initialized ASL signs in the letter fluency task, we calculated the proportion of English responses with initialized ASL translations out of the total number of responses for each letter category. If the bimodal bilingual participants actively relied on links with initialized ASL signs, then they would likely produce a higher proportion of English responses that had initialized ASL translations compared to the monolingual English speakers. However, an exploratory series of t-tests only revealed a significant difference for the letter M (p < .01), with the bimodal bilinguals producing a higher proportion of responses with initialized ASL translations (all other ps > .12).3 It seems unlikely, then, that associations between English words and initialized ASL signs can account for the observed bimodal bilingual disadvantage in letter fluency.

Although not a primary aim of the present study, we did not find evidence that bimodal bilinguals benefitted from enhanced executive control abilities to suppress already produced responses at the end of the letter fluency trial, as suggested for unimodal bilinguals (Friesen et al., 2015; Luo et al., 2010). The reliability and validity of bilingual advantages in executive control tasks are currently widely debated (e.g., Paap, Johnson & Sawi, 2015; Valian, 2015), and there are only a few relevant studies with bimodal bilinguals. Further research on the relationship between executive control abilities and language processing in different bilingual populations is clearly needed, including hearing and deaf bilingual signers.

In conclusion, despite being immersed in a spoken language-environment from an early age, with vocabulary levels equal to monolingual English speakers, and more opportunities to use both languages than many unimodal bilingual populations, ASL–English bilinguals exhibited word retrieval difficulties in a letter fluency task in their dominant language (English). This result demonstrates that reduced vocabulary size and/or reduced frequency of use cannot completely account for bilingual disadvantages in verbal fluency. Instead, this finding points to an important role for between-language interference in explaining word retrieval difficulties in bilinguals and, by extension, that the two languages of bilinguals compete for selection during language production even when they are expressed with distinct linguistic articulators.

Footnotes

This research was supported by Rubicon grant 446-10-022 from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research to Marcel Giezen and NIH grant HD047736 to Karen Emmorey and SDSU. We would like to thank our research participants, and Tamar Gollan, Jennie Pyers, Henrike Blumenfeld, Cindy O’Grady Farnady, Ryan Lepic, Natalie Silance, Laura Branch, Jason Baer, and Stephanie Jacobson for their help with the study. We also thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Recordings from three letters from three bilinguals were missing because of technical malfunctions. We report the results from the analyses with those cells entered as missing values.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for this suggestion.

Letter fluency recordings were only available from 15 bimodal bilinguals for this analysis.

Contributor Information

MARCEL R. GIEZEN, BCBL. Basque Center on Cognition, Brain and Language, San Sebastian, Spain

KAREN EMMOREY, School of Speech, Language and Hearing Sciences, San Diego State University.

References

- Bialystok E, Craik FIM, Luk G. Lexical access in bilinguals: Effects of vocabulary size and executive control. Journal of Neurolinguistics. 2008;21:522–538. [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E, Craik FIM, Green DW, Gollan TH. Bilingual minds. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2009;10:89–129. doi: 10.1177/1529100610387084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenfeld HK, Bobb SC, Marian V. The role of language proficiency, cognate status and word frequency in the assessment of Spanish–English bilinguals’ verbal fluency. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2016;18:190–201. doi: 10.3109/17549507.2015.1081288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brentari D, Padden CA. Native and foreign vocabulary in American Sign Language: A lexicon with multiple origins. In: Brentari D, editor. Foreign vocabulary in sign languages: A cross-linguistic investigation of word formation. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. pp. 87–120. [Google Scholar]

- Brysbaert M, New B. Moving beyond Kucera and Francis: A critical evaluation of current word frequency norms and the introduction of a new and improved word frequency measure for American English. Behavior Research Methods. 2009;41:977–990. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer JH. Verbal fluency subtest of the Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, Dunn LD. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-III. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Emmorey K, Borinstein HB, Thompson R, Gollan TH. Bimodal bilingualism. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2008b;11:43–61. doi: 10.1017/S1366728907003203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmorey K, Giezen MR, Gollan TH. Psycholinguistic, cognitive, and neural implications of bimodal bilingualism. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2015;19:223–242. doi: 10.1017/S1366728915000085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmorey K, Luk G, Pyers JE, Bialystok E. The source of enhanced cognitive control in bilinguals. Psychological Science. 2008a;19:1201–1206. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02224.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmorey K, Petrich JAF, Gollan TH. Bimodal bilingualism and the frequency-lag hypothesis. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 2013;18:1–11. doi: 10.1093/deafed/ens034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesen DC, Luo L, Luk G, Bialystok E. Proficiency and control in verbal fluency performance across the lifespan for monolinguals and bilinguals. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience. 2015;30:238–250. doi: 10.1080/23273798.2014.918630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giezen MR, Blumenfeld HK, Shook A, Marian V, Emmorey K. Parallel language activation and inhibitory control in bimodal bilinguals. Cognition. 2015;141:9–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollan TH, Montoya RI, Werner GA. Semantic and letter fluency in Spanish–English bilinguals. Neuropsychology. 2002;16:562–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollan TH, Montoya RI, Cera C, Sandoval TC. More use almost always means a smaller frequency effect: Aging, bilingualism, and the weaker links hypothesis. Journal of Memory and Language. 2008;58:787–814. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grogan A, Green DW, Ali N, Crinion JT, Price C. Structural correlates of semantic and phonemic fluency ability in first and second languages. Cerebral Cortex. 2009;19:2690–2698. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova I, Costa A. Does bilingualism hamper lexical access in speech production? Acta Psychologica. 2008;127:277–288. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL. Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test. 2. Bloomington, MN: Pearson, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kormi-Nouri R, Moradi A, Moradi S, Akbari-Zardkhaneh S, Zahedian H. The effect of bilingualism on letter and category fluency tasks in primary school children: advantage or disadvantage? Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2012;15:351–364. [Google Scholar]

- Lepic R. The phonology and morphology of initialized signs in American Sign Language. Presented at the 11th Theoretical Issues in Sign Language Research Conference; London. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ljungberg JK, Hansson P, Andrés P, Josefsson M, Nilsson LG. A longitudinal study of memory advantages in bilinguals. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e73029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L, Luk G, Bialystok E. Effect of language proficiency and executive control on verbal fluency performance in bilinguals. Cognition. 2010;114:29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael EB, Gollan TH. Being and becoming bilingual: Individual differences and consequences for language production. In: Kroll JF, De Groot AMB, editors. Handbook of bilingualism: Psycholinguistic approaches. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 389–407. [Google Scholar]

- Paap KR, Johnson HA, Sawi O. Bilingual advantages in executive functioning either do not exist or are restricted to very specific and undetermined circumstances. Cortex. 2015;69:265–278. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portocarrero JS, Burright RG, Donovick PJ. Vocabulary and verbal fluency of bilingual and monolingual college students. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2007;22:415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PsychCorp. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment, Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pyers JE, Gollan TH, Emmorey K. Bimodal bilinguals reveal the source of tip-of-the-tongue states. Cognition. 2009;112:323–329. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosselli M, Ardila A, Salvatierra J, Marquez M, Matos L, Weekes VA. A cross-linguistic comparison of verbal fluency tests. International Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;112:759–767. doi: 10.1080/00207450290025752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval TC, Gollan TH, Ferreira VS, Salmon DP. What causes the bilingual disadvantage in verbal fluency? The dual-task analogy. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2010;13:231–252. [Google Scholar]

- Valian V. Bilingualism and cognition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2015;18:3–24. [Google Scholar]