Abstract

Introduction:

Due to growth of occupational diseases and also increase of public awareness about their consequences, attention to various aspects of diseases and improve occupational health and safety has found great importance. Therefore, there is the need for appropriate information management tools such as registries in order to recognitions of diseases patterns and then making decision about prevention, early detection and treatment of them. These registries have different characteristics in various countries according to their occupational health priorities.

Aim:

Aim of this study is evaluate dimensions of occupational diseases registries including objectives, data sources, responsible institutions, minimum data set, classification systems and process of registration in different countries.

Material and Methods:

In this study, the papers were searched using the MEDLINE (PubMed) Google scholar, Scopus, ProQuest and Google. The search was done based on keyword in English for all motor engines including “occupational disease”, “work related disease”, “surveillance”, “reporting”, “registration system” and “registry” combined with name of the countries including all subheadings. After categorizing search findings in tables, results were compared with each other.

Results:

Important aspects of the registries studied in ten countries including Finland, France, United Kingdom, Australia, Czech Republic, Malaysia, United States, Singapore, Russia and Turkey. The results show that surveyed countries have statistical, treatment and prevention objectives. Data sources in almost the rest of registries were physicians and employers. The minimum data sets in most of them consist of information about patient, disease, occupation and employer. Some of countries have special occupational related classification systems for themselves and some of them apply international classification systems such as ICD-10. Finally, the process of registration system was different in countries.

Conclusion:

Because occupational diseases are often preventable, but not curable, it is necessary to all countries, to consider prevention and early detection of occupational diseases as the objectives of their registry systems. Also it is recommended that all countries reach an agreement about global characteristics of occupational disease registries. This enables country to compare their data at international levels.

Keywords: registry system, occupational disease, objective, data sources, minimum data set, classification systems and registration process

1. INTRODUCTION

Occupational diseases caused by occupational activities and working conditions (1). In fact, any disease occurs at early stage as a result of exposure to occupational (physical, chemical or biological) risk factors is an occupational disease (1-3).

Occupational diseases impose considerable costs to workers, their family, health care system and society (4) and reduce productivity and work capacity. According to ILOs’ estimates, occupational diseases and injuries causes the loss of 4% of global GDP annually, in other words direct and indirect costs of these diseases and injuries is about 2.8 trillion dollars (5). In addition, due to social and technological changes, the nature of occupational diseases is changing and new occupational diseases are emerging (6).

In the other hand, occupational diseases are not curable or have long-term and difficult treatment. But most of these diseases are preventable (7, 8). Preventing these diseases requires correct information about prevalence of them (9). Nevertheless, statistical and basic information about some of occupational diseases are not available due to lack of awareness, diagnostic problems and insufficient attention to these diseases. And there are many limitations in reporting and systematic collection of data relating to occupational diseases. To overcome these challenges developing occupational diseases registries, as an effective solution, is very useful.

Disease or patient registries are the rich sources of information for any decision making in the field of health (10). Like other registries, occupational disease registry is a set of information about work related disease and injuries with different levels of complexity. And applies for multiple purposes such as administrative, statistical, preventive, diagnostic, treatment follow up and research (11). Registry information is crucial to the recognition and then planning for treatment, and prevention of occupational injuries and disease (12). Using this information to detect patterns of disease, can be taken as an effective action to prevent disease and reduce the health, economic and social costs (13, 14).

2. AIM

Considering that there is not comprehensive information about the status of occupational diseases registries in other countries. In this paper, we studied the status of occupational diseases in selected countries, and the results are presented in comparative tables; also some information is described narrative.

3. MATERIAL AND METHODS

In this study, the papers were searched according to keywords in English using the MEDLINE (PubMed) during 1989 to 2017, Google scholar, Scopus, ProQuest and Google. Keywords included “occupational disease”, “work related disease”, “surveillance”, “reporting”, “registration system” and “registry” combined with name of the countries including all subheadings. After completed search, all search results were reviewed separately in databases based on titles and related articles were selected. Then we excluded duplicated documents. Two reviewers reviewed all documents separately. Then unrelated documents were excluded and data collection forms were filled with accepted documents. Then articles have been categorized based on their developer countries. After that the results were presented in the comparative tables. In all stages, the disagreements between reviewers were addressed by group discussion.

4. RESULTS

In this review, documents were included from mentioned database. The included documents arranged according to their selected countries. At last the result presented in two narrative and table format (Table 1 and Table 2).

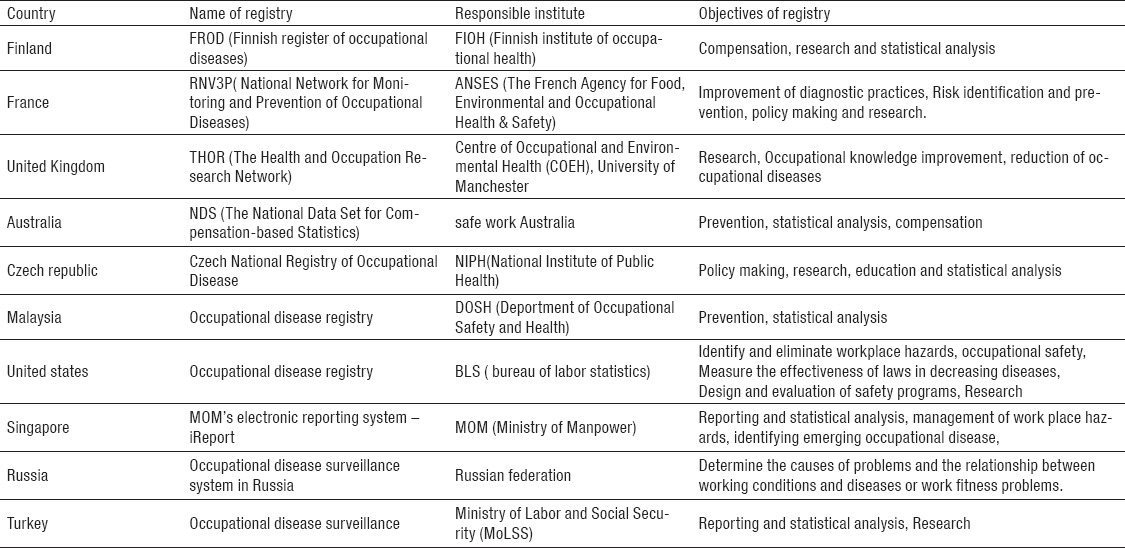

Table 1.

Name, responsible institution and objectives of registries

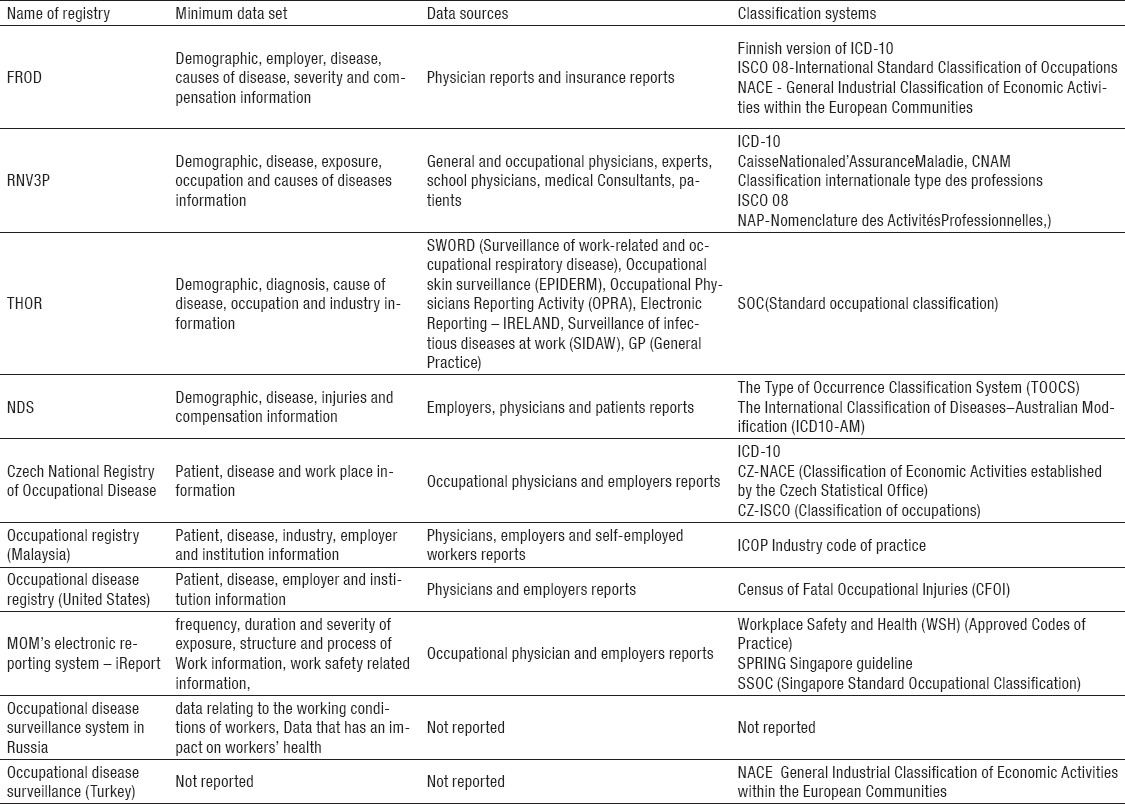

Table 2.

Minimum data set, data sources and classification system of registries

In this part other characteristics of mentioned registries are describing according the name of the countries.

Finland

In Finland the occupational disease registry covers people who are working under a contract for an employer, public services, public administration, or as entrepreneurs like farmers. There is three ways to reports occupational disease cases to the FROD (Finnish register of occupational disease) (15). In one way, insurance companies send reports from physicians and employers to the FAII (The Federation of Accident Insurance Institution) then FAII send these reports to the FROD. In other way MELA (the farmers’ social insurance institution) sends physicians and farmers reports to FROD. In the last way regional state administrative agencies send physicians’ reports to the FROD directly.

In Finland occupational diseases reportable including diseases caused by asbestos, skin diseases, Allergic respiratory disease, Injuries caused by repeated pressure, hearing loss, and other diseases including infectious diseases, vibration syndrome, conjunctivitis and different types of poisoning (16-19).

France

RNV 3 is a National Network for Monitoring and Prevention of Occupational Diseases in the France that coordinates Knowledge of the registry for monitoring purposes, recovery and prevention of occupational risks. This network also contributes through Modernet Network (a network of monitoring trends in occupational diseases in the European countries) with other European counterparts (20).

The Occupational Disease Consultation Centers (CCPPs) and occupational health services (SSTs), report new cases of occupational diseases to the RNV3 without any inclusion and exclusion criteria. Registration has been done by occupational physicians, general practitioners and other specialists, nurses, medical secretaries and trained intern. RNV3P includes 110 tables of all occupational diseases in France. Most tables’ present diseases are caused by chemical substances but some of them including diseases caused by noise, repetitive movements and working conditions (21, 22).

United Kingdom

In United Kingdom the THOR (the health and occupation research network) program created in 2002 Based on the voluntary participation of more than a thousand specialists, including physicians, consultants and dermatologists transmitted diseases, as well as trained general practitioners to report cases of occupational diseases. Since 2005, occupational data from the Republic of Ireland are collected by THOR. It also contributes with other European countries through Modernet Network (23-25).

THOR allows physicians report every item that they believe created by occupational factors addition to the occupational disease list provided by this program (26).

Occupational diseases that are included in THOR are musculoskeletal disorders, stress, depression and anxiety, skin diseases, respiratory diseases and other diseases. THOR covers all people with occupational problems who connect to doctors’ offices and clinics (24).

Australia

The National Data Set for Compensation-based Statistics (NDS) is a national occupational registration system in Australia. NDS provides information on workers’ compensation claims that involve work-related disease in fact every compensation claim request from workers is a new case in the registry system (27, 28). Occupational diseases included in the registry are musculoskeletal diseases, mental disorders, cardiovascular diseases, occupational cancers, respiratory diseases, infectious and parasitic diseases, contact dermatitis and noise-induced hearing loss (29). Range of cases recorded in NDS, are included all new cases (all verified, rejected cases and cases in the decision making process) reported in the current year. Claims that were subsequently withdrawn by the worker and the ones that are outside the scope of application of the program are removed (30).

Czech Republic

The NRNP (the Czech National Registry of Occupational Disease) created in 1991 and is maintained by Centre of occupational medicine of the State Institute of public health in Prague as Central register of occupational diseases. NRNP since 2003 is connected with EODS (European Occupational Diseases Statistics) (31-33). Occupational diseases caused by chemical substances, occupational diseases caused by physical factors, occupational diseases relating to the respiratory pathways, lungs, pleura and peritoneum, occupational skin diseases caused by physical, chemical or biological factors, infectious and parasitic occupational diseases, occupational diseases due to other factors or agents are included in the registry system (34).

Malaysia

The occupational disease registration system in Malaysia was created and is maintained by DOSH (department of occupational safety and health). According to law, employers and physicians are obliged to report new cases of occupational diseases to DOSH (35-37).

Occupational diseases in this registry system including Occupational lung diseases, occupational skin diseases, noise-induced hearing loss, diseases caused by chemical agents (poisoning), diseases caused by biological agents, occupational cancers and other occupational diseases (38).

Registry covers workers in occupations such as manufacturing, mining and quarrying, construction, agriculture, forestry, logging and fishery, utility, transport, storage and communication, wholesale and retail trade, hotel and restaurant, financial, insurance, real estate and business services, public services and statutory bodies (38).

United States

In the United States IIF (Injuries, Illnesses, and Fatalities) provide rates and the number of occupational diseases, injuries and the number of fatal cases annually. Two main data sources of this program are SOII (The Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses) and CFOI (Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries). SOII is a federal program in which employer’s reports (OSHA 300 form) are collected from private industry and public sector annually. These reports are processed by BLS (Bureau of Labor Statistics). Diseases that are included in the registry contain occupational musculoskeletal diseases, infectious diseases, respiratory diseases, skin diseases and other diseases (39-41).

The registry provides data from all full-time and part-time wage and salary workers in nonfarm industries. The excluded items are self-employed, owners and partners in unincorporated firms, household workers, or unpaid family workers (42).

Singapore

In Singapore “iReport” was introduced as a national system of electronic reporting for occupational diseases in 2006 under the supervision of MOM (Ministry of Manpower) (43). Physicians and employers are required to report cases of occupational diseases. Physicians during ten days from the time of diagnosis should register cases in the iReport system. Employers too within ten days of receiving a written diagnosis of the disease should report it (44).

Occupational diseases list in Singapore including anthrax, asbestosis, barotrauma, byssinosis, chrome ulceration, compressed air illness, epitheliomatous ulceration, occupational skin diseases, liver angiosarcoma, mesothelioma, noise-induced deafness, occupational asthma, repetitive strain disorder of the upper limb, silicosis, toxic anemia, toxic hepatitis and poisonings due to Aniline, Arsenical, Beryllium, Cadmium, Carbamate, Carbon bisulphide, chronic benzene, Cyanide, Hydrogen sulphide, Lead, Manganese, Mercurial, Organophosphate, Phosphorous and halogen derivatives of hydrocarbon compounds (45).

Russia

Before 2007, Russia was not mandated evaluation of the working environment and working conditions monitoring was done selective.

A law was passed in 2007 by the Ministry of Health asked all employers that to measure and quantify workplace hazards every 5 years by standardized methods. After that in 2013 Russia adopted the federal law on the basis of a special assessment of working conditions. This law classified working condition in to the 4 level including optimal, permissible, harmful and dangerous (46). According to working condition, workers receive different types of compensation fees (47). The medical commission in suspected cases of occupational diseases reports the results of medical examination to the employers and Rospotrebnadzor (Territorial Department of Federal Service for Oversight of Consumer Protection and Welfare). Then hygienists of Rospotrebnadzor prepare a reports including a description of the sanitary-hygienic characteristics of working conditions, containing the occupational history, description of the working process, information about applied materials and equipment, and levels of occupational exposures during two weeks (48, 49).

Turkey

The SSI (Social Security Institution) is the governing authority of the Turkish social security system and according to law reporting all occupational diseases and injuries to SSI is mandatory. The report arranged and classified by SSI in accordance with the rules of the International Labour Organization.

According to statistics released by SSI in Turkey occupational diseases are divided into 5 groups including occupational diseases caused by chemicals, occupational skin disorders, pneumoconiosis and other respiratory occupational diseases, communicable occupational diseases and occupational diseases caused by physical factors. In total 74 cases of occupational disease are defined in 5 groups.

In this field the main challenge is underreporting of occupational disease in compare with other counties reports such as Germany, United States and Finland (50, 51).

5. CONCLUSION

Obviously, in order to identify and prevent occupational diseases, the existences of valid and powerful information systems such as occupational diseases registries are essential. However, in most countries still appropriate and comprehensive registry systems, for these purposes, does not exist.

On the other hand, despite development and implementation of the occupational diseases registry in some countries, due to lack of international agreements and standards, comparing of data at international level is not possible. Creating such standards will accelerate the development of these systems in other countries.

Footnotes

• Conflict of interest: none declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Fidancı İ, Ozturk O. A General Overview on Occupational Health and Safety and Occupational Disease Subjects. Journal of Family Medicine and Health Care. 2015;1(1):16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cherry N. Occupational disease. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 1999;318(7195):1397. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7195.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Driscoll T, Takala J, Steenland K, Corvalan C, Fingerhut M. Review of estimates of the global burden of injury and illness due to occupational exposures. American journal of industrial medicine. 2005;48(6):491–502. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takala J, Hämäläinen P, Saarela KL, Yun LY, Manickam K, Jin TW, et al. Global estimates of the burden of injury and illness at work in 2012. Journal of occupational and environmental hygiene. 2014;11(5):326–37. doi: 10.1080/15459624.2013.863131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Labour Organization I. IXIX World Congress on Safety and Health at Work. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 6.International Labour Organization I. The Prevention Occupational Diseases. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guidotti TL. Global occupational health. Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh AK, Loscalzo J. The Brigham Intensive Review of Internal Medicine. Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landrigan PJ. Improving the surveillance of occupational disease. American journal of public health. 1989;79(12):1601–2. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.12.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Workman TA. Engaging patients in information sharing and data collection: the role of patient-powered registries and research networks: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), Rockville (MD) 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agius R, Sim R, Bonneterre V. What do surveillance schemes tell us about the epidemiology of occupational disease. Current Topics in Occupational Epidemiology. 2013:131. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spreeuwers D, de Boer A, Verbeek J, van Dijk F. Evaluation of occupational disease surveillance in six EU countries. Occupational medicine. 2010;60(7):509–16. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqq133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Markowitz SB. Occupational disease surveillance and reporting systems. ILO encyclopaedia of occupational safety and health. 1998;1:322–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azaroff LS, Levenstein C, Wegman DH. Occupational injury and illness surveillance: conceptual filters explain underreporting. American journal of public health. 2002;92(9):1421–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.9.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karjalainen A, Kurppa K, Virtanen S, Keskinen H, Nordman H. Incidence of occupational asthma by occupation and industry in Finland. American journal of industrial medicine. 2000;37(5):451–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(200005)37:5<451::aid-ajim1>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riihimäki H. Occupational diseases in Finland in 2002: New cases of occupational diseases reported to the Finnish Register of Occupational Diseases: Finnish Institute of Occupational Health. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oksa P, Palo L, Saalo A, Jolanki R, Mäkinen I, Pesonen M, et al. Occupational diseases in Finland 2012. Helsinki: Finnish institute of occupational health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Organization WH. National Profile of Occupational Health System in Finland. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carder M, Bensefa-Colas L, Mattioli S, Noone P, Stikova E, Valenty M, et al. A review of occupational disease surveillance systems in Modernet countries. Occupational Medicine. 2015;65(8):615–25. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqv081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonneterre V, Faisandier L, Bicout D, Bernardet C, Piollat J, Ameille J, et al. Programmed health surveillance and detection of emerging diseases in occupational health: contribution of the French national occupational disease surveillance and prevention network (RNV3P) Occupational and environmental medicine. 2010;67(3):178–86. doi: 10.1136/oem.2008.044610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faisandier L, Bonneterre V, De Gaudemaris R, Bicout DJ. Occupational exposome: A network-based approach for characterizing Occupational Health Problems. Journal of biomedical informatics. 2011;44(4):545–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lebaupain C, editor. National Network for Monitoring and Prevention of Occupational Diseases. 30th International Congress on Occupational Health (March 18-23 2012) 2012 Icoh. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Health CfOaE. The Health and Occupation Research Network. 2015. Available from: http://research.bmh.manchester.ac.uk/epidemiology/COEH/research/thor .

- 24.Executive HaS. Data sources, Introduction to data sources. 2014. Available from: http://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/sources.htm .

- 25.Money A, Carder M, Hussey L, Agius R. The utility of information collected by occupational disease surveillance systems. Occupational Medicine. 2015;65(8):626–31. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqv138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carder M. The role of THOR in occupational disease surveillance. 2013. Available from: https://sm.britsafe.org/role-thor-occupational-disease-surveillance#sthash.fLdiNI8Y.dpuf .

- 27.Driscoll TR, Hendrie L. Surveillance of work related disorders in Australia using general practitioner data. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health. 2002;26(4):346–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2002.tb00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Safety A, Council C. Type of occurrence classification system. Canberra: Australian Safety and Compensation Council; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Australia SW. National Data Set for Compensation-based Statistics. Canberra: Safe Work Australia; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Australia Safe Work. Occupational Disease Indicators. 2014. 2014-7-8. [2016-04-11] http://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/sites/swalabout/publications/pages/oceupational-disease-indi-cators-2014. 2014)

- 31.Urban P, Cikrt M, Hejlek A, Lukas E, Pelclová D. The Czech National Registry of Occupational Diseases. Ten years of existence. Central European journal of public health. 2000;8(4):210–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Urban P. Register of Occupational Diseases. 2007. Available from: www.szu.cz/publikace/data/nemoci-z-povolani .

- 33.Republic IoHIaSoC. National Register of Occupational Diseases. 2016. Available from: http://www.uzis.cz/en/registers/national-health-registers/nr-occupational-diseases .

- 34.SZU. Occupational Diseases Reported in the Czech Republic. 2015. Available from: http://www.szu.cz/publications-and-products/data-and-statistics/occupational?lang=2 .

- 35.Abas ABL, Said ARBM, Mohammed MABA, Sathiakumar N. Occupational disease among non-governmental employees in Malaysia 2002-2006. International journal of occupational and environmental health. 2008;14(4):263–71. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2008.14.4.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hashim A. Notification of Accident, Dangerous Occurrence, Occupational Poisoning and Occupational Disease Regulations 2004 (NADOPOD)-An Introduction. PLANTER. 2005;81(951):349. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Health DoOSa. Notification of Accident, Dangerous Occurrence, Occupational Poisoning and Occupational Disease (NADOPOD)–JKKP 6, 7, 8, 9, 10. 2017. Available from: http://www.dosh.gov.my/index.php/en/form-download/nadopod-1/list-of-tables .

- 38.Leman AM, Omar AR, Rahman K, Mohamad Zainal M. Reporting of occupational injury and occupational disease: current situation in Malaysia. Asian-Pacific Newsletter on Occupational Health and Safety. 2010;17(2):39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stanbury M, Largo T, Granger J, Cameron L, Rosenman K. Profiles of Occupational Injuries and Diseases in Michigan. Retrieved September. 2004;28:2005. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Statistics BoL. Nonfatal Occupational Injuries and Illnesses by Industry. 2016. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/iif/oshsum1.htm .

- 41.Development DoLW. Log of Work-Related Injuries and Illnesses. 2004. Available from: http://lwd.dol.state.nj.us/labor/forms_pdfs/lsse/NJOSH300_forms.pdf .

- 42.Labor USDo. Occupational Employment Statistics. 2016. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/oes/oes_emp.htm#scope .

- 43.LeeHock S, Tan A. Singapore’s framework for reporting occupational accidents, injuries and diseases. Asian-Pacific Newsletter on Occupational Health and Safety. 2010;17(2):28–31. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manpower Mo. a guide to the workplace safety and health regulations. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Choy K, Xingyong A. Reporting of Occupational Diseases in Singapore. The Singapore Family Physician. 2011;37(2):25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vyshnevskyy D, Kasyanov N, Medianyk V. The ways of improving performance of industrial risk and working conditions. Teka Komisji Motoryzacji i Energetyki Rolnictwa. 2013;13:4. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moskvichev AV, Adeninskaya EE, Kretov AS, Trofimova MV, Sabitova MM, Bushmanov AY. Current Status and Prospects of Occupational Medicine in the Russian Federation. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dudarev AA, Odland JØ. Occupational health and health care in Russia and Russian Arctic 1980-2010. International journal of circumpolar health. 2013:72. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.20456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matveev NV. Medical Informatics in Occupational and Environmental Health of Russia: Need of Reforms. Nizhny Novgorod, Russia: NNRIHOP; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ceylan H, GÜ L TS. Facts on Safety at Work for Turkey. Journal of Multidisciplinary Engineering Science and Technology. 2015;2(5):1192–1200. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Erdogan MS, editor. Underreporting problems of occupational diseases and injuries in Turkey: the situation in agriculture. 30th International Congress on Occupational Health (March 18-23 2012) 2012 Icoh. [Google Scholar]